Abstract

Background:

The risk of transfusion reactions (TR) and the cost of blood has led to efforts to reduce blood use. We changed our practice to transfuse just 1 instead of 2 units of red blood cells (RBC) when hemoglobin ≤8g/dl due to patient blood management (PBM) recommendations.

Methods and Materials:

We compared RBC utilization in patients receiving allogeneic HCT in the 10 months before (control arm) and 13 months after implementation of this new practice (intervention arm). We used regression models to estimate the independent effect of transfusion practice, length of hospitalization, the conditioning regimen, and donor type for patients who received at least 1 RBC unit. The outcome variable was total number of inpatient transfusions. In addition, a survey assessed the impact of this.

Results:

Cohorts were matched for age, primary diagnosis, graft source and conditioning regimen. The median number of RBC units transfused/patient was identical in both arms (4. Interquartile range 1–9 units/patient). Using the regression model, only length of stay (relative increase of 1.035 units/day; 95%CI, 1.027–1.043) was an independent predictor of the number of RBC units a patient received. When data were normalized/1000 patient days, the control arm received 240 units vs the intervention arm, which received 193 units, resulting in a reduction of 47 units transfused/1000-patient-days, which was not statistically significant (p-value 0.32). The survey of RNs showed that it positively affected the workflow.

Conclusions:

There was a modest reduction in RBC utilization based on units transfused/1000-patient-days. There was a positive impact on RN workflow.

INTRODUCTION

The transfusion of blood components is a critical supportive measure for those undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT). Blood transfusions represent the single most common medical procedure in the US 1. While transfusions are safe, there is a risk of transfusion reactions such as transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO), iron overload, and transfusion transmitted infections2–5. In addition, a limited blood supply and the significant cost of blood components where a red blood cell (RBC) unit may cost US $1,00020 has led to efforts to limit transfusions. Health care providers interested in patient blood management (PBM) have developed recommendations to reduce unwarranted transfusions4. Our Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant (BMT) Program recently changed the inpatient clinical practice to transfuse just one instead of two units of RBC when the transfusion threshold of hemoglobin (Hgb) of 8.0 g/dL was met 6. Our hypothesis is that it would result in a reduction in RBC utilization and not adversely impact patients’ outcomes. In this manuscript we describe the impact of this change on RBC utilization, prevalence of transfusion reactions, and nursing staff workflow.

PATIENT AND METHODS

In this study we included patients > 18 years old who received an allogeneic HCT between July 1st, 2015 and June 30th, 2017. Autologous transplant recipients who are mostly managed in the outpatient setting were excluded. As part of a quality improvement project, on June 1st, 2016 we changed our general RBC transfusion practice to transfuse one instead of two units of red blood cells (RBC) when the hemoglobin was ≤ 8 g/dL or another patient specific transfusion threshold was met.

Transfusion reactions were identified by the administering nurse using the signs and symptoms outlined by the National Healthcare Safety Network’s Hemovigilance module 7. The implicated component(s) in the suspected transfusion reactions were returned to the blood bank for a clerical check, inspection of the component for clots or hemolysis, ABO and crossmatch confirmation, and direct antiglobulin test (DAT). The component was also tested by Gram stain and microbiology cultures when patients experienced a fever ≥ 38 C, rigors, or hypotension. Transfusion physicians reviewed clinical and laboratory data to render a final diagnosis.

The primary aim of this retrospective study was to compare RBC utilization in patients receiving allogeneic HCT in the 10 months before and 13 months after implementation of the practice of transfusing one rather than two RBC units per transfusion episode. The BMT Data Base, Blood Bank Data Base, and electronic medical records were used as data sources. In addition, a four question anonymous survey was used to determine the impact of this change in practice on BMT inpatient unit registered nurses (RN) workflow. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board.

Statistical considerations

The statistical approach required a combination of descriptive statistics, graphical summaries, and statistical models to fully characterize the effect of the change in transfusion policy on RBC and platelet transfusion burden. Our focus was on estimating the degree of effects and thus statistical inference primarily used confidence intervals to show the range of effect sizes consistent with our data. The sample size was determined by the number of eligible patients treated 10 months pre and 13 months post of the transfusion policy change on June 1st, 2016. Four patients transplanted in May 2016 were excluded because their inpatient stay overlapped the policy change.

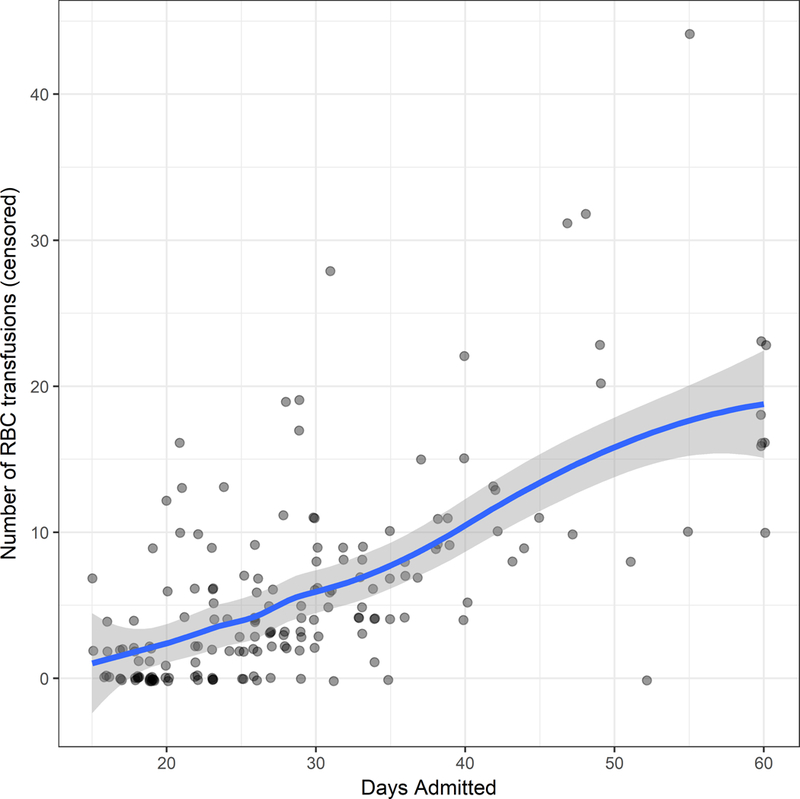

Exploratory plots showed several patients with a very high number of transfusions. To attenuate their influence, we defined censored transfusion counts, which do not count transfusions given after graft failure, a second transplant, or after the 60th day of hospital admission. These were used for a sensitivity analysis. Non-censored variables, which used data from the entire hospital admission regardless of duration, were used for primary analysis.

Graphs which show the mean number of transfusions per day over time used a loess smoother to estimate the mean trend 8, 9. Multivariable models were used to estimate the independent effects of 1 or 2 units per transfusion episode, length of hospital stay, conditioning regimen intensity, and donor type on total number of patient transfusions. We used negative binomial regression 10, which is commonly used to model count data in which the outcome variable is a non-negative integer. To improve model fit, patients with zero transfusions were excluded from the model; the percentage of patients with zero transfusions was similar in the two study groups and the policy change was unlikely to impact them. Variables were specified prior to analysis and a total of four models were fit: two each for RBC and platelet transfusions, using the censored and uncensored transfusion counts as outcome variables.

Secondary outcomes included reactions per transfusion, which were calculated as proportions with 95% Wilson confidence intervals, and TRM, estimated using the cumulative incidence function 11 and compared by a Fine-Gray test 12 with relapse considered a competing risk. Analysis was performed using R software, version 3.4 13.

RESULTS

Patient and Transplant Characteristics

Patients and transplant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 172 allogeneic transplant recipients were included in this study. The study considered the transfusion burden during the first admission for the allogeneic transplant starting from the date of admission. 84 patients were treated when the standard red blood cell (RBC) transfusion practice was to give 2 units if Hgb ≤ 8 g/dL and 88 were treated since we established the current transfusion practice of giving 1 unit if Hgb ≤ 8 g/dL. The mean age at transplantation was 56 years-old (range [r]: 23–75 years-old). Approximately two-thirds of the recipients were CMV seropositive. The donor’s recipient sex and ABO match were similar in each group. The primary indication of allogeneic transplantation was acute leukemia. In most patients the allogeneic graft source was either peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) or umbilical cord blood (UCB), which were represented in similar proportions in both groups. Most patients received a reduced intensity conditioning and half of the patients received a calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) immune suppression regimen. The mean hospitalization was 31 days in both groups. The reason for higher proportion of UCB in this study is due to our institution’s research focus on this type alternative of donor.

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics

| Variables | 2 units/episode | 1 unit/episode |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 84 | 88 |

| Age at transplant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 57 (12) | 55 (12) |

| Q1, Q3 | 49, 65 | 46, 65 |

| Range | 26 − 75 | 23 − 74 |

| Sex Match | ||

| Female donor to female recipient | 13 (15%) | 10 (11%) |

| Female donor to male recipient | 25 (30%) | 29 (33%) |

| Male donor to female recipient | 20 (24%) | 26 (30%) |

| Male donor to male recipient | 26 (31%) | 23 (26%) |

| ABO Match | ||

| Bi-directional mismatch | 4 (4.8%) | 8 (9.1%) |

| major mismatch | 21 (25%) | 20 (23%) |

| match | 39 (46%) | 41 (47%) |

| minor mismatch | 20 (24%) | 19 (22%) |

| CMV Donor: Recipient Serostatus | ||

| negative:negative | 24 (29%) | 20 (23%) |

| positive:negative | 5 (6%) | 7 (8%) |

| negative:positive | 43 (51%) | 41 (47%) |

| positive:positive | 12 (14%) | 20 (23%) |

| Disease | ||

| AML/ALL/Acute Leukemia | 46 (55%) | 55 (62%) |

| CML/MDS/Myeloproliferative Disorder | 19 (23%) | 20 (23%) |

| NHL/Small Lymphatic Lymphoma | 10 (12%) | 8 (9.1%) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 4 (4.8%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Non-malignant | 5 (6%)1 | 4 (4.5%)2 |

| Donor type | ||

| Umbilical cord blood | 34 (40%) | 36 (41%) |

| Haploidentical | 3 (3.6%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Sibling/matched unrelated donor | 47 (56%) | 46 (52%) |

| Graft source | ||

| Umbilical cord blood | 34 (40%) | 36 (41%) |

| Bone marrow | 12 (14%) | 17 (19%) |

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 38 (45%) | 35 (40%) |

| Conditioning | ||

| Myeloablative | 28 (33%) | 34 (39%) |

| Non-Myeloablative | 56 (67%) | 54 (61%) |

| GVHD Prophylaxis | ||

| Calcineurin inhibitor/MMF | 45 (54%) | 57 (65%) |

| Methotrexate/calcineurin inhibitor | 20 (23.3%) | 12 (14%) |

| MMF/Sirolimus | 12 (14%) | 9 (10%) |

| Post-transplant cyclophosphamide/ calcineurin inhibitor/MMF | 6 (7.1%) | 7 (8%) |

| Other | 1 (1.2%) | 3 (3.4%) |

| Days Admitted | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30 (15) | 31 (16) |

| Q1, Q3 | 22, 34 | 20, 33 |

| Range | 15 − 84 | 15 − 119 |

Adrenoleukeodystrophy n=2, Aplastic Anemia n=1, Dyskeratosis Congenita n=2

Aplastic Anemia n=2, Fanconi Anemia n=2

SD, standard deviation; Q, quartile; CMV, cytomegalovirus; AML, Acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; GVHD, graft-vs.-host disease; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Impact of RBC Transfusion Practice on Patient RBC Transfusion Burden

In Figure 1A and Table 2 we summarize the number of RBC transfusions in the study period. The median number of RBC units transfused per patient when the practice was to give 2 units was 4 (Interquartile (IQR) range 0–10 units/patient), and was similar to that observed when the transfusion practice was to give 1 unit (median 4, IQR 1–9 units/patient). However, the mean number of RBC unit transfusions were 7.3 and 6.0, an 18% decrease. The difference was attributable to fewer patients with a very high number of transfused RBC units, as the interquartile ranges were similar. In both groups about a quarter of the patients did not receive any RBC transfusions during the first admission for transplantation.

Figure 1.

(A) the number of red blood cell units received per patient for the length of hospitalization, censored at 60 days of hospitalization.

Table 2.

Summary of transfusion data

| Variables | 2 units/episode | 1 unit/episode | P- Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 84 | 88 | |

| Number of RBC tx (all data) | 0.32 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (10.4) | 6.0(6.3) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (0, 10) | 4 (1,9) | |

| Number of RBC tx (excluding censored) | 0.14 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.9 (8.9) | 5.3 (4.5) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (0, 10) | 4 (1, 9) | |

| Number of RBC reactions (all data) | 0.51 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.07 (0.30) | 0.05 (0.21) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | |

| Zero RBC transfusions (n, %) | 22 (26%) | 19 (22%) | 0.60 |

| Number of Platelet tx (all data) | 0.99 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 14.9 (23.8) | 14.9 (20.8) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 6 (2, 18.5) | 8 (3, 19) | |

| Number of Platelet tx (excluding censored) | 0.70 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 13.8 (19.1) | 12.8 (13.8) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 6 (2, 18.5) | 8 (3, 19) | |

| Number of Platelet reactions(all data) | 0.78 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.12 (0.36) | 0.14 (0.43) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | |

| Zero Platelet transfusions (n, %) | 18 (21%) | 16 (18%) | 0.73 |

RBC, red blood cell; tx, transfused; SD, standard deviation; Q, quartile.

Censored outcomes do not count transfusions that occurred after 60 days hospitalization, graft failure, or a second transplant. All outcomes are calculated per patient.

We performed a secondary analysis which censored transfusions that occurred after 60 days of hospitalization, graft failure, or a second transplant. We hypothesized that those factors could be associated with a high transfusion burden for reasons unrelated to the transfusion policy. Mean RBC units transfused per patient were 6.9 and 5.3, a 23% decrease, but the median remained the same.

We studied whether the transfusion practice influenced the number of transfusion episodes per day because patients treated once the transfusion practice was changed to give 1 unit per episode may still receive more than 1 unit/day. Patients transfused when the practice was to give 2 units typically received 2 units per day, whereas patients transfused during our current practice of transfusing 1 unit at a time typically received 1 unit; however, the majority of patients did not receive RBC transfusions every-day resulting in similarly low and overlapping daily mean number RBC units transfused in both groups. We noticed individual patients tapers over time reflecting those who were discharged and, less frequently, those who died during the first hospitalization. In addition, the number of RBC units received per patient in each day was similar regardless of intensity of the conditioning regimen or donor type.

We then utilized negative binomial regression models to estimate the independent effect of transfusion practice (1 vs. 2units/episode), length of hospitalization, intensity of the conditioning regimen, and donor type that included patients who receive at least one transfusion. The outcome variable was total number of transfusions during hospitalization. As shown in Table 3, only length of stay (Relative increase of 1.035 units per day; 95%CI, 1.027–1.043) was an independent predictor of the number RBC units a patient received. In this multiplicative model, we multiply the intercept (2.451) by the hospital-days coefficient (1.035) for each day of hospitalization to estimate the average number of RBC units transfused for a patient in all reference groups. Thus, for patients in the reference group (2 units/episode transfusion practice, myeloablative, and UCB donor) who stayed hospitalized 30 days, we calculate the average number of RBC transfused as 2.451 × 1.035^30 = 6.87 RBC units. In order to determine the average number of RBC transfusions for patients undergoing a non-myeloablative sibling transplant with the same 30 days length of stay, we would now calculate 6.87 × 0.914 × 1.203= 7.6 RBC units. The estimated relative change in number of RBC transfusions with 1 unit/episode relative to 2 units was 0.858 (95% CI 0.688–1.069). The model-estimated 14% decrease was similar to the 18% raw data decrease. The 95% CI indicates the uncertainty in this estimate; these data are reasonably consistent with the true difference being between 31% fewer to 7% more RBC transfusions with 1 unit/episode.

Table 3.

Multivariable Models

| Red Blood Cell Transfusions |

Platelet Transfusions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Relative Changes | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Variables | Relative Changes | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

| Transfusion practice | Transfusion practice | ||||||

| 2 units/episode (n=84) | 1.000 | 2 units/episode (n=84) | 1.000 | ||||

| 1 unit/episode (n=88) | 0.858 | 0.688 | 1.069 | 1 unit/episode (n=88) | 1.070 | 0.837 | 1.367 |

| Hospital Days (per day) | 1.035 | 1.027 | 1.044 | Hospital Days (per day) | 1.044 | 1.034 | 1.055 |

| Conditioning Regimen Intensity | Conditioning Regimen Intensity | ||||||

| Myeloablative (n=62) | 1.000 | Myeloablative (n= 62) | 1.000 | ||||

| Non-Myeloablative (n=110) | 0.914 | 0.725 | 1.151 | Non-Myeloablative (n=110) | 0.792 | 0.613 | 1.024 |

| Donor Type | Donor Type | ||||||

| UCB (n=70) | 1.000 | UCB (n=70) | 1.000 | ||||

| Donor: Haplo (n=9) | 1.299 | 0.820 | 2.102 | Donor: Haplo (n=9) | 0.902 | 0.529 | 1.614 |

| Donor: Sibling/MUD (n=93) | 1.203 | 0.926 | 1.565 | Donor: Sibling/MUD (n=93) | 1.084 | 0.817 | 1.438 |

| Intercept | 2.451 | 1.596 | 3.728 | Intercept | 3.617 | 2.226 | 5.831 |

The outcome in each model is the total number of transfusions during a patient’s hospitalization. Thus, a patient receiving 1 unit/episode averaged 0.858 times the number of RBC transfusions as a patient receiving 2 units/episode, adjusting for number of hospital days, conditioning intensity and donor type.

Impact of RBC Transfusion Practice on Transfusion Reactions and (TRM)

The number of transfusion reactions per patient was similarly rare in both groups with a mean of 0.07 (standard deviation [SD]: 0.3 reactions/patient) for those receiving 2 units and 0.05 (SD: 0.21 reactions/patient) for those receiving 1 unit per transfusion episode. The number of transfusion reactions per RBC unit transfused was 6 of 613 units (0.0098 reactions/unit; 95% CI 0.0045–0.0211) for those receiving 2 units and 4 of 527 units (0.0076 reactions/unit; 95% CI 0.0030–0.0194) for those receiving 1 unit per transfusion episode. The cumulative incidence of 180-day TRM was similar between those receiving 2 units (25%; 95%CI 16–35%) and those receiving 1 unit (19%; 95%CI 12–28%) per transfusion episode (p=0.39). There were too few events to perform a multivariable analysis of TRM.

Impact of RBC Transfusion Practice on Blood Supply

While there seemed to be no significant change on the RBC transfusion burden for an individual patient, we sought to determine if differences in transfusion practice (1 vs. 2 units/episode) could be potentially relevant from a blood supply perspective by studying the density of transfusions per 1000 patient-days. The RBC transfusion density for patients receiving 2 units/episode was 240 units transfused/1000-patient-days in contrast to 193 units transfused/1000-patient-days for patients receiving 1 unit/episode, resulting in a reduction of 47 units transfused/1000-patient-days and cost saving of US $ 47,000/1000-patient-days. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

Impact of RBC Transfusion Practice on Platelets (PLT) Transfusion Burden

In an exploratory analysis, we found that there was a correlation between the number of RBC and PLT units transfused and sought to determine if that change in RBC transfusion practice had any effect on the number of platelet units transfused. As shown on Table 3, the two independent predictors of a lower number of platelets unit transfused were shorter length of hospitalization and reduced intensity conditioning.

Compliance with Transfusion Guidelines

In the group of patients that received 2 units/episode there were 334 transfusions episodes in the studied period. In the 334 transfusion episodes, 67 (20%) received 1 unit, 259 (78%) patients received 2 units, and 8 (2%) received 3 or more units per episode. As expected, there was an increase to 503 transfusion episodes for patients treated in the 1 unit/episode policy period. Of those, 482 (95%) patients received 1 unit, 18 (4%) received 2 units and 3 (1%) received 3 or more units per episode. Thus, compliance with the new 1 unit per episode policy was high.

Impact of Change in RBC Transfusion Practice on Self-Reported Nurse Workflow

We considered whether the change in RBC transfusion practice could have adversely impacted BMT unit RN’s workflow by requiring more frequent blood checks and a second transfusion episode on the same day. In order to evaluate how this guideline change impacted the RN workflow, we carried out a voluntary anonymous survey for RNs who worked in the BMT unit during the whole study period from July 2015 to June 2017. Fifty of 90 nurses responded to the survey. We found that 39 (78%) felt that it positively affected the workflow, 10 (22%) were neutral, and 1 nurse felt it adversely impacted the workflow because patients needed RBC transfusion on consecutive days. There were 3 nurses (6%) who elaborated on the improvement in the workplace as it allowed for timely administration of scheduled medications that would have been incompatible with co-administration of other meds and blood products.

DISCUSSION

Blood component transfusions are a critical supportive measure for patients undergoing allogeneic HCT. However, blood component supply is limited, there is potential for adverse events, and costs are significant. Thus, careful blood component utilization has been stressed as a way to optimize the cost effectiveness of this life saving support resource. In an attempt to improve utilization, we changed our practice from transfusing two RBC units/episode to one RBC unit/episode. In this retrospective analysis studying the impact of this guideline change on RBC utilization showed that: (1) there was no significant difference in the number of RBC unis transfused and the number of transfusion reactions for individual patients as compared to historical controls, (2) there was modest but potentially meaningful reduction in RBC utilization when considered transfused/1000-patient-day, and (3) there was a positive impact on RN workflow.

While we observed no significant change in the individual patient burden of RBC transfusions, we did observe a modest reduction in RBC unit utilization. Cohn et. al.14 has showed a 15% reduction in RBC utilization at the University of Minnesota, partly by reminding MDs to order 1 rather than 2 units/episode. Leahy et. al.3 reported a reduction in RBC utilization after the institution of a patient blood management (PBM) program. While they studied both patients hospitalized to receive intensive chemotherapy for acute leukemia and HCT, their study was larger and included a 4.5 year period. In both this and another study15 the year to year effect on RBC utilization was progressive with a reduction in almost half from the institution of the PBM to the end of the study period. Thus, it is possible that with longer follow-up the effect of our RBC transfusion guideline will have a greater impact on the RBC utilization in our center.

In our study only length of stay was an independent predictor of a higher RBC transfusion burden, with a quarter of our patients receiving no RBC transfusions in the study period. Kekre et.al16 found that male patients, higher baseline Hgb, and early stage disease had lower transfusions needs, but in their study only 10% of the patients did not require RBC transfusion. Our group previously reported a greater blood component utilization in cord blood recipients as compared to matched sibling peripheral blood stem cell transplantation 17. Study patient population differences, such as a larger number of patients undergoing cord blood transplantation, in our center were, at least in part, responsible for the difference between our findings and those of others.

Blood components are a scarce and expensive treatment resource. As suggested by our data, the development of uniform guidelines and close monitoring of blood component utilization may reduce heterogeneity and physician preference without impacting patient outcomes. Others have investigated the use of erythropoietin in order to reduce RBC transfusions, reduce transfusion associated risks, and reduce resource utilization 18, 19. However, modest efficacy, cost and risks associated with erythropoietin products kept this from being widely adopted.

Changes in supportive care guidelines, such as a change in the number of units transfused per episode, may also impact healthcare professionals’ workflow. Our survey of BMT inpatient unit nurses showed that most of those who responded felt it improved their workflow. As our data showed that patients getting a single RBC unit per episode required transfusions more frequently in consecutive days. However, each RBC transfusion involves frequent vital sign monitoring and close attention for compatibility with other intravenous medications. Thus, as stated by nurses that elaborated on how workflow improved, reducing to a single RBC unit per transfusion episode freed the nurse time to focus on other aspects of patient care and allowed for timely intravenous medication administration, which is busy and can be challenging in the early post-transplant course.

One other fact to consider is that some patients may have had HLA antibodies that could have confounded the results. The HLA antibody panel was only run when specifically requested, which is rare. These patients were usually being treated for being refractory to platelet transfusions. Since our study focused on RBC usage, HLA antibodies were not considered.

In summary, our study showed that the transfusion of a single RBC unit per transfusion episode resulted in only a modest reduction in RBC utilization, but that could result in a greater long-term impact on resource utilization. In addition, this change did not adversely impact patients and the practice guideline modification was perceived to have a positive impact on the workflow by the majority of the nursing staff. In future prospective studies, investigators could consider the impact on patients by assessing patients’ perception and satisfaction. As part of our blood management program, we will continue to monitor blood utilization as there may be a greater impact in the long-term.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by NIH grants P01 CA065493-20 (C.G.B.) from the National Cancer Institute, P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core shared resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Sources of support: NIH grants P01 CA065493-20 (C.G.B.) from the National Cancer Institute, P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core shared resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest for Claudia Cohn are: Ortho Clinical Diagnostics: Consulting, Fresenius Kabi (Fenwal): Honoraria, Cerus: Site PI for studies Octapharma: Site PI for study, Janssen Pharmaceuticals: Hornoraria. The other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2010 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. AHRQ 2010 (Updated 2013). [PubMed]

- 2.Gu Y, Estcourt LJ, Doree C, Hopewell S, Vyas P. Comparison of a restrictive versus liberal red cell transfusion policy for patients with myelodysplasia, aplastic anaemia, and other congenital bone marrow failure disorders. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2015; (10). doi: ARTN CD011577 10.1002/14651858.CD011577.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leahy MF, Trentino KM, May C, Swain SG, Chuah H, Farmer SL. Blood use in patients receiving intensive chemotherapy for acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the impact of a health system-wide patient blood management program. Transfusion 2017; 57(9): 2189–2196. e-pub ahead of print 2017/07/04; doi: 10.1111/trf.14191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters JH, Ness PM. Patient blood management: a growing challenge and opportunity. Transfusion 2011; 51(5): 902–903. e-pub ahead of print 2011/05/07; doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levings MK, Gregori S, Tresoldi E, Cazzaniga S, Bonini C, Roncarolo MG. Differentiation of Tr1 cells by immature dendritic cells requires IL-10 but not CD25+CD4+ Treg cells. Blood 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, Tinmouth AT, Marques MB, Fung MK et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB*. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(1): 49–58. e-pub ahead of print 2012/07/04; doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Healthcare Safety Network (HHSN). In: Prevention CfDCa, (ed), 2017.

- 8.Cleveland WS, Grosse EH, Shyu MJ. Local regression models. Statistical Models Chapman and Hall: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wickham H ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Springer-Verlag: New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S Fourth Edition edn Springer: New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data Wiley-Inter science: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 13.R-Core-Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing In. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohn CS, Welbig J, Bowman R, Kammann S, Frey K, Zantek N. A data-driven approach to patient blood management. Transfusion 2014; 54(2): 316–322. e-pub ahead of print 2013/06/19; doi: 10.1111/trf.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shehata N, Forster A, Lawrence N, Rothwell DM, Fergusson D, Tinmouth A et al. Changing trends in blood transfusion: an analysis of 244,013 hospitalizations. Transfusion 2014; 54(10 Pt 2): 2631–2639. e-pub ahead of print 2014/04/15; doi: 10.1111/trf.12644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kekre N, Christou G, Mallick R, Tokessy M, Tinmouth A, Tay J et al. Factors associated with the avoidance of red blood cell transfusion after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transfusion 2012; 52(9): 2049–2054. e-pub ahead of print 2012/02/11; doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solh M, Brunstein C, Morgan S, Weisdorf D. Platelet and red blood cell utilization and transfusion independence in umbilical cord blood and allogeneic peripheral blood hematopoietic cell transplants. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17(5): 710–716. e-pub ahead of print 2010/09/04; doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron F, Sautois B, Baudoux E, Matus G, Fillet G, Beguin Y. Optimization of recombinant human erythropoietin therapy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol 2002; 30(6): 546–554. e-pub ahead of print 2002/06/14; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox CP, Pacey S, Das-Gupta EP, Russell NH, Byrne JL. Low dose erythropoietin is effective in reducing transfusion requirements following allogeneic HSCT. Transfus Med 2005; 15(6): 475–480. e-pub ahead of print 2005/12/20; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tretino K,Farmer S, Swain S, Burrows S, Hofmann A, Ienco R, Pavey W, Daly F, Van Niekerk A, Webb S, Towler S, Leahy M. Increased hospital costs associated with red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion 2015; 55: 1082–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.