Abstract

Background

Accurate lymph node (LN) staging has considerably prognostic and therapeutic value in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). The purpose of this study is to evaluate the feasibility of applying carbon nanoparticles (CNPs) to track LN metastases in CRC.

Methods

Two researchers independently screened publications in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane and Ovid MEDLINE databases. The keywords were (carbon nanoparticles OR activated carbon nanoparticles) AND (colon cancer OR rectal cancer OR colorectal cancer). Titles and abstracts of the articles were meticulously read to rule out potential publications. Next, full texts of the ultimately obtained eligible publications were retrieved and analyzed in detail.

Results

The search produced 268 publications, and 140 abstracts were identified after a bibliographic review. Finally, 20 studies relevant to our subject were obtained; however, only 14 papers met our inclusion criteria and were included for final review. All studies included have compared the control group with carbon nanoparticles group (control group, defined as nontattooed group; and carbon nanoparticles group, defined as administering carbon nanoparticles during surgery) for their efficacy in intraoperative detecting and positioning. After analysis, appreciably less amount of bleeding (3/5 trials), shorter operation time (2/4 trials), and shorter time to detect lesions and dissect LNs (2/2 trials) were revealed in CNPs group compared to control group. Thirteen studies have recorded the numbers of the harvested LNs in both groups; meanwhile, CNPs group shows superiority to control group in LN retrieval as well (11/13 trials), which also could effectively aid in locating and harvesting more LNs with diameter below 5 mm.

Conclusion

The tracing technique for CNPs is a safe and useful strategy both in localizing tumor and tracing LNs in CRC surgery. But there is still a need for more randomized controlled trials to further establish its contribution to patient survival.

Keywords: carbon nanoparticles, colorectal cancer, lymph nodes, trace, tumor location

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies across all genders.1 Headway in the treatment strategies, including improved surgical techniques, evolvements in chemotherapy, advances in radiotherapy, and the development of targeted therapies, are tremendously valuable in survival gains for these patients in recent decades.2 However, complete surgical resection remains the cornerstone of curative treatment to manage resectable tumors.3 Lymphadenectomy, an important part of radical surgery, is one of the key factors influencing the prognosis, not only to eliminate possible lymphatic metastasis of cancer cells,4,5 but also to assist in accurate lymph node (LN) staging.

Therefore, accurate evaluation of metastatic LNs constitutes an essential role in predicting the prognosis of CRC patients receiving radical resection.6 Inadequate retrieval of LNs would predispose the patients at risk of understaging the disease, causing lifesaving adjuvant treatment to be delayed. Multiple reports have illustrated that inadequate lymph node evaluation is positively correlated with shorter overall survival in CRC patients with or without metastatic LNs.7–10 Adequate lymph nodes are not only critical for accurate LN staging, but also have significance in choosing an adjuvant treatment program after radical resection as well as in predicting the prognosis after disease management.11–13 Even though different requirement of the minimum number of LNs harvested have been reported in previous studies, pathologists still should try their best to obtain as many LNs as they can.12 Lymph nodes, however, were often not harvested sufficiently in many patients diagnosed with CRC.14 Therefore, tools or techniques reserved for harvesting adequate LNs and accurate LN staging were urgently demanded.

The rapidly emerging research of nanotechnology provides exciting new possibilities for developing more and more new nanomaterials for practical use.15,16 CNPs, one of the most representative nanomaterials, has been widely used for drug and gene delivery,17,18 biosensors,19 molecular imaging age,20 and LN tracing in various surgeries.21–23 CNPs can be absorbed selectively by lymphatics and stain the LNs black after being injected into the submucosal layer around the tumor, and the CNPs would not permeate into the blood capillaries due to different permeability between lymph and blood systems,24 where CNPs are too large to enter blood circulation, thus leading to few toxic side effects.25 Therefore, this method has been widely approved by some countries in clinical application.

Several clinical studies have demonstrated CNPs could be helpful in accurately staging LNs when performing lymphadenectomy,23,26–36 resulting in reduced operation time28,36 as well as less intraoperative blood loss.24,28,36 Nevertheless, some contradictory studies, which showed that CNPs did not have much advantage either in retrieving LNs or locating tumors, were still reported.24,37 Therefore, a systematic review was performed to comprehensively evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the CNPs in assisting in tracing of LNs and localization of CRC from currently available data.

Materials and Methods

This study systematically reviewed the current literature which had evaluated the safety and effectiveness of CNPs suspension in tracking LNs and tumor location of CRC. With respect to LN retrieval, total and mean number of LNs, percentages of metastatic lymph nodes and those patients with metastatic LNs, percentages of small LNs and those with insufficient dissected LNs (<12) were evaluated. Regarding tumor location, time to locate the primary tumor, total operation time and volume of bleeding were all evaluated. Postoperative complications and other outcomes related to tumor and LNs resection were assessed as well, including time to harvest LNs and percentages of stained LNs, metastatic LNs and small LNs. This systematic review was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention.38 The protocol for this systematic review is available in PROSPERO (CRD42020192248).

Search Strategy

A search strategy was performed, including the terms below: (carbon nanoparticles OR activated carbon nanoparticles) AND (colon cancer OR rectal cancer OR colorectal cancer). Electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane and Ovid MEDLINE were searched from inception to May 30, 2020. A bibliographic review was performed to ensure capture of all relevant articles. There were no restrictions on study design, year, language, or country published.

Eligibility Criteria

The following criteria were used to select studies: (1) full paper or conference abstract available; (2) studies that compared carbon nanoparticles with control groups in locating tumors and (or) tracing LNs in colorectal cancer; (3) studies sorted as RCT, cohort study, or retrospective study. Studies with duplicate data or data not relevant to CNPs were excluded.

Data Extraction

Two Investigators independently extracted data according to the predefined form, including the following information: author, year published, country, study type, sample size, age, gender, tumor location, nanoparticle size, injection time, injection dose and site, tumor diameter, operation time, time to locate the primary tumor, amount of bleeding, total and mean numbers of the dissected LNs, numbers of harvested metastatic LNs, patients with positive LNs, dissected LNs <12 and percentage of LNs smaller than 5 mm in diameter, dyed LNs, dyed metastatic LNs, dyed small metastatic LNs and rate of postoperation complications.

Results

Studies Retrieved and Characteristics

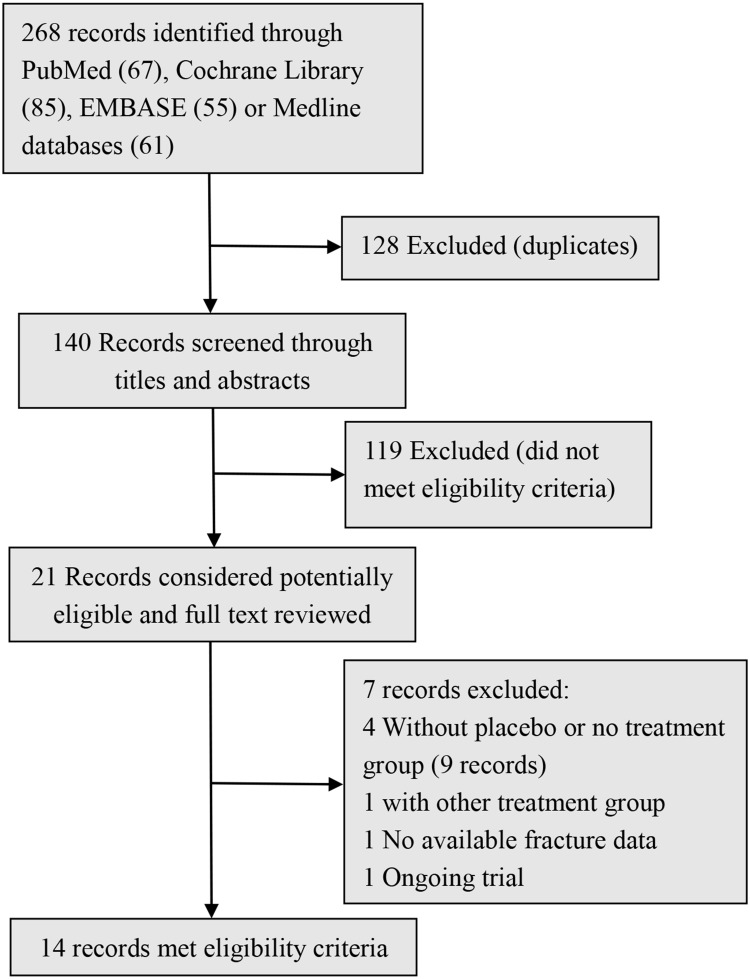

By searching, 268 potential relevant records were identified. After screening the titles and abstracts,140 records were originally included, and 21 records were subsequently acquired after full texts being read, 14 papers eventually met the inclusion criteria and were included for final analysis (Figure 1). These studies include eight randomized controlled trials, three case–control studies, and three retrospective studies, involving a total of 1618 participants (887 patients in CNPs group and 731 in control groups). The baseline information for the CNPs group and the control group were comparable in these studies (Table 1). All the patients were confirmed pre-operationally by endoscopic biopsy or other methods. In this review, we included all these patients diagnosed as carcinoma of colon or rectum, and tumor location in these studies were listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart.

Table 1.

The Basic Information for the Two Groups in All These Studies

| Author | Year | Country | Study | Sample Size | Age (years) | Gender (M/F) | Tumor Location | Tumor Diameter(cm) | Degree of Differentiation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (CNPs/Cons) |

CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | ||||

| Cai26 | 2007 | China | RCT | 40 (20/20) | 57.5±11.5 | 64.9± 7.4 |

14/6 | 13/7 | Colon (13); rectum (7) | Colon (9); rectum (11) | 5.0 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 1.1 |

1*(7); 2*(10); 3* (3) | 1 (8); 2 (11); 3 (1) |

| Cipe37 | 2016 | Turkey | RCT | 40 20/20) | 61.0± 12.1 |

61.1± 11.4 |

3/17 | 5/15 | Rectum (20) | Rectum (20) | 4.2± 2.2 |

4.5± 2.0 |

NA | NA |

| Wang22 | 2015 | China | R | 152 (45/107) | 53.1± 12.0 |

54.0± 11.6 |

34/11 | 79/28 | Rectum (45) | Rectum (107) | NA | NA | 1~2 (34); 3 (11) | 1~2 (87); 3 (20) |

| Yang27 | 2015 | China | RCT | 65 (34/31) | 59.2± 8.9 |

61.5± 6.2 |

22/12 | 20/11 | Colon (22); Rectum (12) | Colon (21); rectum (10) | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 2.1 |

1 (8); 2 (15); 3 (11) | 1 (5); 2 (14); 3 (12) |

| Wang28 | 2016 | China | CC | 54 (27/27) | 62.8±11.3 | 64.6± 10.1 |

19/8 | 14/13 | Colon (22); Rectum (5) | Colon (22); rectum (5) | 4.3±1.7 | 4.3± 1.5 |

NA | NA |

| Zhang29 | 2016 | China | CC | 87 (35/52) | 60.0±10.7 | 58.9± 9.4 |

16/19 | 24/28 | Rectum (35) | Rectum (52) | 4.9±2.0 | 4.6± 2.3 |

1 (2); 2 (29); 3 (4) | 1 (2); 2 (29); 3 (4) |

| Zhao30 | 2017 | China | RCT | 70 (35/35) | NA | NA | 18/17 | 19/16 | Rectum (35) | Rectum (35) | NA | NA | 1 (20); 2~3 (15) |

1 (23); 2–3 (12) |

| Wang39 | 2017 | China | R | 470 (344/126) | 58.6± 12.4 |

59.1± 12.2 |

183/161 | 78/48 | Colorectum (244) | Colorectum (126) | 4.0± 1.7 |

4.2± 1.6 |

1 (15); 2 (235); 3 (94) | 1 (6); 2 (82); 3 (38) |

| Pan31 | 2018 | China | CC | 99 (52/47) | NA | NA | NA | NA | Colon (52) | Colon (47) | NA | NA | 1~2 (34); 3 (18) | 1~2 (32); 3 (15) |

| Sun32 | 2018 | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 53.2± 5.3 |

53.0± 5.4 |

23/17 | 22/18 | Colon (35); rectum (5) | Colon (36); rectum (4) | 3.6± 2.2 |

3.6± 2.2 |

NA | NA |

| Li33 | 2019 | China | CC | 66 (33/33) | 57.2± 9.4 |

57.8±9.7 | 26/7 | 26/7 | Rectum (33) | Rectum (33) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tang34 | 2019 | China | RCT | 79 (40/39) | 57.9±11.8 | 59.3±10.7 | 26/14 | 22/17 | Colon (40) | Colon (39) | 5.1±2.1 | 5.4± 1.8 |

1 (5); 2 (32); 3 (3) | 1 (7); 2 (28); 3 (4) |

| Wang35 | 2020 | China | RCT | 239 (123/116) | 59.0± 9.8 |

56.8±10.8 | 79/44 | 67/49 | Colorectum (133) | Colorectum (116) | NA | NA | 1 (3); 2(93); 3 (27) | 1 (3); 2 (87); 3 (26) |

| Wang36 | 2020 | China | RCT | 77 (39/38) | 56.2±10.1 | 59.2±8.0 | 27/12 | 25/13 | Colon (15); rectum (24) | Colon (16); rectum (22) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Notes: “1” represents well differentiation; “2” represents moderate differentiation; “3” represents poor differentiation.

Abbreviations: CNPs, carbbon nanoparticles; Cons, control groups; RCT, random control trial; R, retrospective study; CC, case–control study; M, male; FM, female; NA, not available.

After analysis, most of the studies in the CNPs group validated that primary tumors and LNs could be tattooed by injecting 0.5–1mL of CNPs suspension into the submucosal layer around the lesions 10 min to seven days before the operation (Table 2). Two studies underwent submucosal injection surrounding the tumor intraoperatively.34,39 In another study assessing CNPs’ feasibility in advanced CRC, the CNPs detection efficacy was evaluated 8 weeks after chemoradiotherapy (about 14 weeks before surgery).36 Moreover, there was also study indicated that the time of injection had no significantly relationship with the efficacy of the method.28

Table 2.

Injection Information

| Author | Nanoparticle Size | Injection Time | Injection Dose and Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cai26 | 150 nm | 30 min before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), 4 quadrant around the tumor |

| Cipe37 | 150 nm | 1 day before surgery | 1 mL, 4-quadrant around the tumor |

| Wang22 | 150 nm | 1 day before surgery | 0.5 mL (25 mg), 3 quadrant around the tumor |

| Yang27 | 150 nm | 10 min before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), 4–6 quadrant around the tumor |

| Wang28 | 150 nm | 3–7 days before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), 4 quadrant around the tumor |

| Zhang29 | 150 nm | 30 min before the surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), around the tumor |

| Zhao30 | 150 nm | 15 min before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), 4–5 quadrant around the tumor |

| Wang39 | 150 nm | Intraoperation | 1 mL (50 mg), 4–6 quadrant around the tumor. |

| Pan31 | 150 nm | 1 day before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), 4 quadrant around the tumor |

| Sun32 | 150 nm | 1 day before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), 4 quadrant around the tumor |

| Li33 | 150 nm | 1 day before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), around the tumor |

| Tang34 | 150 nm | Intraoperation | 1 mL (50 mg), 2–4 quadrant around the tumor |

| Wang35 | 150 nm | 1 day before surgery | 1 mL (50 mg), around the tumor |

| Wang36 | 150 nm | 14 weeks before surgery | 0.5 mL (25 mg), 4 quadrant around the tumor |

Note: CNPS, with or without being dissolved in appropriate physiological saline, injected into the submucosal layer around the tumor.

Whether these patients, with or without preoperation adjuvant chemotherapy, should receive laparoscopic or open radical operation was based on the clinical guidelines and surgeons’ preference. No significant differences in tumor diameters, T-stage, degree of differentiation and other baseline characteristics were noted between CNPs and control groups across all the studies.

LN Retrieval

Thirteen studies had reported total and (or) average number of dissected LNs in the CNPs group and the control group, respectively (Table 3). Eleven of 13 studies showed that the total (and /or) mean number of detected LNs per patient was significantly higher in the CNPs group than in the control group,23,26–36 illuminating the superiority of CNPs in tracing LNs. Seven studies recorded the numbers of harvested metastatic LNs,26–28,30–34 wherein two studies found more metastatic LNs in CNPs group, while four studies showed no significant difference between the two groups. Seven studies recorded the patients with metastatic LNs,23,26,28,31–34 three studies detected more LN-positive patients in the CNPs group than in the control group, while four studies showed no significant difference. Six studies had recorded and compared the ratio of patients whose detected LNs were less than 12,23,26,28,30,32,35 where four of these studies reported a lower ratio of <12 LNs in the CNPs group,23,26,32,35 while another two studies showed no significant difference.28,30

Table 3.

Information About the Lymph Node Retrieval

| Author | LNs (Total) | LNs (Mean ±SD) | MLNs | Patients with MLN | LNs <12 | LNs ≤5 mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | |

| Cai26 | 535 | 225 | 26.8±8.4 | 12.2±3.2 | 50 (9.3%) | 32 (14.2%) | 13 (65%) | 11 (55%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (50%) | NA | NA |

| Cipe37 | 403 | 451 | 20.2±8.7 | 22.6±9.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang22 | 949 | 856 | 21.1±9.6 | 8.0±4.6 | 58 (6.1%) | NA | 16 (35.6%) | 21 (19.6%) | 5 (11.1%) | 84 (78.5%) | 615 (64.8%) | NA |

| Yang27 | 725 | 725 | 22.3±4.2 | 15.4±3.5 | 179 (24.7%) | 179 (20.5%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 33 (4.6%) | 10 (2.0%) |

| Wang28 | 346 | 242 | 14.4±3.3 | 9.0±2.9 | NA | NA | 12 (44.4%) | 7 (25.9%) | 8 (29.6%) | 17 (63.0%) | NA | NA |

| Zhang29 | 987 | 1180 | 28.2±9.4 | 22.7±7.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 354 (35.9%) | 234 (19.8%) |

| Zhao30 | 641 | 464 | 18.3±6.1 | 13.3±1.9 | 114 (17.8%) | 69 (14.8%) | NA | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (14.3%) | 142 (22.2%) | 37 (8.0%) |

| Wang39 | 3143 | 1120 | 9.1±6.3 | 8.9±6.1 | 574 (18.3%) | 166 (14.8%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pan31 | 1088 | 825 | 20.9 ± 0.7 | 17.6±0.9 | 72 (6.6%) | 43 (5.2%) | 27 (51.9%) | 14 (29.8%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sun32 | 434 | 340 | 10.9 | 8.5 | NA | NA | 8 (20%) | 9 (22.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (32.5%) | 137 (31.6%) | 56 (16.5%) |

| Li33 | 794 | 535 | 24.1±13.2 | 16.2±9.1 | NA | NA | 2 (6.06%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tang34 | 1252 | 854 | 31.3±8.1 | 21.9±5.3 | 156 (20.4%) | 82 (9.6%) | 15 (37.5%) | 6 (15.4%) | NA | NA | 476 (38.0%) | 160 (18.7%) |

| Wang35 | 774 | 696 | 19.8±6.4 | 17.4±7.2 | 118 (15.2%) | 193 (27.7%) | NA | NA | 5 (4.1%) | 17 (14.7%) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: CNPs, carbon nanoparticles; Cons, control groups; LNs, lymph nodes; MLNs, metastatic lymph nodes; NA, not available.

The mean number of LNs with their greatest diameters less than 5 mm were also evaluated in six studies,26,27,29,30,32,34 all the studies showed that CNPs assisted lymph node retrievals were beneficial to harvest more small LNs (less than 5 mm in diameter). Two studies had calculated the percentages of stained LNs in the total lymph (84.8% and 56.8%) and the stained metastatic LNs in total metastatic LNs (77.6% and 65.9%),23,27 where one study had reported the stained small LNs (75.9%). Moreover, two studies found the numbers of metastatic LNs with their greatest dimension less than 5 mm were different (31.6% and 63.8%), of note, most of these metastatic small LNs were stained black (89.2% and 75.9%).23,32

Tumor Location

Four studies had reported the operation time,39 however, only one study delineated CNPs could significantly decrease the operation time36 (Table 4). There were also studies that showed that CNPs could be helpful in rapid detection of lesions28,36 and harvest lymph nodes23,31 during surgery, thus could substantially diminishing the time cost for surgeons and pathologists. In addition, five studies had recorded the bleeding volume during the surgery,28,33,36,37,39 three of them demonstrated the blood loss during operation was less in the CNPs group than in the control group.28,36,39 Besides, one study had described a longer distance between the tumor and the circumferential resection margin in the CNPs group.29 One study illustrated the protective ileostomy rates were lower in the CNPs group, however, the differences reached no statistical significance.37

Table 4.

Surgical Outcomes

| Author | Operation Time (min) | Time to Locate Tumors (min) | Amount of Bleeding (mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | |

| Cipe37 | 182.3±58.1 | 191.8±52.8 | NA | NA | 97.8±60.9 | 128.0±112.7 |

| Wang28 | 151.2±30.7 | 170.3±33.1 | NA | NA | 125.0±29.5 | 147.5±34.4 |

| Wang39 | 115.7±1.0 | 123.3±41.7 | 2.71±2.13 | 6.91±5.16 | 50.7±28.1 | 63.7±49.4 |

| Li33 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 52.9±32.1 | 55.3±42.6 |

| Wang36 | 155.7±44.5 | 177.2±30.2 | 3.4±1.4 | 11.8±3.4 | 101.3±36.7 | 120.2±38.2 |

Abbreviations: CNPs, carbon nanoparticles; Cons, control groups; mins, minutes; NA, not available.

Complications

Among all reported research, no patients in the CNPs group experienced adverse effects by injection of carbon nanoparticle suspension. While six studies documented some surgically relevant complications (Table 5).26,28,33,34,37,39 No significant differences in blood loss, postoperative hospital length of stay, rehospitalization, reoperation and motility were found between the two groups. Furthermore, no obvious difference was reported regarding postoperative complications, including anastomotic leakage, anastomotic hemorrhage, ileus, lymphorrhagia, perianal abscess, pneumonia, infection, intestinal obstruction and some other special complications.

Table 5.

Information About the Postoperative Complications

| Author | Complications (Rate) | Complications (Cases) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNPs | Cons | CNPs | Cons | |

| Cai26 | 2 (10%) | 2 (10%) | Bleeding (1); fistula (1) | Fistula (2) |

| Cipe37 | 3 (15%) | 4 (20%) | Stoma opening (6); mortality (1); rehospitalization (1); anastomose leakage (1); | Stoma opening (4); rehospitalization (2) |

| Wang28 | 3 (11.1%) | 3 (11.1%) | Bleeding (1); anastomotic leakage (1); intestinal obstruction (1) | Bleeding (1); infection (1); anastomotic leakage (1) |

| Wang39 | 69 (20.1%) | 24 (19.1%) | Bleeding (1); anastomotic stoma fistula (13); postoperative fever (6); wound infection (10); stoma infection (8); gastric retention (7); abnormal abdominal mass (2); stomach ache (16) | Anastomotic stoma fistula (2); postoperative fever (3); wound infection (2); stoma infection (2); gastric retention (2); stomach ache (10) |

| Li33 | 3 (9.0%) | 5 (15.2%) | Bleeding (1); lymphorrhagia (1); anastomotic leakage (1) | Bleeding (1); anastomotic leakage (1); ileus (1); perianal abscess (1); pneumonia (1) |

| Tang34 | 5 (12.5) | 1 (2.6%) | Wound infection (3); intra-abdominal infection (1); anastomotic leakage (1) | Wound infection (1) |

Abbreviations: CNPs, carbon nanoparticles; Cons, control groups.

Discussion

Theoretically, an optimal size of lymph node tracer should range between 50 and 200 nm, which would be small enough to enter into the lymphatic capillaries (diameter of 150–500 nm) and travel rapidly to the LNs, while simultaneously being large enough to remain in the sentinel nodes long enough for staining (by macrophage phagocytosis).40 Carbon nanoparticles, with an average diameter of 150 nm, were the most commonly used agent when tracing lymph nodes and locating tumors in CRC surgery, and these nanoparticles could be accumulated in the LNs long enough for subsequent identification during surgery. Besides, due to the means of administration (injection around tumors), together with their strong affinity to lymphatic systems, CNPs could mainly be deposited in LNs, while not entering into the cardiovascular system, thus, to some extent, exempting the potential toxic effect to cardiovascular, respiratory, and other systems (or organs).41,42 And this could explain why there were no significant differences in the prevalence of postoperative complications, suggesting CNPs are a safe agent in CRC surgery.

Another critical issue in LN identification is injection dose.43 Low dose of CNPs may be insufficient to dye the LNs, yet an overdose may cause other concerns. Previous clinical experiences have demonstrated that 0.5 or 1 mL (25 or 50 mg) of CNPs suspension, with or without being dissolved in appropriate physiological saline, was sufficient and recommended for identification of LNs. The dose of CNPs varies as application situations change,44 and timing of the application differs as well. In most studies, CNPs were injected one day before surgery (listed in Table 2). Some studies evidenced that more LNs were stained black as time passed,43 however, the best time to administrate CNPs needs to be further investigated.

Over past years, several techniques such as Indian ink and indocyanine green (ICG) have been utilized for tattooing tumors and LNs, unfortunately, they all have drawbacks, like inevitable adverse event, short imaging time, and even having certain interference with the visual field of operation.35 Intriguingly, as the development and evolvement of nanotechnology in recent years,45,46 biological application of nanoparticles has increased rapidly, thus making CNPs suspension used for lymph node tracing feasible.28

In clinic, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy could compellingly reduce detected LNs,47 a number of other patient- and tumor-related factors also play some roles in LNs yielding and assessment, such as the patient’s gender, age, tumor grade, surgical type, body mass index, and so on.48–50 Thereby, it would be regarded to have high risk factor if the number of LNs harvested per specimen were fewer than 12, according to the guideline of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).14,51,52 Other studies also claimed that more LNs are needed for staging, decision making, and prognosis predicting.53,54 Besides, the proportion of the number of involved LNs upon the examined LNs—defined as metastatic LN ratio (mLNR)—has also been considered as a prognostic parameter in CRC, and high mLNR was significantly correlated with worse survival.55–58 Despite different minimum required numbers of LNs being reported in previous studies, pathologists still should try their best to obtain as many LNs as they can. Unluckily, it is often possible that adequate LNs are not adequately harvested in many patients diagnosed with CRC.59 In this review, we found that most of the studies (84.6%) had proven that CNPs can assist in harvesting more LNs than traditional visual and tactile methods. CNPs are significantly beneficial to detect more LNs (especially small LNs) and for accurate LN staging. Strikingly, four of six studies reported a notably lower ratio of patients whose detected LNs were less than 12 in the CNPs group.

A study showed that the maximum diameter (less than or more than 5 mm in diameter) of the positive LNs was an independent indicator of prognosis, while there was no significant difference in overall survival rate and disease-free survival rate between them.59 Therefore, increased number of the dissected small LNs (<5mm in diameter) might make some achievements in accurate staging and prognosis prediction. Of note, LNs are easy to be overlooked by traditional methods if their diameters are less than 5 mm, particularly when some of these small LNs are metastatic and tumors are at high risk of understaging. In this review, all six studies included have proved that CNPs had merits in assisting in harvesting significantly more small LNs than the control group,26,27,29,30,32,34 suggesting that the preoperative SLN detection with CNPs in CRC patients can evaluate the LN's status, guide the treatment and improve the prognosis.32 Although there is one study that demonstrated no significant differences in survival or recurrence between the two groups after a three-year follow-up,39 more multicenter randomized controlled trails (such as NCT03550001) are required to explore the long-term clinical results.

Accurate tumor localization is of vital importance in CRC management as well, especially for patients with early-stage cancer or having previous resected tumors.60 The demand for correctly localizing a lesion has increased as endoscopic operations soar in recent years, however, obstacles in precisely palpating the pathological colon during surgical intervention makes locating the tumor troublesome, increasing the difficulty of resection. Therefore, endoscopically tattooing adjacent tissue of the tumor can promote precise tumor recognition to ensure a more precise, minimally invasive, colorectal resection. Due to these merits, endoscopic tattooing is considered to be the gold standard for tumor localization prior to undertaking minimally invasive surgery.61,62 More accurate localization may be associated with measurably shorter operation time,28,36 less blood loss,28,36,39 more accurate resection,36,37 simpler method, and greater practicality in the CNPs group compared to the control group.28

Interestingly, some studies illustrated that the overall time expenditure in the CNPs group was not greatly increased, or even reduced, when more LNs needed to be dissected.31,39 Furthermore, the mean operation time in the CNPs group was also reduced compared to the control group as reported in some studies.28,36 Thereby, these findings have validated the superiority of CNP staining in examining LNs (Table 6). Meanwhile, some challenges also emerge when using CNPs. Firstly, technical difficulties do exist when CNPs are injected into the submucosal layer around the tumor endoscopically. Given this, saline injection to construct a submucosal uplift prior to administering CNPs might be a feasible solution.35 Secondly, leakage during injection could also perturb the resection of tumors, even causing other undesirable adverse effects. Thirdly, CNPs are a nonspecific lymph node tracer, which is incapable of discriminating the metastatic LNs from negative LNs. Besides, more harvested LNs denote more pathologic work, which would be a heavy burden for pathologists.

Table 6.

The Merits of CNPs Compared with Control Group

| Terms | CNPs | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Retrieved more LNs | Yes | No |

| Retrived more MLNs | Yes | No |

| Retrieved more LNs in metastatic patients | Yes | No |

| Detected LNs <12 | Less | More |

| Retrieved more small LNs | Yes | No |

| Operation time | Shorter | Longer |

| Bleeding during sugery | Less | More |

| Rapid detection of lesions | Yes | No |

| Precise dissection | Yes | No |

| Complications | No differences | |

| Improved survival | Unknown | |

Abbreviations: CNPs, carbon nanoparticles groups; Cons, control groups; LNs, lymph nodes; MLNs, metastatic lymph nodes.

Some limitations exist in this work. First, the included studies are not all randomized controlled trials, in which cohort studies and retrospective studies were all collectively included; second, most of the studies have very limited samples; third, the patients in this review are those with colon cancers and rectal cancers; fourth, the long-term observations of the clinical effects of CNPs in CRC patients are not confirmed in majority of the studies. However, our review also has some strengths, we have extensively incorporated and analyzed all relevant studies with respect to the CNPs application and their results, which indicate our review is a comprehensive study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, tattooing with CNPs in CRC surgery is safe and beneficial in both tumor localization and LN tracing, which shows the importance of CNPs in reducing the difficulty and operation time in CRC surgery should be emphasized. Therefore, the value of CNPs in surgical treatment of cancer should be recognized and its application might be promoted and expanded in the future. However, the exact merits and mechanisms with respect to prolonging survival are not illuminated and more randomized controlled trials are still needed to clarify and elucidate its underlying mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31900970), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2019YJ0052) and 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC18018).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145–164. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM,Wallace MB Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1467–1480. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32319-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechera R, Schuster T, Rosenberg R, Speich B. Lymph node yield after rectal resection in patients treated with neoadjuvant radiation for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprenger T, Rothe H, Conradi LC, et al. Stage-dependent frequency of lymph node metastases in patients with rectal carcinoma after preoperative chemoradiation: results from the CAO/ARO/AIO-94 trial and from a comparative prospective evaluation with extensive pathological workup. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(5):377–385. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resch A, Langner C. Lymph node staging in colorectal cancer: old controversies and recent advances. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(46):8515–8526. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanemitsu Y, Komori K, Ishiguro S, Watanabe T, Sugihara K. The relationship of lymph node evaluation and colorectal cancer survival after curative resection: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(7):2169–2177. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi HK, Law WL, Poon JT. The optimal number of lymph nodes examined in stage II colorectal cancer and its impact of on outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:267. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Kubota K. Insufficient lymph node dissection is an independent risk factor for postoperative cancer death in patients undergoing surgery for stage II colorectal cancer. Eur Surg Res. 2011;46(2):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000321318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons HM, Tuttle TM, Kuntz KM, Begun JW, McGovern PM, Virnig BA. Association between lymph node evaluation for colon cancer and node positivity over the past 20 years. JAMA. 2011;306(10):1089–1097. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lykke J, Roikjaer O, Jess P; Danish Colorectal Cancer Group. The relation between lymph node status and survival in Stage I-III colon cancer: results from a prospective nationwide cohort study. Colorectal Dis 2013;15(5):559–565. doi: 10.1111/codi.12059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edge SB, Compton CC. TheAmerican Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris EJ, Maughan NJ, Forman D, Quirke P. Identifying stage III colorectal cancer patients: the influence of the patient, surgeon, and pathologist. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2573–2579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shia J, Wang H, Nash GM, Klimstra DS. Lymph node staging in colorectal cancer: revisiting the benchmark of at least 12 lymph nodes in R0 resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(3):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei X, Zhang B, Tang J, Liu B, Lai W, Tang D. Sandwich-type immunosensors and immunoassays exploiting nanostructure labels: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;758:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shu J, Tang D. Recent advances in photoelectrochemical sensing: from engineered photoactive materials to sensing devices and detection modes. Anal Chem. 2020;92(1):363–377. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jafar END, Omidi Y, Losic D. Carbon nanotubes as an advanced drug and gene delivery nanosystem. Curr Nanoence. 2011;7(3):297–314. doi: 10.2174/157341311795542444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kokubun K, Matsumura S, Yudasaka M, Iijima S, Shiba K. Immobilization of a carbon nanomaterial-based localized drug-release system using a bispecific material-binding peptide. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:1643–1652. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S155913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbon dots/g-C3N4 nanoheterostructures-based signal-generation tags for photoelectrochemical immunoassay of cancer biomarkers coupling with copper nanoclusters. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(44):38336–38343. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b13272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartman KB, Wilson LJ. Carbon nanostructures as a new high-performance platform for MR molecular imaging. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;620:74–84. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76713-0_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan J, Zheng X, Liu Z, et al. A multicenter study of using carbon nanoparticles to show sentinel lymph nodes in early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(4):1294–1300. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4358-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Huang Y, Yang C, et al. Application of a carbon nanoparticle suspension for sentinel lymph node mapping in patients with early breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1414-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Deng H, Chen H, et al. Preoperative submucosal injection of carbon nanoparticles improves lymph node staging accuracy in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(5):923–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.07.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu CL, Yang TL, Chen BF. Sentinel lymph node mapping with emulsion of activated carbon particles in patients with pre-mastectomy diagnosis of intraductal carcinoma of the breast. J Chin Med Assoc. 2003;66(7):406–410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figarol A, Pourchez J, Boudard D, et al. In vitro toxicity of carbon nanotubes, nano-graphite and carbon black, similar impacts of acid functionalization. Toxicol in Vitro. 2015;30(1):476–485. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai HK, He HF, Tian W, Zhou MQ, Hu Y, Deng YC. Colorectal cancer lymph node staining by activated carbon nanoparticles suspension in vivo or methylene blue in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(42):6148–6154. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang B, Li Y, Wen R, et al. Application of carbon nanoparticles labeled lymph node staining in curative laparoscopic resection for colorectal carcinoma. Chin J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;18(6):549–552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Chen E, Cai Y, et al. Preoperative endoscopic localization of colorectal cancer and tracing LNs by using carbon nanoparticles in laparoscopy. World Surg Oncol J. 2016;14(1):231. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0987-1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang XM, Liang JW, Wang Z, Kou JT, Zhou ZX. Effect of preoperative injection of carbon nanoparticle suspension on the outcomes of selected patients with mid-low rectal cancer. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35:33. doi: 10.1186/s40880-016-0097-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y, Han G, Li J, et al. Technical advantages of nano carbon development combined with artery approach in lymph node sorting of rectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;20(6):680–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan L, Ye F, Liu JJ, Ba XQ, Sheng QS. A study of using carbon nanoparticles to improve LNs staging for laparoscopic-assisted radical right hemicolectomy in colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(8):1131–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, Zhang J. Assessment of lymph node metastasis in elderly patients with colorectal cancer by sentinel lymph node identification using carbon nanoparticles. J BUON. 2018;23(2):312–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li K, Chen D, Chen W, et al. A case-control study of using carbon nanoparticles to trace decision-making LNs around inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(3):904–910. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6384-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang L, Sun L, Zhao P, Kong D. Effect of activated carbon nanoparticles on lymph node harvest in patients with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(4):427–431. doi: 10.1111/codi.14538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang R, Mo S, Liu Q, et al. The safety and effectiveness of carbon nanoparticles suspension in tracking lymph node metastases of colorectal cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50(5):535–542. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaa011 505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R, Zhan HL, Li DZ, Li HT, Yu L, Wang W. Application of endoscopic tattooing with carbon nanoparticlet in the treatment for advanced colorectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;23(1):56–64. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0274.2020.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cipe G, Cengiz MB, Idiz UO, et al. The effects of preoperative endoscopic tattooing on distal surgical margin and ileostomy rates in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery: a prospective randomized study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26(4):301–303. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a R edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:Ed000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang LY, Li JH, Zhou X, Zheng QC, Cheng X. Clinical application of carbon nanoparticles in curative resection for colorectal carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:5585–5589. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S146627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cousins A, Thompson SK, Wedding AB, Thierry B. Clinical relevance of novel imaging technologies for sentinel lymph node identification and staging. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(2):269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Davidson DC, Castranova V, et al. Pulmonary effects of carbon nanomaterials. In: Chen Chunying, Haifang Wang editors. Biomedical Applications and Toxicology of Carbon Nanomaterials. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2016:163–194. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madannejad R, Shoaie N, Jahanpeyma F, Darvishi MH, Azimzadeh M, Javadi H. Toxicity of carbon-based nanomaterials: reviewing recent reports in medical and biological systems. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;307:206–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu X, Lin Q, Chen G, et al. Sentinel lymph node detection using carbon nanoparticles in patients with early breast cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, et al. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49(3):270–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan FA, Almohazey D, Alomari M, Almofty SA. Impact of nanoparticles on neuron biology: current research trends. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:2767–2776. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S165675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Estelrich J, Sánchez-Martín MJ, Busquets MA. Nanoparticles in magnetic resonance imaging: from simple to dual contrast agents. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:1727–1741. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S76501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rullier A, Laurent C, Capdepont M, et al. Lymph nodes after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal carcinoma: number, status, and impact on survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(1):45–50. 570 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180dc92ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarli L, Bader G, Iusco D, et al. Number of lymph nodes examined and prognosis of TNM stage II colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(2):272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou JF, Row D, Gonen M, Liu YH, Schrag D, Weiser MR. Clinical and pathologic factors that predict lymph node yield from surgical specimens in colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Cancer. 2010;116(11):2560–2570. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng SK, Lu CT, Pakneshan S, Leung M, Siu S, Lam AK. Harvest of lymph nodes in colorectal cancer depends on demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(1):19–22. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2927-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Compton CC, Greene FL. The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(6):295–308. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gravante G, Parker R, Elshaer M, et al. Lymph node retrieval for colorectal cancer: estimation of the minimum resection length to achieve at least 12 LNs for the pathological analysis. Int J Surg. 2016;25:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xingmao Z, Hongying W, Zhixiang ZX, Zheng W. Analysis on the correlation between number of lymph nodes examined and prognosis in patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):371. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0371-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cai Y, Cheng G, Lu X, Ju H, Zhu X. The re-evaluation of optimal lymph node yield in stage II right-sided colon cancer: is a minimum of 12 lymph nodes adequate? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35 595(4):623–631. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03483-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pyo JS, Shin YM, Kang DW. Prognostic implication of metastatic lymph node ratio in colorectal cancers: comparison depending on tumor location. J Clin Med. 2019;8(11):1812 doi:10.3390/jcm8111812 600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim YS, Kim JH, Yoon SM, et al. lymph node ratio as a prognostic factor in patients with stage III rectal cancer treated with total mesorectal excision followed by chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(3):796–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenberg R, Friederichs J, Schuster T, et al. Prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer is associated with lymph node ratio: a single-center analysis of 3,026 patients over a 25-year time period. Ann Surg. 2008;248(6):968–978. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190eddc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park IJ, Yu CS, Lim SB, et al. Ratio of metastatic LNs is more important for rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(11):3274–3281. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dejardin O, Ruault E, Jooste V, et al. Volume of surgical activity and lymph node evaluation for patients with colorectal cancer in France. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(3):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.10.003 615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeung JM, Maxwell-Armstrong C, Acheson AG. Colonic tattooing in laparoscopic surgery - making the mark? Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(5):527–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Conaghan PJ, Maxwell-Armstrong CA, Garrioch MV, Hong L, Acheson AG. Leaving a mark: the frequency and accuracy of tattooing prior to laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(10):1184–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beretvas RI, Ponsky J. Endoscopic marking: an adjunct to laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(10):1202–1203. doi: 10.1007/s004640000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]