Abstract

Focused ultrasound (FUS) is an emerging technique for neuromodulation due to its noninvasive application and high depth penetration. Recent studies have reported success in modulation of brain circuits, peripheral nerves, ion channels, and organ structures. In particular, neuromodulation of peripheral nerves and the underlying mechanisms remain comparatively unexplored in vivo. Lack of methodologies for FUS targeting and monitoring impede further research in in vivo studies. Thus, we developed a method that non-invasively measures nerve engagement, via tissue displacement, during FUS neuromodulation of in vivo nerves using simultaneous high frame-rate ultrasound imaging. Using this system, we can validate, in real-time, FUS targeting of the nerve and characterize subsequent compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) elicited from sciatic nerve activation in mice using 0.5 to 5 ms pulse durations and 22 – 28 MPa peak positive stimulus pressures at 4 MHz. Interestingly, successful motor excitation from FUS neuromodulation required a minimum interframe nerve displacement of 18 μm without any displacement incurred at the skin or muscle levels. Moreover, CMAPs detected in mice monotonically increased with interframe nerve displacements within the range of 18 to 300 μm. Thus, correlation between nerve displacement and motor activation constitutes strong evidence FUS neuromodulation is driven by a mechanical effect given that tissue deflection is a result of highly focused acoustic radiation force.

Keywords: acoustic radiation force, displacement imaging, focused ultrasound, neuromodulation, peripheral nerves

I. Introduction

Noninvasive focused ultrasound (FUS) has been gaining attention as a promising method to stimulate electrically excitable tissues. Since 1929, FUS has been shown to evoke a plethora of neuromodulatory responses in various in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro studies [1]–[16]. The superior target specificity and depth of penetration of non-invasive FUS demonstrated in the brain and the peripheral nerves make it a strong alternative to the current neuromodulation therapeutic methods [1], [17]. Since FUS can generate complex bioeffects, thermal and mechanical, it is an incredibly attractive therapeutic for conditions such as neuropathic pain if selective effects can be identified.

From previous studies, we know that high pressure, short pulse FUS can stimulate nerves in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), indicating a radiation force-based mechanism [1]. Accordingly, a recent study from Menz et al. 2019 has provided ex vivo evidence of a dominant radiation force based mechanism in retinal cells [11]. However, as of now, no study has investigated this mechanism in vivo. Moreover, since the underlying mechanism of FUS neuromodulation remains largely unknown, contradictory reports of excitation and inhibition of neural activity in the same biological system and similar FUS parameters have been reported [18]–[20]. The lack of accurate and informed confirmation of FUS targeting of the desired structure may explain these contradictions. Moreover, such a method would limit undesirable off-target effects that may result in mixed or inconclusive results.

Tissue displacement is caused by nonlinear acoustic radiation force interaction with tissue; the tissue at the focus is displaced in the direction of ultrasound propagation. Many modern ultrasound elastography techniques use this phenomenon to image tissue displacement and measure tissue elasticity [21]–[24]. Conventional techniques traditionally do not image during FUS sonication, where acoustic radiation force is at a maximum, and instead, image after sonication has ceased. However, some groups have shown that, with the necessary filtering[25], ultrasound images can be recovered during the FUS pulse and can be used to track displacements such as in shear wave elasticity imaging (SWEI)[26] or harmonic motion imaging (HMI)[27]. Moreover, promising advances in real-time magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging (MR-ARFI) of FUS displacement and temperature have been reported [28]–[32]. However, the short pulses used in peripheral neuromodulation require high temporal resolution and are much faster than pulses used in SWEI, HMI, and MR-ARFI. Since, neuromodulation occurs during sonication, imaging displacement during the pulse would not only facilitate targeting and validation of FUS delivery, but would provide insights into acoustic radiation force contribution to neuromodulation in vivo.

Thus, to address this gap, we developed a real-time, noninvasive targeting and monitoring technique for peripheral neuromodulation to not only estimate mechanical nerve deflection during FUS but also to elucidate the contribution of acoustic radiation force to nerve activation in vivo. The following novel contributions of this study are as follows:

We illustrate that high frame-rate ultrasound imaging can image acoustic radiation force-induced tissue displacements during FUS neuromodulation pulses.

We characterize CMAP amplitude and nerve displacements based on pressure and pulse duration using our developed technique.

We provide a correlation between acoustic radiation force, via nerve displacement, and CMAP amplitude.

The sciatic nerve, being a mixed sensory and motor nerve bundle, was chosen so that muscle activation, measured by electromyography (EMG), could be used as a metric for successful stimulation. This imaging technique provides real-time feedback of the actual FUS beam used for nerve excitation and serves as an essential tool not only for safety and in vivo targeting confirmation, but also to advance the investigations of FUS neuromodulation mechanisms.

II. Materials and Methods

A. Ultrasound neuromodulation system

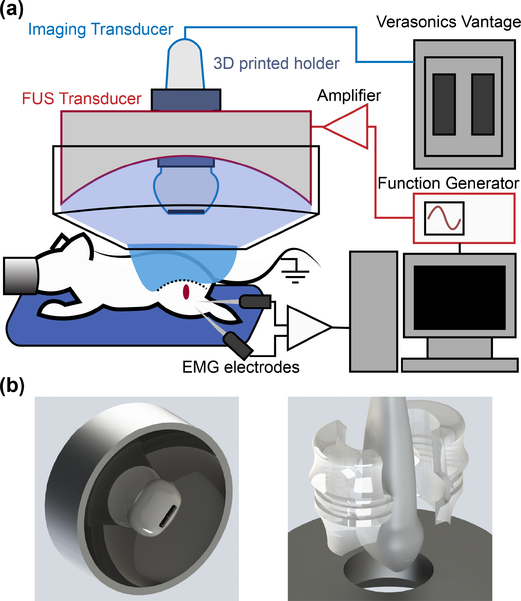

The experimental setup in Fig. 1(a) was used to activate the sciatic nerve in anesthetized mice. Two commercially available ultrasound transducers were used in a confocally aligned configuration: A FUS stimulation transducer (H-215, 4 MHz, single-element FUS; Sonic Concepts Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) and an imaging array (L22–14vX-LF, 16 MHz, 128 elements linear array; Vermon, Tours, France). The imaging transducer was inserted through a central opening in the FUS transducer and were coaligned using a 3D-printed attachment through a central opening in the FUS transducer and with the faces of both transducers 15 mm apart. The attachment was designed in a CAD program (Solidworks; Dassault Systemes, Waltham, MA, USA) and printed in clear resin in a 3D printer (Form2; Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA) using the direct dimensions of the imaging transducer provided by the manufacturer (Fig. 1(b)). The part puts the focus of the FUS transducer within the imaging plane of the imaging transducer. Since both transducers are driven simultaneously, the center frequencies were chosen to be as separate as possible, reducing FUS interference. A function generator (33220a; Keysight Tech., Santa Rosa, CA, USA) amplified by a 150 W RF power amplifier (A150; E&I, Rochester, NY, USA) drove the FUS transducer. Imaging transmit and receive events were acquired using a research ultrasound system (Vantage 256; Verasonics Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) research platform. Ultrasound was transmitted through a coupling cone filled with degassed water and degassed ultrasound gel coupled to the upper thigh of the mouse.

Fig. 1.

(a) Ultrasound transducer setup for neuromodulation of in vivo sciatic nerves. All recording and stimulating sequences are controlled via a central computer. (b) 3D CAD designs of the transducer system with the custom designed imaging transducer holder. The holder positions the focus of the FUS transducer in the center of the imaging plane.

B. Animal preparation

Male C57BL/6J mice, weighing between 22g to 28g, were used in all experiments (n = 6). Male mice were used to decrease variability between animals and to compare with our previous study by Downs et al. 2018 [1]; we have not found nerve excitability differences between male or female mice (see Appendix B). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane: 4% during induction and preparation, 2% during the procedure. Physiological saline (0.1 mL per 10 g of body weight) was subcutaneously injected every 1–2 h to prevent dehydration. Mouse hind limbs were shaved and de-haired using a depilatory cream. An infrared heating pad was used to maintain proper body temperature (36.5°C) throughout all experiments (Fig. 1). The mouse was placed in a pronated orientation so that the sciatic nerve ran superficially below the skin.

C. Acoustic parameters

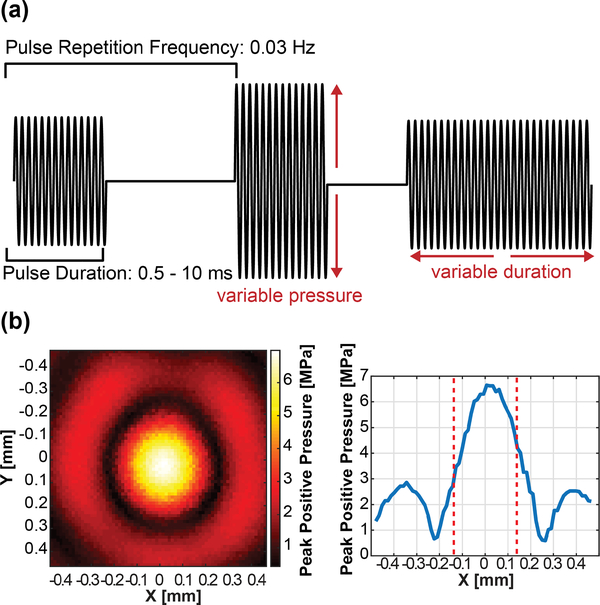

In this study the acoustic parameters that were varied were acoustic pressure and pulse duration. The acoustic pressure was varied from 4 to 30 MPa in steps of 4 MPa and the pulse duration was varied from 0.5 to 10 ms in steps of 0.5 ms. We established these ranges based on the success rate and safety analysis of our previous studies [1]. In addition, histological and behavioral analyses were performed to check for potential damage specifically using the setup and parameters used in this study. Single pulses were emitted at 0.03 Hz to mitigate cumulative bioeffects in and around the nerve. These parameters are summarized in Fig. 2(a). Parameter space exploration was done using 1) constant 1 ms pulses using the whole pressure range and 2) constant 24 MPa pressures using the whole pulse duration range.

Fig. 2.

(a) Diagram depicting the waveforms used to drive the FUS transducer in this study. (b) Hydrophone measurements of the FUS transducer’s pressure distribution. The full-width half-max (FWHM) is denoted by dotted lines.

D. Hydrophone measurements

Hydrophone measurements were conducted to characterize the FUS beam in free field degassed water. A fiber-optic hydrophone (HFO-690, Onda Corp, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was positioned on a 3D manipulator and the FUS transducer was held stationary. Lateral and axial beam profiles were achieved at 6.5 MPa, showing that the FUS focal size is 0.24 by 1.19 mm full width half maximum (FWHM) (Fig. 2(b)). Pressure curves were acquired by sweeping the whole input voltage range for 10 cycles (sufficient to ramp up to saturated pressure). A second capsule hydrophone (HLG-0200, Onda Corp, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used to characterize pressures under 5 MPa. The fiber optic curve was fit to the capsule hydrophone results to generate the whole pressure range.

E. Electromyography recordings

Electromyography was performed using two bi-polar needle electrodes (EL451; Biopac, Goleta, CA, USA) grounded to either the loose skin on the back of the neck, the table, or the tail. One electrode was placed 1 mm into the tibialis anterior and the other 1 mm into the gastrocnemius muscle. The head was fixed in a stereotaxic frame and the legs were immobilized to reduce movement artifacts in the EMGs. The mouse was then placed in a custom-built faraday cage to eliminate external noise sources from the recording electrodes. A two-second window surrounding the FUS trigger was recorded to capture any CMAP activation.

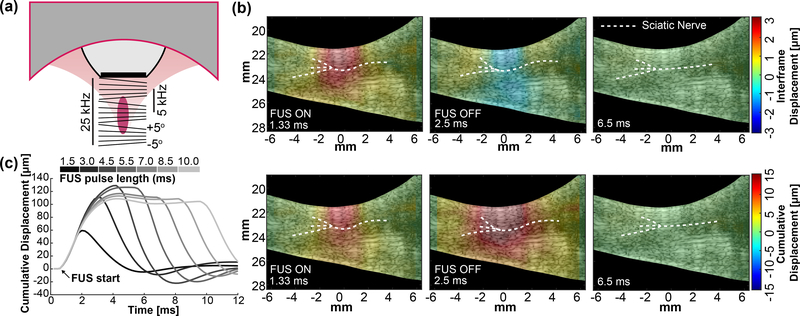

F. Displacement imaging

Displacement imaging was performed by synchronization of the FUS pulse and the imaging sequence (Fig. 3)(a). The imaging transducer sequence connected to the Verasonics triggered the function generator so that plane waves were sent 0.5 ms before to 0.5 ms after the FUS pulse. Five sequential plane wave transmits were tilted from −5° to +5° and summed up to produce a compounded image with higher SNR. After summation, the compounded frame rate was 5 kHz and this was used for imaging tissue movement before, during, and after FUS sonication. Notch filters were designed to remove FUS interference from the fundamental and sequential harmonics. Since the FUS pulse is 1 ms, having 5 angles allows 5 fully compounded frames for displacement estimation. Increasing the number of angles improves B-mode quality but decreases the amount of frames within the pulse, thus displacement quality is reduced. Angles less than 5° were found to be more susceptible to FUS interference.

Fig. 3.

(a) Diagram of the tilted imaging plane waves for simultaneous imaging and stimulation pulse sequences during displacement imaging. Total frame rate is on the left and compounded frame rate is on the right. (b) Output frame captures during displacement imaging for a 4 MPa (MI = 1.6) pulse.

(top) Interframe displacement shows tissue movement between compounded frames. (bottom) Cumulative displacement shows absolute tissue movement during the whole pulse. (c) Representative displacement traces over varying FUS pulse lengths (top bar).

After acquisition, delay-and-sum beamforming maps were calculated using the CUDA API for real-time processing on a GPU (Tesla K40, Nvidia, Santa Clara, CA, USA) [33]. The delay calculations were parallelized onto 3 grids of 1024 threads, specific to the GPU. 1D normalized cross-correlation [34] was performed on RF sampled at 4 points per wavelength and calculated also using GPU processing. Correlation window length of 9 λ and a 95% overlap provided adequate balance between processing speed and accuracy of displacement in real-time. Lastly, interframe displacement movies were generated and immediately displayed to visualize how FUS engages the nerve during each modulation event in ∼300 ms. Fig. 3(b) shows frame captures of interframe displacement and its summation (cumulative) over the course of one FUS sonication in the mouse leg during (1.33 ms), immediately after (2.5 ms), and long after FUS (6.5 ms). The FUS pulse was turned on at 1 ms and off at 2 ms. Characteristic displacement traces at the nerve for various pulse lengths can be seen in Fig. 3(c). The resolution of our displacement imaging technique is 96.25 microns, the wavelength of the imaging transducer [35]. In addition, regarding the displacement sensitivity, the Cramer-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) of the cross-correlation technique with our transducer specifications was calculated using the equation derived by Walker and Trahey [36]. The lower limit of the displacements we can measure for 1 dB signal-to-noise (SNR) and 0.5 correlation coefficient (experimentally obtained during 24 MPa FUS pulses) is 0.897 microns.

G. FUS targeting of the sciatic nerve

The FUS transducer was positioned using a 3D motorized positioner (Velmex, Bloomfield, NY, USA). Landmarks such as the femur and the trifurcation branching of the sciatic nerve into the sural, femoral, and tibial nerves were used as visual indicators of the location of the sciatic nerve. FUS at 1–5 MPa was used as a targeting pulse to gently perturb the nerve. Resultant tissue interframe displacement was estimated and displayed in real-time to validate placement of the FUS focus. Minor adjustments could then be made before the start of an experiment.

H. Experimental design

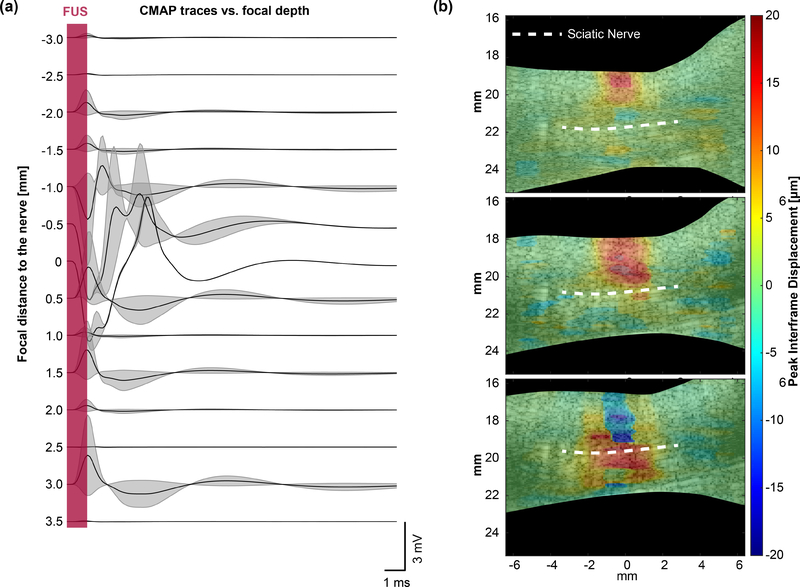

The method described above was used to measure the effect of radiation force on sciatic nerve activation in two separate experiments. The first experiment was performed to characterize typical nerve displacements and muscle activations over a wide parameter space. The CMAP waveform and nerve displacement from each sonication were recorded. A second experiment was conducted to determine whether displacement is a prerequisite for neuromodulation. The focus was placed at the top of the skin and rastered downwards past the sciatic nerve. Interframe displacement maps and CMAP amplitudes were measured for each pulse. Sonications that did not elicit muscle contraction are presented in Fig. 6(a), but they were excluded from CMAP amplitude vs pressure, duration, and interframe displacement analysis.

Fig. 6.

(a) Waterfall plot of example EMG traces acquired at increasing FUS focus depths with and without CMAP. The sciatic nerve (n = 2; 1 mouse) is placed at 0 mm. (b) Displacement maps showing interframe tissue displacement at subsequent focal depths corresponding to traces in (a). A 24 MPa (MI = 5.6), 1 ms ultrasound pulse was used to map the displacement at each depth.

I. Data analysis

Parameter space maps were generated by measuring average interframe nerve displacement using an ROI (1 mm x 0.5 mm) at the center of the focus and nerve. 50 displacement images per parameter (8 pressures x 10 PD parameters) per sciatic nerve (n = 6) were acquired. Displacements were excluded when higher sonication pressures created noise that could not be properly filtered. Parameter space maps were interpolated using a cubic spline interpolation.

All statistics were run using GraphPad Prism 7.04. For correlation experiments (CMAP energy vs interframe displacement), a non-parametric Spearman correlation was run to compute the R-value between interframe displacement measurements and CMAP energy. For gait analysis, a two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used to evaluate sciatic nerve function before and after sonications.

J. Histological analysis

A separate experiment in mice was conducted to demonstrate safety parameters of FUS (n = 6 nerves). Mice were anesthetized and 100 pulses of FUS at 0.2 Hz pulse repetition frequency (PRF) to the sciatic nerve in the same area was applied. Nerves received 1 of 5 experimental parameters and 1 sham sonication. Sonications were applied with a PRF of 0.2 Hz for 50 seconds using a subset of parameters where CMAPs were observed (22, 24, 26, 28, and 30 MPa; 1 ms pulse duration). Sciatic nerves were immediately dissected post-sacrifice and perfused with 4% PFA and 70% EtOH for 3 days before sectioning and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining. Red blood cell extravasation, degenerated myelin, cell apoptosis, inflammation and swelling, and protein degradation were used as indication of damage.

K. Safety assessment of FUS parameters

Temperature measurements of single 1 ms FUS stimulations at 22 MPa and 28 MPa were acquired using a needle thermocouple in heterogeneous chicken muscle to mimic muscle and nerve temperature. 2D raster scans were performed in both axial and lateral directions of the FUS beam. Temperature distributions of peak temperature rise show that temperature is spatially confined to twice the focal volume. A sharp 3-dB temperature decrease occurred at 0.4 mm away from the center of the focus laterally and 1.6 mm in depth. The temperature returned to baseline within 2 seconds after 1 ms stimulations [37], [38].

Functional safety was conducted using gait analysis (CatWalk XT; Nodulus, Utrecht, Netherlands) 1 day before, 1 day after, and 5 days after sonication (n = 10 male; 5 sham, 5 FUS). 10 FUS sonications and displacement imaging pulses (24 MPa, 1 ms, 30 s interstimulus interval) were applied to the left hind leg in anesthetized mice. Function of the sciatic nerve was analyzed using measurements of the sciatic function index (SFI), the max contact mean intensity of the left hind paw (values between 0–255) and the measured paw print length. SFI was calculated using [39]:

| (1) |

where PL is the print length, TS is the toe spread, ITS is the intermediate tow spread. Subscripts E and N indicate experimental and normal contralateral hind paws, respectively.

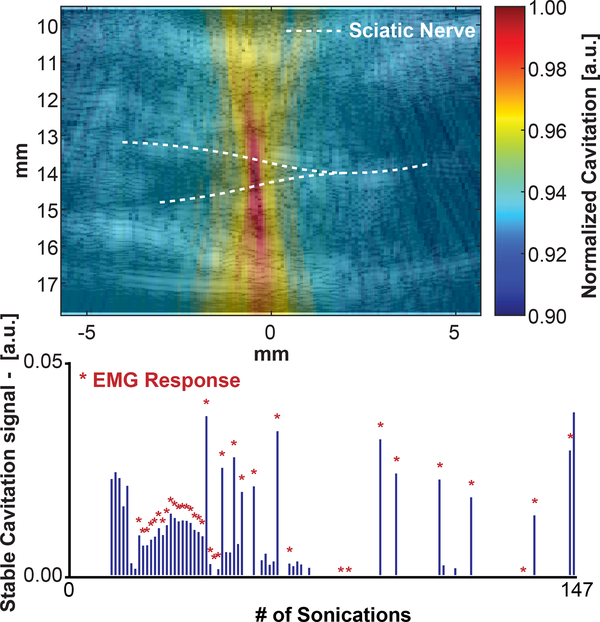

L. Preliminary cavitation Mapping

A separate follow-up experiment was conducted to examine if and where cavitation occurs using the parameters in experiment 2. The sciatic nerve was located as before, but the nerve experienced 147 pulses in the same position. Cavitation using cavitation mapping and CMAPs were recorded simultaneously. 147 sonications were applied to the nerve in the same location. The same system described above can be used to map cavitation without any additional hardware. Cavitation maps were generated using a receive-only (passive) acquisition scheme. The imaging transducer received passive emissions from the FUS transmission to form an image so that cavitation mapping occurs during the FUS pulse. The receive signals were temporally delayed based on the geometry of the transducer and the propagation times for each element (delay, sum, and integrate beamforming) [40]. Then the power cavitation image was log-compressed relative to the maximum pixel intensity. The cavitation signals that occurred during the 1 ms pulse duration were integrated to generate a single cavitation image. Acoustic cavitation emissions from stable cavitation were extracted by selecting for ultra-harmonic frequencies (relative to 4 MHz) within the bandwidth of the imaging transducer. The resultant cavitation image for stable cavitation was overlaid onto a B-mode image of the leg. An ROI of similar size to the focal beam was chosen to quantify cavitation for each FUS stimulation and the normalized intensity of the integrated signal was plotted for each of the 147 sonications.

III. Results

A. Displacement imaging can target and monitor nerves for neuromodulation

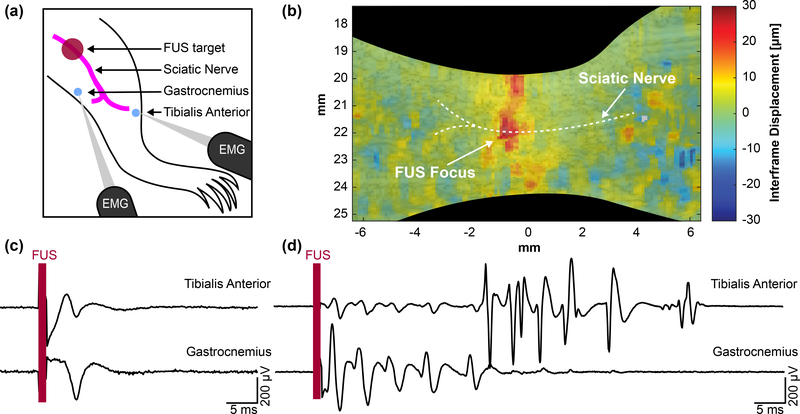

Using the technique developed for simultaneous modulation and imaging, we were able to visualize the FUS focus via displaced tissue at the sciatic nerve and measure corresponding CMAPs (Supplemental Video S1). Fig. 4 summarizes the targeting of the sciatic nerve and acquisition of both displacement and CMAP waveforms. FUS is initially applied upstream of EMG electrodes inserted in muscles innervated by the sciatic nerve (Fig 4(a)). Short pulses of 1 ms, 1 – 5 MPa peak positive FUS was delivered and simultaneously imaged to visualize wave propagation. Fig 4(b) shows maximum downward interframe displacement at the sciatic nerve, validating FUS positioning for subsequent experiments. Using higher pressure FUS (24 – 28 MPa), CMAPs can be elicited using similar 1 ms pulses (Supplemental Video S2). Fig 4(c) and 4(d) show representative EMG traces in both muscle groups. A majority of FUS-evoked events result in a single muscle contraction (Fig 4(c)). However, multiple muscle contractions, such as the ones shown in Fig 4(d), were also observed from a single pulse.

Fig. 4.

(a) Diagram showing mouse leg topology and relative locations of the stimulation and recording sites. (b) Displacement imaging validates focal position onto the sciatic nerve and a region of interest can be taken to acquire average interframe nerve displacement at the focus. A 28 MPa (MI = 6.5), 1 ms pulse was used to map the displacement. (c) Example traces showing single CMAPs from a single FUS stimulus. (d) Example traces of multiple CMAPs from a single FUS stimulus.

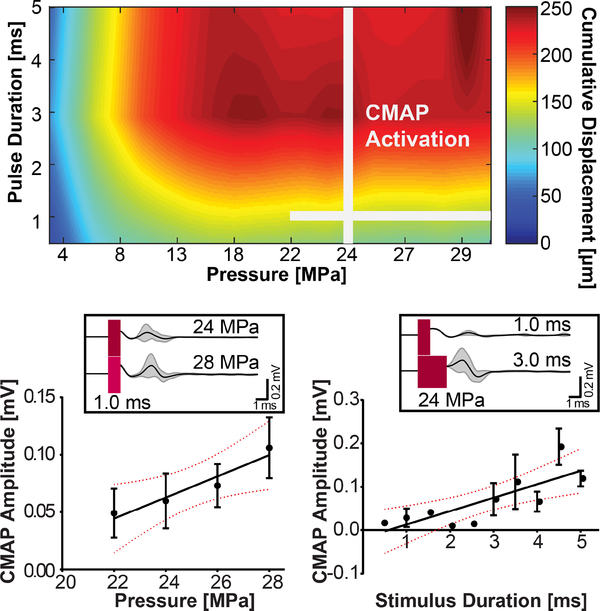

The amount of displacement at the nerve over both acoustic pressure and pulse duration parameters were recorded. Fig 5 shows a parameter space map summarizing typical cumulative displacement amplitudes found in the leg. The parameters where CMAPs were observed are indicated by two perpendicular lines. CMAPs are observed for higher pressures but over the whole pulse duration sweep. Higher pressures are stronger indicators of activation than the length of the pulse duration. Only single muscle activation events by FUS were used in this analysis. By holding pulse duration constant at 1 ms, increases in pressure seem to linearly increase the amplitude of responses (R2 = 0.9255, p = 0.038). CMAP probability for these parameters are summarized in table I. Cumulative nerve displacement at this pressure range varied from 140 to 180 μm. By holding pressure constant (24 MPa), increases in pulse duration also linearly increased corresponding CMAP amplitudes (R2 = 0.6361, p = 0.0057). Example traces shown in Fig. 5 subplots show average waveform changes in muscle activation. As pulse duration increases, the electrical interference artifact starts to impede proper EMG analysis. Thus, pulses longer than 5 ms were not included in the EMG analysis despite their success in generating spiking activity (see Appendix B).

Fig. 5.

(top) Parameter space map of average cumulative nerve displacement over pulse duration and pressure. FUS parameters that induced CMAPs observed in this study are marked by the white lines. (bottom) Average CMAP amplitude over pressure and duration sweeps. Subplots show representative EMG traces.

TABLE I.

Probability of success for CMAP activation over pressure and pulse duration.

| Pressure [MPa] | probability [%] |

| 22 | 8 |

| 24 | 8 |

| 26 | 44 |

| 28 | 40 |

| PD [ms] | probability [%] |

| 0.5 | 4 |

| 1.0 | 10 |

| 1.5 | 4 |

| 2.0 | 2 |

| 2.5 | 6 |

| 3.0 | 12 |

| 3.5 | 14 |

| 4.0 | 18 |

| 4.5 | 26 |

| 5.0 | 28 |

B. CMAP activity from mouse sciatic nerve is associated with acoustic radiation force

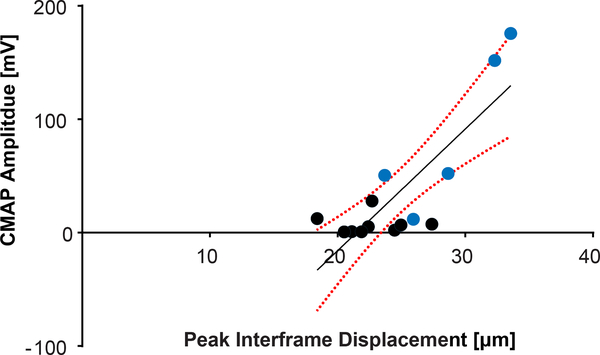

To determine if there is a correlation between CMAP and tissue displacement, we varied the FUS focal position to achieve varying degrees of nerve displacement. The FUS focus was moved from the upper region (starting at the skin) to the bottom of the mouse leg (n = 4) in the supine position, covering a distance of approximately 7 mm. Nerve displacements were measured using a region-of-interest (ROI) surrounding the nerve over the focal depth (Fig. 6(a)). The location of the nerve (denoted as 0 mm) was 3.5 mm below the surface of the skin. CMAP activations were elicited within ± 1 mm around the sciatic nerve, coincident with the FUS focal spot size, with a probability of 30% ± 20%. The step size was chosen to overlap with half the FUS FWHM focal area so that the nerve was subjected to maximum pressure. Displacement maps corroborate the focus position at each depth and nerve displacement measurements were recorded (Fig. 6(b)). Measurements of 29.1 μm (± 0.5 μm, STD) to 34.4 μm (± 0.2 μm, STD) of peak interframe displacement were shown to elicit CMAP activity. Furthermore, the EMG amplitude and the peak interframe displacement of the nerve incurred during modulation were found to be well correlated (R2 = 0.6791, p = 0.0094, (Fig. 7)). The lowest interframe nerve displacement required for an elicited CMAP amplitude was 18.7 μm while the probability of successful activation proportionally increased with the total nerve displacement.

Fig. 7.

Spearman correlation of evoked CMAP amplitude vs. average interframe nerve displacements, acquired from varying focal depths (p = 0.0094; R2 = 0.6791) with 95% confidence intervals. Blue points indicate traces that were recorded within ±1 mm of the nerve. A 24 MPa (MI = 5.6), 1 ms ultrasound pulse was used to induce nerve displacements.

IV. Discussion

This study sought to devise a method that could not only validate FUS targeting, but also provide mechanistic insight into the underpinnings of peripheral neuromodulation. The results show that high frame-rate displacement tracking during short FUS pulses can visualize focal displacements in the mouse leg. Using this technique we show that through radiation force parametric space exploration, i.e., varying both pulse duration and pressure, there is a clear correlation with CMAP amplitude. Lastly, we report that nerves experiencing interframe displacements above 18 μm were more likely to result in CMAP generation. The amplitude of CMAPs increasing with nerve displacements provides evidence towards the hypothesis that ultrasound neuromodulation is driven by nerve deflection as a result of the highly focused acoustic radiation force. Therefore, the results show that this method is an essential tool for informed targeting and mechanistic monitoring of FUS neuromodulation. This technique could prevent off-target effects and raise confidence in future FUS neuromodulation studies in nerves and even the brain.

Micron-sized displacements using high frame-rate compounded plane wave imaging before, during, and after FUS excitation pulses could be displayed back in real-time for in-procedure adjustments. The sensitivity of our technique to noninvasively image and localize minute displacements (< 5 μm at 3 MPa within 1 ms) in vivo provides unique capability of real-time monitoring of both the mechanism and successful FUS targeting and modulation at safe acoustic levels. Since the beam being imaged is the same as the stimulation FUS, the same potential effects on wave propagation such as aberration, interference, attenuation, and/or scattering can also be monitored. Moreover, the CMAP amplitudes in our study being similar to those found in our previous work[1] without image pulses indicates that using an imaging pulse during the FUS does not effect neuromodulation output. Therefore, monitoring with mechanical imaging constitutes a critical safety tool for mitigating unintentional modulation in surrounding tissue regions (e.g., blood vessels or tendons) while focusing in the intended region and optimizing the required acoustic intensity for neuromodulation. Other methods for displacement imaging during neuromodulation often require longer ultrasound pulses to engage tissues at detectable displacement ranges [31], [32]. Not only was this technique demonstrated as an effective metric for noninvasive FUS targeting in vivo, but it was also capable of drawing specific conclusions about CMAP activation. For example, acoustic pressure seems to influence CMAP probability more than pulse duration. Using the technique, we showed that longer pulse durations plateaued the amount of displacement during the pulse. This saturation may explain why increases in pressure affected CMAPs more than pulse durations.

Sciatic nerves were chosen because they are mixed nerve bundles with both sensory and motor fibers. Though sensory activation is more relevant to neuromodulatory therapeutics, having motor neurons allows sensory activation in mice to be interpreted through CMAP recordings in EMG. Since increased CMAP amplitudes are a result of increased recruitment of nerve fibers, correlations show that increased deflection of the nerve may contribute to more motor nerve recruitment. Moreover, due to motor nerves responding to mV level voltages, the high pressures used in this study may be necessary to mediate mechanotransduction of the nerve to these levels. As a result, our implementation provides the unique capability of using the actual FUS neurostimulation pulse to qualitatively target and monitor nerve engagement during sonication.

FUS-induced excitation has been observed in brain circuits [2], [12], [13], [41], [42] and nerves [1], [15], [20], [43]. However, equally as many reports of inhibitory effects have also been published [18], [19], [44], [45]. Similarly, neuromodulation has been achieved using pulsed ultrasound, but also with continuous wave and increases in acoustic intensity can both increase or not decrease action potential probability [46]. This disagreement between observations, especially in vivo, may be a result of inaccurate and/or blind targeting without feedback that FUS was delivered correctly. Our findings demonstrate the utility of imaging the radiation force generated during FUS stimulation of the peripheral nerves as a method for visualizing FUS propagation during the whole neuromodulation sequence. Using the same pulse, we were able to stimulate nerves in mice and relay information, in real-time, regarding the breadth and locality of tissue engagement by FUS. Moreover, our technique is supported by findings in two studies hypothesizing that the mechanism includes acoustic radiation forces [11], [47].

Our results show that increased nerve deflection may induce higher levels of nerve recruitment and increases in deflection can be mediated through increases in both FUS pressure and duration. We employed a 1 ms and 24 MPa FUS stimulus as a base parameter to limit thermal effects from ultrasound but also increase the likelihood of CMAP activation. The range of pressures and pulse durations used in this study were based upon previous findings from a prior study [1] where it was shown that for short durations, higher pressure FUS bursts increased stimulation success. Our current study employs a 4 MHz transducer with a 1.19 × 0.24 mm focal size, which may explain the need for higher pressures to achieve the same stimulation success. Increases in pressure engages additional volumes of tissue, thus raising the probability of modulating the nerve, which may compensate for targeting precision, especially out-of-plane positioning (elevation direction) with such a small focus. Our future studies will test whether focal volume changes (i.e., larger f-number), driven at the same frequency, changes stimulation success. Nevertheless, in the current manuscript we explored an unprecedented spatial specificity (0.2 mm versus several mm, i.e. above 1 mm [13], [44], [48]) and reached targeting accuracy far beyond previous studies, as no targeting confirmation were reported previously.

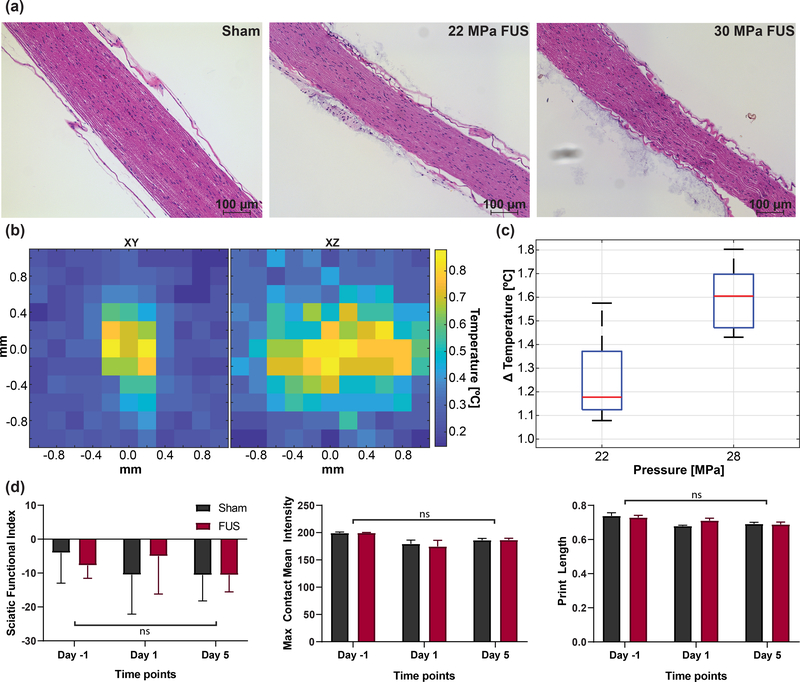

The parametric study revealed that CMAPs were observed at the whole range of pulse durations given a sufficiently high pressure. This may indicate that the physical stretch of the nerve from FUS may trigger CMAP events, especially given evidence of established links between mechanical forces and neural function and activity [47], [49]–[51]. Regarding the safety of our technique, H&E stains in Fig. 8(a) show that sonications at all parameters explored in the study appear safe and do not show apparent damage compared to sham sonications. There is no red blood cell extravasation or myelin disruption characteristic of damage to the sciatic nerve. Regarding the temperature elevations from parameters used in the current study, we did not observe a significant increase in the local temperature generated. Using a needle thermocouple in ex vivo chicken breast, we measured the temperature elevation of the parameters used in this study (Fig. 8(b–c)). 2D temperature maps show the spatial temperature elevation around the FUS focus. The maximum local temperature measured was 1.6°C (± 0.1°C, STD) and 1.3°C (± 0.2°C, STD) at the highest and lowest parameters, respectively. Although temperatures returned to baseline at most 2 seconds after the stimulus, the interstimulus interval between FUS application in this study was set to 30 seconds to prevent the accumulation of heat. Previous studies have shown that a 3.8–6.4°C minimum temperature change is required to thermally activate HEK cells and rat sciatic nerve using infrared optical stimulation [52], [53], or a 3°C increase from low-pressure FUS can activate posterior tibial nerve [54]. Though it remains unknown what FUS parameters lead to nerve activation as opposed to CMAP spiking, the low temperature induced by FUS in this study is unlikely to generate nerve activation. Since our in vivo studies have tissue blood perfusion, estimates in chicken muscle are overestimations of thermal effects. To further validate the safety of our technique, gait analysis was conducted using the CatWalk XT program to analyze left hind limbs of mice undergoing FUS (n = 5) and sham (n = 5) sonications. Trials were acquired −1, 1, and 5 days from FUS sonication, where 10 stimulations were applied to the hind limb of each anesthetized mouse (24 MPa, 1 ms, 30 s interstimulus interval). A two-way ANOVA (Fig. 8(d)) shows no significant difference in the sciatic functional index (SFI) (p = 0.4491), the max contact mean pixel intensity (p = 0.8841), and the print length (p = 0.2442) between sham and FUS mice. A test for multiple comparisons shows that there is a significant difference in day −1 and day 1 in the max contact mean intensity in FUS mice (p = 0.0153), which also occurred between day −1 and days 1 and 5 in sham mice. These differences may be a result of anesthetizing and shaving only the left hind limb on day 0. Moreover, the SFI across all time points (used for measuring the direct function of the sciatic nerve) was comparable to SFI values in normal, healthy populations (−4.3 ± 17.3) [55], indicating that our FUS sonications did not functionally impair mice sciatic nerves.

Fig. 8.

(a) Histological H&E staining for 100 pulses of sham ultrasound, 22 MPa, and 30 MPa at the same spot with a PRF of 0.3 Hz. (b) 2D Temperature heatmaps showing spatial temperature changes from a single pulse of FUS. (c) Boxplots showing ΔT for the lowest and highest pressures used in this study. (d) Results from gait analysis −1, 1, and 5 days from FUS sonication (10 sonications, 24 MPa, 1 ms) on the left hind limb (n = 10; 5 FUS, 5 sham). Statistical analysis, conducted using a two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons, show no significant interactions for the SFI (p = 0.4491), left hind limb max contact mean intensity (p = 0.8841), and left hind limb print length (p = 0.2442).

A. Limitations

The main difference between this technique and current ARFI, MR-ARFI, and shear wave techniques is the ability to image and measure transient displacement during FUS delivery (< 1 ms) whereas all other techniques image after the application of radiation force or have temporal resolutions inadequate for these fast pulses. However, our technique is limited to regimes where there is considerable absorption of acoustic radiation force. Low FUS pressure levels without detectable displacements (< 0.8 μm) cannot be accurately mapped using this method, while higher FUS pressure levels above acoustic cavitation thresholds often introduce difficulties in filtering interference, corrupting displacement measurements. Additionally, depths, where ultrasound at the imaging transducer frequencies have poor penetration, are subjected to noisy displacements, but techniques such as coded excitation can be employed in future studies to improve focusing and avoid standing wave formation [17]. Moreover, the mechanistic investigation of FUS neuromodulation in the PNS provides the additional benefits over studies on the CNS by avoiding artifacts such as indirect activation of the auditory pathway through shear mode conversion in the skull [56], [57].

However, regarding the high pressures used for motor excitation, we cannot discount other effects at the pressure levels and pulse durations employed herein such as thermal effects and acoustic cavitation since previous studies have reported on those effects as possible mechanisms of action potential generation [43], [52], [58], [59]. It is known that cavitation thresholds increase with frequency [60], but also lower F-numbers can decrease cavitation probability [61]. To determine the dependence of neuromodulation on acoustic cavitation, passive cavitation imaging methods [40], [62] may prove useful to detect and localize acoustic cavitation activity during FUS application. Our preliminary findings indicate the presence of cavitation exists using the FUS parameters in experiment 2.

Seemingly contradictory reports of ultrasound neuromodulatory effects may be potentiated by a combination of radiation force [11], cavitation[20], or temperature [63]. In the present study, we cannot fully decouple cavitation from radiation force. Our findings, using passive cavitation mapping, can be summarized in Fig. 9. The irregular pattern of cavitation events is similar to what Li et al. 2014 reported using 1.1 MHz and 1ms over 60 pulses at 5 MPa [64]. Over 147 sonications, 36 sonications had coincident cavitation activity and observable CMAP recordings. Some sonications that cavitation was observed did not elicit a CMAP. Interestingly, 3 CMAP recordings did not have cavitation recorded at the nerve. While cavitation is not detected for some muscle activations, the radiation force exerted on the nerve was present every sonication. This may indicate that even though cavitation may play a role in neuromodulation, it may not be necessary for activation and may be driven more significantly by the acoustic force. Nonetheless, the influence of cavitation at our pulse parameters is a limitation, warranting a full study dedicated to characterizing its role in neuromodulation. However, this is nothing less than exciting; FUS is uniquely positioned as a potential neuromodulation technology where various combinations of radiation force, cavitation, and temperature may be employed to achieve a variety of therapeutic effects. Therefore, future studies will be geared towards additional characterization of the observed bioeffects to further develop and understand ultrasound neuromodulation.

Fig. 9.

(top) Preliminary evidence of the contribution of cavitation, mapped using the same proposed setup for neuromodulation. (bottom) Measured cavitation at the sciatic nerve over a single trial (147 sonications); asterisks denote evoked responses.

V. Conclusion

Displacement-based nerve imaging was developed to noninvasively target and monitor neuromodulation of mouse motor nerves in vivo. Micron-sized displacements were mapped in the nerve and surrounding regions and the correlation between displacement and activation amplitude provides evidence towards the contribution of acoustic radiation force for activating nerves. However, it is difficult to conclude that displacement is the main driving force behind neuromodulation. Thus, the system developed in this study can perform cavitation mapping for the same FUS pulse without additional hardware and future studies will take cavitation into careful consideration. Nonetheless, displacement amplitude thresholds for successful FUS modulation may provide an important metric for consistent and reproducible FUS modulation at safe acoustic levels; mainly, knowing FUS was delivered properly will generate confidence in future FUS neuromodulation studies. Finally, towards novel therapeutics for pain, our technique may provide important objective measurements for evaluation and efficacy of these treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Maria F. Murillo for her help in running behavior, Matthew Downs Ph.D., Iason Apostolakis Ph.D., Yang Han Ph.D., Min Gon Kim Ph.D., Niloufar Saharkhiz M.S., Nancy Kwon M.S., and Diana Kim, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, and the team at SoundStim for their helpful technical discussions in progressing this study.

This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office (BTO) Electrical Prescriptions (ElectRx) (Grant/Contract No. DARPA HR0011-15-2-0054).

Appendix A

DERATED PRESSURE IN THE MOUSE LEG

All pressures reported in this study are derated for attenuation in muscle tissue using the following equation [65], [66]:

| (2) |

where α0 is 3.3 dBcm−1MHz−1 through skeletal muscle (3 mm mouse), and f is the center frequency of the FUS in MHz. The peak negative pressures used in this study range up to 13 MPa in mice.

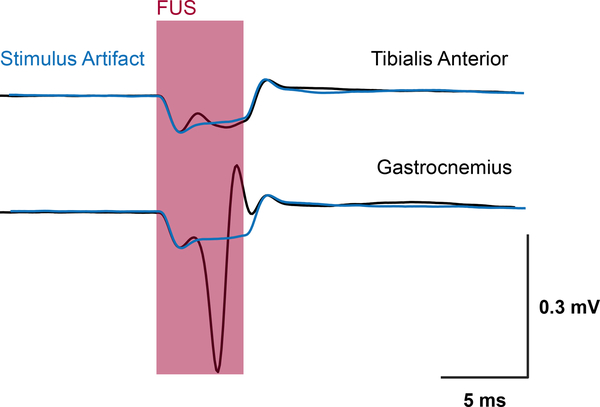

Appendix B

FUS EMG ARTIFACT

Pulse durations up to 5 ms which is about 67% longer than the pulse duration that caused a plateau in displacement at 3 ms (Fig. 10). Pulses longer than 3 ms were found to corrupt the EMG signal since the artifact from FUS stimulation overlaps with the CMAP trace. Therefore, longer pulse durations were unnecessary and were excluded from analysis in this study.

Fig. 10.

Example of EMG artifact corruption in pulses 5 ms and longer in both EMG traces. FUS sonication is indicated by the shaded region and the artifact is overlaid in blue.

Contributor Information

Stephen A. Lee, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, 10032 USA.

Hermes A. S. Kamimura, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, 10032 USA.

Mark T. Burgess, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, 10032 USA.

Elisa E. Konofagou, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Radiology, Columbia University, New York, NY, 10032 USA.

References

- [1].Downs ME, Lee SA, Yang G, Kim S, Wang Q, and Konofagou EE, “Non-invasive peripheral nerve stimulation via focused ultrasound in vivo,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 63, no. 3, p. 035011, January 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tufail Y, Matyushov A, Baldwin N, Tauchmann ML, Georges J, Yoshihiro A, Tillery SI, and Tyler WJ, “Transcranial Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulates Intact Brain Circuits,” Neuron, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 681–694, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harvey EN, “the Effect of High Frequency Sound Waves on Heart Muscle and Other Irritable Tissues,” Am. J. Physiol. Content, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 284–290, February 1929. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fry WJ, Wulff VJ, Tucker D, and Fry FJ, “Physical Factors Involved in Ultrasonically Induced Changes in Living Systems: I. Identification of NonTemperature Effects,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 867–876, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fry WJ, Mosberg WH, Barnard JW, and Fry FJ, “Production of Focal Destructive Lesions in the Central Nervous System With Ultrasound,” J. Neurosurg, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 471–478, September 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cotero V, Fan Y, Tsaava T, Kressel AM, Hancu I, Fitzgerald P, Wallace K, Kaanumalle S, Graf J, Rigby W, Kao TJ, Roberts J, Bhushan C, Joel S, Coleman TR, Zanos S, Tracey KJ, Ashe J, Chavan SS, and Puleo C, “Noninvasive sub-organ ultrasound stimulation for targeted neuromodulation,” Nat. Commun, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 952, March 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zachs DP, Offutt SJ, Graham RS, Kim Y, Mueller J, Auger JL, Schuldt NJ, Kaiser CR, Heiller AP, Dutta R, Guo H, Alford JK, Binstadt BA, and Lim HH, “Noninvasive ultrasound stimulation of the spleen to treat inflammatory arthritis,” Nat. Commun, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 951, December 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tyler WJ, Tufail Y, Finsterwald M, Tauchmann ML, Olson EJ, and Majestic C, “Remote excitation of neuronal circuits using low-intensity, low-frequency ultrasound,” PLoS One, vol. 3, no. 10, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Legon W, Sato TF, Opitz A, Mueller J, Barbour A, Williams A, and Tyler WJ, “Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates the activity of primary somatosensory cortex in humans,” Nat. Neurosci, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 322–329, January 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Menz MD, Oralkan O, Khuri-Yakub PT, and Baccus SA, “Precise Neural Stimulation in the Retina Using Focused Ultrasound,” J. Neurosci, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 4550–4560, March 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Menz MD, Ye P, Firouzi K, Nikoozadeh A, Butts Pauly K, Khuri-Yakub P, and Baccus SA, “Radiation force as a physical mechanism for ultrasonic neurostimulation of the ex vivo retina,” J. Neurosci, pp. 2394–18, June 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lee W, Lee SD, Park MY, Foley L, Purcell-Estabrook E, Kim H, Fischer K, Maeng LS, and Yoo SS, “Image-Guided Focused Ultrasound-Mediated Regional Brain Stimulation in Sheep,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 459–470, February 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].King RL, Brown JR, Newsome WT, and Pauly KB, “Effective parameters for ultrasound-induced in vivo neurostimulation,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 312–331, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kubanek J, Shi J, Marsh J, Chen D, Deng C, and Cui J, “Ultrasound modulates ion channel currents,” Sci. Rep, vol. 6, p. 24170, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dickey TC, Tych R, Kliot M, Loeser JD, Pederson K, and Mourad PD, “Intense Focused Ultrasound Can Reliably Induce Sensations in Human Test Subjects in a Manner Correlated With the Density of Their Mechanoreceptors,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 85–90, January 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang PF, Phipps MA, Newton AT, Chaplin V, Gore JC, Caskey CF, and Chen LM, “Neuromodulation of sensory networks in monkey brain by focused ultrasound with MRI guidance and detection,” Sci. Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, December 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kamimura HA, Wang S, Wu SY, Karakatsani ME, Acosta C, Carneiro AA, and Konofagou EE, “Chirp- and random-based coded ultrasonic excitation for localized blood-brain barrier opening,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 60, no. 19, pp. 7695–7712, September 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lele PP, “Effects of focused ultrasonic radiation on peripheral nerve, with observations on local heating,” Exp. Neurol, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 47–83, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tsui PH, Wang SH, and Huang CC, “In vitro effects of ultrasound with different energies on the conduction properties of neural tissue,” Ultrasonics, vol. 43, no. 7, pp. 560–565, June 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wright CJ, Haqshenas SR, Rothwell J, and Saffari N, “Unmyelinated Peripheral Nerves Can Be Stimulated inVitro Using Pulsed Ultrasound,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 2269–2283, October 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dahl JJ, Pinton GF, Palmeri ML, Agrawal V, Nightingale KR, and Trahey GE, “A parallel tracking method for acoustic radiation force impulse imaging,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 301–311, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Palmeri ML and Nightingale KR, “On the thermal effects associated with radiation force imaging of soft tissue,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 551–565, May 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nightingale K, Bentley R, and Trahey G, “Observations of tissue response to acoustic radiation force: Opportunities for imaging,” Ultrason. Imaging, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 129–138, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen S, Urban MW, Pislaru C, Kinnick R, Zheng Y, Yao A, and Greenleaf JF, “Shearwave dispersion ultrasound vibrometry (SDUV) for measuring tissue elasticity and viscosity,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 55–62, January 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jeong JS, Cannata JM, and Shung KK, “Optimal suppression of therapeutic interference for real-time therapy and imaging with an integrated hifu/imaging transducer,” in 2010 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, Oct 2010, pp. 2243–2246. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sarvazyan AP, Rudenko OV, Swanson SD, Fowlkes JB, and Emelianov SY, “Shear wave elasticity imaging: a new ultrasonic technology of medical diagnostics,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 1419–1435, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Konofagou EE, Maleke C, and Vappou J, “Harmonic Motion Imaging (HMI) for Tumor Imaging and Treatment Monitoring,” Curr. Med. Imaging Rev, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 16–26, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bour P, Marquet F, Ozenne V, Toupin S, Dumont E, Aubry JF, Lepetit-Coiffe M, and Quesson B, “Real-time monitoring of tissue displacement and temperature changes during MR-guided high intensity focused ultrasound,” Magn. Reson. Med, vol. 78, no. 5, pp. 1911–1921, November 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McDannold N and Maier SE, “Magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging,” Med. Phys, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 3748–3758, July 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kaye EA, Chen J, and Pauly KB, “Rapid MR-ARFI method for focal spot localization during focused ultrasound therapy,” Magn. Reson. Med, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 738–743, March 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ozenne V, Constans C, Bour P, Santin MD, Valabregue R, Ah-` nine H, Pouget P, Lehericy S, Aubry J-F, and Quesson B, “Mri moni-´ toring of temperature and displacement for transcranial focus ultrasound applications,” NeuroImage, vol. 204, p. 116236, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Phipps MA, Jonathan SV, Yang PF, Chaplin V, Chen LM, Grissom WA, and Caskey CF, “Considerations for ultrasound exposure during transcranial MR acoustic radiation force imaging,” Sci. Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, December 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yiu BYS, Tsang IKH, and Yu ACH, “GPU-based beamformer: Fast realization of plane wave compounding and synthetic aperture imaging,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 58, no. 8, pp. 1698–1705, August 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Luo J and Konofagou E, “A fast normalized cross-correlation calculation method for motion estimation,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1347–57, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Righetti R, Ophir J, and Ktonas P, “Axial resolution in elastography,” Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 101–113, January 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Walker WF and Trahey GE, “A fundamental limit on delay estimation using partially correlated speckle signals,” IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 301–308, March 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tiennot T, Kamimura HA, Lee SA, Aurup C, and Konofagou EE, “Numerical modeling of ultrasound heating for the correction of viscous heating artifacts in soft tissue temperature measurements,” Appl. Phys. Lett, vol. 114, no. 20, p. 203702, May 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kamimura HAS, Aurup C, Bendau E, Saharkhiz N, Kim MG, and Konofagou EE, “Iterative curve fitting of the bioheat transfer equation for thermocouple-based temperature estimation in vitro and in vivo,” IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, pp. 1–1, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Inserra MM, Bloch DA, and Terris DJ, “Functional indices for sciatic, peroneal, and posterior tibial nerve lesions in the mouse,” Microsurgery, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 119–124, January 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Haworth KJ, Bader KB, Rich KT, Holland CK, and Mast TD, “Quantitative Frequency-Domain Passive Cavitation Imaging,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 177–191, January 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Younan Y, Deffieux T, Larrat B, Fink M, Tanter M, and Aubry JF, “Influence of the pressure field distribution in transcranial ultrasonic neurostimulation,” Med. Phys, vol. 40, no. 8, p. 082902, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tufail Y, Yoshihiro A, Pati S, Li MM, and Tyler WJ, “Ultrasonic neuromodulation by brain stimulation with transcranial ultrasound,” Nat. Protoc, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 1453–1470, September 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wright CJ, Rothwell J, and Saffari N, “Ultrasonic stimulation of peripheral nervous tissue: An investigation into mechanisms,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser, vol. 581, no. 1, p. 012003, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Colucci V, Strichartz G, Jolesz F, Vykhodtseva N, and Hynynen K, “Focused Ultrasound Effects on Nerve Action Potential in vitro,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 1737–1747, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dallapiazza RF, Timbie KF, Holmberg S, Gatesman J, Lopes MB, Price RJ, Miller GW, and Elias WJ, “Noninvasive neuromodulation and thalamic mapping with low-intensity focused ultrasound,” J. Neurosurg, pp. 1–10, April 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blackmore J, Shrivastava S, Sallet J, Butler CR, and Cleveland RO, “Ultrasound neuromodulation: A review of results, mechanisms and safety,” Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology, vol. 45, no. 7, pp. 1509–1536, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mihran RT, Barnes FS, and Wachtel H, “Temporally-specific modification of myelinated axon excitability in vitro following a single ultrasound pulse,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 297–309, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mehic E, Xu JM, Caler CJ, Coulson NK, Moritz CT, and´ Mourad PD, “Increased anatomical specificity of neuromodulation via modulated focused ultrasound,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 2, February 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].El Hady A and Machta BB, “Mechanical surface waves accompany action potential propagation,” Nat. Commun, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 6697, December 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kerstein PC, Nichol RH, and Gomez TM, “Mechanochemical regulation of growth cone motility,” p. 244, July 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gaub BM, Kasuba KC, Mace E, Strittmatter T, Laskowski PR, Geissler SA, Hierlemann A, Fussenegger M, Roska B, and Muller DJ, “Neurons differentiate magnitude and location of mechanical¨ stimuli,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, vol. 117, no. 2, pp. 848–856, January 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Shapiro MG, Homma K, Villarreal S, Richter C-P, and Bezanilla F, “Infrared light excites cells by changing their electrical capacitance,” Nat. Commun, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 736, January 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wells J, Kao C, Konrad P, Milner T, Kim J, Mahadevan-Jansen A, and Jansen ED, “Biophysical mechanisms of transient optical stimulation of peripheral nerve,” Biophys. J, vol. 93, no. 7, pp. 2567–2580, October 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Casella DP, Dudley AG, Clayton DB, Pope IV JC, Tanaka ST, Thomas J, Adams MC, Brock III JW, and Caskey CF, “Modulation of the rat micturition reflex with transcutaneous ultrasound,” Neurourology and urodynamics, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 1996–2002, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yao M, Inserra MM, Duh MJ, and Terris DJ, “A longitudinal, functional study of peripheral nerve recovery in the mouse,” Laryngoscope, vol. 108, no. 8, pp. 1141–1145, August 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sato T, Shapiro MG, and Tsao DY, “Ultrasonic Neuromodulation Causes Widespread Cortical Activation via an Indirect Auditory Mechanism,” Neuron, vol. 98, no. 5, pp. 1031–1041.e5, June 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Guo H, Hamilton M, Offutt SJ, Gloeckner CD, Li T, Kim Y, Legon W, Alford JK, and Lim HH, “Erratum: Ultrasound Produces Extensive Brain Activation via a Cochlear Pathway (Neuron (2018) 98(5) (10201030.e4), (S0896627318303714) ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.036)),” Neuron, vol. 99, no. 4, p. 866, June 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Plaksin M, Kimmel E, and Shoham S, “Cell-Type-Selective Effects of Intramembrane Cavitation as a Unifying Theoretical Framework for Ultrasonic Neuromodulation,” eNeuro, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. ENEURO.0136–15.2016, June 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Plaksin M, Shoham S, and Kimmel E, “Intramembrane cavitation as a predictive bio-piezoelectric mechanism for ultrasonic brain stimulation,” Phys. Rev. X, vol. 4, no. 1, July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sponer J, “Dependence of the cavitation threshold on the ultrasonic frequency,” Czechoslov. J. Phys, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 1123–1132, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Khokhlova T, Rosnitskiy P, Hunter C, Maxwell A, Kreider W, ter Haar G, Costa M, Sapozhnikov O, and Khokhlova V, “Dependence of inertial cavitation induced by high intensity focused ultrasound on transducer F -number and nonlinear waveform distortion,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 144, no. 3, pp. 1160–1169, September 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Burgess MT, Apostolakis I, and Konofagou E, “Passive microbubble imaging with short pulses of focused ultrasound and absolute time-of-flight information,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 141, no. 5, pp. 3491–3491, May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Darrow DP, O’Brien P, Richner TJ, Netoff TI, and Ebbini ES, “Reversible neuroinhibition by focused ultrasound is mediated by a thermal mechanism,” Brain Stimul, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1439–1447, November 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Li T, Chen H, Khokhlova T, Wang Y-N, Kreider W, He X, and Hwang JH, “Passive cavitation detection during pulsed hifu exposures of ex vivo tissues and in vivo mouse pancreatic tumors,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 1523–1534, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Goss S, Frizzell L, and Dunn F, “Ultrasonic absorption and attenuation in mammalian tissues,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 181–186, January 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Cobbold RS, Foundations of biomedical ultrasound. Oxford university press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.