Abstract

Purpose

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of available literature to investigate the efficacy of the intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in couples with non-male factor with respect to the clinical outcomes.

Methods

The literature search was based on EMBASE, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library. All studies published after 1992 until February 2020 and written in English addressing patients in the presence of normal semen parameters subjected to ICSI and in vitro fertilization (IVF) were eligible. Reference lists of retrieved articles were hand-searched for additional studies. The primary outcomes were fertilization rate, clinical pregnancy rate, and implantation rate; the secondary outcomes were good-quality embryo rate, miscarriage rate, and live birth rate.

Results

Four RCTs and twenty-two cohort studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included. Collectively, a meta-analysis of the outcomes in RCTs showed that compared to IVF, ICSI has no obvious advantage in fertilization rate (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.83–1.62), clinical pregnancy rate (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.66–1.64), implantation rate (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 0.67–1.86), and live birth rate (RR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.43–3.15). Pooled results of cohort studies demonstrated a statistically significant higher fertilization rate (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.03–1.31) and miscarriage rate (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06) in the ICSI group; furthermore, higher clinical pregnancy rate (RR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.77–0.94), implantation rate (RR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.65–0.95), and live birth rate (RR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.79–0.94) was founded in the IVF group; no statistically significant difference was observed in good-quality embryo rate (RR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.93–1.04).

Conclusion

ICSI has no obvious advantage in patients with normal semen parameters. Enough information is still not available to prove the efficacy of ICSI in couples with non-male factor infertility comparing to IVF.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-020-01970-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ICSI, IVF, Non-male factor infertility, Subfertility

Introduction

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), a kind of assisted reproductive technology (ART), has become the most commonly used method of fertilization. It was primarily introduced to manage male infertility with severely impaired characteristics like nonobstructive azoospermia or no measurable sperm count [1, 2]. Although the reliability of ICSI has made it an attractive option even in non-male factor couples suffering infertility worldwide, as considered more invasive and costly than conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF), ICSI has been a controversial option for these couples with non-male factor indications [3, 4]. Furthermore, the arbitrary selection of the inseminating spermatozoon may give rise to other detrimental effects [5]. Pregnancies resulting from the use of ICSI have been found to be associated with increased incidences of congenital malformation [6, 7], chromosomal aberrations [8], and birth defects [9] compared to in vitro fertilization.

Despite the uncertainness, frequently, ICSI use has expanded to other indications, including infertility of unexplained cause, low oocyte yield, advanced female age, previously failed IVF cycles, and so forth [10–15]. It has become popularized to the stage of routine laboratory service and it is even implemented for infertility couples with normal semen parameters throughout the world. ICSI without male factor infertility may be of benefit for select patients undergoing IVF with preimplantation genetic testing and previously cryopreserved oocytes according to the Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) [16]. ICSI use remarkably increased in recent years and it should be noted that the relative increase was among patients without male factor infertility, without sufficient evidence of a benefit to use ICSI over in vitro fertilization (IVF) [17–19]. Multiple studies have been carried out on this subject recently, where reporters came to a controversial conclusion. Some studies did not show any benefit on clinical outcomes in these couples undergoing ICSI, whereas other studies demonstrated that clinical outcomes in ICSI were preferable between couples affected with non-male factors when compared with conventional IVF. It has been reported that ICSI not only improved reproductive outcomes but also reduced total fertilization failure among patents with non-male factor infertility [20, 21]. ICSI has been suggested in alternative to IVF for a woman with fertilization failure in previous IVF cycles, due to subsequent ICSI may help to improve fertility rate [22]. However, the conclusions are not coincident, and recent studies challenge the application of ICSI for non-male indications [23–25]. The application of ICSI to treat patients with non-male factor is still controversial and clinical evidence is currently lacking. Although ICSI may have a role in improving clinical outcomes, the routine use of ICSI for these indications requires further investigation.

Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to review recent literature regarding clinical outcomes following ICSI and IVF in infertility couples in the presence of normal semen parameter and to evaluate the effectiveness of ICSI in these infertility couples. Our primary clinical outcomes were fertilization rate (FR), clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), and implantation rate (IR). And, the secondary outcomes were birth rate (LBR), miscarriage rate (MR), and good-quality embryo rate.

Materials and methods

Literature search and study selection

This systematic review and meta-analysis were carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines and had been registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews Platform (PROSPERO) (CRD42020157499). A comprehensive PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane search was performed to find studies aimed to compare clinical outcomes after ICSI and IVF of infertility couples in the presence of normal semen parameters and restricted to papers fully published in English dating from 1992 until February 2020 using the following keywords: intracytoplasmic sperm injection, in vitro fertilization, non-male factor, normozoospermia, normozoospermic semen. The full search strategy was provided in supplementary data. Reference lists of potential studies were also searched for additional information. We excluded the following studies: (1) male patient with abnormal semen parameters including borderline semen as defined by WHO criteria or local laboratory standards in each center; (2) studies including rescued ICSI; (3) unavailable raw data, overlapped data sets books; (4) review articles, case reports, and study without full text. The identification of relevant studies was conducted by three of the authors independently, and discussion was needed if there were any discrepancies.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the specific papers and not available data were requested by contacting authors if necessary. All data were abstracted and put into a table format in a systematic manner. The following study characteristics were obtained: methods (study design, study duration, study unit, sample size), participants (female age, cause of infertility), and raw data of outcomes (fertilization rate, clinical pregnancy rate, implantation rate, live birth rate, good-quality embryo rate, and miscarriage rate).

Quality assessment

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was employed to evaluate the quality of individual observational study as a qualitative assessment tool. The scoring system is based on three dimensions covering the selection of groups, the comparability of groups, and the outcome of interest [26]. Meanwhile, the risk of bias of RCTs was assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool [27]. Quality assessment was carried out independently by three of the authors and disagreements were resolved through group discussion. When 10 or more studies were included in one analysis, the funnel plot would be constructed in order to assess possible publication bias with Egger’s test [28].

Statistical analysis

Comparative analysis was performed between the two groups and the effect of ICSI and IVF was assessed according to study designs separately and random-effect models were used to pool outcomes. For dichotomous data (for example, fertilization rate), the raw data in the two groups were used to calculate the Mantel–Haenszel relative risk (RR) and 95% CI. The I2 statistical test was employed to assess heterogeneity. When I2 ≥ 50%, it was considered that there was substantial heterogeneity with the included studies. Further subgroup analyses were performed to identify potential sources of heterogeneity when heterogeneity was considered to be substantial. Sensitivity analysis was undertaken for each outcome to determine whether the conclusions were robust. Data were analyzed using Review Manager 5.3 and R software (version 3.5.1).

Results

Results of the searches

A total of 1599 results yielded through database and other sources. After removing the duplicates, 962 articles were screened by title and abstract by three reviewers independently, and 881 articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. And, 54 of the remaining studies were excluded according to different reasons. Thus, 26 studies were included in the meta-analysis. A flow diagram of the searching process of these records is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection for the systematic review and meta-analysis

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 26 studies (4 RCTs and 22 cohort studies) met the aforementioned eligibility criteria and were included in this study. A total of 26,120 patients were included except three of studies did not mention sample size of patients [33, 36, 46]. The mean participant age was 29 to 41 years old across the studies. Study characteristics including study design, study unit, cause of infertility, female age, study duration, study unit, number of patients/cycles, and primary outcomes were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author, year, country | Study design | Duration | Patient characteristics | Study unit | Patients (n) | Cycles (n) | Female age (y) | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboulghar et al. [29] (1996), Egypt | Prospective cohort study | NA | Unexplained infertility | Oocyte | 22 | NA | 33 ± 4.2 | FR |

| Aboulghar et al. [30] (1996), Egypt | RCT | NA | Tubal | Patient | 116 | 116 | 35.6 ± −5.0 | FR, CPR, IR |

| Artini et al. [31] (2013), Italy | Retrospective cohort study | January 2007 to July 2012 | Severe poor responder patients (n = 386) | Cycle | 386 | 425 | 38.23 ± 3.82 | FR, CPR, good-quality embryo rate, IR, MR |

| Biliangady et al. [32] (2019), India | Retrospective cohort study | January 2012 to December 2017 | Woman aged 25 to 35 years with normal ovarian reserve | Patient | 350 | 350 | 31.20 ± 3.76 | CPR, IR, MR, LBR, |

| Boulet et al. [33] (2015), Georgia | Retrospective cohort study | 2008 to 2012 | Tubal factor, endometriosis, uterine factor, ovulatory disorder, diminished ovarian reserve, unexplained, and others | Cycle | NA | 317,996 | NA | CPR, IR, LBR |

| Bukulmez et al. [34] (2000), Turkey | RCT | NA | Tubal factor | Patient | 76 | 76 | 34.02 ± 3.84 | FR, CPR, IR |

| Eftekhar et al. [35] (2012), Iran | Retrospective cohort study | April 2009 to September 2010 | Ovarian, tubal factor, mild endometriosis, unexplained, uterine, mixed | Patient | 220 | 200 | 29.28 ± 3.86 | CPR |

| Fang et al. [14] (2012), China | Retrospective cohort study | January 2007 to December 2010 | Patients with poor ovarian reserve in whom only one or two oocytes were retrieved | Patient | 194 | 194 | 36.34 ± 4.60 | PR, CPR |

| Farhi et al. [15] (2019), Israel | Retrospective cohort study | NA | All aged ≥ 35 (unexplained, tubal factor, and patients with endometriosis) | Oocyte | 52 | 52 | 38.7 ± 2.6 | FR |

| Fernández et al. [36] (2014), Spain | Retrospective cohort study | January 2011 to April 2013 | Women with low response (oocyte number at pick up < 6 | Cycle | NA | 590 | 33.2 | IR, CPR, MR |

| Grimstad et al. [37] (2016), USA | Retrospective cohort study | 2004–2012 | Tubal ligation | Patient | 7145 | 7145 | 35.57 ± 4.01 | CPR,LBR |

| Hershlag et al. [38] (2002), USA | Prospective cohort study | January 1998 to March 30, 2001 | Unexplained infertility | Oocyte | 60 | NA | NA | FR |

| Hwang et al. [39] (2005), Taiwan | RCT | January 1998 to January 2000 | PCOS | Oocyte | 60 | 60 | 32.5 ± 2.3 | FR |

| Jaroudi et al. [40] (2003), Saudi Arabia | Retrospective cohort study | June 1997 and April 2002 | Unexplained infertility | Oocyte and Patient | 199 | NA | NA | FR |

| Khamsi et al. [41] (2001), Canada | RCT | NA | Tubal (n = 18), unknown, endometriosis, oocyte donation, therapeutic donor insemination | Oocyte | 35 | NA | 33.9 ± 5.46 | FR, good-quality embryo rate |

| Kim et al. [42] (2014), Korea | Retrospective cohort study | April 2009 to March 2013 | Tubal factor (n = 94), age factor (n = 57), endometriosis (n = 47), polycystic ovary syndrome (n = 20), and unexplained infertility (n = 78) | Cycle | 217 | 296 | 35.53 ± 4.51 | FR |

| Patients with three or less oocytes retrieved | Cycle | 88 | 100 | NA | CPR, IR, MR, good-quality embryo rate | |||

| Komsky-Elbaz et al. [21] (2013), Israel | Retrospective cohort study | January 2000 to December 2011 | Endometriosis | Oocyte | 35 | 79 | 30.9 ± 3.5 | FR |

| Ming et al. [43] (2015), China | Retrospective cohort study | January 2011 and December 2013 | Tubal factor, endometriosis, ovulatory dysfunction | Oocytes | 218 | 218 | 32.9 ± 4.1 | FR, good-quality embryo rate |

| Li et al. [24] (2018), Australia | Retrospective cohort study | July 2009 to June 2014 | Female factor infertility and unexplained infertility | Patient | 14,693 | 14,693 | NA | LBR |

| Liu et al. [44] (2018), China | Retrospective cohort study | June 2011 to May 2016 | Women with age ≥ 40 years and ≤ 5 oocytes obtained | patient | 644 | 644 | 41.34 ± 1.07 | FR, IR, CPR LBR, good-quality embryo rate |

| Van der Westerlaken et al. [45] (2005), The Netherlands | Prospective cohort study | September 1995 to February 2003 | First IVF attempt with total fertilization failure or with low fertilization (< 25%) | oocyte | 38 | 38 | 32.2 ± 3.9 | FR, CPR |

| Schwarze et al. [46] (2017), Chile | Retrospective cohort study | January 2012 to December 2014. | With non-male factor | Cycle | NA | 49,813 | 36.78 ± 4.41 | MR, LBR |

| Shveiky et al. [13] (2006), Israel | Retrospective cohort study | January 1999 to December 2002 | Unexplained infertility | Cycle | 118 | 118 | 31.5 ± 5.6 | FR, IR, PCR, LBR |

| Tannus et al. [47] (2017), Canada | Retrospective cohort study | January 2012 to June 2015 | Women aged 40–43 years | Patient | 745 | 745 | 41.17 ± 0.90 | CPR, LBR |

| Xi et al. [48] (2012), China | Retrospective cohort study | January 2009 to December 2010. | Patients in which no more than three oocytes | Cycle | 396 | 406 | NA | FR, CPR, IR, MR |

| Yang et al. [49] (1996), Qatar | Retrospective cohort study | June 1994 to September 1994 | Tubal = 10 unexplained infertility | Oocyte | 13 | 13 | 29 | FR |

In this meta-analysis, quality assessment for RCTs was performed according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and was summarized in Fig. 2. Both study design and methodology quality varied among the included four studies. Only one RCT used the optimal method of sequence generation and described exhaustively, whereas the other three studies generate the sequence in an inappropriate way or did not describe sequence generation explicitly. All the studies did not describe the method of blinding. For all cohort studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was employed to assess the quality and the NOS scores ranged from 5 to 9; the results were summarized in Table 2. All the studies provided information on ICSI and IVF groups, and most were similar. Three of them had a medium risk of bias and remained 19 studies had low risk.

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the quality of included RCTs. Each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies (a) and methodological quality items (b)

Table 2.

Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale of included observational studies

| Study | Design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Summary score (risk of bias) | Final quality assessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||||

| Aboulghar et al. [29] | Prospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | a* | a* | b* | b | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Artini et al. [31] | Retrospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Biliangady et al. [32] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Boulet [33] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Eftekhar [35] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Fang et al. [14] | Retrospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Farhi et al. [15] | Retrospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Fernández et al. [36] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | d | b | a* | d | a* | a* | 5/9 (medium) | Intermediate quality |

| Grimstad et al. [37] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | d | b | a* | d | a* | a* | 5/9 (medium) | Intermediate quality |

| Hershlag [38] | Prospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | a* | a* | b* | a* | a* | 8/9 (low) | High quality |

| Jaroudi \[40] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Kim et al. [42] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Komsky-Elbaz et al. [21] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Ming [43] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Li et al. [24] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Liu et al. [44] | Retrospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Van der Westerlaken et al. [45] | Prospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | a* | a* | a* | a* | a* | 8/9 (low) | High quality |

| Schwarze et al. [46] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Shveiky et al. [13] | Retrospective cohort study | a* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Tannus et al. [47] | Retrospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | b | a* | b* | a* | a* | 7/9 (low) | High quality |

| Xi et al. [48] | Retrospective cohort study | b* | a* | a* | b | a* | d | a* | a* | 6/9 (medium) | Intermediate quality |

* meaned one star according to the NOS useing a ‘star‐based’ rating‐system and the studies scored from 0 to 9

Meta-analysis of fertilization rate

A total of 16 studies (4 RCTs and 12 cohort studies) evaluated the outcome of fertilization rate between the ICSI group and the IVF group. Subgroup analysis was performed based on study design (Fig. 3). The pooled outcome from 4 RCTs showed an increased fertilization rate in the ICSI group, but there was no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.83–1.62). Significant heterogeneity was observed within studies (I2 = 97%, P < 0.01). However, when the outcome was pooled for the cohort studies, there was a significant higher fertilization rate observed in the ICSI group (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.03–1.31). But, significant heterogeneity was observed within studies (I2 = 94%, P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of FR

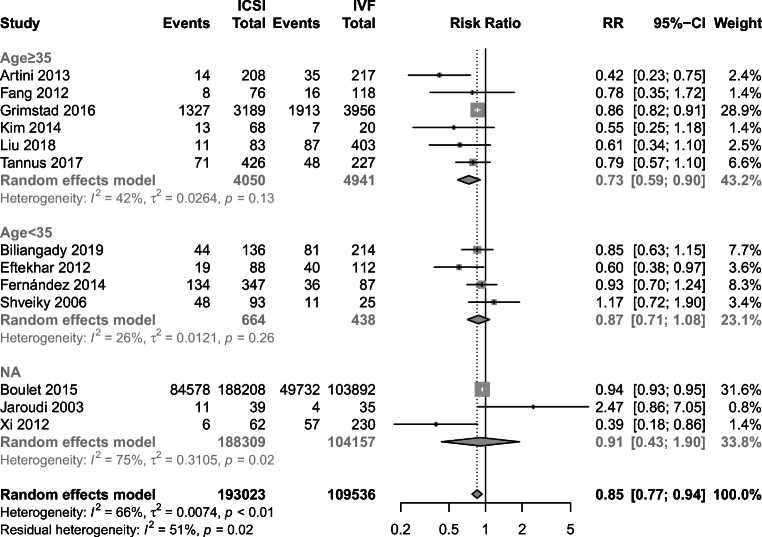

Meta-analysis of clinical pregnancy rate

Two RCTs and 13 cohort studies evaluated the outcome of the clinical pregnancy rate. Pooled analysis from cohort studies showed that IVF had an advantage in the clinical pregnancy rate than ICSI (RR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.77–0.94) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, substantial heterogeneity was observed in cohort studies (I2 = 66%, P < 0.01) and further subgroup analysis showed that CPR was higher in the IVF group among female age 35 and older (RR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.59–0.90), while there was no difference of CPR in female aged under 35 between two groups (RR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.71–1.08). Women with age data not available were included in the third subgroup. Despite there was no difference observed in CPR (RR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.43–1.90), high heterogeneity existed in these data (I2 = 75%, P = 0.02) (Fig. 5). However, when the outcome was pooled for 2 RCTs, no significant difference was observed (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.66–1.64) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of CPR

Fig. 5.

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of CPR according to age

Meta-analysis of implantation rate

Eight cohort studies and 1 RCT provided implantation rate data and were included in this meta-analysis [13, 29, 31–33, 36, 42, 44, 48]. The analysis of the single RCT revealed that there was no difference in implantation rate between the IVF group and the ICSI group (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 0.67–1.86). The pooled results of cohort studies suggested implantation rate was significantly higher in the IVF group. But, moderate heterogeneity was found among the cohort studies (I2 = 58%, P = 0.02) (Fig. 6). Subgroup analysis according to female age demonstrated that IR was significantly higher in the IVF group among female aged 35 and older (RR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.36–0.74); nevertheless, the advantage was not observed in another subgroup where women aged under 35 (RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.77–1.12). No heterogeneity was found in both these subgroups (I2 = 0%, P = 0.89; I2 = 0%, P = 0.46). In addition, women with age data not available were included in the third subgroup; high heterogeneity was observed in these data set (I2 = 82%, P = 0.02) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of IR

Fig. 7.

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of IR according to age

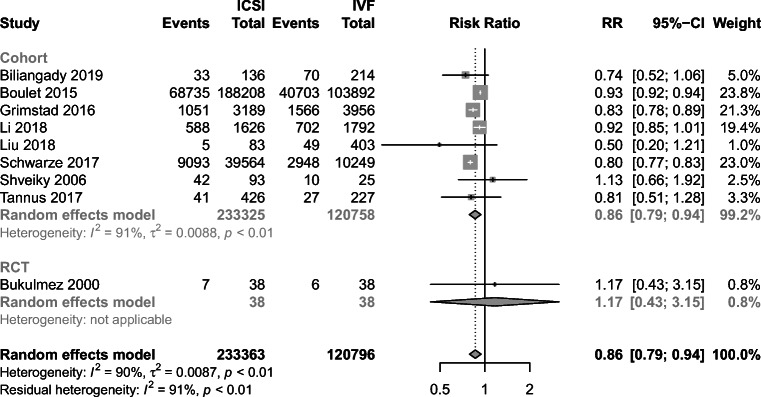

Meta-analysis of live birth rate

Nine studies included in the analysis provided live birth rate data (1 RCT and 8 cohort studies) [13, 24, 32–34, 37, 44, 47, 46]. There was only one RCT showed LBR data and no significant difference was observed between the groups (RR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.43–3.15). However, pooled results from 8 cohort studies demonstrated LBR was significantly higher in the IVF group (RR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.79–0.94) (Fig. 8). Meanwhile, high heterogeneity was noted among these studies (I2 = 91%, P < 0.01). Further subgroup analysis according to female age (< 35, ≥ 35) demonstrated that not only was the LBR significantly higher in the IVF group (RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.92–0.94; RR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.83) but also the heterogeneities were not detected in both groups (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54; I2 = 0%, P = 0.49) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of LBR

Fig. 9.

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of LBR according to age

Meta-analysis of miscarriage rate

Seven cohort studies provided miscarriage rate data and were included in the analysis [31–33, 36, 42, 44, 48]. No heterogeneity was noted among these studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.48). Pooled results revealed the miscarriage rate was higher in the ICSI group than the IVF group (pooled RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Forest plot of studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of MR

Meta-analysis of good-quality embryo rate

Four cohort studies reported the good-quality embryo rate [14, 31, 42, 43]. The overall effect estimate demonstrated that ICSI did not significantly increase the rate of the good-quality embryo than IVF (RR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.93–1.04) (Fig. 11). Low heterogeneity significant was observed (I2 = 13%, P = 0.33).

Fig. 11.

Forest plot of studies of ICSI group versus IVF group for the outcome of good-quality embryo rate

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken with each study removed in turn for outcomes to determine whether the conclusions were robust to the arbitrary decision made regarding the eligibility and analysis of the studies (Tables 2 and 3). The outcomes of CPR, IR, LBR, and good-quality embryo rate did not vary markedly with the removal of any one study, demonstrating that the meta-analysis was robust, and the results were not overly influenced by any study. However, the outcome of FR and the miscarriage rate was not robust. A total of four included RCTs reported fertilization rate, after removing one of them [29]; the fertilization rate was statistically higher in the ICSI group (RR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.06–1.62, P = 0.011), which was similar to the pooled results of cohort studies. In cohort studies, the result was not robust neither. Contrary to previous pooled results from cohort studies, removing the study conducted in 2005 [45] can lead to a different result, which demonstrated that there was no difference in FR between the two groups (RR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.98–1.22, P = 0.097). There were seven cohort studies included to draw the result of the miscarriage rate. But, five of them can influence the final results [31, 33, 42, 44, 48] and give rise to no statistical difference (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.91–1.21, P = 0.549; RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.91–1.19, P = 0.574; RR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.93–1.15, P = 0.548; RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.89–1.22, P = 0.612).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses

| Outcome | Study | RR | 95% CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Fertilization rate | RCTs | Aboulghar et al. [29] | 1.31 | 1.06 | 1.62 | 0.011 |

| Hwang et al. [39] | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.38 | 0.767 | ||

| Khamsi et al. [41] | 1.13 | 0.73 | 1.76 | 0.572 | ||

| Yang et al. [49] | 1.17 | 0.76 | 1.80 | 0.469 | ||

| Cohorts | Aboulghar et al. [30] | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.34 | 0.011 | |

| Artini et al. [31] | 1.20 | 1.05 | 1.37 | 0.008 | ||

| Fang et al. [14] | 1.15 | 1.02 | 1.30 | 0.028 | ||

| Farhi et al. [15] | 1.14 | 1.01 | 1.29 | 0.034 | ||

| Hershlag [38] | 1.14 | 1.01 | 1.29 | 0.030 | ||

| Jaroudi et al. [33] | 1.17 | 1.02 | 1.33 | 0.022 | ||

| Kim et al. [42] | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.36 | 0.016 | ||

| Ming et al. [43] | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.33 | 0.001 | ||

| Liu et al. [44] | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.35 | 0.017 | ||

| Shveiky et al. [13] | 1.19 | 1.04 | 1.35 | 0.012 | ||

| Van der Westerlaken et al. [45] | 1.10 | 0.98 | 1.22 | 0.097 | ||

| Xi et al. [48] | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.32 | 0.022 | ||

| Clinical pregnancy rate | RCTs | Aboulghar et al. [29] | 1.00 | 0.42 | 2.39 | 1.000 |

| Bukulmez et al. [34] | 1.06 | 0.62 | 1.80 | 0.842 | ||

| Cohorts | Artini et al. [31] | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.002 | |

| Biliangady et al. [32] | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.002 | ||

| Boulet et al. [33] | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.003 | ||

| Eftekhar 2012 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.002 | ||

| Fang et al. [14] | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.001 | ||

| Fernández et al. [36] | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.93 | < 0.001 | ||

| Grimstad et al. [37] | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.008 | ||

| Jaroudi [40] | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.93 | < 0.001 | ||

| Kim et al. [42] | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.002 | ||

| Liu et al. [44] | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.002 | ||

| Shveiky et al. [13] | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.93 | < 0.001 | ||

| Tannus et al. [47] | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.002 | ||

| Xi et al. [48] | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.002 | ||

| Implantation rate | Cohorts | Artini et al. [31] | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.042 |

| Biliangady et al. [32] | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.96 | 0.021 | ||

| Boulet 2015 [33] | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.014 | ||

| Fernández et al. [36] | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 0.006 | ||

| Kim et al. [42] | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.97 | 0.023 | ||

| Liu et al. [44] | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.99 | 0.037 | ||

| Shveiky et al. [13] | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.94 | 0.011 | ||

| Xi et al. [48] | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0.033 | ||

| Live birth rate | Cohorts | Biliangady et al. [32] | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.003 |

| Boulet [33] | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.90 | < 0.001 | ||

| Grimstad et al. [37] | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 0.009 | ||

| Li et al. [24] | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.002 | ||

| Liu et al. [44] | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.002 | ||

| Schwarze et al. [46] | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.001 | ||

| Shveiky et al. [13] | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.94 | < 0.001 | ||

| Tannus et al. [47] | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.002 | ||

| Miscarriage rate | Cohorts | Artini et al. [31] | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.21 | 0.549 |

| Biliangady et al. [32] | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.005 | ||

| Boulet 2015 [33] | 1.07 | 0.74 | 1.54 | 0.737 | ||

| Fernández et al. [36] | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.003 | ||

| Kim et al. [42] | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 0.574 | ||

| Liu et al. [44] | 1.03 | 0.93 | 1.15 | 0.548 | ||

| Xi et al. [48] | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.22 | 0.612 | ||

| Good-quality embryo rate | Cohorts | Artini et al. [31] | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.837 |

| Fang et al. [14] | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.959 | ||

| Kim et al. [42] | 0.97 | 0.90 | 1.05 | 0.478 | ||

| Ming et al. 2015 [43] | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 0.099 | ||

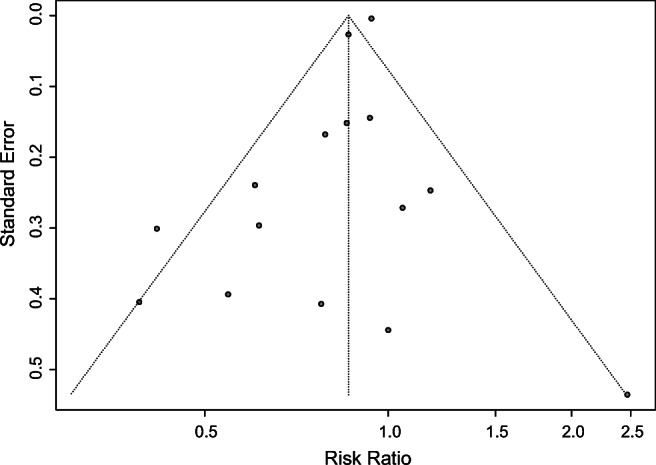

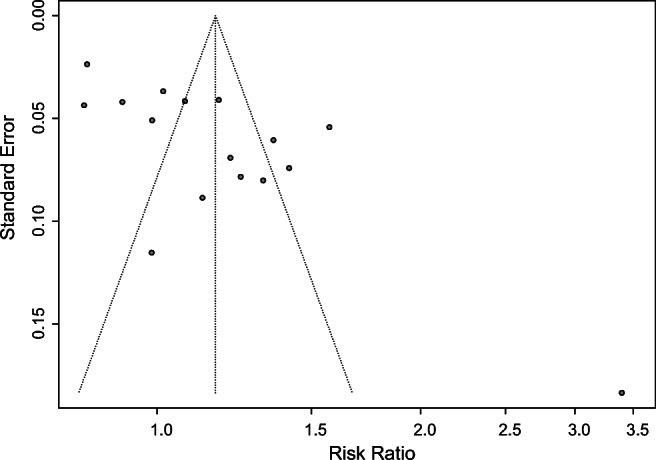

Assessment of publication bias

When 10 or more studies were included in one analysis, the funnel plot was constructed to examine possible publication bias with Egger’s test [28]. So, we only assessed the publication bias of outcomes regarding CPR and FR in this study. The funnel plot was symmetric for the outcome of CPR and Egger’s test did not suggest statistical significance (P = 0.0581) (Fig. 12), but the funnel plot was asymmetry for the outcome of FR, and Egger’s test showed statistical significance (P = 0.0018) (Fig. 13), indicating there was publication bias of included studies.

Fig. 12.

Funnel plot for CPR

Fig. 13.

Funnel plot for FR

Discussion

Primary outcomes

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate whether ICSI improves clinical outcomes in couples with non-male factor indications. Our inclusion criteria were infertility couples in the presence of normal semen parameters, which distinguishes this study from the previous meta-analysis that included patients with broad line semen as well as mild factor infertility. The results of our study did not show ICSI yields a better clinical outcome than IVF in couples with non-male factor.

Due to clinical or methodological heterogeneity, RCTs were analyzed separately from cohort studies. We failed to pool consistent results from RCTs and cohort studies in this study. Although some RCTs examining the effectiveness of ICSI in non-male factor infertility patients, results from currently available cohort studies indicate there is no advantage of ICSI over IVF as an insemination method for non-male factor infertility [25]. A Cochrane review including only one randomized control study even demonstrated IVF had a benefit in fertilization rate than ICSI [50]. Our results indicate that there were no statistically significant differences in fertilization rate (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.83–1.62) between two groups in 4 RCTs; however, a statistically significant higher fertilization rate (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.03–1.31) in the ICSI group was observed in cohort studies. Significant heterogeneities were observed in both subgroups (I2 = 97%, P < 0.01, I2 = 94%, P < 0.01). The previous prospective clinical trial suggested that the fertilization rate reduced consequently with maternal age increased [51]; the heterogeneity may come from age, racial, and ethnic differences; different protocols of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH); different supplements in culture medium; different duration of studies; and different experimental designs. Moreover, both the results from RCTs and cohort studies were not robust as previously mentioned. It suggests that there are important and potential bias factors related to the effect, and the results must be interpreted cautiously.

Contrary to popular belief, our results indicated that IVF may be beneficial to improve clinical outcomes in non-male factor infertility. Both clinical pregnancy rate (RR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.77–0.94) and implantation rate (RR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.65–0.95) were significantly higher in the IVF group in cohort studies. Further subgroup analysis according to the female age demonstrated that ICSI had disadvantages in both CPR and IR among females aged 35 and over (RR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.59–0.90; RR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.36–0.74). Nevertheless, the disadvantage was not observed among women aged under 35 (RR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.71–1.08; RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.77–1.12). Moreover, women with age data not available were included in the third subgroup; high heterogeneities were observed in these data sets (I2 = 75%, P = 0.02; I2 = 82%, P = 0.02). Therefore, we have reason to suspect that age was probably a major reason for existing heterogeneity and may be an important factor that affecting CPR and IR between these two groups. In spite of there was a study favored the use of ICSI in the older IVF population [52], the findings of our study are consistent with the results of previous studies showing that patients with advanced age presented declined pregnancy rate and implantation rate [53–55]. ICSI may yield worse reproductive outcomes in terms of pregnancy rate and implantation rate when the patient’s age is advanced. Sunderam et.al suggested a similar result that advanced age alone may not be a good indication for the use of ICSI, although it was increasingly implemented in older women worldwide [17, 56]. In addition, it suggested that advanced paternal age was associated with a significant increase in the prevalence of both genomic and epigenomic sperm defects [57]. Endometrial receptivity and embryo quality are two critical factors that affect the implantation rate and pregnancy rate. Conventional ICSI is associated with mechanical damage to the oocyte during the conventional ICSI procedure; laser-assisted ICSI is introduced to overcome this problem [58]. A previous study showed that it led to improved embryonic development and clinical outcomes; moreover, the pregnancy rate was increased in older patients especially [59]. In our results, ICSI was associated with lower CPR and IR among female aged 35 and over; these results might be attributed to that oocytes from women with advanced age maybe more venerable to mechanical damage, leading to impaired embryonic development and disadvantageous clinical outcomes.

A clinician may split sibling oocytes into different insemination methods or assign eligible couples in IVF or ICSI treatment cycle when conducted studies on this subject. In the former study design, the embryos are often mixed together to transfer in order to obtain a better clinical effect. It is not possible to extra data like clinical pregnancy rate, implantation rate, and other data that were based on the individual patient. In addition, rescue-ICSI may be applicable for unfertilized oocytes in conventional IVF to prevent total fertilization failure and that may have an effect on clinical outcomes, even though the authors did not mention that in their studies. More importantly, the patient groups are often small; it is difficult to conduct an RCT to assign eligible couples in IVF or ICSI treatment due to ethical considerations. Although more and more scholars pay attention to the effectiveness of ICSI in non-male factor infertility, only 15 studies (2 RCTs and 13 cohort studies) and 9 (1 RCTs and 8 cohort studies) of all included studies provided data of CPR and IR. Therefore, more well-designed RCTs are required for further evaluating the indications of ICSI in non-male factor patients.

Secondary outcomes

Pooled results from cohort studies demonstrated LBR was significantly higher in the IVF group (RR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.79–0.94). High heterogeneity was noted among these studies (I2 = 91%, P < 0.01). Further subgroup analysis according to female age (< 35, ≥ 35) demonstrated that not only was the LBR significantly higher in the IVF group (RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.92–0.94; RR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.83) but also the heterogeneities were not detected in both groups (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54; I2 = 0%, P = 0.49). It indicated that age was the main factor of existing heterogeneity. We failed to draw consistent results from the single RCT which suggested there was no difference between two groups regarding live birth rate in the treatment of non-male factor infertility (RR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.43–3.15). This finding is relatively consistent with the previous meta-analysis based on 4 RCTs [60]. It is undeniable the design and methodological differences existing between RCTs and cohort studies may be a potential cause of the divergence.

Our results revealed MR was higher in the ICSI group than the IVF group (pooled RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06). Chromosome abnormality, thrombophilia, metabolic disorders, anatomical causes, and immune factor are all important factors that can give rise to miscarriage. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate MR in ICSI treatment of non-male factor infertility. Unfortunately, the result was not robust as previously mentioned that five of the included studies could influence the pooled results. As mentioned before, there were only 7 cohort studies were included in this part; no RCTs reported the miscarriage rate between two group; it is difficult to conduct an RCT to assign eligible couples into two treatment groups due to ethical and clinical effects; further well-designed, multi-center RCTs regarding the effect of ICSI for patients without male factor are warranted.

Limitations

The main limitation of this systematic review and meta-analysis was the different study designs of the included studies. In addition, we failed to draw consistent results between cohort studies and RCTs; the results may be due to systematic differences rather than intervention effects. In addition, there was publication bias in the studies providing FR data; these may due to omitting studies or unpublished literature; besides, studies pooling results positively tended to be published. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. More well-designed RCTs and robust data are warranted to confirm the findings because the primarily included studies are observational studies.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of our meta-analysis did not show ICSI yields a better clinical outcome than IVF in couples with non-male factor. At present, there is little evidence to support the routine use of ICSI as a treatment for non-male factor infertility. Further researches especially well-designed RCTs are needed to investigate whether ICSI can improve outcomes according to variant factors like age and etiology of infertility.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 13 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance of Dr. Yonghong Wang of Chongqing Medical University in picture processing.

Authors’ contributions

T.G.: study design, data collection and analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript; L.C.: data collection and analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript; C.G.; data collection and analysis, revised the manuscript; Y.Z.; revised the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Code availability

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Palermo G, et al. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet. 1992;340(8810):17–18. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil-Salom M, et al. Testicular sperm extraction and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a chance of fertility in nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol. 1998;160(6):2063–2067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollingsworth B, Harris A, Mortimer D. The cost effectiveness of intracyctoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007;24(12):571–577. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9175-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ola B, Afnan M, Sharif K, Papaioannou S, Hammadieh N, L.R.Barratt C. Should ICSI be the treatment of choice for all cases of in-vitro conception? Considerations of fertilization and embryo development, cost ffectiveness and safety. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(12):2485–2490. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palermo GD, Neri QV, Rosenwaks Z. To ICSI or not to ICSI. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33(2):92–102. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1546825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacamara C, Ortega C, Villa S, Pommer R, Schwarze JE. Are children born from singleton pregnancies conceived by ICSI at increased risk for congenital malformations when compared to children conceived naturally? A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2017;21(3):251–259. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20170047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massaro PA, MacLellan DL, Anderson PA, Romao RLP. Does intracytoplasmic sperm injection pose an increased risk of genitourinary congenital malformations in offspring compared to in vitro fertilization? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2015;193(5):1837–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe H. Risk of chromosomal aberration in spermatozoa during intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Reprod Dev. 2018;64(5):371–376. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2018-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ooki S. Birth defects after assisted reproductive technology according to the method of treatment in Japan: nationwide data between 2004 and 2012. Environ Health Prev Med. 2015;20(6):460–465. doi: 10.1007/s12199-015-0486-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sfontouris IA, Kolibianakis EM, Lainas GT, Navaratnarajah R, Tarlatzis BC, Lainas TG. Live birth rates using conventional in vitro fertilization compared to intracytoplasmic sperm injection in Bologna poor responders with a single oocyte retrieved. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32(5):691–697. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0459-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gennarelli G, et al. ICSI versus conventional IVF in women aged 40 years or more and unexplained infertility: a retrospective evaluation of 685 cycles with propensity score model. J Clin Med. 2019:8(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Omland AK, Bjercke S, Ertzeid G, Fedorcsák P, Oldereid NB, Storeng R, Åbyholm T, Tanbo T. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in unexplained and stage I endometriosis-associated infertility after fertilization failure with in vitro fertilization (IVF) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006;23(7–8):351–357. doi: 10.1007/s10815-006-9060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shveiky D, Simon A, Gino H, Safran A, Lewin A, Reubinoff B, Laufer N, Revel A. Sibling oocyte submission to IVF and ICSI in unexplained infertility patients: a potential assay for gamete quality. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;12(3):371–374. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang C, Tang J, Huang R, Li LL, Zhang MF, Liang XY. Comparison of IVF outcomes using conventional insemination and ICSI in ovarian cycles in which only one or two oocytes are obtained. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de La Reproduction. 2012;41(7):650–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhi J, Cohen K, Mizrachi Y, Weissman A, Raziel A, Orvieto R. Should ICSI be implemented during IVF to all advanced-age patients with non-male factor subfertility? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0474-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive, M. and a.a.o. the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Electronic address, Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) for non-male factor indications: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(2):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulet SL, Mehta A, Kissin DM, Warner L, Kawwass JF, Jamieson DJ. Trends in use of and reproductive outcomes associated with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2015;70(5):325–326. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford GE, Ledger WL. In vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic sperm injection beyond 2020. Bjog-an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2019;126(2):237–243. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieke AC, Mehta A, Kissin DM, Nangia AK, Warner L, Boulet SL. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection use in states with and without insurance coverage mandates for infertility treatment, United States, 2000-2015. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(4):691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azem F, Bernholtz O, Kapustiansky R, Wagman I, Lessing JB, Amit A. A comparison between the outcome of conventional IVF and ICSI in sibling oocytes among couples with unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S189. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komsky-Elbaz A, Raziel A, Friedler S, Strassburger D, Kasterstein E, Komarovsky D, et al. Conventional IVF versus ICSI in sibling oocytes from couples with endometriosis and normozoospermic semen. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(2):251–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Choi DH, et al. Half-ICSI: an insemination method to prevent first cycle fertilization failure or low fertilization. 84(supp-S1).

- 23.Supramaniam PR, Granne I, Ohuma EO, Lim LN, McVeigh E, Venkatakrishnan R, Becker CM, Mittal M. ICSI does not improve reproductive outcomes in autologous ovarian response cycles with non-male factor subfertility. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(3):583–594. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Wang AY, Bowman M, Hammarberg K, Farquhar C, Johnson L, Safi N, Sullivan EA. ICSI does not increase the cumulative live birth rate in non-male factor infertility. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(7):1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drakopoulos P, Garcia-Velasco J, Bosch E, Blockeel C, de Vos M, Santos-Ribeiro S, Makrigiannakis A, Tournaye H, Polyzos NP. ICSI does not offer any benefit over conventional IVF across different ovarian response categories in non-male factor infertility: a European multicenter analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36(10):2067–2076. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01563-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells, G. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. in Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics. 2000.

- 27.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT, Serour GI, Amin YM, Kamal A. Prospective controlled randomized study of in vitro fertilization versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the treatment of tubal factor infertility with normal semen parameters. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(5):753–756. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT, Serour GI, Sattar MA, Amin YM. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection and conventional in vitro fertilization for sibling oocytes in cases of unexplained infertility and borderline semen. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;(1):38–42. 10.1007/BF02068867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Artini PG, Obino MER, Carletti E, Pinelli S, Ruggiero M, di Emidio G, Cela V, Tatone C. Conventional IVF as a laboratory strategy to rescue fertility potential in severe poor responder patients: the impact of reproductive aging. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):997–1001. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2013.822063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biliangady R, Kinila P, Pandit R, Tudu NK, Sundhararaj UM, Gopal IST, Swamy AG. Are we justified doing routine intracytoplasmic sperm injection in nonmale factor infertility? A retrospective study comparing reproductive outcomes between in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in nonmale factor infertility. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2019;12(3):210–215. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_8_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulet SL, Mehta A, Kissin DM, Warner L, Kawwass JF, Jamieson DJ. Trends in use of and reproductive outcomes associated with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. JAMA. 2015;313(3):255–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bukulmez O, Yarali H, Yucel A, Sari T, Gurgan T. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection versus in vitro fertilization for patients with a tubal factor as their sole cause of infertility: a prospective, randomized trial. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(1):38–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Eftekhar M, Mohammadian F, Yousefnejad F, Molaei B, Aflatoonian A. Comparison of conventional IVF versus ICSI in non-male factor, normoresponder patients. Iran J Reprod Med. 2012;10(2):131–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Fernández RM, Barragán MA, Cabañes Martínez I, Fernandez CL, Grassa LH, Sepúlveda CB, Basile N, Bronet Campos F. ICSI vs conventional IVF (cIVF) in women with low response (LR) and different age groups. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;28:S19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimstad FW, Nangia AK, Luke B, Stern JE, Mak W. Use of ICSI in IVF cycles in women with tubal ligation does not improve pregnancy or live birth rates. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2750–2755. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershlag A, Paine T, Kvapil G, Feng H, Napolitano B. In vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection split: an insemination method to prevent fertilization failure. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2):229–32. 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02978-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Hwang JL, Seow KM, Lin YH, Hsieh BC, Huang LW, Chen HJ, Huang SC, Chen CY, Chen PH, Tzeng CR. IVF versus ICSI in sibling oocytes from patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(5):1261-5. 10.1093/humrep/deh786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Jaroudi K, Al-Hassan S, Al-Sufayan H, Al-Mayman H, Qeba M, Coskun S. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection and conventional in vitro fertilization are complementary techniques in management of unexplained infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2003;20(9):377–81. 10.1023/a:1025433128518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Khamsi F, Yavas Y, Roberge S, Wong JC, Lacanna IC, Endman M. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection increased fertilization and good-quality embryo formation in patients with non-male factor indications for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(2):342–7. 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01674-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Kim JY, Kim JH, Jee BC, Lee JR, Suh CS, Kim SH. Can intracytoplasmic sperm injection prevent total fertilization failure and enhance embryo quality in patients with non-male factor infertility? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;178:188–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ming L, Yuan C, Ping Z, Ping L, Jie Q. Conventional in vitro fertilization maybe yields more available embryos than intracytoplasmic sperm injection for patients with no indications for ICSI. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):21593–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Liu H, Zhao H, Yu G, Li M, Ma S, Zhang H, Wu K. Conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI): which is preferred for advanced age patients with five or fewer oocytes retrieved? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(5):1301–1306. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Westerlaken L, Helmerhorst F, Dieben S, Naaktgeboren N. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection as a treatment for unexplained total fertilization failure or low fertilization after conventional in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(3):612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwarze J-E, et al. Is there a reason to perform ICSI in the absence of male factor? Lessons from the Latin American Registry of ART. Human Reproduction Open. 2017;2017(2):hox013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Tannus S, Son WY, Gilman A, Younes G, Shavit T, Dahan MH. The role of intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non-male factor infertility in advanced maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(1):119–124. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xi QS, Zhu LX, Hu J, Wu L, Zhang HW. Should few retrieved oocytes be as an indication for intracytoplasmic sperm injection? J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2012;13(9):717–722. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang D, Shahata MA, al-Bader M, al-Natsha SD, al-Flamerzia M, al-Shawaf T. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection improving embryo quality: comparison of the sibling oocytes of non-male-factor couples. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996 ;13(4):351–5. 10.1007/BF02070151. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.van Rumste MME, Evers JLH, Farquhar CM. ICSI versus conventional techniques for oocyte insemination during IVF in patients with non-male factor subfertility: a Cochrane review. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(2):223–227. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taheripanah R, et al. Does intracytoplasmic sperm injection overcome the reduce of fertilization rate by increasing maternal age? Journal of Reproduction & Infertility. 2000;1(1):24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farhi J, et al. Should ICSI be implemented during IVF to all advanced-age patients with non-male factor subfertility? Reproduct Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Gonzalez-Foruria I, et al. Age, independent from ovarian reserve status, is the main prognostic factor in natural cycle in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(2):342–U151. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang YA, Healy D, Black D, Sullivan EA. Age-specific success rate for women undertaking their first assisted reproduction technology treatment using their own oocytes in Australia, 2002-2005. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(7):1633–1638. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Kooij RJ, et al. Age-dependent decrease in embryo implantation rate after in vitro fertilization. Fertility and Sterility. 1996;66(5):769–775. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58634-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sunderam S, et al. Comparing fertilization rates from intracytoplasmic sperm injection to conventional in vitro fertilization among women of advanced age with non - male factor infertility: a meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility. 2020;113(2):354. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belloc S, Hazout A, Zini A, Merviel P, Cabry R, Chahine H, Copin H, Benkhalifa M. How to overcome male infertility after 40: influence of paternal age on fertility. Maturitas. 2014;78(1):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdelmassih S, et al. Laser-assisted ICSI: a novel approach to obtain higher oocyte survival and embryo quality rates. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2694–2699. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi KH, Lee JH, Yang YH, Yoon TK, Lee DR, Lee WS. Efficiency of laser-assisted intracytoplasmic sperm injection in a human assisted reproductive techniques program. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2011;38(3):148–152. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2011.38.3.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abbas AM, Hussein RS, Elsenity MA, Samaha II, el Etriby KA, Abd el-Ghany MF, Khalifa MA, Abdelrheem SS, Ahmed AA, Khodry MM. Higher clinical pregnancy rate with in-vitro fertilization versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection in treatment of non-male factor infertility: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49(6):101706. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.