Abstract

Background:

Recent data suggest that acidosis alone is not a good predictor of mortality in trauma patients. Little data are currently available regarding factors associated with survival in trauma patients presenting with acidosis.

Aims:

The aims were to characterize the outcomes of trauma patients presenting with acidosis and to identify modifiable risk factors associated with mortality in these patients.

Settings and Design:

This is a retrospective observational study of University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) trauma patients between November 23, 2013, and May 21, 2017.

Methods:

Data were collected from the UAMS trauma registry. The primary outcome was hospital mortality. Analyses were performed using t-test and Pearson's Chi-squared test. Simple and multiple logistic regressions were performed to determine crude and adjusted odds ratios.

Results:

There were 532 patients identified and 64.7% were acidotic (pH < 7.35) on presentation: 75.9% pH 7.2–7.35; 18.5% pH 7.0–7.2; and 5.6% pH ≤ 7.0. The total hospital mortality was 23.7%. Nonsurvivors were older and more acidotic, with a base deficit >−8, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) ≤ 8, systolic blood pressure ≤ 90, International Normalized Ratio (INR) >1.6, and Injury Severity Score (ISS) >15. Mortality was significantly higher with a pH ≤ 7.2 but mortality with a pH 7.2–7.35 was comparable to pH > 7.35. In the adjusted model, pH ≤ 7.0, pH 7.0–7.2, INR > 1.6, GCS ≤ 8, and ISS > 15 were associated with increased mortality. For patients with a pH ≤ 7.2, only INR was associated with increase in mortality.

Conclusions:

A pH ≤ 7.2 is associated with increased mortality. For patients in this range, only the presence of coagulopathy is associated with increased mortality. A pH > 7.2 may be an appropriate treatment goal for acidosis. Further work is needed to identify and target potentially modifiable factors in patients with acidosis such as coagulopathy.

Keywords: Acidosis, arterial blood gas, base deficit, pH, trauma

INTRODUCTION

The presence of acidosis in trauma patients on presentation to the emergency department has been viewed as a poor prognostic factor dating back three decades to the early descriptions of the “lethal triad” of acidosis, coagulopathy, and hypothermia.[1,2] However, recent data suggest that acidosis (pH ≤ 7.2) alone is not very good at predicting mortality in trauma patients.[3] It has been observed that trauma patients presenting with severe acidosis (pH ≤ 7.0) may still survive.[4,5]

In 1995, it was first reported that as many as 30% of trauma patients presenting with a pH ≤7.0 survived, a finding that has been confirmed in a recent study.[4,5] Survivors with severe acidosis tended to be less severely injured and have less neurologic dysfunction. However, the small number of patients presenting with this degree of acidosis made it difficult to draw conclusions regarding factors associated with survival in patients with severe acidosis.[4,5] In another recent study, a revised “lethal triad” criteria, which included fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products, base excess, and core body temperature, were found to be better at predicting mortality than the classic “lethal triad” criteria.[3] Few data are currently available regarding factors associated with survival and nonsurvival in trauma patients presenting with acidosis.

In the current study, our objectives were twofold: first, to characterize trauma patients presenting by the severity of acidosis and second, to identify potentially modifiable risk factors associated with mortality in trauma patients with acidosis.

METHODS

Study setting

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) is a tertiary care university teaching hospital with a total of 405 adult patient beds. UAMS is an American College of Surgeons Verified Level 1 Trauma Center.

Study design

The study was a retrospective observational cohort study. Data on trauma patients presenting to UAMS between November 23, 2013, and May 21, 2017, were extracted from the UAMS Trauma Registry. Patients were included if all of the following data were available at the time of presentation: arterial blood gas (ABG) pH, International Normalized Ratio (INR), base deficit (BD), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), penetrating or blunt mechanism of injury, and systolic blood pressure (SBP). Baseline demographics were collected.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with the 25th and 75th percentiles. Analyses were performed using t-test or Pearson's Chi-squared test. Simple and multiple logistic regressions were performed to determine crude and adjusted odds ratios. The logistic model was adjusted for age, race, sex, mechanism, pH, BD, SBP, INR, GCS, and ISS. The variables used in the model were those identified as significantly associated with mortality in the univariate analysis, as well as basic demographic data such as age, sex, race, and mechanism of injury. The variables in the model are consistent with what have been used in other studies of acidosis.[4,5] Data analyses were performed using JMP Pro 13 (JMP Statistical Discovery from SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Population and demographics

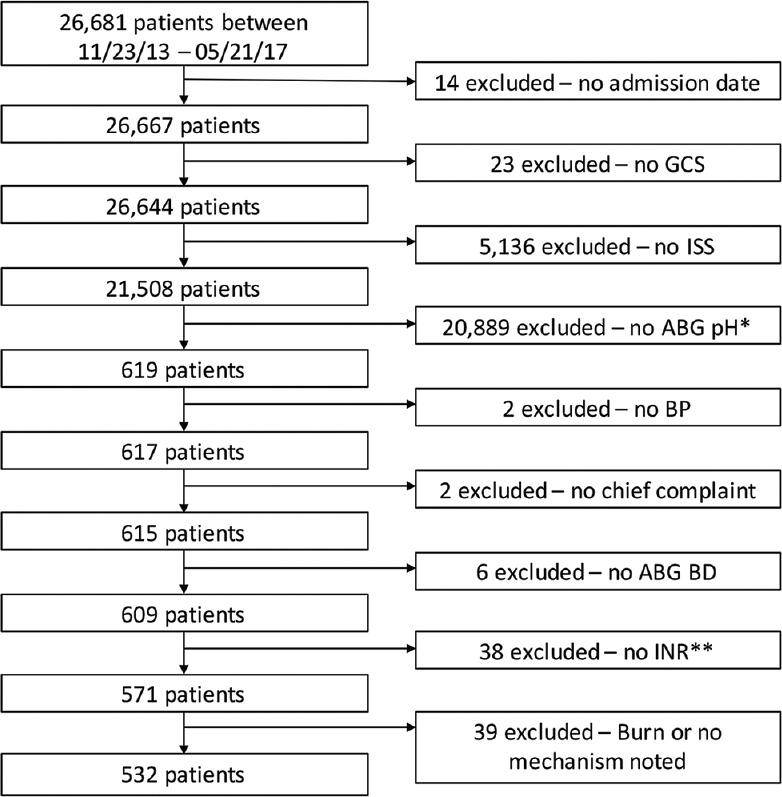

A total of 532 patients were included in the study [Figure 1]. The characteristics of the study population are displayed in Table 1. Approximately two-third of the patients had some degree of acidosis (pH < 7.35), of these patients, 75.9% had a pH between 7.2 and 7.35, 18.6% had pH between 7.0 and 7.2, and 5.5% had a pH ≤ 7.0. The mean base deficit was −4.6 with almost 25% of patients having a base deficit ≥−8.0. Most patients suffered a blunt mechanism of injury.

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion flow diagram. *1 excluded because of pH reporting error. **2 Excluded because of International Normalized Ratio reporting error

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Summary measure (n=532) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (SD) | 42.6 (18.8) |

| Sex (percentage male) | 76.3 |

| Race (%) | |

| White | 68.0 |

| Black or African-American | 27.1 |

| Other race | 4.9 |

| Mortality (percentage dead) | 23.7 |

| ED mortality (% dead) | 1.3 |

| Mechanism of injury (%) | |

| Penetrating | 19.9 |

| Blunt | 80.1 |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) [SD] | 122.3 (33.2) |

| SBP ≤90 (mmHg) | 14.7 |

| Median total hospital days (25th, 75th) | 8 (3, 16) |

| Median total ICU days (25th, 75th) | 4 (2, 10) |

| Median total ventilatory days (25th, 75th) | 3 (1, 7) |

| ISS >15 | 66.7 |

| GCS ≤8 | 66.0 |

| Mean INR (SD) | 1.5 (3.0) |

| INR >1.6 | 10.0 |

| Mean ABG pH (SD) | 7.30 (0.13) |

| ABG pH | |

| ≤7 | 3.6 |

| 7.0-7.2 | 12.0 |

| 7.2-7.35 | 49.1 |

| >7.35 | 35.3 |

| Mean ABG BD (SD) | −4.6 (6.7) |

| ABG BD | |

| ≤−8 | 24.2 |

| >−8 | 75.8 |

SD: Standard deviation, ED: Emergency department, ISS: Injury Severity Score, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, INR: International Normalized Ratio, ABG pH: Arterial blood gas pH, ABG BD: Arterial blood gas base deficit, ICU: Intensive care unit

Mortality

The mortality among the study population was 23.7%, of which 5.6% occurred in the emergency room. The characteristics of survivors versus nonsurvivors are displayed in Table 2. Nonsurvivors were older and more acidotic and were also more likely to have more severe metabolic acidosis (base deficit ≥−8), worse neurologic status (GCS ≤ 8), hypotension (SBP ≤ 90), coagulopathy (INR > 1.6), and more severe injury (ISS > 15).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients by mortality

| Characteristic | Alive (n=406) | Dead (n=126) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.7 | 48.5 | <0.001† |

| Sex (percentage male) | 77.1 | 73.8 | 0.449* |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 67.2 | 70.6 | 0.389* |

| Black or African-American | 28.3 | 23.0 | |

| Other race | 4.4 | 6.4 | |

| Mechanism of injury (%) | |||

| Penetrating | 19.7 | 20.6 | 0.819* |

| Blunt | 80.3 | 79.4 | |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) (%) | 125.1 | 113.3 | 0.004† |

| SBP ≤90 (mmHg) (%) | 11.3 | 25.4 | <0.001* |

| Mean total hospital days | 13.5 | 4.9 | <0.001† |

| Mean total ICU days | 7.4 | 4.8 | <0.001† |

| Mean total ventilatory days | 5.4 | 4.5 | 0.143† |

| ISS >15 (%) | 60.1 | 88.1 | <0.001* |

| GCS ≤8 (%) | 62.1 | 78.6 | <0.001* |

| Mean INR (%) | 1.3 | 2.5 | <0.001† |

| INR >1.6 (%) | 3.9 | 29.4 | <0.001* |

| Mean ABG pH | 7.31 | 7.24 | <0.001† |

| ABG pH (%) | |||

| ≤7.0 | 1.0 | 11.9 | <0.001* |

| 7.0-7.2 | 8.9 | 22.2 | |

| 7.2-7.35 | 51.7 | 40.5 | |

| >7.35 | 38.4 | 25.4 | |

| Mean ABG BD | −4.0 | −6.5 | 0.003† |

| ABG BD (%) | |||

| ≤−8 | 20.2 | 37.3 | <0.001* |

| >−8 | 79.8 | 62.7 |

†t-test, *Pearson’s Chi-squared test. ED: Emergency department, ISS: Injury Severity Score, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, INR: International Normalized Ratio, ABG pH: Arterial blood gas pH, BD: Base deficit, ICU: Intensive care unit

Acidosis and mortality

We observed that patients with pH ≤ 7.2 had a statistically significant increase in mortality as compared to patients with a pH > 7.2 (51.8% vs. 18.5%, P < 0.001). This was particularly so for patients with a pH ≤ 7.0 who had a mortality of 79.0%. On the other hand, survival for patients with a pH between 7.2 and 7.35 was comparable to those patient with a pH > 7.35 (19.5% vs. 17.1%, P = 0.621).

Patients with a base deficit ≥−8 were associated with a statistically significantly higher mortality as compared to patients with a base deficit <−8 (36.4% vs. 19.6%, P < 0.001). On the other hand, patients with more severe metabolic acidosis (base deficit ≥−8) were less likely to die if their pH was > 7.2 than if the pH was ≤ 7.2 (18.0% vs. 52.9%, P < 0.001).

Multivariate analysis

In the logistic model of mortality, acidosis (pH ≤ 7.2) was associated with an almost 4-fold increase in the odds of mortality, while severe acidosis (pH ≤ 7.0) was associated with an almost 25-fold increase in the odds of mortality [Table 3]. On the other hand, for those patients presenting with a between pH 7.2 and 7.35, the odds of mortality were no greater than for patients presenting with a normal pH (>7.35). Other variables associated with mortality were neurologic status (GCS ≤ 8), coagulopathy (INR > 1.6), and injury severity (ISS > 15). Neither base deficit nor SBP was significantly associated with mortality in the adjusted model.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for mortality by arterial blood gas pH, arterial blood gas base deficit, International Normalized Ratio, Glasgow Coma Scale, systolic blood pressure (mmHg), and Injury Severity Score

| Variable | Crude | Adjusted* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| ABG pH | ||||||

| ≤7.0 | 18.28 | 5.69-58.71 | <0.001† | 25.60 | 5.28-124.17 | <0.001† |

| 7.0-7.2 | 3.79 | 2.03-7.07 | 3.84 | 1.56-9.44 | ||

| 7.2-7.35 | 1.18 | 0.72-1.93 | 1.26 | 0.71-2.22 | ||

| >7.35 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| ABG BD | ||||||

| ≤−8 | 2.35 | 1.52-3.63 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.33-1.36 | 0.274 |

| >−8 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| INR | ||||||

| >1.6 | 10.13 | 5.40-19.03 | <0.001 | 6.15 | 3.00-12.62 | <0.001 |

| ≤1.6 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| GCS | ||||||

| ≤8 | 2.24 | 1.40-3.59 | <0.001 | 2.23 | 1.24-4.01 | 0.007 |

| >8 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| SBP | ||||||

| ≤90 | 2.66 | 1.61-4.41 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 0.75-2.73 | 0.278 |

| >90 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| ISS | ||||||

| >15 | 4.91 | 2.77-8.73 | <0.001 | 3.60 | 1.92-6.75 | <0.001 |

| ≤15 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

*Each variable adjusted by other five variables and age, race, sex, mechanism of injury, †P-trend. ABG: Arterial blood gas, CI: Confidence interval, OR: Odds ratio, BD: Base deficit, INR: International Normalized Ratio, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, SBP: Systolic blood pressure, ISS: Injury Severity Score

In the logistic model of mortality including only patients with a pH ≤ 7.2, only coagulopathy (INR > 1.6) was associated with increased odds of mortality [Table 4]. For those patients with a pH 7.2–7.35, neurologic status (GCS ≤ 8), coagulopathy (INR > 1.6), and injury severity (ISS > 15) were associated with increased odds of mortality [Table 5].

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for mortality in patients with an arterial blood gas pH ≤7.2 by arterial blood gas base deficit, International Normalized Ratio, Glasgow Coma Scale, systolic blood pressure (mmHg), and Injury Severity Score

| Variable | Crude | Adjusted* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| ABG BD | ||||||

| ≤−8 | 1.29 | 0.42-3.94 | 0.660 | 1.10 | 0.29-4.12 | 0.890 |

| >−-8 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| INR | ||||||

| >1.6 | 7.13 | 2.16-23.55 | 0.001 | 6.85 | 1.76-26.64 | 0.006 |

| ≤1.6 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| GCS | ||||||

| ≤8 | 2.15 | 0.85-5.44 | 0.106 | 0.93 | 0.26-3.24 | 0.912 |

| >8 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| SBP | ||||||

| ≤90 | 2.09 | 0.83-5.23 | 0.117 | 1.98 | 0.64-6.10 | 0.232 |

| >90 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| ISS | ||||||

| >15 | 2.83 | 0.80-10.07 | 0.108 | 2.61 | 0.61-10.97 | 0.192 |

| ≤15 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

*Each variable adjusted by other four variables and age, race, sex, and mechanism of injury. ABG: Arterial blood gas, CI: Confidence interval, OR: Odds ratio, BD: Base deficit, INR: International Normalized Ratio, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, SBP: Systolic blood pressure, ISS: Injury Severity Score

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for mortality in patients with an arterial blood gas pH 7.2-7.35 by arterial blood gas base deficit, International Normalized Ratio, Glasgow Coma Scale, systolic blood pressure (mmHg), and Injury Severity Score

| Variable | Crude | Adjusted* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| ABG BD | ||||||

| ≤−8 | 0.89 | 0.42-1.92 | 0.775 | 0.58 | 0.24-1.40 | 0.225 |

| >−8 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| INR | ||||||

| >1.6 | 8.29 | 2.86-24.09 | <0.001 | 8.35 | 2.58-26.99 | <0.001 |

| ≤1.6 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| GCS | ||||||

| ≤8 | 2.47 | 1.20-5.09 | 0.014 | 2.74 | 1.17-6.43 | 0.020 |

| >8 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| SBP | ||||||

| ≤90 | 2.08 | 0.92-4.73 | 0.079 | 2.29 | 0.86-6.09 | 0.096 |

| >90 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

| ISS | ||||||

| >15 | 4.80 | 1.83-12.61 | <0.001 | 4.79 | 1.67-13.74 | 0.002 |

| ≤15 | 1 (reference) | - | 1 (reference) | - | ||

*Each variable adjusted by other four variables and age, race, sex, mechanism of injury. ABG: Arterial blood gas, CI: Confidence interval, OR: Odds ratio, BD: Base deficit, INR: International Normalized Ratio, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, SBP: Systolic blood pressure, ISS: Injury Severity Score

DISCUSSION

We observed that trauma patients presenting with acidosis (pH ≤ 7.2) have greater odds of mortality, particularly with severe acidosis (pH ≤ 7.0), who have 25-fold greater odds of mortality than trauma patients without acidosis. However, even in the severe acidosis group, some patients do survive. On the other hand, trauma patients with more moderate, or compensated, acidosis (pH 7.2–7.35) have odds of mortality no greater than those without acidosis (pH > 7.35) on presentation. For those patients with a pH ≤ 7.2, coagulopathy (INR > 1.6) increased the odds of mortality.

Our findings are consistent with prior reports of acidosis in trauma patients being associated with increased mortality, whether measured by pH, lactate, or base deficit.[6] The single best measure of acidosis either as a marker for resuscitation or a marker for prognosis has been debated. Base deficit has been shown to be a better predictor of outcome than pH, while lactate has been reported be a better predictor of outcome than base deficit.[7,8,9] Recently, it has been suggested that succinate may be the most sensitive marker for severe shock.[10] We did not have lactate levels available for our population, thus our analysis was restricted to pH and base deficit as measures of acidosis. In contrast to pH, while patients with a base deficit ≤−8 had a significantly higher mortality, a base deficit ≥−8 was not associated with significantly increased odds of mortality in the adjusted logistic models. While the reason why base deficit was not associated with mortality is not completely clear, it may be because the cutoff of ≤−8 was too conservative. We selected a base deficit of ≥−8 because it was the 75th percentile value in our population and because a base deficit ≥−8 was associated with increased morbidity and mortality in other studies.[6,7,11] Had we chosen a lower value reflecting more severe metabolic acidosis, we may have been able to identify a population with a higher mortality.[6,12] However, there were only a small numbers of patients with base deficits much greater than 8, which would have limited our ability to draw meaningful conclusions from this cohort.

Our findings suggest that patients with less severe acidosis (pH > 7.2) are less likely to die. The ability of patients to respiratory compensate may be an important factor in explaining this finding, which is supported by an earlier study of severe acidosis in which lower pCO2 was found to be associated with a better prognosis.[4] The potential importance of compensation is suggested by our finding that a high base deficit is less likely to be associated with an increase in mortality if the pH is > 7.2 in contrast to comparable base deficits with a pH < 7.2. It has been observed that trauma patients who do not adequately compensate for metabolic acidosis are much more likely to require intubation.[13]

Similar to other studies, we observed that patients with pH ≤ 7.0 have a high mortality, but some of these patients do survive.[4,5] Overall, patients with pH ≤ 7.0 make up a very small percentage of the entire trauma population. In the select population represented in our study, only 5% of the patients had the most severe acidosis (pH ≤ 7.0); the percent with severe acidosis would certainly be much lower in the total trauma registry population. Despite the high mortality in the small number of trauma patients who present with severe acidosis, the survival of some of these patients supports aggressive resuscitative therapies in these patients. In fact, a recent study found that the initiation of a massive transfusion protocol for resuscitation improved mortality in those patients with the most severe metabolic acidosis (base deficit ≥24).[12]

Our data suggest that treatment of acidosis should be directed toward those patients with a pH < 7.2. Further, the data also support a pH goal of >7.2 for resuscitation. However, the question remains how best to intervene. It has been suggested that that bicarbonate therapy for acidosis is not only ineffective in improving outcome, but may in fact increase mortality.[14] Similarly, there are little data supporting the efficacy of bicarbonate therapy in patients with lactic acidosis.[15,16] In fact, bicarbonate can cause increase in intracellular pH as well as increase in lactic acid production.[17] The improved outcomes we observed in patients with less severe or compensated acidosis suggest that efforts directed toward lowering pCO2, including early initiation of mechanical ventilation, should be considered. It may be that using better markers of acidosis to guide resuscitation, such as succinate, may be important moving forward.[10]

Interestingly, in the cohort of acidotic patients with a pH ≤ 7.2, we found that coagulopathy as measured by INR was the only variable associated with increased odds of mortality. This is in contrast to patients with less severe acidosis (pH 7.2–7.35) where neurologic status and severity of injury are also associated with increased odds of mortality. While coagulopathy is a major component of the classic “lethal triad,” the use of INR as a measure of coagulopathy in trauma patients has been questioned.[3] Endo et al. have suggested a revision of the “lethal triad” that uses fibrinolytic markers rather than INR as the measure of coagulopathy.[3] We did not have other markers of hemostasis available for our analysis, however, given our findings, markers reflecting hemostasis or coagulopathy may provide therapeutic goals in the treatment of trauma patients presenting with acidosis.

There are several limitations inherent to this retrospective study that warrant mention. A large number of patients in the trauma registry were excluded because of the absence of critical values, in particular an ABG at presentation. It may be that these patients did not have an ABG because they were clinically stable, resulting in a selection bias yielding a population that was more severely injured than the general trauma population, reflected in the high mortality of 23%. Similarly, we may have missed some patients with metabolic acidosis because the ABG was not available. We were also limited in our ability to analyze more select cohorts in the acidotic population because it would have resulted in a sample size too small to yield meaningful statistical results. In particular, we do not have specific information on the subgroup of patients with severe hemorrhage. However, the fact that mechanism of injury (blunt vs. penetrating trauma) was not associated with changes in outcome suggests that the study findings may be applicable to acidosis independent of mechanism, including hemorrhage. Further study of this particular subgroup would be of interest. In addition, we used GCS as a surrogate for neurologic status. However, we recognize that GCS may be affected by factors other than traumatic brain injury. Finally, because this was a retrospective study, we can only describe associations, not determine cause and effect.

CONCLUSIONS

A pH ≤7.2 is associated with increased odds of mortality. On the other hand, this is not the case for those trauma patients with a pH >7.2 and a pH >7.2 may be an appropriate goal for resuscitation of acidotic patients. The ability of patients to compensate for acidosis appears to be important. For those patients with a pH ≤7.2, only the presence of coagulopathy is associated with increased odds of mortality. Therapeutic interventions facilitating the identification and correction coagulopathy in acidotic trauma patients should be explored.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Jordan GL., Jr Intra-abdominal packing for control of hepatic hemorrhage: A reappraisal. J Trauma. 1981;21:285–90. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore EE, Thomas G. Orr memorial lecture Staged laparotomy for the hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy syndrome. Am J Surg. 1996;172:405–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endo A, Shiraishi A, Otomo Y, Kushimoto S, Saitoh D, Hayakawa M, et al. Development of novel criteria of the “lethal triad” as an indicator of decision making in current trauma care: A retrospective multicenter observational study in Japan. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e797–803. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson R, Eidt J, Bitzer L, Wallace B, Collins T, Parks-Miller C, et al. Severe acidosis alone does not predict mortality in the trauma patient. Am J Surg. 1995;170:691–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80043-9. discussion 4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross SW, Thomas BW, Christmas AB, Cunningham KW, Sing RF. Returning from the acidotic abyss: Mortality in trauma patients with a pHet al. Admission base deficit and lactate levels in Canadian patients with blunt trauma: are they useful markers of mortality? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1532–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256dd5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis JW, Kaups KL, Parks SN. Base deficit is superior to pH in evaluating clearance of acidosis after traumatic shock. J Trauma. 1998;44:114–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199801000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale SC, Kocik JF, Creath R, Crystal JS, Dombrovskiy VY. A comparison of initial lactate and initial base deficit as predictors of mortality after severe blunt trauma. J Surg Res. 2016;205:446–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husain FA, Martin MJ, Mullenix PS, Steele SR, Elliott DC. Serum lactate and base deficit as predictors of mortality and morbidity. Am J Surg. 2003;185:485–91. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D´Alessandro A, Moore HB, Moore EE, Reisz JA, Wither MJ, Ghasasbyan A, et al. Plasma succinate is a predictor of mortality in critically injured patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:491–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberhard LW, Morabito DJ, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Campbell AR, Marks JD, et al. Initial severity of metabolic acidosis predicts the development of acute lung injury in severely traumatized patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:125–31. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200001000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodgman EI, Morse BC, Dente CJ, Mina MJ, Shaz BH, Nicholas JM, et al. Base deficit as a marker of survival after traumatic injury: Consistent across changing patient populations and resuscitation paradigms. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:844–51. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824ef9d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel SR, Morita SY, Yu M, Dzierba A. Uncompensated metabolic acidosis: an underrecognized risk factor for subsequent intubation requirement. J Trauma. 2004;57:993–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000114636.49433.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RF, Apencer AR, Tyburski JG, Dolman H, Zimmerman LH. Bicarbonate in severly acidotic trauma patients increase mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:45–50. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182788fc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper DJ, Walley KR, Wiggs BR, Russel JA. Bicarbonate does not improve hemodynamics in critically ill patients who have lactic acidosis. A prospective, controlled clinical study. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:492–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-7-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathieu D, Neviere R, Billard V, Fleyfel M, Wattel F. Effects of bicarbonate therapy on hemodynamics and tissue oxygenation in patients with lactic acidosis: A prospective, controlled clinical study. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:1352–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hood VL, Tannen RL. Protection of acid-base balance by pH regulation of acid production. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:819–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hood VL, Tannen RL. Protection of acid-base balance by pH regulation of acid production. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:819–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]