Abstract

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most common cause of death from gynecological tumors. Most patients with advanced ovarian cancer develop recurrence after concluding first-line therapy, making further lines of therapy necessary. The choice of therapy depends on various criteria such as tumor biology, the patientʼs general condition (ECOG), toxicity, previous chemotherapy, and response to chemotherapy. The platinum-free or treatment-free interval determines the potential response to repeat platinum-based therapy. If patients have late recurrence, i.e. > 6 months after the end of the last platinum-based therapy (i.e., they were previously platinum-sensitive), then they are usually considered suitable for another round of a platinum-based combination therapy. Patients who are not considered suitable for platinum-based chemotherapy are treated with a platinum-free regimen such as weekly paclitaxel, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), gemcitabine, or topotecan. Treatment for the patient subgroup which is considered suitable for platinum-based therapy but cannot receive carboplatin due to uncontrollable hypersensitivity reactions may consist of trabectedin and PLD. While the use of surgery to treat recurrence has long been a controversial issue, new findings from the DESKTOP III study of the AGO working group have drawn attention to this issue again, particularly for patients with a platinum-free interval of > 6 months and a positive AGO score. Clinical studies have also shown the efficacy of angiogenesis inhibitors such as bevacizumab and the PARP inhibitors olaparib, niraparib and rucaparib. These drugs have substantially changed current treatment practice and expanded the range of available therapies. It is important to differentiate between purely maintenance therapy after completing CTX, continuous maintenance therapy during CTX, and the therapeutic use of these substances. The PARP inhibitors niraparib, olaparib and rucaparib have already been approved for use by the FDA and the EMA. The presence of a BRCA mutation is a predictive factor for a better response to PARP inhibitors.

Key words: recurrent ovarian cancer, ROC, surgery for recurrence, PARP inhibitor, anti-angiogenesis

Introduction

According to cancer statistics, epithelial ovarian cancer is the most common cancer-related cause of death from gynecological tumors in women and the fifth most common tumor 1 .

Considerable progress has been made in recent years in treating recurrent ovarian cancer, both in terms of the available drug therapies and surgical treatment.

Primary cancer mortality has decreased by 30%. Mortality has decreased from 10/100 000 to 6.7/100 000; in parallel, the incidence also decreased from 16/100 000 to 11/100 000. This largely explains the reduction in mortality rates 1 . Around 70 – 80% of patients with FIGO stage III – IV disease develop recurrence within 5 years 2 , 3 .

Traditionally, the platinum-free interval (PFI) was used almost exclusively to differentiate recurrent ovarian cancer into platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant recurrence, with this differentiation used to make decisions about further drug treatment or surgery. Patients who developed recurrence > 6 months after the end of platinum-based chemotherapy were classified as platinum-sensitive. Patients who initially responded to treatment but then developed recurrence < 6 months after the end of platinum-based chemotherapy were referred to as platinum-resistant. Platinum-sensitive patients have a higher probability of responding to a new platinum-based therapy 4 . However, platinum sensitivity is a continuum without a strict time cut-off. This differentiation is therefore currently considered to be outdated. The Ovarian Cancer Consensus Group of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup has changed this definition for the first time and the ESMO-ESGO have followed suit. According to the most recent consensus recommendations from the ESMO/ESGO 2019, the description of the therapy-free interval should be based on whether the last therapy was platinum-based, non-platinum-based or biological 2 , 5 , 6 . Moreover, the various treatment criteria need to be differentiated and taken into account when deciding on further treatment. Such criteria should include the tumor biology/histology, the number of previous therapies, the response to previous therapies, persistent side effects of previous therapies, current symptoms and, of course, the patientʼs own wishes 7 .

Following this paradigm change, patients are now categorized into those for whom repeat platinum-based therapy would be possible and those for whom platinum-based chemotherapy is out of the question.

When evaluating the tumor biology, it is important to consider the germline BRCA status and the tumorʼs BRCA status. Previous treatment with bevacizumab or other previous maintenance therapies are also decisive criteria. It is also important to discuss which patients are less likely to benefit from systemic therapy, e.g., patients with an extremely poor prognosis, patients with histological subtypes such as clear-cell, mucinous, low-grade serous tumors, and asymptomatic patients with rising CA 125 after initially responding to first-line therapy 8 .

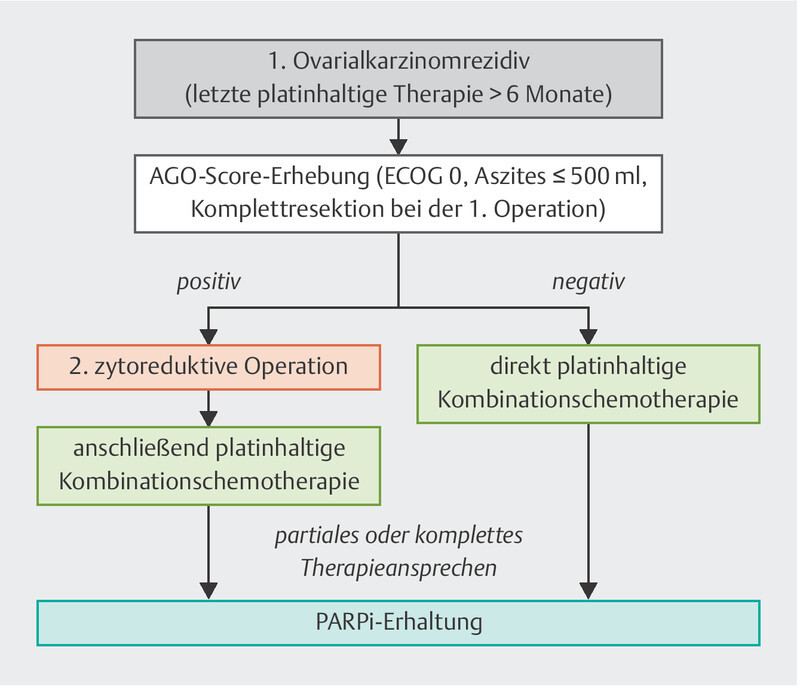

Surgery to treat ovarian cancer recurrence is an additional option under specific conditions. This possible option should be considered before starting systemic therapy ( Fig. 1 ). After many years of controversy, the latest data from the DESKTOP III study from ASCO 2020 show a significant benefit in terms of a longer overall survival for a select group of patients 9 .

Fig. 1.

Treatment of ovarian cancer recurrence (therapy-free interval > 6 months). PARPi: PARP inhibitors.

This review presents and discusses the latest findings on the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, particularly the option of a second cytoreductive operation (recurrence surgery), the treatment of patients with platinum-resistance and platinum-sensitivity, the administration of PARP inhibitors or antiangiogenetic agents, and new therapies.

Surgery for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

Surgery to treat recurrent ovarian cancer has been controversially discussed for many years. The discussion moved center stage again by the results of the DESKTOP III study 9 . In principle, it is important to differentiate between the two quite different aims associated with recurrence surgery: palliation with the aim of controlling symptoms (e.g., to prevent mechanical ileus) and cytoreduction which aims to achieve macroscopic tumor clearance in order to prolong disease-free and overall survival.

The latter aim is discussed below.

The DESKTOP study series was initiated by the AGO to systematically examine, for the first time, the effect of cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer on disease-free survival and overall survival rates. The DESKTOP I and II studies showed that only patients with macroscopically complete resection appeared to benefit from this approach.

To be able to predict the success of macroscopic tumor resection, a score based on clinical factors, the so-called AGO score, was used for the first time in the DESKTOP study series 10 . The score is compiled from three criteria, and patients are classified as AGO score positive or negative. A positive AGO score consists of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, ascites ≤ 500 ml, and patientʼs condition following complete resection after the first operation. The rate of macroscopically complete resections was 76% in the prospective DESKTOP II study 10 and 89.3% in a further analysis by Harter et al. 11 . But even women with a negative AGO score can have a complete resection with a good clinical outcome if they are treated in a gynecological center. A retrospective, single-center analysis by Muallem et al. 12 showed that of 127 women who had at least 1 negative AGO score criterion, it was still possible to achieve macroscopically complete resection in a second operation in 48.5% of them. Progression-free survival (PFS) was 22 months for the AGO score-positive group compared to 21 months for the AGO score-negative group.

A number of other different meta-analyses and three randomized controlled prospective studies, including the DESKTOP III study, were carried out. A Cochrane analysis done in 2013 investigated cytoreductive surgery for epithelial ovarian cancer recurrence in nine non-randomized studies which included a total of 1194 women 13 and came to the conclusion that macroscopically complete resection is associated with better survival rates. However, there are some reservations about this conclusion, as randomized controlled studies are lacking and there is some bias when retrospective studies are evaluated.

Three large randomized controlled phase III trials were then launched to examine this issue further: the AGO DESKTOP III study 9 , the GOG 213 study 14 and the Dutch SOCceR study 15 . Unfortunately, the SOCceR study was discontinued because the recruitment rate in the Netherlands was too low 16 .

The data from the GOG 213 study 14 were presented at the 2018 ASCO. GOG 213 reported poorer results in terms of disease-free survival and overall survival (PFS and OS) rates for women who had secondary cytoreductive surgery to treat platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer recurrence followed by chemotherapy (n = 240) compared to women who had no surgery and only received platinum-based combination chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab (n = 245). However, no structured score was used in this study. The median progression-free survival rate was 18.2 months for the surgery arm and 16.5 months for the control arm. Median overall survival was 53.6 months in the surgery group vs. 65.7 months in the surgery-free control group (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.7 – 1.11) 14 .

Criticisms of the GOG 213 study were the long recruitment period, the high percentage of women from East Asia, and that 84% of women received bevacizumab as maintenance therapy compared to 20% in the DESKTOP III study.

The final overall survival results for the DESKTOP III study of the AGO were presented at the 2020 ASCO annual meeting. Women whose first recurrence occurred > 6 months after their last platinum-based therapy and who had a positive AGO score were included in the study. 407 patients were randomized, 201 of whom were not treated with surgery. 206 women were randomized to the surgery arm, 187 of whom were ultimately treated with surgery. Complete resection was achieved in 75% of patients. Analysis of the primary endpoints showed a median overall survival of 53.7 months with and 46.2 months without surgery (HR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.59 – 0.97, p = 0.03). The median progression-free survival was 18.4 and 14 months, respectively (HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.54 – 0.82, p < 0.001). Patients who underwent surgery and for whom macroscopically complete resection could not be achieved had a median survival of just 28.8 months. This study therefore confirms the findings of the DESKTOP series that the goal of recurrence surgery must be complete resection. If this can be achieved, then patients will have a significant and clinically highly relevant survival benefit.

Based on these recent results, surgery aiming at complete resection should become the new therapeutic standard in future when treating the first recurrence of ovarian cancer in patient subgroups with platinum-sensitive tumors and a positive AGO score (ECOG 0, ascites ≤ 500 ml, complete resection in the first operation).

Early (Formerly Platinum-resistant) Recurrent Ovarian Cancer (PR-ROC)

If patients with ovarian cancer recurrence during platinum-based therapy or < 6 months after concluding such therapy show disease progression, then they are generally no longer considered suitable for further platinum-based therapy (formerly classified as having platinum-resistant or refractory disease). These patients typically show poor response rates and shorter overall survival rates. It is difficult to identify those women who will have a clear benefit from palliative chemotherapy, as the “symptom benefit” study of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup showed: 20% of 570 patients with platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer (PR-ROC), who were previously classified as suitable for palliative chemotherapy, stopped participating in the study within 8 weeks because of disease progression, death, or the patientʼs own wish. The median PFS was 1.2 months and the median OS was 2.9 months 17 . Validated scores such as the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score 18 can be used to estimate survival prognosis, and patients and their families can be advised about the benefits of further therapy. The benefit of higher line (> 3rd line) therapy is particularly questionable in cases with recurrence 19 . On the other hand, palliative chemotherapy for PR-ROC offers the benefit of symptom control 20 . The most important goal of therapy should be maintaining patientsʼ quality of life.

Combination chemotherapies are not viable for patients with PR-ROC looking for further therapy. The use of monochemotherapies has proved to be more effective 21 . Non-platinum-based chemotherapies such as topotecan, gemcitabine, paclitaxel or PLD may be considered 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 . A number of studies have reported that pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) has a PFS of 2.1 – 3.7 months with a 10 – 20% objective response rate and a better safety profile and better efficacy compared to topotecan 25 . Retrospective studies have observed a better response in patients with BRCA mutation 27 .

Even if patients received paclitaxel as first-line therapy, a weekly paclitaxel regimen is still an option and the regimen has been shown to have an objective response rate of 20.9% 23 .

New data on patients with a moderate refractory response was recently presented at the ESMO 2020. The INOVATYON trial compared carboplatin/PLD with trabectedin/PLD in patients who developed recurrence 6 – 12 months after their last platinum-based therapy. No benefit was found for trabectedin/PLD, but the median overall survival time was similar (21.3 and 21.5 months, respectively), making trabectedin/PLD not the therapy of choice for this patient cohort but nevertheless an option for patients with platinum hypersensitivity 28 .

Bevacizumab is another option for patients with PR-ROC. Bevacizumab was evaluated in the AGO OVAR-2.15 study (AURELIA) in patients, only 7% of whom had previously received bevacizumab as first-line therapy. The patients were randomized to receive either bevacizumab or placebo combined with paclitaxel, PLD or topotecan 29 .

The median PFS was 3.4 months for chemotherapy alone vs. 6.7 months with bevacizumab-based therapy (p ≤ 0.001). The median OS was 13.3 vs. 14.6 months, with an HR of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.66 – 1.08, p < 0.174). The addition of bevacizumab thus significantly prolonged the PFS, although overall survival was not significantly longer. Bevacizumab has been approved for use in Europe and the USA for women who were not previously treated with bevacizumab.

Late (Formerly Platinum-sensitive) Recurrent Ovarian Cancer (PS-ROC)

Patients with recurrent ovarian cancer which developed after a treatment-free interval of > 6 months are usually considered suitable for repeat platinum-based chemotherapy.

The longer the platinum-free interval, the better the extent of response to secondary therapy 30 . Carboplatin/paclitaxel, carboplatin/gemcitabine and carboplatin/PLD are most common regimens used in clinical practice, as they have been shown to be superior to monotherapy with carboplatin. Of these combination therapies, carboplatin/PLD has the more favorable side-effects profile 2 , 5 .

One hypothesis proposed for the treatment of platinum-sensitive recurrence in patients who develop recurrence after 6 – 12 months is that the platinum-free interval could be prolonged with a non-platinum-based therapy, which could increase the patientʼs response to subsequent platinum-based therapy.

In the randomized phase III MITO 8 study 31 , women received platinum-based chemotherapy followed by non-platinum-based therapy (standard arm) or vice versa (experimental arm). In > 85% of cases, the non-platinum-based therapy consisted of PLD. There was no benefit with regard to overall survival and the median PFS was significantly shorter in the experimental arm (median 12.8 vs. 16.4 months; HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.04 – 1.92, p = 0.025). The authors therefore came to the conclusion that starting platinum-based therapy should not be delayed under any circumstances. The INOVATYON trial recently presented at the 2020 ESMO did not show a benefit for the platinum-free combination of trabectedin/PLD in terms of improving the efficacy of subsequent platinum-based combinations 32 .

Trabectedin and PLD were evaluated in the phase III OVA-301 trial 33 . Platinum-sensitive patients received trabectedin/PLD or PLD alone. The combination therapy had a significantly better overall survival rate. The median OS was 23.0 vs. 17.1 months (HR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.43 – 0.82, p = 0.015). This makes the combination of trabectedin/PLD currently the therapy of choice for patients who would potentially be platinum-sensitive but are not able to receive any more platinum.

Angiogenesis Inhibitors

The introduction of antiangiogenic agents for continuous maintenance therapy, i.e., the addition of anti-angiogenesis to CTX and more, has made a significant difference to systemic therapy for PS-ROC.

Angiogenesis is important for tumor cell growth, tumor cell survival, and metastasis. Inhibition of angiogenesis works synergistically with other therapies, for example, by binding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The most common undesirable side effects of angiogenesis inhibitors are hypertension, proteinuria, bleeding, thromboembolic events, poor wound healing, and gastrointestinal perforation.

Bevacizumab

Bevacizumab is an anti-VEGF antibody and its use in the first and second-line therapy of epithelial ovarian cancer is well established 34 , 35 .

The approval for bevacizumab in Europe is based on the randomized controlled phase III trial OCEANS 36 , which evaluated bevacizumab or placebo combined with carboplatin/gemcitabine. All of the patients were bevacizumab-naïve. The bevacizumab arm achieved a significantly better PFS (12.4 vs. 8.4 months, HR: 0.485, p < 0.001) without improving overall survival (33.6 vs. 32.9 months, HR: 0.65, p = 0.65) 36 .

It should be noted that > 30% of the placebo patients received bevacizumab as crossover at the time of progression and many of the patients had already received further therapy at the time when OS was evaluated, which may have affected OS rates.

The phase III GOG 213 study investigated carboplatin/paclitaxel ± bevacizumab to treat platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer and the benefit of recurrence surgery. The study showed a significantly longer PFS in the carboplatin/paclitaxel plus bevacizumab study arm (23.8 vs. 10.4 months, HR: 0.63, p < 0.0001). OS analysis found no difference between the study arms (42.2 vs. 37.1 months, HR: 0.89, p = 0.056). A sensitivity analysis corrected for the therapy-free interval showed a post hoc survival benefit for the bevacizumab group (HR: 0.82, p = 0.045) 37 .

But the currently preferred regimen (because it is superior to carboplatin/gemcitabine and does not lead to alopecia) is carboplatin/PLD. These combination chemotherapies plus bevacizumab were investigated in the AGO OVAR 2.21 study. It should be noted that even the subgroup of patients who had already received first-line therapy with bevacizumab benefited 34 . In the study, PLD/carboplatin plus bevacizumab was associated with a significantly longer median PFS (13.3 vs. 11.7 months, HR: 0.8, 95% CI: 0.68 – 0.96, p = 0.0128) and, for the first time, also a longer median OS (31.8 vs. 27.8; HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.67 – 0.98, p = 0.032) compared to carboplatin/gemcitabine plus bevacizumab 34 .

The MITO 16B-MANGO OV2 phase III trial 38 was carried out with ROC patients who had already received first-line therapy with bevacizumab to establish whether re-induction of bevacizumab in combination chemotherapy would be beneficial.

The initial results showed a significantly better median PFS (8.8 vs. 11.8 months, HR: 0.51, p < 0.0001) in the bevacizumab arm. The data on overall survival are not yet mature. Both the patients who developed recurrence during maintenance therapy with bevacizumab and those who developed recurrence after the end of the therapy benefited from the re-induction of bevacizumab.

Poly(Adenosine Diphosphate-Ribose) Polymerase (PARP) Inhibitors

PARP inhibitors (PARPi) are currently used in two different clinical scenarios, either as monotherapy in higher therapy lines to treat progressive disease or as maintenance therapy after the end of chemotherapy. According to the current recommendations of the ESMO-ESGO, for patients with ROC who respond to platinum-based therapy, the gold standard is PARPi maintenance therapy (olaparib, niraparib and rucaparib) ( Fig. 1 ), irrespective of the patientʼs BRCA or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status 5 . The use of antiangiogenic agents for continuous maintenance therapy (i.e., when maintenance therapy is already initiated during chemotherapy) is a further option for patients, who should receive platinum-based therapy for ROC if they did not already receive it as first-line therapy.

PARP inhibitors are primarily effective against cells with BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 deficiency.

About 15.5% of all epithelial ovarian cancers have germline BRCA 1 mutation, and 5.2% have BRCA 2 mutation 39 . Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) is assumed to be present in 50% of high-grade serous ovarian cancers 40 . Homologous recombination is the most important repair mechanism for double-strand DNA breaks. Using the homologous DNA as a basis, the repair restores the original DNA sequence. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, as well as additional genes, play an important role in this process. Damage to the BRCA gene impairs this repair mechanism, and the cell has to resort to less effective and thus more error-prone repair pathways such as single-strand break repair or non-homologous recombination. Poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) plays an important role in these “alternative” repair processes, particularly for base excision repair in single-strand break repair. Understanding this led to the insight that disorders of DNA repair and particularly of homologous recombination contribute to the development of different tumors and conversely also offer therapeutic options 41 , 42 . Since the approval of olaparib combined with bevacizumab for patients who respond to platinum-based first-line therapy, determining the HRD of a tumor has become an integral part of the diagnostic workup of ovarian cancer.

In the AGO TR-1 study, a BRCA-like profile was even detected in 58.1% of tumor samples without a somatic or germline BRCA 1/2 mutation 43 . Patients with BRCA mutations are usually platinum-sensitive and have a longer overall survival 44 , 45 .

Nevertheless, it is still not clear which BRCA wild-type ovarian cancer is most likely to respond to PARP inhibition.

Olaparib

The PARPi olaparib was first approved for use in Europe as maintenance therapy for patients with ROC and BRCA 1 or 2 mutation who had shown a partial or complete response to platinum-based chemotherapy.

Study 19, the first randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase II trial, was carried out in patients with platinum-sensitive ROC to evaluate the benefit of maintenance therapy with olaparib 46 . The patients included in the study had to have shown partial or complete response to their last platinum-based chemotherapy. The study included patients with and patients without BRCA mutation. The study focused on tumors which had germline or somatic BRCA mutations. The median PFS was 3.6 months longer for the olaparib group than for the placebo group (8.4 vs. 4.8 months, HR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.25 – 0.49, p < 0.001). The overall survival rates showed a benefit for olaparib, but it did not reach the predefined threshold for statistical significance (median OS: 29.8 vs. 27.8 months, HR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.55 – 0.96, p = 0.025). This phase II trial was not sufficiently powered to show a significant difference in overall survival 46 .

Olaparib tablets (300 mg 2 × daily) were used instead of capsules for the first time in the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III AGO OVAR 2.23 (SOLO2) trial. Patients with ROC who had shown partial or complete response to the last of at least 2 platinum-based chemotherapies and who had a somatic or germline BRCA mutation were included in the study. The median PFS was significantly longer for the olaparib arm than for the placebo arm (19.1 vs. 5.5 months, HR: 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22 – 0.41, p < 0.0001) 47 .

Interestingly, patients who showed a response stayed on olaparib therapy for much longer 46 , 47 . This phenomenon has been noted for all PARP inhibitors, and no biological prognostic criteria have yet been found which would explain the long-term response. The final data of the SOLO2 study were presented at ASCO 2020. Median overall survival was 12.9 months longer with olaparib therapy. However, this improvement was not significant. This could be due to a crossover effect, as 38% of patients in the placebo arm later received PARPi therapy. A post hoc adjusted analysis of patients without crossover showed a significantly longer OS 48 .

The efficacy of monotherapies with PARPi was also first shown for olaparib. The phase II trial showed high response rates despite prior intensive therapy in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer 49 . These data led to the FDA approval of olaparib monotherapy for 4th line and higher therapies.

A current phase III trial (SOLO3) is also investigating the efficacy of olaparib as a monotherapy for patients with germline BRCA mutations. Patients with platinum-sensitive ROC who received at least 2 platinum-based therapies were compared with patients receiving non-platinum-based chemotherapy (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, or topotecan). Primary endpoint was the objective response rate, which was significantly higher in the olaparib group (72.2 vs. 51.4%, odds ratio: 2.53 [95% CI: 1.40 – 4.58], p = 0.002). The median PFS was 13.4 vs. 9.2 months in favor of the olaparib arm (HR: 0.62 [95% CI: 0.43 – 0.91], p = 0.013) 50 .

Niraparib

In contrast to other PARP inhibitors, cytochrome P450 enzymes and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) are inhibited by niraparib, which could lead to fewer drug interactions. In Europe, based on data from the phase III AGO OVAR 2.22 trial (NOVA) 51 , niraparib was approved for use in patients with ROC who showed partial or complete response to the last platinum-based therapy, irrespective of their BRCA or HRD status. Patients who received 300 mg/d niraparib had a longer progression-free survival compared to patients in the control arm, irrespective of whether they had a BRCA mutation or not, although the BRCA-mutated group had a longer PFS (BRCA-mutated: 21.0 vs. 5.5 months, HR: 0.27, 95% CI: 0.17 – 0.41; non-BRCA-mutated: 12.9 vs. 3.8 months, HR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.34 – 0.61, p < 0.001) 51 .

In the non-mutated patient cohort, an attempt was made, based on HRD status determined with Myriadʼs myChoice HRD ™ test, to identify a potential subgroup which would benefit from niraparib. It was found, however, that both patients with positive and patients with negative HRD test results benefited from using niraparib. An overall survival benefit has not yet been shown.

Going forward, monotherapy with niraparib was tested in the phase II QUADRA study. The study examined the efficacy of niraparib in platinum-sensitive women with BRCA-positive or HRD-positive tumors. All patients had had several previous therapies, with patients enrolled in the study having had a median of 4 previous therapies. 27.7% of patients (13 out of 47) achieved a tumor response according to RECIST (95% CI: 15.6–42.6; p = 0.00053) 52 . Based on these good response rates, niraparib was approved for use as a 4th line or higher therapy by the FDA in October 2019 to treat HRD-positive patients. This was defined based on BRCA mutation or genomic instability and disease progression > 6 months after the last platinum-based therapy. Myriadʼs myChoice HRD test was used in this study to determine homologous recombination deficiency.

Rucaparib

Rucaparib is another PARPi currently being investigated. It is approved for use in Europe for 2 indications: as a monotherapy for BRCA-mutated patients who have received two or more therapy lines and cannot tolerate further platinum-based therapy, and as maintenance therapy after platinum response, irrespective of the patientʼs BRCA or HRD status.

The ARIEL2 trial evaluated monotherapy with rucaparib. An overall response rate of 54% was achieved and a median response rate of 9.2 months. Patients were divided into 3 groups: a (germline or somatic) BRCA-positive group, a BRCA wild-type with high loss of heterozygosity (LOH) group, and a BRCA wild-type with low LOH group. The median progression-free survival was 12.8 months for BRCA-mutated patients, and 5.7 and 5.2 months, respectively, for the high LOH and low LOH groups 53 . A pooled analysis of the ARIEL2 trial and Study 10 showed high rates of response, particularly among patients with BRCA mutation and late recurrence, leading to the approval of rucaparib as a monotherapy as a 3rd line or higher therapy for the above-described group of patients with BRCA mutations 54 .

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled ARIEL3 study was carried out in patients with platinum-sensitive ROC, who had already received 2 platinum-based chemotherapies and showed partial or complete response to the last platinum-based chemotherapy. The patients received 600 mg 2 × daily rucaparib or placebo, stratified according to HRD status. Patients were divided into three cohorts: a (germline or somatic) BRCA-positive group, an HRD-positive group, and an intention-to-treat group (all patients).

The PFS of patients with BRCA mutation who received rucaparib was 16.6 months (95% CI: 13.4 – 22.9) compared to 6.4 months (95% CI: 3.4 – 6.7) for the placebo group (HR: 0.23, 95% CI: 0.16 – 0.34, p < 0.0001). The median PFS of patients who were HRD-positive was 13.6 vs. 5.4 months (HR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.24 – 0.42, p < 0.0001). The PFS for the ITT cohort was 10.8 vs. 5.4 months (p < 0.0001) in the rucaparib group and the placebo group, respectively 55 . The ARIEL3 trial therefore confirmed the efficacy of rucaparib, irrespective of patientsʼ HRD or BRCA status.

Outlook for PARP Inhibition

There are currently no data from investigations into whether repeat PARP inhibition is beneficial if first-line treatment already consisted of PARP inhibition.

The AGO OVAR-2.31 (OReO) study is currently being carried out to investigate this issue. This study is a randomized controlled phase III trial which evaluates olaparib maintenance therapy vs. placebo in patients who have already received PARP inhibitors for maintenance therapy and show partial or complete response to their current platinum-based chemotherapy.

The search is on for further predictive markers for therapy response, for the reasons behind PARP inhibitor resistance, and for answers to the question whether the efficacy of PARP inhibitors could be enhanced, for example, by combining them with antiangiogenetic agents or immunotherapy.

Other Therapies for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapies with tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors (letrozole and anastrozole), leuprolide acetate or megestrol acetate are possible options for patients who are unable to tolerate further cytotoxic chemotherapy or who no longer respond to chemotherapy 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 .

MEK inhibitor (trametinib) for low-grade serous recurrent ovarian cancer

The MEK inhibitor trametinib is a highly selective inhibitor of MEK 1 and 2 kinase activity. MEK proteins are involved in the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. In melanoma, for example, this signaling pathway is often activated by mutated BRAF forms.

Trametinib was investigated for low-grade serous recurrent ovarian cancer. At the ESMO 2019, Gershenson et al. presented data from a phase II/III trial of 260 patients who received either trametinib or letrozole/tamoxifen. The median progression-free survival was significantly longer in the trametinib group (median PFS: 13.0 vs. 7.2 months, HR: 0.48, 95% CI: 2.39 – 12.21, p < 0.0001). Overall survival was better with trametinib (37 months, 95% CI: 30.3–NR) compared with the control arm (29.2 months, CI: 23.5 – 51.6) 62 . It should be noted in this context, however, that while letrozole and tamoxifen showed some efficacy, they are not standard therapeutic drugs for low-grade serous recurrent ovarian cancer 63 .

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy was recently found not to offer any benefits to patients in terms of longer PFS and OS in a primary setting, based on the data of the IMagynp050/GOG 3015/ENGOT-OV39 phase III trial presented at the ESMO 2020 Virtual Congress 64 .

The role of immunotherapy in the recurrent setting has not yet been conclusively resolved.

The FDA has approved the use of pembrolizumab to treat solid tumors with high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) or DNA mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) which progress despite prior therapy and for which no further treatment options are available. Because of the tumor agnostic approval by the FDA, the anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab may also be a possible alternative to treat ROC 65 .

Pembrolizumab was investigated in 149 patients with 15 different types of cancer and MSI-H or dMMR solid tumors. 39.6% of patients showed complete or partial response. The length of response to therapy was 6 months or more in 78% of patients 66 .

Patients with ROC were not included in the five KEYNOTE studies.

Whether the FDA will extend its approval will depend on the findings of further studies.

The phase III JAVELIN 200 study investigated the use of avelumab in the treatment of ROC (n = 566). Patients received either avelumab monotherapy or avelumab combined with PLD vs. PLD alone in patients with PR-ROC. Avelumab monotherapy did not lead to any improvement in progression-free survival or overall survival, and the objective response rates were low (3.7% for avelumab monotherapy, 13.3% for avelumab + PLD and 4.2% for PLD). The study thus failed to meet its primary endpoints.

The PDL1-positive patients who had longer disease-free survival and overall survival rates were evaluated retrospectively.

More studies are required to determine the value of immunotherapy in the treatment of PR-ROC 67 , 68 . Numerous studies are currently underway, such as the AGO 2.29 study which is evaluating atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab and chemotherapy vs. bevacizumab and chemotherapy to treat recurrent ovarian cancer, and is studying the benefit and safety of immunotherapy to treat ovarian cancer in different therapy lines.

Conclusion

In summary, the treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer has changed considerably in recent years. Surgery to treat recurrence has become the new standard approach for patients with a positive AGO score, as it was found to result in a significant survival benefit. The addition of anti-VEGF and PARPi therapies could extend progression-free survival rates. There are currently no studies which have compared these new therapies with one another or determined the best sequence of these new therapies. New randomized controlled studies are required. At present, PARP inhibition is considered the gold standard, irrespective of the patientʼs BRCA or HRD status, after the patient has responded to platinum-based chemotherapy.

The outlook for future therapy options, even to treat platinum-resistant ROC, may consist of immunotherapy, possibly in combination with PARPi and anti-angiogenesis, as this would target both tumor cells and tumor stroma. The treatment of ovarian cancer will become increasingly individualized as it focuses on tumor biology (tumor agnostic approach) with the goal of improving patientsʼ overall survival.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt Carlota Claussen states that she has received speakerʼs fees from Roche and compensation for travel expenses from Astra Zeneca and Pfizer which were not connected to this published review. Lars Hanker states that he has received fees from Astra Zeneca, GSK/Tesaro, Clovis, Roche, Pfizer, Pharma Mar which were not connected to this published review./ Carlota Claussen gibt an, Vortragshonoraria von Roche und Reisekostenerstattungen von Astra Zeneca und Pfizer außerhalb dieser Reviewarbeit erhalten zu haben. Lars Hanker gibt an, Honoraria von Astra Zeneca, GSK/Tesaro, Clovis, Roche, Pfizer, Pharma Mar außerhalb dieser Reviewarbeit erhalten zu haben.

References/Literatur

- 1.Torre L A, Trabert B, DeSantis C E. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. doi:10.3322/caac.21456. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:284–296. doi: 10.3322/caac.21456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson M K, Pujade-Lauraine E, Aoki D. Fifth ovarian cancer consensus conference of the gynecologic cancer intergroup: Recurrent disease. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw663. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:727–732. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: A combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials. doi:10.1002/cncr.24149. Cancer. 2009;115:1234–1244. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmar M K, Ledermann J A, Colombo N. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13718-X. Lancet. 2003;361:2099–2106. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombo N, Sessa C, Du Bois A. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2019-000308. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:728–760. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGee J, Bookman M, Harter P. Fifth ovarian cancer consensus conference: Individualized therapy and patient factors. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx010. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:702–710. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo N, Sessa C, du Bois A. ESMO–ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2019-000308. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:728–760. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedlander M L. Do all patients with recurrent ovarian cancer need systemic therapy? doi:10.1002/cncr.32476. Cancer. 2019;125 (S24):4602–4608. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du Bois A, Sehouli J, Vergote I. Randomized phase III study to evaluate the impact of secondary cytoreductive surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: Final analysis of AGO DESKTOP III/ENGOT-ov20. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.6000 J Clin Oncol. 2020;38 (15_suppl)::6000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harter P, Sehouli J, Reuss A. Prospective validation study of a predictive score for operability of recurrent ovarian cancer: the Multicenter Intergroup Study DESKTOP II. A project of the AGO Kommission OVAR, AGO Study Group, NOGGO, AGO-Austria, and MITO. doi:10.1097/IGC.0b013e31820aaafd. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289–295. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31820aaafd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harter P, Beutel B, Alesina P F. Prognostic and predictive value of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) score in surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.027. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:537–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muallem M Z, Gasimli K, Richter R. AGO score as a predictor of surgical outcome at secondary cytoreduction in patients with ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:3423–3429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Rawahi T, Lopes A D, Bristow R E.Surgical cytoreduction for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer Cochrane Database Syst Rev 201302CD008765 10.1002/14651858.CD008765.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman R L, Spirtos N M, Enserro D. Secondary Surgical Cytoreduction for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1902626. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929–1939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van de Laar R, Zusterzeel P LM, Van Gorp T. Cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for recurrent platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian cancer (SOCceR trial): a multicenter randomised controlled study. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-22. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Laar R, Kruitwagen R FPM, Zusterzeel P LM. Correspondence: Premature Stop of the SOCceR Trial, a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial on Secondary Cytoreductive Surgery: Netherlands Trial Register Number: NTR3337. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000841. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:2. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grunewald T, Tang M, Chen J. Where have we gone wrong? Phase II trials (Ph2 t) do not inform the results of phase III trials (Ph3 t) in platinum resistant ovarian cancer (PROC) doi:10.1200/jco.2016.34.15_suppl.5559 J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 (15_suppl):5559. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roncolato F T, Berton-Rigaud D, OʼConnell R. Validation of the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) in recurrent ovarian cancer (ROC) – Analysis of patients enrolled in the GCIG Symptom Benefit Study (SBS) doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.10.019. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanker L C, Loibl S, Burchardi N. The impact of second to sixth line therapy on survival of relapsed ovarian cancer after primary taxane/platinum-based therapy. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds203. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2605–2612. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedlander M L, Stockler M, OʼConnell R. Symptom Burden and Outcomes of Patients With Platinum Resistant/Refractory Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Reality Check. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000147. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:857–864. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corrado G, Salutari V, Palluzzi E. Optimizing treatment in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. doi:10.1080/14737140.2017.1398088. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2017;17:1147–1158. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2017.1398088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutch D G, Orlando M, Goss T. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6735. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2811–2818. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markman M, Blessing J, Rubin S C. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) in platinum and paclitaxel-resistant ovarian and primary peritoneal cancers: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.036. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose P G, Blessing J A, Mayer A R. Prolonged oral etoposide as second-line therapy for platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. doi:10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.405. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:405–410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon A N, Fleagle J T, Guthrie D. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: A randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3312–3322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman R L, Brady W, McMeekin D S. A phase II evaluation of nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of recurrent or persistent platinum-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. doi:10.1200/jco.2010.28.15_suppl.5010. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 (15_suppl):5010. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safra T, Borgato L, Nicoletto M O. BRCA mutation status and determinant of outcome in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0272. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2000–2007. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colombo N, Gadducci A, Sehouli J. LBA30 INOVATYON study: Randomized phase III international study comparing trabectedin/PLD followed by platinum at progression vs. carboplatin/PLD in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer progressing within 6–12 months after last platinum line. Ann Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pujade-Lauraine E. Errata: Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial (J Clin Oncol 32: 1302–1308, 2014) doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0064. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4025. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenhauer E A, Vermorken J B, Van Glabbeke M. Predictors of response to subsequent chemotherapy in platinum pretreated ovarian cancer: A multivariate analysis of 704 patients. doi:10.1023/A:1008240421028. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:963–968. doi: 10.1023/a:1008240421028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pignata S, Scambia G, Bologna A. Randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of platinum-free interval prolongation in advanced ovarian cancer: The MITO-8,MaNGO, BGOG-Ov1, AGO-Ovar2.16, ENGOT-Ov1, GCIG study. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4293. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3347–3353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombo N, Gadducci A, Sehouli J. LBA30 INOVATYON study: Randomized phase III international study comparing trabectedin/PLD followed by platinum at progression vs carboplatin/PLD in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer progressing within 6–12 months after last platinum line. Ann Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poveda A, Vergote I, Tjulandin S. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in relapsed ovarian cancer: outcomes in the partially platinum-sensitive (platinum-free interval 6–12 months) subpopulation of OVA-301 phase III randomized trial. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq352. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:39–48. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfisterer J, Dean A P, Baumann K. Carboplatin/Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin/Bevacizumab (CD-BEV) Carboplatin/Gemcitabine/Bevacizumab (CG-BEV) in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29 (suppl_8):viii332–viii258. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burger R A, Brady M F, Bookman M A. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1104390. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghajanian C, Goff B, Nycum L R. Final overall survival and safety analysis of OCEANS, a phase 3 trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.08.004. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman R L, Enserro D, Spirtos N. A phase III randomized controlled trial of secondary surgical cytoreduction (SSC) followed by platinum-based combination chemotherapy (PBC), with or without bevacizumab (B) in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer (PSOC): A NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.5501 J Clin Oncol. 2018;36 (15_suppl):5501. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pignata S, Lorusso D, Joly F. Chemotherapy plus or minus bevacizumab for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients recurring after a bevacizumab containing first line treatment: The randomized phase 3 trial MITO16B-MaNGO OV2B-ENGOT OV17. doi:10.1200/jco.2018.36.15_suppl.5506 J Clin Oncol. 2018;36 (15_suppl):5506. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harter P, Hauke J, Heitz F. Prevalence of deleterious germline variants in risk genes including BRCA1/2 in consecutive ovarian cancer patients (AGO-TR-1) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186043. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell D, Berchuck A, Birrer M. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. doi:10.1038/nature10166. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Incorvaia L, Passiglia F, Rizzo S. “Back to a false normality”: New intriguing mechanisms of resistance to PARP inhibitors. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kristeleit R S, Miller R E, Kohn E C. Gynecologic Cancers: Emerging Novel Strategies for Targeting DNA Repair Deficiency. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. 2016 doi: 10.1200/edbk_159086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richters L K, Schouten P C, Kommoss S. BRCA-like classification in ovarian cancer: Results from the AGO-TR1-trial. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.5546 J Clin Oncol. 2017;35 (15_suppl):5546. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu K, Yang S, Zhao Y. Prognostic significance of BRCA mutations in ovarian cancer: An updated systematic review with meta-analysis. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.12306. Oncotarget. 2017;8:285–302. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konstantinopoulos P A, Spentzos D, Karlan B Y.Gene expression profile of BRCAness that correlates with responsiveness to chemotherapy and with outcome in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer J Clin Oncol 2010283555–3561.doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5719Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4868 Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ledermann J A, Pujade-Lauraine E. Olaparib as maintenance treatment for patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. doi:10.1177/1758835919849753. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1.758835919849753E15. doi: 10.1177/1758835919849753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann J A, Selle F. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poveda A, Floquet A, Ledermann J A. Final overall survival (OS) results from SOLO2/ENGOT-ov21: A phase III trial assessing maintenance olaparib in patients (pts) with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.6002 J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):6002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Domchek S M, Aghajanian C, Shapira-Frommer R. Efficacy and safety of olaparib monotherapy in germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with advanced ovarian cancer and three or more lines of prior therapy. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.020. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Penson R T, Villalobos Valencia R, Cibula D. Olaparib monotherapy versus (vs) chemotherapy for germline BRCA-mutated (gBRCAm) platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer (PSR OC) patients (pts): Phase III SOLO3 trial. doi:10.1200/jco.2019.37.15_suppl.5506 J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):5506. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mirza M R, Monk B J, Herrstedt J. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore K N, Secord A A, Geller M A. Niraparib monotherapy for late-line treatment of ovarian cancer (QUADRA): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30029-4. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:636–648. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swisher E M, Lin K K, Oza A M. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:75–87. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kristeleit R S, Shapira-Frommer R, Oaknin A. Clinical activity of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor rucaparib in patients (pts) with high-grade ovarian carcinoma (HGOC) and a BRCA mutation (BRCAmut): Analysis of pooled data from Study 10 (parts 1, 2a, and 3) and ARIEL2 (parts 1 and 2) doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw374.03 Ann Oncol. 2016;27:vi296. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coleman R L, Oza A M, Lorusso D. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. Lancet. 2017;390:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokoyama Y. Recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer and hormone therapy. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v1.i6.187. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:187. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i6.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Markman M, Iseminger K A, Hatch K D. Tamoxifen in Platinum-Refractory Ovarian Cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Ancillary Report. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0181. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:4–6. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao G G, Miller D S. Hormonal therapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. doi:10.1586/14737140.6.1.43. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:43–47. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papadimitriou C A, Markaki S, Siapkaras J. Hormonal Therapy with Letrozole for Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. doi:10.1159/000077436. Oncology. 2004;66:112–117. doi: 10.1159/000077436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Carmen M G, Fuller A F, Matulonis U. Phase II trial of anastrozole in women with asymptomatic müllerian cancer. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.021. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramirez P T, Schmeler K M, Milam M R. Efficacy of letrozole in the treatment of recurrent platinum- and taxane-resistant high-grade cancer of the ovary or peritoneum. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.014. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:56–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gershenson D M, Miller A, Brady W. A RANDOMIZED PHASE II/III STUDY TO ASSESS THE EFFICACY OF TRAMETINIB IN PATIENTS WITH RECURRENT OR PROGRESSIVE LOW-GRADE SEROUS OVARIAN OR PERITONEAL CANCER. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz394 Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl_5):v851–v934. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ricciardi E, Baert T, Ataseven B. Low-grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. doi:10.1055/a-0717-5411. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018;78:972–976. doi: 10.1055/a-0717-5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moore K N, Bookman M, Sehouli J. LBA31 Primary results from IMagyn050/GOG 3015/ENGOT-OV39, a double-blind placebo (pbo)-controlled randomised phase III trial of bevacizumab (bev)-containing therapy ± atezolizumab (atezo) for newly diagnosed stage III/IV ovarian cancer (OC) Ann Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Le D T, Durham J N, Smith K N. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. doi:10.1126/science.aan6733. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marcus L, Lemery S J, Keegan P. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Microsatellite Instability-High Solid Tumors. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4070. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3753–3758. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hartkopf A D, Müller V, Wöckel A. Translational Highlights in Breast and Ovarian Cancer 2019 – Immunotherapy, DNA Repair, PI3K Inhibition and CDK4/6 Therapy. doi:10.1055/a-1039-4458. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2019;79:1309–1319. doi: 10.1055/a-1039-4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pujade-Lauraine E, Fujiwara K, Ledermann J A. Avelumab alone or in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone in platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer: Primary and biomarker analysis of the phase III JAVELIN Ovarian 200 trial. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.04.053 Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:21–22. [Google Scholar]