Abstract

In recent years hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has demonstrated vasculoprotective effects against cell death, which suggests its promising therapeutic potential for numerous types of disease. Additionally, a protective effect of exogenous H2S in HG-induced injuries in HUVECs was demonstrated, suggesting a potential protective effect for diabetic vascular complications. The present study aimed to investigate the mechanism accounting for the cytoprotective role of exogenous H2S against high glucose [HG (40 mM glucose)]-induced injury and inflammation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). HUVECs were exposed to HG for 24 h to establish an in vitro model of HG-induced cytotoxicity. The cells were pretreated with sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), a donor of H2S, or inhibitors of necroptosis and p38 MAPK prior to the exposure to HG. Cell viability, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, phosphorylated-(p)38 and receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3) expression levels were detected using the indicated methods, including Cell Counting Kit 8, fluorescence detection, western blotting, immunofluorescence assay and ELISAs. The results demonstrated that necroptosis and the p38 MAPK signaling pathway mediated HG-induced injury and inflammation. Notably, NaHS was discovered to significantly ameliorate p38 MAPK/necroptosis-mediated injury and inflammation in response to HG, as evidenced by an increase in cell viability, a decrease in ROS generation and loss of MMP, as well as the reduction in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, the upregulated expression of RIP3 induced by HG was repressed by treatment with SB203580, while the HG-induced upregulation of p-p38 expression levels were significantly downregulated following the treatment of Nec-1 and RIP3-siRNA. In conclusion, the findings of the present study indicated that NaHS may protect HUVECs against HG-induced injury and inflammation by inhibiting necroptosis via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, which may represent a promising drug for the therapy of diabetic vascular complications.

Keywords: sodium hydrosulfide, hyperglycemia, necroptosis, p38 MAPK, human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, which is characterized by hyperglycemia, affects >415 million people worldwide (1). The condition is a significant economic burden and seriously affects the quality of life of diabetic patients (2). Owing to hyperglycemia, the dysfunction of the vascular endothelium may lead to vascular lesions and cause further severe implications, such as retinopathy (3), diabetic nephropathy (4), cardiovascular disease (5,6) and neuropathy (7). Previous studies have reported that multiple factors, including mitochondrial dysfunction (8), oxidative stress (9) and the activity of various signaling molecules, such as sirtuin 1 (10) and p53 (11), were implicated in the high glucose [HG (40 mM glucose)]-induced dysfunction of the vascular endothelium. Accumulating evidence has suggested that p38 MAPK may be associated with diabetic complications; for example, Song et al (12) discovered that the p38 signaling pathway mediated renal injury in diabetic nephropathy model mice. Furthermore, the activation of p38 MAPK was identified in HK-2 cells stimulated with HG, while the inhibition of p38 MAPK exerted a protective role over cell function (13). Notably, inflammation has also been considered as a crucial player in the development of diabetic mellitus, especially in vascular disorders (14–16). In addition, accumulating studies have reported that p38 MAPK contributed to the inflammatory process (17–19). However, to the best of our knowledge, whether p38 MAPK contributes to HG-induced injury and inflammation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) remains poorly understood. Thus, it is of great significance to further determine the mechanism of hyperglycemia-induced injury and inflammation in order to develop effective therapeutic options for diabetes mellitus.

Necroptosis, which is also known as programmed necrosis, has been demonstrated to serve a role in homeostasis, inflammation and immunity (20–22). Receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3) is the key determinant in necroptosis pathway transduction (23,24). Numerous previous studies have demonstrated that necroptosis was involved in cytokine-induced cell death (25–27). In addition, RIP3 knockout in vivo alleviated severe inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (28). The findings of our previous study also suggested that necroptosis was responsible for HG-induced injury (29). Interestingly, the p38 MAPK pathway has been identified to contribute to necroptosis (30,31). For instance, Qin et al (31) reported that the suppression of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway contributed to the protective effects of sulforaphane in neuronal necroptosis. In another in vitro study, p38 MAPK was discovered to be activated in TNF-α-induced necroptosis (32). Accordingly, the relationship between p38 MAPK and the necroptosis pathway in HG-induced injury of HUVECs should be further investigated.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), the third gas transmitter along with nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, has attracted significant attention for its potential protective endothelial effect (33). Previous studies have revealed that H2S promoted anti-inflammatory and vasculoprotective effects in various types of disease model, such as ischemia/reperfusion injury and atherosclerosis (34–36). Administration of sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), a H2S donor, was subsequently revealed to prevent the inflammatory response, which was evidenced through the decrease in the secretory levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, in hyperhomocysteinemia rats (37). Notably, recent research has reported that the inhibition of p38 MAPK mediated by exogenous H2S was conducive to ameliorating HG-induced damage in myocardial cells (38). However, whether p38 MAPK is associated with the protective effect of H2S against HG-induced injury in HUVECs remains unclear. Therefore, the present study exposed HUVECs to 40 mM HG to establish an in vitro model of HG-induced injury and further investigated the role of p38 MAPK and necroptosis in NaHS protection in HUVECs.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

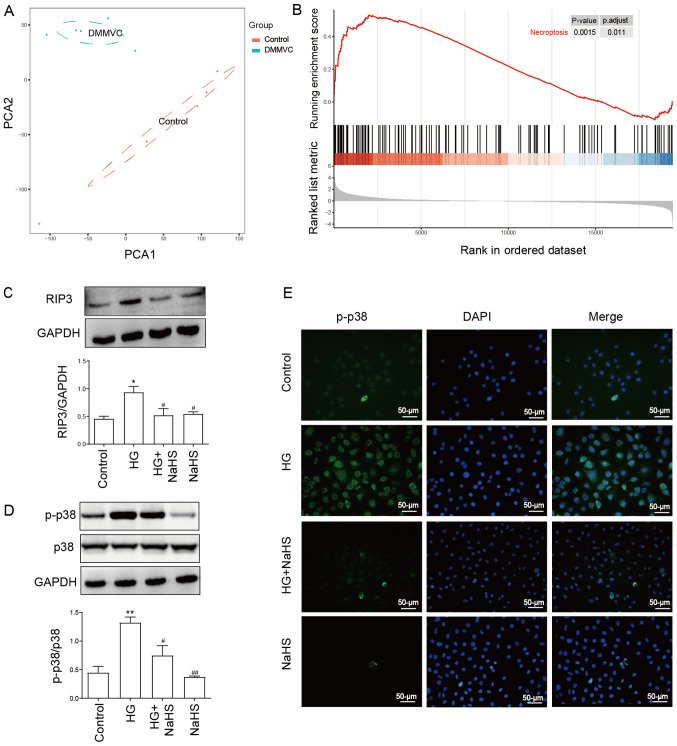

A microarray dataset (GSE43950) containing five healthy subjects and five patients with diabetes with microvascular diseases was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). Principal component analysis (PCA) of the expression levels of genes in 10 samples, including five healthy subjects and five patients with diabetes with microvascular diseases, was conducted using R package (version 3.6.3; http://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.6.3/). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of all genes was also performed using R package. P<0.05 was considered as significance cut-off levels.

Materials and reagents

NaHS, necrostatin-1 (Nec-1; RIP3 inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and rhodamine 123 (Rh123) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Glucose injection was purchased from Hunan Kelun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting RIP3 and negative control (NC) siRNA were purchased from Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. The anti-RIP3 primary antibody (cat. no. ab56164) was purchased from Abcam. Anti-p38 (cat. no. 9212S) and anti-phosphorylated (p)-p38 (cat. no. 4511S) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Anti-GAPDH primary antibody (cat. no. 10494-1-AP) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. SA00001-2) were purchased from ProteinTech Group, Inc. FITC-labelled anti-rabbit secondary antibody was purchased from Invitrogen (cat. no. F-2765; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent was obtained from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. FBS and DMEM were obtained from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. The BCA protein assay kit was obtained from Kangchen BioTech Co., Ltd. IL-1β (cat. no. CSB-E08053h), IL-6 (cat. no. CSB-E04638h), IL-8 (cat. no. CSB-E04641h) and TNF-α (cat. no. CSB-E04740h) ELISA kits were purchased from Cusabio Technology LLC. ECL solution was purchased from Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co. Ltd. RIPA lysis buffer was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. HUVECs were supplied by Guangzhou Jiniou Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Cell culture and treatments

For each treatment, HUVECs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2. To determine the protective effects of H2S on HG-induced injury, cells were pretreated with 400 µM NaHS (a well-known H2S donor) for 30 min prior to 40 mM HG for 24 h at 37°C. In order to determine the role of p38 MAPK/RIP3-mediated necroptosis pathways in HG-induced injury and inflammation, HUVECs were either pretreated with 3 µM SB203580 (an inhibitor of p38 MAPK) for 1 h prior to HG treatment or 100 µM Nec-1 (an inhibitor of necroptosis) or transfection with RIP3-siRNA for 24 h prior to HG treatment.

Cell transfection

HUVECs were cultured in 12-well-plates at a density of 1×105 cells/ml and transfected at 70% confluence with 100 nM RIP3-siRNA (5′-CCAUGGCUUGUCUGGAUAA-3′) or 100 nM NC (5′-CUAACUAUCUCGAACGCAA-3′) using Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly, each freeze-dried powder siRNA was dissolved in nuclease-free water to a final concentration of 20 µM. Then, 5 µl siRNA and 5 µl Lipofectamine reagent were added to 500 µl OptiMEM (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to form a Lipofectamine 2000/siRNA mixture. The mixture was maintained at room temperature for 30 min to form complexes, and then the mixture was added to 12-well-plates with 500 µl OptiMEM and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The medium was replaced after 24 h with DMEM with 10% FBS, which contained neither siRNA nor the transfection reagent.

Cell viability assay

HUVECs were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/ml. Following incubation at 37°C for 24 h, cells received different treatments as described in ‘cell culture and treatment’ section and then washed with PBS. Subsequently, according to the manufacturer's protocol, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Multiskan MK3 Microplate reader; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The mean optical density (OD) of 3 wells in the indicated groups was used to calculate the cell viability according to the following formula: Percentage of cell viability (%)=(OD treatment group/OD control group) ×100. The experiment was repeated 5 times.

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation

Intracellular ROS generation was measured by determining the oxidation of DCFH-DA to fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Briefly, HUVECs at a density of 1×105 cells/ml were cultured at 37°C in DMEM with 10% FBS on 6-well plates for 24 h. Following treatment as described above, cells were collected for determination of ROS generation. The cells were washed three times with PBS. Then, 10 µM DCFH-DA solution in serum-free DMEM was added to the slides and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were washed 5 times with PBS and DCF fluorescence was measured over the entire field of vision using a fluorescence microscope at ×40 magnification connected to an imaging system (BX50-FLA; Olympus Corporation). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) from five random fields, which is used an index for ROS production, was analyzed using ImageJ (1.47i software; National Institutes of Health). The experiment was repeated 5 times.

Examination of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

The MMP was analyzed using a fluorescent dye named Rh123. The depolarization of the MMP results in a loss of MMP and a decrease in green fluorescence (39). Briefly, HUVECs at a density of 1×105 cells/ml were cultured at 37°C in DMEM with 10% FBS on 6-well plates for 24 h. Following treatment as described above, cells were collected for examination of MMP. The cells were washed three times with PBS. The cells were subsequently incubated with 1 µM Rh123 at 37°C for 30 min in an incubator and then washed briefly with PBS 5 times. Fluorescence was then measured over the entire field of vision using a fluorescence microscope at ×40 magnification connected to an imaging system (BX50-FLA). The MFI of Rh123 from 5 randomly selected fields of view was analyzed using ImageJ software, and the MFI indicated the levels of MMP. The lower MFI, the higher loss of MMP. The experiment was repeated 5 times.

Western blotting

Following treatment, the HUVECs were harvested via centrifugation for 5 min at 300 × g at 4°C and lysed with RIPA lysis buffer for 30 min at 4°C. Total protein was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit and 30 µg protein/lane was separated via 12% SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane and blocked with 5% free-fat milk for 90 min at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4°C overnight with gentle agitation: Anti-RIP3 (1:1,000), anti-p38 (1:1,000) and anti-p-p38 (1:1,000) or anti-GAPDH (1:5,000). Following incubation with the primary antibody, the membranes were washed with 0.1% TBS Tween-20 and then incubated with the secondary antibody (1:5,000) for 60 min at room temperature. The membranes were washed with 0.1% TBS Tween-20 and protein bands were visualized using ECL and exposure to X-ray films. To semi-quantify protein expression levels, the X-ray films were scanned and analyzed with ImageJ software. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Immunofluorescence assay

HUVECs at a density of 1×105 cells/ml were cultured at 37°C in DMEM with 10% FBS on glass coverslips for 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at temperature, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked with 1% BSA (Seebio; http://www.seebio.cn) for 20 min at room temperature. The slides were subsequently incubated with the anti-p-p38 primary antibody (1:200) overnight at 4°C. Following the primary antibody incubation, the glass coverslips were washed with 0.1% PBS-Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated with a FITC-labelled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000) for 1 h at 37°C, then washed by PBST and stained with DAPI for 5 min at temperature. Stained cells were visualized using a fluorescence microscope at ×40 magnification (Axio Imager Z1).

Measurement of the secretory levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-a using ELISAs

HUVECs were cultured in 96-well growth-medium plates at 37°C for 24 h. Then, after receiving different treatments as described above, the secretory levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-a in the culture supernatant, which were acquired via centrifuging at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, were analyzed using their respective ELISA kits, according to the manufacturers' protocols. The experiment was performed 5 times.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences between groups were determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by a LSD post-hoc test for 3 groups and by a Tukey's post-hoc test for ≥3 groups using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Data in each experiment were obtained from at least three independent experimental repeats.

Results

NaHS attenuates HG (40 mM glucose)-induced upregulation of RIP3 and p-p38 expression levels in HUVECs

As shown in Fig. 1A, PCA of the GSE43950 dataset was performed. The results revealed an obvious separation between healthy controls and patients with diabetes with microvascular diseases. The results of the GSEA in Fig. 1B identified that the necroptosis pathway was enriched in samples with diabetes with microvascular disease compared with healthy controls, implying the significant role of the necroptosis pathway in diabetes with vasculopathy. In addition, our previous study demonstrated that necroptosis contributed to HG-induced injury (29). The present results revealed that HUVECs treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h significantly upregulated the expression levels of RIP3 and p-p38/p38 compared with the control group, as detected using western blotting (Fig. 1C and D). According to our previous study, 400 µM NaHS was determined as the effective therapeutic dose for treatment of HUVECs without promoting cell cytotoxicity (29). Thus, the present study also used 400 µM NaHS for cell treatment. To determine the effect of NaHS on the HG-induced necroptosis and the activity of p38, HUVECs were pretreated with 400 µM NaHS for 30 min prior to exposure to HG. The treatment of cells with 400 µM NaHS for 30 min before exposure to HG significantly downregulated the upregulated expression levels of RIP3 and p-p38/p38 induced by HG (Fig. 1C and D). However, the treatment with 400 µM NaHS alone did not affect the expression levels of RIP3 and p-p38/p38 compared with the control group. In addition, an immunofluorescence assay was performed with HUVECs. Similarly, the results in Fig. 1E revealed that p-p38 expression levels were upregulated by HG treatment, which were subsequently markedly reduced in HUVECs pretreated with 400 µM NaHS. These findings suggested that NaHS may inhibit HG-induced necroptosis and the activity of p38 in HUVECs.

Figure 1.

Exogenous NaHS attenuates the HG-induced upregulation of the expression levels of RIP3 and p-p38 in HUVECs. (A) PCA of the GSE43950 dataset obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Samples including DMMVC and control were separated into two cluster. (B) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis for all genes in the GSE43950 dataset. Genes involved in the necroptosis pathway were enriched in diabetes with microvascular diseases. Expression levels of (C) RIP3 and (D) p-p38/p38 ratio were analyzed and semi-quantified using western blotting. HUVECs were pretreated with or without 400 µM NaHS for 30 min prior to exposure to 40 mM HG. (E) Representative micrographs of immunofluorescence staining of HUVECs with an anti-p-p38 antibody (green) and the fluorescent nuclear stain DAPI (blue) following the indicated treatments. Scale bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, vs. HG group. RIP3, receptor-interacting protein 3; p-, phosphorylated; PCA, principal component analysis; DMMVC, diabetes with microvascular disease; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; HG, high glucose.

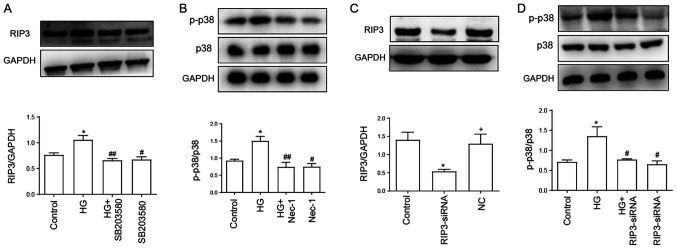

Identification of a positive feedback loop between p38 MAPK and necroptosis pathways in HUVECs

As shown in Fig. 2A, the expression levels of RIP3 were significantly upregulated following the treatment with 40 mM HG compared with the control group. However, the upregulated expression levels of RIP3 were suppressed by the treatment with SB203580 (Fig. 2A), the inhibitor of p38 MAPK pathway, which indicated that HG may mediate necroptosis through activating the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. In addition, administration of SB203580 alone had no effect on RIP3 expression.

Figure 2.

Positive feedback loop between p38 MAPK and necroptosis pathways in HUVECs. (A) Expression levels of RIP3 were semi-quantified by western blotting analysis. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without pretreatment with 3 µM SB203580 for 1 h. (B) Expression levels of p-p38/p38 were analyzed using western blotting. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without pretreatment with 100 µM Nec-1 for 24 h. (C) Transfection efficiency of RIP3-siRNA in HUVECs was determined using western blotting. (D) Expression levels of p-p38/p38 were determined using western blotting with or without RIP3-siRNA transfection. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. HG group; +P<0.05 vs. RIP3-siRNA group. RIP3, receptor-interacting protein 3; p-, phosphorylated; HG, high glucose; Nec-1, necrostatin-1; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control.

In addition, the HG-induced upregulation of p-p38/p38 expression levels were significantly downregulated following Nec-1 treatment, while treatment with Nec-1 alone had no effect on p-p38 and p38 expression levels (Fig. 2B). The transfection efficiency of RIP3-siRNA was subsequently verified; the expression levels of RIP3 were downregulated by ~60% in the RIP3-siRNA group compared with the control and negative control groups (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the expression ratio of p-p38/p38 was analyzed while inhibiting necroptosis via RIP3-siRNA. The transfection of RIP3-siRNA promoted a significant downregulation in the p-p38/p38 expression ratio compared with the HG group (Fig. 2D). Thus, these results suggested the existence of a positive feedback loop between the necroptotic and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, which may serve an important role in HG-induced injury.

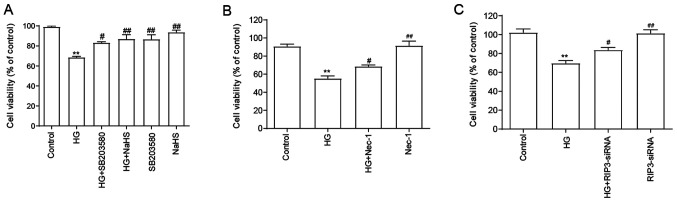

NaHS protects HUVECs against HG-induced cytotoxicity by inhibiting necroptosis and p38 MAPK signaling pathway activation

As shown in Fig. 3A, compared with the HG group, the cell viability was significantly increased following the pretreatment with NaHS, indicating that NaHS may exert cytoprotective effects in HG-induced injury. Since it was demonstrated that the expression levels of RIP3 and the p-p38/p38 expression ratio were upregulated by HG, the role of RIP3 and p38 in the HG-induced cytotoxicity was subsequently investigated. Thus, HUVECs were subsequently treated with SB203580 (Fig. 3A), Nec-1 (Fig. 3B) and RIP3-siRNA (Fig. 3C). The results suggested that all of treatments/transfections in HUVECs treated with HG significantly reversed the HG-induced cytotoxicity, suggesting that both necroptosis and p38 MAPK may be involved in HG-induced cytotoxicity. When administered alone, NaHS, SB203580, Nec-1 and RIP3-siRNA did not affect the viability of HUVECs.

Figure 3.

Role of necroptosis and p38 MAPK inhibition in the protective effects of H2S against HG-induced cytotoxicity in HUVECs. (A) HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without the pretreatment with 400 µM NaHS for 30 min or 3 µM SB203580 (the inhibitor of p38) for 60 min and the cell viability was analyzed using a CCK-8 assay. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without pretreatment with (B) 100 µM Nec-1 or transfection with (C) RIP3-siRNA for 24 h and the cell viability was analyzed using a CCK-8 assay. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=5). **P<0.01 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. HG group. NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; HG, high glucose; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein 3; siRNA, small interfering RNA; Nec-1, necrostatin-1.

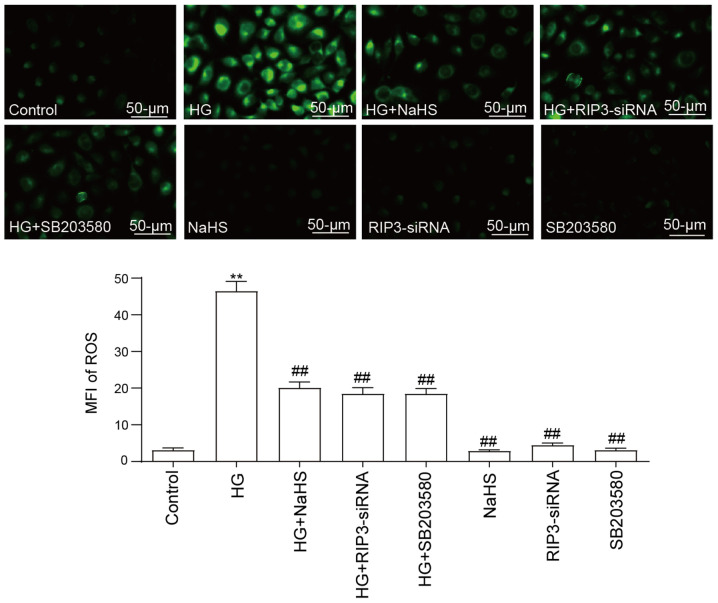

NaHS protects HUVECs against HG-induced ROS generation by inhibiting necroptosis and p38 MAPK activation

The treatment of HUVECs with 40 mM HG was discovered to significantly increase ROS generation compared with the control group (Fig. 4). Notably, the pretreatment with 400 µM NaHS significantly decreased the production of ROS induced by HG. Furthermore, both RIP3-siRNA transfection and SB203580 treatment prior to HG treatment could significantly attenuate the ROS generation compared with the HG group. However, neither RIP3-siRNA, NaHS nor SB203580 treatment alone influenced ROS generation compared with the control group.

Figure 4.

Role of necroptosis and p38 MAPK inhibition in the protective effects of NaHS against HG-induced ROS generation in HUVECs. After the HUVECs were treated with the indicated treatments, intracellular ROS generation was measured using 2′7′-dichlorodihydrofluoresein diacetate staining followed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=5). **P<0.01 vs. control group; ##P<0.01 vs. HG group. NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; HG, high glucose; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein 3; siRNA, small interfering RNA; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

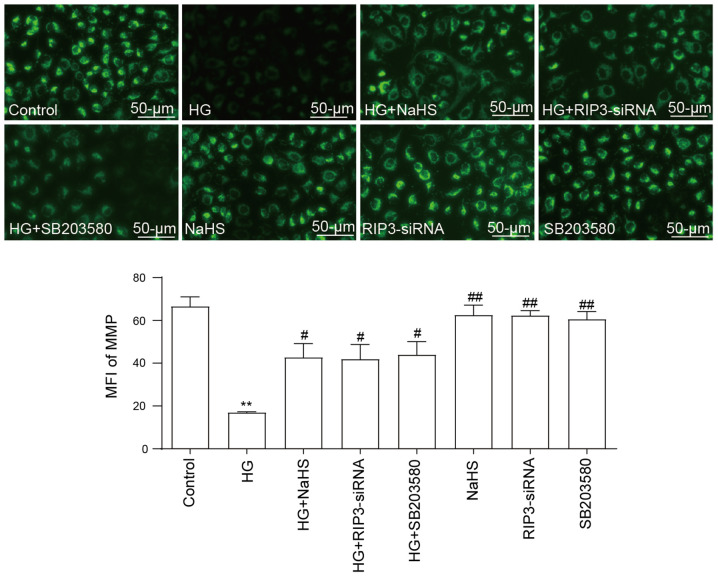

NaHS protects HUVECs against HG-induced loss of MMP by inhibiting necroptosis and p38 MAPK activation

As illustrated in Fig. 5, HG promoted a significant decrease in the MMP compared with the control group, indicating that HG may induce mitochondrial damage. However, the loss of MMP was significantly reversed by the pretreatment with 400 µM NaHS. Similarly, following the transfection with RIP3-siRNA or pretreatment with SB203580, the HG-induced loss of MMP also could be inhibited, which suggested that both necroptosis and p38 MAPK may contribute to HG-induced MMP loss. In addition, administration of NaHS, RIP3-siRNA and SB203580 did not elicit a loss of MMP.

Figure 5.

Role of necroptosis and p38 MAPK inhibition on the protective effects of NaHS against the HG-induced loss of MMP in HUVECs. After the HUVECs were treated with the indicated treatments, the MMP was analyzed using the fluorescent dye, Rhodamine 123, followed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=5). **P<0.01 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. HG group. NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; HG, high glucose; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein 3; siRNA, small interfering RNA; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

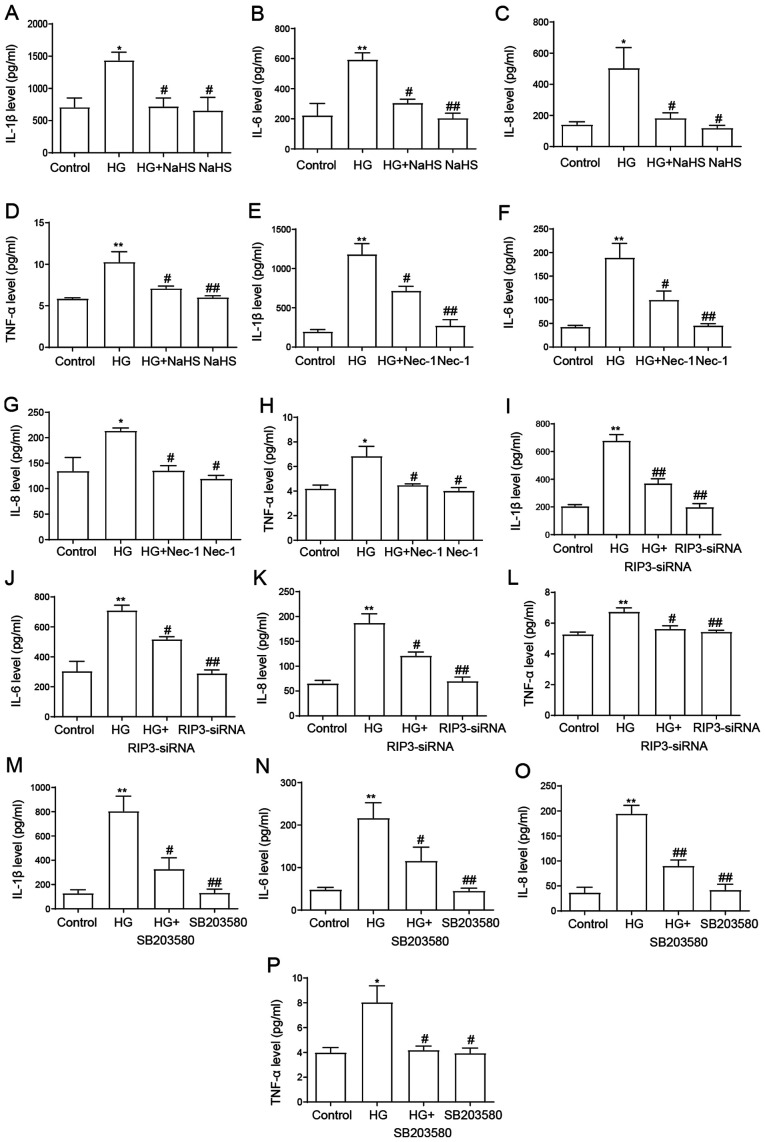

NaHS protects HUVECs against HG-induced inflammation by inhibiting necroptosis and p38 MAPK activation

Inflammatory cytokine levels were identified to be increased in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus compared with normal glucose-tolerant subjects (40). Consistent with these findings, the present results demonstrated that the secretory levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α were significantly increased following the exposure to HG compared with the control group (Fig. 6). However, the pretreatment with 400 µM NaHS prior to the exposure to HG significantly downregulated the secretory levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α compared with the HG group (Fig. 6A-D), suggesting the anti-inflammatory effect of NaHS in HG-induced inflammation. Similarly, the treatment with Nec-1 (Fig. 6E-H), the transfection with RIP3-siRNA (Fig. 6I-L) and the treatment with SB203580 (Fig. 6M-P) also ameliorated the increase in HG-induced proinflammatory cytokine secretion, further suggesting that necroptosis and the p38 MAPK signaling pathway may mediate the HG-induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in HUVECs. When administered alone, NaHS, Nec-1, RIP3-siRNA and SB203580 had no effect on the secretory levels of the cytokines. Taken together, these results indicated that NaHS may protect HUVECs against HG-induced inflammation by inhibiting necroptosis and p38 MAPK activation.

Figure 6.

Role of necroptosis and p38 MAPK inhibition on the protective effects of NaHS against HG-induced inflammation in HUVECs. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without pretreatment with 400 µM NaHS for 30 min and ELISAs were used to analyze the secretory levels of (A) IL-1β, (B) IL-6, (C) IL-8 and (D) TNF-α. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without pretreatment with 100 µM Nec-1 for 24 h and ELISAs were used to analyze the secretory levels of (E) IL-1β, (F) IL-6, (G) IL-8 and (H) TNF-α. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without transfection with RIP3-siRNA for 24 h and ELISAs were used to analyze the secretory levels of (I) IL-1β, (J) IL-6, (K) IL-8 and (L) TNF-α. HUVECs were treated with 40 mM HG for 24 h with or without pretreatment with 3 µM SB203580 for 1 h and ELISAs were used to analyze the secretory levels of (M) IL-1β, (N) IL-6, (O) IL-8 and (P) TNF-α. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=5). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. HG group. NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; HG, high glucose; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein 3; siRNA, small interfering RNA; Nec-1, necrostatin-1.

Discussion

To investigate the potential mechanism of NaHS cytoprotection, an in vitro HG-induced injury model was established in HUVECs. The findings of the present study revealed that 40 mM HG induced severe injury, including cytotoxicity, ROS generation, MMP loss, as well as inducing inflammation in HUVECs. In addition, the activation of p38 and necroptosis contributed to HG-induced injury. The protective effect of NaHS in HUVECs was found to be associated with necroptosis inhibition by repressing the activation of p38 and a positive feedback loop was identified between necroptosis and the p38 MAPK signaling pathway.

H2S has long been considered as a poisonous gas, characterized by a sharp odor of rotten eggs (41). Emerging evidence has demonstrated that H2S exerted cardioprotective and anti-atherosclerotic effects both in vivo and in vitro (35,42,43). It was previously reported that the production of H2S was reduced in diabetes patients and diabetic model mice (44). In apolipoprotein E knockout mice, H2S blocked the progression of atherosclerosis (45). Moreover, H2S improved atherosclerotic lesions via suppressing ROS induction, indicating the vasculoprotective effects of H2S. In our previous study, NaHS was found to protect HUVECs against HG-induced injury (29). Consistent with the previous findings, the present results revealed that the pretreatment with NaHS reduced cytotoxicity, ROS generation and MMP dissipation in HUVECs. Previous studies have shown that H2S exerted anti-inflammatory effects in doxorubicin-treated cardiac cells or chemical hypoxia-treated HaCaT cells (46,47). The current results identified that NaHS displayed strong anti-inflammatory properties, as evidenced by the reduced secretory levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α.

Necroptosis, also named programmed necrosis, was identified as a new form of cell death (48). Previous evidence has indicated that necroptosis was involved in the development of atherosclerosis (49), retinopathy (50) and myocardial damage (51). GSEA analysis of the GSE43950 dataset revealed a significant enrichment in the necroptosis pathway during diabetes with microvascular disease, suggesting the important role of the necroptosis pathway in diabetes with vasculopathy. Notably, in our previous study, it was discovered that necroptosis contributed to the protective effect of NaHS (29). The present study also demonstrated that HG induced injuries, including cytotoxicity, ROS production and mitochondrial injury, were subsequently ameliorated following the transfection with RIP3-siRNA or pretreatment with NaHS. Overall, these findings supported the hypothesis that NaHS may ameliorate HG-induced damage, including cytotoxicity, ROS accumulation, MMP loss and inflammation, at least in part, via inhibiting necroptosis. However, the specific mechanism remains unclear.

Cao et al (52) reported that the p38 MAPK pathway was activated in HG-induced pancreatic cancer development. In H9c2 cells, which were exposed to 35 mM glucose, p38 MAPK was found to mediate HG-induced damages, such as apoptosis, ROS overgeneration and the loss of MMP (53). Hence, the present study investigated the expression levels of p38 MAPK in HUVECs treated with HG using western blotting and immunofluorescence. Similar to the previous findings, the results revealed a significant upregulation of p-p38 expression levels following the treatment with 40 mM HG, indicating that the activation of p38 may be induced by HG exposure. A previous study demonstrated that the p38 MAPK pathway was responsible for the protective effect of H2S in HG-induced injury in H9c2 cells (53). Therefore, the current study further investigated whether the p38 MAPK pathway contributed to the protective effect of NaHS in HUVECs. The results showed that the upregulated p-p38 expression levels induced by HG were reduced following the pretreatment with NaHS, implying the regulatory effect of NaHS on p-p38 activation. Hence, these findings further suggested that p38 MAPK signaling pathway inhibition may contribute to NaHS protection in HG-induced injury. These results are consistent with previous studies. For example, it was previously reported that H2S exerted anti-inflammatory effects repressing p38 phosphorylation (54). These results suggested that the inhibition of p38 MAPK may be the main mechanism of H2S protection. Another study demonstrated that p38 was implicated in zVADfmk-mediated necroptosis (55). Thus, the role of p38 in HG-induced necroptosis was subsequently investigated. The upregulated expression levels of RIP3 induced by HG were significantly reduced following the treatment with SB203580, which indicated that p38 MAPK participated in HG-mediated necroptosis. Taken together, these above results suggested that NaHS may protect HUVECs against HG-induced necroptosis by inhibiting the p38 MAPK pathway.

Further experiments were performed to clarify the role of p38 in HG-induced injury in HUVECs. A previous study reported that following the application of a p38 pathway inhibitor, HG-induced oxidative stress was attenuated in cerebral endothelial cells (18). Furthermore, another study also demonstrated that the p38 inhibitor improved HG-induced dysfunction of endothelial cells (56). Similar to these observations, the present results illustrated that HG-induced injury in HUVECs was significantly inhibited following the treatment with SB203580, as evidenced by decreased cytotoxicity, MMP dissipation and ROS generation, as well as the severity of inflammation. These results demonstrated that the inhibition of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway attenuated the injury induced by HG, including cytotoxicity, ROS production, mitochondrial injury and inflammation damage in HUVECs, indicating that the activation of p38 MAPK may be a potential mechanism accounting for HG-induced injury.

In our previous study, it was revealed that NaHS mediated a protective effect in HG-induced apoptosis and necroptosis in HUVECs (29). Consistent with this previous study, the present results suggested that NaHS exerted significant cytoprotection in HUVECs, as evidenced by an increase in cell survival, reduction in ROS production and loss of MMP. In addition, RIP3-siRNA was used to further determine the role of necroptosis pathway in HG-induced injuries in the present study. Notably, both NaHS and RIP3-siRNA effectively suppressed the inflammatory response induced by HG. Our previous study reported the protective effect of NaHS (29), but the specific signaling pathways via which it operates remained unknown. Therefore, the present study was conducted to further investigate the specific mechanism. The results demonstrated that the p38 MAPK signaling pathway was implicated in protection of NaHS. Furthermore, in the present study, a positive feedback loop was identified between necroptosis and the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. The inhibitor of p38 MAPK, SB203580, significantly inhibited the HG-induced expression levels of RIP3. Combined with the aforementioned findings that both p38 MAPK and necroptosis contributed to cell dysfunction, the present study indicated that necroptosis mediated HG-induced injury by activating p38 MAPK. Interestingly, the HG-induced upregulated expression levels of p-p38 were discovered to be diminished by Nec-1 and RIP3-siRNA. This positive feedback may play a crucial role in regulating HG-induced injury and inflammation. For example, the positive feedback of necroptosis and p38 MAPK may trigger the cascade amplification effect, resulting in the aggravation of the inflammatory reaction and tissue injury. Therefore, the present results provide two potential therapeutic targets for diabetic vascular complications.

However, there are some limitations to the present study. Firstly, only in vitro investigations were performed; therefore, further in vivo experiments using model mice, for example, are required to validate the results. Secondly, a constitutively activated p38 activator, such as hesperetin, should be used in further experiments to further strengthen the conclusions.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study elucidated the mechanism underlying the protective effect of NaHS against HG-induced injury and inflammation. The results suggested that NaHS H2S may protect HUVECs against HG-induced injury by inhibiting necroptosis, which may be mediated through the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to identify the positive feedback loop between necroptosis and the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. These findings highlighted the vasculoprotective effects of NaHS and may provide an improved understanding for developing effective therapeutic strategies for diabetic vascular complications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by a grant provided from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81450062).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Experiments were performed by XL and YL. Data collection and analysis were performed by WW. The manuscript was written, drafted and designed by JL, who also performed the experiments. Bioinformatics analysis was performed by ZH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jeffery N, Harries LW. β-cell differentiation status in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/dom.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Rocha Fernandes J, Ogurtsova K, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Seuring T, Zhang P, Cavan D, Makaroff LE. IDF diabetes atlas estimates of 2014 global health expenditures on diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;117:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahajpal NS, Goel RK, Chaubey A, Aurora R, Jain SK. Pathological perturbations in diabetic retinopathy: Hyperglycemia, AGEs, oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2019;20:92–110. doi: 10.2174/1389203719666180928123449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, Wang X, Liu S, Li H, Yuan X, Feng B, Bai H, Zhao B, Chu Y, Li H. Effects and mechanism of miR-23b on glucose-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;70:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laakso M, Kuusisto J. Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in cardiovascular disease development. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Shelat H, Wu H, Zhu M, Xu J, Geng YJ. Low circulating level of IGF-1 is a distinct indicator for the development of cardiovascular disease caused by combined hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171:272–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerra VG, Areti A, Kumar A. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase abates hyperglycaemia-induced neuronal injury in experimental models of diabetic neuropathy: Effects on mitochondrial biogenesis, autophagy and neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:2301–2312. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki K, Olah G, Modis K, Coletta C, Kulp G, Gerö D, Szoleczky P, Chang T, Zhou Z, Wu L, et al. Hydrogen sulfide replacement therapy protects the vascular endothelium in hyperglycemia by preserving mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13829–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceriello A, Novials A, Ortega E, Canivell S, La Sala L, Pujadas G, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Genovese S. Glucagon-like peptide 1 reduces endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress induced by both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2346–2350. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, Wan Y, Zhou S, Lu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang R, Chen F, Hao D, Zhao X, Guo Z, et al. Endothelium-specific SIRT1 overexpression inhibits hyperglycemia-induced upregulation of vascular cell senescence. Sci China Life Sci. 2012;55:467–473. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama M, Shimizu I, Nagasawa A, Yoshida Y, Katsuumi G, Wakasugi T, Hayashi Y, Ikegami R, Suda M, Ota Y, et al. p53 plays a crucial role in endothelial dysfunction associated with hyperglycemia and ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;129:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song W, Wei L, Du Y, Wang Y, Jiang S. Protective effect of ginsenoside metabolite compound K against diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NF-κB/p38 signaling pathway in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;63:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen P, Yuan Y, Zhang T, Xu B, Gao Q, Guan T. Pentosan polysulfate ameliorates apoptosis and inflammation by suppressing activation of the p38 MAPK pathway in high glucose-treated HK-2 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:908–914. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Wang JJ, Li J, Hosoya KI, Ratan R, Townes T, Zhang SX. Activating transcription factor 4 mediates hyperglycaemia-induced endothelial inflammation and retinal vascular leakage through activation of STAT3 in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2533–2545. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2594-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins JM, Joy NG, Tate DB, Davis SN. Acute effects of hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia on vascular inflammatory biomarkers and endothelial function in overweight and obese humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309:E168–E176. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00064.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung UJ, Choi MS. Obesity and its metabolic complications: The role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:6184–6223. doi: 10.3390/ijms15046184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Bao L, Zha D, Zhang L, Gao P, Zhang J, Wu X. Oridonin protects against the inflammatory response in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting the TLR4/p38-MAPK and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;55:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arcambal A, Taïlé J, Rondeau P, Viranaïcken W, Meilhac O, Gonthier MP. Hyperglycemia modulates redox, inflammatory and vasoactive markers through specific signaling pathways in cerebral endothelial cells: Insights on insulin protective action. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;130:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.10.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanmuganathan S, Angayarkanni N. Chebulagic acid chebulinic acid and Gallic acid, the active principles of Triphala, inhibit TNFα induced pro-angiogenic and pro-inflammatory activities in retinal capillary endothelial cells by inhibiting p38, ERK and NFkB phosphorylation. Vascul Pharmacol. 2018;108:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhuriya YK, Sharma D. Necroptosis: A regulated inflammatory mode of cell death. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:199. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhe-Wei S, Li-Sha G, Yue-Chun L. The role of necroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:721. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan FKM, Luz NF, Moriwaki K. Programmed necrosis in the cross talk of cell death and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:79–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He S, Wang L, Miao L, Wang T, Du F, Zhao L, Wang X. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, Chan FKM. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton K, Manning G. Necroptosis and inflammation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85:743–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silke J, Rickard JA, Gerlic M. The diverse role of RIP kinases in necroptosis and inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:689–697. doi: 10.1038/ni.3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negroni A, Colantoni E, Pierdomenico M, Palone F, Costanzo M, Oliva S, Tiberti A, Cucchiara S, Stronati L. RIP3 AND pMLKL promote necroptosis-induced inflammation and alter membrane permeability in intestinal epithelial cells. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Wang T, Li H, Liu Q, Zhang Z, Xie W, Feng Y, Socorburam T, Wu G, Xia Z, Wu Q. Receptor interacting protein 3-mediated necroptosis promotes lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and acute respiratory distress syndrome in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin J, Chen M, Liu D, Guo R, Lin K, Deng H, Zhi X, Zhang W, Feng J, Wu W. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells against high glucoseinduced injury by inhibiting the necroptosis pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:1477–1486. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng T, Chen W, Zhang C, Xiang J, Ding HM, Wu LL, Geng D. The p38/CYLD pathway is involved in necroptosis induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation combined with ZVAD in primary cortical neurons. Neurochem Res. 2017;42:2294–2304. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin S, Yang C, Huang W, Du S, Mai H, Xiao J, Lü T. Sulforaphane attenuates microglia-mediated neuronal necroptosis through down-regulation of MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in LPS-activated BV-2 microglia. Pharmacol Res. 2018;133:218–235. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Zhao M, Chen G, Cheng X, Han X, Lin S, Zhang X, Yu X. The histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat prevents TNFα-induced necroptosis by regulating multiple signaling pathways. Apoptosis. 2013;18:1348–1362. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0866-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Łowicka E, Bełtowski J. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-the third gas of interest for pharmacologists. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gemici B, Elsheikh W, Feitosa KB, Costa SK, Muscara MN, Wallace JL. H2S-releasing drugs: Anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective and chemopreventative potential. Nitric Oxide. 2015;46:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Citi V, Piragine E, Testai L, Breschi MC, Calderone V, Martelli A. The role of hydrogen sulfide and H2S-donors in myocardial protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:4380–4401. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180212120504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu S, Liu Z, Liu P. Targeting hydrogen sulfide as a promising therapeutic strategy for atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar M, Sandhir R. Hydrogen sulfide suppresses homocysteine-induced glial activation and inflammatory response. Nitric Oxide. 2019;90:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Z, Dong X, Zhuang X, Hu X, Wang L, Liao X. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects against high glucose-induced inflammation and cytotoxicity in H9c2 cardiac cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:4911–4917. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Jia YH, Zhao XS, Zhou FH, Pan YY, Wan Q, Cui XB, Sun XG, Chen YY, Zhang Y, Cheng SB. Trichosanatine alleviates oxidized low-density lipoprotein induced endothelial cells injury via inhibiting the LOX-1/p38 MAPK pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:5455–5464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniele G, Guardado Mendoza R, Winnier D, Fiorentino TV, Pengou Z, Cornell J, Andreozzi F, Jenkinson C, Cersosimo E, Federici M, et al. The inflammatory status score including IL-6, TNF-α, osteopontin, fractalkine, MCP-1 and adiponectin underlies whole-body insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00592-013-0543-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith RP, Gosselin RE. Hydrogen sulfide poisoning. J Occup Med. 1979;21:93–97. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chatzianastasiou A, Bibli SI, Andreadou I, Efentakis P, Kaludercic N, Wood ME, Whiteman M, Di Lisa F, Daiber A, Manolopoulos VG, et al. Cardioprotection by H2S donors: Nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:431–440. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.235119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, Ma D, Zheng S, Zha K, Feng J, Cai Y, Jiang F, Li J, Fan Z. The roles of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in the anti-atherosclerotic effect of atorvastatin. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2015;16:22–28. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bełtowski J, Wójcicka G, Jamroz-Wiśniewska A. Hydrogen sulfide in the regulation of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity: Implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of diabetes mellitus. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;149:60–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Zhao X, Jin H, Wei H, Li W, Bu D, Tang X, Ren Y, Tang C, Du J. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the development of atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:173–179. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo R, Wu K, Chen J, Mo L, Hua X, Zheng D, Chen P, Chen G, Xu W, Feng J. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects against doxorubicin-induced inflammation and cytotoxicity by inhibiting p38MAPK/NFκB pathway in H9c2 cardiac cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;32:1668–1680. doi: 10.1159/000356602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang C, Yang Z, Zhang M, Dong Q, Wang X, Lan A, Zeng F, Chen P, Wang C, Feng J. Hydrogen sulfide protects against chemical hypoxia-induced cytotoxicity and inflammation in HaCaT cells through inhibition of ROS/NF-κB/COX-2 pathway. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA, Yuan J. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin J, Li H, Yang M, Ren J, Huang Z, Han F, Huang J, Ma J, Zhang D, Zhang Z, et al. A role of RIP3-mediated macrophage necrosis in atherosclerosis development. Cell Rep. 2013;3:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murakami Y, Matsumoto H, Roh M, Suzuki J, Hisatomi T, Ikeda Y, Miller JW, Vavvas DG. Receptor interacting protein kinase mediates necrotic cone but not rod cell death in a mouse model of inherited degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14598–14603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206937109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luedde M, Lutz M, Carter N, Sosna J, Jacoby C, Vucur M, Gautheron J, Roderburg C, Borg N, Reisinger F, et al. RIP3, a kinase promoting necroptotic cell death, mediates adverse remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:206–216. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao L, Chen X, Xiao X, Ma Q, Li W. Resveratrol inhibits hyperglycemia-driven ROS-induced invasion and migration of pancreatic cancer cells via suppression of the ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:735–743. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu W, Wu W, Chen J, Guo R, Lin J, Liao X, Feng J. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects H9c2 cardiac cells against high glucose-induced injury by inhibiting the activities of the p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 pathways. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:917–925. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perry MM, Tildy B, Papi A, Casolari P, Caramori G, Rempel KL, Halayko AJ, Adcock I, Chung KF. The anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory response of COPD airway smooth muscle cells to hydrogen sulfide. Respir Res. 2018;19:85. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0788-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 55.Koike A, Hanatani M, Fujimori K. Pan-caspase inhibitors induce necroptosis via ROS-mediated activation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein and p38 in classically activated macrophages. Exp Cell Res. 2019;380:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazrouei S, Sharifpanah F, Caldwell RW, Franz M, Shatanawi A, Muessig J, Fritzenwanger M, Schulze PC, Jung C. Regulation of MAP kinase-mediated endothelial dysfunction in hyperglycemia via arginase I and eNOS dysregulation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:1398–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).