Abstract

BACKGROUND

Here we present a rare case of localized amyloidosis involving the nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac which was managed by endoscopic surgery.

CASE SUMMARY

A 50-year-old man whose medical history included bilateral ventricular fold and vocal cord amyloidosis complained of bilateral epiphora. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a neoplasm within the nasolacrimal sac. Characteristic positivity for Congo red staining and birefringence under a polarized microscope proved the diagnosis of amyloidosis. Dacryocystorhinostomy via an endoscope obtained a favorable result. A one-year follow-up found no recurrence.

CONCLUSION

There are few reports on amyloidosis involving the lacrimal outflow system, and management and outcome are not clear. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy can be a choice to relieve symptoms. Regular follow-up and monitoring of systemic diseases are highly recommended.

Keywords: Amyloidosis, Nasolacrimal duct, Nasolacrimal sac, Endoscopy, Dacryocystorhinostomy, Case report

Core Tip: A 50-year-old man was admitted with bilateral epiphora for 2 years and an enlargement of the lacrimal sac in his left eye for 3 mo. His medical history included bilateral ventricular fold and vocal cord amyloidosis followed by a neoplasm of the tongue base. Pathological examinations showed positive congo red staining with apple-green birefringence under polarized light. Endoscopic left dacryocystorhinostomy was performed to remove the mass in the nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac and achieved no recurrence during 1-year follow-up. Regular follow-up and monitoring of systemic diseases are highly recommended.

INTRODUCTION

Amyloidosis is an idiopathic group of diseases presenting with extracellular deposition of misfolded proteins, forming proteinaceous, amorphous material within connective tissues. Amyloidosis occurs in systemic or localized forms[1]. Localized amyloid, which is rare, most commonly deposits in the head and neck region, and is characterized by an excellent prognosis. The most commonly reported head and neck amyloidosis is localized in the larynx. Orbital involvement cases are not extremely rare except those affecting the lacrimal sac.

This report presents a rare case of amyloidosis localized to multiple head and neck locations (the larynx, tongue, trachea, nasopharynx, oropharynx, uvula, and eventually bilateral nasolacrimal duct) without evidence of familial heredity or systemic disease. To our knowledge, nasolacrimal duct involvement by amyloidosis has been previously reported in only three articles[2-4], and this is the first case to make exploration via endoscopic approach.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Bilateral epiphora for 2 years.

History of present illness

A 50-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of bilateral epiphora, deteriorating in recent 3 mo, with an enlargement in the area overlying the lacrimal sac in his left eye. No eye pain, erythema, impaired vision, or purulent discharge from the puncta was presented. Previous irrigation of the lacrimal systems and eyedrop treatment made no improvement.

History of past illness

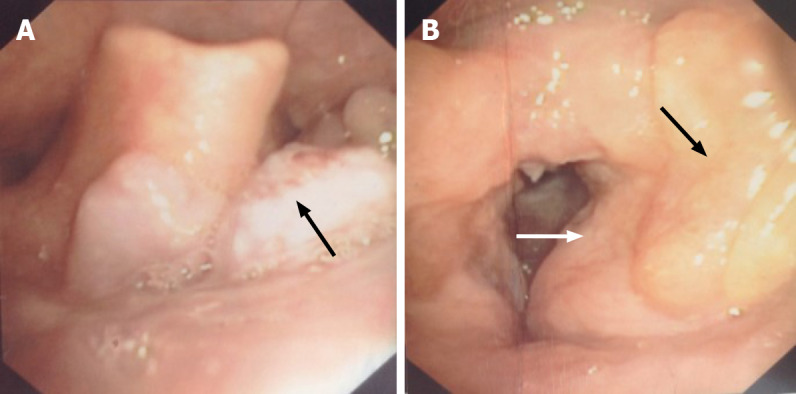

His medical history included bilateral ventricular fold and vocal cord amyloidosis treated by a microlaryngoscopic surgery 2 years ago, followed by a neoplasm of the tongue base 9 mo later (Figure 1). He had undergone another microlaryngoscopic surgery to clear amyloid deposits under the mucosa of the tongue.

Figure 1.

Fiber laryngoscopy findings before surgery. A: Fiber laryngoscopy showed a neoplasm with a coarse surface (black arrow) near the tongue base; B: Left vocal cord was covered by swelling and thickening ventricular fold (white arrow), and yellow sediment was observed near the left ventricular fold (black arrow). No lesion was found on the right vocal cord.

Physical examination

On examination, there was a firm mass on palpation in the area of the left lacrimal sac externally. The visual acuity was 1.2/OU. Intraocular pressures, motility, pupils, and other ophthalmologic examinations were normal except an elevated tear meniscus in bilateral eyes (especially the left eye) and irrigation of the lacrimal duct showed complete left nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO).

Laboratory examinations

The patient was referred to a hematologist after the final surgery to undertake extensive hematologic and systematic studies. No monoclonal protein expression was found in immunofixation electrophoresis of urine and serum, and the sensitive quantitative serum free light chain assay showed normal results. An abdominal fat pad aspirate found no amyloid deposits. The patient’s echocardiogram and chest X-ray showed no evidence of parenchymal or cardiac disease.

Imaging examinations

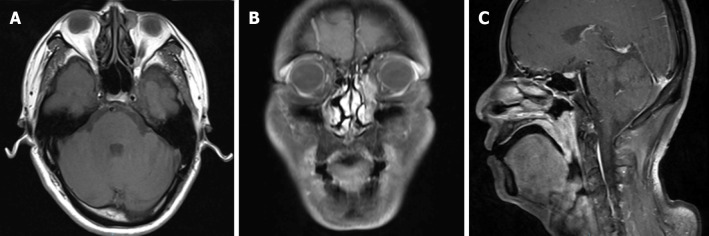

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed extensive soft tissue thickening in the posterior and lateral wall of the nasopharynx, and the lateral wall of the oropharynx and uvula. A soft tissue intensity mass was observed within the left nasolacrimal sac (Figure 2). There was no sign of previous lacrimal system injury from last two surgeries.

Figure 2.

Pre-operative head and neck magnetic resonance imaging. A: T1 weighted imaging (T1WI) showed a round soft tissue intensity mass within the left lacrimal sac, presenting equal signal in T1WI, and heterogeneous high signal in T2WI, without obvious enhancement when contrasted; B: T1WI with contrast showed an abnormal high signal mass along the left nasolacrimal duct, from the lacrimal sac to the level of inferior turbinate; C: Sagittal T1WI demonstrated extensive soft tissue thickening of the posterior wall of the nasopharynx and the lateral wall of the oropharynx and uvula, with isointensity on T1WI and slightly high signal on T2WI, apparently enhanced when contrasted.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

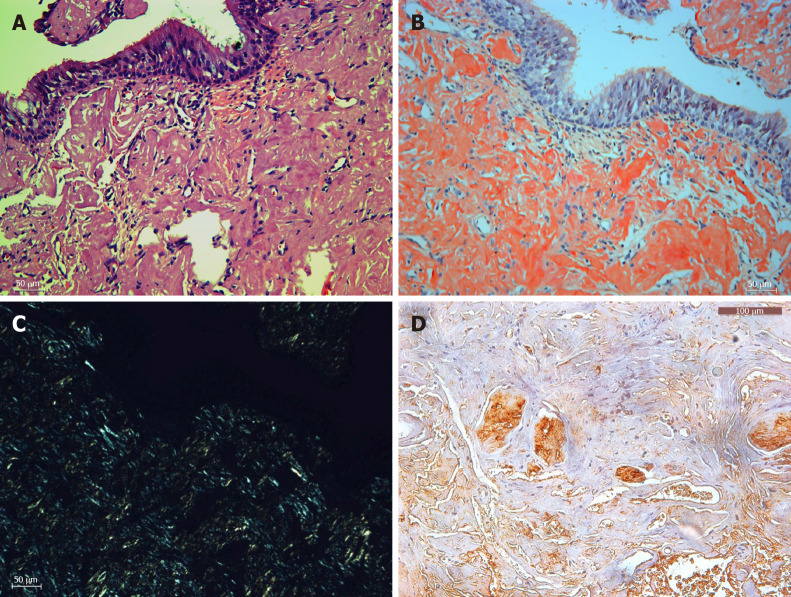

The diagnosis of amyloidosis was proved by pathological examination. Specimens of these friable tissues were submitted for histopathologic examination, which showed the masses to be fibrous tissue with dense amyloid deposition. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, pink amorphous deposits were noted in the submucosa under the pseudostratified nonkeratinized epithelial mucosa (Figure 3A). Under polarized light, amyloid staining showed typical positive Congo Red staining with apple-green birefringence (Figure 3B and C). Immunohistochemistry study was performed to investigate the composition of the amyloid material (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Histopathology (× 200). A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of amyloid tissues; B: Congo staining of the same area of amyloid tissues; C: Corresponding area under a polarization microscope; D: Immunohistochemistry showed positive lambda light chain staining. Bar: 100 μm.

TREATMENT

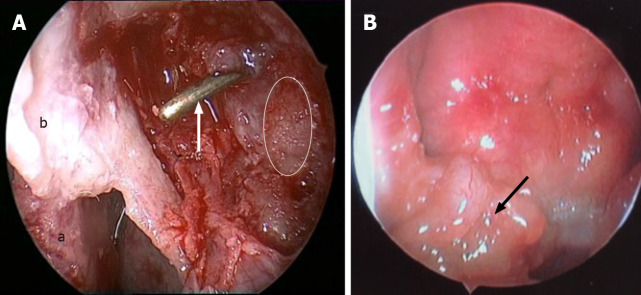

Subsequently, the patient underwent endoscopic left dacryocystorhinostomy and resection of multiple masses.

Intraoperatively, we found friable yellowish masses in the basis nasi and bilateral posterior naris, with involvement of the right torus, nasopharynx, uvula, and oropharynx. The nasolacrimal duct was filled with similar yellowish sediment, as well as lacrimal sac (Figure 4). After the endoscopic surgery, no macroscopic residual lesions remained.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic images in surgery. A: The left lacrimal sac was filled with friable, grey to yellow, glistening, and waxy sediment (white line area), dacryocystorhinostomy was done, and the probe (white arrow) showed opening of the lacrimal sac into the nasal cavity (a: Middle turbinate; b: Nasal mucosa flap); B: An irregular-surfaced mass was noted in the right nasopharynx.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

One week after operation, the patient’s left eye was freely irrigated in the examination of the inferior punctum by syringing, however, the right eye presented mucous reflux on irrigation and was partially obstructed. Endoscopic follow-up at 1 year after surgery showed well healing of the wounds, without adhesion or sign of recurrence or obstruction of the lacrimal sac. No sign of mass obstructing the nasolacrimal duct or other lesions was noted on computed tomography (CT) 1 year later.

DISCUSSION

Amyloidosis refers to the idiopathic, extracellular deposition of fibrillar proteins in tissues, sharing a common feature: Misfolded proteins with a beta-pleated-sheet structure. According to modern classification of amyloidosis based on the nature of the precursor plasma proteins, there are three most common forms of amyloidosis, namely, AL (immunoglobulin light chain as precursor), AA (serum amyloid A), and ATTR (transthyretin)[1]. In this case, the immunohistochemistry showed the precursor to be lambda light chain.

Localized amyloidosis is relatively rare. The plasma cells producing abnormal proteins are limited to the tissues rather than in the bone marrow. The larynx (60%) is the most common site of amyloid deposition in the head and neck, followed by the trachea (9%), orbit (4%), and nasopharynx (3%)[5]; however, larynx deposition is rarely a component of systemic amyloidosis[6-8]. Only 4% of cases of focal amyloidosis involving the head and neck region occur in the orbit[9], which often include amyloid infiltration of the lacrimal gland, extraocular muscle, orbital fat, and even optic nerve[10-15]. However, nasolacrimal duct or lacrimal sac involvement is hardly reported. The first literature regarding the lacrimal outflow system was reported by Marcet et al[3], describing a patient with amyloidosis limited to the lacrimal duct and lacrimal sac, and an external dacryocystorhinostomy did not relieve lacrimal system obstruction. Geller et al[2] described a patient with complete NLDO secondary to localized amyloidosis of the nasopharyngeal region, and without surgical intervention on the lacrimal outflow system[2]. A third case of nasolacrimal sac amyloidosis was reported to mimic both neoplasm and dacryolith managed by external dacryocystorhinostomy[4]. In our study, NLDO was reported following endoscopic surgery first employed, and a one-year follow-up found no recurrence.

Not all head and neck amyloidosis cases are related to a systemic disorder, but 90% of patients with systemic amyloid will develop amyloid deposits in the upper aerodigestive tract[6]. So it is more than necessary to evaluate for systemic condition, which may exclude malignancy.

Diagnosis of amyloidosis depends on biopsies of specific organs or tissues, because imaging findings of amyloidosis are various and nonspecific[3,16,17]. Occasionally, it mimics localized or widespread carcinoma with lymph node metastasis when a neck mass is present[17]. CT and MRI are both used to evaluate the extent of amyloid, but some demonstrated that CT imaging shows calcifications better and can be more useful than MRI[9,10,12,14]. We used MRI to determine the extent of amyloid because of the previous surgery and complicated history of this patient. Diagnosis is made histochemically with characteristic positivity for Congo red staining and birefringence under a polarized microscope once systemic amyloidosis is ruled out. Treatment options including corticosteroids, radiotherapy, and agents like melphalan result in variable outcomes, but most authors believe that for localized amyloidosis, surgery for symptomatic relief is a favorable choice[18-20].

Although bilateral eyes both presented with epiphora in this patient, we find no significant lesion on the right eye in both endoscopic examination and MRI. Surgery was carried out only on the left eye, which had more severe symptoms. Surgery turned out to be effective, and the right eye had not been deteriorated so far.

Different recurrent rates for local head and neck amyloidosis were reported. Heinritz et al[21] reported complete excision without recurrence during a period of 10 years in 12 cases. Feng et al[22] reported a 20% recurrence rate 6 mo after the first surgery[22]. There is no evidence of localized amyloid progressing to develop systemic malignancy, but an underlying malignancy should call concern in the case of amyloidosis of head and neck mucosal sites excluding the larynx[6,7,23,24]. The prognosis is uncertain owing to the rarity of the condition, and we cautiously recommend regular follow-up and monitoring.

CONCLUSION

We have reported a patient with bilateral NLDO whose amyloidosis initiated from larynx, extended to the tongue, trachea, and nasopharynx, and finally involved the lacrimal outflow system without systemic conditions. It is the first case to try endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy in treating NLDO caused by localized amyloidosis, and the outcome proved to be satisfactory in a one-year follow-up. Regular follow-up and monitoring of systemic diseases are highly recommended.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Medical Association.

Peer-review started: June 18, 2020

First decision: September 23, 2020

Article in press: October 20, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tantau AI S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Xiao-Le Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China.

Jing-Yi Yang, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China.

Yu-Ting Lai, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China.

Jia-Ying Zhou, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China.

Jing-Jing Wang, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China.

Xi-Cai Sun, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China.

De-Hui Wang, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200031, China. wangdehuient@sina.com.

References

- 1.Khan MF, Falk RH. Amyloidosis. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:686–693. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.913.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geller E, Freitag SK, Laver NV. Localized nasopharyngeal amyloidosis causing bilateral nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:e64–e67. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181e99e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcet MM, Roh JH, Mandeville JT, Woog JJ. Localized orbital amyloidosis involving the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine MR, Seipel SB, Plesec TP, Costin BR. Amyloid Pseudo-Dacryolith and Nasolacrimal Obstruction in a 67-Year-Old Male. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:e86–e88. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karimi K, Chheda NN. Nasopharyngeal amyloidosis: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2010;120 Suppl 4:S197. doi: 10.1002/lary.21664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebowitz RA, Morris L. Plasma cell dyscrasias and amyloidosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:747–764. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(03)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson LD, Derringer GA, Wenig BM. Amyloidosis of the larynx: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:528–535. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pribitkin E, Friedman O, O'Hara B, Cunnane MF, Levi D, Rosen M, Keane WM, Sataloff RT. Amyloidosis of the upper aerodigestive tract. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:2095–2101. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200312000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gean-Marton AD, Kirsch CF, Vezina LG, Weber AL. Focal amyloidosis of the head and neck: evaluation with CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;181:521–525. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.2.1924798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibovitch I, Selva D, Goldberg RA, Sullivan TJ, Saeed P, Davis G, McCann JD, McNab A, Rootman J. Periocular and orbital amyloidosis: clinical characteristics, management, and outcome. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1657–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savino PJ, Schatz NJ, Rodrigues MM. Orbital amyloidosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1976;11:252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murdoch IE, Sullivan TJ, Moseley I, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB, Tan SY, Garner A, Wright JE. Primary localised amyloidosis of the orbit. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:1083–1086. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.12.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng JY, Fong KS, Cheah ES, Choo CT. Lacrimal gland amyloidosis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:306–308. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000222354.44000.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto K, Ito J, Emura I, Kawasaki T, Furusawa T, Sakai K, Tokiguchi S. Focal orbital amyloidosis presenting as rectus muscle enlargement: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1799–1801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton AW, Leone CR Jr, Hunter DM. Optic nerve pseudomeningioma secondary to localized amyloidosis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;5:52–55. doi: 10.1097/00002341-198903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin SC, Fatterpeckar G, Kao CH, Chen CY, Som PM. Amyloidosis concurrently involving the sinonasal cavities and larynx. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:636–638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhuang YL, Tsai TL, Lin CZ. Localized amyloid deposition in the nasopharynx and neck, mimicking nasopharyngeal carcinoma with neck metastasis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68:142–145. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naidoo YS, Gupta R, Sacks R. A retrospective case review of isolated sinonasal amyloidosis. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:633–637. doi: 10.1017/S0022215112000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avitia S, Hamilton JS, Osborne RF. Surgical rehabilitation for primary laryngeal amyloidosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86:206, 208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feingold RM. Laryngeal amyloidosis. J Insur Med. 2012;43:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinritz H, Kraus T, Iro H. [Localized amyloidosis in the area of the head-neck. A retrospective study] HNO. 1994;42:744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng Y, Xi L, Yu X, He G. [Analysis of clinical manifestations of rhinal and pharyngeal and laryngeal amyloidosis by 12 cases] Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;25:1115–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrinely JR, Koch DD. Surgical management of advanced ocular adnexal amyloidosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:882–885. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080180154045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penner CR, Muller S. Head and neck amyloidosis: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]