Abstract

Lysosomes are an integral part of the intracellular defense system against microbes. Lysosomal homeostasis in the host is adaptable and responds to conditions such as infection or nutritional deprivation. Pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and Salmonella avoid lysosomal targeting by actively manipulating the host vesicular trafficking and reside in a vacuole altered from the default lysosomal trafficking. In this review, the mechanisms by which the respective pathogen containing vacuoles (PCVs) intersect with lysosomal trafficking pathways and maintain their distinctness are discussed. Despite such active inhibition of lysosomal targeting, emerging literature shows that different pathogens or pathogen derived products exhibit a global influence on the host lysosomal system. Pathogen mediated lysosomal enrichment promotes the trafficking of a sub-set of pathogens to lysosomes, indicating heterogeneity in the host-pathogen encounter. This review integrates recent advancements on the global lysosomal alterations upon infections and the host protective role of the lysosomes against these pathogens. The review also briefly discusses the heterogeneity in the lysosomal targeting of these pathogens and the possible mechanisms and consequences.

Keywords: lysosomes, M. tuberculosis, Salmonella, heterogeneity, transcription factor EB, lysosomal homeostasis

Biology of Lysosome

Lysosomes are membrane-bound acidic, catabolic subcellular organelles present in eukaryotic cells. Lysosomes were first discovered by Christian René de Duve in 1955 (Appelmans et al., 1955; De Duve et al., 1955). Subsequent work from de Duve clarified that even though lysosomes are in a continuum with endocytic and biosynthetic pathways, they are distinct organelles (De Duve, 1963; Kornfeld and Mellman, 1989). Lysosomes are the terminal station for trafficking from degradative endocytosis, autophagy and phagocytosis, and consequently receive diverse cargo from these pathways. Lysosomes contain many types of hydrolytic enzymes including lipases, proteases, glycosidases, nucleases and sulfatases. These enzymes enable lysosomes to digest complex and diverse cargos (Luzio et al., 2017; Münz, 2017; Naslavsky and Caplan, 2018; Inpanathan and Botelho, 2019) into their constituent building blocks (Baggiolini, 1985; Kornfeld and Mellman, 1989; Casciola-Rosen and Hubbard, 1991; Rohrer and Kornfeld, 2001; Kolter and Sandhoff, 2005; Xu and Ren, 2015), which are released into the cytoplasm and recycled via the anabolic pathways of the cell (Luzio et al., 2017; Sabatini, 2017; Lawrence and Zoncu, 2019). Lysosomal acid hydrolases, which are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum, are tagged with mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) in the Golgi-network and then traffic to lysosomes via the endocytic system (Chao et al., 1990; Pohlmann et al., 1995; Saftig and Klumperman, 2009; Pohl and Hasilik, 2015; Luzio et al., 2017; Bhamidimarri et al., 2018). M6P receptor independent delivery of lysosomal proteins through sortilin and lysosomal integral membrane proteins (LIMPs) has also been reported (Glickman and Kornfeld, 1993; Storch and Braulke, 2005; Reczek et al., 2007; Braulke and Bonifacino, 2009; Saftig and Klumperman, 2009; Blanz et al., 2015; Markmann et al., 2015). Thus, the biogenesis of lysosomes requires the integration of endocytic and biosynthetic pathways (Kornfeld and Mellman, 1989; Saftig and Klumperman, 2009).

Lysosomal Adaptation and Biogenesis Upon Signals

Long considered as the “garbage bin” of the cell, the role of lysosomes has undergone tremendous revisions over the last few years. Lysosomes play an important role in maintaining homeostasis of several cellular processes including cellular clearance, metabolism, plasma membrane repair, pathogen defense, bone remodeling and act as signaling platform (Baron et al., 1985; Reddy et al., 2001; McNeil, 2002; Kurz et al., 2011; Settembre and Ballabio, 2011; Lacombe et al., 2013; Xu and Ren, 2015; Diez-Roux and Ballabio, 2016; Erkhembaatar et al., 2017; Palmieri et al., 2017; Thelen and Zoncu, 2017; Tsukuba et al., 2017; Corrotte and Castro-Gomes, 2019; Lawrence and Zoncu, 2019). An adaptive and dynamic lysosomal response upon ever-changing cellular environment is critical for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis, one such response being the biogenesis of lysosomes itself (Settembre et al., 2013; Inpanathan and Botelho, 2019). A major environmental trigger for lysosomal biogenesis is infections with intracellular pathogens such as M. tuberculosis and Salmonella ( Figure 1 ).

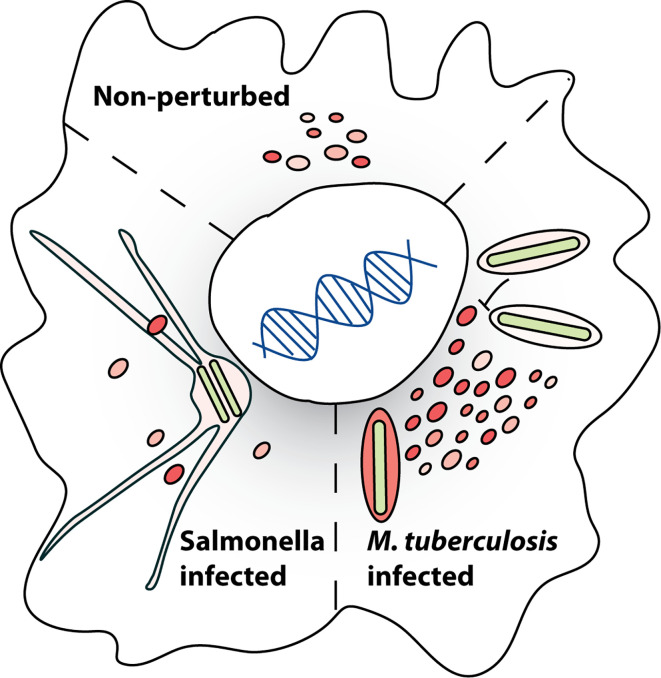

Figure 1.

Infection induced alterations in lysosomal homeostasis. Lysosomal homeostasis in a eukaryotic cell is altered by different pathogens. Examples of how the lysosomes are altered during infection with M. tuberculosis (Mtb) and Salmonella are shown, with Mtb infection inducing lysosomal biogenesis and Salmonella infection resulting in decreased lysosomal levels. Mechanisms and consequences of these modifications are discussed in the review. Lysosomal heterogeneity in a cell under non-perturbed conditions is depicted by the slightly different sizes and colors of the lysosomes.

Endo-lysosomal proteins such as Rab7 and Lamp proteins play crucial roles in maintenance of lysosomal homeostasis. Rab7 GTPase plays a key role in trafficking of lysosomal enzymes from endosomes to lysosomes, as expression of dominant negative Rab7 impairs lysosomal delivery of acid hydrolases (Press et al., 1998), acidification and ultimately degradation of cargo in lysosomes (Bucci et al., 2000; Guerra and Bucci, 2016). Similarly, trafficking of a subset of lysosomal enzymes and recycling of M6P receptors is altered upon Lamp2 deficiency (Eskelinen et al., 2002), showing its essential nature.

The mechanisms regulating cellular lysosomal biogenesis are becoming clear in the recent years. Transcription factor EB (TFEB), a basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription factor of the microphthalmia family, regulates transcription of the lysosomal genes and subsequently lysosomal biogenesis in cell. Multiple kinases including mTORC1, ERK2, AKT, GSKβ and PKCβ phosphorylate TFEB at different residues and regulate its subcellular localisation (Settembre et al., 2011; Parr et al., 2012; Ferron et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016; Palmieri et al., 2017; Puertollano et al., 2018). In nutrient rich conditions, activated mTORC1 on the lysosomal membrane phosphorylates TFEB at Ser142 and Ser211, which promotes the binding of TFEB with the 14-3-3 cytosolic chaperon and favors its cytoplasm retention. Conversely, mTORC1 inactivation upon starvation leads to nuclear translocation of TFEB ( Figure 2 ) (Settembre and Ballabio, 2011; Roczniak-Ferguson et al., 2012; Settembre et al., 2012; Puertollano et al., 2018). Dephosphorylation of TFEB by calcium-activated calcineurin and protein phosphatase 2A also induces nuclear translocation of TFEB (Medina et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Martina and Puertollano, 2018; Najibi et al., 2019). In the nucleus, TFEB binds to Coordinated Lysosomal Expression and Regulation (CLEAR) element in promoter region of the lysosomal genes and subsequently induces their transcription (Sardiello and Ballabio, 2009). Thus, signals from different cascades integrate at TFEB to regulate the lysosomal biogenesis and homeostasis in cells ( Figure 2 ). Emerging evidence indicate that infection by pathogens influence these lysosomal signaling pathways in the cells (Campbell et al., 2015; Najibi et al., 2019; Sachdeva et al., 2020a). In the following sections, we will explore the intracellular trafficking of two specific pathogens and their intersection with lysosomal pathways.

Figure 2.

Regulation of cellular lysosomal homeostasis by transcription factor EB (TFEB). In homeostatic conditions, late endosomes (LE) containing lysosomal associated membrane proteins (Lamps) and Rab7 fuse with lysosomes. Multiple kinases including mTORC1, AKT, ERK2, GSKβ phosphorylate TFEB, retaining it on the lysosomal surface or sequestered to 14-3-3 chaperons in the cytoplasm. In conditions of lysosomal induction such as starvation, mTORC1 is inactivated and ROS activated MCOLN1 channel releases Ca2+ from lysosomal lumen to cytoplasm. The release of lysosomal Ca2+ locally activates calcineurin, which dephosphorylates TFEB. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is another reported TFEB phosphatase. Dephosphorylated TFEB translocates to the nucleus where it induces transcription of genes containing CLEAR elements, that include several lysosomal genes, eventually resulting in enhanced lysosomal biogenesis.

Dynamics of PCV and Host Trafficking Alterations

In the host cell, several innate immune elements such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS, RNS), lysosomal acid hydrolases, xenophagy, inflammasome, septin caging, and proteasomal degradation are employed to neuter the pathogens (Radtke and O’Riordan, 2006; Deretic and Levine, 2009; Kaufmann and Dorhoi, 2016). But most pathogens manipulate these host mechanisms and generate an intracellular milieu conducive for their survival. One common strategy employed by many pathogens is to avoid trafficking to lysosomes (Méresse et al., 1999b; Duclos and Desjardins, 2000; Alix et al., 2011; Tang, 2015; Martinez et al., 2018). Several pathogens secrete effectors that target key host factors such as Rab GTPases (Deretic et al., 1997; Via et al., 1997; Fratti et al., 2001; Vergne et al., 2003b; Smith et al., 2007; Seto et al., 2011; Sherwood and Roy, 2013; Pradhan et al., 2018), cytoskeleton and motor protein (Dramsi and Cossart, 1998; Bearer and Satpute-Krishnan, 2002; Rottner et al., 2005; Henry et al., 2006b; Haglund and Welch, 2011; Shimono et al., 2016; Anes, 2017; Zhou et al., 2018) and block the fusion with lysosomes (Via et al., 1997; Russell, 2001; Pieters, 2008; Pradhan et al., 2018), instead residing in a modified phagosome, often called the pathogen containing vacuole (PCV) (Haas, 2007).

Mycobacteria and Salmonella are two well-studied pathogens that intersect with and manipulate the endo-lysosomal system of the host for their survival. Intracellular trafficking alteration of the PCV and escape from lysosomal delivery is well studied in both these pathogens (Méresse et al., 1999b; Duclos and Desjardins, 2000; Hashim et al., 2000; Gorvel and Méresse, 2001; Fratti et al., 2003; Vergne et al., 2003b; Chua et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2005; Deghmane et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2007; Alix et al., 2011; Vergne et al., 2014; Tang, 2015; Martinez et al., 2018). In this review, we will focus on the interaction of these pathogens with the functioning of the host lysosomes ( Figure 1 ). We will discuss the molecular mechanisms by which the two pathogens intersect with lysosomal trafficking to establish and sustain their respective PCV’s ( Figure 3 ). While these mechanisms are well known, and other reviews have documented them extensively (Russell, 2001; Holden, 2002; Pieters, 2008; Steele-Mortimer, 2008; Lahiri et al., 2010; Queval et al., 2017; Upadhyay et al., 2018) less is known about the impact of these infections on the lysosomal homeostasis of the infected cell. We will discuss emerging evidence from literature on the impact of these intracellular pathogens on the lysosomal system globally in the infected cells, beyond the confines of the PCV’s and explore their consequences ( Figure 4 ). Finally, we will briefly explore the emerging role of heterogeneity in shaping the outcomes of host-pathogen encounters, and examine the role of lysosomes in this context ( Figure 5 ).

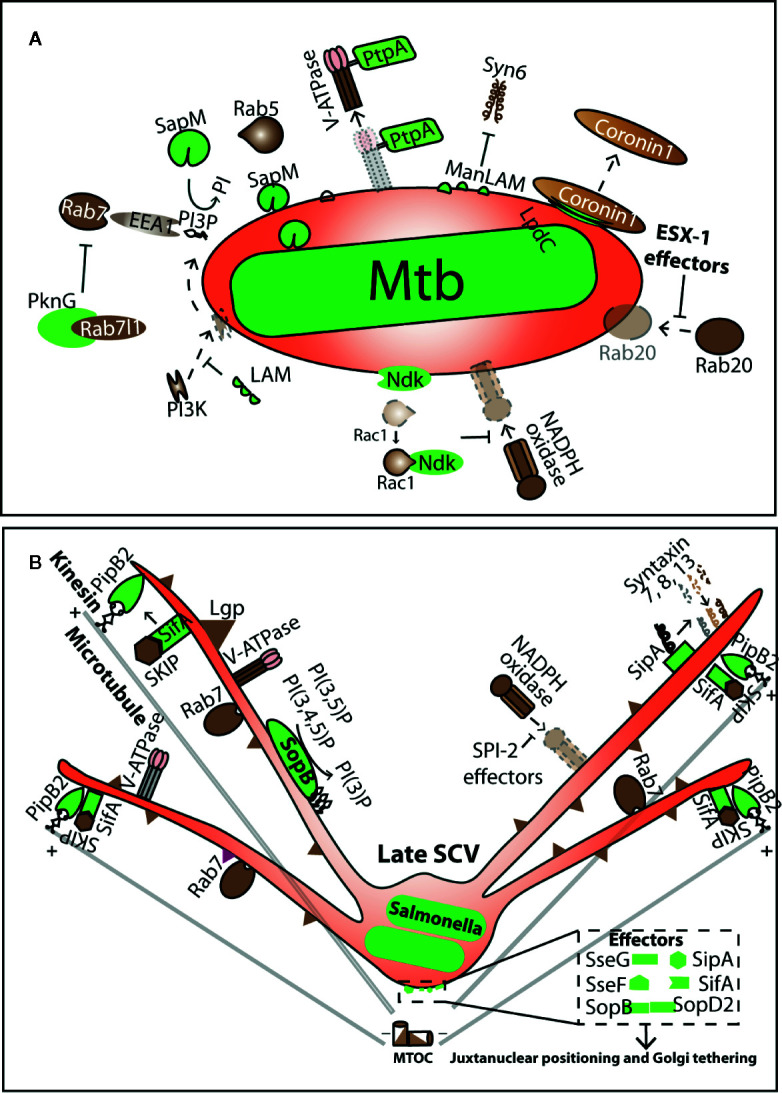

Figure 3.

Manipulation of lysosomal trafficking by Pathogen containing vacuoles. (A, B) summarizes some of the known molecular events in the interface of Mtb containing vacuole (MCV) and Salmonella containing vacuole (SCV), respectively. Pathogen effectors (shown in green) target different host factors (brown) and influence their recruitment or release on the respective PCV’s. Arrows indicate the nature of interactions. Dotted arrows show the processes that occur on a normal phagosome but are manipulated on the PCV.

Figure 4.

Alteration in the host lysosomal system upon intracellular infections. The host lysosomal alterations in four different pathogenic infections are shown. Lysosomes are shown in red. Mtb and Staphylococcus aureus infection increases the host cellular lysosomes levels compared to uninfected condition, whereas Salmonella infections leads to formation of late endosome/lysosome derived filamentous structures. In Trypanosoma infection, lysosomes move toward cell periphery at the site of pathogen entry and fuse with the plasma membrane to facilitate pathogen entry in the host cell. In these infectious condition, i.e Mtb, Salmonella, Staphylococcus and Trypanosoma, transcription factor EB (TFEB) is translocated to nucleus as compared to the uninfected state.

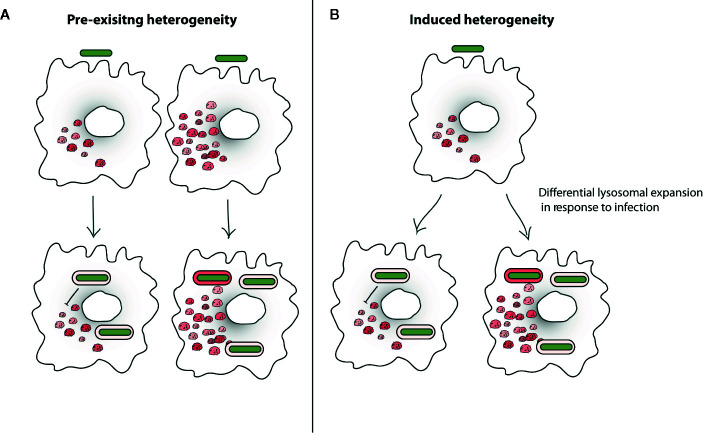

Figure 5.

Lysosomal heterogeneity influencing intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) trafficking. (A) Heterogeneity in lysosomal targeting of pathogens in the host cells could be driven by pre-existing heterogeneity of host cells where some cells intrinsically have more lysosomes and are more efficient in trafficking Mtb (green) to lysosomes (red), or it could also be driven by pathogen diversity, where some pathogens cells are less capable of resisting lysosomal delivery. (B) Other model proposes the idea of induced heterogeneity where post-infection the heterogeneity is induced in the host and pathogen e.g. lysosomal levels and lysosomal delivery of Mtb in cells becomes heterogeneous. Existing literature suggests that these events are not mutually exclusive and pre-existing heterogeneity in the pathogen cells can induce diversity in the host cell response. Similarly, heterogeneity of the host cells can generate diversity in the pathogens upon infection.

Mycobacteria Containing Vacuole Trafficking and Maturation

While inert particles such as beads undergo the process of phagosomal maturation and eventually fuse with the lysosomes, Mtb employs several virulence factors such as PknG, PtpA, SapM, LpdC, ManLAM, Ndk, ESAT6, CFP10 ( Figure 3A ) (Via et al., 1997; Fratti et al., 2001; Fratti et al., 2003; Vergne et al., 2003b; Chua et al., 2004; Vergne et al., 2004; Vergne et al., 2005; Deghmane et al., 2007; MacGurn and Cox, 2007; Bach et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2011; Simeone et al., 2012; Mehra et al., 2013; Shukla et al., 2014; Pradhan et al., 2018) that impede its vacuolar maturation and fusion with the lysosomes (Armstrong and Hart, 1971; Russell, 2001; Pieters, 2008; Cambier et al., 2014; Awuh and Flo, 2016). These effectors modulate several host factors such as PI3Kinase (Fratti et al., 2003; Vergne et al., 2003a; Chua and Deretic, 2004; Zulauf et al., 2018), V-ATPase (Bach et al., 2008), EEA1, Rab7, Lamp2 (Via et al., 1997; Fratti et al., 2001; Seto et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2015; Pradhan et al., 2018), coronin-1 (Ferrari et al., 1999; Deghmane et al., 2007; Jayachandran et al., 2007) and SNAREs (Fratti et al., 2002; Fratti et al., 2003; Vergne et al., 2004) on Mycobacteria containing vacuole (MCV) ( Figure 3A ) to arrest maturation of the vacuole ( Figure 2 ). Despite the arrested state, MCVs remain fusogenic to early and recycling endosomes, and in fact, show higher fusion with early endosomes (Vergne et al., 2004; Halaas et al., 2010). These reports convincingly show that Mtb extensively modulates its vacuole to attain effective maturation blockage ensuring that the majority of the bacteria do not fuse with lysosomes in cultured macrophages in vitro.

Salmonella Containing Vacuole Trafficking and Maturation

Salmonella is another fascinating pathogen whose intracellular lifestyle intersects extensively with the endo-lysosomal system of host cells. Salmonella can infect non-phagocytic cells by secreting effectors in the host (Brumell et al., 1999; Fu and Galán, 1999; Zhou et al., 1999; Galan and Zhou, 2000). In non-phagocytic cells, Salmonella containing vacuoles (SCVs) acquire early and late endosomal markers e.g. lysosomal membrane glycoproteins, V-ATPases and acquire NADPH oxidase (Vazquez-Torres et al., 2000; Gallois et al., 2001) but do not fuse with lysosomes (Garcia-del Portillo and Finlay, 1995; Méresse et al., 1999a; Uchiya et al., 1999; Duclos and Desjardins, 2000; Gorvel and Méresse, 2001) ( Figure 3B ). The limited lysosomal hydrolytic activity in SCV could also be because of the rapid dilution of these enzymes in larger area of SCV (Krieger et al., 2014; Liss and Hensel, 2015; Knuff and Finlay, 2017). Salmonella effectors such as PipB2, SifA, SipA, SopB, SopD2, SseJ, SseF, and SseG etc., target several host factors e.g. cytoskeleton, motor proteins, ESCRT machinery (Dukes et al., 2006), SNAREs (Singh et al., 2018), Rab GTPases (Smith et al., 2007) and phosphoinositide levels (Dukes et al., 2006) to maintain juxta-nuclear positioning and the integrity of the SCV (Beuzón et al., 2000; Salcedo and Holden, 2003; Guignot et al., 2004; Kuhle et al., 2004; Boucrot et al., 2005; Abrahams and Hensel, 2006; Abrahams et al., 2006; Henry et al., 2006a; Brawn et al., 2007; Ramsden et al., 2007; Steele-Mortimer, 2008; Wasylnka et al., 2008; Lau et al., 2019), Salmonella induced filaments (Sifs) formation (Stein et al., 1996; Waterman and Holden, 2003; Boucrot et al., 2005; Rajashekar et al., 2008; Szeto et al., 2009; Dumont et al., 2010; Leone and Méresse, 2011; Krieger et al., 2014; Rajashekar et al., 2014; Liss et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018) and to inhibit fusion with lysosomes (Garcia-del Portillo and Finlay, 1995; Méresse et al., 1999a; Uchiya et al., 1999; Duclos and Desjardins, 2000; Gorvel and Méresse, 2001) ( Figure 3B ). Interestingly, SCVs are differentially modulated in epithelial cells and macrophages indicating potential cell type specific mechanisms (Reuter et al., 2020).

Altogether, these studies demonstrate that Mtb and Salmonella containing vacuoles are substantially transformed compared to bead containing phagosomes and these alterations have an astounding influence on the intracellular trafficking of these vacuoles along the lysosomal pathway.

While phagosome maturation arrest mediated by Mtb is well-studied in cultured macrophages in vitro, emerging evidence suggest that under in vivo infections, Mycobacterium could encounter acidic conditions and indeed be delivered to and adapt to lysosomal conditions (Levitte et al., 2016; Sundaramurthy et al., 2017). Indeed Mtb infected cells and tissues show higher lysosomal content in vivo (Sundaramurthy et al., 2017; Sachdeva et al., 2020a), and Mtb are delivered rapidly to lysosomes in a susceptible mouse model (Sundaramurthy et al., 2017). Lysosomal delivery however does not result in the elimination of Mycobacteria, rather a reduced growth rate (Levitte et al., 2016; Sundaramurthy et al., 2017). Using elegant photobleaching experiments in zebrafish infected with M. marinum (Mm), Ramakrishnan group showed that the bacteria residing in lysosomes have slower growth compared to the ones that are not fused to lysosomes (Levitte et al., 2016). These studies suggest that additional facets of Mycobacterium interaction with the lysosomal trafficking system could be manifest during in vivo infection, which warrants further investigations.

Pathogens Affecting Host Lysosomal Homeostasis

While extensive work, as described above, has uncovered the mechanisms by which pathogens avoid lysosomal delivery, if and how these pathogens globally influence the host lysosomal homeostasis is not very-well understood. Documenting the global manipulations in the host cell by pathogens, beyond the confines of the PCV, is important to gain a complete appreciation of the influence of infection on the host, which further opens the possibilities to better design the counter-strategies against the pathogens. Recent work from several groups, including ours, have systematically addressed this question.

ESX-1 secretion system is known to play a role in impacting cellular lysosomes in different ways. Mtb and M. marinum (Mm) induces exocytosis of lysosomes upon infection in a ESX-1 dependent manner (Koo et al., 2008a). Esat-6, one of the well-studied substrates of the ESX-1 secretion system, has been recently shown to play a role in permeabilization of lysosomal membrane and release of mature cathepsin B into the cytosol, resulting in inflammasome activation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β (Amaral et al., 2018). Our recent work shows that Mtb infection alters the host lysosomal homeostasis and globally elevates the cellular lysosomal content of the infected macrophages under both in vitro and in vivo infections in mouse model. Mtb lipids, predominantly Sulfolipid-1, play a major role in lysosomal expansion. Correspondingly, a Sulfolipid-1 deficient Mtb mutant (MtbΔpks2) showed attenuated lysosomal rewiring. Sulfolipid-1 induces lysosomal biogenesis in macrophages in a mTORC1-TFEB dependent manner (Sachdeva et al., 2020a). Other bacterial components such as peptidoglycan from Staphylococcus aureus and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induce lysosomal expansion using TFEB dependent as well as independent pathways. However, the role of peptidoglycan and LPS on lysosomes in an infection context remains to be validated. These studies show that bacterial membrane components have an influence on the signaling pathways regulating lysosomal homeostasis of the host cells (Hipolito et al., 2019; Najibi et al., 2019; Sachdeva et al., 2020a), and exert an effect on lysosomes globally in the infected cell, beyond the confines of the PCV’s.

Salmonella infection depletes acidic and catalytically active lysosomes in the host cells (Eswarappa et al., 2010; McGourty et al., 2012; Najibi et al., 2019). Salmonella effector PipB2 instigate tubulations of late endosome (LE)/lysosomes to form Sifs. Ectopic expression of PipB2 induces the dispersal of LE/lysosomes toward the cell periphery by increasing their net anterograde movement (Knodler and Steele-Mortimer, 2005). In addition, ectopic expression of SifA, SpiC, and SopD2 in mammalian cells also induces aggregation of LE/lysosomes (Brumell et al., 2001b; Boucrot et al., 2003; Brumell et al., 2003; Shotland et al., 2003). Few other studies have also reported remodeling of the endosomal system in Salmonella infection and propose that it facilitates the nutrient acquisition for the bacteria (Rajashekar et al., 2008; Liss and Hensel, 2015). Furthermore, Salmonella-effector SifA makes a stable complex with the host SKIP and Rab9 in infected cells and subverts the retrograde trafficking of mannose-6-phosphate receptors (MPRs). Subsequently, subverted MPR trafficking leads to misrouting of the lysosomal enzymes in the cell, which ultimately abolishes lysosomal catalytic activity (McGourty et al., 2012). Ectopic expression of SifA is enough to alter MPR trafficking and lysosomal function in HeLa cells (McGourty et al., 2012).

Other than Mtb and Salmonella, few other pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Plasmodium and Trypanosoma alter lysosomal homeostasis in the host cells. Similar to Mtb, Staphylococcus aureus infection increases the levels of lysosomes in the host cells in a TFEB dependent manner (Visvikis et al., 2014; Najibi et al., 2016; Najibi et al., 2019). Infections by protozoan parasites such as Plasmodium and Trypanosoma alter lysosomal homeostasis by increasing lysosomes and inducing lysosomal exocytosis, which facilitates the entry of the pathogen in the host cells (Tardieux et al., 1992; Hissa et al., 2012; Vijayan et al., 2019). These reports suggest that different pathogens impose distinct alterations in the host lysosomal system beyond the confines of the pathogen containing vacuoles by influencing the signaling cascades regulating lysosomal homeostasis ( Figure 4 ). Some of the factors from individual pathogens modulating lysosomal processes is summarized in Table 1 , while much work remains to be done in this exciting and emerging area.

Table 1.

Different pathogen and their effectors affecting host lysosomal homeostasis.

| S. no | Pathogen | Effector | Effect on host lysosomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mtb, Mm | Esx-1 secretion system | Increases lysosomal exocytosis | (Koo et al., 2008b) |

| 2 | Mtb | ESAT-6 | Increased lysosomal permeabilization | (Amaral et al., 2018) |

| 3 | Mtb | Sulfolipid-1 | Increases lysosomal content of the host cell | (Sachdeva et al., 2020a) |

| 4 | Mtb | PIM6 | Increases lysosomal content of the host cell | (Sachdeva et al., 2020a) |

| 5 | Salmonella | SPI-2 T3SS effector | Depletes acidic lysosomes in the host cell | (Eswarappa et al., 2010; Najibi et al., 2019) |

| 6 | Salmonella | SifA | Impairs MPR dependent trafficking of lysosomal enzymes and thereby lysosome function | (McGourty et al., 2012) |

| 7 | Salmonella | PipB2 | Instigates tubulations of late endosome/lysosomes | (Knodler and Steele-Mortimer, 2005) |

| 8 | Salmonella | SifA, SpiC and SopD2 | Induce aggregation of late endosome/lysosomes | (Brumell et al., 2001a; Boucrot et al., 2003; Shotland et al., 2003) |

| 9 | Staphylococcus aureus | Peptidoglycan | Increases lysosomal content of the host cell | (Najibi et al., 2019) |

| 10 | Plasmodium yoelii | Secretory effector(s) | Lysosomal exocytosis | (Vijayan et al., 2019) |

| 11 | Trypanosoma cruzi (metacyclic) | gp82 protein | Lysosome biogenesis/scattering | (Cortez et al., 2016) |

Role of the Global Lysosomal Alterations in Pathogenesis Mechanisms

The lysosomal system is modulated in response to the physiological state of the cells and signal integration at the level of TFEB to regulate the lysosomal homeostasis in the cell. Gray et al reported that phagocytosis of Escherichia coli induces lysosomal biogenesis in cells in a TFEB dependent manner and this lysosomal enrichment enhances the bactericidal properties of the host cell (Gray et al., 2016). Our recent work with Mtb mediated lysosomal enrichment shows that the increased lysosomal levels in Mtb infected cells have a host-protective role against pathogenic Mtb (Sachdeva et al., 2020a). MtbΔpks2, the SL-1 mutant Mtb strain, shows attenuated lysosomal rewiring and corresponds to a phenotype of enhanced intracellular Mtb survival (Sachdeva et al., 2020a). Lysosomal proteins such as Lamp1 and 2 are necessary for phagosomal fusion with lysosomes (Huynh et al., 2007). Importantly, they are regulated by TFEB (Palmieri et al., 2011; Vural et al., 2018). Hence, it is suggested that TFEB mediated lysosomal enrichment enhances the fusion of bacterial vacuoles with lysosomes and augments the lysosomal targeting of pathogens in the host cell (Vural et al., 2018). Interestingly phagosome maturation rate is accelerated during SL-1 mediated lysosomal expansion (Sachdeva et al., 2020a), suggesting that enhanced lysosomal function influences phagosome maturation and subsequently bacterial survival. In line with this, chemical inhibition of lysosomal acidification with bafilomycin and cathepsin D using pepstatin in primary macrophages increased the intracellular growth of Mtb (Welin et al., 2011). Similarly, blocking lysosomal enzyme β-hexosaminidase enhanced the intracellular survival of M. marinum suggesting lysosomal hydrolases mediated restriction mechanisms (Koo et al., 2008b). Thus, lysosomal enrichment in macrophages promotes the lysosomal targeting of a proportion of Mtb and consequently limits the intracellular replication of Mtb (Vural et al., 2018; Sachdeva et al., 2020a). Further lysosomal enrichment by chemical treatment of autophagy modulators nortriptyline and prochlorperazine edisylate (Sundaramurthy et al., 2013) or gefitinib (Sogi et al., 2017) in macrophages increased lysosomal targeting of Mycobacteria and suppressed the intracellular bacterial replication. Treatment with Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), a cytokine of adaptive immunity, substantially decreases mycobacterial survival in the host (Flynn and Chan, 2001). Several findings suggest that the IFN-γ treatment substantially increases the anti-mycobacterial capacity of the host cells by enhancing lysosomal targeting of Mycobacteria (Schaible et al., 1998; Via et al., 1998). These studies suggest that pharmacologically increasing lysosomes influences the lysosomal delivery of Mtb and limits the growth of Mtb in cells, thus playing a protective role against Mtb. Thus either enrichment or depletion of lysosomal content has the respective opposite effect on intracellular Mtb survival, arguing for a reciprocal relationship between macrophage lysosomal content and intracellular Mtb survival.

The depletion of functional lysosomes upon Salmonella infection also facilitates the survival of the pathogen in the host (Eswarappa et al., 2010). Further, genetic or chemical modulation of the host lysosomes correspondingly affected the intracellular survival of Salmonella suggesting that the intracellular growth of Salmonella is affected by the lysosomes (McGourty et al., 2012). Several other studies have also reported that the chemical or genetic enrichment of lysosomes enhances bactericidal properties and bacterial clearance of other pathogens such as Burkholderia cenocepacia, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (Sogi et al., 2017; Vural et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019). These studies show an emerging consensus with these limited examples of the global content of lysosomes in cells having a growth inhibitory effect on intracellular pathogens.

While these studies show the relevance of global alteration of lysosomes to the infection, our recent study also throws light on lysosomal heterogeneity influencing intracellular Mtb trafficking in a non-perturbed macrophage population, i.e a higher proportion of Mtb are delivered to lysosomes in cells with higher lysosomal content (Sachdeva et al., 2020a; Sachdeva et al., 2020b).

Heterogeneity in Host-Pathogen Interaction

It is important to point out that lysosomal enrichment in cells, while restricting the intracellular growth of these pathogens, is not sufficient to completely eradicate the pathogen from the host cell. In fact, only a proportion of the intracellular Mtb population is targeted to lysosomes in response to the lysosomal enrichment in cells. Subcellular localization analysis in different studies shows that approximately 20-40% of Mtb are targeted to lysosomes (Welin et al., 2011; Sogi et al., 2017; Sachdeva et al., 2020a). When the lysosomal rewiring is attenuated, such as in MtbΔpks2 mutant, even less Mtb are delivered to lysosomes (Sachdeva et al., 2020a). It would be interesting to see if the physiological state of the bacteria such as redox potential, metabolic activity or antibiotic sensitivity of this subpopulation is different from the rest of the Mtb population that is not delivered to lysosomes.

Recent studies reveal substantial heterogeneity in the pathogen and host cells at single cell level that impacts the outcome of host-pathogen encounters (Avraham et al., 2015; Avraham and Hung, 2016). Heterogeneity could be either pre-existing or infection induced. Avraham et al. showed that varying PhoPQ activity on LPS modification in a subset of Salmonella generates a heterogeneous population of the pathogens (Avraham et al., 2015). This heterogeneous Salmonella population upon infection further drives variable type 1 IFN response in the host cells, thus promoting diversity in the host cells (Avraham et al., 2015). This study is an elegant example of pathogen heterogeneity shaping the outcome of infection. Recent work from our laboratory reveals pre-existing endocytic heterogeneity in the macrophages that determine their susceptibility to infections (Sachdeva et al., 2020b). The study shows considerably high intrinsic heterogeneity in the endocytic capacity of individual cells in a population, which governs the subsequent phagocytic events, including intracellular infections and subcellular trafficking within macrophages (Sachdeva et al., 2020b). Interestingly, the cells with higher endocytosis also have high levels of lysosomes suggesting a co-regulation of the endosomal and lysosomal numbers (Sachdeva et al., 2020b). In line with this, a recent study indicates the transcription regulation of endocytic genes such as Rab5A and Rab7A by TFEB, a known regulator of lysosomal biogenesis (Nnah et al., 2018). However, the exact mechanisms determining the spread and extent of endo-lysosomal heterogeneity in cells are not known, although it is quite likely that fluctuations in the expression and subcellular localization of TFEB could play a role. Importantly, Mtb trafficking to lysosomes is different in cells with different lysosomal content, i.e a higher proportion of Mtb are delivered to lysosomes in cells with higher lysosomal content, even in the same non-perturbed macrophage cell population (Sachdeva et al., 2020b), an effect that averages out at a population level. Thus, the lysosomal content in Mtb infected cells can be a combination of pre-existing heterogeneity (Sachdeva et al., 2020b) and infection induced lysosomal biogenesis (Sachdeva et al., 2020a) ( Figure 5 ). Importantly, differential subcellular trafficking of Mtb in these heterogeneous host cells could potentially generate diversity in the pathogen as well, since reports indicate that the physiological state of Mtb such as its redox potential is influenced depending on whether the bacterium is in lysosomes, or not (Bhaskar et al., 2014).

Similarly, a recent study shows another instance of pre-existing heterogeneity in the host primary human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC), where susceptibility to Listeria monocytogenes infection is determined at the level of bacterial adhesion to cells (Rengarajan and Theriot, 2020). These studies demonstrate that heterogeneity, whether pre-existing or generated upon infection has a substantial impact on the pathogen-host encounters at multiple levels including uptake, sub-cellular trafficking and downstream responses such as gene expression changes. Further work and development of novel pathogen reporter strains are required to delineate between infection induced vs pre-existing heterogeneity in different contexts and gain quantitative insights into the consequences of encountering heterogeneous sub-cellular environments for the bacteria.

Overall, the role of heterogeneity in host-pathogen interactions at a single cell level –host or pathogen mediated and pre-existing or infection induced – determining population outcomes is emerging as a major theme in infection biology. How the heterogeneity in lysosome function and importantly composition influences, and is influenced by, infection events will be exciting area to explore in the future.

Conclusion

In this review on intracellular pathogens and host lysosomal landscape, we show that pathogens such as Mtb and Salmonella impose global alteration on the host lysosomal system by manipulating the lysosomal signaling cascades in cells. These pathogens impose diverse kind of alterations in the host lysosomal landscape including enrichment, depletion and redistribution of the lysosomes. Importantly, lysosomes play a host protective role in the host-pathogen encounter and lysosomal enrichment in cells promotes delivery of pathogens such as Mtb and Salmonella to lysosomes, limiting the intracellular pathogen growth. Conversely, depletion of the host lysosomes promotes the intracellular survival of these pathogens. However, the lysosomal system does not completely eradicate pathogens such as Mtb and trafficking of only a subpopulation of these pathogens is influenced by the lysosomal system. In future, it will be important to understand the determinant(s) of the heterogeneous lysosomal targeting of these pathogen and its consequence for the bacteria. Such studies could lead to development of better host lysosomal targeted therapeutics against these dreaded infectious diseases.

Author Contributions

KS and VS conceived, wrote, and edited the review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

VS is supported by core funding from NCBS-TIFR.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Manisha Goel and Bishal Basak for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Abrahams G. L., Hensel M. (2006). Manipulating cellular transport and immune responses: dynamic interactions between intracellular Salmonella enterica and its host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 728–737. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams G. L., Müller P., Hensel M. (2006). Functional dissection of SseF, a type III effector protein involved in positioning the salmonella-containing vacuole. Traffic Cph. Den. 7, 950–965. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00454.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alix E., Mukherjee S., Roy C. R. (2011). Subversion of membrane transport pathways by vacuolar pathogens. J. Cell Biol. 195, 943–952. 10.1083/jcb.201105019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral E. P., Riteau N., Moayeri M., Maier N., Mayer-Barber K. D., Pereira R. M., et al. (2018). Lysosomal Cathepsin Release Is Required for NLRP3-Inflammasome Activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Infected Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 9, 1427. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anes E. (2017). Acting on Actin During Bacterial Infection. Cytoskelet. - Struct. Dyn. Funct. Dis. 13, 257–278. 10.5772/66861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appelmans F., Wattiaux R., De Duve C. (1955). Tissue fractionation studies. 5. The association of acid phosphatase with a special class of cytoplasmic granules in rat liver. Biochem. J. 59, 438–445. 10.1042/bj0590438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong J. A., Hart P. D. (1971). Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis with observations of fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J. Exp. Med. 134, 713–740. 10.1084/jem.134.3.713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham R., Hung D. T. (2016). A perspective on single cell behavior during infection. Gut Microbes 7, 518–525. 10.1080/19490976.2016.1239001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham R., Haseley N., Xavier R. J. J., Regev A., Hung D. T. T., Avraham R., et al. (2015). Pathogen Cell-to-Cell Variability Drives Heterogeneity in Host Immune Responses. Cell 162, 1309–1321. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awuh J. A., Flo T. H. (2016). Molecular basis of mycobacterial survival in macrophages. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 1625–1648. 10.1007/s00018-016-2422-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach H., Papavinasasundaram K. G., Wong D., Hmama Z., Av-Gay Y. (2008). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Virulence Is Mediated by PtpA Dephosphorylation of Human Vacuolar Protein Sorting 33B. Cell Host Microbe 3, 316–322. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M. (1985). “Lysosomal Hydrolases,” in The Reticuloendothelial System: A Comprehensive Treatise Volume 7B Physiology. Eds. Friedman H., Escobar M., Reichard S. M., Filkins J. P. (Boston, MA: Springer US; ), 67–93. 10.1007/978-1-4613-2353-2_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R., Neff L., Louvard D., Courtoy P. J. (1985). Cell-mediated extracellular acidification and bone resorption: evidence for a low pH in resorbing lacunae and localization of a 100-kD lysosomal membrane protein at the osteoclast ruffled border. J. Cell Biol. 101, 2210–2222. 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearer E. L., Satpute-Krishnan P. (2002). The Role of the Cytoskeleton in the Life Cycle of Viruses and Intracellular Bacteria: Tracks, Motors, and Polymerization Machines. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2, 247–264. 10.2174/1568005023342407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuzón C. R., Méresse S., Unsworth K. E., Ruíz-Albert J., Garvis S., Waterman S. R., et al. (2000). Salmonella maintains the integrity of its intracellular vacuole through the action of SifA. EMBO J. 19, 3235–3249. 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhamidimarri P. M., Krishnapati L. S., Ghaskadbi S., Nadimpalli S. K. (2018). Mannose 6-phosphate-dependent lysosomal enzyme targeting in hydra: a biochemical, immunological and structural elucidation. FEBS Lett. 592, 1366–1377. 10.1002/1873-3468.13030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar A., Chawla M., Mehta M., Parikh P., Chandra P., Bhave D., et al. (2014). Reengineering redox sensitive GFP to measure mycothiol redox potential of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during infection. PloS Pathog. 10, e1003902–e1003902. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanz J., Zunke F., Markmann S., Damme M., Braulke T., Saftig P., et al. (2015). Mannose 6-phosphate-independent Lysosomal Sorting of LIMP-2. Traffic Cph. Den. 16, 1127–1136. 10.1111/tra.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucrot E., Beuzón C. R., Holden D. W., Gorvel J.-P., Méresse S. (2003). Salmonella typhimurium SifA effector protein requires its membrane-anchoring C-terminal hexapeptide for its biological function. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14196–14202. 10.1074/jbc.M207901200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucrot E., Henry T., Borg J.-P., Gorvel J.-P., Méresse S. (2005). The intracellular fate of Salmonella depends on the recruitment of kinesin. Science 308, 1174–1178. 10.1126/science.1110225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braulke T., Bonifacino J. S. (2009). Sorting of lysosomal proteins. Biochim. Biophys . Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 1793, 605–614. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawn L. C., Hayward R. D., Koronakis V. (2007). Salmonella SPI1 Effector SipA Persists after Entry and Cooperates with a SPI2 Effector to Regulate Phagosome Maturation and Intracellular Replication. Cell Host Microbe 1, 63. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell J. H., Steele-Mortimer O., Finlay B. B. (1999). Bacterial invasion: Force feeding by Salmonella. Curr. Biol. CB 9, R277–R280. 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80178-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell J. H., Rosenberger C. M., Gotto G. T., Marcus S. L., Finlay B. B. (2001. a). SifA permits survival and replication of Salmonella typhimurium in murine macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 3, 75–84. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell J. H., Tang P., Mills S. D., Finlay B. B. (2001. b). Characterization of Salmonella-induced filaments (Sifs) reveals a delayed interaction between Salmonella-containing vacuoles and late endocytic compartments. Traffic Cph. Den. 2, 643–653. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell J. H., Kujat-Choy S., Brown N. F., Vallance B. A., Knodler L. A., Finlay B. B. (2003). SopD2 is a novel type III secreted effector of Salmonella typhimurium that targets late endocytic compartments upon delivery into host cells. Traffic Cph. Den. 4, 36–48. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.40106.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci C., Thomsen P., Nicoziani P., McCarthy J., van Deurs B. (2000). Rab7: A Key to Lysosome Biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 467–480. 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier C. J., Falkow S., Ramakrishnan L. (2014). Host evasion and exploitation schemes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 159, 1497–1509. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G. R., Rawat P., Bruckman R. S., Spector S. A. (2015). Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Nef Inhibits Autophagy through Transcription Factor EB Sequestration. PloS Pathog. 11, e1005018. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casciola-Rosen L. A., Hubbard A. L. (1991). Hydrolases in intracellular compartments of rat liver cells. Evidence for selective activation and/or delivery. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 4341–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao H. H., Waheed A., Pohlmann R., Hille A., von Figura K. (1990). Mannose 6-phosphate receptor dependent secretion of lysosomal enzymes. EMBO J. 9, 3507–3513. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07559.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua J., Deretic V. (2004). Mycobacterium tuberculosis reprograms waves of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate on phagosomal organelles. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36982–36992. 10.1074/jbc.M405082200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua J., Vergne I., Master S., Deretic V. (2004). A tale of two lipids: Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7, 71–77. 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrotte M., Castro-Gomes T. (2019). Lysosomes and plasma membrane repair. Curr. Top. Membr. 84, 1–16. 10.1016/bs.ctm.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez C., Real F., Yoshida N., Paulo F. D. S., Toledo R. P. D. (2016). Lysosome biogenesis / scattering increases host cell susceptibility to invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic forms and resistance to tissue culture trypomastigotes. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 748–760. 10.1111/cmi.12548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Duve C., Pressman B. C., Gianetto R., Wattiaux R., Appelmans F. (1955). Tissue fractionation studies. 6. Intracellular distribution patterns of enzymes in rat-liver tissue. Biochem. J. 60, 604–617. 10.1042/bj0600604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Duve C. (1963). The lysosome. Sci. Am. 208, 64–72. 10.1038/scientificamerican0563-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deghmane A.-E., Soualhine H., Soulhine H., Bach H., Sendide K., Itoh S., et al. (2007). Lipoamide dehydrogenase mediates retention of coronin-1 on BCG vacuoles, leading to arrest in phagosome maturation. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2796–2806. 10.1242/jcs.006221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V., Levine B. (2009). Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe 5, 527–549. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V., Via L. E., Fratti R. A., Deretic D. (1997). Mycobacterial phagosome maturation, rab proteins, and intracellular trafficking. Electrophoresis 18, 2542–2547. 10.1002/elps.1150181409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux G., Ballabio A. (2016). “TFEB, Master Regulator of Cellular Clearance,” in Lysosomes: Biology, Diseases, and Therapeutics (NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; ), 101–114. 10.1002/9781118978320.ch7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dramsi S., Cossart P. (1998). Intracellular Pathogens and the Actin Cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 137–166. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclos S., Desjardins M. (2000). Subversion of a young phagosome: the survival strategies of intracellular pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 2, 365–377. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes J. D., Lee H., hagen R., Barbara J R., Abigail N L., Eduoard E G., et al. (2006). The Secreted Salmonella Dublin Phosphoinositide Phosphatase, SopB, Localizes to PtdIns(3)P-containing Endosomes and Perturbs Normal Endosome to Lysosome Trafficking. Biochem. J. 395, 239–247. 10.1042/BJ20051451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont A., Boucrot E., Drevensek S., Daire V., Gorvel J.-P., Poüs C., et al. (2010). SKIP, the host target of the Salmonella virulence factor SifA, promotes kinesin-1-dependent vacuolar membrane exchanges. Traffic Cph. Den. 11, 899–911. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkhembaatar M., Gu D. R., Lee S. H., Yang Y.-M., Park S., Muallem S., et al. (2017). Lysosomal Ca2+ Signaling is Essential for Osteoclastogenesis and Bone Remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc Bone Miner. Res. 32, 385–396. 10.1002/jbmr.2986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen E.-L., Illert A. L., Tanaka Y., Schwarzmann G., Blanz J., von Figura K., et al. (2002). Role of LAMP-2 in Lysosome Biogenesis and Autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3355–3368. 10.1091/mbc.e02-02-0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarappa S. M., Negi V. D., Chakraborty S., Sagar B. K. C., Chakravortty D., Chandrasekhar Sagar B. K., et al. (2010). Division of the Salmonella-Containing Vacuole and Depletion of Acidic Lysosomes in Salmonella-Infected Host Cells Are Novel Strategies of Salmonella enterica To Avoid Lysosomes. Infect. Immun. 78, 68–79. 10.1128/IAI.00668-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G., Langen H., Naito M., Pieters J. (1999). A coat protein on phagosomes involved in the intracellular survival of mycobacteria. Cell 97, 435–447. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80754-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M., Settembre C., Shimazu J., Lacombe J., Kato S., Rawlings D. J., et al. (2013). A RANKL-PKCβ-TFEB signaling cascade is necessary for lysosomal biogenesis in osteoclasts. Genes Dev. 27, 955–969. 10.1101/gad.213827.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. L., Chan J. (2001). Immunology of Tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 93–129. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratti R. A., Backer J. M., Gruenberg J., Corvera S., Deretic V. (2001). Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rab5 effectors in phagosomal biogenesis and mycobacterial phagosome maturation arrest. J. Cell Biol. 154, 631–644. 10.1083/jcb.200106049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratti R. A., Chua J., Deretic V. (2002). Cellubrevin alterations and Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17320–17326. 10.1074/jbc.M200335200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratti R. A., Chua J., Vergne I., Deretic V. (2003). Mycobacterium tuberculosis glycosylated phosphatidylinositol causes phagosome maturation arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 5437–5442. 10.1073/pnas.0737613100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Galán J. E. (1999). A salmonella protein antagonizes Rac-1 and Cdc42 to mediate host-cell recovery after bacterial invasion. Nature 401, 293–297. 10.1038/45829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan J. E., Zhou D. (2000). Striking a balance: modulation of the actin cytoskeleton by Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 8754–8761. 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallois A., Klein J. R., Allen L. A., Jones B. D., Nauseef W. M. (2001). Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system mediates exclusion of NADPH oxidase assembly from the phagosomal membrane. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 166, 5741–5748. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Spahn C., Heilemann M., Kenney L. J. (2018). The Pearling Transition Provides Evidence of Force-Driven Endosomal Tubulation during Salmonella Infection. mBio 9, e01083-18. 10.1128/mBio.01083-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-del Portillo F., Finlay B. B. (1995). Targeting of Salmonella typhimurium to vesicles containing lysosomal membrane glycoproteins bypasses compartments with mannose 6-phosphate receptors. J. Cell Biol. 129, 81–97. 10.1083/jcb.129.1.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman J. N., Kornfeld S. (1993). Mannose 6-phosphate-independent targeting of lysosomal enzymes in I-cell disease B lymphoblasts. J. Cell Biol. 123, 99–108. 10.1083/jcb.123.1.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvel J.-P., Méresse S. (2001). Maturation steps of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Microbes Infect. 3, 1299–1303. 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01490-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. A., Choy C. H., Dayam R. M., Escobar E. O., Somerville A., Xiao X., et al. (2016). Phagocytosis enhances lysosomal and bactericidal properties by activating the transcription factor TFEB. Curr. Biol. CB 26, 1955–1964. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra F., Bucci C. (2016). Multiple Roles of the Small GTPase Rab7. Cells 5, 34. 10.3390/cells5030034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignot J., Caron E., Beuzón C., Bucci C., Kagan J., Roy C., et al. (2004). Microtubule motors control membrane dynamics of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1033–1045. 10.1242/jcs.00949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. (2007). The phagosome: compartment with a license to kill. Traffic Cph. Den. 8, 311–330. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund C. M., Welch M. D. (2011). Pathogens and polymers: Microbe–host interactions illuminate the cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 195, 7–17. 10.1083/jcb.201103148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaas Ø., Steigedal M., Haug M., Awuh J. A., Ryan L., Brech A., et al. (2010). Intracellular Mycobacterium avium Intersect Transferrin in the Rab11 + Recycling Endocytic Pathway and Avoid Lipocalin 2 Trafficking the Lysosomal Pathway. J. Infect. Dis. 201, 783–792. 10.1086/650493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashim S., Mukherjee K., Basu S. K., Chem J. B., Mukhopadhyay A. (2000). TRANSDUCTION: Live Salmonella Modulate Expression of Rab Proteins to Persist in a Specialized Compartment and Escape Transport to Lysosomes Live Salmonella Modulate Expression of Rab Proteins to Persist in a Specialized Compartment and Escape Transport t. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16281–16288. 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry T., Couillault C., Rockenfeller P., Boucrot E., Dumont A., Schroeder N., et al. (2006. a). The Salmonella effector protein PipB2 is a linker for kinesin-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 13497–13502. 10.1073/pnas.0605443103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry T., Gorvel J.-P., Méresse S. (2006. b). Molecular motors hijacking by intracellular pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 23–32. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipolito V. E. B., Diaz J. A., Tandoc K. V., Oertlin C., Ristau J., Chauhan N., et al. (2019). Enhanced translation expands the endo-lysosome size and promotes antigen presentation during phagocyte activation. PloS Biol. 17, e3000535. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hissa B., Duarte J. G., Kelles L. F., Santos F. P., del Puerto H. L., Gazzinelli-Guimarães P. H., et al. (2012). Membrane cholesterol regulates lysosome-plasma membrane fusion events and modulates Trypanosoma cruzi invasion of host cells. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1583. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden D. W. (2002). Trafficking of the Salmonella Vacuole in Macrophages. Traffic 3, 161–169. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Wu J., Wang W., Mu M., Zhao R., Xu X., et al. (2015). Autophagy regulation revealed by SapM-induced block of autophagosome-lysosome fusion via binding RAB7. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 461, 401–407. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh K. K., Eskelinen E.-L., Scott C. C., Malevanets A., Saftig P., Grinstein S. (2007). LAMP proteins are required for fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. EMBO J. 26, 313–324. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inpanathan S., Botelho R. J. (2019). The Lysosome Signaling Platform: Adapting With the Times. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 113. 10.3389/fcell.2019.00113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran R., Sundaramurthy V., Combaluzier B., Mueller P., Korf H., Huygen K., et al. (2007). Survival of Mycobacteria in Macrophages Is Mediated by Coronin 1-Dependent Activation of Calcineurin. Cell 130, 37–50. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H. E., Dorhoi A. (2016). Molecular Determinants in Phagocyte-Bacteria Interactions. Immunity 44, 476–491. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler L. A., Steele-Mortimer O. (2005). The Salmonella Effector PipB2 Affects Late Endosome/Lysosome Distribution to Mediate Sif Extension. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4108–4123. 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuff K., Finlay B. B. (2017). What the SIF Is Happening—The Role of Intracellular Salmonella-Induced Filaments. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 335. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolter T., Sandhoff K. (2005). PRINCIPLES OF LYSOSOMAL MEMBRANE DIGESTION: Stimulation of Sphingolipid Degradation by Sphingolipid Activator Proteins and Anionic Lysosomal Lipids. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 81–103. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.120013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo I. C., Ohol Y. M., Wu P., Morisaki J. H., Cox J. S., Brown E. J. (2008. a). Role for lysosomal enzyme beta-hexosaminidase in the control of mycobacteria infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 (2), 710–715. 10.1073/pnas.0708110105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo I. C., Wang C., Raghavan S., Morisaki J. H., Cox J. S., Brown E. J. (2008. b). ESX-1-dependent cytolysis in lysosome secretion and inflammasome activation during mycobacterial infection. Cell Microbiol. 10 (9), 1866–1878. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01177.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld S., Mellman I. (1989). The biogenesis of lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Cell Bioi. 5, 483–525. 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.002411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger V., Liebl D., Zhang Y., Rajashekar R., Chlanda P., Giesker K., et al. (2014). Reorganization of the Endosomal System in Salmonella-Infected Cells: The Ultrastructure of Salmonella-Induced Tubular Compartments. PloS Pathog. 10, e1004374. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhle V., Jäckel D., Hensel M. (2004). Effector proteins encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 interfere with the microtubule cytoskeleton after translocation into host cells. Traffic Cph. Den. 5, 356–370. 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz T., Eaton J. W., Brunk U. T. (2011). The role of lysosomes in iron metabolism and recycling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 1686–1697. 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe J., Karsenty G., Ferron M. (2013). Regulation of lysosome biogenesis and functions in osteoclasts. Cell Cycle 12, 2744–2752. 10.4161/cc.25825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri A., Eswarappa S. M., Das P., Chakravortty D. (2010). Altering the balance between pathogen containing vacuoles and lysosomes: a lesson from Salmonella. Virulence 1, 325–329. 10.4161/viru.1.4.12361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau N., Haeberle A. L., O’Keeffe B. J., Latomanski E. A., Celli J., Newton H. J., et al. (2019). SopF, a phosphoinositide binding effector, promotes the stability of the nascent Salmonella-containing vacuole. PloS Pathog. 15, e1007959. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R. E., Zoncu R. (2019). The lysosome as a cellular centre for signalling, metabolism and quality control. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 133–142. 10.1038/s41556-018-0244-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone P., Méresse S. (2011). Kinesin regulation by Salmonella. Virulence 2, 63–66. 10.4161/viru.2.1.14603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitte S., Adams K. N., Berg R. D., Cosma C. L., Urdahl K. B., Ramakrishnan L. (2016). Mycobacterial Acid Tolerance Enables Phagolysosomal Survival and Establishment of Tuberculous Infection In Vivo. Cell Host Microbe 20, 250–258. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Xu M., Ding X., Yan C., Song Z., Chen L., et al. (2016). Protein kinase C controls lysosome biogenesis independently of mTORC1 Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 1065–1077. 10.1038/ncb3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss V., Hensel M. (2015). Take the tube: Remodelling of the endosomal system by intracellular Salmonella enterica. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 639–647. 10.1111/cmi.12441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss V., Swart A. L., Kehl A., Hermanns N., Zhang Y., Chikkaballi D., et al. (2017). Salmonella enterica Remodels the Host Cell Endosomal System for Efficient Intravacuolar Nutrition. Cell Host Microbe 21, 390–402. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zhang N., Liu Y., Liu L., Zeng Q., Yin M., et al. (2019). MPB, a novel berberine derivative, enhances lysosomal and bactericidal properties via TGF-β-activated kinase 1-dependent activation of the transcription factor EB. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 33, 1468–1481. 10.1096/fj.201801198R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio J. P., Hackmann Y., Dieckmann N. M. G., Griffiths G. M. (2017). The Biogenesis of Lysosomes and Lysosome-Related Organelles. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6, 1–18. 10.1101/cshperspect.a016840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGurn J. A., Cox J. S. (2007). A genetic screen for Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants defective for phagosome maturation arrest identifies components of the ESX-1 secretion system. Infect. Immun. 75, 2668–2678. 10.1128/IAI.01872-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markmann S., Thelen M., Cornils K., Schweizer M., Brocke-Ahmadinejad N., Willnow T., et al. (2015). Lrp1/LDL Receptor Play Critical Roles in Mannose 6-Phosphate-Independent Lysosomal Enzyme Targeting. Traffic Cph. Den. 16, 743–759. 10.1111/tra.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina J. A., Puertollano R. (2018). Protein phosphatase 2A stimulates activation of TFEB and TFE3 transcription factors in response to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 12525–12534. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez E., Siadous F. A., Bonazzi M. (2018). Tiny architects: biogenesis of intracellular replicative niches by bacterial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42, 425–447. 10.1093/femsre/fuy013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGourty K., Thurston T. L., Matthews S., Pinaud L., Holden D. W. (2012). Salmonella inhibits retrograde trafficking of mannose-6-phosphate receptors and lysosome function. Science 338, 963–967. 10.1126/science.1227037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. (2002). Repairing a torn cell surface: make way, lysosomes to the rescue. J. Cell Sci. 115, 873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina D. L., Di Paola S., Peluso I., Armani A., De Stefani D., Venditti R., et al. (2015). Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 288–299. 10.1038/ncb3114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra A., Zahra A., Thompson V., Sirisaengtaksin N., Wells A., Porto M., et al. (2013). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Type VII Secreted Effector EsxH Targets Host ESCRT to Impair Trafficking. PloS Pathog. 9, e1003734. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méresse S., Steele-Mortimer O., Finlay B. B., Gorvel J. P. (1999. a). The rab7 GTPase controls the maturation of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles in HeLa cells. EMBO J. 18, 4394–4403. 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méresse S., Steele-Mortimer O., Moreno E., Desjardins M., Finlay B., Gorvel J.-P. (1999. b). Controlling the maturation of pathogen-containing vacuoles: a matter of life and death. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, E183–E188. 10.1038/15620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münz C. (2017). Autophagy Proteins in Phagocyte Endocytosis and Exocytosis. Front. Immunol. 8, 1183. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najibi M., Labed S. A., Visvikis O., Irazoqui J. E. (2016). An Evolutionarily Conserved PLC-PKD-TFEB Pathway for Host Defense. Cell Rep. 15, 1728–1742. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najibi M., Moreau J. A., Honwad H. H., Irazoqui J. E. (2019). A Novel PHOX/CD38/MCOLN1/TFEB Axis Important For Macrophage Activation During Bacterial Phagocytosis. bioRxiv 669325. 10.1101/669325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky N., Caplan S. (2018). The enigmatic endosome – sorting the ins and outs of endocytic trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 131, jcs216499. 10.1242/jcs.216499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnah I. C., Wang B., Saqcena C., Weber G. F., Bonder E. M., Bagley D., et al. (2018). TFEB-driven endocytosis coordinates MTORC1 signaling and autophagy. Autophagy 15, 151–164. 10.1080/15548627.2018.1511504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri M., Impey S., Kang H., di Ronza A., Pelz C., Sardiello M., et al. (2011). Characterization of the CLEAR network reveals an integrated control of cellular clearance pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3852–3866. 10.1093/hmg/ddr306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri M., Pal R., Nelvagal H. R., Lotfi P., Stinnett G. R., Seymour M. L., et al. (2017). mTORC1-independent TFEB activation via Akt inhibition promotes cellular clearance in neurodegenerative storage diseases. Nat. Commun. 8, 14338. 10.1038/ncomms14338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C., Carzaniga R., Gentleman S. M., Van Leuven F., Walter J., Sastre M. (2012). Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibition promotes lysosomal biogenesis and autophagic degradation of the amyloid-β precursor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 4410–4418. 10.1128/MCB.00930-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters J. (2008). Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the Macrophage: Maintaining a Balance. Cell Host Microbe 3, 399–407. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl S., Hasilik A. (2015). Chapter 4 – Biosynthesis, targeting, and processing of lysosomal proteins: Pulse–chase labeling and immune precipitation. Methods Cell Biol. 126, 63–83. 10.1016/bs.mcb.2014.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann R., Boeker M. W. C., Figura K. (1995). The Two Mannose 6-Phosphate Receptors Transport Distinct Complements of Lysosomal Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27311–27318. 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan G., Shrivastva R., Mukhopadhyay S. (2018). Mycobacterial PknG Targets the Rab7l1 Signaling Pathway To Inhibit Phagosome–Lysosome Fusion. J. Immunol. 201, 1421–1433. 10.4049/jimmunol.1800530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press B., Feng Y., Hoflack B., Wandinger-Ness A. (1998). Mutant Rab7 causes the accumulation of cathepsin D and cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor in an early endocytic compartment. J. Cell Biol. 140, 1075–1089. 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puertollano R., Ferguson S. M., Brugarolas J., Ballabio A. (2018). The complex relationship between TFEB transcription factor phosphorylation and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 37, e98804. 10.15252/embj.201798804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queval C. J., Brosch R., Simeone R. (2017). The Macrophage: A Disputed Fortress in the Battle against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2284. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke A. L., O’Riordan M. X. D. (2006). Intracellular innate resistance to bacterial pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1720–1729. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajashekar R., Liebl D., Seitz A., Hensel M. (2008). Dynamic Remodeling of the Endosomal System During Formation of Salmonella-Induced Filaments by Intracellular Salmonella enterica. Traffic 9, 2100–2116. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajashekar R., Liebl D., Chikkaballi D., Liss V., Hensel M. (2014). Live Cell Imaging Reveals Novel Functions of Salmonella enterica SPI2-T3SS Effector Proteins in Remodeling of the Host Cell Endosomal System. PloS One 9, e115423. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden A. E., Holden D. W., Mota L. J. (2007). Membrane dynamics and spatial distribution of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. Trends Microbiol. 15, 516–524. 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek D., Schwake M., Schröder J., Hughes H., Blanz J., Jin X., et al. (2007). LIMP-2 Is a Receptor for Lysosomal Mannose-6-Phosphate-Independent Targeting of β-Glucocerebrosidase. Cell 131, 770–783. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A., Caler E. V., Andrews N. W. (2001). Plasma Membrane Repair Is Mediated by Ca2+-Regulated Exocytosis of Lysosomes. Cell 106, 157–169. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00421-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rengarajan M., Theriot J. A. (2020). Rapidly dynamic host cell heterogeneity in bacterial adhesion governs susceptibility to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 31, 2097–2106. 10.1091/mbc.E19-08-0454 mbc.E19-08-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter T., Vorwerk S., Liss V., Chao T.-C., Hensel M., Hansmeier N. (2020). Proteomic analysis of Salmonella-modified membranes reveals adaptations to macrophage hosts. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 19, 900–912. 10.1074/mcp.RA119.001841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roczniak-Ferguson A., Petit C. S., Froehlich F., Qian S., Ky J., Angarola B., et al. (2012). The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci. Signal. 5, ra42. 10.1126/scisignal.2002790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer J., Kornfeld R. (2001). Lysosomal Hydrolase Mannose 6-Phosphate Uncovering Enzyme Resides in the trans-Golgi Network. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1623–1631. 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottner K., Stradal T. E. B., Wehland J. (2005). Bacteria-Host-Cell Interactions at the Plasma Membrane: Stories on Actin Cytoskeleton Subversion. Dev. Cell 9, 3–17. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. G. (2001). Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today and here tomorrow. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 569–578. 10.1038/35085034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini D. M. (2017). Twenty-five years of mTOR: Uncovering the link from nutrients to growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 11818–11825. 10.1073/pnas.1716173114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva K., Goel M., Sudhakar M., Mehta M., Raju R., Raman K., et al. (2020. a). Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) lipid mediated lysosomal rewiring in infected macrophages modulates intracellular Mtb trafficking and survival. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 9192–9210. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.012809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva K., Goel M., Sundaramurthy V. (2020. b). Heterogeneity in the endocytic capacity of individual macrophage in a population determines its subsequent phagocytosis, infectivity and sub-cellular trafficking. Traffic Cph. Den. 21, 522–533. 10.1111/tra.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P., Klumperman J. (2009). Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: trafficking meets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 623–635. 10.1038/nrm2745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo S. P., Holden D. W. (2003). SseG, a virulence protein that targets Salmonella to the Golgi network. EMBO J. 22, 5003–5014. 10.1093/emboj/cdg517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardiello M., Ballabio A. (2009). Lysosomal enhancement: A CLEAR answer to cellular degradative needs. Cell Cycle 8, 4021–4022. 10.4161/cc.8.24.10263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible U. E., Sturgill-Koszycki S., Schlesinger P. H., Russell D. G. (1998). Cytokine activation leads to acidification and increases maturation of Mycobacterium avium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 160, 1290–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto S., Tsujimura K., Koide Y. (2011). Rab GTPases regulating phagosome maturation are differentially recruited to mycobacterial phagosomes. Traffic Cph. Den. 12, 407–420. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C., Ballabio A. (2011). TFEB regulates autophagy: An integrated coordination of cellular degradation and recycling processes. Autophagy 7, 1379–1381. 10.4161/auto.7.11.17166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C., Malta C. D., Polito V. A., Arencibia M. G., Vetrini F., Erdin S., et al. (2011). TFEB Links Autophagy to Lysosomal Biogenesis. Science 332, 1429–1433. 10.1126/science.1204592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C., Zoncu R., Medina D. L., Vetrini F., Erdin S. S. S., Erdin S. S. S., et al. (2012). A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 31, 1095–1108. 10.1038/emboj.2012.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C., Fraldi A., Medina D. L., Ballabio A. (2013). Signals from the lysosome: a control centre for cellular clearance and energy metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 283–296. 10.1038/nrm3565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood R. K., Roy C. R. (2013). A rab-centric perspective of bacterial pathogen-occupied vacuoles. Cell Host Microbe 14, 256–268. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono M., Lu Y.-J., Porter K., Kvitko B. H., Henty-Ridilla J., Creason A., et al. (2016). The Pseudomonas syringae Type III Effector HopG1 Induces Actin Remodeling to Promote Symptom Development and Susceptibility during Infection. Plant Physiol. 171, 2239–2255. 10.1104/pp.16.01593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotland Y., Krämer H., Groisman E. A. (2003). The Salmonella SpiC protein targets the mammalian Hook3 protein function to alter cellular trafficking. Mol. Microbiol. 49, 1565–1576. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03668.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S., Richardson E. T., Athman J. J., Shi L., Wearsch P. A., McDonald D., et al. (2014). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Lipoprotein LprG Binds Lipoarabinomannan and Determines Its Cell Envelope Localization to Control Phagolysosomal Fusion. PloS Pathog. 10, e1004471. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone R., Bobard A., Lippmann J., Bitter W., Majlessi L., Brosch R., et al. (2012). Phagosomal Rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis Results in Toxicity and Host Cell Death. PloS Pathog. 8, e1002507–e1002507. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. K., Kapoor A., Lomash R. M., Kumar K., Kamerkar S. C., Pucadyil T. J., et al. (2018). Salmonella SipA mimics a cognate SNARE for host Syntaxin8 to promote fusion with early endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 217, 4199–4214. 10.1083/jcb.201802155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. C., Cirulis J. T., Casanova J. E., Scidmore M. A., Brumell J. H. (2005). Interaction of the Salmonella-containing Vacuole with the Endocytic Recycling System. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24634–24641. 10.1074/jbc.M500358200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. C., Heo W. D., Braun V., Jiang X., Macrae C., Casanova J. E., et al. (2007). A network of Rab GTPases controls phagosome maturation and is modulated by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Cell Biol. 176, 263–268. 10.1083/jcb.200611056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogi K. M., Lien K. A., Johnson J. R., Krogan N. J., Stanley S. A. (2017). The Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Gefitinib Restricts Mycobacterium tuberculosis Growth through Increased Lysosomal Biogenesis and Modulation of Cytokine Signaling. ACS Infect. Dis. 3, 564–574. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele-Mortimer O. (2008). The Salmonella-containing Vacuole – Moving with the Times. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 38–45. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M. A., Leung K. Y., Zwick M., Portillo F. G., Finlay B. B. (1996). Identification of a Salmonella virulence gene required for formation of filamentous structures containing lysosomal membrane glycoproteins within epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 20, 151–164. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch S., Braulke T. (2005). “Transport of Lysosomal Enzymes,” in Lysosomes Medical Intelligence Unit. Ed. Saftig P. (Boston, MA: Springer US; ), 17–26. 10.1007/0-387-28957-7_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramurthy V., Barsacchi R., Samusik N., Marsico G., Gilleron J., Kalaidzidis I., et al. (2013). Integration of chemical and RNAi multiparametric profiles identifies triggers of intracellular mycobacterial killing. Cell Host Microbe 13, 129–142. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramurthy V., Korf H., Singla A., Scherr N., Nguyen L., Ferrari G., et al. (2017). Survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG in lysosomes in vivo. Microbes Infect. 19, 515–526. 10.1016/j.micinf.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto J., Namolovan A., Osborne S. E., Coombes B. K., Brumell J. H. (2009). Salmonella-Containing Vacuoles Display Centrifugal Movement Associated with Cell-to-Cell Transfer in Epithelial Cells. Infect. Immun. 77, 996–1007. 10.1128/IAI.01275-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B. L. (2015). Bacteria-Containing Vacuoles: Subversion of Cellular Membrane Traffic and Autophagy. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 25, 163–174. 10.1615/critreveukaryotgeneexpr.2015013572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieux I., Webster P., Ravesloot J., Boron W., Lunn J. A., Heuser J. E., et al. (1992). Lysosome recruitment and fusion are early events required for trypanosome invasion of mammalian cells. Cell 71, 1117–1130. 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80061-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen A. M., Zoncu R. (2017). Emerging Roles for the Lysosome in Lipid Metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 833–850. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]