Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to determine the role of Wnt pathway in mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC) derivation from single blastomeres isolated from eight-cell embryos and in the pluripotency features of the mESC established.

Methods

Wnt activator CHIR99021, Wnt inhibitor IWR-1-endo, and MEK inhibitor PD0325901 were used alone or in combination during ESC derivation and maintenance from single blastomeres biopsied from eight-cell embryos. Alkaline phosphatase activity, FGF5 levels, expression of key pluripotency genes, and chimera formation were assessed to determine the pluripotency state of the mESC lines.

Results

Derivation efficiencies were highest when combining pairs of inhibitors (15–24.7%) than when using single inhibitors or none (1.4–10.1%). Full naïve pluripotency was only achieved in CHIR- and 2i-treated mESC lines, whereas IWR and PD treatments or the absence of treatment resulted in co-existence of naïve-like and primed-like pluripotency features. IWR + CHIR- and IWR + PD-treated mESC displayed features of primed pluripotency, but IWR + CHIR-treated lines were able to generate germline-competent chimeric mice, resembling the predicted properties of formative pluripotency.

Conclusion

Wnt and MAPK pathways have a key role in the successful derivation and pluripotency features of mESC from single precompaction blastomeres. Modulation of these pathways results in mESC lines with various degrees of naïve-like and primed-like pluripotency features.

Keywords: Mouse embryonic stem cells, Single blastomeres, Wnt signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, Pluripotency state

Introduction

Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) can be derived and maintained in culture medium supplemented with fetal calf serum (FCS) [1, 2] or the more defined knockout serum replacement (KSR) [3], in the presence of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) [4, 5]. However, under these conditions, only embryos from permissive strains can successfully produce mESC lines. Moreover, while mESC lines cultured under these conditions are considered representatives of the naïve state of pluripotency, it is known that mESC grown in the presence of FCS + LIF form heterogeneous populations, containing different cell subtypes fluctuating between a naïve inner cell mass (ICM)-like state and a primed epiblast-like state, due to a variable stimulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway [6, 7]. The introduction, in 2008, of the MAPK kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD0325901 (PD) and the glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitor CHIR99021 (CHIR), a combination known as 2i, marked a breakthrough in the establishment of mESC lines [7], allowing the derivation of mESC lines from several refractory strains. Indeed, 2i, together with LIF, improves mESC derivation efficiency regardless of the genetic background of the embryos, even in serum-free medium [8]. Moreover, 2i + LIF maintains mESC as highly homogenous populations, transcriptionally similar to the epiblast of E4.5 embryos, and are thus referred to be in a naïve ground state of pluripotency [7, 9].

The excellent results obtained with 2i highlight the importance of signaling pathways in mESC derivation and pluripotency maintenance. By inhibiting the MAPK pathway, PD suppresses the differentiation signals and fosters long-term self-renewal of mESC when combined with LIF [7]. However, the sole inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway is insufficient to maintain mESC viability and results in apoptosis [7]. On the other hand, CHIR activates the Wnt signaling pathway, generating a cytosolic pool of β-CATENIN that can either form a membrane-associated complex together with E-CADHERIN and OCT4 [10] or move to the nucleus to activate the transcription of Wnt target genes [11, 12]. Some of these target genes, such as Oct4 and Nanog, are associated with pluripotency maintenance [13], whereas other genes, such as Frizzelds and Axin2, are pathway regulators [14]. Despite that the two routes are not mutually exclusive under ground state conditions, there is negligible transcriptional activity of Wnt-target genes and the membrane-associated complex has an essential role to maintain naïve pluripotency [10]. Although CHIR is usually combined with PD, it can also be used alone to maintain pluripotency in the presence of LIF [11]. Alternatively, CHIR can be combined with either XAV939 or IWR-1-endo (IWR), both preventing Wnt/β-catenin signaling through the stabilization of AXIN in the β-CATENIN destruction complex. The CHIR + IWR combination has been reported to maintain primed pluripotency in epiblast stem cell (EpiSC) lines [15]. Thus, Wnt pathway plays a key role in determining the state of pluripotency of mouse stem cells, since naïve pluripotency requires the activation of the canonical Wnt pathway whereas primed pluripotency is dependent on its inactivation [16].

Naïve and primed pluripotent states represent the distinct cellular identities of pre- and post-implantation epiblast cells [17]. Both states require the expression of the core pluripotency factors OCT4 and SOX2 to maintain pluripotency [6], but show a differential expression of specific markers, such as Klf2, Klf4, Nanog, Esrrb, Rex1, and Tfcpl21 for naïve pluripotency [18–20] and Fgf5, Eomes, Sox17, Otx2, and Dnmt3b for primed pluripotency [16, 21]. Moreover, naïve and primed pluripotent lines can be distinguished by the differential activation of the LIF/Stat3, Wnt/β-catenin and FGF/MEK pathways [22], DNA methylation levels [6], X-chromosome inactivation state [23], colony morphology [24], alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity [11], and contribution to chimera formation when injected into blastocysts [17]. In the last few years, the conventional two-stage model of pluripotency has been challenged by the description of cells in an intermediate state of pluripotency [25], recently designated as the formative pluripotency state [26]. This distinct state exists in the embryo at E5.5–6.25, when the naïve transcriptional program has been downregulated, but lineage-associated markers are not yet upregulated [27]. Predictive features of the formative pluripotent state, which has not yet been possible to be stably maintained in vitro, are low or null expression of both naïve pluripotency factors and lineage-specification factors but upregulation of early post-implantation factors (with a key role for Otx2), intermediate levels of DNA methylation, partial X chromosome inactivation, germ cell competence, and the ability to form blastocyst chimeras, among others [26].

Although mESC are normally derived from whole blastocysts, they can also be obtained from single blastomeres of precompaction embryos. While it is known that derivation efficiency from single blastomeres isolated from eight-cell stage embryos (1/8 blastomeres) is improved when using 2i [28, 29], the effect of other modulations of the Wnt and MAPK signaling pathways is unknown. Interestingly, 1/8 blastomeres are single uncommitted cells which retain the ability to originate both mESC and trophoblast stem cells [30], whereas cells from the preimplantation epiblast are more committed and present an expression pattern equivalent to that of mESC [9]. Therefore, differences between the commitment, and consequently, between the expression profile of 1/8 blastomeres and preimplantation epiblasts, could be determinant for their response to the modulators of signaling pathways.

In this scenario, this study aims to investigate the effect of several combinations of Wnt modulators and MAPK inhibitors on mESC derivation from 1/8 blastomeres and to explore the state of pluripotency of the mESC lines derived and maintained under different treatments.

Materials and methods

Embryo collection, culture, and biopsy

Embryos at the two-cell stage were collected from the oviducts of superovulated 129S2 females mated with C57BL males [29]. The embryos were cultured in KSOMaag medium (Zenith-Biotech) supplemented with 4 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) and covered with mineral oil (Sigma) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until they reached the eight-cell stage. The zona pellucida was then drilled using a 10-μm pipette containing acidic Tyrode’s solution, and all the blastomeres were individually aspirated with a 20-μm pipette containing PBS-1% BSA.

To avoid a bias due to embryo origin or a possible blastomere commitment, 1/8 blastomeres biopsied from different embryos were pooled and randomly distributed among the different experimental groups.

Stem cell derivation and culture

After the biopsy, 1/8 blastomeres were cultured in 50-μl microdrops of derivation medium containing a monolayer of mitomycin C-inactivated human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) and covered with mineral oil. The derivation medium consisted of DMEM (BioWest) supplemented with 20% KSR (Life technologies), 100 μM 2-β mercaptoethanol (Gibco), 1× non-essential amino acids (Gibco), 103 U/ml LIF (Merk Millipore), 0.1 mg/ml adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; Prospec), and 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco).

When indicated, the following small-molecule inhibitors were added, alone or combined, to the derivation medium: 3 μM CHIR99021 (CHIR; Axon Medchem), 2.5 μM IWR-1-endo (IWR; Stem Cell Techonologies), or 1 μM PD0325901 (PD; Axon Medchem). Specifically, a total of six different treatment groups were performed: CHIR alone, IWR alone, PD alone, IWR + CHIR, IWR + PD, and CHIR + PD (2i). In addition, a control group without treatment (NT) was included. A minimum of 140 blastomeres were seeded for each treatment.

After the first passage, outgrowths were cultured in 4-well plates in the same medium without ACTH. Putative mESC lines were subcultured once a week and maintained in culture for at least 6 weeks.

Table 1 summarizes the different treatments performed during the derivation and culture of mESC and indicates the number of lines per treatment used for the different analyses described below.

Table 1.

Treatments and media used for the derivation of mESC lines from single 1/8 blastomeres and number of mESC lines from each group used for the various analyses performed

| Derivation medium | Treatment group | Number of lines used for analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunodetection OCT4, SOX2, TUJ1, αSMA, AFP | Immunodetection and quantification | Quantification of Axin2 expression (qPCR) | Quantification ALP activity | Quantification of Oct4, Nanog, Rex1, Esrrb, Tfcp2l1, Otx2, Dnmt3b expression (qPCR) | Chimera analysis | |||

| AXIN2, FGF5 | E-CAD, β-CAT | |||||||

| KSR | NT | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| IWR | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | - | |

| CHIR | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | - | - | |

| PD | 14 | 4 | - | 2 | 3 | - | - | |

| IWR + CHIR | 21 | 4 | - | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| IWR + PD | 31 | 4 | - | 2 | 3 | - | - | |

| 2i (CHIR + PD) | 45 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| N2B27 | IWR + CHIR | 5 | 3a | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2i (CHIR + PD) | 3 | 3a | - | - | - | - | - | |

E-CAD E-CADHERIN, β-CAT β-CATENIN

aIn these lines, only FGF5 was analyzed

Stem cell characterization by immunofluorescence

Putative mESC lines were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence analysis according to previously described methods [29]. Primary antibodies against OCT4 (Santa Cruz, ref. Sc-5279, 1:50 dilution) and SOX2 (Merck Millipore, ref. AB5603, 1:200 dilution) were used for pluripotency analysis. The ectoderm marker TUBULIN β 3 (TUJ1; Biolegend, ref. MMS-435P, 1:500 dilution), the mesoderm marker α SMOOTH MUSCLE ACTIN (αSMA; Sigma, ref. A5228, 1:200 dilution), and the endoderm marker ALPHA-FETOPROTEIN (AFP; R&D Systems, ref. MAB1368, 1:50 dilution) were assessed after inducing mESC spontaneous differentiation by culturing the cells for 10 days in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS without feeder cells. Lines positive for all the aforementioned pluripotency and differentiation markers were considered authentic mESC lines and used for further analyses. Primary antibodies against AXIN2 (Abcam; ab109301; 1:100 dilution), E-CADHERIN (Sigma; U3254; 1:500 dilution), β-CATENIN (BD transduction laboratories, 610154; 1:100 dilution), and FGF5 (Abcam; ab88118; 1:200 dilution) were used to further characterize mESC lines. Secondary antibodies were anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes - Invitrogen, ref. A-21200, 1:500 dilution) for OCT4, TUJ1, αSMA, AFP and β-CATENIN, and anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes - Invitrogen, ref. A-11037, 1:500 dilution) for SOX2, AXIN2 and FGF5, and anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes – Invitrogen, ref. A-1107, 1:500 dilution) for E-CADHERIN. Samples were analyzed with an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61) and the Cytovision software (Applied Imaging, Inc).

Quantification of immunofluorescence signals

To quantify AXIN2, FGF5, E-CADHERIN, and β-CATENIN, the fluorescence intensity of the markers was assessed after simultaneously immunostaining mESC lines from each group and capturing the corresponding images under the same conditions. Then, using ImageJ software, an outline was drawn around each mESC colony to measure its area, mean fluorescence, and integrated density. Fluorescence intensity of the background was also measured. The corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) was calculated for each colony: CTCF = integrated density − (area of the colony × mean fluorescence of the background readings) [31].

The number of mESC lines used in these analyses is detailed in Table 1, and the total number of colonies analyzed per treatment was 8–20 for AXIN2 (4–7 colonies per line), 9–15 for FGF5 (2–5 colonies per line), and 20–22 for β-CATENIN and E-CADHERIN (10–11 colonies per line).

Quantification of alkaline phosphatase activity

Colonies of mESC were picked to separate these cells from the feeder cells. After freezing the samples at −80 °C, pellets of mESC colonies and feeder cells were separately lysed using ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors for 10 min. Then, samples were vortexed for 10 s and sonicated at 25% amplitude for 15 s, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rcf for 2 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was recovered to evaluate ALP activity by quantifying p-nitrophenol produced by the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP). To do so, the supernatant was mixed at 1:1 ratio with 1-step pNPP (ThermoScientific). The mixture was incubated for 30 min at RT protected from light, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a VICTOR3 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer). To normalize ALP activity, total protein content was assessed with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (ThermoScientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In these analyses, two to three mESC lines were used per treatment (Table 1) and all samples were assayed in triplicate.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

The expression of Axin2 was assessed by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in mESC lines from all treatment groups. The expression of Oct4, Nanog, Rex1, Esrrb, Tfcp2l1, Otx2, and Dnmt3b was assessed only in mESC lines from the NT, 2i, and IWR + CHIR groups, and STO mouse fibroblasts were used as a negative control. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed as previously reported [29]. Validated PrimePCR SYBR Green Assays (Bio-Rad) for Axin2 (qMmuCED0044828), Oct4 (Pou5f1, qMmuCED0046525), Rex1 (Zfp42, qMmuCID0008767), Nanog (qMmuCID0005399), Esrrb (qMmuCED0039638), Tfcp2l1 (qMmuCID0013329), Otx2 (qMmuCID0023948), and Dnmt3b (qMmuCID0019749) were used to assess pluripotency and its state, and Gapdh (qMmuCED0027497) was used to normalize gene expression between samples. All samples were assayed in triplicate and a no template control was added for each primer. The cycle quantification value (Cq value) was determined for each sample with the BioRad CFX Maestro™ Software.

Chimera analysis

The ability to form chimeras and contribute to the germline was tested in mESC of the NT, 2i, and IWR + CHIR groups. From each treatment, one line was randomly selected. After confirming their gender by PCR [32] and analyzing their modal karyotype [33], 12 to 18 mES cells were injected into C57BL6 host embryos at the blastocyst stage. Injected embryos were cultured in KSOM (Millipore) for 1–2 h and transferred into the uteri of ICR females, previously mated with ICR vasectomized males, at 2.5 days of pseudopregnancy. Chimeric pups were identified by coat color mosaicism and validated for germline transmission by mating with wild-type mice.

Statistical analysis

The number of outgrowths formed after 8 days of culture, of non-progressive outgrowths after the second passage, and of confirmed mESC lines was calculated. Results were analyzed with χ2 and Fisher exact test.

CTCF values for AXIN2, FGF5, β-CATENIN, and E-CADHERIN were first analyzed with the Shapiro-Wilk test to check for the normality of the samples. Then, CTCF values from all groups were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test in the case of AXIN2, β-CATENIN, and E-CADHERIN quantification and one-way ANOVA followed with Tukey’s post hoc test in the case of FGF5 quantification. Alternatively, CTCF values of FGF5 from colonies derived in a medium containing N2B27 were analyzed with a Mann-Whitney test.

Regarding the quantification of ALP activity, after the results of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test.

In the case of qPCR, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed with Tukey’s post hoc test.

All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software, except for the results of qPCRs that were analyzed with the BioRad CFX Maestro™ Software. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Derivation of mESC in the presence of signaling modulators

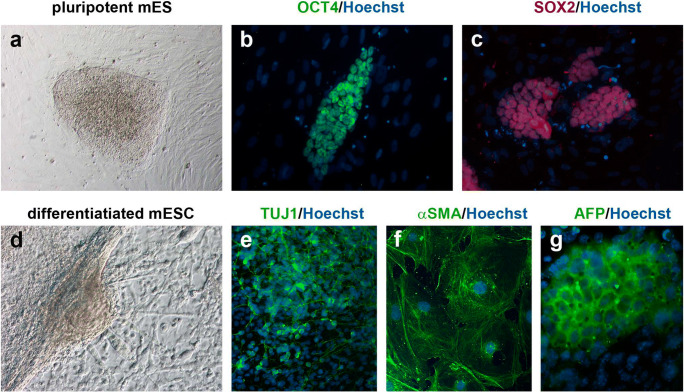

Mouse ESC lines were derived from 1/8 blastomeres in the presence of CHIR, IWR, PD, IWR + CHIR, IWR + PD, or CHIR + PD (2i) or without treatment (NT). After the sixth passage, putative mESC lines that presented colonies with a stem cell-like morphology were assessed for pluripotency using immunofluorescence analysis. The differentiation potential of the putative mESC lines was also assessed by immunofluorescence after inducing their spontaneous differentiation. According to these immunofluorescence analyses, the 127 lines obtained and analyzed were validated as mESC (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence detection of pluripotency and differentiation markers in mESC lines derived from 1/8 blastomeres. a Colony of a putative mESC line cultured for six passages, showing stem cell-like morphology and defined edges. b, c mESC colonies expressing the pluripotency markers OCT4 (green, b) and SOX2 (red, c). d Morphology of a differentiated mESC colony after 10 days of inducing its spontaneous differentiation. e, f, g Differentiated mESC colonies expressing TUJ1 (green, e), αSMA (green, f), and AFP (green, g). In all the immunofluorescence images, nuclear material is counterstained with Hoechst (blue). All the scale bars represent 100 μm

Treatment with CHIR produced the highest number of outgrowths after 8 days of culture (50.3%; Table 2). However, as in the NT and IWR groups, most of these outgrowths degenerated during the second passage, resulting in very low derivation efficiencies (1.4–4.9%, Table 2). On the contrary, although the number of outgrowths in the PD group was lower (15.2%) than in the CHIR group, because most of them survived and progressed after the second passage, mESC derivation rates (10.1%; Table 2) turned out to be significantly higher than for CHIR- and IWR-treated groups.

Table 2.

Outgrowth formation and derivation efficiencies of mESC lines established from single 1/8 blastomeres treated with different small-molecule modulators

| Treatment group | Blastomeres (n) | Outgrowths formation (%) | Non-progressive outgrowths (%) | mESC lines (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | 185 | 43 (23.2%)a, d | 34 (79.1%)a | 9 (4.9%)a,b |

| IWR | 139 | 19 (13.7%)b | 17 (89.5%)a,b | 2 (1.4%)a |

| CHIR | 153 | 77 (50.3%)c | 72 (93.5%)b | 5 (3.3%)a |

| PD | 138 | 21 (15.2%)a,b | 7 (33.3%)c | 14 (10.1%)b,c |

| IWR + CHIR | 140 | 32 (22.9%)a,b,d | 11 (34.4%)c | 21 (15.0%)c,d |

| IWR + PD | 157 | 38 (24.2%)a,d | 7 (18.4%)c | 31 (19.7%)d,e |

| 2i (CHIR + PD) | 182 | 56 (30.7%)d | 11 (19.6%)c | 45 (24.7%)e |

a–eDifferent lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatment groups for each parameter analyzed: outgrowth formation, non-progressive outgrowths, or derivation efficiencies.

When the inhibitors were combined, the percentage of non-progressive outgrowths was lower (18.4–34.4%), and the resulting efficiencies of mESC derivation were higher than those of the NT, IWR, and CHIR groups, irrespectively of the combination of inhibitors used (Table 2). Combined treatments with IWR + PD and 2i produced the highest derivation rates (19.7% and 24.7%), despite being opposite treatments in terms of Wnt modulation.

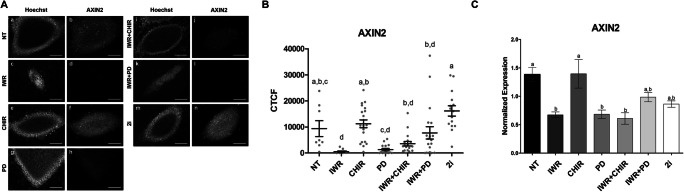

Wnt pathway transcriptional activity assessed by AXIN2 protein and mRNA levels

To confirm the successful activation/inactivation of the Wnt pathway by the signaling modulators, we assessed the presence and levels of the pathway regulator AXIN2 by immunofluorescence analysis. Axin2 is a universal Wnt target gene [14] and the level of its protein can be used as an indicator of the transcriptional activity induced by Wnt pathway activation.

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that all the lines were positive for AXIN2, although the intensity of the signal varied between treatments (Fig. 2a and b). Specifically, 2i-derived lines displayed the highest levels of AXIN2 signal (Fig. 2b), which were equivalent to those of the NT and CHIR-treated lines. As expected, the lowest levels of AXIN2 signal were detected in the IWR group, whereas lines obtained in the PD, IWR + CHIR, and IWR + PD groups presented intermediate levels. Results of Axin2 gene expression quantification by qPCR were in line with protein results, though in the 2i group, expression was slightly, but not significantly, lower than expected (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Detection and quantification of AXIN2 protein and mRNA in mESC lines derived from 1/8 blastomeres under different treatments. a Epifluorescence raw images of colonies immunostained for AXIN2 and counterstained with Hoechst. b Mean levels ± SEM of the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) for AXIN2 in mESC lines produced by the different treatments. Each gray dot represents the CTCF value of a single mESC colony. a–dDifferent superscripts indicate statistically significant differences between treatments. c Expression of Axin2 gene in blastomere-derived mESC lines measured by qPCR. Gapdh was used for normalization of cDNA amount. Data represents the mean of two lines and three technical replicates ± SEM. a,bDifferent superscripts indicate statistically significant different differences between treatments

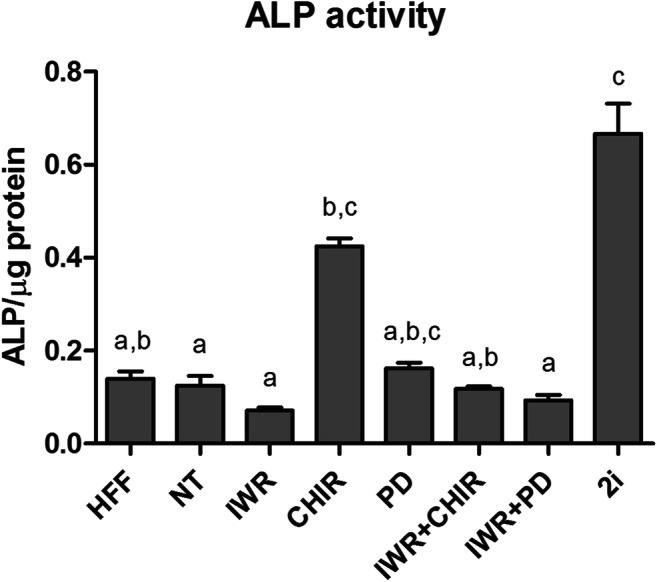

Effect of signaling modulators on ALP activity and FGF5 levels

To investigate the pluripotency features of the mESC lines obtained under the different treatments, ALP activity and FGF5 levels were analyzed. Significant differences in ALP activity were detected among groups (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, ALP activity in the feeder cells (HFF), used as a negative control, was equivalent to that of all the mESC groups, except for 2i. Indeed, the 2i-treated group showed the highest levels of ALP activity, except for CHIR- and PD-treated groups. On the other hand, mESC lines obtained from the CHIR-treated group presented an ALP activity significantly higher than that of the lines derived from the NT, IWR, and IWR + PD groups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

ALP activity in protein extracts from the mESC lines derived from 1/8 blastomeres under different treatments. Mean levels of ALP activity ±SEM. a,cDifferent superscripts indicate statistically significant differences between treatments

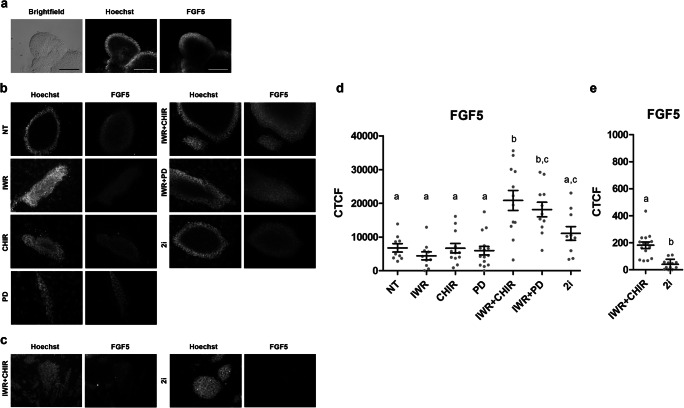

As expected, the post-implantation epiblast-specific marker FGF5 was detected in the epiblast of in vitro cultured egg cylinders [34] used as positive controls (Fig. 4a). FGF5 was also detected in all the mESC lines analyzed, even though signal intensity varied depending on the treatment (Fig. 4b and d). The highest levels of FGF5 were detected in the IWR + CHIR and IWR + PD groups, whereas lines derived from the NT, IWR, CHIR, and PD groups showed the lowest levels. Surprisingly, mESC lines from the 2i group presented intermediate FGF5 levels, which were significantly lower only than those from IWR + CHIR-treated mESC (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Detection and quantification of the ectodermal marker FGF5 in egg cylinders and in mESC lines derived from 1/8 blastomeres under different treatments. a Phase contrast and epifluorescence raw images of an in vitro cultured egg cylinder. b Representative epifluorescence raw images of colonies from mESC lines derived under the different treatments in a medium containing KSR. c Representative epifluorescence raw images of colonies from mESC lines derived from 2i and IWR + CHIR treatments in N2B27 containing medium. All fluorescence images correspond to colonies immunostained for FGF5 and counterstained with Hoechst. All the scale bars represent 100 μm. d Mean levels ± SEM of corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) for FGF5 in mESC lines produced by the different treatments in medium containing KSR. eMean levels ± SEM of corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) for FGF5 in mESC lines produced by 2i and IWR + CHIR in medium containing N2B27. Each gray dot represents the CTCF value of a single mESC colony. a–dDifferent superscripts indicate statistically significant differences between treatments

Given that mESC lines derived under the 2i treatment are supposed to be in a naïve ground state of pluripotency and not to express Fgf5, we decided to investigate a potential effect of the culture medium on Fgf5 expression. To do so, we derived and cultured new mESC lines in a medium containing the serum-free complement N2B27 [29], and we analyzed FGF5 levels in the colonies from the few mESC lines obtained under the 2i (5 mESC lines from 178 blastomeres, 2.8% of efficiency) and IWR + CHIR (3 mESC lines from 144 blastomeres, 2.1% efficiency) treatments. FGF5 signal was barely detected in 2i colonies cultured in N2B27-containing medium (Fig. 4c). When quantified, FGF5 levels were significantly reduced when compared with those in their counterparts derived in KSR-containing medium. Although FGF5 levels were also significantly reduced in the IWR + CHIR group when compared with lines cultured under the same treatment in KSR-containing medium, they were still significantly higher than those displayed by 2i-treated lines (Fig. 4e).

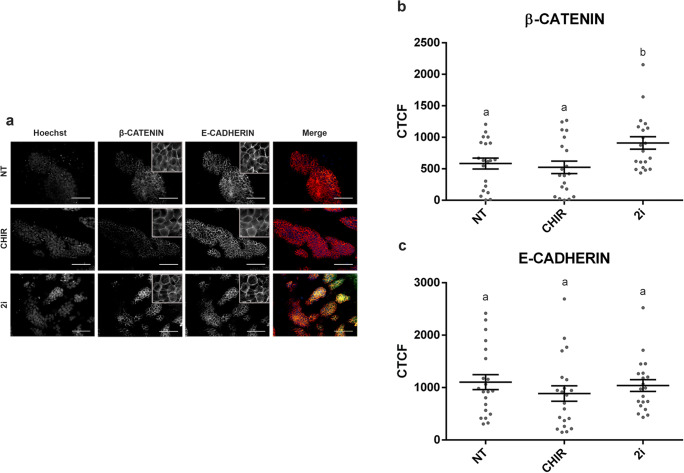

Formation of the β-CATENIN and E-CADHERIN pluripotency maintenance complex in CHIR- and 2i-derived mESC lines

Mouse ESC lines derived under the CHIR treatment resembled 2i-derived mESC lines in terms of ALP activity and AXIN2 levels, but the derivation efficiencies obtained from these two groups were significantly different. To investigate whether mESC derived under these two treatments differed in the ability to maintain naïve pluripotency through the formation of the β-CATENIN/E-CADHERIN/OCT4 membrane-associated protein complex, we next assessed the levels of E-CADHERIN and β-CATENIN proteins in mESC colonies from the CHIR and 2i groups, and we used the NT group as a negative control. The quantification of the immunofluorescence signals revealed that the levels of E-CADHERIN were equivalent in all mESC colonies analyzed, whereas β-CATENIN levels were significantly higher in mESC colonies from lines derived under the 2i treatment (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Detection and quantification of β-CATENIN and E-CADHERIN in mESC lines derived from 1/8 blastomeres under different treatments. a Epifluorescence raw and merge images of colonies immunostained for β-CATENIN and E-CADHERIN and counterstained with Hoechst. All the scale bars represent 50 μm. b, c Mean levels ± SEM of the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTFC) for β-CATENIN (b) and E-CADHERIN (c) in mESC lines from the 2i, CHIR, and NT groups. Each gray dot represents the CTCF value of a single mESC colony. a,bDifferent superscripts indicate statistically significant differences between treatments

Pluripotency gene expression and chimera production in IWR + CHIR-derived mESC lines

IWR + CHIR has been successfully used to maintain mEpiSC self-renewal without exogenous growth factors or cytokines [15]. Given that mESC lines derived and maintained in the presence of IWR + CHIR in the present study showed features of primed pluripotency, according to ALP activity and FGF5 levels, further analyses were performed to investigate their pluripotency state. We also included 2i and NT groups in these analyses, as controls.

First, we assessed by qPCR the expression of the core pluripotency gene Oct4, the naïve marker genes Rex1, Nanog, Esrrb, and Tfcp2l1, and the early post-implantation marker genes Otx2 and Dnmt3b. For all the genes analyzed, STO cells, used as a negative control, displayed barely undetectable expression levels. The results showed that mESC lines derived under the IWR + CHIR treatment significantly differed from mESC lines derived under the 2i treatment in the expression of all the markers analyzed. Specifically, IWR + CHIR-derived mESC lines expressed significantly higher levels of post-implantation genes than 2i-derived lines, which in turn expressed higher levels of core and naïve pluripotency genes (Fig. 6a). Lines derived without any treatment also displayed a unique expression profile, with high levels of Oct4, Rex1, and Esrrb, similar to those of the 2i-derived lines, low levels of Nanog and Tfcp2l1, similar to those of the IWR + CHIR-derived lines, and the highest levels of Otx2 and Dnmt3b primed pluripotency genes (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Extended pluripotency characterization of mESC lines established from single 1/8 blastomeres treated with different small-molecule inhibitors. a Expression of pluripotency, naïve and primed markers in blastomere-derived mESC lines measured by qPCR. Gapdh was used for normalization of cDNA amount. Data represents the mean of three technical replicates ± SEM. a,cDifferent superscripts indicate statistically significant different differences between treatments. b Chimera formation and germ-line transmission of mESC lines after blastocyst injection

To further investigate their pluripotency state, IWR + CHIR-, 2i-, and NT-derived mESC were injected into blastocysts to assess their potential to generate chimeric mice. IWR + CHIR-treated mESC (XY) produced five male and female pups with chimerism ranging from 65 to 100%, according to the color of their coating. The four male pups assessed showed germline transmission (Fig. 6b). The mESC line derived under the 2i treatment (XX) also produced five chimeric pups (males and females), with chimerism ranging from 25 to 100%. After crossing the chimeric females with wild-type males, germline transmission was confirmed. Finally, NT mESC (XX) produced two male pups with 5% chimerism and multiple gestation cycles (up to four) that ended up in perinatal death. Unfortunately, due to gender of the surviving pups plus the low chimerism ratio and the difficulties to get other living pups, their ability for germ line transmission could not be confirmed.

Discussion

To investigate the influence of Wnt and MAPK pathways on mESC derivation from 1/8 blastomeres and on pluripotency maintenance, a Wnt pathway activator (CHIR), a Wnt pathway inhibitor (IWR), and the MAPK pathway inhibitor (PD) were used alone or in combination during mESC establishment and culture. A total of 127 mESC lines were generated from 1094 blastomeres in KSR medium. Derivation efficiencies were calculated, AXIN2 protein and mRNA levels were assessed to confirm successful activation/inactivation of Wnt signaling pathway, and ALP activity and FGF5 levels were determined to evaluate the state of pluripotency of the obtained lines. Our results show that the different treatments resulted in different derivation efficiencies and pluripotency features of the blastomere-derived mESC lines.

The use of a single activator (CHIR) or inhibitor (IWR) of Wnt pathway resulted in extremely low derivation efficiencies of mESC lines, similar to that of the NT group. Quantification of AXIN2 protein and mRNA levels confirmed that Wnt transcriptional activity was successfully activated under the CHIR treatment but inactivated under the IWR treatment. Surprisingly, however, AXIN2 levels in mESC lines from the NT group were similar to those of the lines from the CHIR group. Considering that negligible levels of AXIN2 were reported in J1 mESC, derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of a blastocyst and cultured in medium containing KSR and LIF in feeder-free conditions [35], it is possible that the high AXIN2 levels observed in our NT mESC lines come from the Wnt proteins secreted by the feeder cells [11], in which presence is essential to derive mESC from single blastomeres [9]. Alternatively, it could be an intrinsic feature of the lines derived from single 1/8 blastomeres. Although the low AXIN2 levels displayed by our PD-treated lines seem to disagree with both hypotheses, a recent report states that MEK inhibition exerted by PD partly alleviates or antagonizes the expression of Wnt-target genes exerted by CHIR [36]. Thus, in this scenario, none of the two former hypotheses can be ruled out.

In addition to the differences in AXIN2 levels, mESC lines from the NT and single modulator treatments also differed in ALP activity. ALP activity has been used, for years, as a stem cell marker to identify pluripotent stem cells [37], but recent reports have described that naïve mESC lines present a higher ALP activity than primed ones [11, 21]. Accordingly, the high ALP activity and basal levels of FGF5 suggest that CHIR-treated mESC lines display a naïve pluripotency state. By contrast, NT and IWR-treated mESC lines showed features of both naïve (basal levels of FGF5) and primed (low levels of ALP activity) pluripotency states. Besides, qPCR analysis in NT lines revealed that these cells displayed a unique expression profile with high levels of both core (Oct4) and naïve transcription factor (Rex1 and Esrrb) genes, but also of the two early post-implantation genes, Otx2 and Dnmt3b, characteristic of primed pluripotent stem cells. Therefore, mESC from the NT and IWR groups could either be in an intermediate state of pluripotency or consist of heterogeneous populations of naïve-like and primed-like cells. In mEpiSC lines derived from post-implantation embryos, Wnt inhibition has been reported to induce primed pluripotency, but only when combined with molecules promoting EpiSC-like viability [15, 24], indicating that the sole use of IWR might not be sufficient to induce fully primed pluripotency. On the other hand, it is well documented that mESC cultured in the presence of serum + LIF are characterized by cell heterogeneity in both expression of transcription factors and sensitivity to signaling molecules and are composed of different cell subtypes with naïve-like and primed-like identities [26, 38–40]. Loss of Nanog or Otx2 overexpression results in the marked contraction of the naïve-like compartment and the expansion of the primed-like subtype [39]. Altogether, these evidences argue in favor of heterogeneous populations in our IWR and NT mESC lines. Heterogeneity also exists in vivo in the preimplantation mouse embryo at E4.5-E4.7, when the epiblast gradually starts to lose naïve identity before inducing the early primed state [40]. Derivation and culture of mESC in the absence of exogenous signaling modulators or by inactivating Wnt signaling pathway might allow to capture in vitro this transitional heterogeneity of the preimplantation epiblast.

Mouse ESC lines from the NT, CHIR, and IWR groups shared the highest rates of non-progressive outgrowths, due to a massive differentiation occurring during the second passage. To prevent this differentiation, which could be attributed to an autoinduction of the MAPK pathway [41], we included a new group of treatment with the MEK inhibitor PD. Since the use of PD might be sufficient to maintain the naïve ground state in mESC [21], we first used the inhibitor alone. Interestingly, 1/8 blastomeres from the PD group did not produce a high percentage of outgrowths, maybe due to their poor survival at clonal density because of compromised cell growth and viability [7]. However, since they experienced significantly less differentiation during the second passage, PD-treated blastomeres resulted in slightly higher derivation efficiencies than blastomeres from the NT, IWR, and CHIR groups. Regarding their pluripotency, PD-derived lines again showed features of both naïve (low levels of FGF5) and primed (low ALP activity) pluripotency, indicating a similar pluripotency state to lines in the NT and IWR groups.

The combination of PD with CHIR, in the 2i cocktail, resulted in the highest derivation efficiencies, confirming that, as previously reported, the dual action of these two modulators has a positive synergistic effect in mESC derivation from both blastocysts and 1/8 blastomeres [7, 29]. Similar to the CHIR-treated lines, mESC derived from 1/8 blastomeres treated with 2i displayed high AXIN2 levels. Nonetheless, they were equivalent to those of the NT lines, suggesting that the addition of CHIR, alone or combined with PD, did not enhance the transcriptional activation of Wnt-target genes with respect to the NT lines. It is possible that CHIR-induced Wnt activation maintains pluripotency through other transcription-independent mechanisms not occurring in mESC lines from other treatments, such as the formation of a β-CATENIN, OCT4, and E-CADHERIN complex associated to membranes [10]. In line with this theory, our results show that while all NT-, CHIR-, and 2i-derived mESC lines have homogeneous and high levels of E-CADHERIN [27], only the 2i-treated lines have significantly higher levels of β-CATENIN, colocalizing with the E-CADHERIN signal. Thus, the ability to accumulate β-CATENIN in the cytosol could be the key factor that guarantees a successful derivation process observed only in those blastomeres treated with 2i.

Regarding the state of pluripotency, our results show that, like in blastocyst-derived mESC lines, 2i also promotes features of naïve pluripotency in blastomere-derived lines, such as high ALP activity, high levels of core and naïve pluripotency gene expression, very low levels of early-postimplantation gene expression, and contribution to the formation of chimeric mice with proved germ line transmission. As previously described in blastocyst-derived lines [42], our blastomere-derived 2i mESC lines displayed upregulation of the naïve pluripotency genes Nanog and Tfcp2l1 compared with NT lines, but others such as Rex1 and Esrrb, as well as Oct4, were similarly expressed, reflecting a unique transcriptional profile that characterizes ground state and naïve mESC lines. FGF5 levels were slightly higher than expected, but when 2i-treated lines were derived in medium containing N2B27 instead of KSR, FGF5 levels were significantly reduced. Previous reports indicate that mESC lines cultured in medium containing FCS express basal levels of FGF5 [38], probably due to some unknown components of the serum. Although KSR is a more defined FCS-free formulation, it is plausible that some of its components can also induce FGF5 expression. Nevertheless, derivation of mESC from 1/8 blastomeres in N2B27-containing medium results in extremely low efficiencies, as shown both in the present study and in a previous one [29]. Thus, when deriving mESC from single blastomeres, a compromise must be reached between promoting the full ground state of pluripotency, with the more defined medium containing N2B27, or enhancing derivation efficiency, with the medium containing KSR.

To further investigate the roles of Wnt and MAPK signaling in the derivation of mESC from 1/8 blastomeres, we decided to inhibit both pathways using IWR + PD. We also exerted an antagonistic modulation of Wnt pathway using IWR + CHIR, according to a previous work using this same treatment in mEpiSC [15]. To our knowledge, these two treatments have not been previously applied for the derivation and/or culture of mESC lines. Surprisingly, derivation efficiencies obtained from both treatments were moderately high. Mouse ESC lines established from both treatments displayed intermediate levels of AXIN2, which were slightly higher than in IWR- and PD-treated mESC lines. For the IWR + CHIR combination, these results agree with those reported by Kim and coworkers in mEpiSC [15], indicating that the accumulation of β-CATENIN induced by CHIR allows the synthesis of AXIN2, which is stabilized in the cytoplasm by IWR and forms a complex with β-CATENIN. This complex blocks β-CATENIN’s translocation into the nucleus, preventing the expression of further Wnt-target genes, including genes regulating differentiation, and thus maintaining primed-like pluripotency in mEpiSC [15]. In the case of IWR + PD, the mechanism causing AXIN2 increase is unclear. In the two groups, high levels of FGF5 and low levels of ALP activity were observed, a pattern typical of primed pluripotency. Moreover, IWR + CHIR-treated mESC showed significant levels of Otx2 and Dnmt3b expression and low levels of expression of the genes associated with naïve pluripotency. However, they successfully contributed to chimera formation with germline transmission, which questions their fully primed identity. Several studies provide evidence that EpiSC rarely contribute to the formation of chimeric mice when injected into blastocysts, and the ability for germ line transmission has not been reported [27, 43]. In views of this, our blastomere-derived IWR + CHIR mESC lines may have transitioned to a more primed-like intermediate state, without reaching fully primed pluripotency. Despite that the formative pluripotency state has not been fully characterized, the molecular features and the developmental potential of our IWR + CHIR mESC lines fit the predictive features of this intermediate pluripotency state [26]. Although it is out of the scope of the present study, it is of future interest to characterize these IWR + CHIR mESC lines in more detail to better assess their pluripotent state and confirm whether or not they might be a new in vitro representative of the formative pluripotent state that could be stably maintained in culture.

Conclusion

Modulation of Wnt and MAPK signaling pathways during the derivation and culture of mESC from single 1/8 blastomeres results in the generation of mESC lines with varying efficiencies and showing different pluripotent features. Inhibition of Wnt (IWR) or MAPK (PD) signaling pathways with single modulators or absence of treatment results in low to moderate derivation rates of mESC lines with co-existing naïve- and primed-like pluripotency features, probably reflecting their heterogeneous nature. Generation of fully naïve pluripotent mESC is only obtained under treatments that activate Wnt pathway (CHIR and 2i), and improved derivation rates require the simultaneous inactivation of MAPK pathway (2i). The use of the Wnt inhibitor IWR together with a Wnt activator (CHIR) or a MAPK inhibitor (PD) results in high to intermediate derivation rates of mESC lines displaying molecular primed-like features, but that in the case of IWR + CHIR-treated lines are able to successfully generate germline competent chimeric mice, resembling the predicted properties of formative pluripotency. Thus, as for blastocyst-derived mESC lines, Wnt and MAPK pathways have a key role in the successful derivation and pluripotency features of mESC from single precompaction blastomeres.

Acknowledgments

We thank staff from Servei Estabulari from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona for animal care, Jonatan Lucas for help with feeder cell culture and reagent preparation and Salvador Bartolomé for his assistance and advice in the design of the RT-qPCR experiments.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

MVC: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, visualization. SAA: formal analysis, investigation, visualization. AP: investigation. JS: conceptualization, writing – review & editing, funding acquisition. EI: conceptualization, writing – review & editing, funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad of Spain (AGL2014-52408-R) and the Generalitat de Catalunya (2014 SGR-524 and 2017 SGR-503). MVC and SAA were beneficiary of a PIF-UAB fellowship.

Data availability

Available upon request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Mouse care and procedures were conducted according to the protocols approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal and Human Research of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and by the Departament d’Agricultura, Ramaderia, Pesca i Alimentació of the Generalitat de Catalunya (ref. 9995 and 9582).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. PNAS. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakayama S, Hikichi T, Suetsugu R, Sakaide Y, Bui H-T, Mizutani E, Wakayama T. Efficient establishment of mouse embryonic stem cell lines from single blastomeres and polar bodies. Stem Cells. 2007;25:986–993. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AG, Heath JK, Donaldson DD, Wong GG, Moreau J, Stahl M, Rogers D. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–690. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams RL, Hilton DJ, Pease S, Willson TA, Stewart CL, Gearing DP, Wagner EF, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Gough NM. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336:684–687. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva J, Smith A. Capturing Pluripotency. Cell. 2008;132:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ying Q-L, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, Cohen P, Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czechanski A, Byers C, Greenstein I, Schrode N, Donahue LR, Hadjantonakis A-K, Reinholdt LG. Derivation and characterization of mouse embryonic stem cells from permissive and nonpermissive strains. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:559–574. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boroviak T, Loos R, Bertone P, Smith A, Nichols J. The ability of inner-cell-mass cells to self-renew as embryonic stem cells is acquired following epiblast specification. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:516–528. doi: 10.1038/ncb2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faunes F, Hayward P, Descalzo SM, Chatterjee SS, Balayo T, Trott J, et al. A membrane-associated β-catenin/Oct4 complex correlates with ground-state pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development. 2013;140:1171–1183. doi: 10.1242/dev.085654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ten Berge D, Kurek D, Blauwkamp T, Koole W, Maas A, Eroglu E, et al. Embryonic stem cells require Wnt proteins to prevent differentiation to epiblast stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:1070–1075. doi: 10.1038/ncb2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wray J, Kalkan T, Gomez-Lopez S, Eckardt D, Cook A, Kemler R, Smith A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 alleviates Tcf3 repression of the pluripotency network and increases embryonic stem cell resistance to differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:838–845. doi: 10.1038/ncb2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Newman JJ, Kagey MH, Young RA. Tcf3 is an integral component of the core regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:746–755. doi: 10.1101/gad.1642408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clevers H. Wnt/b-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H, Wu J, Ye S, Tai CI, Zhou X, Yan H, et al. Modulation of beta-catenin function maintains mouse epiblast stem cell and human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2403. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberger L, Ayyash M, Novershtern N, Hanna JH. Dynamic stem cell states: naive to primed pluripotency in rodents and humans. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:155–169. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols J, Smith A. Pluripotency in the embryo and in culture. Cold Spring Harb Perspectives Biol. 2012;4:1–15. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva J, Nichols J, Theunissen TW, Guo G, van Oosten AL, Barrandon O, et al. Nanog is the gateway to the pluripotent ground state. Cell. 2009;138:722–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martello G, Bertone P, Smith A. Identification of the missing pluripotency mediator downstream of leukaemia inhibitory factor. EMBO J. 2013;32:2561–2574. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sim Y-J, Kim M-S, Nayfeh A, Yun Y-J, Kim S-J, Park K-T, et al. 2i maintains a naive ground state in ESCs through two distinct epigenetic mechanisms. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye S, Liu D, Ying Q-L. Signalling pathways in induced naïve pluripotency. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;28:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mak W, Nesterova TB, de Napoles M, Appanah R, Yamanaka S, Otte AP, et al. Reactivation of the paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Science (80-. ) 2004;303:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1092674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimoto M, Kondo M, Koga Y, Shiura H, Ikeda R, Hirose M, et al. A simple and robust method for establishing homogeneous mouse epiblast stem cell lines by Wnt inhibition. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:744–757. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi K, Ohta H, Kurimoto K, Aramaki S, Saitou M. Reconstitution of the mouse germ cell specification pathway in culture by pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2011;146:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith A. Formative pluripotency: the executive phase in a developmental continuum. Development. 2017;144:365–373. doi: 10.1242/dev.142679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgani S, Nichols J, Hadjantonakis AK. The many faces of pluripotency: in vitro adaptations of a continuum of in vivo states. BMC Dev Biol. 2017;17:10–12. doi: 10.1186/s12861-017-0150-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H-J, Zhang X, Zheng JJ. Inhibiting the wnt signaling pathway with small molecules. Target Wnt Pathw Cancer. 2011;00:183–209. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8023-6_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vila-Cejudo M, Massafret O, Santaló J, Ibáñez E. Single blastomeres as a source of mouse embryonic stem cells: effect of genetic background, medium supplements, and signaling modulators on derivation efficiency. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;36:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.González S, Ibáñez E, Santaló J. Influence of E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion on mouse embryonic stem cells derivation from isolated blastomeres. Stem Cell Rev Reports. 2011;7:494–505. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCloy RA, Rogers S, Caldon CE, Lorca T, Castro A, Burgess A. Partial inhibition of Cdk1 in G2 phase overrides the SAC and decouples mitotic events. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1400–1412. doi: 10.4161/cc.28401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFarlane L, Truong V, Palmer JS, Wilhelm D. Novel PCR assay for determining the genetic sex of mice. Sex Dev. 2013;7:207–211. doi: 10.1159/000348677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaztelumendi N, Nogués C. Chromosome instability in mouse embryonic stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep05324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bedzhov I, Leung CY, Bialecka M, Zernicka-Goetz M. In vitro culture of mouse blastocysts beyond the implantation stages. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:2732–2739. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y, Liu F, Liu Y, Liu X, Ai Z, Guo Z, et al. GSK3 inhibitors CHIR99021 and 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime inhibit microRNA maturation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8666. doi: 10.1038/srep08666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saj A, Chatterjee SS, Zhu B, Cukuroglu E, Gocha T, Zhang X, et al. Disrupting interactions between β-catenin and activating TCFs reconstitutes ground state pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1924–1933. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Matsui Y, Zsebo K, Hogan BLM. Derivation of pluripotential embryonic stem cells from murine primordial germ cells in culture. Cell. 1992;70:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashi K, Lopes SMC d S, Tang F, Surani MA. Dynamic equilibrium and heterogeneity of mouse pluripotent stem cells with distinct functional and epigenetic states. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acampora D, Di Giovannantonio LG, Garofalo A, Nigro V, Omodei D, Lombardi A, et al. Functional antagonism between OTX2 and NANOG specifies a spectrum of heterogeneous identities in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:1642–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acampora D, Omodei D, Petrosino G, Garofalo A, Savarese M, Nigro V, et al. Loss of the Otx2-binding site in the Nanog promoter affects the integrity of embryonic stem cell subtypes and specification of inner cell mass-derived epiblast. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2651–2664. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunath T, Saba-El-Leil MK, Almousailleakh M, Wray J, Meloche S, Smith A. FGF stimulation of the Erk1/2 signalling cascade triggers transition of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from self-renewal to lineage commitment. Development. 2007;134:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.02880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghimire S, Van Der Jeught M, Neupane J, Roost MS, Anckaert J, Popovic M, et al. Comparative analysis of naive, primed and ground state pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells originating from the same genetic background. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurek D, Neagu A, Tastemel M, Tüysüz N, Lehmann J, Van De Werken HJG, et al. Endogenous WNT signals mediate BMP-induced and spontaneous differentiation of epiblast stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request.