PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy should be considered in the differential diagnosis of facial sensory disturbances, unilateral or bilateral, especially when blink reflex is pathologic. Because bulbar and lower motor neuron dysfunction may appear years after the facial sensory onset, long follow-up is recommended in suspected patients.

Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) is a recently described syndrome, first reported by Vucic et al.1

Clinical features

Usually around the 5th decade of life, patients begin with facial sensory disturbances, such as paresthesia and numbness, which slowly spread to the scalp, neck, upper trunk, and upper limbs in a rostral-caudal progression. Reduced or absent corneal reflex is the main pathognomonic feature. After a variable period, commonly from 2 to 5 years later, patients develop bulbar dysfunction, with dysarthria and dysphagia as main symptoms. Eventually, lower motor neuron signs such as fasciculation, weakness, and atrophy are seen, especially in the upper extremities. FOSMN slowly progresses over the years until death, generally due to respiratory failure.

Electrodiagnostic features

Patients with FOSMN have a decreased or absent blink reflex from the early stages of the disease. As it progresses, electrodiagnostic tests typically show a sensory and motor neuronopathy.2

Pathogenesis and anatomopathologic findings

FOSMN is a neurodegenerative process whose etiopathogenesis remains unknown. Anatomopathologic findings demonstrate atrophy of the cranial nerves' nuclei in the pons and medulla oblongata and gliosis and neuron loss in the dorsal root ganglia of the brainstem and cervical spinal cord, as well as in cervical anterior horns and roots.3

There are only 4 patients with FOSMN whose autopsy findings are reported. Three of them, described by Rossor et al., Ziso et al., and Sonoda et al., have revealed the presence of TAR-DNA binding protein (TDP-43).3–5 The fourth one disclosed no evidence of TDP-43.6 Here, we report a case of FOSMN with postmortem neuropathologic examination showing TDP-43 inclusions, and we compare the clinicopathologic features of previously reported patients (table).

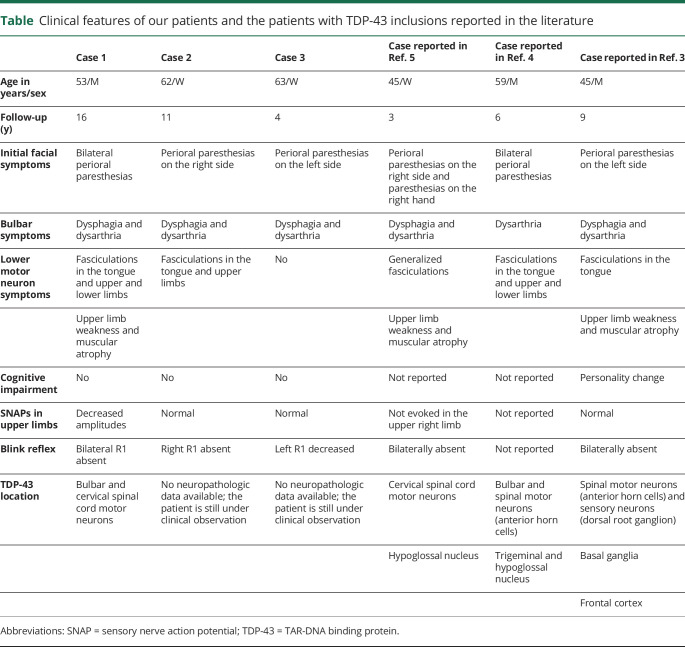

Table.

Clinical features of our patients and the patients with TDP-43 inclusions reported in the literature

Case

A 66-year-old man presented with a 13-year history of perioral paresthesias that over the time increased in intensity and spread bilaterally to both territories of the trigeminal nerve.

At that moment, no clinical or electrophysiologic signs of multiple mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy were present. Brain MRI showed small vessel ischemic disease. Blink reflex showed bilateral absent R1. Extensive etiologic evaluation, including CSF analysis, was unremarkable. One year later, the patient developed paresthesia and numbness in upper limbs. Nerve conduction studies showed decreased sensory nerve action potential amplitudes in the upper extremities, and electromyogram of the 4 limbs was normal. During the follow-up, 15 years after the facial sensory symptoms' onset, the patient developed bilateral facial paralysis, bulbar symptoms (dyspnea, dysarthria, and dysphagia), and proximal and distal weakness of upper extremities. Atrophy and fasciculations were evident in the tongue and both upper and lower limbs. The patient died due to respiratory failure at age 69 years.

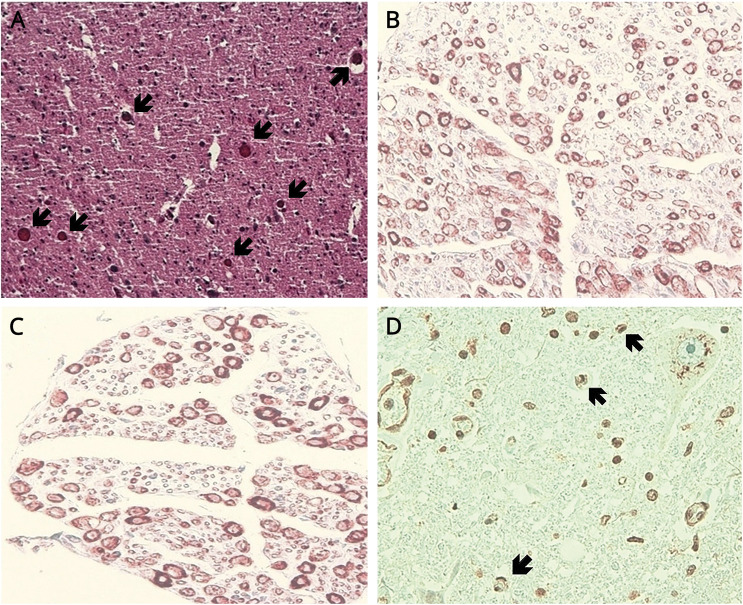

Postmortem pathologic examination (figure) showed atrophy and axonal loss in the anterior horns and in the anterior and posterior roots of the cervical spinal cord. In the brainstem, trigeminal and hypoglossal nuclei were atrophic. Representative sections of the brain and spinal cord were immunostained for TDP-43, observing TDP-43–positive cytoplasmic inclusions in the bulbar and cervical lower motor neurons. Sensory neuronopathy and lower motor neuron disease with TDP-43 inclusions support the diagnosis of FOSMN. FOSMN is suspected in 2 additional patients in our department whose clinical features are described in the table.

Figure. Postmortem neuropathologic findings of our patient.

(A) Trigeminal nucleus with atrophic and reduced neuronal population (arrows). (B) Axonal loss in the posterior roots of the spinal cord. (C) Axonal loss in the anterior roots of the spinal cord. (D) TDP-43–positive cytoplasmic inclusions in the lower motor neurons (arrows), observed by immunohistochemistry. TDP-43 = TAR-DNA binding protein.

Discussion

FOSMN is a rare sensory and motor neuronopathy. The pattern of the sensory and motor abnormalities and the distribution of atrophy and neuronal loss in neuropathologic examinations are well correlated in FOSMN.1 Nevertheless, the presence of TDP-43 inclusions that has been recently reported in a few cases3–5 has brought up new questions related to the underlying mechanisms of the disease. This case we present reinforces the hypothesis that FOSMN is within the spectrum of TDP-43 proteinopathies. In the 4 patients with FOSMN with TDP-43 inclusions reported in the literature (including our case), TDP-43 is observed in the cervical spinal motor neurons invariably3–5 (table). Clinicopathologic findings suggest that it might be a focal form of a slowly progressive motor neuron disease (with associated sensory involvement, without first motor neuron symptoms).6 Whether TDP-43 inclusions in FOSMN may also imply a neurocognitive decline at the end stages of the disease should also be assessed in future research.

Mutations have been detected in the SOD1, TARDBP, and SQSTM1 genes in a few patients with FOSMN.7 Considering the relationship of these genes with motor neuron disease and frontotemporal dementia, it would be highly interesting to perform genetic testing in patients with FOSMN, including TARDBP, FUS, C9ORF72, SOD1, and SQSTM1 genes.

Clinical neurologists should consider FOSMN while evaluating a patient with facial paresthesias and absent or reduced blink reflex. Long-term follow-up may be required to assess the progression of the disease, as well as for early detection of possible cognitive impairment, due to the potential relationship between FOSMN and TDP-43 proteinopathies.3–5

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Fernandez Vega and Dr. Zaldumbide Dueñas (Pathology Department, Cruces University Hospital, Barakaldo, Spain), who confirmed the pathologic diagnosis and contributed to image revision.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Vucic S, Tian D, Chong PST, Cudkowicz ME, Hedley-Whyte ET, Cros D. Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN syndrome): a novel syndrome in neurology. Brain 2006;129:3384–3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Q, Chu L, Tan L, et al. . Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy. Neurol Sci 2016;37:1905–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossor AM, Jaunmunktane Z, Rossor MN, et al. . TDP43 pathology in the brain, spinal cord, and dorsal root ganglia of a patient with FOSMN. Neurology 2019;92:e951–e956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziso B, Williams TL, Walters RJL, et al. . Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy: further evidence for a TDP-43 proteinopathy. Case Rep Neurol 2015;7:95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonoda K, Sasaki K, Tateishi T, et al. . TAR DNA-binding protein 43 pathology in a case clinically diagnosed with facial-onset sensory and motor neuronopathy syndrome: an autopsied case report and a review of the literature. J Neurol Sci 2013;332:148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vucic S. Facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) syndrome: an unusual amyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotype? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vázquez-Costa JF, Pedrola Vidal L, Moreau-Le S, et al. . Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy: a motor neuron disease with an oligogenic origin? Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2019;20:172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]