Abstract

Only a handful of institutions in the country have an established robotic surgery program. Evolution of robotic surgery in the colorectal division, from inception to recent times, is presented here. All the patients undergoing robotic colorectal surgery from the inception of the program (September 2014) to August 2019 were identified. The patient and treatment details and short-term outcomes were collected retrospectively from the prospectively maintained database. The cohort was divided into four chronological groups (group 1 being the oldest) to assess the surgical trends. There were 202 patients. Seventy-one percent were male. Mean BMI was 23.25. Low rectal tumours were most common (47%). A total of 74.3% patients received neo-adjuvant treatment. Multivisceral resection was done in 22 patients, including 4 synchronous liver resections. Average operating time for standard rectal surgery was 280 min with average blood loss of 235 ml. The mean nodal yield was 14. Circumferential resection margin positivity was 6.4%. The mean hospital stay for pelvic exenteration was significantly higher than the rest of the surgeries (except for posterior exenteration and total proctocolectomy) (p = 0.00). Clavin-Dindo grade 3 and 4 complications were seen in 10% patients. As the experience of the team increased, more complex cases were performed. Blood loss, margin positivity, nodal yield, leak rates and complications were evaluated group wise (excluding those with additional procedures) to assess the impact of experience. We did not find any significant change in the parameters studied. With increasing experience, the complexity of surgical procedures performed on da Vinci Xi platform can be increased in a systematic manner. Our short-term outcomes, i.e. nodes harvested, margin positivity, hospital stay and morbidity, are on par with world standards. However, we did not find any significant improvement in these parameters with increasing experience.

Keywords: Robotic colorectal cancer surgery

Introduction

Robotic surgery came into the scene in 2002. It progressed rapidly in all the surgical specialties. However, it is a very recent addition to the surgical field in India. Only a handful of institutions in the country now have an established robotic surgery program while several others are in various phases of establishment.

Tata Memorial Centre was the first institution in the country to install daVinci Xi platform in 2014. Since then, the Xi platform is being used by several divisions of surgical oncology in the centre. The need to get over the learning curve and take up more challenging surgeries has to be balanced with financial burden and evolving indications for robotic surgery. In this article, we are presenting the evolution and experience of robotic surgery in the colorectal division over the last 5 years, showcasing how the robotic services progressed during this period and their impact on short-term outcomes.

Materials and Methods

All the patients who underwent robotic colorectal surgery between September 2014 and August 2019 were identified. The patient details were collected retrospectively from the prospectively maintained database. All colorectal patients were assessed with complete clinical evaluation, colonoscopy and biopsy: contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of thorax, abdomen and pelvis in colon cancer, CECT abdomen thorax along with MRI of the pelvis in rectal cancer, complete blood work along with serum CEA levels. All patients were discussed in multi-disciplinary team meetings for treatment decisions.

Neo-adjuvant Treatment

Colonic and upper rectal tumours were not given any neoadjuvant treatment before surgery. Mid and low rectal tumours that were T3–4, node positive, with threatened or involved circumferential resection margin (CRM) on MRI received conventional long-course neoadjuvant chemoradiation regimen (LCRT) which consisted of external beam radiation (a total dose of 50.4 Gy in 25 fractions) along with oral capecitabine. After completion of LCRT, all patients underwent restaging contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI, after a gap of 4–6 weeks. If CRM remained positive, additional 4 cycles of capecitabine/5FU and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy were administered. Early T3 (T3a-T3b), CRM negative cases received short course radiotherapy (SCRT) (25 Gy in 5 fractions) selectively.

We assessed lateral pelvic lymph nodes in all patients radiologically. Patients with radiologically suspicious pelvic lymph nodes after neoadjuvant treatment were considered for side specific lateral pelvic lymph node dissection.

Patients with liver metastasis received SCRT followed by 4 cycles of chemotherapy before surgery.

Surgical Method for Robotic Rectal Surgery

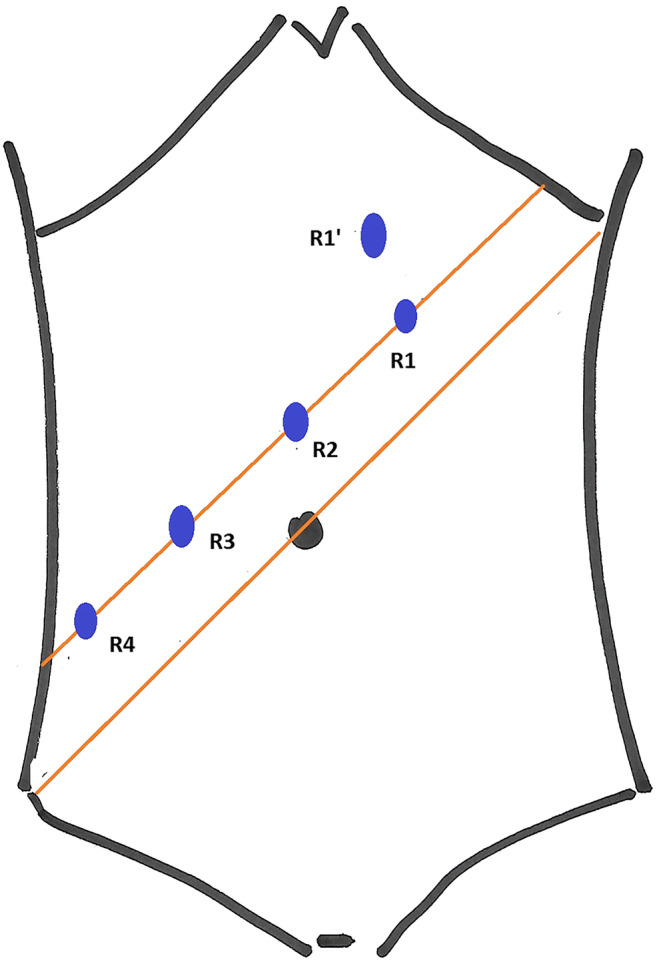

Patient was given 30 degree head low and left up position. Positions of robotic ports are shown in the Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Robotic port positions for rectal surgery. R1-left upper quadrant port. R1’-new left upper quadrant port. R2-camera port. R3, R4-right-sided ports

Details

Camera port was inserted 2 cm above umbilicus in the midline (R2). After establishing pnemoperitoneum, two right side ports (R3, R4) and one left side port (R1) were established along a straight line that was 2 cm above and parallel to the line joining right anterior superior iliac spine and umbilicus (Fig. 1), with 7 cm gap between the adjoining ports. Two assistant ports were established: 5 mm port between R2 and R3 and a 12 mm port between R3 andR4. This 12 mm port was used for distal rectal transection using stapler. Assist ports were 7–8 cm away from the robotic ports. In thinner individuals and in patients where complete splenic flexure mobilization was required, the R1 was moved away from the reference line and towards the epigastrium (position R1’ in Fig. 1), to avoid instrument clash and better range of motion. Robot was docked after bowel placement. During the initial days, we followed single stage dual docking technique wherein the robot was targeted at the root of inferior mesenteric artery in the first phase and at the pelvis in second phase. Later, we started targeting the robot only once, at the left iliac fossa, for both abdominal and pelvic parts of the rectal surgery. Plane under the inferior mesenteric vein was created first followed by medial to lateral mobilization of the rectal tube till the lateral peritoneal reflection. Splenic flexure mobilization is completed either in infracolic or supracolic approach. Wherever the CRM was clear, nerve plexus was identified and preserved at all critical points (root of inferior mesenteric artery, sacral promontory and pelvis) by sharp dissection along the TME planes. Cotton tape was used to provide traction on rectal tube during the pelvic phase. Distal rectal transaction was done from the 12-mm assist port using Echelon 60 endostapler. Bowel continuity established with Ethicon CDH circular staplers. All mid and low rectal tumours, patients undergoing intersphincteric resections (ISR), ultralow anterior resections (ULAR), total proctocolectomy (TPC), anterior resections beyond TME and sphincter preserving posterior exenteration received diversion ileostomy. Port position and techniques were the same as standard rectal resections even for posterior exenteration, total pelvic exenteration and lateral pelvic node dissection. In exenterative procedures, posterior rectal mobilization was completed first, and then, anterior dissection of bladder/uterus was carried out. For total proctocolectomy, similar port positions were used, but ports were established along the line joining right anterior superior iliac spine and umbilicus.

Right and left colectomies were performed with robotic ports inserted along the midline vertically. Synchronous liver resection was also performed using robotic platform. Patient was given reverse Trendelnerg position. Same robotic ports and camera ports are used. The boom was rotated. And two assist ports were established in the lower abdomen.

Surgical Complications

Clavein-Dindo classification was used to grade the surgical complications. The complications were defined as any deviations from the normal post-operative course.

Statistical Analysis

The categorical variables are presented in percentages while continuous variables are presented as mean and median values with range. Categorical variables were compared using Chi square test and means were compared using ANOVA test. Homogeneity of variance was analysed with Levine’s test and Games Howell’s test was used when homogeneity was absent. Graphical presentation was used wherever deemed necessary.

Results

During the study period, 202 patients underwent robotic colorectal surgery. The demographic features, disease characters and neoadjuvant treatment details are summarized in Table 1. Mean BMI of patients was 23.25 (range: 14.95 to 37.75). Low rectal tumours were the most common 47% (95 patients), followed by middle 27.2% (55 patients) and upper rectal tumours 15.3% (31 patients). Colonic cancer (21 patients, 10%) constituted a small percentage of the cohort. A total of 59.9% of the patients were T3 rectal cancers. A total of 74.3% (150 patients) patients received neo-adjuvant treatment. LCRT was given to 61.4% (124 patients) patients and 24 received SCRT. There was a significant difference in the time interval between radiation and surgery among patients receiving LCRT vs. SCRT vs. SCRT + chemotherapy (p = 0.002).

Table 1.

Patient demographics, disease characters and neoadjuvant treatment details

| Parameters | Total numbers (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 144 (71.3%) |

| Female | 58 (28.7%) |

| Median age in years (range) | 49 (20–79) |

| Mean BMI (range) | 23.25 (14.95–37.75) |

| BMI | |

| < 20 | 40 (19.8%) |

| 20.1–25.0 | 103 (50.1%) |

| 25.1–30.0 | 50 (24.75%) |

| 30.1–35.0 | 6 (3%) |

| > 35.1 | 3 (1.5%) |

| ASA grade | |

| I | 122 (60.4%) |

| II | 75 (37.1%) |

| III | 5 (2.5%) |

| Rectal cancers | |

| Upper 1/3 | 31 (15.3%) |

| Middle 1/3 | 55 (27.2%) |

| Lower 1/3 | 95 (47%) |

| Colon | 21 (10%) |

| Rectal cancer T stage | |

| T1 | 4 (1.98%) |

| T2 | 45 (22.28%) |

| T3 | 121 (59.90%) |

| T4 | 24 (11.88%) |

| Patients with metastatic disease | 12 (5.94%) |

| Liver metastasis | 9 (4.45%) |

| Mean pre-treatment CEA levels (IU/ml) | 33.81 |

| Neo-adjuvant therapy | |

| Yes | 148 (74.3%) |

| LCRT | 124 (61.4%) |

| SCRT | 24 (11.9%) |

| No | 54 (26.7%) |

| Mean time interval between radiation and surgery in rectal cancer (in weeks) | |

| LCTRT (n = 122) | 13.47 |

| SCRT (n = 10) | 7.54 |

| SCRT + chemotherapy (n = 14) | 20.76 |

Surgical details are summarised in Table 2. The most common procedure was low anterior resection (LAR) (72 patients, 35.6%). Multivisceral resection was done in 22 patients, including 4 liver resections. Excluding the multi-visceral resections, the average blood loss was 235 ml (ranging from 50 to 3000 ml). Multi-visceral resections were associated with higher blood loss of 925 ml (ranging from 100 to 3300 ml). Average operating time for standard rectal surgery was 280 min (range 100 to 380 min). Only two patients required conversion from robotic rectal surgery.

Table 2.

Procedures and intra-operative outcomes

| Total number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Procedures | |

| Anterior resection (AR) | 10 (4.9%) |

| Low anterior resection (LAR) | 67 (33.16%) |

| Abdominal perineal resection (APR) | 36 (17.82%) |

| Intersphincteric resection (ISR) | 61 (30.20%) |

| Beyond TME APR | 5 (2.47%) |

| Beyond TME LAR | 5 (2.47%) |

| Posterior exenteration | 6 (2.97%) |

| Total pelvic exenteration | 6 (2.97%) |

| Right hemicolectomy | 2 (1%) |

| Left hemicolectomy | 1 (0.5%) |

| Total Proctcolectomy | 3 (1.5%) |

| Extended procedures | |

| Seminal vesicle excision | 3 |

| Post. vaginal wall excision | 3 |

| Posterior exenteration | 5 |

| Total pelvic exenteration | 5 |

| Other | 3 |

| Liver resection | 4 |

| Denonvillers Fascia excision | 2 |

| Adnexectomy | 2 |

| Mean operative time for rectal surgery | 280 (100–380) min |

| Mean blood loss in rectal surgery | 235 ml (50–3000) |

| Mean blood loss in multi visceral resections | 925 ml (100–3300) |

| Diversion stoma in rectal cancer | |

| Yes | 138 (68.3%) |

| No | 12 (5.9%) |

| Not applicable | 52 (25.8%) |

| Ligation of inferior mesenteric artery (all cases) | |

| High | 107 (52.9%) |

| Low | 86 (42.6%) |

| Not applicable | 4 (1.9%) |

| Data missing | 5 (2.5%) |

The pathological outcomes are presented in Table 3. The most common pathological T stage was pT3 (38.6%). The lymph node positivity rate was 40.1%. TME was complete in 98% of patients. The mean lymph nodal yield in our series was 14 (range 0–73). CRM positivity was seen in 13 patients (6.4%). Eight were in abdominoperineal resection surgeries and 2 in intersphincteric resections. The distal resection margin in our series was positive in only one patient and mean distal resection margin was 3.0 cm. Pathological complete response to neoadjuvant therapy was present in 51 patients (34.7%). Radiologically suspicious pelvic lymph nodes were present in 27 patients of rectal cancer before the treatment. Out of these 27 patients, 24 patients underwent either unilateral or bilateral robotic pelvic lymph node dissection after completion of neoadjuvant therapy. Mean unilateral pelvic lymph node yield was 8. Pathological positive pelvic lymph nodes were present in six patients.

Table 3.

Pathological details

| Total number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Type of histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 186 (91.2) |

| Well differentiated | 16 (8.6) |

| Moderately differentiated | 139 (74.7) |

|

Poorly differentiated Squamous cell carcinoma |

31 (16.7) 1 (0.5) |

| Melanoma | 4 (2.0) |

| Adenomatous polyp | 7 (3.4) |

| Neuro-endocrine tumours | 3(1.5) |

| T stage | |

| Tx | 3 (1.5) |

| Tis | 1(0.5) |

| T1 | 18(8.9) |

| T2 | 43 (21.3) |

| T3 | 78 (38.6) |

| T4 | 5 (2.5) |

| Complete response | 53 (26.2) |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 121 (59.9) |

| N1 | 53 (26.2) |

| N2 | 25 (12.4) |

| N3 | 3 (1.5) |

There was significant difference between hospital stay among different procedures (surgeries with additional procedures are excluded) (Table 4, Fig. 2). The mean hospital stay for pelvic exenteration was significantly higher than the rest of the surgeries, except for posterior exenteration and total proctocolectomy (p = 0.00).

Table 4.

Hospital stay for different surgical procedures

| Surgery | Number | Mean hospital stay (in days) |

|---|---|---|

| Right hemicolectomy | 2 | 3.50 |

| Anterior resection (AR) | 10 | 6.00 |

| Low anterior resection (LAR) | 51 | 8.12 |

| Ultralow anterior resection (ULAR) | 7 | 7.71 |

| Abdominoperineal resection (APR) | 30 | 6.60 |

| Total proctocolectomy (TPC) | 2 | 10.50 |

| Total pelvic exenteration | 4 | 22.50 |

| Posterior exenteration | 3 | 9.67 |

| Intersphincteric resection | 48 | 7.52 |

| Anterior resection beyond TME | 2 | 11.00 |

Fig. 2.

Hospital stay for various procedures

AR anterior resection, LAR low anterior resection, ULAR ultra low anterior resection, APR abdomino perineal resection, TPC total proctocolectomy

Post-operative Complications

Twenty-one patients (10% patients) had Clavin-Dindo grade 3 and 4 complications. We had one post-operative mortality secondary to pulmonary embolism. Eight patients (4%) had anastomotic leak, out of which seven patients needed re-exploration. There was no difference in the anastomotic leak rates between patients with diversion stoma and without the stoma in rectal cancer surgery (5.1% vs. 0.0%; p = 0.615). However, the leak rates were significantly higher in patients receiving LCRT vs. SCRT (7/122 vs. 0/24, p = 0.000). Post-operative prolonged ventilation was required for four patients. Twelve patients (5.9%) were re-admitted soon after discharge for minor complications.

Time Trends and Learning Curve

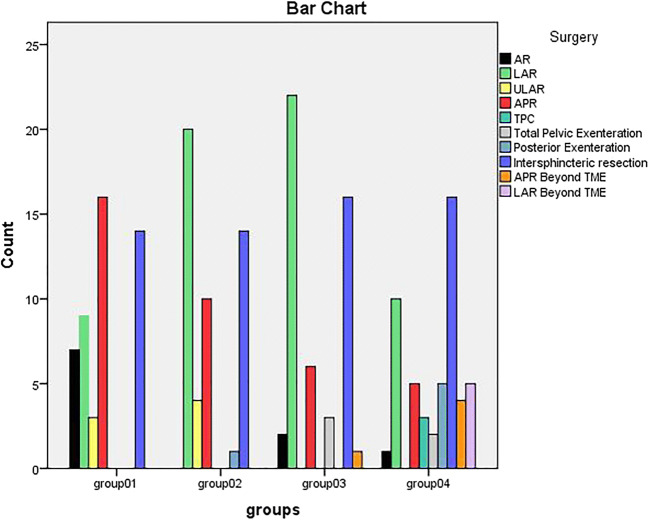

We divided the cohort into four chronological groups (group 1 being the oldest and group 4 the most recent) to assess the surgical trends and impacts. Figure 3 shows that as the team’s experience grew, more complex surgeries were taken up.

Fig. 3.

Type of surgeries separated in Four distinct chronological groups

Additional procedures like pelvic node dissection, liver resection, vaginal wall excisions, seminal vesicle excisions and prostatic shave also showed a steady increase (Fig. 4). Our first lateral pelvic node dissection was in the 43rd case. First synchronous liver resection was in the 64th case. First pelvic exenteration was the 109th case.

Fig. 4.

Trend in additional procedures

Blood loss, CRM, DRM positivity, nodal yield, leak rates and complications were compared among the four groups (cases with additional procedures were excluded) to assess the change in outcomes. We did not find any significant change in the parameters studied (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of surgical outcomes in chronological groups

| Parameter assessed | Group 01 | Group 02 | Group 03 | Group 04 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | 49 | 48 | 46 | 31 | |

| Mean blood loss (ml) | 276 | 257 | 158 | 291 | 0.173 |

| Mean nodal yield (n) | 14.7 | 13.8 | 12.7 | 13.6 | 0.799 |

| CRM positivity (n) | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0.290 |

| DRM positivity (n) | 0` | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.466 |

| Anastomotic leak (n) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0.109 |

| Morbidity | |||||

| Grade I | 2 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 0.313 |

| Grade II | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | |

| Grade IIIa | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Grade IIIb | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Grade IVa | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Grade IVb | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade V | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade 0 | 39 | 37 | 34 | 22 | |

CRM circumferential resection margin, DRM distal resection margin

Discussion

Colorectal division of Tata Memorial Centre became an independent unit in 2013. At that time, very small number of the colorectal surgeries was performed by minimal access route. With the formation of colorectal unit, the lead authors who were already experienced in laparoscopic colorectal surgery aggressively pushed for minimal access colorectal surgery. In 2014, daVinci Xi was installed in the institution and was shared among other surgical units. During the initial period, simple high anterior resections and abdominoperineal resections were chosen in order to standardize the technique and operative steps and to overcome the learning curve. This phase was about correct port placements, troubleshooting during docking and solving technical glitches, exploring port hopping for different phases of surgery.

As the laparoscopic experience among the team improved along with the presence of two full time colorectal fellows, it was realized that most of the colorectal cases could be done laparoscopically. This insight had ramifications. One was more and more cases were done in the peripheral division of the centre. Second was only technically difficult cases were selected for the robotic surgery. This is evident in Fig. 3. Considering the constant churning of trainee residents, considerable time used to be spent in docking the robot. Hence, case selection was given utmost priority for the judicious use of robot. Several indicators of technically challenging surgery were proximity to anal verge when sphincter complex was uninvolved, narrow pelvis, extra TME excisions like seminal vesicle excision–prostatic shave, lateral pelvic node dissection.

Figures 3 and 4 show how the colorectal robotic surgery evolved in the institution. There were several technical refinements too. Initially, all the robotic ports were inserted in straight line (Fig. 1). But with experience, we realized that with such port positions, splenic flexure mobilization was difficult, especially in short patients. Hence, we started to insert the left-sided robotic port (R1) more towards the midline near the epigastrium (R1’) (Fig. 1). This prevented clashing of the robotic arms as well. We also evaluated camera hopping-R3 camera for pedicle dissection and R2 camera for pelvic dissection. However, we did not find it very useful. In the early days, we used to have single docking and dual phase rectal surgeries. Initially, the camera was targeted at the root of inferior mesenteric artery for abdominal part of the dissection. Later, for pelvic dissection camera was targeted at the pelvis. But with robotic port placements where each port was as far as possible from the neighbouring port and the target organ, it was possible to target at the left iliac fossa and complete the surgery with single docking and single phase manner. [1] Based on this experience, several standardized methods have been published already from the colorectal unit [2–5].

Learning curve in one of the important aspect evaluated in minimal access surgery. In robotic colorectal surgery, several studies have evaluated this topic where in the number of cases required to overcome the learning curve varies from 15 to 43 [6–10]. The wide variations are due to different platforms used and combinations of hybrid and non hybrid procedures, single phase–dual phase surgeries, single docking, and dual docking techniques. However, the number required to get over the learning curve is still less compared to laparoscopic learning curve [11, 12]. A review showed that it takes 30 cases to decrease the operative time and reach a plateau. The mean number of cases required for a surgeon to be called an expert in robotic surgery was considered to be 39 cases [13]. Majority of these studies evaluated the learning curve based on operative times. Being a teaching institute with constant rotation of trainee residents, our docking time and operative time used to change based on the experience of the trainee. It is known that docking time is one of the key components in contributing to increased operative time in robotic surgeries [14]. Hence, in the present cohort, we did not evaluate the learning curve based on operative times. In our previously published study of 2016, the docking time was noted to be 9 min in the presence of two experienced fellows [1].

We divided our experience into four chronological groups. This was based on the previously published studies on learning curve in robotic colorectal surgeries. We did not find any significant change with increasing experience in the parameters studied, i.e. margin positivity rates, mean number of nodes harvested, blood loss, complications and leak rates (Table 5). There were several varieties of colorectal cases performed over this entire study period. As the experience of robotic surgery increased more and more, complex and challenging cases were taken up. Thus, the cohort was considerably heterogeneous. Hence, we did not perform analysis of learning curve using CUSUM charts or other statistical methods. An important but often less regarded point in this aspect is surgeon’s prior experience in colorectal surgery and its impact on learning curve [15]. Giulianotti et al. in their study found that the learning curve at the console is relatively short, even for an inexperienced surgeon. It does not take long to learn how to do perfect knots and suturing and to have full control of robotic movements, but to perform advanced procedures; full training in open and laparoscopic surgery is mandatory [16]. In the present series, both the lead surgeons were highly experienced in minimal access colorectal surgeries even before the instalment of robotic system. This could be one of the important reasons for not finding any significant change in the outcomes as the robotic colorectal surgeries increased in number.

Conversion to open surgery was also one of the important factors analysed in learning curve analysis [17]. Large series have reported to conversion rates of 5–10% [18–20]. But in the present study, only two conversions happened thus making it difficult to analyse this factor. Obesity, haemorrhage, advanced disease and difficult dissection are cited as reasons for conversion. The median BMI in the present population was 23.25. We routinely perform MRI for all our patients after completion of radiation to help in precise surgical planning. These factors along with the experience in minimal access surgery may be the reason for lesser conversions in the present cohort. Number of nodes harvested is considered a marker of surgical expertise and the results in the present cohort match with previously published studies [19, 21].

The hospital stay in patients undergoing AR, LAR, and APR was more than 5 days in the series. This is longer than that published in previous large studies [19, 20] A Korean study had reported a longer hospital stay for robotic ULAR (hospital stays 09 days in robotic group) [22]. Our own institutional experience has shown that after anterior resection, the leak usually occurs between PODS 3 and 7 [23]. Most of our patients come from outside the state, travel long distances and are economically backward. We do not have an established patient outreach program. Hence, most patients stay back in the hospitals till the drains are removed. This could be an important reason for longer hospital stays in the series, and hence, hospital stay was not analysed while comparing the outcome parameters.

Beyond TME resections, via open and laparoscopic routes are well established in our centre [23–26]. Taking inspiration from our experience in open and laparoscopic beyond TME resections, we gradually incorporated beyond TME excisions in robotic colorectal surgeries as well. However, the number of such procedures is small. These procedures are associated with longer operating times, higher blood loss and longer hospital stays. At present, the scientific data on the role of robotic surgery in such cases is lacking.

With the results of the ROLARR trial [18] clearly underlining the fact that laparoscopy is not inferior to robotic, in a resource-restrained country like India, judicious use of robotic platform to justify the cost is important. Cost of the robotic surgery has not been evaluated in the study. However, based on our unpublished data, robotic colorectal surgery is roughly 1.5 lakh rupees more than laparoscopic surgery. There is a wide variation in the cost of robotic surgery from country to country [14]. Considering that majority of the Indian population is not insured, it is prudent to use the robotic services judiciously. Another aspect that is unexplored in this study is sexual and urinary function of the patients undergoing robotic surgeries. Kim et al. showed that both these are better preserved in robotic surgery as compared to laparoscopic surgery [27]. With majority of our colorectal cancer patients being younger than 50 years, the goal of sexual and urinary function preservation in them seems to be a justified indication for robotic surgery in these patients.

Conclusions

With increasing experience, the complexity of surgical procedures performed on da Vinci Xi platform can be increased in a systematic manner. Our short-term outcomes, i.e. nodes harvested, margin positivity, hospital stay are on par with world standards. However, we did not find any significant improvement in these parameters with increasing experience.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tamhankar AS, Jatal S, Saklani A. Total robotic radical rectal resection with da Vinci Xi system: single docking, single phase technique. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg MRCAS. 2016;12(4):642–647. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kammar P, Sasi S, Kumar N, Rohila J, de Souza A, Saklani A (2019) Robotic posterior pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis 21(5):606 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kammar P, Verma K, Sugoor P, Saklani A Complete robotic lateral pelvic node dissection using the da Vinci Xi platform in rectal cancer – a video vignette. Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 11];20(11):1053–4. Available from: 10.1111/codi.14412 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kammar P, Bakshi G, Verma K, Sugoor P, Saklani A. Robotic total pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer – a video vignette. Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 11];20(8):731–731. Available from: 10.1111/codi.14256 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Sasi S, Rohila J, Kammar P, Kurunkar S, Desouza A, Saklani A Robotic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection in rectal cancer – a video vignette. Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 11];20(6):554–5. Available from: 10.1111/codi.14110 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Jiménez-Rodríguez RM, Díaz-Pavón JM, de la Portilla de Juan F, Prendes-Sillero E, Dussort HC, Padillo J. Learning curve for robotic-assisted laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. Int J Color Dis. 2013;28(6):815–821. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi T, Kinugasa Y, Shiomi A, Sato S, Yamakawa Y, Kagawa H, Tomioka H, Mori K. Learning curve for robotic-assisted surgery for rectal cancer: use of the cumulative sum method. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(7):1679–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3855-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sng KK, Hara M, Shin J-W, Yoo B-E, Yang K-S, Kim S-H The multiphasic learning curve for robot-assisted rectal surgery. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Nov 10];27(9):3297–307. Available from: 10.1007/s00464-013-2909-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Park EJ, Kim CW, Cho MS, Baik SH, Kim DW, Min BS, Lee KY, Kim NK. Multidimensional analyses of the learning curve of robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: 3-phase learning process comparison. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(10):2821–2831. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foo CC, Law WL. The learning curve of robotic-assisted low rectal resection of a novice rectal surgeon. World J Surg. 2016;40(2):456–462. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park IJ, Choi G-S, Lim KH, Kang BM, Jun SH Multidimensional Analysis of the learning curve for laparoscopic resection in rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Nov 10];13(2):275–81. Available from: 10.1007/s11605-008-0722-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Tekkis PP, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Fazio VW. Evaluation of the learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: comparison of right-sided and left-sided resections. Ann Surg. 2005;242(1):83–91. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167857.14690.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiménez-Rodríguez RM, Rubio-Dorado-Manzanares M, Díaz-Pavón JM, Reyes-Díaz ML, Vazquez-Monchul JM, Garcia-Cabrera AM, Padillo J, de la Portilla F. Learning curve in robotic rectal cancer surgery: current state of affairs. Int J Color Dis. 2016;31(12):1807–1815. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Asari S, Min BS Robotic colorectal surgery: a systematic review [Internet]. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2012 [cited 2019 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/isrn/2012/293894/

- 15.Huang C-W, Yeh Y-S, Ma C-J, Choy T-K, Huang M-Y, Huang C-M, Tsai HL, Hsu WH, Wang JY. Robotic colorectal surgery for laparoscopic surgeons with limited experience: preliminary experiences for 40 consecutive cases at a single medical center. BMC Surg. 2015;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giulianotti PC, Coratti A, Angelini M, Sbrana F, Cecconi S, Balestracci T, et al Robotics in general surgery: personal experience in a large community hospital. Arch Surg [Internet]. 2003 Jul 1 [cited 2019 Nov 10];138(7):777–84. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/395121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Polat F, Willems LH, Dogan K, Rosman C. The oncological and surgical safety of robot-assisted surgery in colorectal cancer: outcomes of a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(11):3644–3655. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-06653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jayne D, Pigazzi A, Marshall H, Croft J, Corrigan N, Copeland J, et al. Effect of robotic-assisted vs conventional laparoscopic surgery on risk of conversion to open laparotomy among patients undergoing resection for rectal cancer: The ROLARR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1569–1580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speicher PJ, Englum BR, Ganapathi AM, Nussbaum DP, Mantyh CR, Migaly J. Robotic low anterior resection for rectal Cancer: a national perspective on short-term oncologic outcomes. Ann Surg. 2015;262(6):1040–1045. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halabi WJ, Kang CY, Jafari MD, Nguyen VQ, Carmichael JC, Mills S, Stamos MJ, Pigazzi A. Robotic-assisted colorectal surgery in the United States: a nationwide analysis of trends and outcomes. World J Surg. 2013;37(12):2782–2790. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garfinkle R, Abou-Khalil M, Bhatnagar S, Wong-Chong N, Azoulay L, Morin N, Vasilevsky CA, Boutros M (2019) A comparison of pathologic outcomes of open, laparoscopic, and robotic resections for rectal cancer using the ACS-NSQIP proctectomy-targeted database: a propensity score analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 23(2):348–356 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Baek SJ, Al-Asari S, Jeong DH, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic coloanal anastomosis with or without intersphincteric resection for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(11):4157–4163. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jatal S, Pai VD, Demenezes J, Desouza A, Saklani AP Analysis of risk factors and management of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery: an Indian Series. Indian J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Nov 10];7(1):37–43. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4811816/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sinukumar S, Engineer R, Saklani A (2015) Preliminary experience with lateral pelvic lymph node dissection in locally advanced rectal cancer. Indian J Gastroenterol 34(4):320–324 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Pai VD, Bhandare M, Saklani AP. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with enbloc resection of seminal vesicle for locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26(3):209–212. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pokharkar A, Kammar P, D’souza A, Bhamre R, Sugoor P, Saklani A. Laparoscopic pelvic exenteration for locally advanced rectal cancer, technique and short-term outcomes. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28(12):1489–1494. doi: 10.1089/lap.2018.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pubmeddev KH et al The impact of robotic surgery on quality of life, urinary and sexual function following total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a propensity s... - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2019 Nov 14]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29460997/