Abstract

Philadelphia-chromosome negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by an increased risk of thrombosis and progression to acute myeloid leukemia. MPN are associated with driver mutations in JAK2, CALR and MPL which are crucial for the diagnosis and lead to a constitutive activation of the JAK-STAT signaling, independent of cytokine regulation. Moreover, most patients have concomitant mutations in genes involved in DNA methylation, chromatin modification, messenger RNA splicing, transcription regulation and signal transduction. These additional mutations may arise before, in the context of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), or after the acquisition of the driver mutation. The clinical phenotype of MPN results from complex interactions between mutations and host factors. The increased application of next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques to a large series of patients with MPN has expanded the knowledge of mutational landscape and contributed to define the clinical significance of mutations. This molecular information is being increasingly used to refine diagnosis, risk stratification, monitoring of residual disease and response to treatment. ASXL1, SRSF2, EZH2, IDH1/IDH2 and U2AF1 mutations are associated with a more advanced disease and reduced overall survival in primary myelofibrosis (PMF), whereas spliceosome mutations in Polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thrombocythemia (ET) adversely affect both overall (SF3B1, SRSF2 in ET and SRSF2 in PV) and myelofibrosis-free (U2AF1, SF3B1 in ET) survival. This review discusses current knowledge of the molecular landscape of MPN, and how the availability of those molecular information may impact patient management.

Keywords: myeloproliferative neoplasms, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, myelofibrosis, JAK-STAT pathway, gene mutations

Introduction

The classic Philadelphia-chromosome negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell diseases characterized by overproduction of one or more types of cells of the myeloid lineage.1 According to the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, MPN include Polycythemia Vera (PV), Essential Thrombocythemia (ET) and myelofibrosis, which may be classified as primary (PMF) or secondary to PV and ET (post-PV-MF and post-ET-MF).2 This classification has been updated with the introduction of pre-fibrotic/early PMF, distinguishable from ET on the basis of bone marrow (BM) morphology, that has a higher tendency to develop overt MF and is characterized by a reduced overall survival compared to true ET3 (Table 1). The diagnostic criteria of PPV-MF and PET-MF were developed by the International Working Group for MPN Research and Treatment – IWG-MRT4,5 (Table 2). All MPN can transform into secondary acute myeloid leukemia, referred to as MPN-blast phase (BP), which is typically refractory to conventional chemotherapy and has a poor prognosis.6 The 15-year risk of leukemia is estimated at 2.1% to 5.3% for ET, 5.5% to 18.7% for PV and more than 20% for PMF whereas fibrotic progression rates of ET and PV, during a similar time interval, are estimated at 4% to 11% and 6% to 14%, respectively.7

Table 1.

Summary of WHO Criteria for MPN

| Polycythemia Vera | Essential Thrombocythemia | Prefibrotic Myelofibrosis | Primary Myelofibrosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major criteria | |||

|

|

|

|

| Minor criterion | Minor criteria (confirmed in two consecutive determinations) | ||

|

|

|

|

| Patients must meet all three major criteria or the first two major criteria and the minor criteriona | Patients must meet all four major criteria or the first three major criteria and the minor criterion | Patients must meet all 3 major criteria, and at least 1 minor criterion. | Patients must meet all 3 major criteria, and at least 1 minor criterion. |

Notes: aCriterion number 2 (BM biopsy) may not be required in cases with hemoglobin levels > 18.5 g/dL in men (hematocrit > 55.5%) or > 16.5 g/dL in women (hematocrit > 49.5%), if major criterion 3 and the minor criterion are present. bFibrosis secondary to infection, autoimmune disorder or other chronic inflammatory conditions, lymphoid neoplasm, metastatic malignancy, or toxic myelopathies. Data from Arber et al.3

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; HGB, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; BM, bone marrow; EPO, erythropoietin; LDH, serum lactate dehydrogenase.

Table 2.

Summary of IWG Criteria for PPV-MF and PET-MF

| Post-Polycythemia Vera Myelofibrosis (PPV-MF) |

Post-Essential Thrombocythemia Myelofibrosis (PET-MF) |

|---|---|

| Required criteria | |

|

|

| Additional criteria (two required) | |

|

|

Notes: aConstitutional symptoms include > 10% of weight loss in six months, night sweats and unexplained fever (> 37.5 °C). Data from Barosi et al.5

Abbreviations: IWG, International Working Group; WHO, World Health Organization; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

In Europe, the incidence of MPN varies from 0.4 to 2.8/100.000 in PV, 0.38 to 1.7/100.000 in ET, and 0.1 to 1/100.000 in PMF, while prevalence remains difficult to determine.8 MPN have clinical heterogenicity, with some patients having normal lifespan and others developing disease progression or life-threatening complications. Median survival is around 20 years for ET, 14 years for PV and 6 years for PMF; the corresponding values for patients younger than 60 years are 33, 24 and 15 years.9 PV and ET are characterized by cardiovascular events, mainly thrombosis and less frequently hemorrhage, a varying burden of symptoms, and an intrinsic risk of evolution to MF or BP. Treatment is mainly focused on the reduction of thrombosis risk, control of myeloproliferation, improvement of symptoms, and management of related complications. MF is a protean disease with variable levels of cytopenias, constitutional symptoms, often as a result of a hypercytokinaemia, extramedullary hematopoiesis and marrow fibrosis. Splenomegaly is present at the varying extent and can cause abdominal pain, early satiety, splenic infarction, and portal hypertension. Progressive MF can be associated with marrow failure and evolution to BP. Treatment, both standard and experimental, is variably effective in reducing myeloproliferation, splenomegaly, constitutional symptoms and improving the quality of life. However, some patients do not respond to treatment, and others become resistant. Nowadays, the only curative approach is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) which has a high mortality risk and is often not considered for older patients and those with comorbidities.

Mutational Landscape of MPN

Driver Mutations: JAK2, CALR and MPL

Constitutive activation of the JAK-STAT pathway is the hallmark of MPN. Mutations in JAK2, CALR and MPL are referred as “driver mutations”, based on their role in driving the MPN phenotype and are crucial for the diagnosis along with clinical and histopathological features. These three mutations are mutually exclusive, but cases of co-occurrence have been reported.10,11 Patients with features of MPN without any one of these mutations are classified as “triple negative”. Two types of JAK2 mutations are described in MPN. The first, discovered in 2005, is a valine to phenylalanine substitution at amino acid position 617 (V617F) in exon 14;12–15 the second, described in 2007, comprises many different mutations, particularly in-frame insertions or deletions, in exon 12 of JAK2.16,17 JAK2V617F is detected in approximately 95% of PV cases and 50–60% of ET and PMF. Conversely, JAK2 exon 12 mutations are extremely rare and are found exclusively in 2–3% of all PV patients, that are negative for JAK2V617F. JAK2V617F can drive all the different MPN phenotypes through ligand-independent activation of receptors for erythropoietin (EPO), thrombopoietin (TPO) and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), resulting in the expansion of erythroid, megakaryocytic and granulocytic lineages, respectively.18–20 In comparison to V617F mutation, patients with exon-12 mutations predominantly activate EPO receptor and are characterized by erythroid‐dominant myeloproliferation with lower leukocytosis and thrombocytosis, and younger age at diagnosis.21,22 The different phenotypes of JAK2V617F mutated MPN may reflect different host characteristics, different development stages at which the mutation arises, the presence and order of other molecular variants and characteristics of bone marrow microenvironment. The timing of mutation acquisition may affect the clinical phenotype with the “JAK2-first” more commonly occurring in PV, and “TET2-first” more commonly in ET.23 Similar to TET2, patients are more likely to present with PV when JAK2V617F is acquired before DNMT3A mutation, compared with patients who first acquired DNMT3A mutation and more currently have an ET phenotype.24 Moreover, allele burden has been associated with different phenotypes; homozygous mutation and higher mutant allele burden (>50%) have been described in most PV patients, and associated with increased risk of thrombosis and fibrotic evolution, whereas ET patients tend to have a lower burden.25

CALR encodes for calreticulin, a 46-kDa chaperone protein located in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen, which has a key role in the maintenance of calcium homeostasis and protein folding.26 To date, more than 50 different CALR mutations, all in exon 9, have been described in 20–25% of ET and 25–30% of PMF cases, but not in PV patients.27,28 Two CALR mutations account for approximately 80% of all the subtypes; type-1 is a 52-bp deletion (c.1092_1143del p.L367fs*46) and type-2 is a 5-bp insertion (c.1154_1155insTTGTC p.K385fs*47), resulting in mutant proteins that loss the ER-retention motif (KDEL) at the C-terminus. All the other CALR mutations are grouped as type 1-like and type 2-like in relation to their corresponding structural similarities and effect on C-terminal. CALR subtypes are associated with many clinical phenotypes and outcomes in MPN. In PMF, type-1 CALR mutations are more prevalent than type-2 (70% vs 13%), while in ET they are more balanced (51% vs 39%).29 Moreover, type-1 mutations have been associated with a significantly higher risk of myelofibrotic transformation in ET.30 In a large series of ET patients both CALR variants, compared to mutant JAK2, were associated with higher platelet and lower hemoglobin and leukocyte counts.31 The role of mutated CALR in driving the clinical phenotype of MPN has yet to be fully elucidated. Recently, some studies demonstrated that mutant CALR binds to MPL within the ER, resulting in the constitutive activation of MPL, and consequently of the JAK-STAT signaling.32–35 Moreover, MPL-CALR complex has been detected on the cell surface and this translocation appears essential for the oncogenic activity,36,37 raising the prospect for future target therapies.

MPL is the cell surface receptor for TPO, which regulates megakaryopoiesis and platelet production through the JAK-STAT signaling and is also expressed on the hematopoietic stem cells. MPL mutants largely account for the marked thrombocytosis in patients with ET and PMF.38 MPL gain of function mutations of tryptophan 515 (W515) in exon 10, located in the transmembrane domain of the protein, are described in 3–8% of ET and PMF cases.39 The most common mutations are W515L and W515K. Other rare mutations at the same position, as W515R, W515A and W515G have been reported.40 Although the MPLS505N allele was identified initially as an inherited mutation in familial thrombocythemia,41 it can also be acquired as a somatic event in ET patients. Moreover, in a recent report, several second-site mutations that enhance S505N-driven activation were described.42

Triple-Negative MPN

Mutations of JAK2, CALR, and MPL, account for over 90% of MPN cases and are usually mutually exclusive. However, in approximately 15% of patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) and 8–10% of primary myelofibrosis (PMF), driver mutations are absent and these patients are referred as triple‐negative (TN).43 A small number of TN MPN patients acquired JAK2 mutations after some time from diagnosis; this acquisition may reflect the clonal expansion of a very-low burden mutation or false negative in initial testing. Approximately 10% of TN ET and PMF patients may have mutations outside of MPL exon 10 and JAK2 exon 14. These “non-canonical” MPL mutations include T119I, S204F/P and E230G in the extracellular domain and Y591D/N in the intracellular domain.44 Non-canonical JAK2 mutations include V625F, F556V, R683G and E627A.45 As demonstrated in functional studies, most of these rare variants led to constitutive activation of the JAK-STAT signaling.44,45 Some are somatic mutations, while others represent germline variants, with the possibility that many patients may have a form of non-clonal erythrocytosis or thrombocytosis with variable family penetrance.

Additional Mutations in Myeloid Genes

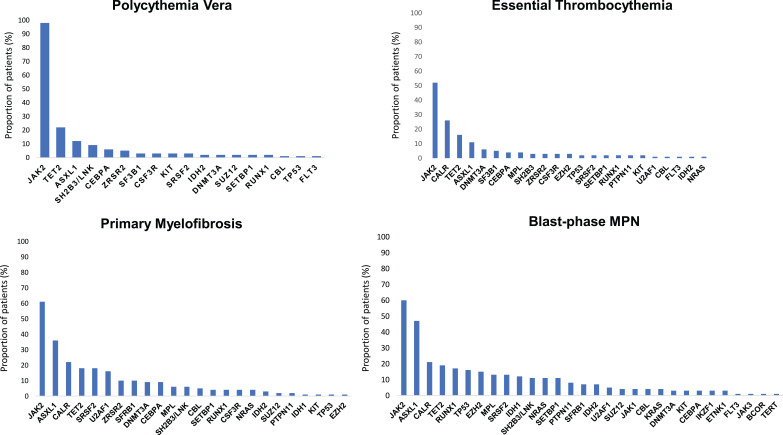

High-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses have discovered a remarkable number of additional somatic mutations with prognostic and therapeutic relevance, particularly in PMF (Figure 1). More than 50% of MPN patients harbor additional mutations.46 These mutations are not restricted to MPN but are shared by other myeloid malignancies including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). They are more frequent with increasing age, not only in patients with hematologic neoplasms but also in healthy individuals in the context of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), which is defined as a cell population associated with a recognized hematological neoplasm driver mutation at a variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥2%, in the absence of severe cytopenias or a WHO-defined disorder. Some studies demonstrated that CHIP predisposes to the development of a hematological malignancy and cardiovascular death, the latter probably resulting from proinflammatory interactions between endothelium and macrophages derived from clonal monocytes.47 Affected genes are involved in DNA methylation (TET2, DNMT3A, IDH1 and IDH2), histone modification (ASXL1, EZH2), mRNA splicing (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1 and ZRSR2), signaling pathways (LNK/SH2B3, CBL, NRAS, KRAS and PTPN11), transcription factors (RUNX1, NFE2, PPM1D and TP53). In Table 3 main clinical features associated with recurrent additional mutations in MPN are summarized.

Figure 1.

Mutational landscape of MPN. Results from a target next-generation sequencing analyses in patients with polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, primary myelofibrosis and blast-phase MPN. The graphs show the proportion of patients for each corresponding mutation (both driver JAK2, CALR and MPL mutations and additional somatic mutations). Data from Tefferi et al54,60 and Lasho et al.108

Table 3.

Recurrent Additional Mutations in MPN

| Gene | Function/Mutation Types | Frequency (%) | Prognostic Impact on MPN | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | ET | MF | BP | |||||

| DNA methylation | ||||||||

| TET2 | Demethylation through oxidation of 5-methyl-cytosine (5-mc) into 5-hydroxymetylcytosine (5-hmc), an important process in stem cell gene regulation. Heterozygous and homozygous loss-of-function mutations in catalytic domain are described. | 10–20 | 10–15 | 20 | 25 | No defined impact on survival and thrombosis | [23,54,60,108] | |

| DNMT3A | Principal factor of DNA/histone methylation in blood stem cells. Nonsense/frameshift and missense mutations are described, resulting in reduce methyltransferase activity. | 5 | 5 | 5–15 | 20 | Detrimental effect in MF and inferior overall survival. | [54,60,108] | |

| IDH1/2 | Mutant proteins acquired the ability to convert alpha-ketoglutarate (a-KG) to 2 -hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), favouring leukemogenesis through epigenetic dysregulation of some genes. Mutations are heterozygous and occur mostly as point missense mutations at residues R132 in IDH1 and R140 or R172 in IDH2. | <2 | <2 | 3–5 | 15–25 | Detrimental effect in MF and inferior overall survival | [66,109] | |

| Histone modification | ||||||||

| ASXL1 | DNA methylation and transcription repression. Mutations are heterozygous nonsense/frameshift and occur mostly in exon 12 | 1–10 | 5–10 | 18–35 | 20–40 | Risk of fibrotic and leukemic transformation | [54,61,62,66,85,110,111] | |

| EZH2 | Histone methyltransferase and transcription repression. Heterozygous and homozygous loss-of-function mutations mostly in SET2 domain are described. | 1–3 | 0–3 | 0–9 | 13–15 | Risk of fibrotic and leukemic transformation | [112,113] | |

| mRNA splicing | ||||||||

| SF3B1 | Subunit 1 of the splicing factor 3b protein complex. Heterozygous missense mutations in exons 14–16, hotspot K700E is the most frequent. | 5 | 3 | 10 | 4–7 | Increased risk of fibrotic transformation | [54] | |

| SRSF2 | Necessary for the splicing of pre-mRNA. It is required for formation of the earliest ATP-dependent splicing complex and interacts with spliceosomal components bound to both the 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-splice sites during spliceosome assembly. Heterozygous mutations and small in-frame deletions around hotspot P95 are frequent. | <3 | <3 | 10–20 | 10–20 | Increased risk of leukemic transformation and reduced overall survival in MPN | [61,114–117] | |

| U2AF1 | U2 Auxiliary factor 1, comprising a large and a small subunit, is a non-snRNP (small nuclear ribonucleoprotein) protein required for the binding of U2 snRNP to the pre-mRNA branch site. Heterozygous missense mutations around hotspot S34 and Q157 are described. | 1–2 | 1–2 | 16 | 6 | Associated with disease progression and reduced overall survival in MF | [60,69,118] | |

| ZRSR2 | Protein associates with the U2 auxiliary factor heterodimer, which is required for the recognition of a functional 3ʹ splice site in pre-mRNA splicing. Frameshift/nonsense and missense mutations are described. | 1–2 | 1–2 | 10 | 5 | No defined impact on survival and thrombosis | [60,108] | |

| Signalling | ||||||||

| LNK/SH2B3 | Adaptor protein that inhibits signalling through cytokine and tyrosine kinase receptors, including JAK2. Mostly heterozygous missense mutations are described as somatic or germline, also in the context of familial cases of MPN. | 1–3 | 0–5 | 0–6 | 10 | No defined impact on survival and thrombosis. | [54,60,108,119–121] | |

| CBL | Mutations lead to increased STAT5 phosphorylation, cytokine hypersensitivity and cell proliferation; mostly homozygous missense substitutions. | <1 | 0–2 | 0–6 | 4 | Reduced overall survival in MF, resistance to JAKi | [60,108,122,123] | |

| NRAS/KRAS | Heterozygous missense mutations, particularly in codons 12, 13 and 61 led to a constitutive activation of growth signalling. | <1 | <1 | 3–4 | 7–15 | Reduced overall survival in MF, resistance to JAKi | [60,108,123,124] | |

| PTPN11 | Missense mutations in Src-homology 2 (N-SH2) and phosphotyrosine phosphatase (PTP) domains | <1 | <1 | 1 | 2–5 | Reduced overall survival in BP | [108] | |

| Transcription factors | ||||||||

| RUNX1 | Element of core bonding factor (CBF) heterodimer. Essential role in normal hematopoiesis. Missense, frameshift, and nonsense mutations causing loss-of-function. | <1 | <1 | 3–4 | 4–13 | Reduced overall survival in BP | [46] | |

| NFE2 | Mostly heterozygous frameshift mutations, leading to over-expression of wild-type protein functions. | 2–3 | 1 | 1–5 | 11–35 | No defined impact on survival or thrombosis | [125,126] | |

| PPM1D | Encodes a protein phosphatase that regulates the DNA damage response pathway by inhibiting p53 and other tumor-suppressors through dephosphorylation. | 2 | 1 | 1 | NA | No defined impact on survival or thrombosis | [108,127] | |

| TP53 | Encodes a tumor suppressor protein that responds to different cellular stresses to regulate expression of target genes, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Mostly missense mutations. | 1 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 11–35 | Associated with disease progression and reduced overall survival in all MPN | [60,108] | |

Abbreviations: PV, polycythemia vera; ET, essential thrombocythemia; MF, myelofibrosis; BP, blast-phase; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; JAKi, JAK inhibitors.

Clinical and Molecular-Integrated Prognostic Scores in MPN

Polycythemia Vera and Essential Thrombocythemia

For many years, thrombosis prediction in PV and ET relied on clinical variables only (age >60 years and prior history of thrombosis). Recent findings, however, have highlighted the contribution of genetic information. While patients with PV almost exclusively carry mutations in JAK2, the effect of mutated JAK2 in patients with ET was compared with JAK2 wild-type ones, highlighting that JAK2 wild-type patients showed a lower risk of thrombosis.48,49 In 2012, these studies led to the development of a three-tiered International Prognostic Scoring of thrombosis in ET (IPSET-thrombosis) with the addition of JAK2 status and cardiovascular risk factors (2 and 1 point, respectively) to age and prior thrombosis (1 point each).50 The score was re-analyzed leading to a refined 4-tiered version, which excluded cardiovascular risk factors evaluation,51 (Table 4) and was validated in a large independent cohort of patients.52 Because of their very low-risk of thrombosis, ET CALR mutated young patients without a prior history of thrombosis and cardiovascular risk factors may not require aspirin. In these patients, as reported, aspirin might rather increase the risk of bleeding without improving the intrinsically low thrombotic risk.51,53

Table 4.

Revised IPSET-Thrombosis Model for Essential Thrombocythemia

| Variables | Risk Categories | Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≤ 60 years old Prior thrombosis JAK2V617F mutation |

Very low (Age ≤ 60 years, JAK2 wild type, no prior thrombosis) | Management of CV risk factors, observation or low dose aspirin, unless contraindicateda |

| Low (Age ≤ 60 years, JAK2V617F positive, no prior thrombosis) | Management of CV risk factors and low dose aspirin unless contraindicateda. Higher dose aspirin may be used if CV risk factors present. | |

| Intermediate (age > 60 years, JAK2 wild type, no prior thrombosis) | Management of CV risk factors and cytoreductive therapy plus low-dose aspirin, unless contraindicateda. Higher dose aspirin without cytoreductive therapy if no CV risk factors. | |

| High (age > 60 years and JAK2V617F positive, or prior thrombosis) | Management of CV risk factors and cytoreductive therapy plus low-dose aspirin |

Notes: aAspirin is contraindicated in the presence of acquired von Willebrand’s disease or active major bleedings. In bold molecular variable. Data from Barbui et al.51

Abbreviations: IPSET, International Prognostic Score for Essential Thrombocythemia; CV, cardiovascular.

Recently, the prognostic relevance of somatic mutations was investigated in large PV and ET cohorts of patients.54 Adverse molecular variants in PV included ASXL1, SRSF2, and IDH2, and in ET SH2B3/LNK, SF3B1, U2AF1, TP53, IDH2, and EZH2, based on age-adjusted multivariable analysis of the impact on overall, leukemia-free and myelofibrosis-free survival. Their presence was associated with inferior survival in both PV (median, 7.7 vs 16.9 years) and ET (median, 9 vs 22 years). The authors incorporated mutational information into a new prognostic model, the Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System (MIPSS) specific for PV and ET (Table 5). Further studies are necessary to validate these models and to determine their role in clinical decision-making.55

Table 5.

Clinical-Molecular Prognostic Scores in Polycythemia Vera and Essential Thrombocythemia

| Prognostic Score | Variables (Points) | Risk Categories (Points) | Median Survival (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIPSS-PV Tefferi et al55 |

Leukocyte count ≥15 x 109/L (1) Thrombosis history (1) Age >67 years (2) SRSF2 mutation (3) |

Low (0–1) Intermediate (2–3) High (4–7) |

24 13.1 3.2 |

| MIPSS-ET Tefferi et al55 |

Leukocyte count ≥11 x 109/L (1) Age >60 years (4) Male sex (1) SRSF2, SF3B1, U2AF1 and TP53 mutation (2) |

Low (0–1) Intermediate (2–5) High (6–8) |

34.3 14.1 7.9 |

Note: In bold molecular variables.

Abbreviations: MIPSS, Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System, PV, polycythemia vera; ET, essential thrombocythemia.

Primary and Post-PV/ET Myelofibrosis

Traditionally, two prognostic models, which include exclusively clinical parameters, are used to stratify PMF patients into risk categories with significant differences in overall survival: International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS),56 that is used at the time of diagnosis, and Dynamic IPSS (DIPSS),57 applicable at any time during the clinical course. These models use five variables that independently predict inferior survival: age >65 years, hemoglobin <10 g/dL, leukocyte count >25 × 109/L, circulating blasts ≥1%, and constitutional symptoms. Subsequently, DIPSS was revised to DIPSS plus,58 including red blood cells transfusion need, platelet count <100 × 109/L, and unfavorable karyotypes (complex karyotype or sole or 2 abnormalities that included +8, −7/7q-, i(17q), inv(3), −5/5q-, 12p- or 11q23 rearrangement).59 In addition to the driver mutations, more than 80% of patients with PMF harbor other DNA variants in myeloid genes, as discussed above, often in multiple combinations.60 Beyond their presumed pathogenetic relevance, driver and other mutations in PMF were shown to influence overall survival and leukemia-free survival, independent of IPSS and DIPSS-plus.61–63 The effect of driver mutations on outcome supports prognostic distinction based on the presence or absence of CALR type-1 mutation,64,65 whereas additional ASXL1, SRSF2, EZH2, and IDH1/IDH2 mutations were defined as high–molecular risk (HMR), with a prognostic relevance amplified by the number of such mutations in an individual patient.60,61,66 Building upon the complementary nature of molecular information, the Molecular enhanced International Prognostic Score Systems (three-tiered MIPSS70 and four-tiered MIPSS70-plus) were developed using a cohort of patients younger than 70 years, potentially eligible for allo-HSCT, recruited from multiple Italian centers and the Mayo Clinic.67 The MIPSS70-plus score additionally included unfavorable karyotype defined by any abnormal karyotype other than normal karyotype or sole abnormalities of 20q-, 13q-, +9, chromosome 1 translocation/duplication, -Y, or sex chromosome abnormality other than -Y. Leukocytosis and BM fibrosis grade ≥2 were included in MIPSS70 but not retained in MIPSS70-plus. Both models predict LFS and OS, but MIPSS70-plus seemed to have the best performance in identifying a very high-risk category of patients, 23% of whom developed acute leukemia, due to additional cytogenetic abnormalities. Further revision, the MIPSS70 v2.0,68 was published incorporating a new HMR mutation U2AF1Q157.69 Additional refinement of risk categories was provided with different thresholds for anemia (defined severe by hemoglobin levels of <8 g/dL in women and <9 g/dL in men, and moderate by hemoglobin levels of 8 to 9.9 g/dL in women and 9 to 10.9 g/dL in men)70 and a new three-tiered cytogenetic risk distribution with the introduction of very high risk (VHR) group for those with single/multiple abnormalities of −7, i(17q), inv(3)/3q21, 12p-/12p11.2, 11q-/11q23, or other autosomal trisomies not including + 8/+ 9.71

These updates were also used for the development of a Genetically Inspired Prognostic Scoring System (GIPSS) that is exclusively based on genetic (ASXL1, SRSF2, U2AF1Q157, absence of type-1 CALR mutations) and cytogenetic markers.72 The authors demonstrated the non-inferiority of GIPSS in discrimination ability and prediction accuracy, compared to MIPSS70-plus and DIPSS. These data were confirmed in an external validation cohort showing also that GIPSS score performs equally well for both primary and secondary myelofibrosis.73 Primarily, all these scores were developed exclusively for patients with a diagnosis of PMF and their performance in patients with secondary MF was suboptimal. Therefore, a specific Myelofibrosis Secondary to PV and ET-Prognostic Model (MYSEC-PM) was developed. This four-tiered score includes the following variables: hemoglobin level, circulating blasts, platelet count, age, presence of constitutional symptoms and CALR mutational status.74 Finally, to overcome the shortcoming of clinical scores for MF in the setting of HSCT and to accurately predict outcome following transplantation, the Myelofibrosis Transplant Scoring System (MTSS) was recently formulated for patients with PMF and post-PV-ET MF. The score variables incorporated were age (≥57 years), Karnofsky performance status, platelet and leukocyte count prior to transplantation (<150x109/L and >25x109/L, respectively), HLA-mismatched unrelated donor, CALR/MPL mutation and ASXL1 mutational status.75 The last to be developed, based on sequencing effort of 69 genes in more than 2000 patients with MPN, including 309 with myelofibrosis, identified a prognostic role for CBL, NRAS, RUNX1, TET2 and P53 and a contribution from GNAS, IDH2 and U2AF1 in both overall survival and leukemia-free survival. This study integrated a remarkable number of demographics, clinical and genomic variables and through the random effects modelling, led to the creation of a personalized predictive individual model for disease transformation and death at each phase into a single multi-stage model.46 A prognostic calculator of individualized patient outcome is available online (https://jg738.shinyapps.io/mpn_app/). An interactive web application is similarly available for MYSEC-PM (http://www.mysec-pm.eu/) and MIPSS70 (http://mipss70score.it). Table 6 provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical-molecular prognostic scoring systems described.

Table 6.

Clinical-Molecular Prognostic Scores in Myelofibrosis

| Prognostic Score | Variables (Points) |

Risk Categories (Points) |

Median Survival (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIPSS70 Guglielmelli et al67 |

Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL (1) Blasts > 2% (1) Constitutional symptoms (1) Leukocytes > 25 x 109/L (2) Platelet count < 100 x 109/L (2) BM fibrosis ≥ 2 (1) Non CALR type-1 (1) HMRa = 1 (1) HMRa ≥ 2 (2) |

Low (0–1) Intermediate (2–4) High (5–12) |

27.7 7.1 2.3 |

| MIPSS70 plus Guglielmelli et al67 |

Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL (1) Blasts > 2% (1) Constitutional symptoms (1) Non CALR type-1 (2) HMRa = 1 (1) HMRa ≥ 2 (2) Unfavourable karyotypeb (3) |

Low (0–2) Intermediate (3) High (4–6) Very high (7–11) |

20.0 6.3 3.9 1.7 |

| MIPSS70 plus v2.0 Tefferi et al68 |

Hemoglobin 8–10 g/dL (1) Hemoglobin <8 g/dL (2) Blasts > 2% (1) Constitutional symptoms (2) Non CALR type-1 (2) HMRa+U2AF1 Q157 = 1 (2) HMRa+U2AF1 Q157 ≥ 2 (3) HR Karyotypec (3) VHR Karyotyped (4) |

Very low (0) Low (1–2) Intermediate (3–4) High (5–8) Very high (9–14) |

Not reached 10.3 7 3.5 1.8 |

| GIPSS Tefferi et al72 |

Non CALR type-1 (1) ASXL1 mutation (1) SRSF2mutation (1) U2AF1Q157 (1)HR karyotypec (1) VHR karyotyped (2) |

Low (0) Intermediate-1 (1) Intermediate-2 (2) High (3–6) |

26.4 8.0 4.2 2.0 |

| MYSEC-PM Passamonti et al74 |

Hemoglobin < 11 g/dL Blasts ≥ 3% Platelets < 150 x 109/L Constitutional symptoms (2) Age at secondary MF (0.15 point/year) CALR unmutated genotype (2) |

Low (<11) Intermediate-1 (11- <14) Intermediate-2 (14- <16) High (≥ 16) |

Not reached 9.3 4.4 2.0 |

| MTSS Gagelmann et al75 |

Platelets < 150 x 109/L (1) Leukocytes > 25 x 109/L (1) Karnofsky PS < 90% (1) Age ≥ 57 years (1) HLA-mismatched unrelated donor (2) Non CALR/MPL mutation (2) ASXL1mutation (1) |

Low (0–2) Intermediate (3–4) High (5) Very high (6–9) |

5-years OS 83% 5-years OS 64% 5-years OS 37% 5-years OS 22% |

Notes: aHigh molecular risk (HMR) include ASXL1, SRSF2, EZH2, IDH1/2. bUnfavourable karyotype defined any abnormal karyotype other than normal karyotype or sole abnormalities of 20q2, 13q2, +9, chromosome 1 translocation/duplication, -Y, or sex chromosome abnormality other than -Y. cHigh risk (HR) karyotype include all the abnormalities that are not VHR and favourable (normal karyotype or sole abnormalities of 20q−, 13q−, +9, chromosome 1 translocation/duplication or sex chromosome abnormality including -Y). dVery high risk (VHR) include single or multiple abnormalities of −7, inv (3), i(17q), 12p−, 11q−, and autosomal trisomies other than +8 or +9. In bold molecular variables.

Abbreviations: MIPSS, Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System; GIPSS, Genetically Inspired Prognostic Scoring System; MYSEC-PM, Myelofibrosis Secondary to PV and ET-Prognostic Model; MTSS, Myelofibrosis Transplant Scoring System; OS, overall survival.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Since JAK2V617, MPL and CALR mutations are driver abnormalities of MPN through activation of the JAK-STAT signaling, developing JAK inhibitors (JAKi) has raised a great interest. Ruxolitinib was the first JAK1/2 inhibitor that received approval in myelofibrosis based on COMFORT I/II clinical trials.76,77 Ruxolitinib was effective in reducing splenomegaly and alleviating constitutional symptoms, with possible effects on survival. Long term follow-up studies suggested a reduction in allele burden, with rare cases of molecular remission.78,79 Subsequently, ruxolitinib was tested in PV patients resistant or intolerant to hydroxyurea, according to European Leukemia-Net (ELN) criteria,80 in RESPONSE81 and RESPONSE-282 studies in patients with and without splenomegaly, respectively. A progressive decline in JAK2 mutant burden in patients treated with ruxolitinib was seen in RESPONSE trial, although without definite clinical correlation.83 Therefore, this provides a challenge to the use of JAK2 allele burden reduction as a marker of treatment efficacy. Moreover, one small study highlighted that MF patients starting with a higher allele burden may benefit the most from ruxolitinib, showing a higher probability of spleen response if allele burden was greater than 50% at entry.84 It is important to underline that ruxolitinib targets the kinase domain of JAK1/2 kinases, without a greater affinity against mutant JAK2; this explains the clinical efficacy also in JAK2 negative patients, with similar response rates. Unfortunately, most patients with myelofibrosis on ruxolitinib will become resistant to therapy with the progression of symptoms and splenomegaly, worsening cytopenias, or evolution to BP; in the COMFORT-II study, responding patients had a < 50% chance of maintaining response at 5 years.78 Intriguingly, as reported by Newberry et al,85 clonal evolution after ruxolitinib discontinuation, defined by the acquisition of at least one additional mutation, was reported in 35% of patients. Mutations mostly occurred in ASXL1, followed by TET2, EZH2 and TP53. Moreover, overall survival after ruxolitinib discontinuation was shorter for patients with clonal evolution compared with the others (6 vs 16 months). One drawback of this study was the lack of a control cohort of patients.86 A subsequent study which included 25 MF patients treated with hydroxyurea as a control group confirmed these data but also demonstrated that clonal progression is independent of the treatment.87 However, acquisition of new mutations under ruxolitinib has important clinical correlates, since it is associated with a higher rate of discontinuation due to resistance to treatment and death.

Allo-HSCT remains the only therapeutic approach that can modify the natural history of MF, but it is associated with a relevant morbidity and mortality and only a minority of patients is eligible for such an intensive procedure. As a consequence, research aimed at the discovery of more effective drugs, also in the context of novel JAKi, is extremely active. In recent years, Interferon-α (IFNα), especially better tolerate pegylated forms (Peg-IFNα), has emerged as a promising approach in MPN, particularly in PV and ET, with high rates of both hematological and molecular remissions.88–92 In this respect, monopegylated Ropeginterferon alpha-2b (Ropeg) has received approval in Europe as a first-line therapy for PV patients following the demonstration of its superior efficacy over hydroxyurea in the PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV trial.92 The treatment appears to selectively target the mutant JAK2 clone, as suggested by the high rate of reduction of JAK2V617F allele burden compared to CALR positive ones.93 As recently reported, enhanced sensitivity of JAK2V617F mutated cells to IFNα was related to high expression and phosphorylated levels of STAT1.94 Interestingly, the presence of concomitant mutations is associated with smaller mean decreases in JAK2V617F allele burden under Peg-IFNα treatment.89 IFNα may have decreased ability to eradicate TET2 clones even in cases where JAK2V617F-mutant clone is markedly reduced, indirectly suggesting that the genomic landscape of MPN patients can predict responses to treatment.95 However, Peg-IFNα used at a higher dose in a cohort of 31 CALR positive ET patients, induced hematologic responses in all patients and median CALR allele burden decreased from 41% to 26%, with two patients achieving complete molecular remission.96 In the latter study, decreases in CALR variant allele frequency correlated with laboratory parameters of disease burden including platelets and white blood cell counts, hemoglobin, and lactate dehydrogenase. Similar to findings in JAK2 mutated patients, the presence of additional mutations such as TET2, ASXL1, IDH2, and TP53 was associated with poorer molecular responses. These responses seem to be also durable, which is an appealing aspect of IFNα treatment. In a long-term 83-month follow up of ET and PV patients treated with Peg-IFNα, median duration of hematologic and molecular response was 66 and 53 months, respectively.97 In addition, three patients had a complete molecular remission even after discontinuation of therapy, although in most patients, JAK2V617F allele burden increased after the first 2 years of treatment stop.

Imetelstat, a 13-mer lipid-conjugated oligonucleotide that targets the RNA template of human telomerase reverse transcriptase, was tested in MF and ET. A pilot study evaluated the efficacy and safety in 33 patients with intermediate-2 and high-risk MF according to DIPPS-plus score. A complete or partial response was observed in seven patients and responses correlated with the presence of JAK2V617F, SF3B1 or U2AF1 mutations and the absence of ASXL1 mutations.98

Conversely, in 18 ET patients treated with imetelstat, a partial molecular response was detected in seven of eight JAK2V617F mutated patients. The median JAK2V617F mutant allele burden was reduced by 71% at 3 months after the initiation of treatment. MPL and CALR mutant allele burdens were also reduced, by 15% to 66%.99 Additional mutations significantly reduced the depth of response and had an impact on the duration of response. Of acquired mutations with known adverse prognosis, ASXL1, EZH2 and U2AF1 mutations were responsive to imetelstat, while SF3B1 and TP53 mutations persisted.100

Mutations in IDH1/2 and TP53 are enriched in BP. These molecular findings may have clinical implications given the role of ivosidenib and enasidenib (anti-IDH1 and IDH2, respectively) in patients with relapsed/refractory IDH-mutated AML101,102 and high response rate of TP53-mutated AML to 10-day decitabine.103 Another promising option is venetoclax, a BCL2 inhibitor that can be used in combination with low-dose cytarabine or hypometilating agents. In a recent trial for patients with AML ineligible for standard induction chemotherapy, azacytidine plus venetoclax was superior to azacytidine alone, also in the subset of IDH1/2 and TP53 mutated patients.104 Although these therapies are promising, patients with MPN BP have a dismal outcome without allo-HSCT. Further studies are needed, but these target therapies may represent a valid therapeutic approach also as a bridge to transplantation, given the frequent refractoriness to conventional chemotherapies of MPN BP patients.

The presence of acquired mutations in the driver and/or myeloid genes in the most part of MF patients offers the opportunity to use these markers as indicators of minimal residual disease (MRD) after allo-HSCT. In some studies, the persistence of JAK2V617F mutation after allo-HSCT was associated with a higher incidence of relapse and a shorter overall survival.105,106 More recently, in a series of 136 patients, Wolschke et al demonstrated that patients with detectable JAK2, MPL or CALR mutation at either day +100 or day +180 after allo-HSCT had a significantly higher risk of relapse at 5 years compared to those in molecular remission (62% vs 10%, and 70% vs 10%, respectively).107 Based on these studies, monitoring of molecular MRD in MF patients after allo-HSCT is strongly recommended.

Conclusions

The discovery of JAK2, CALR and MPL driver mutations elucidated the genetic basis of MPN although some patients, so-called triple negative, while having clinical and histological characteristics of MPN, remain molecularly mute. The introduction of high-throughput NGS techniques expanded the mutational landscape and further raised pathophysiological knowledge. Furthermore, these molecular information let to refine the diagnosis, attribute better prognosis score, and monitor the response to treatments. The development of JAKi offered new hopes to patients with MPN allowing them to achieve significant advances in the control of symptoms and quality of life but are largely insufficient to cure the diseases and prolong survival. The last unmet needs regard the understanding of molecular mechanisms at the basis of loss of response to JAKi and the identification of new molecular abnormalities suitable for target therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AIRC 5x1000 called “Metastatic disease: the key unmet need in oncology” to MYNERVA project, #21267 (MYeloid NEoplasms Research Venture AIRC) and by PRIN (Progetti di rilevante interesse nazionale)-MIUR called “Myeloid neoplasms: an integrated clinical, molecular and therapeutic approach” Prot. 2017WXR72T. The funding had no role in manuscript preparation.

Disclosure

AMV received personal fees for the advisory board from Novartis, Incyte, Bristol-Myers Squibb and AOP and speaker bureau from Novartis, CTI and Celgene. PG received personal fees for the advisory board from Novartis. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P, Tefferi A. Advances in understanding and management of myeloproliferative neoplasms. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(3):171–191. doi: 10.3322/caac.20009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesa RA, Verstovsek S, Cervantes F, et al. Primary myelofibrosis (PMF), post polycythemia vera myelofibrosis (post-PV MF), post essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis (post-ET MF), blast phase PMF (PMF-BP): consensus on terminology by the international working group for myelofibrosis research and. Leuk Res. 2007;31(6):737–740. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barosi G, Mesa RA, Thiele J, et al. Proposed criteria for the diagnosis of post-polycythemia vera and post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis: a consensus statement from the international working group for myelofibrosis research and treatment. Leukemia. 2008;22(2):437–438. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tefferi A, Mudireddy M, Mannelli F, et al. Blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasm: mayo-AGIMM study of 410 patients from two separate cohorts. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1200–1210. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0019-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerquozzi S, Tefferi A. Blast transformation and fibrotic progression in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: a literature review of incidence and risk factors. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(11):e366–e366. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moulard O, Mehta J, Fryzek J, Olivares R, Iqbal U, Mesa RA. Epidemiology of myelofibrosis, essential thrombocythemia, and polycythemia vera in the European Union. Eur J Haematol. 2014;92(4):289–297. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Larson DR, et al. Long-term survival and blast transformation in molecularly annotated essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis. Blood. 2014;124(16):2507–2513; quiz 2615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-579136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boddu P, Chihara D, Masarova L, Pemmaraju N, Patel KP, Verstovsek S. The co-occurrence of driver mutations in chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(11):2071–2080. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3402-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamora L, Xicoy B, Cabezón M, et al. Co-existence of JAK2 V617F and CALR mutations in primary myelofibrosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(10):2973–2974. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1015124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic J-P, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott LM. The JAK2 exon 12 mutations: a comprehensive review. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(8):668–676. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu X, Levine R, Tong W, et al. Expression of a homodimeric type I cytokine receptor is required for JAK2V617F-mediated transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(52):18962–18967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509714102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Huang LJ-S, Lodish HF. Dimerization by a cytokine receptor is necessary for constitutive activation of JAK2V617F. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(9):5258–5266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707125200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sangkhae V, Etheridge SL, Kaushansky K, Hitchcock IS. The thrombopoietin receptor, MPL, is critical for development of a JAK2V617F-induced myeloproliferative neoplasm. Blood. 2014;124(26):3956–3963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passamonti F, Elena C, Schnittger S, et al. Molecular and clinical features of the myeloproliferative neoplasm associated with JAK2 exon 12 mutations. Blood. 2011;117(10):2813–2816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tefferi A, Lavu S, Mudireddy M, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutated polycythemia vera: mayo-Careggi MPN alliance study of 33 consecutive cases and comparison with JAK2V617F mutated disease. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(4):E93–E96. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortmann CA, Kent DG, Nangalia J, et al. Effect of mutation order on myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):601–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nangalia J, Nice FL, Wedge DC, et al. DNMT3A mutations occur early or late in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms and mutation order influences phenotype. Haematologica. 2015;100(11):e438–e442. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.129510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Prospective identification of high-risk polycythemia vera patients based on JAK2(V617F) allele burden. Leukemia. 2007;21(9):1952–1959. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold LI, Eggleton P, Sweetwyne MT, et al. Calreticulin: non‐endoplasmic reticulum functions in physiology and disease. FASEB J. 2010;24(3):665–683. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2391–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, et al. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2379–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabagnols X, Defour JP, Ugo V, et al. Differential association of calreticulin type 1 and type 2 mutations with myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia: relevance for disease evolution. Leukemia. 2015;29(1):249–252. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pietra D, Rumi E, Ferretti VV, et al. Differential clinical effects of different mutation subtypes in CALR-mutant myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2016;30(2):431–438. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tefferi A, Wassie EA, Guglielmelli P, et al. Type 1 versus Type 2 calreticulin mutations in essential thrombocythemia: a collaborative study of 1027 patients. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(8):E121–124. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chachoua I, Pecquet C, El-Khoury M, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor activation by myeloproliferative neoplasm associated calreticulin mutants. Blood. 2016;127(10):1325–1335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-681932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balligand T, Achouri Y, Pecquet C, et al. Pathologic activation of thrombopoietin receptor and JAK2-STAT5 pathway by frameshift mutants of mouse calreticulin. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1775–1778. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nivarthi H, Chen D, Cleary C, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor is required for the oncogenic function of CALR mutants. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1759–1763. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elf S, Abdelfattah NS, Chen E, et al. Mutant calreticulin requires both its mutant C-terminus and the thrombopoietin receptor for oncogenic transformation. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(4):368–381. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pecquet C, Chachoua I, Roy A, et al. Calreticulin mutants as oncogenic rogue chaperones for TpoR and traffic-defective pathogenic TpoR mutants. Blood. 2019;133(25):2669–2681. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-09-874578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masubuchi N, Araki M, Yang Y, et al. Mutant calreticulin interacts with MPL in the secretion pathway for activation on the cell surface. Leukemia. 2020;34(2):499–509. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0564-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staerk J, Lacout C, Sato T, Smith SO, Vainchenker W, Constantinescu SN. An amphipathic motif at the transmembrane-cytoplasmic junction prevents autonomous activation of the thrombopoietin receptor. Blood. 2006;107(5):1864–1871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pikman Y, Lee BH, Mercher T, et al. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Defour J-P, Chachoua I, Pecquet C, Constantinescu SN. Oncogenic activation of MPL/thrombopoietin receptor by 17 mutations at W515: implications for myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1214–1216. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding J, Komatsu H, Wakita A, et al. Familial essential thrombocythemia associated with a dominant-positive activating mutation of the c-MPL gene, which encodes for the receptor for thrombopoietin. Blood. 2004;103(11):4198–4200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bridgford JL, Lee SM, Lee CMM, et al. Novel drivers and modifiers of MPL-dependent oncogenic transformation identified by deep mutational scanning. Blood. 2020;135(4):287–292. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM. Genetic risk assessment in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(8):1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cabagnols X, Favale F, Pasquier F, et al. Presence of atypical thrombopoietin receptor (MPL) mutations in triple-negative essential thrombocythemia patients. Blood. 2016;127(3):333–342. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-661983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milosevic Feenstra JD, Nivarthi H, Gisslinger H, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel MPL and JAK2 mutations in triple-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(3):325–332. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-661835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grinfeld J, Nangalia J, Baxter EJ, et al. Classification and personalized prognosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(15):1416–1430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steensma DP. Clinical consequences of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3404–3410. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018020222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rumi E, Pietra D, Ferretti V, et al. JAK2 or CALR mutation status defines subtypes of essential thrombocythemia with substantially different clinical course and outcomes. Blood. 2014;123(10):1544–1551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-539098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rotunno G, Mannarelli C, Guglielmelli P, et al. Impact of calreticulin mutations on clinical and hematological phenotype and outcome in essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2014;123(10):1552–1555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barbui T, Finazzi G, Carobbio A, et al. Development and validation of an international prognostic score of thrombosis in World Health Organization-essential thrombocythemia (IPSET-thrombosis). Blood. 2012;120(26):5128–5133; quiz 5252. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-444067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barbui T, Vannucchi AM, Buxhofer-Ausch V, et al. Practice-relevant revision of IPSET-thrombosis based on 1019 patients with WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(11):e369. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haider M, Gangat N, Lasho T, et al. Validation of the revised international prognostic score of thrombosis for essential thrombocythemia (IPSET-thrombosis) in 585 Mayo clinic patients. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(4):390–394. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alvarez-Larrán A, Pereira A, Guglielmelli P, et al. Antiplatelet therapy versus observation in low-risk essential thrombocythemia with a CALR mutation. Haematologica. 2016;101(8):926–931. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.146654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Guglielmelli P, et al. Targeted deep sequencing in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood Adv. 2016;1(1):21–30. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016000216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, et al. Mutation-enhanced international prognostic systems for essential thrombocythaemia and polycythaemia vera. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(2):291–302. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Pereira A, et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the international working group for myelofibrosis research and treatment. Blood. 2009;113(13):2895–2901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Passamonti F, Cervantes F, Vannucchi AM, et al. A dynamic prognostic model to predict survival in primary myelofibrosis: a study by the IWG-MRT (International Working Group for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment). Blood. 2010;115(9):1703–1708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gangat N, Caramazza D, Vaidya R, et al. DIPSS plus: a refined dynamic international prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):392–397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caramazza D, Begna KH, Gangat N, et al. Refined cytogenetic-risk categorization for overall and leukemia-free survival in primary myelofibrosis: a single center study of 433 patients. Leukemia. 2011;25(1):82–88. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, et al. Targeted deep sequencing in primary myelofibrosis. Blood Adv. 2016;1(2):105–111. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016000208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vannucchi AM, Lasho TL, Guglielmelli P, et al. Mutations and prognosis in primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1861–1869. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, et al. CALR and ASXL1 mutations-based molecular prognostication in primary myelofibrosis: an international study of 570 patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1494–1500. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, et al. CALR vs JAK2 vs MPL-mutated or triple-negative myelofibrosis: clinical, cytogenetic and molecular comparisons. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1472–1477. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Tischer A, et al. The prognostic advantage of calreticulin mutations in myelofibrosis might be confined to type 1 or type 1-like CALR variants. Blood. 2014;124(15):2465–2466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-588426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guglielmelli P, Rotunno G, Fanelli T, et al. Validation of the differential prognostic impact of type 1/type 1-like versus type 2/type 2-like CALR mutations in myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(10):e360–e360. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. The number of prognostically detrimental mutations and prognosis in primary myelofibrosis: an international study of 797 patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(9):1804–1810. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: mutation-enhanced international prognostic score system for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310–318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, et al. MIPSS70+ version 2.0: mutation and karyotype-enhanced international prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1769–1770. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tefferi A, Finke CM, Lasho TL, et al. U2AF1 mutation types in primary myelofibrosis: phenotypic and prognostic distinctions. Leukemia. 2018;32(10):2274–2278. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0078-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nicolosi M, Mudireddy M, Lasho TL, et al. Sex and degree of severity influence the prognostic impact of anemia in primary myelofibrosis: analysis based on 1109 consecutive patients. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1254–1258. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0028-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tefferi A, Nicolosi M, Mudireddy M, et al. Revised cytogenetic risk stratification in primary myelofibrosis: analysis based on 1002 informative patients. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1189–1199. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0018-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Nicolosi M, et al. GIPSS: genetically inspired prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2018;32(7):1631–1642. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0107-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuykendall AT, Talati C, Padron E, et al. Genetically inspired prognostic scoring system (GIPSS) outperforms dynamic international prognostic scoring system (DIPSS) in myelofibrosis patients. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(1):87–92. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Passamonti F, Giorgino T, Mora B, et al. A clinical-molecular prognostic model to predict survival in patients with post polycythemia vera and post essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2017;31(12):2726–2731. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gagelmann N, Ditschkowski M, Bogdanov R, et al. Comprehensive clinical-molecular transplant scoring system for myelofibrosis undergoing stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2019;133(20):2233–2242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-12-890889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harrison C, Kiladjian -J-J, Al-Ali HK, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):787–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harrison CN, Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian -J-J, et al. Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a Phase 3 study of ruxolitinib vs best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1701–1707. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. Long-term treatment with ruxolitinib for patients with myelofibrosis: 5-year update from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 COMFORT-I trial. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0417-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057–1069. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian JJ, Griesshammer M, et al. Ruxolitinib versus standard therapy for the treatment of polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):426–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Passamonti F, Griesshammer M, Palandri F, et al. Ruxolitinib for the treatment of inadequately controlled polycythaemia vera without splenomegaly (RESPONSE-2): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):88–99. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30558-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vannucchi AM, Verstovsek S, Guglielmelli P, et al. Ruxolitinib reduces JAK2 p.V617F allele burden in patients with polycythemia vera enrolled in the RESPONSE study. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(7):1113–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-2994-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barosi G, Klersy C, Villani L, et al. JAK2V617F allele burden < 50% is associated with response to ruxolitinib in persons with MPN-associated myelofibrosis and splenomegaly requiring therapy. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1772–1775. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Newberry KJ, Patel K, Masarova L, et al. Clonal evolution and outcomes in myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib discontinuation. Blood. 2017;130(9):1125–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-783225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P. Traffic lights for ruxolitinib. Blood. 2017;130(9):1075–1077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pacilli A, Rotunno G, Mannarelli C, et al. Mutation landscape in patients with myelofibrosis receiving ruxolitinib or hydroxyurea. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(12). doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0152-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Manshouri T, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a yields high rates of hematologic and molecular response in patients with advanced essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5418–5424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Quintás-Cardama A, Abdel-Wahab O, Manshouri T, et al. Molecular analysis of patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia receiving pegylated interferon α-2a. Blood. 2013;122(6):893–901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Them NCC, Bagienski K, Berg T, et al. Molecular responses and chromosomal aberrations in patients with polycythemia vera treated with peg-proline-interferon alpha-2b. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(4):288–294. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gisslinger H, Zagrijtschuk O, Buxhofer-Ausch V, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b, a novel IFNα-2b, induces high response rates with low toxicity in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2015;126(15):1762–1769. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-637280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(3):e196–e208. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30236-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kjær L, Cordua S, Holmström MO, et al. Differential dynamics of CALR mutant allele burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms during interferon alfa treatment. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Czech J, Cordua S, Weinbergerova B, et al. JAK2V617F but not CALR mutations confer increased molecular responses to interferon-α via JAK1/STAT1 activation. Leukemia. 2019;33(4):995–1010. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0295-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kiladjian -J-J, Massé A, Cassinat B, et al. Clonal analysis of erythroid progenitors suggests that pegylated interferon α-2a treatment targets JAK2V617F clones without affecting TET2 mutant cells. Leukemia. 2010;24(8):1519–1523. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Verger E, Cassinat B, Chauveau A, et al. Clinical and molecular response to interferon-α therapy in essential thrombocythemia patients with CALR mutations. Blood. 2015;126(24):2585–2591. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-659060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Masarova L, Patel KP, Newberry KJ, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a in patients with essential thrombocythaemia or polycythaemia vera: a post-hoc, median 83 month follow-up of an open-label, Phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(4):e165–e175. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30030-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Begna KH, et al. A pilot study of the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):908–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Baerlocher GM, Oppliger Leibundgut E, Ottmann OG, et al. Telomerase inhibitor imetelstat in patients with essential thrombocythemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):920–928. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oppliger Leibundgut E, Haubitz M, Burington B, et al. Dynamics of mutations in patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with imetelstat. Haematologica. 2020;haematol.2020.252817. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.252817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, et al. Durable remissions with ivosidenib in IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2386–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;130(6):722–731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-779405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Welch JS, Petti AA, Miller CA, et al. TP53 and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2023–2036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):617–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alchalby H, Badbaran A, Zabelina T, et al. Impact of JAK2V617F mutation status, allele burden, and clearance after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2010;116(18):3572–3581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-260588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lange T, Edelmann A, Siebolts U, et al. JAK2 p.V617F allele burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms one month after allogeneic stem cell transplantation significantly predicts outcome and risk of relapse. Haematologica. 2013;98(5):722–728. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.076901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wolschke C, Badbaran A, Zabelina T, et al. Impact of molecular residual disease post allografting in myelofibrosis patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(11):1526–1529. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2017.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lasho TL, Mudireddy M, Finke CM, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing in blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood Adv. 2018;2(4):370–380. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018015875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutation studies in 1473 patients with chronic-, fibrotic- or blast-phase essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2010;24(7):1302–1309. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke C, et al. Prognostic significance of ASXL1 mutation types and allele burden in myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2018;32(3):837–839. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kröger N, Panagiota V, Badbaran A, et al. Impact of molecular genetics on outcome in myelofibrosis patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(7):1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shimizu T, Kubovcakova L, Nienhold R, et al. Loss of Ezh2 synergizes with JAK2-V617F in initiating myeloproliferative neoplasms and promoting myelofibrosis. J Exp Med. 2016;213(8):1479–1496. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Guglielmelli P, Biamonte F, Score J, et al. EZH2 mutational status predicts poor survival in myelofibrosis. Blood. 2011;118(19):5227–5234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-363424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lasho TL, Jimma T, Finke CM, et al. SRSF2 mutations in primary myelofibrosis: significant clustering with IDH mutations and independent association with inferior overall and leukemia-free survival. Blood. 2012;120(20):4168–4171. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang S-J, Rampal R, Manshouri T, et al. Genetic analysis of patients with leukemic transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms shows recurrent SRSF2 mutations that are associated with adverse outcome. Blood. 2012;119(19):4480–4485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tefferi A, Nicolosi M, Mudireddy M, et al. Driver mutations and prognosis in primary myelofibrosis: mayo-Careggi MPN alliance study of 1095 patients. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):348–355. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Hanson CA, Ketterling RP, Gangat N, Pardanani A. Screening for ASXL1 and SRSF2 mutations is imperative for treatment decision-making in otherwise low or intermediate-1 risk patients with myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(4):678–681. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chowdhury O, O’Sullivan J, Barkas N, et al. Spliceosome mutations are common in persons with myeloproliferative neoplasm-associated myelofibrosis with RBC-transfusion-dependence and correlate with response to pomalidomide. Leukemia. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0979-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Maslah N, Cassinat B, Verger E, Kiladjian -J-J, Velazquez L. The role of LNK/SH2B3 genetic alterations in myeloproliferative neoplasms and other hematological disorders. Leukemia. 2017;31(8):1661–1670. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Loscocco GG, Mannarelli C, Pacilli A, et al. Germline transmission of LNKE208Q variant in a family with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(9):E356–E356. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rumi E, Harutyunyan AS, Pietra D, et al. LNK mutations in familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2016;128(1):144–145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-711150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sanada M, Suzuki T, Shih L-Y, et al. Gain-of-function of mutated C-CBL tumour suppressor in myeloid neoplasms. Nature. 2009;460(7257):904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature08240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Coltro G, Rotunno G, Mannelli L, et al. RAS/CBL mutations predict resistance to JAK inhibitors in myelofibrosis and are associated with poor prognostic features. Blood Adv. 2020;4(15):3677–3687. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Braun BS, Shannon K. Targeting Ras in myeloid leukemias. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2249–2252. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jutzi JS, Bogeska R, Nikoloski G, et al. MPN patients harbor recurrent truncating mutations in transcription factor NF-E2. J Exp Med. 2013;210(5):1003–1019. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Guglielmelli P, Pacilli A, Coltro G, et al. Characteristics and clinical correlates of NFE2 mutations in chronic Myeloproliferative neoplasms. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(1). doi: 10.1002/ajh.25668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kahn JD, Miller PG, Silver AJ, et al. PPM1D-truncating mutations confer resistance to chemotherapy and sensitivity to PPM1D inhibition in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2018;132(11):1095–1105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-850339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]