Graphical abstract

Keywords: Allostery, Allosteric pluripotency, EPAC, cAMP, cGMP, Agonism, Antagonism, PKA, PKG

Abstract

Allosteric modulation provides an effective avenue for selective and potent enzyme inhibition. Here, we summarize and critically discuss recent advances on the mechanisms of allosteric partial agonists for three representative signalling enzymes activated by cyclic nucleotides: the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), the cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), and the exchange protein activated by cAMP (EPAC). The comparative analysis of partial agonism in PKA, PKG and EPAC reveals a common emerging theme, i.e. the sampling of distinct “mixed” conformational states, either within a single domain or between distinct domains. Here, we show how such “mixed” states play a crucial role in explaining the observed functional response, i.e. partial agonism and allosteric pluripotency, as well as in maximizing inhibition while minimizing potency losses. In addition, by combining Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and Ensemble Allosteric Modeling (EAM), we also show how to map the free-energy landscape of conformational ensembles containing “mixed” states. By discussing selected case studies, we illustrate how MD simulations and EAM complement NMR to quantitatively relate protein dynamics to function. The resulting NMR- and MD-based EAMs are anticipated to inform not only the design of new generations of highly selective allosteric inhibitors, but also the choice of multidrug combinations.

1. Introduction

Allostery is a ubiquitous mechanism adopted by macromolecules to respond to external stimuli. An allosteric perturbation typically induces structural and/or dynamical changes that regulate function. Allosteric stimuli include not only binding of small ligands or partner proteins, but also mutations and post-translational modifications. Allosteric sites are usually distant from the orthosteric sites, such as the enzyme substrate binding site, and are less conserved relative to the orthosteric sites due to lower evolutionary pressure [1], [2]. Hence, allosteric modulation is a promising approach for eliciting selective and potent enzyme inhibition. This realization has prompted a plethora of studies for understanding allosteric communication and networks [3], [4], [5], allosteric drug design [6], [7], [8], [9], as well as the mechanisms of allosteric inhibitors and partial agonists. The latter typically target the allosteric domains of enzymes such as kinases [10], [11], [12], guanine nucleotide exchange factors [13], [14], tyrosine kinases [15], [16], and proteases [17], [18], or protein–protein interfaces such as molecular chaperone-client interactions [19].

Considering that allosteric mechanisms are fundamentally dynamic in nature, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic methods serve as an excellent tool to map at atomic resolution the free energy landscape sampled by the conformational ensemble of dynamic allosteric domains. However, it is advisable to complement experimental methods with computational approaches to identify potential allosteric sites and refine hypotheses on rational design of allosteric drugs [20], [21]. For example, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations combined with coordination propensity (CP) analysis, which permits an assessment of the intrinsic flexibility of proteins and the changes associated with ligand binding, were used to identify residues that are distant from the catalytic site, yet highly correlated with the catalytic site [21]. Another computational method known as the structure-based statistical mechanical model of allostery (SBSMMA), which quantifies energetics and cooperativity of allosteric communication, provides predictions on novel allosteric sites [5], [20].

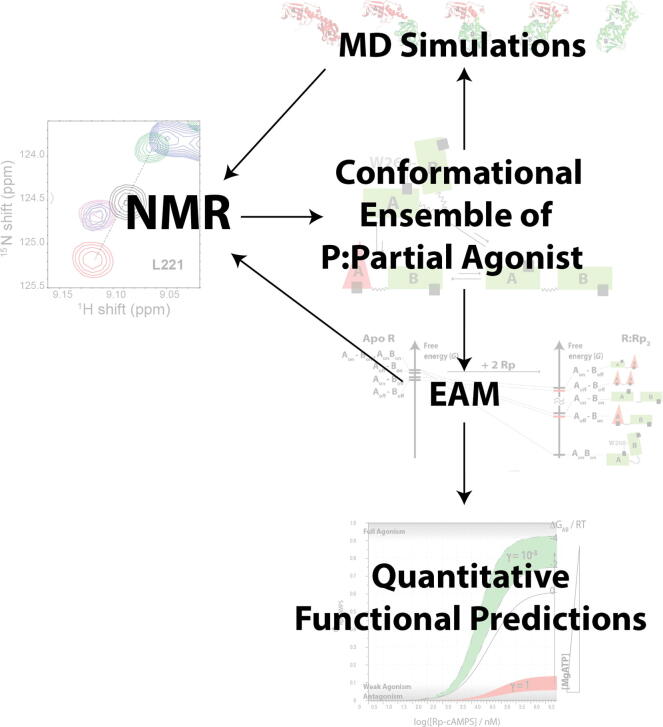

Allosteric modelling is also crucial in providing insights on observable allosteric phenomena. When allostery was initially conceptualized, the two leading allosteric models were the Monod-Wyman-Changeux’s (MWC) [22] and the Koshland-Nemethy-Filmer’s (KNF) [23], also known as the ‘symmetric’ and ‘sequential’ models, respectively. These two models explain allostery of multimeric proteins, where the subunits undergo conformational change between two major structural end states, i.e. the low-affinity and high-affinity forms. The main idea of the MWC model is the pre-existing conformational equilibrium that shifts with conservation of symmetry upon binding of a regulator or ligand [22]. On the other hand, the KNF model postulates that each subunit undergoes conformational change upon binding of the ligand (i.e. induced-fit), and that this propagates to adjacent subunits, thus changing the affinity of those binding sites, and hence giving rise to cooperativity [23]. However, these models cannot be applied to all allosteric systems, and do not provide explanations on how the allosteric modulation can occur without structural changes or how an allosteric switch could occur between agonism and antagonism upon binding to the same ligand. The ensemble allosteric model (EAM) successfully addresses these limitations by interpreting the dynamics of allostery in terms of thermodynamic ensembles of microstates. In the EAM, the populations of each microstate are modeled through normalized Boltzmann factors, which are in turn dictated by the free energies of conformational change within each (sub)domain, and of inter-(sub)domain interactions [10], [24], [25], [26], [27]. Knowledge of such populations enables the prediction of key observables, such as affinities and degrees of activation/inhibition. Here, we provide examples to illustrate how complementing NMR with Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and Ensemble Allosteric Modeling (EAM) provides unique insight on protein dynamics and their relation to function and allosteric regulation.

In the first part of the review, we will summarize and analyze recent findings on the mechanisms of partial agonists for representative allosteric signalling enzymes: the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), the cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), and the exchange protein activated by cAMP (EPAC) [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. The goal of this initial section is to reveal emerging trends, such as stabilization of novel “mixed” states that play essential roles in explaining the observed functional response. In the second part of the review, we will discuss how MD simulations and EAM play critical roles in complementing the NMR data, and leading to allosteric models that quantitatively and verifiably predict protein function.

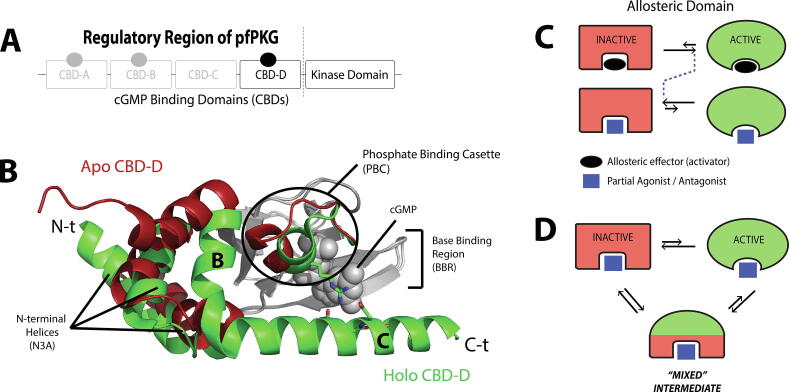

This review does not claim to be exhaustive, and we will focus primarily on illustrative cases from our own work on cyclic nucleotide monophosphate (cNMP)-binding domains (CBDs) [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. CBDs share a conserved fold architecture with a non-continuous α-subdomain and a continuous β-subdomain (Fig. 1A, B). The N-terminal helices are collectively referred to as the N3A, while the cNMP-phosphate binding cassette (PBC) is located within the β-subdomain (Fig. 1B). CBDs are prototypical conformational switches, and we will focus on CBDs that serve as the central controlling unit for closed-to-open transitions, which are common in the regulation of signaling pathways. Nevertheless, we refer the reader to other excellent reviews and articles for a more comprehensive assessment of the field [24], [33], [34], [35], [36], [3], [37], [38], [39], [40].

Fig. 1.

Inhibition by allosteric partial agonists through perturbation of conformational equilibria. (A) An example of domain organization in a cyclic-nucleotide activated enzyme, i.e. the cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) of Plasmodium falciparum. In this example, the regulatory and catalytic regions are in the same polypeptide chain, and thus the C-terminal cyclic-nucleotide binding domain (CBD) is directly linked to the catalytic region. (B) An example of the CBD structural architecture in the apo inactive state (red) and the holo active state (green). The grey region indicates the largely invariant β-subdomain. The N-terminal helices (N3A), the C-terminal helices (“B” and “C”), and the phosphate binding cassette (PBC) undergo significant structural changes upon binding to the cGMP effector. (C) When an allosteric domain equilibrates between inactive and active states, binding of its endogenous allosteric effector (activator) typically shifts the equilibrium to the active state. A partial agonist or antagonist can either shift the equilibrium towards the inactive state, or sample an ensemble of conformations where an additional “mixed” intermediate state is sampled, as shown in panel (D). The mixed nature of this intermediate is manifested in its ability to resemble more closely the active state in some regions, and the inactive state in other regions, as depicted by the green/red color pattern. The figure was originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry. Byun JA, Van K, Huang J, Henning P, Franz E, Akimoto M, et al. Mechanism of allosteric inhibition in the Plasmodium falciparum cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:8480–91. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2. Partial agonism in isolated allosteric domains reveals a common inhibitory mechanism where sampling of ‘mixed’ intermediate states maximizes inhibition while minimizing potency losses

Although allosteric signaling systems are often multi-domain proteins, here we will initially focus on a single allosteric domain, as this is the simplest case to start with, and it offers an essential ‘building block’ to understand more complex systems. In addition, it is often possible to identify a single domain that functions as the main ‘central controlling unit’ for the whole multi-domain protein, such as CBD-D of P. falciparum PKG in Fig. 1A. When a partial agonist binds and induces changes in a single domain, functional modulations arise from at least two possible scenarios: (1) a simple shift of a two-state inactive-active conformational equilibrium to the inactive state (Fig. 1C); or (2) a multi-state equilibrium sampling a distinct intermediate ‘mixed’ state that displays different degrees of resemblance to the inactive and active states in different regions of the domain (Fig. 1D).

Recent studies on the mechanisms of partial agonists that target the CBDs of allosterically regulated enzymes show an emerging trend, where partial agonism is best accounted for in terms of sampling multi-state equilibria with mixed intermediate states [11], [12], [13], [14]. A common feature shared by these mixed intermediate states is the differential allosteric response of the C-terminal helix and the PBC (Fig. 1B). The PBC directly interacts with the phosphate of the cNMP, while the C-terminal helix of the allosteric domain serves as a capping lid for the cNMP (Fig. 1B). In PKG and EPAC, the C-terminal helix also directly links the CBD to the catalytic domain or region. The mixed states (Fig. 1D) offer a simple but effective explanation for the mechanism of inhibition of these enzymes.

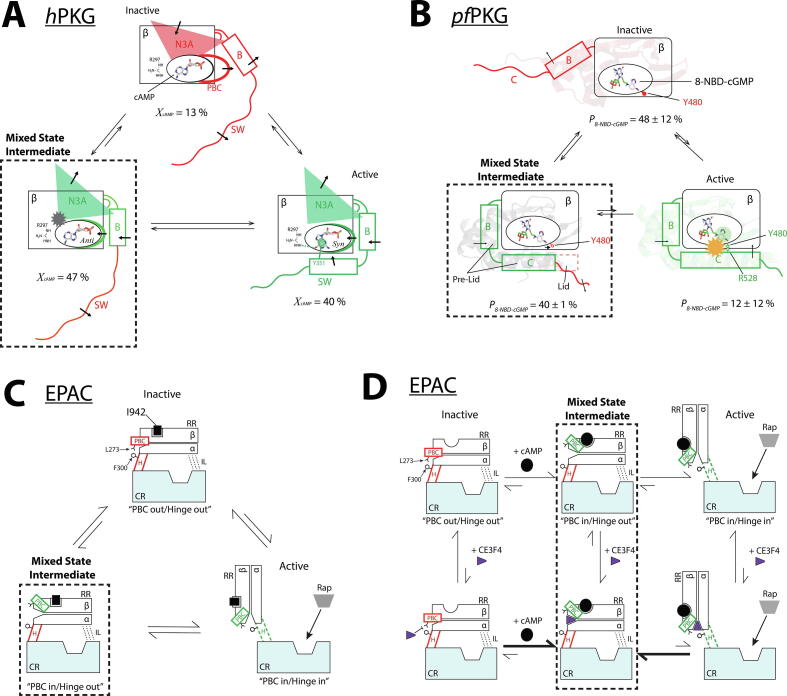

hPKG. One of the first cases in which mixed intermediates were reported to explain partial agonism in a CBD pertains to human cGMP-dependent protein kinase (hPKG) and cAMP [12]. hPKG includes two tandem CBDs (CBD-A and CBD-B) preceding the kinase domain [28], [41]. Although the CBD-B of hPKG preferentially binds cGMP relative to cAMP, the higher intracellular concentration of cAMP suggests that additional mechanisms promote selective cGMP-dependent activation of hPKG in conjunction with the cGMP-versus-cAMP affinity differential [28], [41], [42], [43]. For example, another difference that contributes to cGMP-versus-cAMP selective activation is that cAMP acts as a partial agonist for hPKG. To determine the mechanism of such partial agonism, NMR chemical shift projection analyses (CHESPA) and 15N relaxation measurements aimed at characterizing internal dynamics were utilized [12].

CHESPA revealed a non-uniform distribution of fractional activations indicative of cAMP-bound CBD-B sampling a three-state equilibrium among the inactive state, the active state, and a mixed intermediate state (Fig. 2A). In the inactive state, the N-terminal helices (N3A) are in the ‘in’ conformation, and the PBC and C-terminal helices are in the ‘out’ conformation and flexible, as confirmed by 15N relaxation measurements. The opposite is true for the active state. In the mixed intermediate state, the orientation of both the N3A and PBC resembles that of the active state, but the C-terminal helices are disengaged and more dynamic, similar to the inactive state (Fig. 2A; dashed box). This disengagement of the C-terminal helices, which directly link CBD-B to the catalytic domain, alters the relative positioning of the catalytic domain and CBD-B, and thus, the accessibility of the kinase substrates to the catalytic binding pocket. This allows the mixed state to preserve at least partial kinase inhibition, and provides a viable explanation as to why even if cAMP binds hPKG due to its high intracellular concentration, it leads to only minimal cross-activation of cGMP- and cAMP-dependent signalling pathways.

Fig. 2.

Sampling mixed intermediate states of isolated CBDs enables partial agonists to maximize inhibition without significantly compromising affinities. (A) CBD-B of human PKG bound to cAMP samples inactive and active conformers as well as an intermediate state (dashed box), where only its C-terminal switch helix (SW) is disengaged and dynamic [12]. The figure was reproduced with permission and was originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry. VanSchouwen B, Selvaratnam R, Giri R, Lorenz R, Herberg FW, Kim C, et al. Mechanism of cAMP Partial Agonism in Protein Kinase G (PKG). J. Biol. Chem. 2015; 290:28631–38641. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. (B) Plasmodium falciparum PKG bound to 8-NBD-cGMP. The mixed intermediate state (dashed box) features an engaged pre-lid region to promote inhibitor binding, but the C-terminal lid remains disengaged to ensure inhibition [11]. The figure was reproduced with permission and was originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry. Byun JA, Van K, Huang J, Henning P, Franz E, Akimoto M, et al. Mechanism of allosteric inhibition in the Plasmodium falciparum cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:8480–91. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. (C) EPAC1 bound to I942. The mixed intermediate (dashed box) includes PBC “in” and C-terminal hinge helix (H) “out” conformations [13]. The out conformation of the hinge helix leads to inhibition of the catalytic region (CR), as it obstructs access to its Rap1 substrate. (D) EPAC1 bound to cAMP and CE3F4R, which uncompetitively binds to EPAC1 and stabilizes the mixed intermediate state (dashed box), where the PBC is “in” and the C-terminal hinge (H) is “out” [14]. The figures are adapted with permission from Boulton S, Selvaratnam R, Blondeau J-P, Lezoualc’h F, Melacini G. Mechanism of Selective Enzyme Inhibition through Uncompetitive Regulation of an Allosteric Agonist. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:9624–37. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

pfPKG. PKG is also involved in proliferation of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite, one of the primary pathogens responsible for malaria [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49]. Elucidating the mechanism of allosteric inhibition through targeting the cGMP-binding domain of P. falciparum PKG (pfPKG) may potentially help in designing new drugs to combat malaria, as is needed due to an increasing resistance to current treatments. For this purpose, a cGMP-analog which activates pfPKG only partially, known as 8-NBD-cGMP, was investigated in complex with CBD-D of pfPKG [11]. pfPKG contains four tandem CBDs (Fig. 1A), but CBD-D is the domain primarily responsible for the autoinhibition and cGMP-dependent activation of pfPKG [50], [51].

The CHESPA analysis of the CBD-D of pfPKG shows that the 8-NBD-cGMP-bound CBD-D samples a conformational ensemble that includes its native inactive and active states, as well as a mixed intermediate state. In this mixed state, the pre-lid region, which includes a helix that rotates in conjunction with the PBC, resembles the active state, whereas the lid in the C-terminal helix is disengaged, similar to the inactive state (Fig. 2B; dashed box) [11]. MD simulations were performed starting from a model of the mixed intermediate built based on structural information gathered from NMR. The MD trajectories corroborated the hypotheses on the conformation of the bound 8-NBD-cGMP, and the overall structure of the otherwise elusive mixed intermediate state (vide infra).

The combined CHESPA and MD results show that sampling a mixed intermediate state allows the inhibitor to preserve high affinity to the allosteric domain through the engagement of essential elements of the binding site, such as the PBC that stabilizes the interaction with the phosphate of the analog. On the other hand, the lid disengagement makes the domain inhibition-competent via failure to form interactions critical for activation. Hence, we hypothesized that inhibitors which stabilize the mixed intermediate state relative to the native inactive or active states are more potent than those that simply target purely inactive or active states. Targeting the fully inactive state alone is likely to lead to affinity losses and poor potency, while targeting the fully active state compromises the efficacy of the inhibitor. Targeting the mixed intermediate, however, provides an opportunity to enhance the inhibition without excessively compromising potency.

EPAC. The guanine Exchange Protein directly Activated by cAMP (EPAC) is another cyclic nucleotide-regulated enzyme that serves as a potential drug target for the treatment of a wide range of diseases, from pancreatic [52], [53] to breast cancer [54], diabetes [55] and viral infections such as SARS and MERS [56]. Recent mechanistic studies have focused on elucidating the mechanisms of two different EPAC allosteric partial agonists discovered through screening: I942 [13] and CE3F4R [14]. Both I942 and CE3F4R are non-cNMP ligands that act on the CBD of EPAC isoform 1 (EPAC1), and both stabilize mixed intermediate states, yet through very distinct mechanisms [13], [14].

I942 is a competitive partial agonist with respect to cAMP [13], [29], and its mechanism of action conforms to the pattern observed in the previously discussed mechanisms based on an ensemble of three states, including a purely inactive, a purely active, and a mixed intermediate state (Fig. 2C) [13]. The distinguishing feature of this mixed intermediate state is that the PBC adopts the ‘in’ conformation, similar to the active state, while the C-terminal hinge helix, which is responsible for orienting the catalytic region relative to the regulatory region, is in the ‘out’ conformation, similar to the inactive state (Fig. 2C; dashed box). Hence, the I942 partial agonism arises through stabilization of both inactive and intermediate states (Fig. 2C).

Sampling of a mixed EPAC1 CBD state is also central to the mechanism of CE3F4R, which is an unconventional partial agonist since it is uncompetitive with respect to cAMP [14], [31]. CE3F4R binding to EPAC1 is conditional on cAMP binding, and partial agonism arises via formation of a ternary complex involving the EPAC1 CBD, cAMP and CE3F4R [31]. CE3F4R binding occurs at the α/β subdomain interface, as opposed to the cAMP binding site (Fig. 2D). This binding mechanism allows CE3F4R to act as a wedge that stabilizes a cAMP-bound mixed intermediate state where the PBC is engaged by cAMP (i.e. active PBC conformation), but the hinge helix is in the inactive conformation.

Due to the inactive orientation of the hinge in the presence of CE3F4R, EPAC1 adopts a closed topology where the catalytic domain is inaccessible to its Rap substrate (Fig. 2D). This mechanism of stabilization of the mixed intermediate state not only explains why CE3F4R is selective for EPAC1 vs. the EPAC2 isoform, but also provides critical insight into the use of allosteric inhibitor combinations. In EPAC2 a glutamine residue in the EPAC1 PBC is replaced by a lysine, which forms a salt bridge with a glutamate in the hinge helix, thus stabilizing its active conformation and destabilizing the mixed intermediate preferred by CE3F4R. The mixed state also provides a basis to understand why CE3F4R cannot be used in combination with the phosphorothioate cAMP analog Rp-cAMPS, which is a well-known allosteric antagonist of EPAC1 [57]. Rp-cAMPS binds to the cAMP binding site and stabilizes the PBC in the ‘out’ conformation due to the presence of a bulky sulfur atom, thus destabilizing the mixed state to which CE3F4R selectively binds.

The CE3F4R/Rp-cAMPS example highlights the importance of elucidating the mechanism of allosteric inhibition to guide the choice of inhibitor mixtures. In principle, ideal multidrug combinations could be identified solely based on ‘blind’ screening campaigns [58]. However, inherent combinatorial complexity is a notorious bottleneck in combination therapies, as it limits the feasibility of exhaustively searching all possible drug-pairs from conventional libraries [59], [60]. Hence, knowledge of allosteric mechanisms is anticipated to be valuable for filtering ligand libraries into more targeted subsets to enable more efficient combinatorial screening.

In general, the examples discussed above illustrate how diverse partial agonists enhance their effectiveness to bind and inhibit target enzymes through sampling mixed intermediate states. The mixed intermediates are ideally suited for maintaining stable binding interactions with the ligands through the engaged PBC, while retaining the ability to inhibit enzymatic function by disengaging the C-terminal helix that links the regulatory and catalytic domains or regions, thus perturbing interactions required for activation. However, the partial agonism mechanisms discussed so far are based on the effect of the allosteric modulator on single isolated domains. Considering that signaling proteins are often multi-domain, it is critical to explore whether mixed states also play a central role in longer constructs that better recapitulate multi-domain complexity.

3. Sampling of ‘mixed’ intermediate states by an allosteric multi-domain system explains allosteric pluripotency

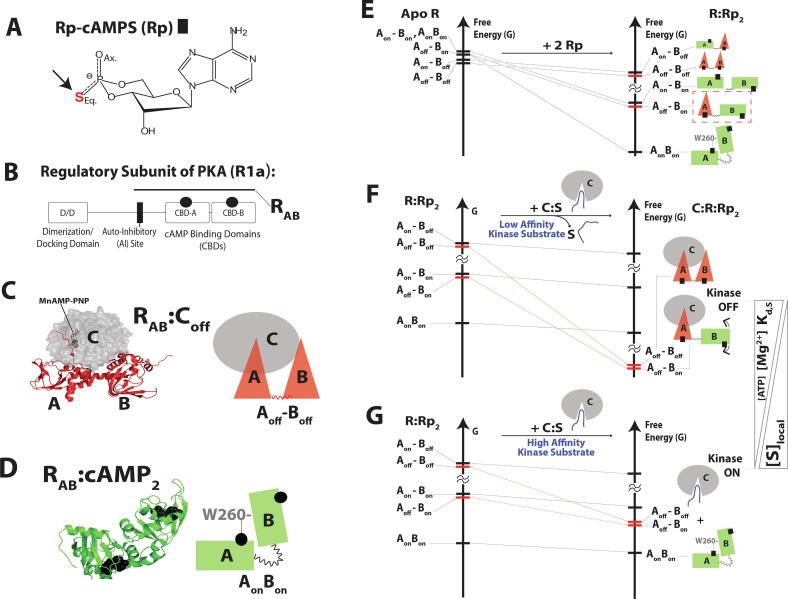

Mixed intermediate states are relevant also for multi-domain proteins, especially when different domains bind the same allosteric ligand, but with different allosteric responses. An example of this type of mixed state for a multi-domain system was observed in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) bound to Rp-cAMPS (Rp). Rp (Fig. 3A) is the primary allosteric inhibitor for PKA known to date, despite extensive screening efforts aimed at inhibiting the cancer-driver function of PKA [61], [62], [63], [64], [65]. Interestingly, in the presence of MgATP, Rp acts as an antagonist for PKA, but in the absence of MgATP, it acts as an agonist [66]. This phenomenon is referred to as allosteric pluripotency. Understanding allosteric pluripotency is essential to translate allosteric modulators into effective therapeutics, because when the effect of an allosteric ligand depends on the environmental conditions, undesired side effects may arise [67].

Fig. 3.

The multidomain PKA regulatory subunit bound to an allosteric inhibitor, Rp-cAMPS, samples an excited “mixed” state (Aoff-Bon) that drives allosteric pluripotency. (A) Structure of Rp-cAMPS. (B) Domain organization of the regulatory subunit. (C) In the absence of cAMP, the regulatory subunit (R) inhibits the catalytic subunit (C). The inhibitory site linked to CBD-A docks into the active site of the C-subunit, and is further stabilized by MgATP (or MnAMP-PNP, which is a non-hydrolyzable ATP analogue). (D) When cAMP binds to each of the CBDs, conformational changes occur that allow the C-subunit to be released. The inter-CBD interaction through W260 stabilizes the “on” conformations of the CBDs. (E) The free-energy hierarchy of apo R and free energy changes upon binding of Rp. The AonBon becomes the ground state, and the inhibition-competent “mixed” state (Aoff-Bon) is one of the excited states (red dashed box). (F) When the C-subunit is added to R:Rp2 in the presence of high [MgATP], the inhibition-competent states (red bars) are stabilized and become the ground states. (G) When the C-subunit is added to R:Rp2 in the absence of MgATP, the R:C interaction is less stable, and the inhibition-competent states remain excited. Since the ground state conformer exhibits low affinity for PKA C, the kinase function is activated. Figures are adapted from Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. Reprinted with permission from AAAS. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

PKA. A distinct difference between PKA and the allosteric enzymes discussed above (PKG and EPAC) is that the PKA regulatory subunit (R) and catalytic subunit (C) belong to separate polypeptide chains (Fig. 3B-D) [68], [69], [70]. In the absence of cAMP, the R-subunit binds and inhibits the C-subunit (Fig. 3C) [68]. The R-subunit of PKA includes two tandem CBDs (CBD-A and B). When cAMP binds to each of the CBDs (A and B), conformational changes occur within the R-subunit (Fig. 3D) that allow the release of the C-subunit [68]. The main R:C interaction is through CBD-A, especially though the inhibitory linker in CBD-A that docks into the active site of the C-subunit [69]. This interaction is further stabilized through binding of MgATP (Fig. 3C) [71].

When both CBDs adopt an 'on’ state similar to the cAMP-bound state (Fig. 3D), the R-subunit is inhibition-incompetent and the kinase function of PKA is turned on. When CBD-A shifts to the ‘off’ state, similar to the C-subunit-bound structure, the R-subunit is inhibition-competent and has the potential to turn off the kinase function of PKA. CHESPA shows that when Rp binds to the R-subunit in the absence of C-subunit and of inter-CBD interactions, Rp turns off CBD-A and turns on CBD-B [10]. However, the inter-CBD interaction, which relies on capping of the cNMP base moiety in CBD-A by residue W260 of CBD-B [72], [73], facilitates the conversion of CBD-A to the on state, as confirmed through NMR and independent MD simulations (vide infra) [10]. This conversion leads Rp-bound R-subunit to sample a complex conformational ensemble that includes a ground state, where both CBDs are in the on state and interacting with each other, and multiple excited states in which the inter-CBD interaction is absent (Fig. 3E). One of the excited states of the R:Rp2 complex is inhibition-competent as CBD-A is in the ‘off’ state (Fig. 3E; dashed red box). The relative population of each state in the ensemble was computed through EAM, resulting in a map of the free energy landscape for the R-subunit (Fig. 3E).

The free energy landscape of PKA R rationalizes the allosteric pluripotency observed for Rp. In the presence of MgATP, the R:C interaction is favoured, and the mixed inhibition-competent state becomes the ground state upon C-subunit binding, forming a stable C:R:Rp2 complex and leading to PKA inhibition (Fig. 3F). In the absence of MgATP, the R:C interaction is less stable, and thus, the mixed state remains at a high free energy level and the kinase is active, as the ground state of R:Rp2 does not bind PKA C (Fig. 3G). Hence, the main driver of the allosteric pluripotency is the mixed excited state where CBD-A is off and CBD-B is on (Fig. 3E; dashed red box).

Overall, the comparative analysis of partial agonism in hPKG, pfPKG, EPAC and PKA (Fig. 2, Fig. 3E) reveals that mixed conformational states, either within or between domains, provide critical explanations of allosteric modulation and meaningful insights into potential drug design strategies. The mixed intermediate states were primarily identified by NMR spectroscopy. NMR enables Chemical Shift Projection and Covariance Analyses (CHESPA and CHESCA), which have proven instrumental in determining the mechanism of partial agonism and allosteric pluripotency [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Further insight is obtained when NMR is complemented with additional structural and dynamical information from MD simulations, and related to function through an EAM. In the second half of this review, we will discuss how MD simulations and EAM can be implemented to complement NMR and bridge the gap between protein dynamics and function.

4. MD simulations provide a glimpse of the otherwise elusive ‘mixed’ inhibitory intermediate states, and means to generate targeted and testable hypotheses

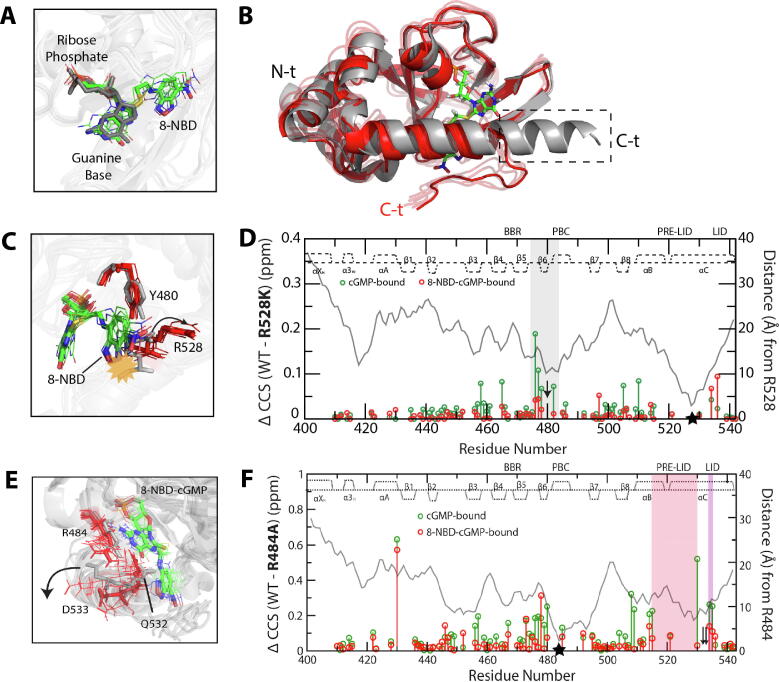

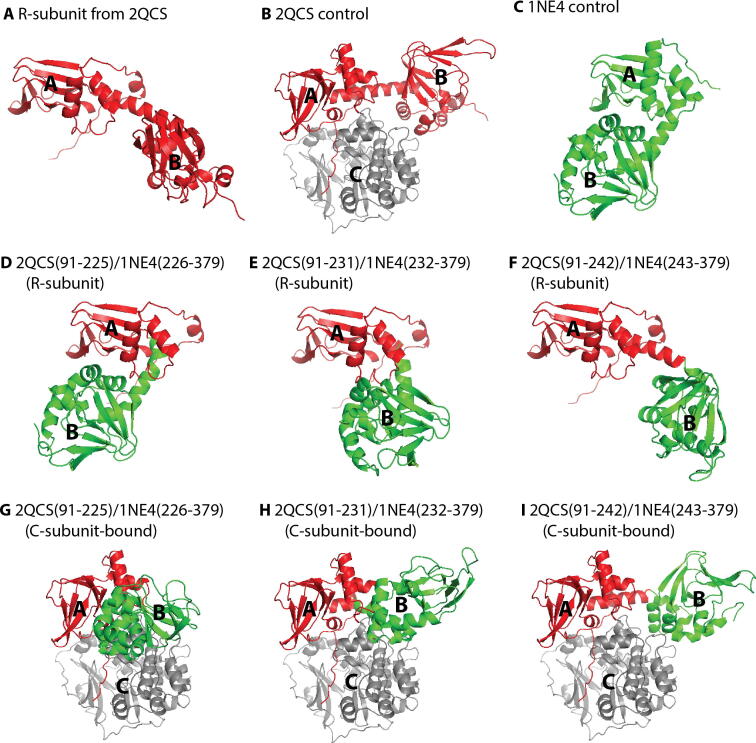

In conjunction with experimental analyses, MD simulations can be used to assess or confirm allosteric features that are not easily accessible experimentally, as well as to formulate hypotheses for further experimental work. An example is illustrated by the recent study of the mechanism of inhibition of PfPKG by the cGMP analogue 8-NBD-cGMP [11]. As discussed in the previous section of the review, through functional and NMR-based analyses it was determined that upon binding 8-NBD-cGMP, the critical CBD of PfPKG (i.e. CBD-D) samples an inhibition-competent intermediate structure in which the pre-lid region is in an active-like arrangement, while the C-terminal lid remains disengaged as in the inactive state (Fig. 2B). To further investigate the molecular details of the intermediate structure, MD simulations were performed on the cGMP-bound active structure of PfPKG CBD-D, and on an 8-NBD-cGMP-bound hybrid structure of PfPKG CBD-D, which represents the intermediate state. The latter consists of the N-terminal α-helices, β-subdomain and pre-lid region of the active structure, and the C-terminal lid of the inactive structure grafted onto the end of the pre-lid region, with 8-NBD-cGMP docked into the cGMP binding pocket (Fig. 4A, B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of 8-NBD-cGMP bound to pfPKG CBD-D on C-terminal helix interactions necessary for kinase activation. (A) Overlay of the bound ligands from cGMP-bound CBD-D, and from representative structures of 8-NBD-cGMP-bound CBD-D generated from MD simulations. The syn orientation of cGMP is preserved in 8-NBD-cGMP. (B) Aligned representative structures of cGMP-bound CBD-D (grey) and 8-NBD-cGMP-bound CBD-D (red) generated from the MD simulations. The dashed box indicates the C-terminal lid region that becomes disordered in the 8-NBD-cGMP-bound CBD-D, as schematically shown in Fig. 2B. (C) Similar to panel (B), but zoomed into the Y480-R528 region. The yellow starburst indicates the steric clash of the 8-NBD substituent with the R528 side chain in the active structure, and the arrow indicates the structural shift of the R528 side chain upon binding of 8-NBD-cGMP. (D) WT-versus-R528K chemical shift differences for cGMP-bound (green) and 8-NBD-cGMP-bound (red) CBD-D. The distance from R528 (as measured in the cGMP-bound structure) is shown as a grey line, and the secondary structure in the cGMP-bound CBD-D is indicated at the top of the plot. The mutation site is indicated by a black star, and the grey highlight indicates residues near Y480 (black arrow), where perturbations induced by the mutation in the cGMP-bound complex are lost when cGMP is replaced by 8-NBD-cGMP. (E) Similar to panel (C), but zoomed into the capping-triad region (i.e. R484, Q532, D533) to highlight the shift of the D533 side chain (arrow) upon binding of 8-NBD-cGMP. (F) Similar to panel (D), but for the R484A mutant of CBD-D. Pre-lid and lid residues are indicated by pink and purple highlights, respectively, and capping-triad residues Q532 and D533 by black arrows. The figures were adapted with permission and were originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry. Byun JA, Van K, Huang J, Henning P, Franz E, Akimoto M, et al. Mechanism of allosteric inhibition in the Plasmodium falciparum cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:8480–91. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Representative structures were selected from each simulation via cluster analysis, and overlaid to compare the structural tendencies in each simulation (Fig. 4A-C, E). In agreement with the NMR data, the overlaid structures suggested that the guanine base and ribose-phosphate moieties of 8-NBD-cGMP preserve a binding pose similar to that of cGMP (Fig. 4A). More notably, the structures suggested that the side chain of lid residue R528 would sterically clash with the 8-NBD moiety of 8-NBD-cGMP in the active structure, but not in the intermediate structure, thus favoring disengagement of the lid via disruption of the key Y480/R528 interaction that forms in the active-state arrangement of the lid (Fig. 4B, C) [51]. The intermediate structure also perturbs the capping triad, leading to disengagement of the R484/D533 lid interaction (Fig. 4E). Indeed, subsequent NMR-based comparisons of the R528K and R484A mutants with wild-type PfPKG CBD-D revealed that the mutations produced visible perturbations within cGMP-bound PfPKG CBD-D, while the perturbations were largely suppressed within 8-NBD-cGMP-bound PfPKG CBD-D (Fig. 4D, F), suggesting that the Y480/R528 and R484/D533 interactions are disrupted in 8-NBD-cGMP-bound wild-type PfPKG CBD-D, and thus confirming the conclusions drawn from the MD simulations. This example illustrates the synergy between MD simulations and NMR analyses of regulatory conformational equilibria.

Another example of the use of MD simulations is illustrated by the recent study of allosteric pluripotency that occurs upon binding of the cAMP analogue Rp-cAMPS (Rp) to the tandem CBDs of the PKA regulatory subunit (Fig. 3A-D) [10]. In particular, NMR-based analyses of the PKA R-subunit both with and without bound PKA C-subunit suggested that coupling between the conformational equilibria within the CBD-A and CBD-B domains of the R-subunit, and the previously-reported inter-domain interaction between CBD-A and CBD-B, is a key contributor to the allosteric pluripotency observed upon Rp binding. To refine this hypothesis, MD simulations were performed on Rp-bound structures of the R-subunit, and the R-subunit in complex with the C-subunit (Fig. 5). The simulations were started from available structures with the R-subunit in its fully-inactive (i.e. with both CBD-A and CBD-B in their ‘off’ conformations, and not interacting with one another; Fig. 5A, B) or fully-active conformation (i.e. with both CBD-A and CBD-B in their ‘on’ conformations, and interacting with one another; Fig. 5C), as well as from a series of hybrid structures with CBD-A in its ‘off’ conformation and CBD-B in its ‘on’ conformation (Fig. 5D-I). The latter structures were generated by grafting the CBD-B from the active structure onto the CBD-A from the inactive structure. Specifically, the structures of the tandem CBDs were joined at points along the intervening α-helix where kinks are present in the active structure but not in the inactive structure, resulting in hybrid structures with varying distances between the CBD-A and CBD-B domains (Fig. 5D-I and 6A). The structures generated from each simulation were then analyzed by computing RMSDs from the inactive and active structures, and distances between the centers-of-mass (CMs) of the constituent domains, to assess the structural tendencies during each simulation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Outline of the hybrid PKA R-subunit initial structures used for MD simulations. (A, B) Fully-inactive structure of the R-subunit (i.e. CBD-A ‘off’/CBD-B ‘off’), without (A) and with (B) bound C-subunit. (C) Fully-active structure of the R-subunit (i.e. CBD-A ‘on’/CBD-B ‘on’). (D-F) Hybrid R-subunit structures, consisting of the inactive CBD-A and active CBD-B (i.e. CBD-A ‘off’/CBD-B ‘on’). (G-I) As in (D-F), but with bound C-subunit. In all structures, the R-subunit and C-subunit residues derived from the inactive structure are shown in red and grey, respectively, while the R-subunit residues derived from the active structure are shown in green. Figures are adapted from Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. Reprinted with permission from AAAS. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

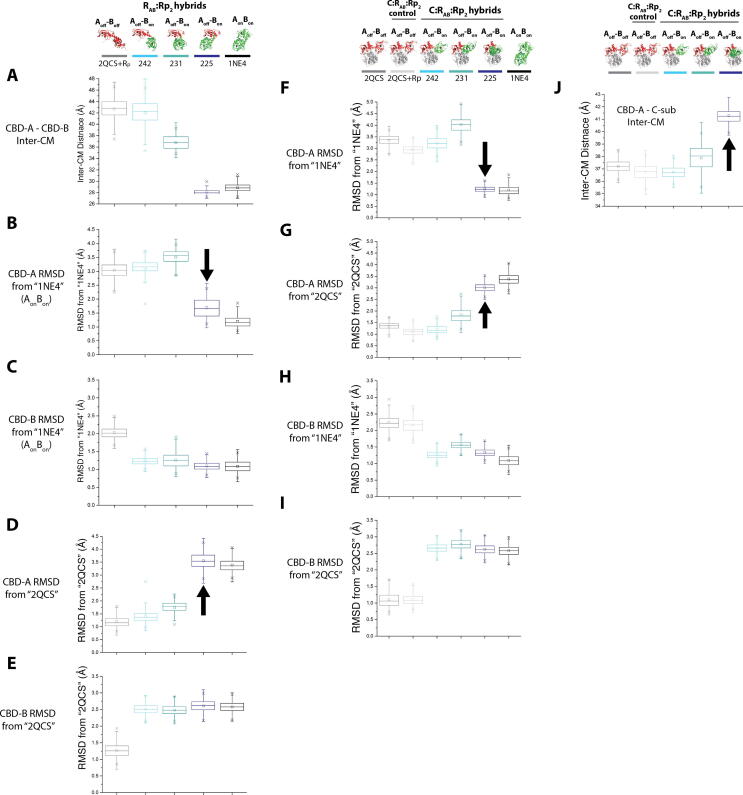

Fig. 6.

Analysis of the MD simulations of PKA. (A) Inter-center of mass (CM) distances between CBD-A and CBD-B, computed from MD simulations of the PKA R-subunit structures lacking bound C-subunit. (B) RMSDs of CBD-A relative to the fully-active structure, computed from MD simulations of the PKA R-subunit structures lacking bound C-subunit. (C) As in (B), but for the RMSDs of CBD-B relative to the fully-active structure. (D, E) As in (B, C), but for the RMSDs relative to the fully-inactive structure. (F, G) As in (B, D), but for MD simulations of the PKA R-subunit structures with bound C-subunit. (H, I) As in (C, E), but for MD simulations of the PKA R-subunit structures with bound C-subunit. (J) Inter-CM distances between CBD-A and the C-subunit, computed from MD simulations of the PKA R-subunit structures with bound C-subunit. The headers at the top of the figure illustrate the initial structures utilized for the MD simulations (Fig. 5), and the respective color codes in the plots. Notable shifts toward inter-CM distances or RMSD values similar to the fully-active structure that were observed from the simulations are indicated by black arrows. Figures are adapted from Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

In agreement with the original NMR-based hypothesis, the simulation results suggested a coupling between the conformational equilibria within the CBD-A and CBD-B domains, and the inter-domain interaction between the CBD-A and CBD-B domains. Specifically, while CBD-B remained close to its ‘on’ conformation for all hybrid structures (Fig. 6C, E, H, I), CBD-A consistently exhibited a shift to its ‘on’ conformation in the hybrid structures where CBD-A and CBD-B were closer together (i.e. the “225” hybrid structures shown in Fig. 5D, G), but remained closer to its ‘off’ conformation in the hybrid structures where CBD-A and CBD-B were further apart (i.e. the “231” and “242” hybrid structures shown in Fig. 5E, F, H, I; Fig. 6B, D, F, G). These results corroborated that formation of the inter-domain interaction between CBD-A and CBD-B promotes a shift of CBD-A to its ‘on’ conformation. In addition, the CBD-A domain and C-subunit moved apart from one another in the “225” hybrid structure, but remained close to one another in the “231” and “242” hybrid structures (Fig. 6J), highlighting a coupling between intra-R-subunit conformational shifts and C-subunit binding. Finally, it was predicted based on the simulation results that the distance between the CBD-A and CBD-B domains should vary among the different types of R-subunit complexes in the order C-subunit:R-subunit > C-subunit:R-subunit:(Rp)2 > R-subunit:(Rp)2 > R-subunit:(cAMP)2. This MD-based prediction was then tested, and confirmed, through paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) NMR experiments. This example on PKA, together with the previous example on PfPKG, illustrates how comparative analyses of MD simulations are an effective tool to refine hypotheses on the conformational ensembles accessed by dynamic systems. These hypotheses can then be tested through targeted ad hoc NMR experiments. However, MD simulations and NMR data alone are not always sufficient to enable the formulation of allosteric models that quantitatively predict function. To address this limitation and enable quantitative predictions, it is advantageous to complement MD and NMR with ensemble allosteric modeling, as explained in the next section.

5. Ensemble allosteric models (EAMs) bridge dynamics to function

It is often challenging to bridge the gap between dynamics and function by relying solely on NMR data, especially when dealing with a complex system. Thus, ensemble allosteric models (EAMs) are valuable for bridging the state dynamics mapped at atomic resolution by NMR to functional predictions testable through low-resolution assays such as enzymatic assays and electrophysiology [10]. EAMs are a statistical mechanical description of the free energy landscape, in which free energy levels are translated into specific state populations through normalized Boltzmann factors. As a result, EAMs enable the prediction of macroscopic averaged observables, such as binding affinities and degrees of activation/inhibition [10], [25].

To build an EAM, the first step is to define all of the microstates that are sampled by the system. To this end it is convenient to start from the simplest system, i.e. the apo form of the macromolecule, which typically samples ‘on/off’ conformational states. Further states can then be added to the EAM by including inter-domain interactions (e.g. closed vs. open states) and binding events (e.g. apo vs. bound states). For example, in the case of PKA and Rp (Fig. 3E), these states arise by considering combinations of (a) the ‘off’ and ‘on’ states of each domain; (b) the apo and Rp-bound states; and (c) the presence and absence of CBD-A:CBD-B interaction. The Boltzmann statistical weights of these states can then be estimated based on input parameters that include (i) the free energy difference of ‘off’ vs. ‘on’ states, (ii) the state-specific association constant of the ligand for each domain, (iii) the free energy of inter-domain interaction, and (iv) the state-specific association constant of the C-subunit to the R-subunit. Most of these input parameters can be measured through NMR, as discussed in the following section.

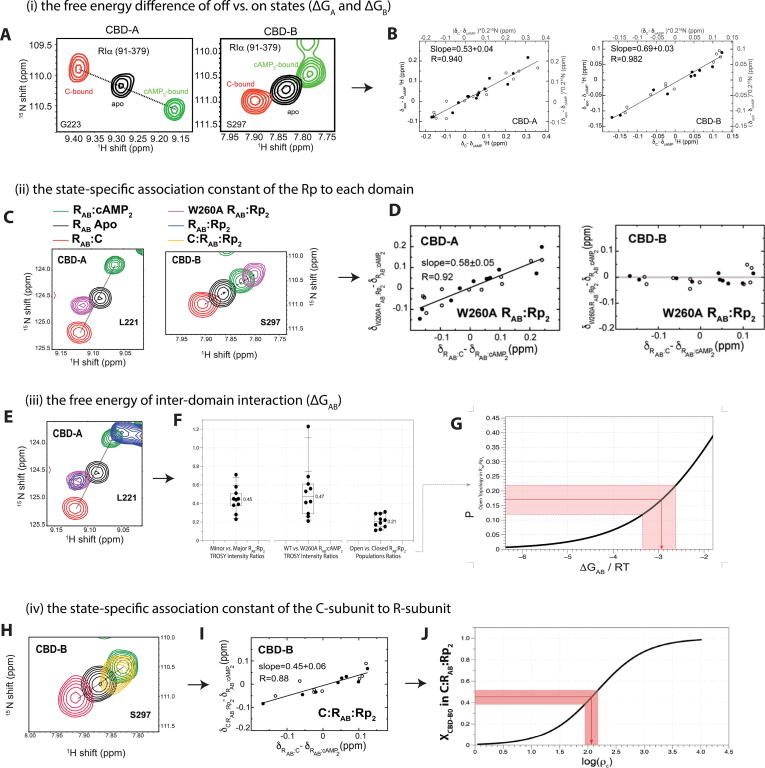

6. Measuring EAM input parameters by NMR

The input parameters of EAM can be effectively determined based on NMR data, such as chemical shifts and H/D exchange rates [10]. For example, in the case of the PKA/Rp system, the first parameter to determine is the free energy difference of ‘off’ vs. ‘on’ states in the apo form of each domain, i.e. input (i) for CBD-A and CBD-B, defined as ΔGA and ΔGB, respectively. The ΔGA and ΔGB free energies are determined considering that the exchange between the ‘on’ vs. ‘off’ states of each domain is fast in the NMR chemical shift time scale for both apo CBDs (Fig. 7A). This allowed us to measure the fraction of ‘on’ and ‘off’ states of the apo CBD-A and CBD-B based on the NMR chemical shifts (Fig. 7B). Such fractions were then converted into the ΔGA and ΔGB parameters assuming a two-state ‘on’/’off’ Boltzmann equilibrium for each domain (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 7.

Measuring EAM input parameters by NMR. (A) Representative NMR TROSY cross-peaks of apo R-subunit (CBD-A and CBD-B) and the reference cAMP-bound and C-bound R-subunits. (B) Chemical shift correlation plots of CBD-A and CBD-B for the apo sample, where the slope represents the fraction of ‘off’ states in each domain. The closed and open circles represent 1H and 15N chemical shifts, respectively. Figures are adapted from Akimoto M, McNicholl ET, Ramkissoon A, Moleschi K, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Mapping the Free Energy Landscape of PKA Inhibition and Activation: A Double-Conformational Selection Model for the Tandem cAMP-Binding Domains of PKA RIα. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002305. (C) Similar to panel (A), but with the addition of the W260A:Rp2 TROSY spectrum. (D) Similar to panel (B), but for the W260A:Rp2 sample. (E) Similar to panel (C), but with the addition of the WT:Rp2 TROSY spectrum. (F) Based on the TROSY cross-peaks in panel (E), the intensities of the minor and major peaks are measured, allowing for the calculation of the open vs. closed population ratios. This population ratio is used to estimate the ΔGAB, as shown in panel (G). (H) Similar to panel (A) right, but with the addition of the C:R:Rp2 TROSY spectrum. (I) Similar to panel (D), but for CBD-B of the C:R:Rp2 complex. (J) The fraction of ‘off’ state of CBD-B in the C:R:Rp2 sample can be used to estimate the ratio of state-specific association constants of C-subunit for R-subunit (ρC). Figures were adapted from Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

To see how the ensemble of states sampled by the apo R-subunit is remodelled by Rp binding (Fig. 3E), it is necessary to measure input parameter (ii), which refers to the state-specific association constants of the ligand to each domain. To simplify the measurement, we first measured for each CBD the ratio of state-specific association constants (ρA and ρB) based on the relative fractions of ‘off’ states in the apo and Rp-saturated CBDs, which are simply measured through NMR chemical shift analyses (Fig. 7C, D). We then measured the association constant of Rp for the ‘off’ state by titrating Rp into the R:C complex, which locks the R-subunit in the ‘off’ state, and monitoring the resulting NMR chemical shift changes. Based on the ρA and ρB values, and the respective association constants of Rp to the ‘off’ state, we then obtained also the association constant of Rp for the ‘on’ state of each domain.

Next, we measured input parameter (iii), which is the free energy of inter-domain interaction (ΔGAB). ΔGAB was measured through two independent approaches. The first method relies on the intensity of the cross-peak arising from the open topology (i.e. absence of inter-domain interaction) and on comparing that intensity to that of the cross-peak arising from the closed topology (i.e. presence of inter-domain interaction; Fig. 7E, F). This method can be used when the open and closed topologies are in slow exchange in the NMR chemical shift time scale. However, since the open and closed topologies exhibit different relaxation properties, the intensity measurements need to be corrected for the differential relaxation in the open vs. closed topologies. This can be done by utilizing mutations or ligands that lock the system in the open topology or the closed topology.

Once the population of the open topology of the Rp-bound state is estimated, the free-energy of inter-domain interaction can be obtained by calculating through the EAM how the open topology population depends on ΔGAB (Fig. 7G). The second approach we adopted to independently cross-check the ΔGAB value obtained from the first method relies on H/D exchange rates. By measuring the difference in the maximal protection factors (PFs) of the amide hydrogens in CBD-A of the WT vs. the W260A mutant (which silences the inter-domain interaction), it is possible to estimate the free energy of inter-domain interaction ΔGAB. The two approaches provided comparable values for ΔGAB.

Using similar approaches, we measured the last set of input parameters (iv), i.e. the state-specific affinities of the C-subunit for the R-subunit (Fig. 7H–J). To take into account how these affinities depend on the concentration of MgATP [71], we introduced a scaling factor (γ), with γ = 1 in the presence of MgATP and γ ≪ 1 in the absence of MgATP. These R:C affinities are important for determining the average fractions of R-subunit bound to C-subunit in the absence and presence of cNMP, which in turn lead to the fractional change of kinase activity upon cNMP addition.

After the EAM parameters were determined by NMR, it was possible to compute the statistical weights of each state in the conformational ensemble, and to quantitatively predict kinase activities upon addition of ligands such as cyclic nucleotides. Specifically, the average effective R:C association constants in the absence and presence of excess cNMP, such as Rp, were calculated as averages of state-specific association constants weighed by the populations in the apo or cNMP-bound forms (both in the absence of C-subunit). With these effective R:C association constants, the concentration of R-subunit not bound to the C-subunit ([R]) in the absence and presence of excess cNMP was computed through a classical quadratic equation (Eq. (1–4)):

| (1) |

with:

| (2) |

| (3) |

with:

| (4) |

where the KC values refer to the average effective R:C association constants either in the absence or presence of excess cNMP. With these [R] values and the effective R:C association constants, the fractional change of kinase activity () caused by the addition of cNMP was then computed based on classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics, in which the R-subunit serves as a competitive inhibitor of the C-subunit. Reference [10] includes detailed explanations on the derivations of relevant equations, and the construction of the EAM for PKA allosteric pluripotency.

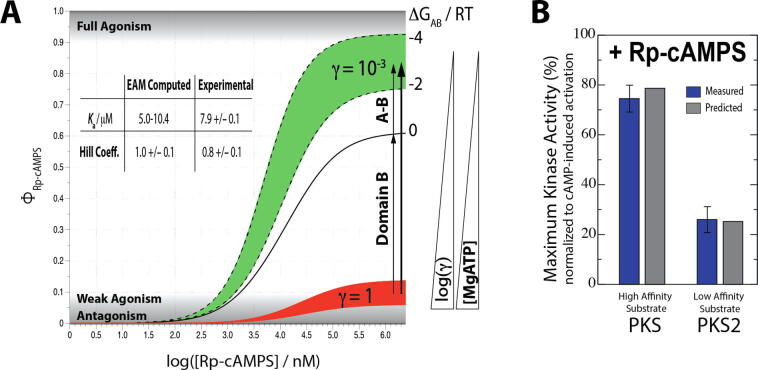

7. The EAM enables dissection of key allosteric drivers

With a fully parameterized EAM, it is possible to predict the kinase activity under different conditions, such as high or low concentrations of MgATP, varying substrate affinities (i.e. Km constants) and concentrations, and different R:C concentration ratios. As shown in Fig. 8A, the kinase activities predicted through the EAM with high and low γ values are in good agreement with the kinase activities measured experimentally for PKA:Rp in the presence and absence of MgATP [66]. Similar to the effect of MgATP, the affinity of the kinase substrate also affects the R:C affinity, and therefore contributes to varying responses of PKA to Rp, as is confirmed through both the EAM and enzymatic assays (Fig. 8B). These results illustrate how the EAM bridges the dynamical information revealed through NMR experiments to the functional activity measured through enzymatic assays.

Fig. 8.

The EAM reproduces the functional data for PKA and reveals new drivers of allosteric pluripotency. (A) The kinase activity upon addition of Rp is correctly predicted using EAM. The absence and presence of high [MgATP] is simulated with low and high γ values, respectively. The predicted Ka and Hill coefficients agree with the experimental data within error [66]. Both the inter-domain interaction, and the shifting of CBD-B to the ‘on’ state upon binding of Rp, contribute to the observed agonism. (B) The PKA kinase activity was measured with Rp in the presence of high- and low-affinity substrates (i.e. PKS and PKS2, respectively). The experimentally measured kinase activation values are in good agreement with the predicted values from EAM analysis. Figures are adapted from Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

Another distinct feature of the EAM is that it can also be used to dissect which factors within the system contribute to the agonism-to-antagonism switch (i.e. allosteric pluripotency). For example, we can estimate what the effect on kinase function would be if the inter-domain interactions were absent. By setting the ΔGAB parameter to 0, the kinase activity was predicted, which still exhibited significant activation (Fig. 8A). This allowed us to propose that the agonism observed with Rp arises not only from the inter-domain interaction that stabilizes CBD-A in the ‘on’ state, but also from the CBD-B shifting to the ‘on’ state upon binding of Rp.

Another relevant prediction of the EAM is that if the ‘mixed’ state is not sampled by the multi-domain protein, i.e. if both domains respond similarly to an allosteric effector, then full allosteric pluripotency will not be observed. For instance, using the PKA and Rp example, when Rp acts as an agonist for both CBD-A and CBD-B, the EAM predicts that Rp agonistically activates the kinase function of PKA in both the absence and presence of MgATP. On the other hand, when both CBDs are turned ‘off’ by binding to Rp, only antagonism or partial agonism is anticipated for Rp in the presence and absence of MgATP. These scenarios show how the ‘mixed’ state plays an essential role in driving allosteric pluripotency in a multi-domain system, and provide a compelling example of the added allosteric insight offered by the EAM.

Overall, the MD/EAM combination has played an important role as a predictive tool, and for developing critical hypotheses. MD simulations have provided insights on the conformational transition of CBD-A that were otherwise elusive. Such insight on the selective interaction of CBD-B with the ‘on’ state of CBD-A was critical for setting up the EAM. For example, when determining the statistical weight of the AonBon state, it allowed for an important correction of the state-specific association constant of Rp to the ‘on’ state of CBD-A based on the free-energy of inter-domain interaction. EAM then further predicted the functional outcome under different environmental conditions or properties of the system, such as the state-specific association constants or the free-energy of inter-domain interaction. This is a valuable resource to propose and examine hypotheses on the mechanisms underlying the observed function of a mutant or an analog-bound system.

8. Concluding remarks

In this review, we have shown how the combination of NMR, MD and EAM has revealed a plethora of partial agonism mechanisms. An emerging feature common to several mechanisms of partial agonism is a deviation from the classical two-state model of allostery (i.e. the active-inactive equilibrium). Such deviation arises primarily from the sampling of a ‘mixed’ state, in which different structural moieties within the same protein molecule exhibit different degrees of similarity to the active vs. inactive conformers. The mixed state may already be transiently sampled as a binding intermediate for the endogenous unmodified allosteric effectors, such as cAMP or cGMP.

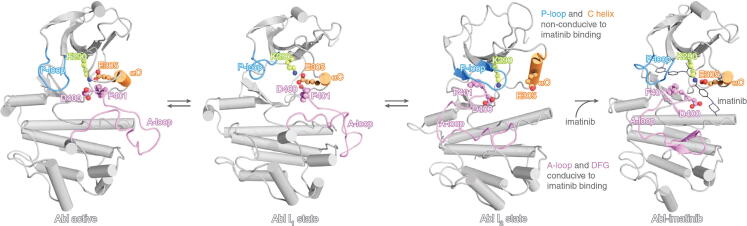

Here, we have discussed a few examples of systems that sample such mixed states upon binding of allosteric partial agonists, specifically the cNMP-binding domains of different enzymes. However, mechanisms based on mixed states are not limited only to the systems discussed here, suggesting that such mechanisms represent a potentially more generic phenomenon. For example, when imatinib, a clinically approved allosteric cancer therapeutic, binds to its target Abl kinase, the complex exhibits a ‘mixed’ state, where parts of the structure (i.e. the αC and P-loop) resemble the active state and other parts of the structure (i.e. the catalytic DFG motif and A-loop) resemble the inactive state (Fig. 9) [74]. The DFG motif in the ‘out’ conformation, similar to the inactive state, allows the imatinib to inhibit the kinase [74].

Fig. 9.

Abl kinase bound to imatinib adopts a ‘mixed’ conformation. The structures of Abl in the active state (left), the two inactive states (I1 and I2; middle), and the imatinib-bound state (right) are shown. The imatinib-bound state exhibits DFG and A-loop conformations resembling the I2 inactive state, and αC and P-loop conformations resembling the active state [74]. The figure was adapted from Xie T, Saleh T, Rossi P, Kalodimos CG. Conformational states dynamically populated by a kinase determine its function. Science 2020;370:eabc2754. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

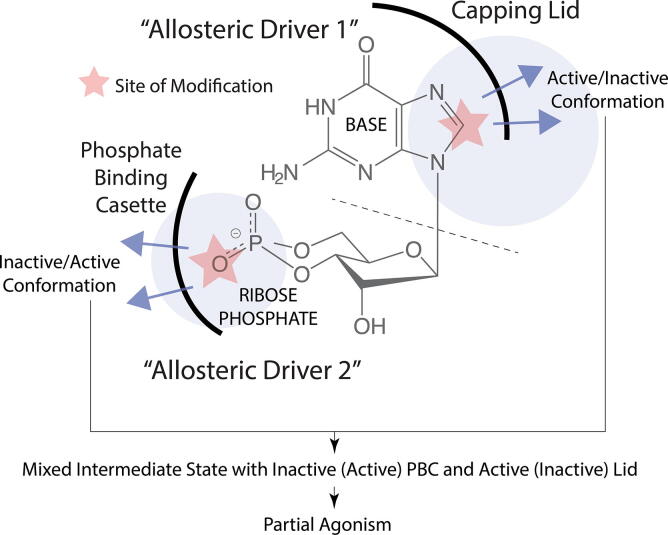

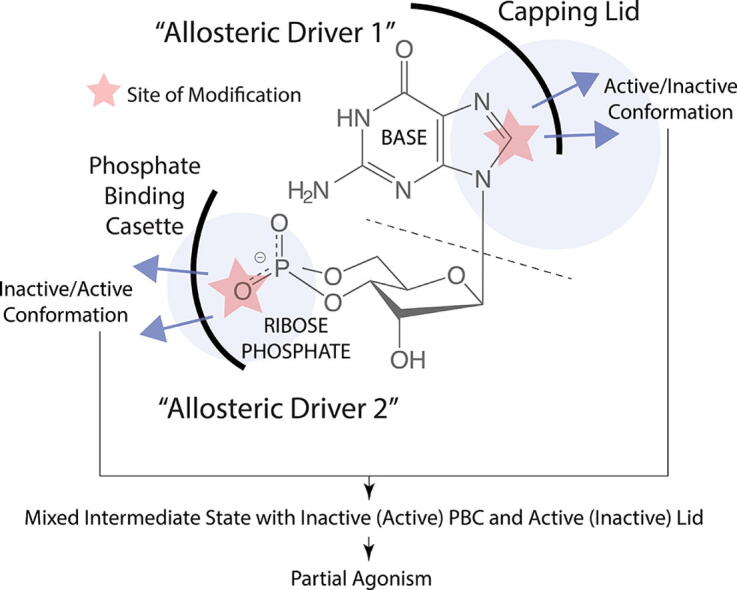

In general, the ability of modified ligands to stabilize and at least partially ‘trap’ a mixed intermediate reflects the presence of ‘mixed’ allosteric drivers within the same partial agonist (Fig. 10). For example, in the case of 8-NBD-cGMP, the unmodified cyclic phosphate moiety stabilizes the PBC of pfPKG in the ‘on’ conformation, similar to cGMP, while the modified base moiety stabilizes the C-terminal lid in the ‘off’ conformation. The opposite is true for Rp-cAMPS, where the modified cyclic phosphate stabilizes the PBC in the ‘off’ state, while the unmodified base favors native lid interactions in PKA, similar to cAMP, allowing ‘on’/’on’ inter-domain interactions to occur. It is the balance between these diverging allosteric drivers within the same ligand (Fig. 10) that dictates whether a mixed state is stabilized by a given partial agonist.

Fig. 10.

Different allosteric drivers within the same partial agonist can lead to ‘mixed’ conformational states. The cyclic nucleotide cGMP, which forms interactions with a CBD mainly through its base moiety (allosteric driver 1) and its ribose-phosphate moiety (allosteric driver 2), is shown as an example. The base is stabilized in the binding pocket through interactions with the base-binding region and capping lid of the CBD, whereas the phosphate binding cassette (PBC) of the CBD interacts with the ribose-phosphate of the cyclic nucleotide. When the ribose-phosphate is modified, for example, by replacing the equatorial oxygen with a bulkier sulfur, steric clashes with the PBC lead to the PBC sampling the “out” orientation, typical of the inactive conformation. On the other hand, when the base is modified, for example, by introducing additional aromatic motifs, engagement of the capping lid interaction, typical of the active conformation, may be perturbed. If two distinct allosteric drivers within the same ligand preferentially bind different conformations (e.g. active vs. inactive), mixed intermediate states are stabilized.

When a partial agonist stabilizes a mixed state, such mixed conformations often play a key role in the mechanism of partial agonism. For example, the mixed intermediate state stabilized by a partial agonist in an isolated domain may serve as an effective means to enhance the affinity of a partial agonist, as loss of activation is achieved with minimal disengagement of key binding elements, as in the case of 8-NBD-cGMP binding to pfPKG. Mixed states also rationalize the isoform selectivity of allosteric modulators, as in the case of CE3F4R and EPAC. Furthermore, we anticipate that mixed states play a key role in dictating the non-additivity of functional group contributions to the free energy of ligand binding, as recently reported [75]. In addition, the mixed conformational state in a multi-domain system, where domains respond differently to the same allosteric ligand, is an essential driver of allosteric pluripotency.

Overall, mixed conformational states within or between domains not only provide essential explanations for the observed functional responses, such as enzyme inhibition or allosteric pluripotency, but also offer new opportunities for drug design and therapeutic strategies, including synergistic multidrug combinations. For example, the allosteric pluripotency model proposed for PKA predicts that Rp-cAMPS is more likely to function as an antagonist than an agonist if administered together with an ‘adjuvant’ that weakens inter-domain interactions. In the case of EPAC, a mixed inhibitory intermediate explains why CE3F4R is an effective inhibitor in the presence of the cAMP agonist, but not of the Rp-cAMPS reverse agonist.

Considering that the cNMP binding domain is quite ubiquitous and serves as a prototype for conformational switches, the mixed conformational states we detected are also likely to be observed in other allosterically regulated proteins. Since the main determinant for the mixed conformational states lies in the mixed nature of the ligand (which includes drivers of inhibition and activation), and in how tightly these different drivers are coupled to different protein sections (i.e. domains or subdomains), we anticipate that any protein:ligand complex with such properties may sample mixed conformational states. The functional implications of sampling mixed states are best appreciated through quantitative allosteric models.

Quantitative models can be assembled by exploiting the synergies between NMR spectroscopy, MD simulations and EAM calculations. NMR is critical to identify the key states in the conformational ensemble. Starting from these states, MD enables the formulation of specific targeted hypotheses that can often be further tested by NMR, thus providing a higher-resolution picture of the ensemble. Based on the identified ensemble, an EAM model is built and parameterized by NMR to quantitively relate dynamics to function as measured by low-resolution assays (e.g. enzyme assays, electrophysiology, etc.) (Fig. 11). The ability to implement quantitative dynamics-function relationships is a first critical step towards tapping the translational potential of protein dynamics by facilitating the design of new allosteric modulators.

Fig. 11.

Synergies between NMR, MD and EAM enable quantitative modeling of enzyme function. NMR provides an initial map of the states within the conformational ensemble of a protein:partial-agonist complex, which serves as a basis to build initial structures for MD simulations and an EAM. The MD simulations serve as an effective means to generate refined targeted hypotheses to be tested by NMR. The EAM input parameters can often be measured by NMR. The fully parameterized EAM model enables bridging from protein dynamics to quantitative predictions of enzymatic function (e.g. kinase activity). Figures are adapted from Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jung Ah Byun: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Bryan VanSchouwen: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Madoka Akimoto: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Giuseppe Melacini: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Ahmed, N. Jafari, S. Boulton, J. Huang, and K. Van for helpful discussions. Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant 389522 (to G.M.), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grant RGPIN-2019-05990 (to G.M.).

References

- 1.Yang J.-S., Seo S.W., Jang S., Jung G.Y., Kim S. Rational engineering of enzyme allosteric regulation through sequence evolution analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nussinov R., Tsai C.-J. The design of covalent allosteric drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:249–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wodak S.J., Paci E., Dokholyan N.V., Berezovsky I.N., Horovitz A., Li J. Allostery in its many disguises: from theory to applications. Structure. 2019;27:566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J., Nussinov R. Allostery: an overview of its history, concepts, methods, and applications. PLOS Comput Biol. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarnera E., Berezovsky I.N. On the perturbation nature of allostery: sites, mutations, and signal modulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2019;56:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nussinov R., Tsai C.-J. Allostery in disease and in drug discovery. Cell. 2013;153:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu S., Shen Q., Zhang J. Allosteric methods and their applications: facilitating the discovery of allosteric drugs and the investigation of allosteric mechanisms. Acc Chem Res. 2019;52:492–500. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheik Amamuddy O., Veldman W., Manyumwa C., Khairallah A., Agajanian S., Oluyemi O. Integrated computational approaches and tools for allosteric drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:847. doi: 10.3390/ijms21030847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guarnera E., Berezovsky I.N. Allosteric drugs and mutations: chances, challenges, and necessity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2020;62:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byun JA, Akimoto M, VanSchouwen B, Lazarou TS, Taylor SS, Melacini G. Allosteric pluripotency as revealed by protein kinase A. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb1250. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Byun J.A., Van K., Huang J., Henning P., Franz E., Akimoto M. Mechanism of allosteric inhibition in the Plasmodium falciparum cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:8480–8491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.VanSchouwen B, Selvaratnam R, Giri R, Lorenz R, Herberg FW, Kim C, et al. Mechanism of cAMP Partial Agonism in Protein Kinase G (PKG). J Biol Chem 2015:jbc.M115.685305. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.685305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Shao H., Mohamed H., Boulton S., Huang J., Wang P., Chen H. Mechanism of action of an EPAC1-selective competitive partial agonist. J Med Chem. 2020;63:4762–4775. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulton S, Selvaratnam R, Blondeau J-P, Lezoualc’h F, Melacini G. Mechanism of selective enzyme inhibition through uncompetitive regulation of an allosteric agonist. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:9624–37. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b05044. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Schoepfer J., Jahnke W., Berellini G., Buonamici S., Cotesta S., Cowan-Jacob S.W. Discovery of asciminib (ABL001), an allosteric inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase activity of BCR-ABL1. J Med Chem. 2018;61:8120–8135. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skora L., Mestan J., Fabbro D., Jahnke W., Grzesiek S. NMR reveals the allosteric opening and closing of Abelson tyrosine kinase by ATP-site and myristoyl pocket inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:E4437–E4445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314712110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vahidi S., Ripstein Z.A., Juravsky J.B., Rennella E., Goldberg A.L., Mittermaier A.K. An allosteric switch regulates Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpP1P2 protease function as established by cryo-EM and methyl-TROSY NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:5895–5906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921630117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y., Zhang Z., Phoo W.W., Loh Y.R., Li R., Yang H.Y. Structural insights into the inhibition of Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease by a small-molecule inhibitor. Structure. 2018;26(555–564) doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paladino A, Woodford MR, Backe SJ, Sager RA, Kancherla P, Daneshvar MA, et al. Chemical Perturbation of Oncogenic Protein Folding: from the Prediction of Locally Unstable Structures to the Design of Disruptors of Hsp90–Client Interactions. Chem – A Eur J 2020;26:9459–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Guarnera E., Berezovsky I.N. Toward comprehensive allosteric control over protein activity. Structure. 2019;27(866–878) doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Martin C., Moroni E., Ferraro M., Laquatra C., Cannino G., Masgras I. Rational design of allosteric and selective inhibitors of the molecular chaperone TRAP1. Cell Rep. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J.-P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koshland D.E., Némethy G., Filmer D. Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits *. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilser V.J., Wrabl J.O., Motlagh H.N. Structural and energetic basis of allostery. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:585–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motlagh H.N., Hilser V.J. Agonism/antagonism switching in allosteric ensembles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:4134–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120519109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motlagh H.N., Wrabl J.O., Li J., Hilser V.J. The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature. 2014;508:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nature13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White J.T., Li J., Grasso E., Wrabl J.O., Hilser V.J. Ensemble allosteric model: energetic frustration within the intrinsically disordered glucocorticoid receptor. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2018;373:20170175. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang G.Y., Kim J.J., Reger A.S., Lorenz R., Moon E.W., Zhao C. Structural basis for cyclic-nucleotide selectivity and cGMP-selective activation of PKG i. Structure. 2014;22:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parnell E., McElroy S.P., Wiejak J., Baillie G.L., Porter A., Adams D.R. Identification of a novel, small molecule partial agonist for the cyclic AMP sensor, EPAC1. Sci Rep. 2017;7:294. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00455-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand G.S., Krishnamurthy S., Bishnoi T., Kornev A., Taylor S.S., Johnson D.A. Cyclic AMP- and (Rp)-cAMPS-induced conformational changes in a complex of the catalytic and regulatory (RI{alpha}) subunits of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2225–2237. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900388-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courilleau D., Bisserier M., Jullian J.-C., Lucas A., Bouyssou P., Fischmeister R. Identification of a tetrahydroquinoline analog as a pharmacological inhibitor of the cAMP-binding protein Epac. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44192–44202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.422956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J., Jones J.M., Nguyen-Huu X., Ten Eyck L.F., Taylor S.S. Crystal structures of RIalpha subunit of cyclic adenosine 5’-monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase complexed with (Rp)-adenosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphothioate and (Sp)-adenosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphothioate, the phosphothioate analogues of cA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6620–6629. doi: 10.1021/bi0302503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.East K.W., Skeens E., Cui J.Y., Belato H.B., Mitchell B., Hsu R. NMR and computational methods for molecular resolution of allosteric pathways in enzyme complexes. Biophys Rev. 2020;12:155–174. doi: 10.1007/s12551-019-00609-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulton S., Melacini G. Advances in NMR methods to map allosteric sites: from models to translation. Chem Rev. 2016;116:6267–6304. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisi G.P., Loria J.P. Solution NMR spectroscopy for the study of enzyme allostery. Chem Rev. 2016;116:6323–6369. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grutsch S., Brüschweiler S., Tollinger M. NMR methods to study dynamic allostery. PLOS Comput Biol. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masterson LR, Cembran A, Shi L, Veglia G. Allostery and Binding Cooperativity of the Catalytic Subunit of Protein Kinase A by NMR Spectroscopy and Molecular Dynamics Simulations, 2012, p. 363–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-398312-1.00012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Novello M.J., Zhu J., Feng Q., Ikura M., Stathopulos P.B. Structural elements of stromal interaction molecule function. Cell Calcium. 2018;73:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moroni E., Paladino A., Colombo G. The dynamics of drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15:2043–2055. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150519102950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenman D.J., Connors C.R., Chen W., Wang C., García A.E. Aβ monomers transiently sample oligomer and fibril-like configurations: ensemble characterization using a combined MD/NMR approach. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3338–3359. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang G.Y., Gerlits O.O., Blakeley M.P., Sankaran B., Kovalevsky A.Y., Kim C. Neutron diffraction reveals hydrogen bonds critical for cGMP-selective activation: insights for cGMP-dependent protein kinase agonist design. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6725–6727. doi: 10.1021/bi501012v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolter S., Golombek M., Seifert R. Differential activation of cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinases by cyclic purine and pyrimidine nucleotides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;415:563–566. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Börner S., Schwede F., Schlipp A., Berisha F., Calebiro D., Lohse M.J. FRET measurements of intracellular cAMP concentrations and cAMP analog permeability in intact cells. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:427–438. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cowman A.F., Healer J., Marapana D., Marsh K. Malaria: biology and disease. Cell. 2016;167:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hopp C.S., Bowyer P.W., Baker D.A. The role of cGMP signalling in regulating life cycle progression of Plasmodium. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor H.M., McRobert L., Grainger M., Sicard A., Dluzewski A.R., Hopp C.S. The malaria parasite cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase plays a central role in blood-stage schizogony. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:37–45. doi: 10.1128/EC.00186-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moon R.W., Taylor C.J., Bex C., Schepers R., Goulding D., Janse C.J. A cyclic GMP signalling module that regulates gliding motility in a malaria parasite. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McRobert L., Taylor C.J., Deng W., Fivelman Q.L., Cummings R.M., Polley S.D. Gametogenesis in malaria parasites is mediated by the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. PLoS Biol. 2008;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Govindasamy K., Jebiwott S., Jaijyan D.K., Davidow A., Ojo K.K., Van Voorhis W.C. Invasion of hepatocytes by Plasmodium sporozoites requires cGMP-dependent protein kinase and calcium dependent protein kinase 4. Mol Microbiol. 2016;102:349–363. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim J.J., Flueck C., Franz E., Sanabria-Figueroa E., Thompson E., Lorenz R. Crystal structures of the carboxyl cGMP binding domain of the plasmodium falciparum cGMP-dependent protein kinase reveal a novel capping triad crucial for merozoite egress. PLOS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franz E., Knape M.J., Herberg F.W. cGMP binding domain D mediates a unique activation mechanism in plasmodium falciparum PKG. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4:415–423. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Almahariq M., Tsalkova T., Mei F.C., Chen H., Zhou J., Sastry S.K. A novel EPAC-specific inhibitor suppresses pancreatic cancer cell migration and invasion. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:122–128. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Luo C., Cheng X., Lu M. Lithium and an EPAC-specific inhibitor ESI-09 synergistically suppress pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and survival. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2017;49:573–580. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmx045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar N., Gupta S., Dabral S., Singh S., Sehrawat S. Role of exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC1) in breast cancer cell migration and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;430:115–125. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-2959-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan J., Mei F.C., Cheng H., Lao D.H., Hu Y., Wei J. Enhanced leptin sensitivity, reduced adiposity, and improved glucose homeostasis in mice lacking exchange protein directly activated by cyclic AMP isoform 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:918–926. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01227-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tao X., Mei F., Agrawal A., Peters C.J., Ksiazek T.G., Cheng X. Blocking of exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP leads to reduced replication of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2014;88:3902–3910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03001-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Badireddy S., Yunfeng G., Ritchie M., Akamine P., Wu J., Kim C.W. Cyclic AMP analog blocks kinase activation by stabilizing inactive conformation: conformational selection highlights a new concept in allosteric inhibitor design. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(M110) doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He L, Kulesskiy E, Saarela J, Turunen L, Wennerberg K, Aittokallio T, et al. Methods for High-throughput Drug Combination Screening and Synergy Scoring, 2018, p. 351–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Zimmer A., Katzir I., Dekel E., Mayo A.E., Alon U. Prediction of multidimensional drug dose responses based on measurements of drug pairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:10442–10447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606301113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wood K.B. Pairwise interactions and the battle against combinatorics in multidrug therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:10231–10233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612365113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saloustros E., Salpea P., Starost M., Liu S., Faucz F.R., London E. Prkar1a gene knockout in the pancreas leads to neuroendocrine tumorigenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24:31–40. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veugelers M., Wilkes D., Burton K., McDermott D.A., Song Y., Goldstein M.M. Comparative PRKAR1A genotype-phenotype analyses in humans with Carney complex and prkar1a haploinsufficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:14222–14227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405535101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]