Abstract

Objective: Insomnia is a major health challenge in the general population, but the results of the gender differences in the epidemiology of insomnia have been mixed. This is a meta-analysis to examine the gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia among the general population.

Methods:Two reviewers independently searched relevant publications in PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science from their inception to 16 April 2019. Studies that reported the gender-based prevalence of insomnia according to the international diagnostic criteria were included for analyses using the random-effects model.

Results:Eventually 13 articles were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of insomnia in the general population was 22.0% [n = 22,980, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17.0–28.0%], and females had a significantly higher prevalence of insomnia compared with males (OR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.35, 1.85, Z = 5.63, p < 0.0001). Subgroup analyses showed that greater gender difference was associated with the use of case-control study design and consecutive sampling method. Meta-regression analyses also revealed that higher proportion of females and better study quality were significantly associated with greater gender difference.

Conclusions:This meta-analysis found that the prevalence of insomnia in females was significantly higher than males in the included studies. Due to the negative effects of insomnia on health, regular screening, and effective interventions should be implemented in the general population particularly for females.

Keywords: insomnia, prevalence, gender difference, meta-analysis, observational studies

Introduction

As a major health challenge in the general population, the prevalence of insomnia has been rising over time globally (1). Insomnia is characterized by difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep (2, 3). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM−5), insomnia is defined by difficulty in falling asleep, staying asleep or early morning awakenings more than 3 times per week for more than 3 months, and is associated with subjective poor sleep quality, as well as daytime dysfunction (4). Several diagnostic criteria for insomnia have been widely used in clinical practice, including the International Classification of Sleep Disorder (ICSD), the DSM, and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) systems (e.g., codes 307.41, 307.42, or 780.52 in the ICD-9) (4–9). In addition, certain standardized diagnostic instruments for insomnia based on the ICD/DSM criteria have been developed, such as the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (10–13).

Due to its chronic nature, insomnia usually leads to many negative outcomes, such as impaired daily functioning, lower quality of life, and poor mental health (3, 14, 15). For instance, insomnia commonly occurs with psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety, and psychosis (16, 17). In order to reduce its adverse outcomes and allocate appropriate health resources, health professionals and policymakers need to understand the patterns and clinical features of insomnia. Prevalence of insomnia in the general population varies greatly across studies, ranging from 5.8 to 32.8% (18–21), and is associated with certain demographic factors, such as age, gender, marital status, income, and education level (22).

Gender differences in insomnia and related health issues have been widely examined (23–27). Such differences are not only associated with the etiological and pathophysiological processes, but also associated with the treatments and prognosis of insomnia (24). The results of gender differences in the prevalence studies of insomnia have been mixed. Some studies found that women suffered from insomnia more frequently than men (8, 18, 19), while opposite findings were found in other studies (28). A previous meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies (29) found that women had a higher risk of insomnia [risk ratio (RR) = 1.41]. However, RR was used as the effect size in this study, which is a major limitation. Odds ratio (OR) is mainly used for cross-sectional studies, while RR is used for cohort studies, both of which are comparable in magnitude only when the prevalence of the target disease is rare, such as cancer (30, 31). In addition, sophisticated analyses, such as subgroup and meta-regression analyses, were not performed, and publication bias and quality assessment were not tested. Furthermore, studies using both international diagnostic criteria and screening scales for insomnia were included, even though the prevalence of insomnia in studies based on diagnostic criteria was significantly lower than those using screening scales (32). Due to the abovementioned limitations of the previous meta-analysis and considering newly published studies on gender difference since then we conducted this meta-analysis to examine the gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia in the general population as defined by international diagnostic criteria.

Methods

Literature Search

This meta-analysis was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). A systematic search was independently performed by two reviewers (LNZ and QQZ) in the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science from their date of inception to 16 April 2019, using the following search terms: insomnia, sleepless, quality of sleep, dyssomnia, sleep complaint, sleep problem, sleep disturbance, sleep disorder, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM, International Classification of Sleep Disorder, ICSD, International Classification of Diseases, ICD, survey, cross-sectional, prevalence, and epidemiology.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies (only the baseline data were extracted in cohort studies) which fulfilled the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) stratified prevalence of insomnia by gender; (2) insomnia diagnosed by international diagnostic criteria, such as the DSM, ICSD, and ICD systems; (3) publications in English. Studies conducted in special groups, such as sleep medication users and militants, were excluded. The study selection and data extraction were independently performed by the same two reviewers (LNZ and QQZ). Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by involving a third reviewer (YTX). The titles and abstracts were first reviewed by the two reviewers independently, and then the full text of potentially relevant articles were examined for eligibility (33). If more than one article were published based on the same dataset, only the article with the largest simple size was included. Information of study characteristics (i.e., the first author, publication year, year of survey, country, continent, study design, sample size, response rate, and sampling method), population characteristics (i.e., age, female proportion), insomnia measures (i.e., diagnostic and type of interview) and the prevalence of insomnia (i.e., prevalence and prevalence in male and female groups) were extracted for analyses.

Quality Evaluation

As recommended previously (34–36), the quality evaluation was assessed by two reviewers (LNZ and QQZ) using an instrument with 6 items on the methodological quality of observational studies including sampling method, response rate, the representativeness and definition of targeted population, definition of insomnia, and validation of assessment instrument of insomnia.

Statistical Analyses

Stata version 12.0 and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis statistical software Version 2.0 were used to pool data using the random effects model (37). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using I2 statistic (I2 > 50% considered substantial heterogeneity) (38). The funnel plot and Egger's-test were used to test publication bias (39). Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding each study individually. All the statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05 (two-sided).

Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were carried out to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. The following categorical variables were explored: (1) year of survey: 1990–2004 vs. 2007–2012, using median splitting method; (2) study design: case-control vs. cohort vs. cross-sectional; (3) sampling method: consecutive vs. multi-stage stratified vs. random sampling; (4) type of interview: face to face vs. telephone interview; (5) age: ≤ 44.7 vs. >44.7 years, using splitting method; (6) continent: Africa vs. Asia vs. Europe vs. North America. Meta-regression analyses were conducted to examine the moderating effects of the proportion of females and study quality on the results.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies and Quality Assessment

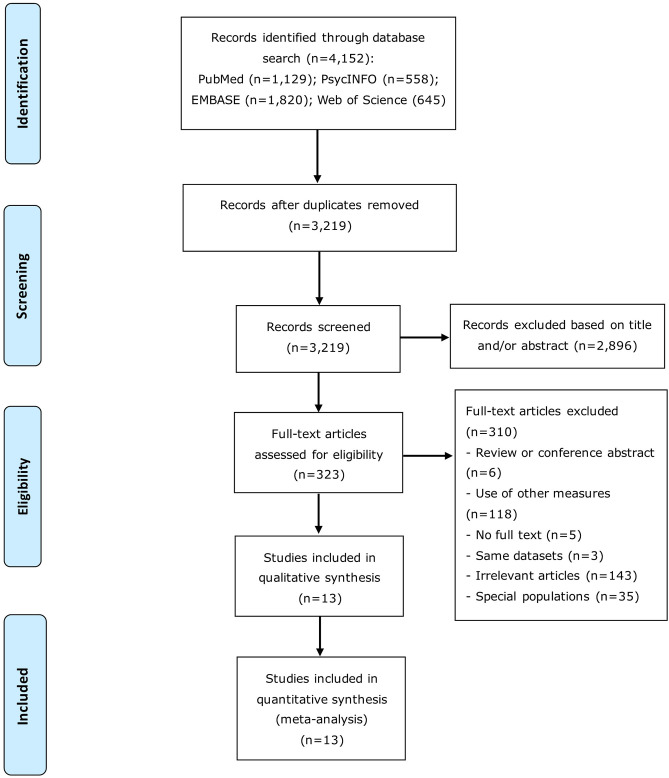

Initially, a total of 4,152 articles were identified. After screening titles or/and abstract, 323 articles were further reviewed and eventually 13 articles were included for analysis. The procedure of the literature search is presented in Figure 1. The 13 studies covered 326,908 participants in total (139,349 females and 187,559 males; Table 1). The studies were published between 1994 and 2017, and the sample size ranged from 290 to 299,188, with the response rate ranging from 33.4 to 97.5%.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| No. | First author (publication year) | References | Country | Continent | Year of survey | Study design | Sample size | Sampling method | Diagnostic classification | Age (mean) | Female proportion (%) | Type of interview | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kim (2017) | (19) | Korea | Asia | NR | Cross-sectional | 881 | Random | ICSD-2 | 70.6 | 59.0 | Face-to-face interview | 5 |

| 2 | Chiou (2016) | (18) | China (Taiwan) | Asia | 2002 | Cross-sectional | 4,047 | Cluster | DSM-IV | NR | 44.2 | Face-to-face interview | 4 |

| 3 | Barclay (2015) | (40) | US | North America | 1990 | Cohort | 2,822 | NR | DSM-III-R | NR | 54.0 | Semi-structured interview | 4 |

| 4 | Hysing (2013) | (20) | Norway | Europe | 2012 | Cross-sectional | 9,846 | NR | DSM-IV and DSM-V& | 17.0 | 53.0 | NR | 4 |

| 5 | López-Torres (2012) | (28) | Spain | Europe | 2009 | Cross-sectional | 926 | Random | DSM-IV-TR | 74.4 | 54.2 | Face-to-face interview | 5 |

| 6 | Morin (2011) | (21) | Canada | North America | 2007 | Cross-sectional | 2,000 | Random | DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 | 48.6 | 60.5 | Telephone interview | 5 |

| 7 | Kleinman (2009) | (41) | US | North America | 2007 | Case-control | 299,188 | NR | ICD-9 | 40.2 | 41.2 | NR | 3 |

| 8 | Gureje (2009) | (10) | Nigeria | Africa | 2004 | cohort | 2,152 | Multi-stage stratified | CIDI-3 | NR | 53.8 | Face-to-face interview | 5 |

| 9 | López-Torres (2007) | (42) | Spain | Europe | NR | Cross-sectional | 424 | NR | DSM-IV | NR | 58.3 | NR | 5 |

| 10 | Morin (2006) | (43) | Canada | North America | 2002 | Cross-sectional | 2,001 | Random | DSM-IV and ICD-10 | 44.7 | 58.0 | Telephone interview | 5 |

| 11 | Pallesen (2001) | (44) | Norway | Europe | NR | Cross-sectional | 2,001 | Random | DSM-IV | 44.7 | 54.5 | Telephone interview | 5 |

| 12 | Canals (1997) | (45) | Spain | Europe | NR | Cross-sectional | 290 | NR | DSM-III-R and ICD-10* | 18 | 52.4 | Face-to-face interview | 4 |

| 13 | Hohagen (1994) | (46) | Germany | Europe | NR | Cross-sectional | 330 | Consecutive | DSM-III-R | 74.0 | 72.0 | NR | 5 |

NR, Not reported; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ICSD, International Classification of Sleep Disorder; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Only insomnia diagnosed by DSM-IV was used for analyses.

The prevalence of insomnia diagnosed by DSM-III-R and ICD-10 was the same and the DSM-III-R was used for analyses.

The mean score of the study quality assessment was 4.54, ranging from 3 to 5. In all studies, insomnia was defined by validated instruments. The population sample of one study was not defined clearly; the samples of 6 studies were not recruited by random or consecutive sampling methods; the response rates of 10 studies were <70%; and the samples of 2 studies were not representative.

The Overall Prevalence of Insomnia and Gender Difference

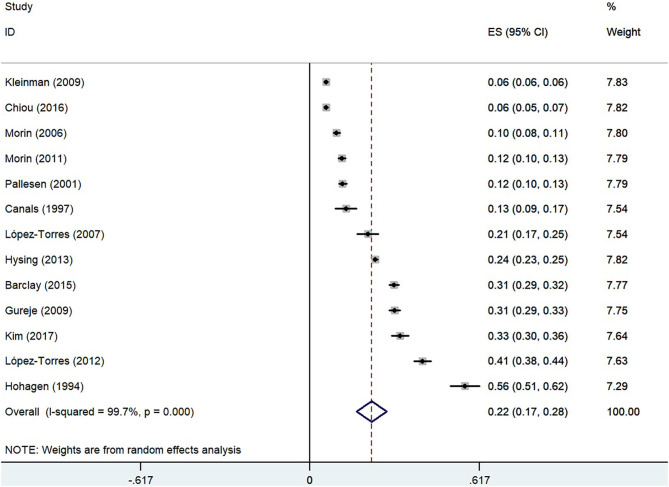

The pooled overall prevalence of insomnia using the random-effect model was 22.0% [n = 22,980, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17.0–28.0%, I2 = 99.7%], as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the prevalence of insomnia in the general population.

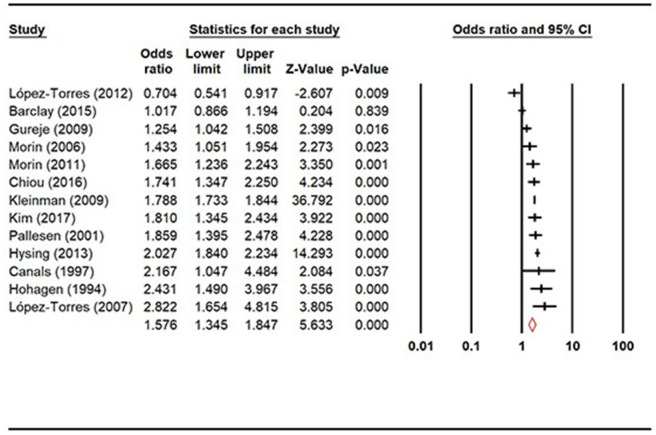

Prevalence of insomnia was compared between female and male populations (Figure 3), and the result showed that females had significantly higher prevalence of insomnia than males (OR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.35, 1.85, Z = 5.63, p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia.

Subgroup Analyses and Meta-Regression

Subgroup analyses (Table 2) revealed that greater gender difference was significantly associated with the use of case-control study design and consecutive sampling method. In contrast, the gender difference was not associated with year of survey, type of interview, age, or continent (all p-values > 0.05).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses between female and male groups.

| Subgroups | Categories (No. of studies) | Sample size | OR | 95% CI (%) | I2 (%) | P-value within subgroup | Q (P-value across subgroups) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Year of survey (years) | 1990–2004 (4) | 5,625 | 5,397 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.37 | 77.60 | 0.004 | 0.51 (0.48) |

| 2007–2012 (4) | 131,447 | 180,483 | 1.79 | 1.74 | 1.84 | 94.52 | <0.001 | ||

| Study design | Case-control (1) | 124,550 | 174,638 | 1.79 | 1.73 | 1.84 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 19.39 (<0.001) |

| Cohort (2) | 2,681 | 2,239 | 1.11 | 0.99 | 1.26 | 64.41 | 0.09 | ||

| Cross-sectional (10) | 12,118 | 10,628 | 1.79 | 1.67 | 1.93 | 85.34 | <0.001 | ||

| Sampling method | Consecutive (1) | 5,215 | 4,631 | 2.03 | 1.84 | 2.23 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 22.55 (<0.001) |

| Multi-stage stratified (2) | 2,313 | 1,840 | 1.30 | 1.11 | 1.52 | <0.001 | 0.47 | ||

| Random (6) | 127,171 | 176,444 | 1.77 | 1.72 | 1.82 | 89.90 | <0.001 | ||

| Type of interview | Face to face (5) | 129,520 | 179,464 | 1.73 | 1.68 | 1.78 | 95.67 | <0.001 | 3.39 (0.07) |

| Telephone (4) | 2,119 | 1,382 | 1.85 | 1.54 | 2.23 | <0.001 | 0.60 | ||

| Mean age (years) | ≤44.7 (5) | 132,164 | 181,162 | 1.86 | 1.80 | 1.91 | 95.01 | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.36) |

| >44.7 (4) | 2,469 | 1,668 | 1.31 | 1.12 | 1.53 | 91.30 | <0.001 | ||

| Continent | Africa (1) | 1,157 | 995 | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.51 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 7.14 (0.07) |

| Asia (2) | 2,308 | 2,620 | 1.77 | 1.46 | 2.15 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Europe (6) | 7,444 | 6,373 | 1.84 | 1.69 | 2.00 | 91.50 | <0.001 | ||

| North America (4) | 128,440 | 177,571 | 1.75 | 1.70 | 1.80 | 93.66 | <0.001 | ||

Q, Cochran's Q. Bold-value: p < 0.05.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In the meta-regression analyses, higher proportion of females (B = 0.02, Q = 31.59, p < 0.001) and better study quality (B = 0.27, Q = 18.46, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with greater gender difference.

Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

The visual Funnel plot (Supplementary Figure 1) and Egger's-test (t = 1.06, P = 0.31) did not reveal any publication bias. Sensitivity analyses did not find any individual study that changed the significance of the primary results when each study was sequentially excluded (Supplementary Figure 2).

Discussion

This was the first meta-analysis that specifically examined gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia as defined by international diagnosis criteria. The findings showed a significantly higher prevalence of insomnia in females (OR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.35, 1.85), which is higher than the effect size (RR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.28, 1.55, p < 0.001) of the previous meta-analysis (29). This meta-analysis also included recently published studies (8, 10, 18–21, 28, 40–46) and used international diagnostic criteria for insomnia. It should be noted that the previous meta-analysis (29) only included 2 studies using international diagnostic criteria and remaining studies using standardized scales or questions on insomnia, which could increase the heterogeneity caused by measurement instruments. Standardized scales and questions only measure the presence and severity of insomnia symptoms, but cannot establish the diagnosis of insomnia. In addition, RR was inappropriately used as the effect size in the previous meta-analysis (29), therefore the direct comparison between both meta-analyses should be made with caution.

The reasons for the higher prevalence of insomnia in females are multifactorial. Females are more vulnerable to negative socioeconomic factors, such as lower income or education level (47). In addition, females are more likely to experience certain physical problems compared to males, such as osteoporosis, fractures, and back problems (48). Furthermore, females have higher risk of developing certain psychiatric problems, such as depression and anxiety (49–51), all of which could increase the risk of insomnia in females.

Subgroup analyses found that greater gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia was associated with case-control study design and consecutive sampling method. Generally, studies using cohort study design and random sampling could generate better representativeness (52). In addition, a small number of included studies used case-control study design (n = 1) and consecutive sampling method (n = 1), therefore, their moderating effects on the results need to be further examined. Meta-regression analyses revealed that studies with higher proportion of females and better study quality were significantly associated with greater gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia, which may be due to insomnia being more accurately identified in higher quality studies (52). In addition, since females are more likely to have insomnia (24, 25), studies with higher proportion of females may show a greater gender difference.

The strengths of this meta-analysis are the inclusion of newly published studies and the use of international diagnostic criteria to accurately establish the diagnosis of insomnia. Several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, high heterogeneity was still present in subgroup analyses, because it is difficult to avoid in meta-analysis of observational studies (53). Second, some relevant factors associated with insomnia, such as insomnia type, duration of insomnia, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and marital status, were not reported in most studies, and so were not examined in the subgroup and meta-regression analyses. Finally, only studies conducted in the general population were included, therefore the findings cannot be generalized to special population groups.

In summary, this meta-analysis found that females had significantly higher prevalence of insomnia than males in the general population. Considering the increasing demands on health care services (54) and the negative health effects due to insomnia, preventive measures, regular screening, and effective interventions should be developed and implemented in the general population, especially for females.

Data Availability Statement

All the data that support the findings of this meta-analysis are available in Tables and Figures.

Author Contributions

L-NZ, L-GC, and Y-TX: study design and drafting of the manuscript. L-NZ, Q-QZ, YY, LZ, and Y-FX: data collection, analysis, and interpretation. CN: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors: approval of the final version for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drug (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005), and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577429/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Bajaj V, Kalra I, Bajaj A, Sharma D, Kumar R. A case of zolpidem dependence with extremely high daily doses. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2019) 11:e12356. 10.1111/appy.12356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sateia M, Doghramji K, Hauri P, Morin C. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. Sleep. (2000) 23:243–308. 10.1093/sleep/23.2.1l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benbir G, Demir AU, Aksu M, Ardic S, Firat H, Itil O, et al. Prevalence of insomnia and its clinical correlates in a general population in Turkey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2015) 69:543–52. 10.1111/pcn.12252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mai E, Buysse JD. Insomnia: prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Sleep Med Clin. (2008) 3:167–74. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders. Chest. (2014) 146:1387–94. 10.1378/chest.14-0970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zivetz L. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World Health Organization (1992) Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L-J, Steptoe A, Chen Y-H, Ku P-W, Lin C-H. Physical activity, smoking, and the incidence of clinically diagnosed insomnia. Sleep Med. (2017) 30:189–94. 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Online ICD9/ICD9CM codes. Free Online Searchable 2009 ICD-9-CM. (2009). Available online at: http://icd9.chrisendres.com/index.php?srchtype=diseases&srchtext=insomnia&Submit=Search&action=search (accessed 10 September, 2020).

- 10.Gureje O, Kola L, Ademola A, Olley OB. Profile, comorbidity and impact of insomnia in the Ibadan study of ageing. Intern J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2009) 24:686–93. 10.1002/gps.2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grau-Rivera O, Operto G, Falcón C, Sánchez-Benavides G, Cacciaglia R, Brugulat-Serrat A, et al. Association between insomnia and cognitive performance, gray matter volume, and white matter microstructure in cognitively unimpaired adults. Alzheimers Res Ther. (2020) 12:1–14. 10.1186/s13195-019-0547-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gureje O, Oladeji BD, Abiona T, Makanjuola V, Esan O. The natural history of insomnia in the Ibadan study of ageing. Sleep. (2011) 34:965–73. 10.5665/SLEEP.1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Üstün BT. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Intern J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2004) 13:93–121. 10.1002/mpr.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Liu Y, Lam SP, Li SX, Li AM, Wing YK. Relationship between insomnia and quality of life: mediating effects of psychological and somatic symptomatologies. Heart Mind. (2017) 1:50 10.4103/hm.hm_2_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao XL, Wang SB, Zhong BL, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. The prevalence of insomnia in the general population in China: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0170772 10.1371/journal.pone.0170772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emamian F, Khazaie H, Okun ML, Tahmasian M, Sepehry AA. Link between insomnia and perinatal depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. (2019) 28:e12858. 10.1111/jsr.12858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertenstein E, Feige B, Gmeiner T, Kienzler C, Spiegelhalder K, Johann A, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2019) 43:96–105. 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiou JH, Chen HC, Chen KH, Chou P. Correlates of self-report chronic insomnia disorders with 1–6 month and 6-month durations in home-dwelling urban older adults—the Shih-Pai Sleep Study in Taiwan: a cross-sectional community study. BMC Geriatr. (2016) 16:119. 10.1186/s12877-016-0290-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim KW, Kang SH, Yoon IY, Lee SD, Ju G, Han JW, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of insomnia and its subtypes in the Korean elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2017) 68:68–75. 10.1016/j.archger.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hysing M, Pallesen S, Stormark KM, Lundervold AJ, Sivertsen B. Sleep patterns and insomnia among adolescents: a population-based study. J Sleep Res. (2013) 22:549–56. 10.1111/jsr.12055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Belanger L, Ivers H, Merette C, Savard J. Prevalence of insomnia and its treatment in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. (2011) 56:540–8. 10.1177/070674371105600905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korkmaz Aslan G, IncI FH, Kartal A. The prevalence of insomnia and its risk factors among older adults in a city in Turkey's Aegean Region. Psychogeriatrics. (2020) 20:111–7. 10.1111/psyg.12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo RN, Yang C-C, Yen AM-F, Liu T-Y, Lin M-W, Chen SL-S. Gender difference in intraocular pressure and incidence of metabolic syndrome: a community-based cohort study in Matsu, Taiwan. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. (2019) 17:334–40. 10.1089/met.2018.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li R, Wing Y, Ho S, Fong S. Gender differences in insomnia—a study in the Hong Kong Chinese population. J Psychosom Res. (2002) 53:601–9. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00437-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshioka E, Saijo Y, Kita T, Satoh H, Kawaharada M, Fukui T, et al. Gender differences in insomnia and the role of paid work and family responsibilities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:651–62. 10.1007/s00127-011-0370-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Liao Y, Kelly BC, Xie L, Xiang Y-T, Qi C, et al. Gender and regional differences in sleep quality and insomnia: a general population-based study in Hunan Province of China. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:43690. 10.1038/srep43690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fausiah F, Turnip SS, Hauff E. Gender differences and the correlates of violent behaviors among high school students in a post-conflict area in Indonesia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2020) 12:e12383. 10.1111/appy.12383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Torres Hidalgo J, Navarro Bravo B, Párraga Martínez I, Andrés Pretel F, Téllez Lapeira J, Boix Gras C. Understanding insomnia in older adults. Intern J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2012) 27:1086–93. 10.1002/gps.2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang B, Wing YK. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. (2006) 29:85–93. 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Last A, Wilson S. Relative risks and odds ratios: what's the difference. Fam Pract. (2004) 53:108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viera J. Odds ratios and risk ratios: what's the difference and why does it matter? South Med J. (2008) 101:730–4. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817a7ee4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. (2002) 6:97–111. 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munawar K, Abdul Khaiyom JH, Bokharey IZ, Park MSA, Choudhry RF. A systematic review of mental health literacy in Pakistan. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2020) e12408. 10.1111/appy.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong M, Wang S-B, Li Y, Xu D-D, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of suicidal behaviors in patients with major depressive disorder in China: a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2018) 225:32–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. (2013) 47:391–400. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker G, Beresford B, Clarke S, Gridley K, Pitman R, Spiers G, et al. Technical Report for SCIE Research Review on the Prevalence and Incidence of Parental Mental Health Problems and the Detection, Screening and Reporting of Parental Mental Health Problems. Social Policy Research Unit; University of York (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman GD. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JP, Thompson GS. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barclay NL, Gehrman PR, Gregory AM, Eaves LJ, Silberg LJ. The heritability of insomnia progression during childhood/adolescence: results from a longitudinal twin study. Sleep. (2015) 38:109–118. 10.5665/sleep.4334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinman NL, Brook RA, Doan JF, Melkonian AK, Baran WR. Health benefit costs and absenteeism due to insomnia from the employer's perspective: a retrospective, case-control, database study. J Clin Psychiatry. (2009) 70:1098–104. 10.4088/JCP.08m04264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.López-Torres Hidalgo J, Gras CB, García YD, Lapeira JT, del Campo del Campo JM, Verdejo MÁL. Functional status in the elderly with insomnia. Qual Life Res. (2007) 16:279–86. 10.1007/s11136-006-9125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. (2006) 7:123–30. 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pallesen S, Nordhus IH, Nielsen GH, Havik OE, Kvale G, Johnsen BH, et al. Prevalence of insomnia in the adult Norwegian population. Sleep. (2001) 24:771–9. 10.1093/sleep/24.7.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canals J, Domènech E, Carbajo G, Bladé J. Prevalence of DSM-III-R and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders in a Spanish population of 18-year-olds. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (1997) 96:287–94. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hohagen F, Kappler C, Schramm E, Rink K, Weyerer S, Riemann D, et al. Prevalence of insomnia in elderly general practice attenders and the current treatment modalities. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (1994) 90:102–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lallukka T, Sares-Jäske L, Kronholm E, Sääksjärvi K, Lundqvist A, Partonen T, et al. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic differences in sleep duration and insomnia-related symptoms in Finnish adults. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:565. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murtagh KN, Hubert BH. Gender differences in physical disability among an elderly cohort. Am J Public Health. (2004) 94:1406–11. 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angst J, Gamma A, Gastpar M, Lépine J-P, Mendlewicz J, Tylee A. Gender differences in depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2002) 252:201–9. 10.1007/s00406-002-0381-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moieni M, Irwin MR, Jevtic I, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Eisenberger IN. Sex differences in depressive and socioemotional responses to an inflammatory challenge: implications for sex differences in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2015) 40:1709. 10.1038/npp.2015.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asher M, Aderka MI. Gender differences in social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. (2018) 74:1730–41. 10.1002/jclp.22624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng L-N, Yang Y, Feng Y, Cui X, Wang R, Hall BJ, et al. The prevalence of depression in menopausal women in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Affect Disord. (2019) 256:337–43. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2016) 316:2214–36. 10.1001/jama.2016.17324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sveticic J, Turner K, Bethi S, Krishnaiah R, Williams L, Almeida-Crasto A, et al. Short stay unit for patients in acute mental health crisis: a case-control study of readmission rates. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2020) 12:e12376. 10.1111/appy.12376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data that support the findings of this meta-analysis are available in Tables and Figures.