Abstract

BACKGROUND

Esophageal schwannomas are uncommon esophageal submucosal benign tumors and are usually treated with surgery.

CASE SUMMARY

Here, we report three cases of middle/lower thoracic esophageal schwannoma treated successfully with endoscopic resection. These lesions were misdiagnosed as leiomyoma on preoperative imaging. During the endoscopic resection of such tumors, there is a risk of esophageal perforation due to their deep location. If possible, submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection should be used.

CONCLUSION

For larger schwannomas, endoscopy combined with thoracoscopy can be considered for en bloc resection. We performed a mini literature review in order to present the current status of diagnosis and treatment for esophageal schwannoma.

Keywords: Esophageal schwannoma, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Endoscopic submucosal excavation, Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection, Case report

Core Tip: Most esophageal schwannomas are rare submucosal lesions, and malignant esophageal schwannoma has been reported. We summarize three cases of esophageal schwannoma with successful endoscopic resection. They were misdiagnosed as leiomyoma or cystic solid tumors based on endoscopic ultrasound before surgery. Small lesions in a suitable location can be removed endoscopically by experienced endoscopists using endoscopic submucosal excision or submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection. For larger lesions (> 3 cm), especially tumors with cystic degeneration, endoscopic treatment may not be suitable. For such lesions, robot-assisted thoracoscopic excision or endoscopic treatment combined with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery may be a better option.

INTRODUCTION

There are many types of submucosal tumors that can occur in the gastrointestinal tract, the most common being myogenic tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and leiomyoma. Neurogenic tumors (which include esophageal schwannomas) are rare[1]. The majority of esophageal submucosal tumors are leiomyomas[2]. Esophageal schwannoma is difficult to diagnose during preoperative investigations due to its similarity to other intramural submucosal tumors (leiomyomas, GISTs, esophageal cysts)[3]. Most of these tumors are benign. However, malignant esophageal schwannoma has been reported in the literature[4,5]. Esophageal schwannoma frequently occurs in middle-aged women and is often located on the proximal esophagus with sizes ranging from 1 cm to 15 cm[6].

A literature search in the PubMed database found 120 studies published on the topic between 1989 and 2018[7]. In most of these studies, as schwannoma is a type of esophageal submucosal tumor, patients underwent surgical excision depending on the tumor size, location, and morphology[8,9].

There have been some reports of endoscopic resection (two cases in Japan and three cases in other countries), all of which were case reports. In 1987, endoscopic resection of submucosal tumors (including schwannomas) was first reported in Japan[10,11]. In the rest of the world, the first endoscopic resection of an esophageal schwannoma was performed in 2001[12]. In the three reports of endoscopic resection above, all of the lesions were superficial in position and direct endoscopic resection was performed (Table 1)[12-16].

Table 1.

Clinicoradiological characteristics of reported cases of esophageal schwannoma treated using endoscopic techniques

|

Case

|

Ref.

|

Age in yr/sex

|

Presenting symptom

|

Mass location

|

EUS finding

|

Tumor size in mm

|

Treatment

|

Malignant findings

|

| 1 | Koizumi et al[10], Japan | 55/M | None | Ae | Not known | 22 × 15 | Endoscopic resection | - |

| 2 | Konishi et al[11], Japan | 79/M | None | Mt | Not known | < 5 | Endoscopic resection | - |

| 3 | Naus et al[12] | 39/M | Epigastric pain (not felt because of lesion) | Lt | Not performed | 1 × 1 | Endoscopic removal | - |

| 4 | Shimamura et al[15] | 59/M | Intermittent acid reflux symptoms (not felt because of lesion) | Ae | Not performed | 5 × 5 | Endoscopic resection | - |

| 5 | Trindade et al[16] | 54/M | Esophageal reflux disease | Lt | Hypoechoic heterogeneous lesion in the 2nd layer of the gastrointestinal tract | 6 × 6 | Endoscopic mucosal resection | - |

| 6 | Our case 1 | 59/M | Upper abdominal distension and esophageal reflux disease | Lt | Hypoechoic, homogeneous, exogenous pseudopodal echo, originating in the muscular layer, misdiagnosed as leiomyoma | 14 × 5 | ESE | - |

| 7 | Our case 2 | 51/F | Discontinuous upper abdominal discomfort | Mt | Hypoechoic, homogeneous and well-defined. Originating in the muscular layer. The blood flow was not obvious and the lesion was near the aorta. Misdiagnosed as leiomyoma | 18 × 20 | STER | - |

| 8 | Our case 3 | 50/M | Dysphagia | Lt | Originating in the muscular layer, misdiagnosed as cystic solid tumor. Diagnosed with CT as neurogenic tumor or gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 28 × 22 | STERThe lesion was resected in a piecemeal fashion. | - |

Ae: Abdominal esophagus; Ce: Cervical esophagus; CT: Computed tomography; ESE: Endoscopic submucosal excision; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; Lt: Lower thoracic esophagus; Mt: Middle thoracic esophagus; STER: Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection; Ut: Upper thoracic esophagus.

With the development of endoscopic instruments and minimally invasive endoscopic techniques, endoscopic submucosal excision (ESE) and submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER), which are based on endoscopic submucosal dissection, are widely used in clinical practice.

Compared with open and laparoscopic surgery, endoscopic resection causes little trauma and fewer complications, leading to faster recovery and shorter hospitalization. Although it has been reported that endoscopy can remove submucosal tumors including schwannomas, the characteristics and differences between schwannomas and other submucosal tumors have not been described in detail[17]. In this study, we summarize the data for three patients with esophageal schwannoma in a deep location, misdiagnosed as leiomyoma or cystic solid tumor by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) before surgery, with successful endoscopic resection. All three cases were treated with endoscopic resection by an experienced endoscopist who had performed more than 300 endoscopic submucosal dissection-related procedures.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Case 1: A 59-year-old man presented with upper abdominal distension lasting for 15 d.

Case 2: A 51-year-old woman presented with upper abdominal discomfort with heartburn lasting for 1 yr.

Case 3: A 49-year-old man presented with dysphagia lasting for 1 yr.

History of present illness

Case 1: The patient was apparently well 15 d earlier when he first noticed the upper abdominal distension. There was no history of nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, or abdominal pain.

Case 2: She was apparently well 1 yr earlier when she started developing intermittent upper abdominal discomfort and heartburn. There were no aggravating or relieving factors. There was no associated dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, or fever.

Case 3: He suffered from nonprogressive dysphagia for 1 yr and had difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids. There were no associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, chest pain, heartburn, or abdominal pain.

History of past illness

Case 1: The patient denied having any chronic medical or surgical illnesses in the past.

Case 2: She had undergone myomectomy 2 years earlier.

Case 3: He had a history of appendectomy 30 years earlier.

Physical examination

Case 1: His general condition and vital signs were normal. On physical examination, there were no obvious positive findings.

Case 2: There was a 7 cm healed scar from a previous surgery in the lower abdomen. There were no other obvious positive findings.

Case 3: His vital signs were stable. The general and abdominal examinations revealed no obvious positive findings.

Laboratory examinations

Case 1: Routine blood investigations such as the complete blood count and liver and kidney function tests were within normal limits.

Case 2: The levels of anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody and thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody were elevated. However, the levels of free triiodothyronine and free thyroxine with thyroid-stimulating hormone were normal. The rest of the laboratory tests were within normal limits.

Case 3: Blood investigations including the complete blood count and liver and renal function tests were in the normal range.

Imaging examinations

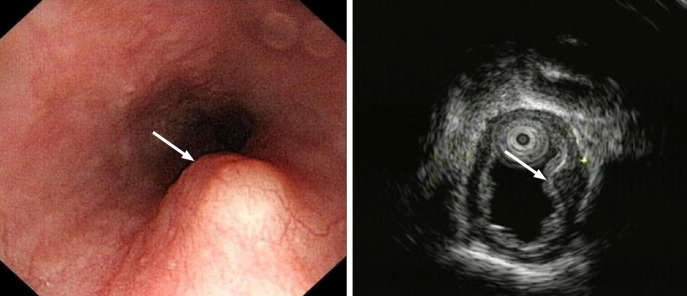

Case 1: On upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, a 14 mm × 5 mm submucosal tumor was found 35 cm from the incisor teeth on the posterior wall of the esophagus. EUS revealed a hypoechoic, homogeneous lesion originating in the muscular layer with features suggestive of leiomyoma (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case 1 Endoscopic view of the submucosal tumor located in the lower thoracic esophagus. Endoscopic ultrasound revealed a lesion arising from the muscular layer, misdiagnosed as leiomyoma (white arrow).

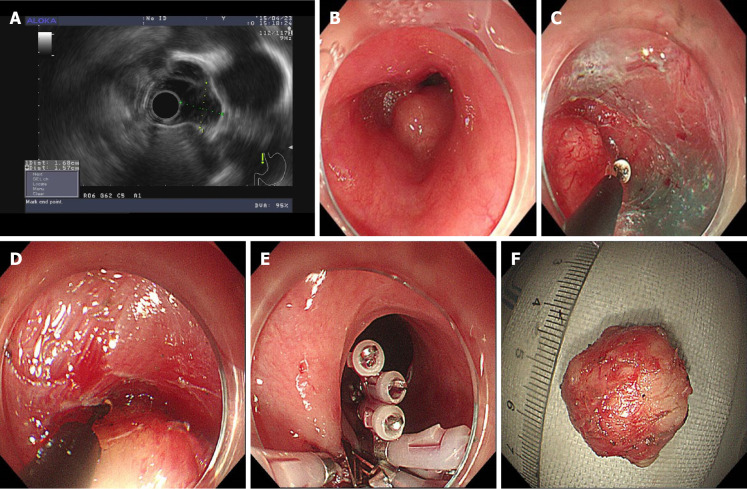

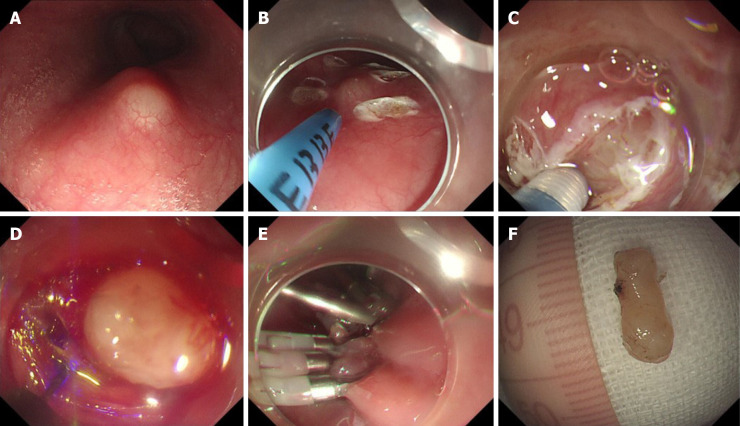

Case 2: An upper gastrointestinal barium swallow test showed a filling defect of 2 cm on the posterior wall of the esophagus. Endoscopy revealed an 18 mm × 20 mm submucosal lesion 26 cm from the incisor teeth on the right posterior wall of the esophagus. On EUS, there was a hypoechoic, homogeneous, and well-defined lesion originating from the muscular layer of the esophagus. The blood supply of the lesion was not obvious, but it was located near the aorta. It was provisionally diagnosed as leiomyoma (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Case 2 Steps of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection. A: Endoscopic ultrasound showed the lesion arose from the muscular layer and was misdiagnosed as leiomyoma. The blood flow was not obvious, and the lesion was near the aorta; B: The submucosal tumor located in the middle of the thoracic esophagus; C: A submucosal tunnel was created; D: The tumor was dissected from the muscular layer in the submucosal tunnel; E: Closure of the submucosal tunnel with clips; F: The excised lesion.

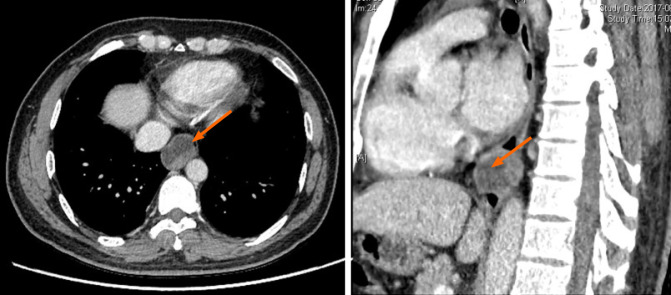

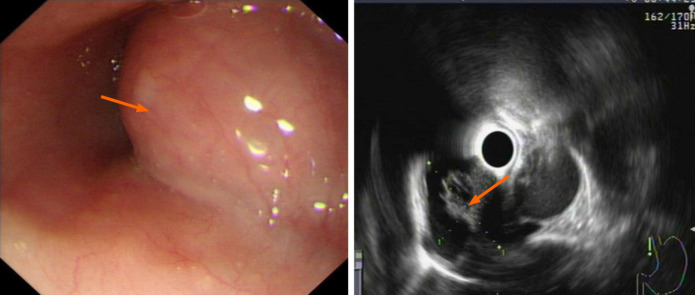

Case 3: Computed tomography of the chest (Figure 3) showed an oval mass located in the lower esophagus with features suggestive of neurogenic or gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Endoscopy examination revealed a 28 mm × 22 mm submucosal lesion 35 cm from the incisors. EUS showed the lesion arose from the muscular layer with cystic changes (Figure 4) and was misdiagnosed as solid cystic tumor.

Figure 3.

Case 3 Chest computed tomography showed a large mass located in the thoracic esophagus suspected to be a neurogenic tumor or a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (arrow).

Figure 4.

Case 3 Endoscopy revealed a 28 mm × 22 mm submucosal lesion. Endoscopic ultrasound showed the lesion was derived from the muscular layer with cystic changes and was misdiagnosed as a cystic solid tumor.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

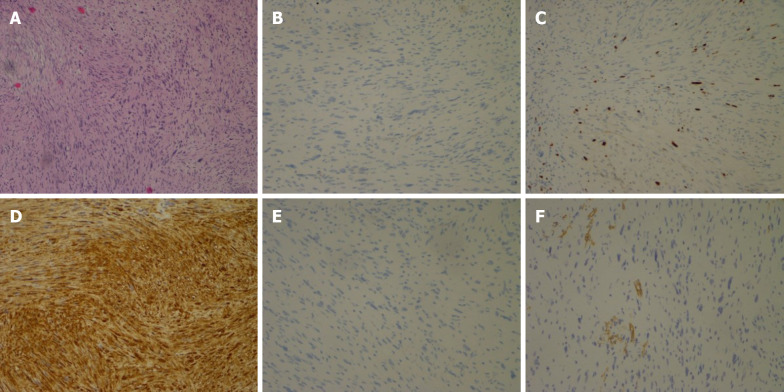

Immunohistochemical studies showed positive staining of the tumor cells for S-100, Lea-7, and PG9.5 protein, and negative staining for CD117, CD34, Dog-1, Des, and smooth muscle actin. The mitotic activity was 5-15 mitosis/50 high-power field. These findings supported a diagnosis of cellular gastrointestinal type schwannoma (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Endoscopic submucosal excision performed. A: Histopathological examination of the tumor in case 1 showed spindle-shaped cells arranged in bundles; B: Immunochemical analysis revealed no staining with CD117; C: Focal positivity with CD34; D: Positive staining with S100; E: DOG-1; F: The mitotic activity was 3 mitosis/50 high-power field on Ki-67 staining.

TREATMENT

Case 1

We recommended surveillance to the patient, but he insisted on endoscopic resection. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient before the operation.

The patient underwent ESE under general anesthesia. Intravenous antibiotics were administered 0.5 h before the procedure. The operation was performed using a single-channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J, Olympus). Other equipment and accessories included a high-frequency electric cutting device (VIO 200s , ERBE), an endoscopic carbon dioxide regulation unit (Olympus), an endoscopic flushing pump (Olympus), a transparent cap (NM-200L-0521, Olympus), an injection needle (SD-230U-20, Olympus), a dual knife (KD-650L, Olympus), an insulated-tip knife (KD-611L, IT2, Olympus), a double-helix snare (HX-610-135L, Olympus), hemostatic clips (HX-600-135, Olympus), and a coagrasper (FD-410LR, Olympus).

The steps for ESE performed in this case were as follows (Figure 6): (1) Marking the location of the lesion (Figure 6B): Coagulation was used to mark both the oral and aboral ends of the target lesion; (2) Submucosal injection: A mixed solution of saline, indigo carmine, and epinephrine was injected into the submucosa to elevate the lesion; (3) Visualization of the lesion (Figure 6C): The covering mucosa was incised longitudinally using dual knife followed by separation of the submucosa to reveal the tumor; (4) Peeling of the lesion (Figure 6D): The lesion edge was stripped with an IT2 knife to avoid damage to the tumor or the tumor capsule; and (5) Wound closure (Figure 6E): We performed en bloc resection of the lesion. After achieving hemostasis, the mucosal incision was closed with clips to avoid wound bleeding or perforation after surgery.

Figure 6.

Case 1 Steps of endoscopic submucosal excavation. A: The submucosal tumor; B: Marking the submucosal tumor with an argon knife; C: Revealing the submucosal tumor; D: Peeling the lesion; E: Closing the mucosal incision site with clips; F: The resected specimen.

Case 2

As esophageal leiomyoma can be resected endoscopically, we used the STER technique to resect the lesion under general anesthesia. Intravenous antibiotic was used in a similar way to the procedure in case 1. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient before the operation. The equipment and accessories were similar to those used in case 1.

The detailed steps for STER have been described previously by Chen et al[17]. In the present case, the procedure was modified as follows: (1) Submucosal injection: A mixed solution of saline and epinephrine was injected about 3-4 cm proximal to the oral end of the tumor; (2) Construction of a submucosal tunnel (Figure 2C): A 2 cm longitudinal mucosal incision was made, and a longitudinal tunnel between the submucosal and muscular layers was then created using a dual knife; (3) Exposure of the tumor: The tunnel was continued downwards with the dual knife until the tumor was exposed; (4) Resection of the tumor (Figure 2D): Separation of the muscular layer was performed using an IT2 knife. The tumor was removed safely and completely without injuring the tumor capsule; (5) Hemostasis: After tumor resection, a coagrasper was used to coagulate small vessels; and (6) Closure of the mucosal incision site (Figure 2E): The entry site was closed with clips.

Case 3

Because the pathological nature of the submucosal tumor was not clear, we recommended the patient undergo surgical excision. However, the patient refused to undergo thoracic surgery and insisted on endoscopic minimally invasive resection. We resected the lesion by using the STER technique under general anesthesia. As the tunnel space was limited and the tumor was large with cystic changes, we had to remove it in a piecemeal fashion. The operation time was 3 h.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

The lesion was located deep in the muscular layer, which caused subcutaneous emphysema and oxyhemoglobin saturation decline during the operation. After wound closure, oxyhemoglobin saturation returned to normal. Gastric decompression was performed for 48 h postoperatively. Two days later, the nasogastric tube was removed, and the patient was started on a liquid diet. No late bleeding, inflammation, or infection occurred after the operation. Immunohistochemical studies led to a diagnosis of esophageal schwannoma. On follow-up endoscopy at 3 mo and 6 mo, the wound had healed. At 54 mo after the operation, the patient remained disease-free.

Case 2

The patient tolerated a liquid diet 24 h after the operation without any discomfort. No late bleeding, inflammation, or infection occurred after the operation. Immunohistochemical studies strongly supported a diagnosis of esophageal schwannoma. On follow-up endoscopy at 3 mo and 6 mo, the wound had healed. At 48 mo after the operation, the patient remained disease-free.

Case 3

The patient had a fever after the operation. After 3 d of antibiotics, the patient became afebrile. As en bloc endoscopic resection could not be performed, the patient was recommended to undergo additional surgery but refused further treatment.

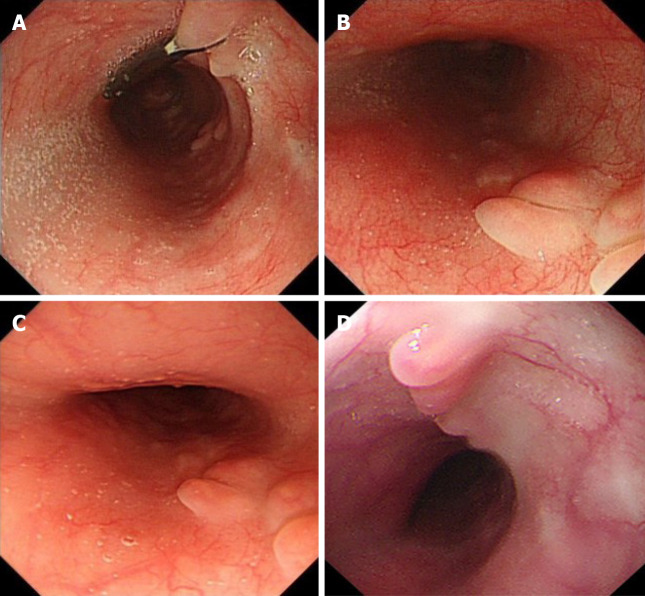

On follow-up endoscopy at 3 mo and 6 mo, the wound had healed with no residual disease. At 24 mo after surgery, the patient was disease-free with no local recurrence (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Case 3 Endoscopic follow-up after the endoscopic operation. A: Residual titanium clip; B: Mucosal scarring was observed at 3 mo. C: Mucosal scarring at 12 mo after the endoscopic operation; D: Mucosal scarring at 24 mo after the endoscopic operation.

DISCUSSION

Schwannoma is a rare esophageal tumor. It was first described in 1967 by Ferrante et al[8]. By the year 2000, only 15 cases had been reported in the English literature[18]. Additionally, only 42 such cases were reported in Japan up to 2011[13]. Very few (4 out of 30) cases of esophageal schwannomas reported up to 2012 were found to have malignant characteristics[19]. Typically, dyspnea and dysphagia are the most common complaints. Other reported signs and symptoms include chest pain, stridor, hematemesis, cough, and a palpable neck mass[20]. There was a report of superior vena cava compression associated with esophageal schwannoma[21]. The youngest case of esophageal schwannoma, reported by Choo et al[20] was that of a 22-year-old Asian American man with dyspnea and progressive dysphagia. The median doubling time for schwannoma is about 104.7 mo. In contrast, the doubling time for GIST is 17.2 mo[22].

In a literature review, we found that benign schwannomas occurred more frequently in middle-aged women and are usually located in the upper esophagus. There are no distinctive features to differentiate schwannomas from other submucosal tumors on computed tomography[7,23]. On positron emission tomography computed tomography, there is positive uptake of (18F)-fluorodeoxyglucose in benign schwannoma[13]. EUS is widely used to diagnose submucosal tumors because of its superiority to other modalities (computed tomography and endoscopy)[24]. Standard EUS is useful for determining the origin and the exact location of lesions within different layers of the esophageal wall (mucosal C1 and C2, submucosal C3, and muscularis C4 types) but has poor accuracy (between 30% and 66%)[25,26]. Schwannoma located in the second layer (C2 type) can be easily resected using endoscopic techniques[12,16]. However, in this series, we found most schwannomas were located in the third or fourth layer (C3 to C4 types). It is often very difficult to differentiate lesions in the fourth layer, and a small ultrasound probe is helpful for making the diagnosis. On EUS, typical neurogenic tumors appear as round or oval hypoechoic homogeneous masses originating from the muscularis propria with slightly higher echogenicity compared to GISTs[27]. No enhancement is seen in schwannomas on contrast-enhanced EUS[24]. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA) has been reported to be useful for both diagnosis and management[28]. However, for small submucosal tumors (< 2 cm) as in cases 1 and 2, EUS-FNA usually provides only a cytologic specimen and fails to provide a histological specimen, mainly because of insufficient material[29]. We did not perform EUS-FNA for case 3 in this study because the tumor was mostly cystic in nature.

In the majority of reported cases, definitive diagnosis was made by pathological examination of the resected lesions. Histologically, the tumor consisted of spindle-shaped tumor cells arranged in a palisading pattern or with loose cellularity in a reticular array. Immunohistochemically, the tumors showed positive staining with S100 protein positivity. Other markers such as α smooth muscle actin, CD34, and CD117 were also useful for differentiation from other submucosal tumors[4,30].

The treatment of asymptomatic patients with benign esophageal submucosal tumors remains controversial[9]. With recent advances in endoscopic technology, submucosal tumors of the esophagus can be treated by endoscopic resection. Liu et al[31] reported an esophageal schwannoma excised by tunneling endoscopic muscularis dissection. After complete excision, the prognosis of schwannoma is generally good and recurrence is rare[32].

There are very few reported cases of malignant esophageal schwannoma[33]. In these cases, regional lymph node dissection was performed, and the patients did not experience any recurrence. Only one case of recurrence after complete resection has been reported[33]. When an esophageal submucosal tumor is suspected to be malignant based on clinical or radiographic findings (such as local invasion or enlarged suspicious lymph nodes), surgical excision with lymph node dissection should be considered[34]. There is no role for adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy after complete resection of schwannoma. Similarly, for large esophageal submucosal tumors (> 3 cm) with suspicious features (e.g., irregular borders, inhomogeneous lesion, cystic spaces, or echogenic foci) on EUS, surgery should be considered[24]. However, the clinical management of smaller submucosal tumors (< 2 cm or 3 cm) is not straightforward, especially when EUS–FNA cannot provide an accurate diagnosis. Due to misdiagnosis, there can be difficulties in the follow-up treatment. Further, the deep location of the lesion in one of our patients led to perforation during the operation. Another patient with a large lesion size had adhesions with the surrounding structures. Because of these adhesions, we failed to perform en bloc endoscopic resection, and the patient developed a fever after the operation.

In this series, we resected one lesion using ESE, and the other two cases were resected with STER. Perforation of the esophageal wall occurred in the first case resected by ESE because the lesion was located deep in the muscular layer. To remove the tumor completely, full-thickness injury of the muscle layer occurred, resulting in perforation and subcutaneous emphysema. Hence, we performed STER in the subsequent two cases. The advantage of STER is that it ensures the integrity of the mucosal layer above the lesion, but the operative time is longer. It is also difficult to create a submucosal tunnel for cervical and upper thoracic esophageal lesions. Moreover, for larger lesions (> 3 cm), it may be difficult to dissect around the lesion due to adhesions and limited space. Hence, the type of endoscopic procedure should be carefully selected with all these factors in mind.

In the last two cases, one was resected en bloc using STER, and the other was resected in a piecemeal fashion because of the large size and limited tunnel space. However, throughout the follow-up period, no tumor recurrence or metastasis occurred. Based on our experience, we believe that for larger lesions (transverse diameter > 28 mm), especially tumors with cystic degeneration, endoscopic treatment may not be suitable. For such lesions, endoscopic treatment combined with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery may be a better option[35,36].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, esophageal schwannoma are rare submucosal lesions. Small lesions in a suitable location can be removed endoscopically by experienced endoscopists using the ESE or STER technique.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: All data published here are under consent for publication. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The written consent mentioned here is for the publication of patient/clinical details.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All other authors have nothing to disclose.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: June 23, 2020

First decision: July 24, 2020

Article in press: October 19, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tsuji Y S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Bin Li, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250012, Shangdong Province, China.

Xue Wang, Department of Gastroenterology,Dezhou People’s Hospital, Dezhou 253014, Shangdong Province, China.

Wen-Lu Zou, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan 250012, Shangdong Province, China.

Shu-Xia Yu, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250012, Shangdong Province, China.

Yong Chen, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250012, Shangdong Province, China.

Hong-Wei Xu, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250012, Shangdong Province, China. xhongwei808@163.com.

References

- 1.Zhang W, Xue X, Zhou Q. Benign esophageal schwannoma. South Med J. 2008;101:450–451. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181683fd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu SD, Cheng YL, Chen A, Lee SC. Esophageal schwannoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2003;102:346–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozak K, Kowalczyk M, Jesionek-Kupnicka D, Kozak J. Benign intramural schwannoma of the esophagus - case report. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2015;12:69–71. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2015.50574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitada M, Matsuda Y, Hayashi S, Ishibashi K, Oikawa K, Miyokawa N. Esophageal schwannoma: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:253. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Zheng J, Ruan Z, Huang H, Yang Z, Zheng J. Long-term survival in a rare case of malignant esophageal schwannoma cured by surgical excision. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:357–358. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park BJ, Carrasquillo J, Bains MS, Flores RM. Giant benign esophageal schwannoma requiring esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:340–342. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souza LCA, Pinto TDA, Cavalcanti HOF, Rezende AR, Nicoletti ALA, Leão CM, Cunha VC. Esophageal schwannoma: Case report and epidemiological, clinical, surgical and immunopathological analysis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;55:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.10.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrante M, Khan A, Fan C, Jelloul FZ. Schwannoma of the cervical esophagus. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5361. doi: 10.4081/rt.2014.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang SK, Yun JS, Kim SH, Song SY, Jung Y, Na KJ. Retrospective analysis of thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal submucosal tumors. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:40–45. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2015.48.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koizumi H, Aoyama N, Ishibashi M. Some devices for endoscopic resection of the esophageal submucosal tumors. Shoukaki Naishikyou no Shinpo (Prog Dig Endosc) 1987;31:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konishi M, Yamaguchi H, Yoshida S. Endoscopic and clinicopathological features of esophageal submucosal tumors. Shoukaki Naishikyou no Shinpo (Prog Dig Endosc) 1989;35:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naus PJ, Tio FO, Gross GW. Esophageal schwannoma: first report of successful management by endoscopic removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:520–522. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato S, Takagi M, Watanabe M, Nagai E, Kyoden Y, Ohata K, Oba N, Suzuki M, Fukuchi K, Iseki JJE. A case report of benign esophageal schwannoma with FDG uptake on PET-CT and literature review of 42 cases in Japan. Esophagus . 2012;9:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigdeli MR. Neuroprotection caused by hyperoxia preconditioning in animal stroke models. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:403–421. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimamura Y, Winer S, Marcon N. A Schwannoma of the Distal Esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:A19–A20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trindade AJ, Fan C, Cheung M, Greenberg RE. Endoscopic resection of an esophageal schwannoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:309. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen T, Zhou PH, Chu Y, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Ji Y, Yao LQ, Xu MD. Long-term Outcomes of Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection for Upper Gastrointestinal Submucosal Tumors. Ann Surg. 2017;265:363–369. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito R, Kitamura M, Suzuki H, Ogawa J, Sageshima M. Esophageal schwannoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1947–1949. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassis ES, Bansal S, Perrino C, Walker JP, Hitchcock C, Ross P Jr, Daniel VC. Giant asymptomatic primary esophageal schwannoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:e81–e83. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choo SS, Smith M, Cimino-Mathews A, Yang SC. An early presenting esophageal schwannoma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:165120. doi: 10.1155/2011/165120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Favre-Rizzo J, Lopez-Tomassetti Fernandez E, Sánchez-Ramos M, Hernandez-Hernandez JR. Esophageal schwannoma associated with superior vena cava syndrome. Cir Esp. 2016;94:108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koizumi S, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Okuwaki K, Iwai T, Miyazawa S, Takezawa M, Imaizumi H, Koizumi W. Clinical implications of doubling time of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10015–10023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i45.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang KM, Lee KS, Lee SJ, Kim EA, Kim TS, Han D, Shim YM. The spectrum of benign esophageal lesions: imaging findings. Korean J Radiol. 2002;3:199–210. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2002.3.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pesenti C, Bories E, Caillol F, Ratone JP, Godat S, Monges G, Poizat F, Raoul JL, Ries P, Giovannini M. Characterization of subepithelial lesions of the stomach and esophagus by contrast-enhanced EUS: A retrospective study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:43–49. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_89_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddymasu SC, Oropeza-Vail M, Pakseresht K, Moloney B, Esfandyari T, Grisolano S, Buckles D, Olyaee M. Are endoscopic ultrasonography imaging characteristics reliable for the diagnosis of small upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:42–45. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318226af8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karaca C, Turner BG, Cizginer S, Forcione D, Brugge W. Accuracy of EUS in the evaluation of small gastric subepithelial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong DD, Wang CH, Xu JH, Chen MY, Cai JT. Endoscopic ultrasound features of gastric schwannomas with radiological correlation: a case series report. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7397–7401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinoshita K, Isozaki K, Tsutsui S, Kitamura S, Hiraoka S, Watabe K, Nakahara M, Nagasawa Y, Kiyohara T, Miyazaki Y, Hirota S, Nishida T, Shinomura Y, Matsuzawa Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in follow-up patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1189–1193. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philipper M, Hollerbach S, Gabbert HE, Heikaus S, Böcking A, Pomjanski N, Neuhaus H, Frieling T, Schumacher B. Prospective comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and surgical histology in upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Endoscopy. 2010;42:300–305. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuki A, Kosugi S, Kanda T, Komukai S, Ohashi M, Umezu H, Mashima Y, Suzuki T, Hatakeyama K. Schwannoma of the esophagus: a case exhibiting high 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography imaging. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:E6–E10. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu BR, Song JT, Kong LJ, Pei FH, Wang XH, Du YJ. Tunneling endoscopic muscularis dissection for subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4354–4359. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen HC, Huang HJ, Wu CY, Lin TS, Fang HY. Esophageal schwannoma with tracheal compression. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;54:555–558. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murase K, Hino A, Ozeki Y, Karagiri Y, Onitsuka A, Sugie S. Malignant schwannoma of the esophagus with lymph node metastasis: literature review of schwannoma of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:772–777. doi: 10.1007/s005350170020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moro K, Nagahashi M, Hirashima K, Kosugi SI, Hanyu T, Ichikawa H, Ishikawa T, Watanabe G, Gabriel E, Kawaguchi T, Takabe K, Wakai T. Benign esophageal schwannoma: a brief overview and our experience with this rare tumor. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:97. doi: 10.1186/s40792-017-0369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Han Y, Xiang J, Li H. Robot-assisted enucleation of large dumbbell-shaped esophageal schwannoma: a case report. BMC Surg. 2018;18:36. doi: 10.1186/s12893-018-0370-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onodera Y, Nakano T, Takeyama D, Maruyama S, Taniyama Y, Sakurai T, Heishi T, Sato C, Kumagai T, Kamei T. Combined thoracoscopic and endoscopic surgery for a large esophageal schwannoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8256–8260. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i46.8256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]