Abstract

Introduction:

A wide variety of non-invasive treatments has been proposed for the management of hypertrophic burn scars. Unfortunately, the reported efficacy has not been consistent, and especially in the first three months after wound closure, fragility of the scarred skin limits the treatment options. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is a new non-invasive type of mechanotherapy to treat wounds and scars. The aim of the present study was to examine the objective and subjective scar-related effects of ESWT on burn scars in the early remodelling phase.

Material and methods:

Evaluations included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) for scar quality, tri-stimulus colorimetry for redness, tewametry for trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) and cutometry for elasticity. Patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups, the low-energy intervention group or the placebo control group, and were tested at baseline, after one, three and six months. All patients were treated with pressure garments, silicone and moisturisers. Both groups received the ESWT treatment (real or placebo) once a week for 10 weeks.

Results:

Results for 20 patients in each group after six months are presented. The objective assessments showed a statistically significant effect of ESWT compared with placebo on elasticity (P = 0.011, η2P=0.107) but revealed no significant effects on redness and TEWL. Results of the clinical assessments showed no significant interactions between intervention and time for the POSAS Patient and Observer scores.

Conclusion:

ESWT can give added value to the non-invasive treatment of hypertrophic scars, more specifically to improve elasticity when the treatment was already started in the first three months after wound closure.

Lay Summary

Pathological scarring is a common problem after a burn injury. A wide variety of non-invasive treatments has been proposed for the management of these scars. Unfortunately, the reported efficacy of these interventions has not been consistent, and especially in the first three months after wound closure, fragility of the scarred skin limits the treatment options. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is a relatively new non-invasive therapy to treat both wounds and scars. The aim of the present study was to examine the scar-related effects of ESWT on burn scars in the early phase of healing.

The scars were subjectively assessed for scar quality by the patient and an observer using the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS). Objective assessments included measurements to assess redness, water loss and elasticity. Forty patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups, the low-energy intervention group or the placebo control group (the device simulated the sound of an ESWT treatment but no real shocks were applied), and were tested at four timepoints up to six months. All patients were treated with pressure garments, silicone and moisturisers. Both groups received the ESWT treatment (real or placebo) once a week for 10 weeks.

The objective assessments showed a significant improvement of elasticity in the intervention group when compared with placebo but revealed no significant effects on redness and water loss. Results of the clinical assessments showed no differences between the groups for the POSAS Patient and Observer scores.

ESWT can give added value to the non-invasive treatment of pathological scars more specifically to improve elasticity in the early phase of healing.

Keywords: Extracorporeal shock wave therapy, hypertrophic scar, mechanotransduction, elasticity, low-energy shock waves, non-invasive treatment, scar management

Introduction

The development of hypertrophic scarring is a common problem after a burn injury or other complex and/or prolonged wound healing conditions. A hypertrophic scar is characterised by red, raised and firm scar tissue that contracts and limits normal movement of the skin. It is also associated with other physical and psychological consequences such as limited range of motion, increased pain sensation, pruritus, elevated anxiety levels and lowered health-related quality.1–3

Physiotherapy plays an important role in scar treatment and includes scar massage, exercise therapy, joint mobilisation, cardiopulmonary training, positioning, splinting and topical scar management.2,4 Unfortunately, the reported efficacy has not been consistent, with contradictory results for scar massage5,6 and splinting, for example.7–9

However, in the early phase of scar remodelling during the first months after wound closure, fragility of scarred skin could limit the treatment options. Therefore, extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is promising as a non-invasive type of physical intervention to treat scars. Non-randomised clinical data suggest that ESWT is beneficial in terms of improved skin elasticity and revitalising dermis in women with cellulite.10 Fibrillar adipose tissue fibrosis looks very similar to dermal scarring,11 so the outcomes of clinical trials investigating cellulite may be transferred to pathological scarring.12 Previous research has established positive effects of ESWT on scars. In a pre-post study of ESWT for postburn scar contractures, hypertrophic scars and keloids became less painful, less stiff and thinner with more similar scar colour to the surrounding skin and more acceptable appearance.13 In a prospective, single-blind, placebo-controlled study, a significant reduction of scar pain in burn patients was observed in favour of the patient treated with ESWT.14 In another randomised clinical trial, ESWT was found to be effective for the treatment of painful, retracting scars of the hands. The subjective clinical appearance of scars, the motion function of the underlying joints and the subjective pain improved significantly.15 All of these studies applied low-energy ESWT with a total energy for each impulse in the range of 0.15–0.37 mJ/mm2. But so far, in the published studies on the effects of ESWT on scars, the only objectively measured scar-related outcome parameter was blood perfusion.16

In this study, we aim to examine both the objective and subjective scar related outcomes of low-energy ESWT on burn scars in the early phase of scar remodelling. This study has a randomized double blinded design with an objective assessment of elasticity in addition to the use of subjective scar scales.

Material and methods

Study design

This study was a prospective, randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled, single-centre trial. Data was collected between September 2013 and November 2016 at our organization for burns, scar after-care & research (Oscare, Antwerp, Belgium). Patients were randomly assigned to one of 2 groups: the low-energy ESWT group or the placebo ESWT group. Details of the allocated group were given on cards contained in sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. The patients in both groups were also given standard treatment. This consisted of pressure therapy, the use of silicone and physical therapy, such as manual mobilization techniques and scar massage, as prescribed by the treating physician. Patients of the low-energy ESWT group were additionally treated with a Duolith® SD1 shock wave device. The other patients received a placebo ESWT treatment using a foam-filled placebo shock wave treatment head that did not generate any output. Both the patients and assessors were blinded to treatment allocation.

Study population

To be included, patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: age ⩾ 18 years; split thickness grafted or spontaneously healed burn scares after complete wound closure; and full wound closer obtained less than six months before the baseline assessment.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: central neurological diseases; peripheral paralysis; pacemaker; coagulation disorders; medication use of anticoagulants (e.g. Marcumar®); thrombosis; tumour; previously received shock wave therapy for wound closure; cortisone therapy up to six weeks before the first treatment; and pregnancy.

Patients have agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of ZNA Antwerp 009 OG.031 (E.C. approval n° 4200).

Intervention

Patients of the ESWT group were treated with the Duolith®-SD1 T-Top from Storz® Medical (Figure 1). The C-Actor handpiece with stand-off device II with 10 mm depth of focus zone was used17 (Figure 2). For the patients in the placebo group, a foam-filled placebo handpiece was used, which sounded like real shocks but did not allow shocks to pass through.

Figure 1.

Duolith®-SD1 T-Top ESWT device.

Figure 2.

The C-Actor handpiece with stand-off device II with 10 mm depth of focus zone.

The scar site was prepared with contact gel to conduct the shock waves. All scars were treated for 10 weeks with ESWT or placebo, one treatment/week, 30–50 shocks/cm², with an energy flux density of 0.25 mJ/mm² and a frequency of 6 Hz.

Measurement procedure, measurement tools and outcome measures

To acclimatise and to stabilise cutaneous blood flow, all patients were asked to enter the testing room at least 15 min before measurements were started and to remove pressure garments and silicone. The temperature and the humidity in the test room were registered using a thermometer and a hygrometer.

The scar site to be measured was placed in a horizontal position. All measurements on the hand or forearm were taken in a sitting position with the forearm lying on the table. Measurements on the upper arm, the trunk and the anterior side of the legs were done with the patient in supine position. The measurements on the back and posterior side of the legs were performed in the prone position. Measurements on the contralateral limb or adjacent healthy skin were performed for comparison. The various test sites were precisely marked using a standard circular patch (diameter = 30 mm) and written in the patient chart. Digital photographs were taken to ensure standardisation of location of the measurements over time.

Patients in both groups were measured at baseline (T0), after one (T1), three (T2) and six months (T3) each time before the treatment. After the period of 10 weeks of application of ESWT, the remaining treatment consisted only of standard of care for both groups.

All scars were subjectively assessed using the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale V2.0 (POSAS)18 and objectively assessed for colour, transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and vertical elasticity. The colour was measured using a Minolta Chromameter® CR-400 (Konica Minolta Sensing Inc., Osaka, Japan). The Chromameter® is a tristimulus colorimeter using the L*a*b* colour system, of which we analysed two of three components: L* (color brightness) and a* (level of red component).19 For TEWL, we used the DermaLab Skin Testing® (expressed in g/m²/h).20 The vertical elasticity or extensibility (the ability of skin to stretch, calculated by lifting a fold of skin in the direction perpendicular to the skin surface) was objectively measured using the Cutometer®21 (Courage & Khazaka GmbH, Cologne, Germany). The R0 value represents the vertical deformation of the skin in millimetres when that skin is lifted by means of a predetermined vacuum suction force into the circular aperture of a probe, 6 mm in diameter.21

The choice for colour and TEWL can be explained by the evolutive character of the scars in our population. Since redness and TEWL are parameters that tend to decrease over time up to maturation,3,22 this seemed the best choice. Elasticity is one of the most important features in scar assessment. It represents the reduced extensibility of the collagen fibre network and quantifies mechanical tension on scarred skin. This inextensibility may manifest itself by limiting joint mobility in the patients with hypertrophic scars. High scar grading is synonymous with increased stiffness and decreased extensibility.23

As a primary outcome parameter, the change in vertical elasticity, measured objectively with Cutometer® after six months compared to baseline, was chosen. This choice was based on the lack of objective elasticity measurements in literature and the importance of scar pliability in restoring function. The objective assessment of scar colour with the Chromameter®, TEWL with DermaLab® skin testing and the subjective assessment of the scars with the POSAS were the secondary outcome parameters.

Sample size calculation

To detect a change with an effect size of at least 0.8 (Cohen’s d), with a two-sided 5% significance with an 80% power a sample size of 20 participants per group was calculated. An estimated drop-out rate of 5% was taken into account for this calculation.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed for age, scar age (time since complete wound closure), gender, aetiology and anatomical location. An intention-to-treat analysis with the last observation carried forward was applied. Sensitivity analyses were carried out to detect significant differences between the analysis with or without the missing data. A two-way mixed ANOVA, with the intervention being the between-subjects factor and time + scar parameter being the within-subjects factor, was carried out.

The dataset was tested for outliers and normal distribution (tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test and histogram). The outliers were kept if they had no significant influence on the results and were removed if a significant difference between the results with or without outliers could be detected. If the assumption of normality was violated, a data transformation with SQRT or LOG10 was applied. The homogeneity of variances and co-variances were tested and discussed.

When the assumption of sphericity was violated, a Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied. When the dataset showed significant non-equality of baseline values, a baseline correction was applied with ANCOVA.

The Bonferroni post hoc test with pairwise comparisons was used to determine statistically significant differences between the different timepoints. Estimates of effect size were also reported.

Results

Patient and scar-related characteristics

Forty-two patients agreed to participate in this study. Forty patients completed the study. Two patients dropped out; one due to illness and one did not attend the first follow-up. This resulted in an equal number in each study group. Patient and scar-related characteristics are reported in Table 1. In general, the descriptive characteristics of both groups were comparable. The mean age of patients in each group differed by 5 years. The mean scar age of both groups was less than three months at baseline.

Table 1.

Patient and scar-related characteristics of patients in the ESWT and placebo groups.

| ESWT | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 20 | 20 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 11 | 11 |

| Women | 9 | 9 |

| Age (years) | 44.4 ± 18.2 | 39.1 ±14.9 |

| Scar age (months) | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.8 |

| Scar type | ||

| Hypertrophy | 16 | 14 |

| Retraction | 1 | 2 |

| Adhesion | 3 | 4 |

| Healing | ||

| Skin grafted | 13 | 11 |

| Spontaneously healed | 7 | 9 |

Values are given as n or mean ± SD.

ESWT, extracorporeal shock wave therapy.

Primary outcome

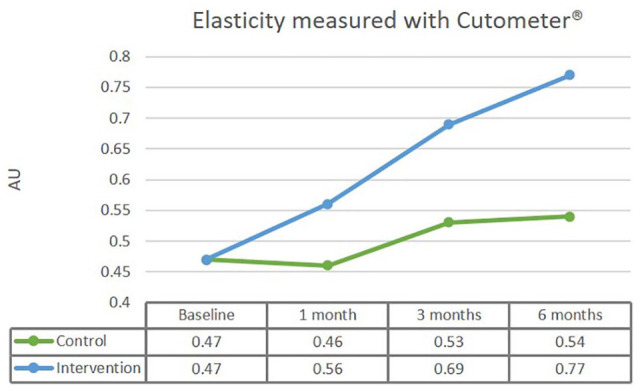

There were two outliers in the data, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot for values > 1.5 box-lengths from the edge of the box. One of the outliers was found in the control group after one month compared to baseline; another outlier was found in the intervention group at baseline. Both outliers were kept, since comparison between the results with or without outliers showed no significant differences. The data were not normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test of normality (P < 0.05). However, the histogram showed normally distributed data. This non-normality did not affect our analysis since comparison of with or without transformed data showed no significant differences. There was a statistically significant interaction between the intervention and time with moderate effect size on elasticity, F(3,114) = 4.562, P = 0.011, partial η2 = 0.107. After adjustment for baseline values, a statistically significant mean difference of 0.23 mm for elasticity between the interventions was found after six months in favour of the intervention group, F(1,37) = 9.288, P = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.201. Please note the large effect size here. The results are set out in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

After adjustment for baseline values, a statistically significant mean difference of 0.232 mm for elasticity between the interventions was found after six months in favour of the intervention group.

Secondary outcomes

There was no statistically significant interaction between intervention and time for the individual items of the POSAS Patient Scale. This indicates that neither group performed better over time. For the overall opinion of the POSAS Patient Scale, a statistically significant difference between the interventions was found after three months (P = 0.045) and after six months (P = 0.013). The results at the different timepoints of all POSAS Patient scores are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

POSAS Patient scores of ESWT versus placebo at baseline (T0), after one month (T1), three months (T2) and six months (T3).

| ESWT |

Placebo |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3* | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3* | |

| Pain | 2.90 (1.88–3.92) | 2.15 (1.44–2.86) | 2.00 (1.21–2.79) | 1.35 (0.88–1.82) 0.56 |

2.65 (1.63–3.67) | 2.20 (1.49–2.91) | 2.35 (1.56–3.14) | 1.55 (1.08–2.02) 0.64 |

| Itch | 3.65 (2.42–4.88) | 3.00 (1.95–4.05) | 2.75 (1.63–3.87) | 1.95 (1.16–2.74) 0.82 |

3.45 (2.22–4.68) | 3.00 (1.95–4.05) | 3.30 (2.18–4.42) | 2.65 (1.86–3.44) 0.34 |

| Colour | 6.65 (5.70–7.60) | 5.95 (4.74–7.16) | 4.65 (3.67–5.63) | 4.05 (3.09–5.01) 1.67 |

7.40 (6.45–8.35) | 6.20 (4.99–7.41) | 5.55 (4.57–6.53) | 4.80 (3.84–5.76) 1.06 |

| Stiffness | 6.35 (5.27–7.43) | 4.80 (3.79–5.81) | 4.30 (3.21–5.39) | 3.55 (2.59–4.51) 1.27 |

6.70 (5.62–7.78) | 5.20 (4.19–6.21) | 4.80 (3.71–5.89) | 4.20 (3.24–5.16) 1.14 |

| Thickness | 4.10 (2.92–5.28) | 3.80 (2.82–4.78) | 2.95 (1.92–3.98) | 2.80 (1.91–3.69) 0.65 |

4.40 (3.22–5.58) | 4.05 (3.07–5.03) | 4.05 (3.02–5.08) | 3.45 (2.56–4.34) 0.38 |

| Irregularity | 4.20 (3.12–5.28) | 4.15 (3.04–5.26) | 3.70 (2.57–4.83) | 3.45 (2.37–4.53) 0.39 |

5.15 (4.07–6.23) | 4.60 (3.49–5.71) | 4.75 (3.62–5.88) | 3.75 (2.67–4.83) 0.53 |

| Overall opinion | 5.80 (4.55–7.05) | 5.05 (4.02–6.08) | 4.10 (3.08–5.12) | 2.95 (2.17–3.73) 1.34 |

5.80 (4.55–7.05) | 5.20 (4.17–6.23) | 5.40 (4.38–6.42) | 4.20 (3.42–4.98) 0.68 |

Values are given as mean (95% CI). Values in italics are Cohen’s d.

Estimates of effect size based on differences between means after 6 months compared to baseline.

CI, confidence interval; ESWT, extracorporeal shock wave therapy; POSAS, Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale.

There was no statistically significant interaction between intervention and time for the individual items of the POSAS Observer Scale. This indicates that neither group performed better over time. For the pliability score (P = 0.015) and the overall opinion (P = 0.027) of the POSAS Observer Scale, a statistically significant difference between the interventions was found at six months in favour of the ESWT group. The results at the different timepoints of all POSAS Observer scores are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

POSAS scores of ESWT versus placebo at baseline (T0), after 1 month (T1), 3 months (T2) and 6 months (T3).

| ESWT |

Placebo |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3* | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3* | |

| Vascularity | 4.95 (4.27–5.64) | 4.35 (3.71–4.99) | 3.90 (3.27–4.53) | 3.00 (2.53–3.47) 1.58 |

5.00 (4.32–5.69) | 3.90 (3.26–4.54) | 3.80 (3.17–4.43) | 3.20 (2.73–3.67) 1.38 |

| Pigmentation | 2.75 (1.91–3.59) | 2.70 (2.03–3.37) | 2.65 (1.97–3.33) | 2.25 (1.74–2.76) 0.37 |

3.25 (2.41–4.09) | 3.05 (2.38–3.72) | 3.00 (2.32–3.68) | 3.00 (2.49–3.51) 0.15 |

| Thickness | 3.10 (2.48–3.72) | 2.85 (2.24–3.46) | 2.60 (1.98–3.22) | 2.35 (1.86–2.84) 0.61 |

3.05 (2.43–3.67) | 2.60 (1.99–3.21) | 2.55 (1.93–3.17) | 2.65 (2.16–3.14) 0.34 |

| Relief | 3.45 (2.92–3.98) | 3.10 (2.63–3.57) | 3.00 (2.47–3.53) | 2.50 (2.03–2.97) 1.34 |

3.10 (2.57–3.63) | 2.85 (2.38–3.32) | 3.00 (2.47–3.53) | 2.75 (2.28–3.22) 0.30 |

| Pliability | 5.50 (4.78–6.22) | 4.05 (3.37–4.74) | 3.40 (2.83–3.97) | 2.45 (2.03–2.87) 2.58 |

5.30 (4.58–6.02) | 4.25 (3.57–4.93) | 3.70 (3.13–4.27) | 3.10 (2.68–3.52) 1.64 |

| Surface area | 5.00 (4.87–5.13) | 4.70 (4.37–5.03) | 4.35 (4.00–4.70) | 4.30 (3.87–4.73) 1.54 |

5.00 (4.91–5.09) | 4.75 (4.45–5.05) | 4.65 (4.20–5.10) | 4.15 (3.49–4.81) 1.52 |

| Overall opinion | 5.05 (4.64–5.46) | 4.20 (3.75–4.66) | 3.55 (3.12–3.98) | 3.00 (2.66–3.34) 2.48 |

4.90 (4.49–5.30) | 4.20 (3.75–4.66) | 3.80 (3.37–4.23) | 3.55 (3.21–3.89) 1.72 |

Values are given as mean (95% CI). Values in italics are Cohen’s d.

Estimates of effect size based on differences between means after 6 months compared to baseline.

CI, confidence interval; ESWT, extracorporeal shock wave therapy; POSAS, Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale.

There were no statistically significant differences between the interventions for the brightness and the redness parameter of colorimetry and for TEWL. The results at the different timepoints of objective assessment results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Objective assessment results of ESWT versus placebo at baseline (T0), after one month (T1), three months (T2) and six months (T3).

| ESWT | Placebo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3* | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3* | |

| Brightness | 51.02 (48.7–53.4) | 52.74 (50.3–55.2) | 54.42 (52.1–56.8) | 57.91 (55.2–60.6) 1.29 |

50.93 (48.6–53.3) |

51.19 (48.7–53.7) | 52.53 (50.2–54.9) | 54.45 (51.8–57.1) 0.86 |

| Redness | 17.14 (15.7–18.6) | 15.33 (14.1–16.6) |

14.46 (13.3–15.6) | 13.4 (11.8–14.5) 1.30 |

16.37 (14.9–17.8) |

15.25 (14.0–16.5) | 14.80 (13.7–15.9) | 13.21 (11.9–14.5) 1.01 |

| TEWL | 17.12 (13.4–20.8) | 13.87 (10.5–17.3) | 11.59 (8.3–14.9) | 10.55 (6.8–14.3) 0.89 |

17.57 (13.9–21.3) |

15.00 (11.6–18.4) | 13.32 (10.0–16.6) | 13.99 (10.3–17.7) 0.40 |

| Elasticity | 0.46 (0.34–0.58) | 0.56 (0.43–0.68) | 0.68 (0.55–0.81) | 0.77 (0.65–0.89) 1.10 |

0.48 (0.36-0,59) |

0.47 (0,34-0,60) |

0.53 (0.40–0.66) | 0.54 (0.42–0.66) 0.27 |

Values are given as mean (95% CI). Values in italics are Cohen’s d.

Estimates of effect size based on differences between means after 6 months compared to baseline.

CI, confidence interval; ESWT, extracorporeal shock wave therapy; TEWL, trans-epidermal water loss.

Discussion

The present study is the first randomised controlled study on humans to investigate the effects of ESWT on the elasticity of burn scars with an objective assessment device. This study’s results pointed out that the ESWT group performed statistically significantly better than a placebo group to improve vertical elasticity of burn scars.

The results of this study were somewhat contradictory. The POSAS Patient and Observer scores did not reveal any statistically significant time versus intervention interactions between the two groups, while the objective measurement of elasticity with Cutometer® showed a statistically significant difference between the groups over time in favour of the ESWT group. This means that the subjective results did not back up the objective outcomes. This could be explained by the different assessment methods. The three assessment methods assess different mechanical properties.23 For the POSAS Patient Scale, the patient is asked whether the stiffness of the scar is different from normal skin; in the POSAS Observer Scale, the observer is asked to assess suppleness by wrinkling the scar between thumb and index finger; and with the Cutometer® the skin is lifted vertically by suction. On consideration of these definitions, it may seem difficult to compare stiffness, pliability and extensibility.

The question remains on how the beneficial effects of ESWT on fibrosis can be explained.

On a histopathological level, the effects of ESWT on fibrosis are plural. A downregulation of alpha-SMA expression, myofibroblast phenotype, TGF-β1 expression, fibronectin and collagen type I are measured.15,24,25 Inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad signalling pathway and decreased fibroblast density are also observed.26,27 A significant increase in dermal fibroblast like phenotype with low contractility and high migratory ability, small vessel density and precursors of extracellular matrix components, probably leads to new and thinner collagen fascicles and parallel orientation to the dermo-epidermal junction.24,25 All these findings are closely related to a mechanotransduction effect induced by ESWT, where these biomechanical forces are converted in biochemical responses, thus influencing some fundamental cell functions as migration, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis.28 The formation of fibrous tissue can be prevented by ESWT (at the origin) during wound healing processes, but it can also be remodelled in a second phase of scar formation. Primary data shows that height, pliability, vascularity and pigmentation, all relevant scar parameters, were improved after the application of ESWT.13,15 The changes in these physical and physiological parameters will probably lead to amelioration in function,15 which was confirmed by our results with improved elasticity as the primary outcome.

For a full treatment protocol outline, the energy flux density (EFD), the number of pulses, the pulse frequency, and the number and interval of treatments are the most relevant parameters.29 Differences in the device settings can lead to varying outcomes, emphasising the dose dependency of these mechanotransduction events.30 High-energy ESWT can suppress cell growth, while lower-energy shock waves might enhance cell proliferation.31 Since ESWT settings of 0.22 mJ/mm2 and 1000 pulses seem to be ideal for fibroblast viability and growth,32 and an EFD of 0.32 mJ/mm2 reduces the expression of type-I collagen,24 we opted for an EFD of 0.25 mJ/mm2 and 30–50 shocks per cm2. This was also comparable with the previous studies performed on scars.13–15

Two studies reported a significant decrease of burn-associated pruritus.16,33 This finding is consistent with the results from this study of which the POSAS Patient Scale revealed a significant reduction for the itch parameter only for the ESWT group. However, this result did not lead to a statistically significant difference between both treatment arms, which can be explained by the application of a ‘standard of care’ including hydration and silicone for both groups. In the studies by Joo et al.16 and Samhan et al.,33 75% of the patients were grafted, compared with only 60% of the patients in this study. Joo et al. made no mention of the mean scar age, which was less than three months in this study. A mean baseline POSAS score of 3.65 could also suggest that in this study pruritus was not a relevant parameter.

The aim of our study was to investigate the beneficial effects of ESWT on burn scars in the first three months after wound closure. In these first three months, the number of applicable treatments is limited due to the fragility of the skin and the danger of inflicting new friction wounds. As a non-contact intervention, ESWT could solve this problem. With a mean scar age of 2.7 and 2.4 months, this study showed that ESWT presented better results than placebo treatment to improve elasticity of young burn scars.

Limitations of this study include assessments only up to six months and the heterogeneity of healing types. Comparing ESWT and placebo as an addition to a ‘standard of care’, which includes two evidence-based treatments (pressure therapy and silicone therapy) makes it more difficult to find statistically significant differences between the interventions. These findings do not guarantee the same effects if pressure therapy or silicone therapy would be left out and can certainly not lead to the conclusion that shock wave therapy can replace either of these two evidence-based treatments. On the other hand, ESWT does seem to give added value to the ‘standard of care’ to improve the elasticity of burn scars.

Conclusion

ESWT can give added value to the non-invasive treatment of hypertrophic burn scars, more specifically to improve elasticity already in the first three months after wound closure.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Peter Moortgat  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6840-762X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6840-762X

Bibliography

- 1. Esselman PC. Burn rehabilitation: an overview. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88 (12 SUPPL. 2): S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ault P, Plaza A, Paratz J. Scar massage for hypertrophic burns scarring—A systematic review. Burns 2018; 44: 24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van den Kerckhove E, Stappaerts K, Fieuws S, et al. The assessment of erythema and thickness on burn related scars during pressure garment therapy as a preventive measure for hypertrophic scarring. Burns 2005; 31(6): 696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anthonissen M, Daly D, Janssens T, et al. The effects of conservative treatments on burn scars: A systematic review. Burns 2016; 42: 508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nedelec B, Couture MA, Calva V, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the immediate and long-term effect of massage on adult postburn scar. Burns 2019. February 1;45(1):128–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cho YS, Jeon JH, Hong A, et al. The effect of burn rehabilitation massage therapy on hypertrophic scar after burn: a randomized controlled trial. Burns 2014; 40(8): 1513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jang KU, Choi JS, Mun JH, et al. Multi-axis shoulder abduction splint in acute burn rehabilitation: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Rehabil 2015; 29(5): 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schouten HJ, Nieuwenhuis MK, van Zuijlen PPM. A review on static splinting therapy to prevent burn scar contracture: Do clinical and experimental data warrant its clinical application? Burns 2012; 38: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kolmus AM, Holland AE, Byrne MJ, et al. The effects of splinting on shoulder function in adult burns. Burns 2012; 38(5): 638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knobloch K, Joest B, Krämer R, et al. Cellulite and focused extracorporeal shockwave therapy for non-invasive body contouring: a randomized trial. Dermatol Ther 2013; 3(2): 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kruglikov I. The Pathophysiology of Cellulite: Can the Puzzle Eventually Be Solved? Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications 2012; 02(01) :1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moortgat P, Anthonissen M, Meirte J, et al. The physical and physiological effects of vacuum massage on the different skin layers: a current status of the literature. Burns Trauma 2016; 4(1): 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fioramonti P, Cigna E, Onesti MG, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the management of burn scars. Dermatol Surg 2012; 38(5): 778–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cho YS, Joo SY, Cui H, et al. Effect of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on scar pain in burn patients: A prospective, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study. Medicine 2016; 95(32): e4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saggini R, Saggini A, Spagnoli AM, et al. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy: An Emerging Treatment Modality for Retracting Scars of the Hands. Ultrasound Med Biol 2016; 42: 185–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joo SY, Cho YS, Seo CH. The clinical utility of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for burn pruritus: A prospective, randomized, single-blind study. Burns 2018; 44(3): 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. STORZ AG. Duolith SD-I Manual. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FRH, Botman YAM, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004; 113(7): 1960–5; discussion 1966-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van den Kerckhove E, Staes F, Flour M, et al. Reproducibility of repeated measurements on healthy skin with Minolta Chromameter CR-300. Skin Res Technol 2001; 7(1): 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anthonissen M, Daly D, Fieuws S, et al. Measurement of elasticity and transepidermal water loss rate of burn scars with the Dermalab(®). Burns 2013; 39(3): 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Draaijers LJ, Botman YAM, Tempelman FRH, et al. Skin elasticity meter or subjective evaluation in scars: a reliability assessment. Burns 2004; 30(2): 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gardien KLM, Baas DC, de Vet HCW, et al. Transepidermal water loss measured with the Tewameter TM300 in burn scars. Burns 2016; 42(7): 1455–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clark JA, Cheng JC, Leung KS. Mechanical properties of normal skin and hypertrophic scars. Burns 1996; 22(6): 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rinella L, Marano F, Berta L, et al. Extracorporeal shock waves modulate myofibroblast differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells. Wound Repair Regen 2016; 24(2): 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cui HS, Hong AR, Kim J-B, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy alters the expression of fibrosis-related molecules in fibroblast derived from human hypertrophic scar. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19(1): 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao J-C, Zhang B-R, Shi K, et al. Lower energy radial shock wave therapy improves characteristics of hypertrophic scar in a rabbit ear model. Exp Ther Med 2018; 15(1) :933–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhao J-C, Zhang B-R, Hong L, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy with low-energy flux density inhibits hypertrophic scar formation in an animal model. Int J Mol Med 2018; 41(4): 1931–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ingber DE. Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J 2006; 20: 811–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mittermayr R, Antonic V, Hartinger J, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) for wound healing: technology, mechanisms, and clinical efficacy. Wound Repair Regen 2012; 20(4): 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. d’Agostino MC, Craig K, Tibalt E, et al. Shock wave as biological therapeutic tool: From mechanical stimulation to recovery and healing, through mechanotransduction. Int J Surg 2015; 24: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cai Z, Falkensammer F, Andrukhov O, et al. Effects of Shock Waves on Expression of IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and TNF-α Expression by Human Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts: An In Vitro Study. Med Sci Monit 2016; 22: 914–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berta L, Fazzari A, Ficco AM, et al. Extracorporeal shock waves enhance normal fibroblast proliferation in vitro and activate mRNA expression for TGF-β1 and for collagen types I and III. Acta Orthop 2009; 80: 612–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Samhan AF, Abdelhalim NM. Impacts of low-energy extracorporeal shockwave therapy on pain, pruritus, and health-related quality of life in patients with burn: A randomized placebo-controlled study. Burns 2019; 45(5): 1094–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How to cite this article

- Moortgat P, Anthonissen M, Van Daele U, Vanhullebusch T, Maertens K, De Cuyper L, Lafaire C, Meirte J. The effects of shock wave therapy applied on hypertrophic burn scars: a randomised controlled trial. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 6, 2020. DOI: 10.1177/2059513118975624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]