Abstract

This article addresses the question of whether subsidizing an entirely new agricultural technology for smallholder farmers can aid its adoption early in the diffusion process. Based on a theoretical framework for technology adoption under subjective uncertainty, we implemented a randomized field experiment among 1,200 smallholders in Uganda to estimate the extent to which subsidizing an improved grain storage bag crowds-out or crowds-in commercial buying of the technology. The empirical results show that on average, subsidized households are more likely to buy an additional bag at commercial prices relative to the households with no subsidy who are equally aware of the technology. This suggests that under certain circumstances, such as when there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of a new agricultural technology, and the private sector market for the technology is weak or nascent, a one-time use of subsidy to build awareness and reduce risk can help generate demand for the new technology and thus crowd-in commercial demand for it. In this context, a subsidy can allow farmers to experiment with the technology and learn from the experience before investing in it.

JEL codes: C23, C93, O33, Q12, Q18.

Keywords: Crowding-in, hermetic technology adoption, RCT, subjective uncertainty, subsidy, Sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda

Over the years, donor agencies, development partners, and policymakers in developing countries have recognized and focused on the adoption of agricultural technologies such as improved varieties of seeds and inorganic fertilizer to enhance agricultural productivity, growth and development, and to reduce poverty (Gollin, Parente, and Rogerson 2002; Evenson and Gollin 2003). To accelerate diffusion of these technologies and enhance use, many countries subsidize these inputs. However, one of the key issues when subsidies are introduced becomes the extent to which they foster or hamper commercial market participation (Ricker-Gilbert et al. 2011; Mason and Ricker-Gilbert 2013). That is, to what extent does the subsidy crowd-in or crowd-out commercial purchases of the subsidized agricultural technology? For example, if the subsidized households go out and buy the technology commercially in the future, this means that the subsidy has a crowding-in effect. Conversely, if receiving the subsidy reduces future commercial purchases, then the subsidy crowds-out the commercial market.

Some development practitioners fear subsidies could negatively affect adoption in many ways. First, subsidy recipients may anchor on subsidized prices and be unwilling to purchase products at market prices post-subsidy (see Simonsohn and Loewenstein 2006 for an example of price anchoring in a different context), leading to crowding-out. Second, recipients may anticipate future subsidies, develop a sense of entitlement, and refuse to buy commercially. Third, subsidies could become a permanent policy, ultimately draining scarce resources.

However, for a new technology or an “experience good,” there is also the argument that a one-time or short-term subsidy can create awareness, help with the evaluation process—learning-by-doing—and provide information about the technology, thereby accelerating early adoption and the diffusion process.

The present article estimates the effects of a one-time subsidy on commercial market participation for an entirely new agricultural technology—hermetic (airtight) storage bags for maize and other grains—among smallholders in Uganda. We use a randomized controlled trial (RCT), where a set of households were randomly selected to receive one hermetic bag at no cost to them. Households were free to go out and purchase additional bags at commercial prices, regardless of whether they received a free bag. This allows us to estimate the causal effect of a subsidy on subsequent demand for the technology for those who received the subsidy compared to those who did not. In addition to the main hypothesis of crowding-in/out tested in this article, we also estimate if there are information/ spillover effects of the subsidy by examining the market participation outcomes for exposed households that did not receive the subsidy but live in an eligible local council one (LC1)—a group of one or more villages—where there was an extension demonstration that provided information about the bag and others in the LC1 received the subsidy/treatment.1 That is, do exposed households learn from their treated neighbors and go out and buy the bag at commercial prices at a higher rate compared to households in control villages where no demonstration took place?

Our article makes four important contributions to the literature on input subsidies for smallholder households. First, we contribute to the policy debate on the impact of subsidies on the adoption of new agricultural technologies. To date, most previous studies have focused on estimating crowding-in/out for subsidized production inputs such as improved seeds (Mason and Ricker-Gilbert 2013; Mason and Smale 2013) and inorganic fertilizer (Xu et al. 2009; Ricker-Gilbert et al. 2011; Jayne et al. 2013; Carter et al. 2014). Typically, these inputs are well known to smallholders and the risk from using them is relatively predictable. However, market participation is relatively low due to credit constraints, concerns about profitability from using such inputs, and/or lack of supply. As a result, it is difficult to cleanly estimate a crowding-in/out impact in the context where farmers are already aware and can buy technologies if they find it optimal to do so. We build on previous literature because knowledge and adoption of hermetic bags were virtually zero in our sample prior to the subsidy intervention, giving us a clean baseline from which to analyze crowding-in/out.

Second, we implement a large-scale RCT that estimates the causal effects of a one-time subsidy on crowding-in and crowding-out. This differentiates our work from studies that use observational data to control for endogeneity created by the fact that agricultural input subsidy programs in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are virtually always implemented in a non-random manner.2 The randomized subsidy implemented in this article allows us to make causal inference that is internally valid and does not depend on an exclusion instrument.

To date, there is little rigorous evidence using an RCT framework that shows how a one-time or short-term subsidy may influence the adoption of entirely new technologies in a developing country context, where modern diffusion channels such as the internet or TV are not easily accessible. One of the few notable exceptions is Dupas (2014), who finds that short-run subsidies for a new health product, an improved insecticide-treated bed net that is considered an experience good, impacts short-run and long-run adoption through learning effects. Bensch and Peters (2017) recently examined the effects of a one-time subsidy (a free stove) on the long-run adoption of improved cooking stoves in Senegal. These authors find that a one-time subsidy implemented six years previously increased a willingness to pay for the stoves among subsidy recipients.

Several previous studies have implemented RCTs for agricultural technologies in SSA. Duflo et al. (2011) implemented an RCT for subsidized fertilizer in Kenya, and Carter et al. (2014) did the same in Mozambique. In addition, Matsumoto et al. (2013) also conducted an RCT that provided fertilizer and hybrid seeds to smallholders in Uganda. In all three studies the inputs offered to participants were not widely available, but not unknown to the participants at the time of their study.

Our article is most closely related to Carter et al. (2014), who tested if temporary input subsidies for fertilizer spur learning-by-doing among recipients that leads to the longer-term adoption of the input. These authors find that the subsidy eliminates imperfect information among recipients and leads to increased adoption of fertilizer among subsidy recipients in the two seasons following their intervention. We build on this sparse body of literature using RCT to cleanly estimate crowding-in/out effects on a new agricultural technology in a place where prior exposure and knowledge was virtually non-existent prior to our intervention.3

Third, we investigate whether there are information effects of our subsidy intervention on the market participation outcomes for households who were exposed to training on hermetic bags but did not actually receive the subsidy intervention. With notable exceptions in Dupas (2014) and Carter et al. (2014), who find that information spills over to non-recipient neighbors, such indirect information effects of subsidy on neighbors who are non-subsidy recipients are seldom estimated. Our experimental setup allows us to measure these effects, which are important for sustained diffusion and adoption of the technology beyond the lifespan of a one-time subsidy intervention. For a subsidy to be cost effective, the learning experience derived by subsidy recipients from using the subsidized technology should diffuse informally to nonsubsidized households who live in the same LC1.

Finally, following a similar approach to that used in Koundouri et al. (2006), we incorporate subjective or endogenous uncertainty, which can be resolved through learning, into our technology adoption model for a risk-averse household. By subjective uncertainty, we mean that households may doubt if the technology is effective at keeping stored grains intact without the use of storage chemical protectants, and/or that households may lack confidence in their ability to use this innovative technology effectively to prevent storage losses. This kind of uncertainty is different from exogenous uncertainty such as weather patterns, price risk, unexpected government policies, or level of insect infestations, which is outside the control of households and cannot be resolved through learning.

The hermetic bag given to smallholders in our study has the capacity to hold 100 kilograms (kg) of shelled maize. These bags are better and more effective at protecting maize and other grains from insect attacks in storage than commonly used conventional storage technologies (including granaries and woven bags) and do not require farmers to use insecticides on stored grains to kill insect pests. The bags work by depleting oxygen levels that insects need to thrive. However, they are significantly more expensive than regular woven bags that hold the same amount of maize but offer no protection against insects (e.g., $2.50 for a hermetic bag and $0.50 for a woven polypropylene bag).4 Therefore, smallholders may be reluctant to pay the upfront cost for the technology. Nevertheless, given the positive characteristics of the technology, the information and learning effects derived from experience through a one-time subsidy could enhance market participation and adoption of the technology.5 Conversely, having received a bag for free one time could make recipients very sensitive to the price were they to go out and buy it commercially later, essentially leading to crowding-out effect.

Although we are unable to quantify the full benefits (vs. cost) of our subsidy intervention due to the follow-up occurring just one calendar year after the intervention, the potential learning and consequent adoption generated from the intervention may be sustained as recently demonstrated by Fishman et al. (2017) in Uganda. These authors used a novel randomized phase-out experimental design to determine if the adoption of improved seed inputs generated from a short-term subsidy program would be sustained beyond the intervention. These authors found sustained demand for the inputs even after the subsidy was phased out. Carter et al. (2014) also find a similar result of sustained one-time subsidy impacts on fertilizer use in Mozambique. Thus, a one-time subsidy may lead to sustained adoption of hermetic bags.

Furthermore, if a one-time subsidy leads to crowding-in effects for hermetic bags, the benefits may indeed generate other external effects, leading to crowding-in of other production inputs. For instance, Omotilewa et al. (2018) find that in Uganda, households with access to improved storage technology that reduces storage risk and losses are 10 percentage points more likely to cultivate high-yielding hybrid maize varieties, which are known to be vulnerable to insect pest attacks in storage. Similarly, a recent study by Emerick et al. (2016) in India also find that a new flood-tolerant rice variety, which reduces downside risk from flooding, increased agricultural productivity by crowding-in inputs such as fertilizer use and modern cultivation practices. Hence, beyond the potential primary benefit of a subsidy leading to crowding-in effects for hermetic storage bags, the adoption of the technology has the potential to increase agricultural productivity in general by crowding-in other modern inputs.

Storage Losses and Technologies in Uganda

Post-harvest losses in grain on-farm in SSA are estimated at approximately $4 billion annually (World Bank 2011). Because of the economic consequences associated with these losses in the region, as well as sustainability issues from using scarce resources to produce food that is wasted post-production, there is an increasing interest in post-harvest loss reduction in developing countries to enhance food and income security. The intervention evaluated in this article is designed to reduce losses during the storage component of the post-harvest value chain. In Uganda, 63% of the total grain post-harvest losses among smallholders are related to on-farm storage (World Bank 2011).

Although recent evidence suggests that farmer-reported grain storage losses in Uganda are relatively low, at less than 5% of total quantity harvested (Kaminski and Christiansen 2014), precise quantitative assessment of these losses are difficult due to high year-on-year variability in pest infestation (Costa 2015). Besides, anecdotal evidence suggests that smallholder households take measures including selling at harvest and the use of storage chemicals, among others, to reduce their losses. However, selling early to avoid storage losses may contribute to locking households into a cycle of poverty. After selling at harvest, these households are forced to buy grains later at higher prices to meet their consumption needs (Stephens and Barrett 2011). In addition, the use of synthetic chemicals may be toxic if used improperly. Hence, an effective and chemical-free storage technology has the potential to improve the status quo storage options for many smallholders.

Storage Technologies/Practices in Uganda

At study baseline, over 90% of households used conventional/traditional storage technologies/practices such as woven polypropylene bags, granaries, and heaping maize cobs on a bare floor. Overall, less than 1% of our sample used hermetic storage technologies of any kind at baseline. The most prominent storage technology used by about 73% of the households was regular woven polypropylene bags. These woven bags have a single-layer and oxygen can easily permeate through them, making grains stored in them vulnerable to insect pest attacks and exposure to storage diseases due to high absorption of moisture content. On the other hand, hermetic bags in this study prevent oxygen diffusion from the ambient environment, thanks to their two inner layers made from high-density polyethylene. Once insect pests lack access to oxygen for metabolism, they simply become inactive, desiccate, and die (Murdock et al. 2012).

In general, hermetic storage technologies have proven to be highly effective at preventing grain damage due to insect pest attacks in storage (Gitonga et al. 2013; Ndegwa et al. 2016). For instance, Gitonga et al. (2013) find that when compared to traditional storage methods, hermetic metal silos resulted in an almost complete elimination of losses due to insect pest. With a 1,800kg capacity silo, an average farmer saved up to 200kg of maize worth $130 in a season. Likewise, Ndegwa et al. (2016) estimated a grain damage drop from 14% to 4% between conventional storage practices and hermetic bags, a 71% reduction in losses.

Apart from the difference in functionality, both the regular woven and the hermetic bags share a cultural distinction that households can use them to store grains in-house. Because of this cultural similarity, acceptability should not be a barrier to adoption for the technology (Rogers 1995).

Data, Experimental Design, and Treatment Interventions

Data Collection and Sampling

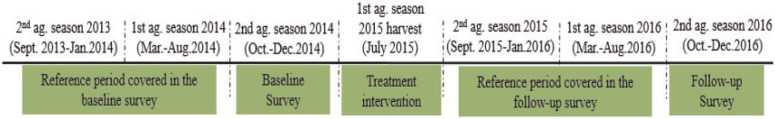

The data used for this article come from two waves of household surveys conducted among 1,200 maize and legume producers in Uganda. The first and second waves of data were collected from October to December 2014 and 2016, respectively, as baseline and follow-up surveys. Each wave of data covers two cropping cycles. The baseline survey covers the second cropping season of 2013 and first cropping season of 2014. The follow-up survey covers the same seasons in 2015 and 2016, respectively. Overall, the entire panel data covers four cropping seasons. The intervention (discussed below) occurred in July 2015, in between the two waves of survey data (see figure 1 for data and timeline details).

Figure 1. Study activities relative to agricultural cycles.

The survey instruments used in both surveys were structured, pre-tested questionnaires that included modules on the following: household demographic characteristics; crop production details; storage technologies used and postharvest grain management practices to preserve stored grains; and marketing activities at harvest and post-harvest periods. For the main outcome of this study, in both baseline and follow-up surveys we asked if households bought hermetic bag(s) commercially and from where they acquired it.

To select study participants, we used a multi-level stratified sampling approach. Our target population was smallholder maize and legume-producing households, and we wanted our data to have a semblance of national representation of these producers in Uganda. Therefore, we first identified the major maize- and legume-producing districts from within the four main agricultural regions in Uganda, excluding Kampala region, which is largely urban. Using previous data from the publicly available Living Standard Measurement Study-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) from the World Bank, we purposely selected two districts within each region, based on production volume from previous years. The districts are Bukomansimbi (Masaka) and Mubende in the central region without Kampala; Hoima, Kamwenge, and Kiryandongo in the west; Oyam and Apac in the northern region; and Iganga and Sironko (Mbale) in the eastern region.

Afterwards, within each district, we purposely selected three major maize-producing sub-counties with guidance from the District Agricultural/Production Officer. Subsequently, we randomly selected two parishes within each sub-county; and in each parish, we randomly selected one LC1 as the community cluster. Within each LC1, we randomly sampled twenty-five households using a random number generator to select from a list of community residents provided by the community leader, usually called the LC1 Chairman. Overall, at baseline, we randomly selected 48 LC1s and 1,200 (25 households*48 LC1s) smallholder households across the country. However, after data clean up, the number of households decreased to 1,190.

Experimental Design and Treatment Interventions

We use a two-level experimental design (see figure 2 for schematic representation). First, after the sampling and baseline survey in 2014, we randomly assigned each LC1 into treatment (the community receives a demonstration introducing the hermetic bags) or control (no demonstration). In our sampling framework, each sub-county has two LC1s and we randomly assigned one LC1 into a treatment LC1 and the other into a control LC1. The minimum distance between any pair was about 2km. In total, the LC1s were equally assigned (24 each) into both groups with an approximately equal number of households in the treatment and control LC1s. The treatment LC1s received awareness demonstrations about the hermetic bags, whereas the control LC1s did not receive any demonstration activity.

Figure 2. Experimental design.

The LC1-level treatment intervention was implemented by a Cooperative League of the USA (CLUSA) Uganda, a non-governmental organization engaged in activities to promote the technology in over 3,000 other LC1s across Uganda. The organization further engaged many smaller local partners to implement this exercise. In conjunction with CLUSA, we facilitated the training of trainers (TOTs) for both the local implementers as well as our enumerators. Thus, the local extension agents and our enumerators received the same training.

Importantly, all households living within the demonstration LC1s were invited to participate in the demonstration activities regardless of whether they were sampled as part of this study or not. The demonstration activities were designed to create awareness about the technology, and to instruct participants on how it works, how to use it effectively, and the potential benefits of using the technology for inter-temporal price arbitrage and food security purposes (see Baributsa et al. 2014 for more details on the demonstration activities). As such, we would expect the general awareness level about the technology to be higher within the demonstration LC1s than in the control LC1s.

Subsequently, we conducted the second experiment—the centerpiece of this study— at the household level. Within each of the treatment LC1s that had received information about the technology, we gave out a single 100kg-capacity Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) hermetic bag to 10 randomly selected households. These 10 households were selected from a sample size of 25 households per LC1, based on the baseline sampling (figure 2). That is, for a household to be eligible to participate in the household-level free bag treatment, that household must live within an LC1 assigned to receive demonstration activities.

In addition, to be certain that treated households who received subsidized bags understood how the technology works, our trained enumerators re-affirmed or instructed the households on how to use the technology effectively, regardless of whether they attended the LC1-level demonstration activities. Recall that our enumerators received just as much training as the local extension agents who implemented the LC1-level demonstration activities. Thus, the second experiment may be considered as the receipt of one subsidized bag plus a refresher instruction on how to use the technology properly. Importantly, however, other than the information provided on how to use the technology, which is essentially the same information equally provided at the LC1 level, our enumerators did not give further details or suggestions of where households could purchase the technology if they wanted to buy additional bags.

We chose to give just one free 100kg-capacity bag for two reasons: first, the intention was to use a bag as an evaluation tool to examine if it generates a positive learning experience leading to market demand among recipients. Second, we believe that a single hermetic bag valued at about $2.50 should not create an overwhelming undue financial advantage for treated households over their untreated neighbors.

In summary, our experimental design generated three groups of households. First, the group of households who lived in randomly assigned treatment LC1s and received the free bag subsidy (group 1 in figure 2). The second group (of exposed households) received no subsidy but lived within the demonstration LC1s (group 2 in figure 2). Lastly, the third group of households (pure control) lived in LC1s that did not receive a demonstration or a free bag subsidy (group 3 in figure 2). For the main analysis in this article, we restrict our comparison of subsidy effects to households in the demonstration LC1s only (groups 1 and 2); but as a robustness check (see the online supplementary appendix), we also report the full sample analysis including the non-demonstration LC1s (group 3) that did not receive any demonstration about the technology.

Importantly, unlike the Dupas (2014) study, which limited the purchase and sales of subsidized insecticide-treated bed nets solely to their program or study distribution channel, participants in our study could purchase the hermetic bags directly through the private market channel, which was developing at the same time LC1-level demonstrations were occurring to create awareness and demand for the bags. This makes our study a more realistic example of what happens in nascent markets in rural developing economies, where the supply chain is developing but the usual supply-side impediments apply.

Attrition Bias

In an experimental study, attrition bias could be problematic if the attrition rate is high, if attrition is unbalanced across treatments, or if attrition occurs in a non-random manner. From our baseline sample, 240 households were randomly treated with one hermetic bag in 2015, and we re-interviewed 233 of those in the follow-up survey in 2016. This implies an attrition rate of less than 3% in the treatment group. Within the exposed households in the demonstration LC1s (group 2 in figure 2), about 6% of them (21/356) dropped out.6 The overall attrition rate when both groups (1) and (2) are combined is under 5% of our baseline sample, suggesting a mild attrition rate. The major reason for attrition is that households migrated away from the sampled LC1s and our enumerators could neither trace nor contact them during the follow-up survey period.

To check if attrition is balanced across the treatment groups, we regressed a binary indicator of attrition on the treatment assignment indicator. Result suggests that the attrition rate is 3% higher in the exposed group than it is in the treatment group (table 1). Despite the slight attrition imbalance across the groups, there is no reason to believe that randomly receiving a bag or not influenced households’ decisions to move away (relocate) or stay. To better understand what factors predict attrition, we regressed the baseline outcome variable and some household characteristics on the same binary indicator of attrition (see online supplementary appendix table A1 for results). In general, the results suggest there is no systematic difference across attritted and returning households, ex ante. There is no statistically significant difference on the outcome variable within both groups and nearly all household variables such as income, education, ownership of assets, and production are random across both groups. However, we find a systematic difference across age and household size where, on average, attritted households are 7 years younger and one member less than the returning households are. These findings suggest that younger households with fewer family members are more mobile, and likely migrate in search of better opportunities.

Table 1. Baseline Randomization Balance Check between Treated Households and Exposed Households in Treatment LC1s.

| Variables | ControlMean (1) | SD(2) | TreatedCoeff.(3) | p-value (4) | N (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Outcome Variable(s) | |||||

| =1 if HH bought a hermetic bag (adopter) at baseline | 0.003 | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0.333 | 1,186 |

| Household Characteristics | |||||

| Age of household head (years) | 45.36 | 15.09 | 0.35 | 0.768 | 1,192 |

| Household size | 6.38 | 3.11 | 0.168 | 0.521 | 1,192 |

| =1 if female-headed household | 0.18 | 0.38 | -0.005 | 0.859 | 1,192 |

| =1 if polygamous | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.016 | 0.572 | 1,192 |

| =1 if HH head has any form of education | 0.89 | 0.31 | -0.008 | 0.721 | 1,192 |

| Total household revenue (‘000 UGX)a | 2280 | 4923 | -8 | 0.985 | 1,190 |

| =1 if HH has a radio | 0.78 | 0.42 | -0.008 | 0.800 | 1,188 |

| =1 if HH has a mobile phone | 0.70 | 0.46 | -0.019 | 0.689 | 1,188 |

| =1 if HH has a bicycle | 0.61 | 0.49 | -0.043 | 0.244 | 1,188 |

| Production and Storage Practices | |||||

| Total maize area (ha.) | 0.52 | 0.44 | -0.003 | 0.947 | 1,115 |

| Total quantity harvested-maize (kg) | 840 | 1071 | 45 | 0.645 | 1,115 |

| Total quantity of maize stored (kg) | 571 | 956 | 62 | 0.461 | 1,186 |

| Maize revenue (‘000 UGX) | 223 | 543 | 66 | 0.356 | 1,192 |

| Length of storage for consumption (weeks) | 14.72 | 9.75 | -1.12** | 0.016 | 1,192 |

| Expected storage loss (%) | 4.42 | 8.65 | -0.706 | 0.178 | 1,069 |

| =1 if traditional storage technology use | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.001 | 0.977 | 1,186 |

| =1 if hermetic storage technology use | 0.007 | 0.08 | -0.005 | 0.170 | 1,186 |

| Attrition | |||||

| =1 if attritted household | 0.059 | 0.24 | -0.030** | 0.034 | 1,192 |

Note: Columns 1 and 2 report baseline means and standard deviations for control households. Columns 3 through 5 report baseline results from OLS regressions comparing treated households with untreated households within demonstration LC1s. Each regression includes LC1 fixed effects to control for stratification, and robust standard errors are clustered at the LC1 level. Columns 3 and 4 report the OLS coefficient and p-value corresponding to the treatment dummy, and column 5 reports the sample size for each regression. Asterisks indicate the following:

***= p<0.01,

**= p<0.05

*,= p<0.1.

a=1USD = 2,800 UGX at baseline.

Despite the systematic differences across these two variables, we believe there is no threat to our design because of the relatively low rate of attrition, and there is no reason to believe these two variables were influenced by our randomly assigned treatment. In addition, we include both variables as covariates in our estimations and results are robust across specifications. Lastly, as a robustness check, we bounded our estimates following Lee (2009).

Theoretical and Analytical Framework

Technology Adoption under Uncertainty

Households in this study live in rural Uganda and face market failures for hermetic storage technology in the form of incomplete information, risk, and endogenous uncertainty, among others. To overcome this market failure, we provide information about the technology through demonstration activities at the LC1 level, as well as a 100% subsidy for the technology at the household level. Previous literature demonstrates that risk-averse farmers may delay partial or total adoption of a technology in the presence of incomplete information or uncertainty (Hiebert 1974; Dercon and Christiaensen 2011). We therefore examine subsidy as an economic incentive to induce faster adoption and early diffusion of a post-production technology.

The theoretical approach in this article assumes that smallholder farm households are risk-averse and that they maximize the expected utility of random profit (or wealth) following an approach similar to that used in Koundouri et al. (2006) and Saha et al. (1994). The “inputs” are grain quantities stored at harvest (qh) and the types of technologies used to store the grains: a vector of traditional technologies including storage chemicals, silos, or woven bags (x); or the new hermetic storage technology (xhermetic). Assuming a constant returns to scale “production” function f(.), the output (ql) is the quantity of intact grain in storage at a later time in the postharvest period.7 In general, for simplicity and because these are post-production decisions, we assume the quantity of grain stored is given and that households simply have to allocate grains to either conventional or hermetic storage technology. Hence, a farm household maximizes its expected utility of random profit as in equation (1), with the “output” function defined in equation (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

In the utility equation (1), pl, r, and rhermetic are the exogenous output price in the lean period that occurs some months after harvest and storage, the price vector associated with the cost of allocating grains in traditional storage technologies, and the price of the hermetic storage technology, respectively.8 The cost of allocating grains in traditional technologies include chemical and labor costs, and the cost of procuring the conventional technologies such as woven bags used. We further assume a concave and twice-differentiable utility function (U), and E is the expectation symbol.

In addition, the production function contains the term α(.), which is the household’s percentage of expected grain loss in storage (0 < α < 1) that indicates the level of effectiveness of any given storage technology used. Broadly, alpha is a function of storage technology used and incorporates some level of subjective uncertainty (ε) associated with the endogenous use of the technology. In our case, the subjective uncertainty comes from two potential sources. First, households may doubt the effectiveness of the technology and its ability to keep stored grains intact in the absence of storage chemical protectants as in other technologies. Second, households may be uncertain of their own ability to use this new technology properly to prevent storage losses.9 Hence, we refer to this type of uncertainty as endogenous. There is also a general exogenous inventory uncertainty—such as insect pest infestation in storage, price risk, or unexpected government policies—associated with inter-temporal transfer of grain from harvest to lean period, through storage. The households lack control over this second type of uncertainty, hence, we refer to it as exogenous. For simplicity and because exogenous uncertainty is common to all regardless of storage technology decisions, we ignore this uncertainty.

Substituting equation (2) into equation (1), the first-order conditions for use of hermetic storage technology is given by10

where , and . The equation (3b) equilibrium demonstrates that for a risk neutral household, the input/output price ratio equals the expected marginal product of the hermetic storage technology because the second term (covariance) on the right-hand side (R.H.S) of the equation essentially becomes zero. However, for a risk averse household, the second term is not equal to zero; rather, it captures the diversion from risk neutrality and is equivalent to the marginal risk premium associated with using the new technology.

To apply the general model above specifically to a household’s decision to participate in commercial purchase of the technology, we posit that a household will adopt the more efficient storage technology provided the expected utility derived from it is greater than the expected utility without the technology. Assuming a binary market participation/ adoption decision (1 represents adoption and 0 otherwise), where the expected storage losses from adopting the technology is much lower than otherwise, that is, , indicating better effectiveness if hermetic technology is used; then , where the expected utility maximizing problems and solutions are similar to the general model in equation (1) and (3), respectively. However, due to the subjective uncertainty associated with the use of hermetic technology and captured in the second term of the R.H.S in equation (3b), following Koundouri et al. (2006), we posit that households may delay adoption to obtain more information about the technology. Thus, an additional information premium (P) enters the adoption condition, particularly for a risk averse household, as shown below:11

Therefore, because a household’s choice of technology adoption is based on subjective probabilities (Feder et al. 1985; Saha et al. 1994), direct access to the technology in the form of a subsidy provides the ability to evaluate the technology, lowering the information premium among subsidy recipients. If positive experiential learning reduces subjective uncertainty associated with the technology, we would expect a positive movement in commercial market participation. However, if negative experiential learning occurs, there might be no or negative private market participation after having received a subsidized hermetic bag.

Empirical Framework: Modelling Direct Subsidy Effects

To estimate the effect of subsidized hermetic bags receipt on households’ subsequent commercial market participation for the technology, we compare the average outcome between subsidy recipients (group 1) and the exposed households (group 2) within the treatment LC1s. Since we observed each household before and after our intervention, we use the difference-in-difference (DiD) estimator.12 The DiD specification uses household-level panel data from before and after our subsidy intervention and adds the time subscript, t. It is estimated as follows:

where Yijt is a binary outcome variable that equals one if household i in LC1 j buys one or more hermetic bags commercially after the intervention, and zero otherwise; Subsidyi is a binary indicator variable that equals one if a household is treated (i.e., received a free bag), and zero otherwise; and postt indicates one if the observation is from the 2016 postintervention survey, and zero otherwise. The interaction term between this variable and whether a household gets treated is represented by Subsidyi∗postt. Parameters ϕ and κ estimate the coefficients associated with Subsidyi and postt, respectively. The main parameter of interest that estimates subsidy effects on whether a household buys hermetic bags commercially is τDiD, the coefficient on the interaction term. The estimated model estimated also includes a vector of household characteristics, X,ijt, such as age, sex, and education status of the household head, and size of the households to enhance precision, and the LC1-level fixed-effects, σj, to control for stratification following Bruhn and McKenzie (2009).13 The variable ∈ijt represents the idiosyncratic error term.

Empirical Framework: Modelling Information Effects

We estimate the empirical model for the information effects using an approach similar to that of the subsidy estimates inequation (5). The only difference is that we created a binary variable, Exposed, to replace the Subsidy variable. Exposed is equal to one if a household lives in a treatment LC1, where demonstrations about hermetic bags occurred but received no subsidy, and zero otherwise. This group of exposed households (group 2 in figure 2) is then compared with households in the non-demonstration LC1s (group 3 in figure 2) who had no contacts with the subsidized households in the demonstration LC1s.14 The variable Exposed should be uncorrelated with the error term in the regression equations because it is equally randomly assigned (see online supplementary appendix table A2 for a randomization balance check between exposed group 2 and pure control group 3). We present the estimated equation for the information effects as follows:

Like the previous specification, equation (6) represents the difference-in-difference (DiD) estimator. The variables retain their previous definitions as described in equation (5)). The new variable Exposedi∗postt is the interaction term between Exposed and the binary indicator for post-intervention, and γDiD represents the estimated information effects.

Results

To check for the randomization balance between subsidy recipients and non-recipients in the treatment village at baseline, we ex ante regress market participation and household and production characteristics on the treatment indicator, including LC1 fixed-effects in table 1. In columns (1) and (2), we present the baseline statistics for the group of exposed households living within the LC1s. Subsequent columns show regression coefficients indicating the ex ante mean difference between the randomly assigned group of treated subsidy recipients and the exposed group of households (as control), along with p-values for statistical significance of the coefficients.

The results from table 1 indicate that all the coefficient estimates (except for length of maize storage for consumption) are negligible and not statistically different from zero, suggesting that randomization was indeed successful at making the subsidy treatment exogenous. Second and most importantly, the self-reported expected storage loss is about 4.42% across both subsidized and exposed groups. The balance of this variable across treatment groups is important: if this variable were systematically different across groups, it would indicate that one group expects a higher level of losses, suggesting that the group could be more inclined to seek remedial technologies to reduce losses relative to the other group. Third, on average, private-sector market participation (i.e., number of households who bought hermetic bags at commercial price) was 0.3% (4 out of 1,200 households) at baseline. Furthermore, the average age of the household head is 45 years, household size is about six persons, 18% of the households are female-headed, and 16% are polygamous. The annual average household income is about 2.3m Ugandan Shillings, and most households have access to information through radio (78%) and mobile phone (70%).15 On maize production, the average annual area cultivated, quantities produced and stored are 0.52 hectares, 840kg, and approximately 571kg, respectively. These numbers show that households are indeed smallholders and that an average household would need about six (100kg) hermetic bags to entirely store their grains hermetically, indicating a potential for private market participation or investment beyond the one bag they were given for free. Lastly, the types of storage technologies used are balanced across both groups.

Direct Subsidy Effects on Commercial Market Purchases

Columns (1) and (2) of table 2 present the direct effect of the subsidy treatment (receiving a free bag) on the probability that a household buys an additional bag commercially after the treatment. We present the parsimonious estimate in column (1) before adding baseline covariates in column (2). Comparing coefficient estimates between the two columns suggests that adding covariates and locality fixed-effects in the regressions does not affect their magnitude. This supports the robustness of our results across specifications. The DiD estimates show that on average, direct recipients of subsidized bags were 5 percentage points more likely to buy at least one additional hermetic bag at commercial prices from a private retailer compared to households in the same LC1s who did not receive a free bag. The estimated parameters are statistically significant at p-value < 0.05 and are robust to potential attrition bias as the point estimates are statistically within the estimated Lee bounds (see online supplementary appendix table A3).

Table 2. . Direct and Information Effects of Subsidy on Purchase of Hermetic Bags.

| VARIABLES | Direct Effect | Information Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| =1 if HH received subsidized bag | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| =1 if exposed HH in treatment LC1 | 0.009 | 0.003 | ||

| but no subsidized bag received (Exposed) | (0.006) | (0.010) | ||

| Subsidy*post (τDiD) | 0.050** | 0.050** | ||

| (0.022) | (0.022) | |||

| Exposed*post (γDiD) | 0.033** | 0.033** | ||

| (0.015) | (0.015) | |||

| =1 if observation is post-intervention | 0.053*** | 0.053*** | 0.021** | 0.021** |

| (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Age of household head | 0.000 | –0.000 | ||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | |||

| =1 if HH head has any form of education | 0.008 | 0.004 | ||

| (0.013) | (0.008) | |||

| Household size | 0.003 | 0.002 | ||

| (0.003) | (0.001) | |||

| =1 if female headed household | –0.006 | 0.008 | ||

| (0.015) | (0.007) | |||

| LC1-level fixed effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Season binary indicators? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.009 | –0.030 | –0.035*** | –0.039*** |

| (0.006) | (0.025) | (0.000) | (0.012) | |

| Observations | 2,330 | 2,330 | 3,704 | 3,704 |

| R-squared | 0.073 | 0.077 | 0.058 | 0.061 |

Note: Columns (1) and (2) show the direct subsidy effect without and with covariates, respectively. ‘Subsidy*post’ (τdid) is the DiD estimate for direct effects. Columns (3) and (4) show the exposed effects without and with covariates, respectively. ‘Exposed*post’ (γdid) is the DiD estimate for the information effects. Robust standard errors, clustered at the LC1 level, are shown in parentheses. Asterisks indicate the following:

***= p<0.01

**= p<0.05

*= p < 0.1

Our findings show that receiving one subsidized bag crowds-in commercial market participation for recipients. These results are consistent with literature from studies using observational datasets in SSA, which have shown evidence of input subsidies leading to crowding-in where the private sector market for the input is nascent (Xu et al. 2009; Amankwah et al. 2016; Liverpool-Tasie 2014). For instance, Liverpool-Tasie (2014) find evidence of crowding-in of fertilizer subsidies on commercial market participation in Kano State, Nigeria, and Xu et al. (2009) in Zambia similarly finds that a fertilizer subsidy generates demand and crowds-in the private sector in poor areas with relatively inactive private sector. In our case, the private sector market activities for the hermetic bags were just being developed at the time of our intervention.

In addition, our results are consistent with learning effects found in Carter et al. (2014), who find that short-term subsidies alleviate imperfect information among input subsidy recipients, leading recipients to purchase fertilizer at commercial prices two years postsubsidy. Bensch and Peters (2017) also find that free improved stove recipients have a higher willingness to pay for the stoves six years after the subsidy. Furthermore, our results are also consistent with Dupas (2014), who finds that short-run subsidies for a new health product, an improved insecticide-treated bed net, increases short and long-run adoption through learning effects. The evidence from our findings suggests that a household’s personal experience derived from using the subsidized technology has a potential to increase short-term adoption through learning effects. Qualitative survey evidence further suggests that households who used the technology had a positive experience with it (online supplementary appendix table A4). Perceived benefits of the hermetic bag include eliminating the need for storage chemicals to kill insects, ease of use, better taste, and quality of maize stored in the bags.

Although the magnitude of our subsidy effect estimates might appear small at a 5 percentage point increase in the likelihood of purchasing an additional bag commercially, it is important to put this magnitude into perspective. First, this impact is measured after just one year (two agricultural seasons) following a one-time intervention for a brand-new technology. Second, the private market for the technology is nascent and supply-side is relatively underdeveloped. For instance, when asked why a household aware of the technology was not using it, many of them (63%) responded that they did not know where to buy it, implying that no vendor sold the bags in their locality (figure 3). This indicates a large supply-side constraint, suggesting that market participation may increase once the supply side catches up with unmet demand.

Figure 3. Reasons for not buying hermetic bags, if aware of it.

Note: 50% of the total sample are aware at the follow-up survey.

Third, in the two agricultural seasons postintervention, households experienced drought, leading to lower maize output than in a normal year. Relative to the baseline data, on average, households produced 360kg of maize less and stored 150kg less at follow-up. This suggests that reduced production and storage at follow-up could have reduced demand for the hermetic bags. We suspect that demand for the bags may increase following a good harvest. Lastly, relative to the speed of previous technology adoptions in Uganda, a 5 percentage point increase in adoption propensity is not bad after a year. For instance, Matsumoto and Yamano (2011) find that inorganic fertilizer and hybrid maize variety adoption in Uganda is 3% and 21%, respectively, relative to 74% and 59%, respectively, in Kenya, despite these technologies being available to smallholders for many years.

Information Effects on Commercial Market Purchases

Does this positive experience and market participation extend to others living within the treatment LC1s who did not receive the free bag subsidy? Columns (3) and (4) of table 2 present our estimates of the information effects that compare groups two and three in our experimental setup (figure 2). Overall, we find evidence of positive information effects on households purchasing hermetic bags commercially. The estimated effects show that living in a LC1 where others received a free bag and demonstrations occurred both increase the likelihood that an exposed household in that LC1 will participate in the market by 3.3 percentage points on average, relative to households in control LC1s that received no demonstration or free bags. The results are equally robust to controlling for household-level controls. Furthermore, we estimated Lee bounds (online supplementary appendix table A3) to examine potential attrition bias among exposed households but found no evidence of such bias, as our point estimate statistically lie within the bounds. Therefore, we interpret our estimated effects as the average effects of information on exposed households within the treatment LC1s compared tohouseholds in the control LC1s.

Nevertheless, these estimated information effects might in fact be partly or fully associated with demonstration activities (LC1-level trainings) to create awareness about the technology within the treatment LC1s.16 If so, it appears that experiential knowledge derived from receiving a free bag has a higher impact than the LC1-level information sessions about the bags as estimated in columns (3) and (4) of table 2. The direct effect of receiving a free hermetic bag on a household’s decision to purchase another bag at commercial price is about 1.5 times higher than the information effect of simply residing in an LC1 where a demonstration on the hermetic bag took place.

These estimated information effects, albeit smaller in magnitude, are crucial to sustained diffusion of the technology beyond the subsidy intervention and cost-effectiveness of subsidy. For a subsidized household, buying an additional hermetic bag indicates demand for a second bag, whereas for unsubsidized households, it reflects demand for their first hermetic bags, which may be an attempt by these households to evaluate the technology. This may help explain why market participation among subsidy recipients is nearly twice as much as the exposed households.

We acknowledge our inability to separate the whole information effects into whether they had come from information received through demonstration activities at the LC1 level, or through informal learning from subsidized households. Figure 4 shows the sources of awareness or learning about the technology from within each experimental group. The results indicate that while nearly 90% of the subsidized households (top graph) reported demonstration activities or direct contact with hermetic bag technicians as their main source of information, only 48% of the exposed households (middle graph) reported learning about the bags from the same sources. Thirty-four percent of the exposed group of households cited learning about hermetic bags from informal sources of information such as learning from other farmers, friends, or relatives. These percentages suggest that the information effects may have been divided almost equally into effects from both the LC1-level demonstration activities and informal learning from the treated households who constitute the other farmers, friends, and relatives source of information.

Figure 4. Sources of information about hermetic bags by experimental group (%), at follow-up survey in 2016.

Note: Each household may list up to two sources of information. Other sources include awareness through Radio/TV, other NGOs working in the area, market, input dealers and some unrelated government extension officers.

The bottom of figure 4 shows the sources of information about hermetic bags for the pure control group of households from LC1s with no training on hermetic bags. Thirty percent of these households are aware of the hermetic bags in the follow-up survey. The main sources of information for this group are “other sources” that include Radio/TV, NGOs, input dealers, village markets, etc. Forty percent of aware households in this group learned about the bags from these sources, while 27% of these households reported awareness through informal sources.17

Simple Benefits Cost Analysis

We compare the short-term benefits of the hermetic bag against its costs using findings in Omotilewa et al. (2018). Treated households reported a 2.4 percentage point reduction in storage losses within hermetic bags when compared to other technologies.18 Therefore, for a 100kg hermetic bag of maize, a 2.4kg of maize loss is abated. At an average lean period maize price of UGX 1,000/kg, the value of abated loss is UGX 2,400 ($0.86). Because the bags can last several seasons, similar to findings in Ndegwa et al. (2016), an average household in our treatment would have an additional UGX 7,200 ($2.60) over three seasons (1.5 years), which is higher than the cost of the bags at UGX 7,000 ($2.50). The households also benefit from not having to apply chemical insecticides to their food supply. Applying chemicals every three months to stored maize costs money and requires additional labor, adding to the benefits of hermetic bags. In addition, there are health benefits to reducing chemical insecticide use on food, and the hermetic bags help maintain maize that most believe to be of better taste and quality (online supplementary appendix table A4).

Other Potential Causal Pathway: Increased Maize Revenue

Other than evaluation and learning-by-doing from using a subsidized bag, another potential theory of change through which one might find increased purchases of hermetic bags among subsidy recipients is through an increase in maize revenue. While this pathway is plausible, we investigated it empirically but found no evidence to support it as a viable pathway, at least in the short run. Following a similar difference-in-difference empirical specification above, columns (1) and (2) in table 3 show there is no statistically significant increase in maize revenue among treated households.19

Table 3. . Direct Subsidy Effects on Maize Revenue and Length of Storage for Consumption.

| VARIABLES | IHS (Maize Revenue) | Length of storage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| =1 if HH received subsidized bag | –0.173 | –0.177 | –1.129** | –1.143** |

| (0.353) | (0.350) | (0.431) | (0.429) | |

| =1 if observation is post-intervention | –3.429*** | –3.371*** | –0.315 | –0.239 |

| (0.555) | (0.557) | (0.925) | (0.921) | |

| Subsidy*post (τDiD) | 0.756 | 0.753 | 2.407*** | 2.436*** |

| (0.546) | (0.543) | (0.756) | (0.758) | |

| Age of household head | –0.032** | –0.055*** | ||

| (0.014) | (0.018) | |||

| =1 if HH head has any form of education | 0.463 | 1.379 | ||

| (0.527) | (1.005) | |||

| Household size | 0.091 | 0.279*** | ||

| (0.077) | (0.089) | |||

| =1 if female headed household | –0.722 | 0.601 | ||

| (0.447) | (0.790) | |||

| LC1-level fixed effects? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Season binary indicators? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 11.406*** | 11.769*** | 14.621*** | 13.552*** |

| (0.349) | (0.936) | (0.464) | (1.420) | |

| Observations | 2,330 | 2,330 | 2,330 | 2,330 |

| R-squared | 0.158 | 0.169 | 0.127 | 0.140 |

Note: Table 3 compares treated households (group1) with exposed households (group2) in treatment villages. Columns (1) and (2) show the DiD estimates of the treatment effects on the log of maize revenue without and with covariates, respectively. ‘Sub*post’ (τDiD) is the parameter of interest. Columns (3) and (4) show similar DiD estimates of the treatment effects on length of storage for consumption without and with covariates, respectively. Robust standard errors, clustered at the LC1 level, are shown in parentheses. Asterisks indicate the following:

***= p<0.01,

**= p<0.05,

*= p < 0.1. Maize revenue was transformed using Inverse Hyperbolic Sine (IHS) transformation.

We speculate that the increase in commercial purchase of hermetic bags among subsidy recipients was not due to an increase in maize revenue/income for the two reasons. First, we gave out a single 100kg capacity bag per treated household, which did not increase their storage capacity in any significant way. The average storage capacity for sampled households in our study was 1,800kg. Second, on average, subsidy recipients stored for about 2.5 additional weeks longer than their untreated neighbors as shown in columns (3) and (4), table 3. That is, treated households increased their storage period for consumption by an additional 20%, suggesting that they might be more consumption-oriented, and might have substituted the regular woven bag with the effective hermetic bag to store grains for household consumption.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This article evaluates the use of an economic policy tool—a one-time subsidy— among smallholders in Uganda to create incentives to enhance commercial market participation or adoption of hermetic storage bags. We use a randomized controlled trial to estimate the direct effects of subsidy and information effects on the commercial purchase of this new product, providing new experimental and empirical evidence for rigorous evaluation in a developing country context. Although the hermetic technology evaluated is culturally similar to the regular woven polypropylene storage bags used by a majority of the households prior to our intervention, it is more effective at preventing insect pest attacks in stored grains without the use of chemical insecticides. However, it is five times more expensive than a regular woven bag that offers no protection against insects. Therefore, smallholders may be reluctant to purchase the technology due to its upfront cost and uncertainty about its effectiveness or their ability to use it properly.

The empirical findings from this study are as follows. First, the receipt of a one-time subsidy in the form of one free hermetic bag increases the likelihood of a household purchasing a bag in the commercial market by 5 percentage points, on average (statistically significant at p-value <0.05). Second, evidence of an information or spillover effect of a onetime subsidy exists among exposed households who did not get a free bag but live in LC1s where others received the intervention and training demonstrations on the bags occurred. However, at 3.3 percentage points (statistically significant at a 5% level), the information effect is lower in magnitude relative to the direct subsidy effects. Lastly, we performed robustness checks (see online supplementary appendix) that lend credence to the consistency and unbiasedness of the estimated effects.

What do we learn? In a developing country context where modern diffusion channels such as TV or internet are not readily accessible, we provide previously missing empirical evidence that a short-term subsidy for a new and unknown agricultural technology may enhance learning and experimentation with the new technology in a lower-risk environment. This finding should provide evidence to reduce the common development practitioners’ fear of creating a “subsidy syndrome” by providing a free input or technology to limited-resource rural households in the developing world. Thus, our article buttresses previous work in Dupas (2014) and Carter et al. (2014), which both showed that a short-term subsidy for an experience good can spur demand and adoption through learning.

To be clear it is important to note that we find the subsidy crowded-in commercial demand for the hermetic bags likely because the technology was completely new to participants and we only gave them one bag that could hold a maximum of 100 kilograms of shelled maize (enough to preserve about one-sixth of the average household’s stored maize), and were told that they would not receive any more bags for free. Therefore, there was potentially excess demand from households to go out and buy additional bags to store more of their maize. This context is different than other studies in SSA, particularly those evaluating crowding-in and crowding-out of seed and fertilizer subsidies in Malawi and Zambia (Ricker-Gilbert et al. 2011; Mason and Ricker-Gilbert 2013). Participants in those large-scale, government-run subsidy programs received large quantities of inputs at a reduced price, while at the same time commercial markets for the inputs existed. Thus, those studies find that subsidies crowd-out the commercial market in that context.

The main policy implication from this study is that a one-time or short-term subsidy may be an effective tool at spurring demand for a new agricultural technology. In this case, the subsidy creates a positive experiential learning effect that reduces the level of uncertainty associated with the adoption of the technology. Provided there is a persistent learning effect such as demonstrated in Fishman et al. (2017), demand for the technology should be sustained beyond the subsidy intervention. Moreover, we need to consider that the supply-side of the market for this technology is underdeveloped at the time of this study, perhaps due to an insufficiently dense network of agricultural input retailers. Hence, subsidy effects on market participation may potentially be larger in the long run once supply-side constraints are relaxed.20 In addition, because early adopters of the technology provide information and learning that affect subsequent potential adopters, there could be a positive externality generated by subsidizing these early adopters.

Though we have identified a short-term benefit of our subsidy intervention on subsequent purchases of hermetic bags, we are yet to quantify the full benefits of the intervention because it is relatively early to do so. Long-term benefits may include higher adoption rates and informal information spillover effects, increased grain income/revenue, a reduction of chemical insecticides on stored grains that could lead to other potential health benefits and, potentially, a better price premium from grains stored in hermetic bags.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Local council one is the lowest administrative unit in Uganda and it sometimes comprises more than one village. The other administrative units, in hierarchical order, are region, district, sub-county and parish.

One of the few notable exceptions isDuflo et al. (2011), who implemented a randomized experiment on standard fertilizer subsidies, free delivery, and timing of fertilizer purchase among smallholders in Western Kenya. Others include Matsumoto et al. (2013) and Carter et al. (2014), on improved seeds and fertilizer, respectively.

A very small number of households (4) out of nearly 1,200 in the sample had purchased the technology at baseline. This handful of households lived in a district (Kiryandongo in Western Uganda) where there was a pilot project with hermetic bags and were randomly picked up in our sample.

Although the initial upfront cost of the hermetic bags is relatively high, it is more durable than the regular bags and lasts longer if handled carefully. In addition, households no longer need to apply storage chemicals at intervals on grains stored, which saves on chemical and labor costs. Over the bag’s lifetime, it presumably has a higher return than the regular bags (see Jones et al. 2014).

Other than evaluation and learning from experience, another potential pathway towards increased commercial purchase of the technology among subsidy recipients is through increased endowment in maize income or revenue. We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out. Empirically, however, we did not find this to be the case, likely because we only gave out a 100kg capacity bag that did not increase storage capacity in a significant way, or because households are more consumption-oriented. We discuss this pathway later in this article.

We acknowledge that typically, attrition rates tend to be higher among control groups in RCTs because people may lie that someone has moved when in fact they just did not want to be surveyed. However, in our case, identification of local farmers was done through the local village leaders (LC1 Chairmen). We usually visited the LC1 Chair the day prior to our interview and produce a list of our intended respondents (two years after the baseline survey). At this point the leader informs us whether anyone has moved, and there is no reason for these leaders to lie on behalf of the farmers.

If the hermetic bags were efficient and identical in their ability to preserve grains, one would expect a linear relationship between the quantities of undamaged grains in storage at the lean period (ql ) and the number of hermetic bags used. In addition, production is in quotation marks because it is an analog of traditional production function where inputs are used to produce an output.

Although households may doubt the technology or their ability to use it correctly due to a lack of experience, the technology is risk reducing if used correctly. This case is different from the typical exogenous uncertainty associated with other agricultural inputs such as fertilizer use, which may depend on exogenous rainfall.

We focus our attention solely on the hermetic technology allocation simply because the FOCs for both storage technologies can be solved independently of each other and hence are separable.

We think of P as the value of information that is both related to uncertainty associated with technology use, as well as the cost of the technology.

As a robustness check, we used additional estimators such as a simple difference estimator that uses cross-sectional post-intervention data only, and a fixed-effects (FE) estimator that exploits the panel (baseline and follow-up) nature of our data. These estimators produce equivalent results to DiD estimates.

The results are available in the online supplementary appendix associated with this article (see tables C1 and C2).

As a robustness check, table C3 in the online supplementary appendix compares results when regional fixed-effects are included vs. LC1 fixed-effects. We found no difference in both specifications.

The minimum spatial distance between any pair of treatment and control LC1s was 2km, and ranges up to 15km. Typically, the pairs are located within the same sub-county, which is two levels of administrative unit above the LC1 or LC1 level. Hence, the two groups are close enough for similarity but far enough to avoid contamination from subsidy recipients.

At baseline in 2014, 1 USD¼2,800 UGX.

We acknowledge that an indirect effect or demonstration may not only have resolved subjective uncertainty issues for risk averse (or even risk neutral) exposed farmers; it could also be the case that the demonstration resolves some questions about where to buy the bags, but we have no data on this.

The implementing partner, CLUSA Uganda, inadvertently implemented some LC1-level demonstrations in six of the pure control (non-demonstration) LC1s. This explains why 12% reported knowing about hermetic bags through demonstrations. In addition, few of the trained extension agents were entrepreneurial and tried marketing the bags in some control LC1s where they lived. That accounts for the 22% who reported knowing through hermetic technicians in the pure control LC1s. This may lead to an underestimation of our indirect effect estimates if control households bought hermetic bags from these agents.

For more information on the point estimates, statistical significance, and empirical model used to estimate storage losses abated from the use of a single 100kg hermetic bag, see Omotilewa et al. (2018).

We used Inverse Hyperbolic Sine (HIS) transformation of maize revenue. IHS transformation is ideal over log transformation because of its ability to map zero to zero and still perform as log transformation (see Bellemare et al. 2013 for additional examples).

Given that farmers can reuse the bags over multiple seasons, it is also possible that the long-term impacts on continued commercial purchase of the technology may be limited for a farmer who has already adopted the technology. We thank one anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

We made the assumption of a common price for all grains in the lean period regardless of whether they were hermetically stored or not. At this point, we have no evidence that hermetically stored grains command a higher price premium. Previous literature from Benin (Kadjo et al. 2016) and Ghana (Compton et al. 1998) suggests there is little or no price premium on grain quality marketed in the lean period when grains become scarce.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material are available at American Journal of Agricultural Economics online.

References

- Amankwah A., Quagrainie K.K., and Preckel P.V.. 2016. Demand for Improved Fish Feed in the Presence of a Subsidy: A Double Hurdle Application in Kenya. Agricultural Economics 47 (6): 633–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baributsa D., Abdoulaye T., Lowenberg-DeBoer J., Dabiré C., Moussa B., Coulibaly O., and Baoua I.. 2014. Market Building for Post-Harvest Technology through Large-Scale Extension Efforts. Journal of Stored Products Research 58: 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare M.F., Barrett C.B., and Just D.R.. 2013. The Welfare Impacts of Commodity Price Volatility: Evidence from Rural Ethiopia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 95 (4): 877–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bensch G., and Peters J. 2017. One-Off Subsidies and Long-Run Adoption—Experimental Evidence on Improved Cooking Stoves in Senegal. ZEF—Discussion Papers on Development Policy 235. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn M., and McKenzie D. 2009. In Pursuit of Balance: Randomization in Practice in Development Field Experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1 (4): 200–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carter M.R., Laajaj R., and Yang D.. 2014. Subsidies and the Persistence of Technology Adoption: Field Experimental Evidence from Mozambique. NBER Working Paper 20465.

- Compton J.A.F., Floyd S., Magrath P.A., Addo S., Gbedevi S.R., Agbo B., Bokor G., et al. 1998. Involving Grain Traders in Determining the Effect of Post-Harvest Insect Damage on the Price of Maize in African Markets. Crop Protection 17 (6): 483–9. [Google Scholar]

- Costa S.J. 2015. Taking It to Scale: Post-Harvest Loss Eradication in Uganda 2014–2015. UN World Food Programme, Kampala, Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon S., and Christiaensen L.. 2011. Consumption Risk, Technology Adoption and Poverty Traps: Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Development Economics 96 (2): 159–73. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo E., Kremer M., and Robinson J.. 2011. Nudging Farmers to Use Fertilizer: Theory and Experimental Evidence from Kenya. American Economic Review 101 (6): 2350–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dupas P. 2014. Short-Run Subsidies and Long-Run Adoption of New Health Products:Evidence from a Field Experiment. Econometrica 82 (1): 197–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerick K., de Janvry A., Sadoulet E., and Dar M.H.. 2016. Technological Innovations, Downside Risk, and the Modernization of Agriculture. American Economic Review 106 (6): 1537–61. [Google Scholar]

- Evenson R.E., and Gollin D.. 2003. Assessing the Impact of the Green Revolution, 1960 to 2000. Science 300 (5620): 758–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder G., Just R.E, and Zilberman D.. 1985. Adoption of Agricultural Innovations in Developing Countries: A Survey. Economic Development and Cultural Change 33 (2): 255–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman R., Smith S.C., Bobié V., and Sulaiman M.. 2017. How Sustainable Are Benefits from Extension for Smallholder Farmers? Evidence from a Randomized Phase-Out of the BRAC Program in Uganda. IZA Discussion Paper Series IZA DP No. 10641. [Google Scholar]

- Gitonga Z.M., De Groote H., Kassie M., and Tefera T.. 2013. Impact of Metal Silos on Households’ Maize Storage, Storage Losses and Food Security: An Application of a Propensity Score Matching. Food Policy 43: 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gollin D., Parente S., and Rogerson R.. 2002. The Role of Agriculture in Development. American Economic Review 92 (2): 160–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert L.D. 1974. Risk, Learning, and the Adoption of Fertilizer Responsive Seed Varieties. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 56 (4): 764–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne T.S., Mather D., Mason N., and Ricker-Gilbert J.. 2013. How Do Fertilizer Subsidy Programs Affect Total Fertilizer Use in Sub-Saharan Africa? Crowding Out, Diversion, and Benefit/Cost Assessments. Agricultural Economics 44 (6): 687–703. [Google Scholar]

- Jones M., Alexander C., and Lowenberg-DeBoer J.. 2014. A Simple Methodology for Measuring Profitability of On-Farm Storage Pest Management in Developing Countries. Journal of Stored Products Research 58: 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kadjo D., Ricker-Gilbert J., and Alexander C.. 2016. Estimating Price Discounts for Low Quality Maize in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Benin. World Development 77:115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski J., and Christiaensen L.. 2014. Post-Harvest Loss in Sub-Saharan Africa—What Do Farmers Say? Global Food Security 3 (3): 149–58. [Google Scholar]

- Koundouri P., Nauges C., and Tzouvelekas V.. 2006. Technology Adoption under Production Uncertainty: Theory and Application to Irrigation Technology. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 88 (3): 657–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.S. 2009. Training, Wages, and Sample Selection: Estimating Sharp Bounds in Treatment Effects. Review of Economic Studies 76 (3): 1071–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liverpool-Tasie L.S.O. 2014. Fertilizer Subsidies and Private Market Participation: The Case of Kano State, Nigeria. Agricultural Economics 45 (6): 663–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mason N.M., and Ricker-Gilbert J.. 2013. Disrupting Demand for Commercial Seed: Input Subsidies in Malawi and Zambia. World Development 45: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mason N.M., and Smale M.. 2013. Impacts of Subsidized Hybrid Seed on Indicators of Economic Well-Being among Smallholder Maize Growers in Zambia. Agricultural Economics 44 (6): 659–70. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T., and Yamano T.. 2011. Optimal Fertilizer Use on Maize Production in East Africa. In Emerging Development of Agriculture in East Africa, eds. Yamano T., Otsuka K., and Place F.. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T., Yamano T., and Sserunkuuma D.. 2013. Technology Adoption and Dissemination in Agriculture: Evidence from Sequential Intervention in Maize Production in Uganda (No. 13–14). Tokyo, Japan: National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock L.L., Margam V., Baoua I., Balfe S., and Shade R.E.. 2012. Death by Desiccation: Effects of Hermetic Storage on Cowpea Bruchids. Journal of Stored Products Research 49: 166–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ndegwa M.K., De Groote H., Gitonga Z.M., and Bruce A.Y.. 2016. Effectiveness and Economics of Hermetic Bags for Maize Storage: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial in Kenya. Crop Protection 90: 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Omotilewa O.J., Ricker-Gilbert J., Ainembabazi J.H., and Shively G.. 2018. Does Improved Storage Technology Promote Modern Input Use and Food Security? Evidence from a Randomized Trial in Uganda. Journal of Development Economics 135: 176–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker-Gilbert J., Jayne T.S., and Chirwa E.. 2011. Subsidies and Crowding Out: A Double-Hurdle Model of Fertilizer Demand in Malawi. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 93 (1): 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E.M. 1995. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saha A., Love H.A., and Schwart R.. 1994. Adoption of Emerging Technologies under Output Uncertainty. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 76 (4): 836–46. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsohn U., and Loewenstein G.. 2006. Mistake# 37: The Effect of Previously Encountered Prices on Current Housing Demand. Economic Journal 116 (508): 175–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens E.C., and Barrett C.B.. 2011. Incomplete Credit Markets and Commodity Marketing Behaviour. Journal of Agricultural Economics 62 (1): 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank 2011. Missing Food: The Case of Postharvest Losses in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington DC: World Bank, Report No. 60371—Africa Region. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Burke W.J., Jayne T.S., and Govereh J.. 2009. Do Input Subsidy Programs “Crowd In” or “Crowd Out” Commercial Market Development? Modeling Fertilizer Demand in a Two-Channel Marketing System. Agricultural Economics 40 (1): 79–94. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.