To the Editor,

the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has had a deep impact on the Italian Healthcare system with the need of a prompt and deep structural and environmental reorganization of the Emergency Departments (ED) to avoid the collapse of the entire system. As a consequence, COVID-19 has dramatically and rapidly changed the working routine in the EDs with the born of new roles and skills, in order to manage both the great influx of patients and to avoid the spread of the infection within the so called “clean area” (1, 2, 3). It is clear that all the emergency workers have carried a huge responsibility in this pandemic, not only for the management of COVID-19 patients, but more importantly, to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (4). Worldwide countries have respondend differently to the virus outbreak. Italy has fight hard against COVID-19 since the begininning of the Italian epidemic on 21st February 2020. On 8th-9th March 2020 a national decree instituted a containment zone, the so called “Red zone”, concerning the most affected areas in three regions of the Northern Italy, Lombardia, Emilia-Romagna and Veneto. Restrictive measures included lockdown, social distancing and encouraging employees to work from home. On 11st March 2020 the Italian Prime Minister estabilished the national lockdown and the WHO declared the novel SARS-CoV-2 outbreak a pandemic (5).

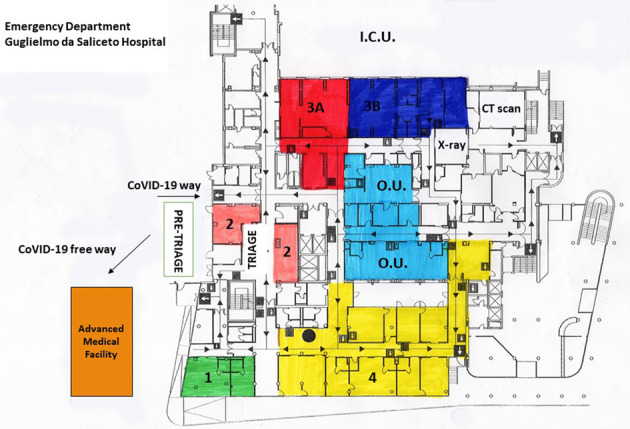

As recently reported by Maniscalco et al. (6) COVID-19 had a deep impact on the organization of the “Guglielmo da Saliceto” hospital in Piacenza, one of the Italian epicenters of COVID-19 epidemic. Our hospital is the main hospital with a hub-and-spoke organization, a Radiology Department and an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for all the inhabitants of Piacenza and the surrounding four valleys - Val Nure, Val d’Arda, Val Tidone, Val Trebbia (for a total of 287172 inhabitants at 2019). For this reason, our hospital has wickly become a COVID-19 hospital with a great effort for the Emergency Department (ED). The dramatic and difficult situation with the high wave of critically ill patients affected by acute respiratory failure admitted to our Emergency Room during the first month of the Italian epidemic (2284 COVID-19 patients from 21st February to 21st March 2020), and the limited chance of being admitted to ICU has pushed us to change our working organization and develop a strategy to avoid our complete collapse with catastrophic consequences (2). We promptly increased the number of emergency clinicians, moved away the Traumatology and Orthopedics Department in another local building in Piacenza (6), and designed a disaster plan. We divided the ED into seven areas (Figure 1): two areas for patients with acute respiratory failure who required non invasive ventilation (CPAP/NIV) or who were candidates for intubation, waiting to be hospitalized in the ICU or the Emergency Medicine (area 3A and 3B, total 28 beds), one for patients with mild symptoms who required oxygen therapy (area 2, 12 beds), and one for patients without respiratory failure (area 1). We turned our Observation Unit into a Subintensive Care Ward for patients hospitalized for ARDS who needed CPAP/NIV (IOU, 13 beds), and we created a “temporary COVID-19 ward” of 40 beds (area 4) for patients waiting for admission to two COVID-19 hospitals located in Castel San Giovanni (128 beds) and Fiorenzuola d’Arda (61 beds), and the Military Hospital, set up in Piacenza for COVID-19 disaster (40 beds). In addition, a “free COVID-19 first aid station” (Advanced Medical Facility) has been arranged outside the hospital, in front of the entry of the ED, to ensure a “free COVID-19 way”. Each area, including the Advanced Medical Facility, had a dedicated medical staff made by an emergency clinician and 1 or 2 expert nurses, and an ultrasound workstation (7). The area 4 had also an extra medical team of 2 clinicians and 2 non-expert nurses. Before being admitted to the ED, all the patients had been firstly evaluated by a triage nurse (Figure 1, PRE-TRIAGE), who divided the patients according the presence/absence of COVID-19 symptoms (clinical and epidemiological criteria) into two pathways: COVID-19 or free COVID-19. In the triage area (Figure 1, TRIAGE) an expert nurse drove the correct flux of suspected COVID-19 patients through the different 6 areas according to the severity of the respiratory symptoms. Two bed managers furthermore handled all the patients’ hospitalization and transfer 7/7 days and 12/24 hours.

Figure 1.

Emergency Department’s planimetry at the time of CoVID-19 outbreak

We tried to provide the highest possible level of care to all the patients, being aware of our limited resources. In such a disaster situation with more patients requiring mechanical ventilation than the number of available ventilators, we shared every decision-making process between us and intensivists, avoinding a single person decision, and we created a palliative care unit (PCU) for end-stage patients (12 beds powered by a team of palliative care specialists and surgeons). We tried to give better chances to those patients who have the highest probability to benefit from intensive care. Instead, in presence of poor prognosis in patients with older age and severe comorbidities or end-stage diseases, based on the Italian Society for Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (Società Italiana di Anestesia Analgesia Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva, SIAARTI) document (8), we shared the decision with intensivists not to intubate the patient, but to treat symptoms such as pain, secretions and dyspnoea using continuous palliative sedation starting from the ED and to admit immediately the patient to the PCU. We always informed the patients’ families when patients took a turn for the worse and/or die, and in presence of refractory suffering, we shared with the patient’s family the decision to start continuous palliative sedation based on morphine for pain and dyspnoea, midazolam for agitation, haloperidol for delirium, and scopolamine for secretions (Italian Law 219/2017 art. 2). The weight of this decision hurted us terribly, particularly because of the lack of the patient’s family, that is paramount in this context.

We believe that in complex situations such as COVID-19 pandemic, there is not a unique best way to manage the disaster. We strongly suggest to maintain flexibility and proactivity in the process of problem solving, to coordinate all the efforts avoiding energy loss and waste, to strictly and strongly collaborate with intensivists and palliative care specialists to ensure the best strategy for each patient avoiding over- and undertreatment. Every hospital should develop a project in respond to maxiemergencies, as COVID-19 pandemic has been, in order to support all the emergency clinicians to ensure the best possible management for all patients, including intensive care and on the opposite end, high-quality palliative care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the staff of the “Guglielmo da Saliceto” Hospital for their help, energy and complete dedication to face such a difficult public health crisis. A special thanks to Dr. Fabio De Iaco and all the SAU group (SIMEU) for their precious teaching in pain management.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Comelli I, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on census, organization and activity of a large urban Emergency Department. Acta Biomed. 2020 May. 11;91(2):45–49. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9565. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poggiali E, et al. Triage-decision making at the time of COVID-19 infection: the Piacenza strategy. Internal and Emergency Medicine. accepted 16 April 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giamello JD, et al. The emergency department in the COVID-19 era. Who are we missing. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020 Apr 27 doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000718. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000718. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freund Y. The challenge of emergency medicine facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020 Jun;27(3):155. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000699. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The World Health Organization (WHO) Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 . Accessed March 22nd 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maniscalco P, et al. The Deep Impact of Novel CoVID-19 Infection in an Orthopedics and Traumatology Department: The Experience of the Piacenza Hospital. Acta Biomed. 2020 May 11;91(2):97–105. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9635. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poggiali E, et al. Can lung ultrasound help critical care clinicians in the early diagnosis of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200847. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. http://www.siaarti.it/News/grandi-insufficienze-organo-end-stage-cure-intensive-o-cure palliative.aspx . [Google Scholar]