Abstract

Background:

Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) is a lysosomal storage disease caused by mutations in NPC1 or NPC2 genes.

Case presentation:

We present two brothers with the same compound heterozygous variants in exon 13 of the NPC1 gene (18q11.2), the first one (c.1955C> G, p. Ser652Trp), inherited from the mother, the second (c.2107T>A p.Phe703Ile) inherited from the father, associated to the classical biochemical phenotype of NPC. The two brothers presented unspecific neurologic symptoms with difference in age of onset: one presented and previously described dyspraxia and motor clumsiness at age 7 years, the other showed a systemic presentation with hepatosplenomegaly noted at the age of two months and neurological symptoms onset at age 4 with speech disturbance. Clinical evolution and neuroimaging data led to the final diagnosis. Systemic signs did not correlate with the onset of neurological symptoms. Miglustat therapy was started in both patients.

Conclusions:

We highlight the extreme phenotypic heterogeneity of NP-C in the presence of the same genetic variant and the unspecificity of neurologic signs at onset as previously reported. We report some positive effects of miglustat on disease progression assessed also with neuropsychological follow-up, with an age-dependent response.

Keywords: Niemann–Pick disease, Type C; lysosomal storage disorder; phenotypic heterogeneity; heterozygous missense mutation; early infantile onset; supranuclear gaze palsy; early diagnosis; miglustat.

Background

Niemann–Pick disease type C (NP-C) is a neurovisceral lysosomal storage disorder, characterized by intracellular accumulation of unesterified cholesterol and other compounds1. Estimated incidence is 1:100.0002. Clinical presentation is heterogeneous, encompassing progressive and disabling unspecific neurological symptoms3. It is subdivided as pre/peri-natal (< 3 months), early-infantile (3 months–2 years), late-infantile (2–6 years), juvenile (6-15 years) and adolescent/adult (>15 years)4 based on neurological manifestations onset. In juvenile and adolescent-onset patients, intellectual disability, behavioral problems and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been reported3 before the onset of neurological symptoms2. Prognosis is generally poor (death in late teenage years/early adulthood)2. NP-C is caused by pathogenic variants in the NPC1 gene in 95% of cases, referred to as type C1 (OMIM*257220); 5% are caused by mutations in the NPC2 gene, referred to as type C2 (OMIM*607625)1, 4.

Miglustat, a reversible inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthase, is the first treatment approved for treating neurological complications in patients with NP-C. Its beneficial effects are limited in patients with the early-infantile form in advanced stages5.

Case Presentation

Case Report 1

He is a 12-year-old boy born via caesarean section for fetal distress at 32 weeks (birth weight 1350 g). Family history was unremarkable.

At 7 years, visuo-spatial and learning difficulties were noted (dysgraphia, dyspraxia, and motor clumsiness). At 9 years, autism spectrum disorder was suspected due to poor eye contact and repetitive behavior.

He came to our attention at 9 years and 10 months with progressive cognitive impairment, memory disturbances, dyspraxia, gait abnormalities, episodes of transient loss of contact and abnormal saccadic eye movements.

Brain MRI showed cerebellar abnormalities, ventricular enlargement and white matter abnormalities (Figure 1). Biochemical analysis showed mild hypertransaminasemia (AST> 50 U/I), mild hypercholesterolemia (LDL>120 mg/dl), transient hypertriglyceridemia (203 mg/dl; 309 mg/dl). Splenomegaly was noted. NPC suspicion Index was 104 (high likelihood)6. At 10 years he had epileptic seizures, controlled on valproate.

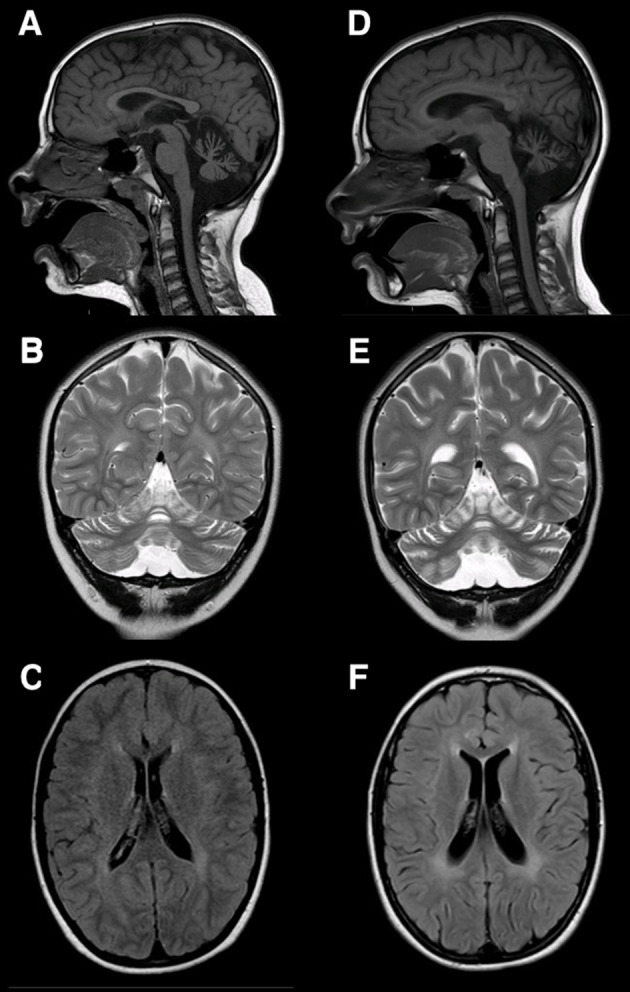

Figure 1.

(A, B, C) Brain MRI of Patient 1at 10 years of age. Reduced volume of the cerebellum and vermis, more prominent superiorly, associated to a slight reduction of the superior and middle cerebellar peduncles with increased volume of the fourth ventricle and the cisterna magna (A, B), slight increase of the white matter signal intensity at the supratentorial level (C). (D, E, F): At 11 years and 6 months of age, mild worsening of the cerebellar atrophy at the level of the anterior cerebellar lobes (D, E). The periventricular white matter signal enhancement is more clearly delineated (F).

Molecular genetic testing by PCR sequencing on NPC1 gene revealed two heterozygous variants in exon 13, (c.1955C>G [Ser652Trp]), maternally-inherited and previously described and previously described,7 and (c.2107T>A [Phe703Ile]) paternally-inherited. Oxysterols 7-ketocholesterol elevation (310.5 ng/ml normal values: < 45.58 ng/ml) confirmed the diagnosis.

Six weeks after diagnosis, treatment with Miglustat was started (600mg/die). Follow-up after ten months revealed worsening of balance, speech apraxia and severe dysmetria. Some clinical parameters showed stabilization and improvement after 9 months of treatment. Prevention of dysphagia as well as improvement in attentional levels was noted. However, brain MRI, at 18 months follow-up, showed worsening of periventricular white matter signal and progression of cerebellar atrophy. At 12 years of age, cognitive profile shows multidomain cognitive impairment, with spared receptive vocabulary and comprehension of simplified sentences (see table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data of our two patients

| Neuropsychological follow-up of patient 1 | ||||

| Test and subtests | Timeline | |||

| 8 year and 3 month | 9 years and 2 months | |||

| WISC-IV | ||||

| Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) | 100 | |||

| Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) | 87 | |||

| Working Memory Index (WMI) | 64* | |||

| Processing Speed Index (PSI) | 71* | |||

| IQ Score | 77 | |||

| Raven CPM | -1,5 SD | |||

| MMSP-E | -2 SD | |||

| BVN 5-11 | ||||

| Digit span | 90 | |||

| Word pairs learning | n.e.* | |||

| Word free recall | 80 | |||

| Word list - immediate recall | 65* | |||

| Word list - delayed recall | 65* | |||

| Attentional matrices | -2 SD | |||

| BVN 5-11 | ||||

| Reception of grammar | <60* | |||

| Semantic fluency | average | |||

| Phonemic contrast | -2 SD | |||

| DDE-2 | ||||

| Word reading (prova 2) | -1,76 SD* | |||

| Nonword reading (prova 3) | -2 SD* | |||

| Word writing (prova 6) | -2 SD* | |||

| Nonword writing (prova 7) | -2 SD* | |||

| BVSCO-2 | ||||

| Text writing | -2 SD* | |||

| MT | ||||

| Text reading | -1,55 SD | |||

| Text comprehension | severe* | |||

| AC-MT | ||||

| Calculations skills | borderline* | |||

| Knowledge of numbers | severe* | |||

| Accurancy | average | |||

| Time | severe* | |||

| Neuropsychological follow-up of patient 2 | ||||

| Test and subtests | Timeline | |||

| 7 years and 5 months | 8 years and 8 months | 11 years and 8 motnhs | ||

| WISC-IV | n.e.* | |||

| Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) | 86 | |||

| Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) | 67* | |||

| Working Memory Index (WMI) | 73 | |||

| Processing Speed Index (PSI) | 47* | |||

| IQ Score | 58* | |||

| WISC-III | ||||

| Verbal IQ | 112 | |||

| Performance IQ | 66* | |||

| IQ Score | 88 | |||

| Raven CPM | n.e.* | |||

| MMSP-E | n.e.* | |||

| BVN 5-12 | ||||

| Visual Span | <60* | |||

| Leiter-R | ||||

| Attention sustained | average | |||

| MF | ||||

| Average response time | +0.7 SD | |||

| Errors | -2.3 SD* | |||

| VMI | ||||

| Motor coordination | 70 | |||

| Visual perception | 48* | |||

| Visual-motor integration | severe* | |||

| BVN 5-12 | ||||

| Imitation of gestures | <60* | |||

| DDE-2 | n.e.* | |||

| Word reading (prova 2) | ||||

| Speed | -0.5 SD | |||

| Errors | -1.5 SD* | |||

| Word writing (prova 6) | -2.2 SD* | |||

| Nonword writing (prova 7) | -2.6 SD* | |||

| BVSCO-2 | n.e.* | |||

| Text writing | -2.5 SD* | |||

| BHK | n.e.* | |||

| Speed | -1.5 SD* | |||

| Accurancy | -1.3 SD* | |||

| MT | n.e.* | |||

| Text comprehension | average | |||

| TROG-2 | ||||

| Reception of grammar | n.e. | |||

| Receptive vocabulary | average | |||

| AC-MT | n.e.* | |||

| Calculations skills | borderline* | |||

| Knowledge of numbers | average | |||

| Accurancy | average | |||

| Time | average | |||

| Test | Description | References |

| A battery of neuropsychological tests developed for children aged from 5 to 11 years old (BVN 5-11) | Comprehensive neuropsychological battery | Bisiacchi, P. S., Cendron, M., Gugliotta, M., Tressoldi, P. E., & Vio, C. (2005). BVN 5-11: batteria di valutazione neuropsicologica per l’età evolutiva. Centro studi Erickson. |

| AC-MT arithmetic achievement test | Measurement of math skills in children between ages 6 to 11, | Cornoldi, C., Lucangeli, D., & Bellina, M. (2002). AC-MT Test: Test per la valutazione delle difficoltà di calcolo [The AC-MT arithmetic achievement test]. Trento, Italy: Erickson. |

| Assessment Scale for Children’s Handwriting (BHK) | Evaluation scale for children’s handwriting | Di Brina, C., & Rossini, G. (Eds.). (2010). BHK. Scala sintetica per la valutazione della scrittura in età evolutiva. Edizioni Erickson. |

| Attention Matrices | Three matrices of numbers, administered with the instruction to cross out as fast as possible target numbers of either one, two or three digits. The purpose of this test was to assess the subjects’ ability to detect visual targets among distractors. | Scarpa, P., Piazzini, A., Pesenti, G., Brovedani, P., Toraldo, A., Turner, K., ... & Canger, R. (2006). Italian neuropsychological instruments to assess memory, attention and frontal functions for developmental age. Neurological Sciences, 27(6), 381-396. |

| Battery for the assessment of writing skills in children from 7 to 13 years old (BVSCO-2) | Assessment of writing skills | Tressoldi, P., Cornoldi, C., & Re, A. M. (2013). BVSCO-2 Batteria per la Valutazione della Scrittura e della Competenza Ortografica-2. Firenze: Giunti-OS. |

| Battery for the evaluation of dyslexia and dysorthographia (DDE-2) | Assessment of dyslexia and dysorthographIA | Job, R., Sartori, G., & Tressoldi, P. E. (1995). Battery for the evaluation of dyslexia and dysorthographia. Firenze, Italy: Organizzazioni Speciali. |

| Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R) | Nonverbal measure of intellectual functioning normed for individuals between the ages of 2 years 0 months and 20 years 11 months. | Roid, G. H., & Miller, L. J. (1997). Leiter-r. Leiter International Performance Scale–Revised. Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting CO. |

| MT tests of reading comprehension for the middle school | Evaluation of reading and comprehension | Cornoldi, C., & Colpo, G. (1995). Nuove prove MT per la scuola media [New MT tests of reading comprehension for the middle school] Florence. Italy: Organizzazioni Speciali. |

| Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices (CPM) | Typically used in measuring abstract reasoning and regarded as a non-verbal estimate of fluid intelligence. | Belacchi, C., Scalisi, T. G., Cannoni, E., & Cornoldi, C. (2008). CPM coloured progressive matrices: standardizzazione italiana: manuale. Giunti OS. |

| Semantic fluency | Category fluency test | Marini, A., Tavano, A., & Fabbro, F. (2008). Assessment of linguistic abilities in Italian children with specific language impairment. Neuropsychologia, 46(11), 2816-2823. |

| Test for reception of grammar (TROG-2) | Measure understanding of grammatical contrasts. Test understanding of 20 constructs four times each using different test stimuli. | Bishop, D. V. M. (2009). TROG 2: Test for Reception of Grammar-Version 2. Edizioni Giunti OS |

| The Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration (VMI) | Assessment of the extent to which individuals can integrate their visual and motor abilities | Beery, K. E. (2015). VMI: developmental test of visual-motor integration: il Beery-Buktenica con i test supplementari di percezione visiva e coordinazione motoria: manuale. Giunti. Organizzazioni speciali. |

| Visual Matching Test | Visual Matching Test with 20 items adapted from the Matching Familiar Figure Test (MFFT), derived from the Italian battery for the assessment of children with attention/hyperactivity deficits (BIA) | Marzocchi, G. M., Re, A. M., & Cornoldi, C. (2010). BIA–Batteria Italiana per l’ADHD. Erickson, Trento. |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III) | Individually administered intelligence test for children between the ages of 6 and 16 | Orsini, A., & Picone, L. (2006). Contributo alla taratura italiana di Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III). Firenze: Giunti OS. |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV) | Individually administered intelligence test for children between the ages of 6 and 16. | Wechsler, D., Orsini, A., & Pezzuti, L. (2012). WISC-IV: Wechsler intelligence scale for children: manuale di somministrazione e scoring. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali. |

Case Report 2

Case 2, now 9 years-old, was born at 32 weeks (weight 1390 g). He presented axial hypotonia and neonatal jaundice. Aged 2 months, hepatosplenomegaly was detected. Motor development was normal. He was diagnosed with speech delay at 4 years and with learning disability at 8 years of age. He came to our attention at 8 years and 9 months of age showing mild dysarthria and impaired vertical saccades. Neuropsychological profile demonstrated multidomain cognitive impairment (see table 2). Bilateral sovra- and peritrigonal white matter hyperintensity in long TR sequences was detected on brain MRI at 9 years of age (figure 2). EEG showed bi-frontal slow sharp waves. Biochemical analysis showed mild hypertransaminasemia (AST 60U/I). Mild hepatosplenomegaly was diagnosed on abdominal ultrasound. Treatment with Miglustat (400mg/die) was initiated at 9 years and 2 months of age, after genetic confirmation of the same variants as his brother.

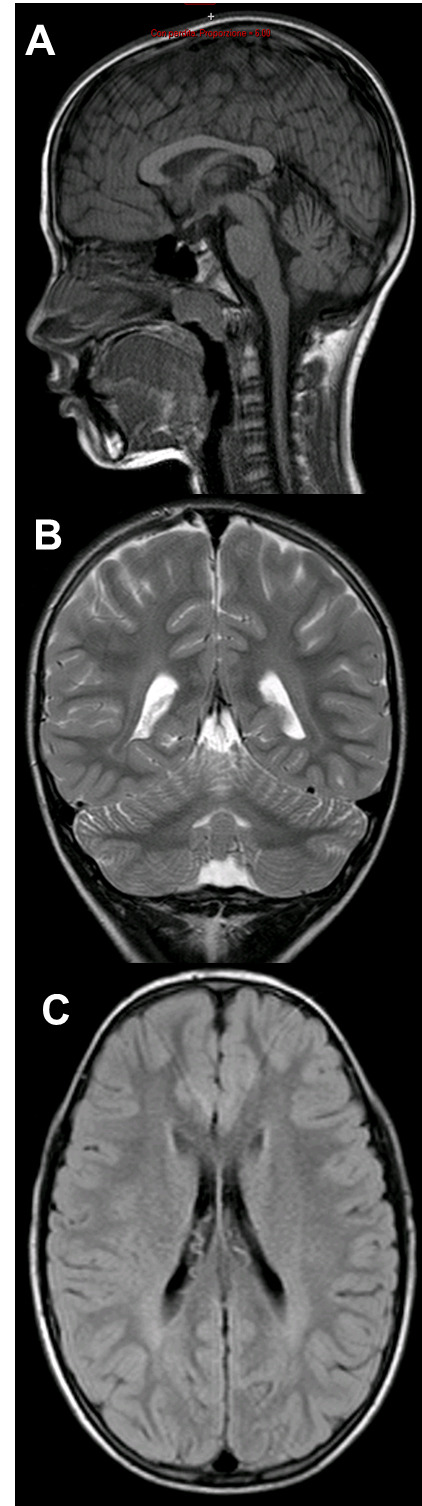

Figure 2.

A, B, C) Brain MRI of Patient 2: At 9 years of age, mild bilateral white matter hyperintensity in the sovra- and peritrigonal regions in long-TR sequences.

Discussion

We report on two brothers with juvenile and early infantile onset NPC harbouring the same compound heterozygous missense variants (c.1955C>G p.Ser652Trp) and (c.2107T>A Phe703Ile) in the NPC1 gene, resulting in different phenotypes and disease courses. The variant c.1955C> G, p. [Ser652Trp] has been previously described in homozigosity, associated with severe biochemical phenotype. However, detailed clinical information is unavailable and a severe clinical phenotype does not necessarily correlate with the severity of biochemical and genetic profile7.

The variant c.2107T>A [Phe703Ile] to the best of our knowledge has not been previously reported. According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), it fulfills the following points: PM1 (located in a mutational hot spot and/or critical and well-established functional domain) PM2 (absent in gnomAD control population), PM5 (novel missense change at an amino acid residue where a different missense change determined to be pathogenic has been seen before) PP2 (missense variant in a gene that has a low rate of benign missense variation and in which missense variants are a common mechanism of disease), PP3 (multiple lines of computational evidence support a deleterious effect on the gene or gene product (conservation, evolutionary, splicing impact, etc.): thus classified as likely pathogenic.

In both cases a sneaky neurologic debut was present in childhood. However, neonatal jaundice and persistent splenomegaly might be considered the first symptoms, thus implying a neonatal/early-infantile onset.

Both cases confirm that timing of systemic symptoms onset does not correlate with neurological onset. Otherwise, age at neurological symptoms onset is associated with disease progression severity4.

Phenotypic variability has been previously described in sibilings8. Furthermore, two monozygotic twins carrying the same homozygous causative variant have been described: one had an adult late-onset form, the second isolated splenomegaly9. It is possible to speculate that this variability might depend on modifier genes and epigenetic interaction10-11.

Phenotypic heterogeneity is misleading in differential diagnosis with other child neuropsychiatric disorders including learning disorders, autism, speech delay, behavior, mood and thoughts disorders, with a risk for delay in diagnosis.4

Impairment in cognitive functions markedly correlates with age at therapy initiation5. Many authors also demonstrated that Miglustat stabilizes or might improve neurological signs5.

Conclusions

We presented two brothers with the same genotype but a different neurological picture, confirming extensive clinical heterogeneity and absence of clear genotype-phenotype correlations in NPC1.

We recommend to consider NP-C in unspecific neuropsychiatric disorders, especially in progressive cases, and never underestimate isolated or persistent hepatosplenomegaly/splenomegaly, or eye movements abnormalities.

Early diagnosis is crucial for a timely pharmacological intervention, in order to prevent irreversible neurological damage and thus change the course of the disease, improve patients’ quality of life and extend life expectancy.

Neuropsychological scores and description of tests are extensively reported in Supplementary Material 1.

Abbreviations

- ACMG:

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

- AST:

aspartate aminotransferase;

- EEG:

electroencephalogram;

- LDL:

low density lipoprotein;

- MRI:

magnetic resonance imaging;

- NP-C:

Niemann Pick type C;

- NPC1:

Niemann Pick type C 1;

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Zech M, Nübling G, Castrop F, Jochim A, Schulte EC, Mollenhauer B, et al. Niemann-Pick C disease gene mutations and age-related neurodegenerative disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans W, Hendriksz C. Niemann–Pick type C disease–the tip of the iceberg? A review of neuropsychiatric presentation, diagnosis and treatment. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(2):109–114. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.116.054072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson MC, Hendriksz CJ, Walterfang M, Sedel F, Vanier MT, Wijburg F. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Niemann-Pick disease type C: An update. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106:330–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanier MT. Niemann-Pick disease type C. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.M Pineda, M Walterfang. M. Patterson Miglustat in Niemann-Pick disease type C patients: a review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2018;13:140. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0844-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wijburg FA, Sedel F, Pineda M, Hendriksz CJ, Fahey M, Walterfang M, et al. Development of a Suspicion Index to aid diagnosis of Niemann-Pick disease type C. Neurology. 2012;78:1560–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563b82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garver WS, Jelinek D, Meaney FJ, Flynn J, Pettit KM, Shepherd G, et al. The National Niemann-Pick Type C1 Disease Database: correlation of lipid profiles, mutations, and biochemical phenotypes. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:406–15. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tozza S, Dubbioso R, Iodice R, Topa A, Esposito M, Ruggiero L, Spina E, De Rosa E, Sacca’ F, Santoro L, Manganelli F. Long-term therapy with miglustat and cognitive decline in the adult form of Niemann-Pick disease type C: a case report. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benussi A, Alberici A, Premi E, Bertasi V, Cotelli MS, Turla M. Phenotypic heterogeneity of Niemann-Pick disease type C in monozygotic twins. J Neurol. 2015;262:642–647. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu R, Yanjanin NM, Elrick MJ, Ware C, Lieberman AP, Porter FD. Apolipoprotein E genotype and neurological disease onset in Niemann-Pick disease, type C1. Am J Med Genet A. Nov 2012;158A(11):2775–80. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New Niemann-Pick type C1 gene mutation associated with very severe disease course and marked early cerebellar vermis atrophy. Fusco C, Russo A, Galla D, Hladnik U, Frattini D, Giustina ED. J Child Neurol. 2013 Dec;28(12):1694–7. doi: 10.1177/0883073812462765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]