Abstract

Objective

Sexual health is a key component of the overall health and quality of life of both men and women. Sexual dysfunction is a common condition, but it lacks professional recognition. This study aims to determine the prevalence and types of sexual dysfunctions among postpartum women in primary care clinics and their associated factors in a Malaysian cohort.

Method

In this cross-sectional study, we recruited 420 women from nine primary care clinics in Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia. All participants had given livebirths within six weeks to six months and had attended either a postnatal or a well-child clinic at a government primary care clinic. The assessment of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) was done using a validated Malay version of the female sexual function index (MVFSFI). Data were statistically analysed using appropriate methods.

Results

More than one-third (35.5%) of women had postpartum sexual dysfunction. The most common types were lubrication disorder 85.6% (n = 113), followed by loss of desire 69.7% (n = 92) and pain disorders 62.9% (n = 83). Satisfaction disorder 7.3% (n = 27), orgasmic disorder 9.7% (n = 56) and arousal disorder 11.0% (n = 41) were less common sexual problems. The independent associated factors for FSD were high education level (adjusted odd ratio = 1.717, 95% CI 1.036–2.844; p < 0.05) and usage of hormonal contraception (adjusted odd ratio = 0.582, 95% CI 0.355–0.954; p < 0.05).

Conclusion

This study showed a high prevalence of postpartum sexual dysfunction in Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia. The most common type of sexual dysfunction was lubrication disorder. Efforts at increasing awareness in healthcare professionals should be made.

Keywords: Child birth, Female sexual function index, Postpartum, Primary care, Sexual dysfunction

الملخص

أهداف البحث

تعتبر الصحة الجنسية عنصرا أساسيا في الصحة العامة وجودة الحياة عند كلا من الرجال والنساء. ويعتبر العجز الجنسي حالة شائعة ولكن تفتقر إلى الاهتمام المهني. تهدف هذه الدراسة لتحديد مدى انتشار العجز الجنسي ومعرفة أنواعه بين السيدات بعد الولادة في عيادات الرعاية الصحية الأولية والعوامل المتعلقة به في مجموعة ماليزية.

طرق البحث

في هذه الدراسة المقطعية، اخترنا ٤٢٠ سيدة من تسع عيادات للرعاية الصحية الأولية في كوانتان ماليزيا. جميع المشاركات كانت ولادتهن لأطفال أحياء خلال ستة أسابيع إلى ستة أشهر، وحضرن إلى عيادة ما بعد الولادة أو عيادة الطفل السليم في عيادات الرعاية الصحية الأولية الحكومية. تم تقييم العجز الجنسي لدى الإناث باستخدام مؤشر الوظيفة الجنسية للإناث النسخة الملاوية التي تم التحقق من مصداقيتها. كما تم تحليل المعلومات إحصائيا بالطرق المناسبة.

النتائج

وجد أن أكثر من ثلث السيدات (٣٥.٥٪) لديهن عجز جنسي بعد الولادة. وكان أكثر أنواع العجز شيوعا هو اضطراب الرطوبة ٨٥.٦٪ (العدد=١١٣)، ويليه الرغبة ٦٩.٧٪ (العدد=٩٢)، واضطرابات الألم ٦٢.٩٪ (العدد= ٨٣). كان اضطراب إشباع الرغبة ٧.٣٪ (العدد=٢٧)، واضطراب النشوة الجنسية ٩.٧٪ (العدد= ٥٦)، واضطراب الإثارة ١١٪ (العدد=٤١) هي أقل المشاكل الجنسية شيوعا. وكانت العوامل المستقلة المرتبطة بالعجز الجنسي لدى الإناث هي المستوى التعليمي العالي (النسبة الفردية المعدلة = ١.٧١٧، فاصل الثقة ٩٥٪ ١.٠٣٦- ٢.٨٤٤) واستخدام موانع الحمل الهرمونية (النسبة الفردية المعدلة = ٠.٥٨٢، فاصل الثقة ٩٥٪ ٠.٣٥٥- ٠.٩٥٤).

الاستنتاجات

أظهرت هذه الدراسة ارتفاع معدل انتشار العجز الجنسي بعد الولادة في كوانتان ماليزيا. وكان النوع الأكثر شيوعا من العجز الجنسي هو اضطراب الرطوبة. يجب أن تُستهدف الجهود نحو زيادة الوعي لدى متخصصي الرعاية الصحية.

الكلمات المفتاحية: ولادة الطفل, مؤشر الوظيفة الجنسية للإناث, بعد الولادة, الرعاية الصحية الأولية, العجز الجنسي

Introduction

Reproductive and sexual health is a key component of the overall health and quality of life of both men and women. Sexuality is a complex process, which is coordinated by the neurologic vascular and endocrine system. It incorporates familial, societal, and religious beliefs, and as a process, it alters with age, health status, and personal experience. Sexual health is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity; it is a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing in relation to sexuality.1

The female sexual response cycle is divided into four phases: desire, arousal, orgasm, and resolution. Disturbance in any of these phases results in sexual dysfunction.2 The 10th revision of the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems defined sexual dysfunction as people's inability to participate in sexual relationships as they wish.1 There are many factors which contribute to sexual dysfunction in women, including psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, stress, conflict within relationships and issues relating to physical or sexual abuse. Similarly, factors such as age and menopausal status, obesity, chronic medical conditions, and medications are also known to cause sexual dysfunction in women.3

Pregnancy and childbirth are also among the important factors, which have a significant impact on women's sexual health. Pregnancy and childbirth are major transitions in women's lives. They are challenged by intense psychological, physical, and sociocultural factors, which impact their sexual health and quality of life.3,4 Maintaining meaningful sexual activity after childbirth has been shown to be a key factor in preserving the quality of a couple's relationship.5

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is common, affecting 40–45% of women.5 Despite the high prevalence of FSD worldwide, there are very limited data concerning sexual dysfunction in postpartum women and its associated risk factors. There is a lack of professional awareness in recognising this condition, thus leaving it underexplored. It is important for healthcare professionals to recognise this problem at primary care level because effective basic treatment for most female sexual dysfunction can be successfully provided by primary care physicians.3 In Malaysia, two studies have been conducted on female sexual dysfunction (FSD), but none explored FSD among postpartum women.6,7 Therefore, further studies need to be done to evaluate sexual dysfunction among postpartum women, as they represent the majority of female patients seen in health clinics.

Sexual health after childbirth is a relatively new research area. Recent work has shown that sexual health problems are common in the postpartum period.8 Unfortunately, these problems lack professional recognition. Stigma is still a major barrier to people accessing sexual health services and many women regard this issue as a personal problem which should not be discussed openly.3 Understanding the magnitude of sexual difficulties in the postpartum period would enable physicians to explore this problem and offer effective treatment, even at the primary care level. Thus, this study was conducted to measure the prevalence of sexual dysfunction, determine the types of sexual dysfunction, and identify the associated factors with FSD among postpartum women in Kuantan.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in nine primary care clinics in Kuantan for 7 months, from February to August 2018. A total of 420 postpartum women were recruited randomly. The inclusion criteria were women aged 18 and above who had given livebirth within six weeks to six months of the study, were married and had a sexually active partner. Postpartum woman with a severe and chronic medical illness such as uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, a connective tissue disease, or a psychiatric condition were excluded from this study.

Study instruments

A self-administered questionnaire consisting of socio-demographic background and an MVFSFI questionnaire was used. Participation in this study was voluntary and reassurance was given on the strict confidentiality of the data collected.

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) is a validated, self-administered questionnaire for assessing female sexual dysfunction. It was originally developed by Rosen et al. in the US after a new definition of female sexual dysfunction was introduced by the International Consensus Development Conference on Female Sexual Dysfunction in 2000.9 FSFI has 19 items which cover six domains in female sexual dysfunction: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain disorders. It can differentiate sexual dysfunction with a Cronbach's alpha score of 0.82 or more for each domain.

The Malay version of FSFI was developed and validated by Sidi et al., in 2005.7 The questionnaire contains 19 questions for evaluating respondents' sexual function during their previous four weeks of activity. It has high sensitivity and specificity for reliably detecting female sexual dysfunction – 99% and 97% respectively, with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.8665 to 0.9675.

Similar to the original FSFI, it classifies sexual dysfunction into six domains: desire (two items), arousal (four items), lubrication (four items), orgasm (two items), satisfaction (four items), and sexual pain (three items). There are five to six options available for each item using a 5-point Likert scale. The respondents choose the most likely answer which shows their sexual functioning over the previous four weeks. The score for each question ranges from 0 to 5. The total score is 95 and respondents who score ≤55 are identified as having a sexual dysfunction. A cut-off point for each domain is also established to assess the specific type of sexual dysfunction.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS software version 22.0. Descriptive statistics were utilised to reflect the distribution of sexual dysfunction among the participants. Mean and standard deviation were computed for the continuous variables, while frequency and percentage were computed for the categorical variables. Based on the MVFSFI score, women were classified as at high risk of sexual dysfunction or not at high risk of sexual dysfunction. A chi-squared analysis was used to test the associations between the sociodemographic and postpartum variables and sexual dysfunction. A factor was said to be statistically significant if p = <0.05. A stepwise binary logistic regression with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to assess the parameters, which were considered as predictors of FSD.

Results

There was a response rate of 88.6%, as 48 respondents did not complete the questionnaire out of a total of 420 respondents recruited. Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the respondents (n = 372).

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 30 (5.42)∗ | |

| Race | Malay | 342 (91.9%) |

| Non-Malay | 30 (8.1%) | |

| Education level | Secondary or lower | 209 (56.2%) |

| Tertiary or above | 163 (43.8%) | |

| Household income | B40 and below | 253 (68%) |

| M40 and above | 119 (32%) | |

| Parity | 2 (2)∗∗ | |

| Duration of marriage (year) | 5 (6)∗∗ | |

| Mode of delivery | Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 276 (74.2%) |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 12 (3.2%) | |

| Caesarean section | 84 (22.6%) | |

| Feeding methods | Breastfeeding | 197 (53%) |

| Formula feeding | 123 (33%) | |

| Mixed feeding | 52 (14%) | |

| Contraceptive methods | No | 38 (10.2%) |

| Yes | 334 (89.8%) | |

| Types of contraception | Non-hormonal | 150 (45%) |

| Hormonal | 184 (55%) |

∗mean (SD) ∗∗median (IQR).

Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among postpartum women

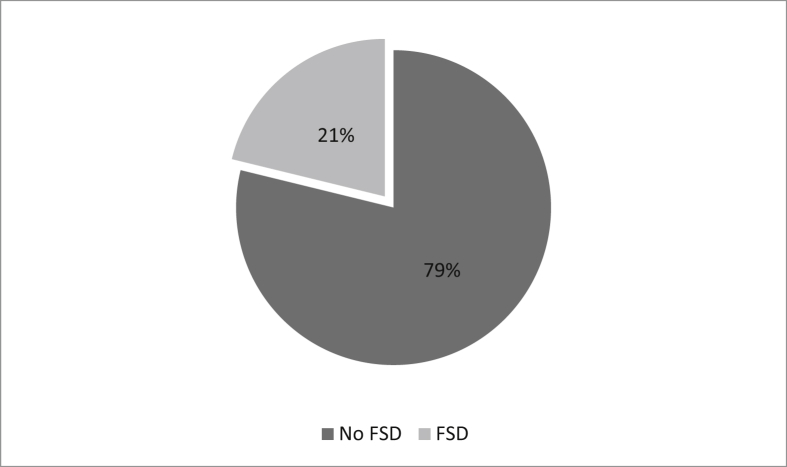

The prevalence of postpartum sexual dysfunction among postpartum women at primary care clinics in Kuantan, Pahang, was 35.5%, reflecting 132 of 372 respondents scoring ≤55 on the MVFSFI (see Figure. 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among postpartum women in primary care clinics in Kuantan, Pahang.

Types of female sexual dysfunction in the postpartum period

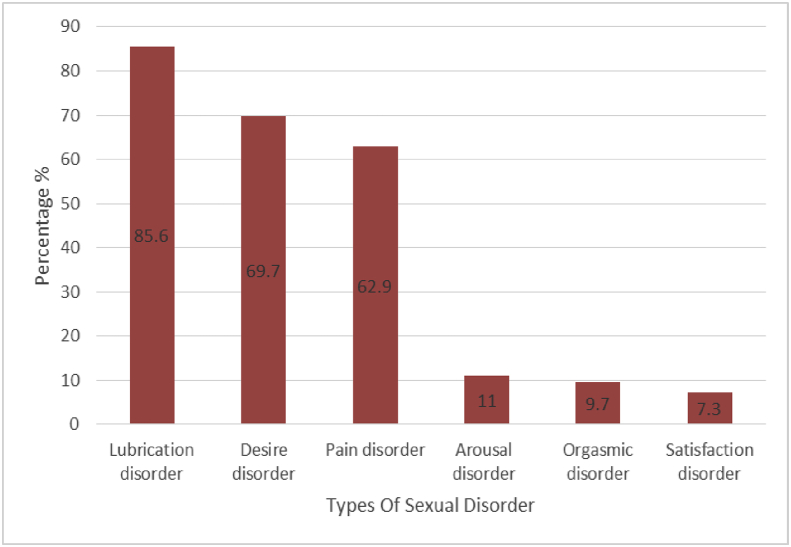

Figure 2 shows that the most common type of sexual dysfunction among postpartum women in Kuantan was lubrication disorder, at 85.6% (n = 113), followed by desire disorder, at 69.7% (n = 92), and pain disorder, at 62.9% (n = 83). Satisfaction disorder at 7.3% (n = 27), orgasmic disorder at 9.7% (n = 56), and arousal disorder at 11.0% (n = 41), were less common sexual problems reported.

Figure 2.

Types of postpartum sexual dysfunction in primary care clinics in Kuantan, Pahang.

Associated factors of female sexual dysfunction among postpartum women

Table 2 shows a multivariate logistic regression model. These results were positively associated with level of education and types of contraception used during the postpartum period. Women with higher education who, at a minimum, went to college for a higher education had a 72% increased risk of developing postpartum sexual dysfunction compared to those with a lower education (95% CI 1.03, 2.84). In addition, women who practised non-hormonal contraception were 42% more protected against having postpartum sexual dysfunction compared to those with hormonal contraception (95% CI 0.35, 0.95).

Table 2.

Associated factors of sexual dysfunction among post-partum women in primary care clinics in Kuantan, Pahang.

| Variable | FSD |

Non FSD |

aOR | 95% CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) or % | n | Mean (SD) or % | lower | upper | ||

| Age (year) | 132 | 29.9 (5.28) | 240 | 30.4 (5.50) | 0.996 | 0.944 | 1.050 |

| Race | |||||||

| Malay | 120 | 35.1 | 222 | 64.9 | 1.000 | ||

| Non-Malay | 12 | 40.0 | 18 | 60.0 | 1.633 | 0.719 | 3.711 |

| Education level | |||||||

| Secondary or lower | 64 | 30.6 | 145 | 69.4 | 1.000 | ||

| Tertiary or above | 68 | 41.7 | 95 | 58.3 | 1.717 | 1.036 | 2.844 |

| Household income | |||||||

| B40 and below | 88 | 34.8 | 165 | 65.2 | 1.000 | ||

| M40 and above | 44 | 37.0 | 75 | 63.0 | 0.921 | 0.533 | 1.592 |

| Parity | |||||||

| Para 1 | 43 | 41.3 | 61 | 58.7 | 1.000 | ||

| Para 2 or more | 89 | 33.2 | 179 | 66.8 | 0.776 | 0.406 | 1.486 |

| Duration of marriage | |||||||

| <5 years | 60 | 38.0 | 98 | 62.0 | 1.000 | ||

| ≥5 years | 72 | 33.6 | 142 | 66.4 | 0.717 | 1.036 | 2.844 |

| Mode of delivery | |||||||

| SVD | 98 | 35.5 | 178 | 64.5 | 1.000 | ||

| Operative vaginal delivery | 5 | 41.7 | 7 | 58.3 | 1.438 | 0.409 | 5.055 |

| Caesarean section | 29 | 34.5 | 55 | 65.5 | 1.032 | 0.591 | 1.801 |

| Feeding methods | |||||||

| Breastfeeding | 74 | 37.6 | 123 | 62.4 | 1.000 | ||

| Formula feeding | 45 | 36.6 | 78 | 63.4 | 0.915 | 0.565 | 1.483 |

| Mixed feeding | 13 | 25.0 | 39 | 75.0 | 0.560 | 0.270 | 1.160 |

| Contraceptive methods | |||||||

| Hormonal | 71 | 38.6 | 113 | 61.4 | 1.000 | ||

| Non-hormonal | 42 | 28 | 108 | 72 | 0.582 | 0.355 | 0.954 |

| Not on contraception | 19 | 50 | 19 | 50 | 1.480 | 0.716 | 3.058 |

Bold:p < 0.05, aOR = adjusted odd ratio, SVD = spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Discussion

Sexual dysfunction reflects a chain of psychiatric experiences of individuals and couples, which emerges as a problem or dysfunction of sexual desire, sexual arousal or orgasm, or pain during intercourse.3 Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is highly prevalent globally, with its occurrence estimated at about 30% in Asian countries.10 Many researchers are investigating the local magnitude of this problem since there are variations in populations and sociocultural backgrounds in different parts of the world. Unlike male sexual dysfunction, the availability of data is scant, especially from postpartum women, who represent the majority of sexually active women.

The prevalence of FSD among postpartum women in primary care clinics in Kuantan, Pahang, was estimated to be 35.5%, which is comparable with other studies conducted in primary care settings in Malaysia. In studies conducted at primary care clinics in urban areas, the prevalence of FSD among the general population was between 25.8% and 29.6%%.6,7 Similarly, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in this study is also in accordance with the estimation of 22%–50% of women experiencing postpartum sexual dysfunction worldwide.4

It is interesting to note that the prevalence in the Malaysian population is comparable with the prevalence of FSD found in its neighbouring country, Thailand, which has been estimated at 30%.11 This can be attributed to the sociodemographic similarities of the respondents and the culture practised in this region.

On the other hand, in developed countries such as Australia and Japan, the prevalence of FSD is higher. For instance, among Australian women one year after childbirth, it is almost double, at 64%.12 In Japan, 91% of postpartum mothers experienced sexual dysfunction.13 These discrepancies might be due to the different sociodemographic backgrounds of the respondents, different cultural factors and belief systems, and different sampling methods and localities. In addition, it is interesting to note that the prevalence of FSD is much lower in developing countries compared to developed ones, possibly because women in developed countries are more open to talking about sexuality.

Lubrication disorder (113, 85%) was the most common sexual dysfunction experienced among the respondents, followed by desire disorder (69.7%) and pain disorder (62.9%). There are many factors which contribute to low lubrication, especially during the first six months after childbirth. One of the known factors is the hypoestrogenic state, induced by the high prolactin level in breastfeeding women, which leads to vaginal dryness and low sexual desire.14,15 This holds true in this study, as 90% of the respondents breastfeed their babies. Our findings are similar to a study in Japan and Brazil, where the majority of postpartum women had a lubrication disorder, apart from an arousal and orgasm disorder.13,16

For women with a lubrication disorder, an in-depth interview would be valuable for assessment. Treatment can range from pharmacological to non-pharmacological products. Psychological treatment includes sensate focus exercises and masturbation training, while the use of hormones such as estradiol has also been mentioned for treatment.17

Unlike our findings, other studies have highlighted desire, arousal and orgasm as the most common sexual problems encountered during the postpartum period. In Khajehei's study of 325 Australian women who had given birth within one year, it was reported that sexual desire disorder was the most common (81.2%) sexual problem, followed by orgasmic problems (53.5%) and sexual arousal disorder (52.3%).12 This is similar to the findings of Hanafy et al., where they also showed that desire and orgasmic disorders were the most prominent sexual problems during the postpartum period.18 The reason for this difference could be due to the duration of postpartum for the respondents in these studies.

Studies conducted in Egypt and Australia recruited women who had given livebirths within one year, whereas our study comprised only those who had delivered within 6 months at the time of the survey. The first six months after delivery can have a profound impact on a woman's sexual quality of life. A review done by Yeniel et al. concluded that the resumption of sexual activity increases with the passage of time in the postpartum period.19

Desire disorder is invariably among the most frequent sexual dysfunctions reported by women. This finding is in line with many other studies which have found desire disorder to be the most affected sexual domain during the postpartum period.13,18 In a study which focused specifically on women's sexual desire after childbirth, the most significant factors which led to low sexual desire during postpartum were found to be fatigue and vaginal discomfort.14 However, this correlation could not be established in our study; thus, further research is needed to clarify this association.

The third highest sexual dysfunction found in this study was pain disorder (62.9%). This finding is consistent with many other surveys which have examined female sexuality during the postpartum period.11,14 Dyspareunia is extremely common, especially within six months of postpartum.14 This timeframe is a critical reason why our findings differ from similar studies on postpartum sexual dysfunction in Australia, Egypt, Japan and Thailand, as they included women within one year of postpartum.

The least affected sexual domains in our study were arousal, orgasmic and satisfaction disorder, which were 11%, 9.7% and 7.3% respectively. There is a significant difference between the number of women who suffered from the top three domains of sexual dysfunction stated earlier – between 62% and 85% – compared to arousal, orgasmic and satisfaction disorders, which accounted for only about 10%.

The underlying factor for this huge difference is probably due to the sociocultural and religious influence on sexuality in the study population. Generally, Asians are known to have more conservative views on sex. Asians are more likely to perceive sex as procreative, an act to produce offspring, which should be kept within the family context. Westerners, on the other hand, view sex as recreational, a source of pleasure and intimacy.10

Furthermore, religious values which discourage women to openly disclose their sexual issues except for treatment purposes is an important factor contributing to this finding in our local setting, where most of the respondents are Malays and Muslims. The marked discrepancy between these sexual domains suggest that these findings may not reflect the true occurrence in our community, as many other studies have demonstrated the relation between vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, low sexual desire, and inability to achieve orgasm.13

Despite the high occurrence of low sexual desire, lack of lubrication, and dyspareunia in postpartum women, sexual satisfaction was not affected. Satisfaction was the least reported sexual dysfunction within six months of postpartum in our survey. This is because sexual dysfunction is not related to sexual satisfaction in a relationship. Couples who are happy with each other and enjoy mutual support and understanding have higher satisfaction and less sexual dysfunction in their relationships.21

Nevertheless, our study found a significant association between education level and sexual dysfunction (p = 0.04). Those with a higher education (tertiary education or higher) had a 72% increased risk of developing FSD (aOR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.01 to 2.81). This finding is similar to that of a study conducted in Japan.7,13

On the other hand, Australia and Thailand have shown no association between educational status and risk of sexual dysfunction.11,12 This suggests that higher educational status may lead to increased awareness of women's sexual needs; thus, they are more open about expressing their sexual difficulties. Women with higher education and literacy skills have the ability to access health information and more effectively navigate health systems.23

The findings in our study also show that women who used non-hormonal contraception such as male condoms, intrauterine device systems (IUCDs), and bilateral tubal ligation had 42% more protection from developing sexual dysfunction compared with women who used hormonal contraception, contradicting other studies.12,13 A systematic review conducted in 2017 found that hormonal contraception, particularly oral contraceptive pills, could cause FSD in reproductive women, affecting mainly the desire, arousal, and pain disorder domains.22

This can be explained by the fact that usage of hormonal contraception decreases free testosterone. Androgen is known to play an important role in female sexual desire and libido. However, the mode of action is still unknown and not fully understood.23 Nevertheless, a review done in 2019 found that hormonal contraceptives have a contradictory effect on sexual dysfunction.24 Newer hormonal contraception, such as the patch and the levonorgestrel (LNg) intrauterine device, have been documented to have less effect on sexual desire.24

Nonetheless, our study found no significant association between FSD and age, parity, mode of delivery or duration of marriage. This is similar to the findings of Saotome et al.13 However, a review done by Yeniel and Petri in 2013 revealed that studies on mode of delivery affecting female sexual dysfunction were inconclusive.19

Caesarean delivery has been speculated to protect sexual function in women based on the preservation of pudendal nerve injury.25 The long-term effect of pudendal nerve neuropathy is still unclear, but the nerve usually recovers within six months.25 The influences of episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery were also found to be unclear. Meanwhile, another meta-analysis in 2017 indicated that the mode of delivery, whether caesarean or vaginal, did not affect sexual function and satisfaction.20

Limitations and strengths of the study

There are several limitations in this study. The respondents were predominantly Malay, at 92%, while the remaining 8% consisted of Chinese, Indian, and other ethnicities. This composition does not reflect the true ethnic distribution in Kuantan, Pahang. Thus, the findings in this study may not reflect the real ethnic situation in our community.

In addition, some features of the study design precluded the analysis of certain factors which may affect or explain sexual function. For example, our study did not include perineal birth trauma or birth complication since the data collected were based on respondents’ recall and an antenatal book giving limited information on their birth event.

However, since this study was conducted in nine primary care clinics in Kuantan, the results reflect the magnitude of postpartum sexual dysfunction in our local community. For future studies, we hope to expand the scope of the study to assess the relationship of postpartum sexual dysfunction and sexual behaviour in women and their partners.

Conclusion and recommendations

In conclusion, this study has shown that the prevalence of postpartum sexual dysfunction within six months of postpartum in Kuantan is high (35.5%). In addition, this study also found that women with a higher level of education who use hormonal contraceptives are at higher risk of developing FSD.

Therefore, it is important for healthcare professionals to be aware of these statistics and be involved in assessing sexual concerns among postpartum women under their care. Women should also be encouraged to share their sexual concerns with their doctors in order for proper assessments and interventions to be carried out.

Source of funding

This work was supported by the International Islamic University Malaysia Research Grant Initiatives [grant numbers: RIGS17-061-0636].

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research and Ethical Committee of the researchers’ institution (IREC 569) and the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (NMRR-15-2206- 28605,23-01-2018). All respondents gave their written consent. Those who declined to participate received a similar standard care of treatment as those who agreed to participate.

Authors contributions

NAJ and KHAA conceived and designed the study, NNK conducted the research, provided the research materials, and collected and organised the data. KHAA and NNK analysed the data. KHAA, ND and NAJ interpreted the data. NAJ and KHAA wrote the initial and final draft of the article, and provided logistic support. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this research work, participating health clinic staffs and respondents. The authors would also like to thank International Islamic University Malaysia for funding this research (RIGS17-061-0636). We also would like to thank Dr Siti Atiqah Khaled for her help in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2006. Defining sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28-31 January 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright J.J., O Connor K.M. Female sexual dysfunction. Med Clin N Am. 2015;(3):607–628. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvatore S., Redaelli A., Baini I., Candiani M. Childbirth-related pelvic floor dysfunction: risk factors, prevention, evaluation, and treatment. Springer International Publishing; 2016. Sexual function after delivery; pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torkzahrani S., Banaei M., Ozgoli G., Azad M., Emamhadi M. Postpartum sexual function; conflict in marriage stability: a systematic review. Int J Med Toxicol Forensic Med. 2016;6(2):88–98. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abidin A., Draman N., Ismail S.B., Mustaffa I., Ahmad I. Female sexual dysfunction among overweight and obese women in Kota Bharu , Malaysia. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2016;11(2):159–167. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidi H., Puteh S.E., Abdullah N., Midin M. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction and potential risk factors that may impair sexual function in Malaysia women. J Sex Med. 2007;4(2):311–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yıldız H. The relation between prepregnancy sexuality and sexual function during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a prospective study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41(1):49–59. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2013.811452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basson R., Berman J., Burnett A., Derogatis L., Ferguson D., Fourcroy J. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163(3):888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shivanand Manohar J., Solunke Hrishikesh, Suhruth Reddy K., Raman Rajesh, Kalra Gurvinder, Tandon Abhinav. Sexual disorders in Asians. Journal of Psychosexual Health. 2019:222–226. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chayachinda C., Titapant V., Ungkanungdecha A. Dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction after vaginal delivery in Thai primiparous women with episiotomy. J Sex Med. 2015;12(5):1275–1282. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khajehei M., Doherty M., Tilley P.J., Sauer K. Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in postpartum Australian women. J Sex Med. 2015;12(6):1415–1426. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saotome T.T., Yonezawa K., Suganuma N. Sexual dysfunction and satisfaction in Japanese couples during pregnancy and postpartum. Sex Med. 2018:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alligood-Percoco N.R., Kjerulff K.H., Repke J.T. Risk factors for dyspareunia after first childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):512–518. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald E., Woolhouse H., Brown S.J. Consultation about sexual health issues in the year after childbirth: a cohort study. Birth. 2015;42(4):354–361. doi: 10.1111/birt.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuentealba-Torres M., Cartagena-Ramos D., Fronteira I., Lara L.A., Arroyo L.H., Arcovere M.A.M. What are the prevalence and factors associated with sexual dysfunction in breastfeeding women? A Brazilian cross-sectional analytical study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wierman M.E., Arlt W., Basson R., Davis S.R., Miller K.K., Murad M.H. Androgen therapy in women: a reappraisal: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3489–3510. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanafy S., El-Esawy F. Female sexual dysfunction during the postpartum period: an Egyptian study. Hum Androl. 2015;5(4):71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeniel A.O., Petri E. Pregnancy, childbirth, and sexual function: perceptions and facts. Int UrogynEcol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2014;25(1):5–14. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan D., Li S., Wang W., Tian G., Liu L., Wu S. Sexual dysfunction and mode of delivery in Chinese primiparous women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):408. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1583-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam Y., Broaddus E.T., Surkan P.J. Literacy and healthcare-seeking among women with low educational attainment: analysis of cross-sectional data from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:95. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J.J., Tan T.C., Ang S.B. Female sexual dysfunction with combined oral contraceptive use. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(6):285–288. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2017048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith N.K., Jozkowski K.N., Sanders S.A. Hormonal contraception and female pain, orgasm and sexual pleasure. J Sex Med. 2014;11(2):462–470. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casado-Espada N.M., de Alarcón R., de la Iglesia-Larrad J.I., Bote-Bonaechea B., Montejo Á.L. Hormonal contraceptives, female sexual dysfunction, and managing strategies: a review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):908. doi: 10.3390/jcm8060908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mousavi S.A., Mortazavi, Chaman R., Khosravi A. Quality of life after cesarean and vaginal delivery. Oman Med J. 2013;28(4):245–251. doi: 10.5001/omj.2013.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]