Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 outbreak, cardiovascular imaging, especially transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE), may expose healthcare personnel to virus contamination and should be performed only if strictly necessary. On the other hand, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and TOE represent the first-line imaging exams for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis (IE). To date, this is the first case of COVID-19 complicated by IE.

Case summary

We present the case of a 57-year-old man with severe COVID-19 pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation. During the intensive care unit (ICU) stay, he developed fever and positive haemocoltures for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. TTE did not identify endocardial vegetations. TOE was then performed and outlined IE of the aortic valve on the non-coronary cusp. Antibiotic therapy was given with progressive resolution of the septic state and improvement of inflammatory signs. After 30 days of ICU stay, the patient was transferred to the Sub-ICU and then to a rehabilitation hospital. A close follow-up has been scheduled: after full recovery, a new echocardiography will be performed (TTE and TOE, if the former is non-conclusive) to consider surgical valve repair in the case of persistence/progression of the valvular lesion or deterioration of the valve function.

Discussion

In COVID-19 patients, echocardiography remains the leading imaging exam for the diagnosis of IE. If the suspicion of IE is high, even in this setting of patients, TTE or TOE (if TTE is non-conclusive) are mandatory. A high degree of attention must be paid and appropriate preventive measures taken to avoid contamination of healthcare personnel.

Keywords: Infective endocarditis, Transoesophageal echocardiography, COVID-19, Case report

Learning points

Echocardiography (transthoracic and transoesophageal) is mandatory for the diagnosis of IE also in COVID-19 patients.

In COVID-19 patients, the clinical course in the intensive care unit can be worsened by other infective complications, leading eventually to further impairment of health status and prognosis.

Echocardiography in COVID-19 must be carefully performed with appropriate preventive measures to avoid contamination of healthcare personnel.

Introduction

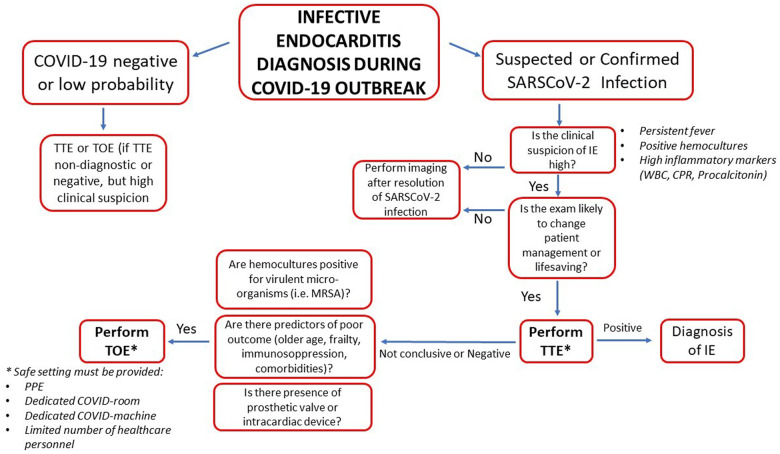

Concern is growing for the contamination risk of healthcare personnel performing diagnostic examinations in patients hospitalized for coronavirus disease (COVID-19), particularly during transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE). According to the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) recommendations, in the case of suspected or confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections,1–3 cardiovascular imaging should be considered only on an individual basis when it could substantially change the patient’s management or be life saving. In any case, an appropriate comprehensive safety setting is recommended.2,3 Despite the high risk of contamination, TOE remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis (IE) even in the current COVID-19 pandemic. When transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is non-conclusive, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of IE, TOE should be performed (see diagnostic flowchart in Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Diagnostic flowchart for IE in patients with suspected/confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. IE, infective endocarditis; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PPE, personal protection equipment; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; TOE, transoesophageal echocardiography.

We present the case of a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring mechanical ventilation, who developed IE on the aortic valve during their intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

Timeline

| Day 1 | Hospital admission for fatigue and fever. First nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 tested positive. |

| Day 3 | ARDS requiring mechanical ventilation and ICU admission |

| Day 14 | New onset of worsening fever. Haemocultures tested positive for MRSA. |

| Day 15 | Antibiotic therapy with teicoplanin and ceftazidine/avibactam is started. |

| Day 20 | Transoesophageal echocardiography is performed, showing infective carditis of the aortic valve. |

| Day 21 | Teicoplanin is replaced by linezolid. |

| Day 22 | Antibiotic therapy with fosfomycin is added, with good response. |

| Day 30 | The patient is discharged from the ICU. |

| Day 37 | The patient is transferred to a rehabilitation hospital. |

| Day 50 | Transthoracic echocardiography is performed, showing residual vegetation of smaller dimension. |

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man was admitted in hospital in mid-March 2020 presenting fever and cough in the last 7 days. He suffered an ischaemic stroke in 2015 due to a patent foramen ovale (PFO), treated with percutaneous closure.

Upon admission, he was febrile (temperature 38°C) and symptomatic for cough and dyspnoea, with normal blood pressure (125/80 mmHg), mild oxygen desaturation (94% in room air), and sinus tachycardia (110 b.p.m.). At physical examination, the patient showed bilateral lung crackles, no murmur, and no sign of heart failure. A nasopharyngeal swab tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thoracic computed tomography (CT) outlined bilateral ground-glass and crazy paving pulmonary involvement.

Therapy with hydroxychloroquine and antiviral agents (lopinavir/ritonavir) was empirically started, with poor benefit. After 3 days of hospitalization, the patient developed worsening hypoxaemia non-responsive to ventilation with continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio <100 compatible with ARDS, i.e. an acute diffuse inflammatory lung injury with non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. He was transferred to the ICU, where mechanical ventilation was initiated.

During ICU stay, the patient developed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and was treated with low molecular weight heparin.

After 10 days of ICU stay, the patient re-developed fever; three sets of haemoculture were performed and resulted positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection.

TTE was performed, with a poor ultrasound window, that was not conclusive for IE and showed mild mitral regurgitation and mild impairment of left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction 45%). This was ascribed to sepsis- and ARDS-related myocardial dysfunction, as no significant rise in serial high-sensitivity troponin levels was observed and no regional wall motion abnormality was described. Given the high clinical suspicion for IE (isolation of MRSA, persistently high inflammatory markers, and patient frailty) and the presence of the PFO occlusion device, the patient underwent TOE. This exam was performed by a limited number of healthcare operators, i.e. one echocardiographer and one nurse, at the bedside in the contaminated ICU area (Figure 2). The personnel involved in TOE used the following personal protective equipment (PPE): an isolating water-repellent gown, a double pair of long gloves, safety face shield, advanced masks (FFP3), and knee length shoe covers. Moreover, to avoid contamination, appropriate removal of the PPE after the exam was performed. TOE outlined the presence of endocarditis vegetation (6 × 7 mm in diameter, Figure 3) on the non-coronary cusp of the aortic valve, and excluded paravalvular abscess, abnormalities on the surface of the PFO closure device, or significant dysfunction in other cardiac valves. Colour Doppler examination revealed a tiny perforation of the body of the cusp in proximity to the vegetation (Figure 4), responsible for a mild, eccentric, regurgitant jet, without signs of significant left ventricular volume overload or dilatation.

Figure 2.

Images of the echocardiography pictures taken by an operator from outside the contaminated ICU.

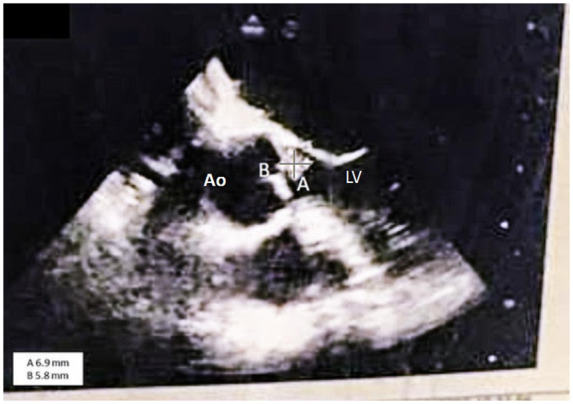

Figure 3.

Mid-oesophageal five-chamber view, 0-degrees: endocarditis vegetation 6 × 7 mm in diameter on the non-coronary cusp of the aortic valve. Ao, ascending aorta; LV, left ventricle.

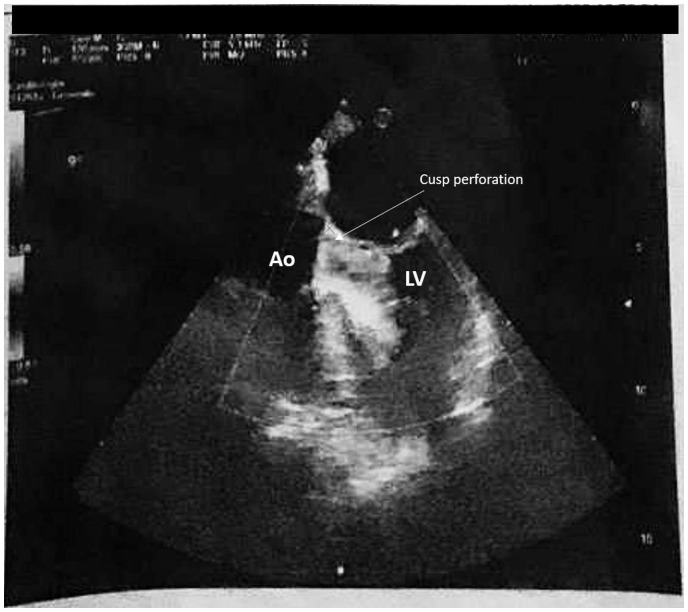

Figure 4.

Monochromatic (black and white) printed colour Doppler images (mid-oesophageal five-chamber view, 0-degrees) showing mild eccentric aortic valve regurgitation by a tiny perforation (arrow) due to the endocarditis vegetation (in the cubicles of the ICU, isolated and specifically dedicated to COVID-19 patients, the echocardiography machine had only a black and white printer). Ao, ascending aorta; LV, left ventricle.

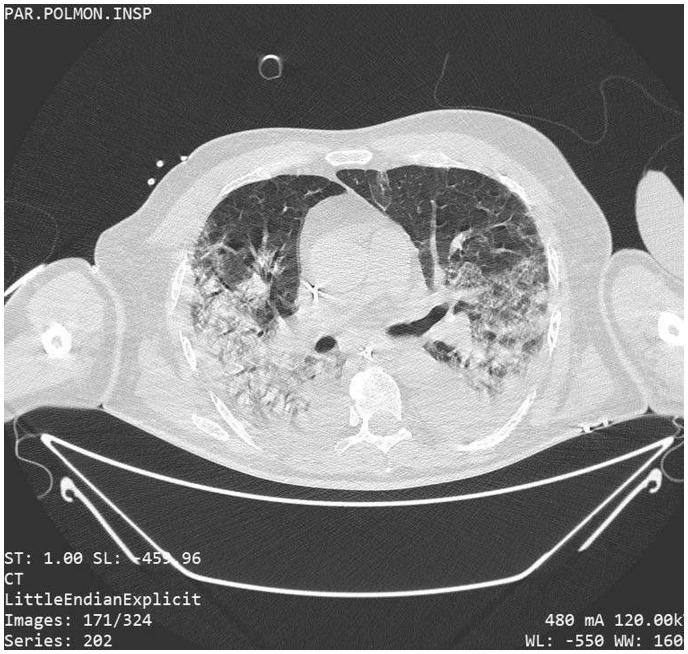

ICU stay was also complicated by ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection, with bilateral areas of increased density at the repeated lung CT (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Computed tomography scan showing severe interstitial pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, complicated by ventilator-associated pneumonia by Klebsiella pneumonia, with bilaterally increased density areas.

The patient was initially treated with teicoplanin and ceftazidime/avibactam; teicoplanin was later replaced by linezolid because of low haematic drug levels and after 7 days fosfomycin was added. Antibiotic therapy led to improvement of the clinical status, with reduction of inflammatory markers, mainly C-reactive protein and procalcitonin.

Considering the SARS-CoV-2 infection and based on the lack of severe aortic valve dysfunction, as well as the absence of endocarditis-related complications, a multidisciplinary team of cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and anaesthesiologists decided that there was no need for urgent valve repair.

After 30 days of ICU stay, the patient was transferred to the Sub-ICU as his clinical conditions had improved. TOE was not repeated, as it would not be likely to change the patient’s management. The patient was then transferred to a rehabilitation hospital. At 1 month after the diagnosis of IE, a TTE was performed showing a smaller vegetation with no sign of significant regurgitation. A new TTE was scheduled at 2-month follow-up that will evaluate the need of surgical valve repair in the case of persistence/progression of the lesion.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with interstitial pneumonia and respiratory failure up to ARDS, especially in patients with previous cardiovascular diseases.4–6

We present here the case of IE caused by MRSA, complicating a SARS-CoV-2 infection in a young patient admitted to our ICU for interstitial pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation. TOE was performed because the suspicion of IE was high (i.e. sepsis due to MRSA in a fragile patient) and because the exam could have changed the patient’s management.1–3 TOE showed a vegetation on the aortic valve and excluded both paravalvular complications (i.e. a paravalvular abscess) and involvement of the previously implanted PFO closure device. These findings allowed us to set up an appropriate antibiotic therapy that turned out to be effective.

In COVID-19 patients with high suspicion of IE, TTE and TOE are mandatory for the diagnosis. In these cases, the safest setting for echocardiographers and other healthcare workers should be ensured in order to avoid contamination.2,3 Accordingly, TOE was performed by a limited number of operators using adequate PPE. The care of the echocardiography machine was also crucial; a single-use see-through plastic full cover was used to reduce the instrument contamination, although this impaired the quality of the images. After the exam, PPE must be properly removed and instruments/materials, including the echocardiography paper, should remain in the contaminated zone.

We want to underline that TOE was performed in a completely unusual setting, i.e. in the hallway of the Emergency Department, where additional ICU beds were hosted for COVID-19 patients, because the regular ICU was overcrowded. The echocardiography machine had only a monochromatic printer and was not provided with an online storage connection. Finally, the use of external USB storage devices was not allowed, in order to reduce the risk of contamination of ‘clean’ areas. Considering these limitations, the only way to collect images was sticking the images printed during the examination to the window of the ICU cubicle and taking photos of these pictures from outside the contaminated room by an external operator, as shown in Figure 2.

Conclusions

TOE represents the gold standard exam for diagnosing IE in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The exam should be performed using all the proper PPE to avoid contamination of operators and instruments.

Lead author biography

Enrico Guido Spinoni was born in Turin, Italy, in 1992. He graduated as an MD in the School of Medicine of Turin University in 2017 with his thesis entitled: ‘Transcatheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy’. He is currently Resident in the Department of Thoracic, Heart and Vascular Diseases of University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy. Since the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy in February 2020, he has volunteered to work in the Sub-ICU of Maggiore della Carità Hospital treating COVID-19 patients.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F. et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015;36:3075–3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirkpatrick JN, Mitchell C, Taub C, Kort S, Hung J, Swaminathan M.. ASE Statement on protection of patients and echocardiography service providers during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;33:648–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Skulstad H, Cosyns B, Popescu BA, Galderisi M, Salvo GD, Donal E, Petersen S, Gimelli A, Haugaa KH, Muraru D, Almeida AG, Schulz-Menger J, Dweck MR, Pontone G, Sade LE, Gerber B, Maurovich-Horvat P, Bharucha T, Cameli M, Magne J, Westwood M, Maurer G, Edvardsen T.. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;21:592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B.. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z.. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, Jain SS, Burkhoff D, Kumaraiah D, Rabbani L, Schwartz A, Uriel N.. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020;141:1648–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.