Abstract

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are the major lung-resident macrophages and have contradictory functions. AMs maintain tolerance and tissue homeostasis, but they also initiate strong inflammatory responses. However, such opposing roles within the AM population were not known to be simultaneously generated and co-exist. Here, we uncovered heterogenous AM subpopulations generated in response to two distinct pulmonary fungal infections, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Some AMs are bona fide sentinel cells that produce chemoattractant CXCL2, which also serves as a marker for AM heterogeneity, in the context of pulmonary fungal infections. However, other AMs do not produce CXCL2 and other proinflammatory molecules. Instead, they highly produce anti-inflammatory molecules, including IL-10 and C1q. These two AM subpopulations have distinct metabolic profiles and phagocytic capacities. We report that polarization of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory AM subpopulations is regulated at both epigenetic and transcriptional levels and that these AM subpopulations are generally highly plastic. Most importantly, out studies have uncovered the role of C1q expression in programing and sustaining anti-inflammatory AMs. Our finding of the AM heterogeneity upon fungal infections suggests a possible pharmacological intervention target to treat fungal infections by tipping the balance of AM subpopulations.

Introduction

Early host responses with innate immunity are crucial in exerting the initial antifungal immunity and the following regulation of inflammation. Among many players in innate immunity, tissue-resident macrophages are in the front line, sensing fungi infecting hosts through inhalation (1). Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are the most abundant resident immune cells in the alveoli of the lung. In addition to their roles in the maintenance of lung homeostasis and respiratory functions (2), AMs are the first line of immune defenders against pulmonary pathogens (3) and generally considered to be critical for host immunity. However, the role of AMs in pulmonary fungal infections is still largely elusive, particularly in vivo. For example, some articles report AMs to be protective, but others report them detrimental to hosts (4–7). Studying the role of AMs in vivo could be technically challenging – no Cre-lox mouse system to deplete AMs, limitation in capturing the biology in tissue culture, and the lack of a simple cell surface marker for AM identification. Such technical challenges hampered better understanding of the AMs in pulmonary fungal infection.

Cryptococcus neoformans (Cn) is an opportunistic fungus mainly infecting immunosuppressed patients by inhalation and causes more than one million life-threatening cases per year worldwide (8). The role of AMs in Cn infection is still elusive. A previous study showed that mice depleted of CD11c-expressing cells had increased neutrophil infiltration in the lung with severe lung inflammation (6). Because CD11c+ cells include both AMs and dendritic cells (DCs), it is still not clear if the anti-inflammatory role of CD11c+ cells were attributed to AMs, DCs, or both. Another study suggested a proinflammatory role of AMs by demonstrating their expression of proinflammatory molecules, such as CXCL1, CXCL2, and TNFα, upon Cn stimulation (9), but this result was drawn from a tissue culture set-up. Because behaviors of tissue macrophages are shaped by in vivo environment, responses of AMs ex vivo need to be re-evaluated in vivo. Also, in many reports, the identification of AMs was not strict either, e.g., only a couple of cell surface markers were applied to define AMs. Thus, understanding the role of AMs in vivo requires more defined approaches and tools.

In this study, we demonstrated that AMs are not only the lung sentinels responding to fungal infections, but also exhibit heterogeneous immune responses with distinct patterns in gene expression and metabolic profiles within the AM population. CXCL2+ AMs express pro-inflammatory molecules and are generated at the gene transcription levels. In contrast, CXCL2- AMs express anti-inflammatory molecules and generated at the epigenetic level. Furthermore, we found that AM gene expression pattern is plastic, except for C1q, which sustains in CXCL2- AMs. This study presents the co-existence of two distinct AM subpopulations upon pulmonary fungal infection.

Results

Alveolar macrophages are immune sentinels in the context of pulmonary Cryptococcus infection

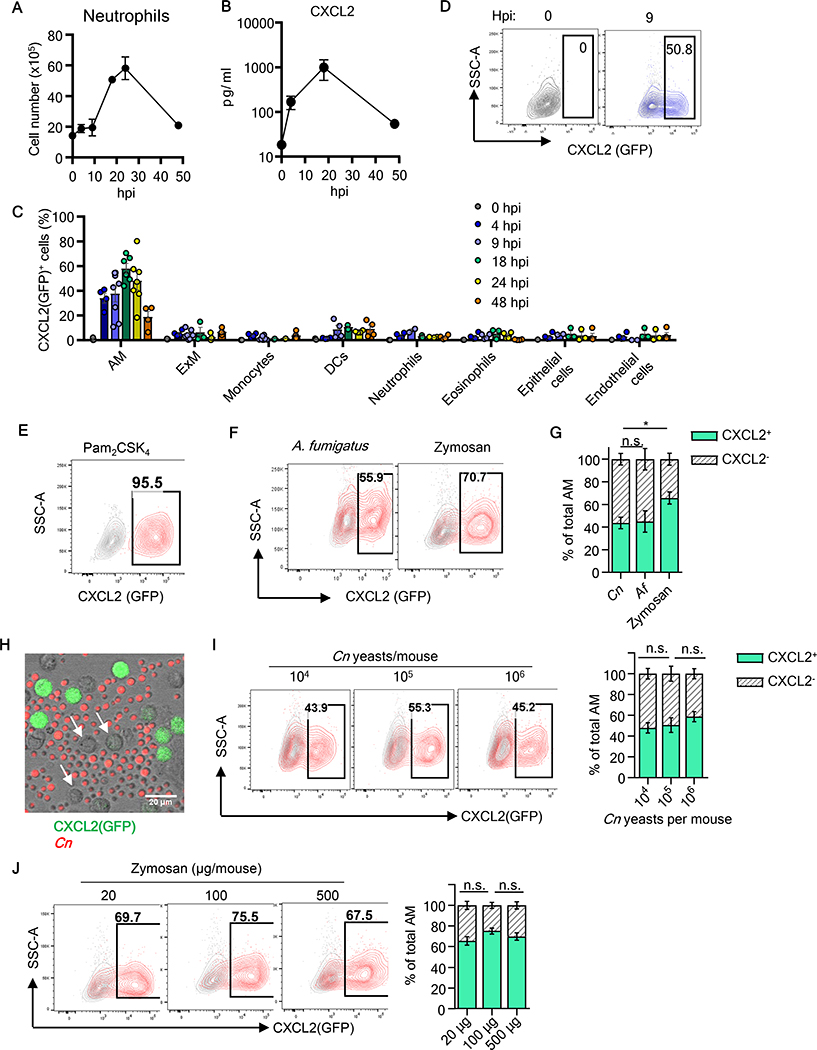

Cryptococcus covers its cell wall surface with a polysaccharide capsule to evade immune recognition (10, 11) and known to scarcely elicit immune responses at least in tissue culture (12, 13). Therefore, we sought to examine in vivo host responses against C. neoformans (Cn) in the first 48 hours after instillation of Cn H99 strain by oro-tracheal (o.t.) aspiration (we use a term “instillation” for this procedure hereafter). As an early host response, we first evaluated lung infiltration of neutrophils. Although Cn is known to be weakly immunogenic, neutrophil infiltration in the lung was observed, peaking at 24 hours post instillation (hpi) (Fig. 1A). Concentrations of CXCL2, a critical neutrophil chemoattractant, in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) also showed a great increase peaking at 20-hpi (Fig. 1B). To identify the cellular source of CXCL2 in the lung, we used an in vivo CXCL2-GFP mouse reporter system (14). The reporter mouse line is a Cxcl2 knock-in with Egfp (described as “Gfp” hereafter) insertion at the 3’-proximal end of the CXCL2-encoding sequence. The sequence encoding “2A self-cleaving peptide,” inserted between Cxcl2 and Gfp coding regions, cleaves the CXCL2-GFP nascent peptide to generate two separate functional proteins of CXCL2 and GFP (14). The promoter region of Cxcl2 is intact and derived from a BAC vector. Correlation between the expression levels of GFP and CXCL2 was confirmed by Hohl and colleages (14) and by us (fig. S1A). CXCL2-GFP reporter mice were instilled with Cn, and the lung was harvested to analyze total lung cells by multi-color flow cytometry. AMs were defined with slight modifications of a previous report (15), as SiglecFhiCD64+Ly6G-Ly6C-CD45+CD24-CD11c+ (fig. S1B). GFP expression was evaluated in various lung cells in the first 48-hpi, and the result showed that AMs are the main cell types expressing CXCL2-GFP throughout the period (Fig. 1C). Expression of CXCL2(GFP) was identified as early as 4-hpi, and 40~60 % of AMs remained CXCL2(GFP)-positive up to 24-hpi (Fig. 1C, D). (Strictly speaking, CXCL2(GFP)-positive AMs are GFP+ AMs, but we will use the terminology CXCL2+ AMs hereafter.) At 48-hpi, the proportion of CXCL2+ AMs reduced to 20 % (Fig. 1C). In contrast, less than several % of cells expressed CXCL2 in the other cell types, including epithelial and endothelial cells (Fig. 1C; fig. S1C), which were previously reported as immune sentinel cells in Aspergillus fumigatus (Af) infection (14). Of note, no cells from naïve mice, including AMs, expressed CXCL2(GFP) (Fig. 1C, D), indicating the strict control of CXCL2 protein expression before stimulation. These results suggested AMs as the main immune sentinels in the lung after Cn instillation to produce CXCL2.

Fig. 1. Primary response of AMs to pulmonary fungal stimulation.

(A, B) Mice were instilled with Cn (104 yeast cells/mouse). Neutrophil recruitment in the lung at indicated times after infection (A). CXCL2 protein level in BALF (B). (C) Percentage of CXCL2/GFP-positive cells in indicated cell type at time points. One data point reflects data from one mouse. (D) Representative contour plots of CXCL2 (GFP) expression in AMs from naive mice and 9-hpi with Cn. (E-G) CXCL2-GFP reporter mice were instilled with Pam2CSK4 (12.5μg/mouse) (E), Af (107 conidia/mouse), or zymosan (100μg/mouse) (F), and AMs were analyzed at 16-hpi. Statistical comparison of frequencies between CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs (G). (H) Representative microscopic image of AMs (pooled from 3 naïve CXCL2-GFP mice) and heat-killed AF647-labeled Cn yeasts (red) at 16-hr after co-culture at MOI of 5. CXCL2(GFP) non-expressing AMs are indicated with arrows. (I, J) Representative plot and statistical comparison of AMs CXCL2(GFP) expression from mice instilled with titrated amount of Cn (I) or zymosan (J) at 16-hpi. At least 3 mice per group. Data were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-test. All bar graphs show means ± SEM. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Heterogenous AM responses are not attributable to fungal inocula, spatial localization, and the ontogenic origin of AMs

Instillation of a TLR2 ligand Pam2CSK4 induced nearly all the AMs to express CXCL2(GFP) (Fig. 1E). However, a significant proportion of AMs remained CXCL2- after Cn instillation (Fig. 1C, D), as well as instillation of Af conidia and zymosan (a fungal cell wall component ligating dectin-1 and TLR2) Fig. 1F, G). To understand why about half of the AM population are CXCL2- after instillation of fungal components, we first asked if the concentration of Cn yeasts was sufficient by co-culturing Cn yeasts and AMs collected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to ensure sufficient Cn-AM contact. However, we still noticed a significant proportion of CXCL2- AMs throughout the period of observation (Fig. 1H). Next, we examined if fungal inocula were not sufficient to induce all AMs to express CXCL2 in vivo. However, increased Cn inocula did not enhance the proportions of CXCL2+ AMs (Fig. 1I), neither did increased amounts of zymosan (Fig. 1J).

We have shown that Cn, Af, and zymosan instillations generate CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AM subpopulations (Fig. 1D, F, G). As CARD9 is critical in fungal detection by C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) (16), Card9−/− CXCL2-GFP reporter mice were evaluated to determine whether CXCL2 expression by AMs requires CARD9. Percentage of CXCL2+ AMs and expression levels of CXCL2-GFP in the cells were significantly decreased in Card9−/− AMs (fig. S2A–C). In addition, recruitment of neutrophils was significantly compromised (fig. S2D), although recruitment of monocytes was not affected (fig. S2E). These result suggested CARD9 is required in generating full-fledged CXCL2-expressing AMs by Cn instillation.

We then asked if the presence of CXCL2- AMs is accounted by the lung structure, possibly preventing the access to fungi. We examined the locations of CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs in the airway and parenchyma of Cn-infected lungs (fig. S3A–E). However, both regions showed statistically comparable ratios of CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs (fig. S3F). Fluorescent lung histology further showed that CXCL2+CD11c+ cells could be either proximal or distal from Cn cells in tissue (fig. S3G–J).

Next, we sought to investigate if the CXCL2 expression pattern depends on developmental origins by using a mouse fate-mapping (FM) approach. Recent studies demonstrated the significant contribution of embryonic yolk sac (YS) and/or fetal liver monocytes (FL-mo) to tissue macrophages (17, 18). Multiple FM mouse tools are available. But we chose to use the Flt3Cre FM system, since it labels cells that went through definitive hematopoiesis (17, 19, 20). Except for slightly lower proportions of CXCL2+ AM in FLT3-FM+ AMs at 9-hpi, Cxcl2-Gfp; Flt3Cre; Rosa26 LSL-tdTomato mice showed no major differences between FLT3-FM- and FLT3-FM+ AMs in percentages of CXCL2+ AMs upon Cn instillation (fig. S4A, B). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data at 9-hpi with Cn also did not indicate notable gene expression differences between FLT3-FM- and FLT3-FM+ AMs (fig. S4C). Thus, the ontogenic origin does not distinguish CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs. Further examination comparing female versus male (fig. S5A) and young versus old mice (fig. S5B) ruled out a clear involvement of sex and age either. These results suggested the presence of CXCL2- AM populations are neither attributed to the lack of sufficient AM-fungus contact, sub-optimal amounts of fungal inocula, AMs physical localizations in the lung, the developmental origin, nor sex and age of mice.

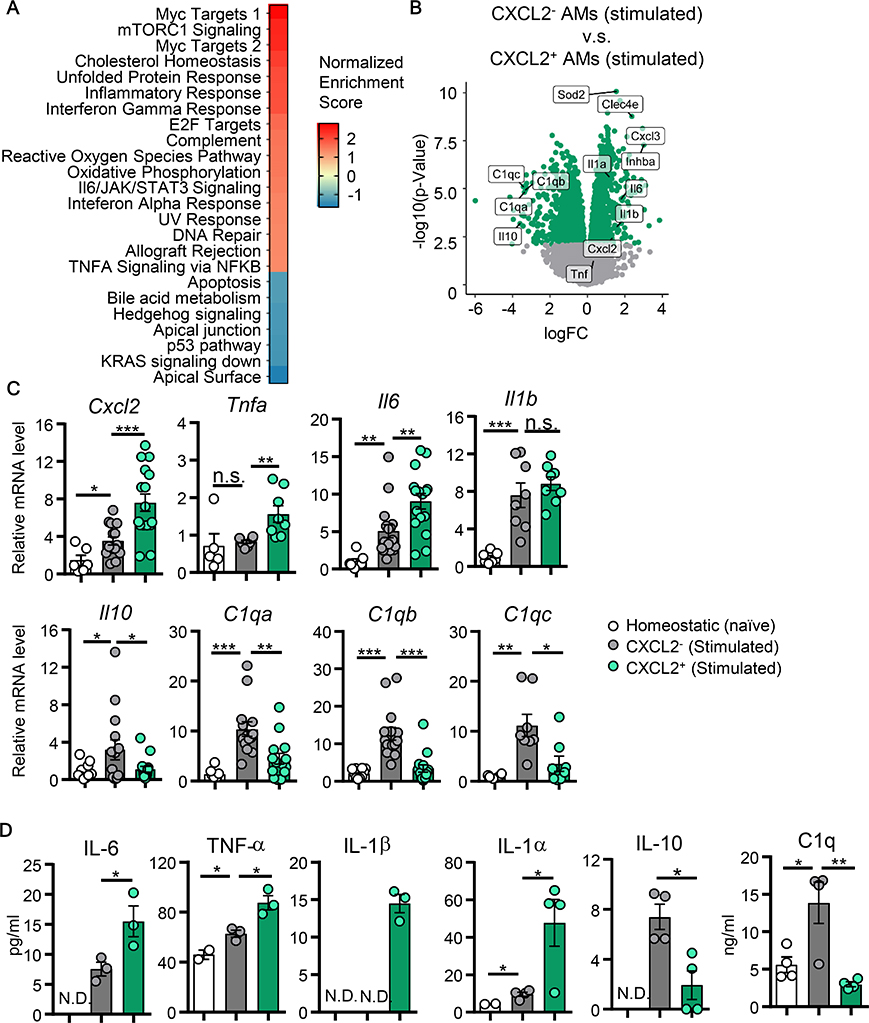

CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs exhibit distinct gene expression patterns

RNA-seq analysis of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs from Cn-instilled mice at 9-hpi revealed that CXCL2+ AMs were characterized with enriched expression of genes involved in proinflammatory signature pathways (Fig. 2A; S6A). In contrast, CXCL2- AMs expressed significantly high levels of anti-inflammatory Il10 and the C1q family genes (21) (Fig. 2B). Gene expression patterns of CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs are also distinct from naïve AMs (fig. S6B, C). We confirmed the RNA-seq results by qPCR (Fig. 2C) and ELISA (Fig. 2D). Particularly, CXCL2- AMs highly secreted IL-10 and C1q (Fig. 2D). IL-10 is a typical anti-inflammatory molecule, and C1q is also known for its anti-inflammatory role (22). This pattern of pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression between CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs was also induced by zymosan instillation (fig. S6D). Of note, CXCL2- AMs also enhanced mRNA expression of Maf and Mafb (fig. S6E), encoding transcription factors (TFs), Maf and MafB, which activate expression of Il10 and a series of C1q genes (23, 24). Thus, RNA-seq suggested the active involvement of CXCL2- AMs in suppressing inflammation.

Fig. 2. CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs have distinct gene expression profiles.

CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs were isolated from either CXCL2-GFP reporter naïve mice or mice instilled with Cn (104 yeasts/mouse). (A) Top-ranked statistically significant GSEA hallmark pathways in CXCL2+ AMs compared to CXCL2- AMs at 9-hpi. (B) Differentially expressed genes in CXCL2+ compared to CXCL2- AMs at 9-hpi. Statistically significant genes are indicated with green dots (FDR corrected p<0.05). (C) Gene expression analysis by qPCR. RNA lysates for qPCR were obtained at 9-hpi by FACS-sorting CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs subpopulations. Data for each gene were shown as fold changes to values in homeostatic AMs from naïve mice. Each data point reflects data from one mouse. (D) Protein expression was evaluated by multiplex beads flow cytometry, except for C1q levels detected by ELISA. Protein samples were supernatants of 2-day cell culture of FACS-sorted CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs at 9-hpi. Each data point reflects data from one culture plate well, including AMs pooled from at least 3 mice. All bar graphs show means ± SEM. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, as calculated using non-paired Student’s t-test. N.D.: not detectable. hpi: hours post infection. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

We then asked if CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs fit the M1/M2 paradigm (25). We composed a customized gene set using differentially expressed genes (Table S1) based on polarized M1/M2 bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) (26). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of CXCL2+ AM transcriptomes revealed enrichment of M1-like macrophage signature genes but CXCL2- AMs did not upregulate signature genes of M2-like macrophages (fig. S6F). For example, a typical M2 marker Arg1 (27) was not particularly highly expressed in CXCL2- AMs. In summary, our data indicated that CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs highly express pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes, respectively, but they do not fit into the M1/M2 paradigm.

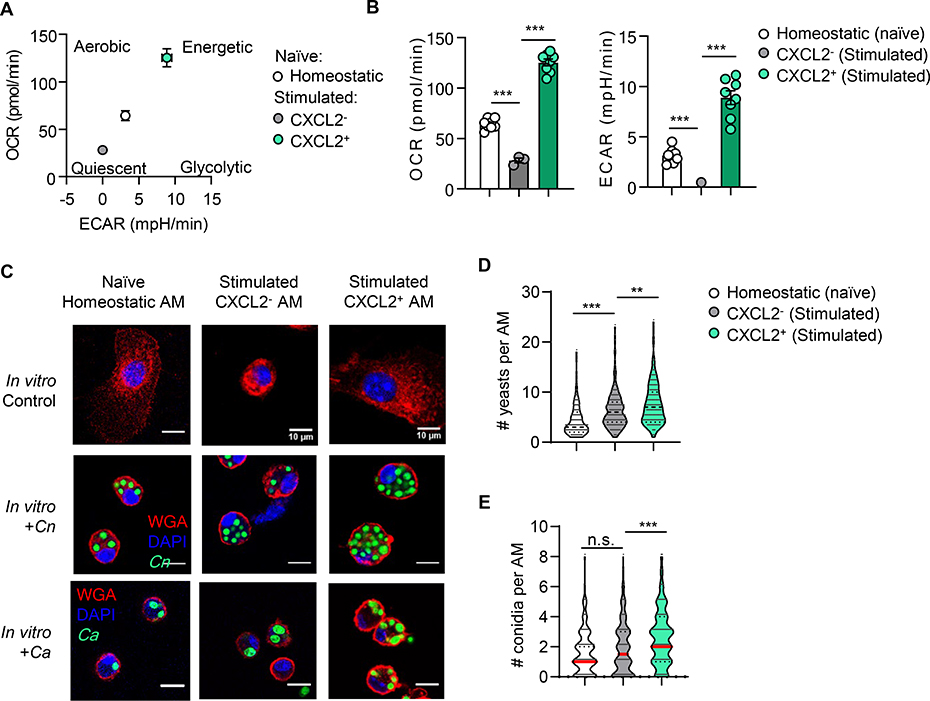

CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs have distinct metabolic profiles and phagocytic capacities

We further evaluated the metabolic phenotype of AMs using a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer to compare the bioenergetic profiles in CXCL2-, CXCL2+ AMs, and homeostatic AMs from naïve mice. CXCL2+ AMs were highly energetic with high baseline oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), indicating highly active glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 3A, B). Additionally, CXCL2+ AMs have significantly higher ATP production and maximal respiration compared to CXCL2- AMs (fig. S7A, B), indicating high mitochondrial respiratory capacity. This is in accordance with mTORC1 signaling pathway enriched in CXCL2+ AMs (fig. S7C), as cells enriched in mTORC signaling have higher mitochondrial respiration (28, 29). In contrast, CXCL2- AMs were quiescent with low OCR and ECAR, which were even lower than homeostatic AMs (Fig. 3A, B). The data again indicated that CXCL2- AMs are distinct from unstimulated AMs. Of note, The OCR data of CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs again does not fit the metabolic characters of the M1/M2 paradigm: M1 and M2 have low and high OCR, respectively (30). Our RNA-seq data, indicating highly expressed genes related to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in CXCL2+ AMs (Fig. 3A), also does not fit enhanced OXPHOS in M2 macrophages (31, 32). We also observed higher apoptotic profile of CXCL2- AMs than CXCL2+ AMs at 16-hpi with Cn (fig. S7D, E). Reflecting the quiescent metabolic state, CXCL2- AMs were also small in size with a spherical shape (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs have distinct metabolic profiles and phagocytic capacity.

Three AM groups (homeostatic AMs from naïve mice, CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs from 16-hpi mice) were FACS-sorted and cultured ex vivo for 2 days. (A, B) OCR and ECAR of AM populations were analyzed with the Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer. (B) Statistical comparison of OCR vs. ECAR of AM at the basal level. (C-E) Representative images of AMs co-cultured with either GXM Ab-opsonized Cn yeasts or heat-killed Ca conidia (MOI of 5), incubated for 2 hours (C). Statistical analysis of numbers or Cn yeast (D) or Ca conidia (E) engulfed by each AM, based on at least 100 AMs per condition. One well consists of AMs pooled from 3–4 mice. One data point denotes a result from an individual well (B), or a single cell (D, E). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test results are indicated as *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, n.s.: not significant. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Next, we evaluated macrophage phagocytosis. Although the phagocytic ability of CXCL2+ AMs was similar to that of CXCL2- AMs in latex beads uptake (fig. S7F), CXCL2+ AMs endocytosed more numbers of antibody-opsonized Cn yeasts per macrophage (phagocytic “capacity”) compared to CXCL2- AMs (Fig. 3C, D). Fc receptors, which are required for antibody-mediated phagocytosis, are expressed comparably or higher in CXCL2- than CXCL2+ AMs (fig. S7G). We also observed higher CXCL2+ AMs phagocytic capacity during endocytosis of Candida albicans (Ca) conidia (Fig. 3C. E), which does not require antibody opsonization as phagocytosis of Cn does. These results indicated that CXCL2+ AMs are metabolically active with a high phagocytic capacity, while CXCL2- AMs are metabolically more quiescent than homeostatic AMs.

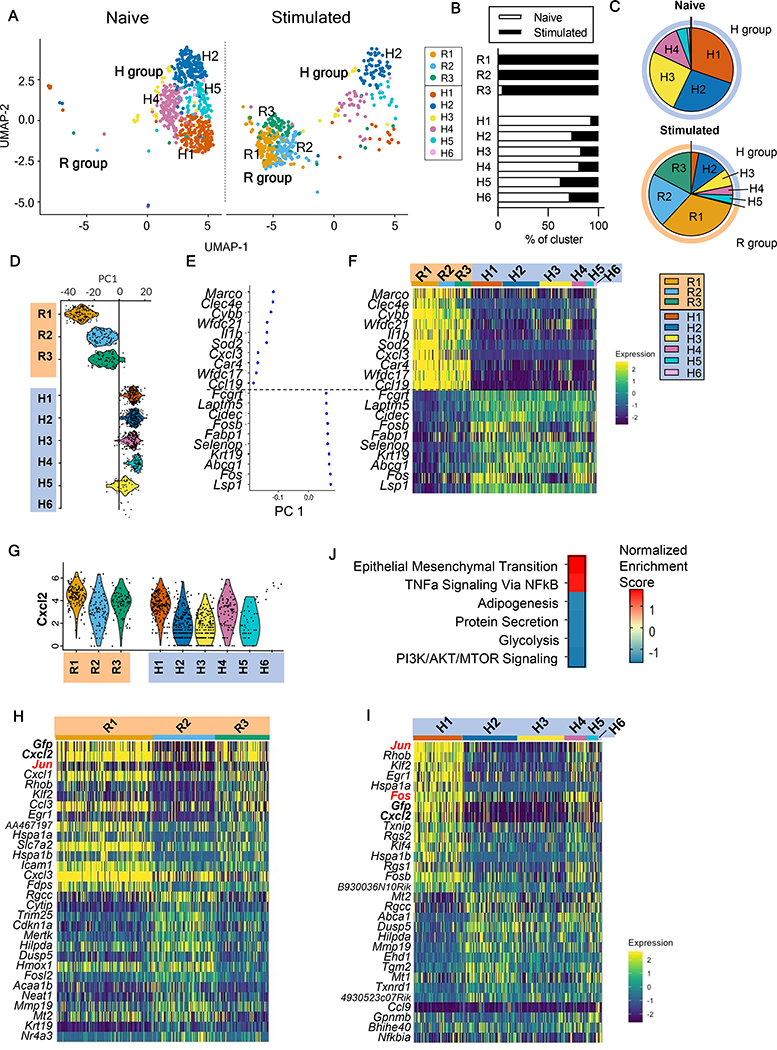

Heterogeneity of AM response to Cryptococcus at the single-cell level

We further addressed the following questions by using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq): (1) Are there distinct activated AM populations expressing no or low Cxcl2 mRNA (denoted as “Cxcl2lo mRNA AMs” hereafter) after Cn instillation? (2) Are activated Cxcl2lo mRNA AMs truly a distinct subpopulation? (3) Is Cxcl2 mRNA expression a robust marker reflecting distinct transcriptional programs, beyond its functional importance as a neutrophil-recruiting chemokine?

We isolated CD45+ cells from lung homogenates of CXCL2-GFP reporter (heterozygous) mice at 9-hpi and naïve controls, and processed samples for scRNA-seq using the 10X Genomics Chromium platform (fig. S8A, B; Supplemental Methods). We classified lung CD45+ cells into major immune cell populations using reference-based annotation (fig. S8C, D; fig. S9A) and observed that neutrophils were the only population with significant increase in cell numbers after Cn instillation (13% in naïve vs. 38% in stimulated group) (fig. S9B). Next, we confirmed the identified AM cluster (fig. S9A) by canonical cell markers in comparison to other myeloid populations (fig. S9C). Unsupervised clustering divided AMs further into distinct subpopulations (fig. S9D, E). After filtering out proliferating and putative multiplet cells, we identified dramatic shift in AM transcriptional profile between AM samples from mice with or without Cn instillation (Fig. 4A). Hierarchical clustering (fig. S9F) indicated that the cells were divided into two major branches, named responsive (R) or homeostatic (H), because the H cluster is the major AM subpopulation in the naïve lung (Fig. 4B, C). Of note, R and H clusters are clearly divided, and an intermediate or transition state is not apparent based on UMAP projection or hierarchical clustering.

Fig. 4. scRNA-seq analysis of alveolar macrophages (AM) following acute C. neoformans exposure.

(A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of AMs from naïve mice and Cn-instilled mice at 9-hpi (stimulated). Annotation of groups, R: Responsive, H: Homeostatic. (B) Frequencies of AM sources (naive or stimulated mice) composing each cluster. (C) Frequencies of AM clusters in lungs from naive or stimulated mice. (D) Violin plot of principle component 1 (PC1) scores for each cluster. (E, F) Top highly expressed genes contributing to PC1 clusters with corresponding PC1 scores (E) and heatmap of row-scaled gene expression (F). (G) Violin plot of Cxcl2 expression across AM clusters. (H, I) Gene expression heatmap of top genes differentially expressed among R-group clusters (H) and H-group clusters (I). (J) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of comparison between Cxcl2hi mRNA (R1,R3) and Cxcl2lo mRNA (R2) AM clusters. Heatmap of normalized enrichment score (NES).

The first principal component analysis (PCA) was able to clearly distinguish the R and H clusters (Fig. 4D). We found that immune receptors (Clec4e, Marco) and cytokines (Il1b) were upregulated in R groups compared to H groups (Fig. 4D–F), while genes involved in lipid binding and transport (Cidec, Fabp1, Abcg1) were downregulated, likely reflecting downregulation of homeostatic surfactant processing mechanisms (33). These data demonstrated that majority of AMs from Cn-instilled mice were activated and can be differentiated from homeostatic AMs with distinct immune receptor markers.

CXCL2 is a robust marker to differentiate AM subpopulations

We used CXCL2-GFP reporter mice in this study. Thus, we asked if Cxcl2 expression can truly serve as a robust marker to distinguish AM subpopulations. Cxcl2 was identified as a top contributor in our PCA of AMs (Data File S2C), suggesting that Cxcl2 mRNA is indeed a robust marker for identifying AM heterogeneity. Although the R clusters overall showed elevated Cxcl2 mRNA expression, we still observed Cxcl2hi mRNA (R1, R3) and Cxcl2lo mRNA (R2) clusters (Fig. 4G). Of note, levels of Cxcl2 mRNA and Gfp mRNA were highly correlated in both R and H AM clusters, validating the robustness of the reporter system (Fig. 4H, I). Notably, the R2 cluster with low Cxcl2 mRNA expression was not found in naïve lungs (Fig. 4A, B). In addition, the Cxcl2lo mRNA R2 cluster is distinct from the H cluster branch (fig. S9F). These findings confirmed that Cxcl2lo mRNA R2 AM subpopulation are in fact activated but have an alternative activation phenotype distinct from Cxcl2hi mRNA (R1, R3) AMs.

Next, we compared Cxcl2hi mRNA (R1, R3) and Cxcl2lo mRNA (R2) AMs (Data File S2D, E) and found that R1 and R3 were enriched in pathways including TNFα signaling via NFκB (Rhob, Jun, Klf2, Cxcl2, Egr1; Fig. 4H, J), consistent with the pro-inflammatory phenotype of CXCL2+ AMs from bulk RNA sequencing data (Fig. 2A). In contrast, R2 cluster showed enrichment in pathways involved in cellular maintenance, such as adipogenesis (Angpt14, Dgat1, Abca1), protein secretion (Cltc, Abca1, Arf1), and glycolysis (Cd44, Taldo1, Me2, Mertk) (Fig. 4H, J). In addition, R2 cluster showed elevated expression of genes with known roles in regulating inflammation in the setting of lung injury such as the efferocytosis receptor tyrosine kinase Mertk and antioxidant metallothioneins Mt1/Mt2 (34, 35), along with inhibitors of MAPK/ERK signaling Dusp5 and Dusp3 (36). These observations agreed with our bulk analysis that CXCL2 is one of the markers that serve to distinguish heterogenous AM populations.

Elevated levels of Cxcl2 mRNA in AMs in the H1 cluster

We also sought to characterize the heterogeneity within the homeostatic (H) AMs. In particular, we noticed that the H1 cluster showed elevated Cxcl2 mRNA compared to the remaining H clusters (Fig. 4G, I). To confirm the finding, we reanalyzed a previously published data (37) and identified the presence of a homeostatic AM subpopulation expressing elevated Cxcl2 mRNA in naïve mice (indicated as cluster 2 in fig. S10A–C). We also identified the Cxcl2 mRNA pre-loaded AM subpopulation from naïve mice by flow cytometry using Prime flow RNA assay (fig. S10D, F). The pre-loaded AMs were still present after antibiotics treatment, as well as in germ-free mice (fig. S10D, E), ruling out microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs)-dependent cell stimulation. Furthermore, the Cxcl2 mRNA pre-loaded cells were not observed in other cell types, such as monocytes, neutrophils, or peritoneal macrophages as another tissue-resident macrophages (fig. S10F, G).

Differential gene expression analysis revealed that H1 AMs highly expressed genes encoding AP-1 transcription factors (TFs), including Jun and Fos (Fig. 4I; Data File S2F). Not only are AP-1 TFs enriched in homeostatic H1 AMs, but we also found elevated Jun expression in responding R1 and R3 AMs (Fig. 4H). Considering that AMs from naïve mice do not express CXCL2 protein (Fig. 1C, D), these results suggested that some homeostatic AMs in steady state may be poised to express CXCL2 protein by pre-loading Cxcl2 mRNA even without microbiota.

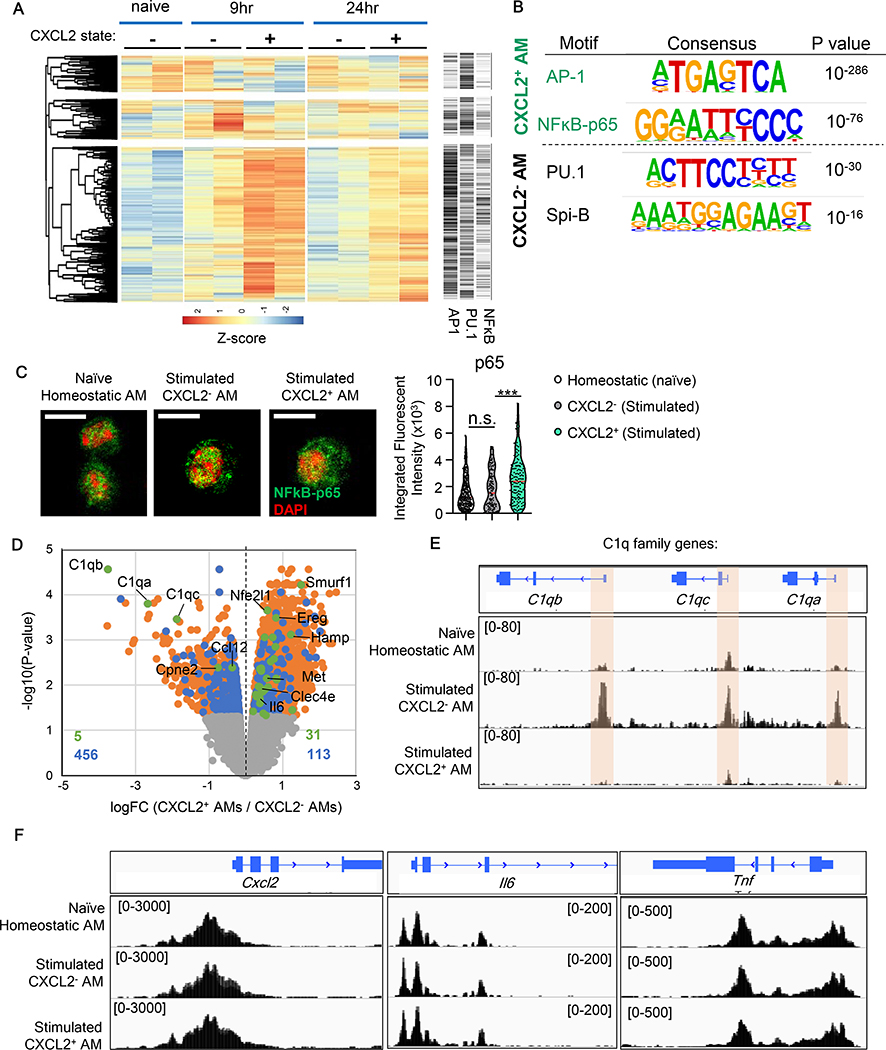

Epigenetic wiring of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs

Distinct patterns in cytokine production and metabolism between CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs implied differential epigenomic profiles. Here, we used transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) to evaluate CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs at 9 and 24-hpi with Cn, as well as homeostatic AMs. Differentially accessible (DA) regions were identified at both time points (Fig. 5A). The data also indicated that the subpopulation-specific enhancement in chromatin accessibility last at least 24-hpi (Fig. 5A). We then performed a de novo motif enrichment analysis of significant DA regions in CXCL2+ versus CXCL2- AMs to determine which TF-binding sequence may be enriched for specific genes in each subpopulation. In CXCL2+ AMs, consensus binding motifs for AP-1 and NKκB-p65 were the two most significantly enriched of all (Fig. 5B). This was particularly notable, as our scRNA-seq analysis identified highly expressed AP-1 transcription factors, including Jun in R1, R3, and H1 AMs with Cxcl2hi mRNA (Fig. 4H, I). These TFs are known to activate genes, such as Cxcl2, Il6, and Tnf (38), which were also upregulated in CXCL2+ AMs (Fig. 2B, C). Furthermore, enhanced nuclear translocation of NFĸB-p65 was observed in CXCL2+ AMs, suggesting highly active NFĸB-p65, compared to CXCL2- AMs (Fig. 5C). In contrast, CXCL2- AMs were enriched with the consensus motif of PU.1 (Fig. 5B), which is the main TF for C1q genes (39). Another enriched motif in CXCL2- AMs is Spi-B, which provides complementary biological functions of PU.1 and can be functionally replaceable to PU.1 in macrophages (40, 41).

Fig. 5. ATAC-seq analysis of homeostatic, CXCL2-, and CXCL2+ AMs.

(A) Hierarchical dendrogram and heatmap of the 5,000 most variable ATAC-seq regions in homeostatic (from naïve mice), CXCL2-, and CXCL2+ AMs (from Cn-instilled CXCL2-GFP reporter mice). CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs were collected at 9 and 24-hpi (Cn 104 yeasts/mouse). Right panel indicates predicted binding motifs of AP-1, PU.1, and NFκB in the corresponding regions in the dendrogram and heatmap. (B) Two most significantly enriched TF motifs accessible in CXCL2- or CXCL2+ AMs at 9-hpi with Cn. (C) Nuclear translocation of p65 NFκB. Representative images (left) and integrated p65 fluorescent intensity in nuclei (right). One dot denotes one cell (right). (D) Orange and blue dots indicate genes with DA regions by comparing CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs. Among them, genes with DA regions in promoters are indicated with blue dots. If the genes were further identified by RNA-seq as differentially expressed between the two AM subpopulations, they are shown with green dots. (E, F) Chromatin accessibility by ATAC-seq analysis in AMs at 9-hpi with Cn. Accessible regions in C1q subunit gene loci. Highlighted are significantly accessible regions (FDR<0.05) (E). Accessible regions in Cxcl2, Il6, and Tnf loci (F).

Some DA regions, between CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs, are found in promoters of the designated genes (blue dots in Fig. 5D), while others are not (orange dots in Fig. 5D). In particular, genes differentially expressed (DE) (identified by RNA-seq) and have DA promoters (identified by ATAC-seq), including C1qa, C1qb, and C1qc, are indicated with green dots in Fig. 5D. We also performed similar analysis to identify DE genes with DA promoters (referred as “DE/DA” hereafter) by comparing homeostatic AMs to either CXCL2+ or CXCL2- AMs (fig. S11A, B). Again, the DE/DA analysis identified the three highly accessible C1q loci in CXCL2- AMs (Fig. 5E), supporting the active gene expression of C1q in CXCL2- AMs at the epigenetic level. In contrast, no DE/DA genes in CXCL2+ AMs showed distinctly open chromatin as seen in C1q’s in CXCL2- AMs. For example, promoters of Cxcl2, as well as Il6 and Tnf, were equally accessible in CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs (Fig. 5F), despite of their high gene expression in CXCL2+ AMs (Fig. 2C). Taken together, generation of CXCL2- AMs and CXCL2+ AMs are suggested to be induced by the distinct levels of regulation by epigenetics and gene transcription, respectively.

C1q limits inflammation in the context of Cryptococcus infection

We have shown the distinct ability of CXCL2- AMs to produce C1q, as well as elevated C1q protein levels in BALF after Cn instillation (fig. S12A), but the function of C1q has not been studied in Cn infection. Here, due to the lack of the mouse system to deplete genes in an AM-specific manner, we used C1qa−/− mice. The lack of C1qa does not allow to form the complete C1q complex. First, the absence of C1qa in AMs did not alter CXCL2 production and CXCL2+ AM generation (fig. S12B, C). However, results clearly indicated the protective role of C1q, as demonstrated by C1qa−/− mice showing susceptibility in survival and weight loss (fig. S12D, E). Although WT and C1qa−/− mice showed similar fungal burdens in the lung, spleen, and brain (fig. S12F) and similar numbers of AMs, DCs, monocytes, and eosinophils in the lung (fig. S12G), C1qa−/− mice had increased neutrophil infiltration (fig. S12G) and proinflammatory cytokine levels in the lung (fig. S12H). Although the setting did not evaluate the impact of C1q secreted specifically by AMs, C1q was clearly demonstrated to limit pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and neutrophil recruitment in the lung during Cn infection.

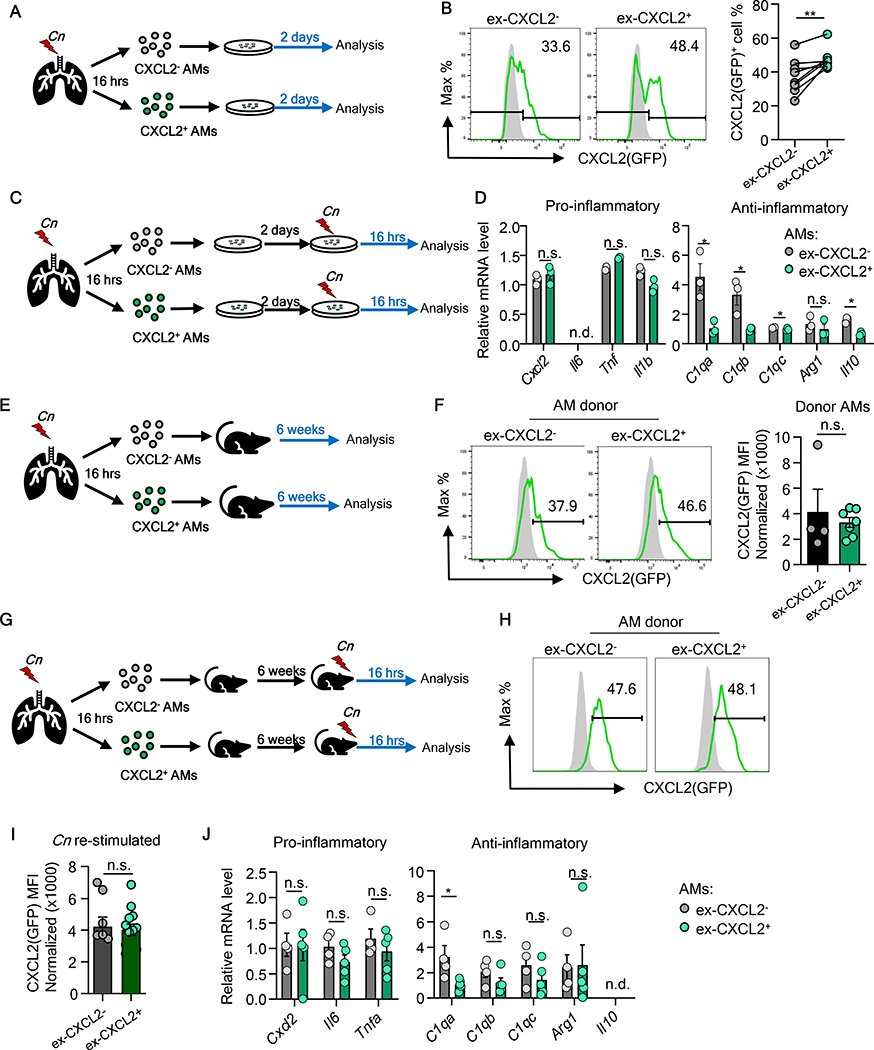

Plasticity of CXCL2+ and CXCL2- alveolar macrophges

We next evaluated the plasticity and fate of these distinct AM subpopulations. First, we harvested CXCL2- and CXCL2- AMs from Cn-instilled mice (designated as “ex-CXCL2-” and “ex-CXCL2+” AMs, respectively) and simply plated them in tissue culture for two days (Fig. 6A). No difference in apoptosis was found in tissue culture for 2 days (fig. S13A, B). Some ex-CXCL2- AMs expressed CXCL2, and some of ex-CXCL2+ AMs ceased CXCL2 expression (Fig. 6B). Therefore, although ex-CXCL2+ AMs still express more CXCL2 than ex-CXCL2- AMs after 2-day tissue culture (Fig. 6B), cell isolation and plating were sufficient to elicit the plasticity in CXCL2 expression. We next re-stimulated the ex-CXCL2+ and ex-CXCL2- AMs with heat-killed (HK) Cn for additional 16 hours in vitro after the initial 2-day culture (no FACS after ex vivo stimulation) (Fig. 6C), and found that ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs no longer had clear difference in expression levels of Cxcl2, Tnf, Il1b and Arg1 (Fig. 6D). However, notably, expression of C1qa, C1qb, C1qc, and Il10 remained high in ex-CXCL2- AMs (Fig. 6D). This ex vivo data suggested that isolation and ex vivo culture of AMs are sufficient to cause the pro-inflammatory gene expression profile indistinguishable, but the distinct expression of C1q genes and Il10 was retained.

Fig. 6. Plasticity of CXCL2- or CXCL2+ AMs gene expression ex vivo and in vivo.

(A, B) Evaluation of ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs kept in tissue culture (A). Representative flow panels and statistical data are shown to assess CXCL2(GFP) expression (B). (C, D) Evaluation of ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs stimulated with HK-Cn in tissue culture (C). Expression of indicated genes were evaluated by qPCR (D). (E, F) Evaluation of ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs in vivo after PMT (E) Representative histograms and MFI of CXCL2(GFP) expression (F). (G-J) Evaluation of ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs in vivo after PMT and Cn instillation (G). Representative histograms (H) and MFI (I) of CXCL2(GFP) expression, as well as expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes (J) are shown. Each data point reflects one well pooled from minimum 3 mice (B, D) or one single mouse (F, H-J). Paired (B) or un-paired Student’s t-test (D, F, I, J) were used for statistical evaluation. Data are representative of at least two independent repeats.

We next sought to determine the longevity and gene expression profile of ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs in vivo by using the pulmonary macrophage transfer (PMT) system (42). AM subpopulations are reconstituted in GM-CSF receptor-deficient (Csf2rb−/−) mice, which lack AMs but no other major cells in the lung, as described in a previous study (42) and confirmed by us (fig. S14A). Csf2rb−/− (CD45.2) neonatal recipients were intranasally instilled with FACS-isolated CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs (CD45.1/45.2) from Cn-instilled mice, as well as homeostatic AMs from naïve mice, and allowed AMs to colonize in the recipient lung for 6 weeks (fig. S14B). Successful colonization of AMs in Csf2rb−/− mice was observed indicated by the presence of similar numbers of CD45.1/45.2 double-positive ex-CXCL2-, ex-CXCL2+, and ex-homeostatic donor AMs (fig. S14C, D). The result first suggested that three groups of tested AMs can colonize alveolar niche to a similar extent in vivo.

To examine gene expression, we first examined the CXCL2 protein expression of donor ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs recovered from the Csf2rb−/− recipient mice. After 6 weeks post transfer without further infection, ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs expressed similar levels of CXCL2 shown as a single-peak CXCL2 expression pattern in flow cytometry histograms with similar MFIs (Fig. 6E, F). The result again indicated some ex-CXCL2- AMs turn to CXCL2-positive simply by isolating and incubating ex-CXCL2- AMs, as seen in tissue culture (Fig. 6B). Next, we infected Csf2rb−/− recipients with Cn 6 weeks after AM reconstitution. At 16-hpi, ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs showed comparable levels of CXCL2 levels (Fig. 6G–I). Reflecting the comparable CXCL2 expression levels between ex-CXCL2- and ex-CXCL2+ AMs, no difference was found in in neutrophil recruitment in the lung and survival of recipient mice (fig. S14E, F), as well as pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression between the donor AMs populations after Cn instillation to Csf2rb−/− recipients (Fig. 6J). Nevertheless, we again identified elevated C1qa levels in ex-CXCL2- AMs (Fig. 6J). In summary, our data implied that the distinct gene expression profile of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AM subpopulations at the early stage of Cn lung infection is generally plastic, but the expression of some anti-inflammatory genes in ex-CXCL2- AMs remains stable. In particular, the elevated expression of C1qa in ex-CXCL2- AMs lasted for 2 months in vivo.

Discussion

In this study, we report the presence of distinct AM subpopulations, CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs, at an early stage of Cryptococcus pulmonary infection. Here, CXCL2- AMs are cells neither left-out by stimulation nor the intermediate population at a snapshot of time, because they are distinct from homeostatic AMs in gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and metabolic signature.

Although it is not clear how heterogenous AM subpopulations are generated, our data suggested the following points. First, we speculate the involvement of distinct patterns in regulating two AM subpopulations. The status of signature gene expression in CXCL2- AMs is attributed to epigenetics, as seen in the chromatin accessibility of C1q loci in CXCL2- AMs. In contrast, CXCL2+ AMs do not show enhanced chromatin accessibility in Cxcl2, Tnf, and Il6 loci. Instead, CXCL2+ AMs appear to depend on the transcription machinery to shape them as proinflammatory AMs. CXCL2+ AMs highly expressed Jun and Fos and active nuclear translocation of NFκB p65. These results suggest the development of CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs generally depend on transcription and epigenetic mechanisms, respectively. Second, specific PRRs, ligated during AM stimulation, may play a role in the AM heterogeneity. We identified that a TLR2 ligand Pam2CSK4 completely shifts all the AMs to CXCL2+. Such a complete shift was achieved neither by Cn, Af, nor zymosan even with high inocula. Interestingly, zymosan (TLR2/Dectin-1 ligand) instillation generates CXCL2- AMs, but Pam2CSK4 (TLR2/6 ligand) instillation does not. One possibility is that zymosan is particulate, while Pam2CSK4 is not; thus, the solubility could matter. It is also possible that CXCL2- AM progenitors may specifically activate Dectin-1 signaling in an unconventional fashion. For example, a recent article suggested that Dectin-1 detects annexins on apoptotic cells and induces a tolerogenic response (43). All the fungal species may not work as Cn and Af in generating CXCL2- AM. Nevertheless, it will be of interest if the heterogeneity of AMs is specific to PRRs, involved in fungal detection. It would also be intriguing to examine if viral and bacterial infections shape the development of heterogenous AM responses.

We found that gene expression profiles in AMs is generally plastic. Except for C1qa gene expression maintained by CXCL2- AMs ex vivo and in vivo, gene expression patterns of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs are not stable. Such plasticity in gene expression is also reflected in the sharp decrease of CXCL2 protein expression in AMs in vivo after 24-hpi with Cn. The cessation of proinflammatory gene expression may well be necessary for the resolution of immune responses. AMs are tissue-resident macrophages, which are long-lived and self-sustained; thus, they may need to be plastic and adjustable when the environment changes. Otherwise, AMs would be stuck with an altered phenotype even after a single event of infection or tissue insult. But it is not desirable for hosts because the immune resolution is required. Thus, we interpret that the plasticity is helpful for AMs in adjusting to various conditions in tissues.

Our single-cell level analysis confirmed the heterogeneous gene expression among the AM population. Some homeostatic AMs express Cxcl2 mRNA, indicated as the H1 cluster, suggesting that these AMs are loaded with Cxcl2 transcripts but are not generating CXCL2 protein. Cxcl2 mRNA-loaded AMs in naïve mice are also identified in publicly available scRNA-seq data (37) by our data reanalysis. These peculiar Cxcl2 mRNA-loaded homeostatic AMs are found with an elevated frequency in germ-free mice, suggesting that the commensal microbiota negatively regulates the generation of the AM subset. We speculate that Cxcl2 mRNA-loaded H1 AMs under homeostasis would be the immune sentinel that quickly express CXCL2 to recruit neutrophils immediately after pulmonary fungal infections. Vice versa to the H1 cluster AMs, the R2 cluster AMs expressed reduced levels or no Cxcl2 mRNA even after Cn infection. We speculate that R2 AMs may be CXCL2- AMs. R2 AMs showed enrichment in genes that are known to inhibit cell cycle progression (Cdkn1a), MAPK signaling (Dusp3), and Rho GTPase signaling (Arhgdia), suggesting a phenotype with reduced activities. We had expected to identify C1q genes in the R2 cluster AMs, but their gene expression was below the detection limit in the scRNA-seq analysis, due to the nature of scRNA-seq with reduced detection sensitivity compared to bulk RNAseq. The heterogeneity of AMs was confirmed by scRNA-seq at the mRNA level, as the CXCL2-GFP reporter system did at the protein level.

This study also brought up new questions to be answered in the future by overcoming technical limitations. A current major technical challenge is to precisely characterize AM phenotypes and identify functions of AMs without ex vivo handling. AMs are sensitive and likely to change their phenotypes once taken out from the lung. Thus, we need to have in vivo fate-mapping systems to answer whether the H1 AMs (loaded with Cxcl2 mRNA) are indeed precursors of CXCL2- AMs, and what is the fate of AMs in vivo without using PMT. Another challenge is to develop in vivo technologies to deplete AMs or genes of interest in an AM-specific fashion. These technologies will further advance our understanding of AMs. In this study, we found that infections by Cn and Af allow heterogeneous AM responses in vivo. We used various unbiased approaches to understand gene expression and chromatin status. The significant question for the next step is to answer why the immune system develops the intricate outcome of the simultaneous appearance of the heterogenous AM subpopulations with pro- and anti-inflammatory profiles. Once the question is answered, we would like then to suggest pharmacological approaches to tip the balance of AM subpopulations as a potential early-stage intervention to treat fungal infections.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We performed analyses of AM subpopulations, which appear immediately after pulmonary fungal infections. Host AM responses by pulmonary instillation with Cn, Af, zymosan, or Pam2CSK4 were assessed by using CXCL2-GFP reporter mice in a majority of experiments. Subjects or other experimental units were assigned randomly except that mice of 6–8 weeks old, age- and sex-matched mice were used for all experiments unless otherwise specified. Conduct of the experiments and assessment of outcomes were performed in a blinded fashion. Descriptions of experimental replicate are found in figure legends and/or sub-sections in Materials and Methods.

Experimental animals and fungal infection

All the mice in this study were on the C57BL/6 background. CXCL2-GFP reporter mice were generated (14) and generously provided by Dr. T. Hohl (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York). Flt3Cre mice (19) were used under MTA with Dr. T. Boehm (Max-Planck Institute of Immunobiology, Freiburg, Germany) after crossing to Rosa26 LSL-tdTomato mice (Jackson Laboratory #007909). C1qa−/− mice (44) were obtained from Dr. D. Fraser (California State University, Long Beach, CA). Card9−/− mice were provided from Dr. Xin Lin (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. All the experiments were performed as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Duke University.

C. neoformans yeasts (H99 strain) were cultured in liquid yeast extract–peptone–dextrose (YPD) medium at 37°C overnight and harvested by washing with PBS twice. Mice were inoculated oro-tracheally with indicated inocula with the range of 104–106 Cn yeasts/mouse in 50 μl of PBS. In some experiment, Cn yeasts were heat-killed for 1 hr at 100 °C prior to inoculation of mice. A. fumigatus (Af) (Af293 strain) spores were cultured on glucose minimal medium (GMM) agar (1% glucose, pH 6.5) for 5 days at 37°C. Af conidia were harvested from the plate by using 10 ml of 0.05% Tween 80 and filtered through Miracloth (Millipore). The filtered conidia were washed twice in sterile distilled water and resuspended in sterile distilled water and counted. Af conidia were instilled into mice (107 conidia/mouse). To evaluate colony forming units (CFU), tissues from infected mice were homogenized in water. After serial dilutions, homogenates were plated on YPD plates. CFU count was performed with plates incubation at 30 °C for 2 days.

Lung cell analysis by flow cytometry analysis and isolation by FACS

Mice were euthanized with CO2. After the opening of mice chest cavity, the lungs were inflated intratracheally with a digestion solution containing 60 μg/ml Liberase TM (Roche) and 6,500 Dornase units/ml DNase I (Roche), 5% FBS, and 10mM HEPES in HBSS buffer, as previously described (15). The inflated lung was then removed from the chest cavity and placed in the same digestion solution for 1hour at 37 °C. After 1 hour of digestion, the lung tissue was gently vortexed to obtain a single-cell suspension. The digested lung cells were then treated with RBC lysis solution, stained with specific antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fortessa X20, BD) (Table S2). To isolate AMs, we used CXCL2-GFP reporter mice intratracheally instilled with C. neoformans 104 yeasts cells/mouse (16-hpi). Single-cell suspensions from the digested lung tissue were first enriched for CD45+ by positive selection using MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec) and were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Astrios sorter, Beckman Coulter) based on GFP expression. As a homeostatic AM control, we used total AM, which are all CXCL2-GFP-negative. The gating strategy for AMs is shown in fig. S1B. The strategy was used for a majority of analyses, including qPCR, RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, scRNA-seq, Seahorse analyses, PMT, and other AM experiments that require cell culture, unless otherwise noted. In some experiments, we analyzed cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), which was obtained by 0.5 ml PBS twice. For microscopic imaging, sorted AM cells were seeded on 16-well chamber slide at 5×104 cells/well and incubate for 48 hours, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde before subjected to imaging.

Precision-cut mouse lung slices (PCLS) and immunostaining

We followed a previous publication (45) to prepare PCLS. Mice were euthanized with CO2, and the chest cavity was opened to intratracheally inflate lung lobes with 2.5% low-melting point agarose. Mice were then kept at 4 C to solidify agarose. Inflated right upper lobe was excised from the mice and sliced with 150 μm thickness with Compresstome® (VF-200–0Z, Precisionary) in ice cold PBS. PCLS were stained with an antibody cocktail for 1 hour at 4 °C with gentle rocking; and, without fixation, microscopic images were immediately acquired with a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss 780 upright) using a 20x objective. Images were constructed with tile scans and z-stacks of images. The antibody panel for AM detection was used as follows: CD11c-PE, CD206-AF647, and CD326/EpCam-eFluor450.

Determining levels of proteins and mRNA

Protein levels of CXCL2 (PromoKine) and C1q complex (Hycult Biotech)in BALF and cell supernatant was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). LegendPlex™ bead-based immunoassays (BioLegend) were to simultaneously detect concentrations of multiple cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-10, by flow cytometry.

mRNA was isolated from AMs using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) to synthesize cDNA with a qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quantabio). Standard quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems) (Table S3). Actb expression was used as an internal control unless otherwise specified. Data analyses were performed with the -ΔΔCt method as described in our previous publication (46).

Seahorse analysis of AMs

OCR and ECAR were measured in FACS-sorted AMs (5×104 AMs per well in Seahorse 96-well plates) 48 hours after plating in complete RPMI medium with XFe96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). As suggested by manufacturer’s instructions (Agilent Technologies), cell energy phenotype tests were performed by adding 1 μM oligomycin and 1 μM FCCP. Mitochondria stress assays were performed by adding 1 μM oligomycin and 1 μM FCCP, and Rotenone/Antimycin A at 0.5 μM each. Cellular ATP production was calculated by subtracting the OCR value after the addition of oligomycin from the basal OCR value. Maximal respiration was calculated using the maximum OCR reached after the addition of FCCP and before the addition of rotenone and antimycin A.

Pulmonary macrophage transfer (PMT)

The PMT procedure was adopted from previous publications (42, 47). Briefly, CD45.2 Csf2rb−/− recipient mice (postnatal 5–14 days) were anesthetized with isoflurane. FACS-sorted CD45.1/CD45.2+ AMs (1 – 2×105 cells/recipient) were administered intranasally to the pups in a volume of <15 μl PBS. Transferred AMs were allowed to colonize in the lung of recipient mice for minimum 6 weeks. In some experiments, AM-transferred recipient mice were Cn-instilled, then CD45.1/CD45.2+ donor AMs were analyzed at 16-hpi.

Bulk RNA-seq sample preparation

AMs were obtained from the lung Cxcl2-Egfp;Flt3Cre;R26LSL-tdTomato mice at 9-hpi with Cn by FACS sorting. Homeostatic AM samples (all CXCL2-GFP-negative) were obtained from naïve mice. Total RNA was extracted from cells with RNeasy micro Kit (Qiagen). The initial RNA amplification was carried out with Clontech Ultra Low Input RNA SMARTer mRNA amplification kit (Takara Bio USA). cDNA was used to generate a sequencing library (Kapa Hyper Prep Kit) by Duke Sequencing and Genomic Technologies Shared Resource facility. Sequencing was performed with an Illumina HiSeq4000 using a 50-bp single read. Method for data analysis is described in Supplemental Methods.

ATAC-seq sample preparation

CXCL2-GFP reporter mice were used to prepare five groups of samples: homeostatic AMs, CXCL2- AMs (9- or 24-hpi) and CXCL2+ AMs (9- or 24-hpi). CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs were obtained at 9- or 24-hpi with Cn (104 yeasts/mouse) instillation by FACS. We pooled AMs from three mice per group. Omni-ATAC was performed on 50,000 cells from two biological replicates per AM subpopulation using Tn5 transposase from the Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit (FC-121–1030). Following transposition, the Qiagen MinElute Kit (28204) was used to purify the DNA. Based on qPCR amplification curves, samples were amplified for four additional cycles after the five-cycle preamplification (9 total cycles). For size selection and clean-up of amplified library, three rounds of AMPure beads-enabled purification were performed. 1X AMPure beads were used first to remove primer dimers, followed by 0.5X to remove large fragments >1,000 kb, and finally 1.8X to further clean up. ATAC libraries were submitted to the Duke Sequencing and Genomic Technologies Shared Resource facility for sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq500 using a 42-bp paired-end mode at a depth of 30–50 million reads per sample. Method for data analysis is described in Supplemental Methods.

scRNA-seq sample processing

We used CD45+ lung cells from mice with Cn instillation at 9-hpi, in addition to naïve mice. Samples from three mice were pooled for each group. CD45+ cells were enriched by positive selection by using a combination of using biotinylated CD45 antibody and Streptavidin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Single-cell suspensions were loaded on the 10x Genomics system, and mRNA was converted to single-cell cDNA library, which were sequenced on Novaseq 6000 S-Prime flowcell 150-bp paired end flowcell. Libraries were sequenced in single index mode with the following read lengths: 28×8×91. scRNA-seq data analysis, detailed library preparation and scRNA-seq statistical methods are described in Supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, sample sizes and sample setup conditions were described in each figure legend and genomics analysis method. Error bars show SEM centered on the mean unless otherwise indicated. Other than genomics data, the rest of data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 8). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Supplementary Material

Data File S1. Raw data file (xls document)

Data File S2. Differentially expressed genes in single-cell RNA-seq (xls document)

fig. S1. CXCL2-GFP reporter system used to identify CXCL2-expressing cells by flow cytometry

fig. S2. Involvement of CARD9 in CXCL2 expression by AMs upon C. neoformans in vivo stimulation.

fig. S3. Similar distribution of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs in the lung

fig. S4. Ontogenic fate-mapping with Flt3 in AM subpopulations

fig. S5. Assessing impacts of age and sex of mice on ratio between CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs

fig. S6. Characterization of gene expression in CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs

fig. S7. Comparison of metabolic profiles and phagocytosis between CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs

fig. S8. Annotating scRNA-seq data

fig. S9. Gene expression analyses using scRNA-seq data

fig. S10. Some AMs are pre-loaded with Cxcl2 mRNA

fig. S11. Combined analysis of RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data

fig. S12. Assessment of C1q deficient mice in Cn infection

fig. S13. Apoptosis and survival of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs

fig. S14. Donor AM subpopulations reconstituted from recipient mice through pulmonary macrophage transfer (PMT)

Table S1. Curated M1 and M2 signature gene set

Table S2. Antibodies used for flow cytometry

Table S3. Primer sequence for qPCR

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Simon Gregory and the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute Molecular Genomics core for performing and generation of scRNA-seq data. We would like to thank Dr. Tobias Hohl for providing the CXCL2-GFP reporter mice, Dr. Kory Lavine (Washington University) for Flt3Cre mice, Dr. Deborah Fraser for C1qa−/− mice, and Dr. Xin Lin (University of Texas) for Card9−/− mice. Environmental Health Scholar Program award to SXV, and Elion Award and the Gertrude B. Elion Mentored Medical Student Research Award of Triangle Community Foundation to MED.

Funding: NIH R01-AI088100 and R21-AI135999 to MLS. NIH R01-GM115474 to MC. F30-AI140497 and T32-GM007171 to MED.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

Data for RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and scRNA-seq is available in NIH Gene Expression Omnibus repository (GSE146235).

References and Notes

- 1.Xu S, Shinohara ML, Tissue-Resident Macrophages in Fungal Infections. Front Immunol 8, 1798 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussell T, Bell TJ, Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nature reviews. Immunology 14, 81–93 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fels AO, Cohn ZA, The alveolar macrophage. J Appl Physiol (1985) 60, 353–369 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour MK, Levitz SM, Interactions of fungi with phagocytes. Curr Opin Microbiol 5, 359–365 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kechichian TB, Shea J, Del Poeta M, Depletion of alveolar macrophages decreases the dissemination of a glucosylceramide-deficient mutant of Cryptococcus neoformans in immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun 75, 4792–4798 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osterholzer JJ, Milam JE, Chen GH, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA, Role of dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages in regulating early host defense against pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infection and immunity 77, 3749–3758 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuiston TJ, Williamson PR, Paradoxical roles of alveolar macrophages in the host response to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Infect Chemother 18, 1–9 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC, Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Science translational medicine 4, 165rv113 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guillot L, Carroll SF, Homer R, Qureshi ST, Enhanced innate immune responsiveness to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection is associated with resistance to progressive infection. Infection and immunity 76, 4745–4756 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozel TR, Gotschlich EC, The capsule of cryptococcus neoformans passively inhibits phagocytosis of the yeast by macrophages. Journal of immunology 129, 1675–1680 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syme RM, Bruno TF, Kozel TR, Mody CH, The capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans reduces T-lymphocyte proliferation by reducing phagocytosis, which can be restored with anticapsular antibody. Infection and immunity 67, 4620–4627 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis MJ, Tsang TM, Qiu Y, Dayrit JK, Freij JB, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA, Macrophage M1/M2 polarization dynamically adapts to changes in cytokine microenvironments in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. MBio 4, e00264–00213 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ost KS, Esher SK, Leopold Wager CM, Walker L, Wagener J, Munro C, Wormley FL Jr., Alspaugh JA, Rim Pathway-Mediated Alterations in the Fungal Cell Wall Influence Immune Recognition and Inflammation. mBio 8, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhingran A, Kasahara S, Shepardson KM, Junecko BA, Heung LJ, Kumasaka DK, Knoblaugh SE, Lin X, Kazmierczak BI, Reinhart TA, Cramer RA, Hohl TM, Compartment-specific and sequential role of MyD88 and CARD9 in chemokine induction and innate defense during respiratory fungal infection. PLoS pathogens 11, e1004589 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu YR, O’Koren EG, Hotten DF, Kan MJ, Kopin D, Nelson ER, Que L, Gunn MD, A Protocol for the Comprehensive Flow Cytometric Analysis of Immune Cells in Normal and Inflamed Murine Non-Lymphoid Tissues. PloS one 11, e0150606 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross O, Gewies A, Finger K, Schafer M, Sparwasser T, Peschel C, Forster I, Ruland J, Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature 442, 651–656 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L, Garner H, Trouillet C, de Bruijn MF, Geissmann F, Rodewald H-R, Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature 518, 547–551 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoeffel G, Chen J, Lavin Y, Low D, Almeida FF, See P, Beaudin AE, Lum J, Low I, Forsberg EC, Poidinger M, Zolezzi F, Larbi A, Ng LG, Chan JK, Greter M, Becher B, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M, Ginhoux F, C-Myb(+) erythro-myeloid progenitor-derived fetal monocytes give rise to adult tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity 42, 665–678 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Beaudin AE, Sojka DK, Carrero JA, Calderon B, Brija T, Gautier EL, Ivanov S, Satpathy AT, Schilling JD, Schwendener R, Sergin I, Razani B, Forsberg EC, Yokoyama WM, Unanue ER, Colonna M, Randolph GJ, Mann DL, Embryonic and Adult-Derived Resident Cardiac Macrophages Are Maintained through Distinct Mechanisms at Steady State and during Inflammation. Immunity 40, 91–104 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, See P, Price J, Lucas D, Greter M, Mortha A, Boyer SW, Forsberg EC, Tanaka M, van Rooijen N, Garcia-Sastre A, Stanley ER, Ginhoux F, Frenette PS, Merad M, Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity 38, 792–804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah D, Romero F, Zhu Y, Duong M, Sun J, Walsh K, Summer R, C1q Deficiency Promotes Pulmonary Vascular Inflammation and Enhances the Susceptibility of the Lung Endothelium to Injury. The Journal of biological chemistry 290, 29642–29651 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spivia W, Magno PS, Le P, Fraser DA, Complement protein C1q promotes macrophage anti-inflammatory M2-like polarization during the clearance of atherogenic lipoproteins. Inflamm Res 63, 885–893 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao S, Liu J, Song L, Ma X, The protooncogene c-Maf is an essential transcription factor for IL-10 gene expression in macrophages. Journal of immunology 174, 3484–3492 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran MTN, Hamada M, Jeon H, Shiraishi R, Asano K, Hattori M, Nakamura M, Imamura Y, Tsunakawa Y, Fujii R, Usui T, Kulathunga K, Andrea CS, Koshida R, Kamei R, Matsunaga Y, Kobayashi M, Oishi H, Kudo T, Takahashi S, MafB is a critical regulator of complement component C1q. Nat Commun 8, 1700 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM, M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Journal of immunology 164, 6166–6173 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jablonski KA, Amici SA, Webb LM, Ruiz-Rosado Jde D, Popovich PG, Partida-Sanchez S, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PloS one 10, e0145342 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stempin CC, Dulgerian LR, Garrido VV, Cerban FM, Arginase in parasitic infections: macrophage activation, immunosuppression, and intracellular signals. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010, 683485 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer-Morales K, Heer CD, Mapuskar KA, Domann FE, SOD2 targeted gene editing by CRISPR/Cas9 yields Human cells devoid of MnSOD. Free Radic Biol Med 89, 379–386 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly CJ, Hussien K, Fokas E, Kannan P, Shipley RJ, Ashton TM, Stratford M, Pearson N, Muschel RJ, Regulation of O2 consumption by the PI3K and mTOR pathways contributes to tumor hypoxia. Radiother Oncol 111, 72–80 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serbulea V, Upchurch CM, Schappe MS, Voigt P, DeWeese DE, Desai BN, Meher AK, Leitinger N, Macrophage phenotype and bioenergetics are controlled by oxidized phospholipids identified in lean and obese adipose tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E6254–E6263 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR, Wagner RA, Greaves DR, Murray PJ, Chawla A, Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab 4, 13–24 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O’Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY, O’Neill CM, Yan C, Du H, Abumrad NA, Urban JF Jr., Artyomov MN, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ, Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol 15, 846–855 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker AD, Malur A, Barna BP, Ghosh S, Kavuru MS, Malur AG, Thomassen MJ, Targeted PPAR{gamma} deficiency in alveolar macrophages disrupts surfactant catabolism. J Lipid Res 51, 1325–1331 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai B, Thorp EB, Doran AC, Subramanian M, Sansbury BE, Lin CS, Spite M, Fredman G, Tabas I, MerTK cleavage limits proresolving mediator biosynthesis and exacerbates tissue inflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, 6526–6531 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YJ, Han JY, Byun J, Park HJ, Park EM, Chong YH, Cho MS, Kang JL, Inhibiting Mer receptor tyrosine kinase suppresses STAT1, SOCS1/3, and NF-kappaB activation and enhances inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. J Leukoc Biol 91, 921–932 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habibian JS, Jefic M, Bagchi RA, Lane RH, McKnight RA, McKinsey TA, Morrison RF, Ferguson BS, DUSP5 functions as a feedback regulator of TNFalpha-induced ERK1/2 dephosphorylation and inflammatory gene expression in adipocytes. Sci Rep 7, 12879 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott CL, T’Jonck W, Martens L, Todorov H, Sichien D, Soen B, Bonnardel J, De Prijck S, Vandamme N, Cannoodt R, Saelens W, Vanneste B, Toussaint W, De Bleser P, Takahashi N, Vandenabeele P, Henri S, Pridans C, Hume DA, Lambrecht BN, De Baetselier P, Milling SWF, Van Ginderachter JA, Malissen B, Berx G, Beschin A, Saeys Y, Guilliams M, The Transcription Factor ZEB2 Is Required to Maintain the Tissue-Specific Identities of Macrophages. Immunity 49, 312–325 e315 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim DS, Han JH, Kwon HJ, NF-kappaB and c-Jun-dependent regulation of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 gene expression in response to lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 cells. Mol Immunol 40, 633–643 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G, Tan CS, Teh BK, Lu J, Molecular mechanisms for synchronized transcription of three complement C1q subunit genes in dendritic cells and macrophages. The Journal of biological chemistry 286, 34941–34950 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahl R, Ramirez-Bergeron DL, Rao S, Simon MC, Spi-B can functionally replace PU.1 in myeloid but not lymphoid development. EMBO J 21, 2220–2230 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solomon LA, Li SK, Piskorz J, Xu LS, DeKoter RP, Genome-wide comparison of PU.1 and Spi-B binding sites in a mouse B lymphoma cell line. BMC Genomics 16, 76 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki T, Arumugam P, Sakagami T, Lachmann N, Chalk C, Sallese A, Abe S, Trapnell C, Carey B, Moritz T, Malik P, Lutzko C, Wood RE, Trapnell BC, Pulmonary macrophage transplantation therapy. Nature 514, 450–454 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bode K, Bujupi F, Link C, Hein T, Zimmermann S, Peiris D, Jaquet V, Lepenies B, Weyd H, Krammer PH, Dectin-1 Binding to Annexins on Apoptotic Cells Induces Peripheral Immune Tolerance via NADPH Oxidase-2. Cell Rep 29, 4435–4446 e4439 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Botto M, Dell’Agnola C, Bygrave AE, Thompson EM, Cook HT, Petry F, Loos M, Pandolfi PP, Walport MJ, Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nature genetics 19, 56–59 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyons-Cohen MR, Thomas SY, Cook DN, Nakano H, Precision-cut Mouse Lung Slices to Visualize Live Pulmonary Dendritic Cells. J Vis Exp, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanayama M, Inoue M, Danzaki K, Hammer G, He Y.-w., Shinohara ML, Autophagy enhances NFkB activity in specific tissue macrophages by sequestering A20 to boost antifungal immunity. Nature Communications 6, 1–14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van de Laar L, Saelens W, De Prijck S, Martens L, Scott CL, Van Isterdael G, Hoffmann E, Beyaert R, Saeys Y, Lambrecht BN, Guilliams M, Yolk Sac Macrophages, Fetal Liver, and Adult Monocytes Can Colonize an Empty Niche and Develop into Functional Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Immunity 44, 755–768 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR, STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W, featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK, edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huber W, Carey VJ, Gentleman R, Anders S, Carlson M, Carvalho BS, Bravo HC, Davis S, Gatto L, Girke T, Gottardo R, Hahne F, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA, Lawrence M, Love MI, MacDonald J, Obenchain V, Oles AK, Pages H, Reyes A, Shannon P, Smyth GK, Tenenbaum D, Waldron L, Morgan M, Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat Methods 12, 115–121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Charrad M, Ghazzali N, Boiteau V, Niknafs A, NbClust: An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. 2014 61, 36 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP, Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P, The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 1, 417–425 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amemiya HM, Kundaje A, Boyle AP, The ENCODE Blacklist: Identification of Problematic Regions of the Genome. Sci Rep 9, 9354 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quinlan AR, BEDTools: The Swiss-Army Tool for Genome Feature Analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 47, 11 12 11–34 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boley N, Kundaje A, Bickel PJ, Lee J, “Irreproducible Discovery Rate,” (2014) https://github.com/kundajelab/idr

- 60.Li Q, Brown JB, Huang H, Bickel PJ, Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Ann. Appl. Stat. 5, 1752–1779 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM 3rd, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, Satija R, Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 177, 1888–1902 e1821 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hafemeister C, Satija R, Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. bioRxiv, 576827 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V, Hsu A, Chak S, Naikawadi RP, Wolters PJ, Abate AR, Butte AJ, Bhattacharya M, Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nature immunology 20, 163–172 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK, limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic acids research 43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sergushichev AA, An algorithm for fast preranked gene set enrichment analysis using cumulative statistic calculation. bioRxiv, 060012 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data File S1. Raw data file (xls document)

Data File S2. Differentially expressed genes in single-cell RNA-seq (xls document)

fig. S1. CXCL2-GFP reporter system used to identify CXCL2-expressing cells by flow cytometry

fig. S2. Involvement of CARD9 in CXCL2 expression by AMs upon C. neoformans in vivo stimulation.

fig. S3. Similar distribution of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs in the lung

fig. S4. Ontogenic fate-mapping with Flt3 in AM subpopulations

fig. S5. Assessing impacts of age and sex of mice on ratio between CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs

fig. S6. Characterization of gene expression in CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs

fig. S7. Comparison of metabolic profiles and phagocytosis between CXCL2+ and CXCL2- AMs

fig. S8. Annotating scRNA-seq data

fig. S9. Gene expression analyses using scRNA-seq data

fig. S10. Some AMs are pre-loaded with Cxcl2 mRNA

fig. S11. Combined analysis of RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data

fig. S12. Assessment of C1q deficient mice in Cn infection

fig. S13. Apoptosis and survival of CXCL2- and CXCL2+ AMs

fig. S14. Donor AM subpopulations reconstituted from recipient mice through pulmonary macrophage transfer (PMT)

Table S1. Curated M1 and M2 signature gene set

Table S2. Antibodies used for flow cytometry

Table S3. Primer sequence for qPCR

Data Availability Statement

Data for RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and scRNA-seq is available in NIH Gene Expression Omnibus repository (GSE146235).