Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease is known as a major cause of chronic kidney disease and end stage renal disease. Polysulfides, a class of chemical agents with a chain of sulfur atoms, are found to confer renal protective effects in acute kidney injury. However, whether a polysulfide donor, sodium tetrasulfide (Na2S4), confers protective effects against diabetic nephropathy remains unclear. Our results showed that Na2S4 treatment ameliorated renal dysfunctional and histological damage in diabetic kidneys through inhibiting the overproduction of inflammation cytokine and reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as attenuating renal fibrosis and renal cell apoptosis. Additionally, the upregulated phosphorylation and acetylation levels of p65 nuclear factor κB (p65 NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in diabetic nephropathy were abrogated by Na2S4 in a sirtuin-1 (SIRT1)-dependent manner. In renal tubular epithelial cells, Na2S4 directly sulfhydrated SIRT1 at two conserved CXXC domains (Cys371/374; Cys395/398), then induced dephosphorylation and deacetylation of its targeted proteins including p65 NF-κB and STAT3, thereby reducing high glucose (HG)-caused oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, inflammation response and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) progression. Most importantly, inactivation of SIRT1 by a specific inhibitor EX-527, small interfering RNA (siRNA), a de-sulfhydration reagent dithiothreitol (DTT), or mutation of Cys371/374 and Cys395/398 sites at SIRT1 abolished the protective effects of Na2S4 on diabetic kidney insulting. These results reveal that polysulfides may attenuate diabetic renal lesions via inactivation of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 phosphorylation/acetylation through sulfhydrating SIRT1.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Reactive oxygen species, Polysulfides, Hydrogen sulfide, SIRT1

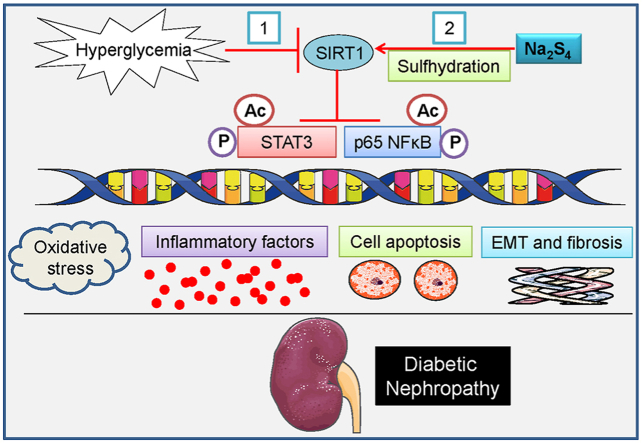

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease is taken as a leading cause of chronic kidney disease and end stage kidney disease [1], which is reflected by proteinuria, mesangial matrix overproduction, renal hypertrophy, and fibrosis [2]. Studies have shown that several factors are major contributors to the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy, including inflammation, oxidative stress, overproduction of transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF-β1) expression, and metabolic alterations [3,4]. In spite of the advancing knowledge in diabetic renal pathologies over the years, diabetic kidney disease remains a leading cause of people mortality and morbidity [5]. As a result, there is an urgent demand to identify novel drugs for the management of diabetic kidney disease especially considering the increasing prevalence of diabetes and obesity.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is recognized as a gaseous signaling mediator that plays a critical role in the modulation of various cellular processes under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions [6,7]. Sulfane sulfur, a sulfur atom with six valence electrons with no charge, is capable of binding reversibly to other sulfur atoms to yield persulfides (R–SSH) or polysulfides (R-S-Sn-S-R) [8]. H2S-related reactive sulfane sulfur compounds are composed of persulfide (R–SSH), organic polysulfides (R-Sn-SH or R-S-Sn-S-R, n ≥ 2), inorganic hydrogen polysulfides (H2Sn, n ≥ 2) and protein-bound elemental sulfur (S8) [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. Of those sulfane sulfur compounds, polysulfides are produced endogenously by oxidation of H2S, and they therefore can be served as a sink of H2S [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. Polysulfides are a class of chemicals containing variable number of sulfur atoms [18]. Organic polysulfides have the common formula of R-Sn-R, in which R may be an alkyl or aryl group [19]. In different types of polysulfides, inorganic sodium polysulfides (Na2Sn) is commonly applied to examine the roles of polysulfides since it solely provides Sn2− in aqueous solution, thus allowing them to mimic endogenously produced polysulfides [19]. Similar to H2S, polysulfides can be generated in mammal systems through either non-enzymatic pathways or enzymatic pathways [20,21]. Importantly, many of biological effects of H2S may in fact be attributed to the formation of polysulfides [[22], [23], [24]].

It has been demonstrated that polysulfides are potential regulators in mammalian physiology, such as regulating the activity of ion channels, serving as tumor suppressor, and modulating the activities of protein kinases [10,15,16,25,26]. Koike and colleagues have found that Na2S4, a polysulfide donor, protects neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells from t-buthylhydroperoxide-induced cytotoxicity, this effect may be ascribed to the suppression of oxidative damage [27]. Na2S4 treatment promotes neuroblastoma cell differentiation by accelerating calcium influx [28]. In rat peritoneal mast cells, Na2S4 acts as a stimulator for extracellular and intracellular Ca (2+) release via a crosstalk between H2S and nitric oxide (NO) [29]. The atmospheric electrophile 1,4-naphthoquinone (1,4-NQ)-induced heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) expression and heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) activation in A431 cells are blocked by pretreatment with Na2S2 and Na2S4, suggesting that polysulfides could diminish the reactivity of 1,4-NQ by forming sulfur adducts [30]. Moreover, exposure of primary mouse hepatocytes to Na2S4 significantly inhibits 1,4-NQ-evoked cell death and S-arylation of cellular proteins, and the protective effects of Na2S4 may be due to activation of the PTEN/Akt/CREB signaling pathway [31]. Cadmium, an environmental electrophile, is involved in mediating cellular signaling and toxicity through modifying protein nucleophiles. Incubation of primary mouse hepatocytes to cadmium promotes HSP70 and metallothionein (MT)-I/II expressions and subsequent hepatic cytotoxicity, while these effects are diminished in the presence of Na2S4 [32]. Na2S4 protects dopaminergic neurons from 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+)-induced cytotoxicity, and the neuroprotective effects of Na2S4 are mediated by enhancement of glutathione biosynthesis [33]. Polysulfide donors (Na2S2, Na2S3, Na2S4) are more effective than H2S in the modulation of K+ channel N-type inactivation by sulfhydration of mammalian Kv channels Kv1.4 and Kv3.4 [34]. The reactive sulfur species donor, Na2S4, induces the inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) through its Cys6 polysulfidation in RAW264.7 murine macrophage cells [35]. Very recently, polysulfide salts (Na2S2, Na2S3, Na2S4) are found to inhibit glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells through activating the ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels [36]. These extensive studies have confirmed that Na2S4 functions as sulfur-containing molecular species that might regulate various cellular events.

In recent years, H2S is a promising candidate for the management of diabetic renal disease via by attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation, inhibiting renin-angiotensin system activity and mesangial cell proliferation [4]. Mounting evidence suggests that H2S might represent an alternative therapeutic approach for diabetic nephropathy [37]. Given that polysulfides and persulfide-induced activation of signaling pathways might mediate many biological effects of H2S in mammalian systems, including renal system, it is not unexpected that polysulfide donors might also play an important role in renal protection under pathophysiological states. Recently, we have demonstrated that Na2S4 holds protective effects against cisplatin-elicited renal toxicity [19,38]. Our group has also demonstrated that Na2S4 ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity via repressing intracellular oxidative stress, a critical event involved in diabetic nephropathy [38]. However, the exact roles of polysulfides in diabetic nephropathy and the mechanisms involved are largely unknown. Thus, we explored the potential effects of polysulfides on diabetic nephropathy at both animal and cell levels, the involved downstream signaling pathways were also investigated.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents

A polysulfide donor Na2S4 was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies Dojindo (Kumamoto, Japan). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay kits were procured from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). d-glucose, D-mannitol, dithiothreitol (DTT), streptozotocin (STZ) and EX527 were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Click-iT™ Plus terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kits and Click-iT™ Plus EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) Alexa Fluor™ 488 imaging kits were procured from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Antibodies against p22phox, p47phox, TGF-β, α-SMA, E-cadherin, Bax, Bcl-2, cleaved-PARP, GAPDH, β-actin, F4/80, and the secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (CA. USA). The non-specific control small interfering RNA (siRNA), and SIRT1 siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (CA. USA). Antibodies against sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), phosphorylated and total p65 nuclear factor κB (p65 NF-κB), acetylated p65 NF-κB, and acetyllysine were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against phosphorylated and total signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), cleaved-caspase-3, NOX2, and pan-Cadherin were bought from Abcam (Cambridge, MA. USA). The specific primers were synthesized and provided by Integrated DNA Technologies Pte. Ltd. (Singapore).

2.2. Induction of diabetes in mice

All animal experiments were approved by Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee at National of University of Singapore. All experimental procedures in animals were also in compliance with the guidance of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animal published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication, 8th edition, 2011). Male C57BL/6 mice (InVivos, Singapore) aged at 8–10 weeks were used to produce diabetes by a single injection of STZ (i.p., 100 mg/kg) as we previously described [[39], [40], [41]]. All animals were caged in the SPF condition with free access to stand laboratory chow and tap water on a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycles. One week after injection of STZ, the mice with a fasting blood glucose level in the mouse tail vein blood more than 12 mM were considered to be diabetic [41]. After injection of STZ for 8 weeks, the mice in Na2S4 + Diabetes group and Na2S4 group were injected with Na2S4 (500 μg/kg/day) for the coming 4 weeks. The body weight in each mouse was weighted at the end of experiments before sacrificed.

2.3. Histology, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

For histological assessment of renal function, the renal tissues from mice were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 48 h. The kidney sections (5 μm) were dewaxed, hydrated, and then stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. The stained renal sections were visualized using a light microscope (Leica, Microsystems, Germany). The renal histological changes were assessed at least 6 randomly selected fields on the basis of tubular dilation and atrophy, brush border loss, cast formation, and the proportion of tubules in the external medulla field in accordance with previous studies [42]. The renal fibrosis was assessed in renal sections by Sirius red staining (Abcam, Cambridge, MA. USA). For renal immunohistochemistry, the kidney sections (5 μm) were probed with a primary antibody against F4/80 (a macrophage maker) overnight at 4 °C, and the sections were then subject to horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was employed to yield a brown reaction for immunohistochemical development. The immunohistochemical images were photographed under a light microscope (Leica, Microsystems, Germany). The renal sections for immunofluorescent staining were used to examine nitrotyrosine expressions. In brief, after blocking with 5% serum for 30 min, the renal sections were probed with the anti-nitrotyrosine antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by treatment of goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 antibody for 1 h at 37 °C. The immunofluorescence graphs were collected by using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

2.4. Analysis of renal function

The blood was collected to separate serum samples at the end of experiments. The serum levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine were quantified to evaluate renal function using commercial kits in compliance with the manufacturer's instructions (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) [43]. After reaction with the related agents, the absorbance for serum BUN was analyzed at 640 nm by a microplate reader. The optical density was read at 546 nm for serum creatinine measurement using a Varioskan Flash microplate reader (Waltham, MA. USA).

2.5. Apoptosis assay in renal tissues

The renal cell apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay as we previously reported [38]. Briefly, the sectioned kidneys were stained with fluorescein-linked TUNEL, and Hoechst staining was used to identify the cell nuclei. The TUNEL-positive renal cells were photographed using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

2.6. Cell culture and transfection

HK-2 cells (a human kidney tubular epithelial cell line) were cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium in supplementation with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After the cells achieved 80% confluence, the cells were passaged at a ratio of 1:3. HK-2 cells were incubated with normal d-glucose medium (NG, 5.5 mM) or high d-glucose medium (HG, 30 mM) for 48 h, respectively. Na2S4, EX-527 and DTT were pre-added individually to the culture medium at indicated concentrations before HG treatment. To study the involvement of SIRT1 in the Na2S4-mediated protective effect against diabetic nephropathy in vitro, HK-2 cells in the exponential phase of growth were plated in six-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/plate and cultured for 24 h. After that, transfection of scramble control and SIRT1 siRNA (50 nM) in HK-2 cells were carried out by using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The inhibition efficiency of siRNA was confirmed by Western blotting.

2.7. Cell viability and apoptosis

CCK-8 was applied to examine HK-2 cell viability. In short, after treatment, CCK-8 solution (10 μl) was added into the culture medium (100 μl) at the required wells at 37 °C for 2 h. After that, the optical density of each sample was analyzed at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Varioskan Flash, Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA. USA). Cell viability was expressed by calculating the ration of average optical density of treatment group/control group. In addition, after being treated, EdU incorporation assay was applied to determine the cell proliferation in keeping with the manufacturer's instructions. The EdU-positive cells were obtained with the aid of a fluorescence microscope (DMi 8; Leica, Microsystems, Germany). For determination of HK-2 cell apoptosis, TUNEL assay was utilized to obtain TUNEL-positive cells, and the cell apoptosis was simultaneously evaluated by a flow cytometry (Cytoflex LX, Beckman, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). LDH release assay was conducted by using LDH assay kits in line with the manufacturer's suggestions, and the optical density was measured at the absorbance of 450 nm using a microplate reader (Varioskan Flash, Waltham, Thermo Electron Corporation, MA. USA).

2.8. Quantitative real-time PCR

The mRNA expression levels of TGF-β1, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), E-cadherin, collagen I, and collagen III were determined by real-time PCR with the specific primers (Table S1 and Table S2) under ABI Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) as we previously depicted [41].

2.9. S-sulfhydration assay

S-sulfhydration of SIRT1 was measured by a tag-switch method [44,45]. In short, cells treated with Na2S4 were dissolved in HEN buffer (250 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, 1% NP-40). Cell lysates were incubated with a water-soluble methylsulfonyl benzothiazole (MSBT-A, 50 mM) at 37 °C for 1 h. After salt removal, the mixture was added into anti-SIRT1 antibody (2 μg) supplemented with protein A/G beads overnight. The beads were then suspended in biotin-linked cyanoacetate (20 mM) at 37 °C for 1 h under gentle shaking conditions. After centrifugation, biotinylated proteins were eluted by loading buffer (30 μL), and the samples were further detected by Western blotting. S-sulfhydrated SIRT1 expression was determined by using anti-biotin antibody, and the SIRT1 protein expressions were evaluated with anti-SIRT1 antibody.

2.10. Measurement of oxidative stress markers

The superoxide anion production in renal tissue sections and collected cells was detected by dihydroethidium (DHE, 10 μM) or 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, 10 μM) staining in a dark environment for 30 min at 37 °C. The color images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) and quantified using Image-Pro Plus analysis software. In addition, the contents of malondialdehyde (MDA), and activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH-Px) were assessed by using the corresponding commercial kits [46]. NAD(P)H oxidase activity was determined by enhanced lucigenin-derived chemiluminescence as our previous report [38].

2.11. Isolation of membrane proteins, western blotting and immunoprecipitation

The whole cell proteins and the membrane proteins were isolated using radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer or a plasma membrane and cytosol extraction kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), respectively. The same amount of proteins in each sample was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels, and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were probed with various primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation of horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies. Western blotting bands were observed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) solution. The target protein expressions were normalized to the protein level of house-keeping gene expressions from the same PVDF membrane. For evaluation of SIRT1 acetylation, the immunoprecipitation analysis was used. In brief, the cells or renal tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer, the cell lysates were then centrifuged at 12 000×g for 15 min and the soluble fraction was obtained. Subsequently, the equal amount of soluble fraction was incubated with anti-SIRT1 antibody and then bounded with protein A/G agarose beads to yield immune complexes. Eventually, bound proteins were eluted by boiling with loading buffer and determined by Western blotting.

2.12. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The renal tissues were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 12 000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatants were obtained and the protein contents in each sample were quantified by Bradford colorimetric protein assay kit (Rockford, IL. USA). The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and VCAM-1 were in renal tissue samples were determined by commercial ELISA kits (BOSTER, Wuhan, China) in keeping with the manufacturer's protocols. At the end of experiments, the color reactions were measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Varioskan Flash, Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA. USA). The results were relative to the protein contents and expressed as pg/mg in each sample.

2.13. Statistical analyses

In the present study, the results were calculated as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS 19.0 statistical software (Chicago, IL, USA). Differences were analyzed by t-test between two groups and analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test was used for multiple group comparisons. The standard was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Na2S4 attenuates HG-induced apoptosis in HK-2 cells

It has already been demonstrated that HG stimulation could decrease cell viability and trigger cell death in human renal tubular epithelial cells [47,48]. Moreover, we previously reported that a polysulfide donor Na2S4 mitigated cisplatin-caused renal tubular cell apoptosis [38]. However, the roles of Na2S4 in HG-induced cell apoptosis in HK-2 cells remain largely unknown. Therefore, we evaluated the direct effects of Na2S4 on HG-evoked renal tubular cell injury by performing in vitro experiments in HK-2 cells. To study the effect of osmolality, D-mannitol was used as a hyperosmolar control in the present study (5.5 mM d-glucose + 24.5 mM D-mannitol) [49,50]. In consistence with the previous reports [[49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54]], cell viability was significantly reduced by HG (30 mM) incubation, but not by hyperosmolar D-mannitol treatment, when compared with control cells. These data suggest that HK-2 cell injury was considered as an effect from glucotoxicity, rather than from hyperglycemia‐induced hyperosmolarity (Fig. S1).

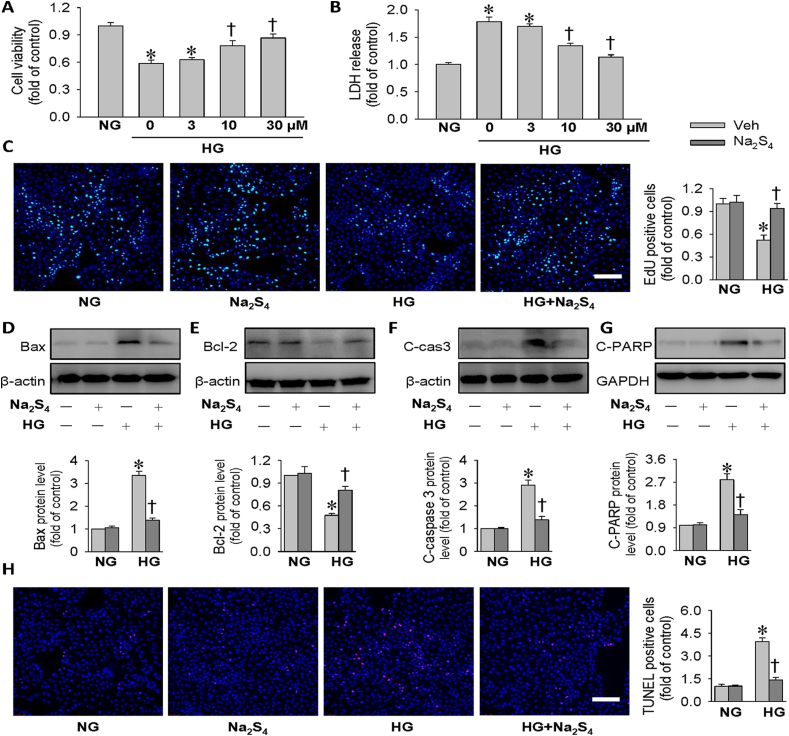

Then, the concentration-dependent effects of Na2S4 were also observed in HK-2 cells. Na2S4 treatment had no obvious effect on the cell proliferation of HK-2 cells at the concentrations from 3 μM to 100 μM in comparison with the control cells. However, Na2S4 decreased the cell viability by around 15% and 50% at the doses of 200 μM and 300 μM, respectively (Fig. S2). These results suggested that the safe dose of Na2S4 with no cellular toxicity on HK-2 cells was within 100 μM. To further explore the actions of Na2S4 on HG-triggered HK-2 cell apoptosis, we evaluated the apoptotic response in HG-incubated HK-2 cells in the presence or absence of Na2S4. As expected, pretreatment with Na2S4 dose-dependently restored the decreased cell viability induced by HG, whereas Na2S4 treatment (30 μM) almost completely abolished HG-caused cell viability decline (Fig. 1A). This was further reflected by LDH release assay as shown in Fig. 1B. Therefore, Na2S4 was selected as a concentration of 30 μM for subsequent in vitro studies. The cell viability was also evaluated by EdU staining. HG incubation significantly reduced the EdU-positive HK-2 cells (Fig. 1C). Conversely, Na2S4 obviously enhanced cell viability compared with the cells treated with HG (Fig. 1C). The data indicated that Na2S4 could lessen HG-induced suppressive effects on HK-2 cell proliferation (Fig. 1C). As illustrated in Fig. 1D–G, the pro-apoptotic protein expression levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved-PARP were strikingly increased, whereas the anti-apoptotic protein level of Bcl-2 was markedly downregulated after HG stimulation. However, Na2S4 treatment largely prevented HG-caused upregulations of pro-apoptotic protein expression levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved-PARP, while reversed HG-induced Bcl-2 downregulation (Fig. 1D–G). TUNEL assay also demonstrated that Na2S4 treatment remarkably suppressed HG-induced HK-2 cell apoptosis as Na2S4 pre-treated cells had a fewer proportion of apoptotic cells when compared to HG alone treated cells (Fig. 1H). Finally, the antagonistic effects of Na2S4 on HG-triggered HK-2 cell apoptosis were also confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. S3). Taken together, these results indicated that Na2S4 protected HK-2 cells from cell apoptosis under HG circumstances.

Fig. 1.

Effects of Na2S4 on cell viability and apoptosis in HK-2 cells. (A) HK-2 cells were pre-incubated with Na2S4 (0, 3, 10, 30 μM) for 30 min, and then challenged by or HG (30 mM) for 48 h. Results showed that Na2S4 dose-dependently prevented HG-induced HK-2 cell viability decline. (B) HK-2 cells were pre-incubated with Na2S4 (0, 3, 10, 30 μM) for 30 min, and then challenged by or HG (30 mM) for 48 h. Effects of various doses of Na2S4 (0, 3, 10, 30 μM) on HG-induced LDH release. (C) HK-2 cells were pre-incubated with Na2S4 (30 μM) for 30 min, and then challenged by or HG (30 mM) for 48 h. EdU staining showed that Na2S4 (30 μM) attenuated HG-induced inhibition of HK-2 cell viability. (D–G) Representative blot images and quantitative analysis of Bax, Bcl-2, cleaved-caspase3 (C-cas3), and cleaved PARP (C-PARP). (H) Effects of Na2S4 (30 μM) on HG-induced cell apoptosis determined by TUNEL assay. *P < 0.05 vs. NG. †P < 0.05 vs. 0 μM or Vehicle (Veh). Scale bar = 200 μm n = 4 to 6.

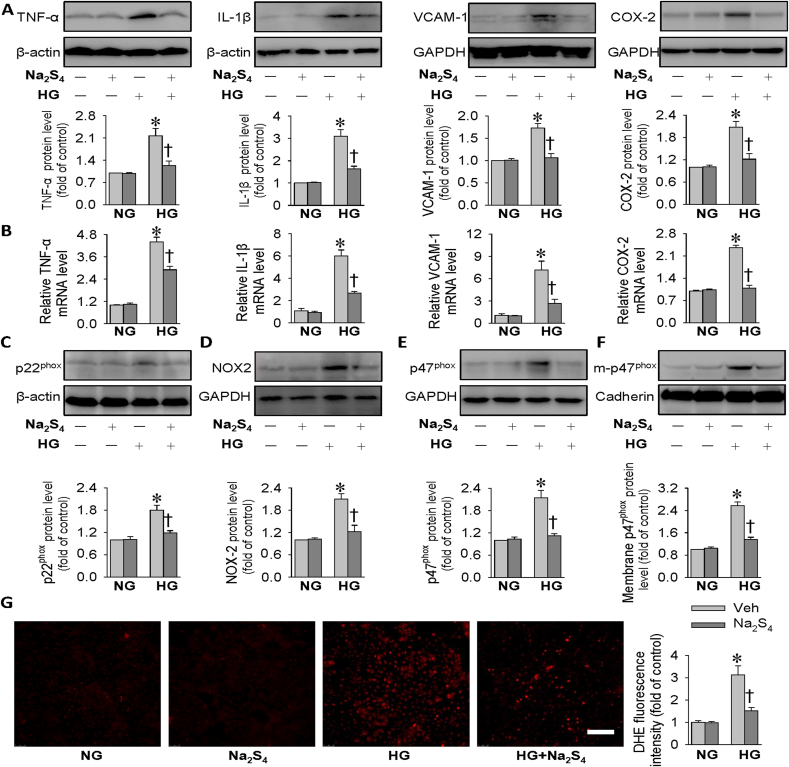

3.2. Na2S4 attenuates HG-induced inflammation response and oxidative damage in HK-2 cells

Aberrant inflammation response and oxidative injury are driving forces for the pathologies of diabetic kidney disease [55]. Next, we determined whether Na2S4 could ameliorate HG-evoked oxidative stress and inflammation response in HK-2 cells. The protein levels of inflammatory factor markers, including TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2, were remarkably enhanced when HK-2 cells were challenged by HG, effects that were strikingly blocked by Na2S4 (Fig. 2A). The anti-inflammatory effects of Na2S4 on HG-stimulated HK-2 cells were also ascertained by measurement of mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2 using RT-PCR (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of Na2S4 on inflammation response and oxidative stress in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were pre-incubated with Na2S4 (30 μM) for 30 min, and then challenged by or HG (30 mM) for 48 h. (A) Representative blot images and quantitative analysis of TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2 showing that Na2S4 (30 μM) mitigated HG-induced inflammation response. (B) Relative mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2. (C–F) Representative blot images and quantitative analysis of p22phox, NOX2, p47phox and membrane p47phox showing that Na2S4 (30 μM) mitigated HG-induced oxidative stress. (G) Effects of Na2S4 (30 μM) on HG-induced cell ROS production determined by DHE fluorescence staining. Scale bar = 200 μm *P < 0.05 vs. NG. †P < 0.05 vs. Vehicle (Veh). n = 4 to 6.

It is widely accepted that the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy may be closely associated with dysregulated oxidative stress [56]. Importantly, the enhanced oxidative stress is predominantly regulated by various NADPH oxidases (NOX) isoforms, including p22phox, p47phox and NOX2 in diabetic nephropathy [57]. The membrane translocation of p47phox is a fundamental event for the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in both diabetic kidney disease and acute kidney injury [58,59]. In comparison with NG-treated cells, the protein expression levels of p22phox, p47phox and NOX2 were augmented in HK-2 cells upon exposure to HG, and this effect was counteracted by preconditioning with Na2S4 (Fig. 2C–E). Besides, the upregulated p47phox protein expression in the plasma membrane caused by HG was obviously reduced when the cells were pretreated with Na2S4 (Fig. 2F). Upon exposure to HG, the massive production of intracellular ROS was substantially abrogated by preconditioning with Na2S4 in HK-2 cells (Fig. 2G). Altogether, these results suggest that the protective effects of Na2S4 against diabetic kidney disease are at least partially mediated by inhibition of inflammation and ROS overproduction.

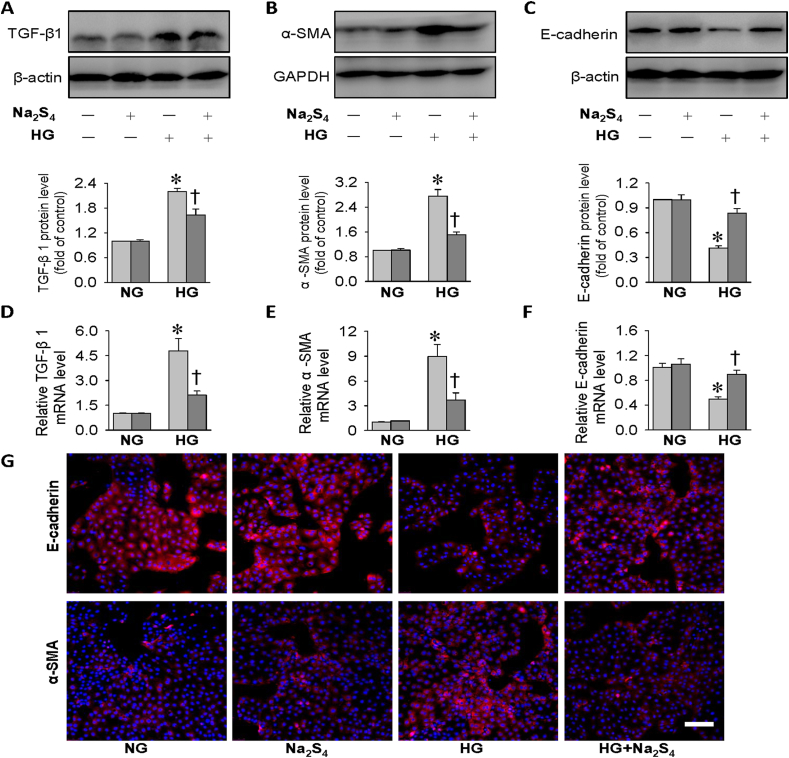

3.3. Na2S4 attenuates HG-induced HK-2 cell fibrosis

The fibrosis in the kidneys is a common pathway in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease, and TGF-β1 may be a central player in the processes of kidney fibrosis via promoting extracellular matrix (ECM) expansion under diabetic conditions [60,61]. A myriad of evidence demonstrates a role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in the development and progression of diabetic renal fibrosis [62]. The process of EMT is accompanied by downregulations of epithelial indicators, such as E-cadherin, and upregulations of mesenchymal phenotype markers, such as α-SMA [63,64]. In light of Na2S4-mediated beneficial effects in HG-challenged HK-2 cells as mentioned above, we wanted to determine whether Na2S4 altered HG-induced EMT development and TGF-β1 signaling activation in HK-2 cells. Compared with control cells, more TGF-β1 and α-SMA protein expression levels, but less E-cadherin protein expressions, were detected in HG-incubated HK-2 cells (Fig. 3A–C). However, pretreatment with Na2S4 substantially reversed these abnormalities under HG conditions (Fig. 3A–C). In similarity, the abnormal mRNA levels of TGF-β1, α-SMA and E-cadherin in HG-challenged HK-2 cells were noticeably corrected by Na2S4 (Fig. 3D–F). Immunofluorescence results further confirmed that Na2S4 treatment diminished HG-induced EMT process in HK-2 cells, as manifested by lower α-SMA immuno-positive signals and higher E-cadherin immuno-positive signals (Fig. 3G). The data clearly demonstrated that Na2S4 might ameliorate diabetic renal fibrosis by inhibiting EMT progression.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Na2S4 on EMT process in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were pre-incubated with Na2S4 (30 μM) for 30 min, and then challenged by or HG (30 mM) for 48 h. (A–C) Representative blots and quantitative analysis of TGF-β1, α-SMA, E-cadherin showing that Na2S4 (30 μM) mitigated HG-induced fibrosis in HK-2 cells. (D–F) Relative mRNA levels of TGF-β1, α-SMA, E-cadherin. (G) Immunofluorescence staining for E-cadherin or α-SMA. Scale bar = 200 μm *P < 0.05 vs. NG. †P < 0.05 vs. Vehicle (Veh). n = 4 to 6.

3.4. Induction of SIRT1 mediates the protective roles of Na2S4 in HK-2 cells

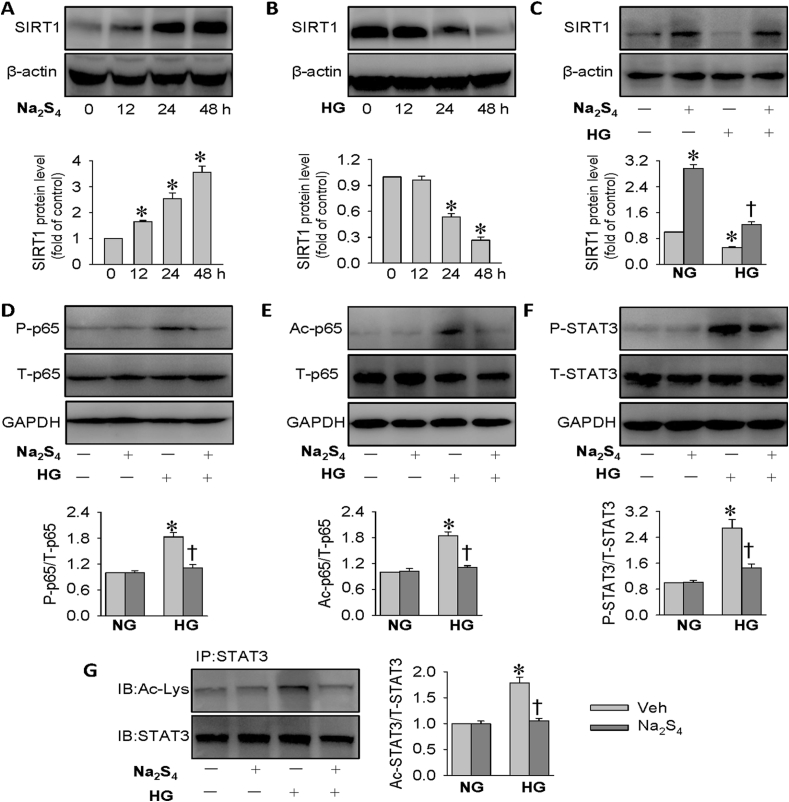

In the kidneys, the most widely studied SIRT is SIRT1, which exerts renal cytoprotective effects via suppressing cell apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress and fibrosis [65,66]. Activation of SIRT1 benefits renal damage and delays renal fibrogenesis in diabetes, indicating that SIRT1 may serve as a therapeutic target for diabetic kidney disease [67]. More importantly, induction of SIRT1 by H2S confers a protective role against diabetic kidney disease through inhibiting oxidative stress [68]. Thus, it is worth investigating whether upregulation of SIRT1 is responsible for the therapeutic effects of Na2S4 in the context of diabetes. A time-course study showed that Na2S4 treatment obviously stimulated SIRT1 protein expressions in HK-2 cells (Fig. 4A). By contrast, the protein expressions of SIRT1 were remarkably decreased when HK-2 cells were challenged by HG at different time points (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, the downregulated SIRT1 protein levels in HG-exposed HK-2 cells were restored to near or even higher than baseline by Na2S4 treatment, as demonstrated by Western blot (Fig. 4C). These above results indicated that SIRT1 might mediate the protective actions of Na2S4 on HG-induced injury in HK-2 cells.

Fig. 4.

Effects of Na2S4 on SIRT1, phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 NF-κB and STAT3. (A) Effects of Na2S4 (30 μM) on SIRT1 protein levels. (B) Effects of HG (30 mM) on SIRT1 protein levels. (C) HK-2 cells were pre-incubated with Na2S4 (30 μM) for 30 min, and then challenged by or HG (30 mM) for 48 h. Pretreatment with Na2S4 (30 μM) reversed HG-triggered downregulation of SIRT1 protein expressions. (D–G) Effects of Na2S4 (30 μM) on the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 h or NG. †P < 0.05 vs. Vehicle (Veh). n = 4 to 6.

SIRT1 is reported to protect against diabetic kidney disease via deacetylating its targeted proteins, such as STAT3 and p65 NF-κB, two critical genes engaged in diabetic nephropathy [69,70]. Conditional gene deletion of SIRT1 in podocytes contributes more kidney injury in diabetic mice, and this effect may be dependent on the higher acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 [70]. Excepting from the elevated p65 NF-κB and STAT3 acetylation levels in diabetic kidneys [70], the enhanced phosphorylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 are also observed in diabetic kidney damage [71,72]. Interestingly, the phosphorylated p65 NF-κB and STAT3 levels are also strictly regulated by SIRT1 [73,74]. To confirm the possible involvement of the SIRT1 signaling pathways, we investigated the effects of Na2S4 on the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3. The levels of p65 NF-κB phosphorylation and acetylation were constitutively higher in HK-2 cells challenged by HG, and this effect was dampened by application of Na2S4 (Fig. 4D–E). In parallel to this, Na2S4 pretreatment alleviated HG-induced upregulations of STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation in HK-2 cells (Fig. 4F–G). Collectively, the molecular mechanism by which Na2S4 exhibits renoprotective effects appears to involve SIRT1-mediated inhibition of p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation.

3.5. Blockade of SIRT1 abolishes the beneficial effects of Na2S4

To further verify the implication of the SIRT1 signaling cascade in Na2S4-mediated effects in HK-2 cells, the SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 was used. Treatment with EX527, a known specific SIRT1 inhibitor, reversed the actions of Na2S4 on the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB in HG-stimulated HK-2 cells (Fig. S4A-B). In the presence of EX527, the suppressive effects of Na2S4 on STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation levels were also diminished in the context of HG (Fig. S4C-D). Of note, the antagonistic effects of Na2S4 on HG-caused HK-2 cell apoptosis, inflammation response, oxidative injury, and fibrosis were blocked by EX527-mediated SIRT1 inhibition, as reflected by measurement of cleaved-PARP, COX-2, p47phox and TGF-β1 protein expressions (Fig. S4E). As shown in Fig. S5 and Fig. S6, Na2S4 caused a marked decrease of cell apoptosis and oxidative damage in HG-incubated HK-2 cells, with such effects being partially abolished by the addition of EX527. Although EX-527 is a potent and selective SIRT1 inhibitor, it also inhibits SIRT2/3 to a lesser extent [[75], [76], [77], [78]]. Since SIRT3 plays a central role in mitochondrial bioenergetics and antioxidant functions induced by sulfide/polysulfides [[79], [80], [81], [82]], it is necessary to differentiate the effect of Na2S4 was from SIRT1 or from SIRT3. Consistent with the results with EX-527, reduction of SIRT1 with SIRT1 siRNA prevented the renal effects of Na2S4 on HK-2 cells (Fig. S7). The present results indicated that Na2S4 may specifically act on SIRT1 to circumvent HG-provoked injury in HK-2 cells.

3.6. Sulfhydrated SIRT1 contributes to the protective role of Na2S4 in HK-2 cells

Sulfhydration, termed as the addition of one sulfhydryl to the cysteine residue of target proteins and the subsequent generation of a persulfide group, is an important post-translational modification by H2S or polysulfides in eukaryotic cells [83]. Actually, it is recently established that H2S elicits SIRT1 sulfhydration at its two conserved zinc finger domains (C371/374; C395/398), along with increased its zinc ion binding activity to stabilize the alpha-helix structure, thereby reducing atherosclerotic plaque formation [84]. Subsequently, we examined whether polysulfides altered SIRT1 sulfhydration in HK-2 cells. We found that there was a stronger sulfhydration of SIRT1 in HK-2 cells after Na2S4 incubation (Fig. S8A). The upregulated sulfhydrated SIRT1 by Na2S4 was reduced by DTT (a de-sulfhydration reagent) (Fig. S8B). DTT pretreatment removed protein sulfhydration of SIRT1 and significantly attenuated the capability of Na2S4 to normalize HG-induced p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation in HK-2 cells (Fig. S9A-D). Notably, continuous treatment with DTT blocked the inhibition of HK-2 cell apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis by Na2S4, as assessed by protein expressions of cleaved-PARP, COX-2, p47phox and TGF-β1 (Fig. S9E). TUNEL assay (Fig. S10) and DHE staining (Fig. S11), further confirmed that addition of DTT neutralized the inhibitory effects of Na2S4 on HG-facilitated HK-2 cell apoptosis and ROS production. The data implied that SIRT1 sulfhydration lowered acetylated and phosphorylated p65/STAT3, thereby contributing to the renoprotective effects of Na2S4.

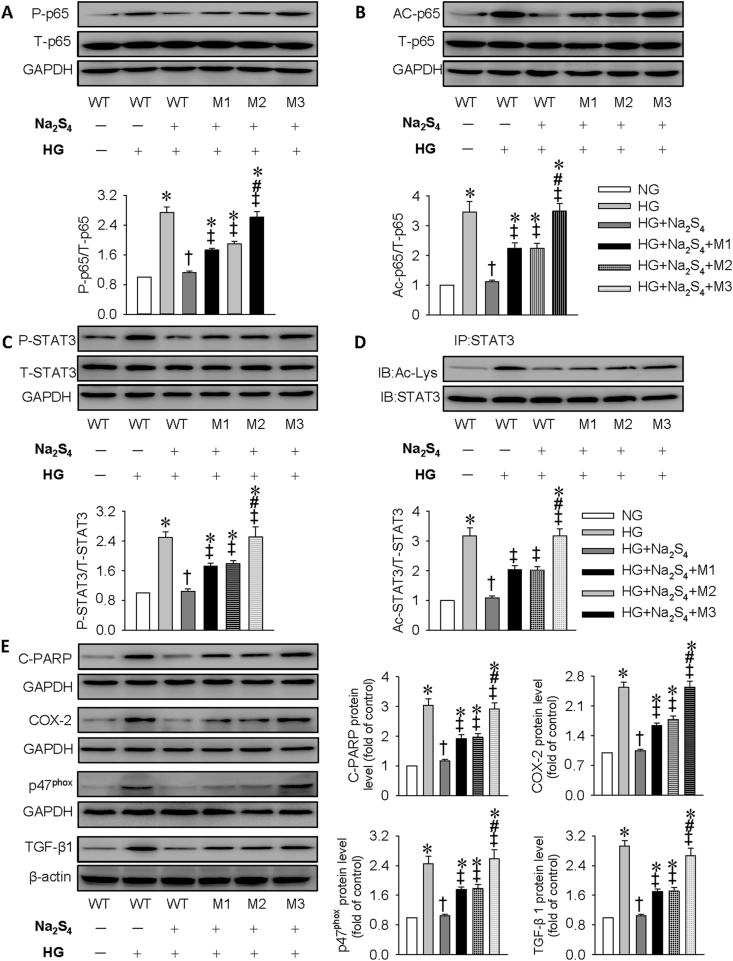

To identify the sulfhydrated cysteine residue sites, SIRT1 mutated at domain 1 (M1: C371S and C374S), domain 2 (M2: C395S and C398S), or both domains (M3: C371S, C374S, C395S, and C398S) or wild type (WT) were transfected into HK-2 cells; the sulfhydrated SIRT1 by Na2S4 was all blocked by the three mutation plasmids (Fig. S8C). Importantly, SIRT1 mutation notably attenuated the suppressive effect of Na2S4 on HG-amplified p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation in HK-2 cells (Fig. 5A–D). Moreover, after SIRT1 mutation transfection, Na2S4 failed to attenuate HG-induced apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis (Fig. 5E). Similar to DTT, Na2S4 treatment is limited to restrain HG-triggered cell apoptosis (Fig. S12) and ROS generation (Fig. S13) when HK-2 cells were transfected with plasmids with SIRT1 mutation. Intriguingly, M3 is likely to completely eliminate the protective effects of Na2S4 on HG-induced HK-2 cell damage when compared with M1 and M2. These findings indicated that sulfhydration of C371S, C374S, C395S, and C398S at SIRT1 is critical for Na2S4 to curb hyperglycemia-induced injury in HK-2 cells.

Fig. 5.

Effects of SIRT1 mutation on phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 as well as HK-2 cell injury induced by HG. HK-2 cells were transfected with wild type (WT) or mutated SIRT1 plasmids for 24 h before incubation of Na2S4 (30 μM) for 30 min, and were stimulated with HG for another 48 h. (A–D) SIRT1 mutation attenuated the suppressive effect of Na2S4 on HG-amplified p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation. (E) Representative blots and quantitative analysis of cleaved PARP (C-PARP), COX-2, p47phox, and TGF-β1 showing that Na2S4 failed to attenuate HG-induced apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis in HK-2 cells with SIRT1 mutation. *P < 0.05 vs. NG. †P < 0.05 vs. HG. ‡P < 0.05 vs. HG + Na2S4. #P < 0.05 vs. HG + Na2S4+M1 or HG + Na2S4+M2. n = 4 to 6.

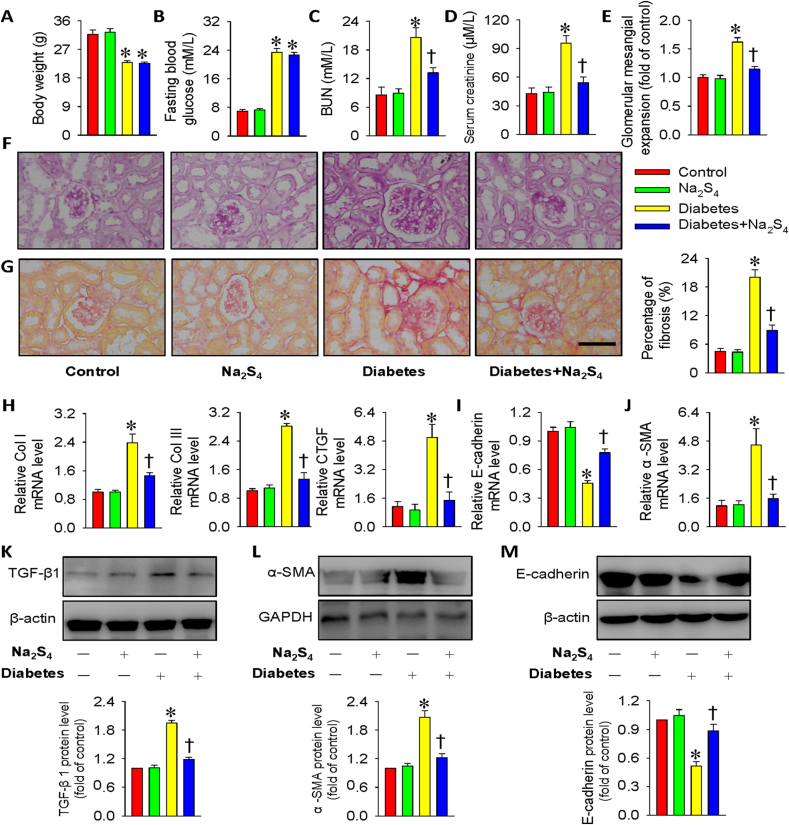

3.7. Na2S4 alleviates renal dysfunction and fibrosis in diabetic mice

Additionally, we moved on to assess the therapeutic effects of Na2S4 on diabetes-induced renal damage in mice. Compared with control mice, the body weight was obviously declined (Fig. 6A), while the fasting blood glucose level was obviously elevated in diabetic mice (Fig. 6B). However, the fasting blood glucose level and body weight in diabetic mice were not influenced by treatment with Na2S4 (Fig. 6A–B). Similar with the previous reports [85,86], the serum levels of BUN and creatinine were dramatically higher in diabetic mice than those in normal mice (Fig. 6C–D). However, chronic treatment of Na2S4 mitigated these renal dysfunction parameters in diabetic mice (Fig. 6C–D). Morphological analysis from PAS staining results demonstrated that the glomerular volume was larger in diabetic mice when compared with control mice, which was obviously attenuated by supplementation of Na2S4 (Fig. 6E–F). Sirius red staining demonstrated that the enlarged renal fibrosis in diabetic mice was attenuated by Na2S4 (Fig. 6G). Consistently, the mRNA expressions of collagen I, collagen III and CTGF were higher in diabetic kidneys, but there was no significant renal fibrosis in diabetic mice treated with Na2S4 (Fig. 6H). In accordance with cell experiments, the diabetic kidneys exhibited lower E-cadherin mRNA expression and higher α-SMA mRNA expression, this effect was rectified by Na2S4 (Fig. 6I–J). Consistent with in vitro results, administration of Na2S4 prevented the upregulated TGF-β1 and α-SMA levels and the downregulated E-cadherin protein expressions in diabetic kidney tissues (Fig. 6K-M). These findings indicated that Na2S4-mediated renal protective effects involve its suppressive effect on the process of EMT.

Fig. 6.

Na2S4 alleviated renal function and renal fibrosis in diabetic mice. (A) Body weight. (B) Fasting blood glucose. (C) BUN level. (D) Serum creatinine level. (E) Quantitative assessment of tubular injury. (F) Representative images of PAS staining. (G) Representative images of Sirius red staining. (H–J) Relative mRNA levels of collagen I, collagen III, CTGF, E-cadherin and α-SMA. (K–M) Representative blot images and quantitative analysis of TGF-β1, α-SMA and E-cadherin. Scale bar = 50 μm *P < 0.05 vs. Control. †P < 0.05 vs. Diabetes. The results were derived from 4 to 8 independent experiments. n = 4 to 8. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

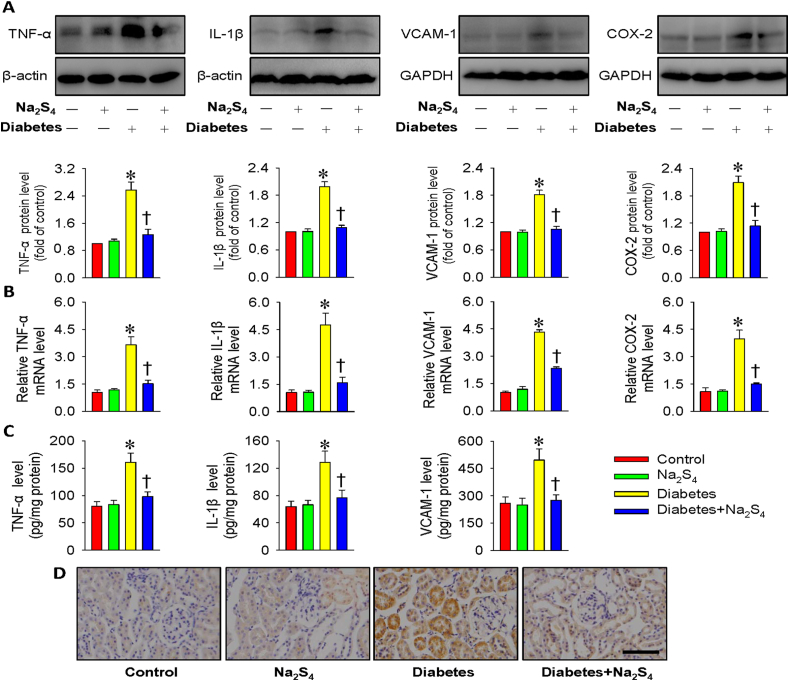

3.8. Na2S4 alleviates renal inflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic mice

In agreement with the cell culture results, hyperglycemia led to strong inflammatory responses in the kidneys as manifested by the massive protein productions of TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2, whereas these effects were suppressed by chronic injection Na2S4 (Fig. 7A). In parallel to Western blotting results, the diabetic kidneys exhibited the enhanced mRNA levels of these inflammatory factors. Accordingly, Na2S4 effectively reversed such abnormalities (Fig. 7B). The anti-inflammatory effects of Na2S4 on diabetic kidneys were further proved by ELISA results (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, Na2S4 treatment obviously prevented the accumulation of macrophages (F4/80-positive cells) in the kidney tissues from diabetic mice (Fig. 7D), suggesting an anti-inflammatory role of Na2S4 in diabetic nephropathy.

Fig. 7.

Na2S4 alleviated renal inflammation response in diabetic mice. (A) Representative blot images and quantitative analysis of TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2. (B) Relative mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, VCAM-1 and COX-2. (C) The protein levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and VCAM-1 measured by ELISA. (D) F4/80-positive macrophages in kidney tissues. Scale bar = 50 μm *P < 0.05 vs. Control. †P < 0.05 vs. Diabetes. n = 4 to 6.

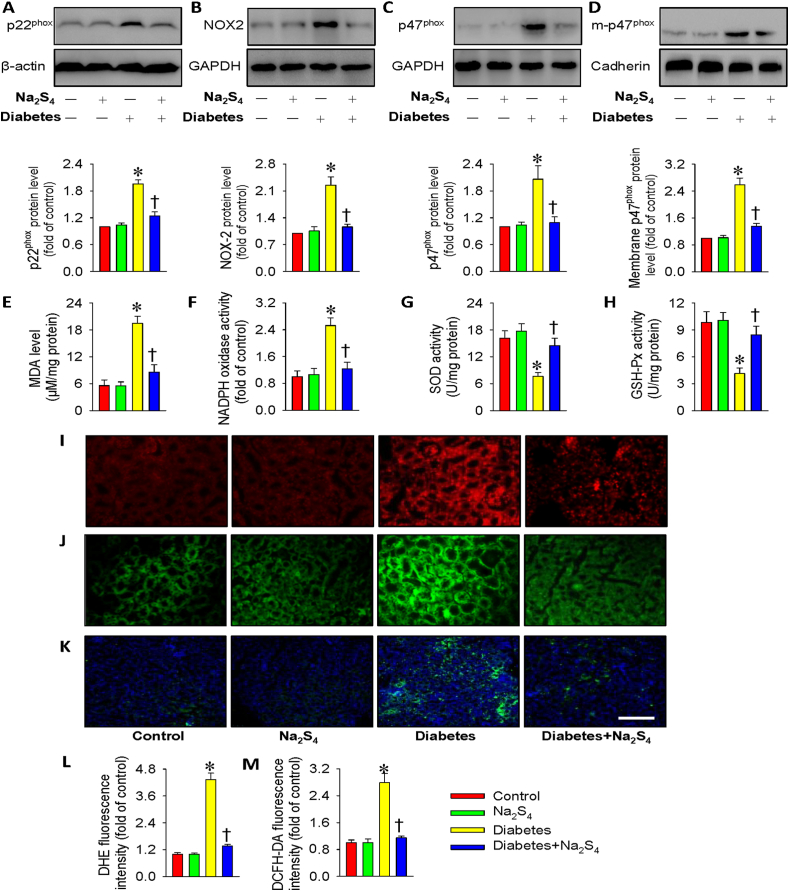

In accordance with in vitro results, the kidneys from diabetic mice had higher p22phox, NOX2, p47phox and membrane p47phox protein levels compared to healthy kidneys (Fig. 8A–D). Na2S4 treatment markedly inhibited the abnormal changes in these proteins from diabetic kidney tissues (Fig. 8A–D). We found increased renal MDA content and NADPH oxidase activity, but decreased renal activities of SOD and GSH-Px in diabetic mice, whereas these aberrant changes were again normalized by treatment with Na2S4 (Fig. 8E–H). Moreover, the results from DHE staining, DCFH-DA staining, and nitrotyrosine immunofluorescence in the kidney tissues showed the decreased renal oxidative stress in diabetic mice when treated with Na2S4 (Fig. 8I-M). These above results hinted that Na2S4 alleviated inflammatory response and reduced ROS production in diabetic mouse kidneys.

Fig. 8.

Na2S4 restrained renal oxidative stress in diabetic mice. (A–D) Representative blot images and quantitative analysis of p22phox, NOX2, p47phox and membrane p47phox. (E) MDA content. (F) NADPH oxidase activity. (G) SOD activity. (H) GSH-Px activity. (I,L) DHE staining in kidney tissues. (J,M) DCFH-DA staining in kidney tissues. (K) Nitrotyrosine immunofluorescence in kidney tissues. Scale bar = 100 μm *P < 0.05 vs. Control. †P < 0.05 vs. Diabetes. n = 4 to 6.

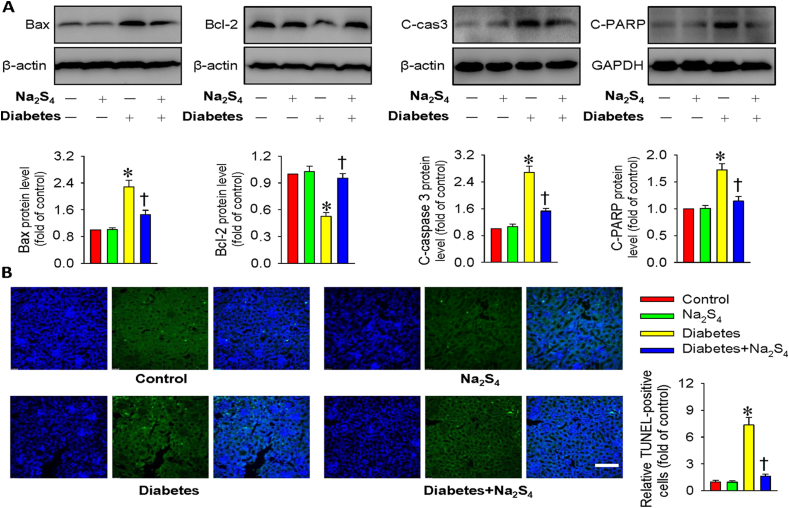

3.9. Na2S4 relieves diabetes-induced renal cell apoptosis in mice

The diabetic renal tissues exhibited higher protein expression levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved-PARP, but lower Bcl-2 protein level, whereas this imbalance in these proteins was prevented by treatment with Na2S4 (Fig. 9A). The involvement of anti-apoptotic effects of Na2S4 in diabetic kidneys was also examined by TUNEL assay. It can be seen that the enhanced TUNEL-positive cells in diabetic kidney tissues were significantly eradicated by application of Na2S4 (Fig. 9B). These results suggested that Na2S4 prevented renal cell apoptosis induced by diabetes or hyperglycemia.

Fig. 9.

Na2S4 relieved renal cell apoptosis in diabetic mice. (A) Representative blots and quantitative analysis of Bax, Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3 (c-cas3) and cleaved-PARP (c-PARP). (B) Representative images of TUNEL staining of kidney tissues. Scale bar = 100 μm *P < 0.05 vs. Control. †P < 0.05 vs. Diabetes. n = 4 to 6.

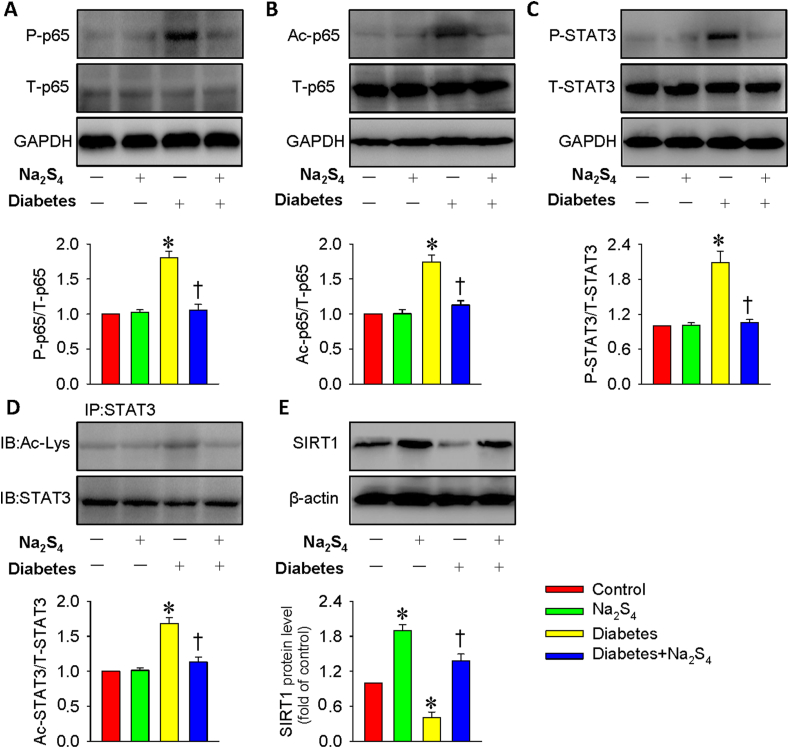

3.10. Na2S4 upregulates SIRT1 to affect p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation in diabetic nephropathy

After injection of STZ for 12 weeks, our data showed that the diabetes-induced upregulations of p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation in the kidneys were also attenuated by Na2S4 treatment, which was consistent with the cell experiments (Fig. 10A–D). Western blotting results showed that the SIRT1 expression was obviously downregulated in diabetic mice-derived renal tissues, and this decline was largely prevented by Na2S4 treatment, which itself also facilitated the expression of SIRT1 (Fig. 10E).

Fig. 10.

Na2S4 upregulated SIRT1 to affect p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation in diabetic nephropathy. (A–B) Effects of Na2S4 on the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB. (C–D) Effects of Na2S4 on the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of STAT3. (E) Treatment with Na2S4 reversed diabetes-downregulated SIRT1 protein levels in the kidneys. *P < 0.05 vs. Control. †P < 0.05 vs. Diabetes. n = 4 to 6.

4. Discussion

In the present study, biochemical and histopathological studies indicated that exogenous administration of Na2S4 could efficiently attenuate diabetic renal injury via attenuating renal cell apoptosis and inflammation, antagonizing renal oxidative stress and fibrosis in mice. Mechanistically, our findings showed that Na2S4 directly sulfhydrated and upregulated SIRT1 protein expression, thereby reversing diabetic renal dysfunction via inactivating the phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 NF-κB/STAT3 (Fig. S14). These results suggested that polysulfides may serve as promising candidates to prevent or treat diabetic nephropathy.

Diabetic nephropathy is manifested by the presence of urine albumin excretion, glomerular lesions, mesangial expansion, renal and glomerular hypertrophy, and loss of glomerular filtration rate [87,88]. In this study, the therapeutic effects of Na2S4 in diabetic nephropathy were evaluated in diabetic mice. We here showed that Na2S4 could improve diabetic renal dysfunction by potently decreasing the levels of creatinine and BUN even with affecting neither blood glucose level nor body weight. Histological examination by PAS staining further corroborated the therapeutic role of Na2S4 in diabetic kidney disease. In the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy, renal fibrosis is a definitive end event, which is ascribed to overproduction of ECM proteins in the tubular interstitial space [89]. Studies have established that TGF-β1 is a crucial mediator in diabetic renal fibrosis [90]. Our present results demonstrated that the protein and mRNA expressions of TGF-β1 were markedly augmented in diabetic kidney tissues and HG-incubated HK-2 cells, and this effect was suppressed by Na2S4. Additionally, Na2S4 treatment retarded the progression of EMT and diabetic renal fibrosis, as manifested by downregulated α-SMA and upregulated E-cadherin. These results suggested that Na2S4 alleviated renal fibrosis in diabetic mice via blockade of EMT process.

A plethora of evidence has demonstrated that both oxidative stress and inflammation are responsible for the pathologies of diabetic nephropathy [91]. In addition to this, the tubular cell apoptosis is also a classic hallmark of diabetic nephropathy, whereby apoptotic cell death may be attributed to renal inflammation and oxidative stress [92]. We found in the present study that Na2S4 exhibited an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing inflammatory factors release in both cells and kidneys under hyperglycemia conditions. Also, the anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic effects of Na2S4 had been described in both diabetic renal tissues and HG-treated HK-2 cells. These results provide the ample evidence that Na2S4 could retain the anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and anti-apoptotic characteristics in a diabetic setting, which might be important protective mechanisms against diabetic nephropathy. Together with above discussion, it is concluded that Na2S4 may be taken as a therapeutic agent for diabetic kidney disease by inhibiting renal cell apoptosis and inflammation response, and delaying renal oxidative stress and fibrosis.

The precise molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis in diabetic kidney disease are not comprehensively elucidated. Compelling evidence indicates that SIRT1 is a crucial dominator in the pathologies of diabetic nephropathy as SIRT1 confers renal protection by inhibiting renal inflammation, apoptosis, oxidative stress and fibrosis [93,94]. The higher acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 are detected in diabetic kidneys, and this may be caused by downregulation of SIRT1 protein in diabetic kidney tissues [70]. Moreover, the phosphorylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 are also markedly elevated in SIRT knockout mice-derived kidney tissues after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge [95]. Sen et al. have provided ample evidence that H2S produces anti-apoptotic transcriptional activity through sulfhydration of p65 NF-κB at cysteine-38 and the subsequent activation of its coactivator ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3) [96]. These findings highlight the important role of p65 NF-κB sulfhydration in H2S-mediated signaling transduction. Importantly, H2S is a potential SIRT1 activator through SIRT1 sulfhydration, thus contributing to reduced atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice [84]. The current evidence might yield a hypothesis that Na2S4 may play a protective role in diabetic nephropathy via inducing the sulfidation and upregulation of SIRT1. Our data showed substantial sulfidation and upregulation of SIRT1 upon treatment with Na2S4. After that, sulfhydrated and upregulated SIRT1 caused deacetylation and dephosphorylation of its target genes p65 NF-κB and STAT3; then lowered renal cell apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative damage and fibrosis in vitro and in vivo. It is of utmost important to demonstrate whether blockade or de-sulfhydration of SIRT1 abolished Na2S4-mediated effects. As we predicted, administration of a specific SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 or a de-sulfhydration reagent DTT removed the actions of Na2S4 on the acetylation and phosphorylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3 as well as eliminated its following protective effects against HG-induced cell injury in HK-2 cells. Similar to EX527, deficiency of SIRT1 by its specific siRNA also abolished the protective effects of Na2S4 against HG-induced cell injury in HK-2 cells.

Importantly, mutation of Cys371, Cys374, Cys395, and Cys398 sites of SIRT1 not only abolished Na2S4-mediated deacetylation and dephosphorylation of p65 NF-κB and STAT3, but also attenuated Na2S4-induced beneficial effects in HG-challenged HK-2 cells. We therefore proposed that sulfhydration of SIRT1 may induce the deacetylation and dephosphorylation of p65 NF-κB and STAT3, which may partially account for Na2S4-mediated protective effects we observed. Overall, both upregulation and sulfhydration of SIRT1 by Na2S4 might provide renoprotection in mouse models of diabetes through lowering the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of p65 NF-κB and STAT3. Although we had confirmed that SIRT1 is involved in Na2S4-mediated renal protection, the direct effects of polysulfides in the renal system still need to be elucidated. S-sulfhydration might exert biological functions together with other post-translational modifications like phosphorylation, S-nitrosylation and tyrosine nitration [97]. As such, it warrants further studies to investigate whether the protective effects of polysulfides were also mediated by other post-translational modifications. Moreover, further research is needed to investigate the precise molecular mechanisms of Na2S4 using specific renal tubular epithelial cell SIRT1 knockout mice.

In conclusion, we reported that Na2S4 could effectively ameliorate diabetes-induced renal damage through restoring the biochemical and histological alterations. Moreover, our data also showed that Na2S4 ameliorated diabetes-caused renal injury by sulfhydrating and upregulating SIRT1 protein expression, followed by inhibition of p65 NF-κB/STAT3 phosphorylation and acetylation. Apart from renal tubular epithelial cells, the dysregulated renal mesangial cells and podocytes are also major contributors in the pathologies of diabetic nephropathy [98]. Therefore, it will be interesting to know whether Na2S4 benefits diabetic kidneys by affecting these renal cells in future studies. Based on the current study, we proposed Na2S4 as an attractive drug for the treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Notably, whether polysulfides could be promising therapeutic candidates for diabetic nephropathy in clinical trials might need further research.

4.1. Limitations

It is believed that H2S is implicated in a large number of physiological functions indirectly via the generation of reactive sulfane sulfur species [99,100]. For instance, S-sulfhydration of cysteine residues (protein Cys-SSH) is one of the important mechanisms of H2S-mediated numerous functions [97]. Moreover, H2S and reactive sulfane sulfur are very likely to coexist in biological system since they are normally interchangeable [101]. It has been demonstrated that sulfane sulfur species is much more effective than H2S in protein S-sulfhydration, and sulfane sulfur species may be responsible for at least some biological activities of H2S [102]. Actually, sulfane sulfur species is endogenously expressed in biological systems, and they contribute to H2S-mediated protein S-sulfhydration reactions by targeting a number of different proteins [103]. As such, when cells or animals are treated with sulfane sulfur compounds, the observed net biological effects might represent the outcomes of multiple affected pathways [104]. A better understanding of the complex biochemical properties of sulfane sulfur compounds is an important prerequisite for future research on H2S/polysulfide biology and pharmacology, which merits further study. Given that polysulfides might be involved in a variety of biological effects through affecting a host of different proteins or multiple pathways, we speculated that Na2S4 would exert renal protection through other unknown molecular targets and signaling pathways, especially the sulfhydrating modifications of other proteins of interest (not only SIRT1). This will be investigated in our further studies. Additional studies about the effects of polysulfides on biochemical/molecular reactions of target organs or cells are required to better understand how sulfide metabolites lead to sophisticated chemical biology reactions involved in renal health. The comparisons of the protective effects of sulfide and polysulfides on cells or tissues remain unclear, which merits further studies. Additionally, the distribution of sulfide pools, including H2S and polysulfides in the kidneys under healthy or pathological conditions deserves further research to ascertain their exact roles in renal protection. Moreover, endogenous polysulfide formation and their physiological and/or pathophysiological properties may also be recognized as the future directions for the research of gasotransmitters.

Interestingly, the used dose of Na2S4 in the present study was 30 μM (although this concentration is not cytotoxic), which might release higher levels of sulfane sulfur to impact a number of biological events in HK-2 cells. A study has found that Na2S4 (25 μM) could be quickly taken up by nerve cells after a few minutes of exposure, suggesting that Na2S4 might produce HS− or persulfides through reacting with the SH groups of proteins or thiols in cells [27]. Moreover, intracellular levels of bound sulfur are significantly decreased at 2 h when compared to those within a few minutes [27]. Based on these results, the authors theorized that polysulfides might be either oxidized or secreted from cells or are converted into other forms [27]. In light of this, we speculated that Na2S4-derived sulfane sulfur (30 μM, not exceeding cytotoxicity) may be metabolized by other unknown pathways in HK-2 cells. The complex biochemical reactions caused by sulfane sulfur from different concentrations of Na2S4 are continuously being identified. The sulfide exchange mechanisms that eliminate the excessive sulfane sulfur species should exist in cells, and this hypothesis still awaits further research. Also, the possible polysulfide catabolizing enzymes might be other factors that decompose excessive sulfane sulfur, and this obviously requires further investigation. In this study, a polysulfide donor, Na2S4, was used in the in vitro and in vivo studies. Unfortunately, the cellular or tissue polysulfide levels were not examined due to the technique limitation. The measurement of polysulfides in biological samples is extremely difficult due to the abundance of other types of polysulfides, such as organic polysulfides [19,21]. Therefore, it remains to be investigated whether the protective effects of Na2S4 are associated with the changes in polysulfide levels in cells and renal tissues. In addition, polysulfides contain sulfane sulfur that is present in various proteins. This may be a potential intracellular H2S storage that releases H2S under reducing conditions [36,105,106]. As a consequence, it is highly possible that Na2S4, a polysulfide donor, might liberate H2S that would be the protective mediator in diabetic nephropathy. This needs to be demonstrated in the future.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Singapore National Medical Research Council (NMRC/CIRG/163/2013 and NMRC/1274/2010, JSB), National Natural Science Foundation of China of China (81872865, JSB) and Jiangsu Nature Science Foundation (BK20181185, JSB).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101813.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sun H.J., Wu Z.Y., Cao L., Zhu M.Y., Liu T.T., Guo L., Lin Y., Nie X.W., Bian J.S. Hydrogen sulfide: recent progression and perspectives for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Molecules. 2019;24 doi: 10.3390/molecules24152857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feliers D., Lee H.J., Kasinath B.S. Hydrogen sulfide in renal physiology and disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2016;25:720–731. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duran-Salgado M.B., Rubio-Guerra A.F. Diabetic nephropathy and inflammation. World J. Diabetes. 2014;5:393–398. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dugbartey G.J. Diabetic nephropathy: a potential savior with 'rotten-egg' smell. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017;69:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruden G., Perin P.C., Camussi G. Insight on the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy from the study of podocyte and mesangial cell biology. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2005;1:27–40. doi: 10.2174/1573399052952622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X., Feng Y., Zhan Z., Chen J. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates diabetic nephropathy in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:28827–28834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.596593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardue S., Kolluru G.K., Shen X., Lewis S.E., Saffle C.B., Kelley E.E., Kevil C.G. Hydrogen sulfide stimulates xanthine oxidoreductase conversion to nitrite reductase and formation of NO. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101447. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takano Y., Shimamoto K., Hanaoka K. Chemical tools for the study of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and sulfane sulfur and their applications to biological studies. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2016;58:7–15. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.15-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura H. Physiological role of hydrogen sulfide and polysulfide in the central nervous system. Neurochem. Int. 2013;63:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide and polysulfide signaling. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2017;27:619–621. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou N., Yan Z., Fan K., Li H., Zhao R., Xia Y., Xun L., Liu H. OxyR senses sulfane sulfur and activates the genes for its removal in Escherichia coli. Redox Biol. 2019;26:101293. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan S., Pardue S., Shen X., Alexander J.S., Orr A.W., Kevil C.G. Hydrogen sulfide metabolism regulates endothelial solute barrier function. Redox Biol. 2016;9:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides as signaling molecules. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2015;91:131–159. doi: 10.2183/pjab.91.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamid H.A., Tanaka A., Ida T., Nishimura A., Matsunaga T., Fujii S., Morita M., Sawa T., Fukuto J.M., Nagy P., Tsutsumi R., Motohashi H., Ihara H., Akaike T. Polysulfide stabilization by tyrosine and hydroxyphenyl-containing derivatives that is important for a reactive sulfur metabolomics analysis. Redox Biol. 2019;21:101096. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson K.R., Gao Y., Arif F., Arora K., Patel S., DeLeon E.R., Sutton T.R., Feelisch M., Cortese-Krott M.M., Straub K.D. Metabolism of hydrogen sulfide (H(2)S) and production of reactive sulfur species (RSS) by superoxide dismutase. Redox Biol. 2018;15:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson K.R., Gao Y., DeLeon E.R., Arif M., Arif F., Arora N., Straub K.D. Catalase as a sulfide-sulfur oxido-reductase: an ancient (and modern?) regulator of reactive sulfur species (RSS) Redox Biol. 2017;12:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson K.R.H. (2)S and polysulfide metabolism: conventional and unconventional pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018;149:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ide M., Ohnishi T., Toyoshima M., Balan S. Vol. 11. 2019. (Excess Hydrogen Sulfide and Polysulfides Production Underlies a Schizophrenia Pathophysiology). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao X., Zhang W., Moore P.K., Bian J. Protective smell of hydrogen sulfide and polysulfide in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20020313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura Y., Mikami Y., Osumi K., Tsugane M., Oka J., Kimura H. Polysulfides are possible H2S-derived signaling molecules in rat brain. Faseb. J. 2013;27:2451–2457. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-226415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura Y., Toyofuku Y., Koike S., Shibuya N., Nagahara N., Lefer D., Ogasawara Y., Kimura H. Identification of H2S3 and H2S produced by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the brain. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14774. doi: 10.1038/srep14774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Z., Song B., Zhang W., Duan C., Wang Y.L., Liu C., Zhang R. Vol. 57. 2018. pp. 3999–4004. (Quantitative Monitoring and Visualization of Hydrogen Sulfide In Vivo Using a Luminescent Probe Based on a Ruthenium(II) Complex). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koike S., Nishimoto S., Ogasawara Y. Cysteine persulfides and polysulfides produced by exchange reactions with H(2)S protect SH-SY5Y cells from methylglyoxal-induced toxicity through Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol. 2017;12:530–539. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan S., Shen X., Kevil C.G. Beyond a gasotransmitter: hydrogen sulfide and polysulfide in cardiovascular health and immune response. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2017;27:634–653. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bátai I.Z., Sár C.P., Horváth Á., É Borbély, Bölcskei K., Kemény Á., Sándor Z., Nemes B., Helyes Z., Perkecz A., Mócsai A., Pozsgai G., Pintér E. TRPA1 ion channel determines beneficial and detrimental effects of GYY4137 in murine serum-transfer arthritis. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:964. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikeda M., Ishima Y., Kinoshita R., Chuang V.T.G., Tasaka N., Matsuo N., Watanabe H., Shimizu T., Ishida T., Otagiri M., Maruyama T. A novel S-sulfhydrated human serum albumin preparation suppresses melanin synthesis. Redox Biol. 2018;14:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koike S., Ogasawara Y., Shibuya N., Kimura H., Ishii K. Polysulfide exerts a protective effect against cytotoxicity caused by t-buthylhydroperoxide through Nrf2 signaling in neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3548–3555. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koike S., Shibuya N., Kimura H., Ishii K., Ogasawara Y. Polysulfide promotes neuroblastoma cell differentiation by accelerating calcium influx. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;459:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moustafa A., Habara Y. Cross talk between polysulfide and nitric oxide in rat peritoneal mast cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2016;310:C894–C902. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00028.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abiko Y., Sha L., Shinkai Y., Unoki T., Luong N.C., Tsuchiya Y., Watanabe Y., Hirose R., Akaike T., Kumagai Y. 1,4-Naphthoquinone activates the HSP90/HSF1 pathway through the S-arylation of HSP90 in A431 cells: negative regulation of the redox signal transduction pathway by persulfides/polysulfides. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;104:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abiko Y., Shinkai Y., Unoki T., Hirose R., Uehara T., Kumagai Y. Polysulfide Na(2)S(4) regulates the activation of PTEN/Akt/CREB signaling and cytotoxicity mediated by 1,4-naphthoquinone through formation of sulfur adducts. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4814. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04590-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akiyama M., Shinkai Y., Unoki T., Shim I., Ishii I., Kumagai Y. The capture of cadmium by reactive polysulfides attenuates cadmium-induced adaptive responses and hepatotoxicity. 2017;30:2209–2217. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi S., Hisatsune A., Kurauchi Y., Seki T., Katsuki H. Polysulfide protects midbrain dopaminergic neurons from MPP(+)-induced degeneration via enhancement of glutathione biosynthesis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;137:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang K., Coburger I., Langner J.M., Peter N., Hoshi T., Schönherr R., Heinemann S.H. Vol. 471. 2019. pp. 557–571. (Modulation of K(+) Channel N-type Inactivation by Sulfhydration through Hydrogen Sulfide and Polysulfides). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Araki S., Takata T., Tsuchiya Y., Watanabe Y. Reactive sulfur species impair Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II via polysulfidation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;508:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoji T., Hayashi M. Pharmacological polysulfide suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in an ATP-sensitive potassium channel-dependent manner. 2019;9:19377. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55848-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasinath B.S., Feliers D., Lee H.J. Hydrogen sulfide as a regulatory factor in kidney health and disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018;149:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao X., Nie X., Xiong S., Cao L., Wu Z., Moore P.K., Bian J.S. Renal protective effect of polysulfide in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Redox Biol. 2018;15:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou C., Li W., Pan Y., Khan Z.A., Li J., Wu X., Wang Y., Deng L., Liang G., Zhao Y. 11beta-HSD1 inhibition ameliorates diabetes-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis through modulation of EGFR activity. Oncotarget. 2017;8:96263–96275. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong P., Wu L., Qian Y., Fang Q., Liang D., Wang J., Zeng C., Wang Y., Liang G. Blockage of ROS and NF-kappaB-mediated inflammation by a new chalcone L6H9 protects cardiomyocytes from hyperglycemia-induced injuries. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1852:1230–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun H.J., Xiong S.P., Wu Z.Y., Cao L., Zhu M.Y., Moore P.K., Bian J.S. Induction of caveolin-3/eNOS complex by nitroxyl (HNO) ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy. Redox Biol. 2020;32:101493. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Feng J., Zhang Y., Feng J., Wang Q., Zhao S., Meng P., Li J. Mst1 deletion attenuates renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury: the role of microtubule cytoskeleton dynamics, mitochondrial fission and the GSK3beta-p53 signalling pathway. Redox Biol. 2019;20:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang Y., Liu J., Zhou Z., Liu K., Liu C. Diosmetin attenuates akt signaling pathway by modulating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kappaB)/Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in streptozotocin (STZ)-Induced diabetic nephropathy mice. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018;24:7007–7014. doi: 10.12659/MSM.910764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao X., Xiong S., Zhou Y., Wu Z., Ding L., Zhu Y., Wood M.E., Whiteman M., Moore P.K., Bian J.S. Renal protective effect of hydrogen sulfide in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;29:455–470. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao L., Cao X., Zhou Y., Nagpure B.V., Wu Z.Y., Hu L.F., Yang Y., Sethi G., Moore P.K., Bian J.S. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits ATP-induced neuroinflammation and Abeta1-42 synthesis by suppressing the activation of STAT3 and cathepsin S. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018;73:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu X., Zhou Z., Zhang Q., Cai W., Zhou Y., Sun H., Qiu L. Vaccarin administration ameliorates hypertension and cardiovascular remodeling in renovascular hypertensive rats. 2018;119:926–937. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen H., Fang K., Guo H., Wang G. High glucose-induced apoptosis in human kidney cells was alleviated by miR-15b-5p mimics. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019;42:758–763. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b18-00951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen F., Sun Z., Zhu X., Ma Y. Astilbin inhibits high glucose-induced autophagy and apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt pathway in human proximal tubular epithelial cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;106:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu X., Wu S., Guo H. 2019. Active Vitamin D and Vitamin D Receptor Help Prevent High Glucose Induced Oxidative Stress of Renal Tubular Cells via AKT/UCP2 Signaling Pathway; p. 9013904. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Q., Li Y., Luo J., Yang Y., Li J., Sun L., Xiao L., Xu X., Peng Y., Liu F. [Effect of norcantharidin on the expression of FN, Col IV and TGF-β1 mRNA and protein in HK-2 cells induced by high glucose] Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;37:278–284. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Covington M.D., Schnellmann R.G. Chronic high glucose downregulates mitochondrial calpain 10 and contributes to renal cell death and diabetes-induced renal injury. Kidney Int. 2012;81:391–400. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu B., Yang J., Chen J., Lin L., Chen K., Zhang W., Zhang J., He Y. Preventive effect of Shenkang injection against high glucose-induced senescence of renal tubular cells. Front. Med. 2019;13:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0586-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Z., Guo Z., Dong J., Sheng S., Wang Y., Yu L., Wang H., Tang L. miR-374a regulates inflammatory response in diabetic nephropathy by targeting MCP-1 expression. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:900. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verzola D., Bertolotto M.B., Villaggio B., Ottonello L., Dallegri F., Frumento G., Berruti V., Gandolfo M.T., Garibotto G., Deferran G. Taurine prevents apoptosis induced by high ambient glucose in human tubule renal cells. J. Invest. Med. 2002;50:443–451. doi: 10.1136/jim-50-06-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turkmen K. Inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy in diabetes mellitus and diabetic kidney disease: the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017;49:837–844. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jha J.C., Ho F., Dan C., Jandeleit-Dahm K. A causal link between oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiovascular and renal complications of diabetes. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2018;132:1811–1836. doi: 10.1042/CS20171459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jha J.C., Banal C., Chow B.S., Cooper M.E., Jandeleit-Dahm K. Diabetes and kidney disease: role of oxidative stress. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2016;25:657–684. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park J., Kwon M.K., Huh J.Y., Choi W.J., Jeong L.S., Nagai R., Kim W.Y., Kim J., Lee G.T., Lee H.B., Ha H. Renoprotective antioxidant effect of alagebrium in experimental diabetes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011;26:3474–3484. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Q.B., Du Q., Wang H.P., Tang Z.H., Wang Y.B., Sun H.J. Salusin-beta mediates tubular cell apoptosis in acute kidney injury: involvement of the PKC/ROS signaling pathway. Redox Biol. 2019;30:101411. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin Y.C., Chang Y.H., Yang S.Y., Wu K.D., Chu T.S. Update of pathophysiology and management of diabetic kidney disease. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018;117:662–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murphy M., Hickey F., Godson C. IHG-1 amplifies TGF-beta1 signalling and mitochondrial biogenesis and is increased in diabetic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2013;22:77–84. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835b54b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hills C.E., Squires P.E. The role of TGF-beta and epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iwano M., Plieth D., Danoff T.M., Xue C., Okada H., Neilson E.G. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun H.J. Current opinion for hypertension in renal fibrosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019;1165:37–47. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morigi M., Perico L., Benigni A. Sirtuins in renal health and disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018;29:1799–1809. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017111218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kitada M., Kume S., Takeda-Watanabe A., Kanasaki K., Koya D. Sirtuins and renal diseases: relationship with aging and diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2013;124:153–164. doi: 10.1042/CS20120190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guan Y., Hao C.M. SIRT1 and kidney function. Kidney Dis. 2016;1:258–265. doi: 10.1159/000440967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hou C.L., Wang M.J., Sun C., Huang Y., Jin S., Mu X.P., Chen Y., Zhu Y.C. 2016. Protective Effects of Hydrogen Sulfide in the Ageing Kidney; p. 7570489. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hong Q., Zhang L., Das B., Li Z., Liu B., Cai G., Chen X., Chuang P.Y., He J.C., Lee K. Increased podocyte Sirtuin-1 function attenuates diabetic kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2018;93:1330–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu R., Zhong Y., Li X., Chen H., Jim B., Zhou M.M., Chuang P.Y., He J.C. Role of transcription factor acetylation in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2014;63:2440–2453. doi: 10.2337/db13-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kolati S.R., Kasala E.R., Bodduluru L.N., Mahareddy J.R., Uppulapu S.K., Gogoi R., Barua C.C., Lahkar M. BAY 11-7082 ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by attenuating hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and renal inflammation via NF-kappaB pathway. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015;39:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tang J., Liu C.Y., Lu M.M., Zhang J., Mei W.J., Yang W.J., Xie Y.Y., Huang L., Peng Z.Z., Yuan Q.J., Liu J.S., Hu G.Y., Tao L.J. Fluorofenidone protects against renal fibrosis by inhibiting STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015;407:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li G., Xia Z., Liu Y., Meng F., Wu X., Fang Y., Zhang C., Liu D. SIRT1 inhibits rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte aggressiveness and inflammatory response via suppressing NF-kappaB pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2018;38 doi: 10.1042/BSR20180541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu J., Li Y., Lou M., Xia W., Liu Q., Xie G., Liu L., Liu B., Yang J., Qin M. Baicalin regulates SirT1/STAT3 pathway and restrains excessive hepatic glucose production. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;136:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eid R.A., Bin-Meferij M.M., El-Kott A.F., Eleawa S.M., Zaki M.S.A., Al-Shraim M., El-Sayed F., Eldeen M.A., Alkhateeb M.A., Alharbi S.A., Aldera H., Khalil M.A. Exendin-4 protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by upregulation of SIRT1 and SIRT3 and activation of AMPK. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12265-020-09984-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]