Abstract

We report herein the syntheses of 79 derivatives of the 4(3H)-quinazolinones and their structure–activity relationship (SAR) against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Twenty one analogs were further evaluated in in vitro assays. Subsequent investigation of the pharmacokinetic properties singled out compound 73 ((E)-3-(5-carboxy-2-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one) for further study. The compound synergized with piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP) both in vitro and in vivo in a clinically relevant mouse model of MRSA infection. The TZP combination lacks activity against MRSA, yet it synergized with compound 73 to kill MRSA in a bactericidal manner. The synergy is rationalized by the ability of the quinazolinones to bind to the allosteric site of penicillin-binding protein (PBP)2a, resulting in opening of the active site, whereby the β-lactam antibiotic now is enabled to bind to the active site in its mechanism of action. The combination effectively treats MRSA infection, for which many antibiotics (including TZP) have faced clinical obsolescence.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Antibiotic resistance is a major public health threat.1–3 A group of six bacteria, referred to as the ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) pathogens, account for the majority of the US hospital-acquired infections.4 Annually, 35 000 deaths due to antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the US.1 Infections caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) result in 10 600 of these deaths in the US according to the estimates.1 While several antibiotics are clinically used for the treatment of MRSA infections, including ceftaroline and ceftobiprole (fifth-generation cephalosporins), linezolid and tedizolid (oxazolidinone class), telavancin and dalbavancin (semisynthetic variants of the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin), and daptomycin,5,6 resistance to all these has been documented and mortality and morbidity due to MRSA infections remain serious.1,6–9 Discovery of novel classes of antibiotics for the treatment of MRSA infections remains of high urgency.10,11

Historically, β-lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems) were agents of choice for the treatment of S. aureus infections. With the emergence of MRSA over half a century ago, the entire class of β-lactam antibiotics became compromised as the pathogen acquired a set of genes from a non-S. aureus source that conferred inducible resistance to all known members of the β-lactam antibiotics.12–16 One such gene is mecA, which encodes an additional penicillin-binding protein (PBP), referred to as PBP2a.14,17,18 In a series of publications from our labs, we have elucidated the mechanistic basis of how PBP2a is impervious to inhibition by β-lactam antibiotics, yet capable of performing its critical physiological function of cross-linking of the cell wall in the face of the challenge by the antibiotic.19–22 We also disclosed how the fifth-generation cephalosporin ceftaroline is capable of inhibiting PBP2a by subverting the allosteric mechanism that the enzyme uses for its physiological reaction of cross-linking the cell wall.17,23,24 Consequently, PBP2a is an important target for the design of novel antibiotics.

We previously reported on the discovery of the quinazolinones as non-β-lactam antibacterials active against MRSA, which target cell wall biosynthesis.25 Quinazolinones, as exemplified by compound 1, have oral (po) bioavailability, low clearance, and show efficacy in mouse models of MRSA infection.25–27 We subsequently showed that the quinazolinones inhibit both PBP2a and PBP1.25–27 We have documented that the quinazolinones bind to the allosteric site of PBP2a by X-ray crystallography,25,27 by competition binding assays,25,27 and by antisense sensitization.25,26 Binding at the allosteric site triggers conformational changes that lead to opening of the active site.19 The active site of PBP2a is normally closed, does not allow access to most β-lactams for binding’ and this accounts for the lack of activity of these antibiotics against MRSA. To this effect, we have documented the ternary complex of a quinazolinone bound to the allosteric site of PBP2a and the β-lactam piperacillin at the active site of PBP2a by X-ray crystallography.27

In the present report, we define the chemical space of this antibacterial class by syntheses of 79 quinazolinones, diversified structurally at sites highlighted as A, B, and C in the structure of 1. These compounds were screened for activity against the ESKAPE panel of bacteria. Twenty one compounds were further evaluated with four important MRSA strains in in vitro toxicity and plasma protein-binding assays. Selected compounds were then evaluated for their pharmacokinetic (PK) properties.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis.

Two synthetic routes were devised (Scheme 1). One approach to the quinazolinone scaffold was in three steps per methodology reported previously,26 with minor modifications as needed for various derivatives. The synthesis started from anthranilic acid (2), which was converted to 2-methyl-4H-3,1-benzoxazin-4-one (3) in refluxed triethyl orthoacetate or acetic anhydride. Compound 3 was subsequently transformed into the respective quinazolinone cores (4) by a condensation reaction with a requisite amine (aniline derivatives) in refluxed pyridine, acetic acid, or toluene (intermediates 11–42 are of this type, Figure S1). Condensation of the quinazolinone intermediates 4 and the selected aldehyde, catalyzed by acid, base, or ZnCl2, would deliver quinazolinone derivatives 5 (e.g., 48–110, 113) with limited further modifications. Hydrogenation of compound 5 produced compound 6 (e.g., 114 and 115). The second approach to the quinazolinone scaffold was also via the anthranilic acid (2). Conversion of 2 by the respective isothiocyanate(s) in refluxing acetic acid provided 2-thiocarbonyl 4(1H)-quinazolinone 7 (intermediates 43, 44a, and 45 are of this type, Figure S1). The thioether-linker containing analogs 8 (final products 124 and 125) were directly obtained by substitution of NaH-pretreated 2-thiocarbonyl 4(1H)-quinazolinones with the respective alkyl-bromides. Various functionalizations of the 2-thiocarbonyl 4(1H)-quinazolinones, such as the introduction of chloride (exemplified by compounds 9), provided intermediates 44b, 44, 46, and 47 (Figure S1), leading to derivatives of the general structure 10 by substitution in the presence of a base (final products such as 116–123, 126–129).

Scheme 1. General Synthetic Route for the Quinazolinonesa.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) triethyl orthoacetate, reflux, 4 h; (b) R1NH2, AcOH or pyridine, reflux or sealed tube at 130 °C, 8 h; or R1NH2, toluene, reflux, Dean–Stark, 8 h; (c) R2CHO, AcOH, AcONa, reflux, 8 h; or R2CHO, pyridine, reflux, 8 h; or R2CHO, anhydrous ZnCl2, neat, sealed tube at 130 °C, 1 h; (d) H2, Pd/C, room-temperature (rt), 12 h; (e) R1NCS, AcOH, reflux, 1 h; (f) R2CH2Br, NaH, anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF), ice-water to rt, 1 h; (g) PCl5, POCl3, reflux, 8 h; (h) R2NH2, triethylamine, tetrahydrofuran (THF), sealed tube at 100 °C, 8 h.

Structure–Activity Relationships.

Structural modifications of the quinazolinones were made in rings A and B, as well as in the linker C (Figure 1). Compounds were first screened against S. aureus ATCC29213; those with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≤ 64 μg/mL were evaluated in the remaining ESKAPE panel (Table S1) The quinazolinones in general exhibit selective activity against S. aureus, with no activity against E. faecium and Gram-negative bacteria. In SAR1 (Figure 1, top panel), we altered the nature of ring A by substitutions that increased the hydrophilicity of the moiety and by increasing the flexibility of the functionalities linked to the quinazolinone core. Most of such replacements led to the loss of activity (48–52 and 60–68). In a few cases (53–56 and 58–59) for which the MIC was acceptable (MIC = 0.25–4 μg/mL), the ring structure was incorporated with electron-withdrawing groups, such as halides or nitrile.

Figure 1.

Antibacterial activities of the 4(3H)-quinazolinones derivatives. The MICs (μg/mL) were determined with S. aureus ATCC29213. The MICs for inactive (MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL) and active compounds (MIC ≤ 4 μg/mL) are in red and blue, respectively. The four previously reported compounds, given here for comparison, are designated in underlined numbers.26 The MICs for the positive controls vancomycin and linezolid are 1 and 2 μg/mL, respectively.

In SAR2 (Figure 1, middle panel), we modified ring B of the quinazolinone scaffold. Using fluorine as a bioisostere for hydrogen,28 we started with incorporation of fluorine at every position of ring B while retaining the m-carboxylic acid (analogs 69–73). The addition of fluorine at position 6 (73) improved the MIC 4-fold (from 2 to 0.5 μg/mL). The basis for this improvement might be a desirable dihedral angle between ring B and the quinazolinone core. Based on this notion, we prepared different substitutions at the ring position 6 or 2, such as chloro, methyl, trifluoromethyl, hydroxyl, and methoxyl groups. Only smaller sized and hydrophobic substitutions, as in the chloro (74) or methyl (75) variants, retained acceptable MIC values. Bulkier substituents (76 and 79) or hydrophilic ones (78, 81, 83, and 84) all led to the loss of antibacterial property. Meanwhile, we replaced the m-carboxylic acid with fused rings (85–87), hydrophilic aliphatic linkers (89–93), a few bioisosteres (88, 94–99), ortho-/para-substitutions (100–104), and hydrogen-bond acceptors (105–108). We also attempted to eliminate the ring B structure by changing it to aliphatic side chains (109–110). Compounds with the trifluoroacetamide group (88 and 99), sulfonamide group (94 and 95), amide group (96), and ortho-hydroxyl substitution (100) showed excellent MIC values (0.015–4 μg/mL). Compound 90 bearing an imidazole linker exhibited MIC of 8 μg/mL against S. aureus. Yet, it also showed some activity against E. faecium with MIC of 16 μg/mL (Table S1), in contrast to other quinazolinones, which target S. aureus exclusively. As for the hydrogen-bond-acceptor moieties, we tried pyridine (105), pyridine-N-oxide (106), nitrile (107), and azide substitution (108). Most of these compounds showed no activity (MIC ≥ 16 μg/mL), with the pyridine-N-oxide (106) analog, a possible electrostatic interaction partner, retaining activity (MIC of 2 μg/mL).

In SAR3 (Figure 1, lower panel), we mainly focused on the modification of the alkenyl linker. Compound 113, a variant of the potent derivative 94, was synthesized here for comparison with 57. Like 57, compound 113 showed potent activity against S. aureus (MIC = 0.06 μg/mL). Meanwhile, we replaced the alkenyl linker with saturated aliphatic (114 and 115), amine (116–123), sulfide (124 and 125), ether (126), and piperidine/piperazine (127–129) linkers. Except for the sulfides (0.25–2 μg/mL), all of the other derivatives exhibited either diminished or lost activity. Only 115, 123–125 sustained activity (0.125–2 μg/mL), among which 123 stands out (MIC = 0.125 μg/mL). However, we had shown previously that the mesylate group resulted in very high clearance.26

The best fragments of SAR1 (4-CN), SAR2 (CO2H), and SAR3 (amine linker) were combined in compound 118; however, activity was lost (MIC > 128 μg/mL).

Three-dimensional QSAR of the Quinazolinones.

In light of the fact that the quinazolinones target more than one PBP, the activities that we measured for these compounds as MIC values are composites of the effects at both targets at the whole-organism level. This said that the chemical structure and the corresponding MIC were computationally analyzed to find broad features that influence the antibacterial activity. A total of 103 quinazolin-4(3H)-ones reported herein and earlier26 were used for the computational analysis, which included 53 active (MIC ≤ 4 μg/mL) and 50 inactive (MIC ≥ 128 μg/mL) compounds. The compounds were aligned computationally on the quinazolinone core (Figure S2A) and formed the basis of a three-dimensional QSAR model computed by the field-based Gaussian method.29–33 The model identified the steric importance for sections of rings A and B (Figure S2B). Substitution of the smaller three-membered cyclopropyl group (compound 48) in place of ring A resulted in the loss of activity. Compounds with moderately steric substitution in the meta-position of ring B (–NHCOCF3, –SO2NH2, –SO2NHAc, and –CH2NHCOCF3) were active (compounds 88, 94, 95, and 99 respectively). However, extending the bulk further in the region was detrimental to the activity (compounds 92 and 93). Additionally, the model suggested that hydrophobicity plays a role in activity (Figure S2C). Ring A showed a pronounced preference for hydrophobic groups. For example, the chloro (53) and bromo (54) substitution in the thiophene for ring A made the compounds more active than the unsubstituted thiophene counterpart (compound 52). Similarly, compounds with 4-acetylene (57), 4-Cl (58), and 4-I (59) substitutions in ring A were active. Compounds 60–68 with more polar ring A were inactive. While the hydrophobic nature in ring A appears to impart a noticeable role in the activity, substitution in ring B demonstrated more complex outcomes. Hydrophilic groups at position 3 of ring B were preferred as displayed by the white contour map (Figure S2C). Compounds with substitution of the polar carboxylic acid (1) and amine (111) at position 3 demonstrated potent activity. On the other hand, substitutions on the ring A at positions 5 and 6 revealed the importance of hydrophobicity, as shown in the contour map. Compounds with 6-F, 6-Cl, and 6-methyl substitutions on ring B (73, 74, and 75) were active, while polar hydroxyl substitution to either 5- or 6-positions (77 and 78) rendered the compounds inactive. Similarly, introducing a nitrogen in the ring (pyridine ring; 83 or 84 compared to 1) seemingly is sufficient in resulting in the loss of activity. At the same time, compound 76 with hydrophobic trifluoromethyl substitution at the 6 position was inactive, contrary to the above observation.

Broader Evaluation of Quinazolinones with MRSA Strains, Gram-Positive Organisms, In Vitro Toxicity, and Plasma Protein Binding.

Analogs with MIC of ≤4 μg/mL against the MSSA strain ATCC29213 were selected for further evaluation against four MRSA strains: NRS70, NRS119 (linezolid-resistant), ATCC27660, and USA300 (the major cause of the community-associated MRSA infections in the US),34in vitro toxicity, and plasma protein binding (Table 1). We also determined MIC against S. aureus ATCC29213 in the presence of bovine serum albumin. Compounds 1, 58, 73, 94, 115, and 125 showed 4-fold or less increase in MIC with added bovine serum albumin. Most of the analogs showed similar potency with the MRSA strains, compared to the MSSA strain ATCC29213 used for the data in Figure 1, except for compounds 88 and 94, which proved more potent in their activity against the MRSA strains.

Table 1.

In Vitro Biological Evaluation of Selected Active Quinazolinones

| MIC against S. aureus strains (μg/mL) |

XTT (IC50) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compds | ATCC29213a | NRS70b | NRS119c | ATCC27660d | USA300e | (μg·mL−1) | IC50/MIC | PPB (%) |

| 1f | 2 (8) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 173 ± 1 | 32 | 96.5 ± 0.7g |

| 57f | 0.03 (0.25) | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.03 | >128 | >256 | 99.6 ± 0.04h |

| 53 | 0.5 (4) | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 180 ± 3 | 360 | 99.3 ± 1.0 |

| 54 | 0.25 (2) | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 190 ± 2 | 380 | >99.9 |

| 55 | 4 (32) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 110 ± 1 | 28 | 99.2 ± 0.2 |

| 56 | 4 (32) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 140 ± 1 | 70 | >99.9 |

| 58 | 0.25 (1) | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 50 ± 3 | 200 | >99.9 |

| 59 | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 100 ± 1 | 200 | >99.9 |

| 73 | 0.5 (2) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 62 ± 6 | 124 | 95.4 ± 0.02 |

| 74 | 2 (16) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | >128 | >64 | >99.9 |

| 75 | 2 (16) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 60 ± 1 | 15 | >99.9 |

| 88 | 2 (32) | 0.06 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | >128 | >2133 | >99.9 |

| 94 | 0.25 (0.5) | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.06 | >64 | >1067 | 97.1 ± 0.6 |

| 95 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 200 ± 4 | 50 | 99.2 ± 0.02 |

| 96 | 2 (16) | 2 | 32 | 16 | 1 | >128 | >64 | 97.1 ± 0.3 |

| 99 | 0.5 (8) | 64 | 2 | 64 | 4 | 150 ± 6 | 2 | >99.9 |

| 100 | 0.015 (0.125) | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 40 ± 2 | 667 | 98.1 ± 0.3 |

| 106 | 2 (32) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | >128 | >128 | 67.9 ± 2.8 |

| 113 | 0.06 (0.5) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 61 ± 1 | 1017 | 98.2 ± 0.1 |

| 115 | 2 (8) | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 79 ± 4 | 40 | >99.9 |

| 123 | 0.125 (1) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 62 ± 4 | 248 | >99.9 |

| 124 | 0.25 (4) | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | >64 | >128 | >99.9 |

| 125 | 2 (8) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 78 ± 4 | 39 | >99.9 |

MSSA strain for susceptibility testing; values in parenthesis are in the presence of bovine serum albumin.

mec (subtype II) positive, resistant to clindamycin, erythromycin, and spectinomycin.

mecA positive, resistant to linezolid, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, oxacillin, and penicillin.

mecA positive, resistant to oxacillin, tetracycline, and penicillin.

mec (subtype IV) positive, pvl positive, resistant to oxacillin and erythromycin.

Previously published compounds26 given here for comparison; their MICs and 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) (IC50) were redetermined for this table.

Data from ref 25.

Data from ref 26.

We also evaluated quinazolinones 1 and 73 for activity against several Gram-positive organisms. Compound 73 was active (MIC ≤ 4 μg/mL) against Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus, while 1 showed decreased activity against these pathogens (Table 2).

Table 2.

Activity of Quinazolinones against Gram-Positive Organisms (MIC in μg/mL)

| bacteria | compound 1 | compound 73 |

|---|---|---|

| S. epidermidis ATCC 35547 | 1 | 0.25 |

| S. haemolyticus ATCC 29970 | 8 | 4 |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 | 16 | 8 |

| Clostridioides difficile ATCC 43255 | 128 | 128 |

| Bacillus cereus ATCC 13061 | >128 | >128 |

| B. licheniformis ATCC 12759 | >128 | >128 |

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | >128 | >128 |

We evaluated the cytotoxicity of selected analogs (IC50 evaluation) to HeLa cells by the XTT assay (Table 1). Derivatives 55, 75, 95, 99, 115, and 125 had the ratio of IC50/MIC of ≤50 and were not considered further. The MIC for determination of this ratio was that for the NRS70 strain. We also determined plasma protein binding for the compounds using equilibrium dialysis with human plasma (Table 1). Derivatives 53–59, 74, 75, 88, 95, 99, and 115–125 had ≥99% plasma protein binding. High plasma protein binding decreases the in vivo efficacy of an otherwise potent compound, as it limits the drug available for distribution from blood to tissues; therefore, these compounds were not considered further. Derivatives with IC50/MIC of >50 and plasma protein binding ≤99% were 73, 94, 96, 100, 106, and 113. Compounds 96, 100, and 106 had relatively poor water solubility and were not pursued further. Compounds 73, 94, and 113 were selected for further analysis.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) Studies.

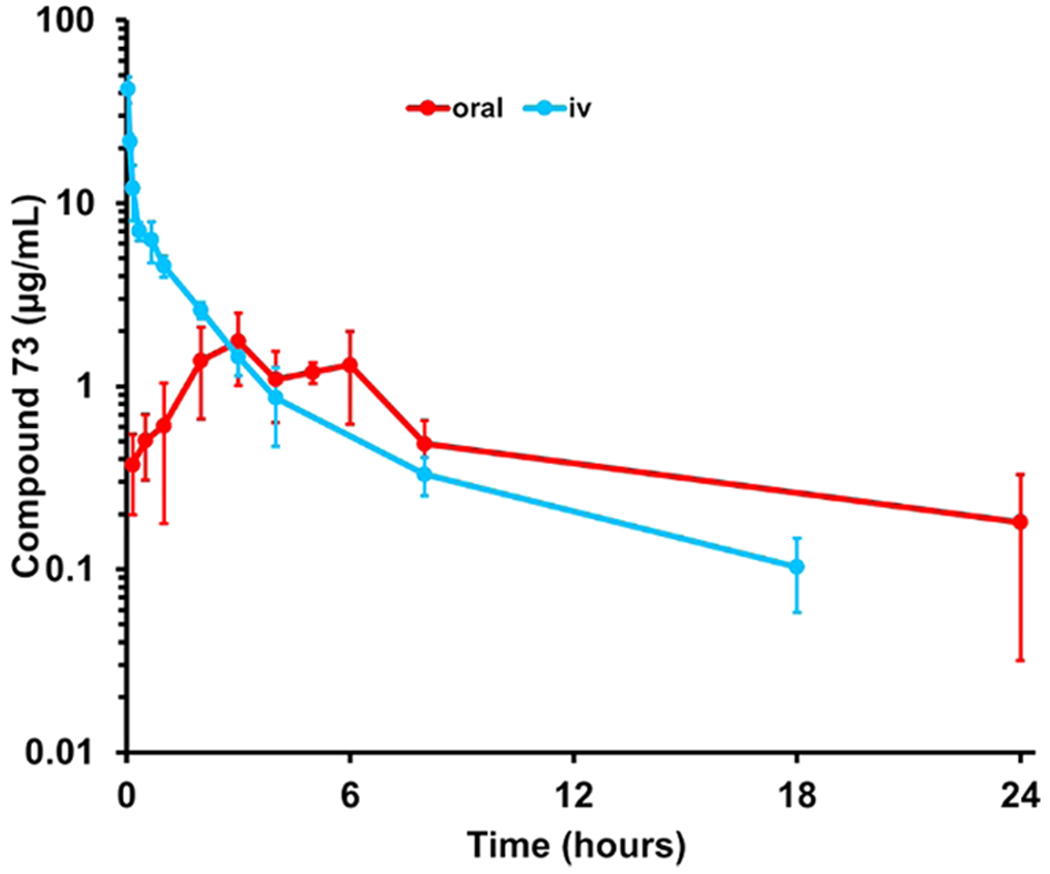

The PK properties of compounds 73, 94, and 113 were investigated after a single intravenous (iv) dosing to mice and compared to those determined for compound 125 studied previously (Table 3). After a single 10 mg/kg iv dose of 73, concentrations were above the MIC of 0.5 μg/mL for 4 h. Systemic exposure, as measured by area under the curve (AUC), was 1290 μg·min·mL−1, similar to that for compound 1. Clearance of 73 was desirably low at 7.7 mL·min−1·kg−1, <10% of hepatic blood flow, and the volume of distribution was 0.19 L·kg−1. Compounds 94 and 113 showed low systemic exposure and very high and moderate clearances of 98 and 28.2 mL·min−1·kg−1, respectively, >10% hepatic blood flow; hence, both compounds were not considered further. The absolute oral bioavailability (F%) of compound 73 was 65%. The elimination half-life for 73 was 13.7 and 11.2 h after iv and po administration, respectively. Comparisons of these parameters with those of compound 1 are given in Table 3; plasma concentrations after iv and po administration of compound 73 are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Selected Quinazolinone Derivatives

| compds | dose (mg/kg) | AUC0-lasta (μg·min/mL) | AUC0-infb (μg·min/mL) | t1/2 elim (h) | CL (mL·min−1·kg−1) | Vd (L·kg−1) | F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | 10 iv | 1180 | 1460 | >20 | 6.9 | 0.30 | 50 |

| 10 po | 408 | 738 | >20 | ||||

| 73 | 10 iv | 1290 | 1320 | 13.7 | 7.7 | 0.19 | 65 |

| 10 po | 840 | 1010 | 11.2 | ||||

| 94 | 5 iv | 51 | ND | ND | 98.0 | NDd | |

| 113 | 5 iv | 178 | ND | ND | 28.2 | NDd |

Area under the curve from 0 min to the last quantifiable time point.

Area under the curve from 0 min extrapolated to infinite time.

Data reproduced from Bouley.25

ND, not determined.

Figure 2.

Pharmacokinetics of compound 73 after a single 10 mg/kg dose administration to mice (n = 3 per time point per route of administration, total n = 63 mice).

Time-Kill Assays.

When the ratio of minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)/MIC is greater than 4, the compound is considered bacteriostatic. In the case of compound 73, MBC against NRS70 was >128 μg/mL, hence the compound is bacteriostatic. We evaluated the in vitro antibacterial activity of compound 73 as a function of time by time-kill assays and compared it to that of compound 1. At 0.5 to 16 × MIC, both compounds 1 and 73 were bacteriostatic, consistent with MBC of greater than 4 × MIC, but also by the observation that the compounds did not reduce the bacterial count by >3-log10 (Figures 3a and S3).25 Piperacillin is a fourth-generation penicillin and tazobactam is a β-lactamase inhibitor. The clinical combination of piperacillin and tazobactam (abbreviated TZP) works against S. aureus strains that express the PC1 β-lactamase.16 However, the drug combination is ineffective against MRSA (Figure 3a), as these strains express the gene mecA for PBP2a. PBP2a is not inhibited by piperacillin, as the active site of the enzyme is closed and it excludes β-lactam antibiotics. In light of the fact that the quinazolinones are known to bind to the allosteric site of PBP2a, we evaluated the combination of 1 with TZP, as well as that of 73 with TZP. At 12 h, >3-log10 reduction was observed for compound 1 + TZP; however, the combination was not synergistic at 24 h. On the other hand, compound 73 + TZP inhibited the growth of the MRSA strain with a reduced bacterial count of >3-log10 at 24 h. Compound 73 and the clinical TZP work well in combination by exhibiting bactericidal behavior (Figure 3a) in time-kill assays.

Figure 3.

(a) Time-kill assays for compounds 1 and 73 alone and in combination with TZP with MRSA strain NRS70. Compounds 1, 73, and TZP were used at 0.5 × MIC, with TZP in the 8:1 clinical ratio. (b) Neutropenic thigh-infection study in mice. Compound 73 in combination with TZP shows a significant reduction in colony counts. Mice (n = 8 per group, except untreated mice, where n = 5) were infected in the right thigh with NRS70. Treatment was started subcutaneously 1 h after infection; doses were given every 8 h (3 doses). The TZP dose was at 12 mg/kg of piperacillin and 1.5 mg/kg of tazobactam. Bacteria were counted in the infected thigh homogenates at 24 h after infection. Compound 73 was evaluated at 20 and 40 mg/kg. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Mouse Neutropenic Thigh-Infection Model.

The efficacy of compound 73 was evaluated in the mouse neutropenic thigh-infection model with strain NRS70, where bacteria in the infected thighs were counted at 24 h after infection (Figure 3b). The dose of TZP used consisted of 12 mg/kg of piperacillin and 1.5 mg/kg of tazobactam to maintain the concentration of piperacillin below the Kd of 400 μM for binding to the allosteric site of PBP2a.23 Compound 1 alone at 20 mg/kg resulted in 0.67 log10 reduction in bacterial count, while compound 73 alone gave 0.47 log10 reduction at 20 mg/kg and 0.78 log10 reduction at 40 mg/kg. For comparison, TZP alone resulted in a 0.25 log10 bacterial count reduction. Since only compound 73 showed effective activity with TZP by time-kill assays (Figure 3a), this compound was evaluated in combination with TZP in the mouse neutropenic thigh-infection model (Figure 3b). Compound 73 + TZP gave 0.75 log10 reduction at 20 mg/kg and 1.33 log10 reduction at 40 mg/kg. The results with the combination were statistically significant compared to vehicle (p < 0.001) and to TZP (p < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

The 4(3H)-quinazolinone antibacterials exhibit selective inhibitory activity against S. aureus strains, inclusive of MRSA, which are clinically challenging pathogens. These agents target cell wall biosynthesis, and expressly PBPs, although a pleotropic activity cannot be discounted at present. In the present work, we prepared 79 derivatives of these antibacterials in exploring the SAR by syntheses of 20 analogs with modifications in ring A, 42 compounds with variations in ring B, and 17 derivatives with linker modifications. In light of the fact that the compound class inhibits more than one PBP and the X-ray crystallographic information for binding to PBPs currently is limited only to that of the quinazolinones to the allosteric site of PBP2a, the SAR is largely activity-driven, rather than structure-driven. We note that our initial discovery of the quinazolinone antibacterials was also followed up by others.35–38 The present work led to compound 73 as a lead with potent MRSA activity and good PK properties, including oral bioavailability of 65%. Notwithstanding good in vitro activity in inhibition of growth of S. aureus, the in vivo activity of the quinazolinone alone was limited, as the compound is bacteriostatic. However, quinazolinone 73 in combination with TZP, a mixture of piperacillin and the β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam, which itself is devoid of activity in the treatment of MRSA infections, behaved synergistically and in a bactericidal manner. We attribute this activity to allosteric activation of PBP2a by the quinazolinone, whereby the active site becomes opened and available to covalent inhibition by piperacillin. The quinazolinone 73 enabling of covalent inhibition of PBP2a by piperacillin brings back from obsolescence the use of penicillins in the treatment of MRSA infections.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Syntheses.

Organic reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), Alfa Aesar (Tewksbury, MA), Oakwood Products, Inc. (Estill, SC), or Combi Blocks Inc. (San Diego, CA) and used without further purification. Reactions were monitored by analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using precoated silica-gel aluminum foils (200 μm, 60 F254, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, German) with UV light (254 nm). Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 Å (40–63 μm particle size) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Preparative TLC was performed on precoated silica-gel plates (2000 μm, 20 × 20 cm; 60 F254, Miles Scientific, Newark, DE) using UV light (254 nm). NMR spectra (1H, 13C) were recorded either on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 Nanobay (400 MHz for 1H and 101 MHz for 13C, Bruker Biospin AG, Fällanden, France) or a Bruker AVANCE III HD 500 (500 MHz for 1H and 126 MHz for 13C, Bruker Biospin AG, Fällanden, France) at 25 °C, and the residual nondeuterated solvent signals were used as reference (DMSO-d6, 1H δ = 2.50 ppm, 13C δ = 39.5 ppm; DMF-d7, 1H δ = 2.75, 2.92 and 8.03 ppm, 13C δ = 29.8, 34.9 and 163.2 ppm; acetone-d6, 1H δ = 2.05 ppm, 13C δ = 29.9 ppm; chloroform-d, 1H δ = 7.26 ppm, 13C δ = 77.2 ppm; methanol-d4, 1H δ = 3.31 ppm, 13C δ = 49.0 ppm). The purity of the compounds was monitored by a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) with an Acclaim RSCL 120 C18 column (0.2 μm, 120 Å, 2.1 × 100 mm, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) with monitoring at 254 nm. All of the final compounds were ≥95% pure. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded using a Bruker micrOTOF/Q2 mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Fremont, CA) with positive electrospray ionization (ESI+).

Compounds 1, 3, 11, 30, 35, and 57 were made by the methods of Bouley et al.25 Compounds 111 and 115a were synthesized according to the published protocols.26

The synthetic procedures and characterizations for representative intermediate compounds are detailed below. Detailed synthetic procedures or characterizations for the other compounds are provided in the Supporting Information (Section S2). Spectra for representative compounds are given in the Supporting Information (Section S38).

General Synthetic Procedure A.

The benzo-oxazinone derivative (typically 1.5 mL/mmol, 1.00 equiv) and the amine (1.05 equiv) are dispersed in glacial acetic acid, and the mixture is maintained under reflux for 8–12 h. After cooling down the mixture, the solvent is partially removed under reduced pressure and the specific compound is isolated using the appropriate purification method, as described in the detailed compound procedures.

General Synthetic Procedure B.

The benzo-oxazinone derivative (typically 0.5 mL/mmol, 1.0 equiv) and the amine (1.2 equiv) are dissolved in anhydrous pyridine, and the mixture is stirred at 120 °C for 8–12 h in a sealed vessel. On completion of the reaction, the mixture is cooled down and diluted with brine. The resulting mixture is extracted by EtOAc (3×). The combined EtOAc layer is dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent is removed under reduced pressure to dryness. The specific compound is isolated using the appropriate purification method, as described in the detailed compound procedures.

General Synthetic Procedure C.

The quinazolinone (typically 20 mL/mmol, 1.0 equiv), the aldehyde (1.3 equiv), and sodium acetate (2.0 equiv) are dispersed in glacial acetic acid, and the mixture is stirred under reflux for 8–12 h. On completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture is cooled down and the solvent is partially removed under reduced pressure. The specific compound is isolated using the appropriate purification method, as described in the detailed compound procedures.

General Synthetic Procedure D.

Quinazolinone (typically 2.8 mL/mmol, 1.0 equiv), aldehyde (1.3 equiv), and sodium acetate (2.0 equiv) are dispersed in glacial acetic acid, and the mixture is stirred at 135 °C for 8 h in a sealed vessel. After cooling down the mixture, the solvent is partially removed under reduced pressure. The specific compound is isolated using the appropriate purification method, as described in the detailed compound procedures.

General Synthetic Procedure E.

Anthranilic acid (typically 0.5 mL/mmol, 1.0 equiv) and isothiocyanate (1.1 equiv) are dissolved in glacial acetic acid, and the mixture is stirred at 130 °C for 1 h. The mixture is cooled down to form a precipitate, which is filtered and washed with acetic acid (3×) to give the pure product as a solid. The specific compound is isolated using the appropriate purification method, as described in the detailed compound procedures.

General Synthetic Procedure F.

3-Aryl-2-thiocarbonyl 4(1H)-quinazolinone (20 mL/mmol, 1.0 equiv) and PCl5 (1.8 equiv) are dissolved in POCl3 in an oven-dried flask. The reaction mixture was purged with dry nitrogen at rt and stirred for another 10 min. The resulting mixture is heated to reflux for 8 h. The solution is then cooled down and concentrated under reduced pressure to give an oil. The oil is dissolved in 20 mL of EtOAc and washed with water (10 mL, 3×). The organic layer is washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the given product. The specific compound is isolated using the appropriate purification method, as described in the detailed compound procedures.

The detailed synthetic procedures for the preparation of compound 73 are given below.

3-(5-Carboxy-2-fluorophenyl)-2-methylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (16).

The compound was synthesized according to the general procedure A from compound 3. Water was poured into the concentrated mixture, which resulted in a precipitate. The solid was filtered, washed with water and diethyl ether to give the title compound (187 mg, 51%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.28 (br s, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 8.17–8.11 (m, 2H), 7.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.70–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.19 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.7 (d, JCF = 255.9 Hz), 165.7, 160.8, 153.7, 147.2, 135.1, 128.6, 128.5, 126.89, 126.87, 126.4, 125.3, 125.1, 119.9, 117.1 (d, JCF = 21.3 Hz), 23.3.

(E)-3-(5-Carboxy-2-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)-quinazolin-4(3H)-one (73).

The compound was synthesized according to the general procedure C from compound 16. Water was poured into the concentrated mixture, which resulted in a precipitate. The solid was filtered, washed with water and then with diethyl ether giving the title compound (642 mg, 58%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.35 (br s, 1H), 8.24–8.15 (m, 3H), 7.99–7.91 (m, 2H), 7.84–7.80 (m, 3H), 7.73–7.70 (m, 2H), 7.65 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.8, 160.7, 160.2 (d, J = 255.4 Hz), 150.6, 147.1, 139.1, 138.1, 135.3, 132.8, 132.7, 128.6, 128.5 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 127.5, 127.4, 126.6, 124.2, 124.1, 122.4, 120.2, 118.6, 117.1 (d, J = 21.3 Hz), 111.7. 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) −115.69 (s, 1F). HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H15FN3O3, 412.1092; found, 412.1112.

Screening for Pan-Assay-Interference Structures (PAINS).

Active compounds were checked for pan-assay-interference structures (PAINS) using the PAINS remover.39

Three-dimensional (3D)-QSAR.

Field-based 3D-QSAR29 models were built by Gaussian (based on CoMSIA31,32) methods. The MIC values for each of the compounds were converted to the pMIC value as previously reported33 using equation pMIC = −ln(MIC/MW), where MW is the molecular weight of the quinazolinone. For building the model, a subset of the data set consisting of active (MIC ≤ 4 μg/mL) and inactive (MIC ≥ 128 μg/mL) quinazolin-4(3H)-ones were used. The compound structures were built with the program Maestro (v.11, Schrödinger LLC) and energy-minimized with the LigPrep program using the OPLS2005 forcefield. The structures were aligned on the quinazolinone core (Figure S2A). The final model was built with 103 compounds after exclusion of 11 outliers that emerged from the preliminary modeling. The data set was randomly divided into training (80%) and test set (20%).

Bacterial Strains.

E. faecium NCTC 7171 (ATCC 19734), S. aureus ATCC29213, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, A. baumannii ATCC 17961, P. aeruginosa ATCC 17853, Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 35029, E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC27660, S. epidermidis ATCC 35547, S. haemolyticus ATCC 29970, S. pneumonia ATCC 49619, C. difficile ATCC 43255, B. cereus ATCC 13061, B. licheniformis ATCC 12759, and E. faecalis ATCC 29212 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains NRS70, NRS119, and USA300 were obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in S. aureus (Chantilly, VA).

MIC Determination.

MICs were determined by the guidelines provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute using the microdilution method.40 Two-fold serial dilutions of the quinazolinones were prepared in triplicate in cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth with 2% NaCl and inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU/mL bacteria. The 96-well plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16–20 h. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of a compound that inhibits visible growth of bacteria after incubation. MICs with S. aureus ATCC29213 were also determined in the presence of 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich).

MBC Determination.

Following the MIC determination protocol, two-fold serial dilutions of compound 73 were made in triplicate in 5 mL tubes and inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU/mL S. aureus NRS70. After 16–20 h of incubation, 100 μL of aliquots was delivered in triplicate onto the surface of agar from 1 × MIC to 128 μg/mL concentration of 73. The MBC is determined as the concentration of the compound that enables a 99.9% reduction of the initial inoculum (≤500 CFU/mL).

XTT Assay.

Cytotoxicity assays were performed against HeLa cells (ATCC CCL-2) in triplicate following the previously reported protocol.25 The IC50 values were determined with GraphPad Prism 5 (San Diego, CA) using nonlinear regression.

Plasma Protein Binding.

A rapid-equilibrium-dialysis device (Pierce Biotechnology, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to determine plasma protein binding. Human plasma (Innovative Research, MI) was thawed and centrifuged at 1200g for 10 min to remove particulates. A 200 μL aliquot of human plasma was added to the sample chamber and 350 μL of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 mM sodium chloride was added to the adjacent chamber. A 2 μL stock solution of the compounds at a concentration of 1 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was diluted with human plasma to a final quinazolinone concentration of 10 μM and added to the sample chamber. The compounds were dialyzed at 37 °C in an orbital shaker for 6 h. Aliquots (50 μL) were taken from the buffer chamber (representing the free concentration) and from the plasma chamber (representing the total concentration) and mixed with 100 μL of the internal standard in acetonitrile to a final concentration of 5 μM. Samples were analyzed by ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with UV detection at 285 nm. The plasma protein-binding ratio (B%) was calculated according to the following equation

where Cp and Cf are the total plasma concentration and the free concentration of the compound, respectively.

Animals.

Female ICR mice (6–8 weeks old, 20–25 g body weight) were purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN). Mice were housed in polycarbonate shoeboxes containing 1/4 inch of corncob (The Andersons Inc., Maumee, OH) and α-Dri (Shepperd Specialty Papers, Inc., Richland, MI) bedding, at 72 °F with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Mice infected with MRSA were housed in disposable cages manufactured by Innovive (San Diego, CA) with the same bedding, temperature, and light/dark cycle. Mice were fed Teklad 2918 irradiated extruded rodent diet (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and water ad libitum. Animal studies were conducted with approval by the University of Notre Dame Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Studies.

Compounds 73, 94, or 113 were dissolved in 20% DMSO/10% Tween-80/70% water at a concentration of 2 mg/mL or 4 mg/mL. The dosing formulations were sterilized by filtration through a 0.2 μm, 13 mm diameter PTFE membrane attached to an Acrodisc syringe filter (Pall Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI). Mice (n = 2 per time point) were given 50 μL of compounds 73, 94, or 113 iv (equivalent to 5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg) by tail-vein injection. Terminal blood was collected at 5, 40 min, 2, 4, and 8 h. Blood was centrifuged at 1200g for 10 min to harvest plasma. Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis. A 50 μL aliquot of plasma was mixed with 100 μL of acetonitrile containing internal standard (final concentration 8 μg/mL). After centrifugation at 10 000g for 10 min, the supernatant was analyzed by UPLC with UV detection at 285 nm. A Waters Acquity UPLC System (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) consisting of a binary pump, an autosampler, a column heater, and a photodiode array detector was used. A Kinetex C18 2.6 μm, 2.1 mm i.d. × 75 mm column was used. Elution was at 0.5 mL/min with 80% A/20% B for 2 min, followed by a 10 min linear gradient to 10% A/90% B, then 80% A/20% B for 2 min, where A = water and B = acetonitrile.

Antibiotics.

Tazobactam was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); piperacillin was obtained from TCI (Portland, OR).

Time-Kill Assays.

Time-kill assays were performed, as described previously.27 Compounds 1, 73, and TZP were maintained at 0.5 × MIC concentration. The piperacillin-tazobactam mixture was used at an 8:1 ratio, which is used clinically. A control tube without antibiotic was also included. At intervals of 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, aliquots of the cultures were plated on Luria broth (LB) agar media for colony counts. The limit of detection was >50 CFU/mL and a ≥3-log10 reduction of colonies from the starting inoculum was considered bactericidal. The experiment was done in triplicate.

Dose Tolerance Studies.

Compound 73 was evaluated for dose tolerance after single-dose intravenous and oral administration to mice (n = 4 per group) at 0 (vehicle control), 10, 20, 40, and 100 mg/kg. Compound 73 was dissolved in 5% DMSO/95% water at concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5.0, 10, and 25 mg/mL, followed by sterilization and by filtration. Mice were administered 100 μL of solution via tail-vein injection or oral gavage. Mice were observed for 3 days, body weights were measured every day (Figure S4), and clinical observations were recorded.

Neutropenic Thigh-Infection Model.

A neutropenic thigh infection study to evaluate the efficacy of compound 73 was performed, as described previously.27 The mice (n = 8 per group) were rendered neutropenic by intraperitoneal treatment with 200 mg/kg solution of cyclophosphamide (Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA) at 4 days and 1 day prior to infection. An inoculum of 0.1 mL of MRSA strain NRS70 at a final concentration of 1 × 106 CFU/mL in brain heart infusion broth was injected intramuscularly into the right thighs of all of the animals. The infected animals were treated with either vehicle (10% DMSO and 90% water), 20 mg/kg of compound 1, 20 and 40 mg/kg of compound 73, 12 mg/kg of piperacillin with 1.5 mg/kg of tazobactam, or a combination of compound 73 at 20 and 40 mg/kg with TZP. The drugs were dissolved in 10% DMSO/90% water, sterile-filtered, and administered subcutaneously (three doses) every 8 h starting 1 h after the infection. The animals were euthanized 24 h later, and the infected thighs were harvested aseptically for bacterial counts. The uninfected thighs were collected to measure drug levels.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains NRS70, NRS119, and USA300 were provided by the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in S. aureus (NARSA) for distribution by BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH. This project is supported by grants AI116548 (to M.C.) and AI104987 (to S.M.) from the National Institutes of Health. Y.Q. is a Ruth L. Kirschtein National Research Service Award Fellow of the Chemistry-Biochemistry-Biology Interface Program at the University of Notre Dame, supported by Training Grant T32GM075762 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- AcOH

acetic acid

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide

- HOBt

hydroxybenzotriazole

- HATU

1 N-[(dimethylamino)-1H-1,2,3-triazolo-[4,5-b]pyridin-1-ylmethylene]-N-methylmethanaminium hexafluorophosphate N-oxide

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- AUC

area under the curve

- CL

clearance

- CFU

colony forming unit

- iv

intravenous

- MBC

minimum bactericidal concentration

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- PBP

penicillin-binding protein

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- po

oral

- PPB

plasma protein binding

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TZP

piperacillin-tazobactam

- UPLC

ultraperformance liquid chromatography

- UV

ultraviolet

- Vd

volume of distribution

- XTT

2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00153.

Experiment procedures and characterization of synthesized compounds; chemical structures of synthesized intermediates; MIC of reported compounds against the ESKAPE organisms; information of compounds used in the QSAR study; computational analysis of quinazolinones; representative NMR spectra/LCMS results (PDF)

Molecular formula strings for synthesized molecules (CSV)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00153

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): US patent 9,776,975 has been issued for the quinazolinones.

Contributor Information

Yuanyuan Qian, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Giuseppe Allegretta, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Jeshina Janardhanan, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Zhihong Peng, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Kiran V. Mahasenan, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Elena Lastochkin, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Melissa Malia N. Gozun, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Sara Tejera, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Valerie A. Schroeder, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

William R. Wolter, Freimann Life Sciences Center, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Rhona Feltzer, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Shahriar Mobashery, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Mayland Chang, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Pourmand A; Mazer-Amirshahi M; Jasani G; May L Emerging Trends in Antibiotic Resistance: Implications for Emergency Medicine. Am. J. Emerg. Med 2017, 35, 1172–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hofer U The Cost of Antimicrobial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2019, 17, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rice LB Federal Funding for the Study of Antimicrobial Resistance in Nosocomial Pathogens: No ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bush K Synergistic Antibiotic Combinations. Top. Med. Chem 2018, 25, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Rodvold KA; McConeghy KW Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Therapy: Past, Present, and Future. Clin. Infect. Dis 2014, 58, S20–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Morales G; Picazo JJ; Boas E; Candel FJ; Arribi A; Pelaez B; Andrade R; de la Torre M-A; Fereres J; Sanchez-Garcia M Resistance to Linezolid is Mediated by the cfr Gene in the First Report of an Outbreak of Linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis 2010, 50, 821–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Smith TL; Pearson ML; Wilcox KR; Cruz C; Lancaster MV; Robinson-Dunn B; Tenover FC; Zervos MJ; Band JD; White E; Jarvis WR Emergence of Vancomycin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus Working Group. N. Engl. J. Med 1999, 340, 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Thomer L; Schneewind O; Missiakas D Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections. Annu. Rev. Pathol 2016, 11, 343–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Turner NA; Sharma-Kuinkel B; Maskarinec SA; Eichenberger EM; Shah PP; Carugati M; Holland TL; Fowler VG Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An Overview of Basic and Clinical Research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2019, 17, 203–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lee AS; de Lencastre H; Garau J; Kluytmans J; Malhotra-Kumar S; Peschel A; Harbarth S Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim 2018, 4, 18033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Braaten D News Feature: Bugs vs Drugs. Nat. Med 2007, 13, 522–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lakhundi S; Zhang K Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Characterization, Evolution, and Epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2018, 31, No. e00020–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Peacock SJ; Paterson GK Mechanisms of Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Ann. Rev. Biochem 2015, 84, 577–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Llarrull LI; Fisher JF; Mobashery S Molecular Basis and Phenotype of Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and Insights into New β-Lactams that Meet the Challenge. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 4051–4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Testero SA; Fisher JF; Mobashery S Beta-Lactam Antibiotics In Burger’s Medicinal Chemistry, Drug Discovery and Development; Abraham DJ; Rotella DP., Eds.; Wiley and Sons, New York, 2010; Vol. 7, pp 259–404. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Fishovitz J; Hermoso JA; Chang M; Mobashery S Penicillin-binding Protein 2a of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 572–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Fuda C; Suvorov M; Vakulenko SB; Mobashery S The Basis for Resistance to β-Lactam Antibiotics by Penicillin-binding Protein 2a of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 40802–40806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mahasenan KV; Molina R; Bouley R; Batuecas MT; Fisher JF; Hermoso JA; Chang M; Mobashery S Conformational Dynamics in Penicillin-binding Protein 2a of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Allosteric Communication Network and Enablement of Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2102–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Otero LH; Rojas-Altuve A; Llarrull LI; Carrasco-Lopez C; Kumarasiri M; Lastochkin E; Fishovitz J; Dawley M; Hesek D; Lee M; Johnson JW; Fisher JF; Chang M; Mobashery S; Hermoso JA How Allosteric Control of Staphylococcus aureus Penicillin Binding Protein 2a Enables Methicillin Resistance and Physiological Function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2013, 110, 16808–16813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Fuda C; Hesek D; Lee M; Morio K; Nowak T; Mobashery S Activation for Catalysis of Penicillin-binding Protein 2a from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Bacterial Cell Wall. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 2056–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Acebron I; Chang M; Mobashery S; Hermoso JA The Allosteric Site for the Nascent Cell Wall in Penicillin-binding Protein 2a: An Achilles’ Heel of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Med. Chem 2015, 22, 1678–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Fishovitz J; Taghizadeh N; Fisher JF; Chang M; Mobashery S The Tipper-Strominger Hypothesis and Triggering of Allostery in Penicillin-binding Protein 2a of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6500–6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Villegas-Estrada A; Lee M; Hesek D; Vakulenko SB; Mobashery S Co-opting the Cell Wall in Fighting Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Potent Inhibition of PBP 2a by Two Anti-MRSA β-Lactam Antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 9212–9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bouley R; Kumarasiri M; Peng Z; Otero LH; Song W; Suckow MA; Schroeder VA; Wolter WA; Lastochkin E; Antunes NT; Pi H; Vakulenko S; Hermoso JA; Chang M; Mobashery S Discovery of Antibiotic (E)-3-(3-Carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 81, 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bouley R; Ding D; Peng Z; Bastian M; Lastochkin E; Song W; Suckow MA; Schroeder VA; Wolter WR; Mobashery S; Chang M Structure-activity Relationship for the 4(3H)-Quinazolinone Antibacterials. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 5011–5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Janardhanan J; Bouley R; Martínez-Caballero S; Peng Z; Batuecas-Mordillo M; Meisel JE; Ding D; Schroeder VA; Wolter WR; Mahasenan KV; Hermoso JA; Mobashery S; Chang M The Quinazolinone Allosteric Inhibitor of PBP2a Synergizes with Piperacillin and Tazobactam Against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2019, 63, No. e02637–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Meanwell NA Synopsis of Some Recent Tactical Application of Bioisosteres in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 2529–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Schrödinger Release: Field-Based QSAR, 2018-3; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cramer RD; Patterson DE; Bunce JD Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA). 1. Effect of Shape on Binding of Steroids to Carrier Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 5959–5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Klebe G; Abraham U; Mietzner T Molecular Similarity Indices in a Comparative Analysis (CoMSIA) of Drug Molecules to Correlate and Predict their Biological Activity. J. Med. Chem 1994, 37, 4130–4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Klebe G; Abraham U Comparative Molecular Similarity Index Analysis (CoMSIA) to Study Hydrogen-bonding Properties and to Score Combinatorial Libraries. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des 1999, 13, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Leemans E; Mahasenan KV; Kumarasiri M; Spink E; Ding D; O’Daniel PI; Boudreau MA; Lastochkin E; Testero SA; Yamaguchi T; Lee M; Hesek D; Fisher JF; Chang M; Mobashery S Three-dimensional QSAR Analysis and Design of New 1,2,4-Oxadiazole Antibacterials. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2016, 26, 1011–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Planet PJ Life after USA300: The Rise and Fall of a Superbug. J. Infect. Dis 2017, 215, S71–S77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Jadhavar PS; Dhameliya TM; Vaja MD; Kumar D; Sridevi JP; Yogeeswari P; Sriram D; Chakraborti AK Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Structure–activity Relationship of 2-Styrylquinazolones as Anti-tubercular Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2016, 26, 2663–2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Gatadi S; Gour J; Shukla M; Kaul G; das S; Dasgupta A; Madhavi YV; Chopra S; Nanduri S Synthesis and Evaluation of New 4-Oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)benzoic acid and Benzamide Derivatives as Potent Antibacterial Agents Effective Against Multidrug Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Chem 2019, 83, 569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gatadi S; Gour J; Shukla M; Kaul G; Dasgupta A; Madhavi YV; Chopra S; Nanduri S Synthesis and Evaluation of New Quinazolin-4(3H)-one Derivatives as Potent Antibacterial Agents Against Multidrug Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2019, 175, 287–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Gatadi S; Gour J; Kaul G; Shukla M; Dasgupta A; Akunuri R; Tripathi R; Madhavi YV; Chopra S; Nanduri S Synthesis of New 3-Phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one Derivatives as Potent Antibacterial Agents Effective Against Methicillin- and Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA and VRSA). Bioorg. Chem 2018, 81, 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Baell JB; Holloway GA New Substructure Filters for Removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from Screening Libraries and for their Exclusion in Bioassays. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wikler MA; Cockerill FR; Craig WA; Dudley MN; Eliopoulos GM; Hecht DW; Hindler JF; Low DE; Sheehan DJ; Tenover FC; Turnidge JD; Weistein MP; Zimmer BL; Ferraro MJ; Swenson JM Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard; 8th Ed.; Document M7-A8; Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2009; Vol. 29, pp 1–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.