Abstract

Pressure ulcer is a health problem worldwide that is common among inpatients and elderly people with physical-motor limitations. To deliver nursing care and prevent the development of pressure ulcers, it is essential to identify the factors that affect it. This global systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted with the aim of evaluating the incidence of pressure ulcers in observational studies. In this study, databases including Web of Science, Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched to collect data. Articles published from 1997 to 2017 about the factors influencing the incidence of pressure ulcers were retrieved and their results were analyzed using meta-analysis according to the Random-Effects Model. The heterogeneity of studies was investigated using the I2 statistic. Data were analyzed using the R and Stata software (version 14). In this study, 35 studies were included in the final analysis. The results showed that the pooled estimate of the incidence rate of pressure ulcer was 12% (95% CI: 10–14). The incidence rates of the pressure ulcers of the first, second, third, and fourth stages were 45% (95% CI: 34–56), 45% (95% CI: 34–56), 4% (95% CI: 3–5), and 4% (95% CI: 2–6), respectively. The highest incidence of pressure ulcers was observed among inpatients in orthopedic surgery ward (18.5%) (95% CI: 11.5–25). According to the final results, better conditions should be provided to decrease the incidence of pressure ulcers in different wards, especially orthopedics, and in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Incidence, meta-analysis, pressure ulcer

Introduction

Pressure Ulcer is a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear.[1] Nowadays, pressure ulcers are the third most costly disease after cancers and cardiovascular diseases. The mortality rates from this disease are 2 to 6 times as much as from other diseases, with 60,000 deaths annually due to this complication.[2] Pressure ulcer occurs more frequently in the tissues of the extremities of the body and in bony extensions such as sacrum and heel in inpatients. The most important risk factors for pressure ulcers are low physical activity, decreased consciousness, urinary and fecal incontinence, malnutrition, and advanced age.[3]

It is estimated that about 2.5 million hospitalizations in the United States are due to pressure ulcers.[4] The pressure ulcers have different classifications one of which has been proposed by the National Council/HSE Wound Conference Oral presentation according to which ulcers are classified into three categories, the most common type of which is the type one with the prevalence rate of approximately 44%. In fact, pressure ulcer is one of the problems that are still underestimated despite advances in medicine. The first step to prevent an increase in the incidence of pressure ulcers is the identification of its risk factors, although there is currently no consensus on its risk factors.[5] Pressure ulcer is a major concern for patients and healthcare staff, and understanding the disease process and prophylactic methods is so important that counseling and prevention systems for it have been developed in the USA and Europe.[6]

The pressure ulcer is associated with pain, patient's reduced autonomy, increased risk of infection and sepsis, the conduction of additional surgical procedures on the patient, long periods of hospital stay, and the imposition of more costs on the patient, his/her family, and health care system.[7,8,9] Patients with pressure ulcers have significant physical-social and self-care dysfunction and may experience certain complications such as depression, pain, topical infection, osteomyelitis, sepsis, and even death.[10,11]

The incidence of pressure ulcer is different in the clinical setting, but its incidence rate ranges from 4% to 38% in hospitalization wards and the mortality rate due to pressure ulcers and its associated secondary complications among the elderly is approximately 68%.[12] A study in an elderly care home in Hapan showed that more than 91% of the total study population had pressure ulcer at various intensities.[5] In the USA, about $11 billion is spent annually by the healthcare system for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. In the UK, 4% of the total treatment costs are allocated for the treatment of pressure ulcers. In addition to the extra costs spent on the treatment of the pressure ulcers, there is bed reservation and associated costs arising from hospitalization. These ulcers also cause the nursing staff an increase in workload by 50%.[6] The assumption that external pressure is the only cause of pressure ulcers has led to ignoring other pathogenic causes of pressure ulcers, which usually lead to failure of the prevention and treatment process. Therefore, identifying the causative agents and preventive measures may lead to implementing more effective interventions.[13] In order to deliver better nursing care and to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers, it is important to study its incidence rate and the factors influencing it in different wards, as well as to identify the factors that cause early diagnosis and prevention of the complication.[14]

Various studies around the world to investigate the incidence of pressure ulcer have had different results. Understanding the current situation is the first step in planning to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcer and control this problem. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to estimate the incidence of each stage of pressure ulcers and highlight the factors involved in its incidence in different wards of a hospital setting.

Materials and Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the incidence of pressure ulcer based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was assessed.[15]

Search strategy

In this study, Web of Science, Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched to collect relevant articles. Relevant articles were retrieved according to a systematic search protocol and using search terms, such as pressure ulcers, decubitus ulcer, pressure injury, pressure sore, bedsore, incidence, and as well as all possible combinations. The main outcome of this study is the reported incidence of pressure ulcer. Accordingly, 111 articles were investigated. Irrelevant and duplicate studies were excluded from the analysis and the articles that were published in non-English languages were also excluded. To access more articles, searches were made as backward (i.e., reviewing the reference lists of eligible articles) and forwards (i.e. reviewing papers that were cited in eligible studies).

The search strategy for the Pabmed database was as follows: (((“pressure ulcer”[MeSH Terms] OR (“pressure”[All Fields] AND “ulcer”[All Fields]) OR “pressure ulcer”[All Fields] OR (“pressure”[All Fields] AND “ulcers”[All Fields]) OR “pressure ulcers”[All Fields]) AND tiab[All Fields]) OR ((”pressure ulcer”[MeSH Terms] OR (“pressure”[All Fields] AND “ulcer”[All Fields]) OR “pressure ulcer”[All Fields] OR (“decubitus”[All Fields] AND “ulcer”[All Fields]) OR “decubitus ulcer”[All Fields]) AND tiab[All Fields]) OR “pressure injury”[All Fields] OR ((”pressure ulcer”[MeSH Terms] OR (“pressure”[All Fields] AND “ulcer”[All Fields]) OR “pressure ulcer”[All Fields] OR (“pressure”[All Fields] AND “sore”[All Fields]) OR “pressure sore”[All Fields]) AND tiab[All Fields]) OR “bed sore”[All Fields]) AND (“epidemiology”[Subheading] OR “epidemiology”[All Fields] OR “incidence”[All Fields] OR “incidence”[MeSH Terms]).

Selection of studies and data extraction

At first, all articles in which the incidence of pressure ulcer was noted among were collected by two independent researchers. The inclusion criteria were: observational studies that reported a pressure ulcer, access to full text of articles, and publication of articles in English. To minimize the risk of bias assessment, searching for articles, selecting studies, evaluating the methodological quality of articles, and extracting data independently were done by two researchers, and any disagreement was resolved by discussion. Exclusion criteria included lack of addressing the risk factors for the incidence of pressure ulcers, being a duplicate, and review articles. A form was used to record the selected information, including the name of the first author, year of publication, geographical location of the study, ward, type of scale, sample size, and the mean age of patients. We assessed the methodological quality of articles based on the ten selected items of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (title and abstract, goals and hypotheses, research environment, inclusion criteria, sample size, statistical methods, descriptive data, interpretation of findings, research limitation, and funding).[16]

Statistical analysis

The variance of each study was calculated using the binomial distribution formula and the weight for each study equals the reciprocal of the variance. We evaluated the heterogeneity between the studies by Q-Cochran test with a significant level less than 0.1 and I2 index. The I2 index of heterogeneity was classified into less than 25% (low heterogeneity), 25% to 75% (moderate heterogeneity), and more than 75% (high heterogeneity).[17] The incidence of pressure ulcers in different wards was investigated by using the subgroup analysis, and the results of the studies were combined using the random-effects meta-analysis. Meta-regression was used to investigate the relationship between the incidence of PU and year of publication and mean age of patients.

The funnel plot based on the Begg's regression test was used to determine the publication bias. Data analysis was performed using the Stata software (version 11.2) and R statistical software.

Results

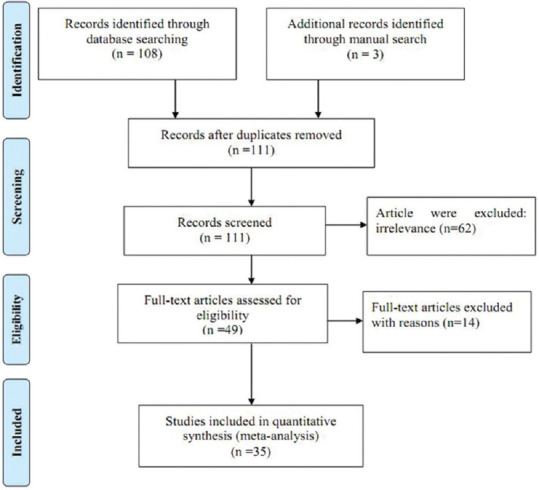

In the present study, 35 articles of adequate quality relevant to the incidence of pressure ulcers and the associated factors in different wards published from 1997 to 2017 were reviewed. The process of selecting and screening articles is presented in the following flowchart [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Screening flowchart showing the selection of qualified articles according to the PRISMA statement

A total of 37,971 patients, of which 53% were males and 47% females, were included in the studies and thus were included in the final analysis. The general information of the articles included in the current review is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

General information of reviewed articles

| Author | Year | Place | Mean age±SD | Sample size | Incidence | Unit | Scale Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox[18] | 2011 | United States | 69±17 | 347 | 18.7 | ICU | Braden |

| Schindler etal.[2] | 2011 | United States | - | 5346 | 10.2 | ICU | Braden |

| Boyle and Green[19] | 2001 | Australia | 57.5 | 534 | 5.2 | ICU | Waterlow |

| Webster etal.[20] | 2010 | Australia | 65.3 | 274 | 4.4 | ICU | Waterlow |

| Gunningberg etal.[21] | 2017 | Sweden | 81±8.5 | 190 | 1.3 | Internal | Norton |

| Dhanda etal.[22] | 2015 | India | - | 228 | 16.39 | Orthopedic | Braden |

| James etal.[12] | 2010 | UK | 80 | 581 | 13.9 | Orthopedic | Braden |

| Mallah etal.[23] | 2015 | United States | 44.69±30.07 | 420 | 6.63 | General | Braden |

| Palese etal.[24] | 2017 | Italy | 82.2 | 1464 | 8.5 | Emergency | Braden |

| Sanada etal.[25] | 2007 | Indonesia | 50.9±17 | 105 | 33.3 | ICU | Braden |

| Sanada etal.[26] | 2008 | Japan | 55.2±18.4 | 253 | 27 | ICU | Suriadi and Sanada |

| Sayar etal.[27] | 2009 | Turkey | 55.7 | 140 | 14.3 | ICU | Waterlow |

| Schoonhoven etal.[28] | 2002 | Netherlands | - | 208 | 21.2 | ICU | Braden |

| Sebastián-Viana etal.[29] | 2016 | Spain | 60.4 | 9220 | 6 | Surgical | modified Norton |

| Shahin etal.[30] | 2009 | Germany | - | 121 | 3.3 | Nephrological ICU | Braden |

| Deng etal.[31] | 2017 | China | 57.81±16.72 | 468 | 20.1 | ICU | Braden |

| Cremasco etal.[32] | 2013 | Brazil | 55.5±18.8 | 160 | 34.4 | ICU | Braden |

| Fujii etal.[33] | 2010 | Japan | 32.5 | 81 | 16 | ICU | Braden |

| GonzálezMéndez etal.[34] | 2017 | Spain | 59.76±14.3 | 335 | 8.1 | ICU | Braden |

| Kaitani etal.[35] | 2010 | Japan | 62.3±16.1 | 98 | 11.2 | ICU | Braden & Bergstrom |

| Lahmann etal.[36] | 2012 | Germany | 66.4±14.7 | 2237 | 14.9 | nephrological ICU | Braden & Bergstrom |

| Ranzani etal.[37] | 2016 | Brazil | - | 9605 | 3.33 | ICU | Charlson |

| Tsaras etal.[38] | 2016 | Greece | 58.9±18.8 | 210 | 2 | ICU | Cubbin and Jackson |

| Nijs etal.[39] | 2009 | Belgium | 64 | 520 | 20.1 | Nephrological ICU | Norton |

| Bååth etal.[40] | 2016 | Sweden | 86.3±7.2 | 183 | 14.6 | ICU | Braden |

| Perneger etal.[41] | 2002 | Switzerland | 61.4±19.1 | 1190 | 14.3 | General | Norton and Braden |

| Becker etal.[42] | 2017 | Brazil | 63.1±18.1 | 332 | 13.6 | ICU | Braden |

| Webster etal.[20] | 2011 | Australia | 62.6±19.3 | 1231 | 6.8 | Internal | Waterlow |

| Baumgarten etal.[43] | 2006 | United States | - | 201 | 6.2 | Emergency | Braden |

| Manzano etal.[44] | 2010 | Spain | 60±17 | 299 | 16 | Surgical | Braden |

| Olson etal.[45] | 1996 | United States | 63±16.6 | 38 | 2.6 | Nephrology | Braden |

| Yatabe etal.[46] | 2013 | Japan | 85±7.6 | 422 | 7.1 | ICU | Braden |

| Maida etal.[47] | 2008 | Canada | 724±13.2 | 415 | 22.4 | Oncology | Braden |

| Hendrichova etal.[48] | 2008 | Italy | 74 | 414 | 6.7 | Oncology | Karnofsky |

| Gunningberg etal.[49] | 2001 | Sweden | 84.4±7.2 | 101 | 29 | Orthopedic | Braden |

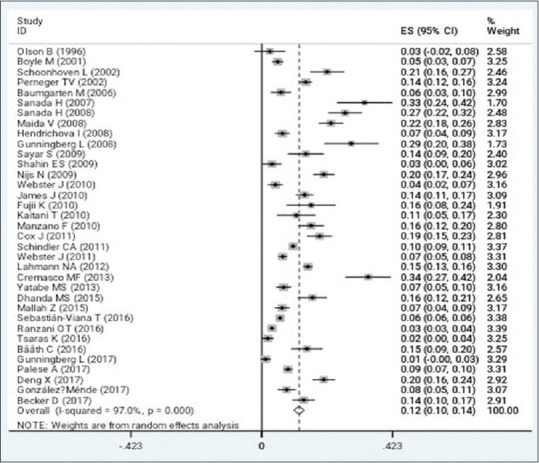

The results of this study showed that the overall incidence of pressure ulcer in different wards across the world is 12% (95% CI: 10–14). In Figure 2, the incidence rates of pressure ulcers in different wards reported by various studies based on the Random-Effects Model are shown.

Figure 2.

The incidence rates of pressure ulcers in the hospital departments based on the Random-Effects Model; the midpoint of every segment indicates the estimate of the incidence; the length of the line represents 95% confidence interval in each study; and the diamond indicates the pooled estimate for incidence rate of pressure ulcers for all studies in the hospital departments from 1997 to 2017 across the world

The incidence rates of the pressure ulcers of the first, second, third, and fourth stages were 45% (95% CI: 34–56), 45% (95% CI: 34–56), 4% (95% CI: 3–5), and 4% (95% CI: 2–6), respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Incidence rates of pressure ulcers of different stages

| Pressure ulcer stage | Incidence rate(95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Stage I | 45(95% CI: 34%-56%) |

| Stage II | 45(95% CI: 34%-56%) |

| Stage III | 4(95% CI: 3%-5%) |

| Stage IV | 4(95% CI: 2%-6%) |

The most commonly affected area was sacrum with a frequency of 44% (95% CI: 28–59), followed by buttocks with a frequency of 15% (95% CI: 10–20), heel with a frequency of 15% (95% CI: 12–18), and trochanter with a frequency of 4% (95% CI: 2–6). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients developing pressure ulcer was 20% (95% CI: 10–31). The highest incidence of pressure ulcers was observed in patients in orthopedics wards (18.5%, 95% CI: 11.5–25) and the least was in nephrology wards (2.6%, 95% CI: 2.5–7.7) [Table 3]. Meta-regression results showed that there is no relationship between the incidence of pressure ulcers and the age of patients and the year of publication (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Incidence rates of pressure ulcers in different hospital departments

| Unit name | Numbers of studies | Pressure ulcer incidence |

|---|---|---|

| ICU | 18 | 13.7%(95% CI: 10.9-16.5) |

| Internal | 2 | 4.1%(95% CI: 1.3-9.5) |

| Orthopedic | 3 | 18.5%(95% CI: 11.5-25) |

| General | 2 | 10.5%(95% CI: 3-18) |

| Surgical | 2 | 10.8%(95% CI: 10-20.6) |

| Nephrological ICU | 3 | 12.8%(95% CI: 4.6-20.9) |

| Nephrology | 1 | 2.6%(95% CI: 2.5-7.7) |

| Emergency Department | 2 | 6.2%(95% CI: 2.9-9.5) |

| Oncology | 2 | 14.5%(95% CI: 9-29.8) |

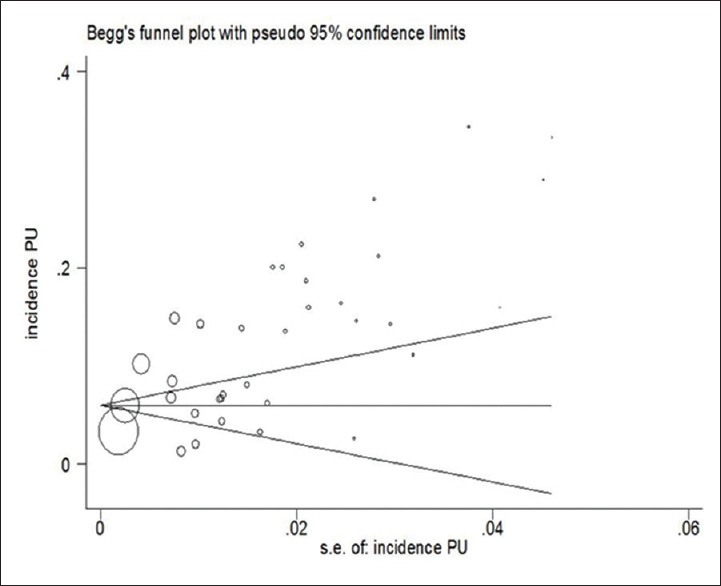

The publication bias was not significant (P = 0.08; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Begg's Funnel plot for evaluation of publication bias

Discussion

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis show that the overall incidence of pressure ulcers in inpatients is 12% worldwide. Most studies in this field have been conducted in European countries. In a study that was conducted in three countries, the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy, including 177 hospitals, 11.1% of inpatients were reported to have pressure ulcer, which is consistent with our findings.[50] Meanwhile, extensive studies in the United States have estimated the frequency of pressure ulcers to be between 8% and 40%.[35] In terms of the stage of ulcers, the results of the present study also indicated that most of the ulcers were of first and second stages, which is in agreement with other studies which have shown that the majority of the samples suffered from first and second stage ulcers.[51] The results of this study showed that the most commonly affected area by pressure ulcer is sacrum, followed by buttocks, heels, and trochanters. Given the fact that the amount of pressure exerted on the ulcer is very effective, studies have shown that, depending on the patient's sleeping position or the use of wheelchairs, pressure ulcers can be developed at certain points, so that in patients laying on the back or sitting on a wheelchair, the possibility of development of ulcers is higher in the hips, sacrum, and heels than in other areas.[14] Regarding diabetes, the data show that the incidence of pressure ulcers in diabetic patients is almost twice as much as that in patients without diabetes mellitus, which indicates a direct correlation between diabetes and incidence of pressure ulcer. The previous studies also confirm this finding so that according to the results of Pokorny et al. (2003), diabetes mellitus, along with certain factors such as obesity and high blood pressure, is among the most common risk factors for incidence of pressure ulcers.[52] The results of Liu et al. (2012) study also show that diabetic patients are five times more likely to develop pressure ulcers than healthy individuals.[53]

In addition, decreased blood flow in these patients is effective in increasing the incidence of pressure ulcers due to the formation of athermanous plaques.[54] Our findings among inpatients in different wards have shown that the highest frequency of pressure ulcers is observed among inpatients in orthopedics wards, followed by those in oncology wards and ICUs, and the least frequency of incidence is observed in nephrology wards. Given that previous studies have shown that lack of movement is one of the main risk factors for the development of pressure ulcers, it seems that patients in the orthopedic wards who are comparatively less able to move are more likely to develop pressure ulcers.[55] In a study conducted on orthopedic patients, the results showed that 16% of patients with hip fractures also developed pressure ulcer.[56] With regards to inpatients in the oncology ward, because the majority of patients admitted to this department are in the final stages of the disease and have clinically inappropriate conditions, they have the most risk factors for pressure ulcer.[48] The use of opioid drugs is higher in hospitalized cancer patients, which can be effective in reducing their movement and increasing the likelihood of developing pressure ulcers.[48] ICU patients are also more likely to develop pressure ulcer due to lack of movement and prolonged hospital stay, so there is a direct correlation between the duration of hospital stay and the incidence of pressure ulcers.[32,36] Other factors contributing to the development of pressure ulcers in ICU patients include dehydration and increased body temperature.[57]

Conclusion

In this study, the least frequency of pressure ulcers was observed among inpatients in nephrology wards. Future studies are recommended to simultaneously address risk factors such as age, weight, and anemia along with the data obtained in this study, and also to closely examine underlying illnesses of people with pressure ulcer to obtain better results. Since pressure ulcers may lead to death, prolongation of treatment, increase in treatment costs and in general, irreparable complications for the patient and the family, the study of their incidence rate, causative factors, and prevention along with efficient training of workforce should be incorporated into the priorities of health care systems across the globe.

Limitations of the study

Lack of access to the full text of some articles and lack of reporting the necessary information in some other articles were the main limitations of this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dorner BD, Posthauer ME, Thomas D. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Role of Nutrition in Pressure Ulcer Healing Clinical Practice Guideline. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schindler CA, Mikhailov TA, Kuhn EM, Christopher J, Conway P, Ridling D, et al. Protecting fragile skin: Nursing interventions to decrease development of pressure ulcers in pediatric intensive care. Am J Crit Care. 2011:26–35. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DM, Snow DE, Rees E, Zischkau AM, Hanson JD, Wolcott RD, et al. Evaluation of the bacterial diversity of pressure ulcers using bTEFAP pyrosequencing. BMC Med Genom. 2010;3:41. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kottner J, Dassen T. Pressure ulcer risk assessment in critical care: Interrater reliability and validity studies of the Braden and Waterlow scales and subjective ratings in two intensive care units. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:671–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnelly J, Winder J, Kernohan W, Stevenson M. An RCT to determine the effect of a heel elevation device in pressure ulcer prevention post-hip fracture. J Wound Care. 2011;20:309–18. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2011.20.7.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:974–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claudia G, Diane M, Daphney SG, Danièle D. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in a university hospital centre: A correlational study examining nurses' knowledge and best practice. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:183–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stinson M, Gillian C, Porter-Armstrong A. A literature review of pressure ulcer prevention: Weight shift activity, cost of pressure care and role of the OT. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller PB, Wille J, van Ramshorst B, van der Werken C. Pressure ulcers in intensive care patients: A review of risks and prevention. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1379–88. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1487-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehghan Shahreza F. From oxidative stress to endothelial cell dysfunction. J Prev Epidemiol. 2016;1:e04. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senmar M, Azimian J, Rafiei H, Habibollahpour M, Yousefi F. The incidence of pressure ulcer in old patients undergoing open heart surgery and the relevant factors. J Prev Epidemiol. 2017;2:e09. [Google Scholar]

- 12.James J, Evans JA, Young T, Clark M. Pressure ulcer prevalence across Welsh orthopaedic units and community hospitals: Surveys based on the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel minimum data set. Int Wound J. 2010;7:147–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas DR. Does pressure cause pressure ulcers? An inquiry into the etiology of pressure ulcers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal K, Chauhan N. Pressure ulcers: Back to the basics. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012;45:244–54. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.101287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Internal Med. 2007;147:573–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox J. Predictors of pressure ulcers in adult critical care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20:364–75. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyle M, Green M. Pressure sores in intensive care: Defining their incidence and associated factors and assessing the utility of two pressure sore risk assessment tools. Aust Crit Care. 2001;14:24–30. doi: 10.1016/s1036-7314(01)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster PJ, Gavin N, Nicholas C, Coleman K, Gardner G. Validity of the Waterlow scale and risk of pressure injury in acute care. Br J Nurs. 2010;19:S14–22. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.Sup2.47246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunningberg L, Sedin IM, Andersson S, Pingel R. Pressure mapping to prevent pressure ulcers in a hospital setting: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;72:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhanda MS, Singh AA, Kumar Y, Surana A, Bhardwaj A, Panesar S. Prevalence and clinical evaluation of Pressure Ulcers using Braden scale from orthopedics wards of a tertiary care teaching hospital. Int Arch Integrated Med. 2015;2:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallah Z, Nassar N, Badr LK. The effectiveness of a pressure ulcer intervention program on the prevalence of hospital acquired pressure ulcers: Controlled before and after study. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palese A, Trevisani B, Guarnier A, Barelli P, Zambiasi P, Allegrini E, et al. Prevalence and incidence density of unavoidable pressure ulcers in elderly patients admitted to medical units. J Tissue Viability. 2017;26:85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtv.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suriadi, Sanada H, Sugama J, Kitagawa A, Thigpen B, Kinosita S, et al. Risk factors in the development of pressure ulcers in an intensive care unit in Pontianak, Indonesia. Int Wound J. 2007;4:208–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suriadi, Sanada H, Sugama J, Thigpen B, Subuh M. Development of a new risk assessment scale for predicting pressure ulcers in an intensive care unit. Nurs Crit Care. 2008;13:34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2007.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayar S, Turgut S, Doǧan H, Ekici A, Yurtsever S, Demirkan F, et al. Incidence of pressure ulcers in intensive care unit patients at risk according to the Waterlow scale and factors influencing the development of pressure ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:765–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoonhoven L, Defloor T, Grypdonck MH. Incidence of pressure ulcers due to surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:479–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sebastián-Viana T, Losa-Iglesias M, González-Ruiz J, Lema-Lorenzo I, Nunez-Crespo F, Fuentes PS. Reduction in the incidence of pressure ulcers upon implementation of a reminder system for health-care providers. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahin ES, Dassen T, Halfens RJ. Incidence, prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in intensive care patients: A longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:413–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng X, Yu T, Hu A. Predicting the risk for hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in critical care patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2017;37:e1–11. doi: 10.4037/ccn2017548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cremasco MF, Wenzel F, Zanei SS, Whitaker IY. Pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit: The relationship between nursing workload, illness severity and pressure ulcer risk. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:2183–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujii K, Sugama J, Okuwa M, Sanada H, Mizokami Y. Incidence and risk factors of pressure ulcers in seven neonatal intensive care units in Japan: A multisite prospective cohort study. Int Wound J. 2010;7:323–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.González-Méndez MI, Lima-Serrano M, Martín-Castaño C, Alonso- Araujo I, Lima-Rodríguez JS. Incidence and risk factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers in an intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:1028–37. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaitani T, Tokunaga K, Matsui N, Sanada H. Risk factors related to the development of pressure ulcers in the critical care setting. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:414–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahmann NA, Kottner J, Dassen T, Tannen A. Higher pressure ulcer risk on intensive care?–Comparison between general wards and intensive care units. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:354–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranzani OT, Simpson ES, Japiassu AM, Noritomi DT. The challenge of predicting pressure ulcers in critically ill patients. A multicenter cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1775–83. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201603-154OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsaras K, Chatzi M, Kleisiaris CF, Fradelos EC, Kourkouta L, Papathanasiou IV. Pressure ulcers: Developing clinical indicators in evidence-based practice. A prospective study. Med Arch. 2016;70:379–83. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2016.70.379-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nijs N, Toppets A, Defloor T, Bernaerts K, Milisen K, Van Den Berghe G. Incidence and risk factors for pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1258–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bååth C, Engström M, Gunningberg L, Athlin ŠM. Prevention of heel pressure ulcers among older patients–from ambulance care to hospital discharge: A multi-centre randomized controlled trial. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perneger TV, Raë A-C, Gaspoz J-M, Borst F, Vitek O, Héliot C. Screening for pressure ulcer risk in an acute care hospital: Development of a brief bedside scale. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:498–504. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker D, Tozo TC, Batista SS, Mattos AL, Silva MCB, Rigon S, et al. Pressure ulcers in ICU patients: Incidence and clinical and epidemiological features: A multicenter study in southern Brazil. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;42:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baumgarten M, Margolis D, Van Doorn C, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hebel JR, Zimmerman S, et al. Black/White differences in pressure ulcer incidence in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1293–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manzano F, Navarro MJ, Roldán D, Moral MA, Leyva I, Guerrero C, et al. Pressure ulcer incidence and risk factors in ventilated intensive care patients. J Crit Care. 2010;25:469–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson B, Langemo D, Burd C, Hanson D, Hunter S, Cathcart-Silberberg T. Pressure ulcer incidence in an acute care setting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 1996;23:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5754(96)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yatabe MS, Taguchi F, Ishida I, Sato A, Kameda T, Ueno S, et al. Mini nutritional assessment as a useful method of predicting the development of pressure ulcers in elderly inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1698–704. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maida V, Corbo M, Dolzhykov M, Ennis M, Irani S, Trozzolo L. Wounds in advanced illness: A prevalence and incidence study based on a prospective case series. Int Wound J. 2008;5:305–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendrichova I, Castelli M, Mastroianni C, Mirabella F, Surdo L, De Marinis M, et al. Pressure ulcers in cancer palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 2010;24:669–73. doi: 10.1177/0269216310376119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjödén PO. Reduced incidence of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures: A 2-year follow-up of quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:399–407. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thoroddsen Á. Pressure sore prevalence: A national survey. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:170–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allman RM, Goode PS, Patrick MM, Burst N, Bartolucci AA. Pressure ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation. JAMA. 1995;273:865–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pokorny ME, Koldjeski D, Swanson M. Skin care intervention for patients having cardiac surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12:535–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu P, He W, Chen HL. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for surgery-related pressure ulcers: A meta-analysis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39:495–9. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e318265222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nasri H. On the occasion of world hypertension day; high blood pressure in geriatric individuals. J Ischemia Tissue Repair. 2017;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Remaley DT, Jaeblon T. Pressure ulcers in orthopaedics. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:568–75. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell KE, Woodbury MG, Houghton PE. Heel pressure ulcers in orthopedic patients: A prospective study of incidence and risk factors in an acute care hospital. Ostomy/Wound Manage. 2010;56:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Panel PU, Alliance PP. Pressure ulcer risk assessment: Do we need a golden hour? J Wound Care. 2015;24:157–63. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2015.24.5.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]