Significance

Is there a gender pay gap among graduates in some science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields? Women and men have near-identical human capital at college exit, but cultural beliefs about men as more fit for STEM professions than women may lead to self-beliefs that affect pay. We hypothesized that women and men would be paid differently upon college exit, and that gender gaps in self-beliefs about one's abilities, or self-efficacy, would correspond to this difference. Using data from a three-wave longitudinal study of graduates of engineering programs from 2015–2017, we find a confidence gap that aligns with a gender pay gap. Overall, these findings point to the role that cultural beliefs play in creating gender disparities among STEM degree-holders.

Keywords: gender, pay gaps, cultural beliefs, STEM

Abstract

Women make less than men in some science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. While explanations for this gender pay gap vary, they have tended to focus on differences that arise for women and men after they have worked for a period of time. In this study we argue that the gender pay gap begins when women and men with earned degrees enter the workforce. Further, we contend the gender pay gap may arise due to cultural beliefs about the appropriateness of women and men for STEM professions that shape individuals’ self-beliefs in the form of self-efficacy. Using a three-wave NSF-funded longitudinal survey of 559 engineering and computer science students that graduated from over two dozen institutions in the United States between 2015 and 2017, we find women earn less than men, net of human capital factors like engineering degree and grade point average, and that the influence of gender on starting salaries is associated with self-efficacy. We find no support for a competing hypothesis that the importance placed on pay explains the pay gap; there is no gender difference in reported importance placed on pay. We also find no support for the idea that women earn less because they place more importance on workplace culture; women do value workplace culture more, but those who hold such values earn more rather than less. Overall, the results suggest that addressing cultural beliefs as manifested in self-beliefs—that is, the confidence gap—commands attention to reduce the gender pay gap.

A gender pay gap exists in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), in part because within those majoring in STEM fields women choose majors that pay less, on average, than the majors men choose (1). Yet, even after accounting for college major, women make less than men with the same earned degrees in some STEM fields (2). In 2013, for instance, women with computing, mathematical, and engineering degrees earned between 82 and 87% of what men earned, or $65,000 on average annually compared to men’s $79,000 (3). The gender pay gap is consequential for a number of reasons. It affects who stays in the STEM workforce since lower compensation leads to less job satisfaction and greater exit from STEM jobs (4–6). Compensation also affects which individuals, after taking a break at critical junctures (e.g., for parental leave), are likely to return to the workforce (7).

One of the most striking aspects of the gender pay gap in STEM is that increasing women’s entry into STEM has been a primary policy aim for addressing the gender pay gap broadly. Specifically, women are directed into STEM-related majors and college degree programs as a part of initiatives designed to help women reach pay parity with men (8, 9). The main reason for this is that recipients of STEM degrees earn more, especially in lucrative, high-demand fields like engineering and computer science (CS), two fields with the largest representation in the STEM-employed workforce and some of the highest growth projections (10). Yet, of all of the STEM fields, engineering and CS have some of the lowest levels of occupational entry by women alongside some of the highest gender pay differentials (11). In assessing why pay gaps in these fields exist, scholars have pointed to women’s competing domestic priorities due to family formation (12, 13) and employer discrimination (14), but such explanations have been found to be applicable across STEM fields and across professions more generally (1, 15–17) and are not specific to engineering and CS (5, 18).

In this paper we focus explicitly on engineering and CS and why cultural beliefs about the “fitness” of women and men for these fields may correspond to pay. We undertake an investigation of initial salaries at college exit for undergraduates that have recently earned engineering and CS degrees. A study of initial salaries at workforce entry is appealing not only because human capital differences between men and women at college graduation are largely negligible, but also because later-stage factors that influence careers (e.g., childcare responsibilities) are less apt to be present among individuals at college exit.* Cultural beliefs about the appropriateness of women and men for engineering and CS that influence pay, meanwhile, may exist. Sociologists have argued that cultural beliefs about the appropriateness of women and men in engineering and CS professions operate at the societal level in ways that affect women’s and men’s beliefs (19, 20). Cultural archetypes such as “brogrammers” highlight men as more competent—and ultimately more fit—than women in CS and engineering fields. As a result, microlevel personal beliefs may come to be based on societal expectations that influence women’s and men’s own perceptions of their skills. Prior studies have investigated such personal beliefs, but they have concentrated on how these affect individuals earlier, such as when they are deciding a college major, or whether or not to continue in a STEM program (19, 20). By pivoting toward degree holders at workforce entry and hypothesizing about what occurs among those at college exit, we move a step closer to understanding how beliefs may influence an initial gender pay gap, if one exists.

The early-career stage is a particularly potent time for gendered personal beliefs to come to the fore. We specify personal beliefs here as one’s self-efficacy, a psychological concept defined as a judgment about one’s ability to perform a necessary course of action to achieve a goal (21). Prior work indicates that girls and women have lower confidence in their math and science ability than boys and men, net of actual ability in these subjects—that is, there is a confidence gap by gender in STEM (20, 22). During STEM matriculation in the secondary and postsecondary years, the lack of female STEM role models and faculty in classes can reinforce beliefs about the lesser abilities of women compared to men (19, 23–25). As women and men are first entering the workforce, personal beliefs in one’s engineering or technical ability may influence initial salaries.

Personal beliefs might have gendered effects on salaries in a number of ways. Women who are less confident about their technical abilities despite earning an engineering or CS degree may pursue less-competitive, lower-paying jobs than men who have recently earned those same degrees (9). This self-sorting might occur because less-confident women pursue lower-paying engineering or CS jobs, or because they opt to pursue jobs that are outside of engineering and CS which may pay less (5). Additionally, after receiving a job offer, less-confident women might be less likely to negotiate for higher salaries, or if they do attempt to negotiate those with less confidence might be less successful in receiving more compensation than more confident men (26). From the demand side of the labor market, even if less-confident women apply to lucrative jobs, studies indicate there are a number of ways such women might be reallocated or “steered” into applicant pools for jobs that pay less (27–29). Finally, less-confident individuals that may be considered for lucrative jobs might simply be rejected for those jobs, leaving them to pursue lower-paying options after one or more failed attempts at greater levels of remuneration. Each of these potential pathways for the effects of self-efficacy on the gender pay gap suggest the importance of personal beliefs. We expect the following:

-

H1)

Women who graduate with engineering and CS degrees make less than men who graduate with engineering and CS degrees.

-

H2)

Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between gender and salary among engineering and CS degree holders.

Empirical Considerations and Alternative Hypotheses

We compare our hypothesized relationships about gender, self-efficacy, and pay alongside two competing hypotheses that prior studies suggest might operate at the individual level to influence salaries: 1) socialized pay preferences and 2) female-friendly work environments. The first competing hypothesis, socialized pay preference, refers to girls and boys as well as women and men being socialized to expect different responsibilities across work and family as they get older. Scholars argue that girls and young women may be socialized to believe that money should matter little to them as they are not expected to be the primary breadwinners, so they should care less about salaries than men (30, 31). A second competing hypothesis, female-friendly work environments, refers to women placing greater emphasis on work culture than men. Women might prize environments that prioritize inclusion over competition, the latter being environments that might drive salaries higher (32). A gender pay gap might emerge to the extent that women place greater value on work cultures that pay less, not because they are less confident but because they prefer these environments more (33).

To test the main and alternative hypotheses, we use data collected from the Engineering Majors Survey (EMS), a three-wave longitudinal survey administered at 27 institutions in the United States (Materials and Methods). The first wave of surveys (EMS 1.0) was administered in winter/spring 2015 when students were still enrolled in college; the second wave (EMS 2.0) was administered in April 2016 and the third wave (EMS 3.0) in October 2017. We use data from EMS 1.0 and 3.0, in which we measured students’ engineering self-efficacy while still in school (EMS 1.0) and their workforce experiences to examine initial salaries among recent graduates (EMS 3.0). This study importantly measures self-efficacy prior to workforce entry and its correspondence to salary.

Results

At workforce entry, we find a significant difference between women and men in starting salaries (P < 0.01; Table 1). On average, women in our sample that graduate with engineering degrees earn less than $61,000 annually, while men earn above $65,000 annually. We model the relationship between sex and starting salaries of engineering and CS degree holders both without and with covariates (Table 2, models 1 and 2, respectively). Covariates include fixed effects for respondents’ home institutions, industry of employment, major field of study, and grade point average (GPA), as well as variables for degree type (B.A. or B.S.), year of graduation, whether they received a second degree, and whether they previously had an internship with the current employer (see SI Appendix, Table S1 for the correlation matrix for main variables and SI Appendix, Table S2 for a description of the covariates). We regress the logarithm of annual salary on female and find it is associated with a 9% decrease in salary overall without the covariates included (P < 0.01) and 7% decrease with covariates included (P < 0.05). Our first hypothesis, that women make less than men upon college exit when holding engineering and CS degrees, is supported.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by respondent sex

| Overall | Male | Female | Difference | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean diff. | SE | |

| Annual salary, $ | 63,709 | 21,370 | 65,358 | 21,899 | 60,631 | 20,038 | 4,728** | $1,888 |

| Engineering self-efficacy | 2.45 | 0.81 | 2.60 | 0.80 | 2.17 | 0.76 | 0.43*** | 0.07 |

| Importance of workplace culture | 2.67 | 0.97 | 2.52 | 0.99 | 2.95 | 0.85 | −0.44*** | 0.08 |

| Importance of compensation | 2.77 | 0.92 | 2.81 | 0.94 | 2.70 | 0.87 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Observations | 559 | 364 | 195 | 559 | ||||

**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Difference values are calculated with more significant digits than what is shown above, and statistics are from two-sample t tests.

Table 2.

OLS regressions predicting annual salary upon workforce entry

| Dependent variable: log annual salary | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Female | −0.091** | −0.069* | −0.044 | −0.064* | −0.088** | −0.056 |

| (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.030) | (0.032) | (0.031) | |

| ESE | 0.067** | 0.059** | ||||

| (0.019) | (0.018) | |||||

| Importance of compensation | 0.081** | 0.074** | ||||

| (0.015) | (0.015) | |||||

| Importance of workplace culture | 0.042** | 0.028* | ||||

| (0.015) | (0.014) | |||||

| Industry FEs | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Institution FEs | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Field FEs | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| GPA FEs | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Degree FEs | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year of degree FEs | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Second degree dummy | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Internship employer dummy | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.014 | 0.219 | 0.238 | 0.260 | 0.231 | 0.280 |

| Residual SE | 0.346 (df = 557) | 0.308 (df = 495) | 0.304 (df = 494) | 0.300 (df = 494) | 0.306 (df = 494) | 0.296 (df = 492) |

| Observations | 559 | 559 | 559 | 559 | 559 | 559 |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; two-tailed hypothesis testing. Robust SEs in parentheses. The abbreviation FEs indicates model is run with the indicated fixed effects. df, degrees of freedom.

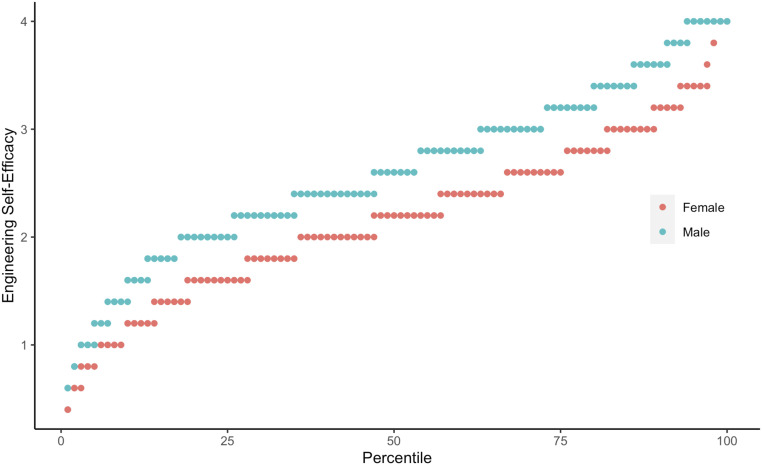

Next, we examine self-efficacy by sex. Women have lower levels of self-efficacy than men on average prior to graduation (P < 0.001; Table 1), and women have lower self-efficacy than men across the percentile distribution (Fig. 1). For example, men at their 50th percentile of engineering self-efficacy have the same level of engineering self-efficacy as women in the 67th to 75th percentile.

Fig. 1.

Percentile plot comparing engineering self-efficacy by sex. Women have lower self-efficacy than men across nearly all of the entire percentile range. n = 559.

We therefore investigate hypothesis 2 regarding whether or not self-efficacy mediates the relationship between gender and salary for engineering and CS degree holders. Our equations for mediation are as follows (34):

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

where Y is salary, the βs are the coefficients, Me is the mediator of interest, and ε is the error term. We examine the relationship between engineering self-efficacy (ESE) and salary and find there is a positive and statistically significant relationship, net other factors (β = 0.07, P < 0.01; SI Appendix, Table S3). To assess the simple mediation model, we carry out the other two mediation steps and find ESE is negatively associated with being female (β = −0.37, P < 0.01; SI Appendix, Table S4). Once ESE is included in the full model, the negative effect of being female is no longer significant (β = −0.04, P > 0.1; SI Appendix, Table S3). After conducting mediation analysis, we find support for the simple mediation model with ESE as a mediator (= −0.025, SE = 0.010, 95% CI = [−0.040, −0.008]; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The 95% CI for the proportion mediated ranged from 0.22 to 1.96 (P < 0.001; SI Appendix, Table S5). Thus, the second hypothesis, that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between gender and salary, is also supported. Women have lower levels of self-efficacy in carrying out technical tasks, and these differences correspond to initial salary upon workforce entry.

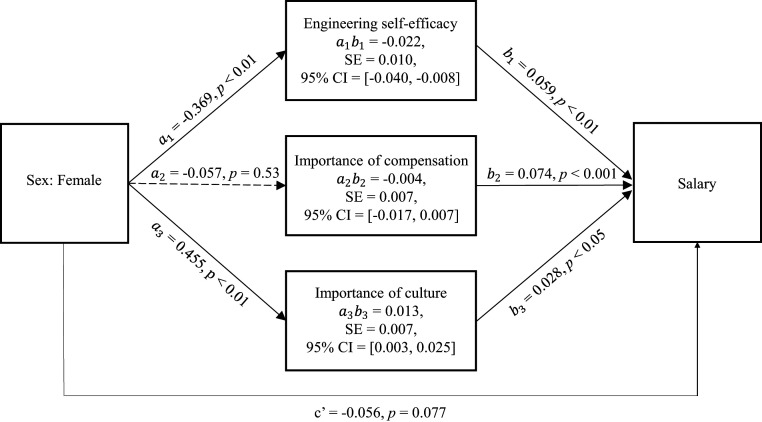

For the competing hypotheses, we find evidence that both preferences for higher compensation (alternative 1, β = 0.08, P < 0.01; Table 2, model 4) and value placed on workplace culture (alternative 2, β = 0.04, P < 0.01; Table 2, model 5) positively influence starting salary. However, these alternative hypotheses do not explain the gender pay gap among engineering and CS degree holders. Gender does not predict the importance placed on salary (β = −0.06, P > 0.1; SI Appendix, Table S6) because women and men do not differ in their perceptions of the value of receiving high salaries. In terms of the second alternative, women value workplace culture more than men (β = 0.46, P < 0.01; SI Appendix, Table S7). However, valuing workplace culture is associated with higher (not lower) salaries (β = 0.04, P < 0.01; see Table 2, model 5). To assess the robustness of the mediated effect of ESE in relation to the two alternative hypotheses, we perform parallel path mediation analysis to control for the effects of the two alternative mediators (35). As shown in Fig. 2, in the parallel multiple mediation model the relationship between female and salary was significantly mediated by ESE ( = −0.022, SE = 0.010, 95% CI = [−0.040, −0.008]) and by the importance of culture ( = 0.013, SE = 0.007, 95% CI = [0.003, 0.025]), but only ESE has a specific indirect effect that is negative and statistically significant.

Fig. 2.

Parallel multiple mediation model depicting the effect of being female on salary as mediated by engineering self-efficacy, importance of compensation, and importance of workplace culture. The specific indirect effects (, , ) for the mediators and direct effect for sex (c′) are shown with their SEs and 95% CIs. n = 559.

Why Do Personal Beliefs Affect the Salaries of Women and Men?

To build on possible explanations for why the confidence gap may impact the gender pay gap, we consider a number of explanations. We began by considering the possibility of performance differences across women and men. There is no evidence that women at the same level of self-efficacy as men perform worse academically or are in different majors that might lead to jobs with lower pay. We find that at every GPA level (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) and across major/degree programs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), women have lower or the same average levels of self-efficacy as men (see SI Appendix for indications of statistical difference).

Next, we considered graduates’ entry into engineering and CS jobs. We posited various reasons including self-sorting and employer rejection, whereby less-confident individuals who majored and graduated in engineering or CS do not end up working in engineering or CS jobs. We look at pay for men and women that take initial jobs in engineering and CS and find men earn on average $1,996 more yearly than women, a difference that is not statistically significant (t statistic = 0.87).† Meanwhile degree holders that took engineering and CS jobs upon graduation were paid more than those that did not take engineering and CS jobs (t statistic = 4.01), suggesting one potential way self-efficacy may be influencing salaries is through entry into engineering and CS jobs. We find that self-efficacy influences the intent to enter engineering and CS jobs, and this in turn partially influences individuals’ actual entry into engineering and CS jobs (see SI Appendix, Fig. S4 for the positive relationship between ESE and engineering and CS job entry).‡ Performing a path analysis, we calculate that 33% of the influence that self-efficacy has on salary is explained by the effect of entering an engineering or CS job.§

Discussion

In this paper we hypothesized that among engineering and CS degree holders women earn less than men at workforce entry. We also suggested personal beliefs stemming from broader cultural beliefs about the appropriateness of women and men for some STEM professions—that is, the confidence gap—would explain this pay difference. Using data from a longitudinal study of 559 degree earners in engineering and CS undergraduate programs, we find support for our hypotheses. Women earn less than men in their initial jobs. We find no evidence that this gap in pay is due to men’s having stronger interests in high-paying jobs than women, or because women have preferences for the culture of workplaces that might correspond with lower pay. Rather, we find that women have lower levels of self-efficacy than men, and that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between gender and initial salaries.

In focusing on what occurs at a critical transition—that is, college to work—we offer key insights into the gender pay gap. Prior work has established a number of factors that influence the gender pay gap at the midpoint career stage, including women facing competing priorities on their time (36–39), more challenges in accumulating human capital (40), and discrimination in being promoted into higher and/or more technical positions in organizations, all of which have been shown to affect pay (41, 42). Less clear has been what transpires as women and men are making their initial transitions into the workplace, at a juncture that may affect earnings over the course of a career (43). We offer evidence that gendered beliefs may not only influence how women and men rate their own abilities when deciding which majors or degrees to pursue in college (9, 10) but also at workforce entry. Our results suggest the consequences of gendered beliefs that appear to work in unison to affect the gender pay gap: 1) degree holders with lower levels of self-efficacy earn less in their initial jobs and 2) women have lower levels of self-efficacy than men.

Our study is well-suited to answer questions about self-efficacy and the transition from college to work due to its longitudinal nature, but there are aspects that provide opportunity for future work. We note that because cultural beliefs are embodied in norms, values, and institutions, they may be difficult to manipulate experimentally and we did not do so here. Nonetheless, future studies might consider an experimental or quasi-experimental approach to prompt personal beliefs to change and then track salary differences across women and men that might arise as a result. This would allow for a causal investigation of the effects of gender, self-efficacy, and salary. Future work might also consider how to comparatively study the effects of personal beliefs. For instance, research might study how the mediating effect of self-efficacy compares in STEM fields with higher female representation like biology to that in CS and engineering (44). Finally, future work might also seek to study additional ways that gendered beliefs influence salaries, such as the possible links they might have on successful salary negotiations (26).

In closing, there are several important practical implications from this study. Our results highlight the importance of career guidance as well as possibly internships and co-ops to strengthen students’ self-assessments and provide stronger bridges to engineering and CS jobs with higher pay (45). Our results also ask practitioners and industry experts to reconsider hiring practices that overemphasize confidence in one’s ability as an indication of likely job success. Since self-perceptions may not accurately reflect technical ability and may correspond to gender, doing so may only stand to widen the gender pay gap.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Stanford IRB #31803 and Stanford IRB #35539). All participants provided informed consent. The 350 US engineering schools in 2011 composed the population from which the 27 EMS institutions were sampled using a stratified scheme. Compared to the national population of engineering students, women are overrepresented (in the analytical sample 35% are women, compared with 21% women nationally). The average starting salary is $63,709, SD = $21,370 (Table 1). There are n = 559 respondents. All of the CS graduates in the study were awarded degrees from engineering schools.¶

Measures.

Following prior literature, the dependent variable is the log of self-reported annual salary (see SI Appendix, Fig. S1 for salary distributions). We asked respondents to self-identify by sex and report self-identified sex in the results. To assess individual beliefs about one’s technical ability we measure ESE, a five-item validated measure on a five-point scale (0 = “not confident” to 4 = “extremely confident,” alpha = 0.87; SI Appendix, section S1). Participants were asked, “How confident are you in your ability to do each of the following at this time?”: 1) design a new product or project to meet specified requirements; 2) conduct experiments, build prototypes, or construct mathematical models to develop or evaluate a design; 3) develop and integrate component subsystems to build a complete system or product; 4) analyze the operation or functional performance of a complete system; and 5) troubleshoot a failure of a technical component or system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Byers, Helen Chen, Kai-Jun Chew, Qu Jin, and Mark Schar for their contributions to the launch of the EMS study, as well as our project liaisons at the 27 EMS schools. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their critical comments that led to an improved manuscript, Francis (Frank) Flynn for his consultancy on methods, and Anita Rollins for her editing support. The EMS study was conducted with funding from NSF Grant/Award 1636442 and DUE-1125457. The research reported here was supported in part by the Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education, through Grant R305B140009 to the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute, the US Department of Education, or the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*In the United States, women graduating with STEM degrees have lower probabilities of first births early on after graduation and relatively higher probabilities in their mid to late 30s compared to women graduating in other fields (46, 47).

†We have information regarding the salaries of the first jobs the full sample had after graduation. For a subset (n = 460) we also know the type of initial job they entered (for those whose first job was their current job).

‡On the EMS 1.0 survey prior to graduating, students were asked about their intent to work in an engineering/CS job (see SI Appendix, section S1). Women had lower intentions of entering engineering jobs than men (t statistic = 2.55), but we found no statistically significant difference by sex once ESE was taken into account. This suggests the effect of self-efficacy on salaries is partly explained by its effects on intentions to enter and then actual entry into engineering and CS jobs.

§Iterative path analyses were performed using seemingly unrelated regression, sureg models in Stata 14. All pathways with a theoretical basis were tested, and support for the following pathways were found: ESE → Engineering Intentions → CS/Engineering job → Salary; ESE → Engineering Intentions → Salary; ESE → Salary; Female → ESE.

¶There were a total of 7,197 individuals that completed the EMS 1.0 survey. For individuals to complete the survey questions for this analysis in EMS 3.0 they had to have graduated with an engineering or CS degree and be employed by the 3.0 administration. There were 10% of eligible respondents who did not indicate salary and thus are not included in the analyses. Those that did not provide salary information were statistically equivalent to those that did in terms of sex and ESE.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2010269117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Analyses.

To test hypothesis 1 we ran fixed effect ordinary least squares (OLS) models with robust SEs to address heteroscedasticity in Table 2. To test hypothesis 2 we ran a simple mediation model to assess the indirect effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between sex and salary (34) as described in Eqs. 1–3. To inspect the specific indirect effect of self-efficacy controlling for the two alternative mediators, sex, and the other covariates we ran the parallel multiple mediation model (35) as shown in Fig. 2. We used 1,000 bootstrapped iterations to compute a bias corrected 95% CI for the specific indirect effects.

Data Availability.

A subset of anonymized data and code used to test hypotheses 1 and 2 are available on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/zqwfa/).

References

- 1.Petersen T., Morgan L. A., Separate and unequal: Occupation-establishment sex segregation and the gender wage gap. Am. J. Sociol. 101, 329–365 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau F. D., Kahn L. M., The gender pay gap: Have women gone as far as they can? Acad. Manage. Perspect. 21, 7–23 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbett C., Hill C., Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing (American Association of University Women, Washington, DC, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochanski J., Ledford G., “How to keep me”—Retaining technical professionals. Res. Technol. Manag. 44, 31–38 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass J. L., Sassler S., Levitte Y., Michelmore K. M., What’s so special about STEM? A comparison of women’s retention in STEM and professional occupations. Soc. Forces 92, 723–756 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunt J., Why do women leave science and engineering? Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 69, 199–226 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estes S. B., Glass J. L., Job changes following childbirth. Work Occup. 23, 405–436 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine , Rising above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future (National Academies Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sassler S., Glass J., Levitte Y., Michelmore K. M., The missing women in STEM? Assessing gender differentials in the factors associated with transition to first jobs. Soc. Sci. Res. 63, 192–208 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fayer S., Lacey A., Watson A., STEM Occupations: Past, present, and future (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, DC, 2017).

- 11.Prokos A., Padavic I., An examination of competing explanations for the pay gap among scientists and engineers. Gend. Soc. 19, 523–543 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceci S. J., Williams W. M., Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3157–3162 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Y., Shauman K. A., Women in Science: Career Processes and Outcomes (Harvard University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shauman K. A., Gender differences in the early employment outcomes of STEM doctorates. Soc. Sci. 6, 1–26 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abendroth A. K., Melzer S., Kalev A., Tomaskovic-Devey D., Women at work: Women’s access to power and the gender earnings gap. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 70, 190–222 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reskin B. F., “Employment discrimination and its remedies” in Sourcebook of Labor Markets, Berg I., Kalleberg A. L., Eds. (Plenum Studies in Work and Industry, Springer, 2001), pp. 567–599. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotter D. A., Hermsen J. M., Ovadia S., Vanneman R., The glass ceiling effect. Soc. Forces 80, 655–681 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fouad N. A., Singh R., Stemming the tide: Why women leave engineering. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/NSF_Stemming%20the%20Tide%20Why%20Women%20Leave%20Engineering.pdf. Accessed 13 September 2018.

- 19.Cech E., Rubineau B., Silbey S., Seron C., Professional role confidence and gendered persistence in engineering. Am. Sociol. Rev. 76, 641–666 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correll S. J., Constraints into preferences: Gender, status, and emerging career aspirations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 69, 93–113 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rittmayer A. D., Beier M. E., Self-efficacy in STEM. http://aweonline.org/arp_selfefficacy_overview_122208.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2018.

- 22.Sadker M., Sadker D., Failing at Fairness: How America’s Schools Cheat Girls (Scribner, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charles M., Bradley K., Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. Am. J. Sociol. 114, 924–976 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridgeway C. L., Framed before we know it: How gender shapes social relations. Gend. Soc. 23, 145–160 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss-Racusin C. A., Dovidio J. F., Brescoll V. L., Graham M. J., Handelsman J., Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16474–16479 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babcock L., Laschever S., Women Don’t Ask: Negotiation and the Gender Divide (Princeton University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Doerr L., Alegria S., Fealing K. H., Fitzpatrick D., Tomaskovic-Devey D., Gender pay gaps in U.S. federal science agencies: An organizational approach. Am. J. Sociol. 125, 534–576 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reskin B. F., Roos P. A., Job Queues, Gender Queues: Explaining Women’s Inroads into Male Occupations (Temple University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez R. M., Mors M. L., Competing for jobs: Labor queues and gender sorting in the hiring process. Soc. Sci. Res. 37, 1061–1080 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Killewald A., Gough M., Does specialization explain marriage penalties and premiums? Am. Sociol. Rev. 78, 477–502 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Townsend N. W., The Package Deal: Marraige, Work and Fatherhood in Men’s Lives (Temple University Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thébaud S., Business as Plan B: Institutional foundations of gender inequality in entrepreneurship across 24 industrialized countries. Adm. Sci. Q. 60, 671–711 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.England P., The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gend. Soc. 24, 149–166 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron R. M., Kenny D. A., The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes A. F., Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisgram E. S., Diekman A. B., Making STEM “family friendly”: The impact of perceiving science careers as family-compatible. Soc. Sci. 6, 1–19 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferriman K., Lubinski D., Benbow C. P., Work preferences, life values, and personal views of top math/science graduate students and the profoundly gifted: Developmental changes and gender differences during emerging adulthood and parenthood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 517–532 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Offer S., Schneider B., Revisiting the gender gap in time-use patterns: Multitasking and well-being among mothers and fathers in dual-earner families. Am. Sociol. Rev. 76, 809–833 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertrand M., Goldin C., Katz L. F., Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2, 228–255 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matz R. L., et al. , Patterns of gendered performance differences in large introductory courses at five research universities. AERA Open 3, 1–12 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Y. J., Gender disparity in STEM disciplines: A study of faculty attrition and turnover intentions. Res. High. Educ. 49, 607–624 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Funk C., Parker K., Women and men in STEM often at odds over workplace equity. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/01/09/women-and-men-in-stem-often-at-odds-over-workplace-equity/. Accessed 14 March 2019.

- 43.Brenner M. H., Lockwood H. C., Salary as a predictor of salary: A 20-year study. J. Appl. Psychol. 49, 295–298 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall R. M., Sandler B. R., The classroom climate: A chilly one for women? (Association of American Colleges, 1982).

- 45.Kusimo A. C., Thompson M. E., Atwood S. A., Sheppard S., Effects of research and internship experiences on engineering task self-efficacy on engineering students through an intersectional lens. https://www.asee.org/public/conferences/106/papers/23814/download. Accessed 1 April 2020.

- 46.Michelmore K., Musick K., Fertility patterns of college graduates by field of study, US women born 1960-79. Popul. Stud. 68, 359–374 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cech E. A., Blair-Loy M., The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 4182–4187 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To test hypothesis 1 we ran fixed effect ordinary least squares (OLS) models with robust SEs to address heteroscedasticity in Table 2. To test hypothesis 2 we ran a simple mediation model to assess the indirect effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between sex and salary (34) as described in Eqs. 1–3. To inspect the specific indirect effect of self-efficacy controlling for the two alternative mediators, sex, and the other covariates we ran the parallel multiple mediation model (35) as shown in Fig. 2. We used 1,000 bootstrapped iterations to compute a bias corrected 95% CI for the specific indirect effects.

A subset of anonymized data and code used to test hypotheses 1 and 2 are available on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/zqwfa/).