Abstract

Background and purpose:

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest cancer in women. The main challenge in the inhibition of ovarian cancer cells is chemo-resistance. Seeking to overcome this issue, several strategies have been suggested, including the administration of natural products. Grape seed extract (GSE) is a good source of polyphenols and its anticancer effects have been reported by many studies. In this study we aimed to evaluate the effects of GSE on OVCAR-3, a chemo-resistant ovarian cancer line.

Experimental approach:

OVCAR-3 cells were treated with GSE (71 μg/mL) for 24 and 48 h. Cell viability and cell apoptosis were measured by MTT and flow cytometry. The real-time polymerase chain reaction was used to determine the expression of genes involved in the cell cycle (PTEN, DACT1, AKT, MTOR, GSK3B, C-MYC, CCND1, and CDK4) and apoptosis (BAX, BCl2, CASP3, 8 and 9). The expression of CASP3 protein was evaluated by the CASP3 assay.

Findings / Results:

The results showed that treatment of OVCAR-3 cells with GSE, increased the expression level of PTEN and DACT1 tumor suppressor genes, as well as apoptotic genes, CASP3, 8, and 9 (P < 0.001). Also, the induction of tumor suppressor genes expression was associated with an increase in the expression of BAX/BCL2 gene ratio as pro- and anti-apoptotic genes. The expression of the genes involved in the cell cycle, CCND1 and CDK4, was inhibited (P < 0.001). The results indicated that GSE induced cell apoptosis in a time-dependent manner (P < 0.001). Also, the GSE treatment resulted in the CASP3 protein expression (P < 0.001).

Conclusion and implications:

According to the results of this study, GSE may exert anti-tumorigenic effects on chemo-resistant OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells which might be mediated by the expression of tumor suppressor genes that interact with cell signaling pathways, cell cycle, and cell apoptosis. Hence, the consumption of GSE extract during chemotherapy may overcome part of chemo-resistance in ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Chemo-resistance, Grape seed extract, Ovarian cancer

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynecological cancer. It accounts for 2.5 percent of all malignancies among females (1). The main treatment for ovarian cancer is surgery alongside the use of chemotherapy to kill the remaining cancer cells. Nevertheless, most patients become resistant to chemotherapy drugs such as paclitaxel, carboplatin, and cisplatin (2). Accordingly, researchers are seeking strategies to improve chemotherapy responses in ovarian cancer cells (3). The knowledge of medicinal plants has grown over the years, and the use of new medicines to overcome various human diseases has become common (4). Several studies indicated that natural products can overcome cancer cell drug resistance (5).

Grape seed extract (GSE) has shown anticancer activity in various types of human cancer including breast, prostate, bladder, lung, and colorectal cancers (6). GSE is mainly rich in polyphenols such as proanthocyanidins (7).

The anti-proliferation effects of GSE in oral cancer has been reported (8). Antitumor activity of GSE is also were observed in skin cancer (9). In colorectal cancer, it was suggested that GSE affects mitochondrial membrane potential, pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, and both caspase-dependent/independent apoptotic pathways (10). Despite known anticancer effects of GSE in some type of cancers, the precise mechanism of its function in ovarian cancer has not yet been defined.

To evaluate the GSE effects on ovarian cancer, we assessed phosphoinositide 3-kinases / protein kinase B / mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K / Akt / mTOR) that is one of the most investigated intracellular signaling pathway (11). This pathway is also one of the most frequently altered intracellular pathways in ovarian cancer and is activated in approximately 70% of ovarian cancer cases (12). The PI3K/Akt pathway is activated in a different type of cancers and is believed to play a pivotal role in cell survival signaling. A key point in Akt regulation is the down-regulation of the phosphorylated PI3K.

The phosphorylated form of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) deleted on chromosome ten is a driver gene that is involved in this pathway. PTEN is a frequently occurring tumor suppressor associated with ovarian cancer. It negatively regulates PI3K by the dephosphorylation of PIP3 that lead to PI3K/Akt phosphorylation. PTEN itself becomes phosphorylated and so strongly suppressed by the activation of PI3K/Akt (13). It is suggested that GSE suppresses PTEN phosphorylation and in this way increases its negative regulation on the PI3K pathway (14). Induction of PTEN gene expression can inhibit the growth of ovarian cancer cells, stopping their cell cycle in the G1 phase through down- regulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and inducing the apoptotic process (15). Saito et al. suggested the fundamental roles of the PTEN gene in the development of ovarian tumors (16). PI3K is also suppressed by mTOR. mTOR, a downstream gene in PI3K/Akt pathway, is a serine/threonine-protein kinase that acts through 2 distinct complexes: mTORC1-raptor and mTORC2-rictor. mTORC1 acts by influencing on pivotal translation-regulating factors. It is believed that the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is a potential predictor of invasiveness in ovarian cancers (17).

Dapper antagonist of catenin-1 (DACT1) is another tumor suppressor gene that plays a role in down-regulating cell cycle and inhibiting cancer cell growth by decreasing nuclear β-catenin levels. Expression of DACT1 can inhibit the growth and proliferation of ovarian cancer cells by increasing glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3B) and inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (18). β-catenin signaling acts as an inducer for cell proliferation in different cancers. It is involved in cell-cell adhesion and Wnt signal transduction (19). β-catenin signaling targets cyclinD1 (CCND1) and C-MYC, and mediate the progression of the cell cycle (20). Cyclin D1 is a protein required for progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. C-MYC is a proto-oncogene and a cell master regulator. In human colorectal cancer, GSE inhibits cell growth, induces G1 phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and modulates cell cycle regulators (21).

There are two main apoptotic pathways including the extrinsic and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway (22). It is suggested that GSE induces apoptosis through B-cell lymphoma 2-associated X protein (BAX) and caspase3 (CASP3) pathways (23). The OVCAR-3 is a cell line consisting of androgen and estrogen receptors. This cell line was established for the first time from the malignant ascites of a patient with progressive adenocarcinoma of the ovary. The cells are histologically similar to the patient’s original cells.

The patient has been received a combination of chemotherapy drugs and demonstrated resistance to in vitro clinically relevant concentrations of these drugs. In addition to preference using this cell line let scientists evaluate the effects of other anticancer products on drug resistance in cancer of ovary (24). In this study, we aimed to assess the effects of GSE on chemo-resistant OVCAR-3 in promoting cell cycle and apoptosis, and evaluate part of the relevant cellular mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds and reagents

GSE powder was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in 1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); 10 mg/mL stock solution and diluted by Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM / F12) as desired concentration. The final concentration of DMSO in the test solutions was less than 0.1% the mixture was heated 30 min in 70 °C, centrifuged 10 min at 1800 rpm, and sterilized using a 0.22 μm syringe filter (Milipore, USA). It stored at - 20°C until used. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and streptomycin-penicillin were procured from (Sigma, USA). PBS, ethanol (95%), and 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol- 2yl) -2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Cell lines and cell culture

The ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR-3 was purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran. All cells were seeded into 25-cm2 flasks with DMEM/F12 medium (Falcon, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% FBS supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2. At 80% confluency, cells were trypsinized and incubated for downstream experiments. OVCAR-3 cells were passaged every 2-3 days.

Experimental groups

OVCAR-3 cells were assigned into six groups including 1 and 2 control groups (cells in normal condition with no treatment for 24 and 48 h); 3 and 4 DMSO groups, cells treated with DMSO as solvent of GSE for 24 and 48 h; and 5 and 6 GSE groups, cells treated with GSE at IC50 (71 μg/mL) for 24 and 48 h.

The IC50, the concentration of GSE that inhibits half-maximal proliferation of OVCAR-3 cells, were determined as follows: 10,000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated overnight. Then cells were treated with a 200 μL serial dilution of GSE (10 to 250 μg/mL) for 24 h. Assays included blank wells containing medium only, untreated control cells, and test cells treated with GSE at different concentrations. Afterwards, cells got through MTT assay to determine the cell viability rate. IC50 curve then were drawn.

MTT assay and determination of cell viability assays

The cytotoxicity effect of GSE was determined by MTT assay. Ten thousand cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated overnight. Next, cells were treated with GSE and DMSO for 24 and 48 h. For controls, the cells were incubated only with the medium. Each group was repeated in 6 wells. At the end of treatment, the cell viability rate was evaluated by MTT assay. The absorbance in each well was measured at 570 nm wavelength in a microtiter plate reader (Hiperion, Germany). The reference wavelength was higher than 650 nm. The blanks were given values close to zero (± 0.1).

Apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry

OVCAR-3 cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates and treated for 24 and 48 h. Annexin V and Propidium iodide (PI) staining were performed followed by flow cytometry. The cells were trypsinized and washed with PBS. After adding the binding buffer, the cells were treated with 5 μL of annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and then washed with washing buffer. Finally, 200 μL buffer and 5 μL PI were added to the cells and apoptotic OVCAR-3 cells were counted by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) (25).

CASP3 activity assay

CASP3/CPP32 fluorometric assay kit (BioVision, Catalog # K105-25, USA) was utilized to evaluate the activity of CASP3. At the end of treatment, cells were trypsinized and washed with PBS. The pellet of cells suspended in 50 μL of chilled cell lysis buffer. Then 50 μL of 2× reaction buffer (containing 10 mM DTT) added to each sample. Next, cells were incubated on ice for 10 min. Subsequently, 50 μL of 2× reaction buffer, 1 μL of dithiothreitol (DTT, 1 M), and 5 μL of DEVD-AFC (1 mM) were added to the cell lysates.

The reactions were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Finally, 50 μL of cell lysates were transferred into a 96 well plate and the absorbance was read using a fluorometric spectrophotometer (Multiple Reader Synergy H1, USA) with 400 nm excitation and 505 nm emission filters.

Evaluation of genes’ expression

The expression level of the genes of interest in this study was determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Total RNA from the cells of different treatment groups was extracted using the YTA Total RNA Purification Mini kit (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, I.R. Iran) according to the manufacturer protocol. After treatment with DNase I to remove genomic DNA, cDNA was reverse transcript using Revert Aid ™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, USA).

Maxima SYBR Green ROX qPCR Master Mix kit (Fermentas, USA) used according to the manufacturer’s protocol in an ABI Step One Plus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The cycling parameters were as follows: 10 min at 95 °C for initial denaturation, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation step at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing/extension for 1 min at 60 °C. β-actin (ACTB) was used as a reference gene for internal control. Data were analyzed by the comparative Ct (ΔΔct) method. These experiments were carried out in triplicate and were independently repeated at least 3 times (26). Gene-specific primer sequences are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of primers used in this study.

| Genes | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| PTEN | ACCAGTGGCACTGTTGTTTC | TCCTCTGGTCCTGGTATGAAG |

| DACT1 | CCCCAAATCTGCAGATGTG | TGACGGCATCTAGCTCAGATC |

| AKT | TCTTTGCCGGTATCGTGT | TGTCATCTTGGTCAGGTGGT |

| MTOR | TCCGAGAGATGAGTCAAGAGG | TCCCACCTTCCACTCCTATG |

| GSK3β | TGTCAAGTTGTATATGTATCAGC | AATACAGCAGTATCAGGATCC |

| C-MYC | GCGACTCTGAGGAGGAACAAG | TCCAGACTCTGACCTTTTGCC |

| CDK4 | TCTTTGACCTGATTGGGCTG | CCATCTCAGGTACCACCGAC |

| CCND1 | ACAAACAGATCATCCGCAAACAC | TGTTGGGGCTCCTCAGGTTC |

| BAX | GGAGCTGCAGAGGATGATTG | GTCCAATGTCCAGCCCATG |

| BCL2 | AAAATACAACATCACAGAGGAAG | CTTGATTCTGGTGTTTCCC |

| CASP3 | AGCACTGGAATGACATCTCG | ACATCACGCATCAATTCCAC |

| CASP8 | ACTGGATGATGACATGAACCTG | GCTGAATTCTTCATAGTCGTTG |

| CASP9 | CCTTTGTTCATCTCCTGCTTAG | CCTCAAACTCTCAAGAGCACC |

| β-actin | TTCGAGCAAGAGATGGCCA | CACAGGACTCCATGCCCAG |

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times and the data are expressed as mean ± SD. Comparison between groups was done using One-way ANOVA test followed by Post hoc Tukey test and P values < 0.05 were considered significant. All data were statistically analyzed by SPSS software version 23.0.

RESULTS

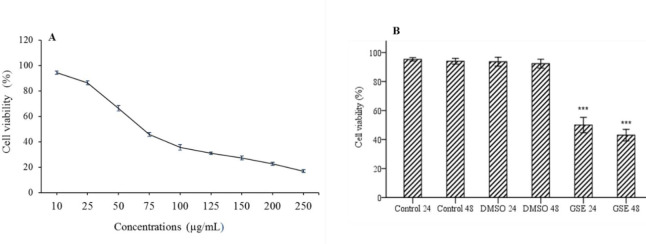

Cytotoxicity effect of grape seed extract

The treated cells evaluated by MTT assay to determine the cell viability rate and IC50 curve were drawn according to the obtained results. Based on the depicted curve, the concentration of 71 μg/mL corresponded to 50% cell viability of the OVCAR-3 cells following treatment with GSE and was considered as IC50 of GSE in this study (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

(A) The Effect of GSE on the viability of OVCAR-3 cells. The cells were incubated with different concentrations (10-250 ug/mL) of GSE for 24 h. Cell viability was measured with MTT assay. Based on the results, IC50 of GSE was in the range of 71 μg/mL; (B) effect of different treatments on OVCAR-3 cells viability.***P < 0.001 indicates significant differences compared to the corresponding DMSO group GSE, Grape seed extract; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Inhibition of OVCAR-3 cell growth by grape seed extract

GSE significantly (P < 0.001) decreased the viability of the cells after 24 h (50.01 ± 2.75%) and 48 h (43.04 ± 1.91%) (Fig. 1B).

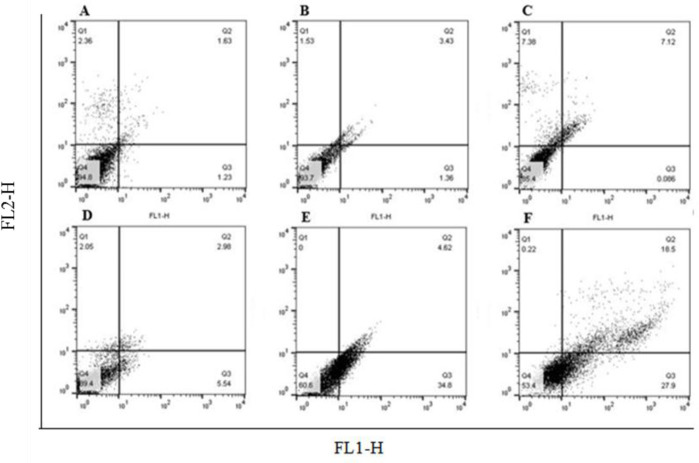

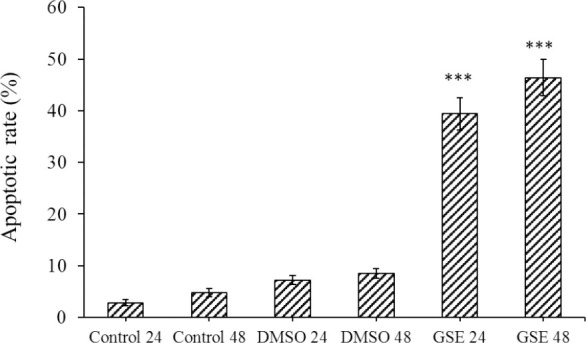

Annexin V assay and flow cytometry

As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, compared to the DMSO-treated cells, the rate of apoptotic cells after 24 h of treatment with GSE at 71 μg/mL was 39.4 ± 3.1% and for 48 h was 46.4 ± 3.5% (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

The effects of GSE on cell apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry. Treatment with GSE at 71 μg/mL for 24 and 48 h, significantly induced apoptosis in OVCAR-3 cells compared with the DMSO treated cells. (A and B) Control, cells without treatment with any substance in 24 and 48h respectively; (C and D) cells treated with DMSO as solvent of GSE for 24 and 48 h, respectively; and (E and F) cells treated with GSE at 71 μg/mL for 24 and 48 h, respectively. P < 0.001 indicates significant differences compared to the corresponding DMSO group GSE, Grape seed extract; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide

Fig. 3.

The effect of GSE on the apoptotic cell in different groups evaluated by flow cytometry. P < 0.001 indicates significant differences compared to the corresponding DMSO group GSE, Grape seed extract; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

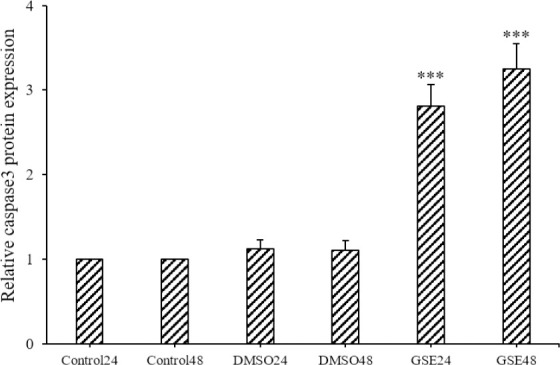

CASP3 activity assay

The protein expression of CASP3 in the OVCAR-3 cells was measured to ensure cell death with apoptosis. Caspase colorimetric assay indicated that the protein expression levels of CASP3 in the GSE-treated groups compared to the DMSO-treated group was increased significantly (P < 0.001). However, the difference between the GSE-treated groups was not significant at different times (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Protein expression of caspase3 in different groups evaluated by caspase colorimetric. ***P < 0.001 indicates significant differences compared to the corresponding DMSO group GSE, Grape seed extract; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

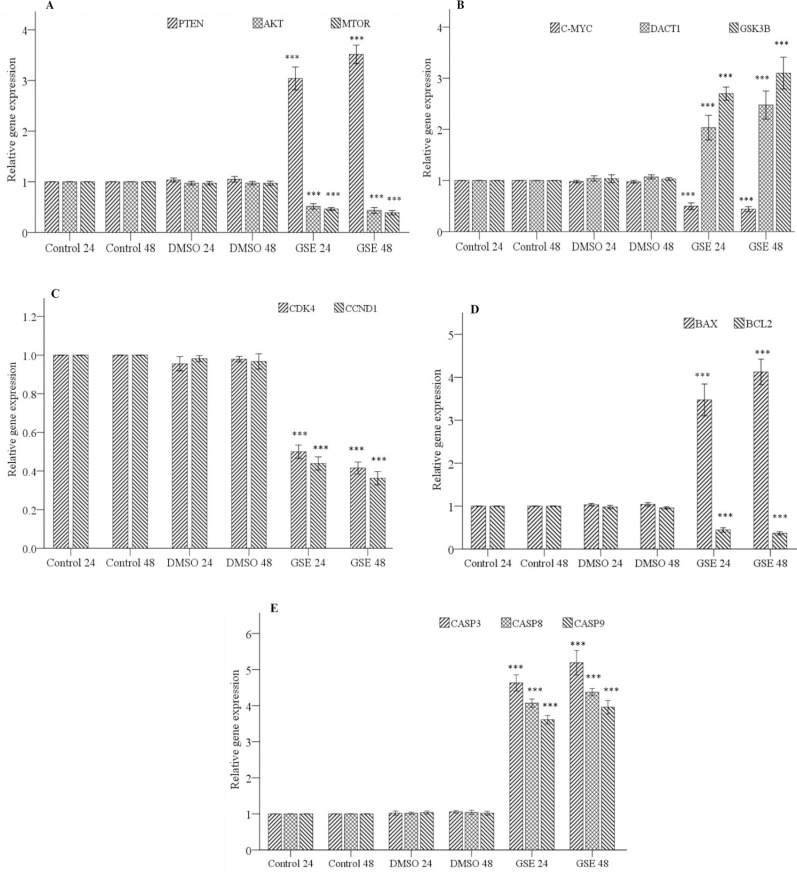

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was used to evaluate the effects of GSE on the expression level of genes involved in cell cycle and apoptosis process. The result showed that treatment with GSE at IC50 increases the expression level of PTEN and DACT1 tumor suppressor genes and consequently affected the expression level of downstream genes such as AKT, MTOR, GSK3B and C-MYC that involved in cell growth and proliferation (P < 0.001, Fig. 5A and B). Genes involved in cell cycle including CCND1, cyclin-dependent kinase4 (CDK4) were significantly decreased following GSE treatment in OVCAR-3 cells compared to their respective control cells (P < 0.001, (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

The effects of GSE on the expression level of genes involved in the signaling pathway, cell cycle, and apoptosis process evaluated by real-time polymerase chain reaction. (A) The expression level of genes involved in PI3K/ AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (PTEN, AKT, and mTOR) in different groups; (B) the expression level of genes involved in Wnt/ β-catenin signaling pathway (DACT1, GSK3B, and C-MYC) in different groups; (C) the expression level of genes involved in the cell cycle (CDK4 and CCND1) in different groups; (D) the expression level of pro- and anti-apoptotic genes (BAX and BCL2) in different groups; (E) The expression level of genes involved in the apoptotic process(CASP3, CASP8, and CASP9) in different groups. *P < 0.001 indicates significant differences compared to the corresponding DMSO group GSE, Grape seed extract; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinases; AKT, protein kinase B; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue; DACT1, dapper antagonist of catenin-1; GSK3B, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; CDK4, cyclin dependent kinase4; CCND1,catenin signaling targets cyclinD1; BAX, B-cell lymphoma 2-associated X protein, BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CASP3, caspase3.

The result indicated that GSE up-regulates the expression of BAX pro-apoptotic gene and down-regulates the expression of BCL2 anti- apoptotic gene (P < 0.001, Fig. 5D). Also showed that treatment with GSE leads to increase expression of CASP genes involved in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway (P < 0.001, Fig. 5E).

DISCUSSION

This research aimed at evaluating the biological effects of GSE on OVCAR-3, an ovarian cancer chemo-resistant cell line. To achieve this aim, we evaluated the effects of GSE on one of the most investigated intracellular signaling pathway, the PI3K/AKT/MTOR (27). Given the aberrant activation of PI3K/AKT/MTOR in some cancers and the involvement of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in the PI3K/AKT/MTOR signaling pathway, we investigated the alteration of PTEN expression in OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cell line to evaluate its role in tumorigenesis.

PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene that its inactivation in some cancer cell lines is associated with increasing the PI3k/AKT pathway activity (28). According to the reports, GSE induces the inhibitory effect of PTEN on the PI3K/AkT pathway in colon cancer cell lines (29). Barbe et al. concluded that anticancer effects of GSE is due to increasing of reactive oxygen specious by down- regulation of several molecular pathways including PI3K/AKT, MAPK Kinas, and NF- KB (30).

In one study conducted by Takaei et al. the overexpression of PTEN in ovarian cancer cells suppressed the growth of tumors and increased survival time in mice with the peritoneal disseminated tumor (15). Another study demonstrated that loss of PTEN in murine oviductal cells resulted in the invasion of cancerous cells to the ovary and induced hyperplasia and tumor formation in the ovary (31). Saito et al. suggested that the PTEN gene has a principal role in the development of ovarian tumors (16).

In our study, we figured out that treatment of the OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells with GSE leads to the induction of PTEN expression as well as reduction of the levels of AKT and MTOR genes, the components of the PI3K/AKT/MTOR signaling pathway. The significant reduction in cell growth and proliferation was seen following treatment with GSE, which can be attributed to the overexpression of PTEN and its inhibitory effect on the PI3K/AKT/MTOR signaling pathway.

Another tumor suppressor gene which plays an important role in inhibiting ovarian cancer cell proliferation and provoking apoptosis is DACT1. DACT1 regulates the cell cycle and inhibits cancer cell growth by decreasing nuclear β-catenin levels. It was reported that aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ovarian cancer leads to the hyperactivity of β-catenin (32). Li et al. suggested that overexpression of DACT1 in type one epithelial ovarian cancer, reduced its expansion and cis- platinum resistance by controlling canonical Wnt signaling and autophagy (18).

In our study we concluded that GSE induced the upregulation of DACT1 in OVCAR-3 cells that is in agreement with the results of the abovementioned studies. Several reports showed that GSK3B was frequently phosphorylated and inactivated in epithelial ovarian cancer (33). It has been determined overexpression of DACT1 by enhancing the activity of GSK-3β reduced the level of nuclear β-catenin and also the Wnt/β-catenin target genes such as C-MYC (18). Activation of GSK3B suppresses tumorigenesis by down- regulation of CCND1 expression and cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells (34). Based on the results of the present study we concluded that administration of GSE leads to the upregulation of DACT1 and GSK3B genes and downregulation of C-MYC gene. This may indicate the inductive effects of GSE on Wnt signaling pathway and its subsequent influences on C-MYC expression. Hence, inhibiting Wnt signaling pathway may decrease the resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapy.

It has long been suggested that C-MYC amplification is a common finding in advanced stages of ovarian cancer (13). It also has been recently proven that MYC status is a determinant of synergetic drug response in ovarian cancer (35). The expression of CDK4 and CCND1 genes also were assessed in the present study. It was reported that in advanced serous epithelial ovarian cancer, overexpression of CCND1 led to a poor prognosis (11).

CDK4 gene has an important role in the cell cycle. Several preclinical studies have shown that CCND1-CDK4/6 is a necessary factor for maintaining the tumorigenic potential of cancer cells (35). It has been suggested that GSE induces apoptosis in bladder cancer cells by decreasing the expression of CCND1 and CDK4 (36). In agreement with these findings, the results of our study showed that treatment of OVCAR-3 cells with GSE resulted in a significant reduction in the expression levels of CCND1 as well as CDK4, 24, and 48 h after treatment.

To study the effects of GSE on the apoptotic pathway, the expression of CASP8 and 9 as well as CASP3 were evaluated. Agraval et al. suggested that in prostatic cancer GSE induces apoptosis via activation of caspases in companion with the destruction of mitochondrial membrane and releasing cytochrome C (37). In another study it was shown that anticancer effects of GSE in colon cancer are associated with differential modulation of pro- and anti- apoptotic proteins (10).

In our study, the significant overexpression levels of CASP8 and 9 as well as CASP3 genes were observed 24 and 48 h after treatment with GSE. In addition, CASP3 assay confirmed the overexpression of CASP3 protein following treatment with GSE. It is believed that enhancement in the BAX/BCL2 ratio is indicative of the initiation of the mitochondrial pathway apoptosis (35). It was reported GSE promotes its pro-apoptotic effects on colon cancer cells by reducing AKT and thereby inhibiting its effects on BAD and BCL2 (38). In line with these findings, the results of this study also indicated an increase in the BAX/BCL2 expression ratio. Also, it was suggested that treatment with BCL2 inhibitors improved the response to cisplatin in preclinical models of ovarian cancer studies (3). The results of our study demonstrated that the expression of CASP8 and 9, and CASP3 increased significantly compared to the control groups. The expression of CASP3 gene also confirmed by CASP3 protein assay. This may suggest that GSE exerts its apoptotic effects on OVCAR-3 cells by activating both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the results of this study showed that the treatment of OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells with GSE led to a reduction in cell growth and proliferation and induction of apoptosis process. GSE may render its anti-proliferative effects by provoking the augmentation of the PTEN and DACT1 genes expression and its subsequent effects on inhibition of PI3K/AKT/MTOR and Wnt/βcatenin signaling pathway. Also, GSE may exert its apoptotic effects on ovarian cancer cells by promoting both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

M. Homayoun contributed to the design, experimental studies, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. R. Ghasemnezhad Targhi assisted in data analysis, preparation, and editing of manuscript. M. Soleimani contributed to the concept, study design, manuscript preparation and revision.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was financially supported by the Vice-Chancellery of Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, I.R. Iran through the Grant No. 397361.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):284–296. doi: 10.3322/caac.21456. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pokhriyal R, Hariprasad R, Kumar L, Hariprasad G. Chemotherapy resistance in advanced ovarian cancer patients. Biomark Cancer. 2019;11:1–19. doi: 10.1177/1179299X19860815. DOI: 10.1177/1179299X19860815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A, Pius C, Nabeel M, Nair M, Vishwanatha JK, Ahmad S, et al. Ovarian cancer: current status and strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med. 2019;8(16):7018–7031. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2560. DOI: 10.1002/cam4.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Homayoun M, Seghatoleslam M, Pourzaki M, Shafieian R, Hosseini M, Bideskan AE. Anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects of Rosa damascena hydro-alcoholic extract on rat hippocampus. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2015;5(3):260–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang P, Yang HL, Yang YJ, Wang L, Lee SC. Overcome cancer cell drug resistance using natural products. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:767136,1–14. doi: 10.1155/2015/767136. DOI: 10.1155/2015/767136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinicola S, Cucina A, Antonacci D, Bizzarri M. Anticancer effects of grape seed extract on human cancers: a review. J Carcinog Mutagen. 2014;S8:1–14. DOI: 104172/2157-2518S8-005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi J, Yu J, Pohorly JE, Kakuda Y. Polyphenolics in grape seeds-biochemistry and functionality. J Med Food. 2003;6(4):291–299. doi: 10.1089/109662003772519831. DOI: 10.1089/109662003772519831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yen CY, Hou MF, Yang ZW, Tang JY, Li KT, Huang HW, et al. Concentration effects of grape seed extracts in anti-oral cancer cells involving differential apoptosis, oxidative stress, and DNA damage. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:94–102. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0621-8. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-015-0621-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaur M, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Anticancer and cancer chemopreventive potential of grape seed extract and other grape-based products. J Nutr. 2009;139(9):1806S–1812S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.106864. DOI: 10.3945/jn.109.106864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derry M, Raina K, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Differential effects of grape seed extract against human colorectal cancer cell lines: the intricate role of death receptors and mitochondria. Cancer Lett. 2013;334(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.015. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto T, Yanaihara N, Okamoto A, Nikaido T, Saito M, Takakura S, et al. Cyclin D1 predicts the prognosis of advanced serous ovarian cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2(2):213–219. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.194. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheaib B, Auguste A, Leary A. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34(1):4–16. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10289. DOI: 10.5732/cjc.014.10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalhoub N, Baker SJ. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelbrecht AM, Mattheyse M, Ellis B, Loos B, Thomas M, Smith R, et al. Proanthocyanidin from grape seeds inactivates the PI3-kinase/PKB pathway and induces apoptosis in a colon cancer cell line. Cancer Lett. 2007;258(1):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.08.020. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takei Y, Saga Y, Mizukami H, Takayama T, Ohwada M, Ozawa K, et al. Overexpression of PTEN in ovarian cancer cells suppresses ip dissemination and extends survival in mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(3):704–711. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0724. DOI: 101158/1535-7163MCT-06-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito M, Okamoto A, Kohno T, Takakura S, Shinozaki H, Isonishi S, et al. Allelic imbalance and mutations of the PTEN gene in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(2):160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasparri ML, Bardhi E, Ruscito I, Papadia A, Farooqi AA, Marchetti C, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer treatment: are we on the right track. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(10):1095–1103. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118907. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-118907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li RN, Liu B, Li XM, Hou LS, Mu XL, Wang H, et al. DACT1 Overexpression in type I ovarian cancer inhibits malignant expansion and cis-platinum resistance by modulating canonical Wnt signalling and autophagy. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9285–9296. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08249-7. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-08249-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olmeda D, Castel S, Vilaró S, Cano A. β-Catenin regulation during the cell cycle: implications in G2/M and apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(7):2844–2860. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0865. DOI: 10.1091/mbc.e03-01-0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velmurugan B, Singh RP, Kaul N, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Dietary feeding of grape seed extract prevents intestinal tumorigenesis in APCmin/+mice. Neoplasia. 2010;12(1):95–102. doi: 10.1593/neo.91718. DOI: 10.1593/neo.91718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao N, Budhraja A, Cheng S, Yao H, Zhang Z, Shi X. Induction of apoptosis in human leukemia cells by grape seed extract occurs via activation of JKN. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(1):140–149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1447. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruidering M, Evan GI. Caspase-8 in apoptosis: the beginning of “the end”. IUBMB life. 2000;50(2):85–90. doi: 10.1080/713803693. DOI: 10.1080/713803693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy AM, Baliga MS, Elmets CA, Katiyar SK. Grape seed proanthocyanidins induce apoptosis through p53, Bax, and caspase 3 pathways. Neoplasia. 2005;7(1):24–36. doi: 10.1593/neo.04412. DOI: 10.1593/neo.04412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Mezencev R, Bowen NJ, Matyunina LV, McDonald JF. Isolation and characterization of stem-like cells from a human ovarian cancer cell line. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;363(1-2):257–268. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1178-6. DOI: 10.1007/s11010-011-1178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schutte B, Nuydens R, Geerts H, Ramaekers F. Annexin V binding assay as a tool to measure apoptosis in differentiated neuronal cells. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;86(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00147-2. DOI: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Zhang W, Kong ZH, Ding DG. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by grape seed procyanidin extract in human bladder cancer BIU87 cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(15):3282–3291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porta C, Paglino C, Mosca A. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:64–74. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00064. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nero C, Ciccarone F, Pietragalla A, Scambia G. PTEN and gynecological cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(10):1458–1474. doi: 10.3390/cancers11101458. DOI: 10.3390/cancers11101458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milella M, Falcone I, Conciatori F, Cesta Incani U, Del Curatolo A, Inzerilli N, et al. PTEN: multiple functions in human malignant tumors. Front Oncol. 2015;5:24–37. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00024. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbe A, Ramé C, Mellouk N, Estienne A, Bongrani A, Brossaud A, et al. Effects of grape seed extract and proanthocyanidin b2 on in vitro proliferation, viability, steroidogenesis, oxidative stress, and cell signaling in human granulosa cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17):4215–4235. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174215. DOI: 10.3390/ijms20174215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo A, Czarnecki AA, Dean M, Modi DA, Lantvit DD, Hardy L, et al. PTEN loss in the fallopian tube induces hyperplasia and ovarian tumor formation. Oncogene. 2018;37(15):1976–1990. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0097-8. DOI: 10.1038/s41388-017-0097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen VHL, Hough R, Bernaudo S, Peng C. Wnt/β-catenin signalling in ovarian cancer: insights into its hyperactivation and function in tumorigenesis. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12(1):122–138. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0596-z. DOI: 10.1186/s13048-019-0596-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arend RC, Londoño-Joshi AI, Straughn JM, Jr, Buchsbaum DJ. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131(3):772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.09.034. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) in tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer lett. 2009;273(2):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.045. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niu Y, Xu J, Sun T. Cyclin-dependent kinases 4/6 inhibitors in breast cancer: current status, resistance, and combination strategies. J Cancer. 2019;10(22):5504–5517. doi: 10.7150/jca.32628. DOI: 10.7150/jca.32628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raina K, Tyagi A, Kumar D, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Role of oxidative stress in cytotoxicity of grape seed extract in human bladder cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;61:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.039. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agarwal C, Singh RP, Agarwal R. Grape seed extract induces apoptotic death of human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells via caspases activation accompanied by dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential and cytochrome c release. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(11):1869–1876. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1869. DOI: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang R, Yu Q, Lu W, Shen J, Zhou D, Wang Y, et al. Grape seed procyanidin B2 promotes the autophagy and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells via regulating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4109–4118. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S195615. DOI: 10.2147/OTT.S195615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]