Dear Editor,

Diseases caused by ischemia, including coronary artery disease and stroke, are a leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Restoration of the blood and oxygen supply after restriction also causes tissue damage by activating a number of pathological pathways, such as inflammatory, oxidative stress, and cell death pathways that are mediated by microRNAs and hypoxia-inducible factors [1, 2]. In recent years, thrombolytic and surgical treatments for patients with acute stroke or coronary artery disease have improved and are effective, but currently there is no approved therapy for use after an ischemic stroke [3]. This lack of effective neuroprotective drugs suggests a shortage of proper therapeutic targets for treating ischemia-reperfusion injury. Thus, to uncover new molecules that regulate or mediate ischemia-reperfusion injury, it is necessary to identify novel targets for drug development.

The genetic basis of anoxia tolerance is not well understood. Using an anoxia- or hypoxia-tolerant animal model to find new genes involved in such resistance may uncover new pathways for further investigation. One such model is Drosophila, which has been used to investigate the susceptibility or tolerance to anoxia or hypoxia [4, 5]. An estimated 75% of known human disease genes are matched in the genetic code of Drosophila, thus it has frequently been used to model human diseases and these models have been successfully used to study the interactions between disease-related molecules and to screen for disease-modifying drugs and genes [6]. Using a Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease [7], we previously conducted a genetic screen for modifiers and identified some genes as novel regulators or mediators of intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation and its associated neural degeneration [8]. Importantly, genetic reduction of a mouse homologue of one of these modifiers found in Drosophila (eighty-five requiring 3 protein in mice and rolling blackout in flies) also suppresses the neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [9]. Thus, genetic screening for modifiers of disease phenotypes in Drosophila is a reliable means of discovering novel mediators of pathogenesis.

Previously, we established an efficient and reliable assay for studying the mortality and motor impairment caused by anoxia-reoxygenation in flies [10]. Flies subjected to an extended period of anoxia can recover and become active again when placed in a normoxic environment. Nevertheless, anoxia-reoxygenation stress induces damage in flies such as motor deficits, increased caspase-3 staining in the brain, and increased mortality [10]. If the duration of anoxia is > 1 h, flies will die in the following days, and the cumulative death rate on day 5 is linearly and positively correlated with the duration of anoxia [10]. Here, using this anoxia assay, we conducted a genetic screen and isolated several lines with increased tolerance to anoxia-reoxygenation.

Pgant4 is a well-conserved O-glycosyltransferase that glycosylates transport and Golgi organization protein 1 (Tango1) and protects it from degradation by cleavage from Furin, a peptidase [11]. Tango1 (melanoma inhibitory activity 3, MIA3, in mammals), via interaction with multiple proteins, organizes endoplasmic reticulum exit sites (ERES), mediates cargo-sorting and the formation of large secretory vesicles, and controls or influences the secretion of large vesicles (e.g. collagens, lipoproteins, and other molecules), as well as the general secretion of small molecules in all tissues of both flies and mammals [12]. Further analysis has shown that both Pgant4 and Tango1 mediate anoxia-reoxygenation damage in Drosophila. Our study suggests that the Pgant4/Tango1-controlled ER-Golgi pathway, along with the molecules being transported, is a novel and important mechanism underlying ischemia-reperfusion injury.

To screen for genes involved in the damage caused by anoxia-reoxygenation in Drosophila, mutant flies with different identified deletions of DNA segments on the 3rd chromosome or a few on the 2nd chromosome (Fig. 1A) were separately crossed for 10 generations to an isogenic wild-type strain, w1118. The progeny containing the chromosome deficiencies and control w1118 (Ctrl) flies were exposed to anoxia for 3 h, then transferred to a normoxic condition and the cumulative death rate for each genotype was calculated in the following 5 days and compared to that of the Ctrl flies. Three deficient lines, BL stock # 6965, 7675, and 7681, were found to be more resistant to anoxia-reoxygenation (Fig. 1A and data not shown). To determine the specific genes involved in anoxia-reoxygenation injury, line 6965 and another three lines with overlapping deficiency, 9599, 6507, and 7787, were tested again for resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation (Fig. 1B). Lines 6965, 7787, and 6507, but not 9599, were more resistant to anoxia-reoxygenation (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that the affected gene or genes were located between the break points at 2L:3466844 and 3473493 (~6 kb), which covered 5 genes: msl-2, ND-PDSW, CG3238, CG31776, and Pgant4. Testing the available temporary mutants of these genes (see supplementary materials for method) in the anoxia-reoxygenation assay showed that the transposon-insertion mutation, PBac{WH}Pgant4f02186 (Pgant4f02186/f02186 or Pgant4f02186/+) was more resistant to anoxia-reoxygenation (Fig. 1D). To confirm that this increased resistance was due to the genetic reduction of Pgant4, we precisely removed the transposon insertion in Pgant4 with a transposase-expressing transgene, P{Δ2-3}99B, which generated the revertant chromosome and obtained 2 groups of flies: Pgant4rev/rev and Pgant4rev/f02186, which we then tested in the anoxia-reoxygenation assay. As shown in Fig. 1D, the revertant chromosome acted just like a wild-type chromosome. Therefore, downregulation of the Pgant4 protein level increases the resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation, or Pgant4 mediates the anoxia-reoxygenation damage. This was further confirmed by the increased resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation in flies with Pgant4 knocked down either ubiquitously or in neurons alone (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Genetic reduction of Pgant4 increases anoxia resistance and decreases active caspase-3 levels in the brain of Drosophila exposed to anoxia-reoxygenation. A List of Drosophila deficiency lines in a genetic screen for increased resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation. The Bloomington (BL) stock number and the deleted region in the chromosome are indicated. BL stock numbers 6965, 7675, and 7681 (indicated by asterisks) exhibit reduced mortality in the anoxia-reoxygenation assay. A hundred flies were screened for each line. B Relative chromosomal map of four deficient lines used to identify the Pgant4 gene. C (i) Deficient lines BL numbers 6965, 7787, and 6507, but not 9599, show increased resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation, compared with w1118 flies (Ctrl). (ii) Cumulative deaths 5 days after anoxia exposure (for clearer comparison between groups). D (i) Cumulative death rates of Ctrls and flies with different combinations of the Pgant4f02186 allele and Pgant4rev. (ii) Cumulative deaths 5 days after anoxia exposure. E (i) Cumulative death rates of Ctrl and Gal4 flies ([Gal4]actin-2/+ and [Gal4]elav/+) just expressing the transcription factor Gal4, and (ii) Ctrls (as in E i) and flies with Pgant4 knocked down ubiquitously (Pgant4v7286/[Gal4]actin-2 and Pgant4v46910/[Gal4]actin-2) or just in neurons (Pgant4v7286/[Gal4]elav), and UAS-transgenic control flies (Pgant4v7286/+ and Pgant4v46910/+). The UAS flies harbor the transgene for expressing double-stranded RNA against Pgant4, but this expression requires Gal4. Notably, the cumulative death rate of [Gal4]actin-2/+ is significantly higher than that of Ctrl; this might be due to the homozygous lethal insertion of the [Gal4]actin-2 transgene into a locus unrelated to Pgant4. In C–E, the cumulative death rates of flies exposed to 3 h of anoxia before recovery in normoxic conditions are analyzed over the next 5 days (represented as cumulative death percentage). Error bars, ± SEM; n = 100–200 flies/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Ctrl. F, Above, representative images of active caspase-3 immunofluorescence in Ctrl, Pgant4 homozygous mutants (Pgant4f02186/f02186), and revertant Pgant4 (Pgant4rev/rev) flies after 3 h of anoxia exposure and 3 h recovery (white squares, areas used to quantify the active caspase-3 level in each hemisphere of the fly brain; images represent 5–10 fly heads/group; scale bars, 50 µm). Below, fluorescence intensity relative to Ctrl, Error bars, ± SEM; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA

To investigate the effect of Pgant4 reduction on the neural damage caused by anoxia-reoxygenation, we analyzed the active caspase-3 levels in the brains of flies. Previously, we showed that flies exposed to the anoxia assay have increased caspase-3 staining in the brain [10]. Under normoxic conditions, the levels of active caspase-3 were comparable in Ctrl, Pgant4f02186/f02186, and Pgant4rev/rev flies, as assessed using immunofluorescence (Fig. 1F). After exposure to anoxia for 3 h, followed by 3 h of recovery in normoxia, the active caspase-3 level was significantly increased in Ctrl and Pgant4rev/rev flies, but unchanged in Pgant4f02186/f02186 flies, when compared with flies without anoxia exposure (Fig. 1F), further confirming the protective effect of Pgant4 reduction.

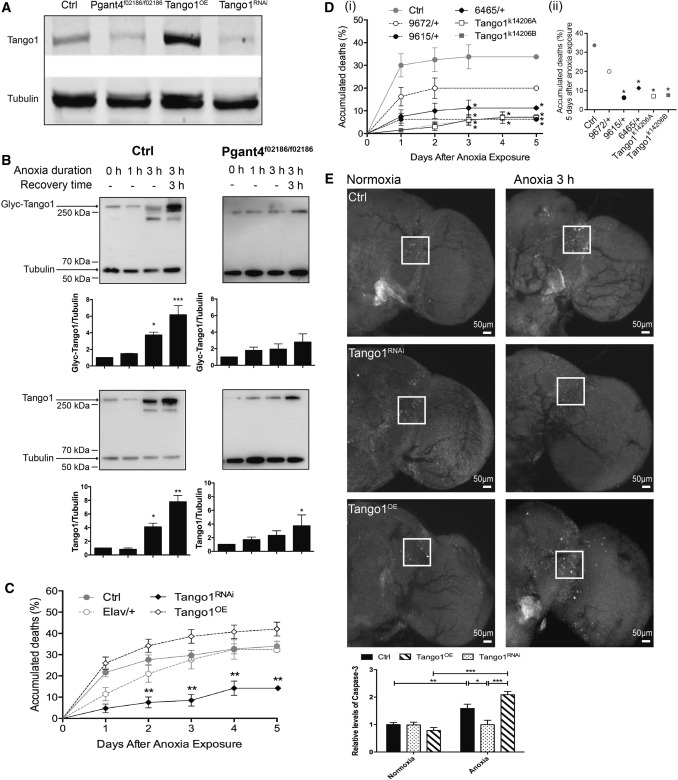

Tango1 is a substrate of Pgant4 and its o-glycosylation by Pgant4 protects it from degradation by cleavage from Furin, a peptidase [11]. To examine the downstream consequences of Pgant4 reduction in anoxia-reoxygenation, we analyzed the o-glycosylated and total levels of Tango1 with an antibody recognizing o-glycosylated Tango1 and an antibody against Tango1 in Ctrl and Pgant4f02186/f02186 flies after exposure to anoxia (Fig. 2A). First, the specificity and recognition of the Drosophila Tango1 by the antibody against mammalian MIA3 were assessed (Fig. 2A), and the band in the immunoblot recognized by the anti-MIA3 antibody displayed the correct molecular weight. Furthermore, the density of the band decreased when Pgant4 was reduced or Tango1 was knocked down in neurons, and increased when Tango1 was overexpressed. Then, Ctrl and Pgant4f02186/f02186 flies were exposed to 0, 1, or 3 h of anoxia and collected immediately after exposure or allowed to recover for 3 h in normoxia before analysis. In Ctrl flies, the level of glycosylated Tango1 was unchanged after exposure to anoxia for 1 h, but increased by ~ 4-fold after exposure for 3 h and by ~ 6-fold after 3 h of anoxia and 3 h of recovery in normoxic conditions (Fig. 2B, upper left). Consistent with this, the total amount of Tango1 was unchanged, or increased by ~ 4- and ~ 8-fold at the corresponding time points (Fig. 2B, lower left). In the Pgant4f02186/f02186 flies, the total amount of Tango1 was markedly lower than that in Ctrl flies; note that the densities of Tango1 and tubulin in the immunoblots of both Ctrl and Pgant4f02186/f02186 flies in Fig. 2B are consistent with a previous report that loss of Pgant4 reduces total Tango1 [11]. Importantly, in the Pgant4f02186/f02186 flies, both o-glycosylated and total levels of Tango1 remained unchanged or had much less of an increase at the corresponding time points (Fig. 2B, upper and lower right).

Fig. 2.

Anoxia-reoxygenation markedly increases the glycosylated and total Tango1, which is suppressed by downregulation of Pgan4. A Immunoblots showing the specificity and recognition of Drosophila Tango1 by anti-MIA3 antibody. The anti-MIA3 antibody detects a band at 250 kDa, the correct molecular weight for Tango1, but with a different density in control w1118 (Ctrl) flies, Pgant4 homozygous mutants (Pgant4f02186/f02186), with Tango1 knocked down in neurons (Tango1RNAi), and flies with Tango1 overexpression (Tango1OE). Tubulin served as loading control; n = 30–40 fly heads/group. B Representative immunoblots and levels of o-glycosylated Tango1 (Glyc-Tango1) and total Tango1 (Tango1) in Ctrl (left) and Pgant4f02186/f02186 (right) flies after exposure to anoxia for 0, 1, or 3 h, or exposure to 3 h of anoxia before recovery in 3 h under normoxic conditions. Tubulin served as loading control. Each experiment was repeated at least three times; n = 30–40 fly heads/group. C Cumulative death rates of Ctrl, [Gal4]elav (Elav/+), Tango1RNAi, and Tango1OE flies. Data for Ctrl flies is the same as in Fig. 1D. D (i) Cumulative death rates of Ctrl, deficient (9672/+, 9615/+, and 6465/+) and transposon-insertion mutants of Tango1 (Tango1k14206A/+ and Tango1k14206B/+). (ii) Cumulative deaths 5 days after anoxia exposure. In C and D, n = 100–200 flies/group. E Above, representative images of active caspase-3 immunofluorescence after 3 h of anoxia and 3 h recovery in Ctrl, Tango1RNAi, and Tango1OE flies (white squares, areas used to quantify caspase-3 levels in each hemisphere; scale bars, 50 µm), Below, fluorescence intensity relative to Ctrl. n = 5–10 fly heads/group); error bars, ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA

To test whether the protective effect of Pgant4 reduction is mediated by the downregulation of Tango1, we knocked down Tango1 in neurons (Tango1RNAi) and measured its effects on the mortality and active caspase-3 level in the anoxia-reoxygenation assay. Tango1RNAi flies indeed showed a significant reduction in both mortality and active caspase-3 in the brain (Fig. 2C, E). Consistent with this, chromosome deficiencies and transposon-insertion mutations of Tango1 also increased the resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation (Fig. 2D). To further test the role of Tango1 in anoxia-reoxygenation damage, we investigated the effect of its upregulation in flies overexpressing Tango1 in neurons (Tango1OE). As expected, Tango1OE flies exhibited an increased cumulative death rate and showed increased active caspase-3 levels after exposure to anoxia (Fig. 2C, E). Thus, the ability to tolerate anoxia, anoxia-reoxygenation, or both is inversely controlled by the level of Tango1 protein.

Using a newly developed anoxia-reoxygenation assay and an unbiased genetic screen followed by identification and characterization of isolated mutants with increased resistance to anoxia-reoxygenation, we obtained conclusive evidence showing that the expression levels of both Pgant4 and Tango1 inversely determine the ability to tolerate anoxia or anoxia-reoxygenation in Drosophila. First, downregulation of Pgant4, either ubiquitously or just in neurons, decreased the mortality and active caspase-3 levels in the brain after exposure to anoxia-reoxygenation. Second, in control flies, prolonged anoxia robustly increased the glycosylated and total levels of Tango1, and this upregulation continued to increase even after removal from anoxic conditions and may contribute to reperfusion injury. Third, the upregulation of Tango1 caused by anoxia-reoxygenation was dramatically suppressed by the downregulation of Pgant4. Fourth, Tango1 knockdown or overexpression alone improved or worsened the mortality and activation of caspase-3 respectively in anoxia-reoxygenation exposure.

Pgant4 belongs to the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase superfamily that catalyze the transfer of a GalNAc sugar onto the hydroxyl groups of serine and threonine in secreted or membrane-bound proteins [13]. Pgant4 glycosylates Tango1 and protects it from Furin-mediated proteolysis in Drosophila [11]. Pgant4 is orthologous to mammalian GALNT10 and GALNTL6 (flybase.org), both of which are ubiquitously expressed in the mammalian body, and GALNTL6 is especially enriched in human heart (Genecards). Tango1/MIA3 mediates cargo sorting and the formation of large ER transport vesicles, as well as organizing ERES in both flies and mammals, directly controlling the bulk secretion of large proteins such as collagens and lipoproteins, and indirectly influencing the general secretion of small molecules [12]. Down regulation of Tango1 reduces ERES and impairs not only the secretion of collagen and large extracellular matrix proteins, but also general secretion, whereas overexpression of Tango1 or even truncated Tango1 missing the cargo-binding domain greatly increases ERES and general secretion. In our study, anoxia-reoxygenation induced a ~ 4–8-fold elevation of Tango1, and presumably markedly increased the secretion of both large extracellular matrix proteins and small secretory molecules or membrane-bound proteins. The nature of these secreted or transported molecules via the Pgant4/Tango1-ER Golgi pathway and their roles in anoxia-reoxygenation or ischemia-reperfusion require further study.

A previous study suggested that flies less susceptible to protein unfolding are more tolerant of anoxia, but a genetic basis for this response to anoxia had not been found [4]. Furthermore, in a genome-wide association analysis of flies exposed to anoxia, there were no change in heat shock proteins (Hsps), chaperones that repair or protect unfolded proteins in response to stress, suggesting an upstream or downstream regulator may be involved [4]. Our study revealed that Pgant4/Tango1 may be this regulator, particularly as the Src homology 3 domain of Tango1 interacts with Hsp47 to package collagens into vesicles for transport [14]. Proteins, after correct folding and post-translational modification, are shuttled between the ER and Golgi to undergo additional modifications for maturation before transport to the plasma membrane, organelles, or extracellular space [15]. Tango1 directly and indirectly binds to many proteins to form macromolecular complexes at ERES, including the subunits of coat protein complex II (COPII), which are required for the transport of most secretory proteins and transmembrane proteins [12]. The up to 8-fold increase of Tango1 in anoxia-reoxygenation might have hijacked too many COPII and other common players along the ER-Golgi pathway, and greatly inhibited other Pgant4/Tango1-independent transport.

Our study opens a new pathway to investigate the mechanisms underlying anoxia-reoxygenation or ischemia and reperfusion injury, and this may have implications for therapeutic strategies for diseases and conditions such as coronary artery disease and stroke. Our study provides a working model that involves partially reducing either Pgant4 or Tango1 to dramatically inhibit anoxia-reoxygenation damage, indicating that regulating or managing the Pgant4/Tango1-mediated secretion or transport of molecules that mediate ischemia and reperfusion, rather than targeting these molecules individually, may be a much more efficient therapeutic strategy for treating ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771416, 81650110527 and 8197100), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (201740153) and Key Discipline of Chongming District, Shanghai, China, 2018.

Conflict of interest

Fude Huang’s research in this study received financial support from Nuo-Beta Pharmaceutical Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd (Nuo-Beta), Fude Huang and Wenan Wang have share holdings in Nuo-Beta. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Qingqing Du, Nastasia K. H. Lim, Yiling Xia, Wangchao Xu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Fude Huang, Email: huangfd@nuo-beta.com.

Wenan Wang, Email: wangwenan@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion-from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mo JL, Pan ZG, Chen X, Lei Y, Lv LL, Qian C, et al. MicroRNA-365 knockdown prevents ischemic neuronal injury by activating oxidation resistance 1-mediated antioxidant signals. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:815–825. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00371-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karsy M, Brock A, Guan J, Taussky P, Yashar M, Park MS. Neuroprotective strategies and the underlying molecular basis of cerebrovascular stroke. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42:E3. doi: 10.3171/2017.1.focus16522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell JB, Overby PF, Gray AE, Smith HC, Harrison JF. Genome-wide association analysis of anoxia tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2019;9:2989–2999. doi: 10.1534/g3.119.400421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou D, Visk DW, Haddad GG. Drosophila, a golden bug, for the dissection of the genetic basis of tolerance and susceptibility to hypoxia. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:239–247. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181b27275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandey UB, Nichols CD. Human disease models in drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:411–436. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao XL, Wang WA, Tan JX, Huang JK, Zhang X, Zhang BZ, et al. Expression of -amyloid induced age-dependent presynaptic and axonal changes in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1512–1522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H, Han M, Li Q, Zhang X, Wang WA, Huang FD. Automated rapid iterative negative geotaxis assay and its use in a genetic screen for modifiers of Aβ42-induced locomotor decline in Drosophila. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1526-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Wei M, Wu Y, Qin H, Li W, Ma X, et al. Amyloid β oligomers suppress excitatory transmitter release via presynaptic depletion of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1193. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia Y, Xu W, Meng S, Lim NKH, Wang W, Huang FD. An efficient and reliable assay for investigating the effects of hypoxia/anoxia on Drosophila. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0173-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Ali Syed Z, Van Dijk H’rd I, Lim JM, Wells L, Ten Hagen KG. O-Glycosylation regulates polarized secretion by modulating Tango1 stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7296–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322264111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito K, Chen M, Bard F, Chen S, Zhou H, Woodley D, et al. TANGO1 facilitates cargo loading at endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Cell. 2009;136:891–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ten Hagen KG, Tran DT, Gerken TA, Stein DS, Zhang Z. Functional characterization and expression analysis of members of the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase family from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35039–35048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa Y, Ito S, Nagata K, Sakai LY, Bächinger HP. Intracellular mechanisms of molecular recognition and sorting for transport of large extracellular matrix molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E6036–E6044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609571113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sicari D, Igbaria A, Chevet E. Control of protein homeostasis in the early secretory pathway: current status and challenges. Cells. 2019;8:1347. doi: 10.3390/cells8111347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.