Abstract

Motor inhibition enables rapid action stopping, even post initiation. When action stopping is anticipated (such as in laboratory stopping tasks), inhibition is engaged proactively. Such proactive inhibition changes the physiological implementation of action stopping. However, many real-world action-stopping scenarios involve little proactive inhibition. To investigate purely reactive inhibition, researchers need a different paradigm: studying surprise.

Action Stopping Inside and Outside the Laboratory

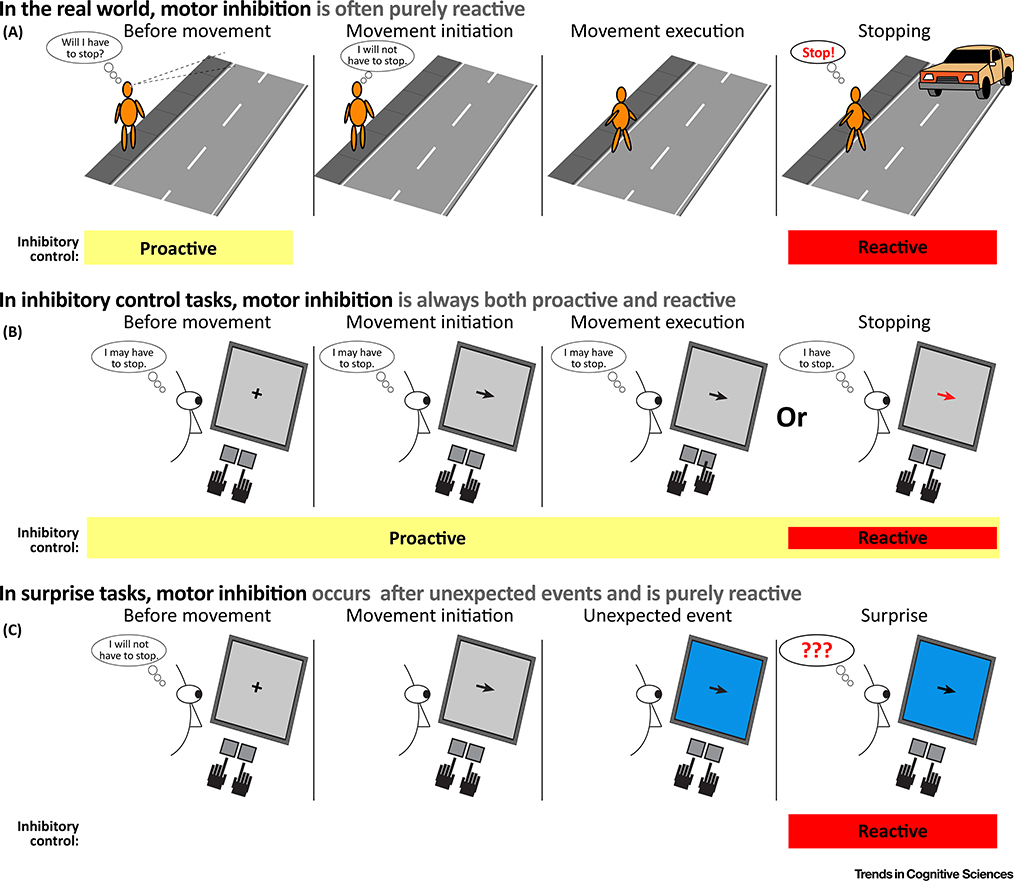

Motor inhibition (see Glossary) allows humans to rapidly stop actions even after their initiation. It enables flexible behavior in real-world situations both benign (stopping to walk out of an elevator when noticing a wrong floor number) and life threatening (stopping to step into the street when noticing an overlooked car; Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Surprise as a Model for Reactive Motor Inhibition in the Real World.

Real-world action stopping is often purely reactive (i.e., it involves no proactive inhibition). For example, when crossing a street (A), once we determine that stopping will not be necessary, we exert no proactive inhibition. Stopping situations then result from surprise, such as suddenly noticing a previously overlooked car. By contrast, laboratory stopping tasks (B) involve constant proactive inhibition, because participants steadily anticipate stopping. Following stop signals, inhibition is both proactive and reactive. In comparison, surprise tasks (C) simulate purely reactive inhibition by introducing unexpected events (e.g., a sudden unexpected visual stimulus), which automatically trigger reactive inhibition.

In the laboratory, action stopping is studied in explicit inhibitory control paradigms (EICPs), such as the stop-signal task. There, participants initiate responses to Go signals and withhold those responses when occasional Stop signals occur. Since EICPs include the explicit instruction that stop signals may occur at any time, participants anticipate having to stop throughout each movement (Figure 1B). Consequently, action stopping in EICP always results from both proactive and reactive motor inhibition [1]. Proactive motor inhibition denotes inhibitory effort exerted in anticipation of stopping (before stop signals), while reactive motor inhibition denotes inhibitory effort triggered by actual stop signals. Crucially, when present, proactive inhibition significantly alters the behavioral, physiological, and neural implementation of action stopping.

Therefore, I propose that EICP are imperfect models of real-world action stopping, which often involves little-to-no proactive inhibition. Instead, many real-world stopping scenarios result from surprise caused by unexpected events. In those situations, stopping has to be reactively implemented, without proactive control (Figure 1A).

Recent laboratory studies of surprise show that unexpected events automatically trigger such reactive motor inhibition, even when stopping is not anticipated. Therefore, surprise-based paradigms complement EICPs by providing a model of purely reactive inhibition.

Proactive Inhibition Changes Action Stopping

Past work shows that proactive inhibition changes the behavioral, physiological, and neural implementation of action stopping in EICP. This is crucial, since it shows that purely reactive inhibition is qualitatively different from situations that involve proactive inhibition.

Behaviorally, proactive inhibition (measured by anticipatory slowing of motor emission) reduces the demand on reactive inhibition, improving stop-signal reaction times [2].

Neurally, proactive and reactive inhibition involve different circuitry. Action stopping recruits a fronto-basal ganglia mechanism involving right inferior frontal cortex, the presupplementary motor area, and the subthalamic nucleus (STN). Within this network, the exact implementation of stopping purportedly depends on the type of inhibition that is deployed: while reactive inhibition recruits a ‘hyperdirect’ pathway from neocortex to STN, proactive inhibition involves a slower, ‘indirect’ pathway via the striatum [3].

Physiologically, proactive inhibition significantly alters the effects of stopping on the motor system. This is most evident from studies of corticospinal excitability (CSE). CSE can be measured by applying transcranial magnetic stimulation to representations of specific muscles in primary motor cortex (producing a deflection in the electromyogram, the motor evoked potential, which indexes CSE). Prominently, highly reactive stopping causes CSE suppression even in task-unrelated, resting muscles, illustrating the global, nonselective effects of reactive inhibition. However, the engagement of proactive control can completely attenuate this global inhibitory effect, allowing stopping to be selectively targeted at specific motor effectors [4,5].

Does Real-World Action Stopping Involve Proactive Inhibition?

Since all EICPs involve proactive motor inhibition, and since proactive inhibition alters action stopping, it bears asking how well these tasks emulate action stopping outside of the laboratory.

Motor inhibition in real-world stopping scenarios is best understood as a continuum between proactive and reactive inhibition. For example, navigating the same room will involve different amounts of proactive inhibition depending on familiarity, lighting, urgency, and so on. Importantly, however, this continuum includes many real-world stopping scenarios that involve no proactive inhibition at all (which is impossible to model in EICPs). Consider the examples from the introduction; walking into the street and exiting an elevator. In most (although not all) situations, we would not walk into a street in anticipation of having to stop, proactively moving at a slower pace. Instead, we monitor for potential stop signals before motor initiation and, once stopping is ruled out, walk at normal pace (i.e., without proactive inhibition; Figure 1A). The elevator example is similar: we rarely exit an elevator slowly and carefully, exerting proactive inhibition. Instead, once we suddenly realize that the doors opened on the wrong floor, stopping occurs rapidly and entirely reactively.

The absence of proactive motor inhibition in many real-world scenarios is directly related to the nature of stop signals in the real world. Many realistic stopping situations do not result from matching a specific stimulus to an explicit, actively maintained stop-signal template. Instead, they result from unexpected perceptual events. In the examples above, the overlooked car and the unexpected floor number constitute such events. There, action stopping results from stimulus-driven mismatches between the expected and actual physical environments, rather than from top-down detection of explicit stop signals under proactively exerted motor inhibition.

Hence, while EICPs provide unparalleled insights into action stopping that involves different (nonzero) amounts of proactive inhibition, a different model is needed to test the purely reactive control requirements of many real-world scenarios.

Surprise as a Model of Purely Reactive Inhibition

Laboratory studies of surprise offer a window into this type of purely reactive motor inhibition. This is supported by recent behavioral, physiological, and neural findings of reactive motor inhibition during surprise. Such studies all share the same simple experimental design principle: during a cognitive or motor task, unexpected perceptual events are presented to the subjects (Figure 1C). A classic example is the novelty-oddball task, in which subjects monitor a stream of frequent, standard tones for rare (but expected) oddball tones. Then, on a subset of trials, unexpected sounds are presented instead. Early landmark studies using this and similar tasks focused on cognitive aspects of surprise after such unexpected events (i.e., attentional capture [6,11]). In addition, however, several recent studies found that even though unexpected events in such studies do not convey an explicit instruction to stop, surprise is also accompanied by a prominent reactive inhibition of motor activity.

Behaviorally, pairing unexpected events with task stimuli in forced-choice reaction-time tasks causes reaction-time slowing [7], while pairing unexpected events with stop signals in EICP improves action stopping [8]. Moreover, such effects usually wear off as unexpected events are repeatedly presented, illustrating the role of surprise.

These changes in behavior are consistent with an engagement of motor inhibition during surprise, although they do not by themselves prove its presence. However, two recent studies clearly illustrate the motor aspects of surprise. First, unexpected events, even when presented outside of a cognitive task, induce a rapid, reflexive reduction of force exerted on a transducer held between two fingers [9]. Second, unexpected events also rapidly suppress corticospinal excitability, even below a resting baseline [7]. Importantly, this CSE suppression is observed at task-unrelated effectors, mirroring the nonselective physiological signature of largely reactive motor inhibition in EICPs (see above). Consequently, when unexpected events are paired with stop-signals in EICPs, the nonselective CSE suppression observed after stop signals is indeed amplified [10].

These physiological findings of reactive inhibition during surprise are further supported by neural measures. Depth-electrode recordings from human STN, a key node of the purported hyperdirect pathway underlying reactive inhibition, show increased local field potentials after unexpected events [11]. Additionally, optogenetics provide causal evidence for the involvement of the STN in reactive inhibition after unexpected events. In rodents, unexpected events interrupt ongoing licking bouts, mimicking the inhibitory motor effects of surprise in humans. When the STN is optogenetic ally inactivated, this effect disappears [12].

Together, these recent findings provide converging evidence for reactive motor inhibition after unexpected events. This suggests that the brain has evolved to process such events by reactively inhibiting ongoing motor activity, even when stopping is not anticipated or explicitly necessitated by the task [7,9,12]. Therefore, surprise is ideally suited to study the purely reactive motor inhibition found in many real-world scenarios.

Concluding Remarks

Studying surprise allows investigating reactive motor inhibition in the absence of proactive inhibition. Therefore, it provides a key addition to stopping research and complements classic EICP, which always involve some degree of proactive inhibition. Studying surprise can help investigate unique contributions of reactive and proactive inhibition to action stopping in the laboratory and simulate action stopping in everyday scenarios that do not involve proactive motor inhibition.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ian Greenhouse, Eliot Hazeltine, Cathleen Moore, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful remarks and discussions. J.R.W. received funding from the NIH (R01 NS102201), the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust, and the Aging Mind and Brain Initiative.

Glossary

- Corticospinal excitability (CSE)

the net excitability of corticomotor representations of specific muscles. Increases in CSE reflect readiness to respond, while reductions in CSE can reflect motor inhibition.

- Explicit inhibitory control paradigms (EICPs)

the most common behavioral paradigms used to investigate motor inhibition. Their defining feature is that participants are explicitly instructed to expect having to stop an action, usually following a salient signal.

- Hyperdirect pathway

one of the two major hypothesized fronto-basal ganglia neural pathways underlying motor inhibition. This pathway bypasses parts of the indirect pathway to more rapidly effect motor inhibition; it is hypothesized to exert global, nonselective motor inhibition.

- Indirect pathway

one of the two major hypothesized fronto-basal ganglia neural pathways underlying motor inhibition; purportedly enables proactive motor control by exerting selective inhibition.

- Motor inhibition

a cognitive control process that enables the stopping of actions even after they have already been initiated.

- Novelty-oddball task

a classic unexpected events task used to study the effects of surprise. A steady stream of standard stimuli is monitored for rare (but expected) ‘oddball’ stimuli, which are then sometimes unexpectedly replaced by ‘novel’, surprising stimuli.

- Proactive motor inhibition

inhibitory motor control that is implemented during the anticipation of potentially having to stop.

- Reactive motor inhibition

inhibitory motor control that is implemented during the actual action-stopping process.

- Stop-signal task

the most common EICP. Go signals prompt participants to initiate a movement. They are then sometimes followed by a delayed second signal, the stop signal, prompting a stop.

- Surprise

a cascade of cognitive, physiological, and motor reactions caused by unexpected events.

References

- 1.Chiew KS and Braver TS (2017) Context processing and cognitive control In The Wiley Handbook of Cognitive Control (Egner T, ed.), pp. 143–166, Wiley [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chikazoe J et al. (2009) Preparation to inhibit a response complements response inhibition during performance of a stop-signal task. J. Neurosci 29, 15870–15877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahanshahi M et al. (2015) A fronto-striato-subthalamic-pallidal network for goal-directed and habitual inhibition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16, 719–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duque J et al. (2017) Physiological markers of motor inhibition during human behavior. Trends Neurosci 40, 219–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenhouse I et al. (2012) Stopping a response has global or nonglobal effects on the motor system depending on preparation. J. Neurophysiol 107, 384–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horstmann G (2015) The surprise-attention link: a review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1339, 106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wessel JR and Aron AR (2013) Unexpected events induce motor slowing via a brain mechanism for action-stopping with global suppressive effects. J. Neurosci 33, 18481–18491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wessel JR (2017) Perceptual surprise aides inhibitory motor control. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform 43, 1585–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novembre G et al. (2018) Saliency detection as a reactive process: unexpected sensory events evoke corticomuscular coupling. J. Neurosci 38, 2385–2397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutra I et al. (2018) Perceptual surprise improves action stopping by nonselectively suppressing motor activity via a neural mechanism for motor inhibition. J. Neurosci 38, 1482–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wessel JR et al. (2016) Surprise disrupts cognition via a fronto-basal ganglia suppressive mechanism. Nat. Commun 7, 11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fife KH et al. (2017) Causal role for the subthalamic nucleus in interrupting behavior. eLife 6, e27689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]