Abstract

Direct acting antivirals have dramatically increased the efficacy and tolerability of hepatitis C treatment, but drug resistance has emerged with some of these inhibitors, including non-structural protein 3/4A protease inhibitors (PIs). Although many co-crystal structures of PIs with the NS3/4A protease have been reported, a systematic review of these crystal structures in the context of the rapidly emerging drug resistance especially for early PIs has not been performed. To provide a framework for designing better inhibitors with higher barriers to resistance, we performed a quantitative structural analysis using co-crystal structures and models of HCV NS3/4A protease in complex with natural substrates and inhibitors. By comparing substrate structural motifs and active site interactions with inhibitor recognition, we observed that the selection of drug resistance mutations correlates with how inhibitors deviate from viral substrates in molecular recognition. Based on this observation, we conclude that guiding the design process with native substrate recognition features is likely to lead to more robust small molecule inhibitors with decreased susceptibility to resistance.

Keywords: drug resistance, protease inhibitors, Hepatitis C, NS34/A protease, substrate envelope, structure based drug design, resistance mutations

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which infects 3–4 million people each year (WHO 2014). According to the WHO, approximately 150 million people are infected with HCV chronically, which can cause liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and which is one of the most common reasons for liver transplants and (WHO 2014; Luu 2015). HCV is a genetically heterogeneous RNA virus, with six major genotypes and several subtypes within each genotype with genotype 1 being the most prevalent. Genotypes differ in sequence by approximately 30%, and also differ in cure rates and resistance patterns (Au and Pockros 2014; Jensen et al. 2015). Several direct acting antivirals (DAAs) against HCV have been developed, however, the error-prone RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, combined with high viral replication rate, generates great sequence variation, making HCV a difficult target for designing effective antiviral drugs that retain potency against multiple genotypes and drug resistant variants (Bukh et al. 1995a, 1995b; Au and Pockros 2014).

While DAAs have increased the efficacy and tolerability of HCV treatment, rapidly emerging drug resistance challenged especially the earlier inhibitors, including non-structural protein 3/4A protease inhibitors (NS3/4A PIs) (Pockros 2014). Although these PIs were effective against genotype 1 HCV, some PIs had less activity against other genotypes, especially genotype 3 (Soumana DI, Kurt Yilmaz, Ali, et al. 2016). In addition, first generation PIs, such as telaprevir and boceprevir (now withdrawn (Silverman 2014)), had considerable side effect profiles, drug-drug interactions, and low barriers to resistance (Pockros 2014). Second generation PIs, such as simeprevir, offered more benefits over first generation PIs, such as better side effect profiles and fewer drug-drug interactions, but the barrier to resistance was still low (Au and Pockros 2014; Pockros 2014).

Based on the structural basis of drug resistance in inhibitors of HIV-1 and HCV viral proteases, the key to designing robust inhibitors with high barriers to resistance is to incorporate details of substrate recognition into drug design (King et al. 2004; Nalam et al. 2010; Romano et al. 2010). Inhibitors that mimic native substrate binding features are more likely to retain activity against drug resistant variants because the resistant variants must also retain the ability to cleave viral substrates for survival. Inhibitors that mimic the dynamics of natural substrates are also more likely to maintain potency against drug resistant variants, and in general, additional flexibility at functional groups allows inhibitors to better accommodate drug resistance mutations. To reveal patterns in structure-resistance profiles and develop generally applicable principles for design of better inhibitors with a higher barrier to resistance, we performed quantitative structural analyses of HCV NS3/4A PIs using co-crystal structures and models of the protease in complex with natural substrates and inhibitors. By comparing binding surfaces of native substrates and small molecule inhibitors, we observe that the emergence of drug resistance mutations trends with how inhibitors deviate from native substrate binding features.

HCV NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors

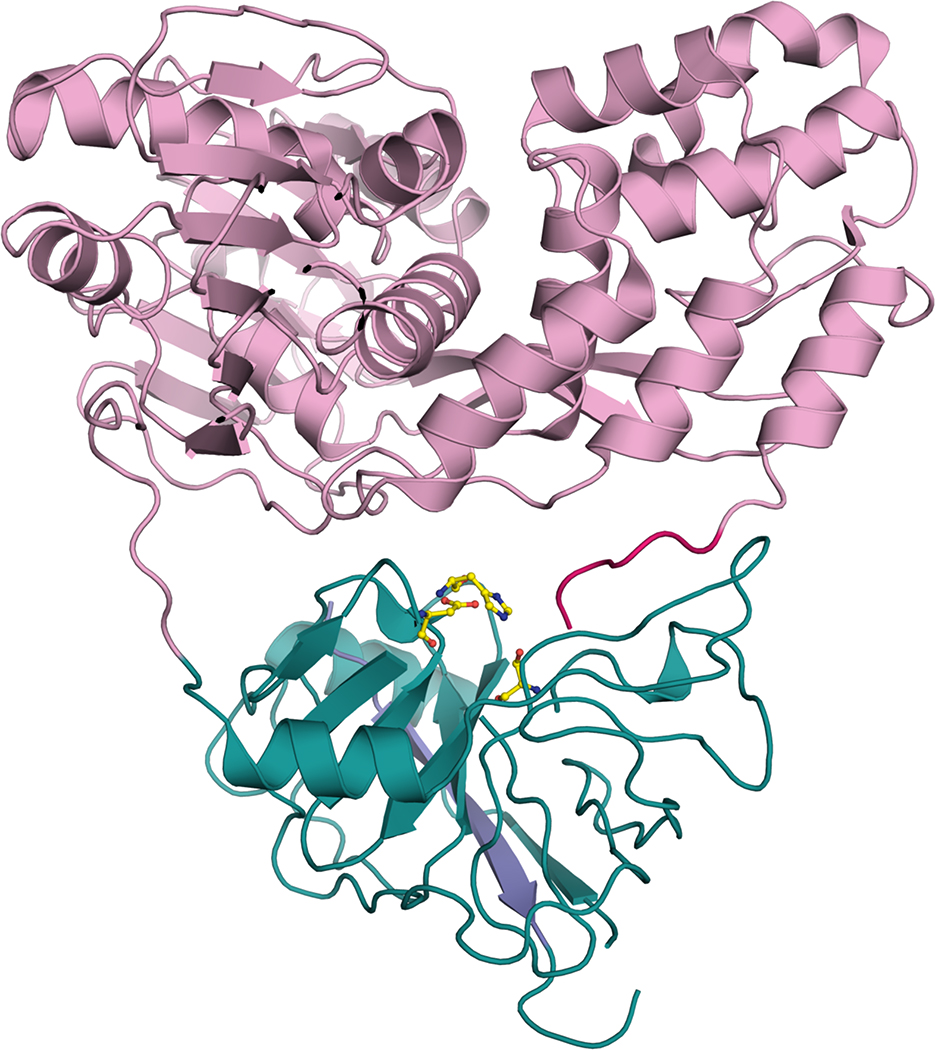

HCV NS3/4A helicase-protease is a 631 amino-acid protein with two domains, an N-terminal NTPase/helicase domain and a C-terminal serine protease domain (Figure 1). The protease domain contains two beta-barrel subdomains and a zinc-binding site, with a fold similar to chymotrypsin. NS3 forms a heterodimer with NS4A to form NS3/4A, which is required for the most efficient proteolytic activity (Au and Pockros 2014). NS3/4A cleaves the viral polyprotein at four sites, releasing proteins essential for viral maturation and infectivity. NS3/4A also impairs host-mediated viral elimination by cleaving host proteins, including TRIF, which is involved in TRIF-mediated Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) signaling, and MAVS, which is involved in Cardiff-mediated retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-1) signaling (Banks et al. 2005; Li et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2007; Heim 2013). The catalytic triad (H57, D81, and S139) is located between the two beta-barrel subdomains. The very shallow binding surface of the protease domain presents another challenge for achieving desired drug-like properties in tight binding small molecules (Ozen 2013).

Figure 1.

Structure of HCV NS3/4A helicase-protease. The N-terminal protease domain is in green, the C-terminal helicase domain pink, the last six amino acids in the C-terminus are in magenta, and the NS4A cofactor is blue. The catalytic triad H57, D81, and S139 is displayed as yellow sticks.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has so far approved several PIs for clinical use, including telaprevir, boceprivir, simeprevir, paritaprevir, and grazoprevir (Figure 2) (FDA 2016). Third-generation pan-genotypic NS3/4A protease inhibitors glecaprevir and voxilaprevir are prescribed in combination with an NS5A inhibitor, and achieve high cure rates across all genotypes. However many of these newer regimens are also very costly, so treatment choices are often limited by insurance coverage, and there are still patients who fail therapy due to resistance mutations (Sorbo et al. 2018). NS3/4A PIs are peptidomimetics and competitive active site inhibitors, and they were designed based on the binding pose of the cleavage product of a natural substrate (Llinas-Brunet et al. 1998; Steinkuhler et al. 1998; De Francesco and Migliaccio 2005).

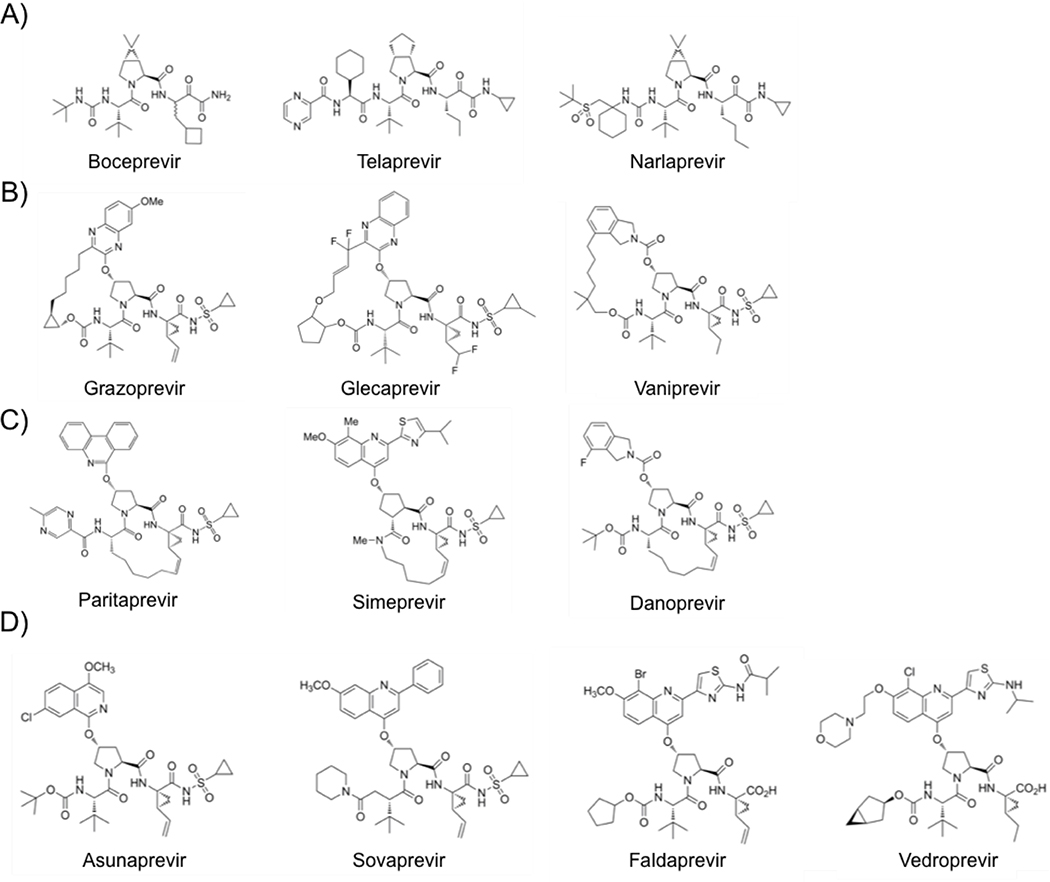

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. A) Linear covalent ketoamide inhibitors, B) P2-P4 macrocyclic inhibitors, C) P1-P3 macrocylic inhibitors, and D) linear non-covalent inhibitors that have been FDA approved or are in Phase II or III clinical trials.

The first NS3/4A PIs, boceprevir and telaprevir, made to the market in 2011. Both are acyclic peptidomimetic ketoamide inhibitors (Lin C et al. 2006; Malcolm et al. 2006; Perni et al. 2006; Kwong et al. 2011) and contain an alpha-ketoamide group that forms a reversible covalent bond with the catalytic serine, S139. In addition, these inhibitors form short-range electrostatic and van der Waals interactions with the binding site (Ozen 2013). Designed to target the active site of genotype 1 NS3/4A proteases, these inhibitors are most effective against genotype 1 and also inhibit genotypes 2, 5, and 6 in vitro, but they are least effective against genotype 3 (Schaefer and Chung 2012; Idrees and Ashfaq 2013). Narlaprevir is another linear ketoamide inhibitor, which has improved potency, pharmacokinetic profile, and physicochemical properties (Arasappan et al. 2010; Idrees and Ashfaq 2013). In addition to the linear covalent ketoamide PIs, there are linear non-covalent peptidomimetics, including faldaprevir, asunaprevir, sovaprevir and vedroprevir (Llinas-Brunet et al. 2010; Agarwal et al. 2012; McPhee et al. 2012; Sheng et al. 2012; Scola et al. 2014; Soumana DI et al. 2014). All four of these inhibitors have a quinoline or isoquinoline moiety in the P2 position. Asunaprevir and sovaprevir are linear acylsulfonamide inhibitors that differ in the P4 capping group and the P2 extension. In addition, sovaprevir demonstrates high potency against all HCV genotypes except genotype 3 and has a better side effect profile (Poordad and Dieterich 2012; Idrees and Ashfaq 2013). Asunaprevir is a highly potent inhibitor with in vitro activity against genotypes 1 and 4, but drug resistance mutations have emerged in patients infected with HCV genotype 1b as well as associated with hepatotoxicity (McPhee et al. 2013; Au and Pockros 2014; De Clercq 2014).

Faldaprevir and vedroprevir are related linear C-terminal carboxylic acid inhibitors that span the P4-P1 substrate sites, and they also differ in the P4 capping group and the P2 extension. These inhibitors were designed based on the observation that the C8 substituent (bromide in faldaprevir and chloride in vedroprevir) on the P2 quinoline B-ring improved the cell-based potency and pharmacokinetic profile of these inhibitors (Llinas-Brunet et al. 2010; Idrees and Ashfaq 2013). In particular, faldaprevir is a selective inhibitor with a good absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profile and favorable pharmacokinetics (Idrees and Ashfaq 2013; Au and Pockros 2014).

The other group of non-covalent NS3/4A PIs is the acylsulfonamide macrocyclic inhibitors, which include vaniprevir, danoprevir, glecaprevir, grazoprevir, paritaprevir, and simeprevir (McCauley et al. 2010; Harper et al. 2012; Idrees and Ashfaq 2013; Jiang et al. 2014; Rosenquist et al. 2014). These inhibitors contain a linker that connects either the P1 and P3 moieties (simeprevir, paritaprevir, and danoprevir) or the P2 and P4 moieties (grazoprevir, glecaprevir, and vaniprevir). In general, macrocyclic PIs demonstrate higher potencies compared to linear inhibitors. Some of these inhibitors possess increased pan-genotypic efficacy, such as grazoprevir, paritaprevir, and glecaprevir (He et al. 2008; Lange et al. 2010; Au and Pockros 2014).

Many of these macrocyclic inhibitors are related compounds with the same core scaffold. Vaniprevir and danoprevir are related compounds with similar isoindoline P2 moieties, P4 capping groups, and carbamate linkages between the P4 and P3 moieties, but they differ in macrocyclization. Vaniprevir demonstrates excellent selectivity against a panel of 169 pharmacologically relevant receptors, enzymes, and ion channels (IC50 > 10 μM) except for chymotrypsin (IC50 = 520 nM), and danoprevir had a low incidence of viral rebound after combined treatment with PEG interferon alpha-2a (Seiwert et al. 2008; Liverton et al. 2010). Grazoprevir and glecaprevir are related compounds that have similar quinoxiline P2 moieties and carbamate linkages between the P4 and P3 moieties, but they differ in the location of the macrocycle, P4 capping groups, and P2 quinoxiline substituents. Grazoprevir is active against genotypes 1, 2, and 3, whereas many NS3/4A PIs lose potency against genotype 3 (Summa et al. 2012). Paritaprevir, which is an inhibitor developed by Abbvie, has a phenanthridine P2 moiety, and it was FDA approved in December 2014 in a combination medication with ombitasvir and ritonavir (Poordad et al. 2013). Simeprevir is smaller than other macrocyclic inhibitors, with a P1-P3 macrocycle and a quinoline P2 group. Simeprevir spans the P3-P1’ sites compared to the other macrocyclic inhibitors, which span the P4-P1’ sites, and has a high selectivity ratio of 5,785 in vitro, which is the ratio of the 50% cytotoxic concentration and the 50% effective concentration in cell-based assays (Lin TI et al. 2009). Over the past few years, pan-genotypic inhibitors have also been developed. Glecaprevir is an FDA-approved P2-P4 macrocylic inhibitor that is highly potent against many genotypes (EC50 = 0.85–2.7 nM), and in particular, it has high activity against genotype 3a (EC50 = 1.6 nM) (Levin 2014).

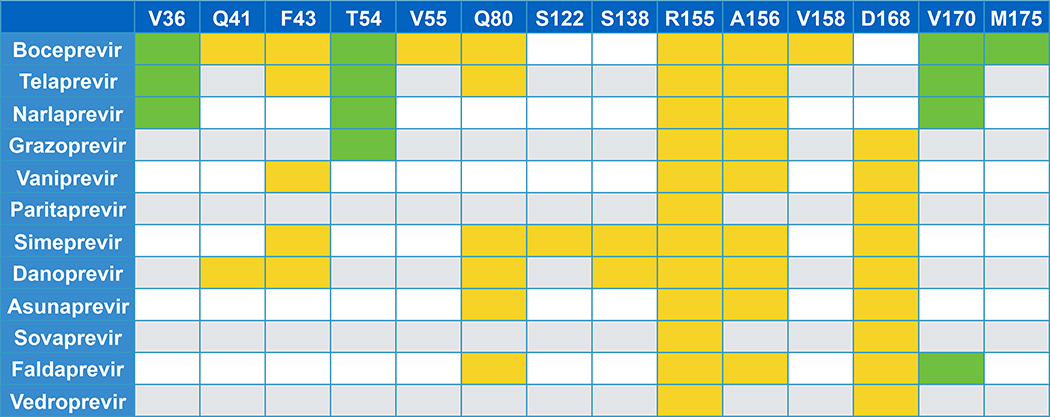

Drug Resistance to HCV NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors

Drug resistance mutations have emerged against HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors both experimentally and clinically (Lin C et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2006; Kieffer et al. 2007; Sarrazin et al. 2007; He et al. 2008; Tong et al. 2008; Tong et al. 2010; Jensen et al. 2015; Lontok et al. 2015). These mutations occur both inside and outside the protease active site (Table 1). Drug resistance mutations at residues R155, A156, and D168, located close to the catalytic triad, impact the most inhibitors (Jensen et al. 2015). In addition to single mutations, co-occurring mutations have also been reported, such as R155K/V36M. Boceprevir and telaprevir are the oldest inhibitors and are susceptible to drug resistance, with main drug resistance mutations at residues V36, T54, R155, and A156 (Jensen et al. 2015; Lontok et al. 2015). These resistance mutations also cause thousand-fold changes in Ki and IC50 measurements (Ali et al. 2013). Macrocylic PIs are less susceptible to resistance, but are still impacted by mutations at residues R155, A156, and D168. Grazoprevir has increased activity against multiple genotypes compared to other PIs and a more favorable and flatter drug resistance profile. Grazoprevir is still susceptible to resistance mutations at R155, A156, and D168, but the fold changes in Ki and IC50 measurements vary widely. For instance, the resistance mutation R155K increases the Ki for grazoprevir by 6 fold, but the resulting Ki and IC50 measurements are still subnanomolar. However, for the resistance mutations A156T and D168A, the fold changes in Ki and IC50 are much greater (Romano et al. 2012) with the double variant Y56H/D168A becoming more prevalent in patients failing therapy (Matthew et al. 2018).

Table 1.

Sites of drug resistance mutations to HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors.

|

The top row lists residues where resistance mutations have occurred. Colored boxes indicate that a drug resistance mutation was observed. Green boxes are for residues outside of the active site, and yellow boxes are for residues that contact inhibitors.

Using substrate recognition to understand drug resistance against HIV and HCV protease inhibitors, we discovered that substrates fill a conserved volume within the active site known as the substrate envelope, and primary drug resistance mutations occur where inhibitors protrude outside of the substrate envelope. These residues are often not evolutionarily conserved or are not necessary for biological function (Prabu-Jeyabalan et al. 2002; Romano et al. 2010). Although many structures of PIs in complex with the NS3/4A protease have been reported, a systematic review of these crystal structures in the context of the substrate envelope has not been performed. We used the substrate envelope to analyze crystal structures of NS3/4A protease in complex with inhibitors and also modeled four additional PIs. Understanding how different patterns of drug resistance have emerged for different classes of NS3/4A PIs and applying this information to predict resistance would be useful for designing inhibitors that are less susceptible to resistance.

Results

Substrate Envelope

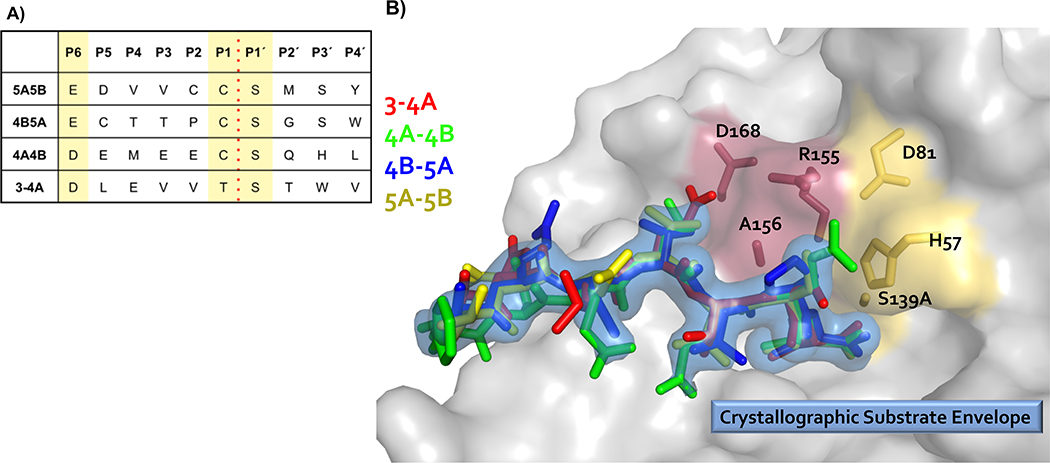

High resolution crystal structures of the protease domain in complex with cleavage products of four viral polyprotein substrates demonstrate that viral substrates with diverse sequences adopt a conserved shape at the binding site, known as the substrate envelope (Figure 3). Most severe drug resistance mutations occur where inhibitors protrude beyond the substrate envelope and contact binding site residues more important for inhibitor binding compared to substrate binding (King et al. 2004; Romano et al. 2012).

Figure 3.

Viral substrates of HCV NS3/4A protease share a conserved binding shape at the active site. (A) Amino acid cleavage site sequences of four HCV NS3/4A protease viral substrates. (B) Viral substrates fill a conserved volume in the active site known as the crystallographic substrate envelope. The NS3/4A protease domain is in gray surface representation. Substrate 3–4A is in red sticks, substrate 4A-4B is in green sticks, substrate 4B-5A is in blue sticks, substrate 5A-5B is in yellow sticks, and the substrate envelope is in blue surface representation. The catalytic triad D81, H57, and S139 is in yellow sticks, and sites of major drug resistance mutations are in burgundy sticks.

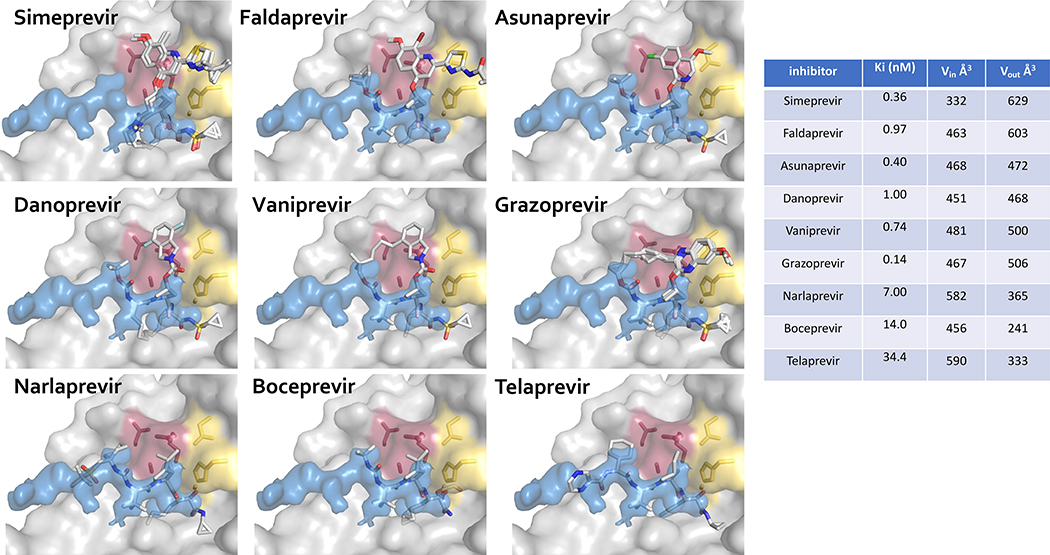

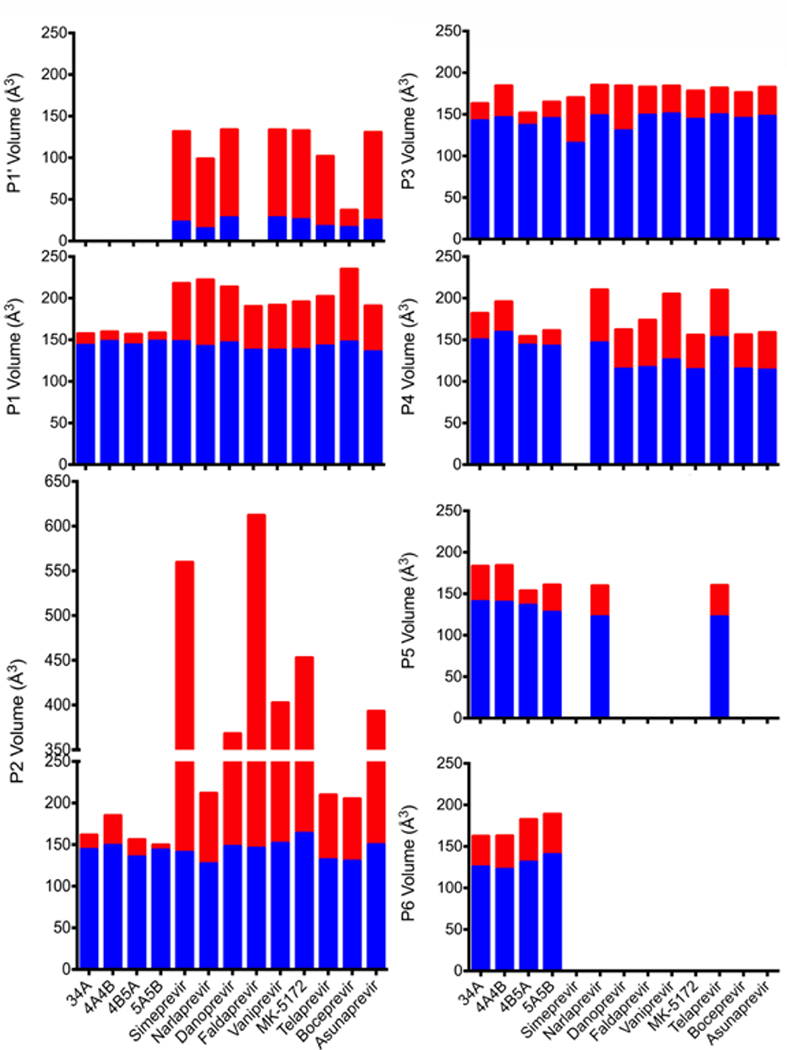

The volume of an inhibitor that falls outside the substrate envelope, quantified as VOUT, trend with susceptibility to drug resistance (Figures 4 and 5). The linear ketoamide inhibitors telaprevir, boceprevir, and narlaprevir do not protrude outside of the substrate envelope in the P2 moiety as much as the macrocylic inhibitors, and consequently they have lower VOUT volumes. However, the macrocylic inhibitors have higher potency, with better Ki and IC50 values (Ali et al. 2013). For linear ketoamide inhibitors in the presence of drug resistance mutations, fold changes in Ki and IC50 values range from 2–20 fold, whereas these same changes in macrocyclic inhibitors are 10–1000 fold (Ali et al. 2013). However, since macrocyclic inhibitors have much stronger subnanomolar or nanomolar binding affinity toward wild-type protease, losses of affinity in drug resistant variants still result in relatively tight binding inhibitors. For instance, vaniprevir and grazoprevir have subnanomolar activity against wild-type NS3/4A protease, and these inhibitors still retain nanomolar activity in the presence of drug resistance mutations. (Ali et al. 2013)

Figure 4.

Inhibitors protruding outside of the substrate envelope in HCV NS3/4A protease. Drug resistance mutations occur where inhibitors protrude beyond the substrate envelope and contact residues that are not essential for substrate binding. The NS3/4A protease domain is in gray surface representation, and the substrate envelope is in blue surface representation. The catalytic triad D81, H57, and S139 is in yellow sticks, and drug resistance residues R155, A156, and D168 are in burgundy sticks. Inhibitors are displayed in stick representation with carbon atoms in gray and other atoms in standard CPK colors. The volume of each inhibitor inside (Vin) and outside (Vout) the substrate envelope is reported in Å3. MK-5172 is grazoprevir.

Figure 5.

Volume of substrates and inhibitors inside (VIN) and outside (VOUT) of the substrate envelope by substrate moiety. VIN is blue and VOUT is in red. If inhibitors did not occupy a particular substrate moiety, VIN and VOUT were not calculated (such as with the P6 moiety). Ligands are listed on the horizontal axis, and the calculated volumes are on the vertical axis in Å3. MK-5172 is grazoprevir.

However, many inhibitors do not take advantage of the full substrate envelope to make additional contacts with the protease. The portion of the substrate envelope that is not occupied by any inhibitor atom can be quantified as Vremaining. Only narlaprevir and telaprevir extend into the P5 position and none of the inhibitors extend into the P6 position. This region of the substrate envelope is more dynamic (Ozen et al. 2013), but still useful for designing compounds that are less susceptible to drug resistance. Optimizing the balance between staying within and filling the substrate envelope, minimizing protrusions from the substrate envelope, and maintaining a high level of activity are important for designing potent inhibitors with flat resistance profiles (Kurt Yilmaz et al. 2016).

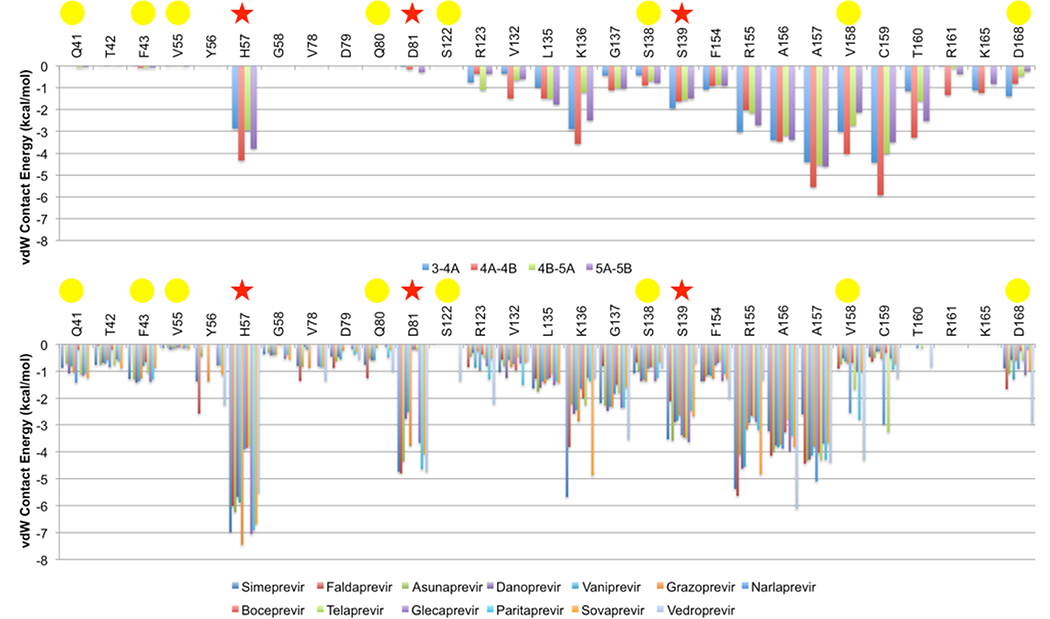

Van der Waals Contact Energy

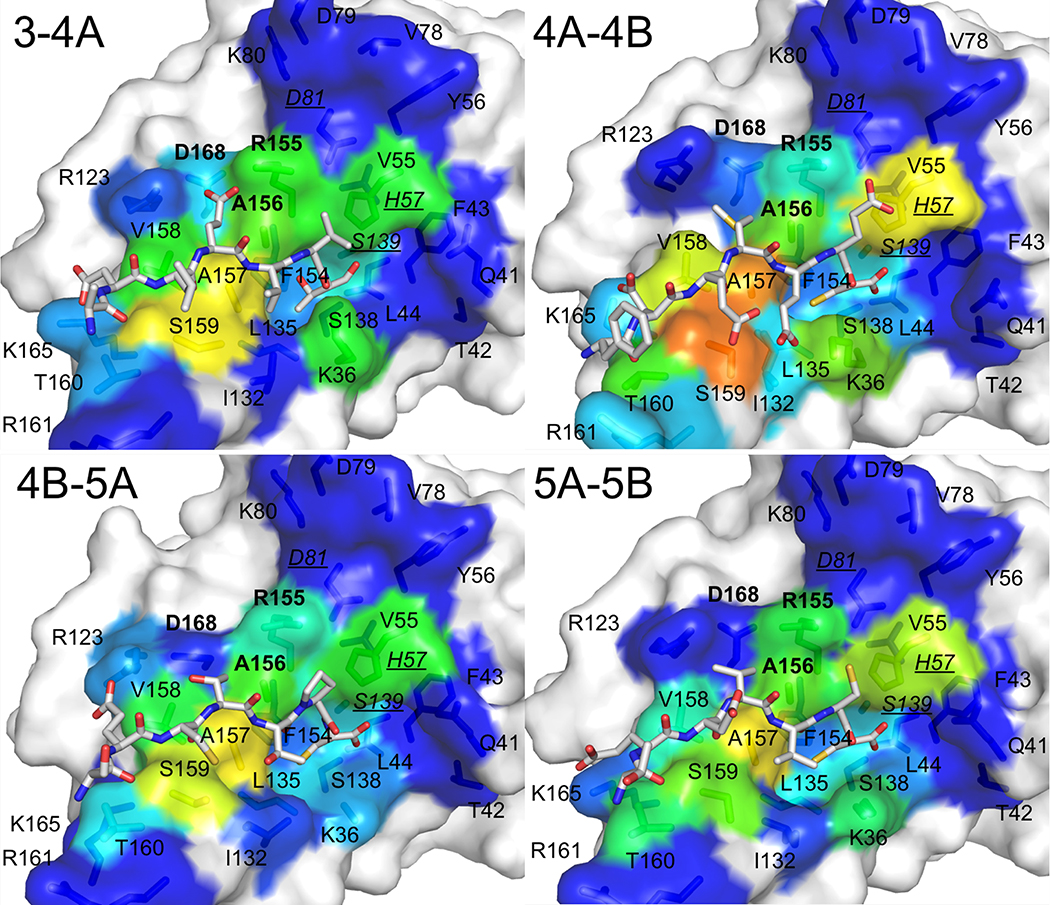

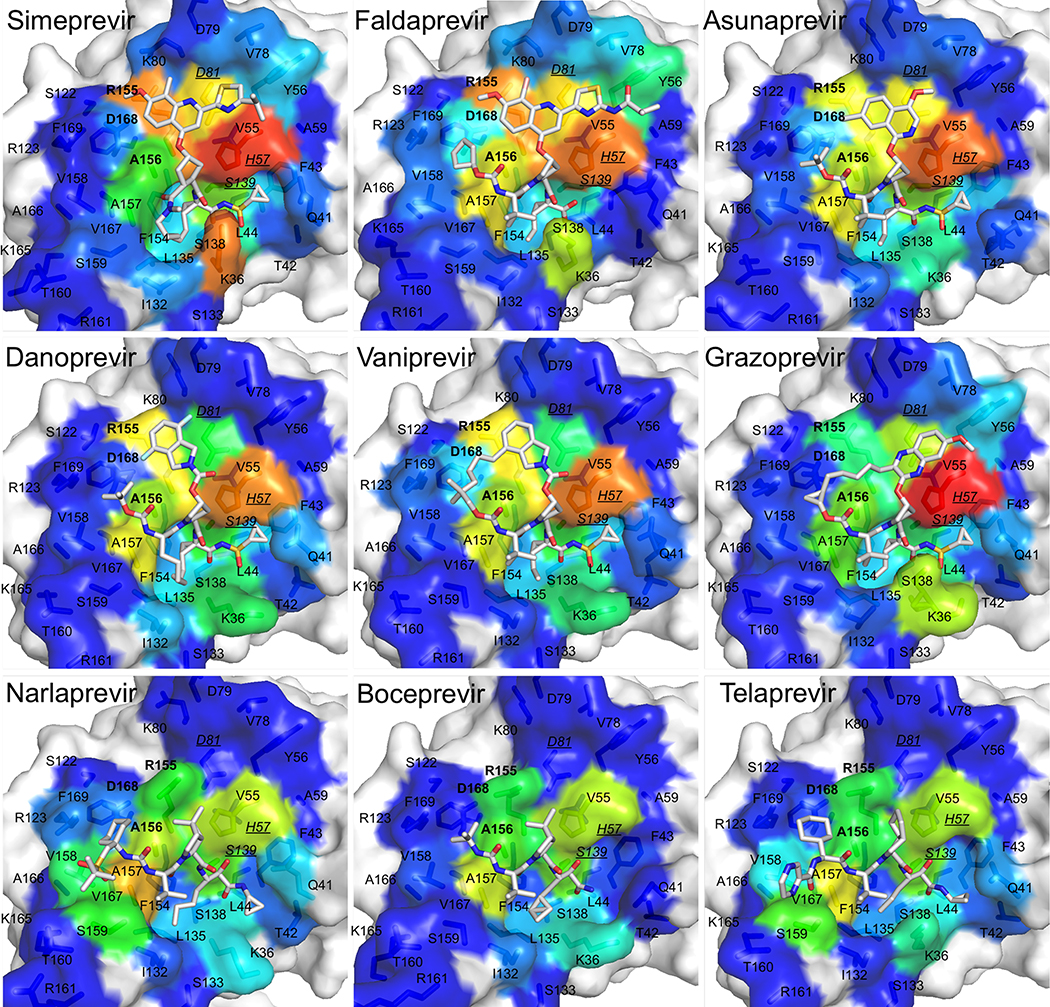

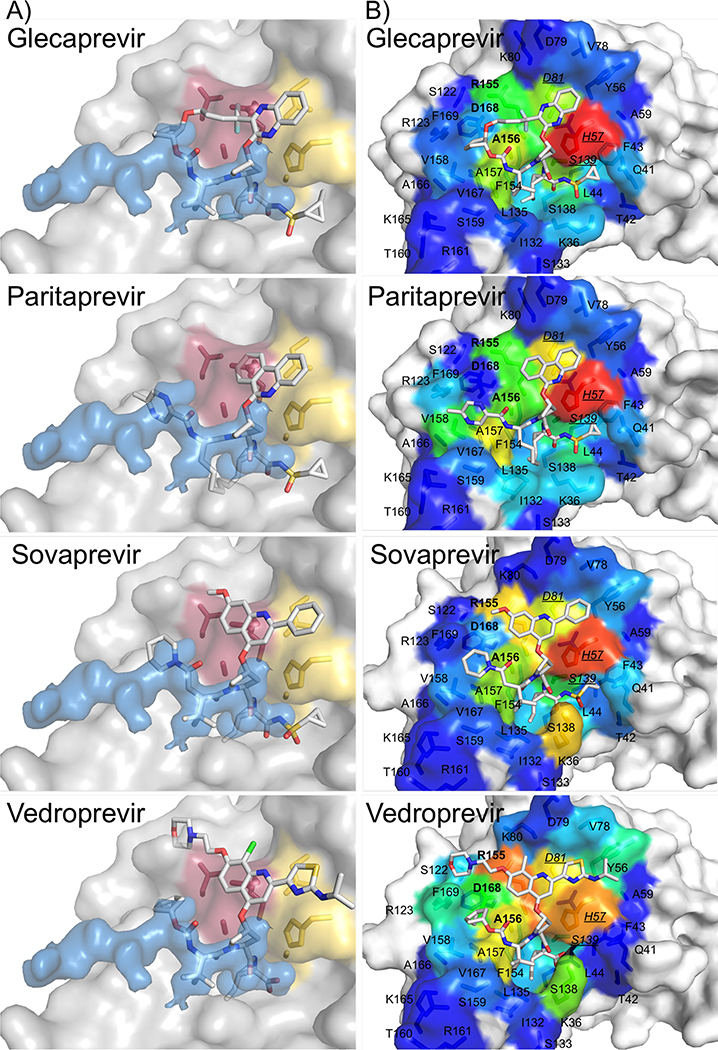

Van der Waals contacts of substrates and inhibitors with the protease were calculated and mapped onto the binding surface (Figures 6 and 7). The binding pose was modeled when a crystal structure was not available (glecaprevir, paritaprevir, sovaprevir, and vedroprevir) (Figure 8). All surface van der Waals figures were colored on the same energy scale from 0 to a maximum of approximately −7.4 kcal/mol according to the per residue van der Waals contact energies (Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Substrate van der Waals contacts mapped on the surface of the NS3/4A protease active site for each substrate. The protease domain is in gray surface representation, and the contact surface is in rainbow spectrum colors where tangential contacts are in blue and warmer colors indicate stronger van der Waals contact interactions. Substrates are in stick representation with carbon atoms in gray and other atoms in standard CPK colors. Residues in bold are drug resistance residues R155, A156, and D168. Underlined italicized residues are the catalytic residues H57, D81, and S139.

Figure 7.

Inhibitor van der Waals contacts mapped on the surface of the NS3/4A protease active site. The protease domain is in gray surface representation, and the contact surface is in rainbow spectrum colors where tangential contacts are in blue and warmer colors indicate stronger van der Waals contacts interactions. Inhibitors are in stick representation with carbon atoms in gray and other atoms in standard CPK colors. Residues in bold are drug resistance residues R155, A156, and D168. Underlined italicized residues are the catalytic residues H57, D81, and S139.

Figure 8.

Substrate envelope and van der Waals surface representations for modeled HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. A) The NS3/4A protease domain is in gray surface representation, and the substrate envelope is in blue surface representation. The catalytic triad D81, H57, and S139 is in yellow sticks, and sites of drug resistance residues R155, A156, and D168 are in burgundy sticks. B) Inhibitor van der Waals contacts mapped on the surface of the NS3/4A protease active site. Residues in bold are drug resistance residues R155, A156, and D168. Underlined italicized residues are the catalytic residues H57, D81, and S139.

Figure 9.

Differential van der Waals interactions on the binding surface of HCV NS3/4A protease. (A) Per residue van der Waals contacts interactions for each viral substrate. (B) Per residue van der Waals contacts for inhibitors. Red stars indicate catalytic residues, and yellow circles indicate drug resistance residues.

In general, van der Waals contact patterns vary depending on the macrocyclization and the type of moiety that extends from the P2 position. The differential patterns of van der Waals contacts trend with the differential patterns of drug resistance. All inhibitors, compared to the substrates, make increased contacts with catalytic residues H57, D80, and S139 that are evolutionarily conserved and required for biological function, so they are less likely to mutate and confer drug resistance.

Grazoprevir has the best activity and also is able to accommodate drug resistance mutations at residues R155 and D168. The quinoxiline group in grazoprevir stacks most favorably on the catalytic triad (H57, D80, S139) and this binding mode is retained even when the macrocycle is removed (Ali et al. 2013; Soumana DI, Kurt Yilmaz, Prachanronarong, et al. 2016; Matthew et al. 2017; Rusere et al. 2018). Out of all the macrocyclic inhibitors with extended P2 moieties, grazoprevir appears to make the least contacts with R155 and D168. Glecaprevir has a quinoxiline group that would also likely stack against the catalytic triad. However, the P2-P4 macrocycle in glecaprevir has two additional fluorine atoms, and the P4 moiety has a five membered ring instead of a three membered ring, so these differences may impact how glecaprevir behaves in the presence of resistance mutations. Paritaprevir has a phenanthridine group in the extended P2 position, and this moiety also seems to stack well on the catalytic triad. Paritaprevir has a P1-P3 macrocycle instead of a P2-P4 macrocycle, and makes slightly less contacts with A156 compared to glecaprevir and grazoprevir; this difference may allow paritaprevir to better accommodate resistance mutations at A156. In addition, compounds without a P2-P4 macrocycle are less susceptible to mutations at R155 and D168 (Ozen 2013; Soumana D 2015).

Compounds with quinoline, isoquinoline, and isoindoline at the P2 extended position have worse resistance profiles against mutations at residues R155, A156, and D168 compared to compounds like grazoprevir with a quinoxiline at this position. These inhibitors include asunaprevir, danoprevir, and vaniprevir, whose P2 moieties contact R155, A156, and D168 (Ali et al. 2013; Soumana D 2015). Rather than stacking on the catalytic triad, these moieties stack on these primary drug resistance sites, which contribute to the susceptibility to mutations at these locations.

Inhibitors with a P1-P3 macrocycle, such as simeprevir and danoprevir, are more susceptible to resistance mutations at S138, which is located close to the P1-P3 macrocycle binding site. Based on the van der Waals analysis, other inhibitors with a P1-P3 macrocycle, such as paritaprevir, are predicted to be susceptible to mutations at this location.

Simeprevir and faldaprevir have P2 moieties that protrude outside the substrate envelope in both the direction of the catalytic triad and major drug resistance residues. Simeprevir is susceptible to mutations as S122, but not faldaprevir, even though both inhibitors are similar at this position. However, faldaprevir has additional contacts in the S4 pocket whereas simeprevir only extends to the S3 pocket. These additional interactions in S4 may help stabilize faldaprevir in the presence of mutations at S122 even though S122 is located distal from the S4 pocket. Sovaprevir is similar to faldaprevir and simeprevir at this location, but has more extensive contacts in the S4 pocket, so it may be able to accommodate resistance mutations at S122. Vedroprevir has the largest P2 moiety of all the inhibitors analyzed in this study, and contacts extensively with R155, D168, and S122. Thus vedroprevir is also likely susceptible to drug resistance mutations at these locations.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, simeprevir, danoprevir, asunaprevir, and faldaprevir are susceptible to mutations at Q80. Q80K is a polymorphism that impacts the activity of most PIs. The mechanism of resistance conferred by Q80K is not clear, especially for inhibitors that do not directly contact this residue (boceprevir and telaprevir), but the charge change due to this polymorphism likely impacts the electrostatic network of residues around residue 80. Residue 80 is located at the edge of the binding site and has come contact with the P2-moiety of inhibitors simeprevir, danoprevir, asunaprevir, and faldaprevir. Therefore, mutations at residue 80 may have some direct impact on binding of these inhibitors. In addition, sovaprevir and vedroprevir make tangential contacts with residue 80 and may also be susceptible to substitutions at this location.

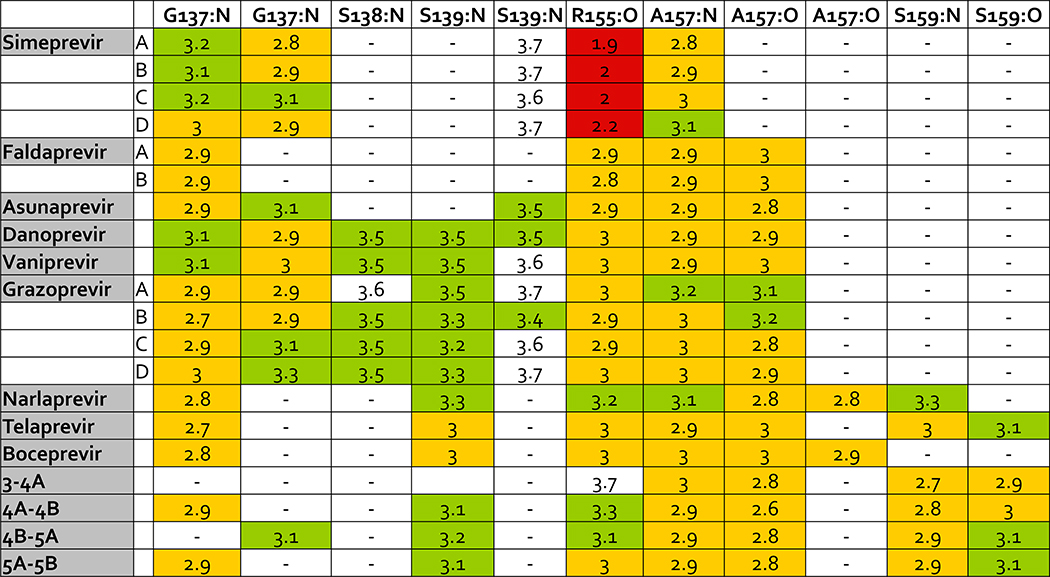

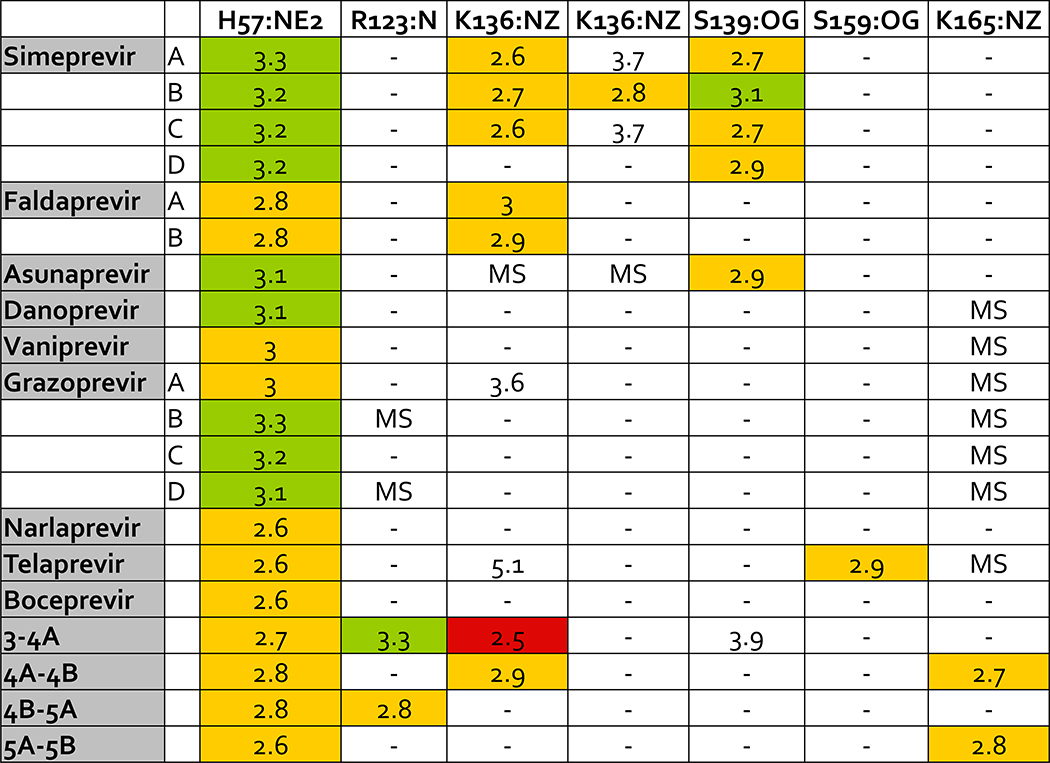

Hydrogen Bond Interactions

Specific hydrogen bonds were also calculated for inhibitors and substrates in complex with the protease for backbone and side chain atoms (Figures 10 and 11). Overall, inhibitors have similar hydrogen bonds as substrates to backbone atoms in the protease but compared to substrates, inhibitors also make more hydrogen bonds to side chains of the conserved catalytic residues H57 and S139. Acidic side chains of substrates hydrogen bond with residues K165 and K136, which is not as common in inhibitors. In a comparison of the crystal structures analyzed in this study, K136 appears to occupy different conformations. In addition, acidic residues at P6 in the substrate interact with K165, but this interaction has also been shown to be highly dynamic (Ozen 2013), so incorporating these hydrogen bonds into inhibitors would require accounting for the target’s conformational flexibility.

Figure 10.

Hydrogen bond interactions between ligands and backbone atoms in the HCV NS3/4A protease active site. Backbone atoms are listed on the top row with the residue name and number and the name of the backbone atom. Backbone atoms listed twice make more than one hydrogen bond with ligand atoms. Crystal structures with more than one ligand-protease complex in the asymmetric unit are listed by chain letter. Distances less than or equal to 2.5 Å are red, distances greater than 2.5 Å and less than or equal to 3.0 Å are yellow, and distances greater than 3.0 Å and less than or equal to 3.5 Å are green. MK-5172 is grazoprevir.

Figure 11.

Hydrogen bond interactions between ligands and side chain atoms in the HCV NS3/4A protease active site. Side chain atoms are listed on the top row with the residue name and number and the name of the backbone atom. Side chain atoms listed twice make more than one hydrogen bond with ligand atoms. Crystal structures with more than one ligand-protease complex in the asymmetric unit are listed by chain letter. Distances less than or equal to 2.5 Å are red, distances greater than 2.5 Å and less than or equal to 3.0 Å are yellow, and distances greater than 3.0 Å and less than or equal to 3.5 Å are green. MK-5172 is grazoprevir. MS indicates a missing side chain.

Leveraging simulations to further characterize resistance

In many cases crystal structures alone have been shown to be inadequate to characterize the molecular mechanisms by which resistance occurs to NS3/4A. To augment the structural analysis molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations have been used. These include definition of a dynamic substrate envelope (Ozen et al. 2013) and differential dynamics for of genotype 3 (Soumana DI, Kurt Yilmaz, Ali, et al. 2016) to elucidate the mechanism by which inhibitor binding is disrupted. Additionally, structural and dynamic analysis revealed mechanisms by which single site mutations contribute to resistance due to single (Guan et al. 2014; Guan et al. 2015) and double mutations (Wang et al. 2014; Matthew et al. 2018) in the protease and in the full-length enzyme (Xue et al. 2012; Aydin et al. 2013; Xue et al. 2014).

Discussion

Inhibitors with P2-P4 macrocyclization and a quinoxiline-related P2 moiety tend to have higher activity and stack well against the conserved catalytic triad in the active site, but P1-P3 macrocycle compounds are balanced between high potency and increased flexibility to accommodate resistance mutations and tend to have a flatter resistance profile. Therefore, drug design strategies focusing on inhibitors with a P1-P3 macrocycle and flexible quinoxiline-related P2 moieties may be an optimal strategy (Matthew et al. 2018), given high potency can be achieved without compromising the resistance profile.

Another drug design strategy is extending inhibitors in the P1’ and P4-P6 regions to make increased contacts with conserved residues in the S1’ and S4-S6 pockets to increase inhibitor potency while decreasing susceptibility to drug resistance mutations (Ozen 2013; Ozen et al. 2013). For instance, simeprevir does not have any contacts in the S4 pocket and is susceptible to resistance mutations at S122 while faldaprevir makes additional contacts in the S4 pocket and is not susceptible to this resistance mutation even though the P2 extended moieties in both compounds are similar. Increased contacts with the conserved active site may allow the inhibitor better accommodate specific resistance mutations. In addition, there are many basic residues in the S6 pocket, such as R119, R123, R161, and K165, which make conserved interactions with the conserved acidic D or E residue at the P6 position of the substrate. Making additional electrostatic interactions with these residues may also increase the potency of inhibitors but may also be challenging without decreasing the cLogP and thus cell permeability of the ligand, and because this region is dynamic (Ozen 2013).

Our review and structural analysis has shown that differences in how inhibitors fit within the substrate envelope and interact with the binding site trend with differential drug resistance patterns. Incorporation of the substrate envelope hypothesis into structure based drug design would facilitate the development of robust inhibitors with a higher barrier to resistance while keeping potency.

Methods

Substrate Envelope and VIN and VOUT Calculations

We analyzed crystal structures of NS3/4A protease in complex with inhibitors. These structures include the protease in complex with telaprevir (3SV6), boceprevir (5EBQ), narlaprevir (3LON), faldaprevir (3P8N), simeprevir (3KEE), asunaprevir (4WF8), danoprevir (3M5L), vaniprevir (3SU3), and grazoprevir (3SUD) (Cummings et al. 2010; Lemke et al. 2011; Romano et al. 2012; Soumana DI et al. 2014). The substrate envelope was calculated using crystal structures of NS3/4A protease in complex with substrate cleavage products 4A-4B (3M5M), 4B-5A (3M5N), and 5A-5B (3M5O) (Romano et al. 2010). The structure of the substrate cleavage product 3–4A in complex with NS3/4A protease was modeled from the full-length crystal structure as previously described (1CU1) (Yao et al. 1999; Romano et al. 2010). The PDB IDs for each of these structures is in parentheses. The models of glecaprevir, paritaprevir, sovaprevir, and vedroprevir were generated based on similar fragments of inhibitors from the existing crystal structures listed, and models were minimized using Maestro in the Schrodinger Software Suite (Schrodinger 2015). The substrate envelope was generated in PyMOL as previously described (Romano et al. 2010).

Details of the VIN and VOUT volume calculations have been described previously and were performed using in-house Fortran scripts (Ozen et al. 2011). VOUT is the volume of inhibitor that protrudes outside of the substrate envelope, and VIN is the volume of inhibitor inside the substrate envelope. Briefly, to perform these calculations, a three dimensional grid was placed onto the binding site, and each grid cell is defined by the indices i,j,k. Then, an initial value of zero is assigned to each grid cell. The variable gijk,1 is the number of times an inhibitor occupies the grid cell with indices i,j,k and gijk,2 is the number of times the same grid cell is occupied by the substrates. A grid cell value is increased by 1 when a substrate or inhibitor atom based on the OPLS2005 van der Waals radius occupies the grid cell. N1 and N2 are equal to the number of static crystal structure calculations for the inhibitor (N1=1) and substrates (N2=4), respectively. The details are described elsewhere (Ozen et al. 2011).

Van der Waals Contact Potential Energy

The van der Waals contact potential energies between ligands and the protease were calculated in each structure using a simplified Lennard-Jones potential function where the repulsive terms are not accounted for if the interaction energy between any two atoms is larger than a cut-off of −1 kcal/mol. The non-bonded parameters were determined using the OPLS2005 force field (Banks et al. 2005). Further details of this computation have been described previously (Ozen et al. 2011).

Hydrogen Bond Interactions

Hydrogen bonds were determined using Maestro. A hydrogen bond was defined as having a donor-acceptor distance of a maximum of 3.5 Å and involving only polar atoms nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and fluorine. The donor minimum angle was 120 degrees and the acceptor minimum angle was 90 degrees, according to the default settings.

Plots and Figures

Microsoft Excel, Matlab, Prism, and PyMOL were used to create all plots and figures (Schrodinger 2010; The MathWorks 2014; GraphPad Software 2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R01-AI085051). DIS was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (F31-GM103259). ANM was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the (F31 GM119345). We thank Dr. Nese Kurt Yilmaz for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Agarwal A, Zhang B, Olek E, Robison H, Robarge L, Deshpande M. 2012. Rapid and sharp decline in HCV upon monotherapy with NS3 protease inhibitor, ACH-1625. Antivir Ther. 17(8):1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Aydin C, Gildemeister R, Romano KP, Cao H, Ozen A, Soumana D, Newton A, Petropoulos CJ, Huang W et al. 2013. Evaluating the role of macrocycles in the susceptibility of hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitors to drug resistance. ACS Chem Biol. 8(7):1469–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasappan A, Bennett F, Bogen SL, Venkatraman S, Blackman M, Chen KX, Hendrata S, Huang Y, Huelgas RM, Nair L et al. 2010. Discovery of Narlaprevir (SCH 900518): A Potent, Second Generation HCV NS3 Serine Protease Inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 1(2):64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au JS, Pockros PJ. 2014. Novel therapeutic approaches for hepatitis C. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 95(1):78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin C, Mukherjee S, Hanson AM, Frick DN, Schiffer CA. 2013. The interdomain interface in bifunctional enzyme protein 3/4A (NS3/4A) regulates protease and helicase activities. Protein Sci. 22(12):1786–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks JL, Beard HS, Cao Y, Cho AE, Damm W, Farid R, Felts AK, Halgren TA, Mainz DT, Maple JR et al. 2005. Integrated Modeling Program, Applied Chemical Theory (IMPACT). J Comput Chem. 26(16):1752–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukh J, Miller RH, Purcell RH. 1995a. Biology and genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 13 Suppl 13:S3–7. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukh J, Miller RH, Purcell RH. 1995b. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies and genotypes. Semin Liver Dis. 15(1):41–63. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Benureau Y, Rijnbrand R, Yi J, Wang T, Warter L, Lanford RE, Weinman SA, Lemon SM, Martin A et al. 2007. GB virus B disrupts RIG-I signaling by NS3/4A-mediated cleavage of the adaptor protein MAVS. J Virol. 81(2):964–976. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings MD, Lindberg J, Lin TI, de Kock H, Lenz O, Lilja E, Fellander S, Baraznenok V, Nystrom S, Nilsson M et al. 2010. Induced-fit binding of the macrocyclic noncovalent inhibitor TMC435 to its HCV NS3/NS4A protease target. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 49(9):1652–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E 2014. Current race in the development of DAAs (direct-acting antivirals) against HCV. Biochem Pharmacol. 89(4):441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco R, Migliaccio G. 2005. Challenges and successes in developing new therapies for hepatitis C. Nature. 436(7053):953–960. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- mFDA. 2016. Drugs @ FDA. Federal Drug Administration. [Google Scholar]

- GraphPad Software. 2016. GraphPad Prism for Mac OSX, Version 6.0 San Diego, California, USA: GraphPad Software. [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Sun H, Li Y, Pan P, Li D, Hou T. 2014. The competitive binding between inhibitors and substrates of HCV NS3/4A protease: a general mechanism of drug resistance. Antiviral Res. 103:60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Sun H, Pan P, Li Y, Li D, Hou T. 2015. Exploring resistance mechanisms of HCV NS3/4A protease mutations to MK5172: insight from molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. Mol Biosyst. 11(9):2568–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S, McCauley JA, Rudd MT, Ferrara M, DiFilippo M, Crescenzi B, Koch U, Petrocchi A, Holloway MK, Butcher JW et al. 2012. Discovery of MK-5172, a Macrocyclic Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4a Protease Inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 3(4):332–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, King MS, Kempf DJ, Lu L, Lim HB, Krishnan P, Kati W, Middleton T, Molla A. 2008. Relative replication capacity and selective advantage profiles of protease inhibitor-resistant hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protease mutants in the HCV genotype 1b replicon system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 52(3):1101–1110. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim MH. 2013. Innate immunity and HCV. J Hepatol. 58(3):564–574. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idrees S, Ashfaq UA. 2013. HCV infection and NS-3 serine protease inhibitors. Virology & Mycology. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SB, Serre SB, Humes DG, Ramirez S, Li YP, Bukh J, Gottwein JM. 2015. Substitutions at NS3 Residue 155, 156, or 168 of Hepatitis C Virus Genotypes 2 to 6 Induce Complex Patterns of Protease Inhibitor Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59(12):7426–7436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Andrews SW, Condroski KR, Buckman B, Serebryany V, Wenglowsky S, Kennedy AL, Madduru MR, Wang B, Lyon M et al. 2014. Discovery of danoprevir (ITMN-191/R7227), a highly selective and potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3/4A protease. J Med Chem. 57(5):1753–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer TL, Sarrazin C, Miller JS, Welker MW, Forestier N, Reesink HW, Kwong AD, Zeuzem S. 2007. Telaprevir and pegylated interferon-alpha-2a inhibit wild-type and resistant genotype 1 hepatitis C virus replication in patients. Hepatology. 46(3):631–639. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Schiffer CA. 2004. Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: lessons from HIV-1 protease. Chem Biol. 11(10):1333–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt Yilmaz N, Swanstrom R, Schiffer CA. 2016. Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 24(7):547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong AD, Kauffman RS, Hurter P, Mueller P. 2011. Discovery and development of telaprevir: an NS3–4A protease inhibitor for treating genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus. Nat Biotechnol. 29(11):993–1003. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CM, Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. 2010. Review article: specifically targeted anti-viral therapy for hepatitis C - a new era in therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 32(1):14–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke CT, Goudreau N, Zhao S, Hucke O, Thibeault D, Llinas-Brunet M, White PW. 2011. Combined X-ray, NMR, and kinetic analyses reveal uncommon binding characteristics of the hepatitis C virus NS3-NS4A protease inhibitor BI 201335. J Biol Chem. 286(13):11434–11443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JNTP-M, T.; Lu L; Reisch T; Dekhtyar T,; Krishnan P; Beyer J; Tripathi R; Pithawalla R; Asatryan A; Campbell A; Kort J; Collins C 2014. A Next Generation HCV DAA Combination: Potent, Pangenotypic Inhibitors ABT-493 and ABT-530 With High Barriers to Resistance. 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; November 7–11, 2014; Boston, Massachusetts, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Foy E, Ferreon JC, Nakamura M, Ferreon AC, Ikeda M, Ray SC, Gale M Jr., Lemon SM. 2005. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the Toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102(8):2992–2997. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Gates CA, Rao BG, Brennan DL, Fulghum JR, Luong YP, Frantz JD, Lin K, Ma S, Wei YY et al. 2005. In vitro studies of cross-resistance mutations against two hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J Biol Chem. 280(44):36784–36791. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Kwong AD, Perni RB. 2006. Discovery and development of VX-950, a novel, covalent, and reversible inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3.4A serine protease. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 6(1):3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TI, Lenz O, Fanning G, Verbinnen T, Delouvroy F, Scholliers A, Vermeiren K, Rosenquist A, Edlund M, Samuelsson B et al. 2009. In vitro activity and preclinical profile of TMC435350, a potent hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 53(4):1377–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverton NJ, Carroll SS, Dimuzio J, Fandozzi C, Graham DJ, Hazuda D, Holloway MK, Ludmerer SW, McCauley JA, McIntyre CJ et al. 2010. MK-7009, a potent and selective inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 54(1):305–311. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas-Brunet M, Bailey M, Fazal G, Goulet S, Halmos T, Laplante S, Maurice R, Poirier M, Poupart MA, Thibeault D et al. 1998. Peptide-based inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 8(13):1713–1718. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas-Brunet M, Bailey MD, Goudreau N, Bhardwaj PK, Bordeleau J, Bos M, Bousquet Y, Cordingley MG, Duan J, Forgione P et al. 2010. Discovery of a potent and selective noncovalent linear inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease (BI 201335). J Med Chem. 53(17):6466–6476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lontok E, Harrington P, Howe A, Kieffer T, Lennerstrand J, Lenz O, McPhee F, Mo H, Parkin N, Pilot-Matias T et al. 2015. Hepatitis C virus drug resistance-associated substitutions: State of the art summary. Hepatology. 62(5):1623–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu L 2015. Liver Transplants. Medscape. [accessed March 16, 2016]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/776313-overview.

- Malcolm BA, Liu R, Lahser F, Agrawal S, Belanger B, Butkiewicz N, Chase R, Gheyas F, Hart A, Hesk D et al. 2006. SCH 503034, a mechanism-based inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3 protease, suppresses polyprotein maturation and enhances the antiviral activity of alpha interferon in replicon cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 50(3):1013–1020. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew AN, Leidner F, Newton A, Petropoulos CJ, Huang W, Ali A, KurtYilmaz N, Schiffer CA. 2018. Molecular Mechanism of Resistance in a Clinically Significant Double-Mutant Variant of HCV NS3/4A Protease. Structure. 26(10):1360–1372 e1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew AN, Zephyr J, Hill CJ, Jahangir M, Newton A, Petropoulos CJ, Huang W, KurtYilmaz N, Schiffer CA, Ali A. 2017. Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors Incorporating Flexible P2 Quinoxalines Target Drug Resistant Viral Variants. J Med Chem. 60(13):5699–5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley JA, McIntyre CJ, Rudd MT, Nguyen KT, Romano JJ, Butcher JW, Gilbert KF, Bush KJ, Holloway MK, Swestock J et al. 2010. Discovery of vaniprevir (MK-7009), a macrocyclic hepatitis C virus NS3/4a protease inhibitor. J Med Chem. 53(6):2443–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee F, Hernandez D, Yu F, Ueland J, Monikowski A, Carifa A, Falk P, Wang C, Fridell R, Eley T et al. 2013. Resistance analysis of hepatitis C virus genotype 1 prior treatment null responders receiving daclatasvir and asunaprevir. Hepatology. 58(3):902–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee F, Sheaffer AK, Friborg J, Hernandez D, Falk P, Zhai G, Levine S, Chaniewski S, Yu F, Barry D et al. 2012. Preclinical Profile and Characterization of the Hepatitis C Virus NS3 Protease Inhibitor Asunaprevir (BMS-650032). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 56(10):5387–5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalam MN, Ali A, Altman MD, Reddy GS, Chellappan S, Kairys V, Ozen A, Cao H, Gilson MK, Tidor B et al. 2010. Evaluating the substrate-envelope hypothesis: structural analysis of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors designed to be robust against drug resistance. J Virol. 84(10):5368–5378. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozen A 2013. Structure and Dynamics of Viral Substrate Recognition and Drug Resistance. University of Massachusetts Medical School. [Google Scholar]

- Ozen A, Haliloglu T, Schiffer CA. 2011. Dynamics of preferential substrate recognition in HIV-1 protease: redefining the substrate envelope. Journal of molecular biology. 410(4):726–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozen A, Sherman W, Schiffer CA. 2013. Improving the Resistance Profile of Hepatitis C NS3/4A Inhibitors: Dynamic Substrate Envelope Guided Design. J Chem Theory Comput. 9(12):5693–5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perni RB, Almquist SJ, Byrn RA, Chandorkar G, Chaturvedi PR, Courtney LF, Decker CJ, Dinehart K, Gates CA, Harbeson SL et al. 2006. Preclinical profile of VX-950, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3–4A serine protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 50(3):899–909. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockros PJDB, A.M.; Bloom AB 2014. Direct acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; [accessed 2014]. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/direct-acting-antivirals-for-the-treatment-of-hepatitisc-virus-infection. [Google Scholar]

- Poordad F, Dieterich D. 2012. Treating hepatitis C: current standard of care and emerging direct-acting antiviral agents. J Viral Hepat. 19(7):449–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poordad F, Lawitz E, Kowdley KV, Cohen DE, Podsadecki T, Siggelkow S, Heckaman M, Larsen L, Menon R, Koev G et al. 2013. Exploratory study of oral combination antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 368(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. 2002. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure. 10(3):369–381. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano KP, Ali A, Aydin C, Soumana D, Ozen A, Deveau LM, Silver C, Cao H, Newton A, Petropoulos CJ et al. 2012. The molecular basis of drug resistance against hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitors. PLoS Pathog. 8(7):e1002832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano KP, Ali A, Royer WE, Schiffer CA. 2010. Drug resistance against HCV NS3/4A inhibitors is defined by the balance of substrate recognition versus inhibitor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107(49):20986–20991. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist A, Samuelsson B, Johansson PO, Cummings MD, Lenz O, Raboisson P, Simmen K, Vendeville S, de Kock H, Nilsson M et al. 2014. Discovery and development of simeprevir (TMC435), a HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor. J Med Chem. 57(5):1673–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusere LN, Matthew AN, Lockbaum GJ, Jahangir M, Newton A, Petropoulos CJ, Huang W, Kurt Yilmaz N, Schiffer CA, Ali A. 2018. Quinoxaline-Based Linear HCV NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors Exhibit Potent Activity against Drug Resistant Variants. ACS Med Chem Lett. 9(7):691–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin C, Rouzier R, Wagner F, Forestier N, Larrey D, Gupta SK, Hussain M, Shah A, Cutler D, Zhang J et al. 2007. SCH 503034, a novel hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor, plus pegylated interferon alpha-2b for genotype 1 nonresponders. Gastroenterology. 132(4):1270–1278. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer EA, Chung RT. 2012. Anti-hepatitis C virus drugs in development. Gastroenterology. 142(6):1340–1350 e1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodinger, LLC. Forthcoming 2010. August The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1.

- Schrodinger, LLC. Forthcoming 2015. Maestro, Version 10.2. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Scola PM, Sun LQ, Wang AX, Chen J, Sin N, Venables BL, Sit SY, Chen Y, Cocuzza A, Bilder DM et al. 2014. The discovery of asunaprevir (BMS-650032), an orally efficacious NS3 protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Chem. 57(5):1730–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert SD, Andrews SW, Jiang Y, Serebryany V, Tan H, Kossen K, Rajagopalan PT, Misialek S, Stevens SK, Stoycheva A et al. 2008. Preclinical characteristics of the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitor ITMN-191 (R7227). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 52(12):4432–4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng XC, Appleby T, Butler T, Cai R, Chen X, Cho A, Clarke MO, Cottell J, Delaney WEt, Doerffler E et al. 2012. Discovery of GS-9451: an acid inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 22(7):2629–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman E 2014. August 12, 2014 From Riches to Rags: Vertex Discontinues Incivek as Sales Evaporate. The Wall Street Journal. http://blogs.wsj.com/pharmalot/2014/08/12/from-riches-to-rags-vertex-discontinues-incivek-as-sales-evaporate/. [Google Scholar]

- Sorbo MC, Cento V, Di Maio VC, Howe AYM, Garcia F, Perno CF, Ceccherini-Silberstein F. 2018. Hepatitis C virus drug resistance associated substitutions and their clinical relevance: Update 2018. Drug Resist Updat. 37:17–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumana D 2015. Hepatitis C Virus: Structural Insights Into Protease Inhibitor Efficacy and Drug Resistance. University of Massachusetts Medical School. [Google Scholar]

- Soumana DI, Ali A, Schiffer CA. 2014. Structural analysis of asunaprevir resistance in HCV NS3/4A protease. ACS Chem Biol. 9(11):2485–2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumana DI, Kurt Yilmaz N, Ali A, Prachanronarong KL, Schiffer CA. 2016. Molecular and Dynamic Mechanism Underlying Drug Resistance in Genotype 3 Hepatitis C NS3/4A Protease. J Am Chem Soc. 138(36):11850–11859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumana DI, Kurt Yilmaz N, Prachanronarong KL, Aydin C, Ali A, Schiffer CA. 2016. Structural and Thermodynamic Effects of Macrocyclization in HCV NS3/4A Inhibitor MK-5172. ACS Chem Biol. 11(4):900–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkuhler C, Biasiol G, Brunetti M, Urbani A, Koch U, Cortese R, Pessi A, De Francesco R. 1998. Product inhibition of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. Biochemistry. 37(25):8899–8905. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summa V, Ludmerer SW, McCauley JA, Fandozzi C, Burlein C, Claudio G, Coleman PJ, Dimuzio JM, Ferrara M, Di Filippo M et al. 2012. MK-5172, a selective inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3/4a protease with broad activity across genotypes and resistant variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 56(8):4161–4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The MathWorks, Inc. 2014. MATLAB and Toolboxes Release 2014b Natick, Massachusetts, United States: The MathWorks, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Arasappan A, Bennett F, Chase R, Feld B, Guo Z, Hart A, Madison V, Malcolm B, Pichardo J et al. 2010. Preclinical characterization of the antiviral activity of SCH 900518 (narlaprevir), a novel mechanism-based inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 54(6):2365–2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Bogen S, Chase R, Girijavallabhan V, Guo Z, Njoroge FG, Prongay A, Saksena A, Skelton A, Xia E et al. 2008. Characterization of resistance mutations against HCV ketoamide protease inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 77(3):177–185. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Chase R, Skelton A, Chen T, Wright-Minogue J, Malcolm BA. 2006. Identification and analysis of fitness of resistance mutations against the HCV protease inhibitor SCH 503034. Antiviral Res. 70(2):28–38. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Geng L, Chen BZ, Ji M. 2014. Computational study on the molecular mechanisms of drug resistance of Narlaprevir due to V36M, R155K, V36M+R155K, T54A, and A156T mutations of HCV NS3/4A protease. Biochem Cell Biol. 92(5):357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2014. Hepatitis C Fact Sheet No. 164. [accessed 2014 April 23, 2014]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/enl.

- Xue W, Ban Y, Liu H, Yao X. 2014. Computational study on the drug resistance mechanism against HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors vaniprevir and MK-5172 by the combination use of molecular dynamics simulation, residue interaction network, and substrate envelope analysis. J Chem Inf Model. 54(2):621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Wang M, Jin X, Liu H, Yao X. 2012. Understanding the structural and energetic basis of inhibitor and substrate bound to the full-length NS3/4A: insights from molecular dynamics simulation, binding free energy calculation and network analysis. Mol Biosyst 8(10):2753–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao N, Reichert P, Taremi SS, Prosise WW, Weber PC. 1999. Molecular views of viral polyprotein processing revealed by the crystal structure of the hepatitis C virus bifunctional protease-helicase. Structure. 7(11):1353–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]