Abstract

Antibacterial drug resistance is a global health concern that requires multiple solution approaches including development of new antibacterial compounds acting at novel targets. Targeting regulatory RNA is an emerging area of drug discovery. The T-box riboswitch is a regulatory RNA mechanism that controls gene expression in Gram-positive bacteria and is an exceptional, novel target for antibacterial drug design. We report the design, synthesis and activity of a series of conformationally restricted oxazolidinone-triazole compounds targeting the highly conserved antiterminator RNA element of the T-box riboswitch. Computational binding energies correlated with experimentally-derived Kd values indicating the predictive capabilities for docking studies within this series of compounds. The conformationally restricted compounds specifically inhibited T-box riboswitch function and not overall transcription. Complex disruption, computational docking and RNA binding specificity data indicate that inhibition may result from ligand binding to an allosteric site. These results highlight the importance of both ligand affinity and RNA conformational outcome for targeted RNA drug design.

Keywords: RNA, Drug discovery, T-box riboswitch, Allosteric inhibition, Conformational restriction

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Antibacterial drug resistance continues to grow as a significant global health concern1,2 and creates an urgent need for new antibacterial agents. Riboswitches represent a novel class of potential targets for antibacterial drug discovery.3,4 These noncoding regulatory RNAs structurally respond to levels of metabolite (or ions or other molecular signals) to turn on or off transcription (or translation) of the protein-encoding message.5 The T-box riboswitch is located in the 5′-untranslated region of mRNA, contains multiple highly conserved regions and regulates the expression of many essential genes in Gram-positive bacteria (including known pathogens) by structurally responding to associated tRNA aminoacylation ratios.6-8 These features make it an ideal target for antibacterial drug discovery.

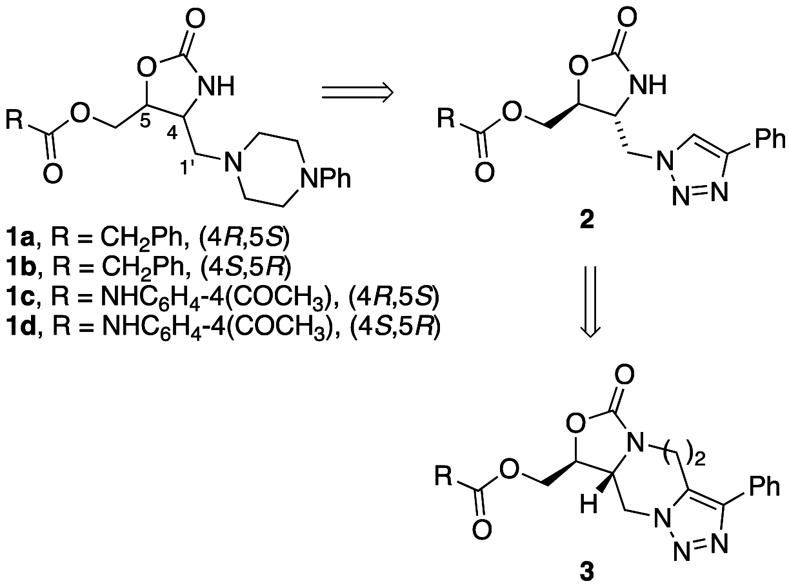

We have been investigating targeting the highly conserved antiterminator RNA element located within the T-box riboswitch in order to develop a new class of antibacterial agents.9-14 Small-molecule inhibitors have recently been identified that bind small pockets in other parts of the T-box riboswitch RNA,8,15,16 but there have been few studies focused on the antiterminator element. One challenge of targeting certain noncoding RNAs observed by our group and others, is achieving binding specificity in what is primarily a surface-binding interaction as evidenced by lack of enantiospecific ligand binding.10,17,18 For example, each enantiomer in the pairs 1a/b and 1c/d (Figure 1) bound T-box antiterminator model RNA with equal affinity by making different contacts along the surface of the target RNA. This was likely due to the conformational flexibility around the C4-C1′ bond in 1 (enabling multiple conformers) and the multiple functional groups presented along the surface of the seven nucleotide bulge in the antiterminator RNA (AM, Figure 2).10 While the challenges of targeting protein surfaces to disrupt protein-protein interactions is an active field of investigation,19 the similar challenges of targeting RNA surfaces (or structural topology) have only recently begun to be explored.20,21 Consequently, we set out to investigate the structural features necessary to provide greater binding specificity to the T-box antiterminator RNA surface and effective modulation of its riboswitch function.

Figure 1.

Design for conformationally restricted compounds

Figure 2.

a) T-box riboswitch antiterminator model RNA, AM. b) Correlation between experimental ΔG = RTln(Kd) and predicted binding energy (Glide-derived Emodel) at pH 6.5. Best fit linear regression indicated by solid line (R2 = 0.8, 95% confidence intervals shown as dashed lines).

Conformational restriction is a classic medicinal chemistry approach to improve drug efficacy.22 While consideration of the role of RNA conformational flexibility has been identified as important for RNA-targeted drug discovery, there has been relatively little focus on ligand conformational flexibility.23,24 Rigidification of flexible ligands can lock in a functional, but nondominant conformer and reduce the entropic loss energy penalty that occurs when a flexible ligand binds a target macromolecule. We designed analogs of 1 to employ this strategy while maintaining an extended ligand to bind along the RNA surface. In an effort to develop more specific surface binding analogs of the previously prepared oxazolidinones (1), triazole derivatives (2) of the phenyl piperazine were investigated and found to provide excellent overlap in a molecular modeling study. In addition, further conformational restriction using a seven-membered ring (3, n = 2) was found to provide an optimal overlap with oxazolidinone derivatives (e.g. 1).25

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis of Conformationally Restricted Ligands

The homochiral analogs of 3 were prepared from enantiopure aziridines 4a and 4b.10 As previously described for the racemic material, the aziridine was treated with TMS-N3 to provide the homochiral azides. Alkylation of the resulting oxazolidinone followed by a thermal dipolar cycloaddition provided 5a and 5b in 10-15% overall yield from 4a and 4b respectively.25 Removal of the trityl ether followed by acylation with phenylacetyl chloride provided triazole 3a, while reaction with 4-acetylphenyl isocyanate provided triazole 3b.

2.2. Docking and Binding Correlation

Compounds were docked computationally to antiterminator model RNA AM (Figure 2) using a previously described method.10 Overall, there was a linear correlation between the computational Emodel value of the predicted lowest energy ligand-RNA complex and the experimentally determined ΔG = RTln(Kd). Compounds 3a-d, which lack an ionizable group, bound with weaker affinity (larger Kd value) than compounds 1a-d, which are predicted to have one protonated amine at the conditions used in the Kd assay (pH 6.5, Figure 2b). In addition, no significant differences in affinity between enantiomeric pairs were observed. Each set of protonated 1 enantiomeric pairs were predicted to bind with similar Emodel values, with the 1c/d enantiomeric pair binding more tightly than the 1a/b pair. These Emodel trends for 1a-d were similar to results obtained from previous docking studies10 and allowed for a direct comparison with the computational docking results of the new compounds 3 . The correlation was comparable to that observed for other ligand-RNA docking studies26 and suggests that, at least within this series of compounds, the docking studies could be useful for in silico screening of analog libraries.

2.3. AM-tRNA Complex Inhibition Without Stabilization

A key component of the T-Box riboswitch mechanism is the base pairing between the tRNA acceptor end nucleotides and the first four nucleotides of the antiterminator.6,7 From a drug discovery standpoint, the goal is to identify ligands that disrupt tRNA binding without stabilizing the antiterminator (which would result in agonist rather than antagonist activity).13 The ligand-induced effect on AM stability was investigated using a previously developed assay27 and no change in RNA thermal stability (Tm) was observed for 3a-d (data not shown). To determine if compounds 3a-d could disrupt formation of the antiterminator-tRNA complex we used a previously developed fluorescence anisotropy assay to monitor binding of tRNA to fluorescently labeled AM.14 Compounds 3c and 3d weakly inhibited the complex formation (−28% and −20% respectively) while 3a/b showed no significant inhibition under the conditions assayed (Figure 3a). In addition, there was little to no selectivity observed between enantiomeric pairs 3a/b or 3c/d.

Figure 3.

a) and b) Ligand effect on formation of tRNA-AM complex as monitored by changes in anisotropy of fluorescently-labeled AM. Average of triplicate data for 3a-d and 1a-d (100 μM). c) and d) Ligand effect on T-box riboswitch transcription readthrough in the presence (filled bars) or absence (open bars) of tRNA induction. Average of triplicate data (100 μM). p values of unpaired t-test are indicated by * (0.01<p<0.05), ** (0.001<p<0.01) and *** (0.0001<p<0.001).

2.4. T-box Riboswitch Inhibition

We investigated the effect of 3a-d on the T-box riboswitch function using a previously developed fluorescently monitored in vitro transcription assay12 with Escherichia coli RNA polymerase Sigma-saturated holoenzyme (NewEngland Biolabs). The compounds inhibited tRNA-induced transcription readthrough with no inhibition of the basal level transcription readthrough (Figure 3b). These results indicate that the negative modulation (inhibition) by 3a-d is specific to the riboswitch function and not overall transcription. Compounds 1a-d inhibited readthrough, but with some inhibition of the basal level transcription for 1c and 1d (Figure 3c). Intriguingly, no significant inhibition was observed for any of the compounds when the enzyme used was one sourced from a different vendor (Epicentre) that produced transcription readthrough product at a faster rate (data not shown). Future investigations will explore this apparent effect of enzyme rate on inhibition and its relationship to the kinetically controlled mechanism28,29 for the T-box riboswitch.

2.5. RNA Binding Specificity

We also investigated potential RNA binding specificity using a previously developed fluorescence-monitored ligand binding assay with AM, a reduced function variant (AMC11U) and a bulge-deletion control RNA (AMΔ).14 This assay monitors ligand-induced RNA structural changes upon binding (e.g., helical changes that affects stacking and therefore fluorescence of the 5′-fluorophore). Potential ligand-RNA specific interactions can then be identified by comparing the ratio of normalized fluorescence changes between model RNAs. The effect of compounds 3a-d (Figure 4a) differed between AM and the control AMΔ (ratio values >1) indicating that the ligands likely bind unique bulge-induced structural features of the antiterminator model RNA. In contrast, 3b-d showed no significant difference between AM and AMC11U (ratio values ~1) and 3a had only a slight difference suggesting that the ligands do not bind near position 11 (located at the 3′ end of the bulge). Interestingly, the docking studies resulted in 3b-d docked in the minor groove of helix H1 extending up to helix H2 and 3a docked in the major groove extending up in to the 5′ end of the bulge (Figure 4b). In contrast, 1a-d and other previously investigated compounds bind in the major groove of helix H1 extending up to the bulge nucleotides that base pair with tRNA, based on computational and experimental results.10,11

Figure 4.

a) Relative fluorescence ratios for 1a-d and 3a-d binding antiterminator model RNAs. b) Lowest energy Glide-docked structure for 3a-d binding to AM.

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of conformationally restricted ligands on binding and specifically disrupting the function of the highly-conserved T-box riboswitch antiterminator element. While 3a-d had weaker binding affinity for AM than 1a-d in the Kd studies (Figure 2b), and modest to no inhibition of the tRNA-antiterminator complex formation (Figure 3a) it is intriguing that 3a-d still effectively inhibited the riboswitch readthrough (Figure 3b). These results indicate that 3a-d, rather than disrupting the tRNA-antiterminator complex via competitive inhibition, may adversely alter the conformation of the complex, thus acting as negative allosteric modulators of T-box riboswitch function. Small molecule-RNA association rates are notably slower than for small molecule-protein binding and likely involve a continuum of ligand-induced RNA conformational changes.30 In addition, transcriptional pause sites have been implicated in the function of the T-box riboswitch31and a kinetic dependence to the sampling of the tRNA acceptor end-antiterminator contacts.28,29 Furthermore, recent crystal structures of the T-box riboswitch that include the antiterminator indicate contacts between antiterminator helix H1 and adjacent sequences in the leader region participate in sensing the tRNA aminoacylation state.32,33 In this context, it is feasible that ligand binding to an allosteric site (a site other than where tRNA directly forms contacts with the antiterminator) could potentially disrupt the function of the T-box riboswitch antiterminator element. The predicted binding of 3b-d in the minor groove of helix H1 (Figure 4b), a location not directly involved with tRNA-base pairing, is consistent with this possible allosteric binding mode that we will investigate further in future studies.

There are examples in the RNA literature of small molecule-induced RNA structure modulation that disrupts an RNA-RNA complex through allosteric binding to a ligand-responsive switch.34 In addition, previous studies with the T-box riboswitch have identified an induced-fit mechanism for formation of the functional tRNA-antiterminator complex35 and positive allosteric modulation of T-box riboswitch function by polyamines that likely act at the tRNA-antiterminator complex.12,36 These findings highlight the potential for allosteric modulation of the T-box riboswitch with small molecules.

Conclusions

Overall, the results indicate that binding T-box riboswitch antiterminator RNA and inhibiting its function requires more than good ligand affinity. Factors such as RNA binding location, induced-fit and/or tertiary structure capture of nonfunctional conformations of the antiterminator may play a role in T-box riboswitch inhibition by small molecules. For some RNA motifs, ligand binding is known to occur via tertiary structure capture of preexisting conformers of a dynamic ensemble26 and this type of allosteric control has been observed in a small molecule riboswitch.37 We are currently investigating the specific binding features and mechanism of riboswitch inhibition for 3a-d in order to investigate their allosteric effect and guide design of future analogs.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. General

All reagents used were purchased from commercial sources or prepared according to standard literature methods using references given in the text and purified as necessary prior to use by standard literature procedures. All reagents and materials for activity assays were sterile, RNase-/DNase-free, molecular biology grade. THF and CH2Cl2 were dried using a Solv-Tek solvent purification system. Dry DMF was distilled from calcium hydride and degassed for 10 min prior to use. Dry toluene was distilled from calcium hydride prior to use. Column chromatography was performed using ICN silica gel 60A. Proton (1H) and carbon (13C) magnetic resonance spectra (NMR) were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 300 MHz spectrometer, and chemical shift values are expressed in parts per million (δ) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS, 0 ppm) as an internal reference. Specific rotations were measured on a AUTOPOL ® IV (Rudolph Research Analytical) polarimeter with a sodium (λ = 589 nm) lamp, and are reported as follows: [α]T °Cλ) (c g/100 mL, solvent). High Performance Liquid Chromatography was conducted on Shimadzu LC-10AT liquid chromatograph equipped with a SPD-10A UV-vis detector with Supelco discovery C8 column (15 cm x 4.6 cm, 5 μm). Method 1: eluting at 1.0 mL min−1 with a gradient elution starting at 50% of CH3CN─H2O for 5 min going to 100% over 15 min. Method 2: eluting at 1.0 mL min−1 with a gradient elution starting at 70% of CH3CN─H2O going to 80% of CH3CN─H2O then going to 100% over 15 min.

4.2. General procedure for aziridine opening

Bicyclic aziridine 4 was dissolved in dry DMF (0.05 M). The solution was cooled to 0 °C, and trimethylsilyl azide (180 mol%) was added dropwise. The reaction was allowed to stir for 24 hours, and then diluted with EtOAc. The solution was washed with water and then brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated. Column chromatography (30:1 CH2Cl2/EtOAc) yielded pure product.

(4R,5S)-4-Azidomethyl-5-(trityloxymethyl)oxazolidin-2-one was prepared from 4a on a 1.3 mmol scale following the general procedure to afford 214 mg (38%) of product. All spectra matched that previously reported.25 [α]D25.1 +57.5 (c 1.1, CH2Cl2).

(4S,5R)-4-Azidomethyl-5-(trityloxymethyl)oxazolidin-2-one was prepared from 4b on a 0.81 mmol scale following the general procedure to afford 226 mg (67%) of product. All spectra matched that previously reported.25 [α]D25.4 −59.5 (c 0.8, CH2Cl2).

4.3. General procedure for N-alkylation

The oxazolidinone was dissolved in THF (0.02 M), and NaH (150 mol%) was added and the solution was stirred at 0 °C for one hour. The reaction was then heated to 60 °C, and but-3-yn-1-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate25 (120 mol%) added and allowed to stir for four hours. The reaction was quenched with saturated aqueous NH4Cl, and washed with brine. The organic layer was concentrated, and purified by column chromatography (20% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide the N-alkylated oxazolidinone.

(4R,5S)-4-(Azidomethyl)-3-(4-phenylbut-3-ynyl)-5-(trityloxymethyl) oxazolidin-2-one was prepared from (4R,5S)-4-Azidomethyl-5-(trityloxymethyl)oxazolidin-2-one on a 0.55 mmol scale following the general procedure to afford 95 mg (32%) of product. All spectra matched that previously reported.25 [α]D23.2 +33.9 (c 1.3, CH2Cl2).

(4S,5R)-4-(Azidomethyl)-3-(4-phenylbut-3-ynyl)-5-(trityloxymethyl) oxazolidin-2-one was prepared from (4S,5R)-4-Azidomethyl-5-(trityloxymethyl)oxazolidin-2-one on a 1.3 mmol scale following the general procedure to afford 92 mg (32%) of product. All spectra matched that previously reported.25 [α]D23.5 −32.4 (c 2.2, CH2Cl2).

4.4. General procedure for triazole formation

The alkynyl azide was refluxed in toluene (0.008 M) for 12 hours. The reaction was concentrated and purified by column chromatography (Gradient: 20%-40% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide the triazole.

(9S, 9aR)-3-Phenyl-9-(trityloxymethyl)-4,5,9a, 10-tetrahydrooxazolo-[3,4-α][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-d][1,4]diazepin-7(9H)-one (5a).

Compound 5a was prepared from the corresponding azide 4a on a 0.3 mmol scale following the general procedure to afford 114 mg (79%) of 5a. All spectra matched that previously reported.25 [α]D21.4 −4.9 (c 1.1, CH2Cl2).

(9R, 9aS)-3-Phenyl-9-(trityloxymethyl)-4,5,9a, 10-tetrahydrooxazolo-[3,4-α][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-d][1,4]diazepin-7(9H)-one (5b).

Compound 5b was prepared from the corresponding azide 4b on a 0.3 mmol scale following the general procedure to afford 99 mg (68%) of 5b. All spectra matched that previously reported.25 [α]D21.8 +5.8 (c 1.6, CH2Cl2).

4.5. General procedure for ester formation

The trityl ether 5 was dissolved in EtOAc (0.14 M) and a solution of HCl in EtOAc (500 mol%, 1.5 M HCl) was added. The mixture was stirred for 10 minutes, and then diluted with 3 volumes of EtOAc and 4 volumes of H2O. The aqueous layer was neutralized with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and then extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated. The crude mixture was dissolved in hexanes, and the solid filtered off. The organic layers were concentrated and used directly in the following acylation reactions. The crude alcohol was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (0.01M). Phenyl acetyl chloride (200 mol%), and Et3N (200 mol%) were added to the reaction mixture and stirred overnight at RT. The reaction mixture was concentrated, and chromatographed to provide the expected ester.

((9S, 9aR)-7-oxo-3-phenyl-4,5,7,9,9a, 10-hexahydrooxazolo[3,4-a][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-d][1,4]diazepin-9-yl)methyl 2-phenylacetate (3a).

Compound (9S,9aR)-3a was prepared from 5a on a 0.16 mmol scale following the general procedure to initially provide the detritylated alcohol (17 mg, (35%); [α]D23.0 −4.6 (c 0.5, MeOH); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.6(m, 2H), 7.5(m, 3H), 5.0(dd, J = 1.5, 14.1 Hz, 1H), 4.6(dd, J = 10.8, 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.4(m, 1H), 4.2(m, 1H), 4.0(m, 1H), 3.8(qd, J = 3.9, 12.3 Hz, 2H), 3.4(m, 1H), 3.0(m, 2H)) which then directly converted to 3a to provide 19 mg (81% from the crude alcohol) of product. [α]D23.4 −10.3 (c 0.5, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.6(m, 2H), 7.5(m, 3H), 7.3(m, 5H), 4.9(dd, J = 1.8, 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.4(m, 4H), 4.1(m, 1H), 3.7(m, 1H), 3.4(dd, J = 3.9, 15.9, 1H), 2.9(dt, J = 2.7, 12.3 Hz, 1H), 2.7 (t, J = 12.3, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.3, 154.2, 144.5, 131.6, 131.4, 128.9, 127.7, 127.5, 127.3, 126.9, 126.4, 125.9, 71.6, 61.6, 55.9, 53.0, 40.9, 39.6, 22.5; HPLC (254 nm, Method 1) 4.67 min., 99%.

((9R, 9aS)-7-oxo-3-phenyl-4,5,7,9,9a, 10-hexahydrooxazolo[3,4-a][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-d][1,4]diazepin-9-yl)methyl 2-phenylacetate (3b).

Compound (9R,9aS)-3b was prepared from 5b on a 0.12 mmol scale following the general procedure to initially provide the detritylated alcohol (17 mg, (42%); [α]D23.2 +5.1 (c 0.6, MeOH); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.5(m, 5H), 5.0(d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 4.5(dd, J = 10.8, 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.4(m, 1H), 4.2(dd, J = 4.5, 10.2, 1H), 4.0(m, 1H), 3.8(qd, J = 3.9, 12.3 Hz, 2H), 3.4(m, 1H), 3.0(m, 2H). which then directly converted to 3b to afford 22 mg (94%) of product. [α]D23.4 +9.5 (c 0.6, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.6(m, 2H), 7.5(m, 3H), 7.3(m, 5H), 4.9(d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 4.3(m, 4H), 4.2(brd, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 3.6(m, 3H), 3.4(dd, J = 3.9, 15.3 Hz, 1H) 2.9 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 2.7 (t, J = 12.3, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.0, 153.9, 144.3, 131.4, 131.1, 128.7, 127.6, 127.4, 127.2, 127.0, 126.8, 126.7, 126.1, 125.6, 125.5, 71.3, 61.4, 55.7, 52.7, 40.6, 39.3 22.3; HPLC (254 nm, Method 1)4.70 min., 97%.

4.6. General procedure for carbamate formation

The trityl ether 5 was dissolved in EtOAc (0.14 M) and a solution of HCl in EtOAc (500 mol%, 1.5 M HCl) was added. The mixture was stirred for 10 minutes, and then diluted with 3 volumes of EtOAc and 4 volumes of H2O. The aqueous layer was neutralized with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and then extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated. The crude mixture was dissolved in hexanes, and the solid filtered off. The organic layers were concentrated and used directly in the subsequent acylation reaction. The crude alcohol was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (0.01M) and cooled to 0 °C. 4-acetylphenyl isocyanate was added (200 mol%) followed by Et3N (200 mol%). The reaction mixture was warmed slowly and stirred overnight at RT. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and purified by column chromatography (70% EtOAc/Hexanes) to provide the pure carbamate.

((9S,9aR)-7-oxo-3-phenyl-4,5,7,9,9a, 10-hexahydrooxazolo[3,4-a][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-d][1,4]diazepin-9-yl)methyl (4-acetylphenyl)carbamate (3c).

Compound (9S,9aR) 3c was prepared from 5a on a 0.06 mmol scale following the general procedure to initially provide the detritylated alcohol (9 mg, (52%) which then directly converted to 3c to afford 12 mg (84%) of product. [α]63323.7 −24.0 (c 0.4, acetone-d6); 1H NMR (300 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 9.3 (s, 1H), 8.0(d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.7(d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 7.5(t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.4(t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.2(d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.7(m, 2H), 4.5(m, 2H), 4.2(m, 1H), 4.1(m, 1H), 3.5(m, 1H), 3.1(q, J = 12, 2H), 2.5(s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 195.9, 156.0, 153.0, 145.0, 143.6, 143.5, 133.9, 132.2, 131.9, 129.7, 129.7, 128.9, 128.0, 127.9, 117.8, 117.7, 73.8, 64.4, 57.2, 54.2, 42.3, 25.8, 24.0; HPLC (254 nm, Method 2) 4.60 min., 98%.

((9R,9aS)-7-oxo-3-phenyl-4,5,7,9,9a, 10-hexahydrooxazolo[3,4-a][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-d][1,4]diazepin-9-yl)methyl (4-acetylphenyl)carbamate (3d).

Compound (9R,9aS)-3d was prepared from 5b on a 0.06 mmol scale following the general procedure to initially provide the detritylated alcohol (11 mg, (67%) which then directly converted to 3d to afford 14 mg (82%) of product. [α]63323.5 +22.1 (c 0.7, acetone); 1H NMR (300 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 9.4 (s, 1H), 8.0(d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.7(d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 7.5(t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.4(t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.2(d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.7(m, 2H), 4.5(m, 2H), 4.2(m, 1H), 4.1(m, 1H), 3.5(m, 1H), 3.1(m, 2H), 2.5(s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 196.5, 156.7, 145.7, 144.1, 134.6, 132.9, 130.4, 129.6, 128.6, 128.5, 118.3, 74.4, 65.0, 57.9, 54.8, 43.0, 26.4, 24.6; HPLC (254 nm, Method 2) 3.69 min., 98%.

4.7. RNA Binding, Specificity & Stability Studies

The Kd values for 3a-d were determined from binding isotherms where ligand-induced changes in fluorescence of 5′-fluorescently labeled AM was monitored and analyzed as previously described.14 Final concentrations used in the assay were 55 mM MOPS, pH 6.5, 0.01 mM EDTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 5% DMSO with 100 nM 5′-TAMRA-AM (Dharmacon) with ligand concentrations ranging from 3.3 to 200 μM, The Kd values for 1a-d were previously reported.10 A similar procedure was followed for the specificity studies with different antiterminator model RNAs14 (AMC11U, AMΔ compared to AM using a final ligand concentration of 100 μM. The normalized change in fluorescence intensity FL/F0 was determined for each model RNA where FL is the fluorescence in the presence of ligand and F0 in the absence of ligand. The relative fluorescence ratios were then calculated from the normalized data and the ratios plotted for AMC11U / AM and AM / AMΔ with error bars indicating standard error propagation from duplicate experiments. RNA thermal stability studies were monitored fluorescently using a previously developed procedure27 with fluorophore-quencher 5′-HEX-AM-3′-DABCYL antiterminator model RNA (Trilink). Each experiment sample consisted of 100 μM ligand, 100 nM HEX-AM-DABCYL in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 0.01 mM EDTA, pH=6.5 and 5% DMSO. The fluorescence was monitored on a AriaMx Real-Time PCR system (Agilent) equipped with the HEX optical cartridge (λex = 535nm λem = 555nm) and the samples heated from 40-90 °C. The Tm (a measure of RNA thermal stability) was obtained from the first derivative of the raw data as previously described.27

4.8. Computational Studies

For the computational docking studies, 1a-d and 3a-d were constructed and minimized in Spartan ‘10 (Wavefunction) using a method previously described,10 then exported to the Small Molecule Drug Discovery Suite-2016 (Schrödinger) where ionization states were calculated (pH 7.0 ± 1) and structures further energy minimized using the LigPrep module with the OPLS 2005 force field. These prepared compounds were then docked using the Glide module with the docking grid set up as previously described.10

4.9. tRNA-AM Complex Inhibition Assay

Ligand-induced disruption of the tRNA-antiterminator complex was investigated using a previously developed fluorescence-anisotropy screening assay.14 Final buffer conditions were 55 mM MOPS, pH 6.5, 0.01 mM EDTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 5% DMSO. The anisotropy negative control reactions (r) contained 100 nM 5′-TAMRA-AM (Dharmacon). The anisotropy positive control reactions (r+) contained 100 nM 5′-TAMRA-AM and 2.5 μM tRNA. These control reactions were done in replicate (n=8 for 3a-d and n=4 for 1a-d). The ligand inhibition reactions (n = 3) contained 100 μM ligand, 100 nM 5′-TAMRA-AM and 2.5 μM tRNA. Data were plotted and analyzed for statistical significance using an unpaired t-test in Prism (Graphpad).

4.10. T-box Riboswitch Inhibition Assay

The effect of compounds on the T-box riboswitch function was investigated using a fluorescently monitored in vitro transcription assay as previously described.12 Final concentrations used in the assay were 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 40 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 5 mM spermidine, 1 mM DTT, 0.23 U/μL Riboguard RNase inhibitor (Epicentre), 2.5% v/v DMSO, 100 nM molecular beacon (sequence-specific fluorescent monitor of transcription read through),12 10 nM DNA template, 0.05 U/μL Escherichia coli RNA polymerase Sigma-saturated holoenzyme (NewEngland Biolabs) and, where indicated, 100 μM ligand, 30 nM tRNA. The extent of transcription readthrough was monitored at 28 °C as Readthroughmax = Fluorescencet=final -Fluorescencet=0min with tfinal = 6 hr, optimized using previously reported optimization procedures.12 Data were plotted and analyzed for statistical significance using an unpaired t-test in Prism (Graphpad).

Scheme 1

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health [grant #1R15GM132841-01], the National Science Foundation MRI grants CHE1338000 and CHE1428787, the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Ohio University and the Baker Award Fund, Ohio University.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Boucher HW; Talbot GH; Bradley JS; Edwards JE; Gilbert D; Rice LB; Scheld M; Spellberg B; Bartlett J "Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE! An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America" Clin. Infect. Dis 2009, 48, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).CDC Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Penchovsky R; Stoilova CC "Riboswitch-based antibacterial drug discovery using high-throughput screening methods" Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2013, 8, 65–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Howe JA; Wang H; Fischmann TO; Balibar CJ; Xiao L; Galgoci AM; Malinverni JC; Mayhood T; Villafania A; Nahvi A; Murgolo N; Barbieri CM; Mann PA; Carr D; Xia E; Zuck P; Riley D; Painter RE; Walker SS; Sherborne B; de Jesus R; Pan WD; Plotkin MA; Wu J; Rindgen D; Cummings J; Garlisi CG; Zhang RM; Sheth PR; Gill CJ; Tang HF; Roemer T "Selective small-molecule inhibition of an RNA structural element" Nature 2015, 526, 672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Smith AM; Fuchs RT; Grundy FJ; Henkin TM "Riboswitch RNAs Regulation of gene expression by direct monitoring of a physiological signal" RNA Biol. 2010, 7, 104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Henkin TM "The T box riboswitch: A novel regulatory RNA that utilizes tRNA as its ligand" Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2014, 1839, 959–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kreuzer KD; Henkin TM "The T-box riboswitch: tRNA as an effector to modulate gene regulation" Microbiol Spectrum 2018, 6, RWR-0028–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Suddala KC; Zhang J "An evolving tale of two interacting RNAs: Themes and variations of the T-box riboswitch mechanism" IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 1167–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Anupam R; Nayek A; Green NJ; Grundy FJ; Henkin TM; Means JA; Bergmeier SC; Hines JV "4,5-disubstituted oxazolidinones: High afffinity molecular effectors of RNA function" Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18, 3541–3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Orac CM; Zhou S; Means JA; Boehme D; Bergmeier SC; Hines JV "Synthesis and stereospecificity of 4,5-disubstituted oxazolidinone ligands binding to T-box riboswitch RNA" J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 6786–6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhou S; Means JA; Acquaah-Harrison G; Bergmeier SC; Hines JV "Characterization of a 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole binding to T box antiterminator RNA" Bioorg. Med. Chem 2012, 20, 1298–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zeng C; Zhou S; Bergmeier SC; Hines JV "Factors that influence T box riboswitch efficacy and tRNA affinity" Bioorg. Med. Chem 2015, 23, 5702–5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Jentzsh F; Hines JV "Interfacing medicinal chemistry with structural bioinformatics: Implications for T box riboswitch RNA drug discovery " BMC Bioinformatics (GLBIO 2011 Special Issue) 2011, 13, S5–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Liu J; Zeng C; Zhou S; Means JA; Hines JV "Fluorescence assays for monitoring RNA-ligand interactions and riboswitch-targeted drug discovery screening" Methods Enzymol. 2015, 550, 363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Stamatopoulou V; Apostolidi M; Li S; Lamprinou K; Papakyriakou A; Zhang J; Stathopoulos C "Direct modulation of T-box riboswitch-controlled transcription by protein synthesis inhibitors" Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 10242–10258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Frohlich KM; Weintraub S; Bell JT; Todd GC; Vare VYP; Schneider R; Kloos ZA; Tabe ES; Cantara WA; Stark C; Onwuanaibe U; Duffy BC; Basant-Sanchez M; Kitchen DB; McDonough K; Agris PF "Discovery of small molecule antibiotics against a unique tRNA-mediated regulation of transcription in Gram-positive bacteria" ChemMedchem 2019, 14, 758–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Litovchick A; Rando RR "Stereospecificity of short Rev-derived peptide interactions with RRE IIB RNA" RNA 2003, 9, 937–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Paulsen RB; Seth PP; Swayze EE; Griffey RH; Skalicky JJ; Cheatham TE; Davis DR "Inhibitor-induced structural change in the HCV IRES domain IIa RNA" Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7263–7268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Smith MC; Gestwicki JE "Features of protein-protein interactions that translate into potent inhibitors: topology, surface area and affinity" Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine 2012, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Eubanks CS; Forte JE; Kapral GJ; Hargrove AE "Small molecule-based pattern recognition to classify RNA structure" J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Charrette BP; Boerneke MA; Hermann T "Ligand optimization by improving shape complementarity at a Hepatitis C virus RNA target" ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 3263–3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Silverman RB The Organic Chemistry of Drug Design and Drug Action; 2nd ed.; Elsevier, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhao F; Zhao Q; Blount KF; Han Q; Tor Y; Hermann T "Molecular recognition of RNA by neomycin and a restricted neomycin derivative" Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 5329–5334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hermann T "Rational ligand design for RNA: the role of static structure and conformational flexibility in target recognition" Biochimie 2002, 84, 869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fang F; Vogel M; Hines JV; Bergmeier SC "Fused ring aziridines as a facile entry into triazole fused tricyclic and bicyclic heterocycles" Org. Biomol. Chem 2012, 10, 3080–3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stelzer AC; Frank AT; Kratz JD; Swanson MD; Gonzalez-Hernandez MJ; Lee J; Andricioaei I; Markovitz DM; Al-Hashimi HM "Discovery of selective bioactive small molecules by targeting an RNA dynamic ensemble" Nature Chem. Biol 2011, 7, 553–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhou S; Acquaah-Harrison G; Jack KD; Bergmeier SC; Hines JV "Ligand-induced changes in T box antiterminator RNA stability" Chem. Biol. Drug Design 2011, 79, 202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Suddala KC; Cabello-Villegas J; Michnicka M; Marshall C; Nikonowicz EP; Walter NG "Hierarchical mechanism of amino acid sensing by the T-box riboswitch" Nature Comms. 2018, 9, Article 1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhang J; Chetnani B; Cormack ED; Alonso D; Liu W; Mondragón A; Fei J "Specific structural elements of the T-box riboswitch drive the two-step binding of the tRNA ligand" eLife 2018, 7, e39518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gleitsmann KR; Sengupta RN; Herschlag D "Slow molecular recognition by RNA" RNA 2017, 23, 1745–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Grundy FJ; Henkin TM "Kinetic analysis of tRNA-directed transcription antitermination of the Bacillus subtilis glyQS gene in vitro" J. Bacteriol 2004, 186, 5392–5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Li S; Sun A; Lehmann J; Stamatopoulou V; Giarimoglou N; Henderson FE; Fan L; Pintilie GD; Zhang K; Chen M; Ludtke SJ; Wang Y-X; Stathopoulos C; Chiu W; Zhang J "Structural basis of amino acid surveillance by higher-order tRNA-mRNA interactions" Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2019, 26, 1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Battaglia RA; Grigg JC; Ke A "Structural basis for tRNA decoding and aminoacylation sensing by T-box riboregulators" Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2019, 26, 1106–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Boerneke MA; Dibrov SM; Gu J; Wyles DL; Hermann T "Functional conservation despite structural divergence in ligand-responsive RNA switches" Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111, 15952–15957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Means JA; Simson CM; Zhou S; Rachford AA; Rack J; Hines JV "Fluorescence probing of T box antiterminator RNA: Insights into riboswitch discernment of the tRNA discriminator base" Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 389, 616–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Liu J; Zeng C; Hogan V; Zhou S; Monwar MM; Hines JV "Identification of spermidine binding site in T-box riboswitch antiterminator RNA" Chem. Biol. Drug Design 2016, 87, 182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Baird NJ; Inglese J; Ferré-D'Amaré AR "Rapid RNA-ligand interaction analysis through high-information content conformational and stability landscapes" Nature Comms. 2015, 6:8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]