Abstract

Ocular surface diseases including conjunctival disorders are multifactorial progressive conditions that can severely affect vision and quality of life. In recent years, stem cell therapies based on conjunctival stem cells (CjSCs) have become a potential solution for treating ocular surface diseases. However, neither an efficient culture of CjSCs nor the development of a minimally invasive ocular surface CjSC transplantation therapy has been reported. Here, we developed a robust in vitro expansion method for primary rabbit-derived CjSCs and applied digital light processing (DLP)-based bioprinting to produce CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs for injectable delivery. Expansion medium containing small molecule cocktail generated fast dividing and highly homogenous CjSCs for more than 10 passages in feeder-free culture. Bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs with tunable mechanical properties enabled the 3D culture of CjSCs while supporting viability, stem cell phenotype, and differentiation potential into conjunctival goblet cells. These hydrogel micro-constructs were well-suited for scalable dynamic suspension culture of CjSCs and were successfully delivered to the bulbar conjunctival epithelium via minimally invasive subconjunctival injection. This work integrates novel cell culture strategies with bioprinting to develop a clinically relevant injectable-delivery approach for CjSCs towards the stem cell therapies for the treatment of ocular surface diseases.

Keywords: Bioprinting, Conjunctival stem cells, 3D culture, Injectable delivery, Stem cell therapy, Ocular surface regeneration

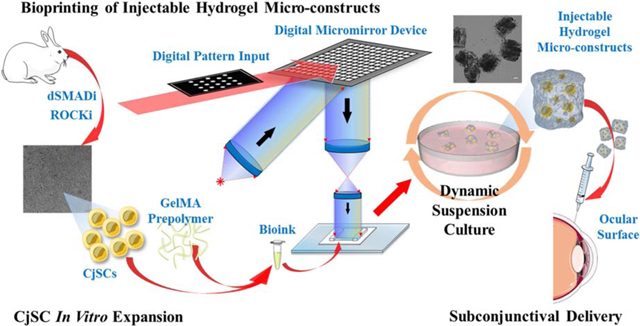

Graphical Abstract

We present an integrated system that efficiently expanded CjSCs in vitro and utilized rapid bioprinting to fabricate hydrogel micro-constructs encapsulating CjSCs for subconjunctival injectable delivery to an ocular surface.

1. Introduction

The conjunctiva is a nonkeratinized stratified epithelium that comprises the ocular surface along with the cornea[1]. It is a transparent mucous membrane that contains mucin-producing goblet cells, which are important for tear film stability[2]. Disorders of the conjunctiva include ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, pterygium, and chemical or physical damages, which can lead to further complications such as dysfunctional tear syndrome, keratinization, symblepharon formation, and increased risk of infection[1,3–5]. With more than ten million new diagnosis worldwide each year, patients suffering from these severe forms of ocular diseases will often need surgical intervention to regenerate the ocular surface, especially the conjunctiva, to restore vision[6–10]. As the damage to the ocular surface is one of the major causes of visual impairment, preserving the integrity of the conjunctiva is critical[11]. Traditional therapeutics for treating severe ocular surface diseases include an autograft of conjunctiva or nasal mucosa, an allograft of amniotic membrane (AM), and conservative medications with eye drops[12–16]. However, these approaches have limitations in complete regeneration and the sourcing of autogenic or allogenic tissue is scarce. A critical factor in their lack of effectiveness is due to persistent inflammation which can drain the endogenous stem cell reservoir and hamper the regenerative capacity of the conjunctiva[17][18]. With the development of advanced regenerative medicine and stem cell technologies, growing attention over the past decade has turned towards the utilization of stem cell therapy for ocular surface diseases[19,20].

In parallel to the identification of corneal stem cells originating from the limbus as a promising source to support stem cell therapy for corneal diseases, there is currently a large interest in exploring the use of conjunctival stem cells (CjSCs) and their clinical applications for ocular surface diseases[21–24]. CjSCs are bipotent progenitor cells of conjunctival keratinocytes and conjunctival goblet cells[23,25]. Although several studies have located and identified CjSCs populations within the conjunctival epithelium, their efficient in vitro expansion and subsequent transplantation to the ocular surface remains a challenge[21,26]. Recent studies on epithelial stem cells have highlighted the effectiveness of small molecule based dual SMAD signaling inhibition (dSMADi) and ROCK signaling inhibition (ROCKi) for the extensive expansion of epithelial stem cells derived from the airway, esophagus, intestine, skin, mammary, epididymis, and prostate glands[27,28]. Dual SMAD signaling, encompassing the TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways, influences the epithelial basal stem cell fate by controlling their differentiation, dedifferentiation, self-renewal, and quiescence[29–32]. ROCK signaling pathways play critical roles in the regulation of the cytoskeleton, microtubule dynamics, cell membrane transportation, and polarity[33]. Therefore, integration of dSMADi with ROCKi can potentially be used towards the development of feeder-free cell culture systems for CjSCs.

As the cell-niche interactions significantly affect stem cell survival and behavior, an instructive niche is critically important for successful stem cell transplantation[18,34,35]. Present studies on conjunctival reconstruction have mostly focused on allogeneic sheet transplantation using primary conjunctival epithelium grown on AM or other substitutes[26,36–38]. However, very few studies have addressed the use of substrates supporting the transplantation of CjSCs, which is mainly due to the poor understanding of their native niche. Meanwhile, the existing methodologies largely employ surgical grafting that often involve high postoperative risks including scar formation and symblepharon, as well as elongate recovery times. Therefore, minimally invasive cell transplantation strategies have become a safe and effective alternative[39–43]. Nevertheless, the delivery of CjSCs to the conjunctiva is limited by challenges regarding poor immobilization of cells to the target site which can lead to compromised viability and rapid diffustion of the transplanted cells[44]. In recent years, encouraging progress has been made in integrating hydrogel scaffolds for therapeutic delivery of stem cells to the ocular surface[45,46]. Digital light processing (DLP)-based rapid bioprinting enables a robust platform for high throughput fabrication of cell-loaded hydrogel constructs while providing well-defined user control over key factors including cell placement, biomechanical properties, and microarchitecture to better recapitulate the native niche[47–52]. Moreover, bioprinting offers superior microscale geometric control as well as the scalable and rapid production of cellularized constructs[53,54]. Given the elastic nature of the conjunctival epithelium, subconjunctival delivery of injectable bioprinted cell-loaded hydrogel constructs could be used as a minimally invasive remedy for ocular surface regeneration[55].

In this study, we presented a DLP-based rapid bioprinting approach to fabricate microscale CjSC-loaded hydrogel constructs for subconjunctival injectable delivery. We first expanded rabbit-derived CjSCs using a feeder-free culture system containing a small molecule cocktail that performed dSMADi and ROCKi. Then, we applied our DLP-based bioprinting system to fabricate hydrogel micro-constructs with tunable mechanical properties to encapsulate CjSCs while ensuring their viability and preserving stem cell behavior. Dynamic suspension culture of the hydrogel micro-constructs was also performed to demonstrate the scalability of the process. Furthermore, we validated the injectability and post-injection viability of CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs by performing ex vivo delivery into the subconjunctival region of rabbit eyes using a 30-gauge syringe. This is the first report on the development of bioprinted injectable CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs and the establishment of protocols for robust in vitro expansion of CjSCs. Overall, this work serves as an important framework for understanding the conjunctival stem cell population, conjunctival epithelial biology, as well as the application of CjSCs as a clinically translatable strategy for minimally invasive treatments of severe ocular surface diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primary CjSCs isolation, culture, and differentiation

Fresh eyes harvested from 10–12 weeks old New Zealand White rabbits (Oryctolagus Cuniculus) were acquired from Sierra for Medical Science, Inc. (Whittier, CA) and used for conjunctival cell isolation. Rabbit conjunctival epithelium was collected from palpebral conjunctiva and bulbar conjunctiva that was 3–5 mm away from the limbus. PBS was subconjunctivally injected into the palpebral and bulbar area with a flat pinhead for the blunt dissection of conjunctival epithelium from the stroma. The dissected conjunctival epithelium was minced with a surgical blade and incubated with 0.5% type IV collagenase (Sigma Aldrich) solution at 37° under agitation at 150 rpm for 1 hour. After the incubation, cell pellets were collected and washed with PBS, followed by a 10 minutes digestion with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Sigma Aldrich). The cells were filtered using a 75 μm cell strainer before seeding onto collagen I (ThermoFisher Scientific) coated 6-well plates. The epithelial basal medium was prepared as previously reported by combining DMEM/F-12 (3:1) with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (DF12) supplemented with 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin (P-S, ThermoFisher Scientific), 1x insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS, ThermoFisher Scientific), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF, R&D System), 400 ng/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma Aldrich), 0.1 nM cholera toxin (Sigma Aldrich), and 2 nM 3,39,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (Sigma Aldrich)[24,56]. In the medium component formulation studies, 0.1 μM, 1 μM, or 10 μM A83-01 (STEMCELL Technologies), SB431542 (Tocris Bioscience), DMH1 (STEMCELL Technologies), Dorsomorphin (STEMCELL Technologies), LDN193189 (Tocris Bioscience), or 10 μM SB505142 (Tocris Bioscience), 1 μM LY294002 (Tocris Bioscience), 10 μM Y27632 (Tocris Bioscience), 100 ng/ml bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) (Biolegend), 100 ng/ml transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ; Biolegend) were added into the basal medium. Basal medium without these aformentioned additive components was used as the control in the primary culture study. The procedure was approved by University of California San Diego Institutional Biosafety Committee.

For the expansion of CjSCs, cells were seeded on collagen I (ThermoFisher Scientific) coated 6-well plates with the seeding density of 200,000 cells per well and cultured in conjunctival stem cell expansion medium (CjSCM) composed of epithelial basal medium supplemented with 10 μM Y27632, 1 μM A83-01, and 1 μM DMH1. Medium changes were performed every other day and cells were passaged at 80–90% confluence. For differentiation into conjunctival goblet cells, expanded CjSCs over passage 2 (P2) were seeded and cultured the same as mentioned above. The differentiation was initiated when the cells reached 90% confluence, in differentiation medium composed of Keratinocyte SFM (serum-free medium) (ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 50 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract (BPE), 5 ng/ml recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) (ThermoFisher Scientific), 1% (v/v) P-S, 100 ng/ml BMP4, 10 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10), 100 ng/ml interleukin 13 (IL-13) and 1 μM A83-01[2,57–59]. The cells were cultured with the goblet cell differentiation medium for 7 days with the medium changed every other day. For CjSCs 3D static culture, the bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs were cultured in a 24-well plate with CjSCM immediately after bioprinting to induce goblet cell differentiation as described above. For dynamic suspension culture, the hydrogel micro-constructs were cultured in 12-well plates and constantly agitated at a rate of 95 rpm. The cell culture was performed at 37°C with 5% CO2.

2.2. Material synthesis and photocrosslinkable bioink preparation

Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) was synthesized according to previously established protocols[60,61]. Briefly, porcine skin gelatin type A (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved into a 0.25 M carbonate-bicarbonate (3:7) buffer solution at pH 9 with stirring at 50°C to prepare a 10% (w/v) solution. Once the gelatin was completely dissolved, methacrylic anhydride (MA; Sigma Aldrich) was added dropwise into the gelatin solution to a concentration of 100μl per gram of gelatin and reacted for 1 hour under continuous stirring at 50°C. The product underwent dynamic dialysis overnight using 13.5 kDa dialysis tubes (Repligen). The GelMA solution was then lyophilized for three days and stored at −80°C for later use. Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) was used as a photoinitiator and synthesized as previously described[62]. In brief, under constant stirring at room temperature, 18 mmol of dimethyl phenylphosphonite (Sigma Aldrich) was mixed equimolarly with 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride (Acros Organics) by dropwise addition and left to react for 18 hours. Next, 6.1 g of lithium bromide (Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in 100 ml of 2-butanone (Sigma Aldrich) was added in the reaction mixture, and the reaction was continued at 50°C for 10 minutes with stirring. The mixture was then left to incubate overnight at room temperature and the unreacted lithium bromide was removed by filter-washing with 2-butanone for a total of 3 times. The resultant LAP solids were ground into powder and stored in the dark under argon at 4°C.

To prepare the prepolymer bioinks, GelMA powders and LAP powders were dissolved with warmed DPBS to form a stock solution of 10% (w/v) GelMA and 0.5% (w/v) LAP, followed by filtering with 0.22 μm syringe filters. The cells were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and neutralized with culture medium. The resultant cell solution was filtered with a 75 μm cell strainer to attain a single cell suspension. The cell suspension was then counted with a hemocytometer and adjusted to desired concentrations. Immediately prior to bioprinting, the GelMA-LAP prepolymer solution was mixed 1:1 with single cell suspension to form a final bioink formulation composed of 5% (w/v) GelMA, 0.25% (w/v) LAP, and 107 cells/mL CjSCs. For the acellular bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs, the prepolymer solution was mixed 1:1 with DPBS to make the bioink.

2.3. Rapid bioprinting of hydrogel micro-constructs

Rapid bioprinting of acellular or cellularized hydrogel micro-constructs was performed with our custom-built digital light projection (DLP)-based bioprinting system[50,51,63]. This DLP-based bioprinter consists of a 365 nm light source (Hamamatsu) with aligning projection optics, a digital micromirror device (DMD) chip (Texas Instruments) for optical patterning, and a stage controlled by a motion controller (Newport). User-defined patterns were fed into the computer. Using custom operation software the DMD chip could be controlled to modulate the light projection based on the assigned patterns. All the digital patterns used for bioprinting were generated with Adobe Photoshop. For the bioprinting setup, two identical polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) spacers with the thicknesses of 500 μm or 125 μm were placed between a methacrylated coverslip and the PDMS base attached to a glass slide. The prepolymer bioink was loaded into the gap between the coverslip and the base followed by photopolymerization. The polymerized constructs were immediately transferred to a 24-well plate containing pre-warmed DPBS and excess prepolymer was washed by gentle pipetting. The DPBS was then replaced by the culture medium which was then changed after the first 24 hours. For dynamic suspension culture, the hydrogele constructs were rinsed with DPBS and then carefully detached from the coverslips using surgical blades and placed into 12-well plates (36 constructs per well). The hyrdogel constructs were resuspended with warm CjSCM and subjected to 95 rpm rotation.

2.4. Immunofluorescence staining

For 2D cell staining, CjSCs were grown on collagen-coated Millicell EZ slides (Millipore Sigma). Samples were washed twice with sterile DPBS and fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako) for 20 minutes at room temperature, followed by three 10 minutes DPBS washes. For the co-staining of ABCG2/KRT14, P63/E-Cad, and KI67/PAX6 the fixed samples were blocked with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albuminutes (BSA; Sigma Aldrich) containing 0.3% triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 hour at room temperature. For the staining of Muc5AC and MUC16, the fixed samples were permeabilized with DPBS containing 0.2% triton X-100 for 10 min, followed by blocking for 1 hour with 5% (w/v) BSA. Afterwards, samples were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Following primary antibody incubation, cultures were washed three times for 10 minutes each in DPBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature. The samples were then washed with DPBS three times before staining with DAPI (4’,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole; ThermoFisher Scientific) diluted in DPBS (1:500) for 10 minutes. After removing the DAPI solution and a final DPBS wash, the solution was aspirated and the samples were air-dried for 30 seconds, followed by mounting with Fluoromount-G™ Mounting Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). The immunofluorescence staining on hydrogel micro-constructs followed the same protocols with the mounting step omitted. For the staining on cryosectioned samples, the optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.) compound was washed off with three 10 minutes DPBS washes followed by brief air drying. Then, hydrophobic circles were drawn around the sections with a PAP pen (Sigma Aldrich). The permeabilization and blocking were performed with 5% (w/v) BSA and 0.3% (v/v) triton X-100 at room temperature for 1 hour. The sequential steps are the same as described above. After staining, samples were imaged within 48 hours. The antibody information and their dilution rates are available in the Supplementary Table 1.

2.5. Mechanical properties characterization

The compressive modulus (Young’s modulus) of the bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs encapsulted with CjSCs was measured using a MicroSquisher (CellScale) apparatus following the manufacturer’s instructions. The 5% GelMA cylinders (250 μm in diameter; 250 μm in height) printed for the test were incubated at 37°C before use. Prior to measurement, the hysteresis of the samples was removed with two rounds of preconditioned compression. Then, the samples were compressed at 10% strain with a 2 μm/s strain rate to record the data. The Young’s modulus of measured samples was calculated using a custom MATLAB algorithm with the force and displacement data.

Rheometry was used to determine if the hydrogels are shear thinning. We adapted an established testing protocol[64] and conducted the measurements on a parallel plate rheometer (AR-G2 Rheometer, TA Instruments). The tests were conducted at 25°C and a gap height of 1000 μm. The tests were conducted at room temperature to mimic the ambient temperature for injection. A 5% GelMA, 0.25% LAP solution in DPBS was warmed to 37°C and 310 μl of solution was injected between the plates. The top plate was lowered to 900 μm and lifted back to 1000 μm to ensure even the spreading of solution between the plates. To form the hydrogel between the parallel plates, the solution was exposed for 5 minutes to UV light from a 395nm UV LED flashlight (TaoTronics, Model: TT-FL001). Before each test, a 2 minutes time sweep was performed at 0.2% strain and 10 Hz to recondition the hydrogel to reset its mechanical history. A frequency sweep was done from 0.01 to 100 Hz at 0.2% strain with 10 points per decade. A strain sweep was done from 0.01% to 500% strain at 10 Hz with 10 points per decade. The viscosity was measured by a continuous flow ramp from shear rates 0 to 50 s−1 in 2.5 minutes with 20 points per decade. The reported data represents 3 independent hydrogel runs.

For the characterization of equilibrium swelling ratio, acellular hydrogel micro-constructs were fabricated as described above. The hydrogel micro-constructs were dehydrated with overnight incubation at 37°C, followed by imaging and rehydration via DPBS immersion. The hydrated hydrogel micro-constructs were then imaged every 24 hours for 6 days with a Leica DMI 6000-B microscope. The cross-sectional area of the dry and wet hydrogel micro-constructs were measured using ImageJ and recorded as ADry and AWet, respectively. The equilibrium swelling ratio at each time point was calculated by AWet/ADry. All measurements were performed in triplicates.

2.6. Viability evaluation

To evaluate the viability of encapsulated CjSCs in the bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs, samples were stained with Live/Dead™ Viability/Cytotoxicity kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the metabolic activity was measured with CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay (Promega). For the Live/Dead staining, the hydrogel micro-constructs were incubated with DPBS with 2 μM calcein acetoxymethyl ester and 4 μM ethidium homodimer for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by fluorescent imaging with Leica DMI 6000-B microscope. The Live/Dead™ staining was performed in duplicates. For the CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay, the hydrogel micro-constructs were transferred to a 24-well plate filled with 200 μl culture medium and 200 μl CellTiter-Glo® 3D reagent (400 μl solution per well). The samples were then incubated at room temperature under constant agitation for 1 hour. After incubation, 50 μl of the lysate was transferred to a white opaque-walled 96-well plate and diluted with 150 μl of UltraPure™ water (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The adenosine triphosphate (ATP) standard curve was created with gradient dilution of ATP disodium salt (Promega) and loaded in the same 96-well plate. Each test was performed with 6 replicates. The data collection was carried out by plate-reading with the Tecan Infinite M200 PRO microplate reader.

2.7. RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and real time quantitative PCR

To extract the RNA from the 2D cultured cells, chilled TRIzol® reagent (Ambion Thermo Fisher) was added to the pelleted cells followed by repeated pipetting. To extract the RNA from encapsulated cells in hydrogel micro-constructs, the samples were physically broken down with clean pipette tips and immediately immersed into chilled TRIzol® reagent and repeatedly pipetted. The lysate was either used for extraction or immediately stored in the −80°C freezer. RNA samples were extracted with the Direct-zol™ RNA Purification kit (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The products were quantified using a NanoDrop™ 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) instrument. The RNA samples were either used immediately for cDNA synthesis or stored at −80°C. The cDNA reverse transcription synthesis was carried out with PhotoScript® first strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England BioLabs) following the manufacturer’s protocols using the thermal cycler of the StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The resultant cDNAs were further diluted 10-fold with UltraPure™ water (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed in triplicates using the Luna® Universal qPCR Master Mix (New England BioLabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The qPCR primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2. For relative quantification, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control.

2.8. Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry, cultured cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, filtered with a 75 μm cell strainer, and pelleted by centrifugation. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the pellets were resuspended with a Cell Staining Buffer (Biolegend) and TruStain FcX™ (Biolegend) was used for blocking. To quantify the KRT14 positive population, anti-Keratin 14 rabbit polyclonal antibody (905304, Biolegend) and anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), F(ab’)2 Fragment (Cell Signaling Tech) were applied subsequentially following the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry was performed using FACSAria™ Fusion sorter (BD Biosciences) and the data was analyzed using FlowJo.

2.9. Cell doubling quantification

For the cell doubling comparison, freshly isolated, viable conjunctival epithelial cells were seeded on a collagen I coated 12-well plate with a density of 20,000 cells per well. The cells were serially expanded in CjSCM or control medium. Subculture was performed with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA every 3–4 days depending on the confluence. The number of cells were measured with hemocytometer (Fisher Scientific) and re-seeded on a collagen I coated 12-well plate with a density of 20,000 cells per well. The test was performed in triplicates and the cell doubling time (DT) was calculated with the following formula: DT = ΔT ·ln 2 /ln (Q2/Q1). ΔT represents the incubation time. Q1 and Q2 represents the number of cells at the beginning and at the end, respectively.

2.10. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining

PAS staining on differentiated conjunctival goblet cells was performed by Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) Stain Kit (Abcam) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Imaging was performed using the Keyence BZ-9000 microscope with a multicolor CCD camera.

2.11. Biodegradibility test

To evaluate the biodegradibility of the hydrogel materials, we synthesized fluorescein (FAM) conjugated GelMA using FAM NHS ester, 6-isomer (Lumiprobe, CAT# 55120) with guidance from the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, lyophilized GelMA and FAM NHS ester were first homogeneously dissolved separately in 0.1M sodium bicarbonate buffer solution (pH 8.3) then combined into a 50-ml conical to make a 2% (w/v) GelMA solution with 4x molar excess of FAM NHS ester. The reaction was allowed to proceed overnight at 4°C in the dark. The solution was filtered via Zeba™ 7K MWCO spin desalting columns (ThermoFisher, CAT# 89894) to remove excess FAM NHS ester, subsequently frozen at −20°C, and lyophilized for three days. Lyophilized FAM-GelMA was stored at −80°C until further use.

The FAM-GelMA pre-polymer solution was prepared and used for bioprinting as described in Section 2.2. For the biodegradibility test, FAM-GelMA-based microscale cylinders (2 mm in diameter; 500 μm in height) were printed. The hydrogel constructs were then subjected to 100 rpm rotating incubation at 37°C with 10 μg/ml collagenase Type IV (Sigma Aldrich). The supernatant was collected every 10 minutes until the complete degradation of hydrogel constructs. The FAM concentrations in the supernatant were measured by fluorescence plate-reading with the Tecan Infinite M200 PRO microplate reader. The degree of degradation was calculated by normalizing the signal from each groups to the signal from the complete degradation group (80 minutes group).

2.12. Injectability test

To evaluate the injectability of the hydrogel micro-constructs, 80 samples were suspended in 200 μl of DPBS in a microcentrifuge tube and aspirated with a 30-gauge syringe needle, followed by repeated injection and aspiration for a total of 3 times. Afterwards, the treated hydrogel micro-constructs and the non-treated controls were subjected to dynamic suspension culture. Live/Dead™ staining was performed to evaluate the influence of injection on the encapsulated cells.

2.13. Subconjunctival delivery and cryosection

Subconjunctival injection into rabbit eyes was performed using a 30-gauge syringe needle. For a single injection, 36 hydrogel micro-constructs encapsulated with GFP-labeled CjSCs were suspended in 100 μl of DPBS supplemented with 1% (v/v) P-S in a microcentrifuge tube, loaded into the syringe, and injected into the subconjunctival regions of the bulbar conjunctiva. Four injection sites in between the muscles and connective tissues were chosen to mimic the actual injection protocol. Morover, 100 μl of single cell suspension (106 cells/ml) in DPBS with 1% (v/v) P-S was injected in the same manner to serve as the control. After injection, the rabbit eyes were incubated in DF12 supplemented with 10 ng/ml EGF and 1% (v/v) P-S, for 24 hours under constant agitation at 95 rpm.

To prepare the rabbit eyeballs for cryosectioning, dissection was performed with the anterior part (sclera ring with conjunctiva and cornea) kept intact and the excised tissue was fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA for 3 hours, followed by dehydration with 30% (w/v) sucrose (Sigma Aldrich) in 0.1 M DPBS at 4 °C overnight. The tissues were then embedded in Tissue Tek® O.C.T. Compound (Fisher Scientific) and frozen at −80°C. Serial transverse sections of 6 μm thick each were cut using a CM1900 cryostat (Leica) and stored at −80 °C until stained.

2.14. Imaging and processing

The brightfield and regular fluorescence images of the cells and hydrogel micro-constructs were captured using a Leica DMI 6000-B microscope. Confocal imaging was performed using a Leica SP8 Confocal with lighting deconvolution. All images were processed using LAS X software and ImageJ.

2.15. Statistical analysis

All the statistics in this work were processed with Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism (V6) and presented by mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance was evaluated with Student’s t-test (two tailed) or one-way ANOVA. Statistics with P-value < 0.05 were considered as significant and labeled with asterisks (*: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001.).

3. Results

3.1. In vitro expansion of CjSCs with small molecule cocktail

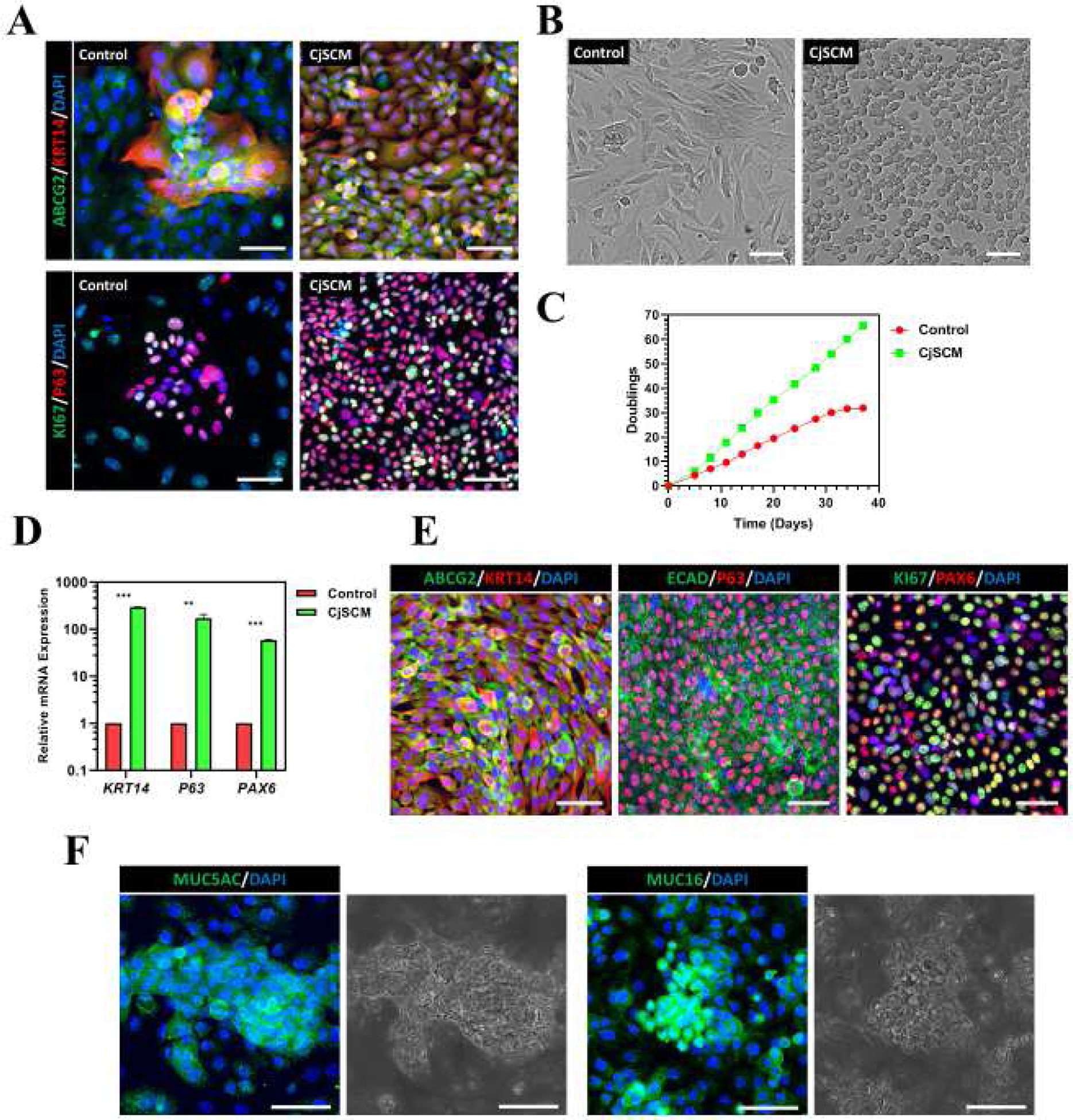

To expand the CjSCs in vitro, different small molecules related to dSMADi or ROCKi at different concentrations (i.e. 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM) in the basal medium were tested. The mitotically active undifferentiated epithelial cell population represented by cytokeratin 14 (KRT14) positive cells were evaluated by flow cytometry (Supplementary S1A, B)[65,66]. Groups treated with A83-01 (TGFβ inhibitor) and DMH1 (BMP inhibitor) showed the most KRT14 positive population expansion among their analogues. Given the promise of the addition of A83-01 and DMH1, we further tested them along with Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor) and the related activator proteins (TGFβ, BMP4) to evaluate their efficacy in stem cell expansion. After 4 days of primary culture, more small-sized and tightly packed cells were found in the inhibitors (i.e. A83-01, DMH1, Y27632)-treated groups (Supplementary S1C). Real time qPCR showed up-regulated mRNA expression of stem cell markers (KRT14, P63) and ocular lineage marker (PAX6) in the inhibitors-treated groups while down-regulated expression was found in the activators (i.e. TGFβ, BMP4)-treated groups (Supplementary S1D)[23,67]. The three inhibitors combined group exhibited the highest expression up-regulation on all three markers, which indicated the three components synergistically stimulated stem cell expansion in primary conjunctival epithelial cell culture. Consistently, immunofluorescence staining of stem cell markers (ABCG2, KRT14, P63) and the proliferation marker (KI67) identified homogenous positive populations in the three inhibitors combined group while only small colonies of positive populations were found in the control (Fig. 1A)[23]. Based on these results, we combined 10 μM Y27632, 1 μM A83-01, and 1 μM DMH1 to form the small molecule cocktail for the conjunctival stem cell expansion medium (CjSCM). The cells cultured with CjSCM were homogenous in size and rounded shape whereas the control cells showed heterogenous size and flattened, elongated morphologies (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, long-term culture demonstrated that cells expanded with CjSCM proliferated significantly faster than the control cells and can be expanded stably for more than 60 doublings without losing replicative potential (Fig. 1C, Supplementary S1E). Real time qPCR showed an up-regulation in expression of KRT14, P63 and PAX6, in the expanded CjSCs in comparison to the control (Fig. 1D). The stem cell identity and proliferative potential of the CjSCs cultured with CjSCM were confirmed by the positive expression of the stem cell markers (i.e. ABCG2, KRT14, P63), lineage markers (i.e. E-Cadherin (ECAD), PAX6) and proliferation marker (i.e. KI67) (Fig. 1E). We next tested whether the expanded CjSCs are functional by differentiating them into conjunctival goblet cells. Immunofluorescence staining showed the positive expression of the characteristic mucous protein markers for mucin 5AC (MUC5AC) and mucin 16 (MUC16) in the CjSCs expanded with CjSCM after 7 days of goblet cell differentiation (Fig. 1F)[2,68]. This was further confirmed by positive Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining for mucin expression in the cells post differentiation (Supplementary S1F). Together, we showed successful in vitro expansion of functional CjSCs while preserving differentiation potential into conjunctival goblet cells using our developed CjSCM.

Figure 1. Conjunctival Stem Cell Expansion Medium (CjSCM) with Small Molecule Cocktail Facilitates in vitro Expansion of CjSCs.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of ABCG2/ KRT14 and KI67/P63 on primary conjunctival epithelial cells that were cultured in CjSCM or control medium for 4 days. Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) Cell morphologies of nonconfluent primary conjunctival epithelial cells cultured with CjSCM or control medium at P3. Scale bars: 50 μm. (C) Cumulative cell doubling plot showing the doublings versus the culture time of primary conjunctival epithelial cells in culture with CjSCM or control medium. (D) Real time qPCR showing the relative mRNA expression of stem cell markers (i.e. KRT14, P63) and lineage marker (i.e. PAX6) in P10 cells expanded in CjSCM or control medium (mean ± sd, n=3, **: P < 0.01.). (E) Immunofluorescence staining of ABCG2/ KRT14, ECAD/ P63 and KI67/PAX6 on CjSCs at P10. Scale bars: 50 μm. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of MUC5AC and MUC16 and the corresponding bright field images on the differentiated CjSCs. Scale bars: 50 μm.

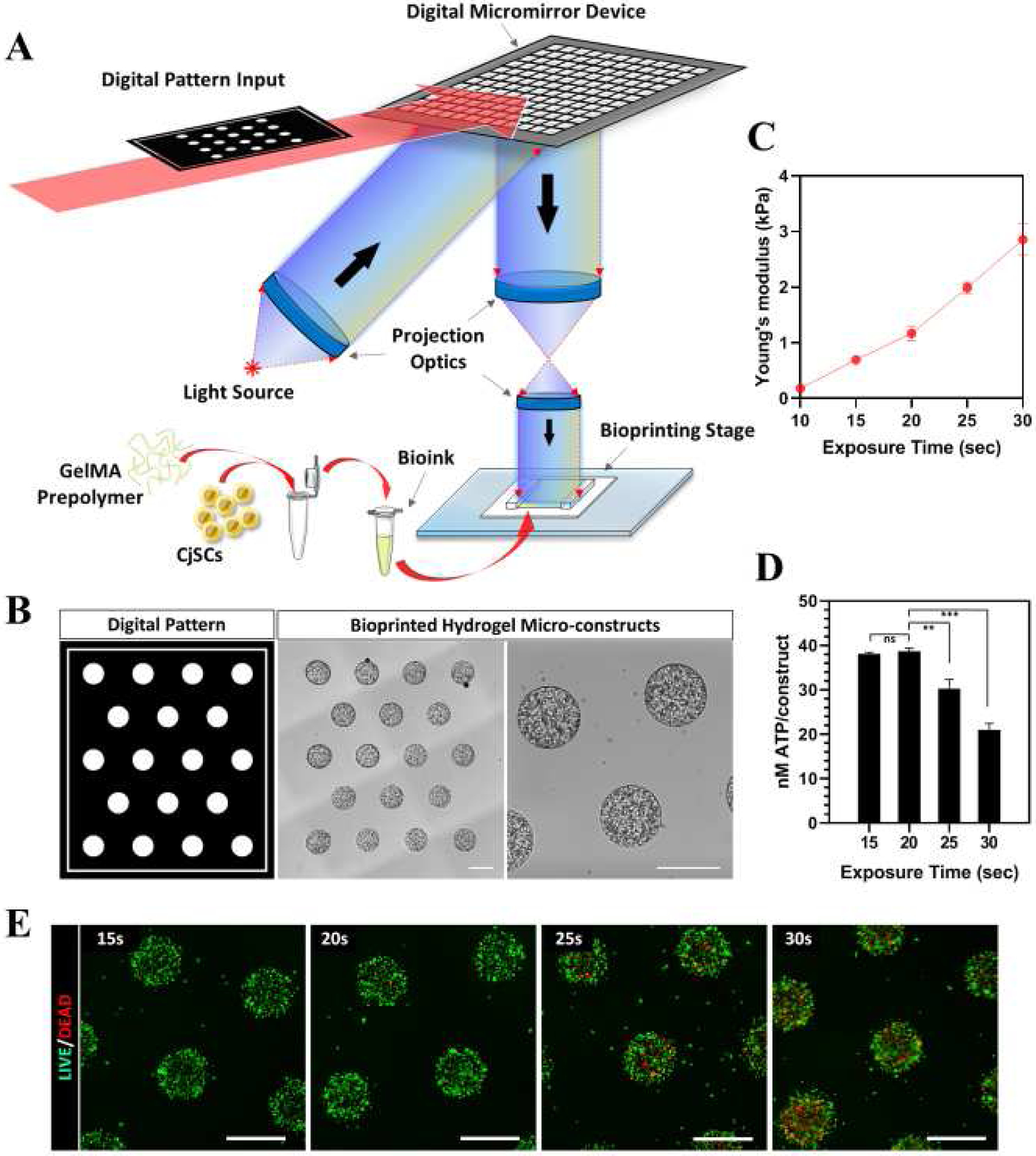

3.2. DLP-based rapid bioprinting of hydrogel micro-constructs support the viability of encapsulated CjSCs

Upon establishing stable in vitro expansion conditions, we next developed an injectable cell delivery system for CjSCs as a strategy towards a potential clinically translatable stem cell therapy. It is critical to ensure that both the biochemical and biophysical properties are optimized to ensure appropriate viability and functionality of CjSCs. Among the different biofabrication techniques available, DLP-based bioprinting systems enable rapid and scalable fabrication of cellularized hydrogel micro-constructs with precise geometrical control[47,50,51,53,54]. Our DLP-based bioprinter utilizes a DMD chip that converts user-defined digital designs into optical patterns to rapidly photopolymerize hydrogel constructs encapsulating cells into well-defined microscale patterns (Fig. 2A). More importantly, the ability to spatiotemporally regulate light exposure enables direct control over crosslinking density and thus the tunability of hydrogel mechanical properties[50,63]. In particular, GelMA has been widely used in biomedical applications including 3D encapsulation of various types of stem cells[69]. Therefore, we chose GelMA to fabricate hydrogel micro-constructs encapsulating CjSCs as a delivery vehicle. The GelMA pre-polymer solution was mixed with the CjSCs solution to form the bioink for DLP-based bioprinting (Fig. 2A). Through parallel projection printing, a total of 18 GelMA-based microscale cylinders (500 μm in diameter; 500 μm in height) encapsulating CjSCs at the density of 107 cells/ml were fabricated in a single print within 30 seconds (Fig. 2B). To optimize the stem cell niche, we tuned the exposure time to adjust the mechanical properties of the hydrogel scaffolds and monitored the change of the encapsulated CjSCs (Supplementary S2A). Mechanical testing results showed a positive linear relationship between the Young’s modulus of the hydrogel micro-constructs and the light exposure time for photo-crosslinking, where increasing exposure time correlated to an increase in hydrogel stiffness ranging from 0.2–3 kPa over a 10 to 30 seconds exposure time range (Fig. 2C). In addition, CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay was performed to measure the cellular metabolic activity of hydrogel micro-constructs (Fig. 2D). After 24 hours in culture, the amount of ATP generated per construct significantly decreased in the groups with 25 seconds exposure (i.e. 30.32 ± 2.04 nM/construct) and with 30 seconds exposure (i.e. 21.04 ± 1.43 nM/construct) compared to the group with 20 seconds exposure (i.e. 38.71 ± 0.64 nM/construct). Consistently, Live/Dead™ staining showed an increased number of dead cells in the groups with higher exposure time of 25 seconds and 30 seconds (Fig. 2E). To confirm the preservation of stem cell phenotype upon varied exposure times, the bioprinted CjSCs were evaluated by real time qPCR for the mRNA expression of the stemness marker P63 (Supplementary S2B). Consistently, the P63 mRNA expression was significantly down-regulated in groups with over 20 seconds exposure. Based on these findings, all subsequent bioprinting experiments encapsulating CjSCs were fabricated at 20 seconds exposure. Furthermore, we have tested the biodegradability of our hydrogel materials under this printing setting and confirmed the hydrogel constructs to be biodegradable (Supplementary S2C, D).

Figure 2. Bioprinting of CjSC-loaded Hydrogel Micro-constructs with Tunable Mechanical Properties.

(A) Schematic of the DLP-based rapid bioprinting process to fabricate hydrogel micro-constructs loaded with CjSCs. (B) Designed digital patterns and the representative corresponding hydrogel micro-constructs encapsulating 107 cells/ml of CjSCs. Scale bars: 500 μm. (C) Plot of compressive modulus of the hydrogel micro-constructs versus light exposure time (mean ± sd, n = 3). (D) Plot of metabolic activity (ATP content/construct) of the bioprinted constructs versus light exposure time (mean ± sd, n = 6, **: P < 0.01, ***: P < 0.001.). The metabolic activity was measured using CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay. (E) Representative images of Live/Dead™ staining of the CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs fabricated under different exposure times. Scale bars: 100 μm.

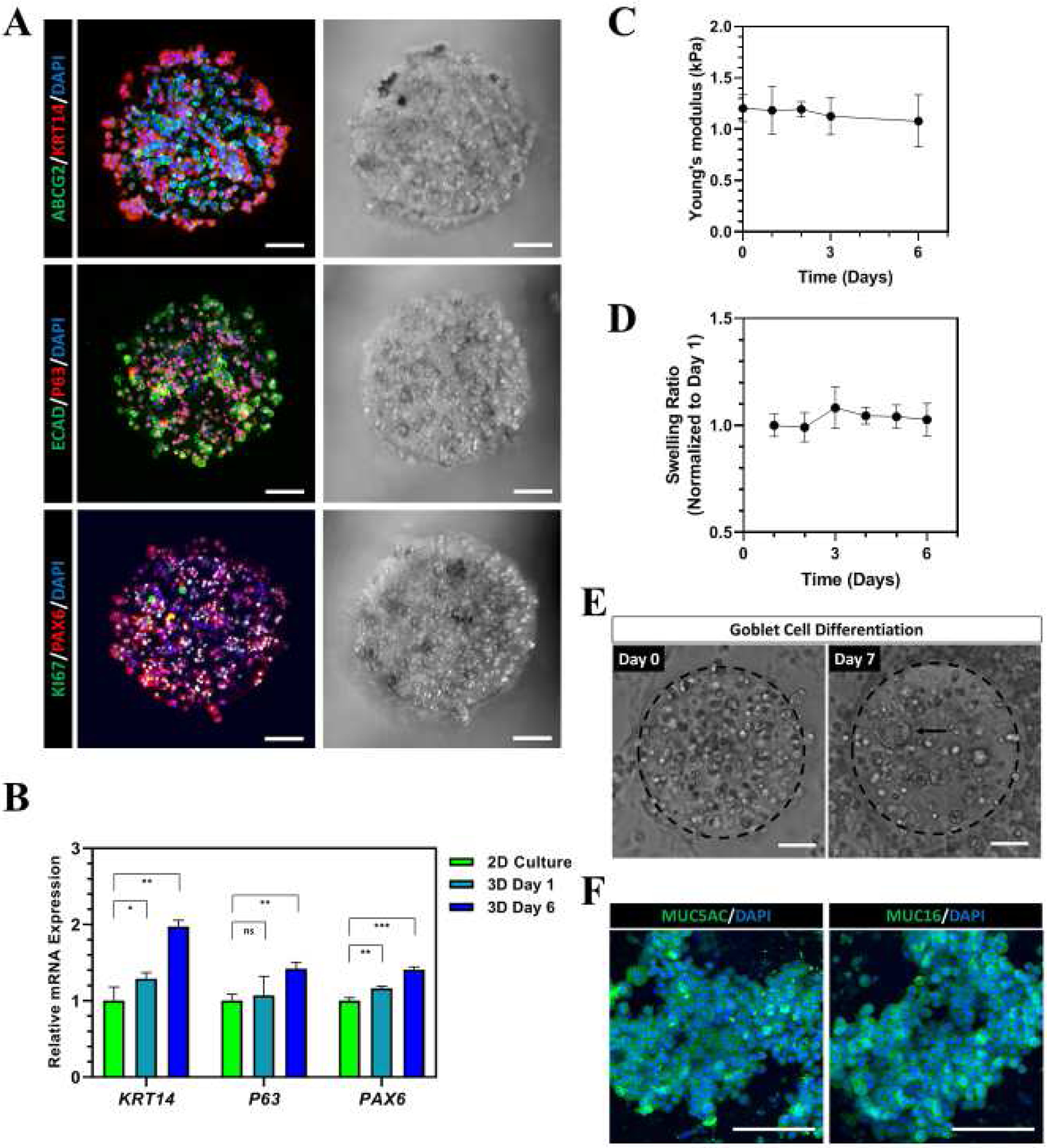

3.3. Bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs support encapsulated CjSC phenotype and differentiation potential

Next, we examined whether the bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs can support stem cell phenotype and differentiation potential of encapsulated CjSCs within a 3D microenvironment. Immunofluorescence staining showed positive expression of the stem cell markers (i.e. ABCG2, KRT14, P63) as well as the lineage markers (i.e. E-Cad, PAX6) after 3 days in culture, which is consistent with the expected expression profile of CjSCs in 2D culture (Fig. 3A). Real time qPCR showed a significant up-regulation of P63, KRT14 and PAX6 in the hydrogel micro-constructs after 6 days in culture relative to hydrogel micro-constructs after one day in culture and the 2D culture group cultured with CjSCM for 6 days. All qPCR data were normalized to the 2D culture group (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the 3D microenvironment significantly enhanced the stem cell phenotype of the encapsulated CjSCs. Building on this observation, we also examined the mechanical stability of the hydrogel micro-constructs over time. Mechanical testing data showed that the compressive modulus of the hydrogel micro-constructs did not significantly change over time and remained stable under physiological conditions (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the equilibrium swelling ratio measurements of acellular hydrogel micro-constructs found no significant changes after 6 days in 1X PBS at 37°C (Fig. 3D). Next, we assessed the functionality of the encapsulated CjSCs in the hydrogel micro-constructs by inducing goblet cell differentiation. After 7 days of differentiation, characteristic large cell aggregates were observed in hydrogel micro-constructs (Fig. 3E). Moreover, immunofluorescence staining confirmed the expression of MUC5AC and MUC16 in the hydrogel micro-constructs and demonstrated that the differentiation potential of the encapsulated CjSCs was preserved (Fig. 3F). In summary, these results showed that the bioprinted constructs not only supported the viability of encapsulated CjSCs but also enhanced the.

Figure 3. Bioprinted Hydrogel Micro-constructs Support 3D Culture of Functional CjSCs.

(A) Representative flurorescence and corresponding bright fied images of immunofluorescence staining on bioprinted CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs after 2 days in culture with CjSCM showing positive expression for ABCG2/KRT14, E-Cad/P63, KI67/PAX6. Scale bars: 100 μm. (B) Real time qPCR showing mRNA expression of stem cell markers (i.e. KRT14, P63) and lineage marker (PAX6) in the encapsulated CjSCs in 3D culture (3D Day 1, 3D Day 6), and CjSCs in 2D culture with CjSCM (2D Culture) for 6 days. The relative mRNA expression was normalized by the mRNA expression of 2D Culture (mean ± sd, n = 3, ns: non-significant, *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, ***: P < 0.001.). (C) Plot of compressive modulus of the 3D hydrogel micro-constructs versus time in culture (mean ± sd, n = 3). (D) Plot of equilibrium swelling ratio of the acellular 3D hydrogel micro-constructs versus time in culture (mean ± sd, n = 3). (E) Representative bright field images of 3D hydrogel micro-constructs at day 0 and day 7 of conjunctival goblet cell differentiation. The arrow highlights the cell aggregate in the construct during differentiation. Scale bars: 100 μm. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of representative hydrogel micro-constructs after 7 days of conjunctival goblet cell differentiation showing positive expression of MUC5AC and MUC16. Scale bars: 100 μm.

3.4. Dynamic suspension culture of bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs maintains encapsulated CjSCs phenotype, proliferation, and differentiation capacity

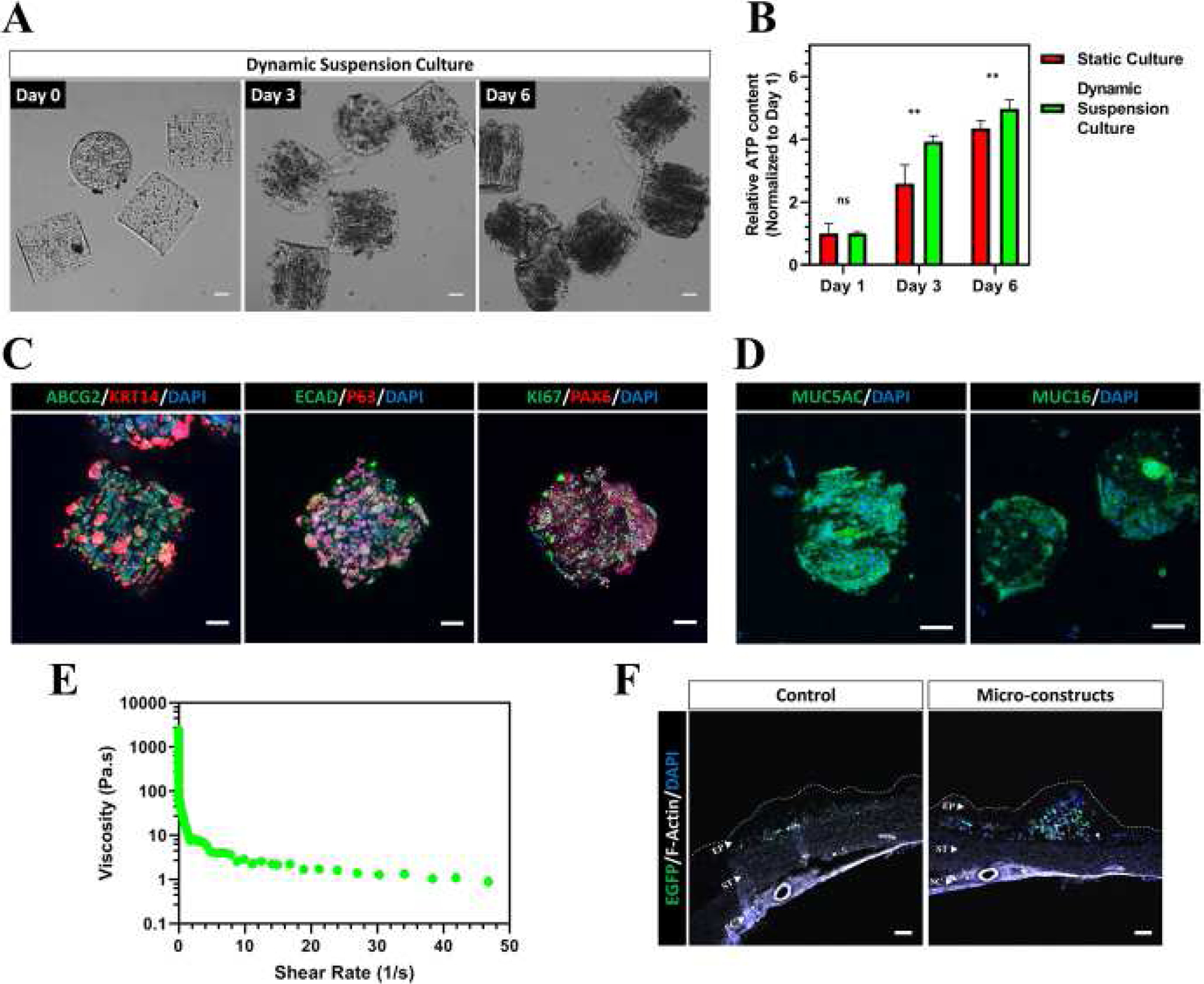

To be clinically translatable, the production of cell-based constructs transplants needs to be scalable to meet the high cell demands within the clinic and provide a cost-effective strategy for large scale in vitro culture. Suspension culture has been largely employed in the form of bioreactors including fed-batch and perfusion setups to efficiently culture cells at a large scale[70]. As a result, we subjected our CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs to dynamic suspension culture and evaluated their efficacy as a potential clinically translatable stem cell expansion system. Samples were cultured in a 6-well plate under constant agitation at 95 rpm and a significant increase in cell density was observed over time as visualized in Fig. 4A. More importantly, CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay demonstrated that dynamic suspension culture significantly enhanced cell viability compared to hydrogel micro-constructs cultured under static conditions at both day 3 and day 6 (Fig. 4B). These results also demonstrated that dynamic suspension culture enabled high cell density culture of CjSCs while maintaining the cell viability (Supplementary S3A). Immunofluorescence staining showed positive expression of the markers ABCG2, KRT14, P63, E-Cad and PAX6 in the hydrogel micro-constructs after 6 days in dynamic suspension culture, which indicated the retention of CjSCs properties in this culture system (Fig. 4C). Goblet cell differentiation was also performed to evaluate the functionality of the CjSCs after dynamic suspension culture. After 7 days of differentiation under dynamic suspension conditions, immunofluorescence staining confirmed positive expression of MUC5AC and MUC16 in the hydrogel micro-constructs (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Dynamic Suspension Culture and Subconjunctival Injectable Delivery of CjSC-loaded Hydrogel Micro-constructs.

(A) CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs in dynamic suspension culture for 6 days. Scale bars: 100 μm. (B) Plot of relative ATP content of the hydrogel micro-constructs in dynamic suspension culture or in static culture over time (mean ± sd, n = 6, **: P < 0.01.). The ATP content was measured via CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay and the relative ATP content was calculated by normalizing the data at each time point with the corresponding data at day 1. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of representative hydrogel micro-constructs samples after 6 days under dynamic suspension culture with ABCG2/KRT14, E-Cad/P63, KI67/PAX6. Scale bars: 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence staining showing positive expression of MUC5AC and MUC16 for representative hydrogel micro-constructs cultured dynamically in suspension after 7 days of conjunctival goblet cell differentiation. Scale bars: 100 μm. (E) Continuous flow rheometry test for the hydrogel composition of the micro-constructs demonstrating shear thinning with increased shear rate (mean, n = 3). (F) Confocal images of the cryosectioned ocular surface containing the conjunctiva and sclera after subconjunctival injection of hydrogel micro-constructs or cell-only control. Sections were stained with anti-EGFP antibody and phalloidin (anti F-Actin) to visualize the histological structures. The EGFP positive signals correspond to the transplanted CjSCs. The white dotted line outlines the boundaries of the conjunctival epithelium. EP: conjunctival epithelium; ST: conjunctival stroma; SC: sclera. Scale bars: 100 μm.

3.5. Subconjunctival cell delivery of bioprinted CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs

Subconjunctival injection is a commonly used and minimally invasive approach for drug delivery to the ocular surface. Taking advantage of the ability to fabricate micron scale constructs via bioprinting, hydrogel micro-constructs containing CjSCs were produced as cylinders measuring in 100 μm diameter and 100 μm in height based on the inner diameter of a 30-gauge needle (i.e. 0.159 mm). We performed rheometry to assess if the bioprinted hydrogels experience shear thinning, which is a necessary property to retain the hydrogel construct’s fidelity after subjecting it to syringe injection (Fig. 4E, Supplementary S3B, C). As the shear rate increases, the viscosity drastically decreases, indicating the hydrogel is shear thinning. To test the injectability directly, hydrogel micro-constructs were repeatedly aspirated and ejected with a 30-gauge syringe needle for 3 times. The geometrical integrity of the hydrogel micro-constructs was unchanged after the repeated aspiration and ejection, indicating the physical robustness of the hydrogel micro-constructs (Supplementary S3D). The samples were then cultured under dynamic suspension as previously described and Live/Dead™ staining at end point (i.e. day 7) showed high viability of the encapsulated CjSCs, which were comparable to the untreated controls (Supplementary S3E). We further tested the subconjunctival injection of the hydrogel micro-constructs on rabbit eyeballs. For ease of visualization, we used lentiviral vectors to label CjSCs with enhanced GFP (EGFP). Hydrogel micro-constructs cultured for 5 days in CjSCM were delivered by subconjunctival injection into the bulbar conjunctival epithelium while single cell suspensions at 106 cells/ml in 100 μl DPBS were also injected as controls. The injections were performed symmetrically on the four points (Supplementary S3C, red arrows) of the rabbit ocular surface with 30-gauge needles using a stereomicroscope. After injection, the rabbit eyeballs were incubated with DF12 supplemented with EGF for 24 hours with constant agitation at 95 rpm. Tissue samples were then analyzed via immunofluorescence staining which confirmed a dense localization of the hydrogel micro-constructs containing EGFP positive CjSCs within the subconjunctival region compared to sparse fluorescence signals in the controls (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these results supported that the bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs can be used to deliver CjSCs into the subconjunctival regions via injection and help immobilize them to the targeted area.

4. Discussion

Over the past few decades, regenerative medicine and stem cell therapies for ocular surface diseases have become a popular field with the growing demand for clinically translatable regenerative approaches[1,18,20]. However, CjSCs, one of the major stem cells on the ocular surface, have not yet been efficiently expanded in vitro[21,23,25]. Moreover, the lack of knowledge of the CjSC niche has made the development of 3D matrices supporting CjSCs growth a challenge[19,71]. Approaches involving minimally invasive ocular surface cell transplantation are critical to the successful application of CjSCs as a cell-based therapy[44]. Here, we present a clinically translatable approach using rapid bioprinting to fabricate hydrogel micro-constructs encapsulating CjSCs for subconjunctival injectable delivery on an ocular surface. We first established an efficient feeder-free in vitro culture system for CjSCs expansion using a culture medium containing a small molecule cocktail (i.e. A83-01 + DMH1 + Y27632). Then, we used DLP-based rapid bioprinting technology to fabricate injectable conjunctival GelMA hydrogel micro-constructs for the subconjunctival delivery of CjSCs. By varying the light exposure time and thus the stiffness of the resulting hydrogel using our bioprinting system, we generated hydrogel micro-constructs that supported the viability and stem cell behavior of the encapsulated CjSCs. The hydrogel micro-constructs also enabled dynamic suspension culture of CjSCs for scalable and efficient expansion. In addition, ex vivo studies highlighted the ability of our CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs for successful subconjunctival delivery using clinically-relevant 30-gauge syringe needles and immobilization into the subconjunctival target site.

CjSCs have been popular in the last decade as they can potentially be applied in stem cell therapy to treat multiple ocular surface diseases[23,25]. However, an efficient in vitro expansion methods for CjSCs derived from the primary conjunctival epithelium with high purity has not yet been reported[21,36]. To expand the CjSCs, we tested a small molecule cocktail that inhibited dual SMAD signaling and ROCK signaling. dSMADi and ROCKi, as well as their synergistic combination, have been reported to support sustained culture of basal stem cells in many other epithelia such as the airway, intestine and skin[27,28]. During primary culture, the formulation with A83-01, DMH1, Y27632 extensively promoted the growth of CjSCs in comparison with the epithelial basal medium. As such, we integrated these small molecules into the epithelial stem cell growth medium and developed the novel culture medium, CjSCM, tailored to support CjSCs proliferation. In this work, we successfully cultured highly homogenous CjSCs in vitro that can be expanded for more than 60 cell doublings while retaining the stem cell properties and the differentiation capacity into conjunctival goblet cells. These findings highlighted a significant step in establishing stable CjSCs in vitro expansion towards the understanding of CjSC-based developmental biology study and the development of novel therapies to treat ocular surface diseases.

Recent studies have revealed that the mechanical properties of extracellular matrix play a key role in cell fate determinant for resident stem cells[18,34,35]. However, despite efforts in locating the stem cell population within the conjunctiva, the mechanical properties of CjSC niche remain largely unknown[21]. Therefore, a biofabrication system with control of biophysical property is needed to recapitulate the CjSC niche. DLP-based rapid bioprinting enables well-controlled tuning of the mechanical properties of the printed structures by simply changing the light exposure time for photo-crosslinking[50,51,53,63]. Due to the tunability of our bioprinting process to control the mechanical properties, we tested a range of hydrogel micro-constructs fabricated using different light exposure times to determine the optimal printing conditions. Our findings revealed that hydrogel micro-constructs fabricated with a 20 seconds light exposure resulted in the highest viability and retention of stem cell phenotype in CjSCs. Notably, our bioprinting system enables the fabrication of 18 cellularized hydrogel micro-constructs simultaneously with customizable geometries in less than a minute. This throughput can be further improved by adjusting the optical system in the bioprinter. Such a high throughput is required for scalable manufacturing applications. Interestingly, the measured modulus of our optimized hydrogel micro-constructs is different from the reported bulk modulus of conjunctival epithelium [72,73]. This result indicates the heterogeneity in mechanical properties of conjunctival epithelial microenvironments and that a relatively soft niche may be favored by resident CjSCs.

Various types of substrates, including 2D substrates such as AM and engineered gelatin membrane as well as 3D matrixes composed of compressed collagen and synthetic polymers have been reported to support ex vivo or in vitro culture of conjunctival epithelial cells[3,15,26,38,74]. However, the expansion of CjSCs has not been well addressed. Maintenance of these stem cell properties in CjSCs is critically important towards the development of effective therapies. In our study, the hydrogel micro-constructs were able to support the culture of encapsulated CjSCs while maintaining expression of the stem cell identity markers as confirmed by both immunofluorescences staining and real time qPCR. Furthermore, we found a significant up-regulation in transcriptional expression of the stem cell markers (i.e. KRT14, P63) and lineage marker (i.e. PAX6) in the hydrogel micro-constructs after 6 days of static culture, suggesting that the hydrogel micro-constructs favorably recapitulated the biomechanical and biochemical matrix properties of native niche for CjSCs to maintain their stem cell phenotype. The hydrogel micro-constructs were also physically stable after prolonged incubation under physiological conditions as no notable changes in the modulus or the equilibrium swelling ratio were detected after 6 days. Furthermore, successful goblet cell differentiation in the hydrogel micro-constructs under static conditions showed preserved functionality of the encapsulated CjSCs. Overall, these results agreed well with the previous findings on the supportive role of bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs in stem cell culture[50,51,53]. Integrated with bioprinting technology, this platform would broaden the utility of CjSCs for cell-based therapies and in vitro disease modeling[75].

Scalable manufacturing is a necessary step towards the development of a clinically translatable product and suspension culture has been favorable for the enhanced uptake of nutrients, reduced cost, and increased scalability[18,70]. Dynamic suspension culture with hydrogel has been found to facilitate stem cell expansion[76–78]. To explore the potential application of our bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs as a clinically relevant cell-based delivery system we performed dynamic suspension culture. The encapsulated stem cells proliferated rapidly under dynamic suspension culture compared with static culture conditions, as the suspension group was 1.5-fold more viable than the static control after 3 days of dynamic suspension culture. This was coupled with significantly higher metabolic activities in the dynamic suspension culture samples compared to the static culture controls. These results indicated that dynamic suspension culture promoted the proliferation and viability of encapsulated CjSCs. In addition, encapsulated CjSCs reserved the stem cell identity and were able to be differentiated towards conjunctival goblet cells post dynamic suspension culture. In summary, dynamic suspension culture promoted viability, proliferation, and retained the stem cell properties and the differentiation potential of CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs and demonstrated their potential for scalable culturing applications.

Patients with severe ocular surface disorders are commonly treated with surgical transplantation of allografts, such as AM [12–16], which involves suture-based surgical transplantation and requires time consuming postsurgical recovery[40]. To address these challenges, we fabricated injectable CjSC-loaded hydrogel micro-constructs applicable for clinical subconjunctival cell delivery. We confirmed with rheometry that the bulk 5% GelMA hydrogel is shear thinning and therefore is a good candidate for an injectable hydrogel application to ensure minimally invasive delivery is maintained and to eliminate potential leakage after injection. We chose to use a 30-gauge syringe needle that is commonly employed in clinical practice for subconjunctival injection. The shear thinning hydrogel also protected the encapsulated cells from shear forces during injection while delivering cells at high densities into the targeted region. To test the injectability of our hydrogel micro-constructs, we prepared hydrogel micro-constructs measuring 100 μm diameter and 100 μm in height, which were designed to fit inside a 30-gauge syringe needle that has an inner diameter of 0.159 mm for injectable delivery. Our findings demonstrated that our bioprinted hydrogel micro-constructs were able to preserve the viability of encapsulated CjSCs after multiple injections through the 30-gauge syringe needle. Furthermore, the rheological properties of hydrogel as well as the tensile nature of the conjunctival epithelium both support the immobilization of hydrogel micro-constructs[72,79,80]. Subconjunctival injection of the hydrogel micro-constructs was able to deliver a relatively large number of cells (approximately 30,000 cells per construct) into the subconjunctival region of rabbit eyeballs with a single injection and facilitated the retention of the transplanted cells within the target region. This work has laid the foundation for future in vivo tests in animal models of ocular surface diseases such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome that would further support clinical applications.

5. Conclusions

DLP-based rapid bioprinting was applied to fabricate injectable hydrogel micro-constructs loaded with CjSCs for ocular stem cell transplantation. By incorporating a small molecule cocktail in the culture medium, we were able to produce homogenous CjSCs with high replicative potential and differentiation capacity. The tunability for mechanical properties, granted by our bioprinting system, enabled the rapid fabrication of hydrogel micro-constructs that promoted the viability and stem cell properties of encapsulated CjSCs. The hydrogel micro-constructs could also be applied to dynamic suspension culture of CjSCs for potential large-scale production in clinical applications. Furthermore, our hydrogel micro-constructs were readily injected through a 30-gauge syringe needle without compromising cell viability or physical deformation, and were suitable for subconjunctival delivery as well as immobilization to the target subconjunctival region as demonstrated in an ex vivo rabbit eyeball model.

The efficient CjSCs feeder-free in vitro expansion approach developed in this study can be translated to different cell therapy applications and provide insight on the stem cell population within the conjunctiva. Our injectable hydrogel micro-constructs can also be extended to incorporate patient-derived cells for autograft or iPSC-derived cells and donor cells for allograft to treat patients requiring ocular surface regeneration. Besides, this study has illustrated the application of bioprinting on CjSCs and provided insight on the mechanical properties that supported the CjSCs encapsulation, which can be translated to future studies with clinically relevant materials and overcome the regulatory limits of GelMA. In addition, our minimally invasive CjSCs delivery approach can serve as a potential strategy for the treatment of ocular diseases such as the ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Implications from the successful expansion of CjSCs are beneficial for the further studies focused on the understanding of eye development and pathogenesis of many ocular surface diseases. The versatility of our hydrogel micro-constructs platform also allows the flexibility to incorporate multiple cell types and/or bioactive constituents for injectable delivery for next generation cell-based therapies such as the injectable delivery of stem cell-derived cytokines or exosomes to enhance the efficacy of clinical treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Shangting You, Jiaao Guan, Henry Hwang, Kathleen Miller, Yi Xiang, Tso-yu Chang, Leilani Kwe for their technical support. We also acknowledge the University of California San Diego School of Medicine Microscopy Core for the imaging equipment and the technical supports offered by the staff there. The UCSD School of Medicine Microscopy Core facility was supported by National Institutes of Health grant P30 NS047101. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R21 EY031122, R01 EB02185) and National Science Foundation (1937653). This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1650112.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings can be shared by the authors upon request.

References

- [1].Nguyen P, Khashabi S, S. C, Ocular Surface Reconstitution, in: Prog. Mol. Environ. Bioeng. - From Anal. Model. to Technol. Appl, 2011. 10.5772/22879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gipson IK, Goblet cells of the conjunctiva: A review of recent findings, Prog. Retin. Eye Res (2016). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Barabino S, Rolando M, Bentivoglio G, Mingari C, Zanardi S, Bellomo R, Calabria G, Role of amniotic membrane transplantation for conjunctival reconstruction in ocular-cicatricial pemphigoid, Ophthalmology. (2003). 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01892-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Li M, Zhu M, Yu Y, Gong L, Zhao N, Robitaille MJ, Comparison of conjunctival autograft transplantation and amniotic membrane transplantation for pterygium: A meta-analysis, Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol (2012). 10.1007/s00417-011-1820-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meller D, Pires RTF, Mack RJS, Figueiredo F, Heiligenhaus A, Park WC, Prabhasawat P, John T, McLeod SD, Steuhl KP, Tseng SCG, Amniotic membrane transplantation for acute chemical or thermal burns, Ophthalmology. (2000). 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Yekta A, Jafarzadehpour E, Ostadimoghaddam H, Kangari H, The prevalence and determinants of pterygium in rural areas, J. Curr. Ophthalmol (2017). 10.1016/j.joco.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rzany B, Mockenhaupt M, Baur S, Schröder W, Stocker U, Mueller J, Holländer N, Bruppacher R, Schöpf E, Epidemiology of erythema exsudativum multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Germany (1990–1992): Structure and results of a population-based registry, J. Clin. Epidemiol (1996). 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bernard P, Vaillant L, Labeille B, Bedane C, Arbeille B, Denoeux JP, Lorette G, Bonnetblanc JM, Prost C, Incidence and Distribution of Subepidermal Autoimmune Bullous Skin Diseases in Three French Regions, Arch. Dermatol (1995). 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690130056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee AJ, Lee J, Saw SM, Gazzard G, Koh D, Widjaja D, Tan DTH, Prevalence and risk factors associated with dry eye symptoms: A population based study in Indonesia, Br. J. Ophthalmol (2002). 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rodríguez-Ares MT, Prevalence of pinguecula and pterygium in a general population in Spain, Eye. (2011). 10.1038/eye.2010.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Barabino S, Chen Y, Chauhan S, Dana R, Ocular surface immunity: Homeostatic mechanisms and their disruption in dry eye disease, Prog. Retin. Eye Res (2012). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Clearfield E, Muthappan V, Wang X, Kuo IC, Conjunctival autograft for pterygium, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev (2016). 10.1002/14651858.CD011349.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Morgan PV, Suh JD, Hwang CJ, Nasal floor mucosa: New donor site for mucous membrane grafts, Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg (2016). 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liu J, Sheha H, Fu Y, Liang L, Tseng SCG, Update on amniotic membrane transplantation, Expert Rev. Ophthalmol (2010). 10.1586/eop.10.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dehghani S, Rasoulianboroujeni M, Ghasemi H, Keshel SH, Nozarian Z, Hashemian MN, Zarei-Ghanavati M, Latifi G, Ghaffari R, Cui Z, Ye H, Tayebi L, 3D-Printed membrane as an alternative to amniotic membrane for ocular surface/conjunctival defect reconstruction: An in vitro & in vivo study, Biomaterials. (2018). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pan Q, Angelina A, Marrone M, Stark WJ, Akpek EK, Autologous serum eye drops for dry eye, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev (2017). 10.1002/14651858.CD009327.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tseng SCG, He H, Zhang S, Chen SY, Niche Regulation of Limbal Epithelial Stem Cells: Relationship between Inflammation and Regeneration, Ocul. Surf (2016). 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xia H, Li X, Gao W, Fu X, Fang RH, Zhang L, Zhang K, Tissue repair and regeneration with endogenous stem cells, Nat. Rev. Mater 3 (2018) 174–193. 10.1038/s41578-018-0027-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, Koizumi N, Kinoshita S, Ocular surface reconstruction using stem cell and tissue engineering, Prog. Retin. Eye Res (2016). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Williams R, Lace R, Kennedy S, Doherty K, Levis H, Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine Approaches for the Anterior Segment of the Eye, Adv. Healthc. Mater 7 (2018). 10.1002/adhm.201701328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stewart RMK, Sheridan CM, Hiscott PS, Czanner G, Kaye SB, Human Conjunctival Stem Cells are Predominantly Located in the Medial Canthal and Inferior Forniceal Areas, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 56 (2015) 2021–2030. 10.1167/iovs.14-16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stern JH, Tian Y, Funderburgh J, Pellegrini G, Zhang K, Goldberg JL, Ali RR, Young M, Xie Y, Temple S, Regenerating Eye Tissues to Preserve and Restore Vision, Cell Stem Cell. (2018). 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ramos T, Scott D, Ahmad S, An Update on Ocular Surface Epithelial Stem Cells: Cornea and Conjunctiva, Stem Cells Int (2015). 10.1155/2015/601731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ouyang H, Xue Y, Lin Y, Zhang X, Xi L, Patel S, Cai H, Luo J, Zhang M, Zhang M, Yang Y, Li G, Li H, Jiang W, Yeh E, Lin J, Pei M, Zhu J, Cao G, Zhang L, Yu B, Chen S, Fu XD, Liu Y, Zhang K, WNT7A and PAX6 define corneal epithelium homeostasis and pathogenesis, Nature. (2014). 10.1038/nature13465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Majo F, Rochat A, Nicolas M, Jaoudé GA, Barrandon Y, Oligopotent stem cells are distributed throughout the mammalian ocular surface, Nature. (2008). 10.1038/nature07406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bertolin M, Breda C, Ferrari S, Van Acker SI, Zakaria N, Di Iorio E, Migliorati A, Ponzin D, Ferrari B, Lužnik Z, Barbaro V, Optimized protocol for regeneration of the conjunctival epithelium using the cell suspension technique, Cornea. (2019). 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mou H, Vinarsky V, Tata PR, Brazauskas K, Choi SH, Crooke AK, Zhang B, Solomon GM, Turner B, Bihler H, Harrington J, Lapey A, Channick C, Keyes C, Freund A, Artandi S, Mense M, Rowe S, Engelhardt JF, Hsu YC, Rajagopal J, Dual SMAD Signaling Inhibition Enables Long-Term Expansion of Diverse Epithelial Basal Cells, Cell Stem Cell. (2016). 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang C, Lee HJ, Shrivastava A, Wang R, McQuiston TJ, Challberg SS, Pollok BA, Wang T, Long-Term In Vitro Expansion of Epithelial Stem Cells Enabled by Pharmacological Inhibition of PAK1-ROCK-Myosin II and TGF-β Signaling, Cell Rep 25 (2018) 598–610.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kobielak K, Stokes N, De La Cruz J, Polak L, Fuchs E, Loss of a quiescent niche but not follicle stem cells in the absence of bone morphogenetic protein signaling, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0703004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Oshimori N, Fuchs E, Paracrine TGF-β signaling counterbalances BMP-mediated repression in hair follicle stem cell activation, Cell Stem Cell (2012). 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].He XC, Zhang J, Tong WG, Tawfik O, Ross J, Scoville DH, Tian Q, Zeng X, He X, Wiedemann LM, Mishina Y, Li L, BMP signaling inhibits intestinal stem cell self-renewal through suppression of Wnt-β-catenin signaling, Nat. Genet (2004). 10.1038/ng1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tata PR, Mou H, Pardo-Saganta A, Zhao R, Prabhu M, Law BM, Vinarsky V, Cho JL, Breton S, Sahay A, Medoff BD, Rajagopal J, Dedifferentiation of committed epithelial cells into stem cells in vivo, Nature. (2013). 10.1038/nature12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Amano M, Nakayama M, Kaibuchi K, Rho-kinase/ROCK: A key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity, Cytoskeleton. (2010). 10.1002/cm.20472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lane SW, Williams DA, Watt FM, Modulating the stem cell niche for tissue regeneration, Nat. Biotechnol (2014). 10.1038/nbt.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vining KH, Mooney DJ, Mechanical forces direct stem cell behaviour in development and regeneration, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol (2017). 10.1038/nrm.2017.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Meller D, Dabul V, Tseng SCG, Expansion of conjunctival epithelial progenitor cells on amniotic membrane, Exp. Eye Res (2002). 10.1006/exer.2001.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ricardo JRS, Cristovam PC, Filho PAN, Farias CC, De Araujo AL, Loureiro RR, Covre JL, De Barros JN, Barreiro TP, Dos Santos MS, Gomes JAP, Transplantation of conjunctival epithelial cells cultivated ex vivo in patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency, Cornea. (2013). 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31825034be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Drechsler CC, Kunze A, Kureshi A, Grobe G, Reichl S, Geerling G, Daniels JT, Schrader S, Development of a conjunctival tissue substitute on the basis of plastic compressed collagen, J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 11 (2017) 896–904. 10.1002/term.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cheung AY, Sarnicola E, Eslani M, Kurji KH, Genereux BM, Govil A, Holland EJ, Infectious keratitis after ocular surface stem cell transplantation, Cornea. (2018). 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Riemens A, Te Boome LCJ, Kalinina Ayuso V, Kuiper JJW, Imhof SM, Lokhorst HM, Aniki R, Impact of ocular graft-versus-host disease on visual quality of life in patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: Questionnaire study, Acta Ophthalmol (2014). 10.1111/aos.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nassiri N, Eslani M, Panahi N, Mehravaran S, Ziaei A, Djalilian AR, Ocular graft versus host disease following allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A review of current knowledge and recommendations, J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res (2013). 10.1038/s41409-018-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Agraval U, Rundle P, Rennie IG, Salvi S, Fresh frozen amniotic membrane for conjunctival reconstruction after excision of neoplastic and presumed neoplastic conjunctival lesions, Eye. (2017). 10.1038/eye.2016.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ashraf NN, Adhi MI, Outcome of application of amniotic membrane graft in ocular surface disorders, J. Pak. Med. Assoc (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang Z, Injectable biomaterials for stem cell delivery and tissue regeneration, Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 17 (2017) 49–62. 10.1080/14712598.2017.1256389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Koivusalo L, Karvinen J, Sorsa E, Jönkkäri I, Väliaho J, Kallio P, Ilmarinen T, Miettinen S, Skottman H, Kellomäki M, Hydrazone crosslinked hyaluronan-based hydrogels for therapeutic delivery of adipose stem cells to treat corneal defects, Mater. Sci. Eng. C (2018). 10.1016/j.msec.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ke Y, Wu Y, Cui X, Liu X, Yu M, Yang C, Li X, Polysaccharide hydrogel combined with mesenchymal stem cells promotes the healing of corneal alkali burn in rats, PLoS One. (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0119725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Qu X, Zhu W, Huang S, Li YS, Chien S, Zhang K, Chen S, Relative impact of uniaxial alignment vs. form-induced stress on differentiation of human adipose derived stem cells, Biomaterials. (2013). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Soman P, Lee JW, Phadke A, Varghese S, Chen S, Spatial tuning of negative and positive Poisson’s ratio in a multi-layer scaffold, Acta Biomater. (2012). 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hribar KC, Choi YS, Ondeck M, Engler AJ, Chen S, Digital plasmonic patterning for localized tuning of hydrogel stiffness, Adv. Funct. Mater (2014). 10.1002/adfm.201400274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yu C, Ma X, Zhu W, Wang P, Miller KL, Stupin J, Koroleva-Maharajh A, Hairabedian A, Chen S, Scanningless and continuous 3D bioprinting of human tissues with decellularized extracellular matrix, Biomaterials. 194 (2019) 1–13. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ma X, Qu X, Zhu W, Li YS, Yuan S, Zhang H, Liu J, Wang P, Lai CSE, Zanella F, Feng GS, Sheikh F, Chien S, Chen S, Deterministically patterned biomimetic human iPSC-derived hepatic model via rapid 3D bioprinting, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A (2016). 10.1073/pnas.1524510113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Soman P, Tobe BTD, Lee JW, Winquist AM, Singec I, Vecchio KS, Snyder EY, Chen S, Three-dimensional scaffolding to investigate neuronal derivatives of human embryonic stem cells, Biomed. Microdevices (2012). 10.1007/s10544-012-9662-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yu C, Zhu W, Sun B, Mei D, Gou M, Chen S, Modulating physical, chemical, and biological properties in 3D printing for tissue engineering applications, Appl. Phys. Rev 5 (2018). 10.1063/1.5050245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hribar KC, Finlay D, Ma X, Qu X, Ondeck MG, Chung PH, Zanella F, Engler AJ, Sheikh F, Vuori K, Chen SC, Nonlinear 3D projection printing of concave hydrogel microstructures for long-term multicellular spheroid and embryoid body culture, Lab Chip. (2015). 10.1039/c5lc00159e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Raghava S, Hammond M, Kompella UB, Periocular routes for retinal drug delivery, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv (2004). 10.1517/17425247.1.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nowak JA, Fuchs E, Isolation and culture of epithelial stem cells, Methods Mol. Biol (2009). 10.1007/978-1-59745-060-7_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].McCauley HA, Guasch G, Three cheers for the goblet cell: Maintaining homeostasis in mucosal epithelia, Trends Mol. Med (2015). 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Henriksson JT, Coursey TG, Corry DB, De Paiva CS, Pflugfelder SC, IL-13 stimulates proliferation and expression of mucin and immunomodulatory genes in cultured conjunctival goblet cells, Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci (2015). 10.1167/iovs.14-15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].McCauley HA, Liu CY, Attia AC, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Zhang Y, Whitsett JA, Guasch G, TGFβ signaling inhibits goblet cell differentiation via SPDEF in conjunctival epithelium, Dev. (2014). 10.1242/dev.117804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tang M, Xie Q, Gimple RC, Zhong Z, Tam T, Tian J, Kidwell RL, Wu Q, Prager BC, Qiu Z, Yu A, Zhu Z, Mesci P, Jing H, Schimelman J, Wang P, Lee D, Lorenzini MH, Dixit D, Zhao L, Bhargava S, Miller TE, Wan X, Tang J, Sun B, Cravatt BF, Muotri AR, Chen S, Rich JN, Three-dimensional bioprinted glioblastoma microenvironments model cellular dependencies and immune interactions, Cell Res. (2020). 10.1038/s41422-020-0338-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shirahama H, Lee BH, Tan LP, Cho NJ, Precise tuning of facile one-pot gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) synthesis, Sci. Rep (2016). 10.1038/srep31036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang P, Li X, Zhu W, Zhong Z, Moran A, Wang W, Zhang K, Chen S, 3D bioprinting of hydrogels for retina cell culturing, Bioprinting. (2018). 10.1016/j.bprint.2018.e00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ma X, Yu C, Wang P, Xu W, Wan X, Lai CSE, Liu J, Koroleva-Maharajh A, Chen S, Rapid 3D bioprinting of decellularized extracellular matrix with regionally varied mechanical properties and biomimetic microarchitecture, Biomaterials. (2018). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]