Opinion statement

Although radical cystectomy is considered the gold standard approach for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, tri-modal therapy (TMT) is a well-tolerated and efficacious alternative to radical cystectomy that is underutilized in inoperable patients and rarely offered to cystectomy candidates in the USA. Retrospective data suggest similar outcomes between radical cystectomy and TMT after adjusting for patient selection and other confounding factors. Nearly 70–80% of patients can keep their native bladder with favorable post-treatment quality of life metrics. Current trials are investigating novel combination strategies including immune checkpoint inhibition along with chemoradiation or radiation. Emerging techniques for improved patient selection and risk stratification include incorporating MP-MRI, and novel biomarkers such as inflammatory, stromal, and DNA damage response gene signatures may guide patient selection and expand the landscape of bladder preservation options available to patients in the future.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Radiation therapy, Bladder preservation, Urothelial Cancer

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the most common malignancy of the urinary system with over 80,000 cases and nearly 18,000 deaths estimated in the USA in 2020 [1]. The majority of patients present with early stage, nonmuscle-invasive disease which may be managed with a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) and intra-vesical therapy. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is defined as T2 or greater disease and represents 25% of cases. The most common treatment for MIBC is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy, which involves removal of the bladder and prostate for men and anterior exenteration (including the bladder, uterus, ovaries, and part of the vagina) for women. However, radical cystectomy is associated with significant morbidity and impact on quality of life particularly with increasing age. In a population-based study, the 90-day mortality rate following cystectomy was 5.4% for patients 70–79 years old and 9.2% for patients greater than 80 years old [2]. Because bladder cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly with a median age of 70 at time of diagnosis, many patients are unfit for surgical management due to age-related functional decline or co-morbidities. Smoking is a primary risk factor for bladder cancer, and patients commonly have smoking-related co-morbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary artery disease which increase operative risk [3]. For these reasons, many older patients do not receive curative intent medical therapy due to concerns of treatment-related toxicity [4]. There is a critical need for alternative therapies to mitigate the under-treatment of patients who are not surgical candidates or who desire organ-sparing alternatives to radical cystectomy.

Tri-modal therapy (TMT) is a well-established organ-sparing approach that relies on a combination of limited resection, radiation, and chemotherapy. The typical approach to TMT involves maximal transurethral resection (TURBT), followed by concurrent chemotherapy and radiation, offering an evidence-based curative alternative to radical surgery for select patients with localized muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). This approach is recognized by guidelines from the American Urological Association, European Association of Urology, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines [5-7]. TURBT alone and partial cystectomy are alternative methods for bladder preservation for some patients, but their role in locally advanced MIBC is limited [8]. Here, we summarize the current landscape, clinical rationale, technical considerations, and future directions for applying TMT in the contemporary multidisciplinary management of MIBC.

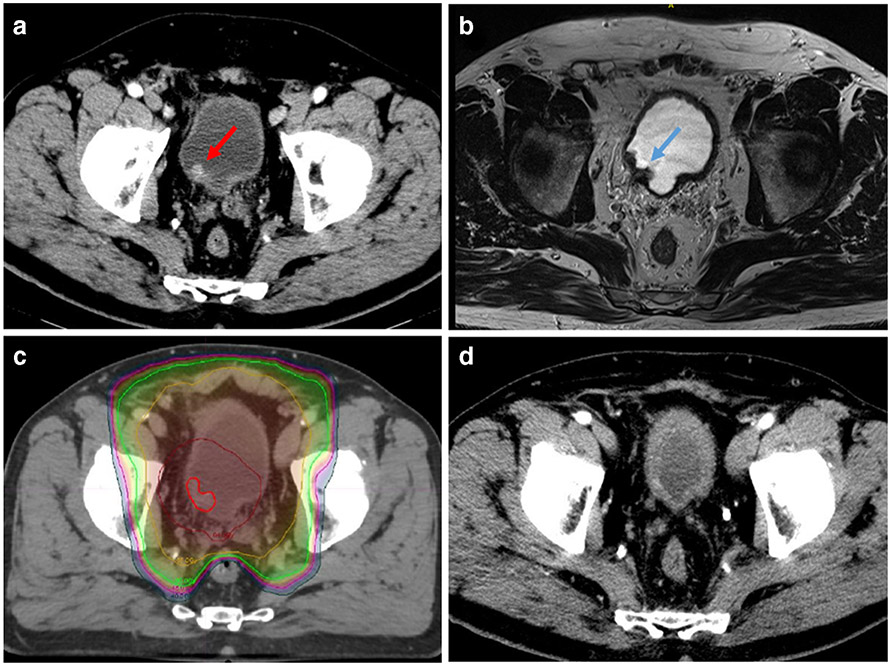

Cystoscopy and TURBT is the initial procedure for diagnosis, clinical staging, and treatment of bladder tumors. For muscle-invasive disease, the NCCN guidelines recommend CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to complete the staging work-up. Patient selection is important for successful bladder preservation; ideal candidates for TMT have good baseline bladder function, unifocal tumors amenable to complete TURBT, no prior history of pelvic radiotherapy, and absence of high-risk features including extensive carcinoma in situ (CIS) and hydronephrosis. Multiple studies have demonstrated an association between a visibly complete TURBT with complete response, overall survival, and long-term bladder preservation following TMT [9, 10]. While a visibly complete TURBT is preferred, 57% of patients with a visibly incomplete TURBT were able to achieve complete response following chemoradiation in a single-institution experience [10]. There is an emerging role for MRI in staging and risk stratification for bladder cancer [11], and ongoing studies are investigating the use of multi-parametric MRI (MP-MRI) in reducing under-staging of MIBC by TURBT [12]. While prospective studies are needed to define the role of MRI in optimizing patient selection for TMT, in our experience, MP-MRI can be useful for delineating the resection bed after TURBT for the purposes of radiation targeting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bladder preservation with tri-modality therapy (TMT). a Patient with a unifocal enhancing bladder tumor (red arrow) on CT scan; TURBT demonstrated T2 HG-MIBC. b Post-TURBT T2 weighted MRI showing resection bed and residual tumor (blue arrow). c Image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IG-IMRT) treating tumor bed (bright red outline) and high-risk region to 64 Gy (dark red isodose line) and regional lymph nodes to 45–50 Gy (green and yellow isodose lines, respectively). Note rectal sparing achievable using IMRT. d At a 3-year follow-up, no residual tumor in the bladder on CT or cystoscopy and no evidence of distant recurrence; patient has excellent bladder function.

The presence of extensive CIS has been associated with high local recurrence rates in trials of radiation alone, though the prognostic impact in the setting of chemoradiation is less clear [13]. Patients with hydronephrosis have lower rates of complete response to chemoradiation and worse overall survival [14]. It is worth noting that hydronephrosis also portends worse prognosis in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy, and thus may be a prognostic marker rather than one specifically predictive of response to TMT [15]. For patients who meet criteria for TMT, long-term survival outcomes are comparable to those achieved with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy [9, 16].

Chemotherapy

Several contemporary trials have defined the modern approach to TMT in MIBC (Table 1). Most have utilized concurrent radio-sensitizing cisplatin as the backbone of concurrent chemotherapy [17, 21]. BC2001 was a recent prospective randomized phase III trial comparing radiation alone vs radiation with concurrent 5-FU and mitomycin C [18]. At 2 years, rates of locoregional disease-free survival were 67% (95% confidence interval [CI], 59 to 74) in the chemoradiation group and 54% (95% CI, 46 to 62) in the radiotherapy group. The chemoradiation regimen was well-tolerated with 95% of patients completing radiation and 80% completing chemotherapy. A 5-year overall survival in this elderly population (median age of 72) was 48%. These results taken together with prior studies consistently demonstrate that concurrent chemoradiation is superior to radiation alone for MIBC.

Table 1.

| Trial | N | Arms | RT Schedule | Concurrent CHT |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC2001 | 360 | RT ± concurrent CHT | 55Gy at 1-8Gy/fx daily or 64Gy at 2.0Gy/fx daily | 5FU + MMC | 5-year OS: 35% vs 48% (SS) |

| RTOG 8903 | 123 | Concurrent CRT ± neoadjuvant MCV | 64.8Gy at 1.8Gy/fx daily | Cisplatin | 5-year OS: 48% vs 49% (NS) |

| RTOG 0524 | 66 | Concurrent CRT with paclitaxel ± trastuzumab | 64.8Gy at 1.8Gy/fx daily | Paclitaxel ± trastuzumab | 1-year CR: 72% vs 68% (NS) |

| RTOG 0712 | 68 | Twice-daily RT + concurrent 5-FU/cisplatin vs once-daily RT + gemictabine | 64Gy at 2 Gy/fx daily | FU/cisplatin vs gemictabine | 3-year DMFS: 78% vs 84% G3/4 toxicity: 64% vs 55% |

5-FU 5-fluorouracil, CHT chemotherapy, CRT concurrent chemoradiation, DMFS distant metastasis–free survival, Gy gray, fx fraction, MCV methotrexate, cisplatin, and vinblastine, MMC mitomycin C, NS not statistically significant, OS overall survival, RT radiotherapy, SS statistically significant

Modern trials have explored cisplatin-free regimens, suitable for patients with impaired renal function or hearing deficits. The recently published RTOG 0712 was a prospective randomized phase II trial comparing twice-daily radiation with concurrent cisplatin/5-FU vs once-daily radiation with concurrent gemcitabine [19•]. Both regimens demonstrated excellent disease-free survival with less toxicity in the gemcitabine plus once-daily radiation arm.

There is no clear role for induction chemotherapy preceding concurrent chemoradiation. The RTOG 8903 trial compared concurrent radiation and cisplatin with or without two cycles of MCV (methotrexate, cisplatin, and vinblastine) and found no difference in the 5-year clinical response or overall survival [17]. Modern studies are revisiting this question using biomarker-based risk stratification, for example, assessment of DNA damage response alterations to identify patients for selective bladder preservation based on clinical/pathologic response to induction chemotherapy [22]. Although adjuvant chemotherapy was utilized on RTOG trials investigating TMT, it has not been evaluated in a randomized fashion, and thus its benefit remains unclear [19, 21].

Radiation therapy

Advances in radiation therapy, including intensity-modulated radiation therapy and image-guided radiotherapy, have improved the ability to deliver radiotherapy safely and precisely. Radiation oncologists typically deliver a dose of 55–64 Gy in 2–2.75 Gy daily fractions over a period of 4–6 weeks. Conventional target volumes include the whole or partial bladder, distal ureters, and proximal urethra (including the prostate in men). There remains a disagreement as to whether pelvic lymph nodes should always be treated, though regional nodes are often included within the standard margin for set-up variation and extravesicular spread. Partial bladder radiation may be utilized in cases of unifocal tumors where the lesion/TURBT bed is well-defined (Fig. 1). Partial bladder treatment demonstrates a similar efficacy compared to whole bladder radiation while potentially reducing bladder, bowel, and rectal toxicity [23]. A split-course approach is standard in the USA for operative candidates, allowing for interim cystoscopy to assess tumor response and early salvage cystectomy in cases of incomplete tumor response. Alternatively, many advocate for completing the full course of chemoradiation in continuous fashion (per BC2001) with early cystoscopic assessment and then regular surveillance following TMT.

Surveillance

Patients experiencing a complete response following TMT undergo close surveillance with cystoscopy and cross-sectional imaging. Non-invasive recurrences can be managed with transurethral resection and intravesicular therapy. In the cases of invasive local recurrence, salvage cystectomy can be performed with acceptable toxicity and excellent long-term control rates [24]. The rates of major complications and mortality at 90 days following salvage cystectomy are 16% and 2%, respectively, which are comparable to outcomes following upfront radical cystectomy [25]. Disease-specific survival at 10 years following salvage cystectomy is 45%, demonstrating that long-term disease control comparable to up front cystectomy is achievable in the high-risk subgroup with invasive recurrence after TMT [9].

Quality of life outcomes

Organ-sparing multimodality approaches have largely replaced radical surgeries as first line therapies in multiple disease sites including breast [26], head and neck [27], cervical cancer [28], and anal cancer [29]. In these diseases, limited resection or biopsy is typically followed by curative intent (concurrent or sequential) chemoradiation. Organ preservation is ideally performed in cases where the native organ can be expected to maintain satisfactory function following treatment. Most patients undergoing TMT maintain excellent bladder function and quality of life. Approximately 70–80% of patients maintain their native bladders, though up to 20% of patients ultimately require a salvage cystectomy [30]. A pooled analysis of 4 RTOG trials reported toxicities of 285 patients who underwent TMT [31]. After a median follow-up of 5.4 years, the rates of grade 3 GU and GI toxicities were 5.7% and 1.9% respectively, without grade 4 or 5 toxicities. A single-institution series of 32 patients treated with TMT demonstrated that 75% had normally functioning bladders based on urodynamic studies [32]. Flow symptoms occurred in 6%, urgency in 15%, and control problems in 19%. The majority of men retained sexual function, and global health–related quality of life was high. Functional outcomes with respect to bowel, urinary, and sexual function compare favorably to radical cystectomy [16].

Oncologic outcomes

TMT and surgery have never been successfully compared in a prospective, randomized fashion. SPARE (selective bladder preservation against radical excision) was a prospective randomized phase III trial designed to compare TMT versus radical cystectomy, but ultimately closed due to poor accrual [33]. A handful of retrospective observational studies have demonstrated inferior outcomes, primarily with respect to local recurrence, for patients undergoing TMT. This finding may reflect the fact that TMT patients retain their native bladder in which secondary tumors may arise. Nevertheless, a large meta-analysis of 9554 patients across 8 studies found no difference in a 10-year disease-specific survival or overall survival between the two modalities [34, 35]. In the absence of level I evidence, these retrospective data must be interpreted with caution due to the influence of selection bias, confounding, and misclassification. For example, patients undergoing TMT are typically older than cystectomy candidates with more co-morbidities. The median age of the SWOG 8710 trial investigating neoadjuvant chemotherapy preceding radical cystectomy was 64 years old, compared to a median age of 72 years old in the BC2001 trial investigating definitive radiation with or without chemotherapy [18, 36]. Attempts can be made to account for such differences (e.g., propensity weighting), though these efforts are often limited by unmeasured differences between groups. Many cancer registries report age and co-morbidities, for example, but do not report performance status which represents an important unmeasured confounder. Additionally, there is frequent discordance between the clinical and pathologic staging resulting in under-staging of patients undergoing TMT. In a single-institution retrospective report of 212 patients with clinical T2 tumors undergoing radical cystectomy without neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 73% had either pathologic T3/T4 or node-positive disease [37]. Acknowledging the limitations of the current evidence, TMT appears to be a reasonable alternative to radical cystectomy. Long-term survival is comparable to surgical management with a 5-year overall survival and disease-specific survival of 57% and 66% respectively [38].

Future directions

Emerging strategies in bladder-preservation incorporate immunotherapy and use novel biomarkers and imaging techniques for patient selection. For instance, the phase III SWOG/NRG 1806 study is investigating TMT with and without atezolizumab [39]. KEYNOTE-992 is another phase III trial investigating TMT with and without pembrolizumab [40]. In the phase II setting, the REQ-0000020479 study seeks to evaluate the role of synchronous nivolumab with chemoradiation [41]. Similarly, the phase II ANZUP 1502 trial is evaluating concurrent pembrolizumab with chemoradiation [42]. The role of maintenance atezolizumab following chemoradiation is also under investigation with the phase II UC-0160/1715 study [43]. Another novel paradigm being investigated is the omission of chemotherapy with the focus on the combination of immunotherapy with radiation. Two phase II SOGUG trials are set to explore the potential synergistic combination of immune-stimulating radiation with checkpoint inhibition. The SOGUG-2017-A-IEC(VEJ)-1 study is examining the role of dual checkpoint inhibition with durvalumab and tremelimumab with concurrent radiation [44]. The SOGUG-2017-A-IEC(VEJ)-4 trial is assessing the efficacy of atezolizumab with concurrent radiation [45]. In the preclinical setting, the first-in-class CD47 antibody magrolimab, a macrophage checkpoint inhibitor that promotes tumor cell phagocytosis, is under development [46]. Finally, interventional approaches are being evaluated such as intra-arterial chemotherapy with radiation as well as an intravesicular chemotherapy delivery device [47].

Selection criteria for TMT is currently based on clinical and pathological factors, but there is growing interest in incorporating novel biomarkers that may predict for complete response and favorable prognosis for TMT. Biomarker analyses to-date have suggested DNA damage response markers including MRE11 and ERCC1/2 as predictors of cancer-specific survival among 2 independent TMT cohorts [48, 49]. Transcriptome-wide analyses from primary tumors of patients undergoing TMT have also revealed gene signatures that appear to be associated with disease-specific survival unique to TMT as opposed to neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radical cystectomy [50]. Namely, T cell activation and interferon-gamma signaling signatures, indicating higher immunecell infiltration, were associated with statistically significant disease-specific survival in the TMT cohort, while stromal signatures predicted worse disease-specific survival in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical cystectomy cohorts but not the TMT group. These studies, however, are limited due to their retrospective design, and it remains to be seen whether gene signatures will remain predictive or prognostic in prospective trials of bladder preservation. In the setting of combination with checkpoint inhibition, the SWOG/NRG 1806 and KEYNOTE-992 studies both have planned biomarker analyses to guide future patient selection [39, 40]. Transcriptomic analyses have suggested that there may be variations in oncological outcomes based on molecular subtypes such as neuroendocrine-like MIBC that has gene expression signatures of a neuroendocrine tumor in the absence of a neuroendocrine (NE) histology [51]. These tumors may behave more similarly to NE tumors of other histologies than conventional basal/luminal MIBC which may influence future trials and clinical decision-making when deciding between organ-sparing strategies versus radical cystectomy [52].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

James R. Broughman declares that he has no conflict of interest. Winston Vuong declares that he has no conflict of interest. Omar Y. Mian declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liberman D, Lughezzani G, Sun M, Alasker A, Thuret R, Abdollah F, et al. Perioperative mortality is significantly greater in septuagenarian and octogenarian patients treated with radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. 2011;77(3):660–6. 10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Megwalu II, Vlahiotis A, Radwan M, Piccirillo JF, Kibel AS. Prognostic impact of comorbidity in patients with bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;53(3):581–9. 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray PJ, Fedewa SA, Shipley WU, Efstathiou JA, Lin CC, Zietman AL, et al. Use of potentially curative therapies for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the United States: results from the National Cancer Data Base. Eur Urol. 2013;63(5):823–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Bladder Cancer (Version 2019). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

- 6.Chang SS, Bochner BH, Chou R, Dreicer R, Kamat AM, Lerner SP, et al. Treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO guideline. J Urol. 2017;198(3):552–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Copenhagen 2018. ISBN 978-94-92671-01-1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ericson KJ, Murthy PB, Bryk DJ, Ramkumar RR, Broughman JR, Khanna A, et al. Bladder-sparing treatment of nonmetastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2019;17(12):697–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rödel C, Grabenbauer GG, Kühn R, Papadopoulos T, Dunst J, Meyer M, et al. Combined-modality treatment and selective organ preservation in invasive bladder cancer: long-term results. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(14):3061–71. 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efstathiou JA, Spiegel DY, Shipley WU, Heney NM, Kaufman DS, Niemierko A, et al. Long-term outcomes of selective bladder preservation by combined-modality therapy for invasive bladder cancer: the MGH experience. Eur Urol. 2012;61(4):705–11. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panebianco V, Narumi Y, Altun E, Bochner BH, Efstathiou JA, Hafeez S, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for bladder cancer: development of VI-RADS (Vesical imaging-reporting and data system). Eur Urol. 2018;74(3):294–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Replacement of a surgical procedure called transurethral resection of bladder tumour with a painless imaging procedure called magnetic resonance imaging in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer (ISRCTN35296862).

- 13.Gospodarowicz MK, Hawkins NV, Rawlings GA, Connolly JG, Jewett MA, Thomas GM, et al. Radical radiotherapy for muscle invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: failure analysis. J Urol. 1989;142(6):1448–53 discussion 53-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman DS, Shipley WU, Griffin PP, Heney NM, Althausen AF, Efird JT. Selective bladder preservation by combination treatment of invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(19):1377–82. 10.1056/NEJM199311043291903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stimson CJ, Cookson MS, Barocas DA, Clark PE, Humphrey JE, Patel SG, et al. Preoperative hydronephrosis predicts extravesical and node positive disease in patients undergoing cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol. 2010;183(5):1732–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mak KS, Smith AB, Eidelman A, Clayman R, Niemierko A, Cheng JS, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(5):1028–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shipley WU, Winter KA, Kaufman DS, Lee WR, Heney NM, Tester WR, et al. Phase III trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with invasive bladder cancer treated with selective bladder preservation by combined radiation therapy and chemotherapy: initial results of radiation therapy oncology group 89-03. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;16(11):3576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James ND, Hussain SA, Hall E, Jenkins P, Tremlett J, Rawlings C, et al. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(16):1477–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.•.Coen JJ, Zhang P, Saylor PJ, Lee CT, Wu CL, Parker W, et al. Bladder preservation with twice-a-day radiation plus fluorouracil/cisplatin or once daily radiation plus gemcitabine for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: NRG/ RTOG 0712-a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019;37(1):44–5.A randomized, phase II trial investigating platinum-free chemotherapy regimens.

- 20.Michaelson MD, Hu C, Pham HT, Dahl DM, Lee-Wu C, Swanson GP, et al. A phase 1/2 trial of a combination of paclitaxel and trastuzumab with daily irradiation or paclitaxel alone with daily irradiation after transurethral surgery for noncystectomy candidates with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (trial NRG oncology RTOG 0524). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(5):995–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitin T, Hunt D, Shipley WU, Kaufman DS, Uzzo R, Wu C-L, et al. Transurethral surgery and twice-daily radiation plus paclitaxel-cisplatin or fluorouracilcisplatin with selective bladder preservation and adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer (RTOG 0233): a randomised multicentre phase. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(9):863–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dose dense gemcitabine and cisplatin without cystectomy for patients with muscle invasive bladder urothelial cancer and select genetic alterations (A031701).

- 23.Cowan RA, McBain CA, Ryder WD, Wylie JP, Logue JP, Turner SL, et al. Radiotherapy for muscle-invasive carcinoma of the bladder: results of a randomized trial comparing conventional whole bladder with dose-escalated partial bladder radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(1):197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shabsigh A, Korets R, Vora KC, Brooks CM, Cronin AM, Savage C, et al. Defining early morbidity of radical cystectomy for patients with bladder cancer using a standardized reporting methodology. Eur Urol. 2009;55(1):164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eswara JR, Efstathiou JA, Heney NM, Paly J, Kaufman DS, McDougal WS, et al. Complications and long-term results of salvage cystectomy after failed bladder sparing therapy for muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2012;187(2):463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer S, Gelber RD, Snow JB, Marcial VA, Lowry LD, Davis LW, et al. Combined radiation therapy and surgery in the management of advanced head and neck cancer: final report of study 73-03 of the radiation therapy oncology group. Head Neck Surg. 1987;10(1):19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landoni F, Colombo A, Milani R, Placa F, Zanagnolo V, Mangioni C. Randomized study between radical surgery and radiotherapy for the treatment of stage IB-IIA cervical cancer: 20-year update. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28(3):e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leichman L, Nigro N, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B, Buroker T, Bradley G, et al. Cancer of the anal canal. Model for preoperative adjuvant combined modality therapy. Am J Med. 1985;78(2):211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Büchser D, Zapatero A, Rogado J, Talaya M, Martín de Vidales C, Arellano R, et al. Long-term outcomes and patterns of failure following trimodality treatment with bladder preservation for invasive bladder cancer. Urology. 2019;124:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Efstathiou JA, Bae K, Shipley WU, Kaufman DS, Hagan MP, Heney NM, et al. Late pelvic toxicity after bladder-sparing therapy in patients with invasive bladder cancer: RTOG 89-03, 95-06, 97-06, 99-06. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zietman AL, Sacco D, Skowronski U, Gomery P, Kaufman DS, Clark JA, et al. Organ conservation in invasive bladder cancer by transurethral resection, chemotherapy and radiation: results of a urodynamic and quality of life study on long-term survivors. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1772–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huddart RA, Hall E, Lewis R, Birtle A. Life and death of spare (selective bladder preservation against radical excision): reflections on why the spare trial closed. BJU Int. 2010;106(6):753–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bekelman JE, Handorf EA, Guzzo T, Evan Pollack C, Christodouleas J, Resnick MJ, et al. Radical cystectomy versus bladder-preserving therapy for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma: examining confounding and misclassification biasin cancer observational comparative effectiveness research. Value Health. 2013;16(4):610–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vashistha V, Wang H, Mazzone A, Liss MA, Svatek RS, Schleicher M, et al. Radical cystectomy compared to combined modality treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(5):1002–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zehnder P, Studer UE, Skinner EC, Dorin RP, Cai J, Roth B, et al. Super extended versus extended pelvic lymph node dissection in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a comparative study. J Urol. 2011;186(4):1261–8. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canter D, Long C, Kutikov A, Plimack E, Saad I, Oblaczynski M, et al. Clinicopathological outcomes after radical cystectomy for clinical T2 urothelial carcinoma: further evidence to support the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BJU Int. 2011;107(1):58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giacalone NJ, Shipley WU, Clayman RH, Niemierko A, Drumm M, Heney NM, et al. Long-term outcomes after bladder-preserving tri-modality therapy for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an updated analysis of the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Eur Urol. 2017;71(6):952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chemoradiotherapy with or without atezolizumab in treating patients with localized muscle invasive bladder cancer (S1806).

- 40.Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in combination with chemoradiotherapy (CRT) versus CRT alone in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (MK-3475-992/KEYNOTE-992).

- 41.Nivolumab plus chemoradiotherapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) not undergoing cystectomy (REQ-0000020479).

- 42.Weickhardt AJ, Foroudi F, Lawrentschuk N, Galleta L, Seegum A, Herschtal A, et al. Pembrolizumab with chemoradiotherapy as treatment for muscle invasive bladder cancer: a planned interim analysis of safety and efficacy of the PCR-MIB phase II clinical trial (ANZUP 1502). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:485. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atezolizumab after chemo-radiotherapy for MIBC patients not eligible for radical cystectomy (UC-0160/ 1715).

- 44.Cuellar MA, Medina A, Girones R, Valderrama BP, Font A, Juan-fita MJ, et al. Phase II trial of durvalumab plus tremelimumab with concurrent radiotherapy as bladder-sparing therapy in patients with localized muscle invasive bladder cancer: a SOGUG study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:TPS5097–TPS. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vázquez-Estévez S, Fernandez Calvo O, Alvarez-Fernandez C, Bonfill T, Domenech M, GarcIa SAnchez J, et al. Efficacy of atezolizumab concurrent with radiotherapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (SOGUG-2017-A-IEC(VEJ)-4). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:TPS601–TPS. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiss B, Volkmer AK, Feng D, McKenna KM, Mihardja S, Chao M, et al. Magrolimab and gemcitabine-cisplatin combination enhance phagocytic elimination of bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e17035–e. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuo T, Miyata Y, Mitsunari K, Ohba K, Sakai H. Long-term outcomes of patients with locally advanced bladder cancer that underwent intra-arterial chemotherapy with/without radiotherapy for organ preservation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:574. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choudhury A, Nelson LD, Teo MTW, Chilka S, Bhattarai S, Johnston CF, et al. MRE11 expression is predictive of cause-specific survival following radical radiotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70(18):7017–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawashima A, Nakayama M, Kakuta Y, Abe T, Hatano K, Mukai M, et al. Excision repair cross-complementing group 1 may predict the efficacy of chemoradiation therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Efstathiou JA, Mouw KW, Gibb EA, Liu Y, Wu C-L, Drumm MR, et al. Impact of immune and stromal infiltration on outcomes following bladder-sparing trimodality therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76:59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Batista da Costa J, Gibb EA, Bivalacqua TJ, Liu Y, Oo HZ, Miyamoto DT, et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine-like bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019:clincanres.3558.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grivas P, Bismar TA, Alva AS, Huang H-C, Liu Y, Seiler R, et al. Validation of a neuroendocrine-like classifier confirms poor outcomes in patients with bladder cancer treated with cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Urol Oncol. 2020;38:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]