Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been reported to cause worse outcomes in patients with underlying cardiovascular disease, especially in patients with acute cardiac injury, which is determined by elevated levels of high-sensitivity troponin. There is a paucity of data on the impact of congestive heart failure (CHF) on outcomes in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We conducted a literature search of PubMed/Medline, EMBASE, and Google Scholar databases from 11/1/2019 till 06/07/2020, and identified all relevant studies reporting cardiovascular comorbidities, cardiac biomarkers, disease severity, and survival. Pooled data from the selected studies was used for metanalysis to identify the impact of risk factors and cardiac biomarker elevation on disease severity and/or mortality.

Results

We collected pooled data on 5967 COVID-19 patients from 20 individual studies. We found that both non-survivors and those with severe disease had an increased risk of acute cardiac injury and cardiac arrhythmias, our pooled relative risk (RR) was — 8.52 (95% CI 3.63–19.98) (p < 0.001); and 3.61 (95% CI 2.03–6.43) (p = 0.001), respectively. Mean difference in the levels of Troponin-I, CK-MB, and NT-proBNP was higher in deceased and severely infected patients. The RR of in-hospital mortality was 2.35 (95% CI 1.18–4.70) (p = 0.022) and 1.52 (95% CI 1.12–2.05) (p = 0.008) among patients who had pre-existing CHF and hypertension, respectively.

Conclusion

Cardiac involvement in COVID-19 infection appears to significantly adversely impact patient prognosis and survival. Pre-existence of CHF, and high cardiac biomarkers like NT-pro BNP and CK-MB levels in COVID-19 patients correlates with worse outcomes.

Keywords: Acute cardiac injury, Cardiac arrhythmia, Mortality risk, Cardiac biomarkers, COVID-19

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) virus that infects cells via membrane bound angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE 2) receptors.1 Multiple studies have reported the spectrum of clinical manifestations of the disease and highlighted the involvement of the cardiovascular system.1,2 The prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with COVID-19 is reported to range from 4% to 40% and the evidence is growing that its presence is linked with unfavorable outcomes, including, but not limited to ICU admissions and increased mortality.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 A recent metanalysis showed increased all-cause mortality and risk of severe form of COVID-19 infection in patients with underlying CVD.8 There are several small studies showing elevated biomarkers in COVID-19 patients suggesting myocardial injury. However, there are conflicting data regarding the association of cardiac biomarkers with the severity of disease.4,9 There is a paucity of data on outcomes in COVID-19 patients with underlying congestive heart failure (CHF).10,11 We conducted this study to delineate the influence of various cardiac conditions (especially CHF) on outcomes of patients with COVID-19 and to determine the prognostic value of cardiac biomarkers — Troponin I, Creatine Kinase-MB (CK-MB), and N-terminal-proB-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP).

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted by following the guidelines laid down by preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).12

2.1. Objectives

-

1.

To evaluate the demographics, and occurrence of cardiac injury and arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19.

-

2.

To assess the impact of hypertension (HTN) and CHF on mortality in patients with COVID-19 infection.

-

3.

To evaluate the levels of different cardiac biomarkers in subsets of COVID-19 patients based on their severity of illness (severe or non-severe) and final outcome (alive or deceased).

2.2. Search strategy

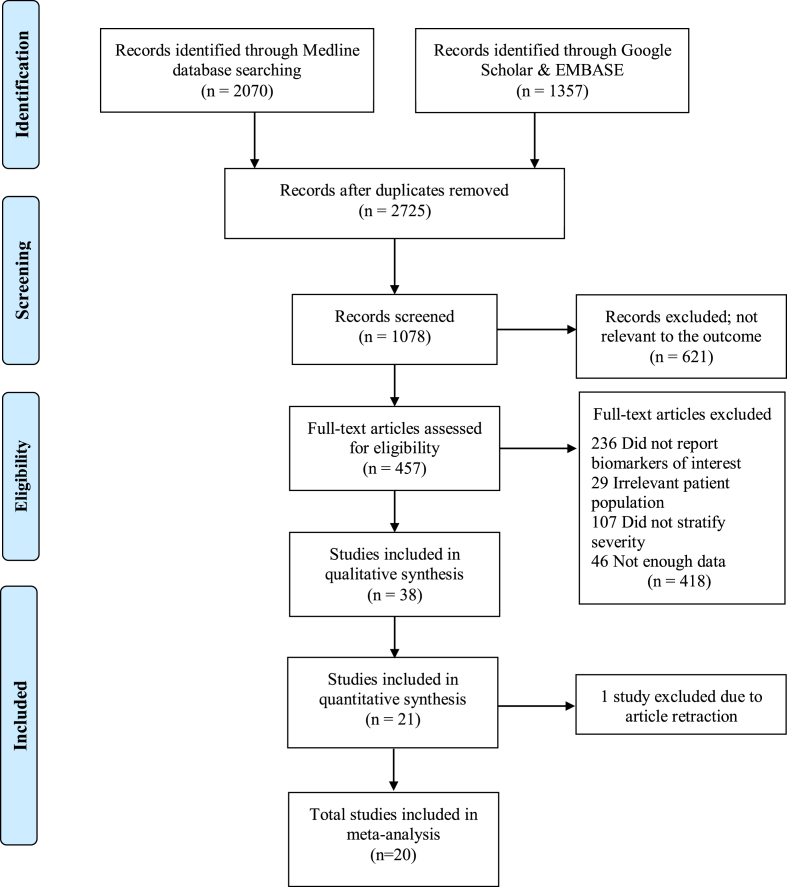

We systematically searched PubMed/Medline (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), EMBASE, and Google Scholar databases using following search terms or keywords: “(COVID) AND (Clinical); ((heart) OR (myocard∗)) AND (COVID); (COVID) AND (Troponin); (Coronavirus) AND (Heart).” Two authors (S.L. and T.D.) independently reviewed 3427 citations to identify the number of studies satisfying our inclusion criteria. Of these, 702 were duplicates; 1647 were correspondence letters, case reports, and review articles; and 621 articles that were irrelevant to the study question based on their titles and abstracts, and hence, were excluded from the review. Abstracts and full-length articles of 457 studies were then evaluated and 38 of them were included for the qualitative synthesis. Of these, 17 articles did not report biomarkers of our interest leaving 21 studies to be included for the quantitative assessment (Fig. 1). One study was later on excluded owing to article retraction, leaving a total of 20 studies for our final meta-analysis. Any conflicts regarding the study selection were resolved by a mutual consensus.13 All in-vivo studies on animals or tissue samples were excluded.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the search and inclusion strategy.

2.3. Eligibility criteria and study selection

All the published studies between December 2019 and May 2020 that reported the COVID-19 patients’ characteristics, their co-existing comorbidities, and laboratory data stratified on the basis of patient outcome and/or disease severity were included in this systematic review. Our exclusion criteria were confined to the articles that either did not report laboratory values of cardiac biomarkers or did not classify patients’ outcomes based on the severity of infection or the final patient outcome.

2.4. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (S.L. and T.D.) extracted the data. We collected the following variables: Author(s) names; year of publication; study design; duration of study period; sample population; demographic and baseline characteristics of patients; laboratory biomarkers to identify cardiac injury (namely — CK-MB, cardiac sensitive troponin I, NT-proBNP); disease severity (severe/non-severe); and in-hospital patient outcomes (alive/deceased). The criteria used by authors for classifying patients as severe or non-severe is provided in eTable 1 in Supplement. Acute cardiac injury is often identified in the presence of elevated serum levels of high-sensitivity troponin 14; however no specific cut-off value exists.

2.5. Data synthesis and analyses

We classified patients under the spectrum of “fulminant” based on severity of their disease progression including death, whereas survivors and non-severe cases were collectively classified under “non-fulminant” spectrum of illness. We also compared the relative risk of death during index admission to the hospital between patients with and without pre-existing CHF.

Categorical variables between the patient groups were summarized using the Manel-Haenszel risk ratios (RR)15,16 while the continuous data variables were summarized using the mean difference (MD), along with their corresponding 95% CI. These pooled estimates were calculated by using the random-effects meta-analysis model. For calculating tau-square (τ2), we used Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) method over the traditional DerSimonian-Laird method, as it is known to perform better with fewer number of studies and has lower type-I error rates even when combining studies with unequal sample size.17 Studies that had reported descriptive values as median (interquartile range) were transformed to mean ± standard deviations by using Wan method.18

Publication bias was evaluated by constructing funnel-plots of the effect size against its standard error (SE) and performing Egger’s linear regression test of funnel-plot asymmetry. Between-study heterogeneity was calculated with Higgins I2 statistic. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistical significance. We used “meta” and “metafor” packages for conducting our meta-analyses.19,20 Statistical analyses were conducted by S.L. in R (v3.6.3) and reviewed by S.R and Z.S.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Overall, we collected 5967 patients from 20 individual study reports. Table 1 outlines the details of studies and demographics of patients included in this systematic review. The age of patients ranged from 23 to 95 years, with a prevalence of females ranging from 19% to 52%. The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking was observed to be ranging from 10% to 82%, 8%–24%, and 4%–14%, respectively. Ten studies reported their findings stratified according to patient outcome6,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 10 studies reported findings in severe and non-severe COVID-19 patients.3,4,9,30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36

Table 1.

Patient demography and details of studies and in the systematic review.

| Author | Duration | Region | Sample |

Age |

Sex |

Comorbidities (N) |

Mortality (%)‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N) | (years) | (M/F) | Hypertension | DM | Smoking | CHF | ||||

| Zhou et al | Dec 29–31 Jan | China | 191 | 56 (46–67) | 119/72 | 58 | 36 | 11 | 44 | 28 |

| Chen et al | Jan 13 – Feb 12 | China | 274 | 62 (44–70) | 171/103 | 93 | 47 | 12 | 01 | 41 |

| Inciardi et al | Mar 04 – Mar 25 | Italy | 99 | 68.5 | 80/19 | 63 | 18 | 12 | 21 | 26 |

| Du et al | Jan 09 – Feb 15 | China | 85 | 65.8 ± 14.2 | – | 32 | 19 | NA | NA | 100 |

| Wang D., et al | Till Feb 10 | China | 107 | 51 (36–55) | 57/50 | 26 | 11 | NA | NA | 18 |

| Aggarwal et al | Mar 01 – April 04 | U.S. | 16 | 67 (38–95) | 12/4 | 09 | 05 | NA | 04 | 50 |

| Cao et al | Jan 03 – Feb 01 | China | 102 | 54 (37–67) | 53/49 | 28 | 11 | NA | NA | 16 |

| Shi et al | Jan 01 – Feb 23 | China | 671 | 63 (50–72) | 322/349 | 199 | 97 | NA | 22 | 9 |

| Wang L., et al | Jan 01 – Mar 05 | China | 339 | 69 (65–76) | – | 138 | 54 | NA | 58 | 19 |

| He et al | Feb 03 – Feb 24 | China | 54 | 68 | 34/20 | 24 | 13 | NA | NA | 48 |

| Huang et al∗ | – | China | 41 | 49 (41–68) | 30/11 | 06 | 08 | 03 | NA | 15 |

| Wang D., et al∗ | Jan 01 – Feb 03 | China | 138 | 56 (42–68) | 75/63 | 43 | 14 | NA | NA | 4.3 |

| Petrilli et al∗ | Mar 01 – April 08 | U.S. | 2729 | 64 | 1672/1057 | 1693 | 950 | 141 | 349 | 24 |

| Yang et al∗ | Jan 28 – Feb 12 | China | 136 | 56 (44–64) | 66/70 | 36 | 20 | NA | NA | 17 |

| Hu et al∗ | Jan 08 – Mar 10 | China | 323 | 61 (23–91) | 152/145 | 95 | 36 | 38 | NA | 11 |

| Deng et al∗ | Jan 06 - Mar 20 | China | 112 | 65 (49–70.8) | 57/55 | 36 | 19 | NA | NA | 12.5 |

| Wan et al∗ | Feb 08 – till end | China | 135 | 47 (36–55) | 73/62 | 13 | 12 | 09 | NA | 0.7 |

| Lu et al∗ | – | China | 265 | NA | NA | 52 | 21 | NA | NA | 0.38 |

| Han et al∗ | Feb 01 – Feb 18 | China | 47 | 65 (31–87) | NA | 18 | 07 | 07 | NA | NA |

| Peng et al∗ | Jan 20 – Feb 15 | China | 112 | 62 (55–67) | 53/49 | 92 | 23 | NA | 40 | 15 |

Descriptive values are represented as (n) and age as Mean ± standard deviation or Median (interquartile range).

Studies marked with asterisk (∗) compared outcomes in severe and non-severe cases of COVID-19; rest of the studies reported variables for survivors and non-survivors. CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; NA: Not available.

‡Mortality (%) numbers are rounded-off to the closest integer value.

3.2. Assessment of underlying cardiac conditions

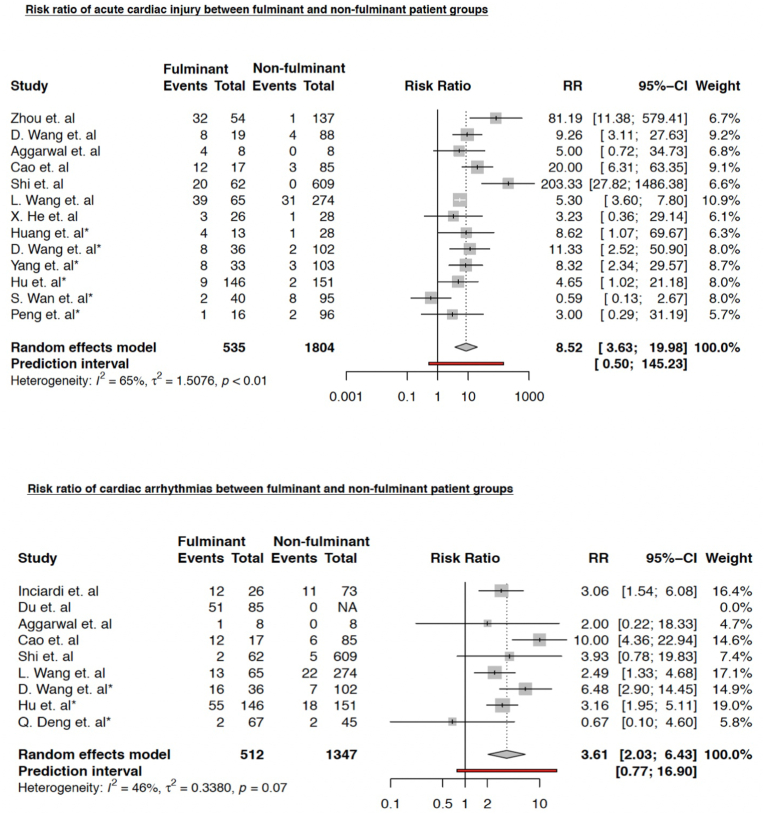

We found that both non-survivors and those who had severe COVID-19 infection (fulminant group) had an 8-fold increased risk of acute cardiac injury compared to survivors/non-severe patients (non-fulminant group); pooled RR was 8.52 (95% CI 3.63–19.98) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). A similar trend of increased risk was observed for any cardiac arrhythmia; pooled RR was 3.61 (95% CI 2.03–6.43) (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk ratio (RR) of acute cardiac injury (ACI) in fulminant vs non-fulminant patient groups. Studies marked with asterisk (∗) compared severe and non-severe COVID-19 cases.

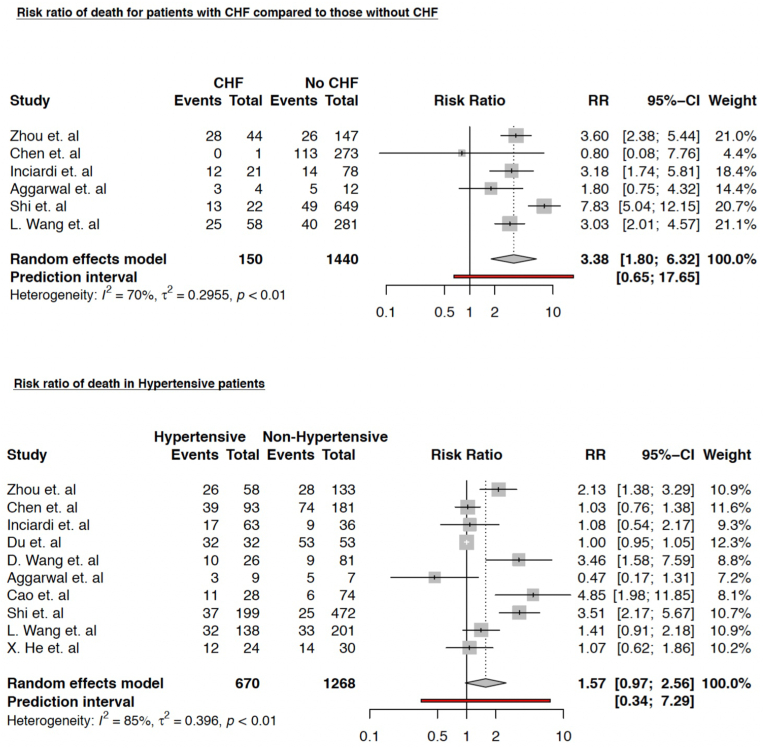

We also found that the risk of death was significantly higher in CHF patients; RR 3.38 (95% CI 1.80–6.32) (p = 0.004); however, the risk of in-hospital death in patients with underlying hypertension was not found to be statistically significant; RR 1.57 (95% CI 0.97–2.56) (p = 0.06) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relative risk of in-hospital death between patients — with and without pre-existing. congestive heart failure; and — with and without pre-existing hypertension. Studies marked with asterisk (∗) compared severe and non-severe COVID-19 cases.

3.3. Trends in the serum levels of cardiac biomarkers

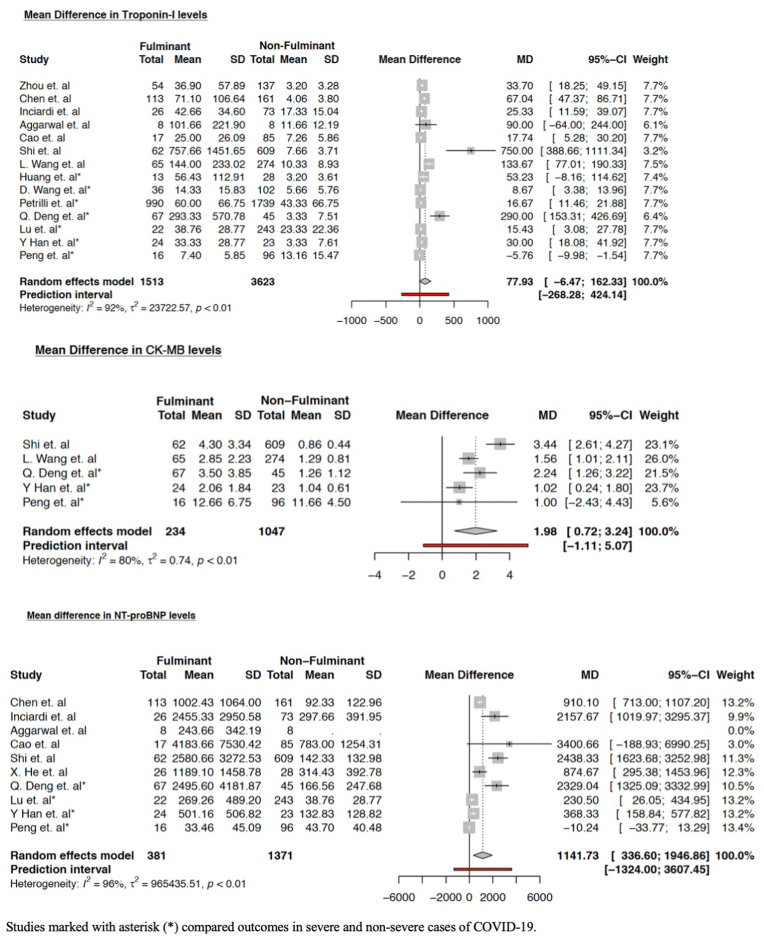

Levels of Troponin-I were higher in fulminant group but did not reach statistical significance; mean difference (MD) was 77.93 pg/mL (95% CI -6.47–162.33) (p = 0.067). The levels of CK-MB [MD 1.98 ng/mL (95% CI 0.72–3.24) (p = 0.012)] and NT-proBNP [MD 1141.73 pg/mL (95% CI 336.60–1946.86) (p = 0.011)] were found to be significantly higher among the patient groups with severe COVID-19 infection across individual studies. Trends of cardiac biomarkers are summarized in forest plots in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Forrest plot showing the mean differences in serum levels of cardiac biomarkers among varying patient groups. Studies marked with asterisk (∗) compared severe and non-severe COVID-19 cases.

To elicit a better understanding of confounding effects of other variables, we used meta-regression models of cardiac biomarkers, adjusting for patient’s age, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking status. Our regression model showed statistically significant association in the mean difference of serum levels of NT-pro BNP only with diabetes mellitus status of the patients (eTable 2 in Supplement).

4. Discussion

We observed that patients who suffered from severe COVID-19 infection and non-survivors (fulminant group) had a substantially higher burden of cardiovascular diseases compared to non-severe cases and survivors (non-fulminant group). These patients were also found to be at an increased risk of acute cardiac injury and cardiac rhythm irregularities, likely owing to the involvement of myocardium in coronavirus infection which is evidenced by the elevated levels of cardiac biomarkers. Our results are consistent with other meta-analyses, which concluded that patients with underlying cardiovascular disorders have a higher propensity to develop severe and fulminant COVID-19 infection.37,38 Furthermore, in a latest study, Lala et al found that the presence of cardiovascular diseases in COVID-19 patients increases their susceptibility to develop myocardial damage, and is associated with a higher mortality risk.39 Although, the prior systemic reviews and metanalyses have looked into the combined effect of underlying cardiovascular comorbidities on COVID-19 outcomes, this study is novel as we largely focused on impact of isolated CHF on COVID-19 outcomes. Also, prior studies had patients mostly from Southeast Asia, whereas, we incorporated patients from other geographic regions as well.

COVID-19 is a novel infectious disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that binds to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE 2) receptors to gain entry into the human body.1,14 These receptors are present on various organs including lung alveolar epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells and cardiac myocytes and pericytes.40, 41, 42 The precise mechanisms for myocardial injury in COVID-19 cases are unclear at the moment. However, there are 2 proposed hypotheses — myocardial insult could either be due to “cytokine storm” suggested by elevated levels of interleukin-6, lactate dehydrogenase among a few other biomarkers; or due to the direct effect on the myocardium by causing a down-regulation of the expression of ACE2 protein expression within the cardiac myocytes. This ACE2 protein is speculated to have a protective effect against myocardial and lung injury by reducing This ACE2 protein is speculated to have a protective effect against myocardial and lung injury by reducing blood pressure, inflammation and fibrosis.1,43, 44, 45

Several rhythm abnormalities like atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and pulseless electrical activity have been associated with COVID-19.46 The exact mechanism of underlying rhythm abnormalities is still not completely elucidated. Myocarditis has been associated with COVID-19, and elevation of inflammatory biomarkers can also suggest direct involvement of electrical conduction system.47 Moreover, the medications used in treatment of COVID-19 patients can increase QTc-interval and cause life threatening arrhythmias.48 This presence of inflammatory milieu and direct myocardial insult might have led to increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias as noted in our study.

We also observed that presence of heart failure is associated with increased mortality among COVID-19 patients. This is consistent with other studies who have shown similar findings.21 ACE 2 counteracts the effect of angiotensin II in states with excessive activation of renin-angiotensin system like heart failure.1 CHF patients are known to have dysregulation of intracellular calcium handling mechanism49 and COVID-19 can cause hypoxia induced excessive intracellular calcium leading to cardiac myocyte apoptosis.50 This can lead to increased mortality observed in patients with CHF.

NT-pro BNP has been known to be elevated in patients with CHF51 and its elevation is associated with poor prognosis in patients with sepsis, pneumonia.52 Increased ventricular wall stress due to hypoxia induced pulmonary hypertension, impaired clearance in critically ill patients with renal failure are a few mechanisms which can lead to elevation of NT-pro BNP levels in COVID-19 patients.53 High NT-pro BNP levels had been associated with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients.54 A recent systemic review which predominantly included patient population from China showed a similar finding of increased mortality.55 Although we had patients from different geographical regions of the world, yet these findings were consistent with our study.

5. Limitations

Our systematic review inevitably has certain limitations such as between-study heterogeneity and the potential publication bias. Another concerning aspect is the retrospective study designs of included researches, and the lack of individual patient severity and medical information (such as smoking status), because of which we were unable to adjust the confounding effects of comorbidities and other variables.

6. Conclusion

In summary, the presence of CHF in patients with COVID-19 is associated with increased mortality and worse outcomes during index admission. There is increased risk of acute cardiac injury and cardiac arrhythmia among non-survivors and severe COVID-19 patients. Elevated cardiac biomarkers like NT-pro BNP and CK-MB are associated with poor prognosis and can help identify “at-risk” COVID-19 patients. We suggest close monitoring of severe COVID-19 patients with underlying cardiac comorbidities to reduced mortality.

Statement of ethics

This manuscript is a systematic review and does not require approval from the ethical board.

Source(s) of funding

None.

Author contributions

S.L. and T.D. conceptualized the idea, performed literature search, extracted data; S.L. performed the data analysis; S.R. and Z.S. reviewed the results; S.R. drafted the manuscript; P.A., A.G., and I.M. contributed in drafting the manuscript; A.S. and Z.S. did the critical review and final approval.

Statement of authorship

All the authors whose names are listed above take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Declaration of competing interest

The author(s) report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2020.12.002.

Contributor Information

Amandeep Goyal, Email: agoyal3@kumc.edu.

Zubair Shah, Email: zshah2@kumc.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Clerkin K.J., Fried J.A., Raikhelkar J. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried J.A., Ramasubbu K., Bhatt R. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;141:1930–1936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K., Fang Y.Y., Deng Y. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal G., Cheruiyot I., Aggarwal S. Association of cardiovascular disease with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity: a meta-analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45:100617. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng Y.D., Meng K., Guan H.Q. [Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 112 cardiovascular disease patients infected by 2019-nCoV] Zhonghua Xinxueguanbing Zazhi. 2020;48:E004. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200220-00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomasoni D., Italia L., Adamo M. COVID-19 and heart failure: from infection to inflammation and angiotensin II stimulation. Searching for evidence from a new disease. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IoMUCotSaEIoDi Biomedicine. National Academic Press (US); Washington (DC): 1995. Society’s Choices: Social and Ethical Decision Making in Biomedicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madjid M., Safavi-Naeini P., Solomon S.D., Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman K., Greenland S., Lash T. 2008. Modern Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tripepi G., Jager K.J., Dekker F.W., Zoccali C. Stratification for confounding--part 1: the Mantel-Haenszel formula. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116:317–321. doi: 10.1159/000319590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inthout J., Ioannidis J.P., Borm G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balduzzi S., Rucker G., Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Base Ment Health. 2019;22:153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.W V Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Software. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inciardi R.M., Adamo M., Lupi L. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1821–1829. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Y., Tu L., Zhu P. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from wuhan. A retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1372–1379. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang D., Yin Y., Hu C. Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24:188. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal S., Garcia-Telles N., Aggarwal G., Lavie C., Lippi G., Henry B.M. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): early report from the United States. Diagnosis (Berl) 2020;7:91–96. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao J., Tu W.J., Cheng W. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi S., Qin M., Cai Y. Characteristics and clinical significance of myocardial injury in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2070–2079. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He X.W., Lai J.S., Cheng J. [Impact of complicated myocardial injury on the clinical outcome of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients] Zhonghua Xinxueguanbing Zazhi. 2020;48:E011. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200228-00137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L., He W., Yu X. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020;80:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan S., Xiang Y., Fang W. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol. 2020;92:797–806. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu L., Chen S., Fu Y. Risk factors associated with clinical outcomes in 323 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Q., Xie L., Zhang W. Analysis of the clinical characteristics, drug treatments and prognoses of 136 patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Pharm Therapeut. 2020;45:609–616. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng Q., Hu B., Zhang Y. Suspected myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19: evidence from front-line clinical observation in Wuhan, China. Int J Cardiol. 2020;311:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrilli C.M., Jones S.A., Yang J. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han Y., Zhang H., Mu S. Lactate dehydrogenase, an independent risk factor of severe COVID-19 patients: a retrospective and observational study. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:11245–11258. doi: 10.18632/aging.103372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu H., Ai J., Shen Y. 2020. A Descriptive Study of the Impact of Diseases Control and Prevention on the Epidemics Dynamics and Clinical Features of SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak in Shanghai, Lessons Learned for Metropolis Epidemics Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li B., Yang J., Zhao F. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109:531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shamshirian A., Heydari K., Alizadeh-Navaei R., Moosazadeh M., Abrotan S., Hessami A. 2020. Cardiovascular Diseases and COVID-19 Mortality and Intensive Care Unit Admission: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lala A., Johnson K.W., Januzzi J.L. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L., Lely A.T., Navis G., van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.South A.M., Brady T.M., Flynn J.T. ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting enzyme 2), COVID-19, and ACE inhibitor and Ang II (angiotensin II) receptor blocker use during the pandemic: the pediatric perspective. Hypertension. 2020;76:16–22. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen L., Li X., Chen M., Feng Y., Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1097–1100. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oudit G.Y., Kassiri Z., Jiang C. SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:618–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.South A.M., Shaltout H.A., Washburn L.K., Hendricks A.S., Diz D.I., Chappell M.C. Fetal programming and the angiotensin-(1-7) axis: a review of the experimental and clinical data. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019;133:55–74. doi: 10.1042/CS20171550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rali A.S., Ranka S., Shah Z., Sauer A.J. Mechanisms of myocardial injury in coronavirus disease 2019. Card Fail Rev. 2020;6:e15. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2020.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kochav S.M., Coromilas E., Nalbandian A. Cardiac arrhythmias in COVID-19 infection. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Driggin E., Madhavan M.V., Bikdeli B. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roden D.M., Harrington R.A., Poppas A., Russo A.M. Considerations for drug interactions on QTc interval in exploratory COVID-19 treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2623–2624. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dridi H., Kushnir A., Zalk R., Yuan Q., Melville Z., Marks A.R. Intracellular calcium leak in heart failure and atrial fibrillation: a unifying mechanism and therapeutic target. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0394-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Januzzi J.L., Jr., Camargo C.A., Anwaruddin S. The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brueckmann M., Huhle G., Lang S. Prognostic value of plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in patients with severe sepsis. Circulation. 2005;112:527–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.472050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pirracchio R., Deye N., Lukaszewicz A.C. Impaired plasma B-type natriuretic peptide clearance in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2542–2546. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318183f067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao L., Jiang D., Wen X.S. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in patients with severe COVID-19. Respir Res. 2020;21:83. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01352-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pranata R., Huang I., Lukito A.A., Raharjo S.B. Elevated N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide is associated with increased mortality in patients with COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med. 2020;96:387–391. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.