Abstract

Background

The financial burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing due to the ageing population and increased prevalence of comorbid diseases. Our aim was to evaluate age-related differences in health care use and costs in Stage G4/G5 CKD without renal replacement therapy (RRT), dialysis and kidney transplant patients and compare them to the general population.

Methods

Using Dutch health care claims, we identified CKD patients and divided them into three groups: CKD Stage G4/G5 without RRT, dialysis and kidney transplantation. We matched them with two controls per patient. Total health care costs and hospital costs unrelated to CKD treatment are presented in four age categories (19–44, 45–64, 65–74 and ≥75 years).

Results

Overall, health care costs of CKD patients ≥75 years of age were lower than costs of patients 65–74 years of age. In dialysis patients, costs were highest in patients 45–64 years of age. Since costs of controls increased gradually with age, the cost ratio of patients versus controls was highest in young patients (19–44 years). CKD patients were in greater need of additional specialist care than the general population, which was already evident in young patients.

Conclusion

Already at a young age and in the earlier stages of CKD, patients are in need of additional care with corresponding health care costs far exceeding those of the general population. In contrast to the general population, the oldest patients (≥75 years) of all CKD patient groups have lower costs than patients 65–74 years of age, which is largely explained by lower hospital and medication costs.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, costs, dialysis, health claims data, kidney transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including those needing renal replacement therapy (RRT), contribute significantly to health care expenditures [1–5]. The prevalence of CKD is increasing as a result of both population ageing and the increasing prevalence of diseases like hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Therefore the financial burden for society is also likely to increase substantially [6–8].

Important factors affecting the high health care costs of patients with CKD include specific renal treatment costs and the fact that a significant number of patients need additional care for their CKD-related comorbid conditions [9]. Nevertheless, it is largely unknown how many patients need additional care and for which diagnosis this additional care is needed. Since studies have shown that the prevalence of comorbidities in young patients is lower than in the elderly and that the burden of comorbidities in CKD patients increases with age, attention has mainly been drawn to the clinical management of elderly CKD patients. However, the impact of age on health care use and costs of CKD-related comorbidities has rarely been studied [10, 11].

Better knowledge of the age-related differences in health care use and costs leads to a better understanding of the impact of comorbidities on CKD patients in different age categories and will potentially lead to improved, age-specific, clinical management of CKD patients. Furthermore, a comparison with care delivered to individuals of similar age in the general population is needed to gain insights into the extra care provided to CKD patients and the additional costs. Therefore the aim of this study was to assess the age-related differences in health care use and costs of patients with advanced CKD (Stage G4/G5) without RRT, on dialysis and kidney transplant patients and to compare the results with the general population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data

To identify renal patients and to study health care costs, we used Dutch health care claims from 2016. These claims are related to all health care procedures covered by the Health Insurance Act, including the costs of compulsory co-payments [12]. The Vektis database contains health care claims and demographic data from all health insurance companies in the Netherlands. The database covers 99% of all insured residents, and since health care insurance is obligatory in the Netherlands, almost all Dutch residents are insured (99%).

Demographic data include year of birth, sex, postal code and date of death, if applicable. A person’s socio-economic status (SES) was determined by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research and was based on a person’s postal code [13]. The SES score is a reflection of the mean income, the education and the position in the labour market of people living in a postal code area. The mean SES score has been set at 0 and ranges from −6.75 to 3.06; lower scores indicating a lower SES and higher scores indicating a higher SES. To ensure privacy, Vektis pseudonymized the persons’ national identification number and allowed data access only in a secured environment.

Study population

We selected adult patients (i.e. ≥20 years of age) with advanced CKD [Stage G4 with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 and Stage G5 with an eGFR ≤15 mL/min/1.73 m2] with or without RRT using health care claims in the year 2016 and who were alive and insured during the whole year. Patients with incomplete data on year of birth or sex were excluded from the analysis. Patients were divided into four age categories: young (20–44 years), middle-aged (45–64 years), elderly (65–74 years) and ≥75 years of age.

CKD patients were divided into three groups: CKD Stage G4/G5 patients without RRT, CKD patients with dialysis treatment and CKD patients with a kidney transplantation. A detailed list of all diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) used for allocation to groups is provided in Supplementary data, Table S1.

CKD Stage G4/G5

We selected patients with CKD Stage G4/G5 not treated with RRT. In the Netherlands, DRGs are based on health care claims of specialist care delivered in the hospital. Primary care has no comparable disease-specific health care claims. Hence we were unable to identify patients with CKD Stage G4/G5 treated solely in primary care. Patients with health claims for dialysis or kidney transplantation and those who died in the same year were excluded from this group.

Dialysis

We selected CKD patients who were on dialysis treatment in 2016 for the entire year regardless of their dialysis modality. Patients who started dialysis, received a kidney transplant or died in 2016 were excluded. Analyses were performed for the whole dialysis group and separately for haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

Kidney transplantation

We selected CKD patients with a health claim for a new kidney transplantation or for follow-up care after a kidney transplantation during 2016. We excluded transplant patients who started dialysis or died in 2016.

Controls

For every patient in each patient group, we randomly selected two controls, matched for age, sex and SES score (four groups based on quartiles). Controls were randomly selected out of the entire Vektis database, provided they had no health care claim for CKD. In both cases and controls, patients of ≥90 years of age were clustered.

Cost variables

The Vektis data contain DRG claims related to the use of health care resources. As DRG claims are based on negotiated administrative prices for high-level groups of diagnoses, the expenses are an approximation of the real costs. For ease of reference, we will refer to these expenses as ‘costs’. Costs were expressed per calendar year. The total annual costs consisted of all costs reimbursed through health insurance in a year.

Total health care costs encompassed costs of primary care, specialist care delivered in the hospital (inpatient and outpatient), mental health care, prescription medication (excluding medication administered in a hospital and during dialysis treatment, as these are covered by the respective hospital DRGs), transportation and other costs. It should be noted that, in the Netherlands, some prescribed drugs need (co-)payment by the patient. A patient’s costs for drugs not covered by the health care system (including over-the-counter drugs) are not included in the health claims database and are therefore not covered in our study. Hospital costs are based on DRG claims: the reimbursement of a DRG is a negotiated price covering all costs related to the diagnosis and treatment, including, for example, all laboratory assessments and other diagnostics (e.g. chest X-ray, echocardiographs or electrocardiograms).

Hospital costs related to CKD included the costs of all DRG claims for nephrological inpatient and outpatient care, costs of dialysis (including access surgery and maintenance) and the costs of renal transplant care (including the costs for transplant surgery). Moreover, these DRGs encompassed costs for hospital admission related to CKD, medication administered in the hospital and during dialysis treatment, staff costs (such as physician fees) and diagnostic procedures related to CKD.

Hospital costs unrelated to CKD were all other inpatient and outpatient DRG costs. Since DRGs are categorized by medical specialty, we were able to categorize hospital costs into the costs related to consultation of internists, cardiologists, dermatologists and surgeons, as these four medical specialties are of special importance to CKD patients. In the Netherlands, specialist consultation is carried out in a hospital (inpatient or outpatient care) and therefore all specialist care costs were included in this study. Costs were estimated by calculating the average costs of all DRG claims assigned to the specified medical specialties. Within the groups of specialist care, we analysed the most frequently claimed DRG codes per year.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine the characteristics of the patient groups and their matched controls in four age categories. The average annual costs are presented as mean per person with 25th and 75th percentiles. We used percentiles instead of standard deviations, as these better represent the distribution of the data. Cost ratios were calculated by dividing the mean health care costs of patients by the mean costs of matched controls. Moreover, we calculated the percentage of users per group that incurred costs for care in that specific cost category. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

We identified 18 340 patients with CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, 4474 dialysis patients and 9260 patients with a functioning kidney transplant (Table 1). Eight percent of these transplant patients were in the first year of transplantation, leaving 92% of patients who were in later years after a successful transplantation. Of CKD Stage G4/G5 patients not on RRT, 2% were categorized as young, 14% as middle-aged, 26% as elderly and 59% as ≥75 years. In dialysis patients, these were 7, 26, 26 and 41% and in transplant patients 21, 48, 25 and 6%, respectively. In all age groups, more than half of the patients were men. The median SES scores were similar. The matching was successful with respect to age and sex (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients and matched controls by age category

| Age group | CKD Stage G4/G5 |

Dialysis |

Kidney transplantation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Controls | Patients | Controls | Patients | Controls | |

| Age 20–44 years | ||||||

| n (%) | 388 (2) | 776 (2) | 315 (7) | 630 (7) | 1908 (21) | 3816 (21) |

| Age (years), median (25th–75th percentile) | 38 (32–42) | 38 (32–42) | 37 (31–41) | 37 (31–41) | 37 (30–41) | 37 (30–41) |

| Sex (male), % | 54 | 54 | 59 | 59 | 60 | 60 |

| SES score, median (25th–75th percentile) | −0.3 (−1.2–0.4) | −0.2 (−1.1–0.4) | −0.6 (−1.3–0.4) | −0.4 (−1.4–0.4) | −0.2 (−1.2–0.5) | −0.2 (−1.2–0.5) |

| Age 45–64 years | ||||||

| n (%) | 2502 (14) | 5004 (14) | 1163 (26) | 2326 (26) | 4489 (48) | 8978 (48) |

| Age (years), median (25th–75th percentile) | 59 (54–62) | 59 (54–62) | 57 (52–61) | 57 (52–61) | 55 (51–60) | 55 (51–60) |

| Sex (male), % | 52 | 52 | 59 | 59 | 60 | 60 |

| SES score, median (25th–75th percentile) | −0.2 (−1.1–0.5) | −0.2 (−1.1–0.5) | −0.4 (−1.4–0.3) | −0.4 (−1.3–0.3) | −0.1 (−1.0–0.6) | −0.1 (−1.0–0.6) |

| Age 65–75 years | ||||||

| n (%) | 4705 (26) | 9410 (26) | 1166 (26) | 2332 (26) | 2267 (24) | 4534 (24) |

| Age (years), median (25th–75th percentile) | 70 (68–72) | 70 (68–72) | 70 (68–72) | 70 (68–72) | 69 (67–71) | 69 (67–71) |

| Sex (male), % | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 60 |

| SES score, median (25th–75th percentile) | −0.2 (−1.0–0.5) | −0.2 (−1.0–0.5) | −0.4 (−1.3–0.4) | −0.4 (−1.3–0.4) | −0.1 (−1.0–0.6) | −0.1 (−0.9–0.6) |

| Age ≥75 years | ||||||

| n (%) | 10 745 (59) | 21 490 (59) | 1830 (41) | 3660 (41) | 598 (6) | 1196 (6) |

| Age (years), median (25th–75th percentile) | 82 (78–86) | 82 (78–86) | 81 (78–84) | 81 (78–84) | 77 (76–79) | 77 (76–79) |

| Sex (male), % | 53 | 53 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 60 |

| SES score, median (25th–75th percentile) | −0.2 (−1.0–0.4) | −0.2 (−1.0–0.5) | −0.2 (−1.1–0.4) | −0.2 (−1.1–0.4) | −0.1 (−1.0–0.5) | −0.1 (−1.0–0.5) |

Total health care costs

Average annual costs and cost ratios

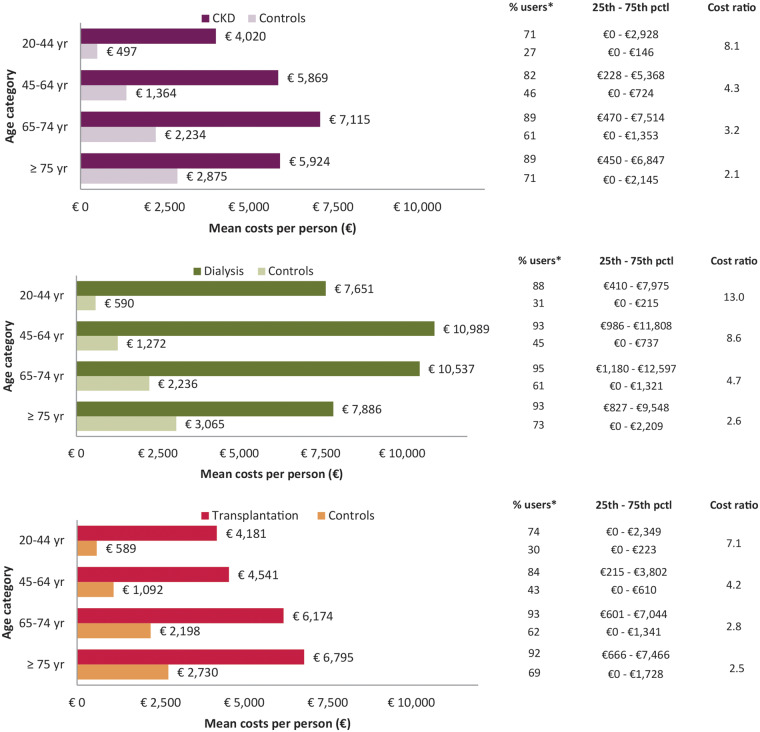

Figure 1 shows average annual costs for all three patient groups per age category and the cost ratios between patients and their controls. Total health care costs of dialysis patients were higher than those of CKD Stage G4/G5 or transplant patients (Figure 1). Overall, the costs of patients ≥75 years of age were lower than the costs of patients 65–74 years of age, the age category with the highest costs. In dialysis patients, costs were highest in the middle-aged patients. Costs for patients on peritoneal dialysis were lower than for haemodialysis patients in all age groups (Supplementary data, Figure S1a).

FIGURE 1.

Total annual health care costs of CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients versus matched controls. *Denotes the percentage of users per group that incurred costs for care in that specific cost category.

Young CKD Stage G4/G5 patients had 7.6 times higher costs than controls, whereas costs were 2.2 times higher in patients ≥75 years of age (Figure 1). Young dialysis patients had 69.1 times higher costs than controls and this cost ratio decreased to 15.9 in the oldest patients. Costs of young transplant patients were 12.4 times higher than controls, decreasing to 3.4 in patients ≥75 years of age.

Costs per segment of health care

Total health care costs can be differentiated in six main segments of health care [i.e. primary care, specialist care delivered in the hospital (inpatient and outpatient), mental health care, prescription medication, transportation and other costs] (Supplementary data, Table S2a–c). Young CKD patients had 9.9 times higher medication costs than controls, which decreased to 2.7 in patients ≥75 years of age. Medication costs of young dialysis patients were 56.2 times higher than those of controls and decreased to 4.9 in patients ≥75 years of age. In transplantation patients, medications costs were 43.0 times higher in young patients and 6.6 times higher in the oldest patients compared with controls.

Hospital costs related to the treatment of CKD

Average annual costs

Approximately 80% of total health care costs of dialysis patients were related to renal treatment, and this was ∼10% for CKD Stage G4/G5 and roughly 20% for transplantation (Supplementary data, Figure S2). Costs for CKD Stage G4/G5 patients ranged from €1045 in patients ≥75 years of age to €1191 in middle-aged patients. In both dialysis and transplant patients, costs were highest in young patients (€70 682 and €5223, respectively) and lowest in patients ≥75 years of age (€66 306 and €3 838, respectively).

Hospital costs unrelated to the treatment of CKD

Average annual costs and cost ratios

Hospital costs unrelated to renal treatment in dialysis patients were higher than those in controls, in particular in middle-aged dialysis patients (€10 989 versus €1272) (Figure 2). At 13.0, the cost ratio was highest in young dialysis patients, declining to 2.6 in patients ≥75 years of age. Costs for peritoneal dialysis patients were lower than costs for haemodialysis patients in all age groups (Supplementary data, Figure S1b). The decrease in cost ratios with age was similar for both dialysis modalities. Also in CKD Stage G4/G5 and transplant patients, these costs were markedly higher than those in controls, and the cost ratios, again, showed that this is especially true at younger age. In CKD Stage G4/G5 patients, cost ratios decreased with age from 8.1 to 2.1, comparable to transplant patients, in whom cost ratios declined from 7.1 to 2.5.

FIGURE 2.

Hospital costs unrelated to treatment of CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients versus hospital costs of matched controls. *Denotes the percentage of users per group that incurred costs for care in that specific cost category.

Percentage health care users

In CKD Stage G4/G5 patients, as well as in transplant recipients, hospital costs unrelated to treatment of CKD were already substantial at a young age (€4020 and €4181, respectively) (Figure 2). More than 70% of these young patients used this care compared with only 30% of young controls. In CKD Stage G4/G5 patients ≥75 years of age, 89% used hospital care unrelated to treatment of CKD and 92% of transplant patients ≥75 years of age used hospital care unrelated to treatment compared with ∼70% of controls. Remarkably, 88% of young dialysis patients needed additional hospital care versus 31% of controls. This increased to 93% in the oldest dialysis patients compared with 73% of controls.

Annual health care costs and health care utilization per medical specialty

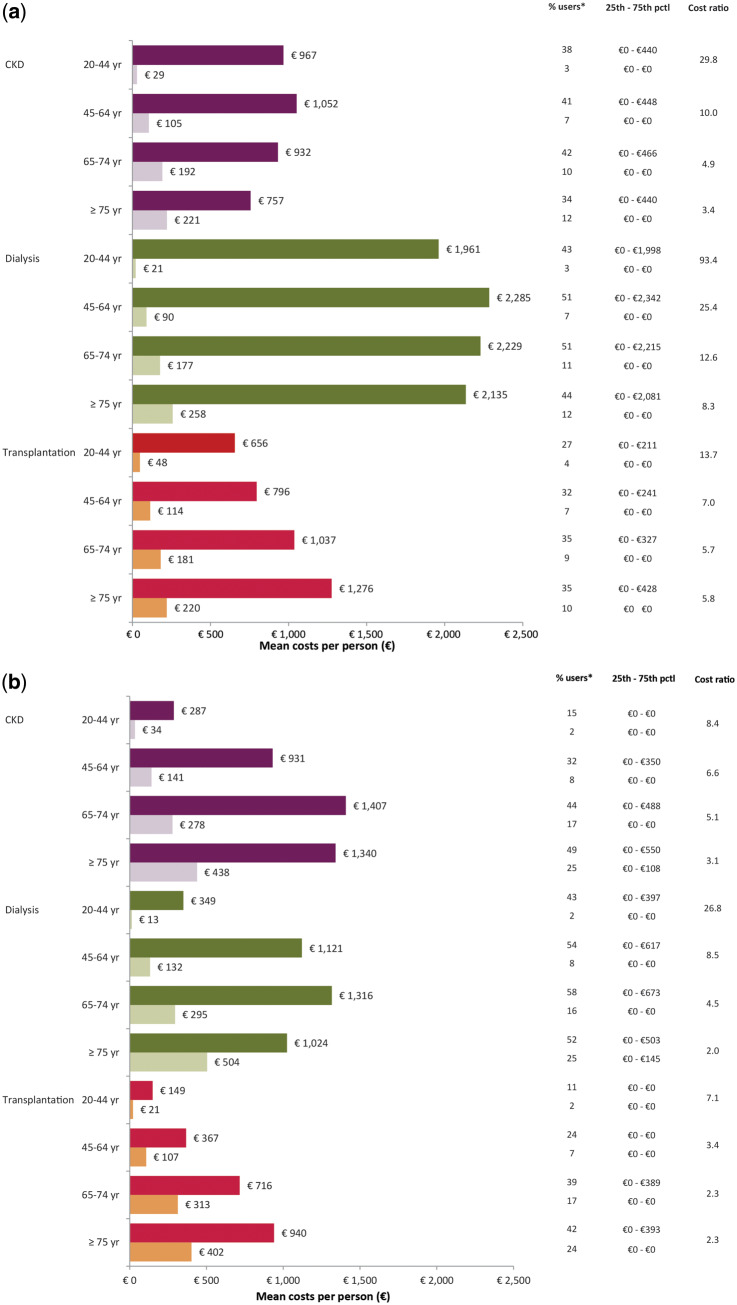

Figures 3a and b and Supplementary data, Figure S3a and b, show that CKD Stage G4/G5, dialysis and kidney transplant patients had 1.5–93.4 times higher costs related to care of internal medicine, cardiologists, dermatologists and surgeons. In all categories, cost ratios were high in young patients and decreased with age.

FIGURE 3.

Annual health care costs of CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients per medical specialty versus matched controls. (a) Internal medicine. (b) Cardiology. *Denotes the percentage of users per group that incurred costs for care in that specific cost category.

Internal medicine

Almost 40% of all CKD Stage G4/G5 patients needed internal medicine care (Figure 3a). In young dialysis patients, 43% received internal medicine care, increasing to ∼50% in elderly patients. In dialysis patients ≥75 years of age, this was 44%. This proportion was 27% in young transplant patients and increased with age. Regardless of age, most resources were spent on care related to diabetes mellitus and infectious diseases (i.e. sepsis/bacteraemia and pneumonia) (Supplementary data, Table S3a). In controls, diabetes mellitus–related care was also the major part of internal medicine care. In addition, the majority of claims in the elderly controls were related to oncology care (breast cancer).

Cardiology

A total of 43% of young dialysis patients needed cardiology care compared with 2% of controls (Figure 3b). This increased to 54 and 58% in middle-aged and elderly patients, respectively, compared with 8 and 16% in controls, respectively. With 15 and 11% use of cardiology care in young CKD Stage G4/G5 and transplantation patients, respectively, this was substantially higher than controls (2%). Almost half of all CKD Stage G4/G5 patients ≥75 years of age visited a cardiologist at least once a year.

Cardiology claims in patients were mostly related to ischaemia-related disorders (i.e. angina pectoris, acute coronary syndrome or follow-up after coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass graft), whereas in controls the majority of cardiology care was assigned to ischaemia-related disorders and cardiac arrhythmia disorders (Supplementary data, Table S3b).

Dermatology

Almost one-quarter of young and more than half of transplant recipients ≥75 years of age used dermatology resources, compared with 4 and 13% of controls, respectively (Supplementary data, Figure S3a). In CKD Stage G4/G5 and dialysis patients, this ranged from 7 to 25%. In all patients, the treatment of malignant and premalignant skin lesions was the most common reason for dermatological care; 38% of elderly transplant patients and 45% of transplant patients ≥75 years of age needed dermatological care for these reasons, compared with only 6 and 10% of controls, respectively.

Surgery

Twenty-nine percent of young dialysis patients and 40% of elderly patients needed surgical care versus 5 and 12% of controls, respectively (Supplementary data, Figure S3b). In the oldest dialysis patients, this was 35%. For both CKD Stage G4/G5 and transplant patients, surgery costs were lower for patients ≥75 years of age than for patients 65–74 years of age.

In general, surgical care was mainly related to vascular disorders like peripheral arterial occlusive disease, ischaemic ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers (Supplementary data, Table S3d). Approximately 8% of elderly dialysis patients needed surgical care for peripheral arterial occlusive disease, more than elderly CKD Stage G4/G5 patients (5%) or elderly transplant patients (3%). Surgical care in controls was related to a wider variety of conditions, such as malignancies (breast cancer), abdominal aortic aneurysm or inguinal or femoral hernia.

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe for the first time the age-related differences in health care costs and health care use in CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients compared with matched controls from the general Dutch population.

As is already known, RRT is expensive; in our study, annual treatment-related costs for CKD patients ranged from €1045 in CKD Stage G4/G5 patients ≥75 years of age to €70 682 in young dialysis patients. However, the additional hospital costs unrelated to CKD treatment ranged from €4020 (young CKD Stage G4/G5 patients) to €10 989 (middle-aged dialysis patients), whereas these hospital costs in the control population ranged from €497 to €3065.

Regarding age differences, in controls, health care costs increased gradually with age. This contrasts with our three patient groups, where costs were often equivalent in different age categories or young and middle-aged patients were more costly than elderly patients. Of note, costs for CKD Stage G4/G5 and dialysis patients ≥75 years of age were lower than for patients 65–74 years of age. We further demonstrated that young patients in particular incur considerably higher costs than controls, which is reflected by the decreasing cost ratios with age. Furthermore, we showed that renal patients were in greater need of additional specialist care because of kidney disease–related comorbidities. Although it is known that the burden of comorbidities is higher in elderly CKD patients, this study shows that costs related to comorbid illness in young patients is similar to that of elderly patients.

Age-related difference of health care costs in CKD patients

We demonstrated that health care costs for renal patients did not differ as much with age as in the general population. Several studies have shown rising health care costs with age in the general population [14–16], whereas studies in CKD and RRT patients have shown no consistent effect of age on health care costs [17–19]. An interesting finding in our study is that the annual health care costs of CKD Stage G4/G5 and dialysis patients ≥75 years of age were lower than for patients 65–74 years of age. This is mainly driven by a decrease in hospital and medication costs with age. An explanation for this observation can possibly be found in the fact that a nephrologist determines for every patient the need for a specific treatment or diagnostic procedure. This thoughtful weighing of harms and benefits may result in different outcomes in the geriatric patient, leading to more conservative treatment options and thus a lowering of total health care expenses.

Our study shows that a comparison of costs within the general population is essential to fully understand the additional costs of kidney patients in different age categories. Only two studies have presented costs of CKD and RRT patients compared with those of matched controls in the general population, and none of these took age into account. One study from the US focusing on patients with CKD Stage G2–G4 found that the total health care costs of patients were twice as high compared with those of matched controls [20]. This study was based on aggregated cost data from 2001. Another paper compared costs of CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients with matched controls using a population-based cohort in Sweden [21]. The study populations in that study are comparable to ours and the described mean annual costs of CKD, dialysis and transplant patients are in line with our results. Although an analysis of different age categories is missing, the cost ratios of the Swedish study are similar to those in middle-aged patients in our study. Extremely high cost ratios in young patients were not described.

Costs and utilization of additional hospital care

In this study we discriminated between treatment-related and non-treatment-related hospital costs. Non-treatment-related hospital costs are a good measure of patients’ comorbidities since they reflect the additional hospital care needed apart from treatment of the kidney disease [19, 22]. It is well-known that patients in different stages of CKD suffer from comorbidities with a significant financial impact [9, 23]. In our study, ∼80% of total hospital costs in CKD Stage G4/G5 patients were unrelated to specific renal treatment. In transplant patients, this varied between 48% and 71% across age categories, whereas in dialysis patients only 10–14% of hospital costs were unrelated to treatment. This effect is far more pronounced in young than in elderly renal patients (all modalities). These results show that the majority of renal patients need substantially more additional hospital care apart from their renal treatment, reflecting a high prevalence of comorbidities already at a young age.

Specialized care for CKD-related comorbidities

Not only the costs of additional specialist care in renal patients are higher than those in controls, also the diagnoses underlying these costs are different. We showed that a significant number of renal patients need cardiology care and this proportion increases with age. We also showed that cardiology resources of renal patients are mainly directed to ischaemia-related diseases, whereas controls from the general population are more often affected with cardiac arrhythmias. Regarding surgery, resources for patients turned out to be predominantly used in care related to vascular disorders, whereas health care use in controls is more often related to malignant diseases. These results confirm that renal patients are frequently affected by cardiovascular complications, which are associated with higher costs [22].

Previous research revealed that CKD patients with diabetes have higher costs [18, 19]. This is in line with our study, which also shows that renal patients have relatively high costs for internal medicine care and most resources were spent on diabetes-related care. In addition, infectious diseases–related care was shown to be frequent in renal patients. In dermatology care, we observed that with age, transplant patients increasingly suffer from malignant and premalignant skin lesions. This is consistent with literature showing that not only elderly patients, but also long-term survivors after kidney transplantation have a higher incidence of skin malignancies associated with the use of immunosuppressive drugs [24].

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is the use of a health care claims database with nationwide coverage. This enabled us to identify all CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients in the Netherlands treated in the hospital with an insurance health claim. The database also provided a unique opportunity to select matched controls from the general population. The comprehensiveness of the cost data allowed for an analysis of health care costs beyond the direct renal treatment costs.

A general limitation of studying costs with the use of health care claims data is that health care expenditures may not reflect the actual costs, since expenditures are actually negotiated prices between health insurance companies and caregivers. Another limitation is the accuracy of the identification of patients with the use of health care claims data. Although identification of patients on RRT was shown to be very accurate [25], the identification of patients with advanced CKD using claims data is subject to underidentification, as we could only select patients actively treated for CKD in a hospital (including outpatient clinics). As a consequence, CKD patients solely treated in primary care could not be identified with claims data. Next, the SES score used for the matching of patients with controls is based on a persons’ postal code and may not reflect the true SES of the individual. Next, by excluding patients who died during the study year and patients starting dialysis treatment, we did not report end-of-life costs and costs related to the start of dialysis treatment. Finally, by including newly transplanted patients during the study year, as health care costs are given per calendar year in this database, this results in an inaccurate estimation of true transplantation procedure costs. However, the costs before transplantation still reflect the costs of a CKD patient preparing for transplantation therapy.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study found that CKD Stage G4/G5 not on RRT, dialysis and kidney transplant patients have notably higher health care costs than the general population. We show for the first time that, already at a young age, additional health care costs of CKD patients are significantly higher than the health care costs of people of the same age in the general population. Additionally, we demonstrate that non-treatment-related hospital costs of CKD Stage G4/G5 patients not on RRT are similar to those of transplant patients in all age groups, although markedly lower than in dialysis patients. This indicates that at young age and in earlier stages of CKD, patients are in need of additional care far exceeding the needs of people in the general population. While total health care costs for the general population continue to increase with age, we observe a decrease in costs in all patient groups ≥75 years of age, which is largely explained by a decrease in hospital and medication costs.

This study provides insight into the specific diagnoses for which patients need additional hospital care. This knowledge of the specific use of hospital resources reveals that the consequences of the comorbidity burden in renal patients are already present at a young age, which supports the importance of age-specific management of CKD patients aimed at prevention and early treatment of comorbid diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Vektis for providing access to the health claims data and for assisting with their comprehensive knowledge regarding analysis of health insurance claims data. The authors thank Nefrovisie, the national quality agency for the treatment of kidney diseases, and RENINE, the Dutch Registry of RRT treatment, for providing registry data for the validation of Vektis data.

FUNDING

This work is financed by a grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vanholder R, Annemans L, Brown E. et al. Reducing the costs of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality health care: a call to action. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017; 13: 393–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Honeycutt AA, Segel JE, Zhuo X. et al. Medical costs of CKD in the Medicare population. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1478–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wyld MLR, Lee CMY, Zhuo X. et al. Cost to government and society of chronic kidney disease stage 1–5: a national cohort study. Intern Med J 2015; 45: 741–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Wit GA, Ramsteijn PG, de Charro FT.. Economic evaluation of end stage renal disease treatment. Health Policy 1998; 44: 215–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vanholder R, Davenport A, Hannedouche T. et al. Reimbursement of dialysis: a comparison of seven countries. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 1291–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klarenbach SW, Tonelli M, Chui B. et al. Economic evaluation of dialysis therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol 2014; 10: 644–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coresh J, Byrd-Holt D, Astor BC. et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among U.S. adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hamer RA, El Nahas AM.. The burden of chronic kidney disease. BMJ 2006; 332: 563–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Damien P, Lanham HJ, Parthasarathy M. et al. Assessing key cost drivers associated with caring for chronic kidney disease patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, James MT. et al. A population-based cohort study defines prognoses in severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 1217–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D. et al. Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18: 2758–2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Boo A. Vektis ‘Informatiecentrum voor de zorg’ [Vektis ‘information center for health care services’]. Tijds Gezondheidswetenschappen 2011; 89: 358–359 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knol F. Van hoog naar laag; van laag naar hoog. Rijswijk: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 1998

- 14. Meerding WJ, Bonneux L, Polder JJ. et al. Demographic and epidemiological determinants of healthcare costs in Netherlands: cost of illness study. BMJ 1998; 317: 111–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polder JJ, Bonneux L, Meerding WJ. et al. Age-specific increases in health care costs. Eur J Public Health 2002; 12: 57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alemayehu B, Warner KE.. The lifetime distribution of health care costs. Health Serv Res 2004; 39: 627–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Icks A, Haastert B, Gandjour A. et al. Costs of dialysis—a regional population-based analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25: 1647–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Couillerot-Peyrondet A-L, Sambuc C, Sainsaulieu Y. et al. A comprehensive approach to assess the costs of renal replacement therapy for end-stage renal disease in France: the importance of age, diabetes status, and clinical events. Eur J Health Econ 2017; 18: 459–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li B, Cairns JA, Fotheringham J. et al. Understanding cost of care for patients on renal replacement therapy: looking beyond fixed tariffs. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1726–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith DH, Gullion CM, Nichols G. et al. Cost of medical care for chronic kidney disease and comorbidity among enrollees in a large HMO population. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 1300–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eriksson JK, Neovius M, Jacobson SH. et al. Healthcare costs in chronic kidney disease and renal replacement therapy: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e012062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kerr M, Bray B, Medcalf J. et al. Estimating the financial cost of chronic kidney disease to the NHS in England. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27 (Suppl 3): iii73–iii80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fraser SDS, Roderick PJ, May CR. et al. The burden of comorbidity in people with chronic kidney disease stage 3: a cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2015; 16: 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ploos van Amstel S, Vogelzang JL, Starink MV. et al. Long-term risk of cancer in survivors of pediatric ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 2198–2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohnen SM, Van Oosten MJM, Los J. et al. Healthcare costs of patients on different renal replacement modalities – analysis of Dutch health insurance claims data. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0220800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.