Abstract

Background:

Stage 1 epithelial-predominant favorable histology Wilms tumors (EFHWT) have long been suspected to have an excellent outcome. This study investigates the clinical and pathologic features of patients with stage 1 EFHWT in order to better evaluate the potential for reduction of chemotherapy and its associated toxicity.

Methods:

All patients registered on the COG AREN03B2 study between 2006 and 2017 with stage 1 EFHWT were identified. EFHWT were defined as tumors with at least 66% epithelial differentiation, regardless of degree of differentiation. Clinical information was abstracted from COG records. Event free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated and compared between groups based on age and therapy.

Results:

The 4-year EFS was 96.2% (95% CI; 92 – 100%) and OS was 100%; EFS and OS did not statistically significantly differ based on age at diagnosis (>48 months vs < 48 months) (p=0.37) or treatment (EE4A vs observation only) (p=0.55). Six events were reported. Three patients developed contralateral tumors and did not otherwise relapse; none of these had nephrogenic rests or a recognized predisposition syndrome. Three patients developed metastatic recurrence; all three had received EE4A as primary therapy following nephrectomy.

Conclusions:

Our findings demonstrate an excellent outcome for Stage 1 EFHWT with >95% EFS and OS. These data support the utility of investigating the treatment of Stage I EFHWT with observation alone following nephrectomy.

Keywords: Nephroblastoma, Wilms Tumor, epithelial predominant

Precis for use in the Table of Contents:

Children with Stage 1 epithelial predominant favorable histology Wilms tumor have excellent event-free and overall survival, regardless of age or treatment regimen. These data support the potential utility of investigating the treatment of Stage I EFHWT with observation alone following nephrectomy.

Introduction

Wilms tumor (WT) is the most common malignant renal neoplasm of childhood. The prognosis of WT is dependent upon multiple variables. Factors currently recognized to influence risk stratification and subsequent therapy in patients undergoing nephrectomy at diagnosis include favorable vs unfavorable (anaplastic) histology, clinical stage, age at diagnosis, and molecular alterations (including loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosomes 1p and 16q, LOH 11p15, gain of 1q). The overall survival rate of patients with FHWT is approximately 90%. Nevertheless, WT therapy comes at a cost; historically, 24% of all WT survivors are affected by severe toxicities, including cardiac or pulmonary toxicities, infertility, or secondary malignancies.1 In recent years, substantial effort has been given to improve risk stratification for assignment of treatment, with a goal to reduce the morbidity of treatment while maintaining overall survival. A particular target of these efforts has been young patients (<24 months) with small (<550g) Stage I FHWT, known as Very Low Risk Wilms Tumors (VLRWT). It was first suggested in 1979 that nephrectomy only may be sufficient for VLRWT, followed by a retrospective analysis of children treated in the first three National Wilms Tumor Study (NWTS) protocols.2–3 This was tested in the first prospective cooperative group evaluation of nephrectomy as the only treatment for VLRWT within NWTS-53–4, followed by validation in the COG AREN0532 protocol.5 Given the somewhat arbitrary definitions of VLRWT, this success suggests there may be opportunities to expand the current definitions to allow more patients to be spared the toxicities associated with chemotherapy. The subject of the current study is stage 1 FHWT of all ages showing epithelial predominant histology (EFHWT).

Evidence supporting the unique nature of stage 1 EFHWT, and suggesting that adjuvant chemotherapy may not be helpful, comes from three different observations. First, approximately 25% of VLRWT show exclusively well-differentiated epithelial histology, and have been referred to as epithelial tubular WT.6 Gene expression analysis has confirmed that this subset is pathologically and clinically unique, and subsequent studies of WT of all types demonstrates that this subset is virtually exclusively confined to the kidney of infants and do not relapse.6–7 Recent studies have shown that this subset of tumors is characterized by mutations of TRIM28.8–9 Second, early studies demonstrated that patients with EFHWT are associated with both lower stage tumors and have better outcomes than other histologic patterns, even at older ages.10 Pathologically, these show a spectrum of histologic features and degrees of differentiation. Lastly, metanephric adenomas (MA) are often difficult to distinguish from epithelial WT11, particularly when they show increased proliferation and/or partial encapsulation. In the past few years, up to 85% of MA have been shown to have BRAFV600E mutations, providing a potentially useful diagnostic marker of MA.12–15 Indeed, BRAFV600E mutations have been identified in some (but not all) lesions in adults with increased proliferation and/or partial encapsulation.12 These findings have supported the classification of such tumors as MA rather than EFHWT.

In the current retrospective study, we evaluate the outcomes of patients enrolled in COGAREN03B2 with Stage 1 EFHWT to assess the feasibility and safety of surveillance only for this subset of patients.

Methods

AREN03B2 is a biology and classification study designed to prospectively bank annotated renal tumor samples and served as a gateway to COG therapeutic studies where applicable. We identified all patients registered between 2006 and 2017 on the AREN03B2 study (regardless of therapy, tumor size, and patient age) with tumors determined by central pathology review to be stage 1 FHWT with epithelial predominance (> 66% epithelial differentiation, regardless of degree of differentiation, confined to the kidney, with no prior biopsy). All tumors were primarily resected, with no neoadjuvant chemotherapy given at the time of initial diagnosis. Consent was provided by all patients or their legally authorized guardians for participation in the AREN03B2 study. This study was approved by the National Cancer Institute Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB) or by local institutional IRBs.

The event free survival (EFS) was defined as the time from study enrollment to disease progression or recurrence, development of tumor in the contralateral kidney, second malignant neoplasm, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. The overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from study enrollment to death from any cause. EFS and OS were censored at the patient’s last contact date. Patient follow-up was current through June 30, 2017. EFS and OS rates were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier16 with confidence intervals estimated by the Peto-Peto method17–18 and were compared between groups using the log-rank test.18

Results

Clinical Features:

177 stage 1 EFHWT patients who underwent nephrectomy were identified. This group of patients was composed of 92 males and 85 females with median age of 17.1 months (range: 4.2–197.9 months). The majority of the patients (123/177, 69.5%) were younger than 48 months at the time of diagnosis (Table 1). 117 patients (66.1%) were treated with vincristine and dactinomycin (EE4A), while 57 patients (32%) were classified as VLRWT (<24 months of age and with nephrectomy weight <550g) and were treated with observation only; 3 patients underwent other treatments (1 also received doxorubicin (DD4A) and 2 received unknown treatments). Approximately 20% of stage 1 FHWT registered on AREN03B2 were epithelial predominant.

Table 1.

Study Patients by Age and Therapy

| Treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Relapse | EE4A | Observation | Other | Unknown | Total |

| <2 | 3 | 44 | 56 | 1 | 1 | 102 |

| 2–4 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| >4 | 3 | 52 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 54 |

| Total | 6 | 117 | 57 | 2 | 1 | 177 |

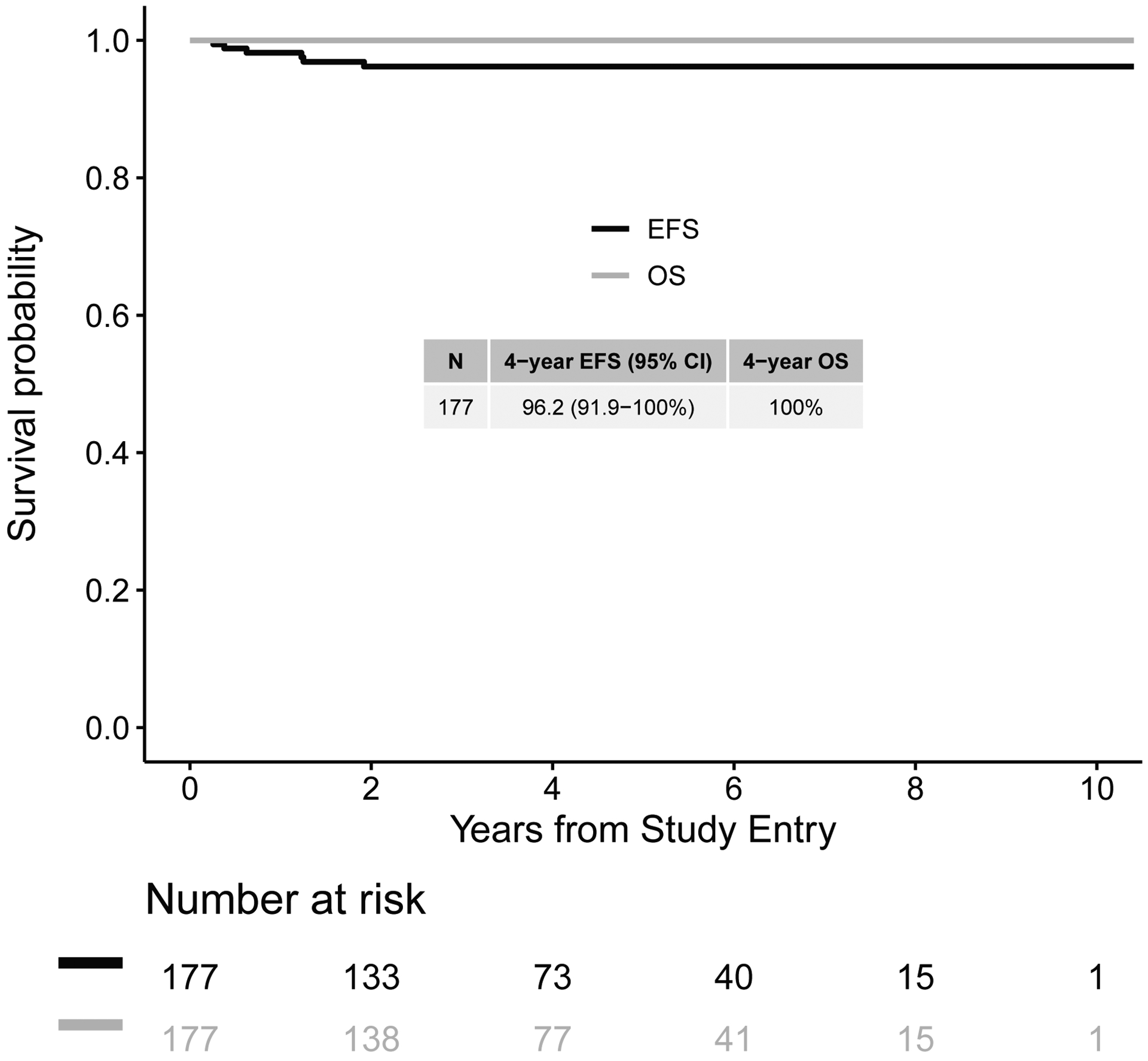

Median follow-up was 3.6 years (range: 1 day-10.4 years) for the 177 patients. The 4-year EFS was 96.2% (95% CI: 92 – 100%) and 4-year OS was 100% (Figure 1). EFS did not differ based on age at diagnosis (older than 48 months: 4-year EFS 93.9%, CI = 84.9% – 100% versus younger than 48 months: 4-year EFS 97.3%, CI = 92.9% – 100%; p=0.37). Similarly, EFS did not significantly differ between patients treated with EE4A versus those treated with observation only (4-year EFS: 96.1% (95% CI 90.8–100%) vs. 98.2% (95% CI 92.8–100%), p=0.55). This similarity of outcome was further confirmed when age at diagnosis and treatment were analyzed together (p=0.84).

Figure 1.

Event-free and overall survival curves for all Stage 1 epithelial predominant favorable histology Wilms tumor (EFHWT) patients

A total of six events were reported in six patients (3.4%). None of the primary tumors in these six patients showed loss of heterozygosity of chromosomes 1p and 16q. No definite nephrogenic rests were identified pathologically in any of the six patients with events, and none had a recognized WT predisposition syndrome. Three of these six patients developed contralateral tumors at 3, 5, and 15 months after initial diagnosis; they did not otherwise relapse and are alive. Two of these three patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (one each DD4A and EE4A) for their initial tumors.

The remaining three patients with an event developed metastatic tumor (abdomen (2), liver (2), lymph nodes (1) and lung (1)), and two of the patients had multiple sites of metastasis. All three patients with metastatic WT received EE4A as primary therapy. The ages (at initial diagnosis) of patients who relapsed were 8, 49, and 193 months; the time to event for these patients were 8, 23, and 15 months, respectively. Two of the three patients who developed metastatic disease did not undergo lymph node sampling at initial diagnosis.

Histologic Features:

Fifty-one (29%) of the 177 patients had epithelial tubular histology typical of those previously identified in VLRWT (Figure 2A). Of these, one developed a contralateral tumor and none metastasized. Fourteen (7.9%) of the 177 tumors displayed histologic features indeterminate between EFHWT and metanephric adenoma, and no events were identified in these patients (Figure 2B). The remaining tumors demonstrated a wide range of epithelial histologic features (Figure 2C), and were at times accompanied by a range of blastemal or stromal features comprising less than 1/3 of the tumor. While a range of non-epithelial histologic subtypes were present in these cases, for all cases epithelial predominance was unequivocal. All metastatic relapses occurred in this group.

Figure 2:

Histologic appearance of different categories of EFHWT (Hematoxylin and Eosin).

A. Tumor classified as EFHWT with exclusively epithelial tubular features.

B. Tumor classified as EFHWT with features of metanephric adenoma.

C. Tumor classified as EFHWT showing poorly differentiated epithelial features with intermixed undifferentiated (blastemal) cells comprising less than 1/3 of the tumor.

D. Relapse tumor histology showing blastemal predominance, taken from a patient with EFHWT at diagnosis who was treated with EE4A

Histologic slides taken at the time of the event (contralateral recurrence or metastasis) were also available for four of the six patients with reported events. One patient initially had a 178g epithelial tubular VLRWT removed at 8 months of age which was followed without chemotherapy; this patient developed another epithelial tubular WT in the contralateral kidney three months later. (Of note, recent studies have reported germline TRIM28 mutations and contralateral tumor development in a minority of patients with epithelial tubular WT.8–9) The contralateral tumors for the other two patients were not available for histologic review. All three patients who developed metastasis had available tumor samples taken at the time of relapse. Two were blastemal predominant at relapse (Figure 2D) and one was epithelial predominant at relapse.

Discussion

It has long been appreciated that the prognosis of malignant tumors is largely the result of their aggressiveness on one hand and their responsiveness to therapy on the other. Epithelial predominant favorable histology Wilms tumors (EFHWT), defined as a Wilms tumor in which the epithelial component comprises greater than two-thirds of the tumor, have previously been suggested to be characterized by a low degree of aggressiveness (a feature manifested by invasiveness, ability to metastasize, and ability to be completed resected) combined with a low degree of responsiveness to therapy.10 This, along with observations from International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) that post-therapy epithelial predominant tumors generally show little response to therapy but still have excellent outcomes in that setting, would suggest that some stage 1 EFHWTs may not benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.19–20 The current study examines the outcome of all Stage 1 EFHWT registered on a cooperative group clinical study in order to evaluate the feasibility of treating these patients without adjuvant chemotherapy through a retrospective review. To summarize, 4-year OS was excellent at 100%, with 4-year EFS of 96.2%. Differences in EFS based on age at diagnosis were not observed in this cohort, in contrast with data recently reported by SIOP21; notably, the SIOP cohort received preoperative chemotherapy while the patients in our study received either no chemotherapy or adjuvant therapy only. Additionally, in this cohort of patients, there were 14 cases (7.9%) that showed histologic features of both metanephric adenoma and EFHWT which made final classification difficult. No events occurred within this patient subgroup, suggesting that both tumor types have similar, excellent outcomes. This provides further support to studies of adult tumors in which such tumors are now classified as MA.12

Only 6 events were identified in 177 stage 1 EFHWT following nephrectomy. Three of these events were the development of tumors in the opposite kidney. The remaining three events were the development of metastatic disease within regional lymph nodes, liver, and/or lung. Importantly, all three metastatic events occurred in children who had received adjuvant chemotherapy at the time of initial diagnosis. It should be noted that two of the three patients who developed metastatic disease did not have lymph nodes sampled at the time of the original nephrectomy. Sampling of regional lymph nodes is an important component in Wilms tumor staging;.22–23 As such, it may be prudent to require lymph node sampling in EFHWT patients who otherwise meet criteria for observation only.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the assignment of patient to treatment with chemotherapy vs observation was not randomized and thus there may be unidentified patient features that influenced treatment choice and clinical outcomes, although we feel this to be unlikely. Second, we do not have molecular characterization of these tumors with respect to TRIM28 or BRAFV600 E mutations which may have shed further light in understanding recurrences. Third, the median follow-up for our cohort (3.6 years) may limit the ability to comment on long-term outcomes in this patient cohort; however, our findings align with previous studies that have suggested that low-stage EFHWT have very good long-term outcomes.10 Additionally, given the very low number of patients who developed recurrent disease, we merely report the characteristics of these patients to provide information that may help direct future studies. Lastly, we relied on institutional recognition and report of predisposition syndromes, so cannot completely exclude this to be the case in contralateral recurrences.

All metastatic recurrences in these EFHWT occurred in children who had received adjuvant chemotherapy. Presumably, all metastatic recurrences were present but not recognized at the time of nephrectomy. This suggests that either those tumors that recurred had a higher risk of metastasis, and/or these tumors may not be as responsive to the therapy routinely provided for FHWT. In summary, this study further supports prior observations that EFHWTs confined to the kidney have very low relapse rates and excellent event free and overall survival. These findings provide further rationale for the investigation of conservative management of these patients with observation only after surgery in a clinical trial setting. Within this setting, it will also be possible to establish the inter-observer correlation between the institutional and central pathology review when reclassifying tumors as epithelial predominant.

Financial Support:

Supported by grants U10CA180886, U10CA180899, U10CA098543, U10CA098413, and U24CA114766 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health to support the Children’s Oncology Group. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00898365

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Termuhlen AM, Tersak JM, Liu Q, et al. Twenty-five year follow-up of childhood Wilms tumor: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011. December 15;57(7):1210–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green DM and Jaffe N. The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of Wilms’ tumor. Cancer. 1979. July;44(1):52–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DM, Breslow NE, Beckwith JB, Takashima J, Kelalis P, D’Angio GJ. Treatment outcomes in patients less than 2 years of age with small, stage I, favorable-histology Wilms’ tumors: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol. 1993. January;11(1):91–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamberger RC, Anderson JR, Breslow NE, et al. Long-term outcomes for infants with very low risk Wilms tumor treated with surgery alone in National Wilms Tumor Study-5. Ann Surg. 2010. March;251(3):555–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez CV, Perlman EJ, Mullen EA, et al. Clinical Outcome and Biological Predictors of Relapse After Nephrectomy Only for Very Low-risk Wilms Tumor: A Report From Children’s Oncology Group AREN0532. Ann Surg. 2017. April;265(4):835–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sredni ST1, Gadd S, Huang CC, et al. Subsets of very low risk Wilms tumor show distinctive gene expression, histologic, and clinical features. Clin Cancer Res. 2009. November 15;15(22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadd S, Huff V, Huang CC, et al. Clinically relevant subsets identified by gene expression patterns support a revised ontogenic model of Wilms tumor: a Children’s Oncology Group Study. Neoplasia. 2012. August;14(8):742–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halliday BJ, Fukuzawa R, Markie DM, et al. Germline mutations and somatic inactivation of TRIM28 in Wilms tumour. PLoS Genet. 2018; 14(6):e1007399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong AE, Gadd S, Huff V, Gerhard DS, Dome JS, Perlman EJ. A unique subset of low-risk Wilms tumors is characterized by loss of function of TRIM28 (KAP1), a gene critical in early renal development: A Children’s Oncology Group study. PLOS One (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckwith JB, Zuppan CE, Browning NG, Moksness J, Breslow NE. Histological analysis of aggressiveness and responsiveness in Wilms’ tumor. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996. November;27(5):422–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pins MR, Jones EC, Martul EV, Kamat BR, Umlas J, Renshaw AA. Metanephric adenoma-like tumors of the kidney: report of 3 malignancies with emphasis on discriminating features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123(5):415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caliò A, Eble JN, Hes O, et al. Distinct clinicopathological features in metanephric adenoma harboring BRAF mutation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):54096–54105. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chami R, Yin M, Marrano P, Teerapakpinyo C, Shuangshoti S, Thorner PS. BRAF mutations in pediatric metanephric tumors. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(8):1153–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choueiri TK, Cheville J, Palescandolo E, et al. BRAF mutations in metanephric adenoma of the kidney. Eur Urol. 2012;62(5):917–922. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein JA, Cajaiba MM, Chi YY, Jennings LJ, Mullen EA, Geller J, Vallance K, Fernandez CV, Dome JS, Perlman EJ. BRAF exon 15 mutations in the evaluation of well-differentiated epithelial nephroblastic neoplasms in children [abstract] Society for Pediatric Pathology Spring Meeting March 2018, Vancouver BC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. J R Statist Soc A 1972; 135: 185–207. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer 1977; 35(1): 1–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhard H, Semler O, Bürger D, et al. Results of the SIOP 93–01/GPOH trial and study for the treatment of patients with unilateral nonmetastatic Wilms Tumor. Klin Padiatr. 2004. May-Jun;216(3):132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verschuur AC, Vujanic GM, Van Tinteren H, Jones KP, de Kraker J, Sandstedt B. Stromal and epithelial predominant Wilms tumours have an excellent outcome: the SIOP 93 01 experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010. August;55(2):233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hol JA, Lopez-Yurda MI, Van Tinteren H, et al. Prognostic significance of age in 5631 patients with Wilms tumour prospectively registered in International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 93–01 and 2001. PLoS One. 2019. August 19;14(8):e0221373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kieran K, Anderson JR, Dome JS, Ehrlich PF, Ritchey ML, Shamberger RC, Perlman EJ, Green DM, Davidoff AM. Lymph node involvement in Wilms tumor: results from National Wilms Tumor Studies 4 and 5. J Pediatr Surg. 2012. April;47(4):700–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhuge Y, Cheung MC, Yang R, Koniaris LG, Neville HL, Sola JE. Improved survival with lymph node sampling in Wilms tumor. J Surg Res. 2011. May 15;167(2):e199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.12.026. Epub 2011 Jan 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]