Significance

Scrub typhus is a neglected tropical disease caused by the bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi. Although O. tsutsugamushi is an emerging public health threat, its pathogenic mechanisms remain markedly understudied. Bacterial pathogens subvert host actin dynamics by encoding guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) as effector proteins, which activate cellular Rho GTPases. Here, we identify a GEF domain within an O. tsutsugamushi protein that activates the host GTPase Rac1. While the overall shape of the GEF is similar to that of other bacterial effectors, the primary sequence, topology, and catalytic mechanism are completely distinct, suggesting convergent evolution. Our studies reveal a cryptic GEF domain encoded by O. tsutsugamushi and provide the groundwork to probe the role of cytoskeletal modulation in this neglected pathogen.

Keywords: Orientia tsutsugamushi, X-ray crystallography, guanine nucleotide exchange factor, scrub typhus, Rac1

Abstract

Rho family GTPases regulate an array of cellular processes and are often modulated by pathogens to promote infection. Here, we identify a cryptic guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domain in the OtDUB protein encoded by the pathogenic bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi. A proteomics-based OtDUB interaction screen identified numerous potential host interactors, including the Rho GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42. We discovered a domain in OtDUB with Rac1/Cdc42 GEF activity (OtDUBGEF), with higher activity toward Rac1 in vitro. While this GEF bears no obvious sequence similarity to known GEFs, crystal structures of OtDUBGEF alone (3.0 Å) and complexed with Rac1 (1.7 Å) reveal striking convergent evolution, with a unique topology, on a V-shaped bacterial GEF fold shared with other bacterial GEF domains. Structure-guided mutational analyses identified residues critical for activity and a mechanism for nucleotide displacement. Ectopic expression of OtDUB activates Rac1 preferentially in cells, and expression of the OtDUBGEF alone alters cell morphology. Cumulatively, this work reveals a bacterial GEF within the multifunctional OtDUB that co-opts host Rac1 signaling to induce changes in cytoskeletal structure.

The Ras homologous (Rho) family of GTPases is part of the Ras superfamily of small G proteins. Rho family GTPases are molecular switches that control intracellular actin dynamics and regulate a diverse array of cellular processes from cytokinesis to cell migration and wound healing (1–3). These small ∼21-kDa proteins are highly conserved in all eukaryotes, with three founding family members that have been extensively studied: Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA. Each Rho family GTPase exerts specific effects on the actin cytoskeleton, and constitutive activation of each protein leads to characteristic cellular phenotypes.

The signaling activity of a GTPase is controlled by its bound nucleotide. When GDP is bound, the GTPase is in the “inactive” state, and loading of a GTP promotes the “active” conformation of the G protein. Interaction with downstream effector proteins and subsequent actin reorganization only occurs when the GTPase is in the GTP-bound active state. The intrinsic nucleotide exchange (GDP to GTP) and hydrolysis (GTP to GDP) rates of Rho family GTPases alone are slow. Nucleotide exchange occurs on the order of 1.5 per hour (4, 5), and the intrinsic hydrolysis rate is ∼0.15 per min (6). Rapid regulation of GTPases, therefore, is controlled by two classes of proteins that either switch them “on” or “off”: guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) promote the dissociation of GDP and allow loading with GTP, and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) accelerate the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis by the G protein.

Bacterial pathogens such as certain species of Salmonella, Shigella and enteropathic Escherichia coli, encode and secrete effector proteins that modulate small GTPases to benefit the bacterium during infection. For instance, the Shigella flexineri IpgB2 GEF protein activates RhoA and causes characteristic membrane ruffles that are critical for Shigella invasion of the host cell (7). Bacterial effector GEFs belong to either the WxxxE family (named for a conserved motif important for folding and structural integrity) or the SopE family (SopE, SopE2, and BopE). These bacterial effectors share no sequence or structural homology to eukaryotic Rho GEFs, which predominantly belong to the Dbl homology (DH) family of GEFs that adopt a six-helix bundle with an elongated, kinked “chaise lounge” fold (8, 9). Rather, bacterial effector GEFs adopt a characteristic compact V-shaped fold, yet activate the Rho GTPases via the same contact regions in the GTPases that are crucial for nucleotide exchange by DH-family GEFs (10). While substantial effort has been exerted in detailing the molecular determinants of bacterial GEF activities and specificities, no bacterial effector GEFs have been identified outside of the WxxxE or SopE-like families.

Recently, we identified and characterized a putative effector protein, OtDUB, from the obligate intracellular bacterium that causes scrub typhus, Orientia tsutsugamushi. Despite extensive characterization of the OtDUB deubiquitylase (DUB) domain (residues 1–259), the function of the extensive C-terminal region, encompassing more than 1,000 amino acids, remained elusive (11). Here, we report that OtDUB encodes a GEF domain, OtDUBGEF. Using biochemical, structural, and cellular methods, we demonstrate that OtDUBGEF predominantly activates Rac1 in vitro and in cell culture. While the primary sequence of OtDUBGEF is unrelated to WxxxE or SopE GEFs, the OtDUBGEF crystal structure reveals a similar V-shaped fold despite an entirely different topological and helical arrangement, suggesting convergent evolution. We further determined the OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex crystal structure and demonstrate that OtDUBGEF interacts with Rac1 at key common loci in the GTPase. The complex structure also suggested a distinct mechanism for GDP displacement, unique among all GEFs characterized to date. Our work reveals that O. tsutsugamushi has evolved a GEF domain that expands the molecular repertoire of bacterial effectors and suggests a critical function for OtDUB in regulating Rac1 to benefit the pathogen during infection.

Results

The OtDUB C-Terminal Segment Is Toxic in Yeast and Interacts with GTPases.

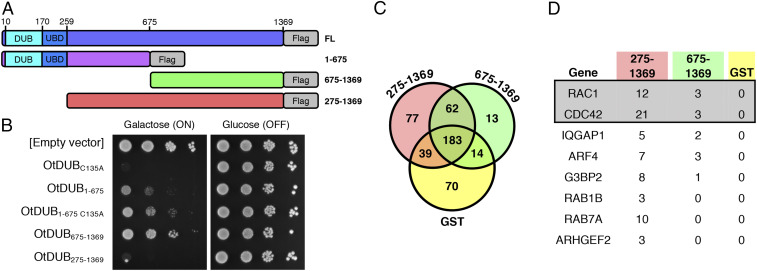

The OtDUB N-terminal region contains an active DUB and a high-affinity ubiquitin binding domain (UBD) within the first 259 residues (11). However, the remainder of the 1,369-residue protein is devoid of any computationally predicted domains. To examine how the OtDUB might affect eukaryotic cells, we first generated a series of truncations (Fig. 1A) and expressed the proteins in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Fig. 1B). Remarkably, expression of the full-length protein caused a complete block to growth even if the DUB was inactivated by mutation of the catalytic cysteine, C135A (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Expression of a fragment excluding the N-terminal DUB and UBD domains (OtDUB275–1369) also exhibited severe toxicity in yeast, but toxicity was no longer observed with the shorter OtDUB675–1369. The OtDUB1–675 truncation caused a lesser but still substantial growth deficit that was partially DUB dependent. These data suggest that a region within residues 275–1369 is the principal source of toxicity when expressed in yeast, but in the absence of this toxic domain, an additional DUB-dependent growth defect is uncovered.

Fig. 1.

OtDUB275–1369 is toxic in yeast and binds multiple proteins in HeLa cell lysates. (A) Cartoon diagram of various OtDUB fragments used for ectopic expression in yeast, mammalian cell cultures, and bacteria. (B) Growth of W303 yeast expressing various OtDUB fragments from the galactose-inducible promoter in p416GAL1. Yeast cultures were serially diluted in 10-fold steps and spotted on SD lacking uracil containing either galactose or glucose as the carbon source and grown for 3 d at 30 °C. (C) Venn diagram of total proteins identified between GST, OtDUB275–1369, and OtDUB675–1369. (D) Candidate interactors of indicated OtDUB fragments from LC-MS/MS. Total peptide counts are shown.

To determine if specific human host proteins bind the OtDUB “toxic region,” we isolated proteins from HeLa cell lysates that specifically bound glutathione-S-transferease (GST)–tagged OtDUB fragments and identified them using liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C and SI Materials and Methods). We identified several proteins that bound uniquely to GST-OtDUB275–1369 and not to GST-OtDUB675–1369 or the GST protein control (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Table S1). Notably, several small GTPases, such as Rac1 and Cdc42, and proteins of related functions were significantly enriched in the GST-OtDUB275–1369–bound sample compared to the GST-OtDUB675–1369 and GST controls (Fig. 1D). We focused on the small GTPases as there are numerous examples of pathogens hijacking GTPase signaling (12, 13).

Identification of GTPase-Binding and GEF Activity in OtDUB.

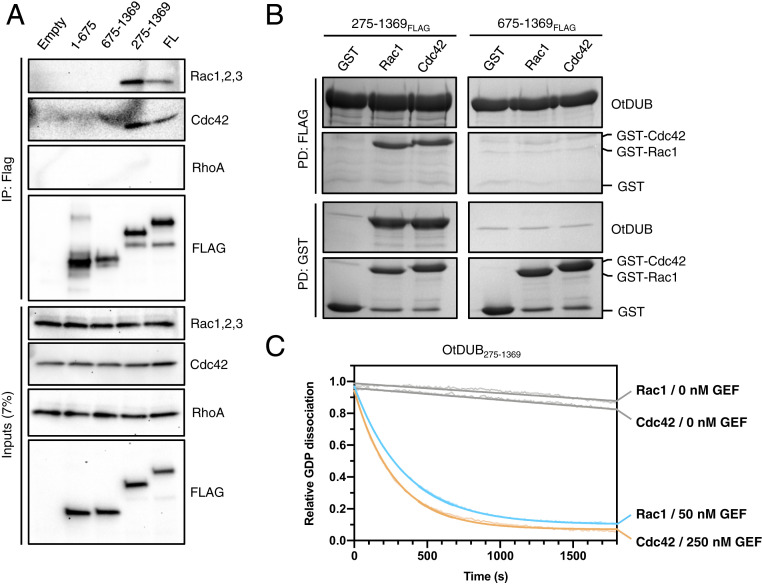

We carried out coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays using lysates of HeLa cells ectopically expressing several OtDUB fragments to verify the putative interactions identified by mass spectrometry. Flag-tagged OtDUB fragments were immunoprecipitated following incubation of whole cell lysates, and bound proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotted for Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA. These co-IP experiments confirmed that full-length (FL) OtDUB and OtDUB275–1369 bound Rac1 and Cdc42 but not RhoA (Fig. 2A). Further truncations (OtDUB1–675 and OtDUB675–1369) abolished the interaction. To demonstrate that this association does not require other cellular components, we performed direct binding assays between purified E. coli-expressed recombinant OtDUB fragments and recombinant GST-tagged Rac1 or Cdc42. In agreement with the co-IP results with HeLa cell lysates, OtDUB275–1369-Flag bound to both Rac1 and Cdc42 in anti-Flag immunoprecipitation assays, whereas OtDUB675–1369-Flag did not. The reciprocal GST pulldowns produced analogous results (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

OtDUB binds Rac1 and Cdc42 and catalyzes nucleotide exchange in vitro. (A) Inputs and anti-Flag immunoprecipitates of lysates from HeLa cells ectopically expressing the indicated Flag-tagged OtDUB fragments. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for Rho GTPases (Rac1,2,3; Cdc42; RhoA). (B) FLAG (Upper) and reciprocal GST (Lower) pulldown experiments between purified recombinant FLAG-tagged OtDUB fragments and GST-tagged Rac1 or Cdc42. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. (C) Time course of the dissociation of BODIPY-GDP from Rac1 or Cdc42 in the presence of OtDUB275–1369 (0, 50, or 250 nM) as measured by loss of BODIPY-GDP fluorescence. Excitation and emission wavelength were 488 nm and 535 nm, respectively.

GAPs and GEFs are the most common binding partners for GTPases. Several observations suggested that the OtDUB fragment might harbor GEF activity. First, certain intracellular bacterial pathogens encode GEFs to subvert GTPase signaling and alter actin networks during infection (14). Additionally, the preceding pulldowns required EDTA, a condition that promotes nucleotide unloading and enhances GEF:GTPase interactions (15).

To test whether OtDUB has GEF activity, we measured the rate of dissociation of a fluorescent GDP analog (BODIPY-GDP) from Rac1 and Cdc42 (16). BODIPY-GDP only fluoresces strongly when bound to protein. In the absence of OtDUB, Rac1 and Cdc42 released very little BODIPY-GDP (Fig. 2C). In contrast, OtDUB275–1369 (50 nM) greatly accelerated nucleotide dissociation from Rac1. The same fragment also promoted GDP release from Cdc42, albeit less efficiently, requiring five times more OtDUB (250 nM) to achieve similar levels of dissociation. In line with our initial binding studies, OtDUB275–1369 did not catalyze GDP dissociation from RhoA, and the shorter OtDUB675–1369 fragment displayed no exchange activity with Rac1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Together, these data indicate that OtDUB275–1369 binds to and promotes nucleotide exchange on both Rac1 and Cdc42.

Determination of a Minimal, GTPase-Binding OtDUBGEF Domain.

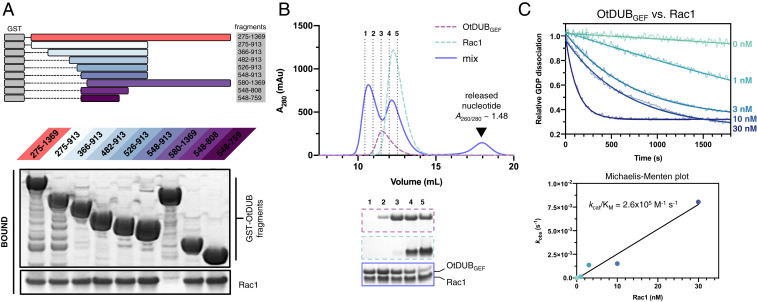

Bacterial GEFs in the WxxxE or SopE families exclusively target Rho GTPases yet are divergent in both sequence and structure from all eukaryotic Rho GEFs. Intriguingly, no region of the OtDUB protein sequence aligns to WxxxE or SopE sequences nor to any eukaryotic GEF sequence. Hence, we employed a truncation mapping strategy to further define the boundaries of a potential GEF domain in OtDUB. Guided by secondary structure predictions, we generated nine OtDUB constructs and tested them for Rac1 binding in an in vitro GST pulldown assay (Fig. 3A). Consistent with our co-IP results, the ∼1,000-residue (OtDUB275–1369) fragment strongly associated with Rac1. Neither C-terminal truncation (275–913) nor N-terminal truncations up to residue 548 reduced binding to Rac1; however, N-terminal truncation to residue 580 abolished binding. Further truncation from the C terminus revealed a minimal, ∼200-residue fragment (residues 548–759, hereafter referred to as OtDUBGEF) that retained full binding to Rac1.

Fig. 3.

A 200-residue OtDUB subdomain sufficient for binding Rac1. (A) OtDUB truncations used for mapping studies (Upper) and GST pulldown experiment using GST-OtDUB fragments as bait and Rac1 as prey (Lower). Gel was stained with Coomassie Blue. N-terminal truncation to residue 580 abolished binding, whereas the 548–759 fragment (OtDUBGEF domain) retained full binding capacity. (B) SEC of OtDUBGEF:Rac1 mixtures demonstrates stable complex formation (Upper). Column fractions were evaluated by SDS-PAGE and protein staining (Lower). (C) Time course of the dissociation of BODIPY-GDP from Rac1 in the presence of increasing amounts of OtDUBGEF (residues 548–759). Raw fluorescence curves were fit to a single exponential decay (Upper), and initial rates were plotted against Rac1 concentration (Lower). Linear fit of the initial velocities yielded a kcat/KM of 2.6 ± 0.3 × 105 M−1·s−1.

We employed size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to confirm that OtDUBGEF behaved well in solution and formed a stable complex with Rac1. Indeed, free OtDUBGEF eluted as a monodisperse peak, and its mixture with Rac1 resulted in coelution of both proteins at the expected volume for a 1:1 complex (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, another new peak appeared in the mixture fractionation at an elution volume corresponding to that of a small molecule; the high A260/280 ratio of this peak (∼1.5) suggested it represents released nucleotide that had copurified with Rac1. Similar SEC profiles were obtained for Cdc42 (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 A and B), demonstrating stable complex formation. We used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to quantify the binding affinity of OtDUBGEF toward Rac1 or Cdc42 (for details, see SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). The apparent dissociation constant (Kd, app) between OtDUBGEF and Rac1 is ∼5 μM, similar to those of other GEF:GTPase pairs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C) (17–19). The measured Kd, app for Cdc42 is ∼16 µΜ. Of note, WT GTPases with copurified nucleotides were used for ITC analysis, meaning the measured Kd, app for Rac1 and Cdc42 is a result of multiple processes (GEF:GTPase binding, nucleotide release and rebinding, and GTP hydrolysis); other factors such as subcellular localization or effector protein recruitment may also dictate GTPase specificity. Nevertheless, the threefold difference in apparent affinities may partially explain the weaker activation of Cdc42 by OtDUBGEF.

Finally, to ensure that the OtDUBGEF fragment fully accounts for catalytic activity, we tested various concentrations of this fragment for GEF activity against Rac1. In agreement with results from the pulldown assay, OtDUBGEF catalyzed GDP dissociation from Rac1 at all concentrations tested (Fig. 3C). Extraction of initial dissociation rates from this titration resulted in a catalytic efficiency of kcat/KM = 2.6 × 105 M−1·s−1, comparable in magnitude to SopE acting on Rac1 (5.0 × 105 M−1·s−1) (20). In contrast, OtDUBGEF was a relatively poor GEF against Cdc42, with a catalytic efficiency ∼15-fold worse than that for Rac1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E). Together, our in vitro findings demonstrate that the ∼200-residue OtDUBGEF fragment is sufficient to promote nucleotide exchange in two different Rho GTPases. The remainder of our studies focused solely on Rac1 because of the clear preference of OtDUBGEF for this GTPase.

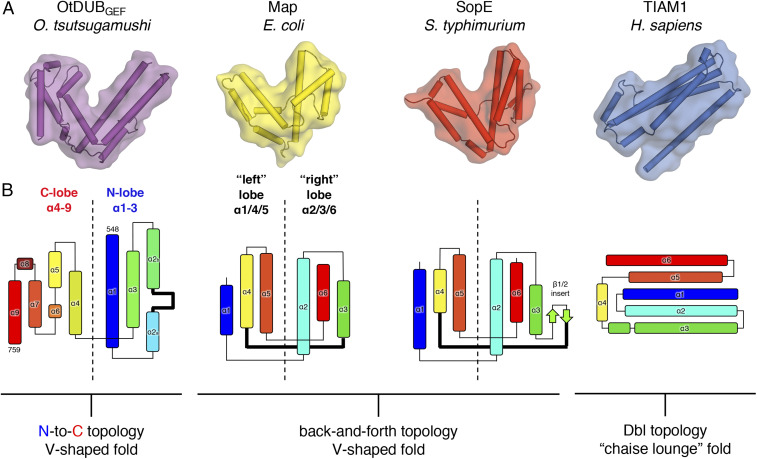

Crystal Structure of OtDUBGEF.

All prokaryotic GEF effectors with available structures diverge from the most common eukaryotic Rho GEF family, the Dbl-homology (DH) GEFs, which typically adopt an extended helical bundle, or “chaise lounge” fold (9). We crystallized OtDUBGEF (residues 548–759 of OtDUB) in its apo form and determined the structure to 3.0-Å resolution (Table 1). The structure reveals that OtDUBGEF is composed exclusively of alpha helices with intervening linkers (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) and adopts the familiar V-shaped fold seen in WxxxE and SopE GEFs. Despite their structural similarity at the level of the overall protein fold, the topology of OtDUBGEF is very distinct. One conserved feature of all previously resolved bacterial effector GEFs is their shared “back-and-forth” topology of helices (14). In SopE and Map, for example, α1/4/5 form the respective “left” lobes, and α2/3/6 form the “right” lobes of both proteins (Fig. 4 B, Center). By contrast, OtDUBGEF splits sequentially into an N-terminal lobe (α1–3) and a C-terminal lobe (α4–9), with only a single “crossing” of the polypeptide chain between lobes (Fig. 4B). The divergent topology of OtDUBGEF explains why primary sequence alignment to the WxxxE or SopE GEFs was impossible prior to solving the structure, despite having related functions. Notably, the “catalytic loops” present in the WxxxE and SopE families (Fig. 4B, bolded lines between α3 and α4) are required for nucleotide exchange (10), but the crossover loop between α3 and α4 of OtDUBGEF is not on the GTPase-interacting face of the enzyme (see below) owing to its unrelated topology. The apo structure therefore suggests that OtDUBGEF has evolved a different structural motif to dissociate nucleotide (discussed in detail below). The striking differences in topology and sequence for a common fold strongly indicates convergent evolution between OtDUBGEF and the SopE /WxxxE families of GEFs.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| OtDUBGEF apo | OtDUBGEF:Rac1 | |

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P63 | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c, Å | 110.53, 110.53, 251.24 | 50.06, 54.16, 94.00 |

| α, β, γ, ° | 90, 90, 120 | 83.37, 76.34, 62.52 |

| Resolution, Å | 3.0 (3.06–3.00)* | 1.7 (1.73–1.70) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.069 (1.610) | 0.033 (0.644) |

| I/σI | 19.7 (0.8) | 21.0 (1.0) |

| Completeness, % | 99.6 (96.7) | 81.7 (79.5) |

| CC1/2 | 0.997 (0.372) | 0.996 (0.295) |

| Redundancy | 8.4 (7.3) | 1.6 (1.6) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution, Å | 47.9–3.0 | 48.1–1.7 |

| No. of reflections | 37,727 (3,645) | 91,794 (8,930) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.19/0.24 (0.22/0.26) | 0.18/0.22 (0.20/0.24) |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 10,288 | 6,266 |

| Ligand/ion | 1 | 1 |

| Water | 1 | 313 |

| B-factors, Å2 | ||

| Protein | 88.9 | 28.0 |

| Ligand/ion | 91.7 | 67.9 |

| Water | 77.1 | 38.0 |

| rms deviations | ||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.016 | 0.018 |

| Bond angles, ° | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Ramachandran statistics, % | ||

| Favored | 99.0 | 98.9 |

| Allowed | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Outlier | 0.0 | 0.0 |

One crystal for each dataset was used for data collection and structure determination.

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Fig. 4.

Crystal structure of the apo OtDUBGEF domain reveals a unique topology. (A) Overall structural comparison of apo OtDUBGEF and other Rho GEFs: Map (PDB ID code: 3GCG), SopE (PDB ID code: 1GZS), TIAM1 (PDB ID code: 1FOE). All structures shown with helices as cylinders and transparent surface. (B) Topology diagrams of the same GEFs color-ramped from N terminus (blue) to C terminus (red) to highlight the unique topology of OtDUBGEF. Helices are shown as rectangles, beta strands are shown as arrows, and loop regions are shown as lines.

Crystal Structure of the OtDUBGEF:Rac1 Complex.

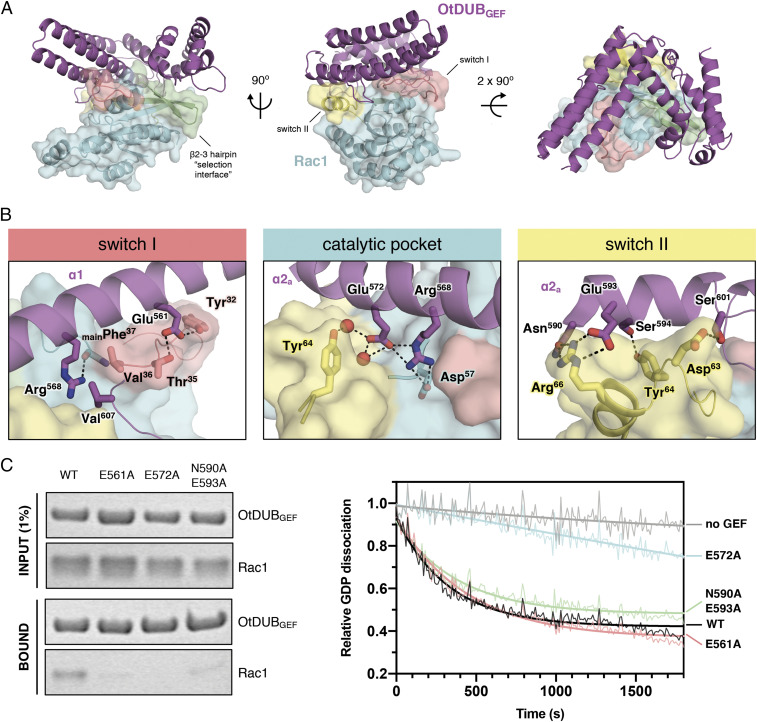

To gain insight into the mechanism of Rac1 activation by OtDUBGEF, we determined a crystal structure of the OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex to 1.7-Å resolution (Fig. 5A and Table 1). OtDUBGEF does not undergo major conformational changes upon binding to Rac1, with overall rmsds ranging from 0.1 Å to 1.9 Å when compared to the six independent copies of the molecule found in the asymmetric unit of the apo crystal (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), suggesting a rigid structure evolved to be primed for interaction. Like other Rho GEFs, OtDUBGEF forms contacts with three key surfaces of the Rac1 GTPase: the switch I and II regions, residues near the nucleotide-binding cleft (the catalytic pocket), and the β2–3 hairpin “interswitch” region, burying a total surface area of more than 1,800 Å2 per molecule (Fig. 5A). Each interacting region is described in detail below.

Fig. 5.

Biochemical function and structure of the OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex. (A) Three orthogonal views of the complex with OtDUBGEF in purple and Rac1 in cyan. Switch I and II loops are in salmon and yellow, respectively, and the β2–3 hairpin selectivity interface is green. (B) Close-up views of each key interface between OtDUBGEF and Rac1 showing selected residues, with hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions shown as dashes and water molecules as red spheres. (C) GST pulldown assays (Left) of GST-OtDUBGEF (WT or charge-neutralizing mutations at each interface) incubated with Rac1 and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. Corresponding BODIPY-GDP release assays are shown at Right.

The switch I interface (salmon in Fig. 5 B, Left) is composed of a hydrophobic pocket formed by OtDUBGEF-Phe564/Val607/Val612 that accommodates Rac1-Val36. This hydrophobic cleft is flanked on one side by OtDUBGEF-Arg568 interacting with the main chain carbonyl of Rac1-Phe37, and on the other by OtDUBGEF-Glu561 forming a polar network with Rac1-Thr35 and Tyr32. At the switch II interface (yellow in Fig. 5 B, Right), OtDUBGEF forms extensive electrostatic interactions, coordinating Rac1-Arg66 via OtDUBGEF-Asn590 and Glu593. Furthermore, OtDUBGEF residues Ser594, Ser601, and Glu603 form charged-polar interactions with Rac1 residues Tyr64, Asp63, and the backbone of Glu62, respectively. Finally, near the nucleotide-binding pocket, a network of ordered water molecules is coordinated by OtDUBGEF-Glu572, which interact with multiple Rac1 residues (Fig. 5 B, Center).

To confirm the importance of these residues, we mutated OtDUBGEF residues at each interface and tested these mutants for both binding and catalytic activities against Rac1. Compared to WT OtDUBGEF, both switch I (E561A) and switch II (N590A/E593A) mutants reduced apparent binding in the GST pulldown assay, whereas little defect in catalysis was observed (Fig. 4C). By contrast, mutation of the central catalytic residue (E572A) abrogated binding entirely and reduced GDP dissociation activity to background levels, highlighting the importance of this central residue for interaction with Rac1. This mutational analysis confirms that OtDUB harbors a bona fide GEF domain with a unique topology.

The OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex further revealed the structural basis for its selectivity among Rho-family GTPases. Previously, a “lock-and-key” mechanism for substrate selection has been proposed for discrimination between Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA (21, 22). In this model, complementary pairing of amino acids generates favorable interactions for target GTPases in the β2–3 hairpin “selectivity patch,” and steric hindrance precludes interaction with nontarget family members. For instance, where Rac1 and Cdc42 encode small amino acids, Ala3 and Thr3, respectively, RhoA places a bulky, charged Arg5 residue at the same position (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). In agreement with the dual specificity observed in the in vitro GEF assay, OtDUBGEF residues are compatible with both selectivity patches of Rac1 and Cdc42. In contrast, the bulky, charged amino acids of RhoA (Arg5 and Glu54) are predicted to clash with several rigid regions of OtDUBGEF (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B).

We next analyzed whether OtDUBGEF makes similar contacts with Rac1 when compared other bacterial GEFs and their cognate Rho-family GTPases: SopE and Cdc42 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID code: 1GZS), Map and Cdc42 (PDB ID code: 3GCG), and IpgB2 and RhoA (PDB ID code: 3LW8, complex A). Overall, the footprints of the bacterial effector GEFs and OtDUBGEF on their GTPases are very similar (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). However, comparison of the interactions made by WxxxE and SopE GEFs (hereafter referred to collectively as bacGEFs) and by OtDUBGEF revealed that the latter has distinct contacts with Rac1. Interactions with switch I are the most similar: Where bacGEFs use an invariant acidic Asp residue to make backbone contacts with Val36 and Thr38 (Rac1/Cdc42 numbering), OtDUBGEF positions Glu561 to interact with Rac1-Tyr32 and Thr35 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B, Left). Switch II interactions are slightly more diverse in bacGEFs, with SopE and Map using a Gln residue to make polar contacts with Asp65, and IpgB2 positioning an Asp sidechain to interact with Arg66 of RhoA. Here, OtDUBGEF coordinates Rac1-Arg66 with Asn590/Glu593 and interacts with Tyr64 instead of Asp65 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B, Right). Finally, WxxxE and SopE GEFs extrude flexible “catalytic loops” between α3 and α4 that rest in a cleft formed between switch I and switch II of the GTPase (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B, Center). These catalytic loops share some sequence similarity, requiring an Ala followed by a polar Asn/Gln residue to facilitate nucleotide exchange. Strikingly, the unique topology of OtDUBGEF necessarily precludes the existence of a homologous catalytic loop, suggesting that OtDUBGEF utilizes a distinct catalytic mechanism.

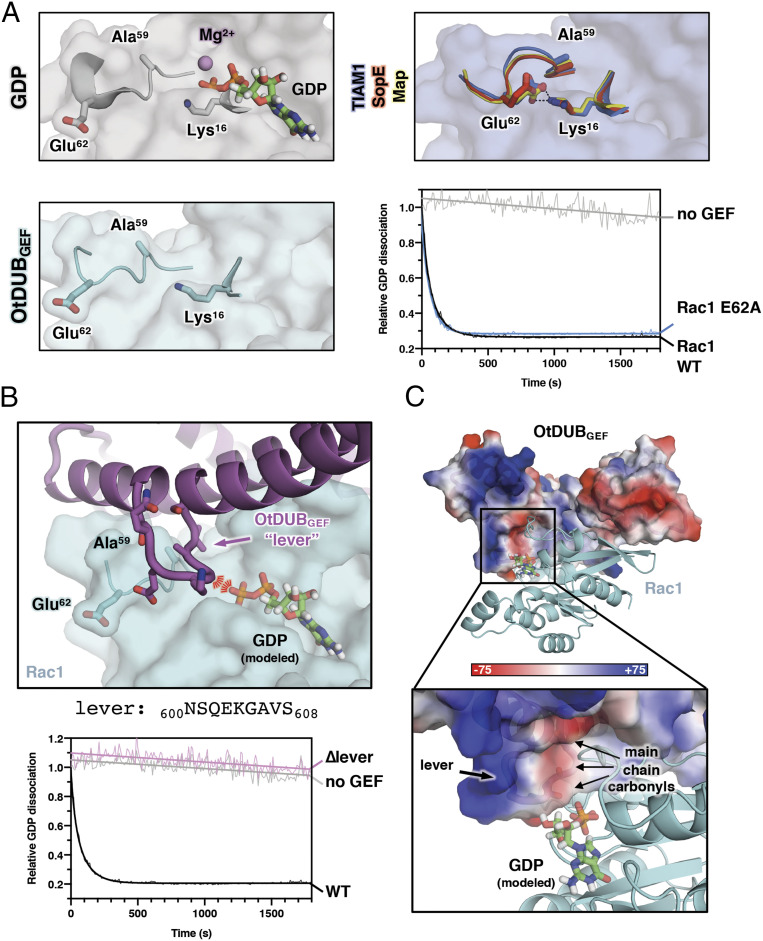

OtDUBGEF Utilizes a Carbonyl “Catalytic Lever” to Dissociate Nucleotide.

In all DH GEF:Rho GTPase structures, highly conserved and characteristic conformational changes in switch II are responsible for dissociation of GDP. For instance, the canonical GEF-bound structure of the TIAM1:Rac1 complex (PDB ID code: 1FOE, slate) reveals that the sidechains of Glu62 and Ala59 of Rac1 both rotate nearly 180° toward the nucleotide-binding cleft relative to their positions before GEF binding, i.e., in the GDP-bound state (PDB ID code: 5N6O, gray) (Fig. 6A). This allows Rac1-Glu62 to interact with Rac1-Lys16, competing for β-phosphate binding, and Rac1-Ala59 displaces Mg2+ in a hydrophobic pocket (Fig. 6A). Identical conformations are observed in all other bacterial GEF complex structures such as SopE:Cdc42 and Map:Cdc42, and interactions with their catalytic loops facilitate this conformational change (23, 24). Thus, all known Rho GEFs use a similar catalytic mechanism that drives the GTPase switch II region through a conserved set of main chain and side chain motions toward the bound GDP. Accordingly, mutation of Rac1-Glu62 abrogates dissociation activity for all Rho GEFs tested to date, as well as for most Ras and Ran GEFs (25).

Fig. 6.

OtDUBGEF utilizes a unique carbonyl “catalytic lever” to catalyze nucleotide exchange. (A) Close-up views of switch II in GDP-bound Rac1 (gray, PDB ID code: 5N6O), three overlaid GEF-bound structures (slate is TIAM1:Rac1, PDB ID code: 1FOE; red is SopE:Cdc42, PDB ID code: 1GZS; and yellow is Map:Cdc42, PDB ID code: 3GCG), and the OtDUBGEF-bound Rac1 structure (cyan). Unlike the three overlaid GEF-bound conformations, Glu62 in the OtDUBGEF-bound structure is most similar to that found in GDP-bound Rac1. GEFs have been removed for clarity, and switch I residues are shown as sticks. BODIPY-GDP exchange assay reveals that Glu62 is not required for efficient exchange catalyzed by OtDUBGEF. (B, Upper) A loop of OtDUBGEF that interrupts α2 acts as a “catalytic lever” to promote release of GDP. OtDUBGEF is shown as cartoon (purple), and Rac1 is shown as transparent surface (cyan). GDP (not present in our structure) is modeled based on PDB ID code 5N6O for reference. The steric clash and electrostatic repulsion are indicated by the red lines. (B, Lower) Nucleotide exchange assay reveals a strict requirement in the lever segment for exchange of BODIPY-GDP. (C) Calculated electrostatic surface potential map (unit kBT/e) shows high negative charge in the OtDUBGEF lever formed by a tricarbonyl motif at the vicinity of the diphosphate group of GDP.

Strikingly, the conformation of Rac1-Glu62 in our OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex positions the sidechain away from the nucleotide pocket and instead resembles the GDP-bound conformation (Fig. 6A). Our structure was obtained after nucleotide dissociation (Fig. 3C) and clearly shows no nucleotide present (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), suggesting that we captured the complex in a postexchange conformation despite the observed position of Rac1-Glu62. This discrepancy led us to hypothesize that Rac1-Glu62 would be dispensable for GDP dissociation by OtDUBGEF. Indeed, OtDUBGEF-catalyzed nucleotide dissociation was indistinguishable between WT and E62A Rac1 (Fig. 6A). There are exceptions to the dependence on Glu62 (or its equivalent), as in the case of the GEF domain of Rabex-5 and its GTPase Rab21, where Rabex-5 supplies an acidic residue in trans to catalyze exchange on Rab21 (26). However, to our knowledge OtDUBGEF is the only known example of a Rho-specific GEF whose catalytic mechanism does not rely on Glu62.

How does OtDUBGEF promote nucleotide exchange in the absence of a canonical catalytic loop? In addition to the unusual conformation of Glu62 in our complex structure, we also observed a short loop in OtDUBGEF (601SQEKGAVS608, hereafter referred to as the “catalytic lever”) that protrudes out of α2 near the canonical catalytic loop position (Fig. 6B). The deep projection of the OtDUBGEF lever into the nucleotide-binding cleft led us to hypothesize that this loop may be critical for nucleotide exchange. Deletion of the catalytic lever in OtDUBGEF completely abrogated nucleotide exchange activity compared to wild type in vitro (Fig. 6B). The compromised catalytic activity cannot be attributed to misfolding of the protein or to loss of binding Rac1 since the OtDUBGEF ∆lever protein was monodisperse and continued to form a complex with Rac1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Inspection of the electrostatic surface potential of the catalytic lever of OtDUBGEF near the nucleotide-binding cleft of Rac1 revealed significant negative charge formed not by side chains, but by three main chain carbonyls pointed toward the nucleotide-binding pocket (Fig. 6C). We propose that these polar carbonyl moieties are inserted in close proximity to the bound nucleotide and repulse the negatively charged phosphates of GDP, facilitating nucleotide exchange. The conformations of the catalytic lever in the OtDUBGEF apo and Rac1-complexed crystal structures are remarkably similar (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D, pairwise Cα rmsdlever = 0.04–0.25 Å when comparing the two independent copies of the levers in the complex crystal with the six independent copies in the apo crystal), suggesting the catalytic lever is rigid and primed for direct interaction with Rac1. The attribution of catalysis activity to the catalytic lever highlights a unique mechanism utilized by OtDUBGEF to promote nucleotide dissociation.

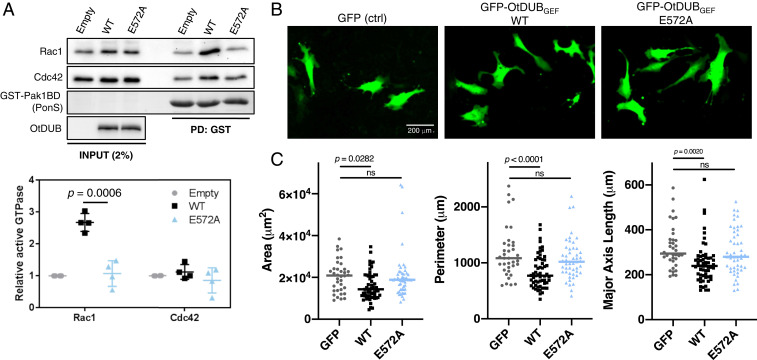

OtDUBGEF Specifically Activates Rac1 in Cells.

To complement these structural and in vitro activity results, we examined the state of Rac1 and Cdc42 in HeLa cells ectopically expressing OtDUBFL or the GEF impaired mutant OtDUBE572A. We utilized a resin-bound GST fusion of the p21-binding domain (PBD) of Pak1 to specifically enrich the active forms of Cdc42 and Rac1 (27). OtDUB-expressing cells exhibited a 2.7 ± 0.3-fold increase in activated Rac1 compared to control cells (Fig. 7A). Importantly, the E572A mutant, which abolished OtDUBGEF nucleotide exchange activity toward Rac1, no longer raised active Rac1 levels in cells above baseline levels. Consistent with the lower in vitro activity of OtDUBGEF on Cdc42 (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2E), there was no significant increase in the active Cdc42 when OtDUB was ectopically expressed (1.1 ± 0.2-fold increase). These data both validate that the Rho GTPase GEF activity is contained within the OtDUBGEF domain and show a clear preference for Rac1 over Cdc42 in cells.

Fig. 7.

OtDUBGEF specifically activates Rac1 and modulates cell morphology. (A) Lysates from HeLa cells carrying empty vector or plasmids expressing WT or E572A OtDUB were subjected to GST-Pak1PBD pulldowns to enrich active Rac1 and Cdc42. Representative experiment (Upper) from four independent experiments that were quantified (Lower) relative to input levels and the empty vector control. Bars represent mean and SD P value determined from a two-tailed unpaired Student t test. Outlier from Rac1 wild type (5.4-fold increase in activity) excluded one trial. Outlier was identified using Grubbs algorithm with alpha = 0.05. (B) Representative epifluorescence images of fibroblasts carrying the vector expressing only GFP or plasmids expressing WT or E572A OtDUBGEF. (C) Quantification of cell area, perimeter, and major axis length.

To examine possible downstream effects of OtDUBGEF-activated Rac1 on the actin cytoskeleton, we turned to a model cell line, mouse 3T3 fibroblasts. Ectopic expression of full-length OtDUB-GFP (WT or E572A) caused massive cell death and GFP signal could not be detected. In contrast, expression of a GFP fusion of the GEF domain alone was tolerated by fibroblasts and expression was readily detected (Fig. 7B). Expression of OtDUBGEF did not globally modulate filamentous actin structures, as revealed by phalloidin staining and confocal microscopy (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A).

Expression of OtDUBGEF leads to statistically significant cell morphology changes. Rac1 regulation of the actin cytoskeleton promotes cell edge protrusion, and Rac1 activity is required for cell spreading on adhesive surfaces in many cell types (28–30). Cells expressing the WT OtDUBGEF-GFP were slightly smaller, less elongated, and had fewer filopodial extensions compared to control cells expressing GFP alone (Fig. 7B). Quantification of cell shape metrics revealed that overall cell area, cell perimeter, and major axis length decreased upon expression of the OtDUBGEF-GFP (Fig. 7C). Critically, cells expressing the catalytically inactive OtDUBGEF-E572A-GFP mutant were not different from GFP control. Together, these data suggest that OtDUBGEF activity is responsible for the observed morphological phenotypes and that its GEF activity potentially regulates the host cytoskeletal machinery to produce distinct morphological defects.

Discussion

The results presented here uncover an unexpected GEF activity in the multidomain OtDUB protein from the pathogen O. tsutsugamushi and provide insight into our understanding of the regulation of Rho GTPases. The cryptic GEF domain harbors GEF activity toward both Rac1 and Cdc42, with a clear preference for Rac1 both in vitro and in living cells. High-resolution crystal structures of the OtDUBGEF domain alone and in complex with Rac1 reveal a GEF topology that nevertheless adopts a conserved V-shaped GEF fold. Importantly, OtDUBGEF utilizes a mechanism to activate Rho GTPases involving direct, steric exclusion of GDP and distinct molecular determinants.

The unique topology of OtDUBGEF compared to all other bacterial effector GEFs represents a unique solution to a common objective for bacterial intracellular pathogens, namely, the manipulation of host GTPases to promote the survival and proliferation of the pathogen. Sequence comparison of the OtDUBGEF domain against the nonredundant National Center for Biotechnology Information protein database revealed clear conservation only within the Orientia genus. Interestingly, a duplicated segment (residues 283–499) within the OtDUB protein itself shares 48% identity with the OtDUBGEF domain (residues 548–759; SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). This duplicated region does not have Rho GTPase GEF activity nor does it bind Rho GTPases (Fig. 2A) despite similarity at critical Rac1-interacting residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A); however, we cannot rule out that this region does not bind other small GTPases identified in our proteomics screen (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Table S1). Furthermore, the ortholog from Orientia chuto (OcDUB, WP_052694629.1) contains three regions with homology to OtDUBGEF: two regions (OcDUB426–641, 47% identity and OcDUB925–1137, 49% identity) that are mostly conserved at Rac1-interacting sites and one segment (OcDUB665–883, 37% identity) that is more weakly conserved (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). Further experiments will be required to determine whether OcDUB harbors a GEF activity similar to OtDUB.

To our knowledge, the nucleotide exchange mechanism employed by OtDUBGEF is unique among known GEFs. The role of Glu62 has been studied extensively by Gasper et al. (25); whereas DH/Dbl Rho GEFs (e.g., Dbs, TIAM1, and p190) and Cdc25 domain-containing Ras GEFs (e.g., Sos and Rap) are absolutely dependent on Glu62 for nucleotide exchange, Sec7-like Arf GEFs (e.g., Rabex-5 and Sec7) circumvent this requirement by supplying an acidic residue in trans (26, 31). Notably, OtDUBGEF exchange activity is independent of Glu62, and the structure does not implicate any nearby acidic residue from the GEF for interaction with Lys16, in contrast to Sec7-like GEFs. Instead, the catalytic lever of OtDUBGEF inserts directly into the nucleotide pocket, revealing an unusual steric mechanism to promote GDP unloading. From the level of protein topology to the mechanistic details of nucleotide exchange, OtDUBGEF is a fascinating example of convergent evolution and represents a unique solution for interaction with a highly conserved regulator of the host cytoskeleton, Rac1.

While it remains to be demonstrated that OtDUB is in fact a bona fide effector protein, the robust Rac1 activation in cultured cells further bolsters this possibility. The combination of the DUB, UBD, and GEF activities—all of which specifically interact with eukaryotic cellular signaling molecules that are absent from prokaryotic systems—strongly suggests that OtDUB is exposed to the host cellular milieu. We note that ectopic expression of OtDUB with inactivated DUB, UBD, and GEF domains (OtDUB-C135A, V203D, E572A) still causes complete growth inhibition in yeast, suggesting additional regions of unknown function in OtDUB that can also interfere with host physiology (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Due to a lack of early Rac1 activation during O. tsutsugamushi infection (32), it is unlikely that the OtDUBGEF acts in the same fashion as the SopE and SopE2 GEFs from Salmonella, which are secreted into the host cell cytoplasm to activate Rac1/Cdc42, inducing membrane ruffling and facilitating uptake of the bacterium (33). Rather, it is tempting to speculate that the OtDUBGEF activates Rac1 after the bacterium escapes the vacuolar compartment and accesses the cytoplasmic space, roughly 2 h postinfection (34). One potential indicator of Rac1 activation during postendosomal escape is the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway (35), a known downstream target of Rac1 (36–38). Additionally, IQGAP1, a downstream effector of Rac1/Cdc42, was found enriched in the OtDUB275–1369 mass spectrometry analysis (SI Appendix, Table S1). IQGAP1 is a scaffolding protein with numerous binding partners and roles (39) and is also required for efficient infection by Salmonella (40).

Cumulatively, the biochemical, bioinformatic, and structural data presented here demonstrate that a recently evolved GEF domain with a unique sequence, topology, and nucleotide-exchange mechanism exists in the O. tsutsugamushi scrub typhus pathogen. The characterization of nearly half a dozen distinct and evolutionarily unrelated GEF families in eukaryotes indicates that numerous protein folds can support guanine nucleotide exchange activity. The unique topology of OtDUBGEF further suggests that the sequence space of GEFs may be incompletely characterized. Finally, our work suggests that OtDUB GEF activity may be crucial for O. tsutsugamushi infection and opens the door for future investigations in this neglected pathogen.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction and Protein Purifications.

All plasmid constructs and proteins generated for in vitro assays and crystallization were expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells and purified by affinity chromatography. Details can be found in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Yeast Spot Assays.

Yeast were grown under standard conditions at 30 °C using yeast rich (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose or YPD) or minimal (SD) media (41). Isolated transformants carried p416GAL1-based plasmids (42) in the W303 (MHY2416) (43) S. cerevisiae background was grown overnight in SD lacking uracil (SD-URA) medium supplemented with casamino acids. Cultures were diluted in sterile water to 0.2 OD600 from which 10-fold dilutions were made. Diluted cultures were spotted onto SD-URA plates supplemented with either 2% glucose or 2% galactose. Plates were incubated at the indicated temperature for 3 d. Steady-state levels of each OtDUB polypeptide was verified by back diluting 2.5 OD units of SD-URA + 2% raffinose cultures into SD-URA + 2% galactose, growing for 4 h at 30 °C and processing 2.5 OD units by alkaline lysis for subsequent Western immunoblot analysis using anti-Flag antibodies.

OtDUB:Rho GTPases co-IPs.

HeLa cell pellets were collected 24 h after transfection and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, 2 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), cOmplete protease inhibitor tablet [Roche]) and incubated on ice for 30 min with intermittent vortexing. The insoluble fraction was then pelleted by centrifuging at 21,000 × g for 15 min. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) and normalized to 1 mg/mL with lysis buffer. IPs were carried out by rotating 850 μL of lysate with 15 μL of M2 anti-Flag resin (Sigma) at 4 °C for 4 h. The resin was washed three times with 0.5 mL of lysis buffer, followed by protein elution at 37 °C for 15 min with 50 μL of triple-Flag peptide elution buffer (0.4 mg/mL of peptide in lysis buffer). The eluent was isolated with a Quik-Spin Column (Bio-Rad), mixed with Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 3 min, and 25% was resolved by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Detailed procedures for immunoblotting can be found in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Active Rac1/Cdc42 Enrichment.

At 32 h posttransfection, the HeLa cell medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM to reduce the basal levels of active Rac1/Cdc42 (44). At 48 h posttransfection, cells were harvested and resuspended in Pak1PBD buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM PMSF, cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet [Roche]). Lysates were clarified, quantified, and normalized as above. Purified GST-Pak1PBD (20 μg) was added to 1 mL of 1.0 mg/mL lysates along with 15 μL of glutathione resin (ThermoFisher) and rotated for 90 min at 4 °C. Resin was washed three times with 0.5 mL of Pak1PBD buffer and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were boiled for 3 min, and 50% of eluted proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Detailed procedures for immunoblotting can be found in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

In Vitro Affinity Pulldown Assays.

For pulldown assays between GST-Rac1/Cdc42 and OtDUB-Flag polypeptides, protein combinations were diluted to 1 μM in binding buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% Triton X-100) to a final volume of 500 μL. After incubating at 37 °C for 30 min, the samples were spiked with 30-μL glutathione resin or M2-Flag resin and rotated for an additional 30 min at room temperature. Resin pellets were washed three times with binding buffer and eluted with Laemmli sample buffer or with 3xFlag peptide. For pulldown assays used to determine the minimal Rac1-interacting domain and validation point mutations in OtDUB, GST-tagged OtDUB fragments (20 μM) were mixed with Rac1 (60 µM) in binding buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM TCEP) to a final volume of 250 μL. Reactions were incubated with 200 μL of glutathione resin at 4 °C for 1 h. The beads were washed with 15 CV binding buffer and eluted with binding buffer supplemented with 10 mM reduced l-glutathione. Eluates were boiled and resolved by SDS/PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue.

BODIPY-GDP Nucleotide Exchange Assays.

GTPases at a final concentration of 10 μM were loaded with substoichiometric (1/4 [GTPase]) concentrations of GDP-BODIPY-FL (Thermo Scientific) in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), supplemented with 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to promote unloading of copurified nucleotide. Loading reactions were incubated for 1 h at 25 °C and then quenched by addition of MgCl2 to a final concentration of 25 mM. Exchange reactions were initiated by addition of a solution containing the OtDUB, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM GTP. Reactions were mixed rapidly, loaded into a multiwell plate, and real-time fluorescence was collected on a plate reader for 30 min at 25 °C, using excitation at 488 nm and emission at 535 nm (16).

SEC.

Each OtDUBGEF construct (75 μM) was mixed with the appropriate GTPase (150 μM) or diluted alone in a 500-μL reaction and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. Potential aggregates were removed by pelleting at 21,000 × g for 5 min prior to loading. Protein mixtures were injected into a Superdex 75 GL column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Peak fractions were identified by monitoring absorbance at both 280 and 260 nm, resolved by SDS/PAGE, and visualized with Coomassie Blue staining.

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystals of both apo OtDUBGEF and OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex were grown at 25 °C using the microbatch under-oil method (45). Various seeding methods were used to generate large, well-diffracting crystals, and crystals were cryo-protected by addition of crystallization buffer supplemented with 25% (vol/vol) glycerol before being flash frozen in liquid N2. Details on data collection and structure determination can be found in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Confocal Microscopy.

After spreading on coated coverslips for 24 h, mouse 3T3 (WT32) fibroblast cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in cytoskeleton buffer (10 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid [MES] pH 6.8, 138 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 320 mM sucrose), rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), permeabilized, blocked, and incubated with primary goat anti-GFP antibody (Rockland 600-101-215) at 4 °C overnight. The next morning, cells were incubated with secondary Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat antibody (Abcam ab150129) and phalloidin Atto 647N (Sigma-Aldrich 65906). After drying, coverslips were sealed using clear nail polish and imaged by epifluorescence on a microscope (model TE2000-S, Nikon) using a 20× objective, or with a 40× objective on a spinning disk confocal microscope (UltraVIEW VoX spinning disk confocal [Perkin-Elmer], Nikon Ti-E-Eclipse). CellProfiler (46) was used to detect and edit cell edges to compute all morphological metrics. For each condition, 36–58 cells were measured and an ordinary one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used to determine significant differences between groups. Further details can be found in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Titus Boggon (Yale University) for the Rac1 and Cdc42 template DNA, Jonathan Chernoff (Fox Chase Cancer Center) for the pGEXTK-Pak1 plasmid (Addgene #12217), and the W.M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory (Yale University) for mass spectrometry data collection and analysis. This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 AI116313 (to Y.X.); R01 GM046904 and R35 GM136325 (to M.H.); and R01 MH115939, R01 NS105640, and R21 NS112121 (to A.J.K.). Additional training support was provided by an NSF Fellowship DGE1122492 (to C.L.), NIH R01 MH115939-03S1 (to A.B.), and NIH F31 NS113511 (to J.B.). We are grateful to our host Igor Kourinov at the NE-CAT 24-ID-C beamline for diffraction data collection at the Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory. This work was supported by NE-CAT beamlines (P30 GM124165) at the APS (DE-AC02-06CH11357).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2018163117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB (ID codes 6X1H [OtDUBGEF apo] and 6X1G [OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex]).

References

- 1.Burridge K., Wennerberg K., Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell 116, 167–179 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe A. B., Hall A., Rho GTPases: Biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 247–269 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vetter I. R., Wittinghofer A., The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. 294, 1299–1304 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis M. J., et al. , RAC1P29S is a spontaneously activating cancer-associated GTPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 912–917 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang B., Zhang Y., Wang Z., Zheng Y., The role of Mg2+ cofactor in the guanine nucleotide exchange and GTP hydrolysis reactions of Rho family GTP-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25299–25307 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haeusler L. C., Blumenstein L., Stege P., Dvorsky R., Ahmadian M. R., Comparative functional analysis of the Rac GTPases. FEBS Lett. 555, 556–560 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alto N. M., et al. , Identification of a bacterial type III effector family with G protein mimicry functions. Cell 124, 133–145 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossman K. L., Der C. J., Sondek J., GEF means go: Turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 167–180 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worthylake D. K., Rossman K. L., Sondek J., Crystal structure of Rac1 in complex with the guanine nucleotide exchange region of Tiam1. 408, 682–688 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulgin R., et al. , Bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factors SopE-like and WxxxE effectors. Infect. Immun. 78, 1417–1425 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berk J. M., et al. , A deubiquitylase with an unusually high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain from the scrub typhus pathogen Orientia tsutsugamushi. Nat. Commun. 11, 2343 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popoff M. R., Bacterial factors exploit eukaryotic Rho GTPase signaling cascades to promote invasion and proliferation within their host. Small GTPases 5, e983863 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein M.-P., Müller M. P., Wandinger-Ness A., Bacterial pathogens commandeer Rab GTPases to establish intracellular niches. Traffic 13, 1565–1588 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orchard R. C., Alto N. M., Mimicking GEFs: A common theme for bacterial pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 10–18 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller M. P., Goody R. S., Molecular control of Rab activity by GEFs, GAPs and GDI. Small GTPases 9, 5–21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemsath L., Ahmadian M. R., Fluorescence approaches for monitoring interactions of Rho GTPases with nucleotides, regulators, and effectors. Methods 37, 173–182 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoebel S., Oesterlin L. K., Blankenfeldt W., Goody R. S., Itzen A., RabGDI displacement by DrrA from Legionella is a consequence of its guanine nucleotide exchange activity. Mol. Cell 36, 1060–1072 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdul Azeez K. R., Knapp S., Fernandes J. M. P., Klussmann E., Elkins J. M., The crystal structure of the RhoA-AKAP-Lbc DH-PH domain complex. Biochem. J. 464, 231–239 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klebe C., Prinz H., Wittinghofer A., Goody R. S., The kinetic mechanism of Ran–Nucleotide exchange catalyzed by RCC1. Biochemistry 34, 12543–12552 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friebel A., et al. , SopE and SopE2 from Salmonella typhimurium activate different sets of RhoGTPases of the host cell. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34035–34040 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnoub A. E., et al. , Molecular basis for Rac1 recognition by guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 1037–1041 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snyder J. T., et al. , Structural basis for the selective activation of Rho GTPases by Dbl exchange factors. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 468–475 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchwald G., et al. , Structural basis for the reversible activation of a Rho protein by the bacterial toxin SopE. EMBO J. 21, 3286–3295 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Z., et al. , Structural insights into host GTPase isoform selection by a family of bacterial GEF mimics. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 853–860 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasper R., Thomas C., Ahmadian M. R., Wittinghofer A., The role of the conserved switch II glutamate in guanine nucleotide exchange factor-mediated nucleotide exchange of GTP-binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 379, 51–63 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delprato A., Lambright D. G., Structural basis for Rab GTPase activation by VPS9 domain exchange factors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 406–412 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benard V., Bohl B. P., Bokoch G. M., Characterization of rac and cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13198–13204 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vidali L., Chen F., Cicchetti G., Ohta Y., Kwiatkowski D. J., Rac1-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts are motile and respond to platelet-derived growth factor. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2377–2390 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells C. M., Walmsley M., Ooi S., Tybulewicz V., Ridley A. J., Rac1-deficient macrophages exhibit defects in cell spreading and membrane ruffling but not migration. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1259–1268 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aranda J. F., et al. , MYADM regulates Rac1 targeting to ordered membranes required for cell spreading and migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1252–1262 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg J., Structural basis for activation of ARF GTPase: Mechanisms of guanine nucleotide exchange and GTP-myristoyl switching. Cell 95, 237–248 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho B.-A., Cho N.-H., Seong S.-Y., Choi M.-S., Kim I.-S., Intracellular invasion by Orientia tsutsugamushi is mediated by integrin signaling and actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. Infect. Immun. 78, 1915–1923 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardt W. D., Chen L. M., Schuebel K. E., Bustelo X. R., Galán J. E., S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell 93, 815–826 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu H., et al. , Exploitation of the endocytic pathway by Orientia tsutsugamushi in nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 74, 4246–4253 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koo J.-E., et al. , Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases is involved in the induction of interferon beta gene in macrophages infected with Orientia tsutsugamushi. Microbiol. Immunol. 53, 123–129 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang K., et al. , Pivotal role of phosphoinositide-3 kinase in regulation of cytotoxicity in natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol. 1, 419–425 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frost J. A., et al. , Cross-cascade activation of ERKs and ternary complex factors by Rho family proteins. EMBO J. 16, 6426–6438 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang Y., Yu J., Field J., Signals from the Ras, Rac, and Rho GTPases converge on the Pak protein kinase in Rat-1 fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1881–1891 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abel A. M., et al. , IQGAP1: Insights into the function of a molecular puppeteer. Mol. Immunol. 65, 336–349 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown M. D., Bry L., Li Z., Sacks D. B., IQGAP1 regulates Salmonella invasion through interactions with actin, Rac1, and Cdc42. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30265–30272 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guthrie C., Fink G. R., “Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology” in Methods in Enzymology (Elsevier, San Diego, CA, 1991), pp. 12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mumberg D., Müller R., Funk M., Regulatable promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Comparison of transcriptional activity and their use for heterologous expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 5767–5768 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas B. J., Rothstein R., Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell 56, 619–630 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chatterjee A., Wang L., Armstrong D. L., Rossie S., Activated Rac1 GTPase translocates protein phosphatase 5 to the cell membrane and stimulates phosphatase activity in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3872–3882 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chayen N. E., Stewart P. S., Blow D. M., Microbatch crystallization under oil - a new technique allowing many small-volume crystallization trials. J. Cryst. Growth 122, 176–180 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carpenter A. E., et al. , CellProfiler: Image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7, R100–R111 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB (ID codes 6X1H [OtDUBGEF apo] and 6X1G [OtDUBGEF:Rac1 complex]).