ABSTRACT

The present systematic review examined post-migration variables impacting upon mental health outcomes among asylum-seeking and refugee populations in Europe. It focuses on the effects of post-settlement stressors (including length of asylum process and duration of stay, residency status and social integration) and their impact upon post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression. Twenty-two studies were reviewed in this study. Length of asylum process and duration of stay was found to be the most frequently cited factor for mental health difficulties in 9 out of 22 studies. Contrary to expectation, residency or legal status was posited as a marker for other explanatory variables, including loneliness, discrimination and communication or language problems, rather than being an explanatory variable itself. However, in line with previous findings and as hypothesised in this review, there were statistically significant correlations found between family life, family separation and mental health outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Post-migration, systematic review, forced migration, mental health

La presente revisión sistemática examinó las variables posteriores a la migración que afectan los resultados de salud mental entre las poblaciones de refugiados y en búsqueda de asilo en Europa. Ésta se centra principalmente en los efectos de los factores estresantes posteriores al asentamiento (incluyendo la duración del proceso de asilo y la duración de la estadía, el estado de residencia y la integración social) y su impacto sobre el trastorno de estrés postraumático, ansiedad y depresión. Veintidós estudios fueron revisados en este estudio. La duración del proceso de asilo y la duración de la estadía fueron los factores más frecuentemente citados para las dificultades de salud mental en 9 de 22 estudios. Siete estudios reportaron asociaciones significativas entre los factores de riesgo y la salud mental, y éstos fueron moderados por el estado de residencia. Más bien, el efecto del estatus legal estaba más estrechamente ligado a otros factores posteriores a la migración; fue hallado actuando como un marcador de variables adicionales posteriores a la migración, incluyendo la soledad, la discriminación y los problemas de comunicación o idioma. También se encontró que las dificultades relacionadas a la familia estaban asociadas con la duración de la estadía y el estado legal, concurrente con la noción de que otras variables posteriores a la migración son más relevantes para los resultados de salud mental que la residencia y la duración de la estadía.

PALABRAS CLAVE: post-migración, revisión sistemática, migración forzada, salud mental

本系统综述考查了欧洲寻求庇护者和难民人群移民后变量对其心理健康的影响。它主要关注移民后应激源的影响 (包括庇护过程的时长和停留时间, 居住状态和社会融合) 以及它们对创伤后压力障碍, 焦虑和抑郁的影响。本研究综述了22个研究。在22项研究中的9项中, 庇护过程的时长和停留时间被发现是最常被提及的心理健康困难因素。七项研究报告了风险因素与心理健康之间的显著相关, 并且被居住状态调节。相反, 法律地位的影响与其他移民后因素更加复杂地联系在一起。它被发现可以作为其他移民后变量的标志, 包括孤独, 歧视, 沟通或语言问题。家庭相关困难还被发现与停留时间和法律地位有关, 同时还认为其他移民后变量居住和停留时间对心理健康的影响更大。

关键词: 移民后, 系统综述, 被迫移民, 心理健康

In 2018, 70.8 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide (USA for United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2018), including 3.5 million asylum seekers and 25.9 million refugees. The UNHCR reports that two-thirds of all displaced people originate from Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, and Somalia. Studies show that asylum seekers and refugees are particularly vulnerable to traumatic experiences which are threefold in nature: pre-migration, peri-migration, and post-migration (Chen, Hall, Ling, & Renzaho, 2017). Trauma exposure, in this sense, tends to be cumulative. There is a higher prevalence rate of mental health disorders among these groups compared with the general population. This is especially notable in terms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression which are often comorbid in these populations (Fazel, Wheeler, & Danesh, 2005).

While there is ample evidence of a significant association between pre-migration trauma and psychological difficulties, for example the association between torture and PTSD (Ibrahim & Hassan, 2017; Tufan, Alkin, & Bosgelmez, 2013), less is known about the relationship between post-migration factors and mental health problems (Hynie, 2018). Certain psychosocial variables that are specific to the post-migration context (e.g., legal status) have been shown to compound the psychological effects of pre-migration trauma (Silove, Steel, McGorry, & Mohan, 1998). For example, uncertain immigration status has been found to be as strong as predictor of PTSD as pre-migration rape (Chu, Keller, & Rasmussen, 2013). Therefore, resettlement into a ‘safe’ country is not necessarily conducive to improved psychological well-being.

There are several factors that come to prominence following resettlement into a new country for refugees and asylum seekers. These include legal status, the asylum process, family issues, discrimination, socio-religious factors, and unemployment. Longitudinal research shows that limitation on employment is a strong risk factor for depression, particularly among men (Beiser, 2006). This challenge to economic independence results in lower living standards within host countries compared with one’s country of origin (Silove, Sinnerbrink, Field, Manicavasagar, & Steel, 1997).

This review examines the most frequently cited post-migration stressors experienced by both asylum-seeking and refugee populations within Europe and their associations with mental health problems in the context of resettlement into the host environment. The review focuses on European nations as host countries given the large proportion of asylum seekers it they intake each year. Of specific interest are the implications of post-migration stressors on psychological morbidity, with a view to understanding the most effective mechanisms for improving psychosocial well-being among these groups within the post-migration context. Additionally, this paper looks at salient pre-migration traumatic exposure which moderates or predicts post-migration living difficulties in the population. In order to facilitate a substantive review, the Cochrane protocol for systematic reviews was implemented throughout.

1. Method

1.1. Reviewers

In accordance with the Cochrane protocol, this study involved three independent reviewers. Reviewers one (CG) and two (RF) were responsible for screening and selecting all studies, while reviewer three (MS) was recruited as tie-breaker where agreement could not be reached by CG and RF when reviewing conflicts.

1.2. Review question

Which post-migration variables have the most significant effect on the mental health of asylum seekers and refugees in Europe, according to the literature?

1.3. Scoping search

Throughout May 2018, reviewer one conducted preliminary database enquiries using USearch. USearch is a web-based resource available through Ulster University’s online library services and provided by EBSCOhost (Elton B. Stephens Co. host). This was done to determine the approximate number of studies in relation to the review question and the most appropriate databases to include in the main search. Eight significant resources were identified through the scoping search. These were CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, ERIC, Medline, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. These databases were chosen by identifying (1) the most popular databases in relation to the number of applicable studies they produced and (2) databases cited in relevant systematic reviews (Bogic, Njoku, & Priebe, 2015). These were then used for the main search for this review.

1.4. Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search of studies examining the relationship between post-migration psychosocial factors and their impact on mental health outcomes in asylum-seeking and refugee populations in Europe. This search took place on 22 May 2018 using the 8 databases noted above (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, ERIC, Medline, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science). Initial limiters were set to English language studies published between 2000 and 2018. Exclusion criteria were applied later on in the process. This was done to limit the possibility of selection bias and erroneous omission of any relevant papers (Drucker, Fleming, & Chan, 2016). The search terms and search strategy were devised with the assistance of two subject librarians.

Thirty keywords were used to search each database. Keywords were categorised according to three concepts: population, predictors, outcomes. These categories were searched using common synonyms for each concept. Firstly, population was entered as refugee*, ‘asylum seeker*’, immigrant*, migrant*, ‘displaced person*’, ‘displaced people*’. Secondly, predictors were listed as accommodation, housing, ‘direct provision’, employ*, unemploy*, ‘health care’, language*, ‘socio religio*’, communication*, religio*, ‘health care’, residen*, ‘legal status’, ‘social support*’, family. Thirdly, outcomes included ‘psychosocial’, ‘psychosocial vulnerabilit*’, ‘post migration’, ‘post settlement’, resettlement, ‘post flight’, postflight, ‘mental health’, ‘mental ill-health’, ‘mental ill*’.

Spelling variations were used in the search process to ensure all relevant studies were included. Where appropriate, truncation was employed to broaden results. Keywords were combined in a search matrix using Boolean operators. Synonyms for each individual concept were firstly searched together using ‘or’. Concepts were then combined using ‘and’. This resulted in seven search permutations as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search terms for systematic review

| Search 1 | Concept 1 | refugee* OR ‘asylum seeker*’ OR immigrant* OR migrant* OR ‘displaced person*’ OR ‘displaced people*’ |

| Search 2 | Concept 2 | Accommodation OR housing OR ‘direct provision’ OR employ* OR unemploy* OR ‘health care’ OR language* OR ‘socio religio*’ OR communication* OR religio* OR ‘health care’ OR residen* OR ‘legal status’ OR ‘social support*’ OR family |

| Search 3 | Concept 3 | ‘psychosocial’ OR ‘psychosocial vulnerabilit*’ OR ‘post migration’ OR ‘post settlement’ OR resettlement OR ‘post flight’ OR postflight |

| Search 4 | Concept 1 + 2 | refugee* OR ‘asylum seeker*’ OR immigrant* OR migrant* OR ‘displaced person*’ OR ‘displaced people*’ AND Accommodation OR housing OR ‘direct provision’ OR employ* OR unemploy* OR ‘health care’ OR language* OR ‘socio religio*’ OR communication* OR religio* OR ‘health care’ OR residen* OR ‘legal status’ OR ‘social support*’ OR family |

| Search 5 | Concept 1 + 3 | refugee* OR ‘asylum seeker*’ OR immigrant* OR migrant* OR ‘displaced person*’ OR ‘displaced people*’ AND ‘psychosocial’ OR ‘psychosocial vulnerabilit*’ OR ‘post migration’ OR ‘post settlement’ OR resettlement OR ‘post flight’ OR postflight |

| Search 6 | Concept 2 + 3 | Accommodation OR housing OR ‘direct provision’ OR employ* OR unemploy* OR ‘health care’ OR language* OR ‘socio religio*’ OR communication* OR religio* OR ‘health care’ OR residen* OR ‘legal status’ OR ‘social support*’ OR family AND ‘psychosocial’ OR ‘psychosocial vulnerabilit*’ OR ‘post migration’ OR ‘post settlement’ OR resettlement OR ‘post flight’ OR postflight |

| Search 7 | Concept 1 + 2 + 3 | refugee* OR ‘asylum seeker*’ OR immigrant* OR migrant* OR ‘displaced person*’ OR ‘displaced people*’AND Accommodation OR housing OR ‘direct provision’ OR employ* OR unemploy* OR ‘health care’ OR language* OR ‘socio religio*’ OR communication* OR religio* OR ‘health care’ OR residen* OR ‘legal status’ OR ‘social support*’ OR family AND ‘psychosocial’ OR ‘psychosocial vulnerabilit*’ OR ‘post migration’ OR ‘post settlement’ OR resettlement OR ‘post flight’ OR postflight |

Each concept was searched individually and then combined.

1.5. Selection criteria and piloting

Criteria were firstly piloted on 22 May 2018. Twenty studies (Table 2) were randomly and independently selected through Covidence by both reviewers who tested the selection criteria to evaluate their accuracy for identifying appropriate texts. After this process, changes were made in categories 1 and 5, study population and publication type, respectively. In terms of study population, initially ‘displaced persons’ was entered as a single inclusion criterion. This was subsequently changed to ‘externally displaced’ only, also resulting in two additional exclusion criteria. CG and RF determined these to be ‘internally displaced persons’ and ‘all displaced persons owing to natural disaster’. Publication type was updated to include only peer-reviewed studies. Corresponding exclusion criteria were subsequently redistributed as ‘book chapters’, ‘conference papers’, ‘theses’, ‘commentaries’, ‘letters’, and ‘replies’.

Table 2.

Studies included in the literature synthesis

| Study (first author and publication year) | Countries | Population | Study design | Post-migration stress measure | Mental health measure | Methodology | Study quality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bogic (2012) | Germany, Italy and the UK | Refugees | Cross-sectional | Amended version of the 24-item Life Stressor Checklist Revised | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | Mixed | 100 |

| Bruhn (2018) | Denmark | Longitudinal | Interview | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) | Mixed | 90 | |

| Carswell (2011) | The UK | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Demographic and Post-Migration Living Difficulty Questionnaire; Short Form Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6); Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (Duke-UNC FSSQ) |

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) |

Mixed | 85 |

| Droždek (2013) | The Netherlands | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Interview | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) |

Quantitative | 80 |

| Gerritsen (2006) | The Netherlands | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Self-report questionnaire developed for study | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 (HSCL-25); |

Quantitative | 95 |

| Heeren (2014) | Switzerland | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Index calculated specifically for study; items were based on Heckmann and Schnapper’s integration concept; Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale Short Form X1 |

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS); Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) |

Quantitative | 95 |

| Heeren (2012) | Switzerland | Asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Self-report questionnaire developed for study | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Post-traumatic stress diagnosis scale; Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL) |

Mixed | 85 |

| Kivling-Bodén (2002) | Sweden | Refugees | Cross-sectional | Life-in-Exile Questionnaire | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) | Quantitative | 75 |

| Laban (2007) | The Netherlands | Asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref scale (WHOQOL-Bref); Post-Migration Living Problems Checklist (PMLP) |

World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1 | Mixed | 75 |

| Laban (2005a) | The Netherlands | Asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Interview | World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1; | Mixed | 80 |

| Laban (2005b) | The Netherlands | Asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Interview | World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1 | Mixed | 75 |

| Laban (2008) | The Netherlands | Asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Post-Migration Living Problems Checklist (PMLP); World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref scale (WHOQOL-Bref) |

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); World Health Organisation Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1 |

Mixed | 75 |

| Lamkaddem (2015) | The Netherlands | Refugees & asylum seekers | Longitudinal | Checklist created for study | Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL) Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) |

Quantitative | 100 |

| Lecerof (2016) | Sweden | Asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire created for study | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12); | Quantitative | 75 |

| Mölsä (2014) | Finland | Refugees | Cross-sectional | Interview; EuroQoL EQ-5D |

Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI); General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) |

Mixed | 80 |

| Nosè (2018) | Italy | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Unclear | Life Events Checklist (LEC); General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12); Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) |

Mixed | 85 |

| Schick (2016) | Switzerland | Refugees | Cross-sectional | Post-Migration Living Difficulties Checklist (PMLD) | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS); Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL) |

Quantitative | 100 |

| Steel (2017) | Sweden | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | Post-Migration Living Difficulties (PMLD); Cultural Lifestyle Questionnaire |

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); | Mixed | 100 |

| Teodorescu (2012a) | Norway | Refugees | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire developed for study | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR PTSD Module (SCID PTSD); MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0.0 (MINI); Structured Interview for Disorders of Extreme Stress (SIDES); Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25); Impact of Event Scale Revised (IES-R); Life Events Checklist (LEC) |

Mixed | 95 |

| Teodorescu (2012b) | Norway | Refugees | Cross-sectional | World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref scale (WHOQOL-Bref); Questionnaire developed for study |

Life Events Checklist (LEC); Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV- TR PTSD Module (SCID-PTSD); MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0.0 (MINI); Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R); Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Short Form (PTGI-SF); Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) |

Mixed | 90 |

| Tinghög (2017) | Sweden | Refugees | Cross-sectional | Seven single-item questionnaire developed for study | To identify respondents that had been exposed to refugee-related PTEs before arriving to Sweden, two (identical) checklists were developed to cover the premigration and perimigration periods separately; Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25); Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); WHO-5 Well-being Index (WHO-5) |

Quantitative | 95 |

| Toar (2009) | Ireland | Refugees & asylum seekers | Cross-sectional | 18-item checklist developed for study | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25); |

Quantitative | 90 |

After piloting, studies were selected for inclusion based on eight categories of criteria. These studies were required to meet criteria in all categories: (1) either asylum seekers, refugees, or displaced persons (not owing to natural disasters) who were male or female, 18 years and over, had a history of psychological trauma or torture and underwent mental health assessment; (2) post-migration psychosocial factors, either legal, accommodation, education, social, financial, employment, health, informal supports (e.g. family, religious), formal supports (e.g. therapeutic, NGO); (3) publication timeframe 2000–2018; (4) English language; (5) peer-reviewed publications; (6) primary data; (7) outcomes related to post-migration psychosocial stressors and mental health or the dose–response relationship linking pre-migration trauma to post-migration psychosocial vulnerability; (8) qualitative and quantitative.

Category 1 exclusions included studies which focused on the general population or did not specifically address asylum seekers, refugees, or displaced persons who were male or female, 18 years and over, had a history of psychological trauma or torture and underwent mental health assessment. Category 2 excluded psychosocial factors related to pre-migration and peri-migration contexts. Category 3 eliminated all studies that were published prior to 2000. The decision to impose this limit was based on a preliminary review of the literature which indicated that relevant studies were published from 2000 onwards. Category 4 exclusions specified studies that were not published in English. Non-English language texts were omitted because time limitations did not allow for translation. Category 5 was limited to peer-reviewed studies. Book chapters, conference papers, theses, commentaries, letters, and replies were all excluded. Category 6 excluded all data other than primary data. The review team agreed that this would avoid overuse of the same data in multiple reviews. Category 7 excluded any outcomes that did not focus on either post-migration psychosocial factors in relation to refugee and asylum seeker mental health or the dose–response link between pre-existing trauma and post-migration psychosocial vulnerability. Category 8 exclusions included systematic reviews, narrative reviews, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses. This was done to avoid reviewing the same data on multiple occasions. All 9,940 studies identified in search seven, the final search strategy (Table 1) were exported to Covidence, online programme for systematic reviews, launched in 2013 (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd).

1.6. Title and abstract screening

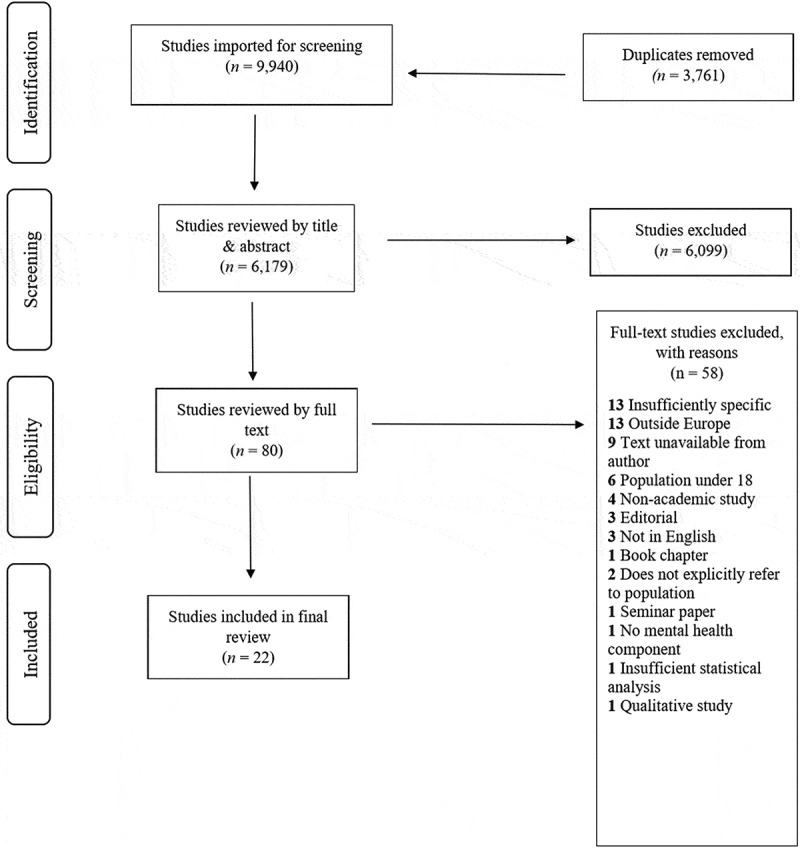

After duplicates were removed, a total of 6179 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Reviewers one and two were required to allocate one vote each per study using the Covidence platform. This was either ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘maybe’ depending on its match with the selection criteria. Once this stage was completed, 6,099 studies were deemed irrelevant based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving a total of 80 papers proceeding to the full-text review.

These were ‘no mental health component’, ‘insufficient statistical analysis’, ‘does not explicitly refer to study population’, ‘insufficiently specific’, ‘text unavailable from author’, ‘not available in English’, ‘qualitative study’, ‘book chapter’, ‘non-academic study’, ‘seminar paper’, ‘editorial’, ‘outside Europe’, and ‘population under 18’.

1.7. Full-text screening and extraction

Reviewers 1 and 2 allocated one vote per study, either ‘include’ or ‘exclude’. There were 13 options for excluding studies after full-text screening (Figure 1). There were two stages involved in data extraction: pilot extraction and final extraction. Firstly, a pilot extraction was conducted by Reviewers 1 and 2. Both independently extracted data from only 10 studies which were randomly chosen from Covidence. For the final extraction phase, each reviewer then independently assessed 50% of the remaining papers, with the option to ‘include’ or ‘exclude’ each text.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) flow-diagram illustrating review process

1.8. Quality assessment

(Shea et al., 2007; Well & Littell, 2016) Study quality was assessed twice during the extraction stage. Firstly, using subjective criteria for inclusion, based on the review protocol. Secondly, using a 19-question assessment schedule, to review the overall quality of each text. Both CG and RF were responsible for the preliminary assessment. CG conducted the final quality review after each of the papers was extracted. Each question was assessed using either ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘somewhat’ or ‘not appropriate’ options. To pass the quality assessment, at least 14 of 19 questions (74%) had to be endorsed with a ‘yes’ vote. All studies passed this assessment.

2. Results

Twenty-two studies were used for the final review and synthesis (Table 2). The total sample for these studies was N = 5,572, with individual studies ranging from n = 26 to n = 1,215. In line with the inclusion criteria, studies were limited to European nations that acted as host countries for refugees and asylum seekers from across the globe. Four studies were conducted in Sweden which included the largest proportion of the overall sample at n = 2,516 (Kivling-Bodén & Sundbom, 2002; Lecerof, Stafström, Westerling, & Östergren, 2016; Tinghög et al., 2017). The Netherlands accounted for n = 1,444 participants across eight studies (Droždek, Kamperman, Tol, Knipscheer, & Kleber, 2013; Gerritsen et al., 2006; Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, & Jong, 2007; Laban et al., 2005a, 2005b; Laban, Komproe, Gernaat, & Jong, 2008; Lamkaddem, Essink-Bot, Devillé, Gerritsen, & Stronks, 2015; Steel, Dunlavy, Harding, & Theorell, 2017). Two studies were conducted in Italy with a sample of n = 406 (Bogic et al., 2012; Nosè et al., 2018). Two further studies in Norway accounted for 70 participants (Teodorescu et al, 2012a, 2012b). Switzerland was home to 392 participants across three studies (Heeren et al., 2012, 2014; Schick et al., 2016) and the UK included 349 participants from the overall sample size drawn from two studies (Bogic et al., 2012; Carswell, Blackburn, & Barker, 2011). Additional studies drew participants from Ireland (n = 88) (Toar, O’Brien, & Fahey, 2009), Finland (n = 128) (Mölsä et al., 2014), Germany (n = 255) (Bogic et al., 2012), and Denmark (n = 34) (Bruhn et al., 2017).

A total of 11 predictors were hypothesised and these were investigated across the twenty-two studies. The following predictors were included insofar as data were reported and explicitly related to mental health outcomes across the studies’ populations.

2.1. Length of asylum process and duration of stay

Nine studies investigated the length of asylum procedure and duration of stay (Heeren et al., 2012, 2014; Laban et al., 2007, 2005a, 2005b, 2008; Mölsä et al., 2014; Nosè et al., 2018; Teodorescu et al., 2012a). A protracted asylum process was one of the most frequently cited stressors to occur during the post-migration period. Using data comparing two pre-stratified groups, those resident for less than 6 months and those resident for greater than 2 years, Laban et al. (2007) reported the length of the asylum procedure to be an important risk factor for psychiatric morbidity (OR = 2.16, CI = 1.15–4.08). Those who were long-stayers (greater than two years) suffered higher rates of psychiatric disorders than those who had been resident for shorter periods of less than 6 months (62% compared to 42%). It was also the strongest predictor for lower overall quality of life, increased disability, and somatic complaints (Laban et al., 2008).

Despite an increase in psychiatric disorders associated with length of stay, an increase in mental health service use was not observed (Laban et al., 2007). Teodorescu et al. (2012a) report four significant inverse correlations between length of stay and current PTSD diagnosis (r = −0.26), depression symptoms (r = −0.27), anxiety symptoms (r = −0.39), general psychological distress (r = −0.35). While Nosè et al. (2018) found length of stay to be a protective factor, where the mean duration was 13 months (Nosè et al., 2018). Contrary to popular research, one study (Heeren et al., 2012) found no correlations between length of stay and mental health outcomes. This finding was duplicated in another later study by Heeren et al. (2014) who reported a significant increased level of anxiety associated with length of stay for refugees only (r = 0.40). Similarly, Mölsä et al. (2014) reported only a marginal positive association between duration of stay and depressive symptoms.

2.2. Residency status

Three studies reported residency status in relation to mental health outcomes with sufficient detail (Heeren et al., 2014; Lamkaddem et al., 2015; Toar et al., 2009). Strong associations were reported between status and mental health risks, but only in instances where other post-migration stressors were present. Asylum seekers were reported to be at greater risk of PTSD (OR = 2.50), depression/anxiety (OR = 3.00) symptoms when compared to refugees (Toar et al., 2009). However, after controlling for other pre- and post-migration stressors and other ongoing conditions, residency was no longer associated with PTSD, depression or anxiety.

Residency status was reported, thus, as a marker for other explanatory variables. Furthermore, Heeren et al. (2014) report unchanged levels of PTSD between those granted status and asylum seekers. PTSD was, thus, purportedly unassociated with residency. In other studies, obtaining residency, or refugee status, was found to improve the overall health of this population (Lamkaddem et al., 2015). But, again, further (mediation) analysis showed that improvements were related to an increase in opportunities, resources and supports available as a consequence of gaining refugee status. That is, factors associated with living outside of the asylum system.

2.3. Family

Four studies related family status to post-migration psychosocial difficulties among these populations (Bruhn et al., 2017; Tinghög et al., 2017; Lamkaddem et al., 2015). With an increase in family/social supports related to status, Lamkaddem et al. (2015) report that family/social support as one of the three main mechanisms through which status operates to improve PTSD, anxiety and depression symptomology. Laban et al. (2006) reported that family-related issues, including missing one’s family, worries about family back home, an inability to go home and loneliness, had one of the highest odds ratios for at least one psychiatric disorder. Participants who had been resident ≥2 years scored significantly higher than newly arrived – less than 6 months. Regarding psychiatric treatment administered in an outpatient setting, family issues were reported as one of the most significant post-migration stressors to interfere with treatment (Bruhn et al., 2017). Additionally, Tinghög et al. (2017) found that stressors related to family life and separation were significantly correlated with mental ill-health. ‘Distressing conflicts in family (family conflicts)’ was reported to be significantly associated with anxiety, depression, low subjective well-being and PTSD. While the same was predominantly true of ‘feeling sad because not reunited with family members (home country and family concerns)’, although this was not significantly associated with anxiety. However, upon conducting a sensitivity analysis, this variable was no longer significantly associated with any mental health outcomes (Tinghög et al., 2017).

2.4. Social integration and weak social network

Three studies looked at the concept of social integration and weak social network in relation to mental health outcomes (Schick et al., 2016; Teodorescu et al., 2012a, 2012b). In one study, bivariate correlation analysis showed that post-traumatic growth has a strong negative associated with poor social integration and weak social network (Teodorescu et al., 2012b). Social network in this instance was measured by the number of good friends that participants had within the host country. In this sample of psychiatric outpatients, the average number of friends reported was 3.0 (range = 0 to 11). Over 25% of the sample had no friends in their reception country. In another study, Teodorescu et al (2012a) also reported weak social integration into the wider host society to be associated only with psychiatric morbidity and higher levels of psychiatric symptomatology. However, weak social integration into one’s ethnic community was associated with current PTSD diagnosis.

Regardless of the duration of stay, one study (Schick et al., 2016), reported that social integration for refugees was notably lacking and did not improve considerably for long-stayers despite participants being resident for over 10 years. This was measured using a version of the Post-Migration Living Difficulties Checklist (PMLDC; Silove et al., 1997; Steel, Silove, Bird, McGorry, & Mohan, 1999) M = 20.7 (SD = 6.1, scale range 0–28). Social integration problems were significantly associated with health-related quality of life and functional impairment (r = −0.47), depressive symptom severity (r = 0.44), PTSD (r = 0.43), and anxiety (r = 0.29). Moreover, in regression analysis, depression and anxiety symptoms were shown to predict difficulties with social integration. Interestingly, integration difficulties were more strongly associated with symptoms of depression and PTSD than frequency of traumatic events.

2.5. Finance

Only two studies offered any significant insight into post-migration financial difficulties in the context of mental health outcomes (Bruhn et al., 2017; Lecerof et al., 2016). Conducting a bivariate analysis, Lecerof et al. (2016) reported financial difficulties to increase the risk of mental health decline (OR = 2.35, 95% CI 1.64–3.38). An analysis of effect modification also showed a positive association between mental health outcomes and low social participation co-occurring with financial difficulties. In a study on post-migration stressors and their impact on mental health treatment, Bruhn et al (2017) found that financial difficulties related to work were the most frequent factor interfering with treatment.

2.6. Employment

Four studies explored employment as a significant post-migratory factor correlated with mental health outcomes (Bogic et al., 2012; Steel et al., 2017; Teodorescu et al., 2012a, 2012b). In a sample of multi-traumatised psychiatric outpatients from a refugee background, unemployment was shown to explain only 1.5% (F (5,45) = 12.62, p <.001) of the variance for psychological health (Teodorescu et al., 2012b). Rendering this variable an insignificant contributor to overall mental health outcomes. Conversely, in a similar sample of multi-traumatised refugees, unemployment was reported to have the most significant correlations with psychiatric illness and symptom severity (Teodorescu et al., 2012a). This was shown to be particularly true in terms of increase in the level of depressive symptoms. In another study, conducted by Bogic et al. (2012), these findings were further endorsed by showing mood disorders (major depression, dysthymia, hypomania, and mania) to be associated with unemployment. Furthermore, Steel et al. (2017) found employment status to be significantly correlated with assimilation into the host environment.

2.7. Housing and accommodation

Along with financial difficulties and discrimination, housing problems were shown to increase the risk of mental ill-health in one study (Lecerof et al., 2016). Lecerof et al. (2016) report an odds ratio of 2.79 (95% CI 1.84–4.22) for poor mental health where participants endured housing issues while age, sex, educational level, social participation and trust in others were controlled for. Together, housing difficulties and low social participation was reported to be the most significant risk factor for poor mental health (Lecerof et al., 2016). Trust in others, conversely, appeared to be a protective factor against declining mental health related to housing difficulties (Lecerof et al., 2016).

2.8. Language proficiency

Across the twenty-two studies, five studies assessed associations between language acquisition/proficiency, social integration and mental health outcomes (Toar et al., 2009; Schick et al., 2016; Mölsä et al., 2014; Tedorescu et al., 2012a; Laban et al., 2006). It was noted that language difficulties appear among the most salient post-migration stressors experienced by asylum seekers (Toar et al., 2009). Interestingly, Laban et al. (2006) also found that regardless of time spent in the host country for asylum seekers, language proficiency did not differ considerably between two pre-stratified groups based on the duration of stay. The mean scores for language problems for those living in the recipient country less than 6 months and greater than 2 years were 55.9 and 51.7, respectively.

Refugees appear to report higher rates of proficiency in terms of ability to communicate in the language native to their host countries. In a sample of traumatised refugees attending outpatient treatment, self-reported medium-high language (host country) proficiency was recorded at 83%. 8.9% scored below this threshold (Teodorescu et al., 2012a). However, this finding was challenged by Schick et al. (2016) who reported less than 20% of refugee participants had sufficient proficiency to answer questionnaires relating to their migration experiences. Indeed, Heeren et al. (2014) found language proficiency to be marginally negatively associated with symptoms of depression (β = −0.20) among older refugees (50–80 years).

2.9. Education

Three studies looked at education as a predictor of mental health outcomes among asylum seekers and refugees (Bogic et al., 2012; Tinghög et al., 2017; Toar et al., 2009). Tinghög et al. (2017) reported similar prevalence rates of PTSD among participants regardless of educational attainment. Years in education ranged from 0 to 9, more than 9 years without a university degree, and more than 12 years with a university degree. However, subjective well-being was reportedly lower among those with a lengthier educational background. Overall mental health remained largely unaffected by educational attainment in this sample. However, Bogic et al. (2012) found education to be independently associated with increased instances of mood and anxiety disorders. Asylum seekers were also found to have had a lower level of education when compared to refugees (Toar et al., 2009).

2.10. Gender

Three studies discussed gender as a predictor of post-migration variables and mental health outcomes (Bogic et al., 2012; Kivling-Bodén & Sundbom, 2002; Mölsä et al., 2014). In a comparative, cross-sectional study (Mölsä et al., 2014) of Somali refugees and their Finnish counterparts, female refugees reported poorer current health and quality of life than male refugees. Kivling-Bodén and Sundbom (2002) reported a greater diagnosis for PTSD at baseline (T1) for males (73.3%) than females (54.5%). However, there was a non-significant difference between males (60%) and females (63.6%) at T2. A partial least squares regression analysis was carried out to ascertain if there were differences in the relationships between post-traumatic symptom severity at T1, age, and the life-situation at T2 and post-traumatic symptom severity at follow-up. For females, they found a significant association where 41.7% of the variance between post-traumatic symptom level at T1, age, and life-situation variables at T2 predicted 94.8% of the variance in the posttraumatic symptom level at T2. Whereas for males, the same analysis indicated that 17.7% of the variance in post-traumatic symptom level at T1 explained 66.9% of the variance in the posttraumatic symptom level at T2. Post-migration variables most strongly associated with decreased levels of post-traumatic symptoms purportedly differed according to genders. Kivling-Bodén and Sundbom (2002) report that social contact, particularly with their own ethnic group, improved symptoms. For males, however, this sentiment did not hold true. In a study by Bogic et al. (2012), increased instances of mood disorders, including major depression, dysthymia, hypomania and mania, were found to be associated with being female.

2.11. Pre-migration trauma as a predictor of post-migration living difficulties

Three studies described in detail the types and frequency of pre-migration trauma in relation to post-migration mental health outcomes (Steel et al., 2017; Teodorescu et al., 2012b; Tinghög et al., 2017). The types of pre-migration traumatic experiences reported were similar across most studies. However, the rank and degree at which these were experienced across the samples differed. Tinghög et al. (2017) reported war (85%) and exposure to potentially life-threatening situations (79%) as the most common pre-migration trauma for their sample. Forced separation from friends and/or family (67.9%) and loss of significant other (64%) also ranked highly. They found 63% of the sample had been witnesses to violence or assault, 33% had been victims of violence or assault, 31% experienced torture, while 7% were survivors of sexual assault. In a study of multi-traumatised psychiatric outpatients with a refugee background, Teodorescu et al (2012b) found severe human suffering was the highest pre-migration trauma for 89.1% of the sample. Additionally, physical assault occurred in 87.3% of cases and 78.2% were subjected to assault with a weapon. However, exposure to war stood at 76.4%. Captivity was the least endorsed, by 56.4% of participants.

Steel et al. (2017) reported the mean number of pre-migration traumatic experiences for their sample to be 9. Frequency of traumatic experiences differed according to gender. Males were found to have experienced more traumatic events (M = 11.00; SD = 8.00). Women, conversely, reported fewer (M = 7.00; SD = 7.00). Material deprivation was ranked highest at 68% of the sample. Sixty-five per cent experienced the death or disappearance of family and 60% experienced confinement. While 54% reported being exposed to situations of war, 38% incurred bodily injury and 21% were forced to inflict harm upon others.

3. Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine and synthesise evidence of post-migration factors affecting mental health outcomes for asylum-seeking and refugee populations across Europe. Twenty-two studies were included in this review.

Length of asylum process and duration of stay was found to be the most frequently cited factor for mental health difficulties in 9 out of 22 studies. This was in line with the review’s hypothesis based on the relevant literature which cites lengthy waiting times for processing applications across Europe. Three studies reported statistically significant associations between residency status and mental health. However, residency status was not independently associated with mental health. Instead, residency was found to be a marker for other explanatory variables and this appears consistent in other studies (Silove et al., 1998). In a study of Tamil asylum seekers, refugees and other immigrants residing in Australia, Silove et al. (1998) reported higher levels of stress among asylum seekers compared with refugees and other migrants.

Family difficulties were also shown to be related to residency and duration of stay (Laban et al., 2006; Lamkaddem et al., 2015). This appears to buttress the claim that other post-migration variables are more relevant to mental health outcomes than residency and duration of stay (Tinghög et al., 2017; Coffeya, Kaplana, Sampson, & Montagna Tucci, 2010; Silove et al., 1997) Silove et al. (1997) found that family separation, and in particular separation from one’s spouse, was significantly associated with anxiety and depression for asylum seekers. Family separation is shown to result in feelings of guilt and powerlessness particularly relating to one’s inability to protect their families from difficulties back home (Tinghög et al., 2017).

Talking to friends and developing a broad social network was reported as a very useful support where family were unavailable (Whittaker, Hardy, Lewis, & Buchan, 2005). With such importance placed on one’s social network, it is unsurprising that post-traumatic stress and depressive symptomology were significantly and positively associated with poor social integration and weak social network or support (Teodorescu et al., 2012b; Gorst-Unsworth & Goldenberg, 1998; Schweitzer, Melville, Steel, & Lacherez, 2006). However, for some, mistrust in others leads to increasing isolation. A lack of trust in others may partially explain why social integration, particularly outside of one’s own ethnic group, was not shown to improve with duration of stay (Schick et al., 2016). Additionally, mistrust of others was shown as a risk factor for declining mental health when related to housing and accommodation issues (Lecerof et al., 2016). Poor social integration and weak social network were also associated with decline of mental health; housing difficulties and low social participation were reported to be the most significant risk factor for poor mental health (Lecerof et al., 2016). Thus, it appears that a lack of social support was a significant predictor of other post-migration difficulties.

Additionally, employment, or the ability to financially support oneself and one’s family, was closely related to personal identity and self-worth, and it was expected that unemployment would have a negative effect on overall health and quality of life (Teodorescu et al., 2012b). Male asylum seekers were reported to endure more financial-related stress than females. This was unsurprising given that males were more likely than females to be unemployed. For males, in particular, employment was seen as a significant marker of achievement.

4. Limitations

Since the search parameters were limited to European host countries alone, there was little discussion by way of non-European practice regarding asylum seekers and refugees. From this point of view, it was difficult to contextualise European law regarding seeking asylum within a global setting. It was especially difficult to accurately account for the role of age on this and other factors considering there was no substantial comparison between older and younger age groups. There appears to be some evidence pointing towards increased acculturative difficulties among older groups, but this finding must be read with caution.

Additionally, the frequent misuse of synonyms purportedly referring to ‘asylum seekers’ and ‘refugees’ such as ‘immigrants’ and ‘migrants’ made it difficult to ascertain in some studies which populations precisely were being referred to. Some studies were excluded on the basis that it was not immediately clear whether terms such as ‘immigrants’ or ‘migrants’ denoted forced or non-forced migrant populations. An overall assessment regarding the quality of the review was made based on the authors’ inability to sufficiently differentiate their subject populations. Given that these are two entirely distinct populations and inclusion of the latter would skew the validity of this review, the reviewers elected to omit these studies. It cannot, therefore, be guaranteed that relevant papers were not overlooked.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

This review examined several post-migration variables impacting upon mental health outcomes among asylum-seeker and refugee populations. It counters existing findings which suggest that mental health decline among these populations is most significantly associated with residency status and length of asylum procedure/duration of stay. Overall, status is thus shown to be an important marker for other explanatory variables. There is mixed evidence about the length of asylum process and duration of stay. Current evidence points towards a significant negative association between these two variables. However, there are conflicting indications claiming that no significant relationship exists. There is sufficient ambiguity in this regard for this association or lack of to be investigated further. Additionally, we know that social integration, weak social network and trust in others appear insidiously problematic across many post-migration variables. This is shown to be especially prevalent among older groups who report increased difficulties with acculturation. There is empirical evidence to suggest that these factors are perhaps more strongly associated with mental health outcomes than any other post-migration variable. Such a finding is useful for devising psychosocial intake risk assessment measures, particularly those focusing on mental health outcomes including PTSD, depression and anxiety.

Funding Statement

This project was conducted as part of the Collaborative Network for Training and Excellence in Psychotraumatology (CONTEXT). CONTEXT has received funding from the European Commission under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement [No. 722523].

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beiser, M. (2006). Longitudinal research to promote effective refugee resettlement. Transcultural Psychiatry, 43(1), 56–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic, M., Ajdukovic, D., Bremner, S., Franciskovic, T., Galeazzi, G. M., Kucukalic, A., … Priebe, S. (2012). Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: Refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn, M., Rees, S., Mohsin, M., Silove, D., & Carlsson, J. (2018). The range and impact of postmigration stressors during treatment of trauma-affected refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(1), 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell, K., Blackburn, P., & Barker, C. (2011). The relationship between trauma, post-migration problems and the psychological well-being of refugees and asylum seekers. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(2), 107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., Hall, B. J., Ling, L., & Renzaho, A. M. (2017). Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: Findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(3), 218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T., Keller, A. S., & Rasmussen, A. (2013). Effects of post-migration factors on PTSD outcomes among immigrant survivors of political violence. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15(5), 890–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffeya, G. J., Kaplana, I., Sampson, R. C., & Montagna Tucci, M. (2010). The meaning and mental health consequences of long-term immigration detention for people seeking asylum. Social Science and Medicine, 70(12), 2070–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, A. M., Fleming, P., & Chan, A. W. (2016). Research techniques made simple: Assessing risk of bias in systematic reviews. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 136(11), 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droždek, B., Kamperman, A. M., Tol, W. A., Knipscheer, J. W., & Kleber, R. J. (2013). Is legal status impacting outcomes of group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder with male asylum seekers and refugees from Iran and Afghanistan? BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, M., Wheeler, J., & Danesh, J. (2005). Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet, 365(9467), 1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, A. A. M., Bramsen, I., Devillé, W., van Willigen, L. H. M., Hovens, J. E., & van der Ploeg, H. M. (2006). Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(1), 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Unsworth, C., & Goldenberg, E. (1998). Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq. Trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 172(1), 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren, M., Mueller, J., Ehlert, U., Schnyder, U., Copiery, N., & Maier, T. (2012). Mental health of asylum seekers: A cross-sectional study of psychiatric disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren, M., Wittmann, L., Ehlert, U., Schnyder, U., Maier, T., & Müller, J. (2014). Psychopathology and resident status: Comparing asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, labor migrants, and residents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(4), 818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynie, M. (2018). Refugee integration: Research and policy. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(3), 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, H., & Hassan, C. Q. (2017). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms resulting from torture and other traumatic events among Syrian Kurdish refugees in Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivling-Bodén, G., & Sundbom, E. (2002). The relationship between post-traumatic symptoms and life in exile in a clinical group of refugees from the former Yugoslavia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105(6), 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban, C. J., Gernaat, H. B. P. E., Komproe, I. H., & Jong, J. T. V. M. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of health service use among Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(10), 837–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban, C. J., Gernaat, H. B. P. E., Komproe, I. H., Schreuders, G. A., & De Jong, J. T. V. M. (2005a). Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in The Netherlands. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 47(11), 743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban, C. J., Gernaat, H. B. P. E., Komproe, I. H., Van Der Tweel, I., & De Jong, J. T. V. M. (2005b). Postmigration living problems and common psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2005, 193(12), 825–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban, C. J., Komproe, I. H., Gernaat, H. B. P. E., & Jong, J. T. V. M. (2008). The impact of a long asylum procedure on quality of life, disability and physical health in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(7), 507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkaddem, M., Essink-Bot, M. L., Devillé, W., Gerritsen, A., & Stronks, K. (2015). Health changes of refugees from Afghanistan, Iran and Somalia: The role of residence status and experienced living difficulties in the resettlement process. European Journal of Public Health, 25(6), 917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecerof, S. S., Stafström, M., Westerling, R., & Östergren, P. O. (2016). Does social capital protect mental health among migrants in Sweden? Health Promotion International, 31(3), 644–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mölsä, M., Punamäki, R. L., Saarni, S. I., Tiilikainen, M., Kuittinen, S., & Honkasalo, M. L. (2014). Mental and somatic health and pre- and post-migration factors among older Somali refugees in Finland. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(4), 499–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosè, M., Turrini, G., Imoli, M., Ballette, F., Ostuzzi, G., Cucchi, F., … Barbui, C. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress and psychiatric disorders in asylum seekers and refugees resettled in an italian catchment area. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(2), 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick, M., Zumwald, A., Knopfli, B., Nickerson, A., Bryant, R. A., Schnyder, U., … Morina, N. (2016). Challenging future, challenging past: The relationship of social integration and psychological impairment in traumatized refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, R., Melville, F., Steel, Z., & Lacherez, P. (2006). Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled sudanese refugees. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(2), 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea, B. J., Grimshaw, J. M., Wells, G. A., Boers, M., Andersson, N., Hamel, C., & Bouter, L. M. (2007). Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol, 7(10). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove, D., Sinnerbrink, I., Field, A., Manicavasagar, V., & Steel, Z. (1997). Anxiety, depression and PTSD in asylum-seekers: Associations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stressors. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170(4), 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove, D., Steel, Z., McGorry, P., & Mohan, P. (1998). Psychiatric symptoms and living difficulties in Tamil asylum seekers: Comparisons with refugees and immigrants. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 97(3), 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, J. L., Dunlavy, A. C., Harding, C. E., & Theorell, T. (2017). The psychological consequences of pre-emigration trauma and post-migration stress in refugees and immigrants from Africa. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(3), 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z., Silove, D., Bird, K., McGorry, P., & Mohan, P. (1999). Pathways from war trauma to posttraumatic stress symptoms among Tamil asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12(3), 421–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, D. S., Heir, T., Hauff, E., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Lien, L. (2012a). Mental health problems and post-migration stress among multi-traumatized refugees attending outpatient clinics upon resettlement to Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2012, 53(4), 316–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, D. S., Siqveland, J., Heir, T., Hauff, E., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Lien, L. (2012b). Posttraumatic growth, depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, post-migration stressors and quality of life in multi-traumatized psychiatric outpatients with a refugee background in Norway. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(1), 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinghög, P., Malm, A., Arwidson, C., Sigvardsdotter, E., Lundin, A., & Saboonchi, F. (2017). Prevalence of mental ill health, traumas and postmigration stress among refugees from Syria resettled in Sweden after 2011: A population based survey. BMJ Open, 7(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toar, M., O’Brien, K. K., & Fahey, T. (2009). Comparison of self-reported health & healthcare utilisation between asylum seekers and refugees: An observational study. Biomed Central Public Health, 9(1), 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufan, A. E., Alkin, M., & Bosgelmez, S. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder among asylum seekers and refugees in Istanbul may be predicted by torture and loss due to violence. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 67(3), 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USA for UNHCR . (2018). Refugee statistics. Retrieved from https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/statistics/

- Veritas Health Innovation . 0000. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org

- Well, K., & Littell, J. H. (2016). Study quality assessment in systematic reviews of research on intervention effects. Social Work and Social Policy, 19(1), 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, S. B., Hardy, G. E., Lewis, K., & Buchan, L. G. (2005). An exploration of psychological well-being with young Somali refugee and asylum-seeker women. Clinical and Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(2), 177–196. [Google Scholar]