Abstract

Planctomycetes are ubiquitous bacteria with fascinating cell biological features. Strains available as axenic cultures in most cases have been isolated from aquatic environments and serve as a basis to study planctomycetal cell biology and interactions in further detail. As a contribution to the current collection of axenic cultures, here we characterise three closely related strains, Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33, which were isolated from the Baltic Sea, the Pacific Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, respectively. The strains display cell biological features typical for related Planctomycetes, such as division by polar budding, presence of crateriform structures and formation of rosettes. Optimal growth was observed at temperatures of 30–33 °C and at pH 7.5, which led to maximal growth rates of 0.065–0.079 h−1, corresponding to generation times of 9–11 h. The genomes of the novel isolates have a size of 7.3–7.5 Mb and a G + C content of 57.7–58.2%. Phylogenetic analyses place the strains in the family Pirellulaceae and suggest that Roseimaritima ulvae and Roseimaritima sediminicola are the current closest relatives. Analysis of five different phylogenetic markers, however, supports the delineation of the strains from members of the genus Roseimaritima and other characterised genera in the family. Supported by morphological and physiological differences, we conclude that the strains belong to the novel genus Rosistilla gen. nov. and constitute two novel species, for which we propose the names Rosistilla carotiformis sp. nov. and Rosistilla oblonga sp. nov. (the type species). The two novel species are represented by the type strains Poly24T (= DSM 102938T = VKM B-3434T = LMG 31347T = CECT 9848T) and CA51T (= DSM 104080T = LMG 29702T), respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10482-020-01441-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Planctomycetes, Pirellulaceae, Roseimaritima, Kelp forest, Plastic particles, Algae

Introduction

For a long time since their discovery in 1924, the phylogeny of Planctomycetes was controversial. Initially identified as planktonic microorganisms in a Hungarian freshwater lake, Planctomycetes were primarily misinterpreted as eukaryotes, more specifically as fungi (Gimesi 1924), but later recognised as bacteria (Hirsch 1972). Planctomycetes are of ecological importance and play an important role in the global carbon and nitrogen cycle (Strous et al. 1999; Wiegand et al. 2018). Phylogenetically, the eponymous phylum Planctomycetes is part of the PVC superphylum along with Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae and other sister phyla (Wagner and Horn 2006). Currently, the phylum Planctomycetes is subdivided into the classes Planctomycetia, Phycisphaerae and Candidatus Brocadiae with members of the latter capable of performing anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) (Peeters and van Niftrik 2019). Strains belonging to the classes Plantomycetia and Phycisphaera are typically found in aquatic habitats (Dedysh and Ivanova 2012; Spring et al. 2018), and also in soil environments (Buckley et al. 2006).

Research on Planctomycetes was driven by the observed eukaryotic-like traits (Fuerst and Sagulenko 2011), including apparent absence of a peptidoglycan cell wall (König et al. 1984), a compartmentalised cell plan (Lindsay et al. 1997) and a nucleus-like configuration (Fuerst and Webb 1991). Many of these features have been re-evaluated based on improved microscopic techniques and genetic methods developed for Planctomycetes (Jogler and Jogler 2013; Rivas-Marin et al. 2016). For instance, peptidoglycan has been found in Planctomycetes (Jeske et al. 2015; Van Teeseling et al. 2015). The discovery that members of the sister phylum Verrucomicrobia also possess peptidoglycan (Rast et al. 2017) indicates that all free-living bacteria likely have a peptidoglycan cell wall. Even though anammox Planctomycetes show exceptions (Jogler 2014; Neumann et al. 2014), it has been observed that the suggested cell compartments are actually large invaginations of the cytoplasmic membrane (Acehan et al. 2013; Boedeker et al. 2017; Santarella-Mellwig et al. 2013). Taken together, the cell envelope architecture of Planctomycetes is now regarded as similar to that of Gram-negative bacteria (Devos 2014; Rivas-Marin et al. 2016). Nevertheless, Planctomycetes differ from canonical bacteria, e.g. with regard to the mode of cell division. Members of the class Planctomycetia divide by budding, while binary fission is observed in species of the class Phycisphaerae. Certain species might even be able to switch between both modes (Wiegand et al. 2020). Division thereby does not rely on canonical divisome proteins since many of them are absent from planctomycetal genomes (e.g. ftsZ) (Jogler et al. 2012; Pilhofer et al. 2008).

In the context of the ecological significance of Planctomycetes, several studies showed high abundance of Planctomycetes in biofilms on marine biotic surfaces, such as macroscopic phototrophs (Bengtsson and Øvreås 2010; Bondoso et al. 2014; Bondoso et al. 2017; Lage and Bondoso 2014; Vollmers et al. 2017; Wiegand et al. 2018). This points towards an important function in microbial (biofilm-forming) communities in such environments. A high abundance of Planctomycetes may appear counter-intuitive given that natural competitors in the same ecological niche grow much faster, e.g. Proteobacteria (Frank et al. 2014; Wiegand et al. 2018). In this context, small bioactive molecules secreted by Planctomycetes may take part in mediating symbiotic relationships with algae or serve as antibiotic agents (Graça et al. 2016; Jeske et al. 2016). The capability of Planctomycetes to degrade high molecular weight sugars secreted by primary photosynthetic producers may also provide a decisive growth advantage (Jeske et al. 2013; Lachnit et al. 2013). Pili originating from conspicuous crateriform structures and an enlarged periplasmic space are probably part of an uptake system for entire polysaccharide molecules (Boedeker et al. 2017). Metabolic versatility is further supported by high numbers of carbohydrate-active enzymes encoded in planctomycetal genomes, e.g. polysaccharide lyases or sulfatases (Dabin et al. 2008; Wegner et al. 2013).

During a detailed analysis of genome sequences, it was established that Planctomycetes is amongst the bacterial phyla with the highest numbers of hypothetical proteins (40–55% of the total number of annotated proteins) (Overmann et al. 2017). Consequentially, much interesting cell biology and metabolic potential is expected to be found within this phylum.

As a contribution to the current collection of planctomycetal species, here we characterised three novel strains and analysed their phylogeny as well as basic phenotypic and genotypic characteristics.

Materials and methods

Isolation of the novel strains

The three novel strains were isolated from different locations. Strain Poly24T was sampled on 8 October 2015 from polyethylene particles stored in an incubator, which was placed at 2 m depth in the Baltic Sea below the pier of Heiligendamm, Germany (54.146 N, 11.843 E). Incubation time in the seawater was 14 days. Sterile-filtered natural seawater was added to the polyethylene particles and, after mixing, 50 μL of the seawater were streaked on an M1H NAG ASW plate containing 8 g/L gellan gum, 500 mg/L streptomycin, 200 mg/L ampicillin and 20 mg/L cycloheximide. Strain CA51T was isolated on 28 November 2014 from leaves of a giant bladder kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) on the Californian coastline close to Monterey Bay, CA, USA (36.619 N 121.901 W). Initially, kelp pieces were washed with 100 mg/L cycloheximide dissolved in sterile-filtered natural seawater to prevent fungal growth, then swabbed over M1H NAG ASW plates containing 8 g/L gellan gum, 1000 mg/L streptomycin, 200 mg/L ampicillin and 20 mg/L cycloheximide and incubated at 20 °C for 2 to 3 weeks. Strain Mal33 was sampled on 23 September 2014 from the surface of an alga found on the beach of S’Arenal, Mallorca, Spain (39.5126 N 2.7470 E). Isolation and initial cultivation was performed as described earlier (Wiegand et al. 2020). Single colonies were used to inoculate liquid M1H NAG ASW medium (Boersma et al. 2019). In order to check whether the isolated strains indeed represent members of the phylum Planctomycetes, their 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR and sequenced as previously described (Rast et al. 2017).

Genome information and analysis of genome-encoded features

Genome information of the three isolated strains is available from GenBank under accession numbers CP036348 (Poly24T), CP036292 (CA51T) and CP036318 (Mal33). 16S rRNA gene sequences are available from GenBank under accession numbers MK559990 (Poly24T), MK559969 (CA51T) and MK554528 (Mal33). DNA isolation and genome sequencing were performed as part of a previous study (Wiegand et al. 2020). Enzymes of the primary metabolism were analysed by examining locally computed InterProScan (Mitchell et al. 2019) results cross-referenced with information from the UniProt database and BlastP results of ‘typical’ protein sequences.

Physiological analysis

Determination of the temperature and pH optimum was performed in M1H NAG ASW medium with 100 mM of the following buffers: 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) for pH 5.0 and 6.0, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic (HEPES) for pH 7.0, 7.5 and 8.0, 3-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl)propane-1-sulfonic acid (HEPPS) for pH 8.5 and N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (CHES) for pH 9.0 and 10.0. Cultivations were performed at 28 °C. Cultivations for determination of the temperature optimum were performed at temperatures ranging from 10 to 40 °C in M1H NAG ASW medium at pH 8.0.

Light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy

Microscopic analyses were performed according to a previously published study (Boersma et al. 2019).

Phylogenetic analysis

16S rRNA gene sequence-based phylogeny was computed for strains Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33 and the type strains of all described planctomycetal species (as of May 2020), including recently published strains (Boersma et al. 2019; Dedysh et al. 2020a; Dedysh et al. 2020b; Kallscheuer et al. 2019a; Kallscheuer et al. 2020a; Kallscheuer et al. 2020b; Kallscheuer et al. 2019c; Kallscheuer et al. 2019d; Kohn et al. 2020; Kumar et al. 2020; Peeters et al. 2020; Rensink et al. 2020). An alignment of 16S rRNA gene sequences was made with SINA (Pruesse et al. 2012). By employing a maximum likelihood approach with 1000 bootstraps, nucleotide substitution model GTR, gamma distributed rate variation and estimation of proportion of invariable sites (GTRGAMMAI option), the phylogenetic inference was calculated with RAxML (Stamatakis 2014). Three 16S rRNA genes of strains within the PVC superphylum outside of the phylum Planctomycetes were used as outgroup. For the multi-locus sequence analysis (MLSA), the unique single-copy core genome of the analysed genomes was determined with proteinortho5 (Lechner et al. 2011) with the ‘selfblast’ option enabled. The protein sequences of the resulting orthologous groups were aligned using MUSCLE v.3.8.31 (Edgar 2004). After clipping, partially aligned C- and N-terminal regions and poorly aligned internal regions were filtered using Gblocks (Castresana 2000). The final alignment was concatenated and clustered using the maximum likelihood method implemented by RAxML (Stamatakis 2014) with the ‘rapid bootstrap’ method and 500 bootstrap replicates. OrthoANI was used to calculate the average nucleotide identity (ANI) (Lee et al. 2016), while average amino acid identities (AAI) were calculated using the aai.rb script of the enveomics collection (Rodriguez-R and Konstantinidis 2016). Percentage of conserved proteins (POCP) was calculated as described previously (Qin et al. 2014). The rpoB nucleotide sequences were taken from the above-mentioned genomes as well as other publicly available genome annotations and the sequence identities were determined as described before (Bondoso et al. 2013). The alignment and matrix calculation was performed with Clustal Omega extracting only those parts of the sequence that would have been sequenced with the described primer set (Sievers et al. 2011).

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic inference

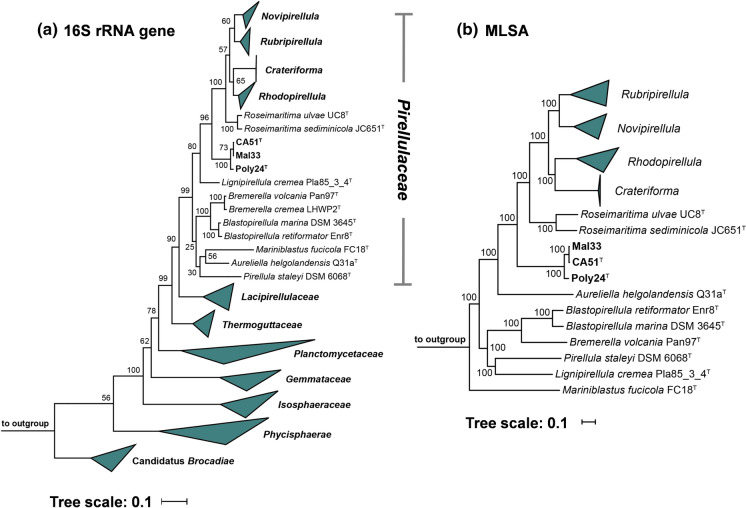

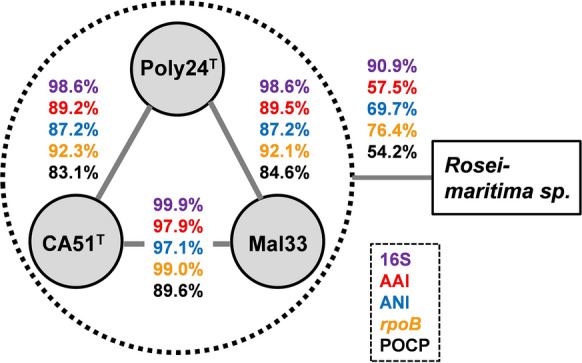

In the phylogenetic trees obtained after analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences and MLSA, the three novel isolates Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33 cluster monophyletically in the family Pirellulaceae (Fig. 1). Analysis of five phylogenetic markers, namely 16S rRNA gene identity, AAI, ANI, rpoB similarity and POCP, suggests Roseimaritima ulvae (Bondoso et al. 2015) and Roseimaritima sediminicola (Kumar et al. 2020) as their current closest neighbours (Fig. 2, Table S1). An ANI of 57.5% far below the species threshold of 95% (Kim et al. 2014) indicates that the strains do not belong to the species R. ulvae or R. sedimimicola. The maximum 16S rRNA gene similarity of the here described strains to members of the genus Roseimaritima was found to be 90.9% (Fig. 2), which is below the proposed genus threshold of 94.5% (Yarza et al. 2014). This finding is in line with values obtained during comparison of the novel isolates with Roseimaritima sp. for AAI and rpoB similarity, which were found to fall below the respective genus thresholds of 60% (Luo et al. 2014) and 75.5–78% (Kallscheuer et al. 2019d) (Fig. 2). Only the POCP of 54.2% is slightly above the suggested genus threshold of 50% (Qin et al. 2014). Taken together, it is reasonable to delineate the strains from the members of the genus Roseimaritima and all other genera of the family Pirellulaceae and to assign them to a novel genus instead.

Fig. 1.

16S rRNA gene sequence- and MLSA-based phylogeny. The phylogenetic trees highlight the position of the three isolated strains. Bootstrap values after 1000 re-samplings are given at the nodes (in %) (500 re-samplings in case of MLSA). The outgroup consists of three 16S rRNA genes from the PVC superphylum (outside of the phylum Planctomycetes). The outgroup in the MLSA tree consists of several members of the family Planctomycetaceae

Fig. 2.

Analysis of phylogenetic markers for delineation of the three novel isolates Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33 from closely related strains belonging to the genus Roseimaritima. Methods used: 16S rRNA gene identity (16S), average amino acid identity (AAI), average nucleotide identity (ANI), identity of a partial rpoB sequence (rpoB) and percentage of conserved proteins (POCP)

In the next step, we compared the strains against each other in order to check for a relationship at the species level. The 16S rRNA genes of strain Mal33 and strain CA51T differ only at a single nucleotide position and thus have a similarity of 99.93%. This value is above the species threshold of 98.7% (Stackebrandt and Ebers 2006), suggesting that both strains are members of the same species. With an AAI of 97.9%, an ANI of 97.1% and an rpoB similarity of 98.9%, the results of the 16S rRNA gene comparison are substantiated when considering the species thresholds of 95% for AAI and ANI and of 96.3% for rpoB (Bondoso et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2014; Luo et al. 2014) (Fig. 2). Using the same phylogenetic markers, we also compared strain Poly24T to the other two strains. In all cases, the obtained values were found to be below the species thresholds, but above the genus thresholds (Fig. 2). Thus, Poly24T constitutes a separate species, but is part of the same genus as CA51T and Mal33.

Morphological and physiological analyses

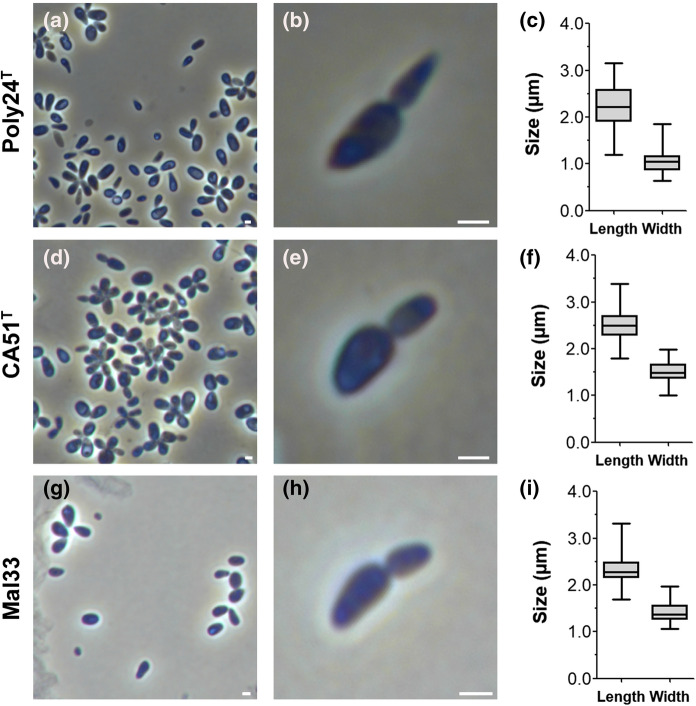

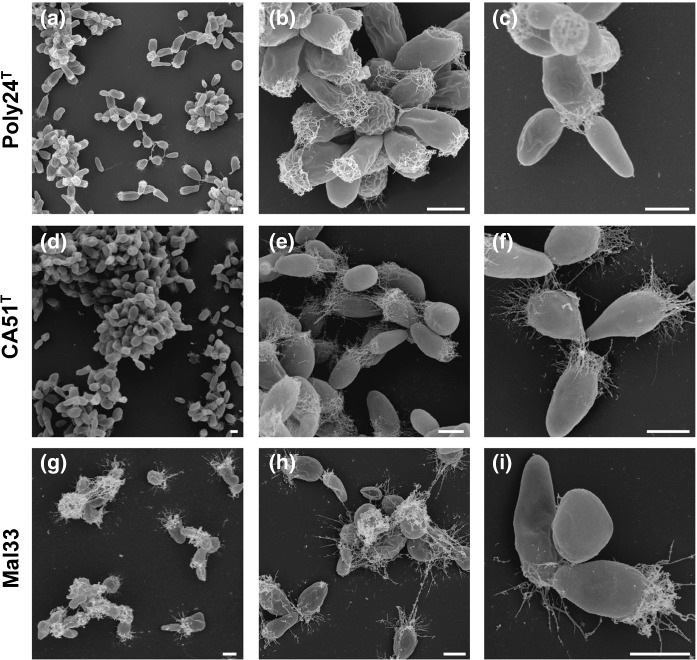

Cell morphology of strains Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33 was analysed using light microscopy (Fig. 3) and scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 4). To be able to investigate the division mode, cells were harvested during the exponential growth phase. Phenotypic features of the three strains are summarised in Table 1 and compared to R. ulvae and R. sediminicola.

Fig. 3.

Light microscopy images and cell size plots of the three isolated strains Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33. A general overview of cell morphology (a, d, g) along with the mode of cell division (b, e, h) is shown in the images. The scale bar is 1 µm. To determine the cell size (c, f, i) at least 100 representatives cells were counted manually or by using a semi-automated object count tool

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopic pictures of the three novel strains Poly24T (a–c), CA51T (d–f) and Mal33 (g–i). The scale bar is 1 µm

Table 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic features of strains Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33 in comparison to closely related strains belonging to the genus Roseimaritima

| Characteristics | Poly24T | CA51T | Mal33 | Roseimaritima ulvae UC8T | Roseimaritima sediminicola JC651T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic features | |||||

| Size (µm) | 2.2 ± 0.4 × 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 × 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3 × 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.1–1.8 × 0.9–1.5 | 1.0–2.0 × 0.8–1.5 |

| Shape | Elongated pear-shaped | Pear-shaped | Pear-shaped | Spherical to ovoid | Round to pear-shaped |

| Colour | Pink | White | Light pink | Light pink | Light pink |

| Temperature range (optimum) (°C) | 10–36 (30) | 10–36 (33) | 10–36 (33) | 15–35 (30) | 15–40 (25) |

| pH range (optimum) | 6.0–9.0 (7.5) | 5.0–9.0 (7.5) | 6.0–8.5 (7.5) | 6.5–10.0 (7.5) | 6.0–9.0 (7.5) |

| Aggregates | Yes, rosettes | Yes, rosettes | Yes, rosettes | Yes, rosettes | Yes, rosettes |

| Division | Budding | Budding | Budding | Budding | Budding |

| Motility | Yes | n.o. | n.o. | Yes | No |

| Crateriform structures | At fibre pole | Polar | Overall | At reproductive pole | At one of the poles |

| Fimbriae | Matrix or fibre, at budding pole | Matrix or fibre, at budding pole | Matrix or fibre, at budding pole | Yes | Yes |

| Bud shape | Pill-shaped | Pill-shaped | Like mother cell | Like mother cell | Like mother cell |

| Stalk | n.o. | n.o. | n.o. | n.o. | n.o. |

| Holdfast structure | Yes, opposite fibre pole | n.o. | n.o. | Yes, opposite fibre pole | n.d. |

| Genomic features | |||||

| Genome size (bp) | 7,437,004 | 7,250,512 | 7,512,089 | 8,212,515 | 6,245,843 |

| Plasmids | No | No | No | No | n.d. |

| G + C content (%) | 57.7 | 58.2 | 58.1 | 59.1 | 62.4 ± 4.0 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.28 | 98.28 | 98.28 | 98.28 | 98.28 |

| Contamination (%) | 3.45 | 1.72 | 3.45 | 1.72 | 1.72 |

| Protein-coding genes | 5515 | 5226 | 5469 | 5919 | 4510 |

| Hypothetical proteins | 2199 | 1983 | 2189 | 2299 | 2816 |

| Protein-coding genes/Mb | 742 | 721 | 728 | 708 | 722 |

| Coding density (%) | 87.2 | 86.6 | 86.6 | 87.5 | 86.5 |

| 16S rRNA genes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| tRNA genes | 47 | 44 | 44 | 71 | 50 |

Genomic analysis for Roseimaritima ulvae UC8T and Roseimaritima sediminicola JC651T is based on GenBank accession numbers CP042914 and GCA_009618275, respectively

n.o. not observed, n.d. not determined

The cells of the novel strains have a similar size and a drop-like shape (Figs. 3, 4). However, strain Poly24T forms more elongated cells and cell poles appeared sharper during light microscopy, a shape which resembles carrots (Fig. 3a, b). The cell shapes significantly differ from the spherical to ovoid-shaped cells of R. ulvae, but are comparable to those of R. sediminicola. The three novel isolates all contain crateriform structures, but their distribution is different (Fig. 4). They cover the entire cell surface of Mal33 cells, but only occur on the pole(s) of the other two strains. All strains contain fimbriae or matrix originating from the budding pole. For strain Poly24T, we observed the presence of flagella and a holdfast structure, while these features were not observed in case of the other two strains. This, however, does not necessarily mean that such structures are not present, as they may have been lost during sample preparation. The observed differences in the pigmentation of the strains were rather unexpected given their close relationship. Strain CA51T is white and thus apparently lacks pigmentation, while strain Mal33 is slightly pink and strain Poly24T shows a more intense pink pigmentation. Both Roseimaritima species show a similar pigmentation to strain Mal33. Since the exact metabolic pathway for carotenoid formation in Planctomycetes is not known (Kallscheuer et al. 2019b), we were not able to draw any conclusions regarding differences in pigmentation from the genome sequences.

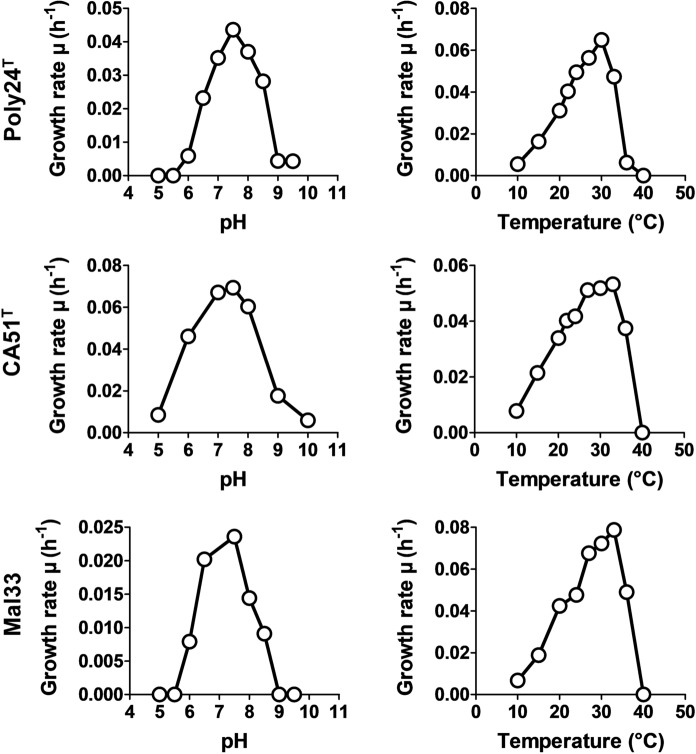

The temperature and pH optima for growth were found to be highly comparable (Fig. 5), including R. ulvae UC8T. All four strains can grow up to temperatures of 35–36 °C with optimal growth at 30–33 °C, and tolerate a pH in the medium of 6.0–9.0. Only strain Mal33 showed a slightly narrower pH range of 6.5–8.5. In all cases, a pH of 7.5 was found to be optimal for the strains. R. sediminicola is able to grow up to temperatures of 40 °C although its temperature optimum is 5–8 °C lower compared to the strains used for comparison (Table 1). Maximal growth rates in M1H NAG ASW medium obtained for the three novel strains were 0.065 h−1 (Poly24T), 0.069 h−1 (CA51T) and 0.079 h−1 (Mal33), which correspond to generation times of 11 h, 10 h and 9 h, respectively. All three strains are aerobic heterotrophs.

Fig. 5.

Temperature and pH optima of the isolates strains Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33. The graphs show the average growth rates obtained from cultivation in M1H NAG ASW medium in biological triplicates. Cultivation was performed as described in the Materials and methods section

Genomic characteristics

The genomes of the novel isolates have a similar size of 7.3–7.5 Mb and are ~ 10% smaller than the genome of R. ulvae (8.2 Mb), but ~ 20% larger than the genome of R. sediminicola (6.3 Mb). The genomes have a G + C content of 58%, which is 1% lower than in R. ulvae and 5% lower compared to R. sediminicola. Given the similar genome size of the novel isolates, the numbers of protein-coding genes (5226–5515) and protein-coding genes per Mb (721–742) were also similar (Table 1). None of the strains (including R. ulvae) harbours plasmids (no information was available for R. sediminicola due to its non-closed genome). All five strains harbour a single 16S rRNA gene and 38–40% of the annotated proteins are of unknown function, except R. sediminicola, for which more than 62% of the annotated proteins are of unknown function. Values for the novel strains are thus in the lower range of up to 55% proteins of unknown function observed in most of the planctomycetal genomes sequenced so far. The number of tRNA genes is 1.7-fold higher in R. ulvae than in the other strains used for comparison (71 vs. 44–50 tRNA genes) (Table 1).

Genome-based analysis of encoded enzymes of the central carbon metabolism

A genome-based analysis was performed for the novel strains in order to gain a first insight into their central carbon metabolism. The analysis included glycolytic pathways (Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, pentose phosphate pathway, Entner-Doudoroff pathway), gluconeogenesis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle including the glyoxylate shunt (Table 2). A detailed description and discussion is not required in case of the three novel isolates since we were able to identify genes coding for all enzymes of the central carbon metabolism as found in typical heterotrophic bacteria. The above-mentioned pathways are thus likely fully functional, except for the glyoxylate shunt, which is absent in all planctomycetal genomes analysed so far.

Table 2.

Genome-based analysis of the central carbon metabolism of isolated strains Poly24T, CA51T and Mal33

| Enzyme | EC | Gene | CA51T | Mal33 | Poly24T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | |||||

| Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 5.3.1.9 | pgi | CA51_28500 | Mal33_48960 | Poly24_26790 |

| ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase isozyme 1 | 2.7.1.11 | pfkA | CA51_07690 | Mal33_07120 | Poly24_11170 |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase class 2 | 4.1.2.13 | fbaA | CA51_27320 | Mal33_50160 | Poly24_20430 |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | 5.3.1.1 | tpiA | CA51_20800 | Mal33_21820 | Poly24_21710 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1.2.1.12 | gapA | CA51_35090 | Mal33_42070 | Poly24_38140 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | 2.7.2.3 | pgk | CA51_19370 | Mal33_20310 | Poly24_22280 |

| 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase | 5.4.2.12 | gpmI | CA51_00820 | Mal33_00850 | Poly24_51780 |

| Enolase | 4.2.1.11 | eno | CA51_02560 | Mal33_02740 | Poly24_02080 |

| Pyruvate kinase I | 2.7.1.40 | pykF | CA51_08860 | Mal33_08330 | Poly24_08360 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component | 1.2.4.1 | aceE | CA51_39170 | Mal33_37970 | Poly24_43390 |

| Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue acetyltransferase component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | 2.3.1.12 | aceF | CA51_39160 | Mal33_37980 | Poly24_28990 |

| Gluconeogenesis | |||||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 4.1.1.31 | ppc | CA51_23330 | Mal33_54740 | Poly24_29970 |

| Pyruvate, phosphate dikinase | 2.7.9.1 | ppdK | CA51_24710 | Mal33_53210 | Poly24_24110 |

| Pyruvate carboxylase | 6.4.1.1 | pyc | CA51_17250 | Mal33_20070 | Poly24_16690 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ATP) | 4.1.1.49 | pckA | CA51_25590 | Mal33_52570 | Poly24_22680 |

| PPi-type phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 4.1.1.38 | PEPCK | CA51_45950 | Mal33_31650 | Poly24_48970 |

| Pyrophosphate–fructose 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase | 2.7.1.90 | pfp | CA51_28740 | Mal33_48680 | Poly24_25860 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | |||||

| Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | 1.1.1.49 | zwf | CA51_17800 | Mal33_17610 | Poly24_16800 |

| 6-Phosphogluconolactonase | 3.1.1.31 | pgl | CA51_26550 | Mal33_49970 | Poly24_29370 |

| CA51_27510 | Mal33_51580 | Poly24_27080 | |||

| CA51_28040 | Mal33_49430 | Poly24_21010 | |||

| 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | 1.1.1.44 | gndA | CA51_27970 | Mal33_49500 | Poly24_21080 |

| Transketolase 2 | 2.2.1.1 | tktB | CA51_32040 | Mal33_45100 | Poly24_33010 |

| Transaldolase B | 2.2.1.2 | talB | CA51_44840 | Mal33_32950 | Poly24_11860 |

| Entner–Doudoroff pathway (KDPG) | |||||

| KHG/KDPG aldolase | 4.1.2.14 | eda | CA51_35880 | Mal33_41360 | Poly24_37690 |

| Phosphogluconate dehydratase | 4.2.1.12 | edd | CA51_17990 | Mal33_18570 | Poly24_12210 |

| TCA cycle | |||||

| Citrate synthase | 2.3.3.16 | gltA | CA51_34870 | Mal33_42290 | Poly24_35470 |

| Aconitate hydratase A | 4.2.1.3 | acnA | CA51_26170 | Mal33_51990 | Poly24_20280 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP] | 1.1.1.42 | icd | CA51_38400 | Mal33_38710 | Poly24_37940 |

| 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | 1.2.4.2 | sucA | CA51_08330 | Mal33_06250 | Poly24_05710 |

| Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | 2.3.1.61 | sucB | CA51_18830 | Mal33_19360 | Poly24_28990 |

| Succinate–CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit alpha | 6.2.1.5 | sucD | CA51_28020 | Mal33_49450 | Poly24_21030 |

| Succinate–CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit beta | 6.2.1.5 | sucC | CA51_28010 | Mal33_49460 | Poly24_21040 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit | 1.3.5.1 | sdhA | CA51_43190 | Mal33_34540 | Poly24_44610 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur subunit | 1.3.5.1 | sdhB | CA51_43180 | Mal33_34550 | Poly24_44620 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b556 subunit | 1.3.5.1 | sdhC | CA51_43200 | Mal33_34530 | Poly24_44600 |

| Fumarate hydratase class II | 4.2.1.2 | fumC | CA51_47870 | Mal33_29690 | Poly24_47530 |

| Malate dehydrogenase | 1.1.1.37 | mdh | CA51_09270 | Mal33_09560 | Poly24_07280 |

| Glyoxylate shunt | |||||

| Isocitrate lyase | 4.1.3.1 | aceA | N | N | N |

| Malate synthase G | 2.3.3.9 | glcB | N | N | N |

Conclusion

Based on the analysis of phenotypic and genomic characteristics and the phylogenetic position of the three novel isolates, it is concluded that the strains represent two novel species within a novel genus in the family Pirellulaceae. Thus, we propose the names Rosistilla oblonga gen. nov., sp. nov., represented by the type strain CA51T, and Rosistilla carotiformis sp. nov., represented by the type strain Poly24T.

Rosistilla gen. nov.

Rosistilla (Ro.si.stil’la. L. fem. n. rosa a rose; L. fem. n. stilla a drop; N.L. fem. n. Rosistilla a rosette-forming bacterium with drop-shaped cells).

Members of the genus have a cell envelope architecture similar to that of Gram-negative bacteria, are aerobic, neutrophilic, mesophilic and heterotrophic. Cells are elongated pear-shaped (drop-like shape), divide by budding and form rosettes. Cells are unpigmented or pink. Crateriform structures are present at the poles or cover the entire cell surface. The genomes have a G + C content of around 58%. The genus is part of the family Pirellulaceae, order Pirellulales, class Planctomycetia, phylum Planctomycetes. The type species of the genus is Rosistilla oblonga.

Rosistilla oblonga sp. nov.

Rosistilla oblonga (ob.lon’ga. L. fem. adj. oblonga oblong; corresponding to the elongated appearance of individual cells).

In addition to the characteristics given in the genus description, cells are pear-shaped and have a cell size of 2.3–2.5 × 1.4–1.5 µm. Colonies either lack pigmentation or are slightly pink. Cells contain fimbriae or matrix at the budding pole and polar crateriform structures. Stalk and holdfast structure may be present. Cells grow at temperatures of 10–36 °C with optimal growth at 33 °C. The pH optimum for growth is 7.5, and growth is observed at pH 5–9. The type strain genome has a size of 7.25 Mb.

The type strain is CA51T (= DSM 104080T = LMG 29702T), which was isolated from a giant bladder kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) in Monterey Bay, CA, USA in November 2014. Strain Mal33 is an additional member of the species.

Rosistilla carotiformis sp. nov.

Rosistilla carotiformis (ca.ro.ti.for’mis. L. fem. n. carota a carrot; L. suff. adj. formis a form, a figure; N.L. fem. adj. carotiformis shaped like a carrot; corresponding to the carrot-shaped morphology of the cells).

In addition to the characteristics given in the genus description, cells form pink colonies. Cells have a size of 2.3 × 1.1 µm and are motile. Cells form fimbriae or matrix on one of the cell poles, on which also crateriform structures are present. A holdfast structure is present at the opposite pole. Cells of the type strain grow at temperatures ranging from 10 to 33 °C (optimum 30 °C) and over a pH range of 6.5 to 8.5 (optimum 7.5). The genome size of the type strain is 7.43 Mb.

The type strain is Poly24T (= DSM 102938T = VKM B-3434T = LMG 31347T = CECT 9848T), which was isolated from polyethylene particles incubated at 2 m depth in the Baltic Sea close to Heiligendamm, Germany in October 2015.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. Part of this research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants KA 4967/1-1 and JO 893/4-1, Grant ALWOP.308 of the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO), Soehngen Institute for Anaerobic Microbiology (SIAM) Grant No. 024002002 and the Radboud Excellence fellowship. We thank Ina Schleicher for skillful technical assistance. Brian Tindall and Regine Fähnrich from the DSMZ as well as the staff from the strain collections in Belgium, Spain and Russia we thank for support during strain deposition. We thank Anne-Kristin Kaster (KIT Karlsruhe, Germany) and Alfred M. Spormann (Stanford, USA) as well as the Aquarius Dive Shop Monterey and the Hopkins Marine Station for sampling support. We also thank our collaborators Sonja Oberbeckmann and Matthias Labrenz (IOW Warnemünde, Germany) for sampling support.

Author contributions

MW and MS wrote the manuscript, NK analysed the data, prepared the figures and revised the manuscript, SW and MJ performed the genomic and phylogenetic analyses, AH and PR isolated the strains and performed the initial cultivation and strain deposition, SHP and CB performed the light microscopic analysis, MSMJ contributed to text preparation and revised the manuscript, MR performed the electron microscopic analysis, CJ took the samples, supervised PR and AH and the study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acehan D, Santarella-Mellwig R, Devos DP. A bacterial tubulovesicular network. J Cell Sci. 2013;127:277–280. doi: 10.1242/jcs.137596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson MM, Øvreås L. Planctomycetes dominate biofilms on surfaces of the kelp Laminaria hyperborea. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedeker C, Schuler M, Reintjes G, Jeske O, van Teeseling MC, Jogler M, Rast P, Borchert D, Devos DP, Kucklick M, Schaffer M, Kolter R, van Niftrik L, Engelmann S, Amann R, Rohde M, Engelhardt H, Jogler C. Determining the bacterial cell biology of Planctomycetes. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14853. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma AS, Kallscheuer N, Wiegand S, Rast P, Peeters SH, Mesman RJ, Heuer A, Boedeker C, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler M, Jogler C. Alienimonas californiensis gen. nov. sp. nov., a novel Planctomycete isolated from the kelp forest in Monterey Bay. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondoso J, Harder J, Lage OM. rpoB gene as a novel molecular marker to infer phylogeny in Planctomycetales. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2013;104:477–488. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9980-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondoso J, Balague V, Gasol JM, Lage OM. Community composition of the Planctomycetes associated with different macroalgae. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;88:445–456. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondoso J, Albuquerque L, Nobre MF, Lobo-da-Cunha A, da Costa MS, Lage OM. Roseimaritima ulvae gen. nov., sp. nov. and Rubripirellula obstinata gen. nov., sp. nov. two novel planctomycetes isolated from the epiphytic community of macroalgae. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015;38:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondoso J, Godoy-Vitorino F, Balague V, Gasol JM, Harder J, Lage OM. Epiphytic Planctomycetes communities associated with three main groups of macroalgae. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2017;93:fiw255. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley DH, Huangyutitham V, Nelson TA, Rumberger A, Thies JE. Diversity of Planctomycetes in soil in relation to soil history and environmental heterogeneity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4522–4531. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00149-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabin J, Jam M, Czjzek M, Michel G. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the polysaccharide lyase RB5312 from the marine planctomycete Rhodopirellula baltica. Acta Cryst Sect F: Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2008;64:224–227. doi: 10.1107/S1744309108004387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedysh SN, Ivanova AO. Abundance, diversity, and depth distribution of Planctomycetes in acidic northern wetlands. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:5. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedysh SN, Henke P, Ivanova AA, Kulichevskaya IS, Philippov DA, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M, Huang S, Overmann J. 100-Year-old enigma solved: identification, genomic characterization and biogeography of the yet uncultured Planctomyces bekefii. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:198–211. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedysh SN, Kulichevskaya IS, Beletsky AV, Ivanova AA, Rijpstra WIC, Damsté JSS, Mardanov AV, Ravin NV. Lacipirellula parvula gen. nov., sp. nov., representing a lineage of planctomycetes widespread in low-oxygen habitats, description of the family Lacipirellulaceae fam. nov. and proposal of the orders Pirellulales ord. nov., Gemmatales ord. nov. and Isosphaerales ord. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2020;43:126050. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2019.126050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos DP. Re-interpretation of the evidence for the PVC cell plan supports a Gram-negative origin. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105:271–274. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0087-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank O, Michael V, Pauker O, Boedeker C, Jogler C, Rohde M, Petersen J. Plasmid curing and the loss of grip—the 65-kb replicon of Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 is required for biofilm formation, motility and the colonization of marine algae. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2014;38:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst JA, Sagulenko E. Beyond the bacterium: planctomycetes challenge our concepts of microbial structure and function. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:403–413. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst JA, Webb RI. Membrane-bounded nucleoid in the eubacterium Gemmata obscuriglobus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8184–8188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimesi N (1924) Hydrobiologiai Tanulmanyok (Hydrobiologische Studien). I: Planctomyces bekefii Gim. nov. gen. et sp. [in Hungarian, with German translation]. Kiadja a Magyar Ciszterci Rend. Budapest, Hungary, pp 1–8

- Graça AP, Calisto R, Lage OM. Planctomycetes as novel source of bioactive molecules. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1241. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch P. Two identical genera of budding and stalked bacteria: Planctomyces Gimesi 1924 and Blastocaulis Henrici and Johnson 1935. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1972;22:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jeske O, Jogler M, Petersen J, Sikorski J, Jogler C. From genome mining to phenotypic microarrays: Planctomycetes as source for novel bioactive molecules. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2013;104:551–567. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske O, Schuler M, Schumann P, Schneider A, Boedeker C, Jogler M, Bollschweiler D, Rohde M, Mayer C, Engelhardt H, Spring S, Jogler C. Planctomycetes do possess a peptidoglycan cell wall. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7116. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske O, Surup F, Ketteniß M, Rast P, Förster B, Jogler M, Wink J, Jogler C. Developing techniques for the utilization of Planctomycetes as producers of bioactive molecules. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1242. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogler C. The bacterial ‘mitochondrium’. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:751–755. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogler M, Jogler C. Towards the development of genetic tools for Planctomycetes. In: Fuerst JA, editor. Planctomycetes: cell structure, origins and biology. Berlin: Springer; 2013. pp. 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jogler C, Waldmann J, Huang X, Jogler M, Glöckner FO, Mascher T, Kolter R. Identification of proteins likely to be involved in morphogenesis, cell division, and signal transduction in Planctomycetes by comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:6419–6430. doi: 10.1128/JB.01325-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallscheuer N, Jogler M, Wiegand S, Peeters SH, Heuer A, Boedeker C, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler C. Rubinisphaera italica sp. nov. isolated from a hydrothermal area in the Tyrrhenian Sea close to the volcanic island Panarea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01329-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallscheuer N, Moreira C, Airs R, Llewellyn CA, Wiegand S, Jogler C, Lage OM. Pink-and orange-pigmented Planctomycetes produce saproxanthin-type carotenoids including a rare C45 carotenoid. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2019;11:741–748. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallscheuer N, Wiegand S, Jogler M, Boedeker C, Peeters SH, Rast P, Heuer A, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler C. Rhodopirellula heiligendammensis sp. nov., Rhodopirellula pilleata sp. nov., and Rhodopirellula solitaria sp. nov. isolated from natural or artificial marine surfaces in Northern Germany and California, USA, and emended description of the genus Rhodopirellula. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallscheuer N, Wiegand S, Peeters SH, Jogler M, Boedeker C, Heuer A, Rast P, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler C. Description of three bacterial strains belonging to the new genus Novipirellula gen. nov., reclassificiation of Rhodopirellula rosea and Rhodopirellula caenicola and readjustment of the genus threshold of the phylogenetic marker rpoB for Planctomycetaceae. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallscheuer N, Wiegand S, Boedeker C, Peeters SH, Jogler M, Rast P, Heuer A, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler C. Aureliella helgolandensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel Planctomycete isolated from a jellyfish at the shore of the island Helgoland. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10482-020-01403-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallscheuer N, Wiegand S, Heuer A, Rensink S, Boersma AS, Jogler M, Boedeker C, Peeters SH, Rast P, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler C. Blastopirellula retiformator sp. nov. isolated from the shallow-sea hydrothermal vent system close to Panarea Island. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Oh H-S, Park S-C, Chun J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:346–351. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.059774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn T, Wiegand S, Boedeker C, Rast P, Heuer A, Jetten M, Schüler M, Becker S, Rohde C, Müller R-W, Brümmer F, Rohde M, Engelhardt H, Jogler M, Jogler C. Planctopirus ephydatiae, a novel Planctomycete isolated from a freshwater sponge. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2020;43:126022. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2019.126022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König E, Schlesner H, Hirsch P. Cell wall studies on budding bacteria of the Planctomyces/Pasteuria group and on a Prosthecomicrobium sp. Arch Microbiol. 1984;138:200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Gaurav K, Ch S, Ch VR. Roseimaritima sediminicola sp. nov., a new member of Planctomycetaceae isolated from Chilika lagoon. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:2616–2623. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachnit T, Fischer M, Kunzel S, Baines JF, Harder T. Compounds associated with algal surfaces mediate epiphytic colonization of the marine macroalga Fucus vesiculosus. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2013;84:411–420. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage OM, Bondoso J. Planctomycetes and macroalgae, a striking association. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:267. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M, Findeiss S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kim YO, Park S-C, Chun J. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:1100–1103. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay MR, Webb RI, Fuerst JA. Pirellulosomes: a new type of membrane-bounded cell compartment in planctomycete bacteria of the genus Pirellula. Microbiology-Uk. 1997;143:739–748. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Rodriguez-r LM, Konstantinidis KT. MyTaxa: an advanced taxonomic classifier for genomic and metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Blum M, Bork P, Bridge A, Brown SD, Chang H-Y, El-Gebali S, Fraser MI, Gough J, Haft DR, Huang H, Letunic I, Lopez R, Luciani A, Madeira F, Marchler-Bauer A, Mi H, Natale DA, Necci M, Nuka G, Orengo C, Pandurangan AP, Paysan-Lafosse T, Pesseat S, Potter SC, Qureshi MA, Rawlings ND, Redaschi N, Richardson LJ, Rivoire C, Salazar GA, Sangrador-Vegas A, Sigrist CJA, Sillitoe I, Sutton GG, Thanki N, Thomas PD, Tosatto SCE, Yong S-Y, Finn RD. InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D351–D360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann S, Wessels HJ, Rijpstra WIC, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Kartal B, Jetten MS, van Niftrik L. Isolation and characterization of a prokaryotic cell organelle from the anammox bacterium Kuenenia stuttgartiensis. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:794–802. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmann J, Abt B, Sikorski J. Present and future of culturing bacteria. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:711–730. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters SH, van Niftrik L. Trending topics and open questions in anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2019;49:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters SH, Wiegand S, Kallscheuer N, Jogler M, Heuer A, Jetten MS, Rast P, Boedeker C, Rohde M, Jogler C. Three marine strains constitute the novel genus and species Crateriforma conspicua in the phylum Planctomycetes. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilhofer M, Rappl K, Eckl C, Bauer AP, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Petroni G. Characterization and evolution of cell division and cell wall synthesis genes in the bacterial phyla Verrucomicrobia, Lentisphaerae, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes and phylogenetic comparison with rRNA genes. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3192–3202. doi: 10.1128/JB.01797-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruesse E, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. SINA: accurate high-throughput multiple sequence alignment of ribosomal RNA genes. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1823–1829. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q-L, Xie B-B, Zhang X-Y, Chen X-L, Zhou B-C, Zhou J, Oren A, Zhang Y-Z. A proposed genus boundary for the prokaryotes based on genomic insights. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:2210–2215. doi: 10.1128/JB.01688-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rast P, Glöckner I, Boedeker C, Jeske O, Wiegand S, Reinhardt R, Schumann P, Rohde M, Spring S, Glöckner FO. Three novel species with peptidoglycan cell walls form the new genus Lacunisphaera gen. nov. in the family Opitutaceae of the verrucomicrobial subdivision 4. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:202. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensink S, Wiegand S, Kallscheuer N, Rast P, Peeters SH, Heuer A, Boedeker C, Jetten MS, Rohde M, Jogler M, Jogler C. Description of the novel planctomycetal genus Bremerella, containing Bremerella volcania sp. nov., isolated from an active volcanic site, and reclassification of Blastopirellula cremea as Bremerella cremea comb. nov. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Marin E, Canosa I, Santero E, Devos DP. Development of genetic tools for the manipulation of the Planctomycetes. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:914. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-R LM, Konstantinidis KT. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ Preprints. 2016;4:e1900v1. [Google Scholar]

- Santarella-Mellwig R, Pruggnaller S, Roos N, Mattaj IW, Devos DP. Three-dimensional reconstruction of bacteria with a complex endomembrane system. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring S, Bunk B, Spröer C, Rohde M, Klenk HP. Genome biology of a novel lineage of planctomycetes widespread in anoxic aquatic environments. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:2438–2455. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E, Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today. 2006;33:153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strous M, Fuerst JA, Kramer EH, Logemann S, Muyzer G, Van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Webb R, Kuenen JG, Jetten MS. Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete. Nature. 1999;400:446–449. doi: 10.1038/22749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Teeseling MC, Mesman RJ, Kuru E, Espaillat A, Cava F, Brun YV, VanNieuwenhze MS, Kartal B, Van Niftrik L. Anammox Planctomycetes have a peptidoglycan cell wall. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6878. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmers J, Frentrup M, Rast P, Jogler C, Kaster A-K. Untangling genomes of novel Planctomycetal and Verrucomicrobial species from Monterey bay kelp forest metagenomes by refined binning. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:472. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Horn M. The Planctomycetes, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae and sister phyla comprise a superphylum with biotechnological and medical relevance. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner CE, Richter-Heitmann T, Klindworth A, Klockow C, Richter M, Achstetter T, Glockner FO, Harder J. Expression of sulfatases in Rhodopirellula baltica and the diversity of sulfatases in the genus Rhodopirellula. Mar Genom. 2013;9:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand S, Jogler M, Jogler C. On the maverick Planctomycetes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42:739–760. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand S, Jogler M, Boedeker C, Pinto D, Vollmers J, Rivas-Marín E, Kohn T, Peeters SH, Heuer A, Rast P, Oberbeckmann S, Bunk B, Jeske O, Meyerdierks A, Storesund JE, Kallscheuer N, Lücker S, Lage OM, Pohl T, Merkel BJ, Hornburger P, Müller R-W, Brümmer F, Labrenz M, Spormann AM, Op den Camp HJM, Overmann J, Amann R, Jetten MSM, Mascher T, Medema MH, Devos DP, Kaster A-K, Øvreås L, Rohde M, Galperin MY, Jogler C. Cultivation and functional characterization of 79 planctomycetes uncovers their unique biology. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:126–140. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0588-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Pruesse E, Glöckner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H, Whitman WB, Euzéby J, Amann R, Rosselló-Móra R. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.