Significance

Glutaric acid is an important dicarboxylic acid used in the synthesis of commercial polymers. Here we report metabolic engineering of an l-lysine–overproducing Corynebacterium glutamicum strain for the high-level production of glutaric acid. The glutaric acid biosynthesis pathway was established in C. glutamicum by optimally expressing the genes encoding key enzymes from Pseudomonas putida and C. glutamicum for the efficient conversion of l-lysine to glutaric acid. Further metabolic engineering and overexpression of a newly discovered glutaric acid exporter gene resulted in the production of 105.3 g/L of glutaric acid without byproducts from glucose. The metabolic engineering strategies described here will be useful for developing microbial strains for the bio-based production of other chemicals in addition to glutaric acid.

Keywords: metabolic engineering, Corynebacterium glutamicum, glutaric acid, multiomics

Abstract

There is increasing industrial demand for five-carbon platform chemicals, particularly glutaric acid, a widely used building block chemical for the synthesis of polyesters and polyamides. Here we report the development of an efficient glutaric acid microbial producer by systems metabolic engineering of an l-lysine–overproducing Corynebacterium glutamicum BE strain. Based on our previous study, an optimal synthetic metabolic pathway comprising Pseudomonas putida l-lysine monooxygenase (davB) and 5-aminovaleramide amidohydrolase (davA) genes and C. glutamicum 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (gabT) and succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (gabD) genes, was introduced into the C. glutamicum BE strain. Through system-wide analyses including genome-scale metabolic simulation, comparative transcriptome analysis, and flux response analysis, 11 target genes to be manipulated were identified and expressed at desired levels to increase the supply of direct precursor l-lysine and reduce precursor loss. A glutaric acid exporter encoded by ynfM was discovered and overexpressed to further enhance glutaric acid production. Fermentation conditions, including oxygen transfer rate, batch-phase glucose level, and nutrient feeding strategy, were optimized for the efficient production of glutaric acid. Fed-batch culture of the final engineered strain produced 105.3 g/L of glutaric acid in 69 h without any byproduct. The strategies of metabolic engineering and fermentation optimization described here will be useful for developing engineered microorganisms for the high-level bio-based production of other chemicals of interest to industry.

Due to the increasing concerns around climate change and our heavy dependence on fossil resources, substantial effort has been exerted for the bio-based production of chemicals, fuels, and materials from renewable resources. Metabolic engineering, a key enabling technology for developing microbial cell factories, has rapidly advanced to the stage of systems-level metabolic engineering for the development of engineered microorganisms capable of efficiently producing them (1–4). Various microorganisms capable of producing diverse natural and nonnatural chemicals and materials have been developed over the last decade (5). In particular, bio-based polymers and their building blocks have been receiving much attention as environmentally friendly alternatives to the petroleum-derived plastics (6, 7).

Glutaric acid, also known as pentanedioic acid, is a widely used chemical for various applications, including production of polyamides, polyurethanes, glutaric anhydride, 1,5-pentanediol, and 5-hydroxyvaleric acid (8), which are used in consumer goods, textile, and footwear industries (9). Glutaric acid has been produced by various petroleum-based chemical methods, including oxidation of 2-cyanocylopentanone catalyzed by nitric acid and condensation of acrylonitrile with ethyl malonate (10–12). These processes rely on nonrenewable and toxic starting materials, however. Thus, various approaches have been taken to biologically produce glutaric acid from renewable resources (13–19).

Naturally, glutaric acid is a metabolite of l-lysine catabolism in Pseudomonas species, in which l-lysine is converted to glutaric acid by the 5-aminovaleric acid (AVA) pathway (20, 21). We previously reported the development of the first glutaric acid-producing Escherichia coli by introducing this pathway comprising Pseudomonas putida davB, davA, davT, and davD genes encoding l-lysine 2-monooxygenase (DavB), 5-aminovaleramide amidohydrolase (DavA), 5-aminovalerate aminotransferase (DavT), and glutarate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (DavD), respectively (15). Another pathway through condensation of α-ketoglutarate with acetyl-CoA was also attempted in E. coli, but the titer achieved by flask cultivation was only 0.42 g/L (16). Glutaric acid production by metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum has also been reported in several studies (13, 17, 19). Recently, Wittmann and colleagues developed a glutaric acid-overproducing C. glutamicum strain (17) by engineering an AVA-producing strain that they had previously developed (22). They overexpressed the genes encoding 5-aminovalerate aminotransferase (GabT encoded by gabT), succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (GabD encoded by gabD), and a newly discovered AVA importer (Ncgl0464) to create a C. glutamicum strain that produced 90 g/L glutaric acid with a productivity of 1.8 g/L/h and yield of 0.7 mol glutaric acid per mol (glucose + molasses) from glucose and molasses by fed-batch fermentation. However, considering that C. glutamicum has the capability of producing >130 g/L (and even >200 g/L in industry) of l-lysine (23), further improvement of glutaric acid production seems possible.

C. glutamicum is a widely used organism for global amino acid production (24). It has been engineered for the annual production of several million tons of l-glutamate and l-lysine (25). Beyond amino acids, many other commodity chemicals, diols, diamines, carotenoids, and terpenes have been produced by metabolically engineered C. glutamicum (25, 26). In addition, C. glutamicum can utilize various carbon sources, such as glucose, sucrose, fructose, and xylose (27), which provides the additional advantage of substrate flexibility for industrial use. Compared with other microorganisms, such as E. coli and P. putida, no l-lysine degradation pathway exists in C. glutamicum. We have previously demonstrated the conversion of l-lysine to AVA by introduction of the davAB genes from P. putida into the C. glutamicum BE strain, an l-lysine overproducer (13). The engineered strain produced not only AVA, but also glutaric acid as a byproduct, indicating that there is a pathway for converting AVA to glutaric acid in C. glutamicum, and that further engineering of this strain might allow the efficient production of glutaric acid.

In this work, we performed metabolic engineering of the C. glutamicum BE strain to produce glutaric acid by applying multiple strategies (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). First, an optimal glutaric acid synthetic pathway was established in C. glutamicum by fine-tuning the gene expression levels. Next, additional metabolic engineering, such as promoter change and introduction of additional copies of genes in the key l-lysine biosynthetic pathway, was performed to increase l-lysine production and increase the precursor of glutaric acid. Multiomics analyses were performed to acquire a comprehensive picture of the host strain and identify the target genes to be manipulated for increasing glutaric acid-forming flux. Finally, the fed-batch fermentation condition was optimized for the high-level production of glutaric acid from glucose.

Results and Discussion

Design and Construction of the Glutaric Acid Biosynthetic Pathway.

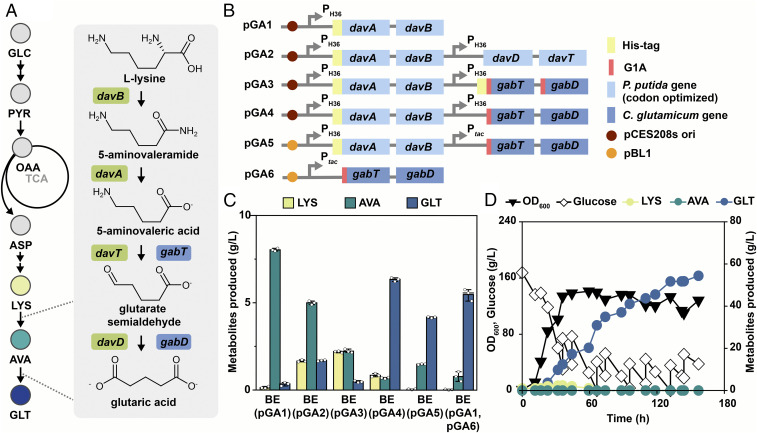

Among the three major pathways for glutaric acid production (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), the l-lysine catabolic pathway via AVA from P. putida (Fig. 1A) was chosen because we wanted to take advantage of the l-lysine–overproducing C. glutamicum BE strain. This simple route does not involve highly reactive chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide and was successfully used for glutaric acid production in E. coli in our previous study (15). For the conversion of l-lysine to AVA, pGA1 was constructed to express the davAB operon from P. putida (Fig. 1B). The BE strain harboring pGA1 converted almost all l-lysine to AVA, producing 8.1 g/L of AVA and 0.1 g/L of l-lysine (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Overview for construction of the glutaric acid biosynthesis pathway in the C. glutamicum BE strain. (A) Schematic of the glutaric acid biosynthesis pathway from glucose. The genes in light green are obtained from P. putida, and the genes in blue are obtained from C. glutamicum. Each gene encodes the following: davA, 5-aminovaleramide amidohydrolase; davB, l-lysine 2-monooxygenase; davT, 5-aminovalerate aminotransferase; davD, glutarate semialdehyde dehydrogenase; gabT, 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase; and gabD, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. (B) Schematic of plasmids used for glutaric acid biosynthesis. (C) Flask cultivation results of glutaric acid-producing strains. Error bars represent SD, and the white circles represent individual data points. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Cells were cultured for 48 h. (D) Fed-batch fermentation profile of the BE strain harboring pGA4. ASP, l-aspartate; AVA, 5-aminovaleric acid; GLC, glucose; GLT, glutaric acid; LYS, l-lysine; OAA, oxaloacetate; PYR, pyruvate.

Having developed an engineered strain efficiently converting l-lysine to AVA, we then constructed the second synthetic pathway converting AVA to glutaric acid (Fig. 1A). Two candidate pathways are available for this: the P. putida DavT-DavD l-lysine catabolic pathway and C. glutamicum GabT-GabD γ-aminobutyrate metabolic pathway. Homology modeling of C. glutamicum GabT followed by molecular docking simulation suggested that the nonnatural substrate AVA binds to the same pocket of GabT in an analogous manner to the natural substrate γ-aminobutyrate (13). In addition, GabT shares high homology with P. putida DavT. Thus, both P. putida davTD and C. glutamicum gabTD operons were tested for the conversion of AVA to glutaric acid. Using pGA1, three different plasmids—pGA2, pGA3, and pGA4 (Fig. 1B), harboring davTD, his-tagged gabTD, and gabTD operon, respectively—together with the davAB operon were constructed and transformed to the BE strain. The flask cultivation of these three strains demonstrated that the BE strain harboring pGA4 showed the highest glutaric acid titer compared with those of others, producing 6.4 g/L of glutaric acid (Fig. 1C). Next, pGA5 was constructed by changing the backbone plasmid from pCES208s to pEKEx1 with a higher copy number and a tac promoter.

Further construction of pGA6 harboring the gabTD operon followed, to test the two-vector system. Both plasmids were transformed to the BE strain to identify the best combination for glutaric acid production. pGA6 was transformed to the BE strain together with pGA1. Consistent with the previous results, the BE strain harboring pGA4 produced the most glutaric acid (Fig. 1C), indicating that the combination of codon-optimized davAB operon and native gabTD operon under the control of H36 promoter is the best for efficient glutaric acid production in C. glutamicum. To further validate the synthetic pathway, fed-batch fermentation of the BE strain harboring pGA4 was conducted. As shown in Fig. 1D, 54.4 g/L of glutaric acid (yield of 0.19 g/g and productivity of 0.35 g/L h−1) was produced without any l-lysine, and AVA remained, indicating the efficient conversion of these precursors to glutaric acid by the synthetic pathways. Therefore, pGA4 was used for further experiments.

Rational Metabolic Engineering of Glutaric Acid Producers.

To increase the glutaric acid flux in the C. glutamicum BE strain, the target genes to be engineered were selected based on the results of previous studies performed on C. glutamicum wild-type (WT) ATCC 13032 and ATCC 21831 strains (28, 29). Since 4 mol of NADPH is required to biosynthesize 1 mol of l-lysine (22), sufficient NADPH level is a crucial factor in the synthesis of l-lysine–derived products. Thus, the NADPH supply was enhanced by increasing the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) flux by changing the start codon of the pgi gene (encoding glucose-6-phosphate isomerase) from ATG to GTG and the start codon of the zwf gene (encoding glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase) from GTG to ATG (28, 29). In addition, the native promoter of the tkt operon was replaced with a stronger sod promoter. Next, the production of the key precursor, l-lysine, was enhanced by integrating the second copy of ddh encoding diaminopimelate dehydrogenase next to the ddh gene in the genome. The ATG start codon of the icd gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase was replaced by GTG. Furthermore, the lysE gene encoding an l-lysine exporter was deleted to reduce the excretion of l-lysine into the medium and consequently secure more l-lysine for subsequent conversion to glutaric acid. Six strains constructed (GA1 to GA6; SI Appendix, Table S1) were cultured in flasks to examine l-lysine production. Unexpectedly, no significant increase in l-lysine production was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Moreover, the level of l-lysine produced by the GA6 strain, in which the l-lysine exporter gene was deleted, was even slightly higher than that of the BE strain (19.4 g/L vs. 18.5 g/L). Nonetheless, the GA1 to GA6 strains were transformed with pGA4 and cultured in flasks to examine glutaric acid production.

As reflected in the l-lysine production results, all the strains produced less glutaric acid than the BE strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). These results suggest that rational metabolic engineering strategies that worked for other C. glutamicum strains do not work for the l-lysine–overproducing BE strain. Thus, comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and fluxomic analyses of the BE strain were performed to better understand the metabolic characteristics and identify engineering targets for enhanced glutaric acid production.

Identification of Engineering Targets by Multiomics Analyses of the C. glutamicum BE Strain.

Although the BE strain is a known l-lysine overproducer (13), its genomic and metabolic characteristics have not yet been assessed. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the BE strain was performed. The genome size of the BE strain was 3,343,309 bp, slightly larger than the 3,309,401 bp of the C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 WT strain (hereinafter the WT strain). The GC content of 54.1% was also higher than the 53.8% of the WT strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

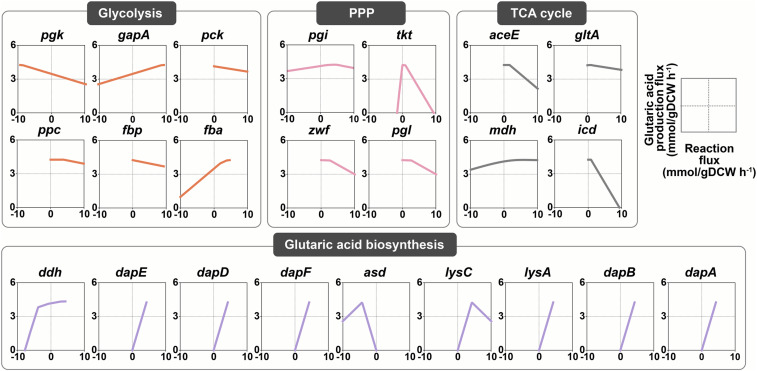

Using the genomic data, the genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) of the BE strain was reconstructed. The heterologous metabolic reactions comprising the glutaric acid biosynthetic pathway were added for subsequent fluxome analyses. To identify the target genes to be overexpressed for enhanced glutaric acid production, flux variability scanning based on enforced objective flux (FVSEOF) simulation (30) was performed using the reconstructed GEM. The Pearson correlation value of each reaction was obtained to examine the correlation between the average of the flux variability of the reaction and the glutaric acid production flux (SI Appendix, Table S3). The positive Pearson correlation value indicates that glutaric acid production is more likely to be increased by stronger flux of the corresponding reaction. If a reaction showed a Pearson correlation value >0.9, then the corresponding gene was selected as an overexpression target. Flux response analysis was also performed to analyze the correlation between glutaric acid production flux and the flux of each reaction in glycolysis, PPP, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Fig. 2); those genes responsible for the reactions that showed positive correlations with the glutaric acid production flux were selected as the candidate genes to be amplified. Based on the results of FVSEOF analysis and flux response analysis, the amplification targets were narrowed down to five genes: lysA (encoding diaminopimelate decarboxylase), dapB (encoding dihydropicolinate reductase), dapA (encoding 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase), lysC (encoding aspartokinase), and ddh.

Fig. 2.

Flux response analysis results for glutaric acid production. Each box represents the response of glutaric acid production flux to varying flux of reactions of genes in glycolysis, PPP, the TCA cycle, and the glutaric acid biosynthetic pathway. Each reaction of the genes in glycolysis, PPP, the TCA cycle, and the glutaric acid biosynthetic pathway was gradually increased from the minimum flux to the maximum flux while maximizing glutaric acid production flux. The negative flux of each reaction indicates the reverse reaction. Genes shown here are listed in SI Appendix, Note S1.

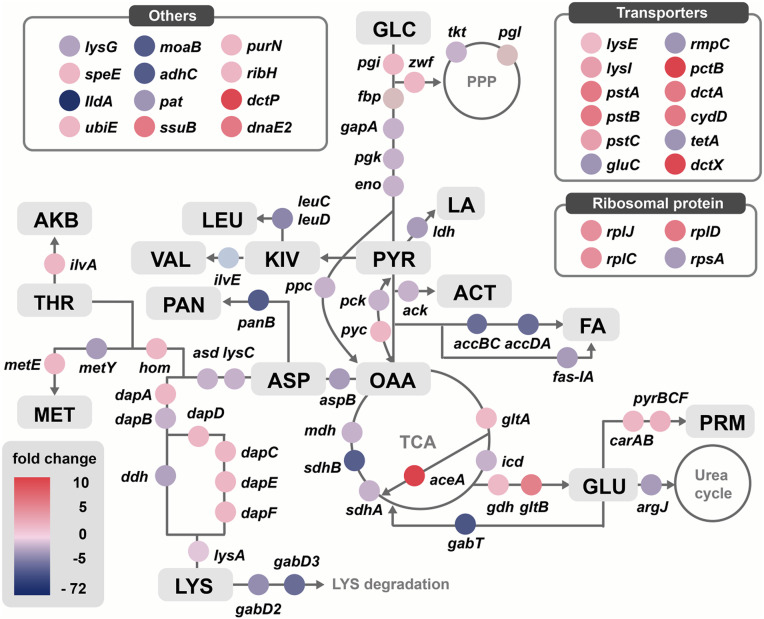

Next, comparative transcriptome analysis between the BE and WT strains was performed. The endogenous genes with significantly different expression levels between the two strains are summarized in Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Table S4. The fold change value (BE/WT) indicates the expression level of each gene in the BE strain with respect to that in the WT strain. Here the positive and negative fold change values mean that the mRNA level of the corresponding gene in the BE strain is higher and lower, respectively, than that of the WT strain. As expected, dapA, dapC (encoding succinyl-aminoketopimelate transaminase), dapE (encoding succinyl-diaminopimelate desuccinylase), dapF (encoding diaminopimelate epimerase), lysE, and lysI (encoding l-lysine small transporter protein), which are responsible for l-lysine production, showed high positive fold change values, indicating strong l-lysine flux in the BE strain. In contrast, gabT, gabD2, and gabD3, the genes involved in l-lysine degradation, showed negative fold change values of −16.54, −4.40, and −5.14, respectively, which also explains the high level of l-lysine production in the BE strain. Unexpectedly, five genes—lysA, dapB¸ lysC, ddh, and ppc (encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase)—showed negative fold changes in the BE strain, even though they are involved in l-lysine biosynthesis. Thus, these five genes were selected as overexpression targets. Among these five genes, lysA, dapB, dapA¸ and lysC overlapped with those amplification targets identified by fluxome analysis. Thus, a total of six overexpression target genes—lysA, dapB, dapA¸ lysC, ddh, and ppc—were selected.

Fig. 3.

Comparative transcriptome analysis between the BE and WT strains. The fold change value (BE/WT) of each gene indicating the comparative gene expression level between the BE and WT strains is represented in color. ACT, acetate; AKB, α-ketobutyrate; ASP, l-aspartate; FA, fatty acid; GLC, glucose; GLU, l-glutamate; KIV, ketoisovalerate; LA, lactate; LEU, l-leucine; LYS, l-lysine; MET, l-methionine; THR, l-threonine; OAA, oxaloacetate; PAN, pantoate; PRM, pyrimidine; PYR, pyruvate; VAL, l-valine. The genes shown here are listed in SI Appendix, Note S2.

In addition, the lysE and lysI genes encoding proteins exporting l-lysine were selected as deletion targets to increase the intracellular l-lysine available for glutaric acid production. Furthermore, well-known strategies, such as amplification of pyc (encoding pyruvate carboxylase), deletion of pck (encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase), and reduced expression of icd (28, 29), were used.

Construction of a Glutaric Acid-Producing Platform Strain.

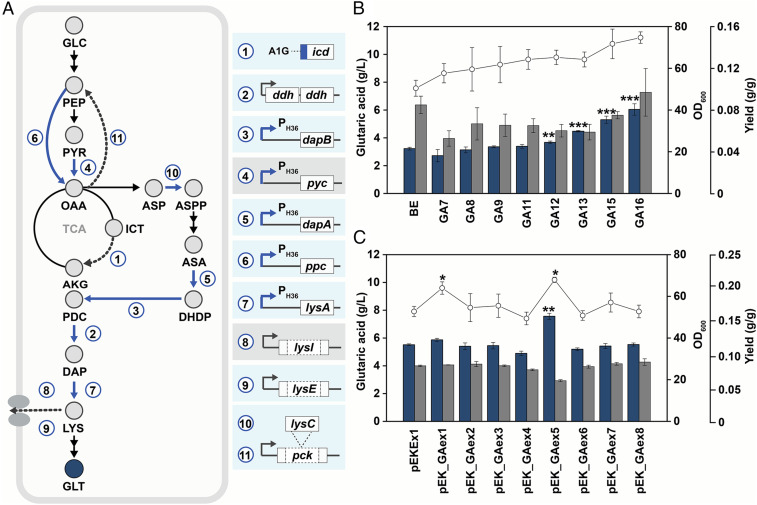

To construct a C. glutamicum strain with higher glutaric acid flux, 11 target genes identified above were engineered one by one into the BE strain (Fig. 4A). First, the GA7 strain was constructed by changing the start codon of the icd gene from ATG to GTG to decrease the flux of TCA cycle and thereby increase glutaric acid flux. To enhance l-lysine biosynthesis, an additional copy of the ddh gene was inserted next to the ddh gene in the genome of GA7 to make the GA8 strain. Then the native promoter of the dapB gene was changed to a stronger H36 promoter in GA8 to make the GA9 strain. Flask cultures of the GA7, GA8, and GA9 strains harboring pGA4 produced 2.7, 3.1, and 3.4 g/L of glutaric acid with respective yields of 0.11, 0.12, and 0.12 g of glutaric acid per 1 g of glucose (Fig. 4B). Thus, the yields of the three constructed strains were all higher than that (0.10) of the BE (pGA4) strain, but the titer was higher only in the GA9 (pGA4) strain.

Fig. 4.

Construction of the glutaric acid-producing platform strain. (A) Overview of the engineering strategies to enhance glutaric acid flux. The blue and dotted arrows represent up-regulated and down-regulated flux, respectively. The strategies that brought no significant increase in glutaric acid production are shown in gray boxes. (B) Comparison of glutaric acid titers, cell growth, and yields obtained by flask cultivation of engineered C. glutamicum strains. Each strain harboring pGA4 was tested. The P values of the data showing increases compared with BE (pGA4) are *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (C) The effect of putative glutaric acid exporter gene amplification on glutaric acid production. Each plasmid was transformed to the GA16 strain together with pGA4, and the generated strains were cultured in flasks. The P values of the data showing increases compared with GA16 (pGA4, pEKEx1) are *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. The blue and gray bars indicate glutaric acid titer (g/L) and OD600, respectively, while the white circles indicate yield. The error bars represent SD. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Cells were cultured for 48 h. AKG, α-ketoglutarate; ASA, l-aspartyl-semialdehyde; ASP, l-aspartate; ASPP, l-aspartate-phosphate; DAP, diaminopimelate; DHDP, l-2,3-dihydropicolinate; GLC, glucose; GLT, glutaric acid; ICT, isocitrate; LYS, l-lysine; OAA, oxaloacetate; PDC, l-piperidine-2,6-discarboxylate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR, pyruvate.

The GA9 strain was further engineered by replacing the promoter of the pyc gene with the H36 promoter to make the GA10 strain. However, the GA10 (pGA4) strain produced less glutaric acid (3.2 g/L) than the GA9 (pGA4) strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Thus, we returned to the GA9 strain and proceeded by replacing the promoters of dapA, ppc, and lysA with the H36 promoter to construct the GA11, GA12, and GA13 strains, respectively. The GA11, GA12, and GA13 strains harboring pGA4 produced 3.4, 3.7, and 4.5 g/L, respectively, all showing increased glutaric acid production. The glutaric acid yields of the three strains were the same as 0.13 g glutaric acid per 1 g of glucose.

Next, to prevent l-lysine export and consequently increase the intracellular l-lysine pool for glutaric acid production, the GA14 and GA15 strains were constructed by deleting lysI and lysE, respectively, in the GA13 strain. While the GA14 (pGA4) strain showed no improved glutaric acid production (4.5 g/L; SI Appendix, Fig. S5), the GA15 (pGA4) strain produced 5.3 g/L of glutaric acid, which is 18% higher than that obtained with GA13 (pGA4) (Fig. 4B). Thus, as expected and reported previously (17), deletion of the l-lysine exporter gene was beneficial for enhanced glutaric acid production.

Finally, the GA16 strain was constructed by integrating an additional copy of lysC into the middle of pck. This lysC knock-in strategy allows the reduction of oxaloacetate conversion to pyruvate and enhanced conversion of aspartate to l-aspartate-phosphate. The GA16 (pGA4) produced 6.1 g/L of glutaric acid (Fig. 4B), 1.9-fold greater than the amount produced by the BE (pGA4) strain. The glutaric acid yield (0.15 g/g) obtained with the GA16 (pGA4) strain was also the highest among the different strains.

Fed-Batch Fermentation for Glutaric Acid Production.

To enhance glutaric acid production, fermentation conditions, including carbon source, oxygen transfer rate, nutrient feeding strategy, and the batch-phase glucose level, were optimized. First, simultaneous utilization of glucose and sucrose was examined, because this strategy improved l-arginine production in C. glutamicum in our previous study (29). Four different mass ratios of glucose to sucrose (1:0, 1:1, 3:1, and 0:1) were examined in flask cultivation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). However, glutaric acid titers obtained were similar to the titer obtained with glucose only, and thus glucose was used as a carbon source in further experiments.

Second, the effect of oxygen supply on glutaric acid was examined. Generally, C. glutamicum requires enough oxygen for rapid growth, and a sufficient oxygen level is beneficial for the production of chemicals. Moreover, DavB, which converts l-lysine to 5-aminovaleramide, requires oxygen to catalyze the reaction (13). Thus, it was hypothesized that a higher oxygen transfer rate during fermentation would benefit glutaric acid production. For the fed-batch fermentation of the GA16 (pGA4) producing 61.0 g/L of glutaric acid (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A), the agitation speed was set at 600 rpm, and no additional oxygen was supplied. To increase the oxygen transfer rate, the agitation speed was automatically controlled by dissolved oxygen (DO) level from 600 to 1,000 rpm. Pure oxygen was also automatically added when needed. The fed-batch culture of the GA16 (pGA4) under this high oxygen transfer condition produced 75.1 g/L of glutaric acid (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), suggesting that higher oxygen transfer rate increased both cell growth and glutaric acid production.

Third, the nutrient feeding method was examined. In the aforementioned fed-batch cultures, glucose was manually fed when the residual glucose concentration became low. Instead of manual feeding, the pH-stat feeding strategy, which automatically adds a feeding solution when the pH rises higher than the set point, was examined. The pH-stat fed-batch culture of GA16 (pGA4) under high oxygen transfer conditions produced 90.5 g/L of glutaric acid (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), significantly higher than that obtained with the manual feeding. In addition, the glutaric acid productivity obtained by pH-stat feeding (0.81 g/L h−1) was much higher than that (0.55 g/L h−1) obtained by manual feeding. In summary, the optimal fed-batch culture condition was achieved by using the pH-stat feeding strategy under high oxygen transfer conditions using glucose as a carbon source. This condition was used in subsequent fed-batch cultures.

Identification of a Glutaric Acid Exporter.

When overproducing a desired chemical, it is essential to efficiently excrete the product so that the product can be continuously synthesized inside the cell. A number of studies have already shown that overexpressing the exporters of target product can debottleneck biological production of target molecules (17, 31, 32). However, no glutaric acid exporter of C. glutamicum has been reported. Thus, we searched for exporters of other dicarboxylic acids from C. glutamicum, E. coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (33–35). Then, from the genome sequence of the BE strain, their orthologous genes, including dctA1, dctX, dctM, ykuT, ynfM, dctA2, dauA1, and dauA2, were identified (SI Appendix, Table S5). These genes were cloned into pEKEx1, which is compatible with pGA4, to make pEK_GAex1-8. The GA16 strain was transformed with pGA4 and each of pEK_GAex1-8. Flask culture of the GA16 (pGA4, pEK_GAex5) strain expressing ynfM produced 7.6 g/L of glutaric acid (Fig. 4C).

To investigate whether the ynfM gene is a true glutaric acid exporter, we constructed the GA16 ΔynfM strain by disrupting ΔynfM in the GA16 strain. After transforming pGA4 into the GA16 ΔynfM strain, flask culture was performed. The mutant strain produced no glutaric acid, while the parent strain, GA16 (pGA4), produced 6.1 g/L of glutaric acid (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). When the ynfM gene was expressed in the GA16 ΔynfM strain from a plasmid, 4.6 g/L of glutaric acid was produced. These results suggest that ynfM encodes a glutaric acid exporter. Given that ynfM has previously been suggested to encode a succinic acid exporter (33), the gene product of ynfM seems to be a good dicarboxylic acid exporter.

Having constructed an efficient glutaric acid producer, GA16 (pGA4, pEK_GAex5), we performed fed-batch fermentation. Surprisingly, only 45.5 g/L of glutaric acid was produced (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), which was even lower than the 54.4 g/L obtained by fed-batch culture of the BE (pGA4) strain. It was reasoned that the use of two-plasmid system caused a metabolic burden, resulting in lower glutaric acid production. Thus, instead of plasmid-based overexpression of ynfM, its native promoter was replaced with a stronger promoter in the genome. The GA17 and GA18 strains were constructed by replacing the native promoter of ynfM with H30 and H36 promoters, respectively. Flask cultures of the GA17 (pGA4) and GA18 (pGA4) strains produced 9.4 and 9.2 g/L, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), more than that produced using the two-plasmid system.

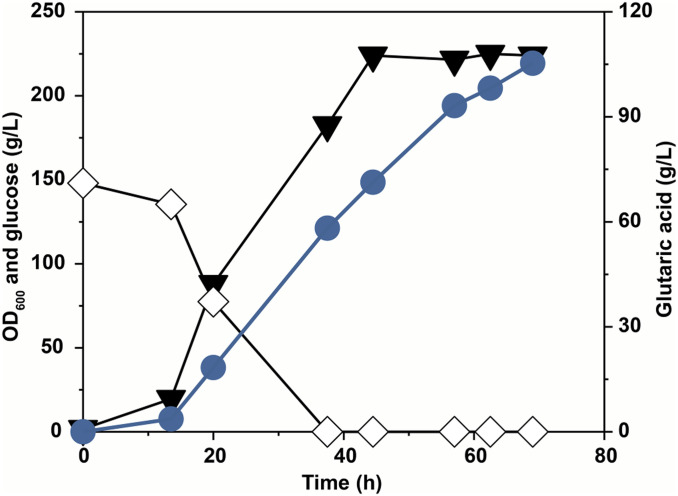

Fed-batch culture of the GA17 (pGA4) strain produced 105.3 g/L of glutaric acid with a yield and productivity of 0.54 g/g and 1.53 g/L h−1, respectively (Fig. 5). The titer, yield, and productivity were all significantly higher than those (54.4 g/L, 0.13 g/g, and 0.35 g/L h−1) obtained with the starting strain, BE (pGA4). This is the highest glutaric acid titer achieved to date. It is also notable that no byproduct was produced in fermentation, which is a big advantage in the purification process. To sum up, the metabolically engineered C. glutamicum strain has proven potential as a competitive microbial host for sustainable glutaric acid production.

Fig. 5.

Fed-batch fermentation profile of the GA17 strain harboring pGA4. The black triangle represents OD600; the white diamond, glucose (g/L); blue circles, glutaric acid (g/L). For reproducibility, the results of another fed-batch culture performed independently are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S13.

Conclusions

In this study, a highly efficient glutaric acid producer was developed by metabolic engineering of an l-lysine–overproducing C. glutamicum BE strain. After construction of a synthetic pathway comprising the davA and davB genes from P. putida and the gabT and gabD genes from C. glutamicum, their expression levels were optimized. Then system-wide analyses were performed by genome sequencing, followed by transcriptome and fluxome analyses to better understand the metabolic characteristics and identify target genes to be engineered to enhance glutaric acid production. Through engineering of 11 target genes by promoter exchange, gene deletion, and integration of additional gene copy, glutaric acid production could be increased to 6.1 g/L in flask culture. Then an optimal fed-batch culture condition was found using the pH-stat feeding strategy under high oxygen transfer conditions using glucose as a carbon source. In addition, a glutaric acid exporter gene, ynfM, was discovered. When the expression level of this exporter gene was increased from the chromosome, glutaric acid production could be further enhanced. Fed-batch culture of the final strain produced 105.3 g/L of glutaric acid without any byproduct in 69 h, the highest titer achieved to date. The strategies of systems metabolic engineering (1–3) and fermentation optimization described here (summarized in SI Appendix, Table S7) will be useful for the development of microbial cell factories capable of producing chemicals of interest with high efficiency.

Materials and Methods

All of the materials and methods used in this study are detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods, including strains and plasmids, construction of plasmids, culture conditions, fed-batch fermentation, genome manipulation, analytical methods, GC/MS analysis, reconstruction of the C. glutamicum BE strain GEM and in silico simulations, and comparative transcriptome analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jae Sung Cho for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (Grant 2020M3A9I503788311) and funded by the Ministry of Science and Information Communication Technology, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2017483117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the main text and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Choi K. R., et al. , Systems metabolic engineering strategies: Integrating systems and synthetic biology with metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 817–837 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S. Y., Kim H. U., Systems strategies for developing industrial microbial strains. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1061–1072 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen J., Keasling J. D., Engineering cellular metabolism. Cell 164, 1185–1197 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atsumi S., Hanai T., Liao J. C., Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature 451, 86–89 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S. Y., et al. , A comprehensive metabolic map for production of bio-based chemicals. Nat. Catal. 2, 18–33 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S. Y., et al. , Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of polyesters: A 100-year journey from polyhydroxyalkanoates to non-natural microbial polyesters. Metab. Eng. 58, 47–81 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vieira M. G. A., da Silva M. A., dos Santos L. O., Beppu M. M., Natural-based plasticizers and biopolymer films: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 47, 254–263 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G., Huang D., Sui X., Li S., Huang B., Zhang X., Wu H., Deng Y., Advances in microbial production of medium-chain dicarboxylic acids for nylon materials. React. Chem., 10.1039/C9RE00338J (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M., Li G., Deng Y., Engineering Escherichia coli for glutarate production as the C5 platform backbone. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e00814–e00818 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paris G., Berlinguet L., Gaudry R., English J. Jr., Dayan J., Glutaric acid and glutarimide. Org. Synth. 37, 47 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usui Y., Sato K., A green method of adipic acid synthesis: Organic solvent-and halide-free oxidation of cycloalkanones with 30% hydrogen peroxide. Green Chem. 5, 373–375 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y. C., Romero J. R., Electrocatalytic oxidation of beta-dicarbonyl compounds using ceric methanesulphonate as mediator. Quim. Nova 21, 144–145 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin J. H., et al. , Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for enhanced production of 5-aminovaleric acid. Microb. Cell Fact. 15, 174 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkins J., Jordan J., Nielsen D. R., Engineering Escherichia coli for renewable production of the 5-carbon polyamide building-blocks 5-aminovalerate and glutarate. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110, 1726–1734 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S. J., et al. , Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of 5-aminovalerate and glutarate as C5 platform chemicals. Metab. Eng. 16, 42–47 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J., Wu Y., Sun X., Yuan Q., Yan Y., De novo biosynthesis of glutarate via α-keto acid carbon chain extension and decarboxylation pathway in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1922–1930 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohles C. M., et al. , A bio-based route to the carbon-5 chemical glutaric acid and to bionylon-6, 5 using metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Green Chem. 20, 4662–4674 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W., et al. , Targeting metabolic driving and intermediate influx in lysine catabolism for high-level glutarate production. Nat. Commun. 10, 3337 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H. T., et al. , Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of glutaric acid, a C5 dicarboxylic acid platform chemical. Metab. Eng. 51, 99–109 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fothergill J. C., Guest J. R., Catabolism of L-lysine by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 99, 139–155 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Revelles O., Espinosa-Urgel M., Fuhrer T., Sauer U., Ramos J. L., Multiple and interconnected pathways for L-lysine catabolism in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7500–7510 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohles C. M., Gießelmann G., Kohlstedt M., Wittmann C., Becker J., Systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of the carbon-5 platform chemicals 5-aminovalerate and glutarate. Microb. Cell Fact. 15, 154 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng J., Chen P., Song A., Wang D., Wang Q., Expanding lysine industry: Industrial biomanufacturing of lysine and its derivatives. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 45, 719–734 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wendisch V. F., Microbial production of amino acids and derived chemicals: Synthetic biology approaches to strain development. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 30, 51–58 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker J., Wittmann C., Bio-based production of chemicals, materials and fuels: Corynebacterium glutamicum as versatile cell factory. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 631–640 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker J., Wittmann C., Microbial production of extremolytes: High-value active ingredients for nutrition, health care, and well-being. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 65, 118–128 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim H. T., et al. , Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the high-level production of cadaverine that can be used for the synthesis of biopolyamide 510. ACS Sustain. Chem. 6, 5296–5305 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker J., Zelder O., Häfner S., Schröder H., Wittmann C., From zero to hero: Design-based systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-lysine production. Metab. Eng. 13, 159–168 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S. H., et al. , Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-arginine production. Nat. Commun. 5, 4618 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J. M., et al. , Flux variability scanning based on enforced objective flux for identifying gene amplification targets. BMC Syst. Biol. 6, 106 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubitz D., Jorge J. M., Pérez-García F., Taniguchi H., Wendisch V. F., Roles of export genes cgmA and lysE for the production of L-arginine and L-citrulline by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 8465–8474 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youn J.-W., Jolkver E., Krämer R., Marin K., Wendisch V. F., Characterization of the dicarboxylate transporter DctA in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 191, 5480–5488 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukui K., et al. , Corynebacterium glutamicum CgynfM encodes a dicarboxylate transporter applicable to succinate production. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 127, 465–471 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker M., et al. , Glutamate efflux mediated by Corynebacterium glutamicum MscCG, Escherichia coli MscS, and their derivatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828, 1230–1240 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karinou E., Compton E. L., Morel M., Javelle A., The Escherichia coli SLC26 homologue YchM (DauA) is a C(4)-dicarboxylic acid transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 623–640 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the main text and SI Appendix.