Abstract

Nucleoside, nucleotide, and base analogs have been in the clinic for decades to treat both viral pathogens and neoplasms. More than 20% of patients on anticancer chemotherapy have been treated with one or more of these analogs. This review focuses on the chemical synthesis and biology of anticancer nucleoside, nucleotide, and base analogs that are FDA-approved and in clinical development since 2000. We highlight the cellular biology and clinical biology of analogs, drug resistance mechanisms, and compound specificity towards different cancer types. Furthermore, we explore analog syntheses as well as improved and scale-up syntheses. We conclude with a discussion on what might lie ahead for medicinal chemists, biologists, and physicians as they try to improve analog efficacy through prodrug strategies and drug combinations.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATION

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for 1 in 4 deaths annually. Importantly, cancer incidence continues to increase worldwide.1 Cancer encompasses a broad range of diseases in which host cells escape their normal cell cycle regulation. This phenomenon can be linked to several factors, including gender, ethnicity, age of onset, and lifestyle,2 but cancer can also be caused by cellular transformation linked to viral infection, chemical exposure, or radiation exposure, or the cause can be unknown (spontaneous) in nature.3–5 Advances in oncology treatments have increased the number of cancer survivors from 3 million in 1971 to more than 13 million in 2012.6 This has led to a 39% improvement in 5-year survival rates for different cancers and stages of disease as indicated by the 2010 data, and rates should continue to improve with recent advances in new therapies.1,7

The primary standard-of-care treatment for cancer includes surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immuno-therapy, and targeted therapy.1 Cutting-edge therapies may include one or more of these procedures listed above depending upon the type and stage of the cancer being treated. Sometimes surgery and radiation may be a second tier treatment, with chemotherapy being used first to reduce the tumor burden. Chemotherapies are divided into several main drug classes: alkylating agents,8 antimetabolites, anti-tumor antibiotics,9 topoisomerase inhibitors,10 mitotic inhibitors,11,12 and corticosteroids.13 Recently, antibodies directed against programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) protein, PD-1 ligands 1 and 2, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CLTA-4) have been found to activate the immune system to attack tumors, and they are therefore used with varying success to treat some types of cancer.14–16

Chemotherapeutic nucleoside, nucleotide, and base analogs, herein referred to as “nucleoside analogs”, are antimetabolites. They are chemically modified analogs of natural nucleosides, nucleotides, and bases, which are endogenous metabolites involved in many essential cellular processes, such as DNA and RNA synthesis, and purinergic signaling. Nucleoside analogs have been a cornerstone of anticancer and antiviral chemotherapy for decades. Currently, there are 15 FDA-approved nucleoside analogs used to treat various cancers, and they account for a large percentage of the current cancer chemotherapeutic arsenal.17 Whereas chemotherapeutic nucleoside analogs alone seldom lead to a cure for cancer, they do provide a valuable treatment option for cancer patients. In addition, many other nucleoside analogs are currently being investigated in clinical trials as monotherapy or combination therapy for multiple cancers. These studies attempt to increase the potency or bioavailability of these agents while diminishing associated dose-limiting toxicity.

In this review, we focus on both the biology and chemical syntheses of the current FDA-approved anticancer nucleoside analogs (Figure 1), investigational anticancer nucleoside analogs in development since 2000 or analogs used outside of the United States (Figure 2), and nucleoside analogs in development since 2000 that have stalled in clinical trials (Figure 3). Additionally, we present an overview of the cellular metabolism, the biochemical mode of action, and the types of cancers treated with these agents, as well as focusing on current methodologies for their chemical synthesis.

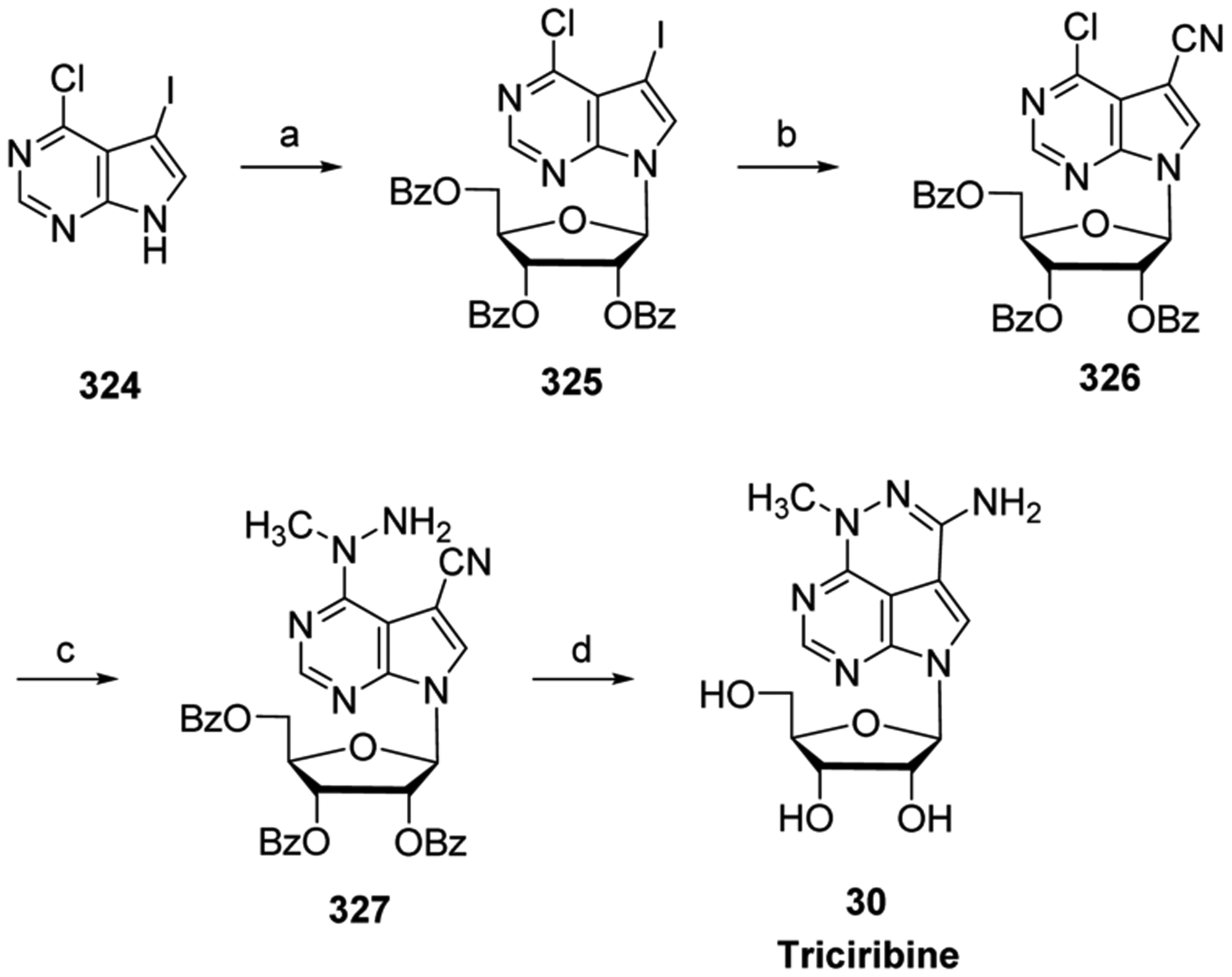

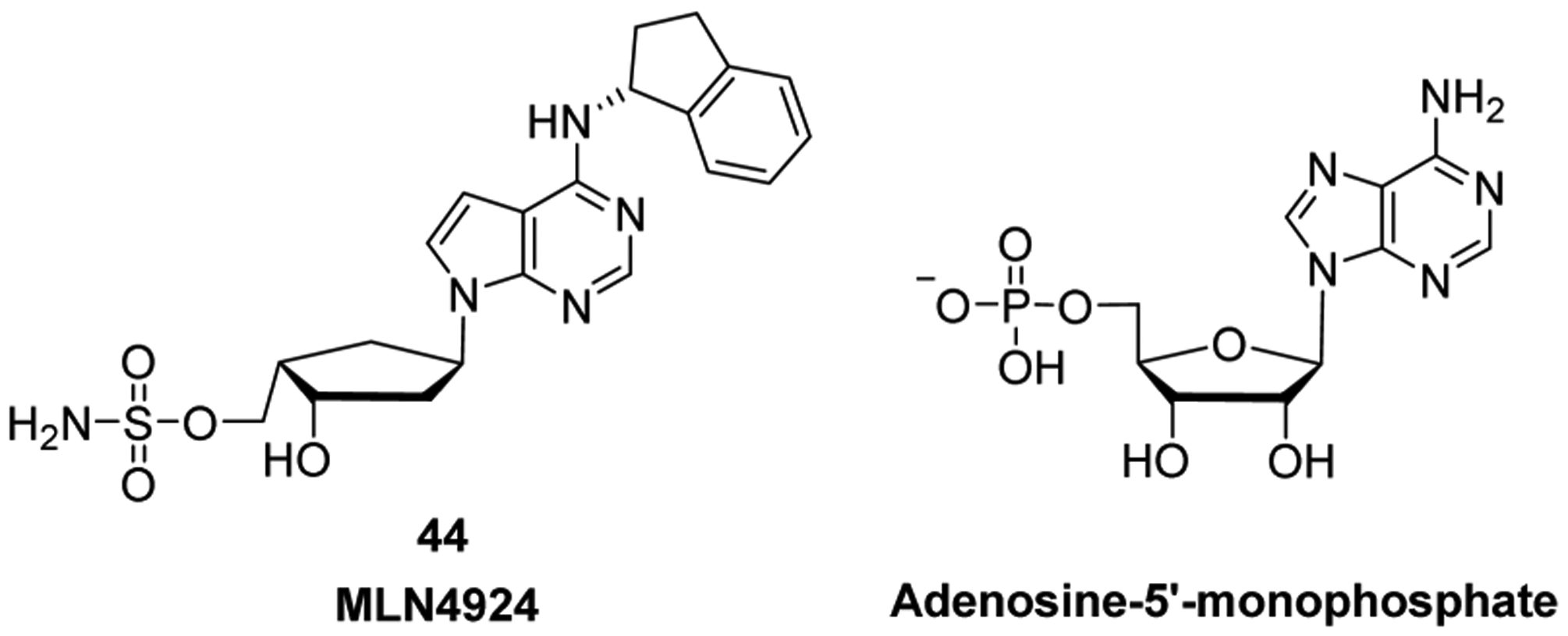

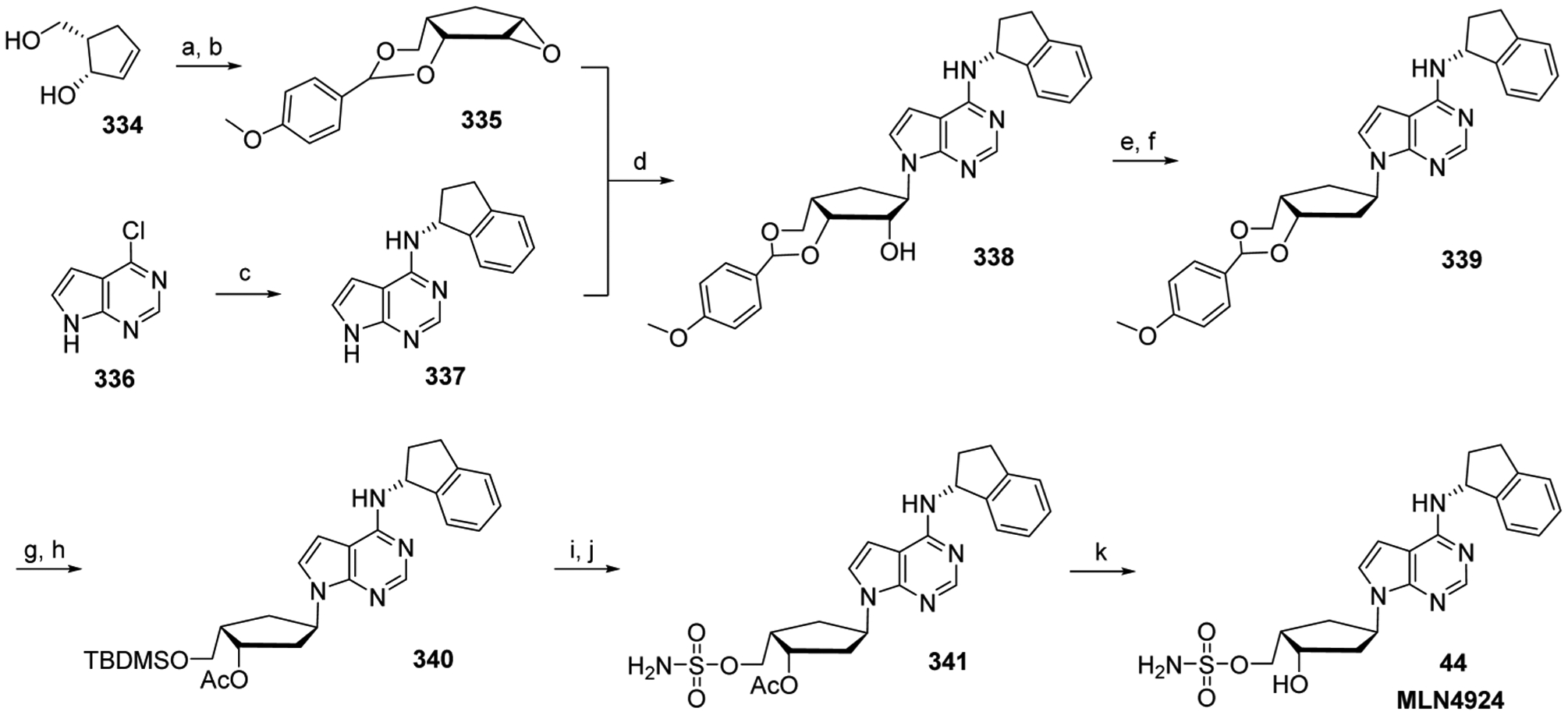

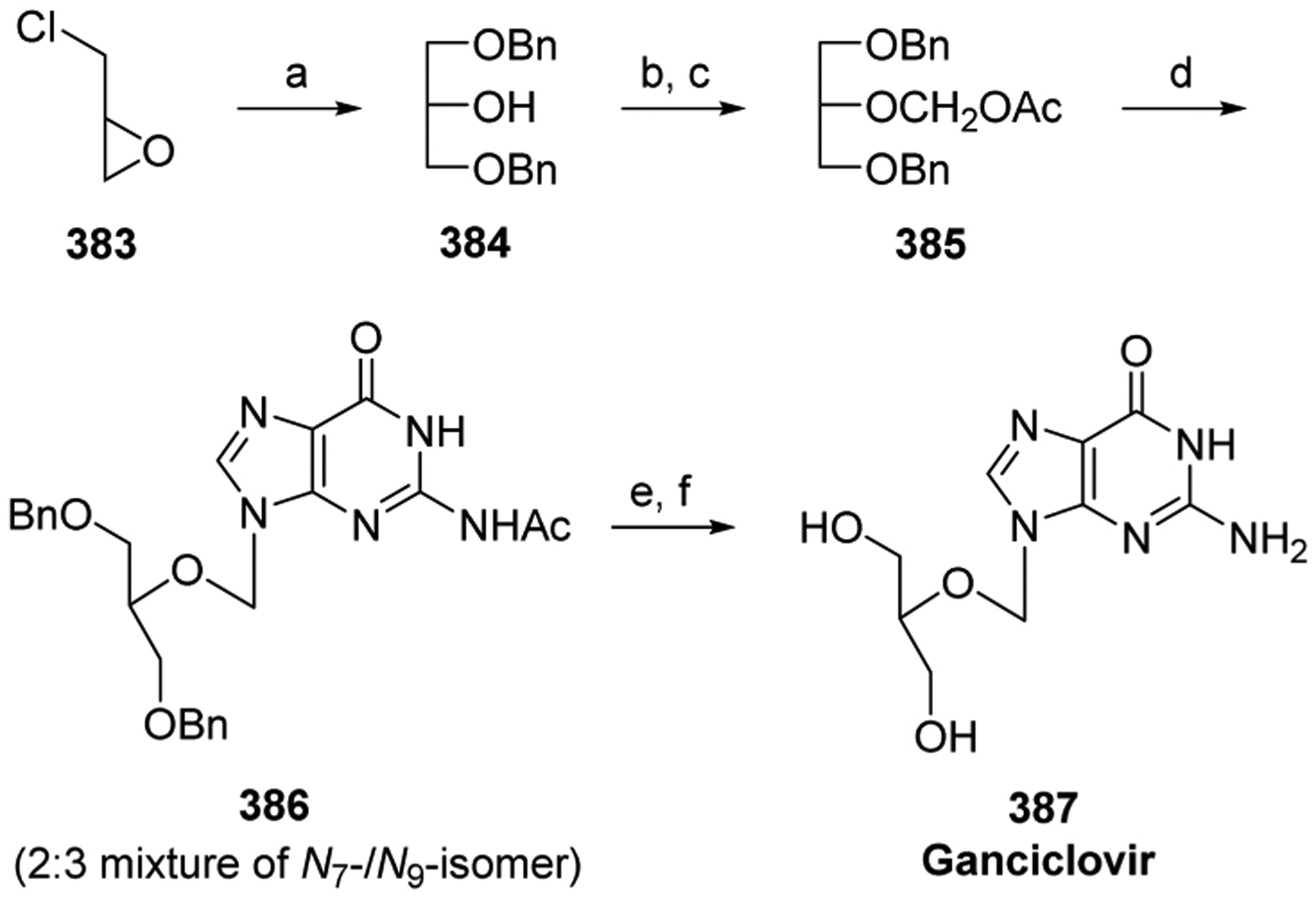

Figure 1.

FDA-approved anticancer nucleoside analogs.

Figure 2.

Various nucleoside analogs in clinical trials or used outside of the U.S.

Figure 3.

Various nucleoside analogs that have stalled in clinical trials.

2. GENERAL BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY OF ANTICANCER NUCLEOSIDE ANALOGS

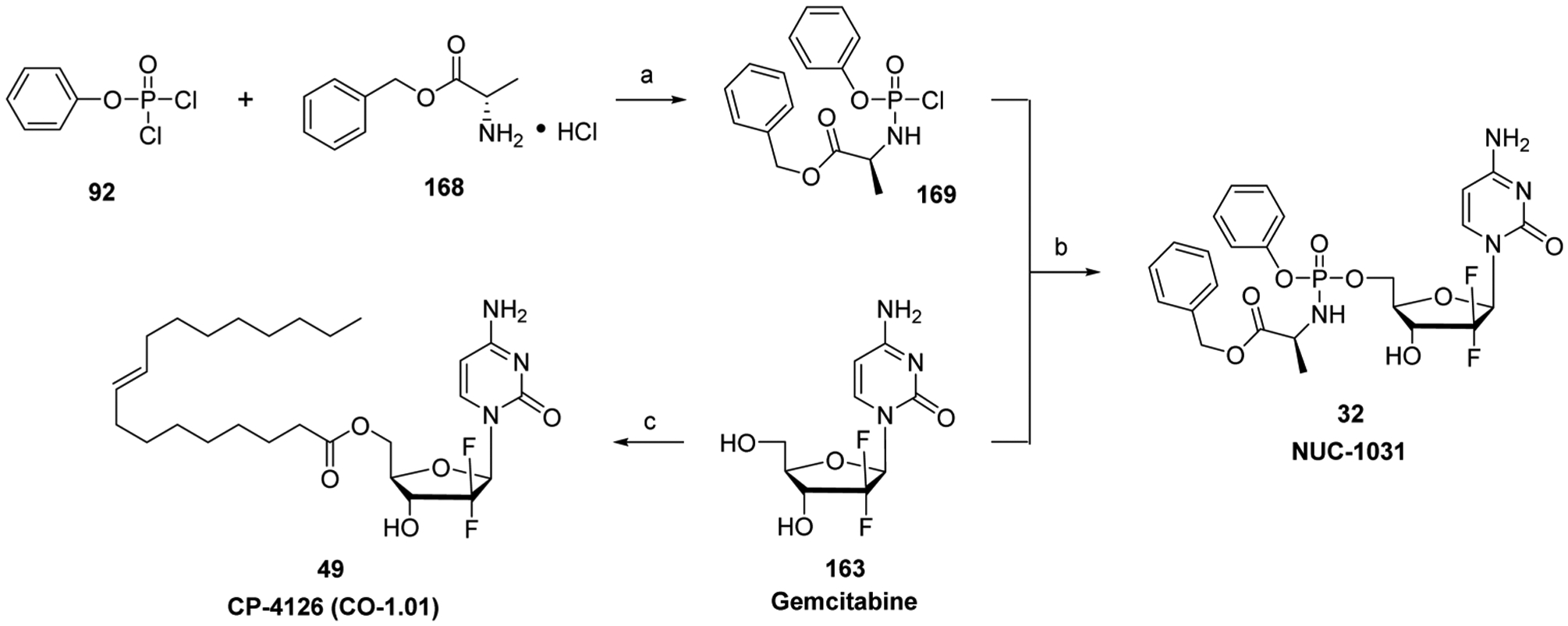

The two main routes for administering nucleoside analogs are by intravenously infusion and oral formulation. Once inside the body, the analogs can face a major bottleneck in cellular uptake. Both protein facilitated diffusion using either concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNT or SLC28; three members) and/or equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT or SLC29; four members) are involved in the cellular uptake for the majority of agents.18,19 Passive diffusion is limited in regard to cellular uptake for parent nucleoside analogs, with troxacitabine 48 being the exception, requiring very high extracellular concentrations in order to occur.20 Certain nucleoside analog prodrugs, such as NUC-1031 32, NUC-3373 37, or elacytarabine 51, however, can enter the cell independent of transporters.

Nucleoside analogs are prodrugs and require cellular metabolism to be converted to their active metabolites. This is accomplished by the cellular salvage pathway—a group of enzymes that can phosphorylate nucleoside and nucleotide substrates. After transport across the plasma membrane, nucleoside analogs undergo an initial phosphorylation—or if a base analog, ribosylation followed by phosphorylation—to generate nucleoside-5′-monophosphate forms,21 which is often the rate-limiting step within the cell in the process to generate active metabolites (Figure 4).22 The cell primarily uses four kinases for nucleoside-5′-monophosphate phosphorylation: 2′-deoxycytidine kinase, thymidine kinase 1, thymidine kinase 2, and deoxyguananine kinase.23 Each kinase has multiple substrates and can have feedback inhibition to regulate their activities.24,25 The initial phosphorylation is often performed by 2′-deoxycytidine kinase. Cancer cells usually express 2′-deoxycytidine kinase at a 3- to 5-fold higher protein level than most normal cells, affording some degree of selectivity.26 Phosphoramidate prodrugs such as NUC-1031 32 or NUC-3373 37, however, enter the cell as masked monophosphates and pass through a different enzymatic pathway in order to be converted to their nucleoside-5′-monophosphate forms.

Figure 4.

General biological mechanism of action of anticancer nucleoside analogs.

Nucleoside-5′-monophosphate analogs are converted to nucleoside-5′-diphosphate and nucleoside-5′-triphosphate forms by various cellular kinases. Nucleoside-5′-triphosphate analogs are substrates for DNA polymerases and can be incorporated into DNA during replication or DNA excision repair synthesis, which gives rise to stalled replication forks and chain termination. These events activate various DNA damage sensors, which stimulate DNA repair, halt cell progression, and often lead to apoptosis.27,28 Since most cancer cells replicate their genome more frequently than a majority of normal adult cells, which are quiescent and not actively synthesizing their DNA, this phenomenon allows for a degree of cancer cell selectivity.17 Moreover, certain nucleoside-5′-triphosphate analogs can be incorporated into RNA, leading to transcriptional termination, and messenger RNA (mRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) instability.29,30

Nucleoside and nucleotide (mono-, di-, or triphosphates) derivatives can also inhibit key cellular enzymes, providing a secondary mode of action that inhibits cell growth. Such enzymes include ribonucleotide reductase,31 which removes the 2′-OH group from the ribose sugar in order to generate de novo 2′-deoxyribonucleoside diphosphate,32 purine nucleoside phosphorylase,33,34 which is involved in purine metabolism catalyzing the reversible phosphorolysis of purine nucleosides,35 and thymidylate synthase,36 discussed below (see Section 5.1.1.1). A few newer nucleoside analogs, however, exert their anticancer activities as adenosine receptor antagonists, or by inhibiting cellular enzymes that are not involved in nucleic acid synthesis. These cellular enzymes include NEDD8-activating enzyme, which is involved in the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system and has an important role in cellular processes associated with cancer cell growth,37 and DOT1L (histone-lysine N-methyltransferase, H3 lysine-79 specific), which is involved in post-translational gene modification.38 Furthermore, the enzymatic activity of DOT1L represents an oncogenic driver of MLL-r leukemia.39

Enzymes that dephosphorylate nucleotides are also present in the cell. 5′-Nucleotidases (5′-NTs) can dephosphorylate noncyclic nucleoside-5′-monophosphates to nucleosides and inorganic phosphates, leading to the regulation of cellular nucleotide and nucleoside levels.40,41 There are seven intracellular 5′-NTs: cN-IA, cN-IB, cN-II, cN-III, cN-II-like, cdN, and mdN in the cell,42,43 and they have been reported to modulated antiviral and anticancer nucleotide levels.41 Their cellular functions involve cell–cell communication and signal transduction,44 as well as nucleic acid repair.45 Other enzymes involved in nucleotide degradation include eN (CD73), an ecto-5′-nucleotidase that converts AMP to adenosine plus phosphate,43 and ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (CD39), which can hydrolyze nucleoside-5′-triphosphates into nucleoside-5′-monophosphate and nucleoside-5′-diphosphate products. Tumor expression of these two enzymes, in an animal model, appears to enhance tumor growth by negatively regulating the immune response.46,47 Furthermore, alkaline phosphatases are also present and can be targets for anticancer treatment, but they might have a lesser impact on antimetabolite metabolism.48 Recently, a sterile alpha motif and histidine/aspartic acid domain containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) was discovered to be a dGTP/GTP-dependent deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase,49,50 generating 2′-deoxynucleosides and inorganic triphosphates from the cellular canonical 2′-deoxyribonucleoside-5′-triphosphates. Clofarabine-5′-triphosphate has been shown to be a substrate for SAMHD1.51 Furthermore, the SAMHD1 gene was shown to be mutated in CLL cancer,52 and the protein level downregulated in lung cancer.53

Cancer chemotherapy is limited in effectiveness by off target toxicity and drug resistance, with the latter leading to a decreased ability to deliver an adequate concentration of drug to cancer cells. Drug resistance can arise from pre-existing intrinsic properties of cancer cells or by acquired traits, which cancer cells develop in response to limited drug exposure.54 Cancer cells can acquire resistance to nucleoside analogs by several different mechanisms. First, many studies using cell lines exposed to nucleoside analogs have shown transporter mutations, which generally do not occur in cancer patients. Although a decrease in nucleoside transport in patients was detected, it was dependent on cell differentiation state: myeloblasts versus lymphoblasts.55,56 For example, high expression of hENT1 was a potential co-determinant of poor clinical response to 5-FU 2 in cells ex vivo from colorectal cancer patients,57 or using RNA1 to downregulate hENT1 in the pancreatic cell line.58 In contrast, high hENT1 expression was reported as a biomarker for survival in patients with pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine.59 Second, modulation of phosphorylating enzymes, such as 2′-deoxycytidine kinase, has been reported when using cancer cell lines.60 In patients, however, resistance to nucleoside analogs by phosphorylating enzymes has been reported to be linked to decreases in mRNA levels and a decrease in enzyme activity.61,62 Third, resistance to nucleoside analogs can also occur by augmentation of nucleotide excision repair machinery.63

An increase in cellular nucleopside analog efflux provides another mechanism of resistance.64 Cellular nucleoside analog efflux is performed by several ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters, such as ABCB1 (MDR1), ABCC4 (MRP4), ABCC5 (MRP5), and ABCC11 (MRP8).65,66 Furthermore, metabolic inactivation of nucleoside analogs can occur by the actions of cellular enzymes such as adenosine deaminase, cytidine deaminase, and purine nucleoside phosphorylase.67–69

3. GENERAL SYNTHETIC APPROACHES TO ANTICANCER NUCLEOSIDE ANALOGS

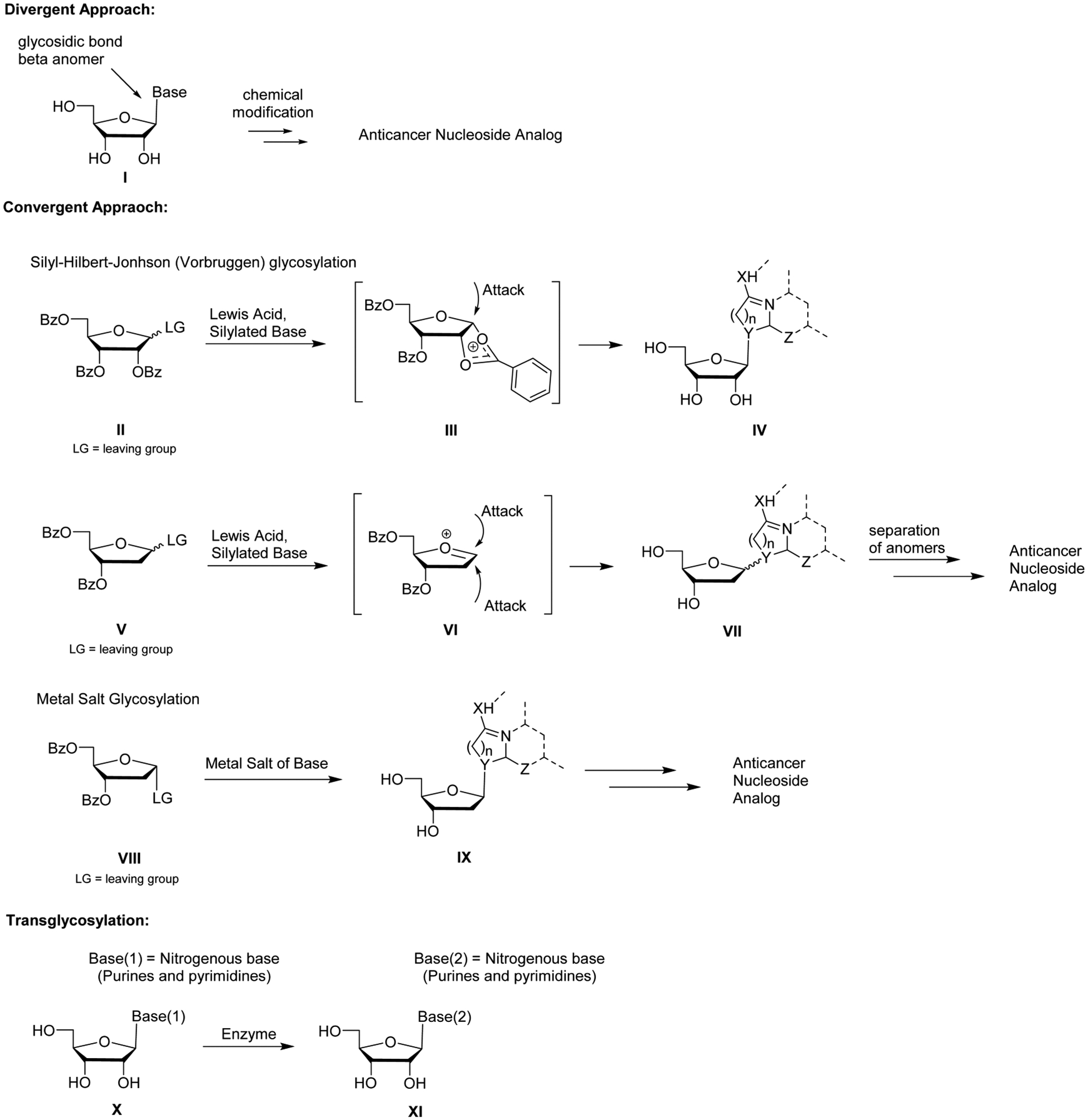

Syntheses highlighted in this review use three general approaches to access anticancer nucleoside analogs: divergent, convergent, and trans-glycosylation (Figure 5).70 The divergent approach begins with an intact nucleoside that is subsequently modified at either the sugar or base. A major advantage of this method is that the stereochemistry, especially of the key glycosidic bond (β-anomer), is already fixed. A drawback of this approach is the presence of two or three hydroxyl groups, which are relatively similar in chemical reactivity, and often require multiple protection/deprotection steps.

Figure 5.

General synthetic approaches to anticancer nucleoside analogs.

The convergent approach couples a nitrogenous base with a modified sugar in a glycosylation reaction. This method allows for more synthetic diversity, and it is more widely used, although the stereochemistry of the glycosylation can be an issue. The reaction is most often performed under Silyl–Hilbert–Johnson (Vorbrüggen) conditions or metal salt coupling conditions.

Benzoyl-protected furanose sugars are often used in glycosylations performed under Vorbrüggen conditions, because the stereochemistry of the glycosylation reaction is almost completely selective. Anchimeric assistance of the 2′-O-benzoyl group, protected furanose sugar II, leads to intermediate III, which effectively has its α-face blocked. This allows for selective formation of the protected β-anomer IV. Difficulties arise when dealing with 2′-deoxy furanose sugars. The absence of a 2′-O-benzoyl group precludes formation of an intermediate with a sterically hindered α-face, often leading to an anomeric mixture of products VII, and many times requires laborious chromatographic separation.

The metal salt glycosylation generally couples a furanose sugar possessing a leaving group (often halogens) with α-stereochemistry and a salt of a nitrogenous base. Conditions are sought to make the reaction predominantly (or exclusively if possible) SN2 in nature, in an attempt to elude anomerization of the leaving group or avoid the formation of an oxonium ion intermediate similar to VI, favoring a SN1-like reaction.

Enzyme-mediated base exchange is an addition method for nucleoside synthesis. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase or uridine phosphorylase can be used to replace one nucleoside base with another in a trans-glycosylation reaction. Overall, enzymes can selectively generate the desired β-anomer nucleoside.

4. PURINE AND ACYCLIC ANALOGS

4.1. Thiopurines

4.1.1. Thiopurines Biology.

In the early 1950s, Elion’s group, while at the Wellcome Research Laboratories, discovered that hypoxanthine and guanine substituted with sulfur at the 6 position led to purine synthesis inhibition, which in turn decreased growth of Lactobacillus casei.71 Subsequently, 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP, 1) and 6-thioguanine (6-TG, 3) were demonstrated to have potent anticancer activities against a wide variety of rodent tumors. The more promising 6-MP 1 was rapidly advanced into clinical trials; in 1953 it received FDA approval for treating pediatric acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), a rapid-developing cancer of the blood and bone marrow in which immature lymphocytes are overproduced.

Currently, 6-MP 1 and 6-TG 3 have various clinical applications. They can effectively treat hematologic cancers (childhood and adult leukemias).72 6-TG 3 is used to treat acute myelogenous leukemia, a cancer involving abnormal white blood cells of myeloid linage that rapidly divide and interfere with normal white blood cell production, whereas 6-MP 1 is used in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents and remains part of the standard of care for acute lymphocytic leukemia.73 These compounds are also being used to treat autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis,74–76 and they have also been employed to prevent solid organ transplant rejection.30,77,78

Thiobases require further metabolism by cellular enzymes to reach their active forms (Figure 6).79 6-MP 1 is converted by hypoxanthine/guanine phosphoribosyl transferase to 6-thioinosine-5′-monophosphate III and then converted to 6-thio-guanosine-5′-monophosphate VI, which is also the product of 6-TG 3 and hypoxanthine/guanine phosphoribosyl transferase. Further phosphorylation leads to 6-thio-guanosine-5′-triphosphate VIII, which can be incorporated into RNA.29 However, Nelson et al. have reported that 6-MP 1 activity was not directed toward specifically inhibiting RNA synthesis, suggesting that 6-MP-5′-triphosphate VIII incorporation into RNA was not a major mechanism for its anticancer activity in vitro.80

Figure 6.

Metabolism of 6-MP 1 and 6-TG 3.

A major active metabolite of both 6-MP 1 and 6-TG 3 is 6-thio-2′-deoxyguanosine-5′-triphosphate XI, which is produced from ribonucleotide reductase-mediated deoxygenation of 6-TG-5′-diphosphate VII, followed by phosphorylation.17 6-Thio-2′-deoxyguanosine-5′-triphosphate XI can be incorporated into DNA. DNA polymerases continue polymerization after 6-thio-2′-deoxyguanosine-5′-monophosphate incorporation, resulting in multiple thiobase derivatives embedded in the newly synthesized DNA strand. The reactive thiol group of the incorporated active metabolite is susceptible to nonenzymatic methylation, leading to incorporated 6-methylthioguanine-5′-monophosphate IX, which preferentially base-pairs with a thymine during DNA replication.81 The 6-methylthioguanine:-thymine base-pairings resemble DNA replication errors, which are recognized by cellular mismatch repair enzymes. It is hypothesized that 6-methylthioguanine:thymine base-pairing leads to a futile cycle of repair, which ultimately generates cytotoxic DNA damage.81

Another major active metabolite of 6-MP 1 is methylthioino-sine-5′-monophosphate IV, which is formed by the methylation of thioinosine-5′-monophosphate III by thiopurine S-methyltransferase.82 Metabolite IV inhibits phosphoribosylpyrophosphate (PRPP) amidotransferase, the first enzyme in the de novo purine biosynthesis pathway.83 PRPP amidotransferase inhibition leads to a decrease in purine nucleotide pools, which can disrupt DNA synthesis and repair, ultimately leading to cell death in vitro.84 6-Thioguanine-5′-monophosphate VI can also be methylated by S-methyltransferase to form methylthioguano-sine-5′-monophosphate IX. However, this metabolite is a weak inhibitor of PRPP amidotransferase.

Two enzymes involved in the detoxification of 6-MP 1 and 6-TG 3 are thiopurine methyltransferase and xanthine oxidase. The former directly methylates 6-MP 1 and 6-TG 3, to metabolites II and V, respectively. Xanthine oxidase catabolizes 6-MP 1 to the 6-thiouric acid derivative I. However, because xanthine oxidase expression is low in hematopoietic cells, thiopurine S-methylation is considered to be the predominant pathway of detoxification of 6-MP 1 and 6-TG 3.79 In addition, six different variant alleles have been identified from clinical samples that lead to lower thiopurine methyltransferase activity.79

Thiopurine resistance can arise due to the action of ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters. 6-MP-5′-monophosphate III and 6-TG-5′-monophosphate IV are substrates for ABC transporters: MRP4 and MRP5, for active transport out of cancer cells.85,86 Additional mechanisms of resistance identified using cell lines are the up regulation of P-glycoprotein87 and decreased hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase activity.88 A genomic approach revealed that overexpression of the ATM/p53/p21 pathway, overexpression of TNFRSF10D, and overexpression of CCNG2 may also contribute to thiopurine resistance in cell lines.89 Besides the natural mutations in thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene,79 mutations in NT5C2 transporter gene led to an increase in nucleotidase activity and resistance to 6-mercaptopurine 1 and 6-thioguanine 3 in ALL patients.90,91 Over 170 clinical trials evaluating thiopurines as a cancer treatment are listed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

4.1.2. Thiopurines Synthesis.

Elion and Hitchings reported the preparation of 6-MP 1 in 1952 (Scheme 1).92 For their studies, they developed a multigram-scale synthesis of hypoxanthine 57 starting from 4-amino-6-hydroxy-5-nitrosopyrimidine-2-thiol 54.93 The heterocycle 54 was reduced, dethiolated, and cyclized, forming 57, which was subsequently treated with P2S5, furnishing the desired 6-MP 1 Conversion of hypoxanthine 57 to 6-MP 1 using P2S5 has also been used in a recent process synthesis, which was done in toluene on a 200-g-scale with a yield of 93%.94 Additionally, this transformation has been effected on a gram-scale using the crystalline and storable P4S10-pyridine complex reagent 58.95

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 6-Mercaptopurine 1a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Na2S2O4, H2O, 60–70 °C, 80–85%; (b) Raney Ni, Na2CO3, H2O, reflux, 2 h then H2SO4, 88%; (c) HCO2H, reflux, 2 h then aq NaOH, AcOH, 93%; (d) P2S5, tetralin, 190–200 °C, 12 h, 40%; or 58, DMSO2, 165–170 °C, 85%.

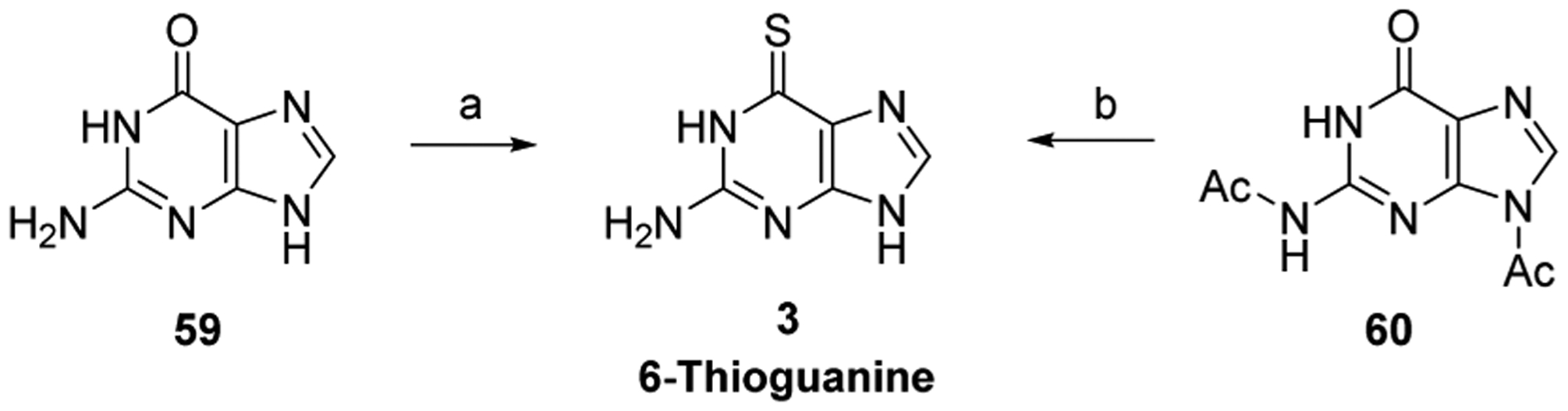

Elion and Hitchings synthesized 6-thioguanine (6-TG, 3) in 1954 (Scheme 2).96 Guanine 59 was converted to 6-TG 3 by treatment with P2S5 in refluxing pyridine. Diacylated guanine 60 has also been used to produce 3. Sulfuration with P2S5, followed by deprotection, furnished the product on 100-g-scale (Scheme 2).97 In addition, the sulfuration of 60 has been effected by treatment with Lawesson’s reagent.98

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 6-Thioguanine 3a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) P2S5, pyr, reflux, 2.5 h, 32%; (b) P2S5, pyridine hydrochloride, pyr, 110 °C, 4 h, then HCl, H2O, pH 4, recrystallization, 75%.

4.2. GS-9219

4.2.1. GS-9219 Biology.

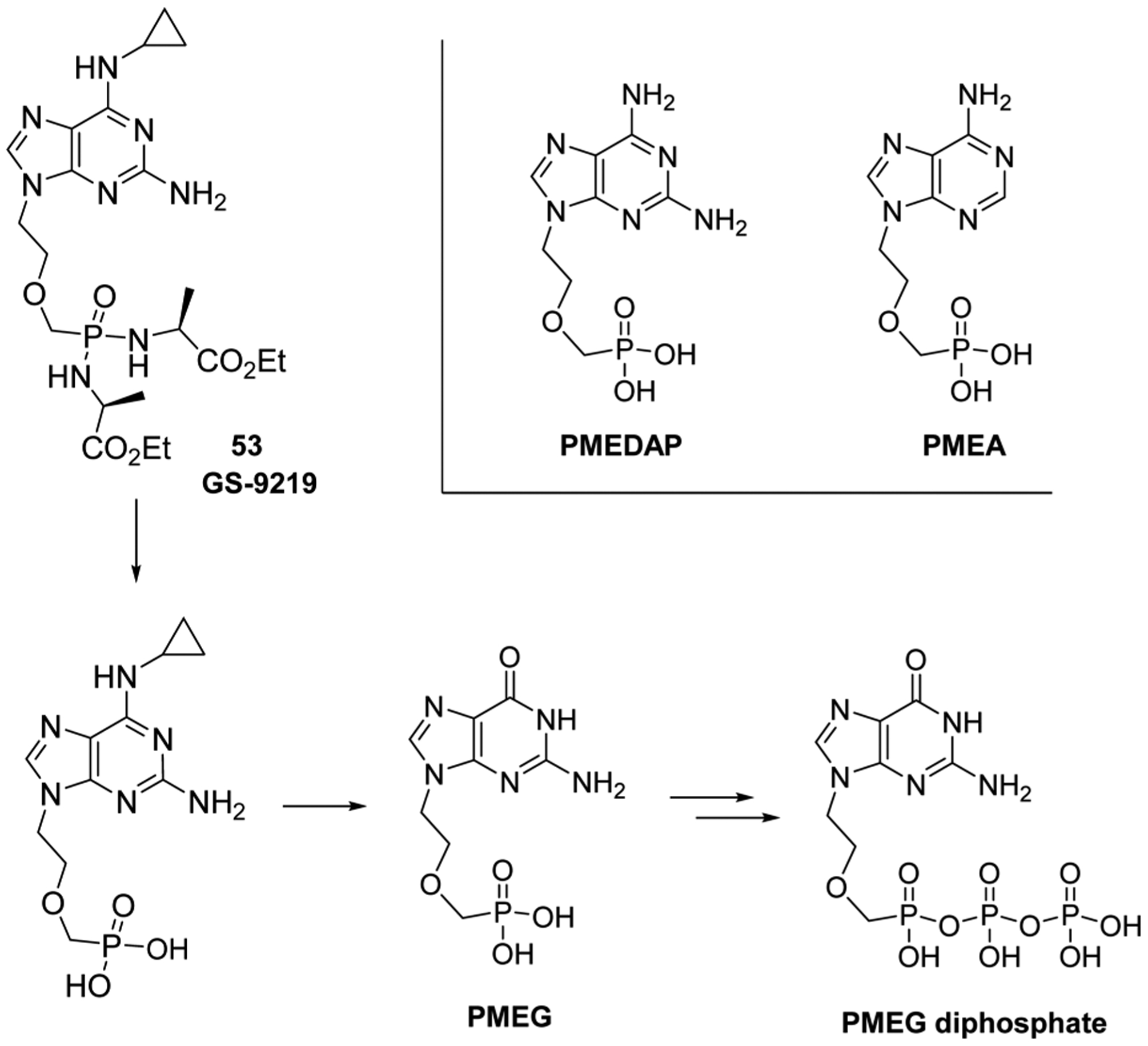

Several acyclic nucleotide derivatives, such as 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)guanine (PMEG), 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)-2,6-diaminopurine (PMEDAP), and 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA), display antiproliferative activities in cancer cells (Figure 7).99 The derivatives bear a phosphonate group, which is a bioisostere of a phosphate, but metabolically and chemically more stable.100 The acyclic nucleotide-5′-diphosphates are structural analogs of naturally occurring 2′-deoxyribonucleoside-5′-triphosphates and can be used as substrates for cellular DNA polymerases, acting as absolute chain terminators.101

Figure 7.

Structures of PMEG, PMEDAP, and PMEA, and proposed cellular metabolism of GS-9219 53.

PMEG has been shown to be the most cytotoxic among the acyclic derivatives studied.99 Within the cell, PMEG is converted to its diphosphate form, which is the active metabolite. The PMEG-5′-diphosphate potently inhibits DNA polymerases α, δ, and ε (DNA chromosomal replication enzymes), leading to inhibition of DNA synthesis and repair.102 The 3′ → 5′ exonuclease activity of DNA polymerase can remove PMEG incorporated during DNA synthesis.99 However, if not excised from the growing DNA strand, the PMEG-5′-monophosphate, which lacks a 3′-OH moiety, acts as an absolute DNA synthesis chain terminator.

Unfortunately, PMEG displays poor cellular permeability properties, in addition to kidney and gastrointestinal tract associated toxicities.102 Therefore, researchers at Gilead developed GS-9219 (53, VDC-1101), a double prodrug of PMEG, in an attempt to preferentially target lymphoid tissues.103 The N6-cyclopropyl moiety was installed to increase specific intracellular activation as well as decrease plasma exposure to the toxic PMEG. The phosphorodiamidate prodrug was installed to increase lymphoid cell and tissue loading efficacy. Such prodrugs are also often employed to increase compound solubility, cellular penetration, and selective tissue accumulation.104 GS-9219 53 showed potent antiproliferative activity against activated lymphocytes and hematopoietic cancer cells in vitro and in canines.103 It was proposed that GS-9219 53 is intracellularly converted to PMEG-5′-diphosphate in three steps: enzymatic hydrolysis of the amino acid of the prodrug (involving cathepsin A), deamination of the cyclopropyl amino moiety (involving N6-methyl-AMP-aminohydrolase), and phosphorylation of PMEG (Figure 7).105

Mutations in human adenosine deaminase-like proteins (H286R and S180N) have recently been found to promote resistance to GS-9219 53 and to 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)-N6-cyclopropyl-2,6-diaminopurine, an intermediate in the conversion pathway of GS-9219 53 to PMEG.106 Furthermore, point mutations in human guanylate kinase (S35N and V168F) were shown to promote GS-9219 resistance in cell lines.107

Unfortunately, GS-9219 53 has stalled in human clinical trials for treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic lymphoma, and multiple myeloma due to an unacceptable safety profile (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00499239—terminated—no results posted). However, the agent was FDA-approved for canine lymphoma in June 2013,108,109 and an additional Phase II study was done evaluating the effectiveness in canine cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.110 GS-343074 and GS-424044 are two additional prodrugs synthesized after GS-9219 53 and are being evaluated as anticancer prodrugs, particularly for canine cancers. No structures have been revealed for these two compounds.

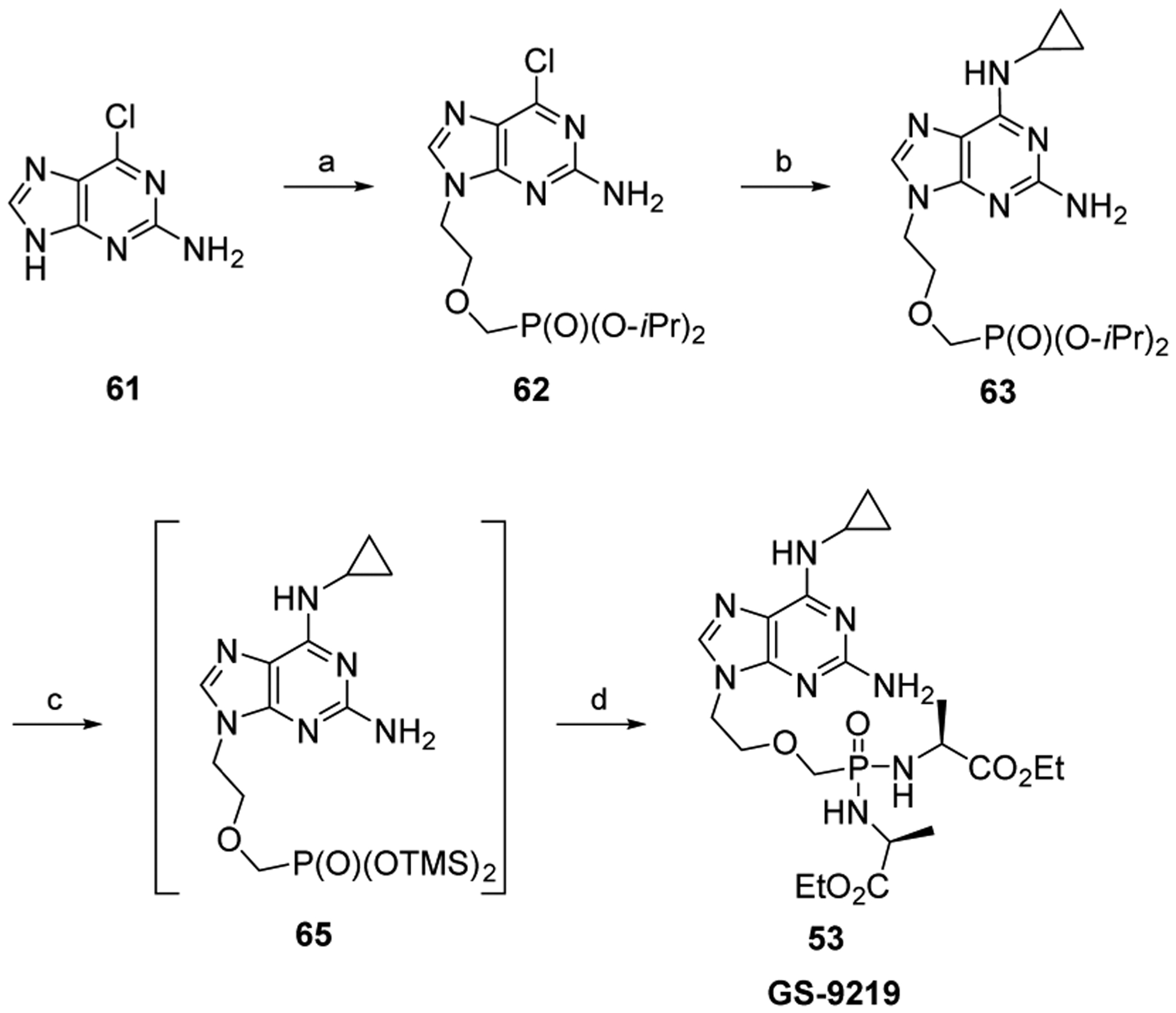

4.2.2. GS-9219 Synthesis.

In 2005, Gilead disclosed their discovery synthesis of GS-9219 53 (Scheme 3).111 2-Amino-6-chloropurine 61 was selectively N9-alkylated, and subsequent nucleophilic aromatic substitution with cyclopropylamine furnished alkyl diester 63. TMSBr-mediated deprotection led to the phosphonic acid derivative 64, which was sufficiently pure to require no chromatography after the reaction. Bis-amidate formation was effected by treatment of acid 64 with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, triphenylphosphine, and D-alanine ethyl ester HCl.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of GS-9219 53a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) HO(CH2)2OCH2PO(O-iPr)2, DIAD, PPh3, DMF, −15 °C to rt, 4 h, 63%; (b) cyclopropylamine, CH3CN, 100 °C, 4 h, 90%; (c) TMSBr, CH3CN, rt, overnight, 90%; (d) d-alanine ethyl ester HCl, 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, PPh3, Et3N, pyr, 60 °C, overnight, 50%.

Recently, Jansa et al. reported an improved route to bisamidate prodrugs.112 These researchers surmised that the intermediate 65 would react directly with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, triphenylphosphine, and the amino acid to produce the bisamidate (Scheme 4). This would obviate the need for the laborious purification step often needed to isolate and purity the intermediate diacid. The approach was successful and was used to synthesize GS-9219 53.113 TMS bromide-mediated deprotection of the phosphonate diester 63113 formed the bis(TMS)ester intermediate 65, maintained by strictly avoiding any contact with air. The bis(TMS)ester intermediate was then directly converted to GS-9219 53.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of GS-9219 53a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Cl(CH2)2OCH2P(O)(O-iPr)2, Cs2CO3, DMF, 80 °C, 8 h, 56%; (b) cyclopropylamine, EtOH, reflux, 3 h, 65%; (c) TMSBr, CH3CN, rt, overnight; (d) d-alanine ethyl ester, aldrithiol-2, PPh3, Et3N, pyr, 50 °C, 3 h, 92–98% (over two steps).

5. PYRIMIDINE ANALOGS

5.1. Fluorinated Pyrimidines

5.1.1. Fluorouracil (5-FU), Prodrugs, and Combinations Biologies.

5.1.1.1. Fluorouracil (5-FU) Biology.

In 1954, Rutman and colleagues observed that rat liver tumor cells utilized more uracil 18 as compared to normal liver cells.114 Thymidylate synthase can catalyze the conversion of deoxyuridine-5′-monophosphate to thymidine-5′-monophosphate using 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate as a methyl source. These observations led Heidelberger and colleagues to synthesize fluorouracil (5-FU, 2). Their hypothesis was that the 5-FU 2 would be converted to 5-fluorouracil-5′-monophosphate, and this product would selectively inhibit thymidylate synthase by forming a complex that could not breakdown due to prevention of elimination by the 5-fluorine (Figure 8).36,115 Furthermore, they surmised that this would selectively target tumor cells, since 5-FU-5′-monophosphate would be found at higher concentrations in these cells. Moreover, the inhibition of thymidylate synthase and subsequent decrease of thymidine would be deleterious for cancer cells growth.

Figure 8.

Complex of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate and thymidylate synthase with 5-FU-5′-monophosphate.

These researchers subsequently validated their hypothesis by showing that 5-FU 2 inhibited the production of thymine in vitro,36 and soon thereafter reported that the agent inhibited tumor growth in animals.116 Other reports have shown that the main mechanism of action for 5-FU 2 was the inhibition of synthesis,117 although RNA metabolism was also influenced.118

5-FU 2 is used as a palliative treatment for colorectal, head and neck, and breast cancers.119 Treatment can also include a biomodulator, such as leucovorin, which increases folate cofactors and the efficacy of 5-FU 2.120,121 Although introduced over 50 years ago, 5-FU 2 is still extensively studied, with over 2000 clinical trials listed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

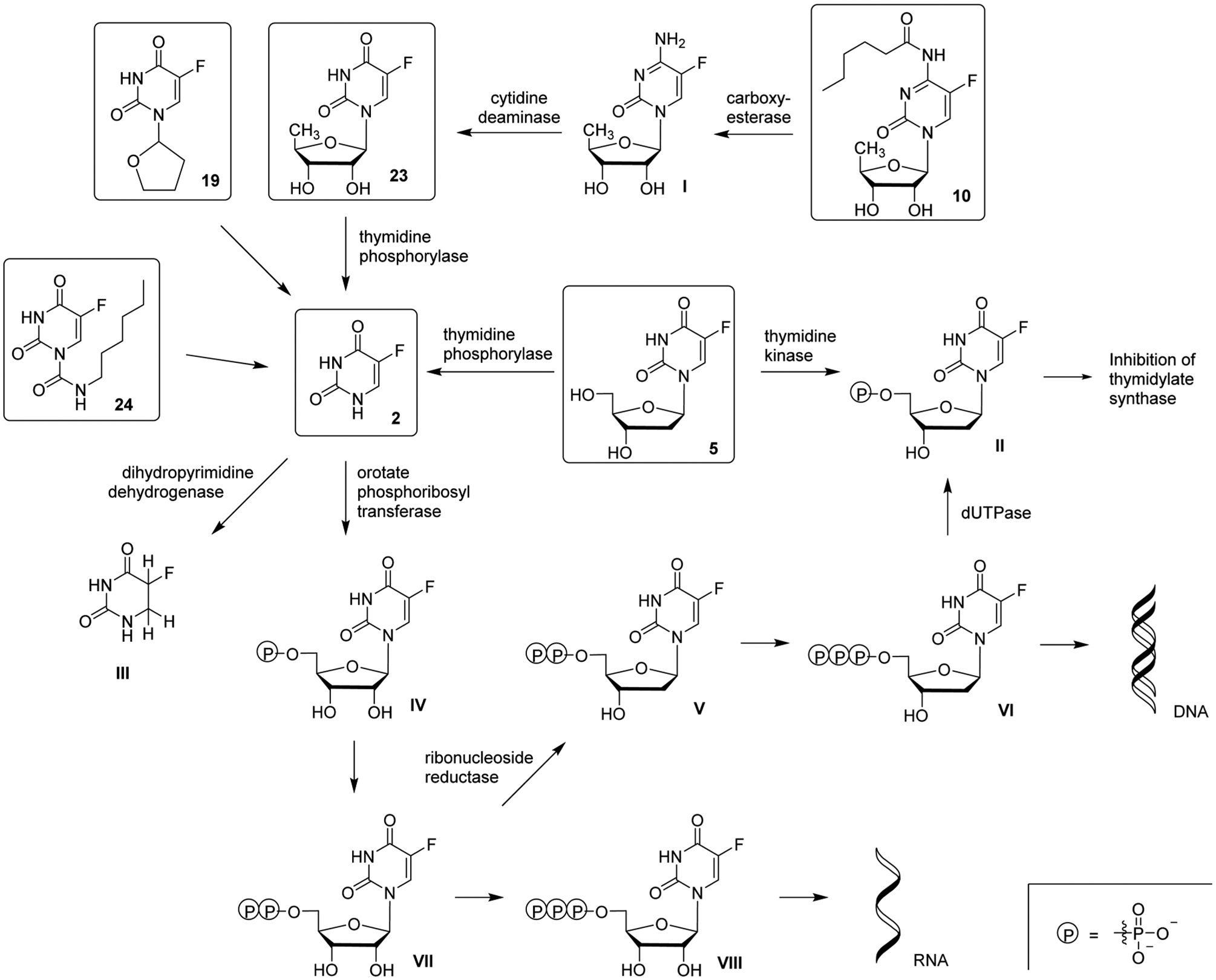

Mechanisms of action for 5-FU 2 are complex, and an overview of its metabolism is shown in Figure 9. The agent is administered by intravenous infusion and is rapidly eliminated from the plasma, having a half-life of 8–20 min.122 5-FU 2 enters the cell by facilitated transport,123 and subsequent ribosylation and phosphorylation occur by orotate phosphoribosyltransferase or in two steps via uridine phosphorylase and uridine kinase.119,124 Nucleotide kinases convert 5-FU-5′-monophosphate IV to the active metabolite 5-FU-5′-triphosphate VIII, which may be incorporated into many species of RNA. This leads to several levels of RNA disruption, including rRNA maturation inhibition101,125 and disruption of post-translational modifications of tRNAs,126 which can lead to cell death.

Figure 9.

Metabolism of 5-FU 2 and derivatives.

5-FU-5′-diphosphate VII is also a substrate of ribonucleotide reductase, resulting in 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-diphosphate generation. It is further phosphorylated to 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-triphosphate VI (an additional active metabolite), which then can be incorporated into DNA by cellular polymerases. 2′-Deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-monophosphate embedded into DNA does not act as a chain terminator or delayed chain terminator as compared to other antimetabolites. Instead, uracil glycosylase can excise the embedded 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-monophosphate from the DNA, or the activation of homologous recombination can occur.127 This apyrimidinic site is recognized by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 and can promote a DNA single-strand break.17 DNA repair enzymes recognize this break in the DNA, and a futile cycle of excision, repair, and nucleotide misincorporation ensues, which eventually causes cell death.

2′-Deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-triphosphate VI is converted by dUTPase to 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-monophosphate II, which then inhibits the enzyme thymidylate synthase. Inhibition of thymidylate synthase leads to a decrease in dTMP cellular concentration and an increase in dUMP concentration. As a result, less dTTP is available for DNA polymerases during DNA synthesis. This can promote the misincorporation of dUTP into newly synthesized DNA, which may result in the futile cycle mentioned above. Incorporation of dUTP into DNA has been shown to be mutagenic and promote genomic instability.128–130

There are several major obstacles for the effective use of 5-FU 2 as a chemotherapeutic. First, up to 80% of administered 5-FU 2 is catabolyzed by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, which is abundantly expressed in the liver and acts as an innate resistance mechanism. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase converts 5-FU 2 to dihydrofluorouracil III and is the rate-limiting enzyme in the catabolic pathway.122 Secondly, 2′deoxy-5-FU-5′-monophosphate and 5-FU-5′-monophosphate metabolites (II and IV) can be exported from cancer cells via the ABC transporters MRP5 and MRP8, limiting the therapeutic impact of this compound in vitro.131,132

Several mechanisms for 5-FU 2 resistance have been reported. The miRNA-320a has been shown to downregulate PDCD4 (programmed cell death protein 4) gene expression, thereby promoting 5-FU 2 resistance in vitro.133 Also, miRNA-21 induces resistance by regulating PTEN and PDCD4 levels in vitro, which correlate to cell survival and cell death pathways, respectively.134 Overexpression of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase is common in many cancer cell lines and has been linked to 5-FU 2 resistance by regulating nitric oxide production in vitro. Reducing reactive oxygen species leads to inactivation of the ASK1-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, leading to a reduction in 5-FU 2-induced apoptosis in vitro.135 Furthermore, putrescine released by macrophage has been shown to promote 5-FU 2 resistance in vitro, which might be important for regulating 5-FU 2 concentration in the microenvironment of solid tumors in vivo.136 Overall, 5-FU 2 resistance appears to be a multifactorial event which includes transport mechanisms, metabolism, molecular mechanisms, protection from apoptosis, and resistance via cell cycle kinetics.

In patients, 5-FU 2 resistance has been linked to thymidylate synthase methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, and thymidine phosphorylase, which influence 5-FU 2 metabolism.137,138 There have been over 1500 clinical trials performed that evaluated 5-FU 2 therapy listed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

5.1.1.2. Doxifluridine Biology.

5-FU 2 is administered intravenously due to the high level of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in the gut wall, which rapidly degrades the agent. Researchers at Roche used prodrug strategies to develop an orally available prodrug that overcomes degradation in the gut leading to enhanced absorption and an improved pharmacokinetic profile.139 This work led to the development of doxifluridine (5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine) 23, an orally available prodrug which is converted to 5-FU 2 in tumors by either thymidine phosphorylase or pyrimidine-nucleoside phosphorylase.140,141

High expression levels of pyrimidine-nucleoside phosphorylase have been reported for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer patients.142,143 Furthermore, thymidine phosphorylase is expressed at relatively high levels in tumor tissues such as esophageal, breast, cervical, pancreatic, and hepatic,144,145 which increase drug specificity. However, high thymidine phosphorylase expression is also found in the human intestinal tract. Therefore, doxifluridine treatment can result in dose-limiting toxicity (diarrhea) in some individuals.146 In addition, the most frequent adverse effects for doxifluridine 23 were neurotoxicity and mucositis, whereas leukopenia and nausea were reported for 5-FU 2 in patients.147 Several clinical trials have been done using doxifluridine 23 as a monotherapy or in combination therapy with mitomycin-C and cisplatin (administered intravenously).148

5.1.1.3. Capecitabine Biology.

As mentioned above, doxifluridine 23 treatment had gastrointestinal toxicity in patients. This led Roche to develop capecitabine 10 (5′-deoxy-5-fluoro-N-[(pentyloxy)carbonyl]cytidine), a third-generation prodrug of 5-FU 2 that was FDA-approved in 1998.149,150 Capecitabine 10 is almost 100% orally bioavailable and is not a substrate for thymidine phosphorylase.151 After passage through the intestinal mucosa, carboxylesterases in the liver cleave the N4-pentyl carbamate. Next, cytidine deaminase, in either the liver or tumor, catalyses the formation of doxifluridine 23, which is subsequently converted by thymidine phosphorylase to 5-FU 2.152 Capecitabine 10 was highly effective in HCT116 human cancer xenograft models and showed better selective tumor delivery as compared to either doxifluridine 23 or 5-FU 2.153 In addition, it was found that radiation therapy stimulated thymidine phosphorylase activity, and combination therapy with capecitabine 10 enhanced tumor cell selectivity.154

Drug resistance to capecitabine 10 appears to involve the interplay between dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase and thymidine phosphorylase, which are involved in the conversion of capecitabine 10 to 5-FU 2 and the degradation of 5-FU 2 within tumors.155 In addition to these resistance mechanisms, drug efflux is associated with gene polymorphisms of the ABCB1 transporter in patients.66

Currently, capecitabine 10 is FDA-approved for treatment of metastatic colorectal and breast cancers. Moreover, several clinical trials are underway using capecitabine 10 in combination therapy. A Phase II study for capecitabine 10 and bendamustine (DNA alkylating agent) in women with pretreated locally advanced or metastatic Her2-negative breast cancer (MBC-6) is being conducted (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01891227—active status—not recruiting patients). A Phase III study is being conducted that examines capecitabine 10 maintenance therapy following treatment with capecitabine 10 in combination with docetaxel (an antimitotic taxane) in treatment of mBC (CAMELLIA study) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01917279—recruiting patients). Capecitabine 10 is also being evaluated as a follow up therapy for efficacy of capecitabine 10 metronomic chemotherapy to triple-negative breast cancer (SYSUCC-001 study) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01112826—recruiting patients). It is also under examination for maintenance therapy: a Phase II study of maintenance capecitabine 10 to treat resectable colorectal cancer (CAMCO study) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01880658—recruiting patients).

5.1.1.4. NUC-3373 Biology.

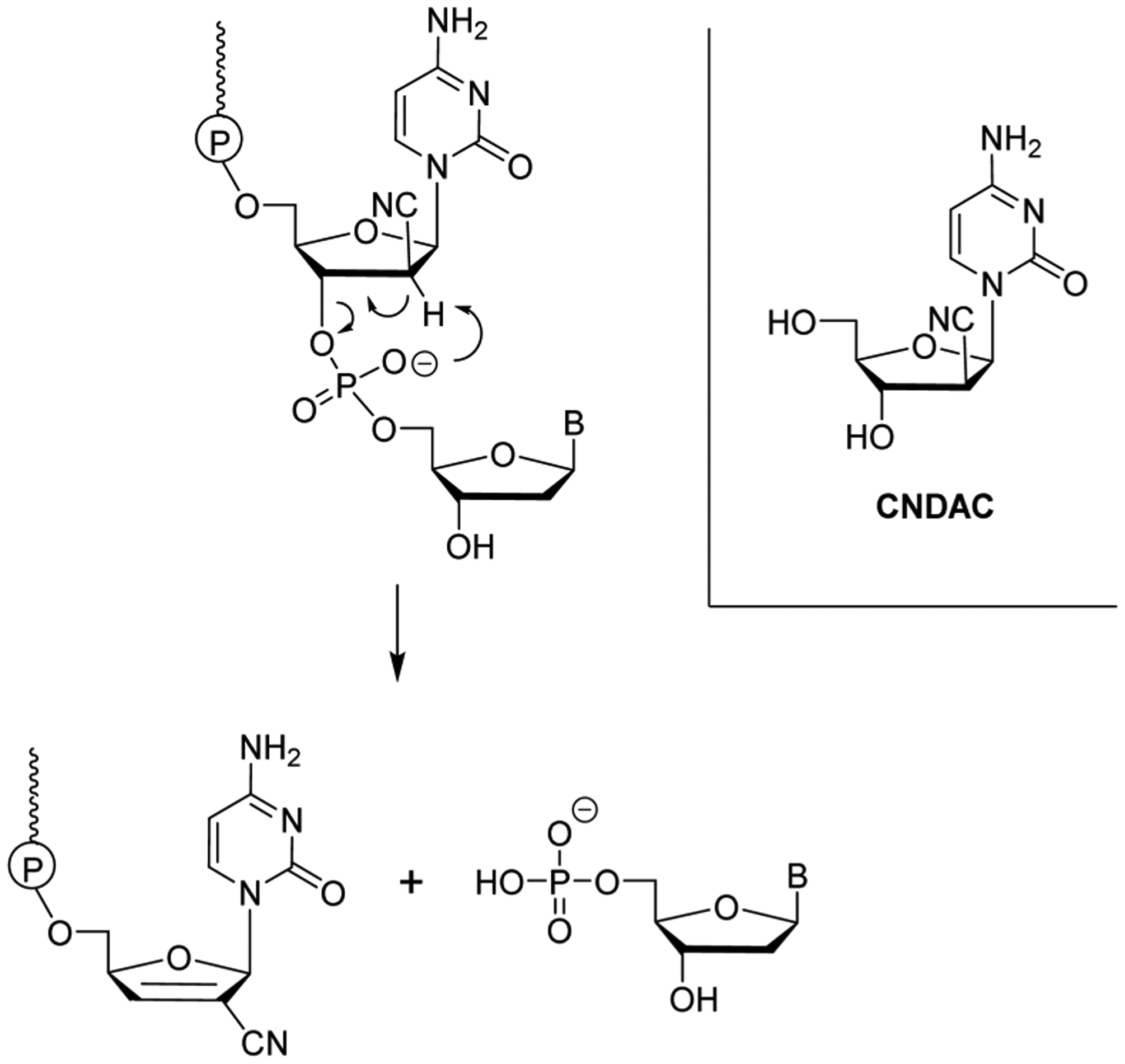

In 2011 a novel 5-FU 2 prodrug NUC-3373 37 (aka. NUC-3073 and FUDR) was reported having potent anticancer activity in vitro.156,157 NUC-3373 37, a phosphoramidate prodrug of floxuridine 5, was shown to be resistant to thymidine phosphorylase activity, and showed (in comparison to 5) a significantly decreased loss of potency in CEM cells deficient in hENT1 transporters.157 The authors also proposed a mechanism for the prodrug decomposition sequence including enzyme-mediated carboxyl ester hydrolysis, spontaneous cyclization with concomitant loss of the aryloxy leaving group, water-mediated opening of the mixed anhydride, and phosphoramidase-mediated P–N bond cleavage, resulting in 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-monophosphate II (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism for phosphoramidate decomposition of NUC-3373 37.

NUC-3373 37 is a mixture of phosphoramidate diastereomers, and it has been shown to have many impressive prodrug attributes, overcoming the major 5-FU 2 resistance mechanisms. The agent retains activity in thymidine kinase deficient cells, is resistant to thymidine phosphorylase activity, and maintains activity in hENT1 deficient cells by entering independently of nucleoside transporters. It is resistant to dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase catabolism, shows lower toxicity than 5-FU 2 in a variety of cell lines, and achieves high intracellular levels of 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-monophosphate II. Furthermore, the agent rapidly distributes to tissues following bolus infusion, shows low plasma levels of degradation metabolites, and reduces tumor weigh in HT29 colorectal xenografts significantly more than 5-FU 2.157 This impressive profile has led to NUC-3373 37 entering a Phase I clinical trial in late 2015 for treatment of advanced solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02723240—recruiting patients).

5.1.1.5. Floxuridine and 5′-Fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine with Tetrahydrouridine Biologies.

The National Cancer Institute was an early developer of floxuridine 5 (5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine, FdUrd), which has been reported to be 10–100 times more effective at inhibiting tumor cell proliferation in vitro than 5-FU 2.158 Floxuridine 5 gained FDA approval in 1970, and was marketed by Roche.159 It is approved, but not widely used, for colon and colorectal cancers that have metastasized to the liver, kidney, and stomach.160

Floxuridine 5 is a hydrophilic compound, and is likely transported into cells by pyrimidine nucleoside transporters.161 Thymidine kinase converts floxuridine 5 to floxuridine-5′-monophosphate II, which, as mentioned above, inhibits thymidylate synthase (Figure 9).

In the intestine, a significant amount of floxuridine 5 is converted to 5-FU 2 by thymidine phosphorylase. Therefore, hepatic arterial infusion has been employed to bypass the intestine and deliver more intact floxuridine 5 to the liver.162 Furthermore, the agent exhibits two properties associated with drugs that are best fit for hepatic arterial infusion: a high hepatic extraction and a short plasma half-life.160 These properties can lead to increased hepatic levels of floxuridine 5 and decreased systemic levels of the compound, which can decrease overall toxicity. This procedure has shown improvements for floxuridine 5 treatment for colorectal cancers.163–165

Several mechanisms of floxuridine resistance have been reported. Studies have shown a decrease in orotate phosphoribosyltransferase activity and thymidine kinase activity in vitro, as well as an increase of thymidylate synthase mRNA expression in vitro.166 In patients, an increase in thymidylate synthase levels has been correlated with floxuridine resistance.167

Several clinical trials that include floxuridine 5 are currently underway. These include hepatic arterial infusion with floxuridine 5 and the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive steroid derivative dexamethasone (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01862315—recruiting patients). Another trial examines hepatic arterial infusion with floxuridine 5 and dexamethasone in combination with gemcitabine hydrochloride 9 or the antiangiogenic monoclonal antibody bevacizumab (ClinicalTrials. gov identifiers: NCT01938729—recruiting patients and NCT00200200—active status—not yet recruiting patients). Recent results from a Phase I trial using floxuridine 5 with modified oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil 2, and leucovorin (m-FOLFOX6) were reported.164

A major problem for anticancer cytidine analogs (gemcitabine, cytarabine 4, azacytidine 11, decitabine 14, capecitabine 10, and 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine 38) is that they are substrates for cytidine deaminase and can be rapidly converted to uridine analogs, which are often inactive metabolites.168 For example, the liver expresses high levels of cytidine deaminase that provide a microenvironment to protect cancer cells from decitabine 14 treatment.169 In attempts to overcome the problem of deamination, cytidine deaminase inhibitors, tetrahydrouridine (39, NSC-112907) and (4R)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrouridine (Figure 11), are being investigated with nucleoside analogs as potential combination therapies.

Figure 11.

Structures of tetrahydrouridine 39 and (4R)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrouridine.

Tetrahydrouridine 39 has been investigated since the 1970s and been evaluated in cell lines and mice with cytarabine 4, gemcitabine, azacytidine (11, and decitabine 14.170–174 How ever, clinical data has shown that patients with the cytidine deaminase gene G208A polymorphism had several adverse reactions to gemcitabine treatment.175,176 In addition, the cytidine deaminase gene K27Q polymorphism promotes greater catalytic activity toward deoxycytine and cytarabine 4.177 Collectively, these data suggest prescreening patients for polymorphisms would be helpful in guiding treatment options.

Currently 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (FdCyd, 38) is being studied in combination with tetrahydrouridine 39 in mice.168,174 Coadministration of 38 with tetrahydrouridine 39 led to higher levels of FdCyd-5′-monophosphate, produced by 2′-deoxycyti-dine kinase in mice.178 Once in the cell, FdCyd 38 can be converted to FdUrd by the action of cytidine deaminase, and subsequently, phosphorylation leads to FdUrd-5′-monophosphate, which inhibits thymidylate synthase. Furthermore, FdCyd-5′-monophosphate can be phosphorylated to FdCyd-5′-triphosphate and incorporated into DNA. Once incorporated into DNA, FdCyd 38 has been shown to inhibit DNA methyltransferase with comparable activity to azacytidine 11 (see Section 5.2.1).179 Therefore, FdCyd 38 exposure can lead to the following direct and indirect cytotoxic activities in cells: (1) FdCyd-5′-monophosphate inhibition of DNA methylation, (2) 2′-deoxyribose-5-FU-5′-monophosphate II inhibition of thymidylate synthase, and (3) 2′-deoxy-5-FU-5′-triphosphate VI and 5-FU-5′-triphosphate VIII incorporation into DNA and RNA, respectively.180

Both preclinical and clinical trials are currently underway using FdCyd 38 with tetrahydrouridine 39. In 2016, a preclinical evaluation of FdCyd 38 and tetrahydrouridine 39 in pediatric brain tumors was reported,181 and a methods development report was published evaluating a combination treatment of tetrahydrouridine 39 and FdCyd 38 from human serum using HPLC-MS analysis.182 In 2015, Newman et al. reported a Phase I trial that examined the toxicity, plasma exposures, peak response, and dosing for the two compounds.183 Additional clinical studies are underway for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancer, and solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00978250—recruiting patients and NCT01534598—recruiting patients). Recently, the oral and intravenous pharmacokinetics of FdCyd 38 and tetrahydrouridine 39 were reported for cynomolgus monkeys and humans trial.184

(4R)-2′-Deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrouridine is a newer cytidine deaminase inhibitor being evaluated in preclinical studies.185 The agent has an IC50 of 0.4 μM for cytidine deaminase and exhibited enhanced acid stability at its N-glycosyl bond as compared to tetrahydrouridine 39. Rhesus monkeys cotreated with (4R)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrouridine and decitabine 14 had higher detectable levels of 14 in the serum.

5.1.1.6. Tegafur-Uracil, TS-1, Carmofur, and Flucytosine Biologies.

Tegafur 19, TS-1, carmofur 24, and flucytosine 31 are other examples of prodrugs of 5-FU 2 (Figure 9). The tegafururacil combination, TS-1 (a triple drug combo including tegafur 19, chloro dihydropyridine 20, and potassium oxonate 21), and carmofur (24, mifurol), are used globally in cancer treatments.186 In 1983, tegafur–uracil (18 + 19) was approved for use in Japan. The orally bioavailable combination is given in a 4:1 mol ratio of tegafur 19 and uracil 18. Tegafur 19 is metabolized to 5-FU 2, which can be converted to the inactive dihydrofluorouracil mainly by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in the liver.187 The coadministration of uracil 18 inhibits this enzyme, thus helping maintain high levels of 5-FU 2 in the liver and in the circulation. Tegafur-uracil (18 + 19) is approved in Japan and Taiwan for various advanced gastrointestinal cancers. Patients are still being recruited for a Phase II clinical trial using metronomic therapy with tegafur–uracil (18 + 19) to treat head and neck cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00855881—recruiting patients). While a Phase II study in combination with sorafenib (kinase inhibitor) for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma has been terminated in Jan 2015, with no results posted (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01539018—terminated in 2015—no results posted).

TS-1 includes tegafur 19, chlorodihydropyridine (gimeracil) 20, and potassium oxonate 21 used in a respective molar ratio of 1:0.4:1.188 TS-1 (19 + 20 + 21) is an orally administered triple combination drug regiment, which was approved in Japan in 1999. Chlorodihydropyridine 20 is a more potent inhibitor of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase than uracil 18.188,189 Potassium oxonate 21 may decrease gastrointestinal toxicity by selectively inhibiting 5-FU 2 activity within the intestinal lumen. TS-1 (19 + 20 + 21) is approved for use and is currently undergoing multiple clinical trials. Some of these studies include coadministration with cisplatin (DNA alkylating agent) for treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cell cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01874678—completed status—with no results), a Phase II study for combination treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with the DNA alkylating agent oxaliplatin (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01429961–unknown status–no updates for 2 years), and a Phase II study for monotherapy treatment of advanced metastatic breast cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01492543—unknown status—no updates for 2 years). In addition, Phase I clinical studies using combination therapy of TS-1 (19 + 20 + 21) and TAS-114, a first-in-class dual inhibitor of dUTPase (deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate nucleotide hydro-lase) and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase,190 is being conducted (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01610479—active status—not recruiting).

Product marketing for carmofur 24 started in 1981. Carmofur 24 is a lipophilic-masked analog of 5-FU 2 that can be administered orally. The carbamoyl moiety of the drug is removed in vivo to release 5-FU 2. Carmofur 24 has been used to treat colorectal cancer in China, Japan, and Finland for many years.186 However, the agent has been shown to induce delayed leukoencephalopathy, characterized by progressive damage to white matter in the brain with stroke-like symptoms.191–193 There are currently no open clinical trials for this agent. A trial treating patients with stage II hepatocellular carcinoma was suspended prematurely, because 56% of the treated patients had unacceptable side effects and offered no survival advantage for certain cancers in stage 1 and 2 of the disease.194 This may be a reason why carmofur 24 was never pursued for FDA-approval in the US.

Flucytosine 31 is another prodrug of 5-FU 2 in clinical trials. It is converted to 5-FU 2 by cytosine deaminase, which is not encoded by the human genome. Therefore, flucytosine 31 is used in combination with gene therapy of cancer cells in an attempt to have drug-specific targeting.195 Engineered mesenchymal stromal cells have been examined to convert flucytosine 31 into its active compound,196 and modified neural stem cells are currently being tested for the same purpose (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02015819—recruiting status, and NCT01172964—completed status—no results posted). Flucytosine 31 is currently in a Phase I/II clinical trial in combination with maltose and APS001F, a recombinant anaerobic bacteria Bifidobacterium engineered to express the cytosine deaminase gene, for treatment of solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01562626—recruiting status).

The progression of fluoropyrimidine analogs shows the importance of a biological observation–chemical modification interplay. The intravenously-administered 5-FU 2 and floxuridine 5 was followed by the orally-bioavailable carmofur 24 and flucytosine 31. The next step in the progression involved drug combinations TS-1 (19 + 20 + 21), tegafur–uracil (18 +19), and the recently FDA-approved TAS-102 (15 and 16), in order to decrease 5-FU 2 degradation. Further chemical modifications led to double (doxifluridine 23) and triple (capecitabine 10) prodrugs, which showed improvement in toxicity and pharmacokinetics profiles. Currently, NUC-3373 37 appears to overcome both innate and drug-derived resistance mechanisms. Newer analogs could be used as combination therapy with DNA damaging agents such as mitomycin-C and cisplatin, and immunotherapies—antiCTLA-4 and anti-PD-1, to improve patient survival rates.

5.1.2. Fluorouracil (5-FU), Fluorouracil Prodrugs, and Combinations Syntheses.

5.1.2.1. Fluorouracil (5-FU) Synthesis.

In 1957, a synthesis of 5-FU 2 was reported in which the compound was prepared from pseudourea salts and α-fluoro-β-keto ester enolates.197–199 Twenty years later, Robins et al. reported a two-step synthesis of 5-FU 2 from uracil 18 (Scheme 5).200 Trifluoromethyl hypofluorite was used to introduce a fluorine atom into the uracil ring, and the resulting fluorinated adduct 66 underwent base-catalyzed elimination of MeOH, generating 5-fluoro-pyrimidine 2. An alternative synthesis used the cheap and readily available ortic acid (vitamin B13, 67) as the starting material.201 Fluorination of 67 with fluorine gas and trifluoroacetic acid furnished acid 68, which in turn was decarboxylated to produce 5-FU 2 on a gram-scale.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Fluorouracil 2a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) CF3OF/CCl3F, MeOH, −78 °C, 5 min; (b) Et3N, MeOH, H2O, rt, 11 min, 90% (over two steps); (c) F2 (g), TFA, 0 °C to 10 °C, 3 h, 80%; (d) triethyleneglycol dimethyl ether, 130 °C to 200 °C, 20 min, 90%.

Baasner et al. reported a 100-g-scale preparation of 5-FU 2.202 This procedure used selective fluorine/chlorine exchange and chlorine hydrogenolysis reactions (Scheme 6). Tetrafluoropyr-imidine 72, which can be prepared in four steps from urea 69 and diethylmalonate 70 via 2,4,5-trichloropyrimidine 71, was treated with HCl gas forming the dichlorinated intermediate 73. Dechlorination by selective palladium-catalyzed hydrogenolysis was followed by hydrolysis with aqueous sodium hydroxide to complete the synthesis.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of Fluorouracil 2a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Na, MeOH; (b) POCl3, PhNMe2; (c) proton sponge hydrofluoride; (d) NaF, F2, CFCl3; (e) HCl (g), 160 °C, 4 h, 38%; (f) Pd/C, H2, Et3N, EtOAc, 3.5 h, 82%; (g) aq NaOH, 80 °C, 4 h, 93%.

5.1.2.2. Doxifluridine and Capecitabine Syntheses.

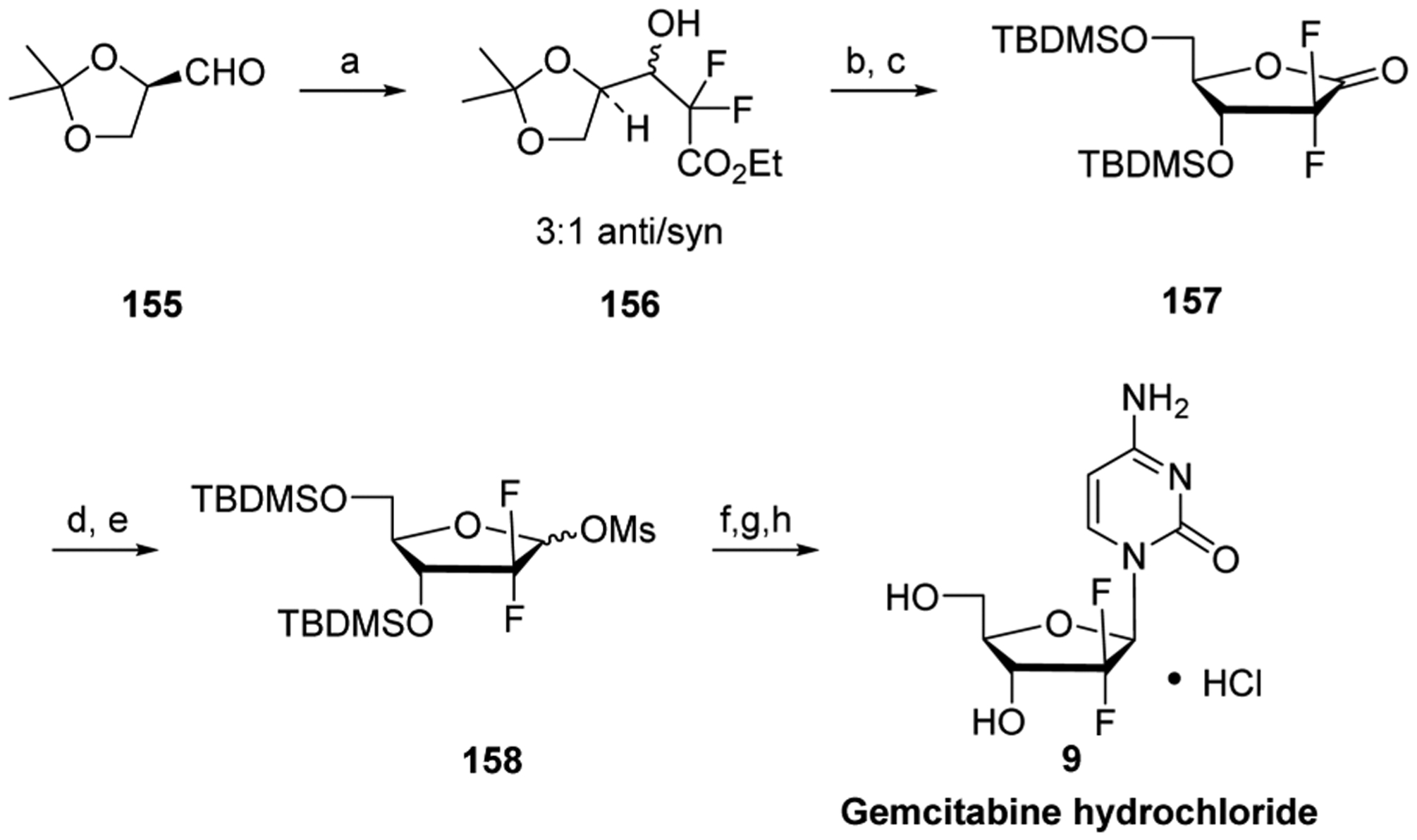

The first synthesis of capecitabine 10 was reported in the mid-1990s (Scheme 7).150,203 Compound 79 is a key intermediate and is synthesized in six steps from d-ribose through a cyclization, mesylation, iodidation, reductive dehalogenation, hydrolysis, and cyclization/acetylation sequence. 5-Fluorocytosine, prepared by treating cytosine with trifluoromethyl hypofluorite in MeOH,204 was glycosylated with protected sugar 79 in good yield. N4-Amino acylation followed by selective deprotection of the 2′,3′-acetyl groups by treatment with aqueous sodium methoxide afforded crude capecitabine 10. Finally, pure capecitabine 10 was precipitated as a white solid from ethyl acetate/hexanes on a 100 gram-scale.

Scheme 7. Synthesis of Capecitabine 10a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) HCl, MeOH/Me2CO, 78%; (b) MsCl, pyr; (c) NaI, DMF; (d) Pd/C, H2, 27%; (e) aq HCl, 100 °C, 97%; (f) Ac2O, pyr, 64%; (g) 5-fluorocytosine, HMDS, SnCl4, DCM, 76%; (h) n-pentyl chloroformate, pyr; (i) aq NaOH, MeOH.

Two large-scale process syntheses of capecitabine 10 were reported by Hoffman-La Roche205 and Gore et al.206 Both syntheses use 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine 85 as a key intermediate (Scheme 8). 5-Fluorocytidine 81, synthesized by treating protected cytidine with CF3 OF/CCl3 F,200 was protected, tosylated, and subsequently converted to 5′-iodo 83.207 Reductive dehalogenation followed by deprotection produced intermediate 85.208 This same sequence can also be employed to prepare doxifluridine 23, although using 5-fluorouridine as the starting material.

Scheme 8. Synthesis of Doxifluridine 23 and Capecitabine 10a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 2,2-dimethoxypropane, TsOH, Me2CO, rt, 2 h, 95%; (b) methyltriphenoxyphosphonium iodide, DMF, rt, 2.5 h, then MeOH, rt, 1 h, 74%; (c) Et3N, H2, Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 1.5 h, 93%; (d) TFA, 40 min, 78%; (e) CH3(CH2)4OCOCl, pyr, DCM, −5 °C to rt, overnight, 92%; (f) NaOH, MeOH, −10 °C, 15 min, then concd HCl, 87%; (g) 87, THF, reflux, 66%.

The Hoffmann-La Roche synthesis converted 85 to the trisacylated intermediate 86, using 3 equiv of n-pentyl chloroformate in cold dichloromethane and pyridine. Selective removal of 2′,3′-ester groups was accomplished by treatment with aqueous sodium hydroxide in cold methanol, and precipitation from cold ethyl acetate afforded pure capecitabine 10.

The Gore et al. approach converted 85 directly to the product 10 by selective N4 acylation. In refluxing THF, intermediate 85 was reacted with pentyloxycarbonyl-1-hydroxybenzotriazole 87, which can be easily made from pentyl chloroformate and HOBt. This was followed by aqueous workup and precipitation to afford 10. Other acylating agents, such as pentyloxycarbonyl-imidazole, pentyloxycarbonyl-4-nitrophenoxy, and pentyloxycarbonyl-pentafluorophenoxy were also used, and produced similar yields.

The Jamison group used continuous flow chemistry to prepare capecitabine 10.209 The reaction exhibited impressive yields, “green” conditions, and very short reaction times (Scheme 9). The glycosylation reaction between triacetate intermediate 88 and silylated pyrimidine 90, while under BrØnsted acid-catalyzed conditions, was completed in 20 min. This procedure does not require aqueous workup. Mixing conditions were carefully monitored to form the N4-carbamate intermediate. Deprotection with a mixture of NaOH/MeOH/H2O occurred at room temperature in only 2 min. The overall process produced milligrams of capecitabine 10 in less than 1 h and a 72% yield from starting materials 88 and 90.

Scheme 9.

Flow Synthesis of Capecitabine 10

In the same report,209 doxifluridine 23 was also synthesized using protected sugar 88, which was condensed with silylated 5-FU 2 in a glycosylation reaction. Deprotection of the resulting intermediate with sodium methoxide furnished the product. This one-flow, two-step process produced doxifluridine 23 in 89% yield in 10 min.

5.1.2.3. NUC-3373 Synthesis.

In 2011, McGuigan and co-workers reported the synthesis of NUC-3373 37.156 The agent was prepared by reaction of phosphochloridate 93 (produced using l-alanine benzyl ester salt and 1-naphthyl-dichlorophosphate 92) with floxuridine 5 in THF in the presence of t-BuMgCl (Scheme 10). The synthesis produces milligrams of the final product and requires column chromatography to produce the purified mixture of diastereomers. Furthermore, no large-scale syntheses of NUC-3373 37 have been reported.

Scheme 10. Synthesis of NUC-3373 37a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) l-alanine benzyl ester salt, Et3N, DCM, −78 °C, 1–3 h, 74%; (b) t-BuMgCl, THF, rt, 18 h, 8%.

5.1.2.4. Floxuridine, 5-Fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine, and Tetrahydrouridine Syntheses.

In the late 1950s, floxuridine 5 was originally prepared enzymatically and later converted to 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine 38 via chemical synthesis.210–212 Robin’s method (see Sections 5.1.2.1) was used to prepare both compounds in only two steps from 2′-deoxyuridine 94a and 2′-deoxycytidine 94b, with the key ring fluorination and sugar deprotection occurring in one pot (Scheme 11). This approach has the advantage of starting from a deoxynucleoside, which already has the needed stereochemistry fixed.

Scheme 11. Synthesis of Floxuridine 5, 5-Fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine 38, and Tetrahydrouridine 39a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Ac2O, DMAP, rt, 24 h, 88% (for 95a); Ac2O, pyr, rt, 4.5 h, 99% (for 95b); (b) CF3OF, CCl3F, CHCl3, −30 °C, evaporation, then Et3N, MeOH, H2O, rt, (55% for 5),(69% for 38); (c) Rh/Al, H2 (g), H2O, overnight; (d) H2O, pH 6, 92% (over two steps); (e) Rh/Al, H2 (g), NaOH, H2O, 24 h, 45% of 99, 35% of 39; (f) NaBH4, H2O, freezer, overnight.

Surprisingly few syntheses of tetrahydrouridine 39 have been reported. In 1967, Hanze reported two approaches to the compound (Scheme 11).213 Cytidine 96 was “overreduced” to tetrahydrocytidine 97 in one step using rhodium on aluminum in water, and subsequent hydrolysis afforded tetrahydrouridine 39. Uridine 98 was reduced to 5,6-dihydrouridine 99 also using rhodium and aluminum, and subsequent treatment with sodium borohydride furnished the target compound. The syntheses suffered from complex reaction mixtures, and no yields were reported.

Aoyama reported a gram-scale synthesis of floxuridine 5,214 in which the key step was the condensation of 5-fluoro-2,4-bis(trimethylsilyloxy)pyrimidine 102 with 3,5-bis(O-p-chorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-α-D-ribofuranosyl chloride 101. Chlorosugar 101 was made as the pure α anomer in three steps from 2′-deoxyribose (Scheme 12).215,216 The condensation was performed in the presence of p-nitrophenol, which led, interestingly, to the stereoselective production of the desired β-anomer 103, whereas the combination of p-nitrophenol and pyridine as catalysts led to formation of the α-anomer. Recrystallization from acetic acid gave the pure β-anomer, which was deprotected with methanolic ammonia, concluding the synthesis.

Scheme 12. Synthesis of Floxuridine 5a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) AcCl, MeOH, 25 °C, 45 min, then pyr; (b) pyr, DMAP, 4-ClBzCl, 0 °C, 1 h then 25 °C, 12 h; (c) HOAc, HCl (g), 0 °C, 7–10 min, 82% (α-anomer crystallizes from the solvent); (d) p-nitrophenol, CHCl3, 30 °C, 12 h, 92%; (e) NH3/MeOH, 30 °C, 16 h, 81%.

5.1.2.5. Tegafur, Carmofur, and Flucytosine Syntheses.

In 1976, an original synthesis of tegafur 19 was reported that coupled 2-acetoxytetrahydrofuran with silylated 5-FU 2 in the presence of sodium iodide in 95% yield.70,217 Five years later, Miyashita et al. reported an alternative preparation (Scheme 13).218 The synthesis started with a one-pot condensation of urea 69, triethyl orthformate 104, and methyl malonate 105 under solvent-free conditions. The resulting methyl ureidomethylenemalonate 106 was then cyclized in methanolic sodium methoxide to give 5-methoxycarbonyluracil 107. Condensation of 107 with 2,3-dihydrofuran followed by ring fluorination and subsequent hydrolysis concluded the synthesis of 19.

Scheme 13. Synthesis of Tegafur 19 and Carmofur 24a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 130 °C, 4 h, 69%; (b) NaOMe, MeOH, reflux, 10 min, 84%; (c) 2,3-dihydrofuran, pyr, 180 °C; (d) F2, AcOH, rt; (e) 1 N NaOH, rt, 1 h, 62% (over two steps); (f) aq HCHO, 55 °C, 6 h, 82%; (g) KBrO3, 80 °C, then H2N(CH2)5CH3, DCC, MeCN, 0 °C to rt, 6 h, 40%.

Carmofur 24 has been synthesized by treating 5-FU 2 with phosgene and hexylamine.219,220 An alternative approach also utilized 5-FU 2 as starting material but used aqueous form-aldehyde to effect N-formylation. This was followed by oxidation with potassium bromate and finally condensation with hexylamine to conclude the synthesis of 24 (Scheme 13).221

Flucytosine 31 was synthesized by reacting cytidine 110 with CF3OF/CCl3F in methanol for 5 min followed by addition of triethylamine in water (Scheme 14).200

Scheme 14. Synthesis of Flucytosine 31a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) CF3OF, CCl3F, MeOH, −78 °C to rt; (b) Et3N, MeOH, H2O, rt, 8 h, 85% (over two steps).

5.1.2.6. Gimeracil and Oteracil Syntheses.

In 1953, Kolder and Hertog reported a synthesis of the TS-1 additive gimeracil 20, which was completed in seven steps using 4-nitropyridine N-oxide as starting material.222 Later, Yano et al. reported an alternative gram-scale synthesis (Scheme 15).223 The one-pot, three component condensation of malononitrile 111, 1,1,1-trimethoxyethane, and 1,1-dimethyoxytrimethylamine generated the dicyano intermediate 112, which was into 2(1H)-pyridinone 113.224 Selective chlorination of 113 was followed by acid-mediated demethylation, hydrolysis, and decarboxylation, to afford gimeracil 20. Interestingly, Xu et al. found that treatment of intermediate 113 with sulfuryl chloride resulted in dichloro 115 formation, which could still be converted to gimeracil 20 by treatment with sulfuric acid.225

Scheme 15. Synthesis of Gimeracil 20a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) CH3C(OCH3)3, MeOH, then (CH3)2NHCH(OCH3)2, reflux, 92%; (b) aq AcOH, 130 °C, 2 h, 95%; (c) SO2Cl2, HOAc, 50 °C, 0.5 h, 91%; (d) 40% H2SO4, 130 °C, 4 h, 91%; (e) SO2Cl2, HOAc, 50 °C, 45 min, 86%; (f) 75% H2 SO4, 140 °C, 3 h, then NaOH, then pH 4–4.5, 89%.

Poje et al. reported a two-step, gram-scale preparation of the TS-1 additive oteracil 21 (Scheme 16).226 Iodine-mediated-oxidation of uric acid 116 produced dehydroallantoin 117 as the major product, and subsequent treatment with potassium hydroxide resulted in the rearranged product oteracil 21.227

Scheme 16. Synthesis of Oteracil 21a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) LiOH, I2, H2O, 5 °C, 5 min, then AcOH, 75%; (b) aq KOH, 20 min, rt, 82%.

5.1.3. Trifluorothymidine and Tipiracil Hydrochloride (TAS-102) Biology.

In 1964, Heidelberger and co-workers synthesized trifluorothymidine (TFT, 15) and demonstrated that it had promising anticancer activity.228–231 Initial animal studies showed that TFT 15 was degraded to trifluorothymidine and catabolite 5-carboxyuracil, in the liver, spleen, and intestines.230 The agent showed reductions in some tumor sizes during a clinical trial but, like other antimetabolites, exhibited a plasma half-life of 15 min in cancer patients.232 Research on TFT 15 was discontinued due to inadequate information on the pharmacokinetics and toxicity profile.233,234

TFT 15 is a substrate for thymidine kinase, generating TFT-5′-monophosphate (an active intracellular metabolite). Similar to 5-FU-5′-monophosphate II, TFT-5′-monophosphate inhibits thymidylate synthase (Figure 8).235 In contrast to 5-FU-5′-monophosphate II, TFT-5′-monophosphate does not form a ternary complex with thymidylate synthase but inhibits it by binding to the active site of the enzyme.236 Furthermore, TFT-5′-monophosphate is a reversible inhibitor of thymidylate synthase, and removal of the agent results in rapid recovery of enzyme activity, whereas inhibition caused by formation of the 5-FU-5′-monophosphate II ternary complex has prolonged effects.237 TFT-5′-monophosphate can be further phosphorylated to its triphosphate form (another active metabolite) and then incorporated into DNA to promote single-strand breaks.238 DNA-incorporated TFT-5′-monophosphate is resistant to DNA glycosylase,239 and incorporated TFT-5′-monophosphate can promote DNA instability and double-stranded breaks.240,241

The major drawback of TFT 15 monotherapy is its rapid degradation within the body, primarily by the action of thymidine phosphorylase, providing a natural TFT resistance mechanism.242 However, coadministration of TFT 15 and a thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor improved the pharmacokinetic profile in animal models and antitumor activity in cell lines and animal models.243 Currently, Taiho Pharmaceuticals is developing TAS-102 (15 + 16) as a combination therapy that uses TFT 15 with tipiracil hydrochloride 16, a thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor with an IC of 35 nM,243 in a respective molar ratio of 2:1. This combination was shown to greatly decreased the biodegradation of TFT 15 in vitro.240 Interestingly, tipiracil hydrochloride 16 has also been shown to have antiangiogenic activity.228

TAS-102 (15 + 16) was FDA-approved in Sept 2015 for treatment in patients with colorectal cancer,244 and it is also currently being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of advanced solid tumors and metastatic refractory colorectal cancer233 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01607957—active status, not recruiting). A study was initiated evaluating TAS-102 (15 + 16) plus nivolumab in patients with microsatellite stable refractory metastatic colorectal cancer ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02860546—recruiting patients). In addition, TFT 15 has been pursued as an antiviral agent (registered as Viroptic) for use against the herpes simplex virus.245,246

5.1.4. Trifluorothymidine and Tipiracil Hydrochloride (TAS-102) Syntheses.

Heidelberger et al. reported the first synthesis of TFT 15 (Scheme 17), featuring an enzyme-mediated transglycosylation of 5-trifluoromethyluracil 126 with thymidine.229 The trifluoro base 126 was prepared in an eight-step sequence. The synthesis began with treatment of trifluoroacetone 118 with hydrogen cyanide to produce cyanohydrin 119, and subsequent acetylation and ester pyrolysis afforded alkene 120. Treatment of 121 with anhydrous HBr and urea provided ureidoamide 123, which was then refluxed in acid to generate 5,6-dihydro-5-trifluoromethyluracil 124. This intermediate was subjected to a bromination–dehydrobromination sequence, furnishing 5-trifluoromethyluracil 126.

Scheme 17. Synthesis of Trifluorothymidine 15a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) NaCN, H2SO4, H2O, 10 °C, 3 h, 99%; (b) Ac2O, concd H2SO4, reflux, 1 h, 78%; (c) 500 °C, 4 h, 64%; (d) HBr (g), MeOH, 0 °C, 36 h, 82%; (e) (NH2)2CO, H2O, 100 °C, 30 min, 28%; (f) aq HCl, reflux, 1 h, 58%; (g) Br2/AcOH, reflux, 3 h, 85%; (h) DMF, 140 °C, 75 min, 80%; (i) thymidine, bactotryptone, NaCl, Escherichia coli B, 0.067 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.7), 37 °C, 3.5 h, 14%.

Komatsu et al. have reported a more modern and enzyme-free preparation of TFT 15.247 The preparation featured a green glycosylation reaction performed on the 100-g-scale using the TMS-protected analog of thymine 127 and the corresponding chlorosugar 101, made in two steps from 2′-deoxyribose. Conditions were sought to increase the rate of glycosylation (e.g., 101α to 128) and decrease the rate of chlorosugar anomerization (e.g., 101α to 101β), thereby increasing the yield of the β-glycosylation product 128 (Scheme 18).248

Scheme 18. Synthesis of Trifluorothymidine 15a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) AcCl, MeOH, 25 °C then pyr; (b) pyr, DMAP, 4-ClBzCl, 0 °C, 1 h, then 25 °C, 12 h; (c) HOAc, HCl (g), 0 °C, 7–10 min, 82% (over three steps); (d) 127, anisole, 50 °C, 3.5 h, 85% (β/α = 85.7:14.3); (e) NaOMe, MeOH, 4 °C, 3.5 h, then AcOBu, 97% (β/α = 99.92:0.08).

Nonpolar solvents were used to decrease chlorosugar anomerization, and temperature and reactant concentrations were explored empirically. Optimized large-scale conditions included condensation of silylated trifluorothymidine with an equimolar amount of chlorosugar 101 in minimal amounts of anisole (96% w/w of 101) at 50 °C, producing an 85:15 β/α anomeric mixture of 128/129 in 71% yield. Deprotection with NaOMe at 4 °C, precipitation and filtration, and finally washing with AcOBu (to remove residual methyl 4-chlorobenzoate) produced pure trifluorothymidine 15.

A concise 100-g-scale synthesis of tipiracil hydrochloride 16 has been reported (Scheme 19).249 Amination of 134 with methanolic ammonia led to the cyclized intermediate 2-iminopyrrolidine 135.250 In parallel, 6-chloromethyl uridine, which can be prepared in four steps from urea 69 and ethyl 2-acetoacetate 130 via intermediate 131,251 was chlorinated at the 5-position to furnish the dichloromethyl uracil derivative 133.252 Finally, condensation of 133 with 135 produced tipiracil hydrochloride 16.249

Scheme 19. Synthesis of Tipiracil Hydrochloride 16a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) SO2Cl2, AcOH, 50 °C, 2.5 h, 83%; (b) NH3/MeOH, 120 °C, 10 h, 83%; (c) NaOEt, DMF, rt, 16 h, then aq HCl, 38%.

5.2. Azanucleosides

5.2.1. Decitabine, Azacytidine, CP-4200, and SGI-110 Biologies.

The azanucleosides, decitabine (Dacogen, 14), and azacytidine (Videza, 11), were first developed as cytostatic agents nearly half a century ago.253,254 These cytostatic agents were later found to inhibit DNA methylation in human cell lines and were developed as epigenetic drugs.

Decitabine 14 is a 2′-deoxy-5-azanucleoside analog of cytidine that enters the cell by ENT-1.255 It is subsequently converted to decitabine-5′-monophosphate by 2′-deoxycytidine kinase. Further phosphorylation leads to the active metabolite decitabine-5′-triphosphate, which is a substrate for DNA polymerase α and is incorporated into the DNA.256 The incorporated decitabine-5′-monophosphate cannot be methylated, which can influence epigenetic gene regulation.257 DNA methylation usually involves the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-l-methionine, catalyzed by DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs), to the 5-position of a cytosine base within a cytosine-phosphate-guanosine dinucleotide.258,259 Furthermore, DNA hypermethylation often silences tumor suppressor genes in hematopoietic malignancies,260 and inhibition of DNA methylation at regions of decitabine-5′-monophosphate incorporation in the DNA most likely restores the expression of some of these genes.261–264

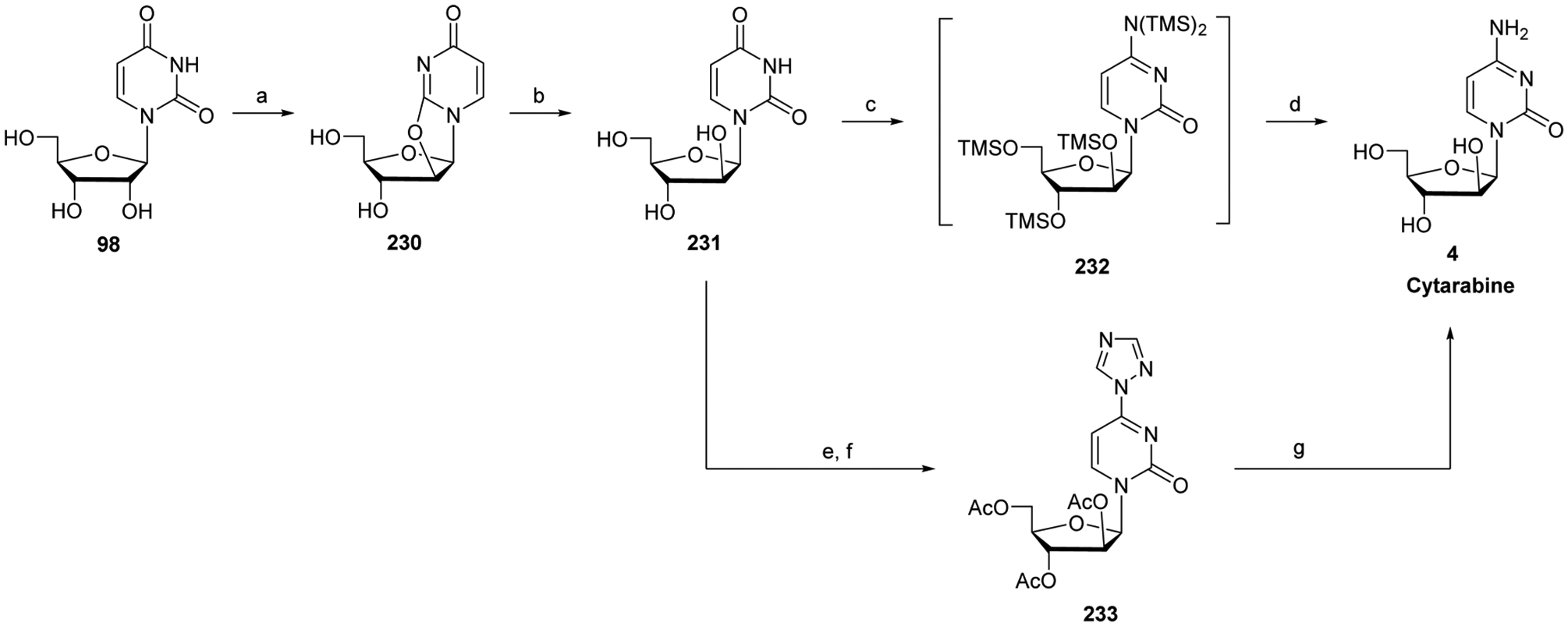

The ability of decitabine 14 to inhibit DNA methylation is often attributed to the formation of a complex between the azacytosine-guanine dinucleotide and DNMT1.265 This maypossibly occur via the covalent trapping paradigm (Figure 12).266 A covalent bond is formed between DNMT1 and the C6-position of the azacytosine base. Methylation of the nitrogen at position 5 of the base then occurs; however, β-elimination cannot occur due to the lack of a hydrogen atom at this position. As a consequence, DNMT1 remains covalently bound to the aza-base and is unable to continue its methylation activity. The covalent complex also triggers DNA damage signaling to result in DNMT1 degradation.267 A recent study, however, indicated that decitabine 14 could induce degradation of methyltransferases without the formation of the covalent complex, suggesting that the agent may work by additional mechanisms as well.268

Figure 12.

Covalent trapping paradigm: mechanism-based DNMT1 degradation by decitabine 14.

Decitabine 14 suffers from some chemical stability issues. The triazine ring of the drug is prone to hydrolytic opening and deformylation, whereas the sugar is susceptible to anomerization. Several groups have reported a half-life of decitabine 14 ranging from 3.5 to 21 h at physiological pH and temperature,269 whereas the in vivo half-life of decitabine 14 has been reported to be 15–20 min.270 Once the prodrug is metabolized to release decitabine 14 in the liver or cells, the high levels of cytidine deaminase protein will generate an inactive nucleoside byproduct,169 which in turn limits the intracellular concentration and toxicity of decitabine 14. Finally if patients have reduced levels of 2′-deoxycytidine kinase activity, this may also contribute to natural decitabine resistance, as observed with decitabine.271

At low concentrations, decitabine 14 has the ability to inhibit DNA methyltransferase 1, but it is cytotoxic at high concentrations in vitro.272,273 Optimal treatment with decitabine 14 has been tested using continuous treatment at a low concentration in patients.274 However, the agent has poor oral bioavailability (currently administered by intravenous infusion) and is also a substrate for cytidine deaminase, which provides a natural resistance mechanism. Additionally, ex vivo studies suggest that reduction in phosphorylation by 2′-deoxycytidine kinase may also contribute to decitabine resistance.271 Attempts to overcome these problems include the preparation of a decitabine mesylate salt,275 designed to increase the oral bioavailability, as well as coadministration of oral decitabine 14 with oral tetrahydrouridine 39 in patients.276

Azacytidine 11, a riboside analog of decitabine 14, is given by injection and enters cells by the uridine/cytidine transport system.277 After phosphorylation by uridine-cytidine kinase,278,279 the active metabolite azacytidine-5′-triphosphate is incorporated into RNA to disrupt RNA metabolism and protein synthesis.279 Azacytidine-5′-diphosphate can also be reduced by ribonucleotide reductase to form 2′-deoxyazacytidine-5′-diphosphate and then follows the mechanism of action of decitabine 14.

After years of clinical research and dosage refinement, conditions were finally produced to effectively treat myelodysplastic syndrome, with azacytidine 11 and decitabine 14 being FDA-approved in 2004 and 2006, respectively.280,281 Myelodysplastic syndrome, also known as preleukemia, is a group of related diseases originating in the bone marrow in which hematopoietic stem cells produce ineffective myeloid cells.282 A genetic polymorphism in the cytidine deaminase gene (79A>C) and promoter depletion (–31delC) can lead to a rapid-deaminator phenotype and an increase in mRNA expression, leading to increased toxicity in patients treated with azacytidine 11.283,284 Sorting patients based on cytidine deaminase genotypes remains difficult due to genotype to phenotype relationships, whereas developing a functional cytidine deaminase assay would be beneficial.285

Azacytidine 11 and decitabine 14 treatments are being evaluated in numerous clinical studies. An oral formulation of azacytidine (CC-486, Celgene) is currently in Phase I clinical trials (alone and in combination) for treatment of refractory solid tumors and Japanese myelodysplastic syndrome (ClinicalTrials. gov identifiers: NCT01478685—completed—no results posted, and NCT01908387—terminated status—no results posted). A Phase I/II Study of azacitidine 11 and with capecitabine 10 and oxaliplatin (DNA alkylating agent) is underway (ClinicalTrials. gov identifier: NCT01193517–active status–not recruiting). A Phase II study is examining the kinase inhibitor sorafenib with azacitidine 11 for primary response and secondary toxicity profile (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02196857–actively recruiting patients). For decitabine 14 and tetrahydrouridine 39 clinical trials, one is currently recruiting patients— adjuvant oral decitabine 14 and tetrahydrouridine 39 with or without celecoxib in people undergoing pulmonary metastasectomy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02839694–recruiting patients). Four additional studies have yet to start recruiting patients with refractory/relapsed lymphoid malignancies, pancreatic cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer using different combination treatments (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02846935–not yet recruiting patients, NCT02847000–not yet recruiting patients, NCT02795923–not yet recruiting patients, and NCT02664181–not yet recruiting patients).

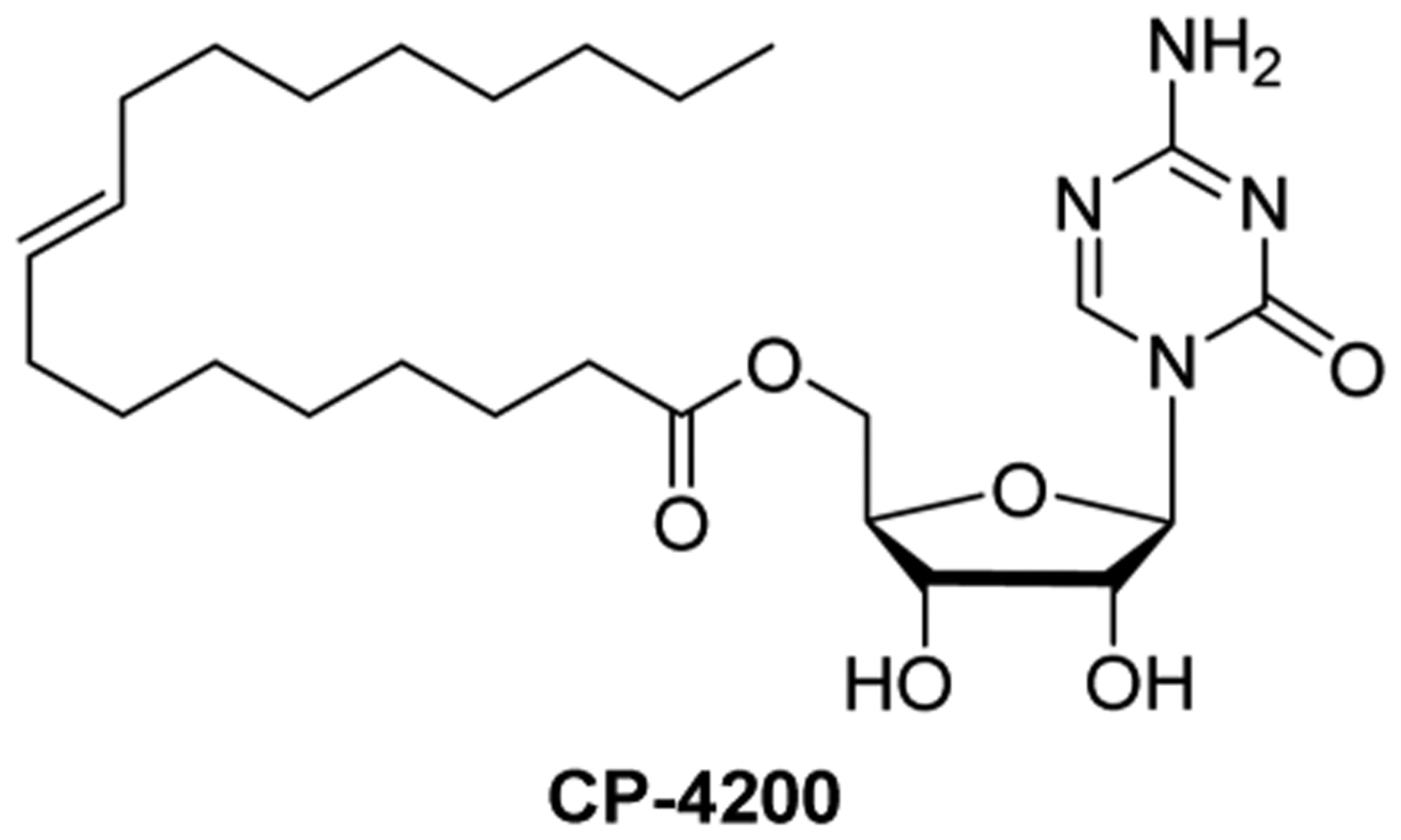

Clavis Pharma is developing CP-4200, an elaidic acid derivative of azacytidine, which has strong epigenetic modulatory potency in human cancer cell lines (Figure 13).286 The aim of this drug is to circumvent therapy resistance in patients with MDS/AML due to decrease in drug uptake by hENT1, because the agent enters the cell by a hENT1-independent mechanism.287 CP-4200 has not yet moved past pre-clinical development. CP-4200 might have an acceptable bioavailability profile for oral application.

Figure 13.

Chemical structure of CP-4200.