Abstract

Introduction:

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary intracranial malignancy; survival can be improved by maximizing the extent-of-resection.

Methods:

A near-infrared fluorophore (Indocyanine-Green, ICG) was combined with a photosensitizer (Chlorin-e6, Ce6) on the surface of superparamagnetic-iron-oxide-nanoparticles (SPIONs), all FDA-approved for clinical use, yielding a nanocluster (ICS) using a microemulsion. The physical-chemical properties of the ICS were systematically evaluated. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy (PDT) was evaluated in vitro with GL261 cells and in vivo in a subtotal resection trial using a syngeneic flank tumor model. NIR imaging properties of ICS were evaluated in both a flank and an intracranial GBM model.

Results:

ICS demonstrated high ICG and Ce6 encapsulation efficiency, high payload capacity, and chemical stability in physiologic conditions. In vitro cell studies demonstrated significant PDT-induced cytotoxicity using ICS. Preclinical animal studies demonstrated that the nanoclusters can be detected through NIR imaging in both flank and intracranial GBM tumors (ex: 745nm, em: 800nm; mean signal-to-background 8.5±0.6). In the flank residual tumor PDT trial, subjects treated with PDT demonstrated significantly enhanced local control of recurrent neoplasm starting on postoperative day 8 (23.1mm3 vs 150.5mm3, p=0.045), and the treatment effect amplified to final mean volumes of 220.4mm3 vs 806.1mm3 on day 23 (p=0.0055).

Conclusion:

A multimodal theragnostic agent comprised solely of FDA-approved components was developed to couple optical imaging and PDT. The findings demonstrated evidence for the potential theragnostic benefit of ICS in surgical oncology that is conducive to clinical integration.

Keywords: Glioblastoma multiforme, Indocyanine green (ICG), Chlorin-e6 (Ce6), nanoparticle, fluorescence-guided surgery, photodynamic therapy, theragnostics

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) remains one of the most formidable clinical challenges in neuro-oncology, afflicting patients with high rate of recurrence and a 5-year survival rate as low as 5% [1, 2]. In contrast to other cancers where distant metastases are common, GBM recurrence generally occurs within 1–2 cm of the primary resection cavity [3]. Increased extent-of-resection has been found to correlate with improved patient outcomes [4]. However, the heterogeneity and infiltrative behavior of high-grade gliomas make complete resection difficult to achieve [5, 6]. Anatomical and technical factors pose additional challenges to gross-total resection. For instance, in cases when complete resection by radiographical standard carries a high risk of post-operative neurological deficit, subtotal resections are usually performed, resulting in higher risk of recurrence [7].

Fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) represent two of the treatment strategies that have demonstrate clinical benefits in GBM patients. FGS allows surgeons to visualize and resect tumor’s invasive margins. In 2006, a pivotal phase III trial with 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), a prodrug that leads to the accumulation of visible-light fluorophore protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) in malignant glioma tissue, demonstrated enhanced resection rate and progression-free-survival in GBM patients treated with FGS [8]. More recently, near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging has emerged as a favorable modality for intraoperative visualization, as NIR fluorophores overcome several limitations of visible-light agents, affording high imaging resolution with minimal autofluorescence from biological samples, reduced light scattering and high tissue penetration [9, 10]. Indocyanine green (ICG, peak excitation = 805 nm, peak emission = 835 nm), an NIR agent, has been successfully used to visualize common intracranial neoplasms in human, including gliomas, metastases and meningiomas, with high sensitivity (>90%) 24 hours after high-dose IV infusion [11–13]. Moreover, ICG is the first and only FDA-approved fluorophore found to fluoresce in the NIR-II window (1000nm-1700nm), leading to more preferable optical imaging characteristics [14].

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves the use of a photosensitizer, which upon excitation by light, produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are cytotoxic to cells. The clinical use of PDT in brain malignancies continues to evolve [15, 16]. Notably, a multicenter Phase III trial found that resection complemented by PDT with 5-ALA and Photofrin led to a statistically significant increase in progression-free survival [17]. Since then, second-generation photosensitizers (e.g. Chlorin-e6) have been developed, featuring enhanced photoactivation at longer wavelengths (660-670nm) and reduced dark toxicity compared to hematoporphyrin derivatives [18]. The potential clinical benefit of Chlorin-e6 (Ce6)-mediated PDT has been demonstrated in the treatment of bladder, lung, skin and head and neck cancers [19, 20].

The need for novel therapeutic strategies for GBM has led to interest in combinatorial approaches. In the last few decades, rapid development in nanotechnology has enabled the design of nanoparticles that integrate diagnostics and therapeutics in a single nanoscale (< 100 nm) agent, a concept came to be known as theranostics [21]. Engineering multifunction nanoparticles “all-in-one” has become an attractive approach to effectively image and treat disease without causing collateral damage to healthy tissue [22] and offers an opportunity to combine the benefits of FGS and PDT in GBM treatment in a single dose.

To date, nanoparticles have been explored in multiple areas of glioma therapy as imaging contrast agent [23, 24], drug delivery vehicle [25, 26], and thermotherapy agent [27], among others [28]. In contrast to 98% of small-molecule drugs and almost 100% of large-molecule drugs that cannot cross the biological barriers (e.g. blood-brain barrier, blood-brain tumor barrier) to reach GBM [29], nano-carriers readily accumulate in intracranial tumor tissues based on the well-described enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which stipulates that molecules of certain sizes (e.g. liposomes, nanoparticles) preferentially retain in solid tumors owing to defective vascular structures, impaired lymphatic drainage systems, and increased permeability mediators [30]. Nanoparticles can be administered through various routes including intravenous (IV), oral, and intranasal administration. The IV route offers rapid onset of action and control of the rate of infusion, while the main risk involves exposure of the drug in the systemic circulation [31]. In the engineering process, factors including core material, size, shape and surface modifications play important roles in the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles, which directly impact therapeutic efficacy. The reticuloendothelial system (RES), due to its tendency to adsorb plasma proteins which leads to uptake by macrophages and rapid clearance in the liver/spleen, needs to be taken into consideration as a determining factor for the in vivo circulation time of nanoparticles [32].

Recently, our team has developed a new approach to load hydrophobic metal colloids and drugs into stable water-soluble nanoclusters, by using small amphiphilic dyes such as ICG [23, 33], Ce6 [34], and PpIX [35] as coating materials. With this technique, we synthesized a novel formulation combining ICG and Ce6 with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) into a nanocluster, referred to as ICG-Ce6-SPION (ICS). SPION, serving as the nanocarrier in this formulation, is the only clinically approved metal oxide nanoparticle and has been extensively researched in biomedical applications [36]. In fact, all constituents of ICS have been FDA-approved for clinical application. The aim of the current study is to explore the technical feasibility and efficacy of combining FGS and PDT using this multimodal theranostic agent as a therapeutic strategy for GBM.

Materials and Methods

ICG-Ce6-SPION nanoclusters (ICS)

Hydrophobic SPIONs with 7 nm diameter were synthesized by thermal decomposition method as described previously [34]. A mixture containing Ce6/ICG at the different ratio w/w (in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) and SPIONs (in toluene) was pipetted into a glass vial containing 4 mL of water. The sample was sonicated and left overnight to evaporate toluene. Finally, dialysis was performed with 4 L of water to remove DMSO. Free Ce6 and ICG were removed through passage of sample in MACS column.

Cell Line

GL261-luciferase cells (gift from Dorsey lab) were cultured in CELLSTAR Filtered Cap Cell Culture Flasks in DMEM (4.5g/L glucose, Invitrogen) supplemented by 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

In Vitro Photodynamic Therapy

Extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was investigated using ABDA (9,10-anthracenediylbis (methylene) dimalonic acid), an established photochemical probe for ROS. Next, 7.5 × 103 cells-per-well were incubated in 96-well plates overnight and mixed with incremental concentrations (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10μg/ml) of ICG-coated SPION nanocluster (ICG-SC), Ce6-coated SPION nanocluster (Ce6-SC) or ICS diluted in DMEM in quadruplets. The experimental cells were irradiated with a 665nm diode laser to a dose of 5J/cm2 (16.40min), while the control group remained in dark. Light was delivered through microlens-tipped fibers (Pioneer, Tokyo, Japan). The intensity of laser output was adjusted to a power density of 5mW/cm2 (LabMaster power meter, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). The post-treatment cell viabilities were determined at 24hrs after treatment using an MTS colorimetric assay (ab197010, Abcam Inc. Cambridge, UK) according to the supplier’s instructions.

GBM Flank Tumor Model

5-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (n=12) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and Jackson Laboratories. About 4 × 106 cells in 300μl of 1:1 PBS and Corning Matrigel Matrix were implanted in the left flank of the mice at 6–8 weeks of age, following previously described protocols [37]. Animals were observed every 3-4 days to evaluate tumor growth.

In Vivo PDT on Residual Neoplasm

5mg/kg of ICS (n=12) or saline in matched volume (n=4) was administered via tail-vein injection in flank-tumor bearing mice. All mice underwent partial resection under anesthesia using 1-4% isoflurane 24hrs post-drug administration. D-Luciferin sodium salt (150mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally to all mice prior to first incision and tumor resection was performed with the attempt to leave a 2mm×2mm×2mm disease margin. Bioluminescence and fluorescence images (ex: 745nm; em: 800nm; lamp level, low; exposure time, 10s; binning 4; and f =1) were obtained pre-incision, post-incision, and post-resection using the Perkin Elmer IVIS Spectrum In Vivo System (Caliper Lifesciences, Hopkinton, MA). Signal-to-background ratio (SBR) was calculated with ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) as previously described [38]. Mice that received ICS (n=12) were randomized to PDT arm (n=6) or control arm (n=6). The PDT group were irradiated at the residual site with 665nm light (B&W Tek, Inc. diode laser) to a dose of 135J/cm2 at a power density of 75mW/cm2 for 30 minutes, while the rest of the animals remained under anesthesia. All wounds were closed with 4-0 silk braided suture. Disease progression were calculated based on tumor size measured with a digital caliper every 2-3 days post-surgery. Tumor volume was calculated with the formula: 1/2 × (length × width2). The trial workflow is illustrated in Fig. S5.

Intracranial Tumor Model

Orthotopic models of GBM were created as described previously [39]. 6-week old C57BL/6 mice (n=4) were anesthetized using 1-4% isoflurane, restrained in a stereotactic device (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL), and incised along the scalp midline. Sterilization was provided with Betadine Solution Swabsticks (povidone-iodine solution USP, 10%). A burr hole was placed 3mm lateral and 3mm posterior to the bregma in the right cerebral hemisphere. A stereotactically-guided 10μl syringe (Hamilton Co., Reno, NV) was used to deliver 3x105 GL261 cells in 3uL DMEM at a rate of 0.5 μL/min 3.5mm deep into the cortex. Mice underwent in vivo bioluminescence imaging one week after implantation to confirm intracranial tumor growth.

Upon observation of signs of illness in mice with intracranial GBM implants, 5mg/kg ICS was administered intravenously via tail-vein. Mice were sacrificed with brains harvested and imaged under IVIS Spectrum system, 24hrs post-injection. Coronal sections of the specimen were placed on a microscope slide and imaged on the Odyssey CLx-1 (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) flatbed laser scanner to capture the distribution of ICG at 21um pixel resolution using the 700-emission channel (675nm excitation laser) and 800-emission channel (785nm excitation laser).

Histopathology

The brain sections were fixed in 10% formalin in 4°C for 12-18 hours. Samples were incubated in 30% sucrose in PBS for 1-2 days and embedded in a mold with OCT on dry ice. Specimens were conserved in −80°C freezer. 14μm sections were made with cryostat and the slides underwent hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. S6).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 Statistics (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Multiple t tests were performed to compare cell viabilities at each concentration in the in vitro PDT study. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare SBRs of tumor fluorescence pre- and post-administration of ICS. Ordinary one-way ANOVA was completed to compare the final tumor volume means of the three groups. Thereby, multiple t tests were performed to compare tumor volumes at corresponding timepoints between the ICS+PDT and ICS-only groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Preparation and characterization of ICS

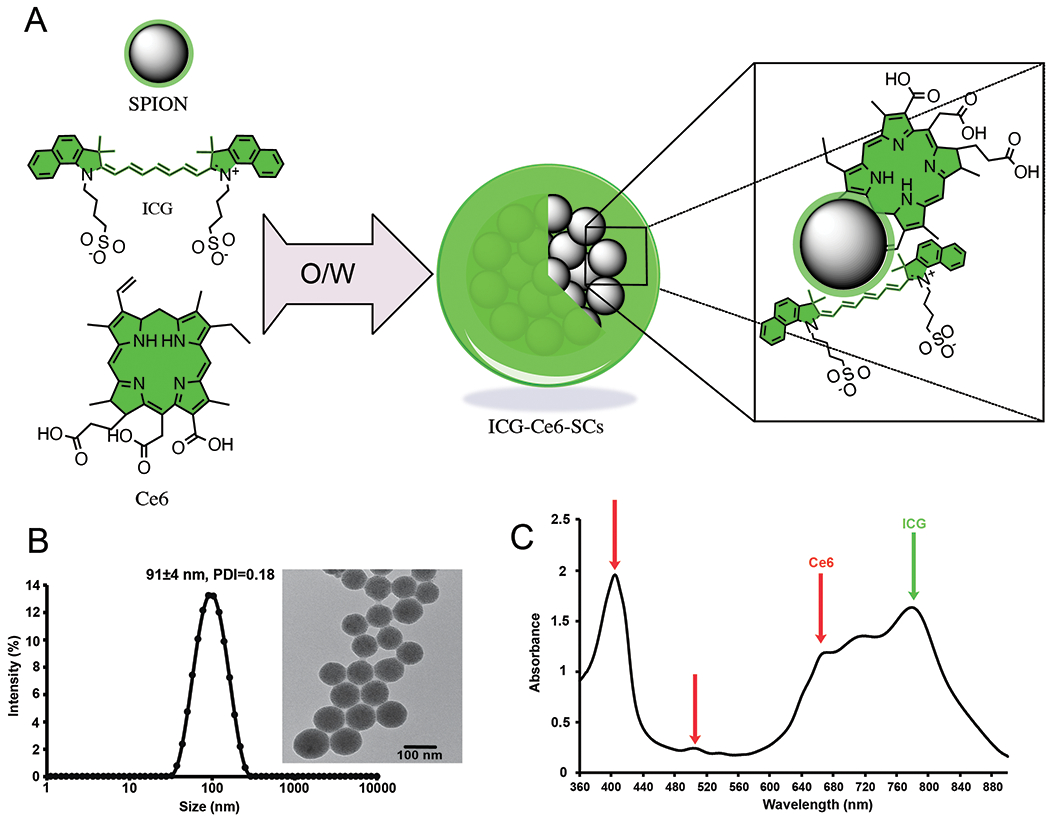

ICG and Ce6-coated SPION nanoclusters (ICS) (Fig. 1a) were highly soluble in aqueous solution, with the amphiphilic Ce6 and ICG molecules directed to the surface of SPIONs (Fig. S1) via hydrophobic interactions and serving as stable coating agents. The ICS clusters had an average hydrodynamic diameter of 91 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) <0.2 and narrow size distribution in water (Fig. 1b, inset). The encapsulation efficiency is >79% for ICG and > 88% for Ce6, when the ICG:Ce6:Fe ratio (w/w) is in the range of 1:1:2 to 1:1:4 and the payload of ICG and Ce6 for different synthetic ratio conditions were 14-21% and 15-23%, respectively (Table S1). Analysis of the absorbance spectrum of ICS reveals distinct peaks at 404 and 665nm (Ce6), suggestive of excellent solubility, and 780nm (ICG) (Fig. 1c). The ICS produced fluorescence under excitation wavelengths of 404nm and 780nm for Ce6 and ICG, respectively (Fig. S2a). The stability of the nanocluster was monitored by DLS and no significant change in size over 7 days was observed in water (Fig. S3). As expected, ICG-SC exhibits strong NIR signal when excited at 745nm and captured emitted light in the 800nm range. The signal peaked at the 25μg/ml concentration with a radiance of 2.45×108 photons and declined thereafter. ICS cluster demonstrated a lower peak intensity (9.25×107 photons radiance), approximately 40% of that of ICG-SC, occurring at the same concentration (25μg/ml) (Fig. S2b). In contrast, Ce6-SC does not exhibit optical imaging capabilities in the NIR wavelength range.

Fig. 1.

(a) Illustration of ICG/Ce6-coated SPION nanoclusters (ICS). The amphiphilic ICG and Ce6 molecules solubilized the hydrophobic SPIONs in aqueous media by the self-assembly on the surface using an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion. (b) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) of ICS in water. Inset: TEM image of ICS shows tightly packed nanoclusters (scale bar: 100 nm). (c) UV-vis spectra of ICS in water.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Phototoxicity

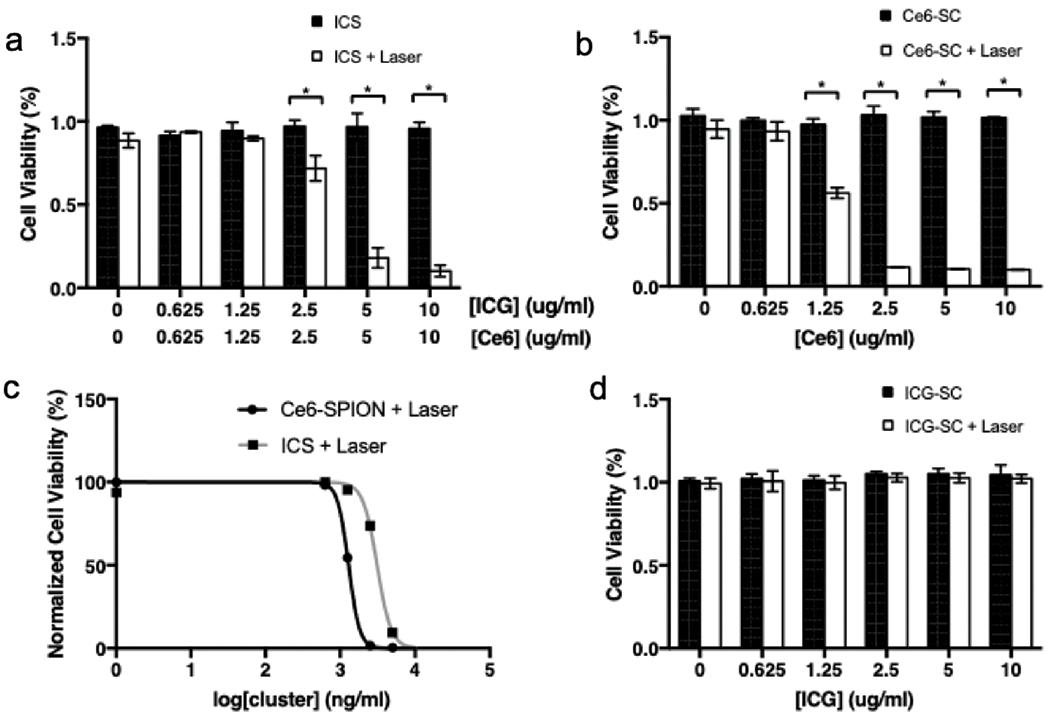

No evidence of ICS cytotoxicity on GL261 cells was observed in vitro in the absence of light irradiation (Fig. 2a). Cells incubated with the highest concentration (10μg/ml) demonstrated 95.7%±3.7% viability. Similar lack of cytotoxicity was also observed in cells incubated with ICG-SCs and Ce6-SCs (Fig. 2b, d).

Fig. 2.

Viability of GL261 cells after incubation in increasing concentrations of (a) ICS, (b) Ce6-SC and (d) ICG-SC without laser irradiation (black bar) and with laser irradiation (white bar). All wells were incubated in respective nanoparticles for 24hrs before laser irradiation (or absence of) and tested with MTS colorimetric assay 24hrs post-treatment. (c) EC50 curves for PDT treatment with Ce6-SC and ICS.

Optical absorption spectra of ABDA dropped over time in response to irradiation (665 nm, 5 mW/cm2) of ABDA-containing samples in the presence of ICS, signaling adequate ROS production (Fig. S4). In vitro, cell viabilities were plotted against particle concentrations upon irradiation of GL261 cells. In ICS (10μg/ml) +laser treated cells, only 10.1%±3.5% was viable, significantly lower than the no-laser matched control (95.7%±3.7% viability, p<0.001). Significant phototoxicity was also observed when the concentration of ICS was reduced to 5μg/ml (17.9%±6.0%, p<0.001) and 2.5μg/ml (71.7%±7.6%, p<0.001) (Fig. 2a). Ce6-SC demonstrated slightly more efficient phototoxicity than the combined ICS at the 2.5μg/ml concentration (11.6%±0.3% vs. 71.7%±7.6% p<0.001) (Fig. 2b). Comparison of the dose-response curves of Ce6-SPION (R2 = 0.99) and ICS (R2 = 0.98) illustrated a rightward shift of the combined nanocluster; the EC50 of Ce6-SC and ICS are 1.29μg/ml and 3.10μg/ml respectively (Fig. 2c). ICG-SC exhibits no evidence of phototoxicity upon irradiation (Fig. 2d).

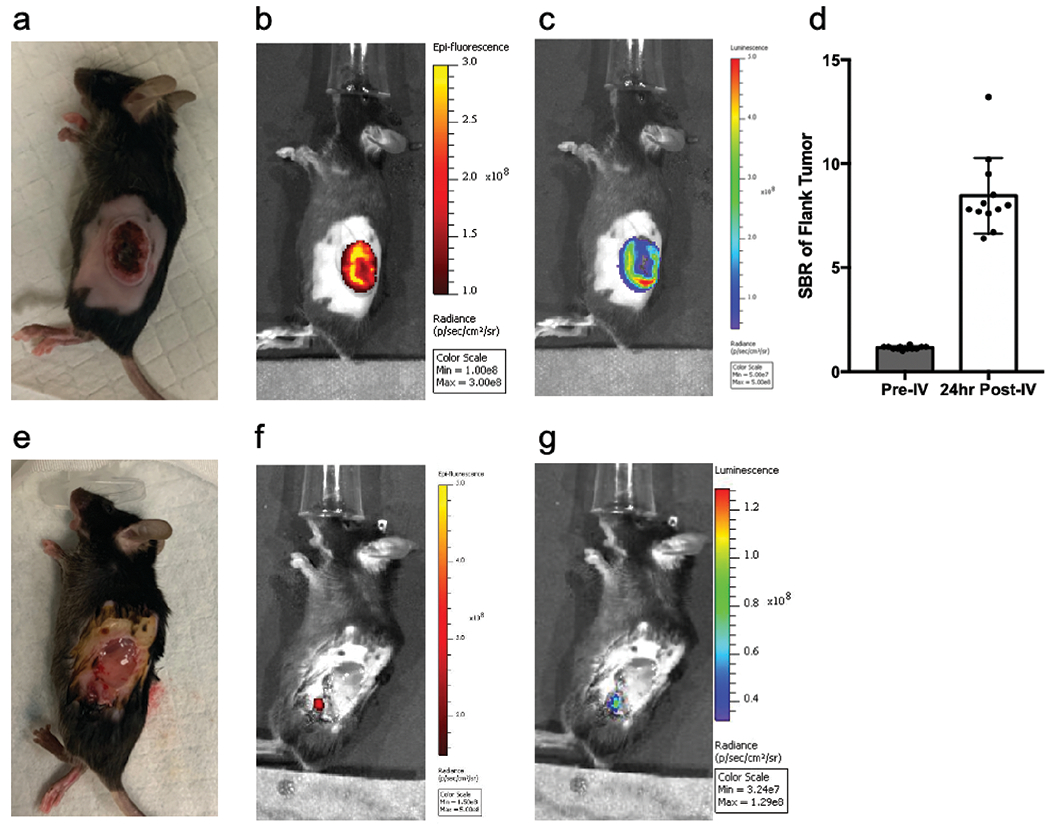

NIR Fluorescence of Gross and Margin Neoplasm

The mean volume of the flank tumors was approximately 800mm3 preoperatively. NIR fluorescence and bioluminescence images demonstrated strong and accurately localized NIR signal in all tumors, indicating successful uptake of ICS (Fig. 3a–c). The signal-to-background ratio (SBR) post-injection was 8.5 ± 0.6 compared to pre-injection (1.2 ± 0.03, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3d). After partial-resection, bioluminescence imaging of the surgical bed demonstrated presence of residual neoplasm in all cases. Colocalized NIR signal was detected in 10/12 cases (Fig. 3e–g)

Fig. 3.

Preoperatively, 5mg/kg of ICS based on Ce6 weight were administered with tail-vein injection. (a) White light image and (b) fluorescence images (ex: 745nm; em: 800nm; lamp level, low; exposure time, 10s; binning 4; and f =1) were obtained and (c) bioluminescence images were captured 10mins following intraperitoneal injection of D-Luciferin sodium salt (150mg/kg). (d) Mean signal-to-background ratio of fluorescence signal before (left) and after (right) intravenous injection of ICS (n=12). Following partial resection of gross tumor, (e) white light, (f) fluorescence, and (g) bioluminescence images were acquired to localize residual disease. All fluorescence and bioluminescence images were captured with Perkin Elmer IVIS Spectrum In Vivo System.

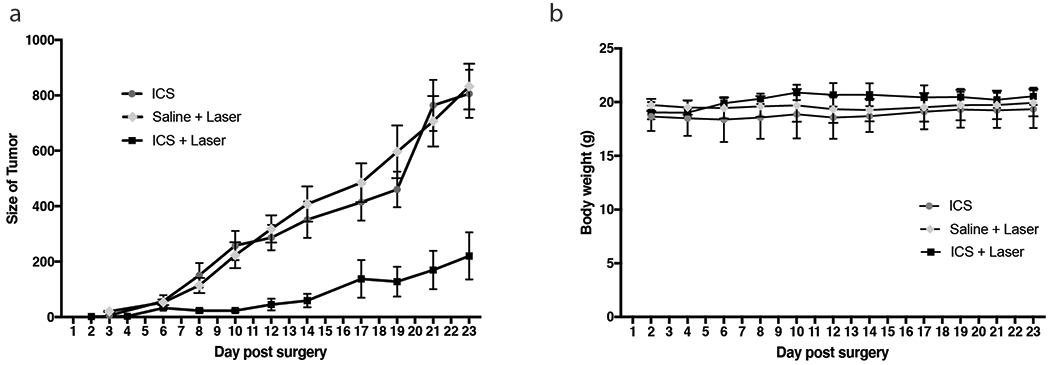

Recurrent Tumor Growth

The size of the residual neoplasm was plotted over time (Fig. 4a). A significantly slower rate of recurrent growth was observed in the group that received ICS+laser compared to the two control groups: ICS-only and saline+laser (p=0.0073). The difference of tumor size reached statistical significance on postoperative day 8 (23.07mm3 in ICS+laser vs. 150.5mm3 in ICS group, p=0.045). On postoperative day 14, the difference in tumor size steadily widened to 59.4mm3 in ICS+laser vs. 351.4mm3 in ICS group (p=0.0094). The mean size of the tumors in the saline control group (831.9mm3) exceeded our defined endpoint 800mm3 on day 23, at which point the animals were sacrificed. The endpoint mean volume of the ICS+laser tumors was significantly smaller at 220.4mm3 (vs. 806.1 mm3 in ICS group, p=0.0055). In the control groups, all subjects (10/10) demonstrated continued tumor regrowth over time; whereas in the ICS+laser group, stable residual tumor volume was observed in 3/6 mice and recurrent growth was observed in the rest. There was no significant difference between the mean animal weight throughout (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

(a) Tumor sizes were measured with a caliper every 2-3 days starting from 2 days post-surgery in the saline+laser group (n=4), ICS group (n=6) and ICS+laser group (n=6). Mean tumor volume was plotted over the post-treatment days. Error bar represents standard error. (b) Body weights were monitored in the meantime.

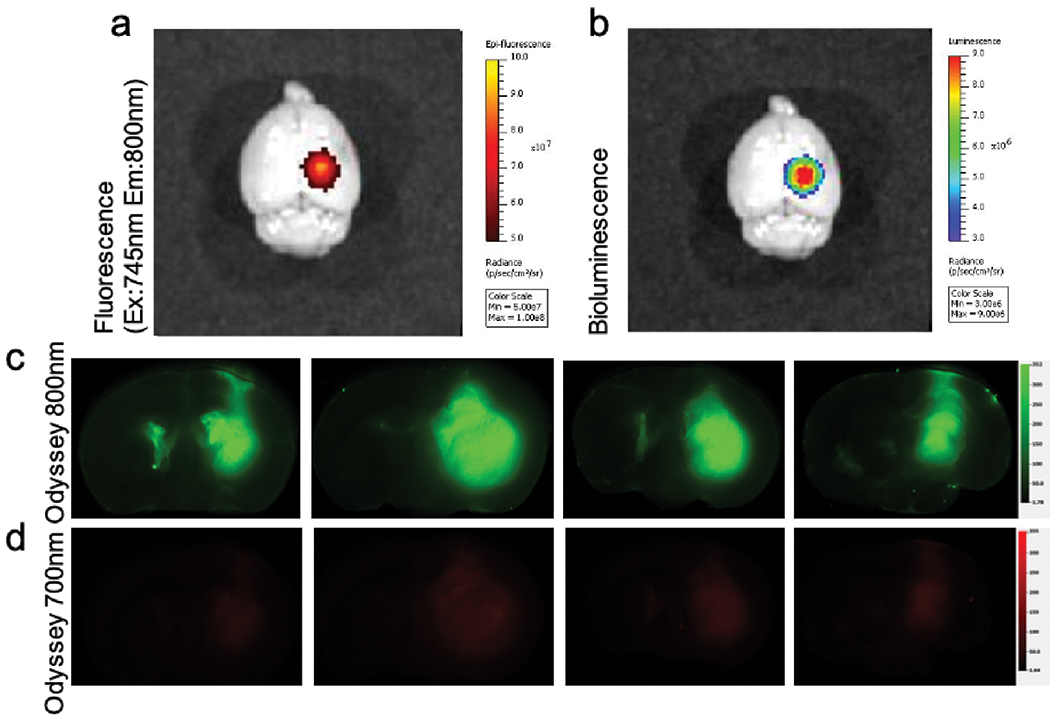

NIR Fluorescence in Intracranial Tumor

In this small pilot study, the brains of four mice with intracranial GBM graft were harvested 24hrs after ICS injection and scanned with two imaging systems. The intact brain was imaged on IVIS Spectrum (Fig. 5a, b) and coronal sections were imaged on the Odyssey CLx Imaging System for higher resolution analysis. Ce6 is the main contributor of signal on 700-emission channel, whereas the signal on the 800-emission channel is attributed to ICG (Fig. 5c, d) according to the particle absorbance spectrum. On both imaging platforms, fluorescence signal was visualized on all tumor-bearing specimens, suggesting the capability of ICS to reliably access tumor cells in the brain parenchyma. It was noted that the average SBR (calculated with the intrinsic analytic algorithm on Odyssey) of fluorescence signal on the 800-emission channel was grossly 4× stronger than that on the 700-emission channel (24.7 ± 3.6 vs. 7.4 ± 0.6, p=0.016). The signal co-localization between the two channels provided evidence for the stability of ICS formulation in vivo and the potential to use ICS for combined imaging-guided resection and PDT treatment on intracranial neoplasms.

Fig. 5.

(a) Ex vivo fluorescence image (ex: 745nm, em: 800nm) of the total brain on IVIS Spectrum in vivo System 24hrs post-IV injection of ICS 5mg/kg. (b) Bioluminescence image demonstrated the location of tumor. Corresponding (c) pseudo-colored (green) fluorescence signal imaged under the Odyssey 800-emission channel and (d) pseudo-colored (red) fluorescence signal under the 700-emission channel of the four mice. Color scale for Odyssey 700-emission and 800-emission channels were aligned.

Discussion

These results demonstrated that an integrative treatment strategy for malignant gliomas, comprising fluorescence-guided resection with adjuvant PDT, is technically feasible using a multimodal theragnostic nanocluster. A major advantage of the ICS nanocluster is its composition of solely low-cost and FDA-approved materials with well-characterized safety profiles and no requirement of additional stabilizing modifications, promising a comparatively streamlined path to clinical integration.

ICS nanoclusters are prepared via oil-in-water emulsions, which is simple, efficient, and highly reproducible. The core (SPIONs) and shell (ICG and Ce6) structure is in contrast to the traditional encapsulation formulation, where significant vicinity-related mutual suppression of both fluorescence and ROS generation had been observed [40]. The quenching phenomenon is a consequence of the reduction in enhancement of intersystem crossing and subsequent formation of the triplet state [34]. Fluorescence quenching could also be a result of exciton coupling between two nearby Ce6 and ICG molecules [40]. In this regard, the proximity of the chromophores to the iron ions on the SPION surfaces may have enhanced spin-orbit coupling due to the external heavy atom effect [41], thereby increasing triplet formation. While the ICS formulation is not free of the quenching phenomenon, as suggested by the moderately diminished fluorescence signal and PDT efficacy described above, both capabilities were preserved to a significant degree. It has been suggested that the nanocluster may dissociated after internalization by cancer cells, causing the release of Ce6 and ICG, resulting in an increase in fluorescence and singlet oxygen generation [42].

ICS uptake into the neoplasm was successfully demonstrated in all flank tumor-bearing animals. Notably, high-sensitivity NIR imaging also allowed detection of small residual disease, confirming its potential utility in visualizing and resecting infiltrative residuals. Nanoparticles are better trapped in the extracellular matrix or internalized by cells than free dyes, therefore they exhibit less non-specific diffusion through the interstitial space during surgery [43]. While the current orthotopic murine model does not permit brain surgery, it validated that the nanocluster crosses the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) and accumulates in intracranial neoplasms. Some argues that Ce6 itself can be purposed as a fluorescence agent, however, the increasingly recognized advantages and future potential of NIR fluorophores over their visible-light counterparts cannot be neglected [14]. Here, ICG in the ICS formulation enabled superior contrast-enhancement for neoplasm detection, with a 4-fold higher signal-to-background ratio compared to Ce6.

To test the hypothesis that peri-operative local treatment with PDT can reduce tumor recurrence and prolong survival, a partial resection trial designed by Madajewski et al. [44] was adopted. The results suggest that ICS-mediated phototoxicity lead to significantly reduced rate of tumor regrowth in mice that received ICS+laser. Ideally, treatment-induced toxicity would precipitate complete arrest in residual tumor growth, which was indeed observed in 3 out of 6 subjects in this trial. Future studies to optimize PDT parameters may play a role in improving treatment response. Nevertheless, given that the current photosensitizers can provoke photochemically-induced tissue destruction only to a certain depth, we propose that local application of PDT on residual tumor preceded by fluorescence-assisted debulking surgery may optimize the chance for local gross-total removal of neoplasm.

There are several limitations to the current study. One of constraints of ICS is that it is not cell specific. While EPR allows nanoparticles to reach intracranial neoplasms, active cellular targeting is rapidly developing as a superior strategy as it utilizes an affinity ligand to bind tumor cells through antigens or receptors without affecting other normal tissue [45, 46]. For instance, angiopep-conjugated PEG-PCL nanoparticles has been shown to bypass the BBB and actively target gliomas in an intracranial U87MG glioma model [47]; quantum dots are optical nanoparticles that have been shown to be phagocytosed by macrophages and colocalize with experimental gliomas [48]. However, despite many successful pre-clinical studies, none of the actively targeted nanocarriers have advanced past clinical trials compared to 15 passively targeted nanocarriers that have been approved for clinical use [49]. As the present nanoparticle formulation offers an opportunity to attach different moieties [50], one of the future directions is to aim for targeted delivery, despite current challenges. Furthermore, due to the constrain of the IVIS imaging platform, we had used 745nm as the excitation source of ICG instead of its peak excitation wavelength (780nm). Lastly, the surgical model of GBM in the current survival study was a flank tumor model that does not fully recapitulate the tumor’s behavior in the brain, as surgery to remove intracranial neoplasm in such a small animal can be a morbid procedure. Future work is required to establish an intracranial GBM model on a larger animal where brain surgery is feasible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01EB029238 to A.T., R21 EB023989 to A.T., R01NS100892 to Z.C., R01CA175480 to Z.C., P01CA087971 to T.M.B., P30CA016520 to Z.C., T.M.B., and A.T., R01CA236362 to T.M.B.); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR000003 to JYKL, TL1TR001880 to SS Cho); The U. of Penn. University Research Foundation Award to A.T.; Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania to JYKL;

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: All animal procedures were conducted according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania (#805979, #806516) and NIH and ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent to participate/publication: not applicable

Availability of data and material: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Code availability: not applicable

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data is available from the online library or from the author.

References

- 1.Tamimi AF, Juweid M (2017) Epidemiology and Outcome of Glioblastoma. In: Glioblastoma. p 143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DR, O’Neill BP (2012) Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J Neurooncol 107:359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallner KE, Galicich JH, Krol G, et al. (1989) Patterns of failure following treatment for glioblastoma multiforme and anaplastic astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 16:1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanai N, Polley M-Y, McDermott MW, et al. (2011) An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg 115:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, et al. (2001) A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg 95:190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown TJ, Brennan MC, Li M, et al. (2016) Association of the Extent of Resection With Survival in Glioblastoma. JAMA Oncol 2:1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orringer D, Lau D, Khatri S, et al. (2012) Extent of resection in patients with glioblastoma: Limiting factors, Perception of resectability, and effect on survival. J Neurosurg 117:851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, et al. (2006) Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma : a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 7:392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong G, Antaris AL, Dai H (2017) Near-infrared fluorophores for biomedical imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schols RM, Connell NJ, Stassen LPS (2015) Near-infrared fluorescence imaging for real-time intraoperative anatomical guidance in minimally invasive surgery: A systematic review of the literature. World J Surg 39:1069–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JYK, Thawani JP, Pierce J, et al. (2016) Intraoperative Near-Infrared Optical Imaging Can Localize Gadolinium-Enhancing Gliomas During Surgery. Neurosurgery 79:856–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JYK, Pierce JT, Zeh R, et al. (2017) Intraoperative Near-Infrared Optical Contrast Can Localize Brain Metastases. World Neurosurg 106:120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JYK, Pierce JT, Thawani JP, et al. (2017) Near-infrared fluorescent image-guided surgery for intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery 128:380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr JA, Franke D, Caram JR, et al. (2018) Shortwave infrared fluorescence imaging with the clinically approved near-infrared dye indocyanine green. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruyama T, Muragaki Y, Nitta M, et al. (2016) Photodynamic therapy for malignant brain tumors. Japanese J Neurosurg 25:895. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eljamel S (2010) Photodynamic applications in brain tumors: A comprehensive review of the literature. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 7:76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eljamel MS, Goodman C, Moseley H (2008) ALA and Photofrin® Fluorescence-guided resection and repetitive PDT in glioblastoma multiforme: A single centre Phase III randomised controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci 23:361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Yu Y, Kang L, Lu Y (2014) Effects of chlorin e6-mediated photodynamic therapy on human colon cancer SW480 cells. Int J Clin Exp Med 7:4867. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nann T (2011) Nanoparticles in photodynamic therapy. Nano Biomed Eng [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul S, Heng PWS, Chan LW (2013) Optimization in solvent selection for chlorin e6 in photodynamic therapy. J Fluoresc 23:283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelkar SS, Reineke TM (2011) Theranostics: Combining imaging and therapy. Bioconjug Chem 22:1879–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JH, Lee K, Moon SH, et al. (2009) All-in-One target-cell-specific magnetic nanoparticles for simultaneous molecular imaging and siRNA delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 48:4174–4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thawani JP, Amirshaghaghi A, Yan L, et al. (2017) Photoacoustic-Guided Surgery with Indocyanine Green-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Clusters. Small 13:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kircher MF, De La Zerda A, Jokerst JV., et al. (2012) A brain tumor molecular imaging strategy using a new triple-modality MRI-photoacoustic-Raman nanoparticle. Nat Med 18:829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Zhao J, Tan T, et al. (2020) Nanoparticle drug delivery system for glioma and its efficacy improvement strategies: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Nanomedicine 15:2563–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo J, Gao X, Su L, et al. (2011) Aptamer-functionalized PEG-PLGA nanoparticles for enhanced anti-glioma drug delivery. Biomaterials 32:8010–8020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan A, Scholz R, Maier-Hauff K, et al. (2006) The effect of thermotherapy using magnetic nanoparticles on rat malignant glioma. J Neurooncol 78:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michael JS, Lee B-S, Zhang M, Yu JS (2018) Nanotechnology for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Transl Intern Med 6:128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pardridge WM (2005) The blood-brain barrier and neurotherapeutics. NeuroRx 2:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Zhen Z, Todd T, et al. (2013) Nanoparticles for improving cancer diagnosis. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Reports 74:35–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chenthamara D, Subramaniam S, Ramakrishnan SG, et al. (2019) Therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles and routes of administration. Biomater Res 23:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huynh E, Zheng G (2013) Engineering multifunctional nanoparticles: All-in-one versus one-for-all. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 5:250–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higbee-Dempsey E, Amirshaghaghi A, Case MJ, et al. (2019) Indocyanine Green–Coated Gold Nanoclusters for Photoacoustic Imaging and Photothermal Therapy. Adv Ther 2: 1900088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amirshaghaghi A, Yan L, Miller J, et al. (2019) Chlorin e6-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle (SPION) Nanoclusters as a Theranostic Agent for Dual-Mode Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Sci Rep 9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan L, Amirshaghaghi A, Huang D, et al. (2018) Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX)-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle (SPION) Nanoclusters for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Adv Funct Mater 28:1707030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munnier E, Cohen-Jonathan S, Linassier C, et al. (2008) Novel method of doxorubicin–SPION reversible association for magnetic drug targeting. Int J Pharm 363:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Husain SR, Behari N, Kreitman RJ, et al. (1998) Complete regression of established human glioblastoma tumor xenograft by interleukin-4 toxin therapy. Cancer Res 58:3649–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeh R, Sheikh S, Xia L, et al. (2017) The second window ICG technique demonstrates a broad plateau period for near infrared fluorescence tumor contrast in glioblastoma. PLoS One 12:e0182034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumann BC, Dorsey JF, Benci JL, et al. (2012) Stereotactic intracranial implantation and in vivo bioluminescent imaging of tumor xenografts in a mouse model system of glioblastoma multiforme. J Vis Exp 4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan A, Tang X, Qiu X, et al. (2015) Activatable photodynamic destruction of cancer cells by NIR dye/photosensitizer loaded liposomes. Chem Commun 51:3340–3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herve P, Nome F, Fendler JH (1984) Magnetic Effects on Chemical Reactions in the Absence of Magnets. Effects of Surfactant Vesicle Entrapped Magnetite Particles on Benzophenone Photochemistry. J Am Chem Soc 106:8291. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saravanakumar G, Kim J, Kim WJ (2016) Reactive-Oxygen-Species-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems: Promises and Challenges. Adv Sci 4:1600124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enochs WS, Harsh G, Hochberg F, Weissleder R (1999) Improved delineation of human brain tumors on MR images using a long- circulating, superparamagnetic iron oxide agent. J Magn Reson Imaging 9:228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madajewski B, Judy BF, Mouchli A, et al. (2012) Intraoperative Near-Infrared Imaging of Surgical Wounds after Tumor Resections Can Detect Residual Disease. Clin Cancer Res 18:5741–5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raucher D, Dragojevic S, Ryu J (2018) Macromolecular drug carriers for targeted glioblastoma therapy: Preclinical studies, challenges, and future perspectives. Front. Oncol 8:624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Béduneau A, Saulnier P, Benoit J-P (2007) Active targeting of brain tumors using nanocarriers. Biomaterials 28:4947–4967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xin H, Jiang X, Gu J, et al. (2011) Angiopep-conjugated poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles as dual-targeting drug delivery system for brain glioma. Biomaterials 32:4293–4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ackson H, Muhammad O, Daneshvar H, et al. (2007) Quantum Dots Are Phagocytized By Macrophages And Colocalize With Experimental Gliomas. Neurosurgery 60:524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, et al. (2018) Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Commun 9:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amirshaghaghi A, Altun B, Nwe K, et al. (2018) Site-Specific Labeling of Cyanine and Porphyrin Dye-Stabilized Nanoemulsions with Affibodies for Cellular Targeting. J Am Chem Soc 140:13550–13553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.