Abstract

This Delphi consensus by 28 experts from the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) provides initial recommendations on how cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) facilities should modulate their activities in view of the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. A total number of 150 statements were selected and graded by Likert scale [from −5 (strongly disagree) to +5 (strongly agree)], starting from six open-ended questions on (i) referral criteria, (ii) optimal timing and setting, (iii) core components, (iv) structure-based metrics, (v) process-based metrics, and (vi) quality indicators. Consensus was reached on 58 (39%) statements, 48 ‘for’ and 10 ‘against’ respectively, mainly in the field of referral, core components, and structure of CR activities, in a comprehensive way suitable for managing cardiac COVID-19 patients. Panelists oriented consensus towards maintaining usual activities on traditional patient groups referred to CR, without significant downgrading of intervention in case of COVID-19 as a comorbidity. Moreover, it has been suggested to consider COVID-19 patients as a referral group to CR per se when the viral disease is complicated by acute cardiovascular (CV) events; in these patients, the potential development of COVID-related CV sequelae, as well as of pulmonary arterial hypertension, needs to be focused. This framework might be used to orient organization and operational of CR programmes during the COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Prevention, Rehabilitation, COVID-19, Coronavirus

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic poses several questions to the cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) community, both concerning the management of ‘usual’ cardiovascular (CV) patients (often hampered by reduced referral and/or complexity of acute events, due to delayed time-to-care), and the new ‘cardiac-COVID’ phenotype. This latter refers to CV patients suffering from COVID-19, as well as to COVID-19 patients who develop CV complications from the viral disease,1 in which interventions are often empiric due to the novelty of the disease and scant data on long-term prognosis.

From a socio-economic perspective,2 during Phase 1, infection ran in absence of active management. Now—at various times in affected Countries—the COVID-19 crisis is passing through Phase 2 (characterized by social distancing and shutdown of non-core activities) and Phase 3 (i.e. the construction of pandemic management protocols by all organizations in society), and finally will end with the Phase 4, when a vaccine will become available for eradication and/or disease attenuation. During Phases 2 and 3, CR facilities are asked to ‘deliver as much CR as possible’ in a situation characterized by extraordinary measures to prevent the spread of the disease and to organize dedicated clinical services, potentially leading to de-powering/closure of CR services and redeployment of CR staff. Moreover, even in presence of full operation, there is a need of consensus about modulation of CR activities at a local level, with adjustment of process and outcome variables to the COVID-19 era.

In view of this situation, an international panel of experts from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) participated in a Delphi process to identify consensus on CR activities during COVID-19 pandemic, the results of which are provided in this article.

Methods

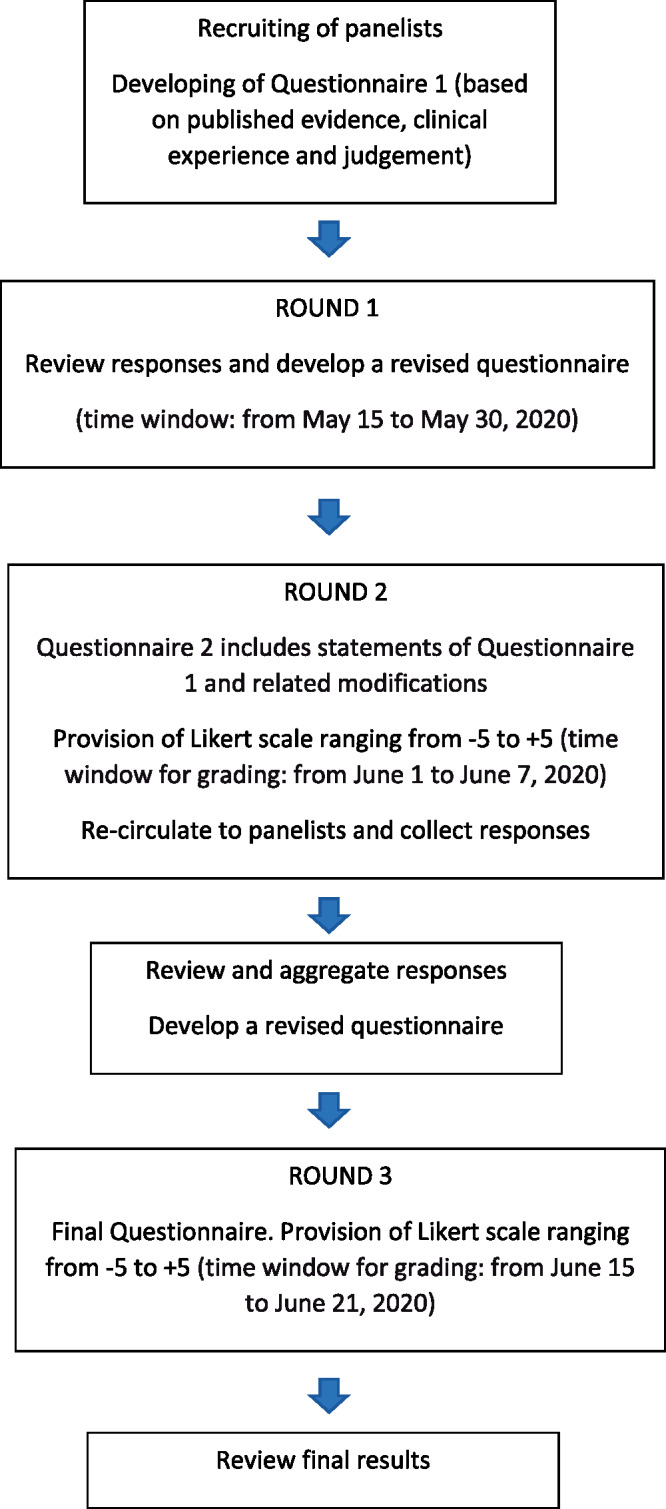

The Delphi methodology3 uses a series of questionnaires to facilitate consensus building among experts within certain topic areas. For the purpose of our study, a rapid modified Delphi process (Figure 1) was designed in three rounds of questionnaires: the first round focused on preparation of open-ended questions to ensure comprehensive inclusion of expert concepts; rounds 2 and 3 applied quantitative assessments to identify consensus. Questionnaire 1 was developed by M.A. and D.H., based on two recent EAPC source documents4,5 on ‘how to’ provide CR intervention, coupled with clinical experience gained during the COVID-19 outbreak, and contained the following six open-ended questions: (i) which are appropriate referrals to CR in the COVID-19 era (by distinguishing CV disease and COVID-19 as primary diagnosis)? (ii) Which are the optimal timing and setting of CR in the COVID-19 era (by distinguishing patients without and with history of COVID-19, respectively)? (iii) Which are the core components of CR in the COVID-19 era (by distinguishing patients without and with history of COVID-19, respectively)? (iv) Which are minimal structure-based metrics for CR programmes in the COVID-19 era? (v) Which are minimal process-based metrics for CR programmes in the COVID-19 era? (vi) Which quality indicators should be selected for CR programmes in the COVID-19 era?

Figure 1.

Modified Delphi process.

Delphi panelists with international recognition as experts in CR were recruited—on a voluntary basis—within the EAPC Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section Nucleus 2018–2020,6 the writing committees of the two EAPC source documents,4,5 the EAPC Exercise Prescription in Everyday Practice and Rehabilitative Training (EXPERT) tool study group,7 and among national experts from countries more heavily affected by COVID-19 selected by the Nucleus.

The Questionnaire 2, containing 150 statements regarding different options and practical approaches to the six open-ended questions (also potentially diverging,), was licensed by the EAPC Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section Nucleus, and incorporated the qualitative concepts from Questionnaire 1. Both Questionnaires 1 and 2 allowed ongoing opportunity for respondent commentary and clarification and were open to modifications.

Panelists were asked to treat statements independently and to rate their agreement with question statements using an 11-point Likert scale from −5 (strongly disagree) to +5 (strongly agree). Panelists had the possibility to skip certain statements, based on individual expertise and professional profile. As in previous experience with the Delphi modified method,8 consensus was defined a priori as either a mean Likert score ≥2.5 or ≤ −2.5 signifying either consensus ‘for’ or ‘against’ the statement, respectively, with standard deviation not crossing zero. Scores > −2.5 and <2.5 indicate no consensus.

Questionnaire 3 contained items from Questionnaire 2, displayed with the mean ± SD of the group’s response in Questionnaire 2, and panelist’s prior response was asked to be confirmed or modified. Selected comments were edited and incorporated anonymously in the statements and questionnaires distributed to panelists in each round.

Data were analysed and reported by descriptive statistics. Differences between panelists answers by countries as categorical variables were tested using either the χ2 or the Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate.

Results

A total of 28 experts from 12 countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, and Switzerland) participated in the Delphi process. Roles in the CR chart were as follows: programme director (n = 9; 32%), cardiologist (n = 12; 43%), physiotherapist (n = 4; 14%), exercise physiologists (n = 2; 7%), and psychologist (n = 1; 4%). The majority of them (93%) declared Phase II CR as the main area of work/interest, while the distribution of the CR setting was as follows: residential (n = 11; 39%), out-patient/ambulatory (n = 16; 57%), and home-based/telerehabilitation (n = 1; 4%).

At the end of the Delphi process, consensus was reached on 58 (39%) statements, with 48 and 10 statements receiving consensus ‘for’ and ‘against’, respectively. Between round 2 and 3, new consensus was found in 6 out of 31 statements for referrals, 3/44 for components, and 2/21 for quality indicators, while all other statements were confirmed. The complete results of the 2nd and 3rd round of the Delphi process are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of the Delphi Questionnaire

| Round 1: Questionnaire development |

Round 2 |

Round 3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Question |

Mean | SD | Intermediate consensus | Mean | SD | Final consensus | |

| n | n | n | n | |||||

| Open question: which are appropriate referrals to CR in the COVID-19 era? | ||||||||

| 1 | Primary diagnosis: CV disease | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘post-ACS and post-primary PCI’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 3.74 | 2.86 | For | 4.22 | 2.11 | For (confirmed) |

| 2 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘chronic coronary syndromes’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 2.77 | 3.05 | NC | 3.14 | 2.51 | For (new) | |

| 3 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘coronary artery or valve heart surgery’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 3.41 | 2.95 | For | 3.91 | 2.27 | For (confirmed) | |

| 4 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘chronic heart failure’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 3.35 | 2.85 | For | 3.96 | 2.14 | For (confirmed) | |

| 5 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘cardiac transplantation’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 2.74 | 3.11 | NC | 3.09 | 2.59 | For (new) | |

| 6 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘device implantation’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 2.14 | 3.43 | NC | 2.64 | 3.09 | NC | |

| 7 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘presence of ventricular assist device’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 2.48 | 3.60 | NC | 3.13 | 2.96 | For (new) | |

| 8 | All patients with primary cardiovascular diagnosis of ‘peripheral artery disease’ should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | 2.04 | 3.15 | NC | 2.57 | 2.86 | NC | |

| 9 | Only patients with ischaemic heart disease as primary cardiovascular qualifying diagnosis to CR should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19 | −2.26 | 3.60 | NC | −2.26 | 3.60 | NC | |

| 10 | Patients with CHF should not be referred’ as referral of this group (i.e. the exercise programme) is more controversial due to the high risk of centre-based CR and safety concerns of telerehabilitation | −1.73 | 3.79 | NC | −2.09 | 3.49 | NC | |

| 11 | Aged/frail patients should not be referred’ as referral of this group (i.e. the exercise programme) is more controversial due to the high risk of centre-based CR and safety concerns of telerehabilitation | −0.82 | 3.74 | NC | −1.09 | 3.45 | NC | |

| 12 | Priorities on which primary cardiovascular qualifying diagnosis should be referred to CR, independently from the history of COVID-19, should be defined at a local level (Hospital/Institution/CR facility) | 2.77 | 3.04 | NC | 2.95 | 2.85 | For (new) | |

| 13 | Only patients with a primary cardiovascular qualifying diagnosis to CR and a history of COVID-19 should be referred to CR | −2.04 | 4.19 | NC | −2.39 | 3.90 | NC | |

| 14 | CV patients referred to CR should have no history of COVID-19 | −2.39 | 3.07 | NC | −2.74 | 2.61 | Against (new) | |

| 15 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those having experienced invasive ventilation | −3.30 | 2.69 | Against | −3.30 | 2.69 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 16 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those having experienced non-invasive ventilation | −3.26 | 2.78 | Against | −3.70 | 2.14 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 17 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those having experienced stay in ICUs | −2.96 | 3.05 | NC | −3.39 | 2.54 | Against (new) | |

| 18 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those having experienced hypoxia | −3.35 | 2.69 | Against | −3.78 | 2.00 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 19 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those having experienced viral pneumonia | −3.70 | 2.12 | Against | −3.70 | 2.12 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 20 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those having experienced any kind of symptom | −3.00 | 2.91 | Against | −3.00 | 2.91 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 21 | Patients referred with a primary qualifying diagnosis for CR and a history of COVID-19 are limited to those aged >75 and/or frail, whichever symptoms of COVID-19 | −3.39 | 2.81 | Against | −3.43 | 2.76 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 22 | Primary diagnosis: COVID-19 | COVID-19 patients should be referred to CR, independently from the history of CV disease | −2.43 | 3.62 | NC | −2.78 | 3.23 | NC |

| 23 | COVID-19 patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease should be referred to CR | 1.17 | 3.73 | NC | 1.09 | 3.65 | NC | |

| 24 | COVID-19 patients with multiple CV risk factors should be referred to CR | 1.64 | 3.51 | NC | 1.55 | 3.45 | NC | |

| 25 | COVID-19 patients complicated by one or more adverse cardiac symptoms/events (angina pectoris, ACS, exacerbation of heart failure, cardiogenic shock, myocarditis, arrhythmias, resuscitated SCD, pericarditis/cardiac tamponade, and/or arterial/venous thromboembolic events) should be referred to CR | 3.68 | 2.68 | For | 3.68 | 2.68 | For (confirmed) | |

| 26 | COVID-19 patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention and/or CIED implantation should be referred to CR | 3.50 | 2.52 | For | 3.50 | 2.52 | For (confirmed) | |

| 27 | COVID-19 patients developing pulmonary arterial hypertension should be referred to CR | 2.91 | 2.45 | For | 2.91 | 2.45 | For (confirmed) | |

| 28 | COVID-19 patients with prolonged stay in ICU should be referred to CR | 0.95 | 4.04 | NC | 0.86 | 3.97 | NC | |

| 29 | COVID-19 patients developing markedly reduced exercise tolerance should be referred to CR | 1.59 | 3.95 | NC | 1.50 | 3.89 | NC | |

| 30 | COVID-19 patients developing cardiovascular complications from therapeutic agents should be referred to CR | 2.41 | 3.19 | NC | 2.32 | 3.14 | NC | |

| 31 | COVID-19 patients with coagulation alterations should be referred to CR | −0.09 | 4.13 | NC | −0.27 | 3.98 | NC | |

| Consensus rate: 39% | Consensus rate: 58% | |||||||

Comments:

|

||||||||

| Open question: which are the optimal timing and setting of CR in the COVID-19 era? | ||||||||

| 32 | Patients without history of COVID | In patients without history of COVID there is no need to modify usual policies/recommendations for timing and setting | 1.78 | 3.72 | NC | 2.30 | 3.28 | NC |

| 33 | In patients without history of COVID there is need for fast track (time from referral to entry <15 days) by CR centres | 1.78 | 3.23 | NC | 2.13 | 2.87 | NC | |

| 34 | In patients without history of COVID there is need for delayed track by CR centres | −1.70 | 3.55 | NC | −2.26 | 3.25 | NC | |

| 35 | In patients without history of COVID the home environment should be preferred to limit people’s movements | 1.70 | 2.57 | NC | 2.09 | 2.15 | NC | |

| 36 | In patients without history of COVID the outpatient setting should be preferred to avoid contacts with hospitalized patients and health operators | 2.87 | 2.40 | For | 2.87 | 2.40 | For (confirmed) | |

| 37 | Patients with history of COVID | In COVID-19 patients CR (mainly exercise component) should begin during the acute phase of the viral disease if the patient is not haemodynamically unstable | −3.10 | 3.06 | Against | −3.48 | 2.44 | Against (confirmed) |

| 38 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin after clinical recovery of pneumonia | 1.00 | 3.86 | NC | 1.33 | 3.61 | NC | |

| 39 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin after radiologic recovery of pneumonia | −0.14 | 3.80 | NC | −0.38 | 3.53 | NC | |

| 40 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin after resolution of COVID-19 induced hypoxia | 2.14 | 3.34 | NC | 2.29 | 3.42 | NC | |

| 41 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin when no more clinical signs | 0.38 | 4.17 | NC | 0.95 | 3.77 | NC | |

| 42 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin after the end of COVID-19 treatment regimen | −0.33 | 3.75 | NC | −0.24 | 3.65 | NC | |

| 43 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin after NIV has been stopped | 0.00 | 4.10 | NC | 0.33 | 3.80 | NC | |

| 44 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin when the P/f value is above 100 | −1.50 | 2.50 | NC | −1.41 | 2.45 | NC | |

| 45 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin when the P/f value is above 200 | 0.00 | 2.48 | NC | 0.47 | 2.12 | NC | |

| 46 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin when the P/f value is above 300 | 1.31 | 2.50 | NC | 1.24 | 2.44 | NC | |

| 47 | In COVID-19 patients the beginning of CR is independent from arterial blood gas parameters | −1.71 | 3.36 | NC | −1.95 | 3.02 | NC | |

| 48 | In COVID-19 patients CR should begin after two negative nasopharyngeal specimens for COVID-19 | 1.43 | 3.80 | NC | 1.52 | 3.66 | NC | |

| 49 | In COVID-19 patients CR should always comprise a first residential step | −0.68 | 3.17 | NC | −0.68 | 3.17 | NC | |

| 50 | In COVID-19 patients CR should always comprise an outpatient step | 0.64 | 3.35 | NC | 0.64 | 3.35 | NC | |

| 51 | In COVID-19 patients CR should be always offered as home-rehabilitation or mixed programmes when appropriate (if available) | 2.33 | 3.14 | NC | 2.43 | 3.19 | NC | |

| 52 | In COVID-19 patients enrolled in ambulatory or home-rehabilitation programmes, digital health tools should be integrated by tracing systems (Gps) | 2.18 | 3.08 | NC | 2.18 | 3.08 | NC | |

| Consensus rate: 10% | Consensus rate: 10% | |||||||

Comments:

|

||||||||

| Open question: which are the core components of CR in the COVID-19 era? | ||||||||

| 53 | Patients without history of COVID | In patients without history of COVID there is no need to modify usual policies/recommendations for core components delivery | 1.87 | 4.30 | NC | 2.17 | 4.01 | NC |

| 54 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to exclude the presence of COVID-19 | 2.61 | 2.87 | NC | 2.65 | 2.42 | For (new) | |

| 55 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘patient assessment’ | −0.87 | 4.04 | NC | −0.78 | 3.97 | NC | |

| 56 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘physical activity counselling’ | −0.95 | 3.80 | NC | −0.86 | 3.72 | NC | |

| 57 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘exercise training’ | −1.09 | 4.01 | NC | −1.18 | 3.89 | NC | |

| 58 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘diet/nutritional counselling’ | −2.91 | 2.96 | NC | −2.82 | 2.92 | NC | |

| 59 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘weight control management’ | −2.82 | 2.95 | NC | −2.82 | 2.95 | NC | |

| 60 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘lipid management’ | −2.77 | 2.96 | NC | −2.77 | 2.96 | NC | |

| 61 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘blood pressure management’ | −2.82 | 2.97 | NC | −2.82 | 2.97 | NC | |

| 62 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘smoking cessation’ | −2.91 | 2.83 | Against | −2.91 | 2.83 | Against (confirmed) | |

| 63 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘psychosocial management’ | −1.09 | 4.10 | NC | −1.00 | 4.03 | NC | |

| 64 | In patients without history of COVID there is need to include specific education on COVID-19 | 3.00 | 2.91 | For | 3.43 | 2.35 | For (confirmed) | |

| 65 | Patients with history of COVID | In patients with history of COVID-19 usual core components of CR delivery should be supplemented with other specific interventions | 3.09 | 3.10 | NC | 3.45 | 2.52 | For (new) |

| 66 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Patient evaluation should always comprise respiratory impairment and other COVID-19 features | 3.57 | 2.50 | For | 3.57 | 2.50 | For (confirmed) | |

| 67 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Chest X-ray should always be performed at beginning of the CR programme | 1.43 | 3.63 | NC | 1.90 | 3.30 | NC | |

| 68 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Nasopharyngeal specimen should always be performed at beginning of the CR programme | 1.05 | 3.97 | NC | 1.75 | 3.58 | NC | |

| 69 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Nasopharyngeal specimen should always be performed during of the CR programme | −0.80 | 3.65 | NC | −0.10 | 3.63 | NC | |

| 70 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Serology for COVID-19 should always be performed at beginning of the CR programme | −0.20 | 3.78 | NC | 0.45 | 3.61 | NC | |

| 71 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Serology for COVID-19 should always be performed during the CR programme | −2.45 | 3.43 | NC | −2.20 | 3.41 | NC | |

| 72 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Chest CT-scan should always be performed during the CR programme | −1.85 | 3.38 | NC | −1.75 | 3.31 | NC | |

| 73 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Arterial blood gas analysis should always be performed during the CR programme | −0.10 | 3.78 | NC | −0.19 | 3.72 | NC | |

| 74 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Direct testing of exercise capacity (CPET preferred) should always be performed at the start of the CR programme | 3.14 | 2.46 | For | 3.14 | 2.46 | For (confirmed) | |

| 75 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Indirect testing for exercise capacity should always be performed at the start of the CR programme | 2.38 | 2.96 | NC | 2.38 | 2.96 | NC | |

| 76 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. Frailty should always be investigated during the CR programme | 3.05 | 2.80 | For | 3.05 | 2.80 | For (confirmed) | |

| 77 | Core component ‘patient evaluation’. History of COVID-19 (symptomatic or asymptomatic) among family and caregivers should always be collected | 2.90 | 3.05 | NC | 3.00 | 2.98 | For (new) | |

| 78 | In patients with history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘physical activity counselling’ | 1.10 | 4.18 | NC | 1.48 | 3.96 | NC | |

| 79 | Core component ‘exercise training’. IMT and/or other respiratory techniques should be included as normally indicated in the exercise training programme | 2.76 | 3.02 | NC | 2.76 | 2.58 | For (new) | |

| 80 | Core component ‘exercise training’. Strength training in COVID-19 should be included as normally indicated in CR programmes | 3.71 | 1.98 | For | 3.67 | 1.96 | For (confirmed) | |

| 81 | Core component ‘exercise training’. Strength training in frail COVID-19 patients should be included as normally indicated in CR programmes | 3.90 | 1.61 | For | 4.10 | 1.34 | For (confirmed) | |

| 82 | Core component ‘exercise training’. Low-to-moderate intense endurance training should always be executed in COVID-19 patients as normally indicated in CR programmes | 2.62 | 2.65 | NC | 2.62 | 2.65 | NC | |

| 83 | Core component ‘exercise training’. High-intensity interval training training should always be executed by COVID-19 patients as normally indicated in CR programmes | 0.24 | 3.45 | NC | 0.14 | 3.42 | NC | |

| 84 | Core component ‘exercise training’. All COVID-19 patients should execute structured exercise for at least 3 days/week | 3.19 | 2.50 | For | 3.19 | 2.50 | For (confirmed) | |

| 85 | Core component ‘exercise training’. All COVID-19 patients should maximize non-structured physical activity at home on daily basis | 3.76 | 1.87 | For | 3.76 | 1.87 | For (confirmed) | |

| 86 | Core component ‘exercise training’. During structured exercise training, cardiac telemetry is advised to all COVID-19 patients | 0.95 | 3.17 | NC | 0.76 | 3.91 | NC | |

| 87 | Core component ‘diet/nutritional counselling’. Nutritional intervention should be always particularly devoted to malnutrition as a consequence of prolonged immobilization and ventilatory support | 2.95 | 2.54 | For | 3.14 | 2.46 | For (confirmed) | |

| 88 | In patients with history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘weight control management’ | −0.71 | 4.04 | NC | −0.62 | 3.96 | NC | |

| 89 | In patients with history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘lipid management’ | −0.86 | 3.99 | NC | −0.76 | 3.91 | NC | |

| 90 | In patients with history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘blood pressure management’ | −1.33 | 3.83 | NC | −1.33 | 3.72 | NC | |

| 91 | In patients with history of COVID there is need to modify the core component ‘smoking cessation’ | −2.00 | 3.83 | NC | −1.91 | 3.78 | NC | |

| 92 | Core component ‘psychosocial management’. Lifestyle and psychosocial management should always particularly focused on smoking cessation | 3.00 | 2.94 | For | 3.27 | 2.62 | For (confirmed) | |

| 93 | Core component ‘psychosocial management’. Lifestyle and psychosocial management should always particularly focused on fear of infection | 2.73 | 3.19 | NC | 2.73 | 3.19 | NC | |

| 94 | Core component ‘psychosocial management’. Lifestyle and psychosocial management should always particularly focused on fighting of fake news | 3.36 | 2.26 | For | 3.36 | 2.26 | For (confirmed) | |

| 95 | Core component ‘psychosocial management’. Lifestyle and psychosocial management should always particularly focused on caregiver-limiting restrictive measures | 2.82 | 2.44 | For | 2.82 | 2.44 | For (confirmed) | |

| 96 | Core component ‘psychosocial management’. Lifestyle and psychosocial management should always particularly focused on working resume | 3.82 | 1.65 | For | 3.82 | 1.65 | For (confirmed) | |

| Consensus rate: 32% | Consensus rate: 41% | |||||||

Comments:

|

||||||||

| Open question: which are minimal structure-based metrics for CR programmes in the COVID-19 era? | ||||||||

| 97 | There is no need to modify usual policies/recommendations for structure-based metrics | −1.71 | 3.86 | NC | −1.77 | 3.78 | NC | |

| 98 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for confirmed COVID cases with regard to beds | 3.55 | 2.91 | For | 3.61 | 2.86 | For (confirmed) | |

| 99 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for confirmed COVID cases with regard to investigation rooms | 2.82 | 3.22 | NC | 2.83 | 3.14 | NC | |

| 100 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for confirmed COVID cases with regard to consultation areas | 3.05 | 3.18 | NC | 3.04 | 3.11 | NC | |

| 101 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for confirmed COVID cases with regard to exercise laboratories | 2.77 | 3.21 | NC | 2.83 | 3.14 | NC | |

| 102 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for confirmed COVID cases with regard to areas for exercise training | 2.68 | 3.27 | NC | 2.74 | 3.21 | NC | |

| 103 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for suspected COVID cases with regard to beds | 3.45 | 2.89 | For | 3.52 | 2.84 | For (confirmed) | |

| 104 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for suspected COVID cases with regard to investigation rooms | 2.68 | 3.03 | NC | 2.70 | 2.96 | NC | |

| 105 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for suspected COVID cases with regard to consultation areas | 2.91 | 3.10 | NC | 2.91 | 3.03 | NC | |

| 106 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for suspected COVID cases with regard to exercise laboratories | 2.64 | 3.11 | NC | 2.70 | 3.05 | NC | |

| 107 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for suspected COVID cases with regard to exercise training | 2.73 | 3.15 | NC | 2.78 | 3.09 | NC | |

| 108 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for COVID-free cases with regard to beds | 2.67 | 3.77 | NC | 2.77 | 3.72 | NC | |

| 109 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for COVID-free cases with regard to investigation rooms | 2.24 | 3.60 | NC | 2.27 | 3.52 | NC | |

| 110 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for COVID-free cases with regard to consultation areas | 2.24 | 3.60 | NC | 2.27 | 3.52 | NC | |

| 111 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for COVID-free cases with regard to exercise laboratories | 2.19 | 3.60 | NC | 2.27 | 3.53 | NC | |

| 112 | Residential CR facilities should have separated areas for confirmed COVID-frees with regard to areas for exercise training | 2.33 | 3.31 | NC | 2.41 | 3.25 | NC | |

| 113 | When performing CPET and/or other aerosol-generating testing, approved filters for protecting workers and other patients from exposure to SARS-CoV-2 should be available | 4.55 | 1.18 | For | 4.57 | 1.16 | For (confirmed) | |

| 114 | When performing CPET and/or other aerosol-generating testing, approved FFP-2 masks should be worn to protect workers and other patients from exposure to SARS-CoV-2 should be available | 4.68 | 0.89 | For | 4.70 | 0.88 | For (confirmed) | |

| 115 | Floor space during exercise training is increased from 4 to at least 6 m2 per patient | 3.41 | 3.00 | For | 3.48 | 2.95 | For (confirmed) | |

| 116 | In the CR facility PPE for health care workers should be worn | 4.17 | 1.50 | For | 4.21 | 1.47 | For (confirmed) | |

| 117 | A CR programme director to ensure proper organization and consistency of activities with national and institutional rules concerning SARS-CoV-2 infection prevention should be present | 4.09 | 1.44 | For | 4.13 | 1.42 | For (confirmed) | |

| 118 | The multidisciplinary team (cardiologist, nurse, exercise specialist, dietitian, psychologist) should be preserved as much as possible | 4.57 | 1.16 | For | 4.58 | 1.14 | For (confirmed) | |

| 119 | All members of the multidisciplinary should receive structured education on COVID-19 pathophysiology, clinical features, treatment, and prevention strategies | 4.52 | 1.31 | For | 4.54 | 1.28 | For (confirmed) | |

| 120 | The job description for every profession should be updated with specific COVID-19 oriented features | 3.65 | 2.52 | For | 3.71 | 2.48 | For (confirmed) | |

| 121 | The CR facility should provide dedicated operators and structured procedures facilitating contacts between patients and families in case of lockdown | 4.22 | 1.38 | For | 4.25 | 1.36 | For (confirmed) | |

| Consensus rate: 44% | Consensus rate: 44% | |||||||

Comments:

|

||||||||

| Open question: which are minimal process-based metrics for CR programmes in the COVID-19 era? | ||||||||

| 122 | There is no need to modify usual policies/recommendations for process-based metrics | −1.10 | 3.91 | NC | −1.19 | 3.78 | NC | |

| 123 | The CR unit should provide fast testing and quarantine until test results are available in case of suspected or confirmed new emerging COVID-19 cases among the referred population | 3.32 | 2.66 | For | 3.32 | 2.66 | For (confirmed) | |

| 124 | The suggested duration of CR programmes should be shortened (less than recommended 24 sessions), to increase the absolute number of CR programmes potentially delivered in a time unit | −0.77 | 3.75 | NC | −0.68 | 3.67 | NC | |

| 125 | Patients coming for a CPET or other aerosol-generating procedures are first need to confirm to be COVID-19 negative | 2.45 | 2.69 | NC | 2.41 | 2.65 | NC | |

| 126 | Plan at discharge and structured follow-up should be adapted to different phases of COVID-19 outbreak, in terms of timeline and diagnostic tools | 3.95 | 1.40 | For | 3.95 | 1.40 | For (confirmed) | |

| 127 | CR facilities should offer a continuing help-desk to discharged patients and their caregivers on how to manage the relationship between COVID-10 and cardiovascular conditions | 2.91 | 2.37 | For | 2.91 | 2.37 | For (confirmed) | |

| 128 | CR facilities with structured alternative models for delivering activities (tele-rehabilitation, facilitated home-based, web-based, supervised community-based, guided by digital health tools, etc.) should integrate the management of COVID-19 among programme contents | 4.09 | 1.38 | For | 4.09 | 1.38 | For (confirmed) | |

| 129 | CR facilities without structured alternative models for delivering activities should implement initial forms of tele-rehabilitation, with integration of management of COVID-19 among programme contents | 3.83 | 1.70 | For | 3.96 | 1.58 | For (confirmed) | |

| Consensus rate: 62% | Consensus rate: 62% | |||||||

Comments:

|

||||||||

| Open question: which are quality indicators for CR programmes in the COVID-19 era? | ||||||||

| 130 | There is no need to modify usual quality indicators in non-COVID patients | 1.96 | 3.77 | NC | 1.87 | 3.72 | NC | |

| 131 | There is no need to modify usual quality indicators in COVID patients | 0.91 | 3.96 | NC | 0.74 | 3.84 | NC | |

| 132 | % patients without history of COVID-19 eligible to CR referred after discharge to CR programme. The target should be maintained >80% as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 2.77 | 3.16 | NC | 2.73 | 2.61 | For (new) | |

| 133 | % patients without history of COVID-19 eligible to CR referred after discharge to CR programme. The target should be reduced to <80% due to logistic problems during COVID-19 pandemia | 0.05 | 4.03 | NC | 0.15 | 3.92 | NC | |

| 134 | % patients without history of COVID-19 eligible to CR, enrolled after discharge from COVID-19 units. The target should be >50% as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 2.33 | 3.35 | NC | 2.29 | 3.32 | NC | |

| 135 | % patients without history of COVID-19 eligible to CR, enrolled after discharge from COVID-19 units. The target should be reduced to <50% due to logistic problems during COVID-19 pandemia | −0.95 | 3.62 | NC | −0.85 | 3.53 | NC | |

| 136 | Patients without history of COVID-19, median waiting time from referral to start of CR. The target should be 14-28 days as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 2.29 | 3.47 | NC | 2.29 | 3.47 | NC | |

| 137 | Patients without history of COVID-19, median waiting time from referral to start of CR. The target should be reduced to <14–28 days, motivated by the necessity to avoid prolonged lack of contacts with health care providers | −0.33 | 3.77 | NC | −0.24 | 3.67 | NC | |

| 138 | Patients without history of COVID-19, % of CR uptake. The minimal target should be 24 sessions as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 3.64 | 2.38 | For | 3.73 | 2.31 | For (confirmed) | |

| 139 | Patients without history of COVID-19, % of CR uptake. The minimal target should be <24 sessions to increase the absolute number of CR programmes potentially delivered in a time unit | −1.62 | 4.07 | NC | −1.71 | 3.87 | NC | |

| 140 | % patients with history of COVID-19 eligible to CR referred after discharge to CR programme. The target should be maintained >80% as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 2.05 | 3.73 | NC | 2.00 | 3.70 | NC | |

| 141 | % patients with history of COVID-19 eligible to CR referred after discharge to CR programme. The target should be reduced to <80% due to logistic problems during COVID-19 pandemia | −1.35 | 3.62 | NC | −1.25 | 3.54 | NC | |

| 142 | % patients with history of COVID-19 eligible to CR, enrolled after discharge from COVID-19 units. The target should be >50% as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 1.86 | 3.55 | NC | 1.86 | 3.55 | NC | |

| 143 | % patients with history of COVID-19 eligible to CR, enrolled after discharge from COVID-19 units. The target should be reduced to <50% due to logistic problems during COVID-19 pandemia | −1.05 | 3.64 | NC | −0.95 | 3.56 | NC | |

| 144 | Patients with history of COVID-19, median waiting time from referral to start of CR. The target should be 14–28 days as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 2.33 | 3.40 | NC | 2.33 | 3.40 | NC | |

| 145 | Patients with history of COVID-19, median waiting time from referral to start of CR. The target should be reduced to <14–28 days, motivated by the necessity to avoid prolonged lack of contacts with health care providers | −1.38 | 3.65 | NC | −1.29 | 3.58 | NC | |

| 146 | Patients with history of COVID-19, % of CR uptake. The minimal target should be 24 sessions as recommended by the 2020 position statement | 2.64 | 3.11 | NC | 2.64 | 3.11 | NC | |

| 147 | Patients with history of COVID-19, % of CR uptake. The minimal target should be <24 sessions to increase the absolute number of CR programmes potentially delivered in a time unit | −1.90 | 3.60 | NC | −1.95 | 3.54 | NC | |

| 148 | % of CR drop-out due to de novo COVID-infection. The target should be <10% | 3.00 | 3.13 | NC | 3.00 | 3.13 | NC | |

| 149 | % of patients with evaluation of functional capacity by standard exercise testing. The target should be >50% | 2.86 | 3.17 | NC | 3.00 | 2.94 | For (new) | |

| 150 | % of patients with improvement of altered respiratory function and gas exchange following completion of CR. Target >90% | 2.82 | 2.81 | For | 2.82 | 2.81 | For (confirmed) | |

| Consensus rate: 10% | Consensus rate: 20% | |||||||

Comments:

|

||||||||

Including mean and standard deviation of the Likert scale. Consensus ‘for’ (mean score ≥2.5) or ‘against’ (mean score ≤2.5) each statement is indicated, while ‘NC’ (no consensus) indicates that consensus has not been reached (i.e. mean score between 2.4 and −2.4 or standard deviation crossing zero). The final consensus for each statement has been specified if confirmed or new, the latter indicating modification from round 2 to round 3. For each open question the consensus rate obtained at round 2 and 3 are provided. Comments have been edited for repetition, clarity, and anonymity, and served to present the whole picture of experts’ opinion.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CHF, chronic heart failure; CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; CO%Hb, percentage of carboxyhaemoglobin; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; CV, cardiovascular; GPS, global positioning system; HTX, heart transplantation; ICU, intensive care unit; IMT, inspiratory muscle training; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPE, personal protective equipment; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

Referrals to cardiovascular rehabilitation

Among patients with CV disease as primary diagnosis, panelists reached consensus on continuing referral to CR—independently from an eventual history of COVID-19—for the following major conditions: post-acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and post-primary angioplasty (4.22 ± 2.11), chronic coronary syndromes (3.14 ± 2.51), coronary artery or valve heart surgery (3.91 ± 2.27), chronic heart failure (3.96 ± 2.14), cardiac transplantation (3.09 ± 2.59), and presence of ventricular assist device (3.13 ± 2.96). Other conditions, such as device implantation and peripheral artery disease, did not reach consensus; however, consensus was reached on priorities with regard to CV referral diagnoses to be defined at a local level (Hospital, Institution, CR facility) (2.95 ± 2.85). When a history of COVID-19 was present in this patient population, neither previous invasive/non-invasive ventilation nor other COVID-19 related conditions (i.e. prolonged stay in intensive care units, hypoxia, viral pneumonia, or respiratory symptoms) constituted criteria for patient selection in the referral process (Likers scale scores all ≤ −3.0).

Among patients with COVID-19 as primary diagnosis, highest degrees of consensus were reached on considering several acute complicating CV events (angina pectoris, ACS, exacerbation of heart failure, cardiogenic shock, myocarditis, arrhythmias, resuscitated sudden cardiac death, pericarditis/cardiac tamponade, and arterial/venous thromboembolic events) as appropriate referrals to CR (3.68 ± 2.68), as well as the progressive developing of pulmonary arterial hypertension (2.91 ± 2.45). Regardless of criteria for referral, CR should take place only in documented COVID free patients (namely, a single or double negative nasopharyngeal specimen for COVID-19, depending on local policies).

Timing and setting of cardiovascular rehabilitation

Regarding timing of CR, in CV patients without history of COVID-19, no statement considering track variations to CR reached consensus, while in primary COVID-19 patients there was orientation against starting CR during the acute phase of the viral disease (−3.48 ± 2.44). Other COVID-19 related features (such as radiologic recovery of pneumonia or arterial blood gas parameters) were not necessarily considered determinants for the timing to start CR.

In CV patients without history of COVID-19, the outpatient setting was deemed as the preferred setting to avoid contacts with hospitalized patients and health operators (2.87 ± 2.40), especially when residential CR facilities are not separated from other wards.

Core components of cardiovascular rehabilitation

In patients without history of COVID-19 there was no need to modify traditional core components of CR intervention, with the exception to provide specific education on COVID-19 within counselling activities (3.43 ± 2.35).

In patients presenting with a history of COVID-19 the core component ‘patient evaluation’ should always comprise patterns of respiratory impairment (3.57 ± 2.50) and, in view of the often multifactorial aetiology of exercise intolerance in these patients, cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) should always be performed—when confirmed negative testing for COVID-19—at the start of the CR programme (3.14 ± 2.46). The active search of frailty (3.05 ± 2.80), as far as a detailed history of symptomatic or asymptomatic COVID-19 among relatives and caregivers (3.00 ± 2.98), should also be part of the recommended strategy for evaluating patients during CR programmes. In healed-up COVID-19 patients, strength training should also be included as normally indicated in CR programmes (3.67 ± 1.96), especially in frail patients (4.10 ± 1.34), while inspiratory muscle training (IMT) or other respiratory techniques did not reach definite consensus ‘for’ or ‘against’. In any case, whatever the selected exercise protocol, patients should maximize non-structured physical activity at home on daily basis (3.76 ± 1.87). The core component ‘diet/nutritional counselling’ should always be particularly devoted to malnutrition as a consequence of prolonged immobilization and ventilatory support (3.14 ± 2.46). The psychosocial management in COVID-19 patients constituted the top area of consensus for reinforced intervention on growing needs, such as smoking cessation (3.27 ± 2.62), return to work (3.82 ± 1.65), caregiver-limiting restrictive measures (2.82 ± 2.44), and fighting of fake news (3.36 ± 2.26).

Structure-based metrics

There was consensus on modifying structure-based metrics in residential CR facilities, especially with respect to allocation of separate areas to newly confirmed (3.61 ± 2.86) and suspected (3.52 ± 2.84) COVID-19 cases, as well as to availability of adequate protection to health operators and patients during aerosol-generating manoeuvres, indoor exercise training, and all phases of the multidisciplinary staff activity (details in Table 1). A particularly high consensus score was reached (4.25 ± 1.36) on the recommendation to formally structure contacts between patients and families in case of lockdown.

Process-based metrics

Among actions modulating the processes of CR facilities, there was strong consensus (4.09 ± 1.38) on encouraging remote activities (tele-rehabilitation, facilitated home-based, web-based, supervised community-based, guided by digital health tools, etc.) that might integrate or fully replace routine operational of residential and ambulatory CR facilities, according to different phases of COVID-19 pandemic. Special attention should also be payed to the transition to primary care after the end of the programme, by identifying discharge plans consistent with limitations related to the COVID-19 outbreak (e.g. travel restrictions impeding lifestyle prescriptions or scheduled examinations; 3.95 ± 1.40). As a practical suggestion, there was consensus on providing a continuing help-desk to discharged patients and their caregivers on how to manage the relationship between COVID-19 and CV conditions (2.91 ± 2.37).

Quality indicators

As a result of the Delphi process applied to quality indicators for CR programmes, no consensus was reached for modulating previously recommended5 operational standards, in terms of referral rate, taking charge, minimum number of sessions, programme completion, drop-out rate, and absolute number of CR programmes in a time unit, both in patients with and without history of COVID-19. As a new target specifically introduced to COVID-19 patients presenting altered respiratory function and/or gas exchange alterations, a significant improvement should be reached in more than 90% of patients at the end of the CR programme (2.82 ± 2.81).

Impact of COVID-19 experience

Panelists answers were stratified according to home countries with regard to COVID-19 incidence.9 Consensus was significantly higher (67% vs. 32%, P < 0.05) among experts coming from countries with incidence of COVID-19 ≥ 400 cases per 100 000 population at the time of interview (Belgium, Italy, Portugal, Russia, Spain), as compared to countries with less incidence (Austria, France, Germany, Greece, The Netherlands, Romania, Switzerland). Experts from high incidence countries were more oriented towards the possibility of delayed referral to CR for stable chronic cardiac patients, the need of complete resolution of major COVID-19 symptoms before entering CR facilities, and the consideration of simplified procedures to accelerate patients turnover (see comments in Table 1).

Discussion

Shortly after the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, the problem on how to ensure proper delivery of CR activities across Europe has surfaced. Several national institutions adopted formal positions on this topic,10–14 and the EAPC itself provided fast general recommendations,15 followed by a structured call to action for cardiac telerehabilitation as a tool to help CV patients not able to visit outpatient CR clinics regularly.16 Given the absence of evidence-based guidelines on how CR facilities should orient organizational aspects and performances during the COVID-19 crisis in Europe, expert consensus might supply clinically useful guidance. This Delphi process enrolled EAPC experts also from nations most affected by COVID-19 and adopted a pragmatic approach aimed to identify major drivers of CR intervention (referral, timing, setting, core components, institutional structure and process, and quality indicators) to be customized to the new era.

As main results, panelists oriented consensus towards maintaining usual activities on traditional patient groups referred to CR: in absence of COVID-19, CR may follow usual setting (with preference for ambulatory), timing, and core components of intervention, while programmes including COVID-19 patients should pay special attention to respiratory impairment, psychosocial management, and caregivers, also by encouraging multicomponent home rehabilitation.

This position aimed at avoiding significant downgrading of CR intervention was based on adverse consequences of depriving large portion of CV patients of structured secondary prevention, with a potential increasing number of those suffering from major CV events and progressive disability in the next future.17 Panelists also suggested to consider COVID-19 patients as a referral group to CR per se when the viral disease has been complicated by acute CV events, and to strongly cooperate with pulmonologists. In an economic perspective, over the primary mission to care and promote health, this approach might lead to further opportunities to CR facilities, and generally speaking, the discipline of cardiac prevention and rehabilitation might be electively involved in the development of specific recommendations for multicomponent rehabilitation in COVID-19, which should not be confined into the pulmonary setting.

With regard to core components of intervention in the ‘cardiac-COVID’ patient, we do not have at the moment intervention trials or cohort studies able to identify the proper strategy in the proper patient, and the expected outcome. For this reason, most of suggested adaptations to usual recommendations4 are quite anecdotal and based on real-life practice. Interestingly, after the frantic search for the best pharmacologic treatment of COVID-19, this expert consensus is highly regarded on psychosocial support to patients and their relatives/caregivers, as part of really multicomponent CR programmes,18 to better meet growing population’s needs after the emergency phase. An important consensus was also reached on the need for continuing CPET activities, in line with other expert opinions on this topic,19 to ensure a properly test-guided and individualized training programme.

In this revised definition of structure- and process-based metrics of CR programmes, cardiac telerehabilitation has been naturally invoked as a support of CR in times of temporary closure of centre-based CR programmes, limited centre resources, and restricted patient travel.16 Anyway, rather than a temporary alternative, cardiac telerehabilitation should be considered as a necessary provision of modern CR activities, and the sudden increased experience with digital communication by patients and health care providers during this pandemic could be properly exploited and addressed.

As a major strength, this document provides a structured answer to an urgent need by CR facilities, to be supported in the definition of priorities and allocation of human and technological resources still available, while at the same time several national health systems are suffering and large case studies are still in-progress.

Several limitations of this expert consensus need to be taken into consideration. First, the heterogeneity of expert positions according to different countries and different pandemic phases, which makes it difficult and probably impractical to pursue a globalizing point of view. As a consequence, due to different epidemic spreading among regions, recommendations need to be carefully adapted not only at a country level, but often at a regional and local level, and this is in line with previous recommendations to CR facilities to be flexible and creative,16 by constantly monitoring the situation and being prepared to change the framework. Second, the limited rate of consensus obtained (about 40% of all proposed statements), which may reflect different attitudes and concepts regarding the role of CR during the COVID-19 crisis, probably linked to different time courses of epidemic across Europe. As an example, changes in opinion of panelists between round 2 and 3 might also be due to an adaptation, better understanding or eventually to a personal experience change during the ongoing pandemic/referrals, even in a short time. In this view, there is need for continuing education on COVID-19 disease in the learning path of CR teams. Finally, other methodological limitations such as the ex ante selection of a consensus method based on mean and SD (without preliminary testing for normal distribution of grading results), and the absence of a structured tool to quote statements for relevance, need also to be considered.

In conclusion, even in COVID-19 times CR retains its importance for the care of CV patients, and now more than ever there is need for creativity and innovation in this discipline. In the current climate, telerehabilitation has been systematically invoked as the best solution for continuing CR activities nevertheless, while essential, it still need specific optimization and cannot be provided to all patients. For this reason, as long as with the spreading of the pandemic, the CR European network is called upon to reconsider all operational aspects of intervention and to prepare all health operators as well.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Contributor Information

Marco Ambrosetti, Email: marco.ambrosetti@icsmaugeri.it.

Ana Abreu, Serviço de Cardiologia, Hospital Universitário de Santa Maria/Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte (CHULN), Centro Académico de Medicina de Lisboa (CAML), Centro Cardiovascular da Universidade de Lisboa (CCUL), Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal.

Veronique Cornelissen, Cardiovascular Exercise Physiology Group, Leuven KU, Belgium.

Dominique Hansen, REVAL and BIOMED-Rehabilitation Research Center, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium.

Marie Christine Iliou, Department of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention, Hôpital Corentin Celton, Assistance Publique Hopitaux de Paris Centre-Universite de Paris, Paris, France.

Hareld Kemps, Department of Cardiology, Máxima Medical Centre, Veldhoven, The Netherlands; Department of Industrial Design, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

Roberto Franco Enrico Pedretti, Cardiology Department, IRCCS Multimedica, Sesto San Giovanni, Italy.

Heinz Voller, Klinik am See, Rehabilitation Center for Internal Medicine, Berlin, Germany; Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany.

Mathias Wilhelm, Department of Cardiology, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Massimo Francesco Piepoli, Heart Failure Unit, G. da Saliceto Hospital, AUSL Piacenza and University of Parma, Parma, Italy.

Chiara Giuseppina Beccaluva, Pulmonary Rehabilitation Unit, ASST Ospedale Maggiore, Crema, Italy.

Paul Beckers, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences and Physiotherapy, Antwerp University, Crema, Belgium.

Thomas Berger, St. John of God's Hospital Linz, Linz, Austria.

Costantinos H Davos, Cardiovascular Research Laboratory, Biomedical Research Foundation, Academy of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Paul Dendale, Heart Centre, Jessa Hospital Campus Virga Jesse, Hasselt, Belgium; Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium.

Wolfram Doehner, Department of Cardiology (Virchow Klinikum), German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), Berlin, Germany; BCRT - Berlin Institute of Health Center for Regenerative Therapies, Center for Stroke Research Berlin, Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany.

Ines Frederix, Department of Cardiology, Jessa Hospital, Hasselt, Belgium.

Dan Gaita, Institutul de Boli Cardiovasculare, Universitatea de Medicina si Farmacie Victor Babes din Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania.

Andreas Gevaert, Heart Centre, Jessa Hospital Campus Virga Jesse, Hasselt, Belgium; Research Group Cardiovascular Diseases, GENCOR Department, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium.

Evangelia Kouidi, Laboratory of Sports Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloníki, Greece.

Nicolle Kraenkel, Charité – University Medicine Berlin, Berlin, Germany; German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), Berlin, Germany.

Jari Laukkanen, Central Finland Health Care District Hospital District, Kuopio, Finland.

Francesco Maranta, Cardiac Rehabilitation Unit, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

Antonio Mazza, Department of Cardiac Rehabilitation, ICS Maugeri Care and Research Institute, Via S. Maugeri, 4, 27100 Pavia, Italy.

Miguel Mendes, Cardiology Department, CHLO-Hospital de Santa Cruz, Karnaxide, Portugal.

Daniel Neunhaeuserer, Sport and Exercise Medicine Division, Department of Medicine, University of Padova,Padova, Italy.

Josef Niebauer, University Institute of Sports Medicine, Prevention and Rehabilitation, Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Digital Health and Prevention, Salzburg, Austria.

Bruno Pavy, Cardiac Rehabilitation Department, Loire-Vendée-Océan Hospital, Machecoul, France.

Carlos Peña Gil, Department of Cardiology, Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, CV, SERGAS CIBER, IDIS, Santiago, Spain.

Bernhard Rauch, IHF - Institut für Herzinfarktforschung, Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Simona Sarzi Braga, Department of Cardiac Rehabilitation, ICS Maugeri Care and Research Institute, Tradate, Italy.

Maria Simonenko, Physiology Research and Blood Circulation Department, Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test SRL, Heart Transplantation Outpatient Department, Federal State Budgetary Institution, ‘V.A. Almazov National Medical Research Centre’ of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation.

Alain Cohen-Solal, Cardiology Department, Hopital Lariboisiere, UMRS-942, Paris University, Paris, France.

Marinella Sommaruga, Psychology Unit, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, IRCCS, Camaldoli Institute, Milano, Italy.

Elio Venturini, Cardiac Rehabilitation Unit, Azienda USL Toscana Nord-Ovest, Cecina Civil Hospital, Cecina, Italyand.

Carlo Vigorito, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy.

References

- 1. Larson AS, Savastano L, Kadirvel R, Kallmes DF. COVID-19 and the cerebro-cardiovascular systems: what do we know so far? J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. https://go.forrester.com/blogs/four-phases-of-the-coronavirus-pandemic/. (6 October 2020).

- 3. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, Wales PW. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ambrosetti M, Abreu A, Corrà U, Davos CH, Hansen D, Frederix I, Iliou MC, Pedretti RFE, Schmid J-P, Vigorito C, Voller H, Wilhelm M, Piepoli MF, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Berger T, Cohen-Solal A, Cornelissen V, Dendale P, Doehner W, Gaita D, Gevaert AB, Kemps H, Kraenkel N, Laukkanen J, Mendes M, Niebauer J, Simonenko M, Olsen Zwisler A-D. Secondary prevention through comprehensive cardiovascular rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. 2020 update. A position paper from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;2047487320913379. doi:10.1177/2047487320913379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abreu A, Frederix I, Dendale P, Janssen A, Doherty P, Piepoli MF, Völler H; on behalf of the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of EAPC Reviewers. Standardization and quality improvement of secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation programmes in Europe: the avenue towards an European Association of Preventive Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology accreditation programme: a position statement of the Secondary Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;2047487320924912. doi:10.1177/2047487320924912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. https://www.escardio.org/Sub-specialty-communities/European-Association-of-Preventive-Cardiology-(EAPC)/About/Secondary-Prevention-and-Rehabilitation-Section.

- 7. Hansen D, Dendale P, Coninx K, Vanhees L, Piepoli MF, Niebauer J, Cornelissen V, Pedretti R, Geurts E, Ruiz GR, Corrà U, Schmid J-P, Greco E, Davos CH, Edelmann F, Abreu A, Rauch B, Ambrosetti M, Braga SS, Barna O, Beckers P, Bussotti M, Fagard R, Faggiano P, Garcia-Porrero E, Kouidi E, Lamotte M, Neunhäuserer D, Reibis R, Spruit MA, Stettler C, Takken T, Tonoli C, Vigorito C, Völler H, Doherty P. The European Association of Preventive Cardiology Exercise Prescription in Everyday Practice and Rehabilitative Training (EXPERT) tool: a digital training and decision support system for optimized exercise prescription in cardiovascular disease. Concept, definitions and construction methodology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24:1017–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rahaghi FF, Baughman RP, Saketkoo LA, Sweiss NJ, Barney JB, Birring SS, Costabel U, Crouser ED, Drent M, Gerke AK, Grutters JC, Hamzeh NY, Huizar I, Ennis James W, Kalra S, Kullberg S, Li H, Lower EE, Maier LA, Mirsaeidi M, Müller-Quernheim J, Carmona Porquera EM, Samavati L, Valeyre D, Scholand MB. Delphi consensus recommendations for a treatment algorithm in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29:190146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1110187/coronavirus-incidence-europe-by-country/ (6 October 2020).

- 10. http://www.bacpr.com/resources/5F5_BACPR-BCS-BHF_COVID-19_joint_position_statement_final.pdf (6 October 2020).

- 11. Mureddu GF, Ambrosetti M, Venturini E, La Rovere MT, Mazza A, Pedretti R, Sarullo F, Fattirolli F, Faggiano P, Giallauria F, Vigorito C, Angelino E, Brazzo S, Ruzzolini M. Cardiac rehabilitation activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Position Paper of the AICPR (Italian Association of Clinical Cardiology, Prevention and Rehabilitation). Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2020;90:353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Réadaptation cardiaque en période épidémique de COVID-19: Propositions du GERS-P le 06/05/2020. https://sfcardio.fr/gers-p-group-exercice-r%C3%A9adaptation-sport-pr%C3%A9vention (6 October 2020).

- 13. Arrarte V y Campuzano R. Consideraciones sobre aplicabilidad de los consensos de expertos de unidades de insuficiencia cardiaca/rehabilitación cardiaca y RehaCtivAP con respecto al COVID-19. Suplementos Rev Esp Cardiol 2020; 20: 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kemps HMC, Brouwers RWM, Cramer MJ, Jorstad HT, de Kluiver EP, Kraaijenhagen RA, Kuijpers PMJC, van der Linde MR, de Melker E, Rodrigo SF, Spee RF, Sunamura M, Vromen T, Wittekoek ME; Committee for Cardiovascular Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology. Recommendations on how to provide cardiac rehabilitation services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neth Heart J 2020;28:387–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Recommendations on how to provide cardiac rehabilitation activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) 7 April 2020. https://www.escardio.org/Education/Practice-Tools/CVD-prevention-toolbox/recommendations-on-how-to-provide-cardiac-rehabilitation-activities-during-the-c (6 October 2020).

- 16. Scherrenberg M, Wilhelm M, Hansen D, Völler H, Cornelissen V, Frederix I, Kemps H, Dendale P. The future is now: a call for action for cardiac telerehabilitation in the COVID-19 pandemic from the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;2047487320939671. doi:10.1177/2047487320939671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mafham MM, Spata E, Goldacre R, Gair D, Curnow P, Bray M, Hollings S, Roebuck C, Gale CP, Mamas MA, Deanfield JE, de Belder MA, Luescher TF, Denwood T, Landray MJ, Emberson JR, Collins R, Morris EJA, Casadei B, Baigent C. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet 2020;S0140-6736(20)31356-8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salzwedel A, Jensen K, Rauch B, Doherty P, Metzendorf M-I, Hackbusch M, Völler H, Schmid J-P, Davoson CH. Effectiveness of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in coronary artery disease patients treated according to contemporary evidence based medicine: Update of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS-II). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;2047487320905719. doi:10.1177/2047487320905719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Faghy MA, Sylvester KP, Cooper BG, Hull JH. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the COVID-19 endemic phase. Br J Anaesth 2020;S0007-0912(20)30447-5. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]