Abstract

Gut microbial β-glucuronidase (GUS) is a potential therapeutic target to reduce gastrointestinal toxicity caused by irinotecan. In this study, the inhibitory effects of 17 natural cinnamic acid derivatives on Escherichia coli GUS (EcGUS) were characterised. Seven compounds, including caffeic acid ethyl ester (CAEE), had a stronger inhibitory effect (IC50 = 3.2–22.2 µM) on EcGUS than the positive control, D-glucaric acid-1,4-lactone. Inhibition kinetic analysis revealed that CAEE acted as a competitive inhibitor. The results of molecular docking analysis suggested that CAEE bound to the active site of EcGUS through interactions with Asp163, Tyr468, and Glu504. In addition, structure–activity relationship analysis revealed that the presence of a hydrogen atom at R1 and bulky groups at R9 in cinnamic acid derivatives was essential for EcGUS inhibition. These data are useful to design more potent cinnamic acid-type inhibitors of EcGUS.

Keywords: Cinnamic acid derivatives, docking, Escherichia coli, β-glucuronidase, structure–activity relationship

1. Introduction

There is significant crosstalk between the complex microbiota of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the host1,2. The microbiota strongly affects host physiology2, immunity, brain function, and metabolism through microbial genes and gene products3,4.

A study revealed that the gut microbiota is associated with several diseases, including cancer, obesity, and diabetes5. Moreover, some drug-induced toxicity in the GI tract was shown to be due to the reversal of phase II glucuronidation caused by gut bacterial β-glucuronidases (GUS). For instance, the side effect (diarrhoea) of the anti-cancer drug irinotecan (CPT-11), is the result of drug hydrolysis into the toxic form SN-38 by microbial GUS in the GI tract. In addition, carboxylic acid-containing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as indomethacin and diclofenac, may cause small intestinal ulcers and inflammation in the presence of GUS6–9. In this context, drug toxicity is reduced by inhibiting bacterial GUS, and screening for potent inhibitors of Escherichia coli GUS (EcGUS) is highly desirable10.

Natural products have received more attention in recent decades, and a wide range of bioactive compounds are in preclinical and clinical trials for treating different diseases. For instance, the herbal concoctions Hange-shashin-to, Sairei-to, and Shengjiang Xiexin are used to treat diarrhoea and acute gastroenteritis and protect against CPT-11 toxicity11–14. Natural substances derived from edible herbs and fruits, such as prenylflavonoids and flavonoids, also inhibit EcGUS15–17. Moreover, cinnamic acid derivatives (CADs) are widely found in vegetables, fruits, and medicinal plants and have multiple biological activities, such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties18,19. Therefore, these compounds are potential candidates for developing EcGUS inhibitors. To the best of our knowledge, this promising area has been little explored.

This study investigated the inhibitory effects of 17 natural CADs on EcGUS and their structure–activity relationships. In addition, molecular docking studies were performed to predict the molecular determinants of CADs against EcGUS.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucuronide (pNPG), D-glucaric acid-1,4-lactone, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and six commercially available CADs (angoroside C, cistanoside A, jionoside B1, acetylacteoside, isoforsythiaside, and forsythoside H) (Shanghai Standard Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were used. Solutions of D-glucaric acid-1,4-lactone (DSL) and each CAD (10 mM) were prepared in DMSO and stored at 4 °C until use. All chemicals were of analytical grade (purity >98%), and 11 CADs were isolated from Baobab fruits (Adansonia digitata)20.

2.2. Enzyme preparation

Recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) harbouring pET28a-EcGUS was provided by Professor Ru Yan from the University of Macau (Macau, China). EcGUS was prepared according to our previous study with a minor modification21.

2.3. Enzyme inhibition assays

Seventeen CADs were subjected to EcGUS inhibitor screening, and the inhibitory effect was determined by measuring the amount of para-nitrophenyl generated from the hydrolysis of pNPG by EcGUS according to our published method16.

2.4. Inhibition kinetics

IC50 values of CADs against EcGUS were determined in vitro under the following reaction condition: 10 µL pure enzyme (2 µg/mL), 70 µL PBS buffer (pH 7.4), 10 µL of each test compound (0.001–100 µM), and 10 µL pNPG (250 µM) at 37 °C for 30 min.

The inhibitory activity of the selected substances was investigated by exploring the interactions between substrates, inhibitors, and EcGUS. The type of inhibition (competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive, and mixed-type) was determined by kinetic studies using different concentrations of pNPG and inhibitors according to the location of the intercept of regression lines on the Lineweaver-Burk plot16,22,23. Inhibition constant (Ki) values were calculated as previously described16.

2.5. Molecular docking

Molecular docking simulations were performed to predict the molecular interactions of inhibitors with EcGUS according to our previous study16. The X-ray crystal structure of EcGUS (PDB ID: 3K4D) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank, and each inhibitor was docked into the active site (pocket 1) of EcGUS using the triangular matching algorithm. Twenty conformations of each ligand-protein complex were created according to the docking scores24.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated twice. Data were calculated as mean ± standard deviation. IC50 values were defined as the inhibitor concentration necessary to cause 50% inhibition and were evaluated by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Screening for potent EcGUS inhibitors

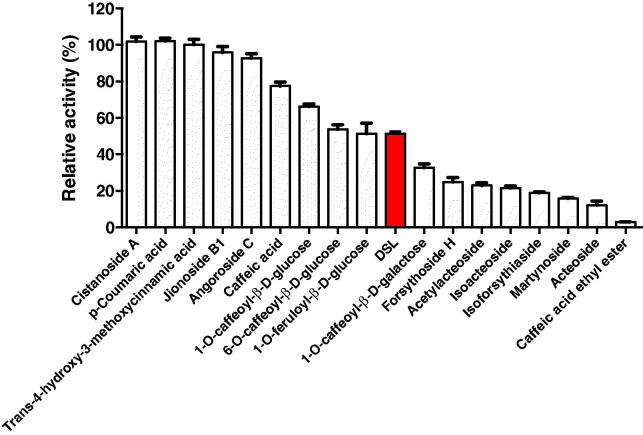

The inhibitory effects of 17 natural CADs on EcGUS were assessed using pNPG as a substrate. Eight compounds had a stronger inhibitory effect than DSL (positive control) (Figure 1). The substances with the highest inhibitory action were caffeic acid ethyl ester (CAEE) (97.1 ± 0.2%) and acteoside (88.0 ± 2.2%) (Table 1). In addition, compared with DSL (48.7 ± 1.2%), the percentage inhibition rates of martynoside, isoforsythiaside, isoacteoside, acetylacteoside, forsythoside H, and 1-O-caffeoyl-β-D-galactose were 84.1%, 78.5%, 77.0%, 75.2%, and 67.2%, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Relative activity of EcGUS in the presence of different compounds at 100 μM. The β-glucuronidase inhibitor DSL (D-glucaric acid-1,4-lactone) was used as a positive control. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate reactions.

Table 1.

Chemical structures of cinnamic acid derivatives and inhibition of EcGUS-mediated pNPG hydrolysis.

|

3.2. The inhibitory effects of CADs on EcGUS

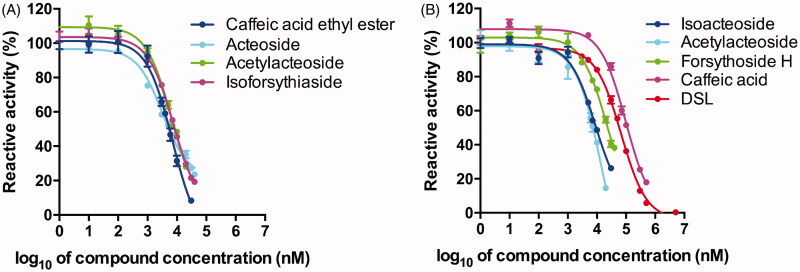

IC50 values of promising EcGUS inhibitors relative to DSL (control) were determined (Figure 2). Seven CADs, including acteoside, acetylacteoside, CAEE, isoforsythiaside, isoacteoside, martynoside, and orsythoside H, had a strong inhibitory effect against EcGUS, with IC50 values of 3.2, 6.6, 7.0, 7.6, 8.8, 14.3, and 22.2 µM, respectively, compared to DSL (IC50 of 67.1 µM).

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent curves of EcGUS inhibitors. (A) Acteoside, acetylacteoside, caffeic acid ethyl ester, and isoforsythiaside; (B) Isoacteoside, martynoside, forsythoside H, caffeic acid, and D-glucaric acid-1,4-lactone. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

3.3. Structure–activity relationships of CADs

According to previous results (Table 1, structure A), the structure–activity relationship of the study compounds can be explained as follows. The inhibitory activity of CADs containing glucosyl and arabinosyl groups was significantly lower than that of other compounds. For instance, martynoside was more active against EcGUS than angoroside C (IC50, 14.3 vs. >100 µM), suggesting that an arabinosyl group at R1 enhanced EcGUS inhibition. Similarly, caffeic acid had a more potent inhibitory effect than its glycoside, 1-O-caffeoyl-β-D-glucose, demonstrating that a glucosyl group at R1 increased EcGUS inhibition. In addition, the inhibitory action of compounds containing a hydrogen atom at position 1, a cinnamic acid moiety at position 2, a rhamnosyl moiety at position 3, and small molecules (e.g., CH3CO, CH3) at position 4 or 5 was comparatively higher. Interestingly, CAEE had a much stronger inhibitory effect than caffeic acid (Table 1, structure B), indicating that the presence of a larger group, except glucosyl and galactosyl groups, in the R9 position of CADs, was essential for EcGUS inhibition.

3.4. Inhibitory behaviour of CADs on EcGUS

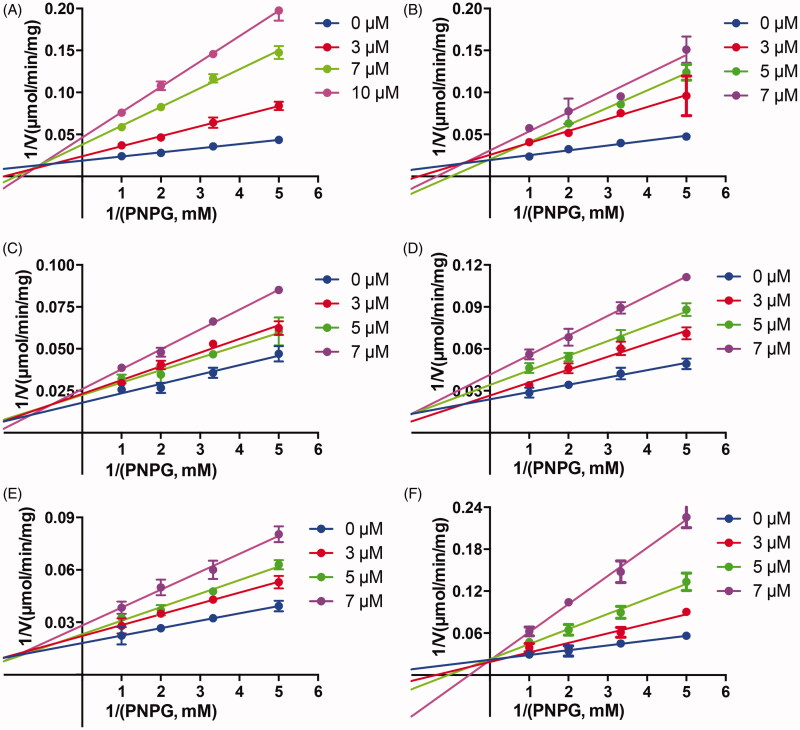

The inhibition action of six CADs against EcGUS was investigated. In Lineweaver-Burk plots, the location of the intercept of regression lines in the second quadrant for acteoside, martynoside, isoacteoside, acetylacteoside, and isoforsythiaside demonstrated that these compounds were mixed-type inhibitors of EcGUS, with Ki values ranging from 2.8 to 8.3 µM (Figure 3(A–E) and Table 1). This result indicates that these molecules bind to the enzyme at both the allosteric site and active site. In addition, the location of the intercept at the y-axis for CAEE demonstrated that this compound was a relatively strong competitive inhibitor, with a Ki value of 2.7 µM, and CAEE and pNPG competed for the same binding site of EcGUS (Figure 3(F) and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Lineweaver-Burk plots of (A) acteoside, (B) martynoside, (C) isoacteoside, (D) acetylacteoside, (E) isoforsythiaside, and (F) caffeic acid ethyl ester as EcGUS inhibitors. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

3.5. Molecular docking simulations

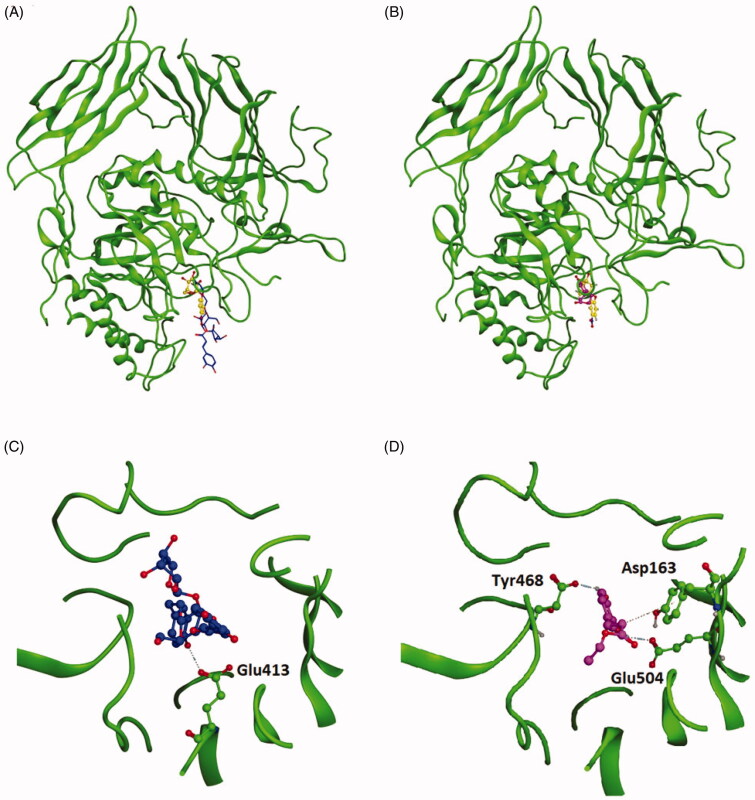

The molecular interactions of CADs with EcGUS (PDB ID: 3K4D) were analysed by molecular docking. pNPG, acteoside, and CAEE fit into the active site (pocket 1) of EcGUS (Figure 4). In contrast, acteoside bound weakly to the active site. Acteoside bound to Glu413, which is located at the entrance of the active site, and this amino acid plays a pivotal role in substrate recognition and inhibitor interaction. In contrast, CAEE mainly interacted with residues Asp163, Tyr468, and Glu504, which were located in the binding area of pNPG; therefore, these two ligands competed for the same active site. The experimental findings agreed with molecular docking results, wherein acteoside was a mixed-type inhibitor, whereas CAEE was a competitive inhibitor of EcGUS.

Figure 4.

Stereoview of the 3D structure of EcGUS and a stereodiagram of pNPG bound to (A) acteoside or (B) caffeic acid ethyl ester in the active site (pocket 1) of EcGUS. Detailed view of (C) acteoside and (D) caffeic acid ethyl ester in the active site of EcGUS.

4. Discussion

Gut bacterial GUS inhibitors are important targets for reducing drug toxicity and intestinal disorders caused by CPT-11 and NSAID treatment9,25, and natural products help regulate the gut microbiota26. In addition, recent studies have shown that CADs are promising for developing EcGUS inhibitors26,27. In this study, the inhibitory effects of 17 natural CADs on EcGUS were determined, and eight substances, including CAEE and acteoside, were more active than D-glucaric acid-1,4-lactone (positive control). The results of molecular docking analysis suggested that acteoside bound to an amino acid residue located at the entrance of the active site of EcGUS, whereas CAEE strongly interacted with Asp163, Tyr468, and Glu504 at the active site.

It has been shown that phytochemicals, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, and phenols, can influence the gut microbiota and improve human health26. For instance, the CAD curcumin modulates the gut microbiota during colitis and colon cancer and improves intestinal barrier function26. In the present study, eight CADs were identified as relatively potent EcGUS inhibitors, which may partially explain their efficacy in alleviating inflammatory diseases.

The results of structure–activity relationship analysis revealed that glucosyl and arabinosyl groups at R1 reduced the inhibitory activity of a CAD (structure A), whereas the presence of bulky groups at R9 increased the inhibitory activity against EcGUS. The presence of a hydrogen atom at R1 also enhanced this activity. These results allow designing and developing more potent small-molecule inhibitors of EcGUS.

EcGUS was frequently observed in mammalian gut and can be easily prepared, therefore, it was widely used for screening GUS inhibitors28–31. However, approximately 45% of the microbial species in the human intestine contain GUS7, and our previous study indicated the need to use a mixture of human gut microbiota for inhibitor screening32. Therefore, further studies are necessary to evaluate the inhibitory effects of the study compounds on other bacterial GUS and their in vivo efficacy in reducing CPT-11-induced toxicity.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that eight CADs were relatively strong EcGUS inhibitors, and the presence of a hydrogen atom at R1 and bulky groups at R9 in CADs was essential for EcGUS inhibition. These data allow designing and developing more potent cinnamic acid-type inhibitors of EcGUS.

Ethical policy and institutional review board statement

This research did not include any human subjects and animal experiments.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Prof. Yan Ru (University of Macau, Macau, China) for providing us the recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) for Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase preparation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81502941].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Ohnuki T, Ejiri M, Kizuka M, et al. Practical one-step glucuronidation via biotransformation. Bioorgan Med Chem Lett 2019; 29:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin AM, Sun EW, Rogers GB, et al. The influence of the gut microbiome on host metabolism through the regulation of gut hormone release. Frontiers Physiol 2019;10:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belkaid Y, Hand TW.. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014;157:121–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers G, Keating D, Young R, et al. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol Psychiatr 2016;21:738–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B-Y, Xu X-Y, Gan R-Y, et al. Targeting gut microbiota for the prevention and management of diabetes mellitus by dietary natural products. Foods 2019;8:440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biernat KA, Pellock SJ, Bhatt AP, et al. Structure, function, and inhibition of drug reactivating human gut microbial β-glucuronidases. Sci Rep 2019;9:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace BD, Wang H, Lane KT, et al. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science 2010;330:831–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LoGuidice A, Wallace BD, Bendel L, et al. Pharmacologic targeting of bacterial β-glucuronidase alleviates nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012;341:447–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saitta KS, Zhang C, Lee KK, et al. Bacterial β-glucuronidase inhibition protects mice against enteropathy induced by indomethacin, ketoprofen or diclofenac: mode of action and pharmacokinetics. Xenobiotica 2014;44:28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little MS, Pellock SJ, Walton WG, et al. Structural basis for the regulation of β-glucuronidase expression by human gut Enterobacteriaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018;115:E152–E161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kase Y, Hayakawa T, Aburada M, et al. Preventive Effects of hange-shashin-to on irinotecan hydrochloridecaused diarrhea and its relevance to the colonic prostaglandin E2 and water absorption in the rat. Jpn J Pharmacol 1997;75:407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang L, Li X, Wan L, et al. Herbal medicines for irinotecan-induced diarrhea. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh T, Igarashi A, Tanno M, et al. Inhibitory effects of baicalein derived from japanese traditional herbal medicine on SN-38 glucuronidation. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2018;21:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan H, Wang X, Wang S, et al. Comparative intestinal bacteria-associated pharmacokinetics of 16 components of Shengjiang Xiexin decoction between normal rats and rats with irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11)-induced gastrointestinal toxicity in vitro using salting-out sample preparation and LC-MS/MS. RSC advances 2017;7:43621–35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun C-P, Yan J-K, Yi J, et al. The study of inhibitory effect of natural flavonoids toward β-glucuronidase and interaction of flavonoids with β-glucuronidase. Int J Biol Macromol 2020;143:349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei B, Yang W, Yan Z-X, et al. Prenylflavonoids sanggenon C and kuwanon G from mulberry (Morus alba L.) as potent broad-spectrum bacterial β-glucuronidase inhibitors: Biological evaluation and molecular docking studies. J Funct Foods 2018;48:210–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weng Z-M, Wang P, Ge G-B, et al. Structure-activity relationships of flavonoids as natural inhibitors against E. coli β-glucuronidase. Food Chem Toxicol 2017;109:975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Z-D, Lau K-M, Xu H-X, et al. Antioxidant activity of phenylethanoid glycosides from Brandisia hancei. J Ethnopharmacol 2000;71:483–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delazar A, Gibbons S, Kumarasamy Y, et al. Antioxidant phenylethanoid glycosides from the rhizomes of Eremostachys glabra (Lamiaceae). Biochem Syst Ecol 2005;33:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Sun J, Shi H, et al. Profiling hydroxycinnamic acid glycosides, iridoid glycosides, and phenylethanoid glycosides in baobab fruit pulp (Adansonia digitata). Food Res Int 2017;99:755–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei B, Wang P-P, Yan Z-X, et al. Characteristics and molecular determinants of a highly selective and efficient glycyrrhizin-hydrolyzing β-glucuronidase from Staphylococcus pasteuri 3I10. Applied Microbiol Biotechnol 2018;102:9193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xin H, Qi X-Y, Wu J-J, et al. Assessment of the inhibition potential of Licochalcone A against human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Food Chem Toxicol 2016;90:112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv X, Wang X-X, Hou J, et al. Comparison of the inhibitory effects of tolcapone and entacapone against human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2016;301:42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan KM, Ambreen N, Taha M, et al. Structure-based design, synthesis and biological evaluation of β-glucuronidase inhibitors. J Comput Aided Mol Design 2014;28:577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta E, Lestingi TM, Mick R, et al. Metabolic fate of irinotecan in humans: correlation of glucuronidation with diarrhea. Cancer Res 1994;54:3723–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrera-Quintanar L, López Roa RI, Quintero-Fabián S, et al. Phytochemicals that influence gut microbiota as prophylactics and for the treatment of obesity and inflammatory diseases. Mediat Inflamm 2018;2018:9734845–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peperidou A, Pontiki E, Hadjipavlou-Litina D, et al. Multifunctional cinnamic acid derivatives. Molecules 2017;22:1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace BD, Roberts AB, Pollet RM, et al. Structure and inhibition of microbiome β-glucuronidases essential to the alleviation of cancer drug toxicity. Chem Biol 2015;22:1238–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taha M, Ismail NH, Imran S, et al. Synthesis of novel benzohydrazone-oxadiazole hybrids as β-glucuronidase inhibitors and molecular modeling studies . Bioorgan Med Chem 2015;23:7394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zawawi N, Taha M, Ahmat N, et al. Novel 2,5-disubtituted-1,3,4-oxadiazoles with benzimidazole backbone: a new class of β-glucuronidase inhibitors and in silico studies. Bioorgan Med Chem 2015;23:3119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salar U, Taha M, Ismail NH, et al. Thiadiazole derivatives as new class of β-glucuronidase inhibitors. Bioorgan Med Chem 2016;24:1909–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang W, Wei B, Yan R.. Amoxapine demonstrates incomplete inhibition of β-glucuronidase activity from human gut microbiota. SLAS Discov: Adv Life Sci R&D 2018;23:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]