Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), and oxygen (O2) are important physiological messengers whose concentrations vary in a remarkable range, [NO] typically from nM to several μM while [O2] reaching to hundreds of μM. One of the machineries evolved in living organisms for gas sensing is sensor hemoproteins whose conformational change upon gas binding triggers downstream response cascades. The recently proposed “sliding scale rule” hypothesis provides a general interpretation for gaseous ligand selectivity of hemoproteins, identifying five factors that govern gaseous ligand selectivity. Hemoproteins have intrinsic selectivity for the three gases due to a neutral proximal histidine ligand while proximal strain of heme and distal steric hindrance indiscriminately adjust the affinity of these three gases for heme. On the other hand, multiple-step NO binding and distal hydrogen bond donor(s) specifically enhance affinity for NO and O2, respectively. The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis provides clear interpretation for dramatic selectivity for NO over O2 in soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) which is an important example of sensor hemoproteins and plays vital roles in a wide range of physiological functions. The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis has so far been validated by all experimental data and it may guide future designs for heme-based gas sensors.

Keywords: sliding scale rule, soluble guanylate cyclase, gaseous ligand selectivity, heme sensor/binding proteins

Graphical Abstract

The gaseous ligand selectivity of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) obeys the “sliding scale rule”. sGC excludes oxygen binding through the proximal strain of heme and enhanced affinity for NO by multiple-step NO binding.

1. Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide (NO), and oxygen (O2) are small diatomic gas molecules similar in molecular size and water solubility. They are generated in living organisms by various pathways and often play important messenger roles to trigger various physiological responses [1,2]. To sense these gaseous messengers, living organisms have evolved a variety of machineries, among which heme sensor proteins are widely distributed [3]. Binding of NO, CO, or O2, referred to as gaseous ligands hereinafter, to prosthetic heme leads to conformational change(s) in heme sensor proteins, initiating downstream response cascades. Although the gaseous ligands differ only by one 2p electron from CO to NO to O2, the difference in their electronic configuration leads to sharp difference in their affinity for heme [4,5]. On the other hand, concentrations of these molecules fluctuate widely at different locations in living organisms and in their environments; physiological [NO] typically varies from nM to several μM [6], [O2] can reach up to hundreds of μM, while [CO] varies between 2.1 to 5.0 nM [7,8,9]. Heme sensor proteins therefore face the challenge to selectively bind one of these molecules in the presence of the other two. There have been extensive studies on the mechanism of gaseous ligand selectivity in a variety of hemoproteins. One important example of heme sensor proteins is the only mammalian NO receptor soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), exhibiting an extremely high affinity for NO but excludes any binding of O2. The remarkable selectivity of sGC among the gaseous ligands enables it to sense less than nM NO under aerobic conditions, where [O2] is ~ 260 μM. The underlying mechanism of this phenomenal gaseous ligand selectivity of sGC has been investigated for more than 40 years. Only recently a clear picture gradually evolved, based on structural and kinetic data from various heme models and hemoproteins including sGC and its structural analog bacterial Heme NO/OXygen-binding proteins (H-NOXs). In this short review, we will discuss the factors that determine ligand selectivity of heme sensor proteins with a focus on the gaseous ligand discrimination by sGC and its NO binding.

2. sGC Selectively Binds NO but not O2

sGC is the only authentic mammalian heme-based sensor and acceptor for NO leading to stimulation of downstream pathway. For example, in human cardiovascular and pulmonary systems, NO synthesized from L-arginine by endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the endothelium of blood vessels diffuses to platelets or adjacent vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and interacts with cytosolic sGC, leading to several hundred fold activation of its guanosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) synthesis activity. The increased level of cGMP stimulates cGMP effectors including cGMP-specific protein kinase, phosphodiesterases, and cyclic nucleotide gated channels; leading to a variety of cellular and physiological events. The effects of sGC activation include calcium sequestration and cytoskeletal changes, relaxation of VSMCs and improved oxygenation of tissues and organs [10], facilitation of the repair of injured endothelium [11,12], inhibition of adhesion and subsequent migration of leukocytes [13], reduction of platelet aggregation [14,15], and inhibition of proliferation and migration of VSMCs [16]. It is not surprising that sGC is an important and active therapeutic target. NO-generating nitrovasodilators such as nitroglycerin and isosorbide mononitrate are used to up-regulate sGC function to manage heart failure, angina, and hypertensive crisis [17].

sGC is a heterodimer, consisting of an α and a β subunits, each containing an H-NOX domain, a Per-Arnt-Sim domain (PAS), a coiled-coil domain (CC), and a catalytic domain (CAT). Only the β H-NOX domain contains a heme prosthetic group [18,19,20,21,22]. Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) of dimeric sGC shows a two-lope structure with the H-NOX/PAS domains on one end and the CAT domains on the other, connected by the CC domains. The structure reveals that β CC helix has a contact with the β H-NOX domain and the CC domains form a bend in inactive sGC [23,24]. NO binding to the heme triggers a relative rotation among α and β CC helices and unbending in the CC domains while maintaining the β CC helix contact with the β H-NOX domain. Transduction of the CC rotation to the CAT domains leads to rotation in the latter and formation of a binding pocket with more optimal binding of substrate GTP and the catalysis of cGMP synthesis [23,24]. CO also binds to sGC but its binding only leads to a fourfold stimulation of enzymatic activity over the basal level [18,19]. Intriguingly, there is no O2 binding to sGC even at concentrations as high as 1.3 mM (solubility of 1 atm O2 in aqueous solution [25]). This dramatic ligand selectivity enables sGC to sense minimal NO signal in the presence of enormous amount of O2 [26]. How does sGC exhibit such power in discriminating NO and O2? Recently proposed “sliding scale rule” provides a clear explanation for this puzzle.

3. The “Sliding Scale Rule” Hypothesis

The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis is derived from the binding data of all three gaseous ligands from hundreds heme model compounds and hemoproteins with varying protein folds to interpret the gaseous ligand selectivity in a plethora of hemoproteins, including sGC [27]. Through the bioinformatic graphical analysis of gaseous ligand affinity data versus gaseous ligand type, it reveals a general pattern in the gaseous ligand binding to hemoproteins [4,27]. Since its proposal, complete kinetics data were obtained for several additional hemoproteins; and all these data corroborate the pattern revealed by the “sliding scale rule” [28,29,30,31]. The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis identifies five key factors that govern the gaseous ligand selectivity of hemoproteins: (i) the identity of the proximal ligand; (ii) the proximal strain of heme; (iii) distal steric hindrance; (iv) hydrogen-bond (H-bond) donor(s) in the distal pocket; and (v) multiple-step NO binding (Fig. 1). The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis emphasizes that a five-coordinated (5c) heme ligated to a neutral histidine possesses intrinsic selectivity for NO, CO, and O2 while protein-derived structural elements modify this intrinsic selectivity to adapt to different functional requirements (Fig. 1). Since the proposal of the “sliding scale rule”, the governing power of these five factors for gaseous ligand binding in hemoproteins has been further substantiated in several recent studies. In the following sections, each factor is discussed in more details, emphasizing new enlightenment revealed by recent studies. Two recent data which provide new insights into gas ligand selectivity by hemoproteins are also discussed.

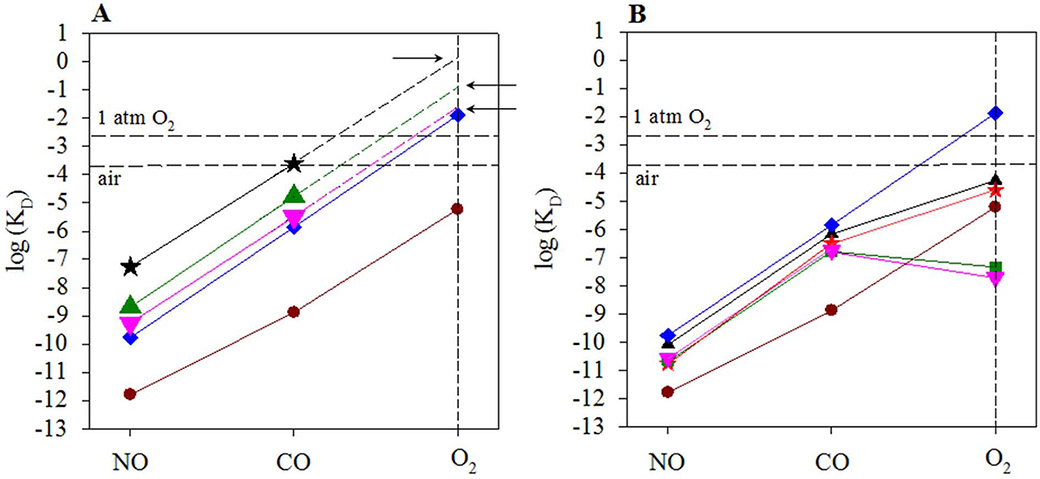

Figure 1. Major factors that govern the “sliding scale rule” hypothesis.

The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis is illustrated using binding data from sGC, two bacterial H-NOXs, Cyt c’, and heme model PP(1-MeIm). The logarithms of experimentally measured KD values of hemoproteins and model compounds to NO, CO, and O2 (red symbols) are plotted versus ligand type. Circle, PP(1-MeIm); star, sGC; up triangle, Cyt c’; down triangle, L16A Cyt c’; diamond, Ns H-NOX; square, Cs H-NOX. The horizontal dashed line in each panel represents 1atm O2. (A) The lines connect log KD(NO) to log KD(CO) to log KD(O2) of 5c heme ligated to a neutral histidine are approximately straight in both heme models and hemoproteins, due to the intrinsic binding affinity of 5c heme to the gaseous ligands. The approximate linearity of log KD(NO)-log KD(CO)-log KD(O2) lines is represented with a scale ruler symbol. The lines for different hemoproteins and heme models are parallel, symbolized by a sliding scale along the ordinate (purple open double-sided arrow), hence the term of “sliding scale rule”. The increased KDs of sGC and Ns H-NOX compared to PP(1-MeIm) are governed by proximal strain (green solid arrow). The star connected by a red dashed line to log KD(CO) of sGC is the predicted log KD(O2) of sGC. (B) Mutating distal L16 of Cyt c’ to alanine removes distal steric hindrance, leading to large decrease in KDs of L16A Cyt c’ for all three gases, represented by a green solid arrow. The large range of KD values is represented by a purple open double-sided arrow. (C) The stability of oxyferrous heme in Cs H-NOX is enhanced by its distal Y140 as a H-bond donor, leading to a dramatically decreased KD(O2) (green solid arrow) but little effect on either KD(CO) or KD(NO). The square connected to log KD(CO) by a dashed line is the predicted log KD(O2) of Cs H-NOX by linear extrapolation of log KD(NO)-log KD(CO). (D) The conversion of 6c NO-heme complex to 5c NO-heme complex in the multiple-step NO binding of sGC and other hemoproteins leads to KD(NO)apparent << KD(NO)6c; the change is represented by a green solid arrow. The log KD(NO)apparent is indicated by a red cross.

3.1. Intrinsic gaseous ligand selectivity of hemoproteins

The significantly different affinities for NO, CO, and O2 observed in some hemoproteins root in the intrinsic property of the heme ligated to a neutral histidine proximal ligand. Such intrinsic gaseous ligand selectivity is well manifested by heme model compound protoporphyrin IX 1-methylimidazole (PP(1-MeIm)), which shows remarkably large affinity ratios, KD(CO)/KD(NO) ≈ KD(O2)/KD(CO) ≈ 103 – 104 (Fig. 1A). This pronounced difference in the binding affinity of PP(1-MeIm) for NO, CO, and O2 is determined by the optimal strength of a proximal neutral imidazole ligand. Such significant intrinsic gaseous ligand selectivity is borne out in many hemoproteins with a proximal histidine ligand, such as globins, sGC, and bacterial H-NOXs [27]. Hemoproteins also bear other types of proximal ligands, such as imidazolate in many peroxidases [32], cysteine thiolate in cytochrome P450s [33], or tyrosine phenolate anion in catalase [32]; however, these ligands have more electron donating property and are therefore much stronger ligands, which suppress differential in affinity for NO, CO, and O2, leading to the so-called “leveling effect” [27]. For simplicity, hemoproteins in the following text only refer to those with a 5c heme ligated to a neutral histidine. Due to approximately equal affinity ratios between two ligand pairs, KD(CO)/KD(NO) ≈ KD(O2)/KD(CO), the logarithms of the gaseous ligand affinity (log KD(NO), log KD(CO), and log KD(O2)) in a hemoprotein fall on an approximately straight line when plotted as a function of the ligand type (Fig. 1A). Moreover, such lines in different hemoproteins parallel each other due to the similar values of the ligand affinity ratios. An immediate application based on the linearity of these log KD(NO)-log KD(CO)-log KD(O2) lines is that, as long as the affinity of one gaseous ligand is known, it is possible to estimate the affinity of other gaseous ligand(s) which is difficult to measure. For example, KD(O2) for sGC can be estimated to be ~1.3 M, by drawing a line through its measured KD(NO) or KD(CO) parallel to the data obtained for a heme model (Fig. 1A).

The 103 – 104 fold intrinsic selectivity between NO/CO and between CO/O2 afforded by a neutral histidine-ligated heme may be inadequate for a hemoprotein to selectively bind NO, CO, or O2 whose levels vary in a range wider than 103 – 104 inside living organisms or in their environments. The concentration of O2 in aqueous solution under atmospheric pressure reaches ~260 μM, on the other hand, the basal [NO] inside a living organism is only around pM. Moreover, the level of NO, CO, and O2 also fluctuates dramatically inside living organisms under different physiological and pathological conditions. To meet such a large dynamic range of gas sensing, hemoproteins have evolved mechanisms to modulate the intrinsic discriminating ability of a neutral histidine-ligated heme for gaseous ligands either in a non-selective way, where the affinity for all three gaseous ligands are uniformly adjusted, or selectively for either O2 or NO. Two major protein-dependent factors which uniformly shift the intrinsic affinity of hemoproteins for all three gaseous ligands are the proximal strain of heme and steric hindrance on the distal side of heme.

3.2. Proximal strain of heme

Proximal strain adjusts the Fe-His bond strength between heme and its proximal histidine ligand [34,35,36], modulating the bond formation between heme Fe atom and a ligand on the distal side by regulating both on-rate (kon) and off-rate (koff) of a gaseous ligand to and from the heme, respectively (Fig. 1A) [27]. The Fe-His bond strength in a hemoprotein compared to a heme model compound(s) attunes the intrinsic affinity of heme for all three ligands but maintain the affinity ratios. For example, sGC shows two-order lower affinity for all three gases compared to bacterial H-NOXs (Fig. 1A) [30], which is most likely due to the elevated proximal strain in sGC as suggested by several experimental data. First, sGC has a longer Fe-His bond than bacterial H-NOXs [23,37,38,39]. The longer and weaker Fe-His bond in 5c sGC compared to that in model heme or typical b-type hemoproteins like myoglobin is corroborated by infrared spectroscopy (IR) data for sGC, νFe-His = 204 cm−1. Moreover, IR data also shows a weak Fe-CO bond in CO-bound sGC, with νFe-CO = 472 cm−1 [40,41]. Second, the midpoint potential (EM) of sGC from different species, +187 mV for human sGC and +234 mV for sGC from Manduca sexta (Ms sGC), is very high for a hemoprotein with a histidine proximal ligand, such as myoglobin and other b-type hemoproteins [42,43]. These values are in line with the striking difference of His-Fe bond strength in sGC, as compared to other hemoproteins. As discussed below, it was recently revealed that the proximal strain in the β1 H-NOX domain of sGC is partially due to the interactions between its α and β subunits and between the different domains in its β subunit.

The bacterial H-NOXs, whose affinity for the three gaseous ligands have been measured, all have a single domain structure, either the stand-alone protein in a facultative anaerobe, such as the H-NOXs from Nostoc sp. PCC7120 (Ns H-NOX), Shewanella oneidensis (So H-NOX), and Vibrio cholera (Vc H-NOX) [28,30], or the H-NOX domain of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP) in an obligatory anaerobe, such as Clostridium botulinum (Cb H-NOX) and Caldanaerobacter subterraneus subsp. tengcongensis (Cs H-NOX)i [29,44,45,46]. sGC, on the other hand, is a heterodimer (α and β subunits) each containing multiple domains. Recently, the KD(CO) of sGC β1 H-NOX was shown to be modulated by the interactions between the α and β subunits and between the domains in its β subunit [47]. Truncated β1(1-380) of Ms sGC including H-NOX, PAS, and CC domains, has a KD(CO) = 0.2 μM, which is slightly lower than those of bacterial H-NOXs but more than 3 orders of magnitude lower than that of full length sGC, KD(CO) = 260 μM [47]; its heterodimers with truncated α1(49-450) and α1(272-450) have KD(CO) = 50 and 2.2 μM, respectively, revealing a reverse correlation with the extent of α1 truncation [47]. Dimerization with the α1 subunit therefore decreases the CO-binding affinity of the β1 H-NOX, suggesting that wild-type sGC is in an “inhibitory” form with low affinity for CO, and removal of the α1 subunit removes the inhibition and restores the intrinsic high-affinity CO binding of the β1 H-NOX. Furthermore, other domain(s) of the β1 subunit also modulates its affinity for CO. This is indicated by the decrease in KD(CO) value from 127 μM to 15 μM and to 1.6 μM for wild type bovine sGC (Bt sGC, α1(1-691)/β1(1-619)), and Bt sGC β1(1-359) and β1(1-197) constructs, respectively [47]. To complete the data set of gaseous ligand affinity in Bt sGC β1(1-359) and β1(1-197), we examined the affinity of these sGC constructs for NO and O2 (Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S1, Supplementary Information). Although KD(NO) of sGC β1(1-197) could not be experimentally determined, Bt sGC β1 (1-359) shows significantly stronger affinity for NO than full length sGC, but has no affinity for O2 (Table S1), corroborating the “sliding scale rule”. Although no oxyferrous complex is observed in Bt sGC β1(1-359), ferrous Bt sGC β1(1-359) slowly autoxidizes in prolong incubation with O2 (Fig. S3A, inset), in line with stronger affinity for all three gaseous ligands in this construct compared to full length sGC. Overall, these data and the previous study suggest that the interactions between the α1 and β1 subunit and between the β1 domains in sGC weaken its Fe-His bond and lead to weaker gaseous ligand affinity. The mechanism of modulation in Fe-His bond strength by the subunit-subunit and the domain-domain interactions in sGC calls for further investigation. Modulation of gaseous ligand affinity by subunit-subunit interaction is also found in hemoglobin (Hb), which shows significantly stronger affinity for all three gases in its R-state than T-state [35]. It will also be interesting to measure the affinity of Cb and Cs H-NOX domains in full length MCPs and compare with those of isolated Cb and Cs H-NOXs [29,44].

Overall, sGC achieves exclusion of O2 binding by profoundly decreasing its intrinsic affinity for all three gases through significant proximal strain of its heme exerted by its structural fold as a whole (Fig. 1A). The exclusion of O2 binding in sGC is astonishing, as no O2 binding to sGC is observable even in O2 saturated buffer. The KD(O2)sGC can be predicted by the “sliding scale rule” to be ~ 1.3 M, far higher than [O2] in solution under 1 atm pure O2 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Gaseous ligand selectivity in truncated sGC and H-NOX proline mutants.

Logarithms of KDs of sGC, bacterial H-NOXs, and mutants are plotted versus ligand type. (A) black star, sGC; green up triangle, sGC β1(1-359), conformer 1; pink down triangle, sGC β1(1-359), conformer 2; blue diamond, Ns H-NOX; purple circle, Fe(II) PP(1-MeIm). Horizontal dashed lines, [O2] with air or 1 atm O2. Arrows, projected KD(O2)s for sGC and sGC β1(1-359) based on the “sliding scale rule” hypothesis. (B) Black up triangle, Cb H-NOX; red star, P114A Cb H-NOX; green square, Cs H-NOX; pink down triangle, P115A Cs H-NOX. Blue diamond, Ns H-NOX; purple circle, Fe(II) PP(1-MeIm).

Proximal strain of heme could also be fine-tuned by the orientation of the imidazole ring of proximal histidine relative to the tetrapyrroles of heme porphyrin. Two types of conformers due to such orientation are observed, an “eclipsed” conformation where the imidazole ring approximately parallels the line connecting the nitrogen atoms of two opposite heme pyrroles, and a “staggered” conformation where the imidazole ring roughly parallels the line connecting two opposite methine carbons of the heme [4,35]. A “staggered”, or more relaxed conformation, observed in L16A cytochrome c’ (Cyt c’) [48,49,50] and H16L leghemoglobin (Lb) [51,52,53], renders the heme much stronger affinity for gaseous ligand than an “eclipsed”, more constrained conformation, as observed in myoglobin (Mb) and its mutants [35,54,55,56]. The recent cryo-EM structure of sGC shows that the imidazole ring of proximal His105 adopts an “eclipsed” conformation [23]. Heme model protoporphyrin IX 1-methylimidazole (PP(1-MeIm)) does not have protein component to hold the orientation of its imidazole ring, leading to significant flexibility in ring rotation and therefore exhibits affinity for gaseous ligands between those of L16A Cyt c’ and Mb.

3.3. Distal steric hindrance

Some hemoproteins modulate the association with and dissociation from the heme of a gaseous ligand, therefore modifying its kon and koff, by steric hindrance of a bulky amino acid sidechain(s) on the distal side of the heme [50,57]. Just like proximal strain, distal steric hindrance in a hemoprotein indiscriminately lowers the affinity of its heme for all three gaseous ligands. Distal steric hindrance is best exemplified by the profound effect of a single L16A mutation on KDs of L16A Cyt c’. In L16A Cyt c’, replacing bulky Leu16 with alanine in the heme distal pocket removes the distal steric hindrance. Such replacement leads to large increase in kon and decrease in koff, resulting in an increase of ~ 8 orders of magnitude in affinity of L16A Cyt c’ for all three ligands than wt Cyt c’ (Fig. 1B) [27,57]. On the other hand, the near diffusion-limited kon(NO) in sGC indicates that NO binding is unimpeded in sGC, despite the bulky Phe74 is located near heme iron on the distal side of sGC, likely imposing some “distal steric hindrance” [23].

A factor conceptually similar to “distal steric hindrance” factor is “distal pocket bulkiness” which is proposed to explain the gaseous ligand selectivity in Cs H-NOX. Introducing a bulky residue sidechain(s) into Cs H-NOX heme distal pocket leads to a decrease in its affinity for O2, although the effects on NO and CO binding is not determined [58,59]. The effects of such mutations include increased flexibility of heme, weakening of H-bonding to bound O2, and changing in conformation of the imidazole ring of the proximal histidine ligand [58,59,60], and the structural and kinetic changes depend heavily on which residue is mutated. However, compared to the effect of “distal steric hindrance” factor in gaseous ligand binding established using L16A Cyt c’, the data for establishing the “distal pocket bulkiness” factor is much less in extent and rather non-specific [50,57].

Through proximal strain and/or distal steric hindrance, hemoproteins dramatically expand their range of affinity for NO, CO, and O2 by about 8 – 9 orders of magnitude, without altering the intrinsic KD(CO)/KD(NO) and KD(O2)/KD(CO) ratios of a neutral histidine-ligated heme [27]. The modulation power of protein structural elements is demonstrated by the approximately parallel log KD(NO)-log KD(CO)-log KD(O2) lines of different hemoproteins, vertically sliding in a dynamic range of ~ 9 orders of magnitude (Fig. 1A and B). The term “sliding scale rule” is derived from the parallel lines of logKD (Fig. 1A and B).

Hemoproteins do not always attune the affinity of heme for the three gaseous ligands equally. In many cases, hemoproteins enhance the affinity of heme for only one of the gases, particularly NO or O2. In these hemoproteins, the log KD(NO)-log KD(CO)-log KD(O2) lines bend down on either end, appearing as deviation or outlier to the “sliding scale rule” paradigm (Fig. 1C and D). The non-selective modulation for the affinity of each gaseous ligand and selective modulation for a particular gas are often combined to meet the functional requirement of a hemoprotein. Some hemoproteins that function as sensor or transporter for O2 boost their affinity for O2 through a distal H-bond donor(s). On the other hand, the affinity of sGC for NO is selectively enhanced to compensate for the substantially weakened affinity for all three gases through the proximal strain to exclude O2 binding; this phenomenal selectivity for NO in sGC, also in other H-NOXs, is achieved through multiple-step NO-binding mechanism. Such selectivity is elaborated below.

3.4. Distal hydrogen bond donor

A H-bond donor(s) in a hemoprotein forms H-bond to heme-bound O2 and stabilizes the oxyferrous complex, leading to a significantly decreased KD(O2) with little or no effect on CO or NO binding (Fig. 1C). In many hemoproteins, distal H-bond donor(s) is often the most effective way to enable them to bind O2, since O2 has the lowest intrinsic affinity for heme and an oxyferrous complex is often unstable without additional means of stabilization. Distal histidine in Hb and Mb are good examples with distal H-bond donors that stabilize oxyferrous heme (Fig. 1C) [4]. The major factor in discriminating NO, CO, and O2 in Mb or Hb is ascribed to this electrostatic H-bond donor [61]. However, existence of a distal H-bond donor(s) is certainly not the only factor to enable O2 binding in a hemoprotein; L16A Cyt c’, which shows a strong affinity for O2, KD(O2) = 49 nM, is a perfect illustration of how protein-dependent environments are able to regulate O2 binding without a H-bond donor in certain hemoproteins [50].

In bacterial H-NOXs, it is noticed that several bacterial H-NOXs from obligatory anaerobic bacteria, such as Cb and Cs H-NOXs, have a tyrosine, Tyr139 and Tyr140, respectively, in the distal pocket; both Cb and Cs H-NOXs exhibit strong affinity for O2 [29]. The crystal structure of Cs H-NOX shows that Tyr140 forms an H-bond to its oxyferrous complex [39]. On the other hand, H-NOXs from facultative bacteria, such as Vc and So H-NOXs do not have distal H-bond donor and exhibit no measurable affinity for O2. Moreover, removing H-bond donor in Cb and Cs H-NOXs leads to no measurable affinity for O2 in Y139F Cb H-NOX and Y140F Cs H-NOX [29,46]. A distal H-bond donor is therefore sufficient to render O2 binding in bacterial H-NOXs. Based on the observations of H-NOXs, it is deduced that the lack of a distal pocket H-bond donor in sGC eliminates O2 as a ligand, leading to its selectivity for NO [62,63]. However, experimental data show that introduction of a H-bond donating tyrosine residue in the vicinity of the distal side of sGC heme (I145Y sGC) does not lead to O2 binding [64], highlighting some crucial difference between sGC and its bacterial H-NOX analogs. Due to the lack of the 3D structure of I145Y sGC, it is hard to confirm that the side chain of introduced Tyr145 is oriented optimally for H-bonding to O2 ligand, nevertheless, the study suggests that distal H-bond donor(s) may not be an efficient factor to introduce O2 binding in some hemoproteins.

3.5. Multiple-step NO binding

Multiple-step NO binding dramatically enhances the apparent affinity for NO in a hemoprotein and is best demonstrated by the NO binding in sGC. In the presence of stoichiometric or substoichiometric amount of NO, sGC binds NO reversibly to form a 6-coordinate (6c) NO-heme complex at kon = 1.4 × 108 M−1s−1 and koff, 6c = 27 s−1, yielding an intrinsic KD(NO) = koff, 6c(NO)/kon(NO) = 54 nM (Fig. 3, A ↔ B) [27,45]. This KD(NO) indicates that NO binding is not very strong in sGC with the initial formation of the 6c NO-heme complex. Once formed, the Fe-His bond in the 6c NO-heme complex breaks at a rate of 8.5 s−1, irreversibly converting to a 5-coordinate (5c) NO-heme complex with NO on the distal side (5c NOd) (Fig. 3, B → E). On the other hand, in the presence of excess NO, the initially formed 6c NO-heme complex in sGC reacts with another NO at kon = ~106 M−1s−1 and koff = 26 s−1, forming a transient quaternary complex which irreversibly converts to another 5c NO complex at > 600 s−1, with NO sitting on the proximal side (5c NOp) (Fig. 3, B ↔ C → D) [65]. Either 5c NOd or 5c NOp has a significantly lower dissociation rate constant than 6c NO-heme, koff, 5c(NO) ~ 1.1 × 10−3 M−1 << koff, 6c(NO), therefore conversion of 6c to either 5c complex results in KD(NO)apparent = koff, 5c(NO)/kon(NO) = 7.1 pM (Fig. 2D), dramatically enhancing the apparent affinity of sGC for NO [27]. Such NO affinity enhancement through multiple-step NO binding is also seen in many other hemoproteins, such as bacterial Vc and So H-NOXs. Similar to sGC, formation of the 5c NO complex in bacterial H-NOXs leads to much decreased KD(NO)apparent = 1 – 7.3 pM [28,29,30]. The conversion of a 6c NO-heme complex to a 5c NO-heme complex is due to the strong negative trans effect of NO which weakens Fe-His bond opposite of NO, therefore, multiple-step NO binding is a mechanism which leads to enhancement in NO affinity only [49].

Figure 3. Multiple-step NO binding in sGC.

sGC (A) binds to NO to form a 6c NO-heme complex (B) reversibly with rate constants, k1 = 1.4 × 108 M−1s−1 and k−1 = 27 s−1 [27]. The 6c NO-heme complex subsequently converts to a 5c NO-heme complex (E, 5c NOd) irreversibly due to the rupture of Fe-His bond, at a rate of k4 = 8.5 s−1 [27]. In the presence of excess NO, a second NO binds to B to form a transient ternary complex (C) with rate constants, k2 = ~ 106 M−1s−1 and k−2 = 26 s−1 [27]. Species C irreversibly converts to another 5c NO-heme complex (D, 5c NOp) rapidly at a rate > 600 s−1 (k3), from both Fe-His bond rupture and dissociation of distal NO. Both 5c NOd and 5c NOp have very small NO dissociation rate, ~10−3 – 10−4 s−1 (k5). Reverse reaction from 5c NOp (D) to C (k−3) is assumed to happen readily in certain study but it is not supported by kinetic study (marked by a question mark) [69]. Species F, with an S-nitrosylthiol radical anion probably in sGC PAS domain, is proposed to be the 100% activated form in the presence of excess NO [70,73], however, this S-nitrosation is unrelated to NO selectivity in sGC.

There has been controversy whether 5c NOp is formed in sGC in the presence of excess NO since distal- and proximal-specific 5c NO-heme complexes, or 5c NOd and 5c NOp, are indistinguishable via optical spectroscopy or electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) method. The 5c NOp complex is found in the crystal structures of Cyt c' from Alcaligenes xylosoxidans [49] and So H-NOX [66]. One study addresses the sidedness of 5c NO-heme in sGC using sequential stopped-flow to follow the spectral change in sGC reacting with stoichiometric or excess NO, and parallel two-stage rapid-freeze quench EPR to exam the hyperfine EPR structure of the trapped 5c NO-heme complex, reacting sGC first with 14NO and then 15NO, or vice versa [65]. EPR data of the final 5c NO-heme complex trapped using varying levels of 14NO and 15NO indicate that the 2nd NO binds to the proximal side of the heme. This data suggests that either 5c NOd or 5c NOp, formed in sGC in the presence of stoichiometric and excess NO, respectively, activates sGC similarly, in line with the study showing that either 5c NOd or 5c NOp leads to similar spiking cGMP formation [67].

Another study follows the time-resolved absorption change in NO rebinding to heme after photolysis of 5c NO-heme complex in sGC [68]. Other than germinate NO rebinding to heme with a τ = 6.5 ns, 2nd order rebinding of NO to sGC (20 μM) proceeds with τ = 250 μs (1× NO) and 50 μs (10× NO); and the formed 6c NO-heme converts to 5c NO-heme with τ = 43 ms and 10 ms, respectively [68]. Due to lack of the detection of dinitrosyl heme (Fig. 3. C), it is concluded that NO only binds heme from distal side within millisecond time scale. However, transient formation of dinitrosyl heme is not excluded [68]. In another study in much longer time scale, the sidedness of 5c NO-heme complex in So H-NOX is inferred from the distance between NO and a spin label attached to So H-NOX measured by double electron-electron resonance (DEER) [69]. It is found that 5c NOd is prominent at both < 1× and excess NO treatments of So H-NOX. For this to happen, it is assumed that the 6c NO-heme to 5c NO-heme conversion in the presence of excess NO is highly reversible (Fig. 3, C ↔ D) [69]. However, this assumption is at odds with the kinetic measurements showing that So H-NOX reacts with excess NO to generate 5c NOp irreversibly at a rate > 600 s−1 [27,30,45]. The conclusion by DEER study also contradicts the structural data which show 5c NOp in the crystal structure of So H-NOX reacted with excess NO [66].

When reacting with excess NO, certain cysteine residue(s) in sGC are proposed to form S-nitrosylthiol radical anion (−RSNO. −), albeit empirical explanation seems supporting the existence of such radical anion, direct evidence such as EPR characterization, remains to be provided [70]. It is also hard to rationalize the observed heme spectral change caused by a cysteine nitrosylation. Such secondary cysteine modification has been proposed to be necessary for full activation of sGC and the initial NO binding to heme is shown to only partially activate sGC [70,71,72,73]. On the other hand, a variety of sGC stimulators and activators, such as YC-1 [74,75,76], BAY 41-2272 [77], BAY 58-2667 [78], HMR-1766 [79], and BAY 60-2770 [80], stimulate sGC either by sensitizing sGC to CO and NO or through a heme-independent mechanism. However, these sGC activation mechanisms are unlikely linked directly to selective NO binding in sGC.

4. Other Factors Proposed to Affect Gaseous Ligand Binding

In addition to the factors determined in the “sliding scale rule” hypothesis, several other factors have been proposed to address the selectivity of gaseous ligands in sGC and bacterial H-NOXs.

4.1. Hydrophobic heme pocket

It is noticed that the distal heme pocket in sGC is quite hydrophobic [23], potentially favoring binding of a gaseous ligand [81,82]. However, due to the similar physical properties of the three gaseous ligands, hydrophobicity of heme pocket unlikely shows significant discrimination among the three gases. So far there is no detailed kinetic study to evaluate any effect of the hydrophobicity of distal pocket on selective binding of gaseous ligands in hemoproteins.

4.2. Ligand access path

Efforts have been made to probe the access path(s) for gaseous ligands onto the distal side of heme and a Y-shaped gas access channel is identified by equilibrium xenon (Xe) binding site(s) in Ns H-NOX [66,83]. Moreover, kinetics of CO binding is found to be modified in the H-NOX mutants using bulky tryptophan to replace key residues lining the tentative channel(s) [66,83]. The identification of such channels raised several concerns: (i) CO is not an appropriate ligand to assess kinetic binding for its intrinsically much smaller kon to ferrous heme than those of NO or O2, due to spin limitation [84]; (ii) it is demonstrated that thermodynamic Xe binding to hemeprotein does not necessarily represent the kinetic ligand access to the iron [85]; (iii) the near diffusion-limited kon of both NO and O2 binding in sGC and several H-NOXs [27,30] indicate little restriction in ligand access; and (iv) it is revealed in several crystal structures of H-NOXs [37,38,39]; a much shorter ligand path from the solvent leading directly to the side of the heme and is proposed to be a more efficient alternative path [30]. Both Y-shaped gas access channel and the short access path are noted in a recent molecular dynamics (MD) calculation on Ns and So H-NOXs. The MD calculations also identifies a third channel and Ns and So H-NOXs show different preference for these channels [86]. Overall, the near diffusion limit kon(NO) rate constants in bacterial H-NOXs and sGC suggest that gas access channel(s) in these hemoproteins does not play any significant role in their gaseous ligand selectivity.

4.3. Heme distortion

Structural data of several bacterial H-NOXs show that the heme is significantly distorted from planar geometry and such heme deformation is proposed to modulate gaseous ligand affinity [38,87]. In sGC and all known bacterial H-NOXs, a conserved proline is located on the heme proximal side (Pro118 in sGC) [39]. The orthologous proline in Cs H-NOX (Pro115) or So H-NOX (Pro116) buttresses the heme porphyrin plane and promotes heme distortion in both H-NOXs [39,66]. Heme distortion caused by proline buttress is proposed to play a role in the gaseous ligand selectivity of the bacterial H-NOXs based on several lines of experimental observations. First, P115A Cs H-NOX has a flattened heme, a large +167 mV to −4 mV shift in EM, and a 217 to 223 cm−1 shift in resonance Raman (rR) νFe-His band, implying strengthening of the Fe-His bond [88]. However, rR data also indicated that Fe-CO bond strength remains unchanged and the Fe-O2 bond strength is even weakened [89]. P115A Cs H-NOX shows a slightly increased affinity for O2 compared to wild type Cs H-NOX, a 4.5× decrease in KD(O2), due to somewhat increased kon(O2) and slightly decreased koff(O2) [87]. Second, in bacterial H-NOX from Shewanella woodyi (Sw H-NOX), mutating the corresponding Pro117 to alanine results in a relaxed planar heme and a 10-fold increase in the coupled phosphodiesterase activity, similar to that by NO-activated Sw H-NOX [38].

The EM shift and increase in Fe-His bond strength in P115A Cs H-NOX compared with the wild-type suggest that the heme distortion leads to enhanced proximal strain in Cs H-NOX [87]. However, the enhancement in O2 affinity for P115A Cs H-NOX compared to wild type Cs H-NOX is rather small. Furthermore, the small KD(O2) of Cs H-NOX is mostly due to its distal H-bond donor, Tyr140, which does not play any significant role in the binding of NO and CO [29]. It is difficult to assess the proximal strain introduced by Pro115 only based on kinetic data of O2 binding. We therefore measured the kinetic and affinity of P114A Cb and P115A Cs H-NOXs for each gaseous ligand (Figs. S5 - S7 and Table S1, Supplementary Information). The gaseous ligand binding in P114A Cb and P115A Cs H-NOXs follows the “sliding scale rule” and the KD(NO), KD(CO), and KD(O2) of P114A Cb and P115A Cs H-NOXs show no significant change compared with those of wt Cb and Cs H-NOXs, respectively. On the other hand, these data suggest that the heme distortion introduced by the buttressing proline residue unlikely alters the proximal strain of heme in either Cb or Cs H-NOX and is not a major factor dictating the affinity and selectivity for gaseous ligands in these H-NOXs. The relationship between heme distortion and the proximal strain of heme warrants further investigation.

5. Summary and Perspective

The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis identifies five major factors determining the gaseous ligand selectivity of hemoproteins. This hypothesis elucidates the gaseous ligand selectivity by sGC as a result of: 1) the prosthetic heme ligated to a neutral His105 provides sGC intrinsic selectivity among NO, CO, and O2, 2) proximal strain of sGC heme governed by the subunit-subunit and the domain-domain interactions greatly decreases its affinity for all three gaseous ligands and achieve complete exclusion of O2; 3) multiple-step NO binding greatly enhances sGC effective affinity for NO.

The mechanism revealed by the “sliding scale rule” for sGC’s phenomenal NO selectivity may also have implications on a unified model on NO-activation, deactivation, and re-activation of sGC (Fig. 4). In the resting sGC with 5c unliganded ferrous heme, the strong proximal strain of heme renders sGC selectivity for NO. The dissociation of His105 and subsequent domain rearrangement upon NO binding to sGC release proximal strain of heme, leading to higher affinity for all three gaseous ligands (Fig. 4). Soluble guanylate cyclase may thus be deactivated through the NO-dioxygenation of the 5c NO-heme complex and the resulting ferric heme would facilitate re-ligation of His105 to regenerate oxidized 5c-sGC (Fig. 4). Oxidized sGC can be easily re-activated through reduction by either intrinsic or other cellular reductant to its ferrous resting state as a result of the high EM (Fe+3/Fe+2), ready for another round of NO-activation (Fig. 4). This model of activation, deactivation, and re-activation of sGC is solely based on NO and O2 interaction with heme and it will be tested in our future studies.

Figure 4. Possible mechanism for deactivating NO-activated sGC.

The Cryo-EM structures of sGC in different states are plotted using PyMol: oxidized state (PDB 6JT1, left), unliganded ferrous state (PDB 6JT0, middle), NO-bound activated state (PDB 6JT2, right). Domains in the three structures are marked using the same color scheme as labeled in the middle structure. Heme is represented using blue stick and His105 is represented using green stick. A molecule of phosphomethylphosphonic acid guanylate ester is bound in the NO-activated structure and is represented using spheres in salmon color. Ferrous sGC selectively binds NO, governed by strong proximal strain of heme, as shown in the “sliding scale rule” plot above the middle structure (red solid line). The rearrangement of domains in both α1 and β1 subunits is introduced upon NO binding which leads to His105 dissociation and a 5c NO complex (5c NOd or 5c NOp, represented inside the brackets under the right structure), generating an optimal binding site for GTP between α1 and β1 catalytic domains to produce cGMP. Dissociation of His105 releases the proximal strain of heme, which together with different domain-domain and subunit-subunit interactions due to domain rearrangement may result in high affinity for gaseous ligands. This hypothetical shift in gaseous ligand affinity is represented by the “sliding scale” plot above the right structure (red solid line), marked by a frame of broken line. Due to the increased gaseous ligand affinity, 5c NO complex may react with O2 to generate NO3− though NO-dioxygenation and therefore deactivates sGC (represented by the broken arrow). His105 re-associates with ferric heme iron to regenerate oxidized sGC (left structure) which can be reduced by either intrinsic or cellular reductant to its ferrous state (middle structure), ready for the next round of NO activation.

The “sliding scale rule” hypothesis is so far the most promising one to rationalize all data regarding the selective gaseous ligand binding and sensing of a multitude of hemoproteins; it provides a unified model for gaseous ligand selectivity in hemoproteins and thus deserves more extensive testing in the future to establish a new paradigm for gaseous ligand selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Proximal ligand, heme proximal strain and distal steric hindrance govern gas binding.

Distal hydrogen bonding enhances O2 affinity; multiple-step binding boosts NO affinity.

Proximal strain excludes O2 binding from soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC).

Multiple-step NO binding enables sGC efficient NO sensing.

“Sliding scale rule” provides insights into ‘deactivation’ and ‘reactivation’ of sGC.

Acknowledgments

Fund Information. This study is supported by E.G. R21EY026663 (EDG); E.M. R01 HL139838; A.-L. T. RO1 DH122784.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary Information

Supporting information to this article includes the experimental procedures and results of measuring kinetics and affinity of gaseous ligands for 1) two truncated sGC constructs, Bt sGC β1(1-359) containing the H-NOX, PAS, and partial CC domains; and Bt β1(1-197) containing only the H-NOX domain; 2) two H-NOX mutants, P114A Cb and P115A Cs H-NOXs.

Cs H-NOX was formerly known as Tt H-NOX (H-NOX from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Girvan HM, Munro AW, Heme sensor proteins, J Biol Chem 288 (2013) 13194–13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liebl U, Lambry JC, Vos MH, Primary processes in heme-based sensor proteins, Biochim Biophys Acta 1834 (2013) 1684–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shimizu T, Huang D, Yan F, Stranava M, Bartosova M, Fojtikova V, Martinkova M, Gaseous O2, NO, and CO in signal transduction: structure and function relationships of heme-based gas sensors and heme-redox sensors, Chem Rev 115 (2015) 6491–6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tsai AL, Martin E, Berka V, Olson JS, How do heme-protein sensors exclude oxygen? Lessons learned from cytochrome c', Nostoc puntiforme heme nitric oxide/oxygen-binding domain, and soluble guanylyl cyclase, Antioxid Redox Signal 17 (2012) 1246–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Spiro TG, Jarzecki AA, Heme-based sensors: theoretical modeling of heme-ligand-protein interactions, Curr Opin Chem Biol 5 (2001) 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT, The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics, Nat Rev Drug Discov 7 (2008) 156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Air Quality Guidelines/Carbon monoxide, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Coburn RF, Blakemore WS, Forster RE, Endogenous carbon monoxide production in man, J Clin Invest 42 (1963) 1172–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Coburn RF, Danielson GK, Blakemore WS, Forster RE 2nd, Carbon Monoxide in Blood: Analytical Method and Sources of Error, J Appl Physiol 19 (1964) 510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stasch JP, Becker EM, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, Dembowsky K, Feurer A, Gerzer R, Minuth T, Perzborn E, Pleiss U, Schroder H, Schroeder W, Stahl E, Steinke W, Straub A, Schramm M, NO-independent regulatory site on soluble guanylate cyclase, Nature 410 (2001) 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Noiri E, Hu Y, Bahou WF, Keese CR, Giaever I, Goligorsky MS, Permissive role of nitric oxide in endothelin-induced migration of endothelial cells, J Biol Chem 272 (1997) 1747–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Noiri E, Lee E, Testa J, Quigley J, Colflesh D, Keese CR, Giaever I, Goligorsky MS, Podokinesis in endothelial cell migration: role of nitric oxide, Am J Physiol 274 (1998) C236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kubes P, Suzuki M, Granger DN, Nitric oxide: an endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88 (1991) 4651–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Radomski MW, Palmer RM, Moncada S, Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium, Lancet 2 (1987) 1057–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Makhoul S, Walter E, Pagel O, Walter U, Sickmann A, Gambaryan S, Smolenski A, Zahedi RP, Jurk K, Effects of the NO/soluble guanylate cyclase/cGMP system on the functions of human platelets, Nitric Oxide 76 (2018) 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Seki J, Nishio M, Kato Y, Motoyama Y, Yoshida K, FK409, a new nitric-oxide donor, suppresses smooth muscle proliferation in the rat model of balloon angioplasty, Atherosclerosis 117 (1995) 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Boerrigter G, Lapp H, Burnett JC, Modulation of cGMP in heart failure: a new therapeutic paradigm, Handb Exp Pharmacol (2009) 485–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Childers KC, Garcin ED, Structure/function of the soluble guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain, Nitric Oxide 77 (2018) 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA, Structure and regulation of soluble guanylate cyclase, Annu Rev Biochem 81 (2012) 533–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xiao S, Li Q, Hu L, Yu Z, Yang J, Chang Q, Chen Z, Hu G, Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators and Activators: Where are We and Where to Go?, Mini Rev Med Chem 19 (2019) 1544–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Makrynitsa GI, Zompra AA, Argyriou AI, Spyroulias GA, Topouzis S, Therapeutic Targeting of the Soluble Guanylate Cyclase, Curr Med Chem 26 (2019) 2730–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Khalid RR, Maryam A, Fadouloglou VE, Siddiqi AR, Zhang Y, Cryo-EM density map fitting driven in-silico structure of human soluble guanylate cyclase (hsGC) reveals functional aspects of inter-domain cross talk upon NO binding, J Mol Graph Model 90 (2019) 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kang Y, Liu R, Wu JX, Chen L, Structural insights into the mechanism of human soluble guanylate cyclase, Nature 574 (2019) 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Horst BG, Yokom AL, Rosenberg DJ, Morris KL, Hammel M, Hurley JH, Marletta MA, Allosteric activation of the nitric oxide receptor soluble guanylate cyclase mapped by cryo-electron microscopy, Elife 8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Truesdale GA, Downing AL, Solubility of Oxygen in Water, Nature 173 (1954) 1236. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hall CN, Garthwaite J, What is the real physiological NO concentration in vivo?, Nitric Oxide 21 (2009) 92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tsai AL, Berka V, Martin E, Olson JS, A "sliding scale rule" for selectivity among NO, CO, and O(2) by heme protein sensors, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 172–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu G, Liu W, Berka V, Tsai AL, The selectivity of Vibrio cholerae H-NOX for gaseous ligands follows the "sliding scale rule" hypothesis. Ligand interactions with both ferrous and ferric Vc H-NOX, Biochemistry 52 (2013) 9432–9446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wu G, Liu W, Berka V, Tsai AL, H-NOX from Clostridium botulinum, like H-NOX from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, Binds Oxygen but with a Less Stable Oxyferrous Heme Intermediate, Biochemistry 54 (2015) 7098–7109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wu G, Liu W, Berka V, Tsai AL, Gaseous ligand selectivity of the H-NOX sensor protein from Shewanella oneidensis and comparison to those of other bacterial H-NOXs and soluble guanylyl cyclase, Biochimie 140 (2017) 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wu G, Zhao J, Franzen S, Tsai AL, Bindings of NO, CO, and O2 to multifunctional globin type dehaloperoxidase follow the 'sliding scale rule', Biochem J 474 (2017) 3485–3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dunford HB, Heme Peroxidases Wiley-VCH, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ortiz de Montellano PR, (Ed.), Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jain R, Chan MK, Mechanisms of ligand discrimination by heme proteins, J Biol Inorg Chem 8 (2003) 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Olson JS, Phillips GNJ, Myoglobin discriminates between O2, NO, and CO by electrostatic interactions with the bound ligand, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2 (1997) 544–552. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Oertling WA, Kean RT, Wever R and Babcock GT, Factors Affecting the Iron-Oxygen Vibrations of Ferrous Oxy and Ferryl Oxo Heme Proteins and Model Compounds, Inorg. Chem 29 (1990) 2633–2645. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ma X, Sayed N, Beuve A, van den Akker F, NO and CO differentially activate soluble guanylyl cyclase via a heme pivot-bend mechanism, Embo J 26 (2007) 578–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Erbil WK, Price MS, Wemmer DE, Marletta MA, A structural basis for H-NOX signaling in Shewanella oneidensis by trapping a histidine kinase inhibitory conformation, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (2009) 19753–19760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pellicena P, Karow DS, Boon EM, Marletta MA, Kuriyan J, Crystal structure of an oxygen-binding heme domain related to soluble guanylate cyclases, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 (2004) 12854–12859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Deinum G, Stone JR, Babcock GT, Marletta MA, Binding of nitric oxide and carbon monoxide to soluble guanylate cyclase as observed with Resonance raman spectroscopy, Biochemistry 35 (1996) 1540–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schelvis JP, Zhao Y, Marletta MA, Babcock GT, Resonance raman characterization of the heme domain of soluble guanylate cyclase, Biochemistry 37 (1998) 16289–16297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Makino R, Park SY, Obayashi E, Iizuka T, Hori H, Shiro Y, Oxygen binding and redox properties of the heme in soluble guanylate cyclase: implications for the mechanism of ligand discrimination, J Biol Chem 286 (2011) 15678–15687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fritz BG, Hu X, Brailey JL, Berry RE, Walker FA, Montfort WR, Oxidation and loss of heme in soluble guanylyl cyclase from Manduca sexta, Biochemistry 50 (2011) 5813–5815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Boon EM, Marletta MA, Ligand specificity of H-NOX domains: from sGC to bacterial NO sensors, J Inorg Biochem 99 (2005) 892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhao Y, Brandish PE, Ballou DP, Marletta MA, A molecular basis for nitric oxide sensing by soluble guanylate cyclase, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 (1999) 14753–14758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Boon EM, Marletta MA, Sensitive and selective detection of nitric oxide using an H-NOX domain, J Am Chem Soc 128 (2006) 10022–10023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Purohit R, Fritz BG, The J, Issaian A, Weichsel A, David CL, Campbell E, Hausrath AC, Rassouli-Taylor L, Garcin ED, Gage MJ, Montfort WR, YC-1 binding to the beta subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase overcomes allosteric inhibition by the alpha subunit, Biochemistry 53 (2014) 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Andrew CR, Green EL, Lawson DM, Eady RR, Resonance Raman studies of cytochrome c' support the binding of NO and CO to opposite sides of the heme: implications for ligand discrimination in heme-based sensors, Biochemistry 40 (2001) 4115–4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hough MA, Antonyuk SV, Barbieri S, Rustage N, McKay AL, Servid AE, Eady RR, Andrew CR, Hasnain SS, Distal-to-proximal NO conversion in hemoproteins: the role of the proximal pocket, J Mol Biol 405 (2011) 395–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Garton EM, Pixton DA, Petersen CA, Eady RR, Hasnain SS, Andrew CR, A Distal Pocket Leu Residue Inhibits the Binding of O(2) and NO at the Distal Heme Site of Cytochrome c', J Am Chem Soc (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kundu S, Hargrove MS, Distal heme pocket regulation of ligand binding and stability in soybean leghemoglobin, Proteins 50 (2003) 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kundu S, Snyder B, Das K, Chowdhury P, Park J, Petrich JW, Hargrove MS, The leghemoglobin proximal heme pocket directs oxygen dissociation and stabilizes bound heme, Proteins 46 (2002) 268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hargrove MS, Barry JK, Brucker EA, Berry MB, Phillips GN Jr., Olson JS, Arredondo-Peter R, Dean JM, Klucas RV, Sarath G, Characterization of recombinant soybean leghemoglobin a and apolar distal histidine mutants, J Mol Biol 266 (1997) 1032–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Quillin ML, Li T, Olson JS, Phillips GN Jr., Dou Y, Ikeda-Saito M, Regan R, Carlson M, Gibson QH, Li H, et al. , Structural and functional effects of apolar mutations of the distal valine in myoglobin, J Mol Biol 245 (1995) 416–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Draghi F, Miele AE, Travaglini-Allocatelli C, Vallone B, Brunori M, Gibson QH, Olson JS, Controlling ligand binding in myoglobin by mutagenesis, J Biol Chem 277 (2002) 7509–7519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Carver TE, Brantley RE Jr., Singleton EW, Arduini RM, Quillin ML, Phillips GN Jr., Olson JS, A novel site-directed mutant of myoglobin with an unusually high O2 affinity and low autooxidation rate, J Biol Chem 267 (1992) 14443–14450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Antonyuk SV, Rustage N, Petersen CA, Arnst JL, Heyes DJ, Sharma R, Berry NG, Scrutton NS, Eady RR, Andrew CR, Hasnain SS, Carbon monoxide poisoning is prevented by the energy costs of conformational changes in gas-binding haemproteins, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 (2011) 15780–15785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Weinert EE, Phillips-Piro CM, Tran R, Mathies RA, Marletta MA, Controlling Conformational Flexibility of an O(2)-Binding H-NOX Domain, Biochemistry (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Weinert EE, Plate L, Whited CA, Olea C Jr., Marletta MA, Determinants of ligand affinity and heme reactivity in H-NOX domains, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 49 (2010) 720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Plate L, Marletta MA, Nitric oxide-sensing H-NOX proteins govern bacterial communal behavior, Trends Biochem Sci 38 (2013) 566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Springer BA, Sligar SG, Olson JS, Phillips GN Jr., Mechanisms of Ligand Recognition in Myoglobin, Chem. Rev 94 (1994) 699–714. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Boon EM, Huang SH, Marletta MA, A molecular basis for NO selectivity in soluble guanylate cyclase, Nat Chem Biol 1 (2005) 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Boon EM, Marletta MA, Ligand discrimination in soluble guanylate cyclase and the H-NOX family of heme sensor proteins, Curr Opin Chem Biol 9 (2005) 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Martin E, Berka V, Bogatenkova E, Murad F, Tsai AL, Ligand selectivity of soluble guanylyl cyclase: effect of the hydrogen-bonding tyrosine in the distal heme pocket on binding of oxygen, nitric oxide, and carbon monoxide, J Biol Chem 281 (2006) 27836–27845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Martin E, Berka V, Sharina I, Tsai AL, Mechanism of binding of NO to soluble guanylyl cyclase: implication for the second NO binding to the heme proximal site, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 2737–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Herzik MA Jr., Jonnalagadda R, Kuriyan J, Marletta MA, Structural insights into the role of iron-histidine bond cleavage in nitric oxide-induced activation of H-NOX gas sensor proteins, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 (2014) E4156–4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Tsai AL, Berka V, Sharina I, Martin E, Dynamic ligand exchange in soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC): implications for sGC regulation and desensitization, J Biol Chem 286 (2011) 43182–43192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Yoo BK, Lamarre I, Martin JL, Rappaport F, Negrerie M, Motion of proximal histidine and structural allosteric transition in soluble guanylate cyclase, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112 (2015) E1697–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Guo Y, Suess DLM, Herzik MA Jr., Iavarone AT, Britt RD, Marletta MA, Regulation of nitric oxide signaling by formation of a distal receptor-ligand complex, Nat Chem Biol 13 (2017) 1216–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Fernhoff NB, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA, A nitric oxide/cysteine interaction mediates the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (2009) 21602–21607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Russwurm M, Koesling D, NO activation of guanylyl cyclase, Embo J 23 (2004) 4443–4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA, Butyl isocyanide as a probe of the activation mechanism of soluble guanylate cyclase. Investigating the role of non-heme nitric oxide, J Biol Chem 282 (2007) 35741–35748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Horst BG, Marletta MA, Physiological activation and deactivation of soluble guanylate cyclase, Nitric Oxide 77 (2018) 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Friebe A, Koesling D, Mechanism of YC-1-induced activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase, Mol Pharmacol 53 (1998) 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Friebe A, Mullershausen F, Smolenski A, Walter U, Schultz G, Koesling D, YC-1 potentiates nitric oxide- and carbon monoxide-induced cyclic GMP effects in human platelets, Mol Pharmacol 54 (1998) 962–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Friebe A, Schultz G, Koesling D, Sensitizing soluble guanylyl cyclase to become a highly CO-sensitive enzyme, Embo J 15 (1996) 6863–6868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Becker EM, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, Gerzer R, Minuth T, Pleiss U, Schmidt P, Schramm M, Schroder H, Schroeder W, Steinke W, Straub A, Stasch JP, NO-independent regulatory site of direct sGC stimulators like YC-1 and BAY 41-2272, BMC Pharmacol 1 (2001) 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Chester M, Tourneux P, Seedorf G, Grover TR, Gien J, Abman SH, Cinaciguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase activator, causes potent and sustained pulmonary vasodilation in the ovine fetus, Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297 (2009) L318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zhou Z, Pyriochou A, Kotanidou A, Dalkas G, van Eickels M, Spyroulias G, Roussos C, Papapetropoulos A, Soluble guanylyl cyclase activation by HMR-1766 (ataciguat) in cells exposed to oxidative stress, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295 (2008) H1763–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Pankey EA, Bhartiya M, Badejo AM Jr., Haider U, Stasch JP, Murthy SN, Nossaman BD, Kadowitz PJ, Pulmonary and systemic vasodilator responses to the soluble guanylyl cyclase activator, BAY 60-2770, are not dependent on endogenous nitric oxide or reduced heme, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300 (2011) H792–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Scuseria GE, Mille MD, Jensen F, Geertsen J, The dipole moment of carbon monoxide, J. Chem. Phys 94 (1991) 6660–6663. [Google Scholar]

- [82].Smyth CP, McAlpine KB, The Dipole Moment of Nitric Oxide, J. Chem. Phys 1 (1933) 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- [83].Winter MB, Herzik MA Jr., Kuriyan J, Marletta MA, Tunnels modulate ligand flux in a heme nitric oxide/oxygen binding (H-NOX) domain, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 (2011) E881–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Franzen S, Spin-dependent mechanism for diatomic ligand binding to heme, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 (2002) 16754–16759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Salter MD, Nienhaus K, Nienhaus GU, Dewilde S, Moens L, Pesce A, Nardini M, Bolognesi M, Olson JS, The apolar channel in Cerebratulus lacteus hemoglobin is the route for O2 entry and exit, J Biol Chem 283 (2008) 35689–35702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Rozza AM, Menyhard DK, Olah J, Gas Sensing by Bacterial H-NOX Proteins: An MD Study, Molecules 25 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Olea C, Boon EM, Pellicena P, Kuriyan J, Marletta MA, Probing the function of heme distortion in the H-NOX family, ACS Chem Biol 3 (2008) 703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Tran R, Boon EM, Marletta MA, Mathies RA, Resonance Raman spectra of an O2-binding H-NOX domain reveal heme relaxation upon mutation, Biochemistry 48 (2009) 8568–8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Tran R, Weinert EE, Boon EM, Mathies RA, Marletta MA, Determinants of the Heme-CO Vibrational Modes in the H-NOX Family, Biochemistry 50 (2011) 6519–6530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.