Abstract

Background:

Previously acknowledged as “bedside ultrasound”, point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) is gaining great recognition nowadays and more physicians are using it to effectively diagnose and adequately manage patients. To measure previous, present and potential adoption of PoCUS and barriers to its use in Canada, Woo et al established the questionnaire “Evaluation Tool for Ultrasound skills Development and Education” (ETUDE) in 2007. This questionnaire sorted respondents into innovators, early adopters, majority, and nonadopters.

Objectives:

In this article, we attempt to evaluate the prevalence of PoCUS and the barriers to its adoption in Lebanese EDs, using the ETUDE.

Materials and Methods:

The same questionnaire was again utilized in Lebanon to assess the extent of PoCUS adoption. Our target population is emergency physicians (EPs). To achieve a high response rate, hospitals all over Lebanon were contacted to obtain contact details of their EPs. Questionnaires with daily reminders were sent on daily basis.

Results:

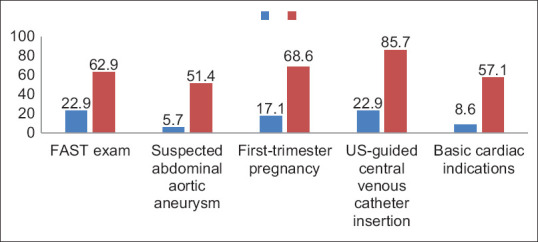

The response rate was higher in our population (78.8%) compared to Woo et al's (36.4%), as the questionnaire was sent by email to each physician with subsequent daily reminders to fill it. In fact, out of the total number of the surveyed (85 physicians), respondents were 67, of which 76.1% were males and of a median age of 43. Using ETUDE, results came as nonadopters (47.8%), majority (28.3%), early adopters (16.4%), and innovators (7.5%). Respondents advocated using PoCUS currently and in the future in five main circumstances: focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) (current 22.9%/future 62.9%), first-trimester pregnancy (current 17.1%/future 68.6%), suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm (current 5.7%/future 51.4%), basic cardiac indications (current 8.6%/future 57.1%), and central venous catheterization (current 22.9%/future 85.7%).

Conclusion:

This study is the first to tackle the extent of use and the hurdles to PoCUS adoption in Lebanese emergency medicine practice, using ETUDE. The findings from this study can be used in Lebanon to strengthen PoCUS use in the future.

Keywords: Adoption, barriers, emergency departments, Lebanon, point-of-care ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Lebanon is a low-income Middle Eastern developing country with an estimated population of 6.86 million in 2019.[1,2] Major advances were recorded in the field of emergency medicine (EM) in Lebanon over the last 10 years. The Lebanese Society of EM (LSEM) aiming at the delivery of excellent medical services within the setting of the emergency department (ED) was first founded in 2003. Then after a couple of years, and by the help of the LSEM, EM became recognized by the National Social Security Fund. Today, EM is one of the most highly regarded and competitive specialties.[3] Ultrasound training has also become part of the EM residency programs and bedside ultrasonography is usually readily available in Lebanese EDs; however, the extent of utility and expertise in the field of ultrasonography within the ED has not been studied yet.

Point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) is the bedside ultrasound utilized by physicians to effectively diagnose a patient.[4,5,6] It is noteworthy that this advance is not very recent but also does not go long back. PoCUS was first introduced in Japan and Europe in the 1980s, and then it spread to the United States,[7,8,9] where emergency physicians (EPs) took the lead. The utility of PoCUS in the ED has shown great progression since 1994 when the first EM ultrasound syllabus was issued.[10] In the setting of the ED, where diagnosis and consequent management should be immediate and accurate, ultrasound is undeniably one of the most influential tools.[11] PoCUS is currently being integrated into medical schools' curricula. Some instructors even believe that PoCUS will become the “stethoscope” of physicians.[12,13,14] The American College of EPs categorizes the role of emergency PoCUS into five clinical purposes, namely, resuscitative, diagnostic, sign or symptom based, procedure guidance, and therapeutic and monitoring.[15] Per se, PoCUS, coupled with history and physical examination, is sufficient to rule out/in most pathologies in most cases. It even contributes to the management plan by guiding certain procedures.[16,17] This is particularly important nowadays as PoCUS serves a major role in cost reduction on people and on the health-care system.[15]

The spread of innovations in populations is delineated using a model established by Rogers in 1962. Roger's Diffusion of Innovations theory categorizes implementation of innovations based on a normal distribution, divided into groups of innovators, early adopters, majority, and nonadopters.[18] An Evaluation Tool for Ultrasound skills Development and Education (ETUDE) was developed by Woo et al. in Canada to evaluate the spread of PoCUS. The five primary indications considered by this tool are confirmation of intrauterine pregnancy by a first-trimester ultrasound, evaluation of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST), ultrasound-guided central venous catheter (CVCs) insertion, and diagnosis of cardiac conditions as pericardial effusion or asystole.

Trauma is one of the most common presentations encountered in the ED, accounting for about 30% of ED visits in the United States in 2014 according to the National Center for Health.[19] Diagnostic peritoneal aspiration and lavage has always been the diagnostic tool of choice in trauma patients in the ED. Nowadays, however, it is being largely substituted by FAST due to its noninvasiveness, cost-effectiveness, and accuracy.[20,21,22,23,24]

In addition, EPs should be aware of the diagnostic challenge imposed by female patients of reproductive age presenting with an acute abdomen. In the ED, our main target is to diagnose pregnancy and confirm that it is intrauterine.[25]

Like other indications of PoCUS, cardiac ultrasound is largely used in patients presenting to the ED with dyspnea, chest pain, chest trauma, cardiac arrest, etc.[26] Cardiac ultrasound can be used to assess for cardiac activity and thus direct resuscitation in arrested patients. In addition, it can be used to diagnose pericardial effusion and identify sonographic signs of cardiac tamponade. Besides, signs of right ventricular strain in the right clinical setting may help diagnose pulmonary embolism.[26] Therefore, PoCUS has proven to be of use in cardiac patients.[27,28,29,30,31]

An AAA is a critical condition that should not be missed or misdiagnosed, as mortality rate due to ruptured AAA reaches up to 95%.[32] A ruptured AAA must be considered in old males with a history of smoking, presenting with abdominal, flank, or back pain, or in patients with hypotension not explained otherwise.[33]

In addition to all the above indications, PoCUS is used to guide various ED procedures such as CVC insertion.[34,35] In fact, it is considered the standard of care for CVC insertion nowadays.[36] This enhances the success rate of difficult procedures, leading to better patient outcomes in terms of increased satisfaction and decreased complications.[37,38]

According to Woo et al., nonadopters are physicians who did not use PoCUS and are uncomfortable using it even with the five primary conditions discussed above. The majority were only fairly comfortable with the primary indications. Early adopters are those who had basic training and were zealous to receive further guidance. Innovators are those with more advanced training that felt utmost ease using the ultrasound for the primary and the additional indications.[39]

To accurately evaluate the magnitude of the current and the potential use of PoCUS, a scoring system was utilized.[39] Questions revolved around individuals' confidence using this contraption, and points were granted based on the answers in general, as well as on each of the five principal indications (yielding a maximum of 18 points to those that are very familiar with using PoCUS). Based on the scores, the respondents were divided into nonadopters (0–24 points), majority (25–49 points), early adopters (50–74 points), or innovators (75–100 points).[39]

Objectives

Ultrasound adoption in Lebanon has not been studied yet. In this article, we attempt to evaluate the prevalence of PoCUS and the barriers to its adoption in Lebanese EDs, using the ETUDE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study development and setting

This is a survey that aims at studying the current and potential use of PoCUS in Lebanese EDs using the ETUDE. The ETUDE takes into account demographics, training level, and the use of PoCUS by EP. The five primary indications considered by this tool are confirmation of intrauterine pregnancy by a first-trimester ultrasound, evaluation of an AAA, FAST, ultrasound-guided CVCs insertion, and diagnosis of cardiac conditions as pericardial effusion or asystole. Further minor indications are listed in the study by Woo et al.[39] The basis upon which these five indications were considered “primary” is not elaborated by Woo et al.; however, there is no doubt that these five are the most commonly encountered circumstances in the setting of ED where EPs find themselves obligated to use PoCUS. Barriers to the adoption of PoCUS in Lebanese EDs were also explored. Our target population is EPs. To achieve a high response rate, hospitals all over Lebanon were contacted to obtain contact details of their EPs. After that, research assistants were assigned to send the questionnaire via E-mail to all these EPs and were required to send daily E-mails as reminders to fill the questionnaire. A total of 67 respondents composed the population of our study.

All data were entered into a Microsoft Excel database using a single data abstractor. The responses were anonymous. Analysis of data obtained was established through descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

The 67 respondents (78.8%) of the total 85 individuals enrolled comprised 76.1% of male and they had a median age of 43. Around 60% of the respondents reported unavailability of PoCUS and a limited experience with PoCUS. Adoption scores using ETUDE revealed nonadopters (47.8%), majority (28.3%), early adopters (16.4%), and innovators (7.5%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all participants (n=67)

| Variable | Participants |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (76.1) |

| Female | 16 (23.9) |

| Age, median | 43 |

| Availability of PoCUS | |

| Available | 27 (40.3) |

| Not available | 40 (59.7) |

| Level of PoCUS training | |

| None | 34 (50.7) |

| Introduction | 26 (38.8) |

| Credentialed | 5 (7.5) |

| Advanced | 2 (3) |

| Location of practice | |

| Inner city/urban/suburban | 39 (58.2) |

| Small town | 17 (25.4) |

| Rural | 10 (14.9) |

| Geographically isolated/remote | 1 (1.5) |

| ETUDE category | |

| Nonadopters | 32 (47.8) |

| Majority | 19 (28.3) |

| Early adopters | 11 (16.4) |

| Innovators | 5 (7.5) |

PoCUS: Point-of-care ultrasound, ETUDE: Evaluation Tool for Ultrasound skills Development and Education

Respondents advocated using PoCUS currently and in future in five main circumstances, namely FAST (current 22.9%/future 62.9%), first-trimester pregnancy (current 17.1%/future 68.6%), suspected AAA (current 5.7%/future 51.4%), basic cardiac indications (current 8.6%/future 57.1%), and central venous catheterization (current 22.9%/future 85.7%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Current and future use of primary indications of point-of-care ultrasound

The respondents admitted that working in a busy environment where the load is huge is one of the hindrances to the wide adoption of PoCUS (67.2%). Lack of formal requirements for PoCUS training was also an obstacle for ED physicians (46.3%). In addition to that, the lack of professional supervision and revision of findings (40.3%), difficulty saving scans (35.8%), and the time needed to complete a scan (26.8%) were all barriers to the further adoption of PoCUS in Lebanon [Table 2].

Table 2.

Barriers to the adoption of point-of-care ultrasound in Lebanon

| Barriers | Participants (n=67), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Working in a busy, high-volume department | 45 (67.2) |

| Lack of formal requirements for PoCUS training | 31 (46.3) |

| Lack of supervision and revision of findings | 27 (40.3) |

| Difficulty of saving the scans | 24 (35.8) |

| Time it takes to complete the scan | 18 (26.8) |

PoCUS: Point-of-care ultrasound

DISCUSSION

This study presses the need for more extensive training in PoCUS in the Lebanese EM department. There is an emerging keen interest in a wider adoption of PoCUS, especially in light of establishing formal emergency residency programs.

As of 2016 (the time of initiating this study), 50.7% of the survey participants had no formal training and admitted very little use of the PoCUS. However, the respondents projected future use to be over 60%. With the advancement of PoCUS and with it becoming a core competency requirement for EPs, it is only reasonable that its usage will increase.

The ETUDE of Woo et al. allowed the classification of PoCUS adoption according to Rogers' diffusion of innovation.[18,39] Rogers' theory is also valuable in appraising the difficulties to adopting bedside US by emergency providers. Working in a busy, high-volume department was one of the barriers to adoption. Lack of formal requirements for PoCUS training in Lebanon was also a major barrier for adoption. Lack of supervision and revision of findings, the difficulty of saving the scans, and the time it takes to complete the scan were all barriers to adoption. The advantage of using the bedside US (improving patient care and improving the safety of CVCs insertion) only motivates a broader adoption of PoCUS. Performing PoCUS may lead to more time at the bedside; however, it shortens the time to diagnosis and thus the length of stay in the ED, consequently leading to improvement in patient care.[40,41,42,43]

Addressing some of the barriers identified in this study will help improve PoCUS adoption in Lebanon in future.

The findings from this study can be used in Lebanon to guide interventions enhancing the use of PoCUS in future. Further studies to determine changes in adoption are warranted.

Limitations

This is a study based on a survey. Despite the high response rate (78.8%), this might still reflect response bias limiting the interpretation of the results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayram JD. Emergency medicine in Lebanon: Overview and prospect. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Review, W.P. Lebanon Population 2019. 2019. [[Last accessed on 2019 Oct 09]]. Available from: http://worldpopulationreviewcom/countries/lebanon-population/

- 3.Beirut, A.U.O. History of Emergency Medicine in Lebanon. 2019. [[Last accessed on 2019 Oct 09]]. Available from: http://wwwaubmcorglb/clinical/DEM/Pages/main/Historyaspx .

- 4.Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:749–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.J Henneberry R, Hanson A, Healey A, Hebert G, Ip U, Mensour M, et al. Use of point of care sonography by emergency physicians. CJEM. 2012;14:106–12. doi: 10.2310/8000.CAEPPS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Emergency Physicians Emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:550–70. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitson MR, Mayo PH. Ultrasonography in the emergency department. Crit Care. 2016;20:227. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1399-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Latteri S, Malaguarnera G, Mannino M, Pesce A, Currò G, Tamburrini S, et al. Ultrasound as point of care in management of polytrauma and its complication. J Ultrasound. 2017;20:171–7. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kameda T, Taniguchi N. Overview of point-of-care abdominal ultrasound in emergency and critical care. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:53. doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mateer J, Plummer D, Heller M, Olson D, Jehle D, Overton D, et al. Model curriculum for physician training in emergency ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders JL, Noble VE, Raja AS, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA., Jr Access to and use of point-of-care ultrasound in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:747–52. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.7.27216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppmann R, Blaivas M, Elbarbary M. Better medical education and health care through point-of-care ultrasound. Acad Med. 2012;87:134. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823f0e8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoppmann RA, Rao VV, Bell F, Poston MB, Howe DB, Riffle S, et al. The evolution of an integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 9-year experience. Crit Ultrasound J. 2015;7:18. doi: 10.1186/s13089-015-0035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoppmann RA, Rao VV, Poston MB, Howe DB, Hunt PS, Fowler SD, et al. An integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 4-year experience. Crit Ultrasound J. 2011;3:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s13089-011-0052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ultrasound guidelines: Emergency point-of-care and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:e27–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendall JL, Hoffenberg SR, Smith RS. History of emergency and critical care ultrasound: The evolution of a new imaging paradigm. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:S126–30. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260623.38982.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faruqi I, Siddiqi M, Buhumaid R. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Emergency Department. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner R. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edition, Everett M. Rogers. Free Press, New York, NY (2003), 551 pages. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:776. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC National Center for Health Statistics Emergency Department Visits Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. [[Last accessed on 2019 Oct 03]]. Available from: https://wwwcdcgov/ nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2014_ed_web_tablespdf .

- 20.Melniker LA, Leibner E, McKenney MG, Lopez P, Briggs WM, Mancuso CA. Randomized controlled clinical trial of point-of-care, limited ultrasonography for trauma in the emergency department: thefirst sonography outcomes assessment program trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarter FD, Luchette FA, Molloy M, Hurst JM, Davis K, Jr, Johannigman JA. Institutional and individual learning curves for focused abdominal ultrasound for trauma: cumulative sum analysis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:689–700. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boulanger BR, McLellan BA, Brenneman FD, Ochoa J, Kirkpatrick AW. Prospective evidence of the superiority of a sonography-based algorithm in the assessment of blunt abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1999;47:632–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199910000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amer MS, Ashraf M. Role of FAST and DPL in assessment of blunt abdominal trauma. Prof Med J. 2008;15:200–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adedipe A, Backlund BH, Basler E, Shah S. Accuracy of the fast exam: A retrospective analysis of blunt abdominal trauma patients? Emerg Med. 2015;6:308. doi:10.4172/2165-7548.1000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu F, Winters ME. Emergency Medicine, An Issue of Physician Assistant Clinics, E-Book. Vol. 2. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arntfield RT, Millington SJ. Point of care cardiac ultrasound applications in the emergency department and intensive care unit-a review. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012;8:98–108. doi: 10.2174/157340312801784952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones AE, Tayal VS, Sullivan DM, Kline JA. Randomized, controlled trial of immediate versus delayed goal-directed ultrasound to identify the cause of nontraumatic hypotension in emergency department patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1703–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133017.34137.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dresden S, Mitchell P, Rahimi L, Leo M, Rubin-Smith J, Bibi S, et al. Right ventricular dilatation on bedside echocardiography performed by emergency physicians aids in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaspari R, Weekes A, Adhikari S, Noble VE, Nomura JT, Theodoro D, et al. Emergency department point-of-care ultrasound in out-of-hospital and in-ED cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;109:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farsi D, Hajsadeghi S, Hajighanbari MJ, Mofidi M, Hafezimoghadam P, Rezai M, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS) by emergency medicine residents in patients with suspected cardiovascular diseases. J Ultrasound. 2017;20:133–8. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0246-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell FM, Rutz M, Pang PS. Focused ultrasound in the emergency department for patients with acute heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2015;1:83–6. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2015.1.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Miniño AM, Kung HC. Deaths: Final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham AC, Martinez JP. Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34:xvii–xviii. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hind D, Calvert N, McWilliams R, Davidson A, Paisley S, Beverley C, et al. Ultrasonic locating devices for central venous cannulation: Meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327:361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karakitsos D, Labropoulos N, De Groot E, Patrianakos AP, Kouraklis G, Poularas J, et al. Real-time ultrasound-guided catheterisation of the internal jugular vein. 2006:R162. doi: 10.1186/cc5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access. Rupp SM, Apfelbaum JL, Blitt C, Caplan RA, Connis RT, et al. Practice guidelines for central venous access: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:539–73. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c9569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatch N, Wu TS, Barr L, Roque PJ. Advanced ultrasound procedures. Crit Care Clin. 2014;30:305–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2013.10.005. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barr L, Hatch N, Roque PJ, Wu TS. Basic ultrasound-guided procedures. Crit Care Clin. 2014;30:275–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2013.10.004. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woo MY, Frank JR, Lee AC. Point-of-care ultrasonography adoption in Canada: Using diffusion theory and the evaluation tool for ultrasound skills development and education (ETUDE) Canadian J Emerg Med. 2014;16:345–51. doi: 10.2310/8000.2013.131243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devia Jaramillo G, Torres Castillo J, Lozano F, Ramírez A. Ultrasound-guided central venous catheter placement in the emergency department: Experience in a hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. Open Access Emerg Med. 2018;10:61–5. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S150966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pare JR, Pollock SE, Liu JH, Leo MM, Nelson KP. Central venous catheter placement after ultrasound guided peripheral IV placement for difficult vascular access patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dent B, Kendall RJ, Boyle AA, Atkinson PR. Emergency ultrasound of the abdominal aorta by UK emergency physicians: A prospective cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:547–9. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.048405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blaivas M, Sierzenski P, Plecque D, Lambert M. Do emergency physicians save time when locating a live intrauterine pregnancy with bedside ultrasonography? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:988–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]