Abstract

Acacia species are very important tree species in tropical and subtropical countries of the World for their economic and medicinal benefits. Precise identification of Acacia is very important to distinguish the invasive species from rare species however, it is difficult to differentiate Acacia species based on morphological charcters. In addition, precise identification is also important for wood charcterization in the forest industry as these species are declining due to illegal logging and deforestation. To overcome thsese limitations of morphological identification, DNA barcoding is being used as an efficient and quick approach for precise identification of tree species. In this study, we selected two chloroplast and plastid base DNA markers (rbcL and matK) for the identification of five selected tree species of Acacia (A. albida, A. ampliceps, A. catechu, A. coriacea and A. tortilis). The genomic DNA of the selected Acacia species was extracted, amplified through PCR using specific primers and subsequently sequenced through Sanger sequencing. In matK DNA marker the average AT nucleotide contents were higher (59.46%) and GC contents were lower (40.44%) as compared to the AT (55.40%) and GC content (44.54%) in rbcL marker. The means genetic distance K2P between the Acacia species was higher in matK (0.704%) as compared to rbcL (0.230%). All Acacia species could be identified based on unique SNPs profile. Based on SNP data profiles, DNA sequence based scannable QR codes were developed for accurate identification of Acacia species. The phylogenetic analysis based on both markers (rbcL and matK) showed that both A. coriacea and A. tortilis were closely related with each other and clustered in the same group while other two species A. albida and A. catechu were grouped together. The specie A. ampliceps remained ungrouped distantly, compared with other four species. These finding highlights the potential of DNA barcoding for efficient and reproducible identification of Acacia species.

Keywords: Desertification, Acacia, Genetic diversity, Afforestation, DNA barcoding

1. Introduction

DNA barcoding is a widely accepted technique that focuses on nucleotide sequence based identification of plant species in a an efficient and precise manner (Group et al., 2009). DNA barcoding have been developed as a system for species recognition and identification by using specific regions of DNA sequences (Hebert et al., 2003, Asif and Cannon, 2005, Newmaster et al., 2006, Kress and Erickson, 2007, Ratnasingham and Hebert, 2007, Fazekas et al., 2008, Lahaye et al., 2008, Pettengill and Neel, 2010). One of the major challenges faced by barcoding, is the ability to resolve sister species within a large geographical ranges. It has been suggested that a system based on any one or small number of chloroplast genes will fail to differentiate taxonomic groups with extremely low amount of plastid variations while it will be effective in other groups. Steven et al. (2009) successfully utilized barcoding in discriminating multiple populations among a sister species complex in pantropical Acacia subgenus across three subcontinents. The use of three chloroplast regions i.e. rbcL, matK and trnH-psbA successfully discriminated sister species within both genera and differentiated biogeographical patterns among populations from India, Africa and Australia. These findings clearly established the power of DNA barcoding for taxonomic and biogeographical studies, for identifying cryptic species as well as biogeographic patterns for resolving classification at the rank of genera and species level. The matK gene has ideal size, high rate of substitution, a large proportion of variation at nucleic acid level at the first and second codon positions, low transition/transversion ratio and the presence of mutational conserved regions. These features of matK gene are exploited to resolve family and species level relationships. Using matK, about 90% amplification was achieved in angiosperm by using single pair of primer while with gymnosperm the amplification percentage was 83% and cryptogam was 10% (Lahaye et al., 2008). Similarly, rbcL has been greatly utilized for phylogenetic analysis offering better results at family and class levels however, it showed moderate discrimination power at the species level (Fazekas et al., 2008, Lahaye et al., 2008, Hollingsworth et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2010).

Acacia is an economically important genus, belongs to family Fabaceae. There are 1380 species of Acacia and with about two third are native to Australia while others are found in tropical and subtropical regions of the World (Maslin et al., 2003, Orchard and Maslin, 2003; Muhammad et al., 2017, Muhammad et al., 2018). Acacia species are economically very important and well adopted to arid conditions and in agroforestry. These species are used for fuelwood, pulp, fodder, fiber, timber, medicine, enhancing the fertility of degraded soils due to its ability of fixing nitrogen, environmental amelioration, gums and tannins (Midgley and Turnbull, 2003). The genus Acacia consists of three subgenera; found in all tropics i.e. Acacia, Aculiferum and Phyllodineae. These subgenera are differentiated based on morphological and genetic variation (Maslin et al., 2003). The morphological identification however is very difficult due to the large diversity of invasive, natural hybrids and rare cryptic species (Steven et al., 2009).

Consortium for the Barcode of life (CBOL) has reported that the matK and rbcL are the main barcode markers for accurate identification of plants and trees (Li et al., 2011). Therefore, the main objective of this study was to identify various Acacia species by using sequence specific markers (matK and rbcL) and to develop DNA barcodes.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection and DNA extraction

The research was conducted in the Center for Advance studies in Agriculture and Food security (CAS-AFS), University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Punjab Pakistan. The open pollinated seeds from five Acacia species (A. albida, A. ampliceps, A. coriacea, A. catechu and A. tortilis) were collected from premesis of Pakistan Forest Institute (PFI), Peshawar, Khyber PakhtunKhwa (KPK), Pakistan. Acacia species with their local names, scientific name and their origin has been given in Table 1. The genomic DNA was extracted from the seedlings by using cetyl-trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method. The quantification and purity of extracted DNA were measured using NanoDrop (ND-8000) (Thermo-Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 1.

Acacia species used in this study, their local names, scientific name, center of origin and ecological region.

| Common/local name | Scientific name | Origin | Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sufaid kiker | Acacia albida | Southwest Africa | Tropical thorn to subtropical regions and precipitation of 250 to 400 mm/yr |

| Australian kiker | Acacia ampliceps | Northwest Australia | Subtropical and tropical zones and precipitation of 400 to 600 mm/yr |

| Catha | Acacia catechu | Pakistan, India and Nepal | Sub humid to subtropical climate and precipitation of 500 to 2700 mm/yr |

| Desert oak | Acacia coriacea | Northern Australia | Tropical and subtropical of Australia and precipitation of 300 to 500 mm/yr |

| Samoor | Acacia tortilis | Africa | Arid to semi-arid and precipitation of 100 to 1000 mm/yr |

2.2. PCR amplification with matK and rbcL primers

High quality template DNA (20ng) was used for PCR amplification, using selected primers (Table 2). Amplifications were performed in PCR tubes using a C–1000 Touch Thermocycler (Bio-Rad). PCR reaction was carried out in a total volume of 20μl containing 20 ng/μl genomic DNA template, 0.2 mM of each primer, 2 μl Taq buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM MgCl2 pH = 8.3), 0.5μl Taq DNA polymerase (5U/µl, Thermo Scientific Amercia), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.2 mM dNTPs (10 mM) and 7.5 μl double distilled deionized water. The optimized PCR profile for both rbcL and matK comprised of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, subsequently 30 cycles starting with 95 °C denaturation for 30 sec., annealing for rbcL and matK at 50 °C and 45 °C respectively for 30 sec, followed with a final extension at 72 °C for 1 min. The amplified PCR products were resolved on 1.3% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide for 20 minutes. Amplicon sizes were confirmed by comparing with 1Kb DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The PCR products was purified for Sanger sequencing by using FavorPrepTM PCR Cleanup Mini Kit (FAVORGEN, Cat# FAPCK001-1).

Table 2.

PCR primers for matK and rbcL markers. Forward (F) and reverse (R) primers with their 5'-3' sequences used for the amplification of plastid DNA sequences.

| Loci | Primer | Sequences |

|---|---|---|

| matK | F | 5'-CCTCATCTGGAAATCTTGGTT-3' |

| matK | R | 5'-GCTTATAATGAGAAAGATTTCTGC-3' |

| rbcL | F | 5'-ATGTCACCACAAACAGAAAC-3' |

| rbcL | R | 5'-TCGCATGTACCTGCA-3' |

2.3. Sequencing and data analysis

PCR amplicons were purified and submitted for sequencing through Sanger method (Eurofins Genomics, Germany GmbH). After sequencing, the resultant sequences were edited manually and multiple sequence alignment was performed using bioinformatics software MEGAX 10.1 developed by Penn State University, USA. Most of the mismatched sites and gaps were excluded using SeqMan software (DNAStar). The sequencing data was further utilized to identify AT (Adenine + Thymine) and GC (Guanine + Cytosine) contents and SNPs for each species. In addition, data was also used to develop DNA barcodes for each species by using online DNA Barcode Generator (QR barcode) software (https://www.the-qrcode-generator.com/). Several DNA regions were used to generate effective DNA barcodes for Acacia Species as previously reported by different researches (Fazekas et al., 2008, Lahaye et al., 2008). Phylogenetic relationship among species was developed through cluster analysis in R Core Team (R Core Team 2013).

3. Results

The specific genomic fragments of all selected species of Acacia were successfully amplified by using both rbcL and matK primers with an average read length of 750bp and 950 bp (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Similarly, DNA sequencing for both rbcL and matK amplicons generated high quality sequences. Nucleotide composition of amplicons from selected species of Acacia revealed variability in AT and GC contents. In amplicons of matK, nucleotide composition of AT and GC for Acacia species Acacia albida, A. ampliceps, A. coriacea, A. catechu and A. tortilis were (62.7%, 57.3%, 66%, 44.1% and 67.2%) and (37.2%, 42.6%, 33.9%, 55.8% and 32.7%) respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3). In rbcL, AT and GC contents were (56.9%, 54.5%, 52.2%, 56.8% and 56.6%) and (43%, 45.5%, 47.7%, 43.2% and 43.3%) respectively as compared to matK. Overall, in both markers (rbcL and matK), the average AT contents was higher (57.43%) than average GC (42.49%) contents (Fig. 3 and Table 3). In rbcL, the minimum, maximum, mean and standard error of K2P genetic distance between Acacia species were calculated to be 0.078%, 0.368%, 0.230% and 0.0140% respectively. Similarly, in matK, the minimum, maximum, means and standard error of K2P genetic distance between species were 0.048%, 1.01%, 0.704% and 0.088% respectively (Table 4). Moreover, for sequence data analysis, the obtained sequences were subjected to BLAST (Basic local alignment search tool) in the NCBI nucleotide database, which showed maximum similarity range from 92 − 98% for rbcL and 88–97% for matK. In addition, NCBI database sequences with maximum similarity to the queries were downloaded for comparison to the experimental species. For comparison of matK sequences, the reference sequences, accession numbers and gene bank name for the Acacia species were Faidherbia albida (JF265429.1), Senegalia catechu (MH560438.1) and Vachellia nilotica (KX119249.1). The reference sequence for rbcL marker matched with Faidherbia albida (HM020737.1), Acacia grandicornuta (EU812049.1), Vachellia tortilis (MK290437.1) and Acacia cyclops (JQ412187.1). No similarity was found in A. tortilis and A. coriacea for rbcL and similarly, for matK no sequence homology was observed for A. ampliceps (Table 5). DNA sequences were subsequently used to develop phylogenetic relationship between Acacia species.

Fig. 1.

PCR amplification products with matK primers resolved on 1.3% agarose gel electrophoresis. M representing DNA ladder lines, N is a negative control, lane 1–5 Acacia albida, Acacia ampliceps, Acacia catechu, Acacia coriacea and Acacia tortilis. Lane 6-8 are duplicate loaded samples of Acacia. An amplicon of 930 bp was amplified.

Fig. 2.

PCR amplified products using rbcL specific primers. M representing DNA ladder, lane 1–5 representing PCR amplification of Acacia albida, Acacia ampliceps, Acacia catechu, Acacia coriacea and Acacia tortilis respectively. Lane 6-10 are duplicate laoded products. An amplicon of 750 bp was amplified in all tested species.

Table 3.

The average AT% and GC% nucleotide composition of selected Acacia species based on matK and rbcL markers. AT and GC nucleotide contents were calculated from the sequence data obtained from sequencing amplicons with specific primers.

| Markers | Acacia Species | AT | GC | Total | AT (%) | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| matK | Acacia albida | 224 | 133 | 357 | 62.7 | 37.2 |

| Acacia ampliceps | 335 | 249 | 584 | 57.3 | 42.6 | |

| Acacia coriacea | 590 | 303 | 893 | 66 | 33.9 | |

| Acacia catechu | 86 | 109 | 195 | 44.1 | 55.8 | |

| Acacia tortilis | 512 | 249 | 761 | 67.2 | 32.7 | |

| Average | 59.46% | 40.44% | ||||

| rbcL | Acacia albida | 226 | 171 | 397 | 56.9 | 43 |

| Acacia ampliceps | 151 | 126 | 277 | 54.5 | 45.5 | |

| Acacia coriacea | 359 | 328 | 687 | 52.2 | 47.7 | |

| Acacia catechu | 396 | 301 | 697 | 56.8 | 43.2 | |

| Acacia tortilis | 400 | 306 | 706 | 56.6 | 43.3 | |

| Average | 55.4% | 44.54% | ||||

Fig. 3.

Nucleotide composition in amplicons of Acacia species using matK and rbcL.

Table 4.

Genetic distance and differentiation between the Acacia species based on rbcL and matK markers.

| Markers | Minimum | Maximum | Means | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rbcL | 0.078 | 0.368 | 0.230 | 0.040 |

| matK | 0.048 | 1.010 | 0.704 | 0.088 |

Table 5.

Tree species of Acacia with highest BLAST pairwise identity (%) for rbcL and matK. Reference species with their accession number for selected Acacia species with both rbcL and matK markers.

| Markers | Species | Gene Bank/BLAST | Max. ID(%) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rbcL | Acacia albida | Faidherbia albida | 96.78 | JF265429.1 |

| Acacia catechu | Senegalia catechu | 98.40 | MH560438.1 | |

| Acacia ampliceps | Vachellia nilotica | 92.55 | KX119249.1 | |

| Acacia tortilis | No sequence similarity | -- | -- | |

| Acacia coriacea | No sequence similarity | -- | -- | |

| matK | Acacia albida | Faidherbia albida | 95.22 | HM020737.1 |

| Acacia catechu | Acacia grandicornuta | 88.52 | EU812049.1 | |

| Acacia ampliceps | No sequence similarity | -- | -- | |

| Acacia tortilis | Vachellia tortilis | 96.14 | MK290437.1 | |

| Acacia coriacea | Acacia cyclops | 97.39 | JQ412187.1 | |

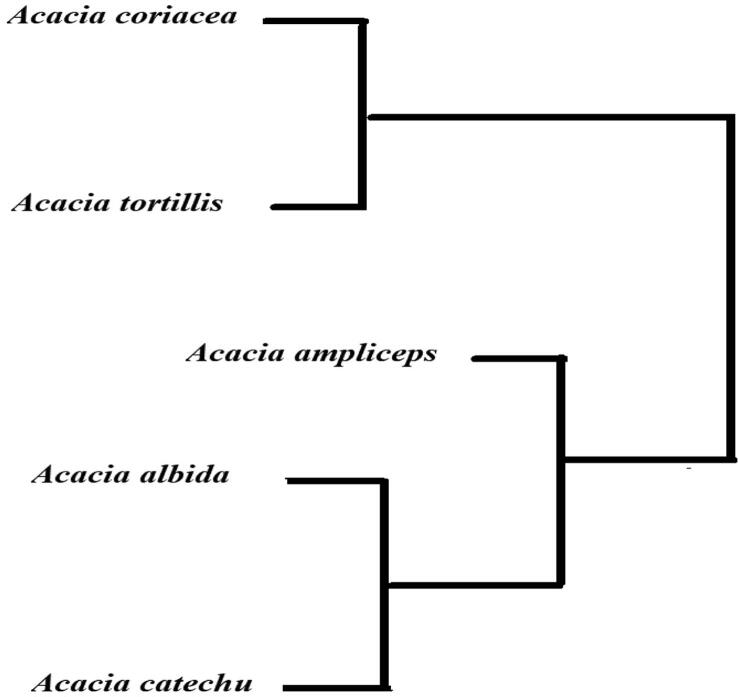

After sequencing, all the resultant sequences of rbcL and matK were aligned in order to generate dendrogram which depicts genetic relationship among the selected Acacia species. Phylogenetic tree based approach was used to classify the selected tree species of Acacia using rbcL and matK markers. All the sequences were edited manually as well as using SeqMan software i.e. similar, mismatch sites and all the gaps were removed for proper screening of SNPs. Moreover, only those sequences were selected for detection of SNPs, which have shown differentiation in only a single base pair in all experimented tree species of Acacia. A total of 42 unique SNP based variant sites were found in five selected Acacia species for differentiation through rbcL marker. Based on rbcL data analysis, the number of unique sites observed in the selected five Acacia species were as following, A. albida (0), A. ampliceps (1), A. coriacea (17), A. catchu (2) and A. tortilis (22) (Table 6). As described earlier that in rbcL, the minimum, maximum, mean and standard error of K2P genetic distance between Acacia species were 0.078%, 0.368%, 0.230% 0.0140%, additional analysis with sequences based phylogenetic evaluation, further characterized the selected Acacia species. The Acacia albida and Acacia ampliceps remained in a closely related group, comparative to other three species. However, the Acacia tortilis remained distant from all other Acacia species (Fig. 4). A total of 40 unique sites were identified in experimented Acacia species, when assayed with matK marker. The number of unique SNPs with matK were as following, A. albida (5), A. ampliceps (26), A. coriacea (1), A. catchu (8) and A. tortilis (0) (Table 6). As discussed earlier that in matK based characterization, the minimum, maximum, means and standard error of K2P genetic distance between the Acacia species were, 0.048%, 1.01%, 0.704% and 0.088% respectively (Table 4). Further, phylogenetic characterization with matK marker, revealed that A. coriacea and A. tortilis were linked closely, while the other two species A. albida and A. catechu were clustered together and the specie A. ampliceps remained ungrouped and consequently found dissimilar to all other four Acacia species (Fig. 5). Phylogenetic relationship among selected species of Acacia using both markers showed that A. coriacea and A. tortilis were clustered together compared A. ampliceps. Similarly, A. albida and A. catechu were also closely linked and grouped together combined analysis (Fig. 6). Through these unique SNPs, we developed barcode for selecyed Acacia species by using rbcL and matK sequences separately. Both rbcL and matK markers identified Acacia species differently supporting use of different DNA markers for species differentiation. When used, these barcode independently differentiated Acacia species thus can be applied to identify species through barcode scanning apps on smart phones (see Fig. 7).

Table 6.

The barcode of selected species of Acacia based on variable regions of rbcL and matK markers. Italic nucleotides show unique SNP variations observed in this study.

| Marker | Acacia albida | Acacia ampliceps | Acacia coriacea | Acacia catechu | Acacia tortilis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rbcL | T | T | G | T | T |

| C | C | C | T | C | |

| A | A | T | A | A | |

| A | A | A | A | C | |

| T | T | T | T | C | |

| A | A | A | A | T | |

| A | A | G | A | A | |

| C | C | G | C | C | |

| A | A | C | A | A | |

| T | A | T | T | A | |

| C | C | C | C | T | |

| T | T | T | T | C | |

| T | T | T | T | C | |

| G | G | G | G | T | |

| A | A | A | A | C | |

| G | G | G | G | T | |

| A | A | A | G | A | |

| G | G | G | G | T | |

| C | C | C | C | T | |

| G | G | G | G | T | |

| A | A | A | A | G | |

| G | G | G | G | A | |

| C | C | C | C | A | |

| C | C | C | C | T | |

| T | T | T | T | C | |

| C | C | A | C | C | |

| T | T | T | T | C | |

| T | T | T | T | A | |

| T | T | A | T | T | |

| A | A | G | A | A | |

| C | C | G | C | C | |

| A | A | G | A | A | |

| A | A | C | A | A | |

| A | A | A | A | T | |

| T | T | C | T | T | |

| G | C | G | G | G | |

| A | A | T | A | A | |

| A | A | G | A | A | |

| A | A | C | A | A | |

| T | T | G | T | T | |

| T | T | A | T | T | |

| T | T | T | T | A | |

| matK | A | A | A | T | A |

| A | G | A | A | A | |

| T | G | T | T | T | |

| T | T | A | T | T | |

| T | T | T | C | T | |

| A | G | A | A | A | |

| A | A | A | G | A | |

| T | T | T | C | T | |

| G | A | G | G | G | |

| T | C | T | T | T | |

| C | T | C | C | C | |

| A | T | A | A | A | |

| G | A | A | A | A | |

| C | A | A | A | A | |

| T | C | T | T | T | |

| T | G | T | T | T | |

| G | A | G | G | G | |

| C | T | C | C | C | |

| T | G | G | G | G | |

| T | A | T | T | T | |

| G | A | G | G | G | |

| A | C | A | A | A | |

| G | C | C | C | C | |

| T | T | T | G | T | |

| T | T | T | A | T | |

| A | C | C | C | C | |

| A | G | A | A | A | |

| A | A | A | T | A | |

| G | A | G | G | G | |

| C | A | C | C | C | |

| A | G | A | A | A | |

| G | A | G | G | G | |

| T | C | T | T | T | |

| T | A | T | T | T | |

| C | A | C | C | C | |

| G | T | G | G | G | |

| T | T | T | G | T | |

| A | T | A | A | A | |

| G | T | G | G | G | |

| A | T | A | A | A | |

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic relationship between different Acacia species differentiated based on rbcL genetic marker.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic relationship between different Acacia species differentiated based on matK genetic marker.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic relationship between different Acacia species differentiated based on both matK and rbcL genetic marker.

Fig. 7.

QR barcode of different Acacia species, based on rbcL and matK.

4. Discussion

Acacia and their hybrids are an emerging forest tree species for fuelwood and pulpwood production due to high growth rate and high adaptability to various environments. Acacias are more desirable than Eucalypts due to low water requirement thus suitable for arid and semiarid regions of the World. However, for future sustainable biomass, fuelwood and pulp supply breeding of improved materials with desirable traits e.g. low lignin, low tannin, longer fiber, high wood density and straight bole require precise selection of superior trees. Precise identification of Acacias based on DNA markers is highly desirable, to select superior species with beneficial characters. In post-genomic era with rapidly advancing sequencing technologies, molecular markers offer a reliable and reproducible method for identification of tree species based on DNA sequences. To overcome the limitations of morphological markers to differentiate closely related species, we used matK and rbcL markers for efficient and reliable identification of Acacia species.

High quality DNA extracted from the fresh leaves of selected Acacia species was used as template and expected read lengths were amplified using gene specific primers. Successful DNA isolation discussed in this study, has been correlated with earlier studies Kumar et al., 2018, Hu et al., 2009. In addition, our results also support earlier studies that observed no variation in sequence length for rbcL, with successful PCR amplification and sequencing results (Kress et al., 2005, Roy et al., 2010) sometimes even with 100% success rate (Maia et al., 2012).

In contrast to rbcL, the success rate of amplification and sequencing of matK fragment was 57.24 ± 4.42% and 50.82 ± 4.36%, respectively. A similar study by Kress et al. (2009) reported that matK had the lowest overall rate of recovery (69%) in amplification and sequencing. Similarly, the success rate of amplification in Kress and Erickson (2007) was only 39.3% for 96 species and 46 genera. Sass et al. (2007) used matK to amplify Cycas, however, with a lower success rate of only 24%. The possible reason behind this low amplification with matK was that different features of the matK gene are difficult to amplify and sequencing with univerisal and shows poor results (Chase et al., 2007, Hollingsworth, 2008). Previously several researches have suggested that success rate of amplification with matK was highly variable, ranging from 40% to 97% (Zhang et al., 2012, Kress and Erickson, 2007). Therefore, universality of primers is recognized as an important criterion for evaluating the effectiveness of DNA barcodes (CBOL 2009).

The average AT nucleotide composition for rbcL of all selected species of Acacia was found higher to be 55.4% than GC content, 44.54%. Similarly, in matK, average AT contents (59.46%) were higher as compared to the GC contents (40.44%). Similar findings have been reported by Dhakad et al. (2017) who found higher AT content (55.7%) than GC content (44.2%) in Acacia sp. using rbcL. In addition, Wijayasiriwardene et al. (2017) also reported that nucleotide composition of AT was higher (68.98%) than GC (31.01%) contents for matK. The possible explanation of higher AT contents than GC contents in both markers could be due to high variability in nucleotide composition and higher nucleotide substitution rate in these genes.

Evaluation of intraspecific and interspecific divergence among species is a useful approach for assessing potential of DNA barcodes (Newmaster et al., 2008, Yu et al., 2014, Puillandre et al., 2012). The interspecific distances were calculated with K2P model utilizing pairwise comparison to trace evolutionary relationship between species. The K2P genetic distance between species summarized in (Table 4) showed that means genetic distance was higher (0.704%) in Acacia species using matK marker as compared to (0.04%) with rbcL. In a similar study, Nithaniyal et al. (2014). Nithaniyal et al. (2014) reported interspecific divergence range from 0.0 to 1.8% and 0.0 to 2.6% for rbcL and matK respectively. The poor interspecific divergence could be the result of frequent natural hybridization reported in Acacia species. Natural hybridization in Acacia’s is well documented and various hybrids with different ploidy levels have been identified in Acacia nilotica and Acacia senegal (Blakesley et al., 2002, Khatoon and Ali, 2006, Odee et al., 2015).

DNA barcode is a short DNA sequence based system specialized for one or more loci which can be used as a complementary unit for precise identification (Kress and Erickson, 2007). In our study, we propose to develop barcodes for proper identification of Acacia species; thereby a phylogenic tree based approach was also used for validation of DNA barcodes obtained through SNPs analysis. Our results revealed that rbcL and matK generated strong barcodes for the proper identification of tested Acacia species. In phylogenetic analysis based on rbcL sequences A. albida, A. coriacea and A. tortilis were distantly related and clearly differentiated from each other as compared to A. catechu (Fig. 4). However, differentiation between A. catechu and A. ampliceps was poorly resolved thus required more markers for their identification. In case of matK, A. coriacea and A. tortilis were closely related with each other whereas A. catechu, A. albida and A. ampliceps were clearly differentiated in a barcode tree (Fig. 5). Phylogenetic relationship between different Acacia species was also generated using both matK and rbcl genetic markers. In combined analysis using both markers, A. coriacea and A. tortilis were closely related as compared to the A. ampliceps, and A. albida and A. catechu were also grouped together thus closely related to each other. Finally, DNA sequences based QR codes were developed, which were scannable with smartphone applications, similar to barcode scanner in supermarkets. Researchers have developed similar barcodes for different species. For example, Bhagwat et al. (2015) reported the suitability of matK and rbcL markers for generating a barcode and differentiation of Dalbergia species. Similarly, Li et al. (2011) also generated the barcode for Aquilaria species. Most of the genomes have been sequenced, so molecular approaches based on DNA sequences may help in efficient and reproducible identification of tree species. In the past, morphological characters were utilized for identification however morphological markers are not always reproducible and identifiable. Therefore, it is very difficult to identify the species on the basis of visible morphological characters that are almost intisdiguishable from each other. Rapid developments in technology, bioinformatic tools, next generation sequencing and availability of genome sequences for most of species, have imparted more power for species identification using DNA sequence based markers. The rbcL has low resolution and high universality while, in contrast, matK has high resolution and low universality among the different species. Therefore, using both matK and rbcL genetic regions, may help to discriminate Acacia species. 5.

Conclusions

The molecular assay performed through both selected DNA markers rbcL and matK provided reproducible results. Both DNA markers (rbcL and matK) were utilized effectively, to develop DNA barcodes for Acacia species. The molecular characterization using rbcL and matK markers, can be utilized to tag more SNPs based variations in different Acacia species.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This research was partially supported by Higher Education Commission, Islamabad, Pakistan under project NRPU-6350 to Dr Aftab Ahmad. Authors also thankful the support of the Research Center for Advanced Materials Science (RCAMS) at King Khalid University, Abha Saudi Arabia through a grant RCAMS/KKU/08-20. We thank our colleagues from cotton Biotechnology Laboratory for their assistance in research.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Asif M.J., Cannon C.H. DNA extraction from processed wood: a case study for the identification of an endangered timber species (Gonystylus bancanus) Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2005;23(2):185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat R.M., Dholakia B.B., Kadoo N.Y., Balasundaran M., Gupta V.S. Two new potential barcodes to discriminate Dalbergia species. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakesley D., Allen A., Pellny T.K., Roberts A.V. Natural and induced polyploidy in Acacia dealbata Link. and Acacia mangium Willd. Ann. Bot. 2002;90(3):391–398. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBOL Plant Wording Group, 2009. DNA barcode for land plants. PNAS 106, 12794–12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chase M.W., Cowan R.S., Hollingsworth P.M., van den Berg C., Madriñán S., Petersen G., Pedersen N. A proposal for a standardized protocol to barcode all land plants. Taxon. 2007;56(2):295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Yao H., Han J., Liu C., Song J., Shi L., Luo K. Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakad A.K., Chandra A., Barthwal S., Thakur A., Rawat J.M. Analysis of phylogeny and evolutionary divergence of Acacia catechu (L. f.) Willd. based on rbcL conserved sequence. Syst. Bot. 2017;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- Fazekas A.J., Burgess K.S., Kesanakurti P.R., Graham S.W., Newmaster S.G., Husband B.C., Barrett S.C. Multiple multilocus DNA barcodes from the plastid genome discriminate plant species equally well. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group CPW, Hollingsworth, P.M., Forrest, L.L., Spouge, J.L., Hajibabaei, M., Ratnasingham, S., Fazekas, A.J., 2009. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106(31), 12794–12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hebert P.D., Ratnasingham S., De Waard J.R. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003;270(suppl_1):S96–S99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth P. DNA barcoding plants in biodiversity hot spots: Progress and outstanding questions. Heredity. 2008;101:1–2. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth P.M., Forrest L.L., Spouge J.L., Hajibabaei M., Ratnasingham S. A DNA barcode for land plants. PNAS. 2009;106:12794–12797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905845106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Chen Y., Lin L.S., Lin S.Z. Fast Extraction of Genome DNA from Acacia melanoxylon. J. Huaqiao Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2009;1 [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon S., Ali S.I. Chromosome numbers and polyploidy in the legumes of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2006;38(4):935. [Google Scholar]

- Kress W.J., Erickson D.L. A two-locus global DNA barcode for land plants: the coding rbcL gene complements the non-coding trnH-psbA spacer region. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress W.J., Erickson D.L., Jones F.A., Swenson N.G., Perez R., Sanjur O., Bermingham E. Plant DNA barcodes and a community phylogeny of a tropical forest dynamics plot in Panama. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106(44):18621–18626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909820106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress W.J., Wurdack K.J., Zimmer E.A., Weigt L.A., Janzen D.H. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:8369–8374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503123102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D.A., Anup C., Santan B., Ajay T., Mishra R.J. DNA extraction and molecular characterization of Acacia pseudoeburnea–An endemic species. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2018;13:8. [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye R., Van der Bank M., Bogarin D., Warner J., Pupulin F., Gigot G., Savolainen V. DNA barcoding the floras of biodiversity hotspots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105(8):2923–2928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709936105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.-W., Kuo L.-Y., Rothfels C.J., Ebihara A., Chiou W.-L., Windham M.D., Pryer K.M. rbcL and matK earn two thumbs up as the core DNA barcode for ferns. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia V.H., Da Mata C.S., Franco L.O., Cardoso M.A., Cardoso S.R.S., Hemerly A.S., Ferreira P.C.G. DNA barcoding Bromeliaceae: achievements and pitfalls. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslin B.R., Miller J.T., Seigler D.S. Overview of the generic status of Acacia (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae) Aust. Syst. Bot. 2003;16(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley S.J., Turnbull J.W. Domestication and use of Australian Acacias: an overview. Aust. Syst. Bot. 2003;16(1):89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad A.J., Abdullah M.Z., Muhammad N., Ratnam W. Detecting mislabeling and identifying unique progeny in Acacia mapping population using SNP markers. J. Forestry Res. 2017;28(6):1119–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad A.J., Ong S.S., Ratnam W. Characterization of mean stem density, fibre length and lignin from two Acacia species and their hybrid. J. Forestry Res. 2018;29(2):549–555. [Google Scholar]

- Newmaster S.G., Fazekas A.J., Ragupathy S. DNA barcoding in land plants: evaluation of rbcL in a multigene tiered approach. Botany. 2006;84(3):335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Newmaster S.G., Fazekas A.J., Steeves R.A.D., Janovec J. Testing candidate plant barcode regions in the Myristicaceae. Mol. Eco. Resour. 2008;8(3):480–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithaniyal S., Newmaster S.G., Ragupathy S., Krishnamoorthy D., Vassou S.L., Parani M. DNA barcode authentication of wood samples of threatened and commercial timber trees within the tropical dry Evergreen Forest of India. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odee D.W., Wilson J., Omondi S., Perry A., Cavers S. Rangewide ploidy variation and evolution in Acacia senegal a north–south divide. AoB Plants. 2015;7 doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plv011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard A.E., Maslin B.R. Proposal to conserve the name Acacia (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae) with a conserved type. Taxon. 2003;52(2):362–363. [Google Scholar]

- Pettengill J.B., Neel M.C. An evaluation of candidate plant DNA barcodes and assignment methods in diagnosing 29 species in genus Agalinis (Orobanchaceae) Am. J. Bot. 2010;97(8):1391–1406. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puillandre N., Lambert A., Brouillet S., Achaz G. ABGD, Automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2012;21(8):1864–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

- Ratnasingham S., Hebert P.D. BOLD: the barcode of life data system (http://www. barcodinglife. org) Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2007;7(3):355-364. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Tyagi A., Shukla V., Kumar A., Singh U.M., Chaudhary L.B., Husain T. Universal plant DNA barcode loci may not work in complex groups: a case study with Indian Berberis species. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass C., Little D.P., Stevenson D.W., Specht C.D. DNA barcoding in the Cycadales: testing the potential of proposed barcoding markers for species identification of cycads. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven G, Newmaster, Subramanyam, R., 2009. Testing plant barcoding in a sister species complex of pantropical Acacia (Mimosoideae, Fabaceae). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 9, 172–180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wijayasiriwardene T.D.C.M.K., Herath H.M.I.C., Premakumara G.A.S. Identification of endemic Curcuma albiflora Thw. by DNA barcoding method. Sri Lankan. J. Biol. 2017;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Wu K., Song J., Zhu Y., Yao H., Luo K., Lin Y. Expedient identification of Magnoliaceae species by DNA barcoding. Plant Omics. 2014;7(1):47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.Y., Wang F.Y., Yan H.F., Hao G., Hu C.M., Ge X.J. Testing DNA barcoding in closely related groups of Lysimachia L (Myrsinaceae) Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2012;12(1):98–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]