Abstract

An epidemic caused by an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in China in December 2019 has since rapidly spread internationally, requiring urgent response from the clinical diagnostics community. We present a detailed overview of the clinical validation and implementation of the first laboratory-developed real-time RT-PCR test offered in the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital system following the Emergency Use Authorization issued by the US Food and Drug Administration. Nasopharyngeal and sputum specimens (n = 174) were validated using newly designed dual-target real-time RT-PCR (altona RealStar SARS-CoV-2 Reagent) for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in upper respiratory tract and lower respiratory tract specimens. Accuracy testing demonstrated excellent assay agreement between expected and observed values and comparable diagnostic performance to reference tests. The limit of detection was 2.7 and 23.0 gene copies per reaction for nasopharyngeal and sputum specimens, respectively. Retrospective analysis of 1694 upper respiratory tract specimens from 1571 patients revealed increased positivity in older patients and males compared with females, and an increasing positivity rate from approximately 20% at the start of testing to 50% at the end of testing 3 weeks later. Herein, we demonstrate that the assay accurately and sensitively identifies SARS-CoV-2 in multiple specimen types in the clinical setting and summarize clinical data from early in the epidemic in New York City.

The novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a member of the Betacoronavirus genera in the subfamily Coronavirinae, which are known to cause respiratory illness and gastroenteritis in humans.1 , 2 An outbreak of respiratory disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, first detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, rapidly spread to other countries, including the United States.3 , 4 New York City in particular became an epicenter of the pandemic.5 Given the devastating impact on the health care system and the need for accurate and quick diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has established a rapid pathway for using laboratory-developed tests that was outlined in a guidance document published on February 29, 2020 (https://www.fda.gov/media/135659/download, last accessed October 22, 2020). According to this guidance, SARS-CoV-2 testing could be performed by Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified high-complexity laboratories under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), according to a set of recommendations regarding the minimum validation required for ensuring the analytical and clinical validity of the test. Details of the test and validation had to be submitted by the laboratory to the FDA through an EUA application within 15 days of initiating testing, after which testing could continue provisionally until a decision by the FDA was rendered.

The CDC and the New York State Department of Health had designed and manufactured new test kits for SARS-CoV-2. However, few laboratories were able to get access to these reagents or had the required instruments, which were also not available in our institution. Limited access to SARS-CoV-2 RNA reference control material presented another significant hurdle to the validation process. The FDA EUA announcement required laboratories to procure SARS-CoV-2 RNA from the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCEVA) or the NIH Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository.

The scale of demand for diagnostic testing and the shortage of supplies led to the need for high-throughput testing that could be readily implemented in a variety of laboratories. Herein, we describe the validation and implementation of an EUA test in respiratory tract, including nasopharyngeal (NP) and sputum specimens, using research use only RealStar SARS-CoV-2 Reagent (altona Diagnostics GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). We also detail workflow considerations and results using the test from the early days of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in New York City (March 11, 2020, through March 31, 2020) for upper tract respiratory (URT) specimens and after the peak number of cases (April 17, 2020, to May 15, 2020) for lower respiratory tract (LRT) specimens.

Materials and Methods

Viral RNA, Validation Samples, and Clinical Cohort

SARS-CoV-2 RNA reference material from WRCEVA was obtained from the University of Texas Medical Branch (strain USA_WA1/2020, lot TVP 23156) for use in clinical evaluation and limit of detection (LOD) studies. Clinical samples used for the initial validation were residual NP and sputum samples from routine clinical testing of patients suspected of having respiratory tract infections and pooled archived frozen (NP and sputum) samples used as matrix for generating contrived specimens. Reactive clinical NP samples also included four SARS-CoV-2–positive samples tested by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. NP samples were tested for the presence of 21 common respiratory viruses using the BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Pathogen 2 panel (BioFire Diagnostics, LLC, Salt Lake City, UT). Moreover, to further evaluate the performance of the test, a total of 30 NP and 20 sputum patient specimens were also analyzed in parallel using the Roche cobas 6800 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) or the Cepheid GeneXpert (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) and the Hologic Panther Fusion system (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA), respectively. Additional retrospective analysis of patient characteristics was performed on consecutive URT (n = 1694) and LRT (n = 141) specimens obtained from patients with high suspicion for COVID-19 who were treated at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital campuses between March 11, 2020, and March 31, 2020, and between April 17, 2020, and May 15, 2020, respectively. The Institutional Review Board Committee at Weill Cornell Medicine approved this study.

Real-Time RT-PCR Testing

All specimens were initially processed using Biosafety level 2 biosafety measures (CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html, last accessed October 22, 2020). An off-board lysis viral inactivation step was performed on 200 μL of NP swab viral transport media and was followed by automated extraction of total nucleic acid using the QIAsymphony DSP Virus/Pathogen Mini Kit coupled on the QIAsymphony SP (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) to produce a resulting eluate volume of 60 μL. For lysis inactivation, specimens were mixed with ACL buffer, followed by vortexing with a lysis mix consisting of internal control (IC), carrier RNA, proteinase K, and AVE and ATL buffers, and then incubated at 68°C for 15 minutes. The IC consisted of proprietary artificial RNA/DNA molecules with no homologies to any other known sequences, and was included with the RT-PCR reagents. For sputum, 100 μL of specimen was first treated with 0.3% dithiothreitol solution (1:1 ratio) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes to reduce viscosity.

One-step reverse transcription to cDNA and real-time RT-PCR of the viral targets E (Envelope) and S (Spike) genes were performed, and IC was performed using 10 μL total nucleic acid eluate and the RealStar SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR Kit 1.0 (altona Diagnostics GmbH) on the Rotor-Gene Q Thermocyler (Qiagen) in a total reaction volume of 30 μL. PCR amplification and detection were performed using multicolor fluorescent dye–labeled probes for the identification and differentiation of B-betacoronavirus, SARS-CoV-2–specific RNA, and IC in a single reaction. Samples in which both the E and the S genes or only the E gene or the S gene SARS-CoV-2 RNA targets were detected within the first 40 cycles of amplification were considered positive. The sole presence of E gene target was classified as B-betacoronavirus detected. Failure to detect any viral target and IC signal was classified as indeterminate.

Assay Performance Characteristics

The FDA EUA guidance specified four distinct performance characteristics, consisting of LOD, inclusivity (analytical sensitivity), cross-reactivity (analytical specificity), and clinical evaluation. For the LOD studies, six 10-fold serial dilutions (1 × 101 to 107) were performed with three replicates at each concentration by spiking WRCEVA RNA (6 × 105 plaque-forming units/μL stock WRCEVA RNA reference material; approximately 6 × 107 genomic copies/μL) into NP and sputum RNA eluates obtained from pooled-negative patient NP or sputum specimens.6 LOD was confirmed with 20 additional replicates for each type of sample (sputum and NP). For the accuracy studies, a total of 104 positive (54 NP swabs and 60 sputum) and 70 negative (40 NP swabs and 30 sputum) specimens were used. Positive specimens were either real patient specimens tested by orthogonal methods or contrived specimens that were generated by spiking WRCEVA RNA into pooled negative NP or sputum specimen RNA eluates, as described above. Twenty of the contrived clinical specimens were spiked at a concentration of 1× to 2× LOD, with the remainder of samples spanning the assay testing range. FDA guidance defined the acceptance criteria for test performance as 95% agreement at 1× to 2× LOD and 100% agreement at all other concentrations and negative specimens.6 Inclusivity and cross-reactivity studies were performed by altona Diagnostics GmbH. Additional cross-reactivity studies were performed using 10 NP samples that tested positive by the BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Pathogen 2 panel for other coronaviruses defined as high-priority pathogens from the same genetic family by the FDA.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Data analyses, including statistics and plot generation, were performed using R programming language version 3.6.0.7 LOD was determined through a probit regression model using the glm function following CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Annapolis Junction, MD) EP17A2E Guidance with Application to Quantitative Molecular Measurement Procedures.8

Results

Validation of Assay

Limit of Detection

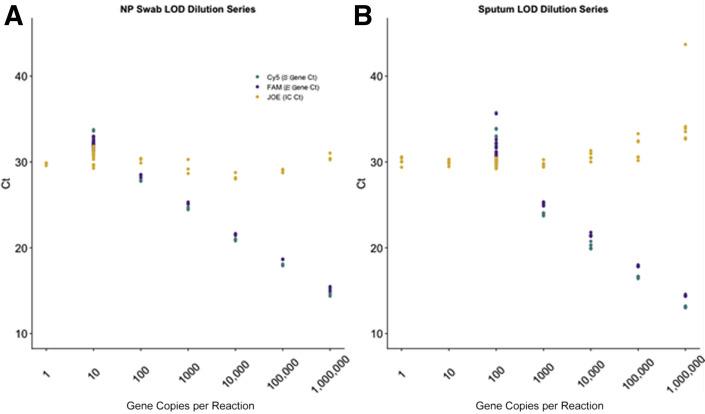

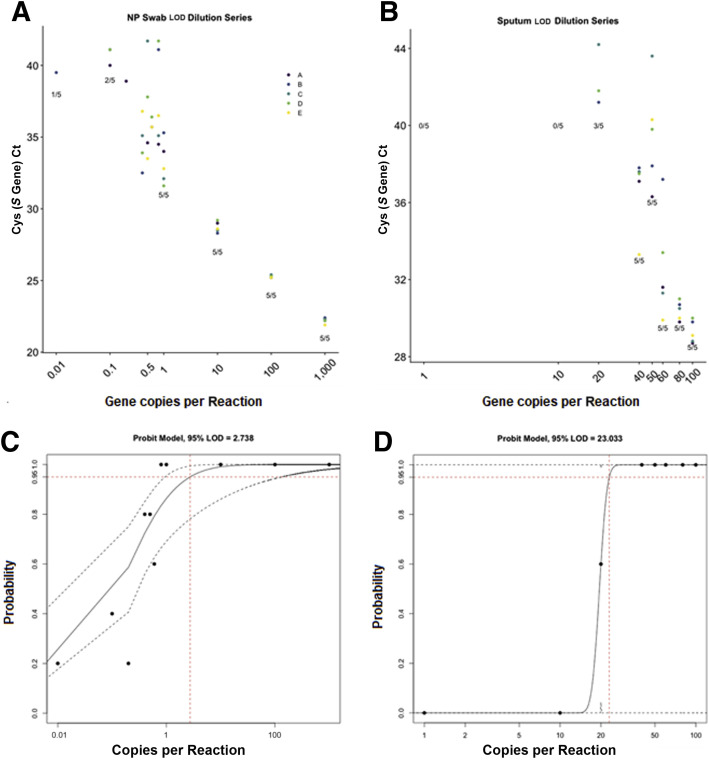

Dilution series studies on pooled negative NP specimens spiked with WRCEVA RNA reference material, with three replicates across a viral range of 1 gene copy per reaction to 1,000,000 gene copies per reaction (1 to 6 log10), demonstrated an accurate and linear response across five logs of detection for NP specimens and four logs of detection for sputum specimens (Table 1 and Figure 1 ). Probit analysis was applied to the NP data after an additional five replicates of testing were performed at 0.8, 0.6, 0.5, 0.4, and 0.2 gene copies per reaction, and narrowed the LOD to 2.7 gene copies per reaction at 95% detection rate (Figure 2 ). A similar LOD series and probit analysis were performed on sputum at 80, 60, 50, 40, and 20 gene copies per reaction, and showed a lower sensitivity with an LOD of 23.0 gene copies per reaction at 95% detection rate. All additional 20 of 20 NP and 23 of 23 sputum replicates tested at respective LODs resulted as positive.

Table 1.

Limit of Detection Studies Were Performed for NP and SPU Specimen Types with Three Replicates at Each Dilution

| Dilution | Gene copies per reaction | Run, n |

Detected, n |

Detected, % |

Mean Ct |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S gene |

E gene |

IC detected |

|||||||||||

| NP | SPU | NP | SPU | NP | SPU | NP | SPU | NP | SPU | NP | SPU | ||

| 1:10 | 106 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 14.6 | 13.1 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 30.6 | 33.0 |

| 1:102 | 105 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 18.0 | 16.5 | 18.7 | 17.9 | 29.0 | 30.4 |

| 1:103 | 104 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 20.9 | 19.9 | 21.6 | 21.4 | 28.3 | 30.8 |

| 1:104 | 103 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 24.6 | 23.8 | 25.2 | 25.3 | 29.4 | 29.7 |

| 1:105 | 102 | 3 | 26 | 3 | 26 | 100 | 100 | 27.9 | 31.1 | 28.4 | 31.0 | 30.2 | 29.8 |

| 1:106 | 10 | 23 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 32.3 | ND | 32.0 | ND | 30.8 | 29.7 |

| 1:107 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 29.8 | 29.8 |

An additional 20 (NP) and 23 (SPU) specimens were tested at the estimated limit of detection of 10 and 100 gene copies per reaction, respectively.

IC, internal control; ND, not detected; NP, nasopharyngeal viral transport media; SPU, sputum.

Figure 1.

Limit of detection (LOD) studies. Ct values for the LOD serial dilution study using World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses RNA reference material spiked in pooled negative nasopharyngeal (NP) specimen eluate (A) and sputum specimen eluate (B). Six 10-fold dilutions were performed, starting at 1,000,000 gene copies per reaction and ending at 1 gene copy per reaction. The apparent LOD was between 1 and 10 gene copies per reaction for NP specimens and between 10 and 100 gene copies per reaction for sputum specimens. IC, internal control.

Figure 2.

Limit of detection (LOD) of nasopharyngeal (NP) and sputum by probit analysis. Additional serial dilution studies were performed using World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses RNA reference material spiked in pooled negative NP specimen eluate (A) and sputum specimen eluate (B) to determine the LOD. Five replicates (A, B, C, D, and E) of six 10-fold dilutions were performed, starting at 1000 gene copies per reaction and ending at 0.1 gene copies per reaction, for NP specimens; and five replicates of three 10-fold dilutions were performed, starting at 100 gene copies per reaction and ending at 1 gene copy per reaction, for sputum specimens. An additional five replicates were performed at 0.8, 0.6, 0.5, 0.4, and 0.2 gene copies per reaction for NP specimens and 80, 60, 50, 40, and 20 gene copies per reaction for sputum specimens. Probit analysis showed LOD to be 2.7 gene copies per reaction for NP specimens (C) and 23.0 gene copies per reaction for sputum specimens (D). Red dashed lines represent copies/mL (x-axis) at 95% detection rate (y-axis).

Inclusivity and Specificity

The in silico analysis for inclusivity (altona Diagnostics GmbH) demonstrated 100% homology of the E and S gene forward and reverse primers and probes with 563 whole-genome SARS-CoV-2 sequences published in Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (https://www.gisaid.org, last accessed October 22, 2020) and National Center for Biotechnology Information as of March 16, 2020. In silico analysis for cross-reactivity demonstrated <80% homology of the primers and probes with the vast majority of 40 different pathogens (125 strains) tested. There was >80% homology between the E-gene forward primer and a strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae (81.82%); in the S-gene forward primer and strains of Legionella pneumophila subspecies Pascuellei strain (80.95%), Pneumocystis jirovecii (85.71%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (90.48%), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (85.71%); and in the S-gene reverse primer in strains of S. pneumoniae (80.95%), P. jirovecii (80.95%), and Candida albicans (80.95%). Cross-reactivity in rare cases of homology >80% was not a concern as only the forward or reverse primer, but never both primers, was affected, thus rendering amplification impossible. In addition, all 10 human coronavirus-positive samples [NL63 (n = 2), 229E (n = 2), OC43 (n = 4), and HKU1 (n = 2)] detected by BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Pathogen 2 panel tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 on the RealStar real-time RT-PCR assay.

Clinical Evaluation: Accuracy

Clinical evaluation studies resulted in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in all specimens contrived by spiking WRCEVA RNA reference material (n = 20) into pooled SARS-CoV-2–negative NP viral transport media or sputum eluates and all four positive patient samples tested by New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S1). The high-positive patient sample run at successive dilutions (n = 10) remained positive throughout the range of concentrations (1:2 to 1:1024; cycle threshold range, 22 to 31) (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). Similar clinical evaluation studies were performed for sputum specimens considered the most challenging sample type by the FDA, also with 100% concordance (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S2). All archived sputum and NP specimens that tested negative on the BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Pathogen 2 panel also tested negative on the SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR assay (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary Table of Accuracy Studies by Specimen Type

| Specimen type | Ct, mean (range) |

Tested (POS/NEG), N | Classification (POS/NEG), % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S gene | E gene | Internal control | |||

| NP swab∗ | 29.3 (20.6–37.2) | 29.2 (20.8–37.7) | 30.1 (28.6–30.8) | 30 | 100 |

| Sputum∗ | 24.1 (16.2–30.0) | 24.2 (17.0–29.2) | 30.2 (29.4–32.3) | 30 | 100 |

| NP swab† | 26.8 (20.6–37.2) | 27.4 (20.8–37.7) | 29.5 (28.8–30.1) | 4 | 100 |

| NP swab‡ | 24.0 (9.2–39.6) | 25.9 (10.2–37.7) | 29.2 (27.9–30.4) | 20/40 | 96/100 |

| Sputum§ | 16.0 (9.5–28.0) | 17.2 (10.8–28.9) | 30.2 (29.4–32.3) | 20/30 | 100 |

Clinical evaluation of the RealStar SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR assay using automated total nucleic acid extraction, followed by real-time RT-PCR targeting the E and S coronavirus genes. Mean and range of Ct values are shown for POS samples. The number of POS (either contrived through spiking RNA into pooled NEG RNA eluate or dilutions of authentic high-positive clinical or actual patient samples) and NEG specimens is also noted, along with the percentage of specimens that were correctly classified as POS or NEG.

NEG, negative; NP, nasopharyngeal; POS, positive.

NP and sputum SARS-CoV-2 contrived positive specimens generated with RNA dilutions.

NP swab clinical samples tested by New York State Department of Health as a part of the initial validation.

Authentic NP clinical samples assayed by reference tests after going live.

Sputum SARS-CoV-2–positive specimens generated with authentic lower respiratory tract samples diluted into NEG pooled sputum (2/20 real patient samples).

Additional accuracy studies performed with authentic patient specimens after testing went live demonstrated that 39 of the 40 (19/20 NP and 20 sputum specimens) SARS-CoV-2 specimens that tested positive with the orthogonal test also resulted positive with the altona RealStar real-time RT-PCR test. The mean Ct values (E gene/S gene) were 25.9/24.0 and 17.2/16.0 for the NP and sputum samples, respectively (Table 3 ). Of the 20 SARS-CoV-2–positive reference specimens, 11 (55%) tested were low positive samples with Ct values >30. The single discordant specimen tested indeterminate on the Roche test (pan-Sarbecovirus target only detected) and negative on the altona test, suggesting that the sample had low viral load. Orthogonal Ct values are not available for the NP and sputum specimens sent to New York State Department of Health and Associated Regional and University Pathologists, Inc. (ARUP Laboratories), Salt Lake City, Utah, respectively. The specificity was 100%.

Table 3.

Summary Table of Orthogonal Testing of Specimens on Different Specimen Types and Different Platforms

| Sample no. | Sample type | altona result | altona Ct values | Orthogonal platform | Orthogonal result | Orthogonal Ct values | Concordant (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NP swab | POS | 16.9/18.2 | cobas 6800 | POS | 19.5/19.7 | Y |

| 2 | NP swab | POS | 30.4/32.6 | cobas 6800 | POS | 31.8/34.7 | Y |

| 3 | NP swab | POS | 26.4/28.5 | cobas 6800 | POS | 29.5/30.8 | Y |

| 4 | NP swab | POS | 30.0/32.5 | cobas 6800 | POS | 31.1/32.5 | Y |

| 5 | NP swab | POS | 18.6/20.4 | cobas 6800 | POS | 23.6/24.5 | Y |

| 6 | NP swab | POS | 23.1/25.0 | cobas 6800 | POS | 26.6/27.4 | Y |

| 7 | NP swab | POS | 25.6/26.5 | cobas 6800 | POS | 27.4/28.1 | Y |

| 8 | NP swab | POS | 15.6/17.4 | cobas 6800 | POS | 19.4/19.7 | Y |

| 9 | NP swab | POS | 23.6/23.6 | cobas 6800 | POS | 25.3/26.2 | Y |

| 10 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | IND | –/33.4 | N |

| 11 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 12 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 13 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 14 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 15 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 16 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 17 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 18 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 19 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | cobas 6800 | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 20 | NP swab | POS | 30.3/31.2 | cobas 6800 | POS | 31.0/32.1 | Y |

| 21 | NP swab | POS | 9/2/10.2 | Cepheid | POS | 11.7/13.9 | Y |

| 22 | NP swab | POS | 15.4/16.3 | Cepheid | POS | 19.1/21.2 | Y |

| 23 | NP swab | POS | 21.8/22.8 | Cepheid | POS | 24.7/26.8 | Y |

| 24 | NP swab | POS | 30.9/31.3 | Cepheid | POS | 33.4/35.5 | Y |

| 25 | NP swab | POS | –/39.6 | Cepheid | POS | 33.3/35.8 | N |

| 26 | NP swab | POS | 29.4/29.5 | Cepheid | POS | 33.2/35.3 | Y |

| 28 | NP swab | POS | 26.0/26.8 | Cepheid | POS | 28.6/30.9 | Y |

| 29 | NP swab | POS | 32.1/32.3 | Cepheid | POS | 28.7/31.2 | Y |

| 30 | NP swab | POS | 27.0/27.7 | Cepheid | POS | 34.8/36.3 | Y |

| 27 | NP swab | NEG | –/– | Cepheid | NEG | –/– | Y |

| 31 | NP swab | POS | 23/23.2 | NYS-DOH | POS | N/A | |

| 32 | NP swab | POS | 20.6/20.8 | NYS-DOH | POS | N/A | |

| 33 | NP swab | POS | 26.3/27.7 | NYS-DOH | POS | N/A | |

| 34 | NP swab | POS | 37.2/37.7 | NYS-DOH | POS | N/A | |

| 35 | Sputum | POS | 9.5/10.8 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 36 | Sputum | POS | 9.7/11.0 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 37 | Sputum | POS | 10.5/11.9 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 38 | Sputum | POS | 11.9/13.4 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 39 | Sputum | POS | 13.6/14.9 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 40 | Sputum | POS | 13.7/15.0 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 41 | Sputum | POS | 14.6/15.9 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 42 | Sputum | POS | 15.9/17.2 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 43 | Sputum | POS | 16.1/17.4 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 44 | Sputum | POS | 17.1/18.4 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 45 | Sputum | POS | 18.9/20.1 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 46 | Sputum | POS | 20.7/21.8 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 47 | Sputum | POS | 15.5/16.9 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 48 | Sputum | POS | 16.2/17.4 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 49 | Sputum | POS | 17.2/18.5 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 50 | Sputum | POS | 18.6/19.9 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 51 | Sputum | POS | 17.8/19.2 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 52 | Sputum | POS | 18.8/20.1 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 53 | Sputum | POS | 13.5/15.2 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

| 54 | Sputum | POS | 28.0/28.9 | Hologic | POS | N/A | Y |

Thirty authentic patient NP swab specimens were orthogonally tested using US Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR assays on the Roche cobas 6800 or Cepheid GeneXpert platforms. The reported Ct values are from targets on the S gene/E gene (altona Diagnostics GmbH); target 1 SARS-CoV-2 specific/target 2 pan-Sarbecovirus (cobas 6800); and E gene/N2 gene (Cepheid). In addition, four NP specimens were tested by NYS-DOH EUA assay. Twenty sputum specimens were orthogonally tested at ARUP reference laboratory (Hologic SARS-CoV-2 assay on Panther System). Of 20 specimens, 18 were contrived positive samples obtained by spiking a range of concentrations (1:10 to 1:12,800) from a real patient lower respiratory tract sample confirmed to have SARS-CoV-2 infection by a SARS-CoV-2 EUA assay into pooled leftover negative sputum samples. Two of the samples (numbers 49 and 50) were authentic patient sputum samples.

IND, indeterminate; N, no; N/A, not applicable; NEG, negative; NP, nasopharyngeal; NYS-DOH, New York State Department of Health; POS, positive; Y, yes.

Clinical Cohort Characterization

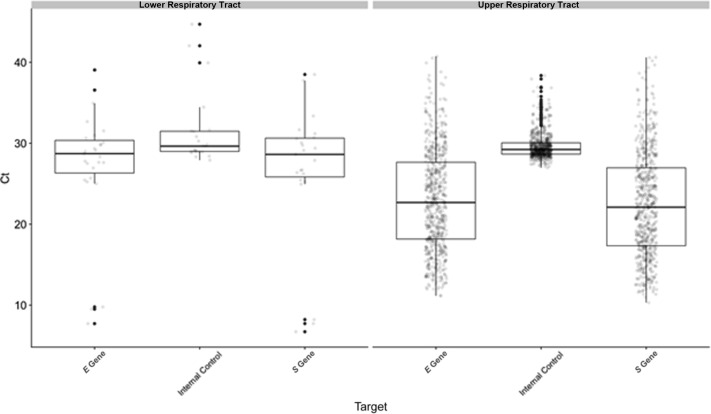

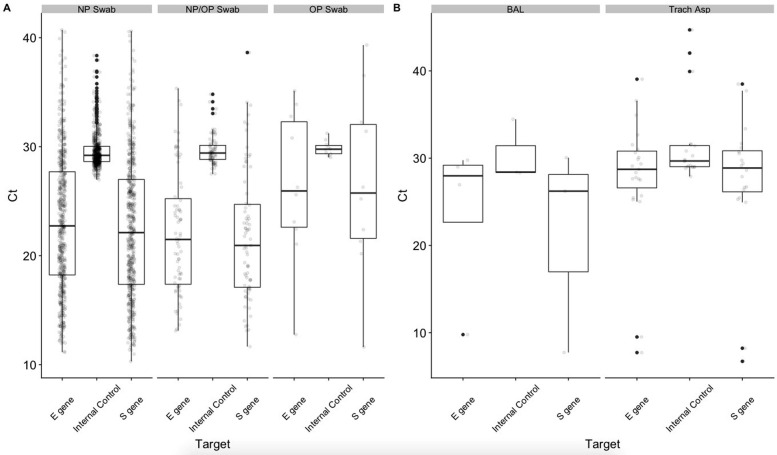

During the early days of the pandemic in New York City, we performed 1694 tests on 1354 NP specimens (41% positive), 32 oropharyngeal (OP) specimens (31% positive), and 308 combined NP + OP specimens (24% positive) from 1571 patients. Ct values were not significantly different for the E gene, S gene, and IC targets between positive NP, OP, or NP/OP samples (Supplemental Figure S2). The number of tests with indeterminate or B-betacoronavirus results were 5 and 4, respectively, all in NP swab samples. The mean Ct values for E gene, S gene, and IC targets in positive samples were 23.0 (range, 11.1 to 40.7), 22.5 (range, 10.3 to 40.6), and 29.6 (range, 27.0 to 38.4), respectively (Figure 3 ). Using Ct value of the S gene target as a surrogate for viral burden, the upper respiratory tract specimens could be classified into three groups: high (Ct < 20; n = 222, 34%), medium (Ct = 20 to 30; n = 335, 52%), and low (Ct > 30; n = 89, 13.8%).9 Over these initial 3 weeks of testing, >75% of positive samples could be classified as having medium to high viral burden.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Ct values for E gene, S gene, and internal control (IC) targets for all upper respiratory tract (URT) and lower respiratory tract (LRT) specimens with detected SARS-CoV-2. Mean Ct values between URT and LRT specimens were significantly different for the E gene (P = 0.006) and S gene (P = 0.03) but not the IC (P = 0.7), although the much smaller sample size for LRT is noted.

Of 135 patients with repeated testing, only 17 had different results on the second test, including 13 patients who first tested negative but subsequently tested positive and three patients who had virus detected in one specimen type (NP or OP) but not the other. Of the 13 patients who converted from negative to positive, 12 were initially tested at the emergency department (ED). On repeated testing performed within 3 days, five had low viral burden, five had medium viral burden, and two had high viral burden. The 13th patient tested negative as an inpatient and then with high viral burden as an inpatient 7 days later. Of note, although most of the patients in the data set presented with symptoms and were being tested for suspected infection with SARS-CoV-2, obstetrics and gynecology patients in the labor and delivery wards were being universally screened for SARS-CoV-2 as a preprocedural measure to determine if personal protective equipment would be required during interactions with health care workers. This group consisted of 102 female patients with a 7% positivity rate.

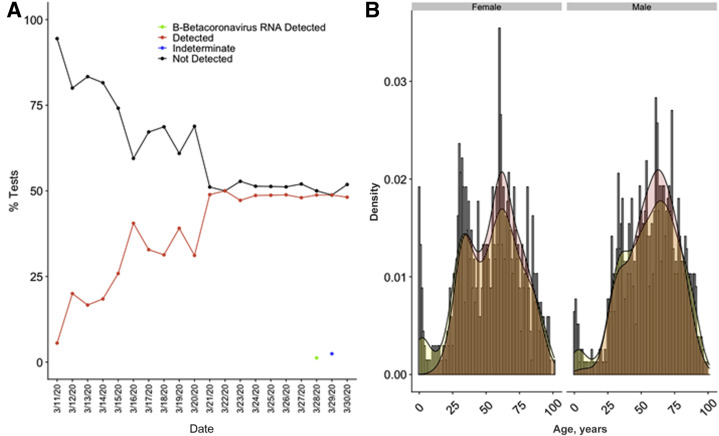

Means of turnaround times from test order to result and time in laboratory to result were 19.8 (range, 13.1 to 26.2) hours and 11.9 (range, 7.0 to 24.0) hours, respectively. The percentage of tests with detected SARS-CoV-2 increased as the weeks progressed, and settled at approximately 50% from March 21, 2020, to March 30, 2020 (Figure 4 A). Most of the samples were from the ED (n = 911), followed by inpatient wards (n = 492) and outpatient clinics (n = 113) (Table 4 ), and the highest positivity rate was in the ED, with 50% of patients with detected SARS-CoV-2 (P = 0.0005). There was a significant difference in the age (P = 0.0005) and sex (P = 0.005), with lower rates of detected virus in younger patients and female patients. Only 7% of patients aged ≤18 years had detected virus. Within female patients, older female patients (aged >55 years; n = 346) tested positive with greater frequency than younger female patients (aged <55 years; n = 438; P = 0.001), whereas this was not the case with male patients in the same age ranges (P = 0.09) (Figure 4B). This effect was diminished after removing patients from the labor and delivery ward (102 patients, 7% positive) who were being screened universally regardless of symptoms (P = 0.03). There was no significant difference in the frequency of positive tests in different race groups (P = 0.385).

Figure 4.

SARS-CoV-2 results by date and distribution by sex and age. A: Positivity of upper respiratory tract specimens tested by real-time RT-PCR at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center over the first 3 weeks of implementation. B: Age distribution histograms with overlays of normalized density curves corresponding to age distribution (yellow) and SARS-CoV-2 positivity (red) in tested patients by sex. Patients who were universally screened at labor and delivery were removed from this analysis.

Table 4.

Summary Table of Patient Characteristics

| Feature | Patients, n (total N = 1579) | Positive, % (total = 38%) | Negative, % (total = 62%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), years | 53.4 (0.1–120.3) | 57.5 (1.3–120.3) | 51.1 (0.1–97.5) | 0.0005 |

| 0–18 | 80 | 7 | 93 | |

| 19–35 | 295 | 30 | 70 | |

| 36–55 | 420 | 40 | 60 | |

| 56–85 | 656 | 47 | 53 | |

| >85 | 128 | 30 | 70 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 784 | 31 | 69 | |

| Male | 778 | 46 | 54 | 0.005 |

| Unspecified | 3 | 33 | 66 | |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 101 | 28 | 72 | |

| Black | 171 | 36 | 64 | |

| Declined | 173 | 40 | 60 | 0.385 |

| Other | 210 | 45 | 55 | |

| White | 488 | 32 | 68 | |

| Location | ||||

| Emergency | 911 | 50 | 50 | |

| Inpatient | 492 | 18 | 82 | 0.0005 |

| Outpatient | 113 | 35 | 65 |

For race, declined and other categories were not used when performing the χ2 test for significance. An additional 63 tests were performed at low numbers at several other locations; these were not included in the table. Significant values are in bold.

Lower respiratory tract specimens, including sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and tracheal aspirates, were accepted and tested using the altona RealStar SARS-CoV-2 test starting April 17, 2020. As of May 15, 2020, 10 sputum, 30 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and 101 tracheal aspirate specimens had been received from 115 patients, with 0%, 13%, and 23%, respectively, showing detectable SARS-CoV-2. Indeterminate results were reported for three tracheal aspirate samples. The mean Ct values for E gene, S gene, and IC targets in positive LRT samples (n = 27) were 27.3 (range, 7.7 to 39.1), 26.7 (range, 6.7 to 38.5), and 31.4 (range, 27.9 to 44.7), respectively (Figure 3). Ct values were not significantly different for the E gene, S gene, and IC targets between positive bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and tracheal aspirate samples (Supplemental Figure S1). The mean number of LRT samples received per day was 7 (range, 1 to 25), which was significantly lower compared with the number of URT specimens tested (mean, 85; range, 12 to 176). Given the small sample size, additional statistics on clinical cohort characteristics were not calculated for LRT specimens.

Discussion

Given the increased rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the lack of any commercially available tests, the FDA opened a pathway on February 29, 2020, that allowed laboratories to implement laboratory-developed tests to meet this diagnostic need. Prompt and rapid implementation of a reliable clinical test was an important goal, particularly in the early phase of the pandemic when limiting the spread of the infection was critical. altona Diagnostics GmbH launched the RealStar SARS-CoV-2 research use only assay as soon as the disease spread to Europe on February 20, 2020.10 The reagents were designed as a dual-target assay, allowing rapid detection of all lineage B-betacoronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2–specific RNA in a single reaction. Overall, the test was simple and easy to automate, with a turnaround time comparable to other RT-PCR methods.10, 11, 12 Laboratories were also able to use the reagents with a wide range of different extraction and real-time thermocycler instruments, allowing for greater flexibility in implementation.10, 11, 12 Furthermore, the open access platform allowed for greater flexibility compared with other commercial EUA tests in that rapid validation of sample types other than NP could be performed.

Accuracy studies of NP and sputum samples in our laboratory showed excellent overall agreement between the expected and observed results for contrived clinical samples and various patient specimens tested by orthogonal measures. Using this assay, we were able to detect all of the samples within the reportable Ct range (Ct ≤ 32). The reference methods (Roche and Cepheid) showed a slightly better sensitivity compared with the altona test, which can be explained, at least in part, by the small amount of initial sample volume (200 μL) used for testing compared with the amount required for the Roche 6800 (600 μL) and Cepheid (350 μL) tests.9

A highly sensitive test is crucial for the detection and identification of SARS-CoV-2 in individuals exhibiting signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection to allow early initiation of therapy. The LODs for the NP and sputum samples were 2.7 and 23.0 gene copies per reaction, respectively, suggesting a greater analytical sensitivity for the NP specimens compared with sputum. Overall, the analytical sensitivity of this assay by specimen type is slightly higher compared with the LODs reported in the literature by other similar studies.10, 11, 12 This may be explained by different extraction methods across studies, sample types evaluated, and the more precise probit analysis performed in our study. The discrepancy in the LOD between the two sample types is mainly attributed to the high viscosity of sputum, possibly impairing efficacy of nucleic acid extraction.13 Of note, although the analytical sensitivity was lower in sputum samples, LRT samples were more likely to test positive for the virus compared with URT and other sample types in COVID-19 patients.14 On the basis of these favorable validation results, routine SARS-CoV-2 testing with the RealStar SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR assay was initiated on March 11, 2020. Given the FDA-EUA governance and availability of WRCEVA SARS-CoV-2 control material, we were able to complete the validation process within a week, followed by a successful go-live testing day. Comparable evaluation studies, given the regulatory requirements, can take months to achieve.

A total of 1694 URT (40% positive) and 141 LRT (25% positive) specimens from 1571 and 115 patients, respectively, were tested. The lower number of LRT compared with URT specimens reflects hospital policy that restricted LRT testing to intubated patients who needed clearance of isolation (two negative NP swabs plus one negative LRT specimen) or to patients with high suspicion for COVID-19 with repeated negative testing by RT-PCR (two negative NP swabs).

In the cohort of patients tested over 3 weeks by our assay, positive results were seen more frequently in older males compared with younger and female patients, which has been supported by several studies.15 , 16 Post-menopausal women have been reported to have a greater risk of hospitalization compared with nonmenopausal women, an effect that has been attributed to the potential protective effect of estrogen.17 In this study, older women were more likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared with younger female patients. However, the difference in detection rate between older and younger women was diminished after removing obstetrics patients screened universally regardless of symptoms, highlighting the importance of restricting comparisons of positivity rates to groups of patients subjected to similar selection criteria and warranting the importance of carefully designed studies.

Among the obstetrics patients, only 7% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, which is similar to the prevalence (13.5%) obtained for women admitted at delivery at other NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital campuses.18 No differences in the number of positive tests were seen by race, but this was early in the epidemic in New York City. The ED likely had more positive tests because patients tend to be more acutely symptomatic there compared with ambulatory clinics. The percentage of positive tests increased steadily and settled at around 50% at 3 weeks into the epidemic, with later testing on other platforms showing daily positivity rates as high as 75% to 80% as the epidemic reached its peak in specific boroughs (H. Rennert, unpublished data). In this study, 13 patients tested positive after initial negative results in the ED, suggesting they had sufficient symptoms to warrant inpatient admission despite negative testing. This conversion may be because of increased viral burden on subsequent days after infection or better specimen sampling.19

In summary, we have described the clinical development and implementation of an FDA EUA laboratory-validated real-time RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in our academic institution, providing a road map to assist others in establishing similar tests. We also detailed the clinical and testing characteristics of the first cohort of COVID-19 patients admitted to our institution during the early days of the viral outbreak in New York City.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the dedicated medical technologists and health care professionals who performed and assisted in testing at the clinical laboratories of NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital–Weill Cornell Medicine; Dr. Scott C. Weaver (World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses) for providing viral RNA control material; and altona Diagnostics GmbH for prompt supply of reagents and support.

Footnotes

Supported by institutional funding.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2020.10.019.

Supplemental Data

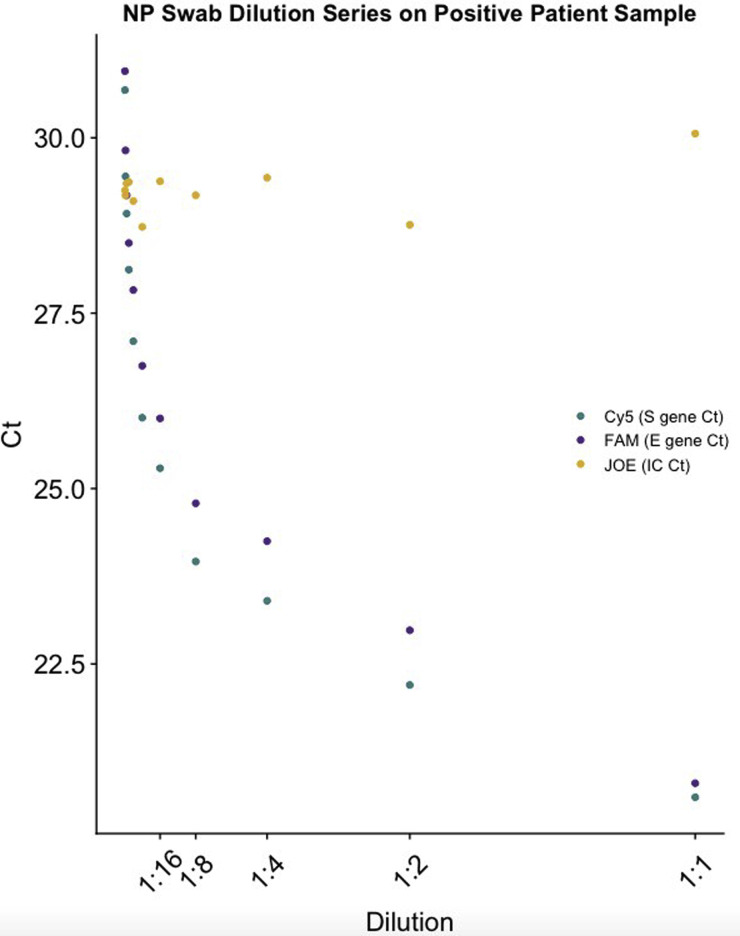

Supplemental Figure S1.

Ten twofold dilutions from 1:1 to 1:1024 (Ct range, 22 to 31) were performed for patient New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2, who had a high-positive nasopharyngeal (NP) swab specimen. See Supplemental Table S1 for Ct values at all dilution points. All dilutions of the specimen had detectable S gene, E gene, and internal control (IC) targets. FAM, fluorescein; JOE, 6-Carboxy-4’,5’-Dichloro-2’, 7’-Dimethoxyfluorescein; Cy5,cyanine 5 dye.

Supplemental Figure S2.

Ct values for S gene, E gene, and internal control (IC) are plotted for the different sample types. A: Nasopharyngeal (NP) or oropharyngeal (OP) swabs were tested from March 11, 2020, to March 13, 2020; NP or NP/OP swab specimens were tested from March 11, 2020, to March 16, 2020; and only NP swab specimens were tested from March 16, 2020, to March 30, 2020. There was no significant difference in Ct values for the S gene (P = 0.77), E gene (P = 0.096), or IC (P = 0.88) targets between these upper respiratory tract sample types. B: Lower respiratory tract specimens were tested starting April 17, 2020, and results include specimens up until May 15, 2020. There was no significant difference in Ct values for the S gene (P = 0.32), E gene (P = 0.41), or IC (P = 0.32) targets between bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid or tracheal aspirate (Trach Asp) sample types (no sputum samples were positive).

References

- 1.Lorusso A., Calistri P., Petrini A., Savini G., Decaro N. Novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic: a veterinary perspective. Vet Ital. 2020;56:5–10. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.2173.11599.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei X., Li X., Cui J. Evolutionary perspectives on novel coronaviruses identified in pneumonia cases in China. Natl Sci Rev. 2020;7:239–242. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L., Li Q., Zheng D., Jiang H., Wei Y., Zou L., Feng L., Xiong G., Sun G., Wang H., Zhao Y., Qiao J. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., Schenck E.J., Chen R., Jabri A., Satlin M.J., Campion T.R., Jr., Nahid M., Ringel J.B., Hoffman K.L., Alshak M.N., Li H.A., Wehmeyer G.T., Rajan M., Reshetnyak E., Hupert N., Horn E.M., Martinez F.J., Gulick R.M., Safford M.M. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell S.L., St. George K., Rhoads D.D., Butler-Wu S.M., Dharmarha V., McNult P., Miller M.B. Understanding, verifying, and implementing emergency use authorization molecular diagnostics for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00796-20. e00796-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Team R Core . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F. R Function Library; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2016. CLSI EP17A2E Guidance with Application to Quantitative Molecular Measurement Procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craney A.R., Velu P., Satlin M.J., Fauntleroy K.A., Callan K., Robertson A., La Spina M., Lei B., Chen A., Alston T., Rozman A., Loda M., Rennert H., Cushing M., Westblade L.F. Comparison of two high-throughput reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction systems for the detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e00890-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00890-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konrad R., Eberle U., Dangel A., Treis B., Berger A., Bengs K., Fingerle V., Liebl B., Ackermann N., Sing A. Rapid establishment of laboratory diagnostics for the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in Bavaria, Germany, February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000173. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., Bleicker T., Brunink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., Mulders D.G., Haagmans B.L., van der Veer B., van den Brink S., Wijsman L., Goderski G., Romette J.L., Ellis J., Zambon M., Peiris M., Goossens H., Reusken C., Koopmans M.P., Drosten C. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uhteg K., Jarrett J., Richards M., Howard C., Morehead E., Geahr M., Gluck L., Hanlon A., Ellis B., Kaur H., Simner P., Carroll K.C., Mostafa H.H. Comparing the analytical performance of three SARS-CoV-2 molecular diagnostic assays. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104384. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bordi L., Piralla A., Lalle E., Giardina F., Colavita F., Tallarita M., Sberna G., Novazzi F., Meschi S., Castilletti C., Brisci A., Minnucci G., Tettamanzi V., Baldanti F., Capobianchi M.R. Rapid and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using the Simplexa COVID-19 direct assay. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104416. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;23:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian S., Hu N., Lou J., Chen K., Kang X., Xiang Z., Chen H., Wang D., Liu N., Liu D., Chen G., Zhang Y., Li D., Li J., Lian H., Niu S., Zhang L., Zhang J. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Infect. 2020;80:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai C.C., Liu Y.H., Wang C.Y., Wang Y.H., Hsueh S.C., Yen M.Y., Ko W.C., Hsueh P.R. Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): facts and myths. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding T., Zhang J., Wang T., Cui P., Chen Z., Jiang J., Zhou S., Dai J., Wang B., Yuan S., Ma W., Ma L., Rong Y., Chang J., Miao X., Ma X., Wang S. A multi-hospital study in Wuhan, China: protective effects of non-menopause and female hormones on SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv. 2020 [Epub] doi:10.1101/2020.03.26.20043943. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutton D., Fuchs K., D'Alton M., Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinloch N., Ritchie G., Chanson J.B., Dong Wi, Dong We, Lawson T., Jones R.B., Montaner J.S.G., Leung V., Romney M.G., Stefanovic A., Matic N., Lowe C.F., Brumme Z. Suboptimal biological sampling as a probable cause of false-negative COVID-19 diagnostic test results. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:899–902. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.