Highlights

-

•

Renal cell carcinoma affecting the pediatric population is extremely rare.

-

•

Papillary variant of the pediatric renal cell carcinoma is the most common type.

-

•

The prognosis of childhood renal cell carcinoma is poorer than that of the general population.

-

•

Majority of children with renal cell carcinoma have metastasis at diagnosis.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, Papillary, Child

Abstract

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for less than 0.3% of all tumours occurring in children and adolescents and it also affects 2.6% of all renal tumours for the pediatriac population. The aim of this report is to present the case of a 13-year old girl with metastatic papillary RCC and to review the literature mainly on treatment modalities and prognosis of children and adolescents with RCC.

Presentation of case

The case of a 13-year old girl is presented. The girl presented with a painless abdominal mass in the right side for three months. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a heterogeneous mass of 15 cm in diameter with metastasis to the liver. Also CT scan of the abdomen and lungs revealed metastasis to the liver and lungs. She underwent radical right nephrectomy.

Discussion

Pediatric RCC is an aggressive malignancy and some series have reported a 50% incidence of metastasis at the point of initial diagnosis similar to our patient who had metastasis to both lungs and liver at the time of initial diagnosis. Over 50% of metastasis of RCC in the pediatric population occurs in the lungs and liver.

Conclusion

RCC in children is extremely rare with no known specific treatment regimen. Early diagnosis when the tumour is still confined to the kidney provides better clinical outcomes since radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy have not been found to improve the prognosis.

1. Introduction

RCC accounts for less than 0.3% of all tumours occurring in children and adolescents. It also accounts for 2.6% of all renal tumours in the pediatric population [1]. Studies have shown that, a large proportion of pediatric RCC is associated with translocation of chromosome Xp11.2 leading to fusion of gene TFE3 [2]. There is no specific treatment regimen for pediatric RCC because of its rarity in the general population. For that reason, surgery remains the mainstay treatment with better prognosis for patients with stage I [3]. Pediatric RCC has similar signs and symptoms with that seen in adults which include abdominal pain, abdominal mass and haematuria (micro and macro) [[4], [5], [6]]. The case of a 13-year old girl with a metastatic papillary RCC is presented in this work including review of the literature focusing on treatment and prognosis. The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria 2018 [7].

2. Presentation of a case

A 13-year old girl presented with progressive painless abdominal distention mostly in the right flank region for a period of three months. She had no complaints of blood in urine, fever and history of trauma. Neither there was no information regarding family history of cancer and renal syndromes predisposing to developing renal cancer. Additionally, she was reported to have no history of using any medication in the past and without any family history of the presenting illness. On physical examination, she was ill-looking, wasted and pale neither with jaundice nor constipation. Laboratory investigation showed haemoglobin level 9.6 g/dl (11.5–16.5), leucocyte count 5.07 × 109 /L (4.00–11.00), platelet count 278 × 109 /L (150–500), and erythrocyte count 4.53 × 1012 /L (3.8–5.8). Electrolyte analysis revealed sodium 133.9 mmol/L (136.0–145.0), potassium 3.82 mmol/L (3.5–5.1), calcium 2.15 mmol/L (2.1–2.6), and phosphate 1.44 mmol/L (0.87–1.45). The renal function tests showed urea 2.7 mmol/L (0.0–8.3) and creatinine 41.0 micromol/L (44.0–80.0). Aspartate transaminase (AST) 16.1 U/L (2.0–32.0) and Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 4.8 U/L (2.0–33.0).

Ultrasound revealed undefined margins of right kidney but the left kidney was normal in size with mild hydronephrosis and there was a homogeneous mass in the right lobe of the liver which measured 4 × 3 cm. All other intra-abdominal organs were normal. Plain chest x-ray revealed micronodular infiltrates bilaterally, enlarged hilum and normal heart.

Contrast Enhanced Computerized Tomography (CECT) scan of the genitourinary system revealed a large and well defined heterogeneously enhancing mass which was replacing the right kidney with calcification and necrosis. There were feeding and draining vessels in the inferior border draining into the inferior vena cava (IVC). The mass measured 15 × 10.2 cm in cross section and 15.6 cm in cranial-caudal diameters. There were bilateral pulmonary nodules, hilar and subcarina lymphadenopathy indicating presence of lung metastasis. Also there was a non-enhancing hypodense hepatic mass involving the right lobe which measured 2.8 × 2.5 cm and para-aortic lymph nodes were not enlarged without ascites. The left kidney was normal as well as the ureters and urinary bladder were also normal.

The patient was evaluated by a team of oncologists and surgeons and a clinical stage IV was given (cT4N1M1). Radical nephrectomy was performed by a urologic surgeon in assistance of a resident. The procedure also included ipsilateral adrenal gland, Gerota fascia and omental lymph nodes dissection. There was no seeding tumour in the renal vein and inferior vena cava. Macroscopically, the tumour was multinodular and had distorted the normal gross appearance of the kidney (Fig. 1). The cut-surface of the involved kidney showed a necrotic tumour occupying the whole renal parenchyma. However, the capsule was not infiltrated by the mass. Microscopically, the tumour was solid with a papillary growth pattern composed of hobnailed tumour cells which had abundant pale cytoplasm and small round nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli. Psammoma bodies were evident in some areas of the tumour (Fig. 2a–d). The diagnosis of papillary variant of RCC with grade 2 (moderately differentiated) was then histologically confirmed. On the 7th day of her postoperative she was discharged home on palliative therapy. One month later, she passed on after developing ascites which was also followed by respiratory failure.

Fig. 1.

Distorted morphology of the right kidney by the tumour with formation of nodules which appear to be pushing the capsule but without obvious infiltration.

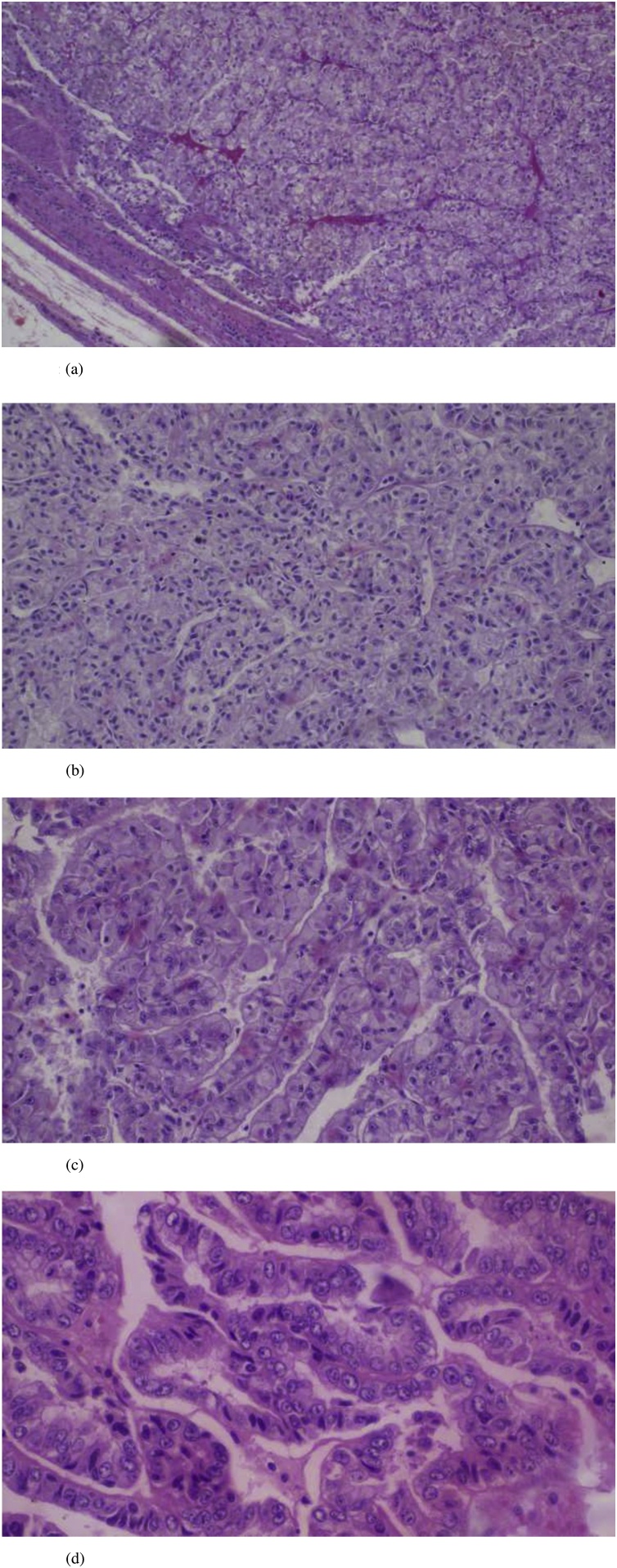

Fig. 2.

(a) Diffuse infiltration of the renal parenchyma by a solid tumour with formation of a pseudocapsule (H and E, ×40).

(b) proliferation of tumour cells which have pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei (H and E, ×100).

(c) The tumour masses are forming papillary pattern with fibrovascular cores (H and E, ×200).

(d) Marked pleomorphism of the tumour cells with vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (H and E, ×400).

3. Discussion

Because of having intrinsic resistance to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, RCC is treated successfully by surgery in both pediatrics and adults of course with favourable prognosis only in the early stage unlike advanced stage. Partial nephrectomy has been reported to be efficient in treating RCC when is localized for both children and adolescents provided that the surgical margins are free from the tumour. On the other hand, incomplete surgical resection of the tumour has been found to be associated with lowering of the overall survival of the patients by 10% [8]. Ramphal et al reported that all patients with free surgical margins after being treated with surgery alone remain longer free of the disease compared to those who have adjuvant chemotherapy or immunotherapy, hence, making their therapeutic role in managing pediatric RCC to be uncertain [2].

In another study done by Tsai et al it was reported that, there is no difference in survival between stage I pediatric patients with RCC who receive nephrectomy alone and those who receive nephrectomy together with adjuvant radiochemotherapy [9]. Abelardo et al also reported that both chemotherapy and radiation therapy have no significant role in improving the prognosis of RCC in either adults or pediatric patients with metastatic or residual RCC regardless of the histologic type [3]. Furthermore, Lam et al reported that the 10-year overall survival of pediatric patients with RCC treated by partial nephrectomy was good compared to those who underwent simple or radical nephrectomy [10].

Unlike stage I patients with RCC, most of the patients with stage II and III are treated with adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy in addition to surgery. Immunotherapy consisting of either interferon or interleukin has shown to have limited improvement of prognosis in treating selected adults with both advanced stage and high-grade RCC. The therapeutic effect of immunotherapy in children is even more limited compared to adults [2,11]. Those with stage IV disease are also good candidates for immunotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in addition to surgery.

The role of lymph node dissection during nephrectomy has a limited prognostic value. In a study done by Motzer and colleagues it was noted that, the disease-free survival (DFS) among children with positive dissected lymph nodes was 72.4% and there was no difference for children with positive lymph nodes who used adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy compared to those who were only treated surgically [11].

The overall survival of RCC in the pediatric population decreases significantly with advancing of the disease ranging from 92.4% to 13.9% with average overall survival of about 63% [12]. Different prognostic factors for RCC in children and adolescents have been reported. Tumour stage provides better prognosis compared to all other prognostic factors. Other prognostic factors such as age, tumour size, symptom duration, histological type, cellular pattern, pseudocapsule formation, vascular invasion, general performance status, tumour grade and tumour rupture have been reported to have varying prognostic roles [2,4,11,13].

Pediatric RCC is an aggressive malignancy and some series have reported a 50% incidence of metastasis at the point of initial diagnosis similar to our patient who had metastasis to both lungs and liver at the time of initial diagnosis [14]. Over 50% of metastasis of RCC in the pediatric population occurs in the lungs and liver. Other sites for metastasis of RCC include up to 42% and 15% to the bones and bladder, brain or pleura respectively [15]. Most of cancer-specific deaths and local recurrences have been reported to occur frequently within the first two years of diagnosis although late recurrences have also been reported to occur [14]. This also explains the fact that pediatric RCC is an aggressive tumour.

The case described in this paper indicates the importance of clinical suspicion of RCC among children who present with abdominal masses. This helps in ruling out other pathologies which would also have similar clinical presentation like that of RCC. Lack of specific clinical characteristics for pediatric RCC contributes greatly to delay of diagnosis and therefore worsening the outcomes of the patients.

4. Conclusion

Clinical suspicion of RCC in children aged more than 5 years presenting clinically with abdominal mass, pain in the flank region and painless haematuria could aide in making early diagnosis of the disease. This is because surgical resection of the tumour at early stage (stage I) carries better prognosis. This is of utmost importance for the treatment of pediatric RCC cases in whom choices of treatment modalities are limited due to lack of evidence from large clinical trials caused by rarity of availability of the cases.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sources of funding

The work did not receive fund from any source.

Ethical approval

There was exemption of ethical clearance.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

JJY: Organized and wrote the first draft, NB: Collected the necessary information concerning the patient including performing surgery, AM: Wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript critically and each author agree to take responsibility for the intellectual contents of the paper.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

James J Yahaya is the Guarantor of the work.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the team of urologists and pediatric oncologists for their support that was necessary for the writing of this work.

References

- 1.Ries L.A.G., Smith M.A., Gurney J.G., editors. Vol. 3. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1999. pp. 79–90. (Cancer Incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995, SEER Program). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramphal R., Pappo A., Zielenska M., Grant R., Ngan B.Y. Pediatric renal cell carcinoma: clinical, pathologic, and molecular abnormalities associated with the members of the MiT transcription factor family. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006;126:349–364. doi: 10.1309/98YE9E442AR7LX2X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loya-Solis A., Alemán-Meza L., Canales-Martínez L.C., Franco-Márquez R., Rincón-Bahena A.A., Nuñez-Barragán K.M., Garza-Guajardo R., Antonio Ponce-Camacho M. Pediatric papillary renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney: a case report with review of the literature. Case Rep. Pathol. 2015;1:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2015/841237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdellah A., Selma K., Elamin M., Asmae T., Lamia R., Abderrahmane M., El Majjaoui S., Elkacemi H., Kebdani T., Benjaafar N. Renal cell carcinoma in children: case report and literature review. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015;20:1–4. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.84.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louati H., Jlidi S., Charieg A. Renal cell carcinoma in children: about two case report. Med. Surg. Urol. 2016;5:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratna M.D., Mital V.P. Renal cell carcinoma in a child. A case report. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 1984;27:245–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 Statement: Updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson D.C., Medary I., Finlay J.L., Herr H.W., Exelby P.R., La Quaglia M.P. Renal cell carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a retrospective survey for prognostic factors in 22 cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1996;31:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai H.L., Chin T.W., Chang J.W., Liu C.S., Wei C.F. Renal cell carcinoma in children and young adults. J. Chinese Med. Assoc. 2006;69:240–244. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam J.S., Shvarts O., Pantuck A.J. Changing concepts in the surgical management of renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2004;45:692–705. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer R.J., Nanus D.M., Russo P., Berg W.J. Renal cell carcinoma. Curr. Probl. Cancer. 1997;21:185–232. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(97)80007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silberstein J., Grabowski J., Saltzstein S.L., Kane C.J. Renal cell carcinoma in the pediatric population: results from the California cancer registry. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2009;52:237–241. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchiyama M., Iwafuchi M., Yagi M., Iinuma Y., Ohtaki M., Tomita Y., Hirota M., Kataoka S., Asami K. Treatment of childhood renal cell carcinoma with lymph node metastasis: two cases and a review of literature. J. Surg. Oncol. 2000;75:266–269. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200012)75:4<266::aid-jso8>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Indolfi P., Terenziani M., Casale F., Carli M., Bisogno G., Schiavetti A., Mancini A., Rondelli R., Pession A., Jenkner A., Pierani P., Tamaro P., De Bernardi B., Ferrari A., Santoro N., Giuliano M., Cecchetto G., Piva L., Surico G., Di Tullio M.T. Renal cell carcinoma in children: a clinicopathologic study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:530–535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carcao M.D., Taylor G.P., Greenberg M.L., Bernstein M.L., Champagne M., Hershon L., Baruchel S. Renal-cell carcinoma in children: a different disorder from its adult counterpart. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 1998;31:153–158. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199809)31:3<153::aid-mpo5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]